Identifying and locating unknown individuals accused of criminal acts has always been central to police practice. When a crime is reported, police officers work with witnesses to produce descriptions of suspects. This basic aspect of policing has remained unchanged for centuries, but there have been considerable refinements in technique. While prose descriptions were initially the norm, towards the end of the nineteenth century some police forces began to work with artists to produce visual representations of suspects. During the twentieth century, increasingly complex technologies of identification were developed and deployed. This article analyses the development, adoption, and early implementation of arguably the most influential: the Photo-FIT system (a facial composite tool adopted by the British police in 1970 to produce realistic ‘wanted’ posters).

Launched at a lavish press reception at the Savoy Hotel in London, Photo-FIT was the result of an unlikely collaboration between the Home Office, an unconventional inventor (the ‘facial topographer’ Jacques Penry), and the board game manufacturer John Waddington Ltd (which subsequently produced Photo-FIT under licence). The new system was rapidly adopted by all police forces across Britain and spread quickly around the world, with 650 kits sold (by 1974) to twenty-three countries as far afield as the USA, Brazil, Australia, and Nigeria.Footnote 1 Seemingly immediately successful, Photo-FIT was in use for decades and spawned a range of successor technologies still in use today (such as E-FIT and EFIT-V), along with a whole sub-field of psychology focused on facial recognition.Footnote 2

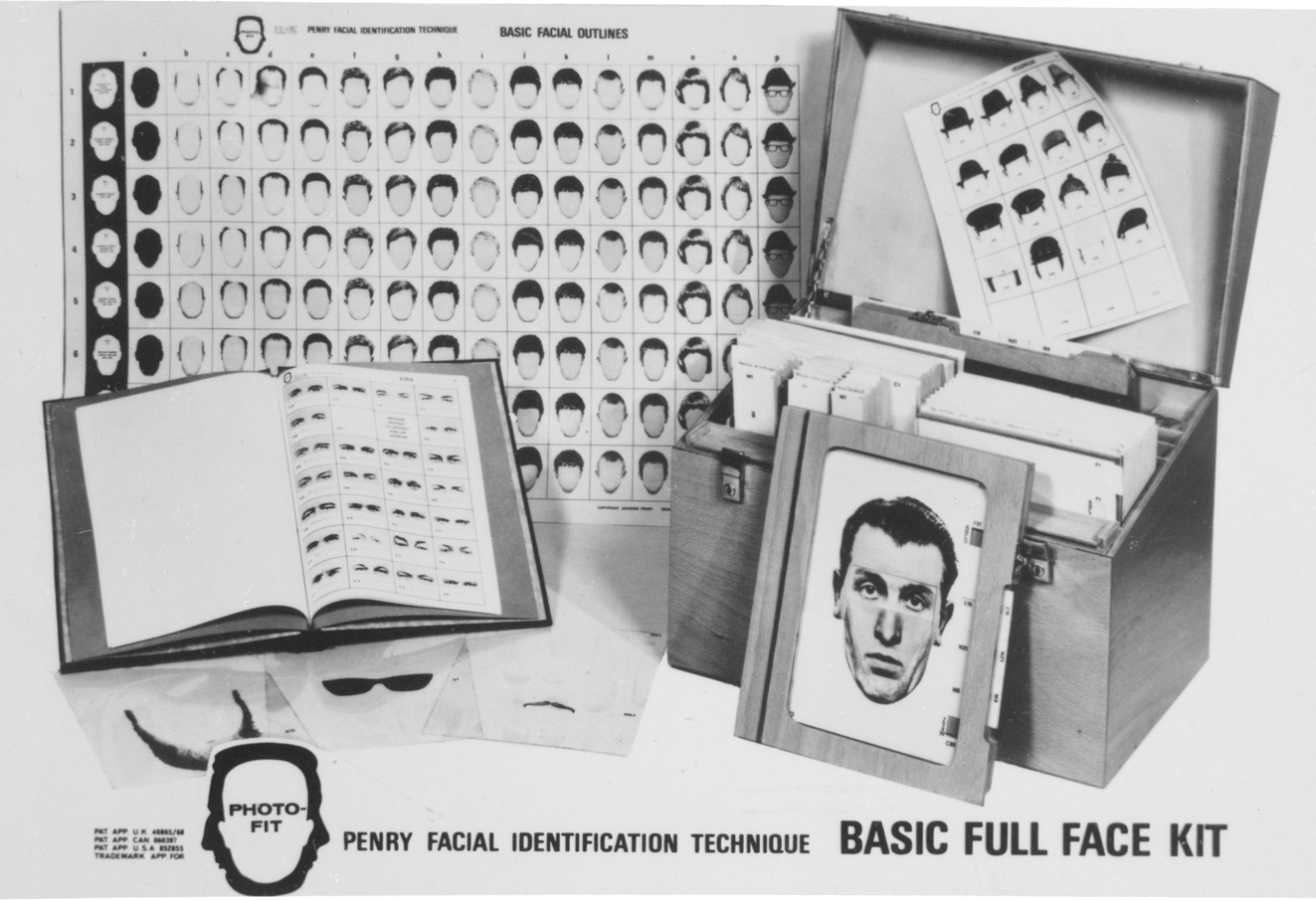

At first glance, then, the development of Photo-FIT during the later 1960s accords with a stereotypical narrative of the period as one in which the ‘white heat’ of science and technology was modernizing and transforming Britain.Footnote 3 Certainly, Photo-FIT was developed under the auspices of the Home Office's Police Scientific Development Branch (PSDB), specifically set up in 1963 so that scientists and police officers might collaborate on ‘the study and planning of new methods and the development of special-purpose equipment’.Footnote 4 The tool (see Figure 1) was enthusiastically endorsed by both the press and the Home Office as an exciting ‘scientific’ aid to crime fighting, with Elystan Morgan MP, under-secretary of state of the Home Office, describing the new system as ‘a valuable innovation in the technique of criminal identification’.Footnote 5 However, this beguilingly simple narrative does not withstand scrutiny. This article, the first to look historically at this technology and its idiosyncratic inventor, shows that its development was anything but scientific. Analysis reveals a curious case with its roots firmly in the early part of the twentieth century, demonstrating perhaps what David Edgerton has termed ‘the shock of the old’.Footnote 6

