Led by local guides across the Isthmus of Panama in 1513, the Spaniard Vasco Núñez de Balboa saw and named the ‘South Sea’. Europeans first sailed into the great ocean in 1521 with the Spanish expedition of Magellan, who called it the ‘Pacific Sea’.Footnote 1 In striking contrast, modern human beings have occupied Near Oceania (Australia, New Guinea, and nearby islands) for 40,000–65,000 years. Seafaring coastal dwellers, probably from Taiwan via Island Southeast Asia, commenced their epic spread through the far-flung islands of Remote Oceania about 4,000 years ago (Figure 1).Footnote 2 In ongoing Indigenous experience, the ocean comprises an overlapping series of lived-in ‘native seas’ constituting a ‘Sea of Islands’.Footnote 3

Fig. 1. CartoGIS, ‘Oceania sub-regions’ (2018), CartoGIS Services, ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, CAP 00–373, http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/mapsonline/base-maps/oceania-sub-regions

Before 1750, the insular Pacific was scarcely known by Europeans, apart from Guam which the Spanish visited regularly after 1565 and colonized from 1668 as a port of call on the galleon route linking Acapulco and Manila. Globally, the ocean was a cartographic vacuum, a zone of fantasy and speculation dimly informed by erratic palimpsests of sporadic Spanish, Dutch, or privateering voyages, which ‘discovered’ specks of land but mostly lost them again due to technical incapacity to determine accurate longitude at sea. From 1750 to 1803, French, British, and to a lesser extent Spanish navigators and savants dominated the exploration, naming, and cartography of the Pacific. A series of grand scientific expeditions – notably those of Bougainville, Cook, La Pérouse, Malaspina, Bruni d'Entrecasteaux, Baudin, and Flinders – gave firm empirical substance, or at least reliable coastal outlines, to most of the islands, archipelagoes, and land masses of the central and western ocean, on the back of technical advances in position-finding using marine chronometry or lunar distances with an almanac.Footnote 4 Until 1816, however, the vast coral archipelagoes of the northern and eastern Pacific were cartographic mysteries, dotted with fickle islands and real or imagined reefs which made navigation unpredictable and dangerous. The extent and limits of early nineteenth-century European knowledge of the Pacific Islands are epitomized in multi-sheet charts published by the eminent British cartographer Arrowsmith and the Spaniard Espinosa.Footnote 5

A hiatus in Franco-British Oceanic voyaging after 1803 occasioned by the Napoleonic wars was filled by several Russian expeditions, despatched in the interests of geopolitical and commercial advantage and imperial glory. Their significance over the next quarter century is still inadequately acknowledged in anglophone, francophone, or even Russian histories. By this stage, the Enlightenment era of heroic round-the-world voyages of ‘discovery’ was in transition to a more mundane modern phase of survey and consolidation. However, Russian contributions to the surveying, charting, and systematic mapping of the still little-known Tuamotu, Marshall, and Caroline archipelagoes transformed Euro-American practical and geographical knowledge of the world's largest ocean.

Our general rubric is Russian place naming in the Pacific Islands undertaken during successive imperial expeditions between 1804 and 1830.Footnote 6 We correlate Russian toponyms for Pacific places registered in diverse genres of cartographic and written texts: map, atlas, journal, narrative, and hydrographic treatise. We probe varied entanglements of precedent, personality, circumstance, and embodied encounters with people or places that motivated the toponymic choices of individual voyagers and their material expressions. We consider a series of textual moments involving place names: the dutiful default option of honorific eponymy (application of a person's name to a place); located experience (which generated many place names); inscription in specific charts and maps (which fixed such practical knowledge); and synthesis in regional atlas or scientific treatise (which rendered the concrete abstract).

This toponymic focus is scaffolding for a threefold ethnohistorical inquiry: into the implications for Russian naming practices of Indigenous agency or the power of place during situated encounters;Footnote 7 into the geographical knowledge conveyed to Russian voyagers by Indigenous interlocutors; and into the presence or absence of such knowledge in specific sets of toponyms or different textual genres. We argue that travellers’ names for Pacific places were often influenced by the perceived demeanour of Island populations met in situ; that the availability of Indigenous knowledge was a product of the degree of communication and emotional connection established between particular voyagers and Islanders in specific contexts; and finally, that the value accorded local knowledge depended on the experience and inclinations of individual Russians but also on the genre of text in which it was recorded or ignored.

Our emphasis on the impact of located experience and Indigenous presence in the charting of the Pacific parallels important trends in global cartographic history from the 1980s, when a new critical literature began to challenge the Eurocentrism of the orthodox historiography of cartography. Henceforth, the power and ubiquity of Indigenous wayfinding capacities and geographic knowledge have increasingly been recognized.Footnote 8 So too have dialogic elements in imperial and colonial mapping and their co-production with local experts or intermediaries. Much of this scholarship refers to early or putatively colonial settings, particularly in the Americas but also in South Asia.Footnote 9 However, the contexts addressed in this article, during fleeting encounters between resident Pacific Islanders and transient European scientific voyagers, were in no sense colonial. They parallel those considered by Bravo in the Arctic and the North Pacific and by Eckstein and Schwarz in relation to the innovative cartography synthesized by the Ra‘iātean priest-master navigator Tupaia, in collaboration with Cook and his officers, during the Endeavour’s Pacific voyage in 1769–70.Footnote 10

Our empirical base is the toponyms bestowed or recorded by naval officers and naturalists in the eastern and northern Pacific Islands during expeditions led by the Baltic German circumnavigators Adam Johann von Krusenstern (1803–6), Otto von Kotzebue (1815–18), Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen (1819–21), and Friedrich von Lütke (1826–9). These and other voyagers contributed over seventy Pacific place names to Russian cartography.Footnote 11 Most never appeared in non-Russian maps and probably no more than a dozen are still used outside Russia. But however ephemeral, Russian toponyms constituted part of the vast stock of historical raw material from which Krusenstern later created the authoritative pioneer atlas of the ‘South Sea’/‘Pacific Ocean’. Published in Russian and French editions in the mid-1820s and partly revised a decade later, Krusenstern's atlas was supplemented by dense companion volumes of ‘hydrographic memoirs’.Footnote 12 His confident, abstract naming of places in these synthesizing products of cosmopolitan scholarship contrasts with the often uncertain empirical practice of voyagers in situ, including his own. Krusenstern's expedition and legacy are the focus of the next two sections.

I

Russia reached the ‘Pacific Sea’, as distinct from its northern littorals, in March 1804, when Krusenstern entered the great ocean on the Nadezhda, in consort with the Neva under Urey Lisiansky. By then, the Russian Empire had been gradually advancing eastward for 250 years. The conquest of Siberia was followed by colonization of the Far East from Sakhalin to Chukotka and the establishment of colonies in north-western America.Footnote 13 Various place-naming strategies materialized this expansion: re-use of existing Russian names, sometimes with the prefix Novo- (New) (Novoarchangelsk); eponyms of saints (Petropavlovsk), explorers (Bering), and conquerors (Khabarovsk); and local names (Chukotka Peninsula). The slow Russian advance meant that settlers lived and often intermixed with Indigenous populations. Some Indigenous names (such as Kadjak) were absorbed into regular Russian usage in a long-term, organic process.Footnote 14

Krusenstern's expedition, although initially set up as a trade venture, gave a new direction to Russia's imperial enterprise – pelagic exploration, emulating the voyages of Cook and La Pérouse. Krusenstern was scion of a cultivated family in Estonia with wider European connections. Partly trained in the British Royal Navy, he had travelled widely, including to the East Indies, China, and the United States.Footnote 15 The physical presence of his expedition in the Pacific confirmed the need for reliable, systematic mapping of the ocean's emergent geographical reality. Löwenstern, fourth lieutenant on the Nadezhda, described his captain's scholarly preoccupation after the vessels entered Pacific waters:

Descriptions of voyages have piled up. One would need years to read them all. The confusion of names in the South Seas causes a lot of errors, and, since every country calculates longitude based on its capital city, errors arise in determining coordinates. Krusenstern has begun to sever this Gordian knot and has already filled several notebooks.Footnote 16

Krusenstern had impeccable credentials for this work of hydrographic and cartographic synthesis. As a practical navigator who knew ‘from experience’ the importance of consistent, standardized nautical maps, he chose Greenwich as his prime meridian, despite publishing in French and Russian. As a scholar, fluent in several European languages, he was well connected in Russian and Western European maritime circles – notably by ‘friendship’ with his distinguished predecessors Arrowsmith and Espinosa whose charts of the Pacific Ocean, Krusenstern argued, were on ‘too small a scale’ for navigational use. His ‘more detailed’, groundbreaking atlas supplants these charts with ‘special’ maps of individual island groups drawn on a consistent ‘large scale’. His hydrographic memoirs include systematic critique of earlier cartographers’ geographical nomenclatures and co-ordinates.Footnote 17

In the event, Krusenstern's own voyage was curtailed by tasks imposed in the far north Pacific by the Russian emperor and the expedition's sponsors, the Russian-American Company. Its scope was further circumscribed by an ongoing conflict aboard the Nadezhda with the emperor's representative Nikolai Rezanov.Footnote 18 These constraints gave Krusenstern little time for new ‘discoveries’. His eyesight failed after his return to Russia, leaving him unable to lead new expeditions. However, his protégés Kotzebue and Bellingshausen, who served under him on the Nadezhda, later fulfilled his aspiration to map uncharted areas of the Pacific. Their voyages and that of Lütke constitute the high points of Russian Pacific exploration in the first three decades of the nineteenth century: in total, twenty-five Russian voyages crisscrossed the Pacific Ocean from 1804 to 1835.Footnote 19

