Introduction

Most individuals experience trauma at some time in their lives, where 70% of respondents in the World Mental Health Survey reported exposure to at least one traumatic event [Reference Benjet, Bromet, Karam, Kessler, McLaughlin and Ruscio1]. The lifetime prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is estimated to be 10% in the United States [Reference Kilpatrick, Resnick, Milanak, Miller, Keyes and Friedman2], where symptoms are characterized as re-experiencing, hyperarousal, avoidance of trauma-related situations, negative cognition, and emotional numbing, which can last for years after the event [Reference Association3].

Brain structural abnormalities have been consistently associated with PTSD, with recent structural neuroimaging meta-analyses reporting smaller gray matter (GM) volumes within the frontal lobe, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and insula in patients with PTSD when compared to controls [Reference Bromis, Calem, Reinders, Williams and Kempton4–Reference Xiao, Yang, Su, Gong, Huang and Wang9]. The PTSD working group from the Enhancing Neuroimaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA)-Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) (https://enigma.ini.usc.edu) has previously analyzed structural brain differences between patients with PTSD and controls by pooling data provided by research groups around the world, using segmented brain volumes derived by FreeSurfer (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). In a region-of-interest (ROI) approach, Logue et al. [Reference Logue, van Rooij, Dennis, Davis, Hayes and Stevens10] analyzed eight a priori subcortical structures comparing 794 patients with PTSD and 1074 controls and found that patients with PTSD had significantly smaller hippocampal volumes compared to trauma-exposed (TE) controls. Wang et al. [Reference Wang, Xie, Chen, Cotton, Salminen and Logue11] conducted a mega-analysis across 68 cortical regions comparing 1379 patients with PTSD and 2192 controls and revealed that patients with PTSD exhibited significantly smaller GM volumes across the orbitofrontal region, superior temporal gyrus, insula, lingual, and superior parietal gyri, and that these regions were also negatively correlated with PTSD symptom severity. However, Wang et al. used a control group comprising both TE- and non-trauma-exposed (nTE) controls, which was noted as a limitation in their study. Both Logue et al. [Reference Logue, van Rooij, Dennis, Davis, Hayes and Stevens10] and Wang et al. [Reference Wang, Xie, Chen, Cotton, Salminen and Logue11] did adjust for sex, age, total intracranial volume (ICV), and scanner site. More recently, ENIGMA-PTSD has published two studies: the first examined only the cerebellum and found significantly smaller GM and white matter (WM) cerebellar volumes and cerebellar subregions in patients with PTSD compared with controls [Reference Huggins, Baird, Briggs, Laskowitz, Hussain and Fouda12], and the second reported diminished cortical thickness associated with PTSD within the prefrontal cortex, insula, occipital cortex, and cingulate cortex [Reference Yang, Huggins, Sun, Baird, Haswell and Frijling13].

To complement the existing research, the current study used a whole-brain voxel-based morphometry (VBM) approach to meta-analysis. VBM methodologies are unconstrained by anatomical boundaries and can observe differential effects at a voxel level, while effects in ROI analyses are only observed at the level of the predefined region. VBM analyses also encompass the whole brain and include WM structures at the voxel level. VBM meta-analyses typically involve pooling published peak coordinates, which represent the voxel location where the statistical effect is strongest. This results in a loss of valuable information as nonsignificant data are excluded. An alternative approach, used in the current study, is to use whole-brain statistical maps that are produced at the end of the VBM processing pipeline. Statistical maps contain the statistical results for a given analysis (e.g., t-values from group comparisons) at the voxel level across the whole brain, meaning data from all voxels are included in the analysis rather than just peak values. This methodology has previously been used to study PTSD by Bromis et al. [Reference Bromis, Calem, Reinders, Williams and Kempton4], where the authors combined statistical maps and peak coordinates. This has demonstrated more accurate results in comparison to using peak coordinates [Reference Salimi-Khorshidi, Smith, Keltner, Wager and Nichols14]. However, there are practical challenges in that statistical maps are not always made available by authors, and if they are, different VBM processing parameters can affect results [Reference Zhou, Wu, Zeng, Qi, Ferraro and Xu15].

To address these issues, we have developed the ENIGMA-VBM tool [Reference Si, Bi, Yu, See, Kelly and Ambrogi16]. The tool is designed for contributing sites to process their data locally using a standardized VBM pipeline with automated quality control checks. Sites share the resulting statistical maps, containing group-level data, with the researchers conducting the meta-analysis, thus addressing participant-level data privacy concerns. In the current study, we have used the ENIGMA-VBM tool to conduct the largest VBM meta-analysis in PTSD to date using only whole-brain statistical maps.

Our main analysis compared total and regional GM and WM volumes between patients with PTSD and controls, where we expected that patients would exhibit smaller regional volumes within the frontal lobe, hippocampus, ACC, insula, cerebellum, and total GM volumes compared with controls, consistent with previous literature [Reference Bromis, Calem, Reinders, Williams and Kempton4–Reference Huggins, Baird, Briggs, Laskowitz, Hussain and Fouda12]. In exploratory analyses, we conducted subgroup investigations to compare patients with PTSD with TE controls to try to disentangle the effects of trauma exposure from PTSD-related structural brain abnormalities. We also compared controls with and without trauma exposure to test the effects of trauma per se [Reference Bromis, Calem, Reinders, Williams and Kempton4]. As the ENIGMA-PTSD sample consisted of participants from military and civilian backgrounds, we analyzed military- and civilian-recruited cohorts separately. This exploratory analysis aimed to examine whether underlying sample characteristics may be associated with different brain regions, as military populations experience more combat-related trauma [Reference Jakob, Lamp, Rauch, Smith and Buchholz17, Reference Guina, Nahhas, Sutton and Farnsworth18] and exhibit poorer treatment outcomes [Reference Straud, Siev, Messer and Zalta19]. Previous evidence suggests that combat trauma is related to more severe PTSD symptoms [Reference Jakob, Lamp, Rauch, Smith and Buchholz17] and has a higher risk of lifetime PTSD with poorer psychosocial outcomes [Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski and Rosenheck20]. This may be due to the extended duration of military traumatic experiences as compared with more acute civilian trauma, such as motor vehicle accidents [Reference Helzer, Robins and McEvoy21]. We also examined associations between regional brain volumes in patients with PTSD and clinical variables such as PTSD severity, depression severity, and childhood trauma. In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for sex due to higher incidence rates of PTSD in females [Reference McGinty, Fox, Ben-Ezra, Cloitre, Karatzias and Shevlin22, Reference Blanco, Hoertel, Wall, Franco, Peyre and Neria23] and sex differences in traumatic experiences [Reference Kessler, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Benjet, Bromet and Cardoso24]. Finally, we performed several sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our findings by varying VBM processing parameters.

