A. Introduction

A person’s recognition as a refugee under the 1951 Geneva Refugee ConventionFootnote 1 frequently depends on the question whether the applicant’s account of their persecution is credible.Footnote 2 Decision-makers need to decide whether the account given by the applicants can form the factual basis on which to assess the risk of persecution, should they be returned to the country of origin.

To determine whether the applicant’s account in an asylum case is credible, i.e., whether it should be believed for the purposes of the proceedings, so-called credibility criteria are used; in particular, the consistency of the applicant’s account and its plausibility. While difficult to apply under the best of circumstances, these criteria are often subject to distortive factors. For example, mistakes by the interpreter or in the transcript of the applicant’s interview can produce the false impression of inconsistencies. Credibility criteria and distortive factors can be ambivalent, contradictory, and thus need to be balanced in the individual case to arrive at a decision. Like other legal balancing processes, credibility assessment is criticized for its subjectivity (B.). Credibility criteria are well-established in the case law of many jurisdictions, and not only in asylum law. But research on the issue of credibility determination has mostly been qualitative so far (C.).

This article empirically analyzes a sample of German asylum cases that is available in the most authoritative German legal database Juris.Footnote 3 Such an empirical approach is particularly called-for in this area because the number of decisions that are published is so large that it cannot be comprehensively analyzed in a qualitative fashion. In fact, there are so many cases that even an empirical approach must be limited in scope. While the database does not contain all decisions that are actually taken, Juris is the most relevant legal database that is used by courts and practitioners, shaping their view of the law. The approach followed here can shine a light on a larger part of that case law and thus produce insights that might otherwise be missed.

This article is the result of a quantitative assessment of 236 German asylum cases that dealt with credibility assessment in the year 2017 (D.). The reasoning which the German administrative courts gave in these cases was analyzed, first, to determine which credibility criteria were actually used in practice. Second, it was assessed whether and to what extent confounding factors that might distort the application of credibility criteria were taken into account by the judge according to the decision’s reasons. Concluding Observations on the limits of objectivity in decision-makers will close this article (E.).

B. Credibility Assessment in German Asylum Cases

This Section will introduce the credibility criteria (also called “reality criteria”)Footnote 4 that are generally accepted in the literature as well as in the practice of various national and international courts (I.). The confounding factors that could potentially distort their assessment will be described thereafter (II.). The Section will close by pointing out the balancing character of this assessment and the purpose that asylum interviews serve in this regard (III.).

I. Credibility Criteria

The credibility criteria that are used to determine whether the applicant’s account should be believed for the purposes of refugee status determination can be divided into two general categories: Those criteria that are based on the account’s content (1.) and those based on the applicant’s conduct, during the interview or otherwise (2.).

1. Content-Based Criteria

The credibility assessment conducted by German administrative courts is based on a premise that is known in Germany as the “Undeutsch hypothesis.” Developed by and named after the psychologist Udo Undeutsch (1917–2013),Footnote 5 this hypothesis states that there are differences in content between a factual account that is given by a person who did actually experience what that person describes, and an account by a person who describes a situation which that person did not experience.Footnote 6 Simply put, the hypothesis is based on the assumption that it is difficult to lie in a manner that does not recognizably differ from a subjectively true account with regard to its content.Footnote 7 Something that was really experienced can, in principle, be retold from memory. Invented accounts must be, at least partially, constructed from one’s general knowledge about the world.Footnote 8 This is, for example, why seemingly unimportant details are mostly avoided when lying.Footnote 9 Outside of Germany, empirical research starts from a similar premise, namely that it is, in general, more emotionally stressful and/or more cognitively challenging to lie than to tell the truth.Footnote 10

Regularly referencing a standard work authored by practicing judges, i.e. Bender et al., “Tatsachenfeststellung vor Gericht” (Fact-finding Before Courts),Footnote 11 German administrative courts consider that the “Undeutsch hypothesis” and the credibility criteria based on it have “proven themselves.”Footnote 12 It is accepted as the basis of all credibility determinations conducted by German courts, either explicitly as a “scientifically confirmed insight” or at least implicitly by the application of content-related credibility criteria—which this study provides clear confirmation for.Footnote 13 The German Federal Agency for Refugees and Migration (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge—in the following: Federal Agency) trains its decision-makers on this basis.Footnote 14 Outside of Germany, criteria similar to those expounded in Bender et al. are generally accepted.Footnote 15

But despite their practical importance, the validity of the Undeutsch hypothesis and its credibility criteria has, in fact, not been entirely confirmed in empirical research. In some controlled experiments, credibility assessments following these criteria were wrong about 30 % of the time.Footnote 16 However, such studies conducted the credibility assessment based on a written interview transcript, which makes the application of credibility criteria considerably more difficult. Such a study design omits the arguably most important aspect of credibility assessment: The asylum interview which serves an indispensable function in this regard.Footnote 17 But at least a general connection between a truthful account and positive credibility criteria has been confirmed.Footnote 18 The most evidence seems to currently exist for the criterion relating to an account’s level of detail.Footnote 19

All of the content-based credibility criteria that are applied in the asylum systems of Germany and many other states are an emanation of the following two general criteria: Consistency and plausibility. First, decision-makers take into consideration whether an account is consistent, i.e. free from logical contradiction: With itself, internally, but also with other evidence, externally. For example, if an attack is described, in a first interview before the Federal Agency as having been conducted with “long sticks” and then, before the reviewing court, as conducted with “long knives,” this is, prima facie, a logical contradiction.Footnote 20 Second, it is relevant whether an account is plausible. In its most general form, plausibility assesses the likelihood of certain events or circumstances, in particular, how coherent an account seems. For example, “the sheer improbability of one individual wresting himself from a guard, leaving his clothes in the guard’s hand, then evading another five of them, vaulting a two-metre wall, with no one shooting at him, even to wound him, or shouting for others to come” is a factor that speaks against the account’s credibility.Footnote 21

While plausibility in its most general form is often heavily criticized as a credibility criterion for its apparent subjectivity, three more specific emanations of the plausibility criterion are generally accepted and play an important role in the practice of refugee status determination: The level of detail and the level of knowledge that can be expected from the applicant, as well as the timeliness of the claim.

If someone really experienced a certain situation, they will, in general, be able to supplement the account with further information. This information concerns, first, details of the specific event or the general circumstances that a person claims to have experienced. But this can also concern, second, more general, context-independent factual knowledge. For example, if someone states that they handled sensitive political and financial issues for a political party, they should be able to describe their activities with more than just platitudes and could be expected to have some general knowledge about finances.Footnote 22 Details and knowledge that can be expected from a credible applicant are particularly important in cases concerning persecution due to one’s sexual orientationFootnote 23 or religious conversionFootnote 24 . In these often difficult cases, the person’s very identity or inner conviction are at issue. For the former, a model was developed by the attorney S. Chelvan,Footnote 25 which is accepted by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as well as the European Asylum Support Office (EASO).Footnote 26 It structures personal experiences that non-heterosexual persons regularly make into certain elements that can be taken into account in credibility assessment: Difference, stigma, shame, and harm (DSSH model).Footnote 27

Third, an “untimely” claim is known in German asylum law as an “increased” claim (Steigerung). This means that the account that was initially given is “increased” either by adding further acts of persecution or by claiming more serious versions of the original account later in the proceedings.Footnote 28 Because it is prima facie implausible why these new facts were not advanced earlier, this is taken to be an indicator against the account’s credibility.