II

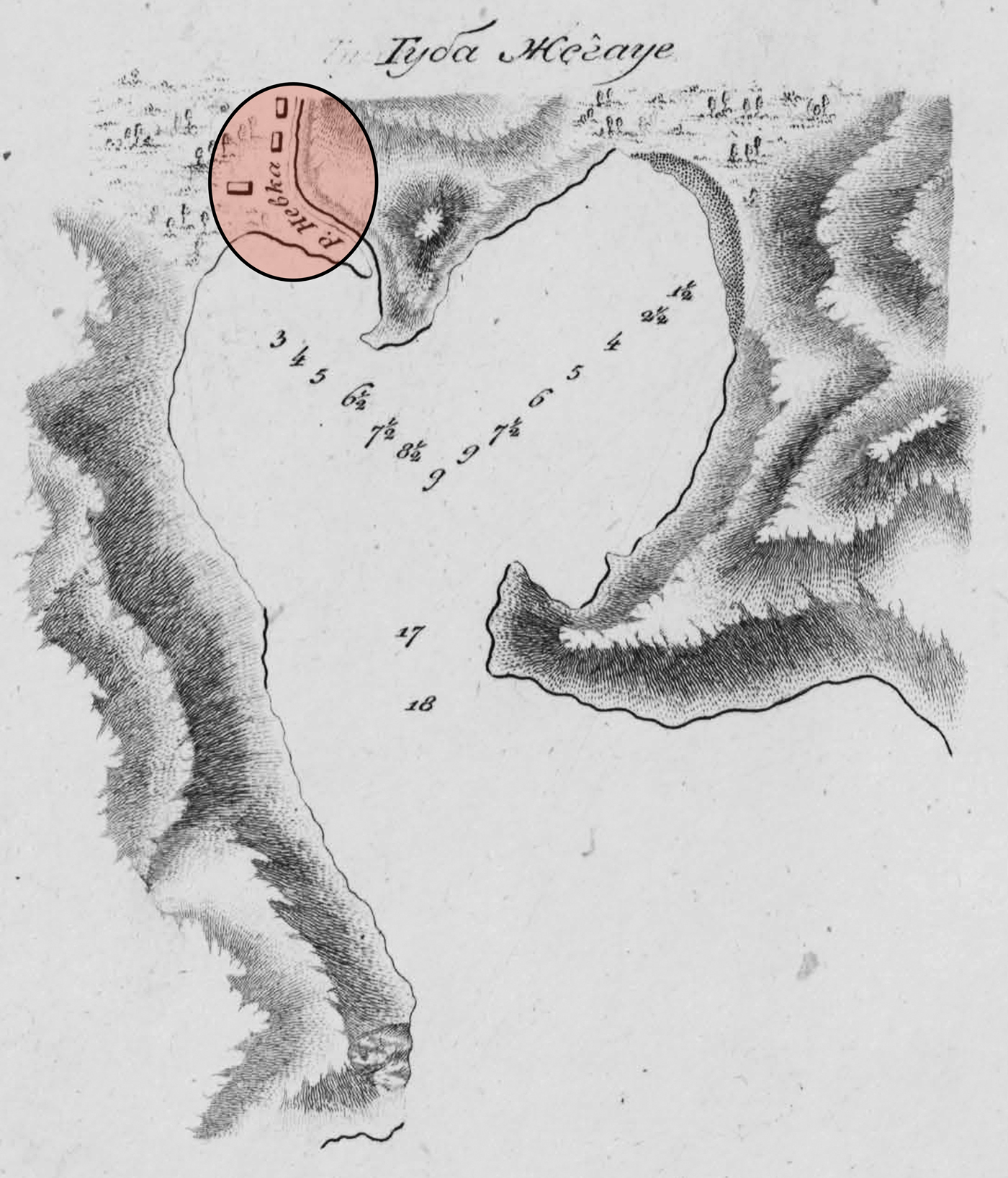

Like most voyagers,Footnote 20 these Russians routinely imposed eponyms extraneous to places thus named: they recognized sponsors and supporters, expedition participants or vessels, or military heroes of the Napoleonic wars. Eponymy was a prominent strategy in place naming during the twelve-day stopover of Krusenstern's expedition at Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas, especially in the early stages and by Krusenstern himself. This was the first Pacific archipelago encountered by the Nadezhda and the only one visited more than fleetingly by the expedition. Having explored a spectacular harbour, Krusenstern claimed in the published narrative of his voyage: ‘The natives had no particular name for this harbour…I have therefore named it Port Tschitschagoff in honor of the minister of marine.’Footnote 21 Yet his unpublished journal indicates that he initially named the bay ‘Port L.’, probably after Löwenstern, the officer who first saw it.Footnote 22 A few days later, Krusenstern and most of his officers rebelled against the emperor's representative Rezanov and thus against the emperor's own authority. Perhaps prudently, Krusenstern later opted for the conciliatory official eponym Chichagov (Tschitschagoff). In contrast, the visitors were charmed by the rivulet Vai'oa, which reaches the sea at this port. Lisiansky called it Nevka (Little Neva) after a branch of the Neva River in St Petersburg, for which his own ship was named.Footnote 23 This toponym, which appears only in the Russian version of Lisiansky's atlas (Figure 2),Footnote 24 was probably prompted by the personal appeal of the site, rather than the pragmatic discretion which induced Port Chichagov.

Fig. 2. Iurii Lisianskii, ‘Guba Zhegaue’ (Zhegaue Cove) (1812), inset showing ‘R. Nevka’, in Sobranie kart i risunkov, prinadlezhashchikh k puteshestviiu…na korable Neva (Collection of maps and drawings from the voyage of…the Neva), plate [3], National Library of Russia, St Petersburg, К 2-Тих 9/49, https://vivaldi.nlr.ru/ca000000006/view#page=5

In keeping with the ethos of scientific voyaging imbibed in particular from Cook, these voyagers tried to learn Indigenous place names, albeit with varied interest and commitment. Krusenstern recorded the name Schegua for the valley around the western cove of Port Chichagov; Lisiansky called it Zhegaue in Russian and Jegawe in English; while Löwenstern called the port Gekauve Bay.Footnote 25 The German naturalists Langsdorff and Tilesius provided especially valuable traces of local names, no doubt because such information fell within their scientific remit and they spent more time ashore interacting personally with the inhabitants. According to Langsdorff, correcting Krusenstern, the Indigenous name of Port Chichagov was Hapoa while the valley near this harbour was ‘called Schegua and another nearby bordering it Thanahui’.Footnote 26 Tilesius listed local toponyms as Tschequa for the valley and Janaue, Janaui, or Schanaui for the bay.Footnote 27 The western cove and the valley running north from it are known today as Hakaui, perhaps anticipated in the visitors’ Thanahui/Janaui/Schanaui. Their struggles to record Indigenous names at Nuku Hiva demonstrate, as Langsdorff acknowledged, ‘how difficult it must be for a stranger to express the correct sounds’.Footnote 28

III

Eponymy also figured largely in Kotzebue's place naming during his voyage on the Riurik, but this nod to obligation was ultimately qualified by his experience of longer, more intimate relations with local people and places. Undertaken with the explicit object of making ‘new discoveries’, Kotzebue's expedition ultimately fulfilled his mentor Krusenstern's thwarted dream.Footnote 29 In 1816, during a rapid passage from Chile to Kamchatka, Kotzebue saw and named several purportedly ‘unknown’ islands in the Tuamotu, northern Cook, and Marshall groups – unaware that most had been previously, if inaccurately, recorded by Europeans under diverse toponyms. At this point, all his place names honoured Russian eponyms – officials, war heroes, or naval officers.Footnote 30 Chamisso, a naturalist on the expedition, commented dryly: ‘we call most of these people and tribes, mentioned by us, by names which they did not give themselves, but which were imposed upon them by strangers. And this is the case with most people on the earth’.Footnote 31