Methods

Cohorts and participants

Structural neuroimaging scans and clinical data were provided by the ENIGMA-PGC PTSD working group for 36 cohorts from 28 sites, comprising 1309 patients with PTSD and 2198 controls. Controls were both TE and nTE (Table 1). One site comprised only TE and nTE controls. Most cohorts were adult samples, except for two non-adult cohorts consisting of participants under the age of 20. Cohorts consisted of military- and civilian-recruited samples, and one sample of police officers (Table 2). Patients were diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV or DSM-5 criteria using the instruments listed in Table 2. Sites had obtained approval from their local ethics committee and written informed consent from study participants. Further study details and inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 in Supplement A.

Table 1. Clinical and demographic characteristics for each cohort

Abbreviations: nTE, non-trauma-exposed; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; TE, trauma-exposed.

Note: For sites with multiple scanners, participants were grouped by a scanner model where possible to form processing cohorts.

a Where the control subgroups do not add-up to the total number of controls, which is due to unspecified trauma exposure of the control participant.

b UCT did not have enough current patients with PTSD (<8) for the main analysis and was only included in the subgroup comparison between TE and nTE controls.

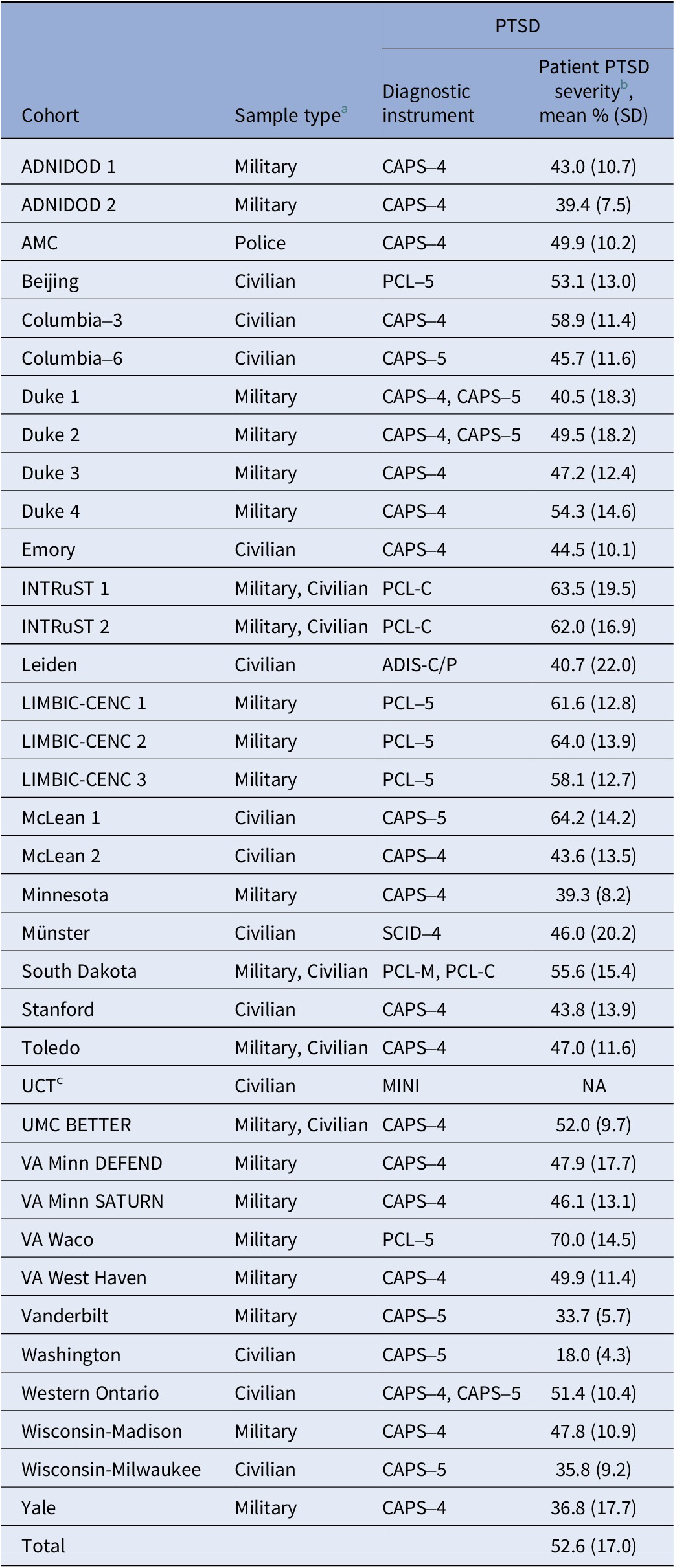

Table 2. Sample type and patient with PTSD symptom severity for each cohort

Abbreviations: nTE, non-trauma-exposed; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; TE, trauma-exposed.

Note: PTSD diagnosis and severity scales: CAPS-4/5 = Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV/DSM-5 [Reference Blake, Weathers, Nagy, Kaloupek, Gusman and Charney61, Reference Weathers, Bovin, Lee, Sloan, Schnurr, Kaloupek, Kean and Marx62]; PCL-5/C/M = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Civilian or Military version) [Reference Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte and Domino63]; ADIS-C = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children [Reference Silverman and Nelles64]; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM [Reference First, Williams, Karg and Spitzer65]; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview [Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller66]; MPSS = Modified PTSD Symptom Scale [Reference Falsetti, Resnick, Resick and Kilpatrick67]; TSCC = Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children [Reference Briere68]; PDS = Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale [Reference Foa, McLean, Zang, Zhong, Powers and Kauffman69].

a PTSD patients and controls were recruited from the same sample types.

b PTSD severity has been quantified as a percentage of the total score for visual comparison across cohorts. Raw scores are available in Supplement A (Supplementary Table S4).