Fig. 1. Photo-FIT Kit including assembly frame, collection of facial features, and carry case

Section I will situate Photo-FIT in a succession of technologies of police identification and will examine how it came to prominence in the later 1960s. Section II will then consider the long development of Photo-FIT from the 1920s, showing how this process was wholly unscientific. The ‘inventor’ of Photo-FIT, Jacques Penry (whose real name was William Ryan), had no scientific or technological background whatsoever and was driven primarily by entrepreneurialism and an obsessive focus on outmoded ideas of a link between physiology, appearance, and character. Section III will consider why, despite early evaluations showing that Photo-FIT worked no better than other, existing methods, it proved both popular and influential. Throughout, the article will argue that Photo-FIT demonstrates the long persistence of physiognomic thinking in twentieth-century Britain, and that the life and work of its inventor provide an illuminating case study of exactly how such ideas were perpetuated and transmitted. The article also highlights the way in which the development of new technologies is socially constructed and highly context-specific, and demonstrates how new technologies, once commissioned, can develop an intrinsic trajectory and inner logic regardless of proven (or otherwise) efficacy. Finally, the article as a whole reflects on police identification technologies as a lens through which to examine the ambition and the limitations of the state's desire to know and observe its citizens.

I

Surveillance capacity and the ability to establish an individual's identity are both key components of the power of the state, but have developed significantly over time.Footnote 7 Historians have recently traced the rise of state interest in individual identities, seeking to date when governments first became interested in telling who, precisely, was who.Footnote 8 Within this broad field, detailed work has focused on the genesis and development of various mechanisms of state identification and surveillance which are today taken for granted, such as passports and individual identity papers, censuses, and the computer database.Footnote 9 Following Foucault's contention that ‘the fact of being constantly seen, of being able always to be seen … maintains the disciplined individual in his subjection’, sociologists, too, have written extensively about the way in which specific technologies of identification and surveillance have gradually changed the nature of state power.Footnote 10 This is not to imply a simple dichotomy, however, with historians studying past identification systems and leaving social scientists to consider the impact of technology in the present. The field of surveillance studies is inherently multidisciplinary, and research in this field often transcends disciplinary boundaries.Footnote 11

Technologies of surveillance and identification are, of course, of particular significance to the police. Since their inception in modern form in 1829, the British police have long sought to deploy the latest technology in their attempts to identify offenders. Most early technological innovations were focused on recording the details of those arrested, so that known felons and recidivists could then be quickly identified and located in future. Thus the police were pioneers in the development of complex paper registers, card index systems, the anthropometric measurement system developed in France by Alphonse Bertillon, and, eventually, the fingerprinting system.Footnote 12 The use of photography to identify offenders in custody was pioneered within the prison service, but the police enthusiastically adopted the camera following the Habitual Criminals Act (1869), relishing the presumed ability of the photograph to enable definitive recognition of repeat offenders.Footnote 13

Thus, historically, the police have been at the forefront of the move away from direct recognition systems (such as personal knowledge or face-to-face encounter) towards the greater abstraction and presumed efficiency of technological identification systems. Research to date has, however, focused almost wholly on the identification of suspects already in custody. The history of the ways in which the police, as one of the most ubiquitous and visible arms of the state, have prepared and disseminated information intended to identify unknown suspects not in custody, often publicly, has not yet been written. The development and circulation of written descriptions of suspects during the early nineteenth century has received some scrutiny, but for the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries very little is known about this aspect of police work.Footnote 14

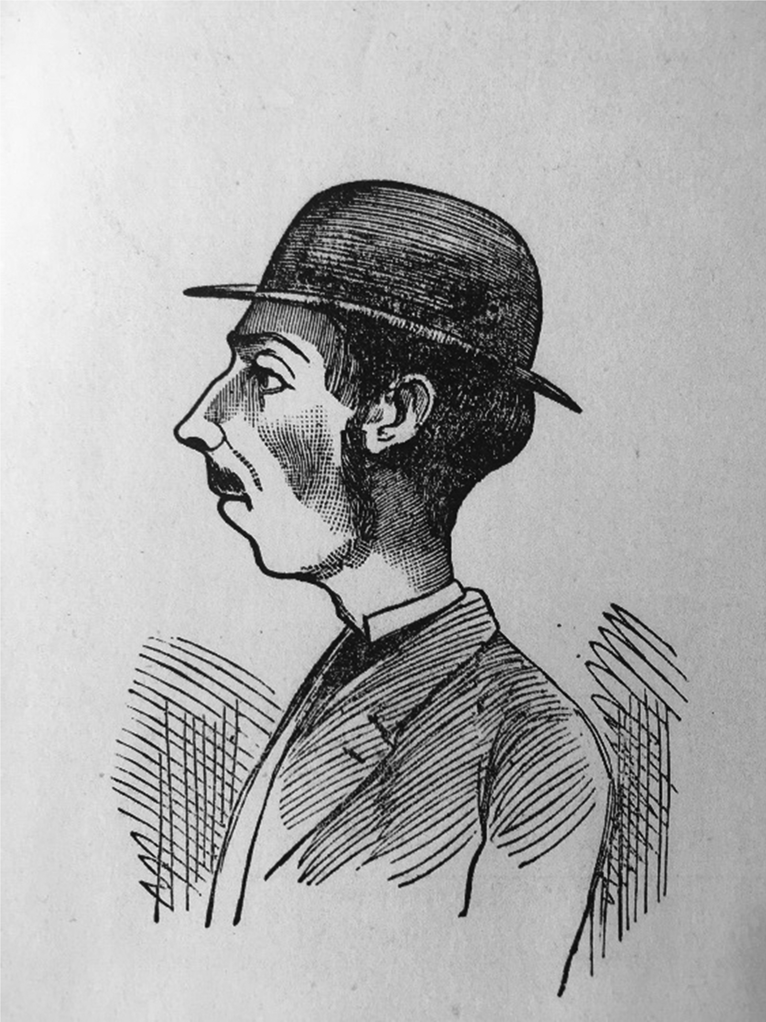

During the latter part of the nineteenth century, it is clear that some police forces began to use artists’ depictions to supplement written descriptions of suspects. One of the earliest artist's impressions circulated was that used to apprehend Percy LeFroy Mapleton for the murder of Isaac Gold, a coin dealer, on the London Bridge to Brighton train in June 1881. Mapleton was arrested when he emerged, bloodstained, from a first-class carriage on arrival in Brighton, but subsequently escaped from police custody.Footnote 15 In addition to releasing a detailed police description of the suspect, one newspaper printed a profile portrait (see Figure 2). While it is not known with certainty whether the police or the newspaper commissioned the portrait (drawn by a passenger familiar with the suspect), it produced the required result. Mapleton was eventually recognized by his landlady, arrested, and charged. Such ad hoc use of artists persisted into the twentieth century, with occasional high-profile results, as in the 1911 case of the murderer Harvey Crippen, who was arrested in New York when the captain of the transatlantic steamer he was travelling on recognized him from a newspaper portrait.Footnote 16