All of these criteria are accepted internationally, for example by the UNHCR,Footnote 29 EASO,Footnote 30 the International Association of Refugee Law Judges (IARLJ),Footnote 31 and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).Footnote 32 But the literature often splits these criteria into many more categories. Bender et al., the German standard reference work, distinguishes between criteria relating to the content and structure of the account, and further divides these into many more categories.Footnote 33 Aldert Vrij mentions no less than nineteen criteria.Footnote 34 But all of the criteria that are mentioned in this literature, and relevant for asylum law, can be covered by the simplified categorization advocated for here. Further differences could be made within these categories if need be. The qualitative analysis already undertaken suggests that this simplified version better reflects how credibility criteria are used in asylum law practice.Footnote 35 The quantitative analysis undertaken here also served to test the adequacy of this systematization by considering whether additional (sub-)categories were necessary to adequately take into account the practice of credibility assessment.

2. Conduct-Based Criteria

In addition to the generally accepted content-based credibility criteria, conduct-based criteria are sometimes used: The conduct of a person during the asylum interview, before the Federal Agency or at court,Footnote 36 and the applicant’s personal or general credibility.

First, the conduct of the applicant during an asylum interview concerns communicative behavior beyond the meaning of the words that are spoken. This demeanor can be non-verbal, as avoiding eye contact, but it can also be the way something is said, e.g. long pauses between sentences or the volume and speed of speech.Footnote 37 This criterion has widely and for a long time been criticized as unreliable, a critique which will be developed in more detail below. Nonetheless, it is an accepted credibility criterion, not only in asylum cases.Footnote 38 In the USA, the law expressly recognizes that a person’s “demeanor, candor, or responsiveness” can be taken into account in asylum cases.Footnote 39 The ECtHR accepts it as well. Much as US federal courts,Footnote 40 the ECtHR sees it as a reason to widen the margin of appreciation that national authorities enjoy because only they perceived this conduct.Footnote 41

Second, German theory distinguishes between the account’s credibility (Glaubhaftigkeit) and a person’s credibility (Glaubwürdigkeit).Footnote 42 Thus, not only the account’s credibility but the credibility of the person telling it is a criterion used in German asylum law, and in other branches of the law. Widely criticized, this criterion is nonetheless generally accepted as well, in particular by the German Federal Constitutional Court.Footnote 43 Other national courts, e.g. in CanadaFootnote 44 and the UK,Footnote 45 have accepted it, just as the ECtHR which refers to it as “general” or “personal credibility.”Footnote 46 Article 4 (5) Qualification Directive (QD)Footnote 47 likewise refers to “general credibility.”

II. Confounding Factors

Anyone conducting a credibility assessment must be aware of confounding factors. Some of these confounding factors are general and applicable to credibility assessment in all areas of law, others are rather specific to asylum cases. For example, memory may fail anyone, especially concerning the details of an event after some time has passed.Footnote 48 Even more, our memory is never a photorealistic copy of reality but focuses on the perceptions that seemed important to us at the time.Footnote 49 Therefore, there is no general rule which details of a situation must be remembered in a credible account; age, gender, education, and other aspects of one’s socialization may all have an impact.Footnote 50 While crucial events in our lives will generally engrave themselves deeper in our memory,Footnote 51 someone who suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder might present an account that is internally inconsistent or exhibits other negative credibility criteria.Footnote 52

Mistakes by interpreters, whose assistance is almost always necessary in asylum cases, can likewise create the appearance of negative credibility criteria, e.g. inconsistencies or a lack of detail.Footnote 53 Such mistakes can be hard to detect because usuallyFootnote 54 only one of the persons present at the interview speaks both languages: The interpreter.Footnote 55

Cultural distance between the applicant and the decision-maker can be an issue for credibility determination, too.Footnote 56 What kind of “story-telling” is perceived as credible can differ between cultures, e.g. how emotionally or directly an event is recounted.Footnote 57 It can be more common in one culture to give additional details about one’s own experience and emotions, and in another culture the focus may lie on details about social interactions; it may be normal to give more or less context. All of this may affect the level of detail of the account—and also what is remembered because it seemed important at the time.Footnote 58 Specific dates might be less important in some cultures and therefore less well remembered.Footnote 59 It is a problem often described in the literature on credibility determination in asylum cases that the applicant who wants to tell something that is important from their point of view is interrupted because the interviewer considers it to be irrelevant.Footnote 60 International criminal courts have noticed this problem as well: The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda explicitly acknowledged that questions are not always answered directly in Rwanda, specifically when they concern sensitive issues.Footnote 61 The demeanor during an interview can likewise be culturally contingent, in particular gestures and facial expressions.Footnote 62 Looking down, for example, is considered to be a sign of respect towards authorities in Hispanic cultures—but is often taken as a “cue” for lying in other Western cultures.Footnote 63

Confounding factors are thus a substantial challenge in credibility determination. But the mere possibility that distortive factors could generally have an influence on credibility assessment does not per se invalidate the credibility criteria, as is sometimes argued.Footnote 64 Just because confounding factors could, abstractly speaking, be present in any case, that does not mean that they are present in all cases. Nor does it mean that it is impossible to know to a reasonable degree of certainty in which cases they are present. It also does not mean that it is impossible to mitigate them or know the limits of their impact. For example, if it is reasonable to assume that dates cannot be remembered well, it can be asked instead if something happened before or after a key event, e.g. a wedding.Footnote 65 Even traumatic events do not always lead to memory loss,Footnote 66 and the periphery of a traumatic event, what happens before or after it, can generally be remembered.Footnote 67

III. Balancing and the Purpose of the Asylum Interview

Credibility assessment is a very complex balancing operation. The criteria can initially be ambivalent and contradictory. To arrive at a decision, the criteria therefore need to be clarified and balanced against each other, together with possible confounding factors—which is often described as the need to consider all criteria and confounding factors “in the round.”Footnote 68 The process of carefully balancing credibility criteria, while taking into account distortive factors, is what differentiates this type of content-based credibility assessment from common beliefs about “lie detection” that even professional decision-makers are prone to succumb to. The existence of any one negative credibility criterion must not be overvalued. For example, a slight contradiction cannot in itself make the entire account incredible.Footnote 69

With regard to the balancing thus required, the asylum interview before the Federal Agency or at court serves three central purposes. First, it generates the account and thus the object of credibility assessment. Second, it is supposed to generate further and sufficiently clear credibility criteria to determine whether the account is credible or not. Abstractly, the credibility criteria can seem ambivalent: Consistency, relevant knowledge, and a high level of detail are valued as positive criteria, but too much consistency, too many details and a certain kind of knowledge can make the impression of an invented, rehearsed story.Footnote 70 In the interview, the criteria should become more unequivocal, or should be supplemented by additional indicators that enable a well-founded decision. Third, during the interview, decision-makers need to clarify whether there is reason to believe that negative credibility criteria are based on confounding factors—and therefore do not weigh against the account’s credibility. For example, an inconsistency in the account might be explained by a simple translation error.

C. Empirical Research on Credibility Criteria So Far

There is no official data on the application of credibility criteria in Germany. The Federal Agency publishes annual statistics, but they just contain general information such as the number of cases, the applicants’ countries of origin, and their success rate. Not even the reasons for which asylum was claimed are documented statistically.Footnote 71 The statistics that are published on a European level by EASO do not relate to credibility criteria either.Footnote 72

In Germany, case law is rarely studied quantitatively.Footnote 73 But it has been found that recognition rates can vary significantly between individual decision-makers.Footnote 74 It has also been shown that acceptance rates vary significantly between the German states (Länder)—which some call the “dark side” of federalism, because applicants cannot choose in which state their case will be heard.Footnote 75 The general atmosphere with regard to refugees was taken to have an influence on whether an application is granted or rejected.Footnote 76 One study even found that in German states long governed by the social democrats of the SPD rejection rates are lower in administrative courts, indicating—according to the authors—that “partisanship is a factor to be reckoned with.”Footnote 77 A further study found that males, Muslims, and persons whose status determination was conducted in more conservative areas of Germany were less likely to receive a protective status. The study considered this to reveal “taste-based discrimination,” i.e. a decision based on extra-legal reasons, such as stereotypes and prejudice. Such decisions were seen to be more prevalent among decision-makers under a high workload or who disposed of little information.Footnote 78 But specifically with regard to their credibility assessment, German asylum decisions have not been quantitatively analyzed thus far, neither the decisions by the Federal Agency nor those by the administrative courts.