Cohort-level image processing and analysis

The ENIGMA-VBM tool (https://sites.google.com/view/enigmavbm) was developed for the ENIGMA consortium by the authors for VBM case-control studies [Reference Si, Bi, Yu, See, Kelly and Ambrogi16]. The tool processes T1-weighted brain images for each cohort using the DARTEL (Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration Through Exponentiated Lie Algebra) [Reference Ashburner25] VBM processing pipeline in SPM12 (Statistical Parametric Mapping; https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) within MATLAB, using a smoothing kernel of 8 mm and Jacobian modulated data, controlling for age and total ICV. A detailed description of the tool is available in Supplement B.

Sites provided T1-weighted brain imaging and clinical data for participants. Scanner information and acquisition methods can be found in Supplementary Table S3. Each cohort was processed using the ENIGMA-VBM tool v1.076, which conducted GM and WM voxel-wise statistical analysis comparing patients with controls. For sites with multicenter data or multiple studies, we used cohorts for VBM processing where participants were grouped based on scanner model, where possible, to minimize the effects of scanner model [Reference Liu, Hou, Zhang, Lin, Fan and You26, Reference Huppertz, Kroll-Seger, Kloppel, Ganz and Kassubek27], while ensuring there were sufficient patients with PTSD and controls for analysis. As an example, the cohorts ADNIDOD 1 and ADNIDOD 2 are from the same study but have been processed as two cohorts to account for different scanner models.

Group comparisons of regional brain volumes

The main analysis compared voxel-wise GM and WM volumes between patients with PTSD and all controls (inclusive of TE and nTE controls). Exploratory subgroup analyses compared: (1) patients with PTSD to TE controls; (2) TE to nTE controls; (3) patients with PTSD to all controls from military-recruited cohorts; and (4) patients with PTSD to all controls from civilian-recruited cohorts. Sample sizes for each analysis varied depending on data availability, such as the trauma exposure, of the controls. All group comparisons were adjusted for age and total ICV, as these variables account for the most variance in segmented GM and WM data.

Associations between regional brain volumes and clinical variables

The ENIGMA-VBM tool also conducted regression analyses to examine the association between regional brain volumes and clinical variables within the patient group. The regression analyses were performed within each cohort prior to being pooled for meta-analysis. This approach has greater statistical power than meta-regression, which uses a mean value of the clinical variable for each cohort.

We performed exploratory regression analyses to examine the associations between regional brain volumes and the following clinical covariates: PTSD severity, depression severity, childhood trauma, alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, and antidepressant medication use. Alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, and antidepressant medication were coded as dichotomous variables. PTSD severity, depression severity, and childhood trauma were analyzed using the participant’s total score for each variable. Further details regarding the treatment of the clinical variables are reported in Supplement A. All regression analyses were adjusted for age, ICV, and sex. Sex was included to adjust for potential associations with the clinical variables, as it is well-established that females are more likely to develop PTSD as compared to males [Reference Hapke, Schumann, Rumpf, John and Meyer28, Reference Christiansen and Berke29], and sex has been associated with PTSD comorbidities, including depression, alcohol use disorder, and drug use disorder [Reference Husky, Mazure and Kovess-Masfety30–Reference Olff, Langeland, Draijer and Gersons32].

Sensitivity analysis

The tool performed several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our findings against changes in VBM processing parameters including: (1) different smoothing kernels of 2, 4, and 12 mm; (2) different combinations of covariates of no interest (e.g., age and sex, or no covariates); (3) proportional scaling of voxels, where each voxel is scaled by the fraction of total ICV; and (4) using nonmodulated data.

For each analysis, the resulting statistical map contained the results for approximately 200,000 voxels, reflecting volumetric group differences or regression coefficients at each voxel.

Meta-analysis across cohorts

The statistical maps were pooled across cohorts for meta-analysis using the software Seed-based d-Mapping with Permutation of Subject Images (SDM-PSI v6.22; https://www.sdmproject.com) [Reference Radua, Mataix-Cols, Phillips, El-Hage, Kronhaus and Cardoner33]. In summary, the SDM-PSI process involves the following main steps: (1) statistical maps are converted to effect size maps using standard formulae; (2) the mean of the voxel values is calculated via random effects meta-analysis; and (3) a subject-based permutation test is conducted to family-wise error (FWE) correct for multiple comparisons using threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) with statistical thresholding (p < .025, voxel extent ≥ 10).

Total GM and WM volumes were compared between patients with PTSD and all controls using the unadjusted mean and standard deviation (SD) statistics at a cohort level as reported by the ENIGMA-VBM tool. The statistics from each cohort were pooled using an inverse-variance weighted random-effects model in STATA (release 17).

In sensitivity analyses, we repeated the meta-analysis of the main group comparison to exclude two non-adult cohorts, consisting of participants under the age of 20, to test for changes to our results. A further eight cohorts included participants who had been diagnosed with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), and we similarly repeated the main group comparison, excluding the affected participants (PTSD n TBI = 382, controls n TBI = 527) from our meta-analysis. We used a parcel-based correlation analysis [Reference Fortea, Ortuno, De Prisco, Oliva, Albajes-Eizagirre and Fortea34, Reference Whitcher, Schmid and Thornton35] in R (version 4.3.1) to calculate Pearson’s correlation coefficient to compare the spatial pattern of regional GM and WM differences between a given sensitivity analysis and our main group findings. Using a parcel-based approach mitigates the issue in voxel-based correlations where adjacent voxels are not independent. Further details are reported in Supplement A.

Results

All effect size and statistical maps are available online (https://neurovault.org/collections/QOAYXFZK/). The p values reported below are FWE-corrected for multiple comparisons using TFCE for the VBM analyses. The main findings are reported below, with full results and figures reported in Supplement A. Cohort sample characteristics are reported in Tables 1 and 2, and descriptive statistics for the clinical variables are reported in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5.