Fig. 2. Artist's impression of Percy LeFroy Mapleton

For the first half of the twentieth century, written descriptions and the occasional reproduction of artists’ impressions remained the norm. Then, in the 1940s, two officers within the Los Angeles Police Department (Hugh McDonald and Harry Rogers), aware of the limitations of asking witnesses either to describe suspects verbally or to peruse hundreds of mugshots, started to develop a more systematic method of characterizing and storing information about faces.Footnote 17 The system they developed sought to break the face down into component parts and to group or characterize these components such that police operators could easily narrow down a witness's description of a suspect to a small number of relevant, pre-existing, mugshots. McDonald then further developed this classificatory system, which had been rapidly adopted in the sheriff's office of Los Angeles County, and produced Identi-Kit, which was adopted by the same forces in 1959. The Identi-Kit consisted of a set of transparencies, each featuring a variety of line drawings of facial characteristics (eyes, noses, mouths, and so on).Footnote 18 Witnesses could work with an operator directly to build up an image of the suspect without having to rely on their powers of verbal description.

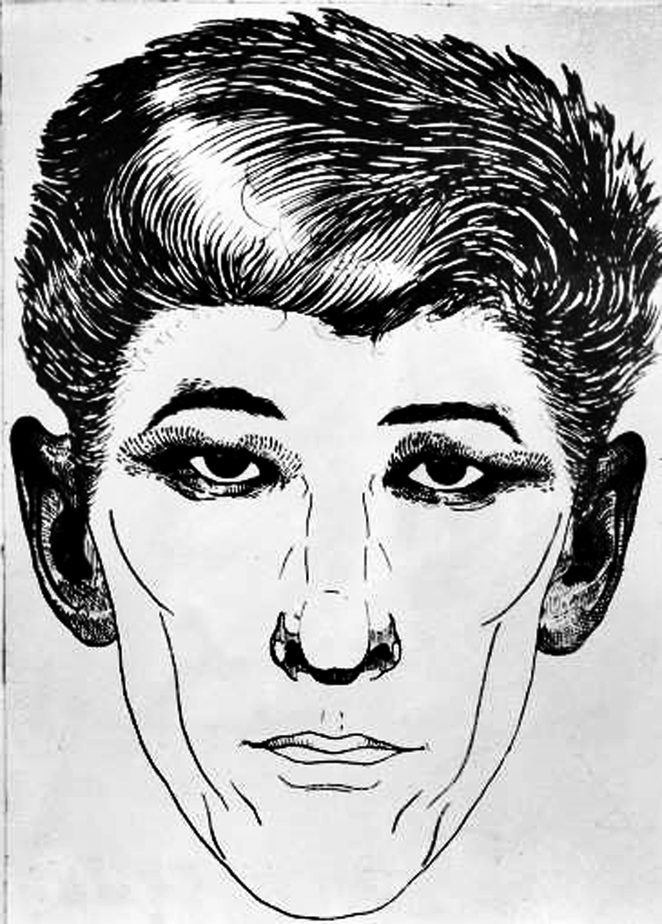

Following the sale of copies of the kit to selected British forces, Identi-Kit was first used in Britain in 1961 to identify the murderer of Elsie May Batten, who was stabbed to death in the antiques shop where she worked in Charing Cross Road.Footnote 19 An Identi-Kit image (Figure 3) drawn from witness statements was circulated both internally within police forces and externally in newspapers, with the result that a police constable recognized Edwin Bush from the image and arrested him. While this initial success was lauded in the press, and while the tool rapidly became ‘the only technique of the kind to be used widely in [the] country’, Identi-Kit suffered from ‘a number of practical problems’.Footnote 20 Forces were split on whether it was a useful technology, but the Home Office concluded that it was only effective in about 5 to 10 per cent of cases and that to produce ‘a reasonably satisfactory Identikit picture’ took ‘half a day or longer’.Footnote 21 Persistent problems centred on the availability of up-to-date UK hairstyles and accessories in the US-made kits. From 1962 onwards, forces made requests for new hats (bowler, ‘Robin Hood’, and beret) and for ‘Teddy Boy’ and other UK-appropriate hair styles (along with ‘buck teeth’ and warts). Thus, while innovative and widely used, Identi-Kit was not wholly successful, and both the Home Office and British police forces began eagerly seeking an alternative.

Fig. 3. Identi-Kit image of the murderer of Elsie May Batten

The 1960s was a period in which an impetus for technologically informed policing was developing rapidly. The 1962 report of the Royal Commission on the Police, set up primarily to address concerns over police accountability, also recommended the establishment of a central unit for planning police methods, developing new equipment, and researching new techniques, ‘so as to enable the police service to deal promptly and effectively with changes in the pattern of crime and the behaviour of criminals’.Footnote 22 This led, in 1963, to the creation by the Home Office of a Police Research and Planning Branch staffed by both police officers and scientists. In 1969 this was integrated into the Police Department of the Home Office and three new research groups were created, as below.Footnote 23

• Police Research Services Branch (under an assistant chief constable) to determine the needs of police in terms of research and to disseminate results to police;

• Police Scientific Development Branch (under a senior scientist) to develop scientific knowledge;

• Police Management and Planning Group (under an economic adviser to the Home Office) to develop a planning, programming, and budgeting system.Footnote 24

