I

When Korean envoys once again began visiting Japan in 1604 following the rupture that had occurred with Toyotomi Hideyoshi's invasions of the Korean peninsula (1592–8), diplomacy was conducted as it had been for centuries, via interpreters and through what is often described as the lingua franca of the region: written classical Chinese, a system of logographic signs and syntax mutually intelligible to elites who shared no common tongue but who had been educated according to centuries-old tradition in the same canon of literary, religious, and philosophical texts originating in China. Thanks to this tradition, the situation arose in which a Korean and a Japanese scholar – or indeed scholars from any two East Asian states – could read the one Chinese document, each in his own language, without either knowing a word of spoken Chinese. As well as providing the medium in which official diplomatic documents were written, in face-to-face encounters the classical Chinese writing system was used for communication, written with a calligraphy brush and hence sometimes called ‘brush talk’, which provided an alternative to oral interpretation. Early examples of brush talk date from poetic exchanges in the eighth to tenth centuries,Footnote 1 and the practice continued until well into the nineteenth.Footnote 2 The contents of many brushed encounters, including conversations, question and answer dialogues, and exchanges of Chinese poetry, were carefully preserved. Yet there has been little work on the topic of brush talk and fundamental questions about the practicalities of brushed communication prior to the late nineteenth century remain unanswered.Footnote 3 In addition, the study of early modern diplomatic history has in recent decades expanded beyond a bureaucratic, state-centric focus to consider the processes and personal interactions by which international relations were maintained, of which brush talk is a prime example.Footnote 4 Since the term ‘early modern’ originates in European historiography, it is not without its problems when applied to non-European histories. However, in the Japanese case it is generally accepted that the seventeenth through to the mid-nineteenth centuries, when Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa household (the Tokugawa period, 1600–1868), may be described as early modern in a comparative sense due to characteristics such as urbanization, the emergence of a strong state, and the penetration of a market economy.Footnote 5 As an example of non-state actors in early modern diplomatic history, this article focuses on the well-documented encounters between embassies from Chosŏn Korea and their Japanese hosts during the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, and addresses the following questions. Precisely when and why was brush talk used during these diplomatic encounters, and by whom? What was the division of labour between brush talk and oral interpretation? How should we understand the place of brush talk among the various practices that formed part of diplomatic encounters in East Asia?

Beginning most famously with Sheldon Pollock, who contrasted the spread of Sanskrit with the history of Latin, historians have begun to examine the role of lingua francas other than Latin.Footnote 6 East Asian history circles are no exception and have seen a recent interest in how concepts such as ‘lingua franca’ and ‘diglossia’ apply to the role of classical Chinese and local vernaculars in the intertwined histories of China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam.Footnote 7 As a visual medium that obscured cultural difference by giving the appearance of a common language in the absence of a shared tongue, classical Chinese brush talk challenges received notions about the concept of a lingua franca, and the way translation may operate in diplomatic contexts.

II

Brush talk was a product of the sphere of Chinese textual influence. In pre-modern times, a written culture derived from China was shared by elites from the Khitan, Tangut, and Jurchen civilizations in the north of modern day China, as far south as what is now the northern part of Vietnam, and was particularly significant for states in the regions now known as China, Vietnam, Korea, and Japan.Footnote 8 Confucian texts, works of historiography, poetry, and law, as well as translations of the Buddhist sutras, travelled from China in the possession of monks, court officials, and literate migrants. The textual balance of trade was not entirely one way, but Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese legal systems, elite education, literary forms, and even urban design were shaped along authoritative Chinese lines with local modifications.

The term ‘Sinosphere’ has been coined to describe regions within the range of Chinese cultural influence, particularly where such influence involved the use of the Chinese writing system, which is known in English as ‘classical Chinese’, ‘literary Chinese’, and ‘Sinitic’.Footnote 9 In East Asia, writing was a technology originating in China as Korea, Japan, and Vietnam did not possess a written language before the arrival of Chinese works. The earliest written texts composed in these regions used the Chinese writing system, and date from after the importation of Chinese literacy from the early to mid-first millennium. The ability to read and write in the Chinese style remained an important skill for elites long after the ability to speak Chinese became rarer, and continued even after the development of local scripts.Footnote 10 In the absence of widespread spoken Chinese ability, the situation developed wherein many non-Chinese authors and readers who used the classical writing system in fact had no knowledge of Chinese morphology or pronunciation. When they wrote ‘Chinese’, they were encoding their own languages logographically using Chinese graphs and the conventions of classical Chinese syntax, and as readers they were decoding these graphs and conventions in order to produce a reading in their own language. This article, therefore, will use the term ‘Sinitic’ as an alternative to ‘classical’ or ‘literary Chinese’ to describe the Chinese writing system as it was used in early modern East Asia more broadly than just in China.Footnote 11

The widespread importance of Sinitic in East Asia was reflected by its use in diplomatic encounters. Diplomacy was not established in Japan as a separate governmental skill to be practised by professionals until the nineteenth century, and in pre-modern times fell to Zen monks of the officially recognized Gozan temple institutions, who maintained contact with the Chinese continent, and to Japanese literati with skills in Sinitic.