Group comparisons of regional brain volumes

PTSD versus controls

The main group comparison analyzed data from 35 cohorts comprising 1309 patients with PTSD and 2130 controls, inclusive of TE and nTE controls. Patients exhibited smaller GM volumes in a large cluster extending across the brain, encompassing the frontal and temporal lobes, thalamus, and cerebellum (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S6). Peak effects were observed in the left cerebellum (Hedges’ g = 0.22, pTFCE = .001, MNI [−4,−72,−10]) and right parahippocampus (Hedges’ g = 0.20, pTFCE = .001, MNI [22,−18,−24]). Patients exhibited smaller WM volumes in a single cluster within the cerebellum, with peak effects in the middle cerebellar peduncles (Hedges’ g = 0.14, pTFCE = .008, MNI [−16,−54,−38]) and left cerebellum (Hedges’ g = 0.14, pTFCE = .009, MNI [−6,−54,−18]) (Supplementary Table S6; Supplementary Figure S1). There were no regions where brain volumes were greater in patients than in controls.

Figure 1. Patients with PTSD exhibited lower regional gray matter volume compared to controls throughout the brain as seen in the orange highlighted regions in the figure, with a peak effect in the left cerebellum [−4,−72,-10] (see also Supplementary Table S6).

Patients with PTSD exhibited significantly lower total GM volume (Hedges’ g = −0.18, 95% CI [−0.29,−0.08], p = .001) (Supplementary Figure S2). There was no significant difference in total WM volume between groups (Supplementary Figure S3).

Subgroup analyses

In comparing 912 patients with PTSD to 1342 TE controls, patients exhibited smaller GM volumes in a similar spatial pattern to the main finding, and greater WM volumes within the corpus callosum (Supplementary Table S7; Supplementary Figure S4). When comparing 416 TE and 250 nTE controls, there were no significant GM or WM differences between groups.

In our analysis comparing patients with PTSD and controls from 19 military-recruited cohorts, the results were similar to the main findings, with patients exhibiting smaller GM volumes in a cluster across the frontal and temporal lobes, and cerebellum, and smaller WM volumes adjacent to the striatum (Supplementary Table S8; Supplementary Figure S5). In a separate analysis of 13 civilian-recruited cohorts, patients exhibited less widespread effects, with smaller GM volumes in the parahippocampus and cerebellum, and greater WM volumes within the corpus callosum (Supplementary Table S9; Supplementary Figure S6).

Associations between regional brain volumes and clinical variables in patients with PTSD

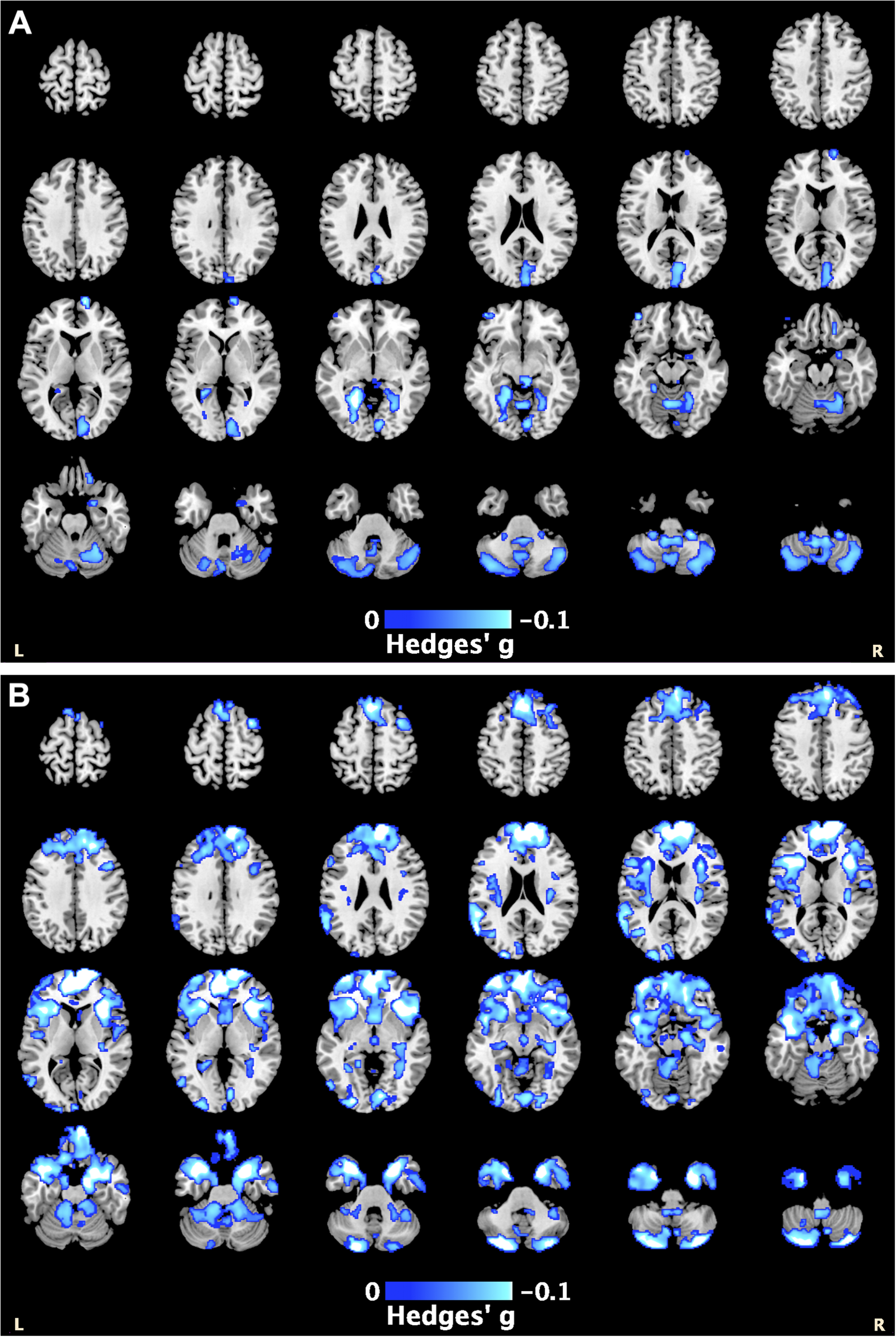

PTSD severity data were available for 35 cohorts (PTSD n = 1283). A higher PTSD severity score was associated with smaller GM volumes within the cerebellum, lingual gyrus, and superior frontal gyrus, with a peak effect in the right cerebellum (Hedges’ g = −0.11, pTFCE = .003, MNI [4,−48,−58]) (Figure 2A; Supplementary Table S10).