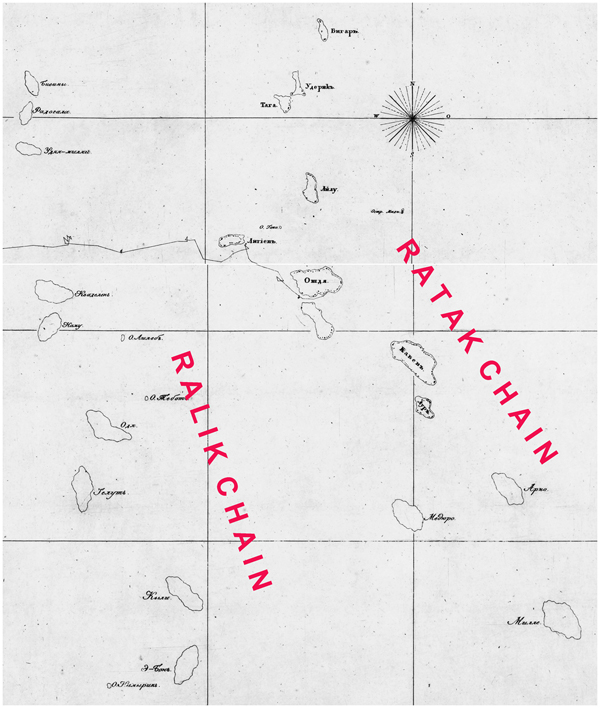

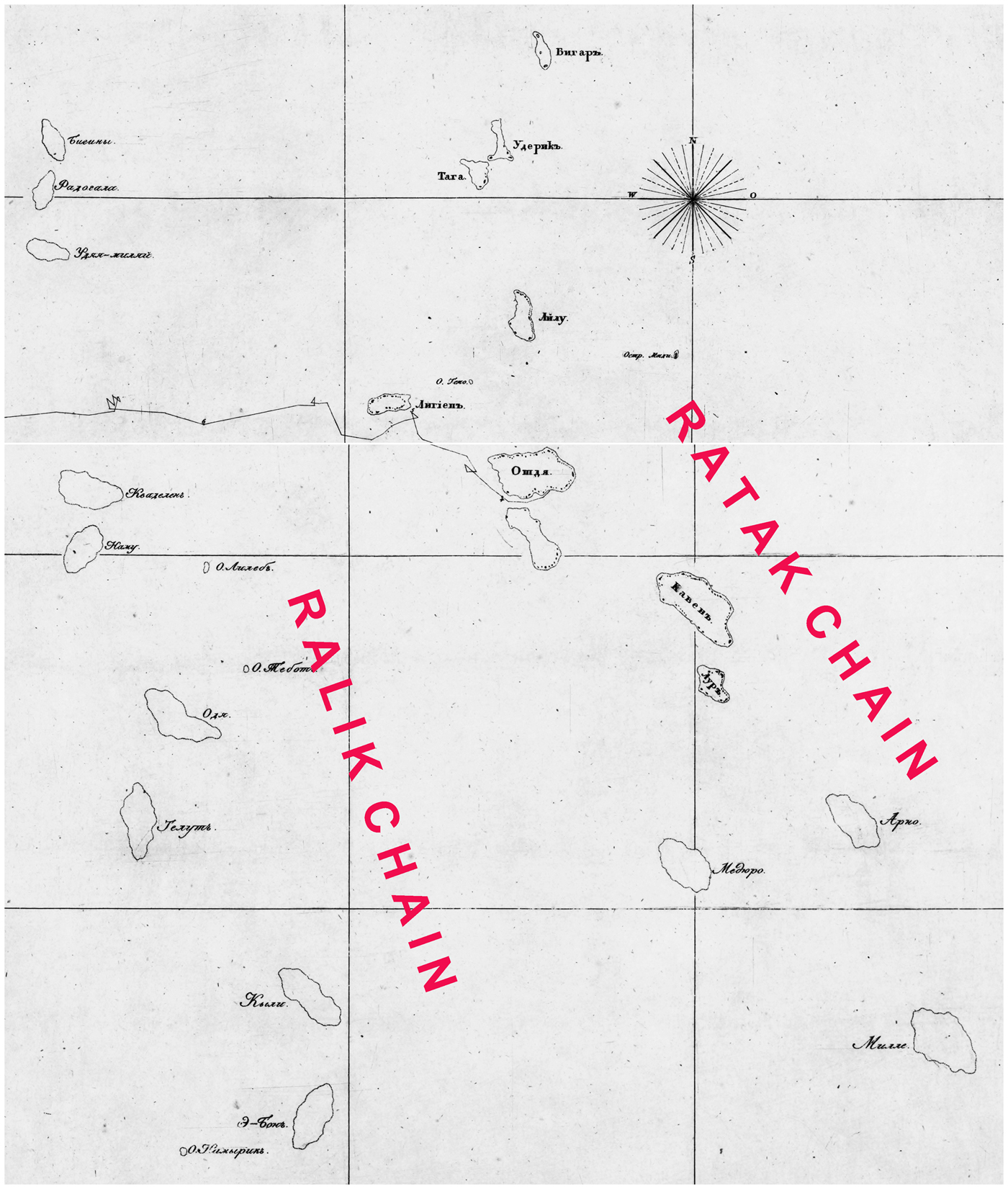

Overall, however, Kotzebue's toponymy differs markedly from Krusenstern's, because Kotzebue was deeply influenced by more or less lengthy stays at several atolls in the Marshall Islands in 1817. After initial trepidation, having not previously encountered such foreigners, the inhabitants warmly welcomed the Russians.Footnote 32 Some communicated detailed geographical knowledge which Kotzebue transcribed in the atlas of his voyage. In a map of ‘the coral islands found by Riurik’, he used a double nomenclature for newly ‘discovered’ atolls, with Russian names positioned above Indigenous ones. Another map (Figure 3) inscribes only local names for both the Marshall Islands’ twin chains, learned from interlocutors at various islands in the eastern Ratak Chain.Footnote 33 Kotzebue did not visit the western Rālik Chain until 1825, during a subsequent expedition to the Pacific.Footnote 34

Fig. 3. Otto Kotsebu, ‘Merkatorskaia karta Tsepi koral'nykh ostrovov Radaka i Ralika’ (Mercator map of the Ratak and Rālik chains of coral islands) (1817), detail, in Atlas k puteshestviiu…na korable Riurike v Iuzhnoe more i v Beringov proliv (Atlas of the voyage…on the ship Riurik to the South Sea and Bering Strait), plate [11], National Library of Russia, St Petersburg, К 2-Тих/48, http://vivaldi.nlr.ru/ca000000008/view

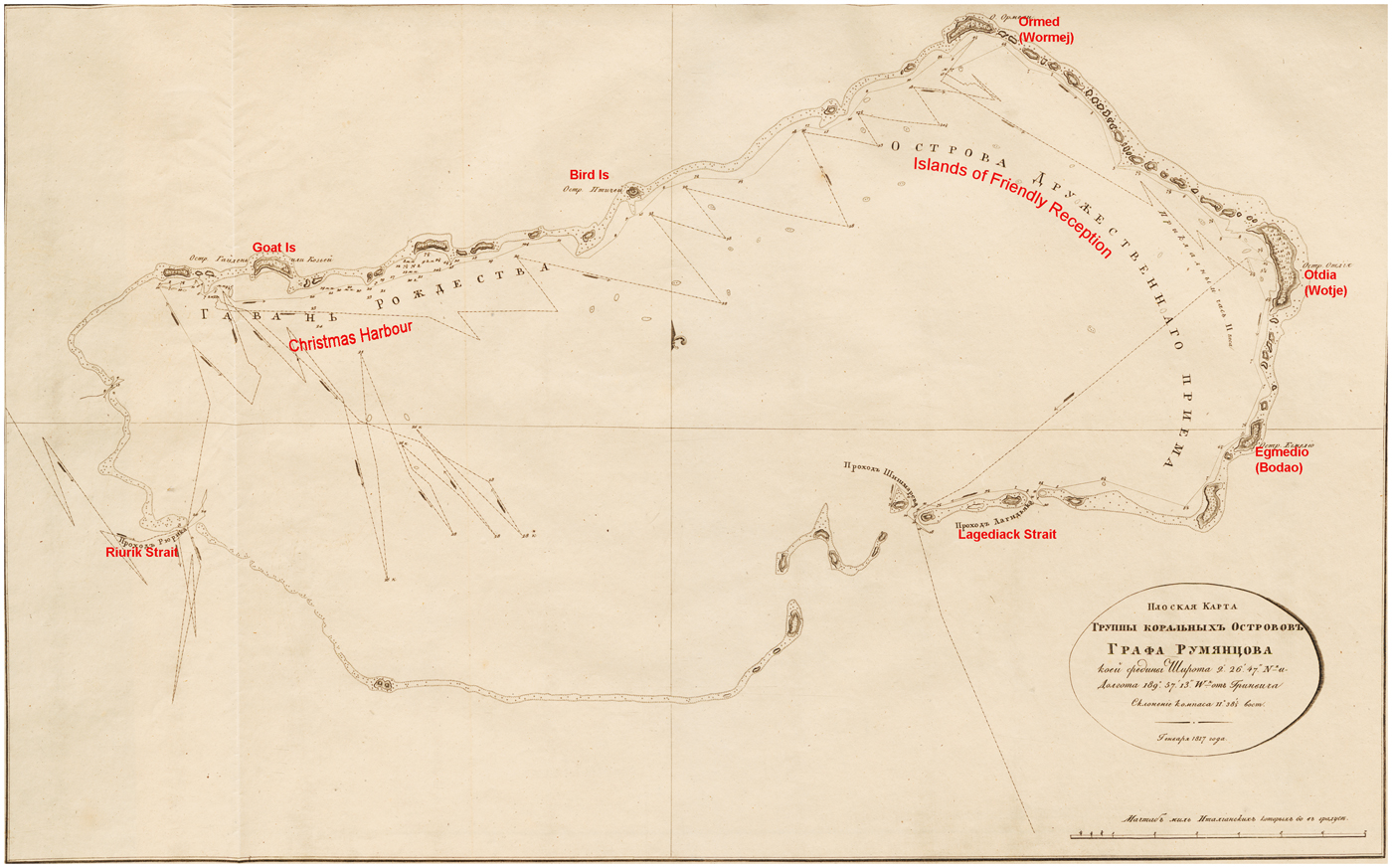

Kotzebue's more detailed charts equally reflect his emerging personal experience of specific places and populations. On 1 January 1817, sailing south-west from Hawai'i, he made a ‘new discovery’ and memorialized it as ‘New Year's Island’. He later learned that the Islanders called it Miadi (Mejit Island).Footnote 35 A subsequent French global atlas gives the island the dual appellation Miadi ou de la nouvelle année (Miadi or New Year (Island)).Footnote 36 Russian naming of the ‘Group of Count Rumiantsev’ (Wotje Atoll) was more convoluted. This large atoll in the central Ratak Chain was the axis of Kotzebue's interactions with Islanders during a month-long stay. He dedicated this major ‘discovery’ to diplomatic commemoration, calling the atoll collectively after the expedition's influential sponsor Nikolai Petrovich Rumiantsev.Footnote 37 Conversely, he modified his naming practice with respect to individual islands in accord with experience and his developing relations with the inhabitants. Entering the large inner lagoon through the south-western passage, Kotzebue initially used banal descriptive names for two uninhabited islands: Kozii (Goat) Island, where he left goats for local use, and Ptichii (Bird) Island. The ship's anchorage near Goat Island was named Christmas Harbour – the date it was first seen according to the Russian calendar.Footnote 38 As he sailed to the eastern, more densely populated part of the atoll and learned words of the Indigenous language, Kotzebue's nomenclature reflected his emerging grasp of local usage and celebrated Islanders’ conduct: he noted the island names Ormed (Wormej), Otdia (Wotje), and Egmedio (Bodao) and called the whole north-eastern group the Islands of Friendly Reception because the inhabitants were peaceful and hospitable towards the foreigners.Footnote 39 Though informed that ‘Otdia’ was the Indigenous name for the ‘whole island group’, he nonetheless retained the honorific ‘Romanzoff’ (Rumiantsev) as the atoll's formal umbrella designation (Figure 4).Footnote 40