This predominance of Sinitic in diplomacy continued until the late nineteenth century when Japanese officials sought to wrest the language of diplomacy from what they saw as Chinese control by redefining the meaning of Sinitic legal terms according to the norms of European international law, eventually switching to English in negotiations.Footnote 12 As Alexis Dudden has detailed, even before the Japanese annexation of Korea in 1910, Japanese leaders during the Meiji period (1868–1912) were determined to show, via the correct use of Western legal terminology, that their nation had embarked on a legal and legislating mission vis-à-vis Korea. The switch away from Sinitic terms heralded an epistemic change in which the legitimizing language of power in East Asia was no longer Chinese but Western.Footnote 13

Until these upheavals in the nineteenth century, however, the norms of international behaviour in East Asia were couched in Sinitic terms and existed within a loosely conceived Sinocentric world order premised on a dichotomy between ‘civilized’ and ‘barbarian’ states. Civilization, consisting of the ethical norms of Confucianism, was embodied in the Chinese state, which was in turn personified by the Chinese emperor. Non-Chinese monarchs were permitted to participate in this order on condition that they acknowledged themselves to be subjects of the Chinese emperor and received investiture as monarch of their countries.Footnote 14 Participation in this Sinocentric system was an acknowledgement of cultural, not political, power: vassal states were largely free to conduct their domestic affairs as they pleased so long as they recognized China's place at the top of the cultural hierarchy.Footnote 15

East Asian states varied in their response to the conceit of Chinese centrality. The Korean Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1910) took pride in being ranked first among the Ming (1368–1644) hierarchy of tributary states and remained ‘the loyal domain par excellence’ under the Qing (1644–1912).Footnote 16 Likewise, throughout the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, the Vietnamese kingdoms of Lê (1428–1788), Tây Sơn (1770–1802), and Nguyễn (1802–1945) regularly dispatched tribute embassies to the Chinese capital.Footnote 17 Japanese relations with China, however, were varied. In the fifteenth century, the Ashikaga military rulers (shoguns) of Japan actively participated in the tribute system in order to obtain the right to trade with China, but these rights lapsed in 1547. By the seventeenth century, the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868) was reluctant to accept a status subordinate to China, particularly after the fall of the Ming dynasty to Manchu ‘barbarians’ in 1644. The Tokugawa allowed private trade with China through the port of Nagasaki and by proxy through the Ryukyu kingdom (modern-day Okinawa), which was simultaneously both a vassal of the southern Japanese domain of Satsuma and of Qing China. However, the shogunate did not send tribute missions to China, which would have been the price for permission to trade officially with the Qing dynasty, and were careful to refer to the shogun in international correspondence using terminology that emphasized Japanese parity with China.Footnote 18 In an attempt to assert its authority, the shogunate also encouraged visits from Korean and Ryukyuan embassies, publicly shaping these occasions so as to give the appearance of Japan as the superior power accepting tribute from subsidiary vassals. In reality, the Ryukyuan king paid tribute to both Japan and China but the Chosŏn dynasty acknowledged the suzerainty of China alone. In practice, these states had limited control over the ways in which the Tokugawa regime symbolically used their presence in Japan so as to give the appearance of a subordinate, tribute mission.Footnote 19

III

There were twelve occasions when representatives from the Chosŏn court visited Japan during the Tokugawa period.Footnote 20 The initial purpose had been to normalize relations, which had been ruptured at the end of the sixteenth century by a seven-year war with Korea and China that had been waged by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–98), who was then pre-eminent among Japan's daimyo (or feudal lords).Footnote 21 Prior to Hideyoshi's invasions, Japanese relations with Korea had involved a long-standing exchange of embassies and trade, primarily conducted through daimyo in Western Japan. After 1551, when the Ōuchi clan was destroyed, the role was left to the Sō family from the island of Tsushima located in the strait between Korea and the Japanese island of Kyushu. The Chosŏn state preferred to deal with Japan via the Sō family, and Tsushima was permitted to maintain a trading house in the Korean city of Pusan, the Waegwan (Japan House).Footnote 22

The island of Tsushima was thus the point of first landfall on Japanese soil for the Chosŏn ambassadors and their retinues of up to 500 or more, after which, escorted by hundreds, even thousands of samurai they made their way to the shogunal seat of Edo in what is modern day Tokyo. The visits were minutely choreographed spectacles, which attracted the attention of hundreds of thousands of onlookers, and became a major trope in Japanese art of the eighteenth century.Footnote 23 As the embassies worked their way north-east and back again over a period of several months, each rest point presented an opportunity for interaction with their hosts and scores of eager locals. In the absence of a common spoken language, such interactions took place through interpreters, or via Sinitic brush talk. Extensive written and painted records of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Japanese encounters with Korean embassies survive and this article considers a selection for the light they shed on some fundamental questions that are yet to be answered on the theory of brush talk and the ways it operated in practice.Footnote 24

IV

The term ‘brush talk’Footnote 25 is in fact one of several used to describe different types of face-to-face written communication during the East Asian pre- and early modern periods, and typically refers to a written prose conversation between one or more individuals. A similar but more formulaic style of exchange, the question and answer dialogue,Footnote 26 a common teaching method, was also conducted by means of the brush during encounters between individuals from different East Asian states. During the Korean embassies to Japan, both forms of brush communication provided the opportunity for local literari, medics, and interested members of the warrior estate to quiz visitors on matters pertaining to their home country, to exchange ideas about Buddhism or Confucianism, or to seek information about the latest developments in medicine and pharmacology. For example, brush talk with Korean doctors, who travelled to Edo in the entourage of Chosŏn embassies, was a rare opportunity for Japanese physicians to discuss medical topics with doctors from outside Japan, rather than having to rely on imported books.Footnote 27

The other important type of brushed communication was called ‘chanting in harmony’Footnote 28 and described a written exchange of Chinese poems. Chinese-style poetry had originally been a means of socializing among intellectuals in China, and spread to other parts of the Chinese cultural sphere. Since diplomacy was conducted by literati, monks, and classically educated court officials, poetry became an important part of diplomatic exchanges and remained so well into the early modern period. Envoys recorded their impressions by composing Chinese poetry at various points on their journey and usually exchanged written Sinitic poems with representatives of the country they were visiting.Footnote 29 Although Chinese-style poetry was fundamentally an oral medium to be intoned or chanted, and Japanese and Chinese diplomats wrote their compositions according to the rules of Chinese ryhme and tonal prosody, such characteristics were only apparent in the written Sinitic version: if intoned according to their respective reading traditions, the two readings would have been mutually incomprehensible, and much of the rhyme would have been lost.