As Ben Taylor notes, the experts trained within these research units (particularly the PSDB) were to ‘introduce a range of reforms … which would form the basis for new and expansive forms of surveillance-orientated policing in Britain’.Footnote 25

It was into this fertile arena that Jacques Penry, a self-styled ‘facial topographer’, pitched an idea for a new form of police identification technology. The path to the adoption of what was initially called ‘Penry's facial identification technique’, but soon rebranded as Photo-FIT, seems on the surface straightforward. The planned system broke the face down into five component parts (jawline, mouth, nose, hairline and ears, and eyes). The eventual kit would contain photographs of approximately 500 variants of these constituent parts, allowing the operator to work with a witness to produce a photo-realistic image of the suspect. The level of realism of the eventual image, and the speed and ease of use of the system, were its projected benefits over Identi-Kit. Having initially contacted several chief constables, in 1968 Penry wrote to the Home Office's Police Research Branch, which immediately evinced interest in seeing a working prototype developed.Footnote 26

Claiming significant scientific expertise in the field of facial recognition, Penry was given access to the photographic ‘mugshot’ books of a selection of police forces in order to gather enough facial features to construct a working kit. He did this by hand, working at home in Tunbridge Wells, and later ruefully noted: ‘little did I realize that in dry or centrally-heated conditions the parts would curl’, giving rise to ‘much difficulty and frustration’ both for the inventor and for those who later tested his prototypes.Footnote 27 Two prototypes were tested by the Bristol and Birmingham forces; while they were doing so, Penry deftly negotiated an agreement with the board game manufacturer John Waddington Ltd that it would produce the kit under licence if adopted by the Home Office. Once trialled, Photo-FIT was rapidly approved for police use and Penry's deal with John Waddington Ltd came into effect.

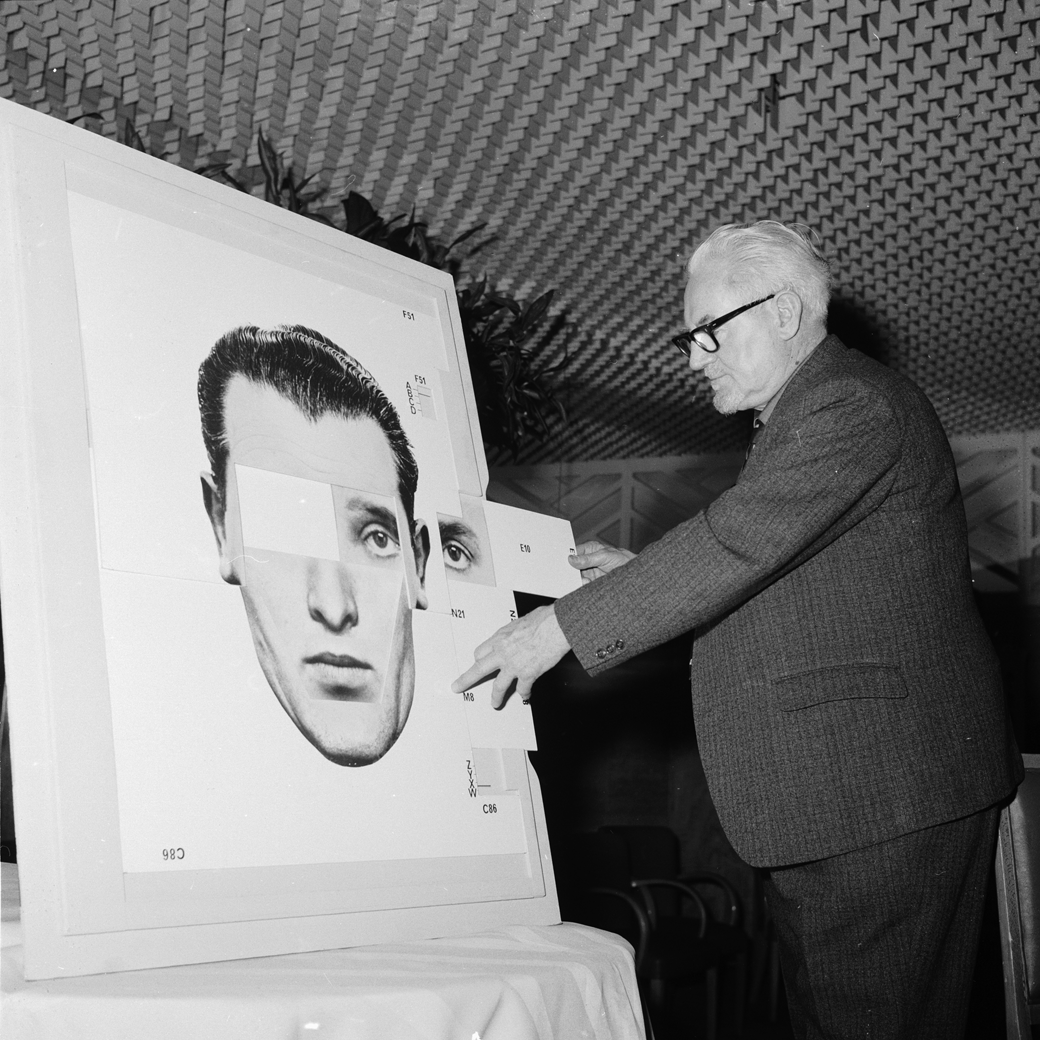

Participants at the launch event, held at the Savoy Hotel on 22 April 1970, were indicative of high-level backing and enthusiasm. They included a minister from the Home Office (Morgan), two high-level representatives from the PSDB (Venner and Howells), one of Her Majesty's inspectors of constabulary (Bebbington), and both the director and the managing director of John Waddington Ltd. Penry was also present and, indeed, took centre stage for much of the proceedings. Following a champagne reception, Penry gave a demonstration of the tool (Figure 4) and a long series of television and newspaper interviews.Footnote 28 Morgan, in opening the event, noted that initiatives like Photo-FIT would allow the Home Office ‘to transform the scientific approach of the police service to the mounting problems confronting them’.Footnote 29