While a quantitative analysis of decision-making has been more prominently conducted for the case law and voting behavior of judges at constitutional courts,Footnote 79 some academic literature outside of Germany has begun to explore the nature and conduct of credibility assessment in asylum cases. In particular, members of York University’s Centre for Refugee Studies in Toronto, Canada, pioneered research on this issue.

Sean Rehaag and Hilary Evans Cameron investigated the impact of prejudice on credibility assessment in an experiment. They showed a fictitious asylum case file to 284 Canadian first-year law students. The students’ task was to determine the credibility of the fictional applicant who claimed to be homosexual. The case file included positive as well as negative credibility criteria, so as to make it possible to decide either way. One group of students was explicitly advised not to take into account stereotypes concerning the applicant’s appearance, the other was not. Both groups were again divided into three sub-groups, which were shown either no photo of the applicant, a photo that showed someone who conformed to Western stereotypes of a homosexual person or a photo that did not do so.

Despite certain limitations,Footnote 80 the experiment yielded interesting insights. Only one person explicitly referred to the applicant’s looks, which they took to support the claim. Thus, almost all students knew that they should not base their decision on this factor—regardless of whether they belonged to the group that had received advice on this issue or not. The group that saw a photo that conformed to homosexual stereotypes was nonetheless more likely to consider the applicant credible (88 % of this group did) than those who saw a photo meant to be stereotypically “heterosexual” (only 75.5 % of this group did). 85.3 % of the control group with no photo considered the applicant credible.Footnote 81

Sean Rehaag also researched the infamous case of the Canadian decision-maker McBean. In three years, McBean rejected all 174 asylum claims that he decided. Of all these applicants, 116 were denied refugee status for a lack of credibility. Pointing to a lack of details and inconsistencies, often with regard to dates or the exact number of attackers during an act of persecution, the decision-maker without fail came to the result that “I simply do not believe …”Footnote 82 The likelihood that all these asylum claims were indeed unfounded is close to zero.Footnote 83

Finally, Jenni Millbank of the University of Technology in Sydney, Australia, analyzed 1,000 credibility determinations in asylum cases decided in Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, and New Zealand concerning the applicants’ sexual orientation.Footnote 84 In particular, the 149 Canadian cases showed that legal counsel can make a difference: Those applicants who were not represented by counsel were successful in only 2.3 % of cases; those represented by counsel were successful in 29 % of cases. 56 % of applicants did not have a lawyer.Footnote 85

D. An Empirical Study of Credibility Assessment

Inspired by the research done in this area so far, this article seeks to understand how credibility assessment is conducted in the practice of German courts using a quantitative approach. It will seek to ascertain whether and how the framework of credibility assessment that the qualitative research revealed is operationalized in practice. The aim of this study is to analyze the use of credibility criteria and the way that confounding factors are taken into account.

First, the study’s preparation and conduct, including its limitations will be described (I.), then the results will be presented descriptively (II.) before they are analyzed (III.).

I. Preparation and Conduct of the StudyFootnote 86

1. Purpose and Method of the Study

This quantitative analysis is meant to paint a more complete picture of the credibility assessment actually conducted in German courts.Footnote 87 Which criteria are relied on the most in practice? How does this application of reality criteria relate to evidentiary issues that are often discussed in the literature? Qualitative analyses are usually restricted to an impressionistic evaluation of quantities. Based on the analysis of a limited number of cases, it is common to postulate that certain issues come up “often,” others maybe “rarely.” While this impression need not be wrong, an empirical approach may serve to confirm such intuitions.

Additionally, this analysis may be able to inquire—to a certain extent—whether a relationship exists between the application of certain credibility criteria and confounding factors on the one hand and other properties of the cases, such as the applicant’s gender or country of origin. Due to the limited number of cases and the broader study design, such determinations are likely to be of limited reliability. But as a first study that is partly exploratory, partly descriptive, it may nonetheless show where additional research may be necessary.

In order to pursue these goals, a sample of first-instance administrative court decisions was analyzed with regard to credibility criteria, confounding factors, certain evidentiary issues and further potentially relevant properties.

First, we recorded some general properties: The court and date of the decision, the case number, the type of decision,Footnote 88 the applicant’s country of origin, gender, and the kind of persecution that was claimed.

Second, it was recorded whether the court found the applicant’s account credible or incredible, and when a court based its negative decision on the applicant’s burden of proof. It was also recorded when the court found that it was not necessary to decide on credibility because a decision could be reached without making that determination.

Third, the use of credibility criteria was recorded and categorized according to the qualitative assessment explained above: Consistency, plausibility, personal credibility, and conduct during the interview, including the type or aspect of the applicant’s conduct that was held to be relevant, e.g. emotion or aggression.

These general criteria were divided into further sub-categories: Plausibility was divided into general plausibility, the level of detail, knowledge, and the timeliness of the claim. Consistency was divided into internal, and external consistency. External consistency was further subdivided into the various means of proof that could, according to the qualitative literature, play a role in asylum cases: Country-of-origin information (COI), witnesses, medical expert opinions (commissioned by the applicant or the court), country expert opinions, data from mobile phones, reports in the media, documents (private or official), and judicial inspection (Augenschein) e.g. of photos or the applicant’s body.

Fourth, we recorded whether and how courts took into account as confounding factors: Age, gender, psychological strain, eloquence, mistakes in interview transcripts or mistakes of interpreters, cultural distance, simple error, or other confounding factors.

Fifth, it was recorded whether and to what extent the courts relied on procedural mechanisms that are particular to asylum cases: Article 4 (5) QD, which lightens the burden of proof for the applicant under certain conditions, and Section 77 (2) Asylum Act (Asylgesetz—AsylG),Footnote 89 which allows a court to dispense with a further presentation of the facts and of the reasons for its decision, provided that it follows the statements and justification of the Federal Agency.

2. Case Selection and Overview of Cases

In Germany, credibility assessment is first conducted by the executive decision-makers of the Federal Agency who decide on the asylum claim as an administrative agency. The applicant can have a negative decision reviewed by the first-instance administrative courts and ask them to issue a positive decision, Section 113 (V) of the Code of Administrative Court Procedure (Verwaltungsgerichtsordnung—VwGO).Footnote 90 These courts will conduct the credibility assessment anew. This decision by the first-instance courts will in most cases be the final one before the administrative courts, due to various restrictions on the right to appeal in German asylum law.Footnote 91

Many of these first-instance court decisions are available in official databases. Decisions of the Federal Agency are mostly not publicly available. This study will therefore focus on first-instance administrative court decisions. According to the Federal Agency, in 2017, German administrative courts took 158,726 decisions in asylum cases. Of these cases, 92.6 % (146,168) were decisions by first-instance administrative courts.Footnote 92

Due to limited resources, not all cases available in the database could be analyzed. A timeframe of three months was therefore chosen to select a manageable number of cases. The timeframe could not be designated in an entirely random manner.Footnote 93 The year 2017 was chosen because this was the first year following the “migration crisis” of 2015, in which the number of asylum cases decided by German administrative courts rose starkly and the rate at which the Federal Agency’s decisions were invalidated was the highest: More than 140,000 cases were decided in 2017 (2016: about 70,000), and 22 % of Federal Agency decisions were invalidated in 2017 (2016: 13.1 %).Footnote 94 This promised many relevant decisions that concerned credibility criteria and confounding factors. To keep the scope of this first inquiry manageable, only the months from January to March were chosen. Within the timeframe thus chosen, no further selections were made.