As Douglas Howland has detailed, the practice of brush talk, in the form of Sinitic poetic exchanges, featured in East Asian diplomatic encounters until well into the nineteenth century.Footnote 30 Examples include the famed Chinese poet Huang Zunxian (1848–1905) who served from 1877 to 1882 as secretary to the Qing legation in Tokyo, during which time he often composed Sinitic poetry in the company of Japanese literati, contributing to the modern Japanese canon of Chinese poetry (kanshi).Footnote 31 And in 1885 at a banquet given for another Chinese scholar-diplomat, Yao Wendong (1852–1927), who was temporarily returning to China for family reasons, Japanese literati composed forty-one Sinitic poems for Yao, which were later published in China.Footnote 32 Neither of these men spoke Japanese and few of the Japanese intellectuals with whom they associated had any knowledge of modern Chinese. Howland has noted that at the personal level of friendly relations between scholars and officials from Japan and China, such exchanges served to include Japan within the sphere of Chinese civilization, emphasizing the shared cultural heritage of the two nations and smoothing relations. As we will see, this potential for emphasizing common cultural and intellectual ground was one which had been exploited throughout the history of brush talk in East Asia.

V

Dealing as they did with highly specialized topics in religion, philosophy, litererature, and medicine, early modern brushed encounters were an opportunity not only to communicate with ‘men from afar’,Footnote 33 but also for scholars and literati on both sides to demonstrate their erudition. When the first Chosŏn embassies visited Japan in the early seventeenth century as part of efforts to heal the rupture caused by Hideyoshi's invasions, the neo-Confucian scholar and shogunal adviser Hayashi Razan (1583–1657) ‘was wont to trouble the Korean envoys with a barrage of unanswerable questions that seem to be meant to impress them with the weight of his erudition, rather than to elicit information’.Footnote 34 Exchanges of poetry were similarly fraught and skill in Chinese poetry was an important selection criterion when choosing national representatives. At the end of the sixteenth century, the Korean King Sŏnjo (r. 1567–1608) had issued a special order that the most talented poets should be chosen as the officials charged with receiving Japanese visitors since ‘if the talents of our men do not match theirs at times of exchange, we will be ridiculed in that country’.Footnote 35 Notably, the shogun's Confucian teacher Arai Hakuseki's (1657–1725) first collection of poetry, Tōjō shishū, contained a foreword by Sŏng Wan, the Korean secretary of mission to the 1682 embassy, and Hakuseki wrote in his autobiography that it was thanks to this endorsement that he was able to enter the Confucian academy of Kinoshita Jun'an (1621–98) and so launch his career.Footnote 36