Figure 2. The blue highlighted regions represent smaller gray matter volumes associated with: (A) higher PTSD severity scores, with the peak effect in the right cerebellum [4,−48,−58]; and (B) higher depression severity scores, with the peak effect in the right superior frontal gyrus [14, 66, 6] (see also Supplementary Tables S12 and S13).

Depression severity data were available for 30 cohorts (PTSD n = 1023). Higher depression severity was associated with lower GM volumes within the frontal, temporal, and cerebellar regions, with a peak effect in the right superior frontal gyrus (Hedges’ g = −0.15, pTFCE = .001, MNI [Reference Salimi-Khorshidi, Smith, Keltner, Wager and Nichols14, Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller66, Reference Del Casale, Ferracuti, Barbetti, Bargagna, Zega and Iannuccelli6]) (Figure 2B; Supplementary Table S11).

680 patients with PTSD had available data on alcohol use disorder status, where 25.6% were identified as having an alcohol use disorder. Alcohol use disorder was associated with lower GM volumes within the cerebellum and temporal lobe, with a peak effect in the left fusiform gyrus (Hedges’ g = −0.15, pTFCE = .001, MNI [−34,−56,−6]) (Supplementary Table S12; Supplementary Figure S7).

364 patients with PTSD had available data on antidepressant medication, where 30.8% were identified as using antidepressant medication. We observed smaller GM volumes associated with antidepressant medication use in a small cluster within the left temporal gyrus, with a peak effect in the left inferior temporal gyrus (Hedges’ g = −0.17, pTFCE = .017, MNI [−60,−26,−18]) (Supplementary Table S13; Supplementary Figure S8).

There were no significant associations observed between GM volumes and childhood trauma (PTSD n = 507) or drug use disorder (PTSD n = 405). There were also no significant associations found between WM volumes and any of the clinical variables.

Sensitivity analysis

The spatial pattern of effect sizes was similar to that of the main findings for GM and WM when we excluded two nonadult cohorts from the analysis (Pearson’s r > 0.9) (Supplementary Table S14; Supplementary Figure S9). When we excluded participants with moderate-to-severe TBI, the spatial pattern of effect sizes was also similar to the main findings for GM and WM (Pearson’s r > 0.9) (Supplementary Table S15; Supplementary Figure S10). However, different WM clusters passed the significance threshold, where patients with PTSD exhibited significantly greater WM volumes within the corpus callosum. Patients still exhibited smaller WM volumes in the cerebellum as in the main findings, but these effects were no longer significant.

The results from the sensitivity analyses using different VBM parameters are reported in Supplement A (Supplementary Tables S16–S27; Supplementary Figures S11–S22). The correlation coefficients comparing the effect size maps from the sensitivity analyses to that of the main group comparison are reported in Supplementary Table S28. Using nonmodulated data effected the biggest change to our results (Pearson’s r > 0.49), while controlling for different covariates had a lesser effect on our results (Pearson’s r > 0.76). Using different smoothing kernels were in good agreement with our main result (Pearson’s r > 0.94).

Heterogeneity of the effect size

The extent of heterogeneity of the effect size was relatively low across the analyses. The main group comparison had a mean I2 of 8.15% across all GM voxels and of 4.67% across all WM voxels (Supplementary Figure S23). Heterogeneity is reported for each analysis in the tables within Supplement A, expressed as the mean I2 across all GM or WM voxels, and at the peak coordinates.

Discussion

Patients with PTSD exhibited smaller total GM volume than controls and in regions widespread across the brain with a peak effect in the cerebellum. Patients with PTSD had lower WM volumes within the cerebellum but exhibited no differences in total WM volume. We observed similar findings in comparing patients with PTSD to TE controls, but there were no differences between TE and nTE controls. Military-recruited cohorts exhibited group differences in similar GM regions as the main findings, while GM differences appeared to be less widespread in civilian-recruited cohorts. Regional GM volumes were negatively associated with PTSD severity, depression severity, alcohol use disorder, and antidepressant medication within patients with PTSD.

Regional and total brain volumes

Our findings are largely consistent with existing meta-analyses that found smaller total GM volumes in patients with PTSD compared to controls [Reference Bromis, Calem, Reinders, Williams and Kempton4–Reference Xiao, Yang, Su, Gong, Huang and Wang9], and with previous ENIGMA-PTSD FreeSurfer studies [Reference Logue, van Rooij, Dennis, Davis, Hayes and Stevens10, Reference Wang, Xie, Chen, Cotton, Salminen and Logue11], with effects in similar regions including the frontal lobe, cingulate cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala. However, comparisons with ROI studies are provided cautiously given the different methodologies of the present study relative to published studies. Our analysis revealed similar regional volume differences when we compared patients to TE controls, suggesting that these regions could be related to PTSD itself, rather than being associated with trauma exposure. This is further supported where we found no significant differences between TE and nTE controls. However, the smaller sample of nTE controls may have been underpowered to detect subtle differences between the control subgroups.

We observed lower GM and WM volumes within the cerebellum in patients, a finding not reported in previous VBM meta-analyses [Reference Bromis, Calem, Reinders, Williams and Kempton4–Reference Xiao, Yang, Su, Gong, Huang and Wang9]. From previous work, Serra-Blasco et al. [Reference Serra-Blasco, Radua, Soriano-Mas, Gomez-Benlloch, Porta-Casteras and Carulla-Roig8] reported significantly lower GM volumes in the cerebellum in patients with PTSD when compared to those with anxiety disorders, suggesting that this regional finding could be specific to PTSD. In ROI studies, the cerebellum is rarely included as it has been historically associated with motor control [Reference Schmahmann36]. The disparities between the current study and previous meta-analyses may be due to the increased power and homogeneity within the VBM processing in the current study from using the ENIGMA-VBM tool, or from differences in the sample characteristics. Notably, prior meta-analyses included 50–80% of samples from Europe and Asia [Reference Bromis, Calem, Reinders, Williams and Kempton4–Reference Xiao, Yang, Su, Gong, Huang and Wang9], while fewer than 15% of cohorts in the current study were from these regions. Our findings are consistent with individual neuroimaging studies that have reported smaller cerebellar volumes in patients with PTSD compared with controls [Reference Baldaçara, Jackowski, Schoedl, Pupo, Andreoli and Mello37–Reference Holmes, Scheinost, DellaGioia, Davis, Matuskey and Pietrzak39] and further complement the cerebellar mega-analysis by ENIGMA-PTSD, which used a novel parcellation protocol to reveal smaller brain volumes within the cerebellum and its substructures associated with PTSD [Reference Huggins, Baird, Briggs, Laskowitz, Hussain and Fouda12]. Previous functional MRI studies have also found evidence of resting-state dysfunction in the cerebellum in patients with PTSD [Reference Wang, Liu, Zhang, Zhan, Li and Wu40, Reference Koch, van Zuiden, Nawijn, Frijling, Veltman and Olff41] and cerebellar activation in response to fear [Reference Lange, Kasanova, Goossens, Leibold, De Zeeuw and van Amelsvoort42, Reference Moreno-Rius43]. The cerebellum is becoming an increasingly important structure in PTSD [Reference Blithikioti, Nuno, Guell, Pascual-Diaz, Gual and Balcells-Olivero44], with rich connections to regions that are often implicated in stress and trauma such as the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex [Reference Moreno-Rius45].