All first-instance administrative court decisions which had been decided in the first quarter of 2017, contained the terms “Flüchtlingseigenschaft” (refugee status) and “glaubhaft” (credible) were selected. A more accurate selection was not possible with the case properties available in the database.Footnote 95 The ambiguity of the German term “glaubhaft” was problematic for case selection. It refers not only to the credibility assessment under investigation here but also to a standard of proof.Footnote 96

The cases were downloaded from the case law database Juris. This database contains a small part of all court decisions that are actually taken.Footnote 97 According to a 2021 study by Hanjo Hamann, less than 1 % of all criminal and civil decisions by German courts are published annually.Footnote 98 But Juris is the largest case law database in Germany. It is operated by a private-law company that is majority-owned by the German state, and cooperates with the courts. There is no general obligation or practice of courts to submit all of their decisions for publication to Juris. Cases that the courts themselves do not deem “worthy of publication,” i.e. of sufficient legal interest, will usually not be included in a database.Footnote 99 For these reasons, the sample could not be representative of all decisions made.

Empirically analyzing the case law available on Juris can provide important insights nonetheless. First, Juris is used by basically all courts and practitioners. The cases available on Juris thus influence the way that practitioners see and discuss the law. Second, the study uses the data that is actually available to see and assess much more of the case law than is commonly done in legal research, and thus achieves a broader and more objective impression of that case law. While the sample could not be entirely representative, it achieves an overview that is more representative of the case law than that achieved by the common practice of using merely a handful of cases, selected from this same available case law.

This case selection yielded a pool of 291 decisions.Footnote 100 Of these 291 first-instance administrative court decisions, 55 turned out not to be relevant. In these 55 cases, the courts did not decide on the applicant’s refugee status. 236 decisions accordingly remained to be analyzed with regard to their handling of the credibility assessment.

The sample includes a wide range of countries of origin. It is not representative of the total number of asylum cases decided by first-instance courts in 2017, but the sample includes cases from all top ten countries of origin in that year, except for Albania (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Countries of Origin in the Sample.

Figure 2. Countries of origin in total in 2017.Footnote 101

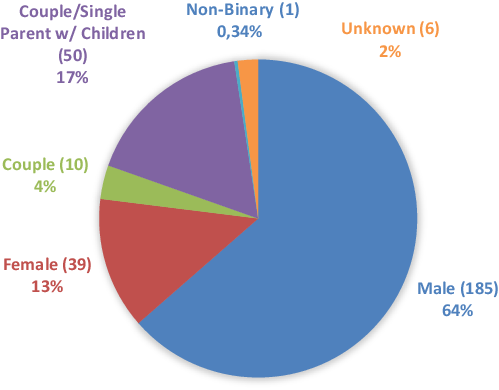

Most applicants in the sample were male (64 %). Couples or single parents with children (17%) and female applicants (13 %) were likewise represented. Only one applicant identified as non-binary, and only ten applications concerned couples without children. In six cases, no such details were available (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Applicants.

Most decisions in the sample were taken by courts in Bavaria (132) and North Rhine-Westphalia (44). But the sample also includes some decisions from all other German states except for Thuringia (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Number of cases decided on by a court in each Land.

3. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, not all the reasons that did in fact have an influence on the court’s credibility assessment must necessarily be put down in writing in the judgment.Footnote 102 As the above-mentioned research of Rehaag and Cameron showed, this might be especially true for reasons that the decision-maker knows to be legally problematic.Footnote 103

Second, a result that was arrived at by other means, for example by intuition, might be rationalized by reference to the credibility criteria ex post facto.Footnote 104 But this is true for any decision-making procedure that requires the decision-maker to give reasons.

Third, some code values, such as the date of the decision, are rather straightforward. But categorizing the credibility criteria and confounding factors, and the way they were taken into account in a decision, requires judgment. Because courts use various phrases and different wording, depending on the individual case, there was no way to avoid this. It is also the reason why an analysis using corpus linguistics could not be conducted in a sensible manner. The uncertainty introduced by this dependence on judgment, is limited though. In most cases, it is quite clear which credibility criteria the court relied on.

These limitations must be taken into account when analyzing the data and their significance. But it is submitted that valuable insights can be gleaned from the sample analyzed here nonetheless.

II. Results

1. General Overview of the Sample

In 114 of the 236 relevant decisions, the applicant’s account was considered credible (48 %). In 105 cases, the account was not considered credible (44 %). Of those 105 cases, the account was considered not credible due to the burden of proof 16 times, meaning the court was not able to convince itself of the credibility to the required degree.

In all 105 cases in which the applicant’s account was not considered credible, refugee status was denied. In 65 of the 114 cases in which the account was considered credible, refugee status was nonetheless denied for other reasons. In 52 of these 65 cases, the courts did not question the account’s credibility at all, meaning they did not apply any credibility criteria. Instead, they implicitly found the account credible for the purposes of the decision, and based their legal reasoning on these facts because refugee status had to be denied for other reasons anyway. In another 17 cases, the administrative courts explicitly refrained from deciding on the credibility of the applicant’s account because refugee status was rejected for other reasons, most frequently because the account, even if true, did not disclose a persecution ground covered by the Convention or no real risk of persecution.

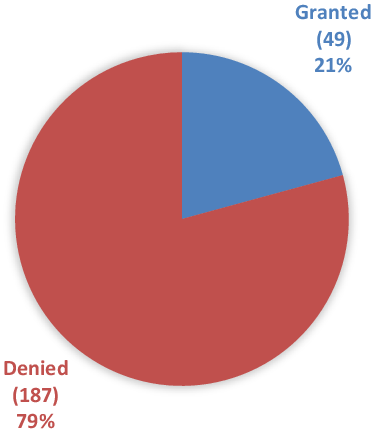

The sample’s rejection rate (79 %) is close to the refugee status rejection rate of all first-instance court decisions of 2017 with regard to the top ten countries of origin (79.9 %), and lower than the rejection rate of all countries of origin (83.8 %) (Figs. 5 and 6).Footnote 105

Figure 5. Results of Credibility Assessment.

Figure 6. Results of Refugee Status Determination.

The grounds for persecution most often argued were religion and political opinion. In most cases, no ground recognized by the Convention was explicitly argued for by the applicant (Table 1).

Table 1. Persecution Grounds

2. Use of Credibility Criteria

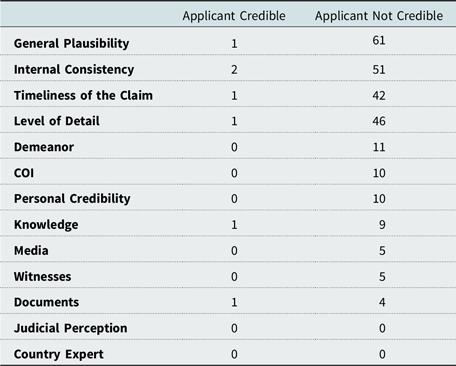

In general, the sample confirms German courts’ reliance on the credibility criteria expounded above. General plausibility, external and internal consistency, the account’s level of detail, and the timeliness of the claim play a dominant role in decision-making. Knowledge is a content-based criterion that seems to be relevant in fewer cases. In addition to these content-related credibility criteria, some courts continue to rely on applicants’ demeanor during the interview and on their personal credibility. It has to be noted that one decision can, and often will, rely on multiple criteria (Table 2).

Table 2. Credibility Criteria Used (Total)

Of the 71 instances in which external consistency was relied on, documents and country of origin information were most often relevant (Table 3).

Table 3. External Consistency in More Detail

Decisions that consider the applicant credible refer to many positive credibility criteria. Inversely, decisions that do not consider the applicant credible rarely refer to positive credibility criteria, but often to negative credibility criteria.