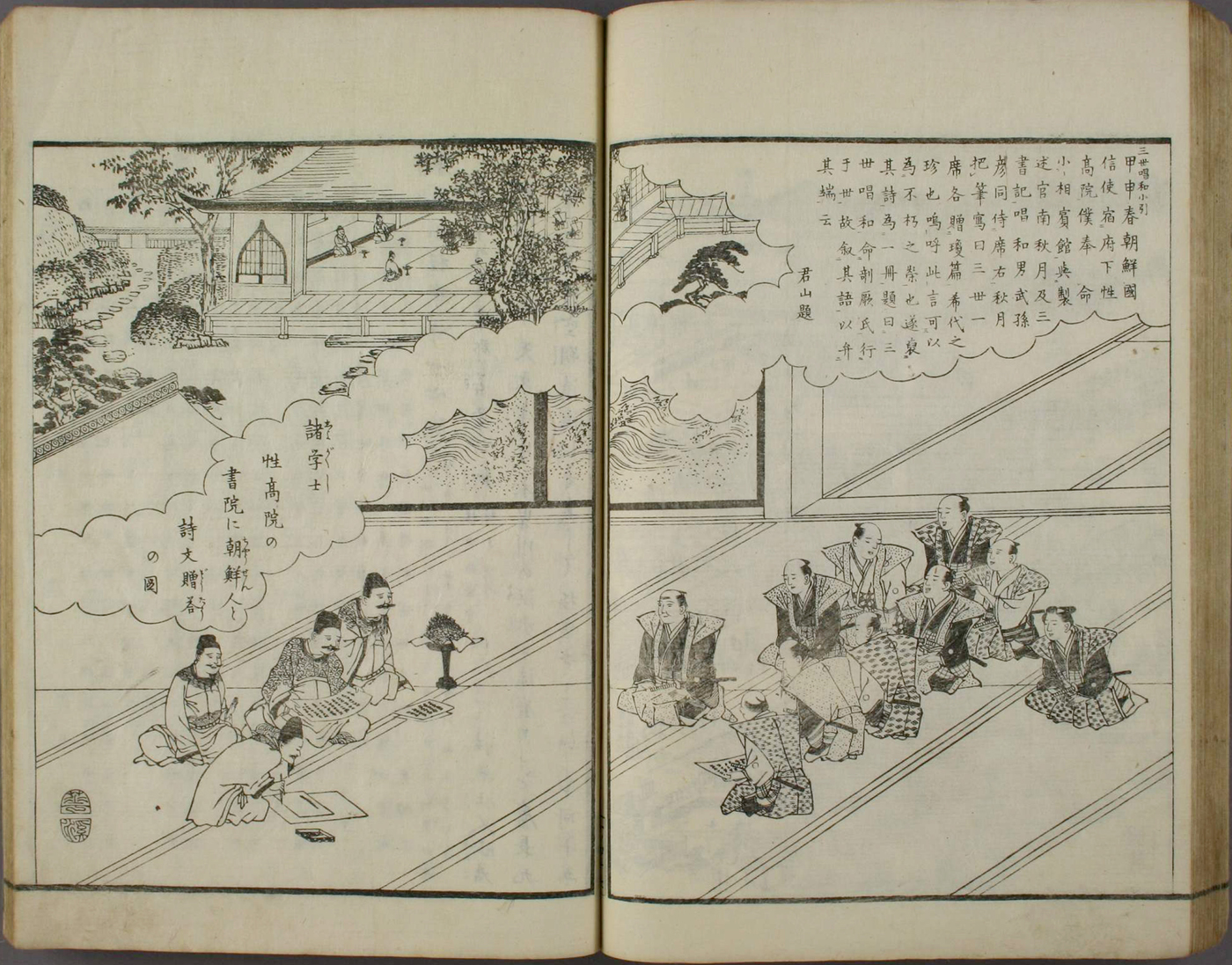

Although extensive records of the contents of many brushed encounters are extant, these offer scant self-referential explanation of how the practice operated. There are, however, some surviving illustrations, records of protocol and diaries of visiting diplomats which shed light on the situation. A woodblock print, one of the few early modern Japanese illustrations depicting a brushed encounter, survives in connection with the embassy of 1764, the penultimate Korean mission to visit Japan during the Tokugawa period, and the last to go all the way to Edo (Figure 1). The illustration, which was made some eighty years after the event it purports to depict, shows a meeting between Japanese scholars and Chosŏn representatives while the Chosŏn embassy was staying at the Shōkōin temple in Nagoya on their way to Edo. The Owari domain retainer Matsudaira Kunzan (1697–1783) with his son, grandson, and six other Japanese of samurai status are shown exchanging poems with the Korean secretary of mission (chesulgwan), Nam Ch'uwŏl (1722–70), who is supported by three Korean undersecretaries. The mood is calm: the spacious reception room is uncluttered, Ch'uwŏl peruses a preprepared poetic offering from one of the Japanese scholars, while an undersecretary transcribes a reply poem. The caption, written in Sinitic, details how the felicitous occasion and the poems exchanged by the parties were recorded in a book that was later published in Japan.Footnote 37

Fig. 1. ‘Japanese scholars exchange Chinese poems with visiting Koreans in the study of the Shōkōin Temple [1764]’ from Illustrated famous sites in Owari (Owari meisho zue, 1844). Courtesy of Waseda University Library.

The reality would have probably been far more chaotic. According to Tsūkō ichiran, a collection of historical documents relating to international relations compiled for the Tokugawa shogunate in 1855, the practice of brush talk became prevalent from the 1682 and 1711 missions onwards, and the number of volumes in existence which preserved these encounters had reached well over a hundred by the nineteenth century.Footnote 38 Shin Yuhan (1681–?), secretary of mission to the 1716 Korean embassy, recorded in his diary that he was bombarded with requests for brush conversation and poetry exchanges. The office of chesulgwan (‘secretary of mission’) may also be rendered as ‘auxiliary envoy and document official’ and involved composing documents in Sinitic throughout the course of the mission.Footnote 39 Both Yuhan and Ch'uwŏl Namok after him held the position of secretary of mission in their respective embassies, and the bulk of responsibility for responding to these voluminous requests for written communication fell to them and to their undersecretaries:

During the five days we stayed in Osaka we spent from evening until late at night with ten or so students. They had young attendants grind ink and present it to us, and it was impossible on any of the days we were there to have a moment to ourself…there were so many more people who pressed us to write for them than there had been in the various provinces that sometimes we were kept awake until the rooster crowed, and we missed our meals. It was hard going to respond to all of them, although I have heard that there were still more people who had been prevented from coming by the Tsushima Japanese.Footnote 40

Yuhan was correct in his assumption that the Tsushima officials were limiting access to his mission. According to a Tsushima retainer, Amenomori Hōshū (1668–1755), restrictions had been placed on brush talk since the 1682 embassy ‘because of a fear that if people engage haphazardly in brush talk and the like then affairs of state might be leaked’ – another indication of how prevalent the practice had become by the late seventeenth century.Footnote 41 Hōshū also personally felt that requests for written materials from the Korean visitors made too much work for senior Tsushima officials like himself who were forced to act as go-betweens, and wrote as much in his memorial to the Tsushima daimyo Sō Yoshinobu (1692–1730) in 1728, suggesting instead that requests be made through the head interpreter.Footnote 42 Hōshū also noted that the attempt to prohibit brushed communication between Japanese and their Korean visitors had no effect whatsoever.Footnote 43