Fig. 4. Jacques Penry constructing a Photo-FIT image at the 1970 Savoy launch

Photo-FIT was rapidly rolled out to police forces across Britain. Its distinctive composite images were primarily used internally within the police but were released to the public and the press in high-profile cases, often with successful results.Footnote 30 Thus the adoption of Photo-FIT seems on the surface a simple story of successful science in the service of policing, indicative of ‘the closeness of police power to the modern state’ and the way in which ‘police technology has been backed by successive governments who have given police leaders the money to invest in up-to-the-minute systems’.Footnote 31 Looking more closely, however, reveals a much more complex picture. As section II will show, Photo-FIT was not an invention of the 1960s but can really be dated to the 1930s. Its development was not ‘scientific’ by any stretch of the imagination, and in fact owes much to later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century notions of physiognomy. And, perhaps most remarkably, it did not really work very well (at least initially) but was adopted and promoted for a host of ancillary reasons which had little to do with the efficacy of science and technology in the service of policing. Understanding the genesis and adoption of Photo-FIT, and what it can reveal about policing, technology, and visual culture in the later twentieth century, first requires an analysis of the extraordinary life and work of the ‘inventor’ of Photo-FIT.

II

Jacques Penry was variously described during his lifetime (by himself and others) as a facial topographer, ‘nose-reader’, psychologist, journalist, illustrator, television personality, inventor, and boffin. Above all else, however, he might more accurately be described as both an entrepreneur and a physiognomist. His activities in the realm of facial ‘reading’ and recognition, leading up to the launch of Photo-FIT, may be divided into three distinct phases: the 1930s, 1950s, and 1960s.

Born in Bristol in 1904, Penry moved to Canada as a child and was brought up in Quebec.Footnote 32 He spent some time in the early 1930s in west Africa working for a forestry company before moving back to Britain, where he began working as a ‘quick sketch artist’ at private parties. While sketching, he also provided ‘character readings’ based on the facial features he observed. At one such event, hosted at the Grosvenor House Hotel, he both sketched and provided a character reading for a feature writer at the Daily Express. The journalist was impressed enough to write up his experience in the paper the next day, reporting that ‘nose-reader’ Penry was able to tell a great deal about individuals from their profiles.Footnote 33 Those with a ‘straight Grecian sort of nose’, for example, were likely to have ‘an artistic temperament’ and a ‘practical personality’. The article generated sufficient interest that the Express asked readers to send in photographs of their noses/profiles and engaged Penry to provide readings, which it subsequently printed with headlines such as ‘Three noses tell different stories’.Footnote 34

Penry appears to have rapidly understood the commercial potential of interest in character readings from photographs, and in 1938 he published a book, Character from the face, which sought to capitalize on this early success. As noted on the book's title page, Penry intended the work to provide ‘a complete explanation of character as it is shown by the size, proportion and texture of each feature’. In essence, he believed that ‘as we grow mentally and physically our character traits mature accordingly. As character develops that development is shown on the face.’Footnote 35 The bulk of the book consisted of photographs of different facial characteristics – noses, foreheads, eyes, eyebrows, mouths, ears, and wrinkles – with each exemplar identified by an alphanumeric code (e.g. A2) along with a description of the character traits which such features (and combinations of features) would denote. Many of these were extremely specific. For example, a D8 eyebrow would indicate an ‘unsociable, self-centred disposition’, but when combined with an H22 cheek dimple would mean that the individual was ‘very particular in the choice of friends’.Footnote 36 Penry claimed that the book would enable readers to assess character with ‘scientific accuracy’ and ‘to know to what extent a new acquaintance is reliable, pleasant or trustworthy’.Footnote 37

The term ‘physiognomy’ was used at various points within the work. In this, he was not alone during the 1930s and 1940s. While it might be tempting to think that nineteenth-century physiognomic thinking was unravelling as the twentieth century progressed, there were in fact significant attempts still being made to link particular physical features and attributes with specific character traits in the 1930s.Footnote 38 In Germany, the psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer had been using photographs to characterize people into ‘types’, each associated with a predisposition to particular psychiatric disorders.Footnote 39 In the USA, William Sheldon, the founder of ‘constitutional psychology’, had similarly sought to link ‘somatotype’ classifications of body shapes with varieties of temperament, while, in France, the psychiatrist Louis Corman coined the term morpho-psychologie to indicate the links between mental capacity/illness and particular bodily and facial features.Footnote 40 Thus, Penry's Character from the face was very much of its time. What is particularly noteworthy here is the way in which Penry hung on to such ideas as he developed this early work into a lengthy career.

The publication of Penry's first book led to a range of other media opportunities. He was engaged, for example, by the baby food manufacturer Cow & Gate. As part of an advertising campaign, Cow & Gate declared that they had obtained the services of ‘the world-famous physiognomist, Jacques Penry’, who would ‘without charge describe your child's character from a photograph and give an indication of the direction in which his or her talents are likely to develop’.Footnote 41 Penry secured further newspaper employment, too, focusing on telling Daily Mail readers ‘why their children are naughty, shy, lazy, fretful; the best way to put them right; what career would suit their temperament and abilities’.Footnote 42 Parents were enjoined to send a photograph and to ask specific questions pertaining to their child's future development and character. Penry undertook to answer all enquiries, with a selection being printed in the paper on a weekly basis. In the same year, he secured a similar column in the Daily Mirror. Footnote 43 In 1939, Penry was featured on Pathé news. Described as an ‘eminent psychologist’, he claimed to ‘read’ more than 20,000 faces annually and, in the clip, drew the profiles of two young women also present on camera (see Figure 5) before going on to describe the personality characteristics he had inferred from observing them.Footnote 44 For example, Penry claimed that ‘Number 1 was aggressive, determined, practical, and much of the motor type’.Footnote 45

Fig. 5. Jacques Penry describing character traits evident in two profile drawings, 1939

Just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, Penry drew on his assembled body of work to patent and launch a board game called ‘Physogs’. As Figure 6 demonstrates, the game drew on the typology of facial characteristics already developed in Character from the face and Penry's multiple newspaper columns. It required players to construct faces indicative of particular character traits (anxious, friendly, etc.), but they could only do so by using facial features consistent with that type of personality according to Penry's code (as partially reprinted in the game's instructions). Thus, the game was won not by utilizing the appearance of a particular set of features but by knowing its presumed inherent or underlying characteristics as determined by Penry.