In examining only military-recruited cohorts, regional GM differences between patients and controls appeared to be more widespread compared to differences observed in civilian-recruited cohorts. This may be driven by characteristics specific to military populations, where previous work has reported lower cortical thickness in veterans with and without PTSD [Reference Wrocklage, Averill, Cobb Scott, Schweinsburg and Trejo46] and smaller GM volumes associated with longer military deployment in personnel without PTSD [Reference Butler, Adolf, Gleich, Willmund, Zimmermann and Lindenberger47]. Our results highlight the importance of considering sample characteristics in future neuroimaging studies and may explain why our findings differ from previous work. For instance, Bromis et al. [Reference Bromis, Calem, Reinders, Williams and Kempton4], who similarly meta-analyzed statistical maps, included mostly civilian studies with only 2 military-recruited cohorts, while the current study consisted of 19 military-recruited cohorts.

GM associations with clinical variables

PTSD severity was negatively associated with GM volumes in posterior regions, including the cerebellum, consistent with individual ROI studies [Reference Baldaçara, Jackowski, Schoedl, Pupo, Andreoli and Mello37–Reference Holmes, Scheinost, DellaGioia, Davis, Matuskey and Pietrzak39], and the ENIGMA-PTSD cerebellar mega-analysis [Reference Huggins, Baird, Briggs, Laskowitz, Hussain and Fouda12]. However, our findings contrast with those from a large meta-analysis by Xiao et al. [Reference Xiao, Yang, Su, Gong, Huang and Wang9] reported associations with the ACC instead. This could be due to methodological differences where the authors used a coordinate-based meta-regression, while in the current study, the regression analysis was conducted within each cohort prior to pooling the resulting statistical maps, which was expected to increase statistical power and sensitivity.

Depression severity was associated with smaller GM volumes in both posterior and frontal regions of the brain. The latter finding may be relevant to functional MRI findings of decreased connectivity within the frontal lobe in PTSD patients with depression [Reference Zhu, Helpman, Papini, Schneier, Markowitz and Van Meter48, Reference Ploski and Vaidya49]. Alcohol use disorder was associated with smaller GM volumes, mainly within the cerebellum, which contrasts with previous work that found associations with the ACC [Reference Klaming, Harle, Infante, Bomyea, Kim and Spadoni50]. The negative associations between symptom severity and regional brain volumes indicate that structural abnormalities may exist on a continuum, where patients with more severe symptoms may exhibit greater structural changes within the brain. It is interesting to note that the cerebellum was negatively associated with both depression severity and alcohol use disorder, common comorbidities for PTSD [Reference Walter, Levine, Highfill-McRoy, Navarro and Thomsen51, Reference Karatzias, Hyland, Bradley, Cloitre, Roberts and Bisson52]. This suggests that the cerebellum findings are specific to PTSD, with comorbidities potentially affecting further morphological changes. Future work is needed to determine the direction of effect and whether cerebellar abnormalities represent vulnerability factors or consequences of PTSD.

Sensitivity analyses

We found the significance of the GM results was generally consistent across the sensitivity analyses, while the significance of the WM findings was less robust. The use of nonmodulated data resulted in the biggest difference in results, where findings were only moderately correlated with the main results (r = 0.558), with a smaller cluster of significant differences observed in the cerebellum. This may be expected given modulated data has been reported as more sensitive to identifying volumetric differences, while nonmodulated data may be more sensitive to detecting changes in cerebral cortical thickness [Reference Mechelli, Price, Firston and Ashburner53, Reference Radua, Canales-Rodriguez, Pomarol-Clotet and Salvador54]. We also compared findings using varying smoothing kernel sizes of 2, 4, and 12 mm, where we observed greater spatial extent of significant clusters in regional brain volume differences with larger kernel sizes. In the current study, we have used Pearson’s correlation to compare the spatial pattern of effect sizes between analyses, but future studies investigating the reliability of VBM parameters may consider using the intraclass correlation instead [Reference Hedges, Dimitrov, Zahid, Brito Vega, Si and Dickson55, Reference Morey, Selgrade, Wagner, Huettel, Wang and McCarthy56].

Limitations

The ENIGMA-VBM tool is designed to run locally at each site, meaning analyses are prespecified, which means we did not examine the interaction between PTSD and sex. Greater consideration of sex is required in future work [Reference Haering, Schulze, Geiling, Meyer, Klusmann and Schumacher57], given the evidence for sex differences in PTSD prevalence [Reference McGinty, Fox, Ben-Ezra, Cloitre, Karatzias and Shevlin22, Reference Blanco, Hoertel, Wall, Franco, Peyre and Neria23], symptom presentation [Reference Christiansen and Berke29, Reference Olff, Langeland, Draijer and Gersons32], and associated risk factors [Reference Haering, Seligowski, Linnstaedt, Michopoulos, House and Beaudoin58]. We were also unable to consider the type or incidence of trauma exposure, or the age of PTSD onset, as not all studies collected these data. It would be beneficial if these variables could be included in future studies, given the complexities surrounding the timing and experience of trauma in relation to the onset and severity of PTSD [Reference Utzon-Frank, Breinegaard, Bertelsen, Borritz, Eller and Nordentoft59]. The majority of our studies were recruited in the United States, which limits the generalizability of our results, particularly given differences in PTSD prevalence [Reference Koenen, Ratanatharathorn, Ng, McLaughlin, Bromet and Stein60] and in the types of commonly reported traumatic events [Reference Benjet, Bromet, Karam, Kessler, McLaughlin and Ruscio1] across countries. The current study is based on cross-sectional data, making it unclear whether the observed structural abnormalities represent vulnerability factors for PTSD and/or are consequences of the illness, which can be clarified with longitudinal studies.