An insight into the kinds of texts that were being requested of the chesulgwan is to be found in the suggestions Hōshū made to his lord, Yoshinobu, on how best to handle the excessive number of requests for brushed communications in the future: ‘if these are for a framed motto to be hung over a lintel then two or three texts only should be requested; if for writing on loose leaf Chinese paper then only that for use on a folding screen of two or six panels should be allowed’.Footnote 44

These particular requests were clearly for something other than a face-to-face written encounter and roughly correspond to the records contained in Korean sources. Yuhan claimed that while in Edo they ‘were left without a moment's peace’ as

There was a constant stream of literati visiting the Guest House. We were bothered endlessly for reply poems and brush talk. Other requests came from outside and arrived via Amenomori Hōshū…‘a forward for a poetry collection’, ‘a poem to match a painting’, ‘a eulogy for a portrait’, ‘a nature poem’, and so it went on. All of them made a request for a sample of our writing, stamped their name and left.Footnote 45

Yuhan's and Hōshū’s observations reveal that brush talk operated as part of a web of wider written possibilities. Those who were able to see the visitors in person sought to exchange Sinitic poems and to engage in conversations using brush talk, which they later collected and published in manuscript or print. Alternatively, there was also the option of less interactive requests for samples of the visitors’ brushwork which involved registering one's name on a list, and receiving in turn a piece of writing for a specific purpose. In addition, Tsūkō ichiran records that literati sent poetry to the embassy during their visits and received reply poems in response.Footnote 46 The bulk of direct encounters involving live brush talk thus took place between the Korean secretaries and Japanese scholars and literati who had or thought they had the necessary level of Sinitic learning, or between the Koreans and Japanese Buddhist monks, who often provided accommodation for the embassies at their temples.Footnote 47 Those who sought writing samples for their artwork, prefaces for poetry collections, and the like by petitioning the Tsushima retainers, or sent poetry to the visitors in order to receive a reply poem were likewise literati, probably of lesser influence. In addition, Hōshū disapprovingly mentions at least one daimyo, Kamei Korechika (1669–1731) of the Tsuwano domain, whose request for writing samples on Chinese paper to line the inside of a wooden chest proved so onerous that the Koreans were unable to complete it during their stay in Japan.Footnote 48

Unexpectedly, the possibility of brushed encounters between Korean visitors and Japanese residents in fact extended beyond the upper levels of the literati and the religious and warrior estates: there is evidence that townspeople were also involved on a more ad hoc basis. Bajō kigō zu (Calligraphy on horseback), a painting by Hanabusa Itchō (1652–1724), depicts a scene from the Chosŏn embassy parades, presumably in Edo where Itchō produced many of his paintings of city life after returning from exile in 1709 (Figure 2). In this painting, one of the Korean attendants on horseback has been waylaid by a townsman on foot who appears to have rushed out of the crowd. The footman, who should be leading the attendant's horse, has paused and is holding aloft an inkstone, looking about in a concerned manner as he stands on one leg as if he might have to dash off at any minute to rejoin the parade. The townsman holds up a piece of paper on which the Korean attendant is writing with a calligraphy brush. Whether the townsman's purpose is to obtain for himself an autograph from a visiting foreigner, or perhaps a sample of calligraphy for sale, is unclear. But this ink painting, with its lively brushwork and dynamic composition has all the hallmarks of having captured a moment the artist probably witnessed himself, and indicates that brushed encounters extended far further than staged brush talks between official representatives that the offical records would suggest. Although direct contact between visiting diplomats and people beyond the high-ranking members of the warrior or monastic estates is somewhat unexpected, the fact that townspeople might also be interested in participating in the civilized world of Chinese learning is not. The Tokugawa period saw increasing literacy rates as urbanization and market changes brought greater leisure time to artisans, merchants, and wealthy peasants.Footnote 49 This was accompanied by an interest in self-cultivation through education in the Japanese and Chinese classics, which were now marketed for these new readers through the burgeoning commercial print industry.Footnote 50 Chinese (and indeed Japanese) poetry societies flourished and their members brought together would-be literati from all walks of life.Footnote 51

Fig. 2. Calligraphy on horseback (Bajō kigō zu) (detail), by Hanabusa Itchō (1652–1724). Courtesy of Osaka Museum of History.

Despite its widespread popularity, none of these encounters suggests that brush talk was part of the most important official ceremonies. When it came to written documents, that role was occupied by the pre-composed letters in Sinitic from the Chosŏn sovereign, which each ambassador brought with him. These documents were given their own palanquin in the diplomatic procession and when the shogun's Confucian teacher, Arai Hakuseki, recorded the details of his overhaul of protocol for the meeting between the Chosŏn representatives and the shogun in 1711, he noted in great detail the timing and manner in which the documents were to be presented, opened, and finally read by the head of the shogunate's neo-Confucian academy.Footnote 52 In contrast, there are no prescriptions for brush talk in Hakuseki's extensive protocol records, nor is there mention in the briefer and earlier record of the 1617 embassy written by the neo-Confucian scholar and shogunal adviser Hayashi Razan.Footnote 53

Yet, both Razan and Hakuseki did engage in brush talk with Korean representatives during their stay, and numerous records of such conversations survive. As in the examples quoted above, these encounters usually took place at the temporary residence of the embassy – in Edo, usually the Higashi Honganji temple in Asakusa – or else they occurred in the interstices of official ceremony, such as a conversation about music that took place between Hakuseki and Korean representatives during a musical entertainment at a shogunal reception for the embassy that was held in Edo on the third day of the eleventh month of 1711.Footnote 54 As discussed below, brush talk nonetheless played an important role in the peripherial rituals surrounding each embassy visit, a role regarded as more prestigious than oral interpreting.