Fig. 4. Otto Kotsebu, ‘Ploskaia karta gruppy koral'nykh ostrovov grafa Rumiantsova’ (Flat map of the Rumiantsev Group of coral islands) (1817), in Atlas k puteshestviiu…na korable Riurike v Iuzhnoe more i v Beringov proliv (Atlas of the voyage…on the ship Riurik to the South Sea and Bering Strait), plate [12], Estonian Historical Archives, National Archives of Estonia, Tartu, EAA.1414.2.36.13

The key to Kotzebue's growing familiarity with Indigenous geographical knowledge, both at Wotje and elsewhere in the central Pacific, was his meeting and developing friendship with Islanders, notably Lagediack and Kadu. In different ways, both men fit the category of Indigenous ‘intermediaries’ or ‘brokers’, identified in recent scholarship as shadowy but potent co-producers of knowledge with European travellers or colonizers.Footnote 41 Kotzebue met his ‘friend and teacher’ Lagediack at Wotje Island and found him adept in teaching local words. Once Lagediack understood that Kotzebue was interested in the location of other atolls, he ‘took a pencil’ and drew maps of Wotje Atoll and a nearby group of islands on the ship's azimuth tables. Quickly grasping the principle of the azimuth compass, he used it to indicate the direction of two reef passages unknown to Kotzebue, who named one after his instructor. Lagediack later ‘invented a very clever method’ for a geography lesson, using a sand map and different sized stones to show Kotzebue the position of other named atolls in the Ratak Chain. Lagediack's accurate directions and distances helped Kotzebue to make and identify several subsequent ‘discoveries’.Footnote 42 Another Islander at a nearby atoll later redrew Kotzebue's sand map to modify and extend the information he had received from Lagediack. Kotzebue ‘accurately copied’ this map in his notebook and found it ‘very correct’.Footnote 43 At yet another atoll, a ‘venerable old man’ named as Langemui used ‘a mat spread out, with the assistance of small stones’, to demonstrate the relationship of the Ratak and Rālik Chains. Kotzebue subsequently drew his own chart of the Rālik Chain (Figure 3) ‘according to’ this man's information, hoping that it would be ‘pretty correct’.Footnote 44

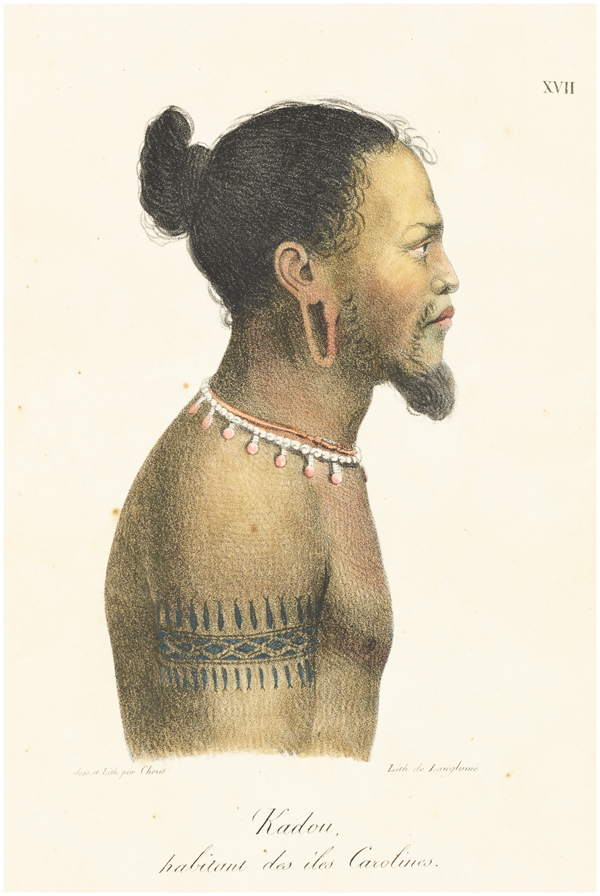

Lagediack, as resident expert in Wotje, materialized on paper and in sand his empirical and inherited knowledge of the relative position of his own and surrounding islands.Footnote 45 Kadu (Figure 5), in contrast, was an ongoing embodied presence as travelling companion aboard the Riurik during an eight-month cruise in 1817 from the Ratak Chain to Bering Strait, Hawai'i, and back to Wotje. He was thus one of a handful of named Islanders who joined European scientific expeditions, were variously acknowledged by voyagers as contributors of local knowledge, and have achieved some prominence in recent Pacific historiography. If Tupaia is now by far the most celebrated such traveller,Footnote 46 they also include the Tahitian Ahutoru, the Ra‘iātean Ma‘i, and the Bora Boran Mahine.Footnote 47 Originally from Woleai in the Caroline Islands and widely travelled across that archipelago, Kadu had reached Aur Atoll, south-east of Wotje, with his friend Edock after spending several months adrift in a canoe following a storm. Kadu insisted on joining the Riurik, despite Edock's opposition.Footnote 48 According to the artist Choris, he made himself ‘loved by the officers and esteemed by the sailors’.Footnote 49 He supplied Chamisso with much geographical, ethnographic, and linguistic information, particularly about the Caroline Islands.Footnote 50

Fig. 5. Louis Choris, ‘Kadou, habitant des îles Carolines’ (1822), lithograph, in Voyage pittoresque autour du monde…, plate 17, National Library of Australia, Canberra, PIC Volume 590 #S6736, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136173698

Like most experienced scientific voyagers, Kotzebue's toponymic practice ranged between the twin poles of duty and personal experience, mediated by the pragmatic necessity to acknowledge superiors, sponsors, and colleagues, by professional amour-propre or ambition, by relative familiarity with specific places, and by the impact of situated encounters with Indigenous people. In the Ratak Chain, Kotzebue reserved celebratory labels for higher level geographical features such as a group of islands.Footnote 51 In contrast, his recorded names for particular islands depend mainly on the nature and extent of his acquaintance with places and their inhabitants. Proximity during a two-months’ stay in and around Wotje transformed anonymous ‘savages’, fleetingly encountered, into well-informed named persons, whose interest and capacity to convey their expertise enabled Kotzebue to absorb, process, and map local geographical wisdom. Similarly, the even greater intimacy and burgeoning mutual comprehension in Russian and Woleaian established with ‘our friend and instructor’ Kadu during a long sea voyage enabled Chamisso to amass much precise geographical information, rooted in the Islander's extensive travels in and beyond the Carolines.Footnote 52 The naturalist expressed admiration for the ‘seamen of these islands’, whose ‘navigation embraces a space…which is almost the greatest breadth of the Atlantic Ocean’.Footnote 53 Reinforced by conversations with Edock in Aur and a knowledgeable Spaniard in Guam,Footnote 54 the intellectual bounty of this astonishing maritime expertise was manifested in the commander's then authoritative maps of the Carolines (Figure 6), an archipelago he had never seen.Footnote 55

Fig. 6. Otto von Kotzebue, ‘Chart of the Caroline Islands, after the statement of Edock’ (1821), in A voyage of discovery into the South Sea and Beering's Straits, for the purpose of exploring a North-east Passage undertaken in the years 1815–1818…in the ship Rurick…, ii, endmap, National Library of Australia, Canberra, NK 921

IV

At this point, we digress to consider the uneven incorporation of elements of Kotzebue's experience in Krusenstern's scholarly synthesis. The Russian edition of his seminal South Sea atlas includes detailed geographical information about the Ratak Chain. The map of the Marshall Islands, published in 1826, features many of the local names carefully conveyed to Kotzebue by Indigenous interlocutors in 1817.Footnote 56 This display of confident empirical expertise no doubt flattered the national pride of a domestic audience.