We have conducted the largest PTSD meta-analysis to date using whole-brain VBM statistical maps, further strengthened in the homogeneity of the VBM processing pipeline via the ENIGMA-VBM tool. The 3D effect size and statistical maps from the current study are available online. Our results revealed that patients with PTSD exhibited smaller GM volumes across the brain as compared to controls and support the growing literature implicating the cerebellum in PTSD.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.10062.

Data availability statement

The 3D effect size maps and statistical maps are available online: https://neurovault.org/collections/QOAYXFZK/.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the original investigators who collected the cohort data, the individuals who were scanned, and to the ENIGMA consortium.

Author contribution

Conceptualization, C.R.Z.S., A.J., P.M.T., R.A.M., and M.J.K.; Methodology, C.R.Z.S., S.Si, J.R., N.J., A.J., P.M.T., R.A.M., and M.J.K.; Software, C.R.Z.S., J.R., and M.J.K.; Formal Analysis, C.R.Z.S., S.Si, R.V.L, and E.L.D.; Investigation, C.R.Z.S. and M.J.K.; Data Curation, C.R.Z.S, C.L.B, and A.H.; Supervision, L.V. and M.J.K.; Project Administration, C.R.Z.S., S.I.T., R.A.M., and M.J.K.; Funding Acquisition, C.R.Z.S., P.M.T., and R.A.M; Writing – Original Draft, C.R.Z.S.; Resources (Data Collection), C.L.B., C.C.H., A.H., M.O., D.J.V., J.L.F., M.V.Z., S.B.J.K., L.N., L.W., Y.Z., G.L., Y.N., X.Z., B.S., S.Z., A.L., J.S.Stevens, K.J.R., N.F., T.J., S.J.H.V.R., M.L.K., L.A.M.L., I.M.R., E.A.O., J.T.B., S.R.S., S.G.D., N.D.D., A.E., A.M., M.B.S., M.E.S., D.J.S., J.I., S.K., S.L., H.B., T.S., D.B.H., L.A.B., G.L.F., R.M.S., J.S.Simons, V.A.M., K.A.F., X.W., A.S.C., E.N.O., H.X., D.W.G., J.B.N., R.J.D., C.L.L., T.A.D., C.W.T., J.M.F., J.U.B., B.O.O., E.M.G., G.M., S.M.N., R.L., J.T., M.D., R.W.N., C.G.A., C.L.A., I.H., I.L., J.H.K., E.G., R.V.L., E.L.D., D.F.T., D.X.C., W.C.W., E.A.W., N.J.A.V.D., R.R.J.V., S.J.A.V.D., K.M., K.S., M.P., L.E.S., N.J., S.I.T., and R.A.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, C.R.Z.S., S.Si, C.L.B., C.C.H., A.H., M.O., D.J.V., J.L.F., M.V.Z., S.B.J.K., L.N., L.W., Y.Z., G.L., Y.N., X.Z., B.S., S.Z., A.L., J.S.Stevens, K.J.R., N.F., T.J., S.J.H.V.R., M.L.K., L.A.M.L., I.M.R., E.A.O., J.T.B., S.R.S., S.G.D., N.D.D., A.E., A.M., M.B.S., M.E.S., D.J.S., J.I., S.K., S.Seedat, S.D.P., L.L.V.D., S.L., H.B., T.S., D.B.H., L.A.B., G.L.F., R.M.S., J.S.Simons, V.A.M., K.A.F., X.W., A.S.C., E.N.O., H.X., D.W.G., J.B.N., R.J.D., C.L.L., T.A.D., C.W.T., J.M.F., J.U.B., B.O.O., E.M.G., G.M., S.M.N., R.L., J.T., M.D., R.W.N., C.G.A., C.L.A., I.H., I.L., J.H.K., E.G., R.V.L., E.L.D., D.F.T., D.X.C., W.C.W., E.A.W., N.J.A.V.D., R.R.J.V., S.J.A.V.D., K.M., K.S., M.P., J.R., L.E.S., N.J., S.I.T., A.J., L.V., P.M.T., R.A.M., and M.J.K.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Department of Defense (Grant Nos. R01MH111671, R01MH117601, R01AG059874, and MJFF 14848) to N Jahanshad and (Grant No. W81XWH-12-2-0012) to S Thomopoulos and P Thompson; ENIGMA was also supported in part by NIH U54 EB020403 from the Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) program (R56AG058854, R01MH116147, R01MH111671, and P41 EB015922) to S Thomopoulos and P Thompson; ZonMw, the Netherlands organization for Health Research and Development (40-00812-98-10041), and by a grant from the Academic Medical Center Research Council (110614) both awarded to M Olff; The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U21A20364 and 31971020), the Key Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 20ZDA079), the Key Project of Research Base of Humanities and Social Sciences of Ministry of Education (No. 16JJD190006), and the Scientific Foundation of Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. E2CX4115CX) to L Wang and Y Zhu; National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. NIMH K01 MH118428) and NARSAD Young Investigator Award to B Suarez-Jiminez; NARSAD (Grant No. 27040) and K01MH122774 to X Zhu; NIMH (Grant No. R01MH105355-01A) to Y Neria; The National Institutes of Health (R01 MH111671) and VA Mid-Atlantic MIRECC to R Morey, C Baird, A Hussain, and C Haswell; The National Institute of Mental Health (Grants Nos. MH098212 and MH071537), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Grant No. UL1TR000454), National Center for Research Resources (Grant No. M01RR00039), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant Nos. HD071982 and HD085850) to J Stevens, K Ressler, T Jovanovic, S van Rooij; The National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. MH101380) to N Fani; K01MH118467 and Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research to L Lebois; R21MH112956 and R01MH119227, Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research, McLean Hospital Trauma Scholars Fund, and Barlow Family Fund to M Kaufman; R01 MH096987 to I Rosso; W81XWH08-2-0159 (PI: Stein, Murray B) from the US Department of Defense to M Shenton and M Stein; R61NS120249 to E Dennis, D Tate, and E Wilde; The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs endorsed by the Department of Defense, through the Psychological Health/Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium (LIMBIC) Award/W81XWH-18-PH/TBIRP-LIMBIC under (Grant Nos. W81XWH1920067, W81XWH-13-2-00950), and HFP90-020 to E Wilde; The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (Grant Nos. I01 CX002097, I01 CX002096, I01 CX001820, I01 HX003155, I01 RX003444, I01 RX003443, I01 RX003442, I01 CX001135, I01 CX001246, I01RX001774, I01 RX001135, I01 RX002076, I01 RX001880, I01 RX002172, I01 RX002173, I01RX 002171, I01 RX002174, and I01 RX002170) and The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 839 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office to W Walker; Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Centers, the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC; W81XWH-13-2-0025) and the Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (CENC; PT108802-SC104835) to D Cifu; VA Rehabilitation Research and Development (RR&D) (Grant Nos. 1IK2RX000709 to N Davenport, 1K2RX002922 to S Disner, and I01RX000622 to S Sponheim); Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs Grant No. W81XWH- 08–2–0038 to S Sponheim; German Research Society - Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft: DFG (Grant No. SFB/TRR 58: C06, C07) to D Hofmann and T Straube; The Department of Defense (Grant Nos. W81XWH-10-1-0925), Center for Brain and Behavior Research Pilot Grant, and South Dakota Governor’s Research Center Grant to L Baugh, G Forster, R Simons, J Simons, V Magnotta, K Fercho; The SAMRC Unit on Risk & Resilience in Mental Disorders to D Stein; The South African Medical Research Council for the “Shared Roots” Flagship Project, (Grant no. MRC- RFA-IFSP-01-2013/SHARED ROOTS) through funding received from the South African National Treasury under its Economic Competitiveness and Support Package to S Seedat, S du Plessis, L van den Heuvel. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the South African Medical Research Council. S Seedat is supported by the South African Research Chairs Initiative in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder through the Department of Science and Innovation and the National Research Foundation. The work by L van den Heuvel reported herein was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant Number 138430) and by the South African Medical Research Council under a Self-Initiated Research Grant. The content hereof is the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the SAMRC or the funders; 1R01MH110483 and 1R21 MH098198 to X Wang; R01MH107382–02 to S Lissek; Dana Foundation to J Nitschke; A National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to D Grupe; the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (Grant Nos. R01-MH043454 and T32-MH018931) to R Davidson; and a core grant to the Waisman Center from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P30-HD003352); R01 MH106574 to C Larson and T deRoon-Cassini; NIMH (Grant No. R21MH106998) to J Blackford and B Olatunji; VA Clinical Science Research and Development (Grant No. 1IK2CX001680) and VISN17 Center of Excellence pilot funding to E Gordon, G May and S Nelson; VA National Center for PTSD and the Beth K and Stuart Yudofsky Chair in the Neuropsychiatry of Military Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome to C Abdallah; 1R21MH102634 to I Levy; R01MH105535 to I Harpaz-Rotem; Department of Veterans Affairs via support for the National Center for PTSD, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism via its support for (P50) Center for the Translational Neuroscience of Alcohol, and NCATS via its support of (Clinical and Translational Science Awards) Yale Center for Clinical Investigation to J Krystal; CIHR and CIMVHR grants to R Lanius; C See is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MR/N013700/1) and King’s College London member of the MRC Doctoral Training Partnership in Biomedical Sciences. This study represents independent research, partly funded by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. For the purposes of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license to any Accepted Author Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Competing interests