Fig. 6. Elements of the board game Physogs, invented by Jacques Penry in 1939

The approach and eventual outbreak of war did not initially dent Penry's entrepreneurial approach to his work. He simply adapted his existing column and, alongside analysing pictures of children, asked Daily Mirror readers, particularly women, to send in a picture of themselves so that he could determine from their faces alone what type of war work (territorial army, auxiliary corps, civil air guard, etc.) they would most be suited to.Footnote 46 He even, on occasion, provided facial analyses of key military figures, so as to ‘prove’ that their eventual success was assured.Footnote 47 Eventually, however, the war drew Penry away from such work and, after the war, he returned to west Africa until the early 1950s. While his wife, Isobel Ryan, periodically contributed pieces to the Guardian during this period, Penry himself did not write for the press (although he did illustrate his wife's contributions).Footnote 48 On his return to Britain c. 1952–3 he sought to pick things up where he had left off. In a familiar pattern, he first published a book: The face of man. Subtitled ‘a study of the relationship between physical appearance and personality’, this book, too, sought to lay bare ‘the complex relationship between physique and personality … to show how body and mind affect and are affected by each other’.Footnote 49 Presumably owing to his long sojourn in Africa, this work consisted predominantly of line drawings made by Penry, rather than photographs, to illustrate a range of facial characteristics.

Penry pitched The face of man at a popular audience, and the book's early chapters are scornful in places of ‘the multi-syllabled words which make up the weighty treatises of many eminent psychologists’ and ‘the modern practice of child psychology’ which had ‘obscured much that should be clear’.Footnote 50 That said, a change in approach from Character from the face (1938) is shown in Penry's addition of quotations and references to a series of (relatively aged) psychological and scientific treatises, presumably to give the new book a veneer of scientific authenticity. Among those referenced (and bear in mind the 1952 publication date) were Henry Maudsley's Body and will (1870) and George Lewes's Problems of life and mind (1874), although Penry also cited Kretschmer and a range of somewhat more recent works focused on the endocrine glands.Footnote 51 For Penry, unsurprisingly, it was the face that held the key to divining character, as ‘glandular “types” may be recognized by their facial appearance and … by a careful study of a man's face his personality and innate ability may be determined with a great degree of accuracy’.Footnote 52 He believed that the endocrine system provided the scientific link between early growth, appearance, and character. So-called ‘thyro-centrics’, for example, had particular physical characteristics, but also had ‘great difficulty in conforming to established customs and moral laws’ and were often ‘outrageously irresponsible morally’.Footnote 53

As might be expected, Penry parlayed the public exposure generated by his latest book into occasional media work, often focusing this time on relationship advice. As one piece in the Daily Mirror noted, ‘Jacques Penry, world famous authority on reading character from the face, explains how to pick the face of your ideal mate WITH PICTURES’.Footnote 54 He also successfully established himself at the centre of a short series of television programmes in 1954 entitled Let's make faces.Footnote 55 As well as Penry, these featured Fred Cherrill, a well-known fingerprint and handwriting expert who had retired the year before and was similarly seeking to promote a recent book.Footnote 56 It is clear from BBC archival documents that the programme was entirely Penry's brainchild and he was the primary focus. He had developed the initial idea and script with an agent (Alan Blomfeld), and they sent this speculatively to the BBC, who agreed to produce the programmes. In each one, Penry would outline for celebrity guests and the audience his method of breaking the face down into constituent parts and recombining them (Figure 7), highlighting the attributes associated with different features.

Fig. 7. Jacques Penry working on illustrations for Let's make faces

An initial script indicates that Penry intended to conclude each programme with the words ‘after seeing this programme … I hope … you will give more thought to the far-reaching possibilities of facial character-analysis and that you will be more conscious of the fact that faces are not merely plain or decorative exteriors, but are indeed mirrors to the character itself’.Footnote 57 The series was broadcast on Saturday nights, and an audience research report on the first programme concluded that roughly 58 per cent of the ‘adult TV public’ watched it (around 14 per cent of the total adult population of the UK), although, ‘when it came to Penry's own conclusions about character in faces, viewers were more inclined to regard these as ingenious rather than convincing’.Footnote 58 A fleeting reference appears to indicate that the first programme may have facilitated an initial contact between Penry and the Kent police, who engaged him in 1954 to provide ‘a course for the police of assessment of character through the face’.Footnote 59

However, no productive or lucrative momentum was generated by any of these engagements, so Penry once more returned to work in west Africa during the later 1950s, from where Isobel again contributed to the Guardian, while Penry worked as manager of a timber company.Footnote 60 Returning to England to commence their son's schooling, and following an ill-fated attempt to establish a Canadian gift shop in Tunbridge Wells, by 1968 Penry was very short of money. As he later wrote, ‘I couldn't pay our rent, had no money to buy groceries and was obliged to sell valuable to us, but not needed now, personal possessions.’Footnote 61 He decided to make one last attempt at a comeback as ‘the faces man’, but his newspaper and television contacts yielded nothing at this point. After writing to a number of chief constables, Penry approached the Home Office Police Research Branch, who were interested in his ideas. The initial adoption of Photo-FIT then proceeded as outlined in section I. Penry convinced the Home Office to let him produce prototypes by using police mugshot books. These were tested and the system endorsed and rolled out both nationally and internationally (with the assistance of John Waddington Ltd). By July 1970, only a few months after the official launch at the Savoy, around three-quarters of British police forces (thirty-four out of forty-seven) were already using Photo-FIT.Footnote 62

With the background of Penry's career to date now in view, however, the entrepreneurial zeal with which he approached the task of developing Photo-FIT seems less the result of an acknowledged expert burning to unleash his latest invention on the world, and more simply an extension of the manner in which he had always sought to promote and monetize his physiognomic ideas of a link between character and face. As has been demonstrated, there was no ‘science’ underpinning the long development of the composite approach to facial recognition inherent in Photo-FIT, despite the desire by both Penry and the Home Office to claim otherwise. Rather, Photo-FIT should be considered ‘pseudo-science’ – another in the long line of technologies which have perpetuated ‘criminal anthropology's fruitless search for visible stigmata of criminality’.Footnote 63 The following section will therefore consider why, despite early evaluations showing that Photo-FIT worked no better than other, existing methods, it proved both popular and influential.