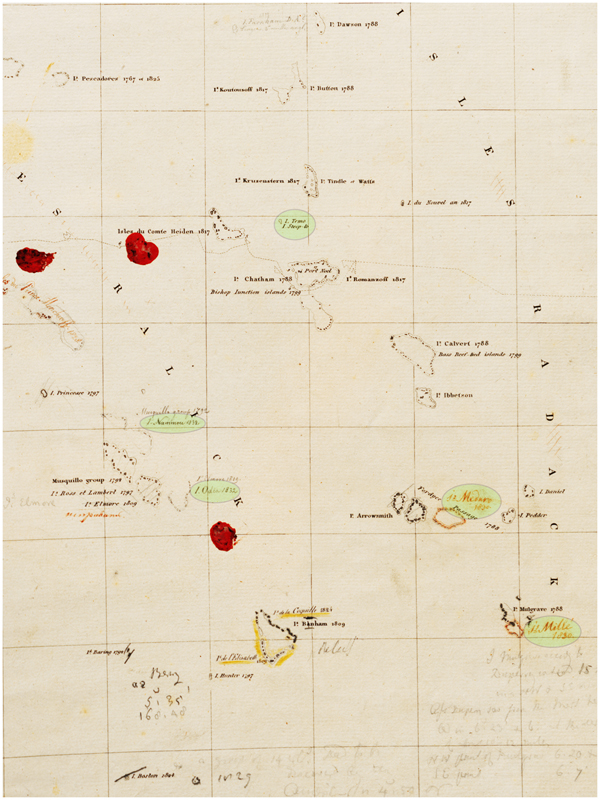

The following year, another version of the map was printed in the atlas's French edition and dedicated to Kotzebue.Footnote 57 While atolls, islands, and their co-ordinates are similar, the French nomenclature is strikingly different. Inscribing a history of European ‘discovery’ to 1825, every island name memorializes a European voyage, usually with a date of passage. The map registers several of Kotzebue's tributes to Russian eponyms, including Krusenstern himself. Only one Indigenous name, derived from Kotzebue, is printed as an alternative to a European toponym. Krusenstern handwrote radical amendments to this map in his personal copy of the French atlas, held in the National Archives of Estonia. They include two of Kotzebue's local island names in the Ratak Chain and another two in the Rālik Chain learned by a Russian voyager in 1832 (Figure 7).Footnote 58 However, none of these addendums features in Krusenstern's re-engraved version of the ‘Map of the Archipelago of the Marshall Islands’ published in 1835.Footnote 59

Fig. 7. Adam Johann von Krusenstern, ‘Carte de l'Archipel des îles Marshall’ (1827), annotated by author in pencil and red ink, detail, in Atlas de l'océan pacifique, ii, plate 33, Estonian Historical Archives, National Archives of Estonia, Tartu, EAA.1414.2.40.36

As a showcase for its author's cosmopolitan credentials, Krusenstern's French atlas is positioned within an urbane ‘civilized’ discourse which allowed little space for the words or works of ‘savages’. This stance was verbalized by Krusenstern in ‘supplements’ to his hydrographic memoirs, published in 1835 together with revised maps from the atlas. Notwithstanding his shipmates’ painstaking efforts to record Indigenous place names in Nuku Hiva, or his own careful rehearsal of Kotzebue's local toponyms in both the Russian map of the Marshall Islands and the French edition of the memoirs,Footnote 60 Krusenstern here rejected their global usage. He expatiated on the ‘advantages’ of the European names given by navigators to ‘their discoveries’, expressed ‘little confidence’ in the ‘information provided by the Islanders’, and complained of the ‘difficult pronunciation’ of Indigenous names.Footnote 61

Krusenstern's wide multilingual scholarship in the service of metropolitan, mainly hydrographic, priorities is encapsulated in his map and parallel memoir of the ‘Low Islands’ (Tuamotu Archipelago) – Johann Reinhold Forster's descriptive name for this far-flung atoll chain.Footnote 62 The map's many, meticulously located, islands are inscribed with names and dates marking their European ‘discovery’.Footnote 63 The memoir exhaustively summarizes, identifies, and sets co-ordinates for the deeply uncertain results of three centuries of European voyaging through the archipelago, culminating in the recent passages of Krusenstern's compatriots Kotzebue in 1816 and Bellingshausen in 1820.Footnote 64 Both map and memoir are almost devoid of Indigenous presence.

V

By Krusenstern's calculation, Bellingshausen ‘enriched’ the Low Islands with ‘11 new discoveries’ during his circumnavigation of the globe on the Vostok accompanied by the Mirnyi, captained by Mikhail Lazarev.Footnote 65 However, unlike Kotzebue in the Marshalls, Bellingshausen had little opportunity to garner Indigenous geographical information while actually traversing the Tuamotus. Unable to land at any inhabited island due to reefs, weather, or Indigenous hostility – the power of place or people – Bellingshausen learned only one local place name in situ.Footnote 66 His toponymy acknowledges an array of eponymous Russian dignitaries and senior army or naval officers.Footnote 67 The exception is the local name of an intermittently occupied island where, on 13 July 1820, the expedition encountered three Islanders in a canoe. These two men and a woman engaged in friendly exchange and were sketched by the onboard artist Mikhailov (Figure 8).Footnote 68 Materializing this rare access to embodied local knowledge, Bellingshausen recorded the name of the leader of the group as Eri-Tatano and that of the island as Nigiru (Nihiru), because it was called thus by ‘our visitors’.Footnote 69 Krusenstern rendered it as Nigeri, one of only two Indigenous names marked on his map or included in his ‘Table’ of the Low Islands.Footnote 70

Fig. 8. Pavel Nikolaevich Mikhailov, ‘Zhiteli s koral'nogo ostrova Nigiru’ (Inhabitants from the coral island Nigiru) (n.d.), lithograph, Prints Department, National Library of Russia, St Petersburg

Bellingshausen's final landfall in the Tuamotus was at Makatea, a sporadically visited raised coral atoll about 240 km north-east of Tahiti. Here, the expedition picked up four young Islanders, survivors from a party of ten blown off course to Makatea and subsequently attacked by people from another island, who allegedly killed and ate all but the four boys. The eldest told Bellingshausen that their own island was called ‘Anna’ (Anaa). Asked its direction, the boy first enquired where Tahiti lay and then pointed insistently to the south-east, ‘in the direction of Chains Island’, so named by Cook in 1769. At this point, Bellingshausen spurned the boy's advice, preferring the authority of Arrowsmith's chart which locates ‘Oanna’ north-east of ‘Recreation’ (probably Makatea).Footnote 71

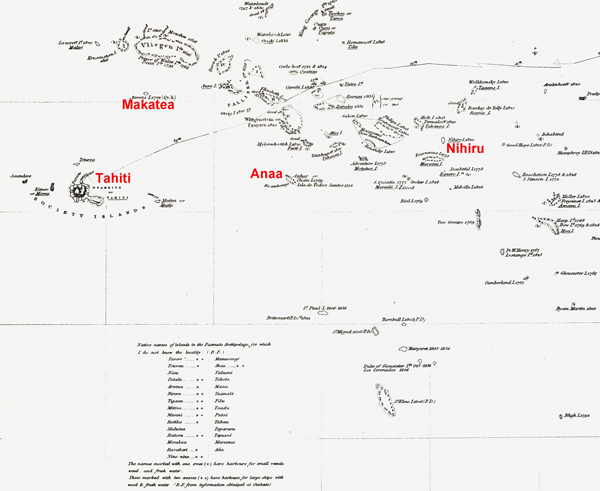

Following his own passage through the north-west quadrant of the Low Islands in HMS Beagle in 1835, the English navigator FitzRoy reprinted Krusenstern's updated map of 1837, ‘with additions’ (Figure 9).Footnote 72 In the narrative of his voyage, FitzRoy praised Krusenstern's ‘excellent chart’ and ‘elaborate memoir’ as ‘the only documents of any use to us while traversing the archipelago’.Footnote 73 However, his major addendums to the map comprise more than twenty underlined Indigenous place names, some freestanding (including ‘Nihiro I. 1820’) and others printed with European appellations (including ‘Anhar or Chain I. 1769’, more than 400 km east of Tahiti and thus indeed south-east of Makatea). A legend on FitzRoy's map lists an additional twenty-nine ‘Native names of islands’, for which he did ‘not know the locality’, attributed to ‘information obtained at Otaheite [Tahiti]’.Footnote 74

Fig. 9. Robert FitzRoy, ‘Dangerous Archipelago of the Paamuto or Low Islands by Admiral Krusenstern 1837’ (1838), detail, National Library of Australia, Canberra, -http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232746157

Shortly after passing through the Tuamotus in July 1820, Bellingshausen himself spent a week in Tahiti where, like FitzRoy, he actively sought local knowledge about the archipelago. A resident American sailor with some knowledge of Russian served as his interpreter.Footnote 75 Bellingshausen began to admit the validity of Indigenous geographical knowledge when the boy from Anaa pointed out the identity of his own body tattoos with those of one of his ‘countrymen’, persuading Bellingshausen that both came from the same island. These figures also resembled the markings he had seen at Nihiru Island on the thighs of Eri-Tatano (Figure 8), whom he concluded must also be from Anaa. Bellingshausen eventually resolved the conundrum of Anaa's location – and fully acknowledged Indigenous expertise – in further conversation with men from that island met in Tahiti, whose ‘intrepid seafaring’ he lauded. They ‘laughed’ at his assertion, following Arrowsmith, that Anaa was north of Tahiti and supplied him with convincing ‘proof’ of its identity with Chain Island.Footnote 76 The second Indigenous toponym in Krusenstern's map and table of the Tuamotus is ‘Matia’ (Makatea), presumably following Bellingshausen. However, Krusenstern failed to make the link between Chain Island and Anaa, neither in his memoir supplement nor in the re-engraved ‘Map of the Archipelago of the Low Islands’, which he revised after the publication of Bellingshausen's narrative.Footnote 77

VI

Further variations on the voyagers’ Pacific place-naming continuum from obligation to experience are manifest in the cartographic production of Lütke, who circumnavigated the globe on the Senyavin in 1826–9. During two cruises from Kamchatka in 1827–8, Lütke surveyed sectors of the Caroline Islands little known to Europeans.Footnote 78 He claimed to have ‘reconnoitred twenty-six groups or separate islands, of which ten or twelve are new discoveries’.Footnote 79