N Jahanshad received partial research support from Biogen, Inc. (Boston, USA) for research unrelated to the content of this article. P Thompson received partial research support from Biogen, Inc. (Boston, USA) for research unrelated to the topic of this manuscript. R Davidson is the founder and president of, and serves on the board of directors for, the non-profit organization Healthy Minds Innovations, Inc. L Lebois reports unpaid membership on the Scientific Committee for the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD), grant support from the National Institute of Mental Health, K01 MH118467, and spousal IP payments from Vanderbilt University for technology licensed to Acadia Pharmaceuticals unrelated to the present work. ISSTD and NIMH were not involved in the analysis or preparation of the manuscript. C Abdullah has served as a consultant, speaker and/or on advisory boards for Douglas Pharmaceuticals, Freedom Biosciences, FSV7, Lundbeck, Psilocybin Labs, Genentech, Janssen and Aptinyx; served as editor of Chronic Stress for Sage Publications, Inc; and filed a patent for using mTOR inhibitors to augment the effects of antidepressants (filed on August 20, 2018). J Krystal is a consultant for AbbVie, Inc., Amgen, Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Biomedisyn Corporation, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Euthymics Bioscience, Inc., Neurovance, Inc., FORUM Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Research & Development, Lundbeck Research USA, Novartis Pharma AG, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc., Sage Therapeutics, Inc., Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Takeda Industries; is on the Scientific Advisory Board for Lohocla Research Corporation, Mnemosyne Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Naurex, Inc., and Pfizer; is a stockholder in Biohaven Pharmaceuticals; holds stock options in Mnemosyne Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; holds patents for Dopamine and Noradrenergic Reuptake Inhibitors in Treatment of Schizophrenia, US Patent No. 5,447,948 (issued September 5, 1995), and Glutamate Modulating Agents in the Treatment of Mental Disorders, U.S. Patent No. 8,778,979 (issued July 15, 2014); and filed a patent for Intranasal Administration of Ketamine to Treat Depression. U.S. Application No. 14/197,767 (filed on March 5, 2014); US application or Patent Cooperation Treaty international application No. 14/306,382 (filed on June 17, 2014). Filed a patent for using mTOR inhibitors to augment the effects of antidepressants (filed on August 20, 2018). S Nelson consults for Turing Medical, which commercializes FIRMM. This interest has been reviewed and managed by the University of Minnesota in accordance with its Conflict of Interest policies. E Olson is employed by the nonprofit organization Crisis Text Line, for work unrelated to the content of this manuscript. All other authors report no potential competing interests or disclosures.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.