Most often, an account was considered credible because the courts considered it, in a general sense, plausible (16) or sufficiently detailed (14), because it was supported by documents (14) and/or country-of-origin information (14). The internal consistency of the account was likewise noted quite often (10). The applicant’s demeanor during the interview (13) and his or her personal credibility (6) could also have a positive impact. Less often, witness testimony (3), general knowledge (5), and media reports (3) were used. Additionally, the judicial inspection of photos, the applicant’s body, and the internet were considered to have no probative force—neither positively nor negatively—in 8 cases (unergiebig) (Table 4 and 5).

Table 4. Positive Credibility Criteria

Table 5. Use of Negative Reality Criteria

3. Taking into Account Confounding Factors

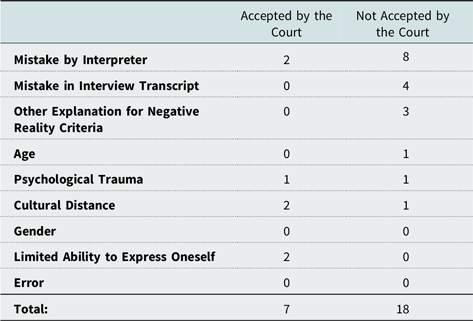

Confounding factors were comparatively rarely an issue in the sample’s decisions. Only 7 times a decision acknowledged that a confounding factor could (partly) counteract a negative credibility criterion. 18 times, the courts rejected a confounding factor that the applicant had advanced. Most often, this was a mistake by the interpreter (Table 6).

Table 6. Confounding Factors

4. Refusing to Give (further) Reasons

A tool that was used in 88 cases is the possibility under Section 77(2) Asylum Act for a court to “dispense with a further presentation of the facts and of the reasons for its decision.” A court may do so provided it “follows the statements and justification” of the Federal Agency or the parties agreed to it. In 50 of these 88 cases, no convention ground had been argued. In such cases, the courts likely relied on the original decision’s facts and reasoning to a greater extent because the result is evident. In 11 of the other 38 cases, the courts accepted applicants’ account as credible, relying on Section 77(2) Asylum Act. Finally, in all 24 cases, in which the courts found the applicant’s account not credible and relied on Section 77 (2), they did so only partially or additionally. In fact, they did rely on various reality criteria in all of these cases. The courts just agreed with the Federal Agency and stated so by relying on Section 77 (2). Because the reasons given by the Agency are mostly not reiterated in the court’s decision, no final assessment of these cases is possible.

III. Analysis

The analysis will evaluate the empirical findings. It will elaborate on their significance for a qualitative analysis of credibility assessment. Doing so, it will also point out, qualitatively, examples from the dataset that illustrate when credibility criteria seem to be applied in a sensible manner—and when they are not, in particular with regard to confounding factors.

1. Confirmation of Content-Based Credibility Criteria

This quantitative analysis confirms that content-based credibility criteria are indeed a defining feature of German jurisprudence in asylum cases. It also confirms that evidence other than the applicant’s testimony is indeed rarely available (1.1.). While inconsistencies and other criteria are important, the often-criticized plausibility criterion dominates German court practice in one form or another (1.2.).

1.1. Generally

The quantitative analysis conducted here confirms the use of the credibility criteria. All of the criteria that the qualitative analysis suggested are highly relevant in practice. Courts refrain from using them only when the case does not hinge on the account’s credibility because the result is evident for different reasons. For example, it need not be established whether the account is credible if it does not reveal any convention ground for persecution. Nevertheless, the account’s credibility is only a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the application’s success: Additionally, the real risk of persecution due to a recognized convention ground must be shown.

Practitioners and scholars generally assume that applications are most often rejected due to internal inconsistencies,Footnote 106 not only in Germany.Footnote 107 The importance of this criterion was confirmed in this study: 51 cases refer to it in a negative sense. Only general plausibility was referred to more often as a negative criterion.

As a whole, the dataset confirms that, in many cases, the decisive evidence will be the applicant’s account.Footnote 108 But external consistency was a factor in some cases, in particular documents (20) and country-of-origin information (25) was referred to. Not all sub-categories of external consistency were used often: Medical evidence, for example assessments by medical professionals, was mostly not a relevant factor in the sample. One case featured a privately commissioned (psychological) medical opinion, which was taken into account positively, and in one case a (psychological) medical opinion commissioned by the court was taken into account negatively.Footnote 109 The Istanbul Protocol, an international standard for the assessment of torture victims was not relied on in any case. This low relevance of medical evidence in the sample might be owed to the type of cases. It could be, for example, that applicants who dispose of a positive medical opinion according to the Istanbul Protocol are granted refugee status by the Federal Agency as a matter of course and thus need not have the Agency’s decision reviewed by a court.

1.2. Dominance of Plausibility

Plausibility criteria dominated the credibility assessment in the sample. The courts referred to plausibility in 203 cases, 53.7 % of all criteria.

a) General Plausibility

In the examined cases, the general plausibility of the account was the criterion most often relied on—78 times in total. The account was considered plausible in 16 cases and not plausible in 62 cases.

General plausibility is often regarded as a problematic credibility criterion because even events that seem improbable or bizarre, may have taken place just like that.Footnote 110 Four detainees who steal uniforms, weapons, a vehicle, and escape a heavily guarded internment camp might remind the reader of a movie plot. But this is exactly what Kazimierz Piechowski, Jósef Lempart, Stanisław Gustaw Jaster, and Eugeniusz Bendera did when they fled the concentration camp Auschwitz on June 20, 1942.Footnote 111

Some consider the plausibility criterion “useless” because of the subjective judgment that its application requires.Footnote 112 It is true that it tends to set the decisionmaker’s experiences as absolute.Footnote 113 Theoretically, it allows the decision-maker to speculate how the persecuted person or the persecutors would have acted in a true account.Footnote 114 Plausibility thus compares the applicant’s account to an ideal—to which reality need not conform.Footnote 115 Victims of grave human rights violations need not act in a manner that seems rational to the decision-maker in an asylum case.Footnote 116 This is true, for example, for risky conduct such as the sale of Christian utensils in Afghanistan under the Taliban or a kiss between two men in public where such conduct might incur criminal responsibility.Footnote 117

Why then, despite these limitations, is the criterion so regularly used in German court practice? The fact that this criterion was used the most in the sample could to some extent be owed to the design the of the study: General plausibility served as somewhat of a catch-all criterion for probability judgments that did not fit one of the more specific categories. But there is also another explanation: Plausibility is reminiscent of, and in certain cases consists of, the use of circumstantial evidence. Circumstantial evidence points to a known fact in order to make the existence of another fact more likely, but without making the existence of this other fact a necessity.Footnote 118 The German Federal Constitutional Court has confirmed that circumstantial evidence may be used in asylum cases as well.Footnote 119

Consider, for example, the case already mentioned above, in which the applicant claimed that he had wrested himself from a guard, left his clothes in the guard’s hand, then evaded another five of them by vaulting a two-meter wall. These facts beg the question how this was possible:

It takes time to wrest oneself away from a guard so vigorously that clothes are left in his hand and to scale a two-metre wall—yet none of the six soldiers outside intervened to prevent it or to shout for assistance even just from those already outside the house. It was for the Appellant to give such evidence of the disposition of the soldiers, and of the layout of the house, exterior grounds, wall and entrance that might explain how it all might have happened.Footnote 120

While general plausibility has its place in credibility assessment, it is indeed prone to abuse and error. It should be applied restrictively. In order to minimize plausibility’s tendency to invite speculation and prejudice, its application must be based on reliable country-of-origin information.Footnote 121

b) Timeliness

The claim’s timeliness—and the account’s level of detail and the applicant’s knowledge about certain issues—are specific emanations of the plausibility criterion. Yet, they seem less problematic to many commentators. In a way they are, because their premise, the connection between the fact that is used as circumstantial evidence and the fact that should be proven by it, seem better established. Nonetheless, their application requires great care.