VI

The use of the Chinese writing system and brush talk for communication in the absence of the ability to speak Chinese was possible because the Chinese writing system uses not an alphabet but logographs: characters representing words or parts of words. Originally, these characters were intended to represent words in Chinese.Footnote 55 Being logographs and therefore able to represent entire words, however, classical Chinese characters are not limited to representing words in Chinese and may be associated with any language. As the Chinese writing system was brought to parts of East Asia that did not have writing of their own, Chinese loanwords entered these languages and Chinese logographs came to be associated with indigenous words. Over time, localized reading traditions developed that allowed East Asian intellectuals to decode the logographs and syntax of Chinese texts mentally or aloud in their own language; throughout East Asia, elites learnt Chinese writing from childhood.

The association of Chinese logographs with local words and reading traditions for decoding Chinese syntax allowed not only the reading of Sinitic texts but also textual production.Footnote 56 Such was the authority of Chinese learning that even after the development of local scripts, in scholarly and religious writing logographs were used to produce texts which adhered to the norms of Chinese syntax, giving a surface appearance of a Chinese text despite the absence of spoken Chinese language ability. In Korean, the methods for using written Chinese as a vehicle language were known as kugyŏl (lit. ‘oral formulas’) and idu,Footnote 57 and in Japanese are grouped under the rubric of kundoku (‘reading by gloss’).Footnote 58 These Korean and Japanese methods involved glossing a Chinese text with graphs indicating how the logographs might be rearranged so as to conform to the syntax of Korean or Japanese, as well as helping to identify nouns, verbs, etc. Unlike Japanese and Korean, Vietnamese is not an inflected language and so Vietnamese systems of glosses developed punctuation and pronunciation guides but not guides to syntactical rearrangement.Footnote 59

These various methods for reading and producing a Sinitic text served to obscure the fact that translation was occurring since readers from different backgrounds could read the one Sinitic text according to their own traditions, without the production of a separate, written translation. The practice of communicating with the brush in East Asian diplomatic encounters thus emphasized mutual participation in a transnational sphere of shared intellectual culture, enacting the appearance of harmony and at the same time emphasizing the claims of each state to their advanced level of civilization. A common expression from the ancient Chinese classic The greater learning (Daxue) that was used to describe Korea's inclusion in the Chinese world order was ‘writing in the same script; carts with the same axle widths’: a unification of culture that was seen as parallel to the apparent union of political institutions. In the East Asian Sinosphere, writing and culture were thus inseparable and embedded in the concept of classical Chinese learning (Ch. wen, Kor. mun, Jp. bun).Footnote 60

Wen/mun/bun included poetry, which was a vital part of brush talk, and the long history of classical Chinese poetry provided a rich source of metaphor and allusion from which the educated men of East Asia could draw upon in their communications. In diplomatic exchanges, the images employed involved tropes of travel – long roads, tear-soaked robes of parting, and sea voyages – as envoys shared their common experience of travel, and their sadness at leaving their hosts. Another common theme was polite references to wise rulers, or sage kings, accompanied by hopes for lengthy and felicitous reigns.Footnote 61 The practicalities of Chinese-style poetry themselves emphasized harmony thanks to the practices of composing poems in reply to a poem offered by another or producing a chain composition by several authors.Footnote 62