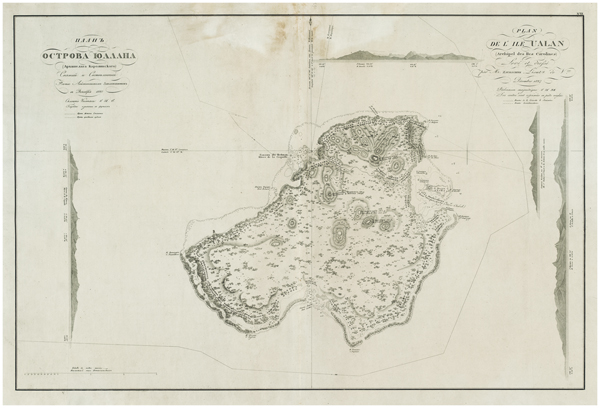

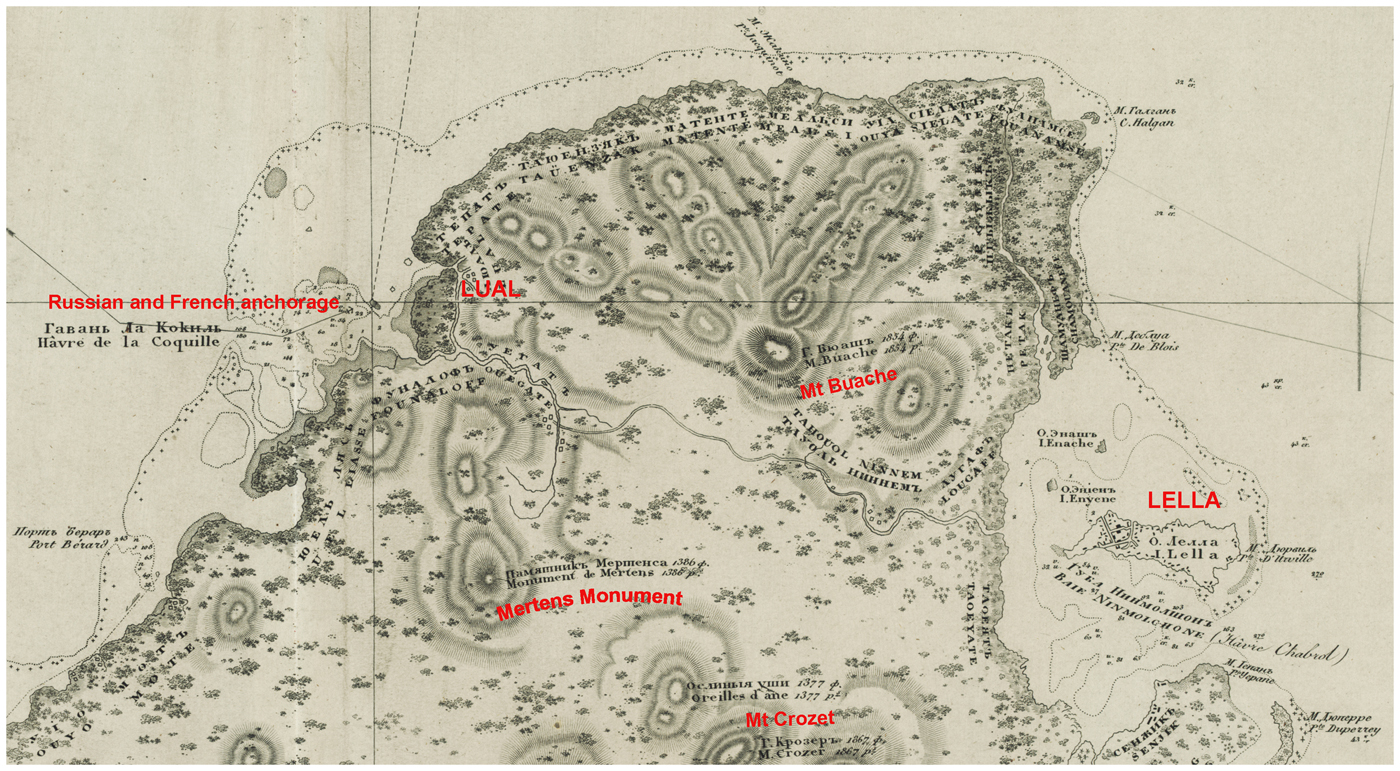

In late 1827, the expedition spent three weeks at the ‘interesting’ high island of Ualan (Kosrae). Lütke and his men were enchanted by the conduct of the ‘good and friendly inhabitants’ – as were the members of Duperrey's French expedition, who had stayed for ten days in June 1824 and believed they were the first Europeans to land there.Footnote 80 Lütke's nautical atlas of the voyage, printed with twin Russian and French cartouches, captions, and place names, includes a detailed map of ‘Ualan’ (Figures 10, 10a).Footnote 81 His toponyms and related debts or challenges to his predecessors are mixed. As the ship approached the island, local people – including at least one high-ranking ‘chief’ – came out in canoes. They tried to direct the visitors to the east coast, ‘repeating lella, lella’. When Lütke, like Duperrey, headed instead for an anchorage in the island's north-west, the Islanders reiterated ‘incessantly’ that this was ‘Ualan’.Footnote 82 Like the French,Footnote 83 Lütke took the word to be the island's name, disputing only their transliteration ‘Oualan’.Footnote 84 Both sets of Europeans described a small island off the north-east coast as ‘the common residence of the principal chiefs’. The French recorded its name as Lélé but Lütke heard the word rather as Lella (Lelu or Leluh). All were astounded by the massive coral sea walls enveloping Lelu, its extensive canal system, and its monumental architecture featuring huge basalt megaliths – centuries-old material productions in a profoundly stratified social system, only dimly evident to the visitors.Footnote 85 A modern doctoral thesis explains that Ualan ‘is not strictly the name of the big island’, but means ‘“away from Lelu”’.Footnote 86 The voyagers evidently mistook an Indigenous instruction to go directly to the seat of governing authority for an insular toponym.

Fig. 10. Fedor Litke, ‘Plan ostrova Yualana (Arkhipelaga Karolinskogo)/Plan de l’île Ualan (Archipel des Iles Carolines)’ ([1836]), in Atlas k puteshestviiu vokrug sveta shliupa Seniavina…v 1826, 1827 i 1829 godakh/Atlas du voyage autour du monde de la corvette Séniavine fait en 1826, 1827, 1828 et 1829, plate 20, National Library of Australia, Canberra, MAP Rm 3109/2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232183389

Fig. 10a. Fedor Litke, [northern part of Ualan (Kosrae)], in ‘Plan ostrova Yualana (Arkhipelaga Karolinskogo)/Plan de l’île Ualan (Archipel des Iles Carolines)’ ([1836]), National Library of Australia, Canberra, MAP Rm 3109/2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232183389

Lütke's map retains Duperrey's French eponyms – mostly honouring his shipmates – for Kosrae's two main peaks and prominent coastal features.Footnote 87 Lütke printed them in lower case with Russian translations superposed. In retrospective eponymy, he called another peak ‘Mertens Monument’ in memory of the expedition's naturalist, who died after his return to Russia.Footnote 88 In contrast, the littoral of the island is garlanded with Indigenous names of districts, printed in upper case, phonetically French, with Russian transcription. As in Wotje, these place names render local geographical knowledge conveyed to a visiting navigator by an Indigenous ‘friend’ – in this case, Kaki, an ‘old chief’ of the settlement of Lual (Lacl), opposite the Russian anchorage, who dictated to Lütke a ‘detailed’ list of the island's ‘village’ and ‘district’ names, together with those of the ‘chiefs to whom they belonged’. These names are doubly materialized in schema and cartography: in a table in Lütke's narrative and around the island's circumference on the map. They are concentrated along the north coast which Lütke traversed on foot en route to and from Lelu, accompanied by Kaki (Figure 10a).Footnote 89