The timeliness of a claim becomes relevant when more acts of persecution or acts of persecution of a qualitatively more serious nature are added to the original account in the course of the administrative procedure or in court. A later submission of persecution-relevant facts requires explanation. The courts referred to the timeliness of the claim 47 times in total. In 43 of those cases, the criterion was deemed negative, meaning that the applicants could not sufficiently explain why they did not present these facts earlier in the proceedings.

In 4 cases, still, the court was convinced by the applicant’s explanation. For example, the credibility of an account was not called into question by the fact that the applicant did not mention his activity in the Kurdish regional parliament during his interview at the Federal Agency. The applicant pointed to communication difficulties with the interpreter and that the interpreter had asked him to keep his statements as brief as possible. He also explained that at the time of his hearing, the Federal Office consistently granted refugee status to refugees from Syria. Therefore, he had not insisted on telling his whole story.Footnote 122 In the other cases, the applicant convincingly explained a later claim by pointing out that the Federal Agency had not asked about an issue (religion),Footnote 123 that the event in question had not happened yet (a Christening),Footnote 124 and that he had assumed that a pattern of persecution (against relatives of defected officers in Syria) was commonly known in the Federal Agency.Footnote 125 It is thus crucial for courts to ask the applicant why a claim is brought forward late.Footnote 126 As the examined cases show, it may well be explainable.

c) General Knowledge

The context-independent general knowledge of the applicant is a credibility criterion if such knowledge can plausibly be expected. This is particularly the case in the assessment of the seriousness of religious conviction and also origin. Such general knowledge was referred to 16 times. In 6 cases, the knowledge of the applicant was deemed positive and in 10 cases the lack of knowledge was deemed negative. For example, one applicant claimed to be part of the ethnic group of Tigrayans in Eritrea, but he did not speak their language, Tigrinya.Footnote 127 In another case, an applicant’s religious conversion was considered not credible, despite sufficient knowledge about the Christian religion, just because the court thought the applicant was abusing the asylum system as it held many other Iranian asylum seekers to do.Footnote 128

d) Level of Detail

The court referred to the level of detail of the applicants’ account in 62 cases. In 16 cases, the court positively considered the level of detail and in 47 cases it negatively considered a lack of detail. For example, in one case the applicant could not specify the threats he was said to have received even after he was explicitly asked to do so: “His statements about the threats remained brief, abstract, general, colorless, and superficial. They did not appear to the court to be a description of what he had actually experienced.” The court noticed how he was able to describe other situations in more detail.Footnote 129

2. Continued Use of Discredited Conduct-Based Criteria

Some German administrative courts still rely on conduct-based credibility criteria, such as the applicant’s demeanor and personal credibility; even though, such criteria have long been discredited in the relevant scientific literature. They should be abandoned entirely.

Personal credibility was in total relied on in 16 cases. But in 6 of the 24 cases in which demeanor was used, personal credibility was assessed as well. So, a decision-maker who relies on demeanor seems more likely to also rely on personal credibility, and vice versa.

This use of demeanor and personal credibility is not confined to individual judges, courts or states. The 24 cases in which demeanor was used stem from 15 different administrative courts in different states. It was used in cases with male, female, and non-binary applicants as well as when couples with children applied for refugee status. The countries of origin concerned were varied and from different continents: Afghanistan, Iran, and Syria, but also Kosovo, Eritrea, and Sri Lanka. While these conduct-based criteria are not (explicitly) used as often as the content-based criteria, they still influenced the courts in the dataset in a considerable number of cases.

2.1. Demeanor

Demeanor was considered 24 times: As a positive factor in 13 cases, and as a negative one in 11. In 16 of these 24 cases, the court referred to the general impression made by the applicant during the interview. In the other cases, emotion (4), aggression (1), and the manner of speech (3) were taken into account.

For example, in one case the applicant’s gestures and facial expression were taken into account negatively because he did not react in the way the court expected when he was shown a photo that was supposed to depict his dead relatives: “Appropriate emotions or dismay could neither be seen in the claimant‘s gestures nor in his facial expression—even after the court told him that these are terrible photos and that the court deplored what could be seen on these photos, if they showed his relatives.”Footnote 130 In another case, it was taken into account positively that “[a]s a whole, the claimant made a calm and collected impression. He did not seem to just rehearse knowledge that he had learned by heart. To the various questions [on the Christian faith] he replied equally convincing, without seeking to evoke a certain impression in the court.”Footnote 131

Researchers have tried to find “cues” in a person’s demeanor that indicate a lie for a long time. These attempts have failed. According to the relevant experiments, laypersons using demeanor as an indicator only recognize the truth of a statement with a probability that corresponds to chance. The tossing of a coin would, with equal certainty, distinguish the truth from a lie—regardless of how well one knows the person.Footnote 132 This is widely accepted in the relevant scientific community that conducts empirical studies in this area.Footnote 133 Some even consider the search for “cues” in people’s demeanor to be “pseudoscience”:Footnote 134 “Lively debates about the merits of nonverbal lie detection no longer take place at the scientific conferences that we attend. Yet nonverbal lie detection remains highly popular among practitioners.”Footnote 135

The main reason why demeanor is no useful indicator seems to be that one’s demeanor during an interview is too individual and can have many different causes.Footnote 136 The formality of the situation can make people insecure and nervous,Footnote 137 in particular if they are vulnerable.Footnote 138 Others may be able to speak more freely and without inhibitions—which may in turn seem suspicious.Footnote 139 Certain “cues” for lying that may seem common sense to laypersons and some decisionmakers, as avoiding eye contact, fidgeting and swallowing due to a dry mouth, have proven to be unreliable as well.Footnote 140 Despite many empirical studies, no connection could be established between such demeanor and lies.Footnote 141 Sometimes studies even lead to contradictory results: Someone who is lying may try to avoid demeanor that is often thought of as a cue, for example the person may keep more eye contact than usual. Someone who is not lying also has an interest in being perceived as honest and credible. Footnote 142 In particular when it comes to sexual offences the expectation that victims behave in some “typical” fashion has time and again lead to grave mistakes because the one specific demeanor that indicates truthfulness or subterfuge simply does not exist.Footnote 143

This can also be seen in the case that was recounted above: The judge assumed that there is a specific way in which one has to react to pictures of one’s dead relatives. The problem with this is not only that there is no one reaction that a person must have in this situation. Even if the “correct” reaction was had, it might still be taken by the decisionmaker to be too emotional or “manipulative,” or as the judge in the above-mentioned case put it “seeking to evoke a certain impression in the court.” Applicants would thus have to show a certain performance that is neither too unemotional but also not too “over the top,” according to the standards of the decision-maker, so that they behave in a way that is perceived as “credible.”

This malpractice can also be observed in cases concerning homosexual applicants. On the one hand, the court may expect a stereotypical appearance and demeanor. On the other hand, the court may consider such appearance and demeanor artificial. For example, in one case the court noted positively that the applicant did not try to appear as stereotypically homosexual.Footnote 144

Expecting such performances evidently does not serve the purpose of credibility determination. To the contrary, as the British judge Thomas Bingham stated long ago: “To rely on demeanour is in most cases to attach importance to deviations from a norm when there is in truth no norm.”Footnote 145 For asylum cases, in which cultural distance between the decision-maker and the applicant exists, and language interpretation is most often necessary, this is all the more true.