III

As soon as Penry had developed his prototype versions of Photo-FIT, they were tested by the Home Office and trialled within a number of police forces. These initial trials indicated cautious enthusiasm on the part of the police but were by no means an unalloyed success. Home Office tests side by side against Identi-Kit showed equal efficacy at best.Footnote 64 The earliest field survey of the use of Photo-FIT, undertaken by the PSDB during the winter of 1970–1, reported quite poor results. Photo-FIT only contributed to the arrest of a subject in about 13 per cent of cases when used.Footnote 65 While a Criminal Intelligence Branch review of Photo-FIT a few years later concluded that it was ‘a very useful weapon indeed in the fight against crime’, this conclusion was reached despite the fact that ‘no separate statistic record’ was maintained of cases in which Photo-FIT was used. The statement appears thus to have been based on purely anecdotal evidence.Footnote 66 The earliest external evaluation of the efficacy of Photo-FIT in relation to the reconstruction of facial features, undertaken in laboratory conditions by a group of psychologists at Aberdeen University, concluded that most people had difficulty making up an accurate reconstruction of a face with Photo-FIT, even when a photograph of the face to be constructed was placed in front of them. When performing from memory, as witnesses would, the results were ‘even poorer’.Footnote 67 Much to the dismay of Penry and John Waddington, this adverse report received significant press coverage.Footnote 68

Thus, early analysis of the use of Photo-FIT by no means revealed a step change in the success rate of police identification techniques. The PSDB conducted a further survey in 1976, aiming to evaluate more precisely how extensively Photo-FIT was used and its ongoing efficacy.Footnote 69 By this point, forty-one of forty-three forces were using Photo-FIT, with just one force still using Identi-Kit. However, in an analysis of 729 cases in which at least one composite image had been constructed, after two months only 140 had been closed and, of these 140, only 35 cases had closed owing to the use of Photo-FIT. These figures were reported approvingly but, of course, they indicated that fewer than 5 per cent of Photo-FIT composites circulated led to any kind of arrest. Moreover, in more than 60 per cent of cases, the primary advantage of Photo-FIT (its straightforward mode of operation) was undermined as police operators reported having to add details not included in the kit using a chinagraph pencil.Footnote 70 In 45 per cent of cases where composites were prepared, this study concluded that they were ‘not very useful’ or ‘no use at all’.Footnote 71

Alongside this rather lacklustre performance, Penry was still seeking to promote his outmoded physiognomic ideas about a link between facial features and character and behavioural traits. In an article in a police publication shortly after the launch of Photo-FIT, for example, he foresaw a time when

witnesses will be able to describe a face either in precise terms of physical shape or, with similar exactness, the personality it projects. On such a double wave-length of communication the operator would be able to manipulate his picture-making ‘tool’ equally well by a direct selection of type sections, or via his capable interpretation of a character description.Footnote 72

In other words, for Penry, the link between face and character was so strong that it would be possible accurately to reconstruct a face simply by reference to the character and behaviour of an offender. In the book which he published in 1971, true to past form, to capitalize on the launch of Photo-FIT, he once again argued that ‘no study of a face is complete without some understanding of the link between physical appearance and personality … we cannot “see” personality. We can see the face which accompanies various kinds of personality.’ Footnote 73 The work was intended in part for distribution to police offices, yet Penry was still drawing doggedly on outmoded works on endocrinology from the 1920s and 1930s, and on his own 1952 book, The face of man. Footnote 74

And yet, despite the initial lack of success of Photo-FIT and the aura of outmoded pseudo-science in which Penry cloaked his invention, momentum gathered around its continued use. This begs the question – why? Why was this new tool, developed in a wholly unscientific manner by a rather eccentric if entrepreneurial individual, so successful? It seems likely that this was due to a combination of factors, including the particular context into which Penry pitched his idea, the innovative nature of the public–private partnership which ensued, and the way in which the onward development of Photo-FIT rapidly gained its own inherent momentum.

Turning first to context, it is important to see developments such as Photo-FIT as part of a long-standing interest on the part of senior police officials in ‘scientific aids’ to policing.Footnote 75 While interwar enthusiasm, as evidenced in the recommendations of the departmental committee on detective work (1938), had been stymied during and immediately after the Second World War, interest in scientific policing was certainly not novel in the 1960s.Footnote 76 As touched upon in section I, in the later 1960s the newly instigated PSDB was actively looking to develop an agenda of ‘science in the service of policing’. Both the Labour party and the Home Office, headed at the time by James Callaghan, were similarly ready to back such new endeavours.

In addition to this broader institutional context, rapidly rising post-war crime rates had generated an impression among the public of a failing criminal justice system in need of significant reform. As Paul Rock notes, ‘the surge in offending had a momentum that appeared unstoppable, incomprehensible and deeply disquieting’.Footnote 77 Against this background, both public and police were concerned during the 1960s with police identification practices. Within the police, there was a clear dissatisfaction with existing identification techniques (particularly Identi-Kit); equally significantly, cases of mistaken identity were also attracting increasing public scrutiny at the time. There had been a number of high-profile miscarriages of justice centred on incorrect identifications by eyewitnesses (such as the 1969 case of Laszlo Virag). While most of these had involved identification from photographs and at identification parades, the National Council of Civil Liberties had been collating reports to put pressure on the police, and the Home Office was encouraging the police to refine their identification practices.Footnote 78

The issue of identification was thus of considerable debate within the police during the later 1960s. Senior officials were well aware that crooked lawyers were attempting to subvert the criminal justice system by calling police probity into question, often in relation to identification practices.Footnote 79 The issue was discussed several times at meetings of the Central Conference of Chief Constables, which noted (in May 1968) that ‘growing public interest in identification parades’ and ‘a memorandum from the National Council of Civil Liberties alleging wrongful convictions on identification evidence’ made the issue ‘especially topical’.Footnote 80