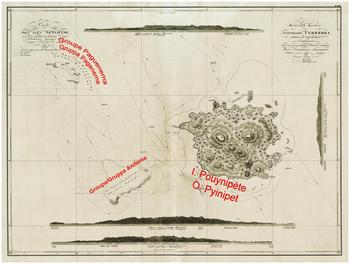

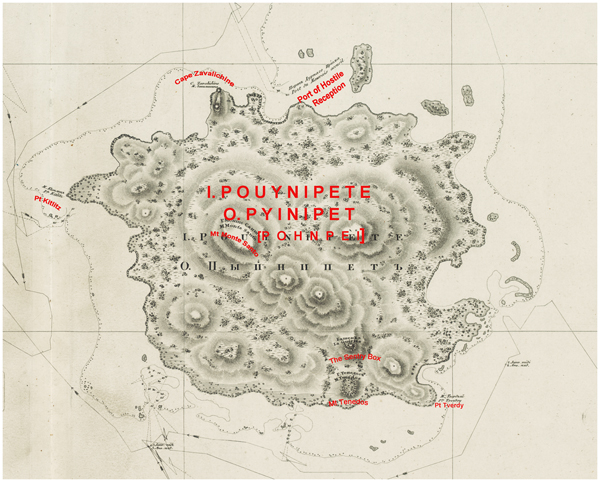

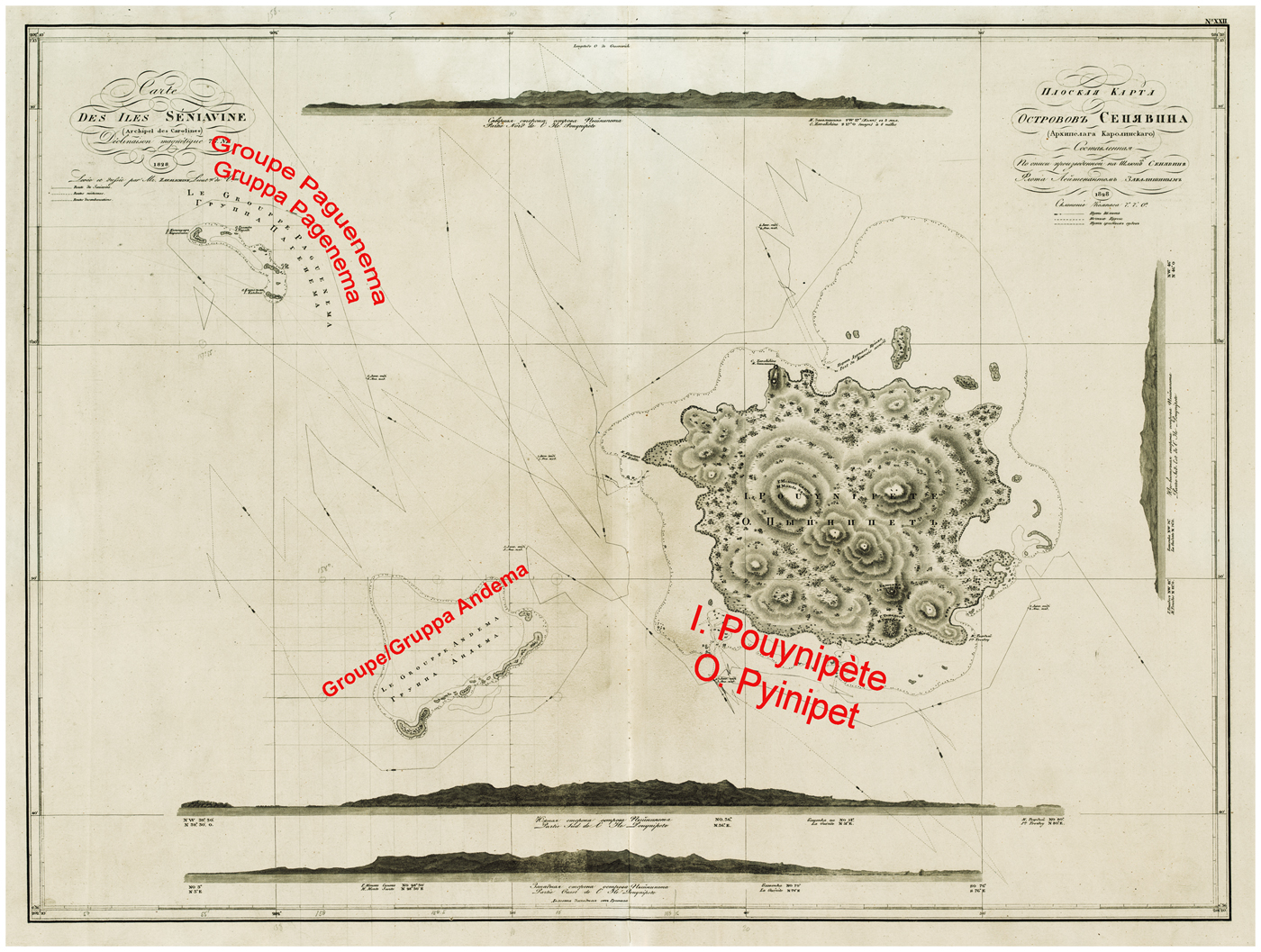

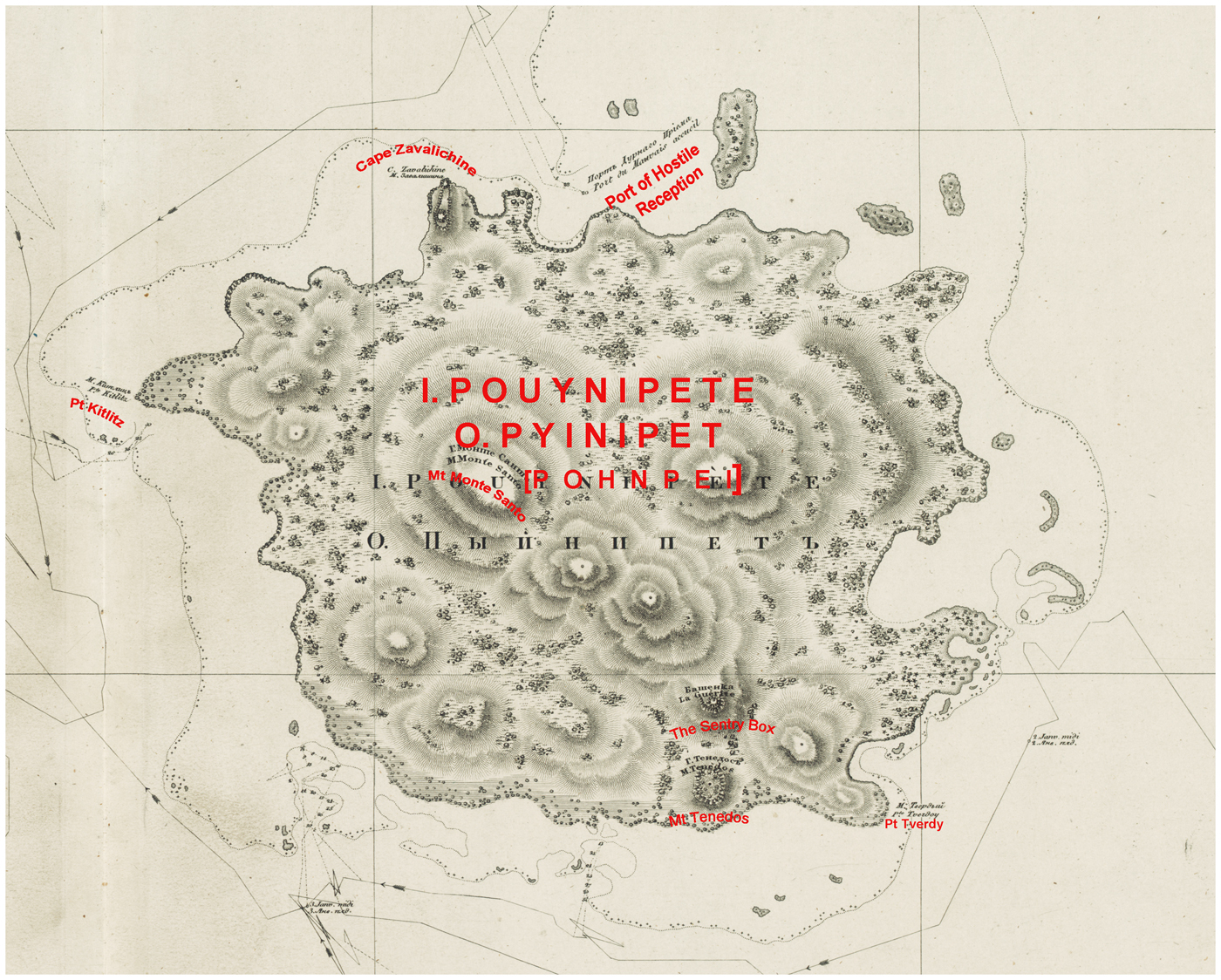

The ‘unparalleled hospitality of this good and amiable people’ left the Russians quite unprepared for their very different reception ten days later at the high island of Pohnpei, 550 km north-west of Kosrae (Figures 11, 11a).Footnote 90 Lütke's humanist good intentions were repeatedly frustrated by the behaviour of these Islanders, whose ‘din’, ‘turbulence’, and ‘savage physiognomies’ contrasted so disagreeably with ‘the mild and decent manners of our friends in Ualan’. During an initial encounter at sea with ‘about forty canoes’, Lütke was scratched on the hand when a ‘savage’ tried to seize his sextant. On two further occasions, crowds of Islanders in canoes so threatened Russian efforts to reconnoitre potential anchorages that they had to retreat. One man threw a small spear at the launch commander who retaliated with a shot over the Islander's head. The assailants, momentarily disconcerted, allowed the boat to escape unscathed to the ship. Refusing to resort to firearms except ‘in the last extremity’, Lütke openly acknowledged how his options were controlled by Indigenous agency. He recognized that ‘these turbulent islanders’ might not have had ‘hostile intentions’, but been motivated merely by ‘curiosity’, desire for ‘extraordinary objects’, or trepidation. But he also admitted that ‘their conduct was such…that we could not even manage the search for an anchorage’ in the time available. He thus regretfully abandoned the attempt to land on Pohnpei, ‘renouncing the pleasure of setting foot on the land that we had just discovered’.Footnote 91

Fig. 11. Fedor Litke, ‘Ploskaia karta ostrovov Seniavina (Arkhipelaga Karolinskogo)/Carte des îles Séniavine (Archipel des îles Carolines)’ ([1836]), in Atlas k puteshestviiu vokrug sveta shliupa Seniavina…v 1826, 1827 i 1829 godakh/Atlas du voyage autour du monde de la corvette Séniavine fait en 1826, 1827, 1828 et 1829, plate 22, National Library of Australia, Canberra, MAP Rm 3109/4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232183600

Fig. 11a. Fedor Litke, [O. Pyinipet/I. Pouynipete (Pohnpei)], in ‘Ploskaia karta ostrovov Seniavina (Arkhipelaga Karolinskogo)/Carte des îles Séniavine (Archipel des Iles Carolines)’, ([1836]), detail, National Library of Australia, Canberra, MAP Rm 3109/4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232183600

Lütke's reluctance to make the Islanders ‘feel the power of firearms’ left him only symbolic recourse to punish the insults and apprehension suffered by the Russians in Pohnpei. His figurative vengeance for the ‘turbulent character’ and unpredictable actions of Pohnpeians was expressed in directly toponymic and more insidious racial terms. In exasperated response to disapproved local actions, he inflicted the name ‘Port of Hostile Reception’ on the second bay where the launch was repelled (Figure 11a), surely a negative echo of Kotzebue's ‘Islands of Friendly Reception’ in Wotje.Footnote 92