Why then is demeanor still used? A major reason seems to be a lack of interdisciplinary work. The results of psychological research in this area simply have not been taken into account adequately in legal literature and practice. As the law stands, demeanor may be taken into account as a credibility criterion. Courts and legislators accept it.Footnote 146

The law and the court practice must be changed to reflect the insight that demeanor is an invalid criterion that cannot be used to divide credible from incredible accounts. The Federal Agency and administrative courts must not rely on it anymore.

2.2. Personal Credibility

The idea that certain “types” of witnesses exist, that their station in society or their morals are relevant for assessing the credibility of their account is old.Footnote 147 Most commentators reject the idea now.Footnote 148 Yet, the idea that, for other reasons, the applicant in an asylum case could be considered personally credible or incredible, survives till this day in German court practice, even though the threshold for considering an applicant personally incredible is held to be high.Footnote 149

In 16 cases, the court referred to the personal credibility of the applicant. In 10 of these cases, the court deemed the claimant not credible, whereas in 6 cases the person was held to be credible. The court mostly just postulated the personal credibility without giving an explanation. If reasons were given, personal credibility was determined based on the content-based criteria.

As intuitive as this criterion of personal or general credibility of a person may seem,Footnote 150 it does not have analytical value beyond what can already be taken into account through the content-based criteria. Even worse, it provokes mistakes. This is most obviously true for stereotypical prejudice that seeks to draw conclusions from a person’s looks or “type.”Footnote 151 In particular in asylum claims, personal credibility is extremely prone to reflect such prejudice.Footnote 152

Some people may indeed be more likely than others to say the truth in a certain situation. But no one is constitutively credible or incredible.Footnote 153 Extrapolating from a person’s personal credibility to the credibility of his or her specific account is always a mistake.Footnote 154 Even a person that has been caught in a lie is not per se incredible. One lie does not render the entire account incredible.Footnote 155 This is generally accepted by national agencies and courts,Footnote 156 and also by the UNHCR.Footnote 157 Someone who is truthful regarding the core of the account might still lie in other areas, e.g., to meet presumed expectations of the interviewer, out of shame, or in order to unnecessarily improve their position in the asylum proceedings.Footnote 158

Lies can be taken into account as inconsistencies in the content-based assessment of the account’s credibility. But their significance must be weighed in the individual case, taking into account confounding factors.Footnote 159 A category of personal credibility that focuses on the person of the applicant is superfluous in so far as it relates to aspects that can be taken into account with content-based criteria. Beyond that it is prone to mistakes and abuse. It should therefore be rejected as a criterion of credibility assessment de lege ferenda.Footnote 160

3. Correlation of Credibility Criteria and Credibility

The assessment of some credibility criteria as positive or negative correlates strongly with the court’s conviction concerning the applicant’s credibility. First, as already mentioned, in all cases the positive or negative assessment of conduct-based criteria corresponds to the court’s conviction. Second, the number of cases in which the plausibility criteria were deemed positive is almost the same as the number of cases in which the court considered the applicant credible and vice versa. This could suggest two things: That a result that was arrived at by other means, such as simple prejudice, was rationalized by reference to these criteria ex post facto. Or these criteria were used to overcome remaining doubts in one or the other direction.

4. Insufficient Awareness of Confounding Factors and the Duty to Confront

Negative credibility criteria indicate an incredible account only in a prima facie manner. The account may display negative credibility criteria despite being truthful. There might be other explanations for contradictions and implausibilities. It is therefore always necessary to consider the possibility that the applicant’s account exhibits negative credibility criteria only due to confounding factors.Footnote 161 Such factors were insufficiently taken into account in the court practice reflected in the dataset. While this study of course could not reveal whether confounding factors were accurately accepted or rejected, it stands to reason that the possibility of confounding factors should have been at least considered in many more than the 25 cases that did so.

Legally, courts have a duty to confront applicants with negative credibility criteria, in order to rule out that they are based on confounding factors. In one case, the court noted the applicant’s claim that the interpreter in the administrative procedure did not properly speak the applicant’s language, but ultimately the court simply ignored it. Footnote 162 Confounding factors must be considered by decision-makers not only when applicant or counsel argue for it. They must be considered proprio motu whenever there is sufficient reason do so:Footnote 163 Article 4 (1) QD requires EU Member States to cooperate with applicants to assess the relevant elements of the application:

[If] for any reason whatsoever, the elements provided by an applicant for international protection are not complete, up to date or relevant, it is necessary for the Member State concerned to cooperate actively with the applicant, at that stage of the procedure, so that all the elements needed to substantiate the application may be assembled.Footnote 164

According to Article 16 Asylum Procedures Directive (APD),Footnote 165 the applicant must not only be “given an adequate opportunity to present elements needed to substantiate the application” but also “the opportunity to give an explanation regarding elements which may be missing and/or any inconsistencies or contradictions in the applicant’s statements.” So, for example, an application may be rejected for a lack of details only if the applicant was asked for them.Footnote 166 For evident contradictions, the significance of which could not possibly escape the applicant, an exception might be accepted.

Yet, confounding factors were rather rarely taken into account in the sample. Of all 239 cases, only 7 times the existence of a confounding factor was acknowledged. 18 times, the courts rejected the possibility that a confounding factor could have had an influence. It stands to reason that the courts should have considered the possibility of confounding factors in many more cases. Decision-makers apparently do not take their duty to confront the applicant with negative credibility criteria, emanating from Article 4 (1) QD and Article 16 APD,Footnote 167 sufficiently seriously. They need to consider confounding factors, if there is any reason to do so. They must point out negative credibility criteria to allow for confounding factors to become apparent.

The cases in which the courts did consider confounding factors show how important it is to do so. But these cases also show that considering confounding factors need not unduly complicate matters by giving someone caught in a lie an additional line of defense, for example the opportunity to advance potentially far-fetched, self-serving justifications. Such justifications—or “(self-)protective assertions,” Schutzbehauptungen—can of course be rejected, according to the same credibility assessment.

For example, in one case, the applicant argued that he did not disclose earlier that his brother was actively opposing the Syrian regime because he was afraid that the information would be relayed to his home country’s authorities by the Federal Agency. The court acknowledged that he may have been excited and even confused during his interview with the Agency. But the court considered the applicant’s justification “absurd” that he had not revealed this information because he thought that the Federal Agency had connections to the Syrian regime and might harm his family. The court pointed to the interview’s protocol which stated that he had been asked repeatedly to disclose any reason why he would be in danger upon his return.Footnote 168 This qualification as “absurd” is acceptable only if it is taken to mean that the applicant could not have possibly believed that. After all, for its qualification as a confounding factor, it would be irrelevant whether the applicant’s honestly held suspicion would be “absurd” or not. But this reaction of the court also shows a certain tendency to dismiss confounding factors maybe too easily. They should be rejected only after careful consideration.

A good example of how confounding factors should be considered is the following case from the sample. The Afghan applicant argued that he had been attacked by the Taliban. A lack of internal consistency and a low level of detail weighed against his account’s credibility. In the interview at the Federal Agency, he had said that he had been stopped twice by the Taliban. He had been threatened the first time and hurt with a knife the second time. Before the court he later mentioned—even when specifically asked—only one incident and ultimately, reconsidering during the interview, no knife attack. He also made different statements on whether he was alone and if the Taliban were on motorbikes or standing on the street. His account lacked detail. He could not explain why he had stopped at all. Even when told that the court needed details, he only said that he “had been hit” by the Taliban. When asked by his legal counsel, he could not substantiate his account, and merely chose from options that his counsel proposed to him through his questions. The applicant drew a sketch of the situation only more or less against his will and with a lot of help by his counsel. The applicant was more detailed when describing the weapons, but the description did not connect to the specific incident and the court assumed that he had seen such weaponry on other occasions.Footnote 169

Finally, and importantly, the court considered whether this inconsistent account that lacked detail was owed to the “personality” of the applicant, for example, how he generally speaks of the things he has experienced. But this possibility was rejected because the applicant was able to speak in detail and vividly about situations that he had experienced: About his work at a bank and also how he went to the market twice a week. The court noted how his legal counsel even had to stop him from continuing on about these things. Because of the inconsistency and the lack of detail of the account relating to his alleged persecution, the court considered the account not credible.Footnote 170 This case is a good example of how credibility assessment should be conducted: Carefully weighing the different credibility criteria and inquiring into confounding factors.