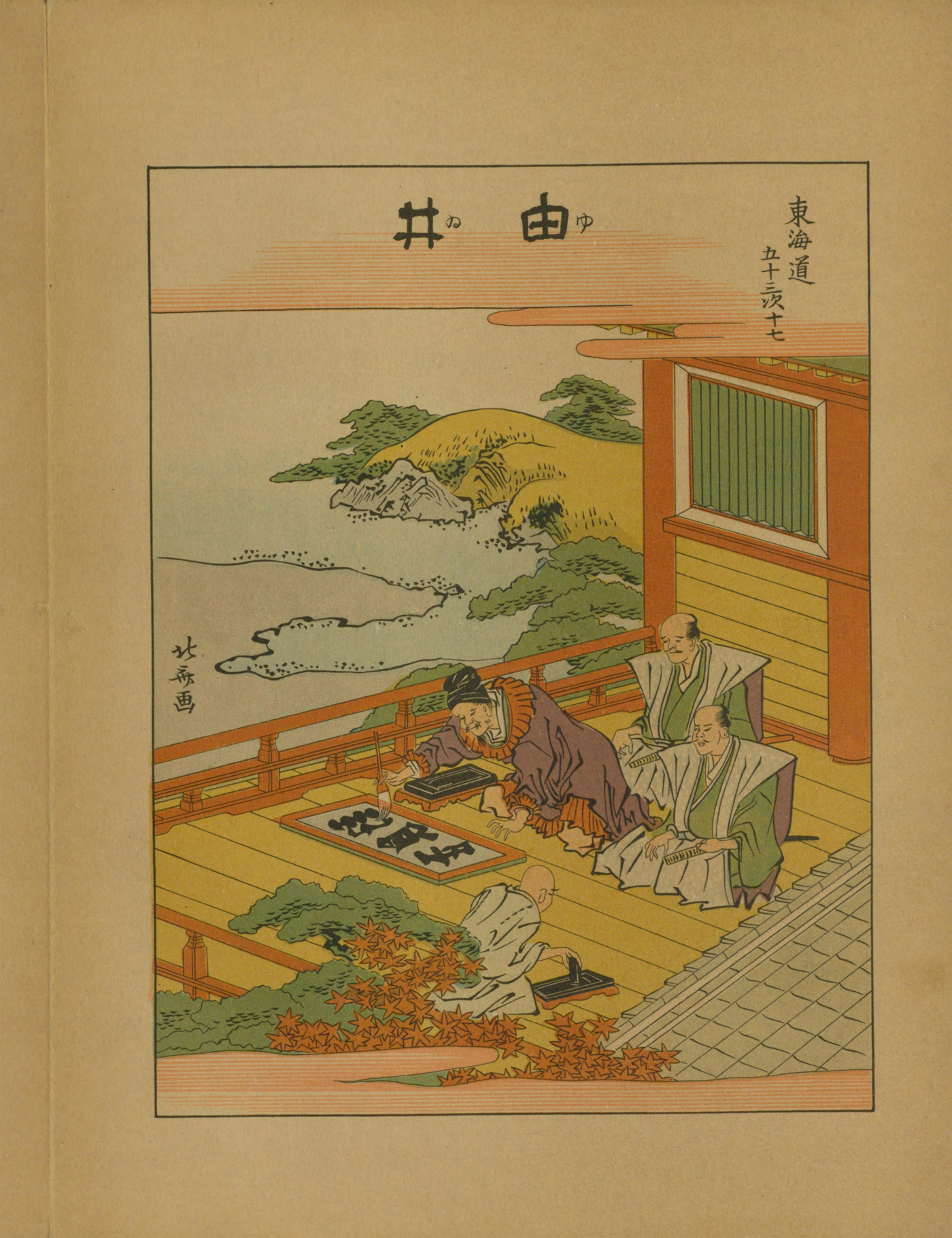

The appearance of harmony and the opportunity to show off which were occasioned by brush talk are two reasons why the practice persisted even though an ostensibly simpler means of communication was available in the form of interpreters. The encounters detailed above offer two additional reasons. The first is the significance of the visual, calligraphic element of East Asian writing. In requesting writing samples to adorn decorative screens, paintings, or even the inside of furniture, petitioners were seeking not only the contents of the inscription but the visual and artistic component provided by the hand of the foreign visitor. In addition to the best scholars and poets, the personel of diplomatic missions to Japan therefore also included talented calligraphers and painters.Footnote 63 This can be seen in practice in an illustration from The fifty-three post-stations along the Tōkaidō highway by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), which shows a Korean representative writing a calligraphic inscription with the name of a temple, the Seikenji in Yui (in modern day Shizuoka), while his samurai escort looks on and a monk grinds ink (Figure 3). Used in this way, Sinitic writing was a visual addition to the repetoire of performative cultural skills that emissaries employed to demonstrate their participation in the world of civilized learning.

Fig. 3. ‘Yui’ from The fifty-three post-stations along the Tokaido highway (Tōkaidō gojūsanji), by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), 1931 reprint. Courtesy of National Diet Library of Japan.

The second reason why brush talk operated in parallel with oral interpreting, rather than being replaced by it, is that brush talk provided a more prestigious and direct conduit for communication between host and visitor, one which preserved a record of their conversation. Records from the early eighteenth century show, for example, that when the daimyo Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu (1658–1714) met with Chinese monks who were then living in Japan, he used interpreters for general communication but switched to brush talk when discussing important matters such as the regulation of Buddhist orders, or abstract questions of Buddhist teaching.Footnote 64 In this way, brush talk provided a means for Yoshiyasu to communicate directly with his Chinese counterpart and allowed for the preservation of a record of their conversation for posterity, something Yoshiyasu was keen to encourage for the positive light it shed on his erudition. Despite his repeated contact with Chinese monks over many decades, there is no evidence that Yoshiyasu aquired the ability to speak Chinese, prefering to delegate that responsibility to interpreters and house scholars, a division of labour consistent with contemporary attitudes in East Asia, which held oral interpreting to be a low-status activity. At the Chinese court, oral interpreting had from ancient times been the responsibility of lower-ranked functionaries known as ‘tongue men’ (sheren).Footnote 65 In Japan, oral intepreting was outsourced to hereditary families of interpreters based in the port cities who were often derided by contemporary scholars for their lack of a proper (i.e. Sinitic) education.Footnote 66 And in Korea, interpreters were excluded from the centre of power and barred from taking the civil service examination that was the ultimate source of intellectual prestige at the Chosŏn court.Footnote 67

Returning to the Korean embassies in Japan, the following rather touching scene narrated in detail in Shin Yuhan's diary shows the differing functions of writing and oral communication during an encounter between Yuhan and his Japanese host, the high-ranking warrior Makino Tadatoki (1665–1722). In the diary, Tadatoki, who was the governor of Suruga province, is described as someone who ‘does not know his [Sinitic] letters’. However, ‘he values learning and would come and sit in the reception rooms whenever we were exchanging poems with his Confucian house scholars, watching with enjoyment’.Footnote 68 Yuhan then describes how Tadatoki came to visit his rooms unexpectedly one day:

He called one of the Tsushima interpreters and spoke with me:

‘I studied a little when I was young but in the end didn't learn to read. Then I grew up, and since it came to pass that I have official duties with many trivial tasks I ended up being unable to use writing. But in my chest beats a heart that loves learning and literature. When I watch scholars wielding the brush and ink I am filled with unbearable yearning. I have been busy with my official duties and haven't been able to speak with you. I had a free moment so I have just come to pay you a visit.’