Lütke exacted indirect symbolic revenge by racial denigration. He deplored the Pohnpeians’ speech as ‘rude’, ‘strange and savage’ and averred that, since they differed ‘strikingly’ in external appearance from Kosraeans or other Caroline Islanders, they must belong to ‘another race of men’. He chose to identify them with ‘the race of the Papuans’ – the inhabitants of New Guinea and nearby islands – and further surmised that their ‘true’ place of origin might be New Ireland.Footnote 93 Douglas has elsewhere identified a rhetorical correlation between European travellers’ relief at approved Indigenous conduct and their positive depictions of the physical appearance and character of such people, who are distanced from the adverse stereotype of ‘the Negro’ of Africa. Lütke's bitter experience of Pohnpeians’ behaviour saw him invert that rhetorical sequence by maligning their speech and demeanour and aligning them physically with an Oceanic ‘race’ – ‘the Papuans’ – which was often labelled Negro or Negro-like. He thus attributed to Pohnpeians a conventional set of physical characters evocative of that reviled stereotype, with implied moral corollaries: ‘the large, flat face, the large, flattened nose, the thick lips, the frizzy hair in some cases; [and] great bulging eyes, expressing mistrust and ferocity’.Footnote 94

In other respects, Lütke's toponymy of Pohnpei followed familiar Russian practice for places where Indigenous names were largely unknown. He called the island group as a whole the Senyavin Islands, memorializing his own ship and its eponym, the Russian admiral Dmitry Senyavin who had defeated the Turks in 1807. Freed by ignorance of local usage to follow duty or fancy when charting the coasts of Pohnpei Island itself, Lütke conferred the descriptor Bashenka (La Guérite, Sentry Box) on ‘an isolated and very distinct mass of basalt’, bestowed Aegean toponyms associated with Senyavin's victories on two mountains, and named Point Tverdy (hard, resilient) in honour of Senyavin's ship. Further eponymic impositions celebrated Lütke's own lieutenant Zavalishin and their shipmate Kittlitz, a retired Prussian naval officer-naturalist who accompanied the expedition.Footnote 95

Notwithstanding these eclectic choices, Lütke's over-riding toponymic concern in this group was to know ‘the name that the natives give to the large island’. He thought it was probably ‘Pouynipète’, an opinion confirmed during a brief shipside encounter with several men ‘of the common sort’, who seemed ‘more reserved and more intelligent than the others’. They also taught him local names for the two small atolls and their constituent islands which complete the Senyavin group. Lütke duly inscribed Pouynipète/Pyinipet (Pohnpei), Andema (And or Ant), Paguenema/Pagenema (Pakin), and several islands within Pakin, as the only Indigenous names on his ‘Map of the Senyavin Islands’ (Figure 11). His faith in the accuracy of the term Pouynipète was further licensed by comparison with homophones in Kotzebue's maps of the Caroline Islands (Figure 6) and others heard subsequently at islands elsewhere in the archipelago.Footnote 96

In sharp contrast to Krusenstern, Lütke professed the firm principle that ‘the names the natives give to the places they inhabit, are necessary for the systematic description of a country’. This was especially so in far-flung groups of tiny islands like the Carolines, where several centuries of erratic European ‘discovery’, mislocation, and idiosyncratic naming had created geographic ‘chaos’.Footnote 97 Whereas Krusenstern relied on static knowledge of Pacific geography acquired from European voyage narratives, Kotzebue in the Marshalls and particularly Lütke in the Carolines engaged in active, in situ learning from Indigenous experts, who taught them local toponyms and sailing directions for particular islands and atolls. The precise co-ordinates and systematic nomenclature in Lütke's ‘General map of the Carolines Archipelago’ testify not only to his hydrographic expertise,Footnote 98 but to the efficacy of his collaboration in situ with at least ten named and several unnamed Indigenous navigator counterparts.Footnote 99 He deemed earlier European cartography of the Carolines by Cantova, Chamisso, Freycinet, and Duperrey as being ‘not of great use for geography’ or ‘imperfect’. However, they provided ‘bearings’ in relation to his own work and:

especially to the information gathered gradually from islanders in several places, which helped guide our navigation so as to leave the fewest possible islands undetermined. Thus the geographic knowledge of the Caroline islanders, insufficient for science, if extended for savages, which had produced such great confusion in the maps, served to enlighten itself.Footnote 100

Lütke paid sincere tribute to the skill of these men and the ‘accuracy’ of their knowledge of the relative position of islands in the archipelago, even if their (to him) ‘vague’ grasp of distance made ‘their verbal information’ far more useful than the maps they drew at European behest. Beyond empirical toponymy, he made an effort to grasp Indigenous epistemology. He perceptively contrasted the embodied expertise of Carolinian navigators, reliant on ‘memory and traditions’, with the ‘mechanical methods’ which made European navigators dependent on material instruments and maps: ‘in their eyes these lines [traced on paper or sand] serve only as support to memory; they are for us the main thing, and it is through them that we confirm our memory’.Footnote 101

Krusenstern's hydrographic supplement ambivalently acknowledges the ‘judicious system’ whereby Lütke established the geographical position of most of the individual groups and islands comprising the Carolines. However, Krusenstern was clearly unimpressed by his compatriot's careful assemblage of local place names. This text, together with Krusenstern's three radically revised maps of ‘the Archipelago of the Caroline Islands’ in the second edition of his atlas, only allows Lütke's Indigenous names as the primary designations for places classed by Krusenstern as Lütke's personal discoveries. Otherwise, earlier European nomenclature is privileged over local toponyms, which are mostly downgraded as Lütke's own bestowals. In the case of Ulithi Atoll, Krusenstern explicitly rejected Ouluthy – Lütke's rendition of the Islanders’ ‘general name’ for the group – in favour of conserving ‘that of the Navigator who discovered them’, a passing British sea captain who had no contact with the inhabitants and no idea what he had ‘discovered’.Footnote 102

VII

A key theme of this history of early nineteenth-century Russian place naming in the Pacific Islands is the relative salience of Indigenous agency and local knowledge. To this end, we have systematically sampled toponymic and cartographic implications of encounters between Russian scientific voyagers and specific people and places in the insular Pacific. The Russians’ default position – as for European voyagers generally – was the easy option of eponymy, with its benefits of flattering masters or sponsors or rewarding subordinates.Footnote 103 Except in Lütke's work on the Carolines, eponymy reigned supreme at the metalevel of atoll, island group, or archipelago, complicated by the relative distance between encounter and inscription – particularly between voyage charts or atlases and Krusenstern's synthesizing regional atlas.

The individual preferences or idiosyncrasies of particular voyagers clearly affected their naming strategies. Krusenstern, preoccupied with managing his ship, his expedition, and his fraught relations with Rezanov, forged few, if any, intimate bonds with Marquesans, did not value Indigenous expertise, and discounted local knowledge on principle. In contrast, his naturalists and junior officers spent much time ashore, acquired Marquesan ‘friends’, and sought nominal tokens of having been there. None of the protégés and successors of Krusenstern discussed in this article shared his expressed aversion to Indigenous place names. Indeed, challenging experience as maritime explorers in remote Pacific archipelagoes convinced them, to varying degrees, of the taxonomic importance of local names and all sought to know them when they could – though never questioning the intellectual or practical superiority of European science and technology. Kotzebue learned to appreciate local knowledge in situ in the Marshalls, under the influence of Chamisso and their close encounters with resident experts. Bellingshausen dabbled with its acquisition in and of the Tuamotus, but had limited opportunity and moderate conviction. Only Lütke in the Carolines appreciated the profound significance of Indigenous empirical wisdom and sought methodically to tap and record it.

Personality, prejudice, ethnocentrism, and circumstance aside, the insular toponymies of European voyagers in Oceania were generated in contexts of human encounters or their absence. Two conditions consistently shaped the nexus of encounter and nomenclature: the conduct and demeanour of populations met in situ; and the extent of embodied emotional connection established between particular Indigenous interlocutors and visitors. In these Russian cases, the impacts of Indigenous agency are doubly materialized: in the affective load embedded in particular names (as in ‘Friendly’ or ‘Hostile Reception’ in Wotje and Pohnpei); and in the relative extent of local toponymic knowledge registered in voyagers’ charts, maps, journals, and narratives.

In an ocean now largely anglophone or francophone in terms of global communication, the significance of early nineteenth-century Russian voyaging is often inadequately known or appreciated. Yet successive Russian voyages in the eastern and northern Pacific Islands before 1830 left important legacies in natural history and ethnography, as well as the signal achievements in hydrography and cartography discussed here. All but Bellingshausen's expedition were accompanied by distinguished naturalists who made considerable contributions to recording Pacific flora, fauna, and geology: Langsdorff and Tilesius sailed with Krusenstern; Chamisso and Eschscholtz with Kotzebue; and Mertens, Postels, and Kittlitz with Lütke. Some of their published works were widely disseminated in translations.Footnote 104 Chamisso, informed by Kadu, wrote useful ethnographic descriptions of the Marshall and Caroline Islands, while his ethnological and linguistic reflections on ‘the Great Ocean’ earned justified respect from his peers.Footnote 105 Lütke's description of Lelu and his ethnographic impressions of Kosrae's complex social hierarchy remain an invaluable resource for modern Kosraeans seeking to understand their vanished ancestral world.Footnote 106

Russian navigators transformed global knowing of the Tuamotu, Marshall, and Caroline archipelagoes by surveying, charting, and naming most of the constituent atolls and islands. The towering scholarship of Krusenstern's atlas was respectfully acknowledged by fellow navigators and remained an important resource for cartographers for much of the nineteenth century.Footnote 107 He inspired, guided, and influenced his compatriots whose empirical work – often produced in collaboration with Indigenous interlocutors unrecognized by Krusenstern – provided important building blocks for his syntheses of the cartography and hydrography of these island chains.