5. Bias

Female applicants and couples with children were somewhat more likely to be believed than men. But the small sample size—all the more for couples and non-binary applicants—and the applicants’ different countries of origin, which have different acceptance rates, make it impossible to know if this is significant. A future study would need a larger sample size and would need to focus on specific countries of origin and time frames, maybe even specific persecution grounds, so as to make the circumstances of the cases as comparable as possible.

It could also be considered to look for racist bias according to the different countries of origin, which may indicate—to a certain degree—how applicants would be perceived or “racialized” by decision-makers. It seems difficult, however, to compare the different countries of origin in this regard. Many statistical confounding factors come into play, inter alia, the different circumstances in the countries of origin, different grounds for persecution, etc. (Table 7).

Table 7. Bias

6. Insignificance of the Standard and Burden of Proof and of Article 4 (5) QD in Practice

Two issues that are often and intensely discussed in the literature did not have any significance in the sample: The standard and burden of proof, and Article 4 (5) QD. In 16 cases, courts formally relied on the burden of proof to reject the application, meaning the court was not able to convince itself of the credibility to the required degree, but was also not convinced that the applicant was not credible. But these 16 cases all concern so-called safe countries of origin. These are countries of origin that the German Parliament has designated as generally safe according to Article 16 (3) of the Basic Law. According to Section 29a (2) Asylum Act, in these cases, applicants have the burden to show that they are individually persecuted despite the presumption against persecution based on the generally safe situation in this country. In all other cases, the courts never relied on the burden of proof and the fact that the applicant had failed to meet the standard of proof. Rather, the courts either held the applicant’s account to be credible or explicitly rejected the account’s credibility.

Article 4 (5) QD is much discussed in literature as a crucial albeit flawed evidentiary rule:Footnote 171 When it is the applicant’s duty to substantiate the application, certain aspects of the applicant’s statements shall not need confirmation even if they are not supported by documentary or other evidence. But this rule played no role whatsoever in any of the 236 cases. The reason for this lies in the jurisprudence of the German Federal Administrative Court which unconditionally grants what Article 4 (5) QD promises only in case five criteria have been complied with. While the German courts need to be “fully convinced” of the existence of the relevant facts according to Section 108 (1) VwGO (volle Überzeugungsgewissheit), they cannot require something impossible from applicants. Because asylum seekers will typically lack evidence to corroborate their accounts (sachtypische Beweisnot), the Federal Administrative Court holds that an applicant’s account must suffice to convince the court if it is credible. Thus, German courts must not reject a claim because the applicant’s account was not backed by further evidence anyway,Footnote 172 and Article 4 (5) QD serves no purposes in this context.

7. Significance of Procedural Safeguards

The data seems to indicate the necessity to provide applicants with legal counsel and to make more use of the limited possibility to appeal court decisions.

7.1. Legal Counsel

The available data, unfortunately, do not reveal if the applicants were represented by counsel. But there is one observation that makes it likely that many of them were not. In 97 cases, no convention ground of persecution was argued, and refugee status rejected. Despite the fact, that the application could have been rejected on that account alone, in 43 of those cases the applicant’s account was considered credible, and in 44 cases not credible. In only 10 of these cases, the courts did not find it necessary to decide on credibility. The reason for this may be that often the courts will try to base their decision on as many grounds as possible so as to be sure that the result is correct and also to insulate it from appeal. But unlike in other areas of law, the possibility of an appeal will usually not be a prominent aspect in lower courts’ thinking: Appeals in asylum cases are severely restricted in Germany.Footnote 173

The fact that in 97 of all 236 cases the applicants did not argue a convention ground but claimed refugee status nonetheless seems to indicate a lack of legal counselling. While it is possible that in some cases, there may be legal uncertainty if persecution is based on a convention ground, in most cases it will be quite clear if someone argues that they are persecuted for political, religious, or other reasons covered by the Geneva Convention. It can be assumed that legal counsel would not recommend claiming refugee status without indicating a recognized convention ground for persecution. A possible alternative explanation would be that the applicants were simply being honest—even if that meant that their application would certainly be rejected.

7.2. Appeal

In only 5 out of all 236 cases, a judgment was rendered on appeal.Footnote 174 All of those appeals were dismissed by the higher administrative courts, once by the Federal Administrative Court.Footnote 175 In 4 cases, the credibility assessment of the lower administrative court was not dealt with on appeal.Footnote 176 In one case, the appellant claimed a denial of the right to be heard due to a so-called surprise decision (Überraschungsentscheidung), but not with regard to the credibility assessment. The higher administrative court nonetheless stated, that ”it is self-evident that the person’s credibility and the account’s credibility are always at stake in asylum proceedings, insofar as they are relevant to the decision.“Footnote 177

It was to be expected that the number of judgments reviewed in an appeal procedure would be small, because access to judicial remedies beyond the first instance has been severely restricted in German asylum law. Thus, errors that occur in the first instance credibility assessment can only be checked and—if necessary—corrected to a very limited extent. So, the final decision about a person’s and their account’s credibility often lies in the hands of first-instance individual judges.

Yet, some judgments show the need for a review by a higher administrative court. For example, in one case, the court was not convinced that the applicant had genuinely converted to Christianity because the applicant had not sufficiently reflected on the rape for which he had been convicted and had not apologized to the victim.Footnote 178 The court thus disregarded the generally accepted credibility criteria for ascertaining whether someone genuinely converted to a new religion. Instead, the court assessed the applicant’s credibility based on what the court considers to be proper conduct for a “good Christian.” Of course, this is not relevant in any way for assessing the applicant’s credibility. This judgment was in dire need to be reviewed for arbitrariness. While an appeal would not have been possible, an arbitrary credibility assessment can be challenged with a complaint to the Federal Constitutional CourtFootnote 179 and, if need be, to the European Court of Human RightsFootnote 180 .

E. Concluding Observations on the Limits of Objectivity in Decision-Makers and Algorithms

The Oxford Handbook of Refugee Law of 2021 came to the conclusion that: “Evidential assessment in the asylum procedure is dysfunctional.”Footnote 181 The study conducted here confirms that substantial problems persist. But it also shows how German courts try to assess applicants’ credibility in a manner that is as rational and objective as possible. The aim should be to further standardize, refine, and rationalize the procedure to safeguard it against errors and abuse. The most important step in this regard would be to abolish any reliance on conduct-based criteria.

As any balancing exercise, the application of credibility criteria and confounding factors requires judgment. This judgment is necessarily subjective, which makes it important who takes the decision.Footnote 182 Some consider this character of credibility assessment to be incompatible with the rule of law: “In the asylum field, it is not law that rules, but individual decision-makers.”Footnote 183 The criteria are said to be merely a “door-opener” for subjective discretion. But the same critique would be true for any credibility assessment that is not entirely mechanic. In human rights law, for example, the balancing required by the proportionality analysis is likewise often criticized as highly subjective. Nonetheless, it is an important part of that law.

Credibility assessment is a highly complex task. No reasonable method of credibility assessment that sufficiently takes into account this complexity could eliminate the necessity for epistemic judgment and thus subjectivity. Subjectivity should not be equated with arbitrariness though. It cannot be a requirement of the rule of law that all decision-makers would in any one case come to the exact same conclusion. This asks something of legal decision-making that no system anywhere has ever or could ever achieve.