I took out a length of paper and wrote a few words of thanks and showed it to him. He looked at it and stroked it for a moment. Then he got up to go, and as he left said ‘I will reply to you in writing.’

The next day his representative arrived and presented me with a scroll. The writing left something to be desired but the sentiment had a certain charm. At the end he had written his name ‘Yours respectfully, Minamoto Tadatoki, Lord Makino of Nagaoka and Governor of Suruga’.Footnote 69

The Japanese warrior ruler, who, as Yuyan tells it at least, does not have sufficient Sinitic literacy to communicate with the Korean using brush talk, must to his regret rely on oral interpretation. Once Yuhan has understood the nature of Tadatoki's communication via oral interpretation, he replies to Tadatoki directly in writing, a gesture which clearly appeals to the governor, so much so that he goes away and laboriously prepares his own response. Tadatoki's wistful stroking of Yuhan's calligraphy, which he cannot read well or produce himself, encapsulates the multi-faceted appeal of brush talk as a means of communication, a direct link to his visitor, and a visual manifestation of participation in the world of East Asian learning.

VII

Given its use in overcoming linguistic differences, it would be natural to think of Sinitic brush talk as a kind of lingua franca. As a linguistic system that united a sphere of cultural and diplomatic exchange, classical Chinese, or Sinitic, certainly has obvious points of comparison with lingua francas in world history. However, the examples investigated above remind us that brush talk in early modern East Asian diplomacy was not a lingua franca in the strict sense. Since Sinitic is primarily a system of written signs and syntax and not a spoken language, the metaphor of the tongue, from which the word lingua derives its etymology, is a poor fit and indeed Wiebke Denecke has recently suggested the term scripta franca as a more appropriate alternative.Footnote 70 The term lingua franca Footnote 71 originally referred to a pidgin spoken among traders along the south-eastern coast of the Mediterranean between the fifteenth and the nineteenth centuries, and was later applied in a more general sense to any language that is used by speakers of different languages as a common medium of communication.Footnote 72 In neither of these senses is Sinitic unproblematic. It is not a pidgin (which involves hybridization of two or more languages, together with simplified grammar and syntax) as in the original sense of lingua franca. Nor was it a spoken language by the early modern period, and may in fact never have been a spoken language, even at the earliest stage of its history. In this, Sinitic is unlike French and Latin, the languages that were used in face-to-face diplomatic communication in Europe, although Latin's links with the spoken language also became more distant over time.

Douglas Howland, when observing that brush talk defies the primary categories of both speech and writing, described the practice as a ‘the purest example I have seen of a written linguistic code’.Footnote 73 Indeed the written aspects of Sinitic match this description well: in the nineteenth-century examples cited by Howland, word play, classical allusions, and juxtaposition between the received meaning of the Sinitic logographs used to write a word and the modern nuances of the Chinese or Japanese word itself (which by that time had often been influenced by Western ideas), operated side by side to add layers of meaning to the communicative exchanges between Japanese and Chinese intellectuals. It is worth noting, however, in addition to this written, linguistic play, that brush talk as practised in early modern East Asian diplomacy often had important visual, performative aspects as well, and these too take it beyond the realm of how a lingua franca is usually conceived. In early modern diplomacy, the use of Sinitic took the form of stylized written performances that were at times as much about ritual display, calligraphic art, and drawing upon a shared storehouse of civilized learning as they were about communicating factual content through language. This aspect is best captured by the third and looser meaning of the term lingua franca: ‘figurative contexts. A generally understood or commonly used standard, system, or means of non-verbal communication.’Footnote 74

The visual, performative aspects of brush talk are also a reminder that, like Sheldon Pollock's example of Sanskrit,Footnote 75 Sinitic was spread by non-coercive means, by individuals who saw themselves as participating, or who wished to participate, in the sphere of Chinese civilization. As Benjamin Elman has noted, in this sense Sinitic has more in common with Sanskrit than with Latin,Footnote 76 Sinitic's most common point of comparison but one that was spread by the Roman Empire, and was a spoken language as well as a written one.

Although not a lingua franca in a strict sense, in the case of Japanese and Korean encounters, the poetry and classical prose communications occasioned by brush talk functioned as a collaborative means of promoting the appearance of unity. In fact, due to the nature of the Chinese writing system the act of translation itself was obscured. Glossed methods for reading and writing Sinitic thus challenge received assumptions about translation, and were even conceived of as reading, rather than translation at the time.Footnote 77 Being for the most part transcribed as glosses upon a source text or performed mentally without the aid of glosses at all, such methods did not involve the production of an obvious target language document, although a target language ‘text’ was produced when the glosses were used to perform a reading either mentally or aloud. In the case of Japanese and Korean methods, syntactical distance from Chinese further meant that such highly bound translation methods produced a target language that was a stylized translationese, described in a different context by Indra Levy as a ‘tertiary language, one that is neither entirely “foreign” nor “domestic”, but that clearly mediates between the two’.Footnote 78 The realities of the Chinese writing system and its use in East Asia provided a means for obscuring cultural difference – drawing on a shared literary heritage and acting as a forum for the exchange of calligraphy, poetry, and philosophy – by not drawing attention to translation. In diplomacy, we may therefore understand Sinitic as a surface finish that obscured the reality of a fractured linguistic environment in the East Asian Sinosphere and promoted the appearance of harmony, and emphasized the claims of each state to their place in the civilized, East Asian world order.