Thus, in many ways, Penry could not have found a more receptive audience when he made initial contact with the Home Office. He presented himself as an expert in facial recognition and his self-evaluation seems to have been taken at face value. Photo-FIT had the appearance of science. The photographic realism it offered made it seem a natural, progressive successor to the line drawings available in Identi-Kit, regardless of evidence to the contrary. Comparison here with the history of the lie detector is fruitful. The lie detector was repeatedly discredited throughout the twentieth century but held (and continues to hold) the promise of truth, and hence its use was prolonged. Despite its obvious flaws, it fulfilled a very twentieth-century desire to deal with deviance in a ‘techno-scientific’ manner.Footnote 81 While Photo-FIT produced a composite image, and was never intended as an accurate representation of any individual, the confidence extended to it by the police can also be considered as an expression of the power inherent in the photographic image from the later nineteenth century, and as an adjunct of the emergence of ‘new institutions of knowledge’ which enabled ‘photography to function, in certain contexts, as a kind of proof’.Footnote 82

The deal under which Photo-FIT was produced and distributed, negotiated largely by Penry himself, is another factor which can help to explain its continued use. Once it was commissioned, all parties had a clear vested interest in the success of the tool. Penry himself did well out of the deal. Although he always subsequently claimed that he had not received adequate recompense, he was paid c. £3,500 for the production of the prototypes alone (worth at least £50,000 in 2019).Footnote 83 He received royalties of 10 per cent on the sale of Photo-FIT kits, amounting to £9,428 by June 1974.Footnote 84 Considering that he was unable to pay his rent in 1968, this funding would have provided significant motivation to energetically promote and sustain his invention. He willingly spoke at a huge range of promotional events and travelled on a variety of international tours to showcase Photo-FIT and secure sales.

John Waddingon Ltd, too, having invested significant speculative funding in the development of Photo-FIT, were very keen to ensure its continued adoption. While the price to the British police was capped, they were guaranteed a market as long as Home Office endorsement continued. Thus, they were active in developing and improving the kit in response to initial user complaints, issuing a female face kit and updating all kits to include non-white skin tones, as well as developing a Native American kit for distribution in Canada and the USA. Waddington Ltd were allowed to charge significantly more to overseas buyers, and produced glossy promotional literature in a wide range of languages. These all included the important statement, prominently placed alongside the government crest, that the product had been ‘developed in collaboration with the British Home Office and the British Police Service’.Footnote 85 Initially, overseas sales were direct, but fairly soon contractual arrangements were made. The North American distribution rights, for example, were sold for £25,000 to Colt Firearms later in 1970.Footnote 86 Thus the manufacturer, too, had a strong vested interest in promoting the product.

As the endorsement on the promotional flyers indicates, this was an interesting early form of public–private partnership. While it was not unknown for private companies to assist the police service and/or the Home Office with the provision of new technology during the 1960s, in the case of Photo-FIT the Home Office also received royalties of 2 per cent of all kits sold, in recompense for its public endorsement.Footnote 87 For this reason, as well as for the prominent, positive publicity the Photo-FIT system generated, the Home Office and the PSDB never really questioned its onward trajectory. Within the police service, too, a strong vested interest in continuing with the technology rapidly arose. Penry and John Waddington Ltd provided training programmes to police users of Photo-FIT from its earliest inception. In October 1971, for example, three regional events took place in Birmingham, Leeds, and London. A further similar meeting was convened at the Scottish Police College. Most forces were represented and more than a hundred police officers attended in all, with ‘10 men from the Army Special Investigation Branch’ also participating.Footnote 88 Overall, there were around 570 Photo-FIT operators by the mid-1970s.Footnote 89 In evaluations of Photo-FIT undertaken by the PSDB, it was these officers who were canvassed and, naturally, many advocated for its continued refinement.

With this broad context laid out, the continued use of Photo-FIT even in the face of lacklustre results and the outmoded pronouncements of its inventor becomes more explicable. This analysis of Photo-FIT thus supports the arguments made by others concerning the defining role of social systems in the adoption of new technologies, foregrounding the role of contingency and the significance of societal and organizational networks over the idea of the new in ‘splendid isolation’.Footnote 90

The curious case of Photo-FIT does have one final twist, however. While, as has been demonstrated, its development and adoption were anything but a triumph of science, its later development in many ways was. Prior to the advent of Photo-FIT, while psychologists were interested in faces and facial recall, scientific studies had been hampered by ‘the lack of a suitable instrument with which subjects could reconstruct their recollection of a face’.Footnote 91 Following the early tests using Photo-FIT undertaken at Aberdeen University, key researchers there secured funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in order to try to correct ‘the difficulties and shortcomings of the Photo-FIT’ via ‘the application of systematic experimental techniques’.Footnote 92 These early pioneers – including Hayden Ellis, John Shepherd, and Graham Davies – went on work closely with the PSDB and its successors both to improve Photo-FIT and to develop general psychological understandings of how faces are perceived and recalled.Footnote 93 From its inauspicious beginnings, Photo-FIT therefore contributed materially to both the development of a distinct sub-field of psychology and the advent of increasingly sophisticated technologies for the production of composite images, such as E-FIT and EFIT-V, which gradually superseded the mechanical Photo-FIT kits from the later 1980s onwards.Footnote 94

IV

This article has analysed the long development, adoption, and refinement of the Photo-FIT system for the identification of suspects, used by police forces around the world from the 1970s. It has placed Photo-FIT in a succession of other technologies of identification and shown that, far from demonstrating the onward progress of science and technology, and the way in which both were harnessed to the power of the state in the twentieth century, Photo-FIT was the brainchild of an idiosyncratic entrepreneur wedded to increasingly outmoded notions of physiognomy. Its adoption was primarily determined by the particular context of the later 1960s, and its continued use owed more to vested interest and energetic promotion than to scientific underpinnings or proven efficacy. It did, however, in the longer term, provide the impetus for the development of a new sub-field of psychology and pave the way for the development of increasingly sophisticated facial identification technologies used today.

A number of broader conclusions can also be drawn from this article. First, it demonstrates the long persistence of physiognomic thinking in twentieth-century Britain. The life and work of Jacques Penry provide a case study of how such ideas are transmitted across decades and how they find purchase in both public and private fora. Handbooks for new police recruits still show evidence, well into the 1980s, of the tenacity of notions of a link between outward appearance and inward character.Footnote 95 Photo-FIT and Penry's publications and training both tapped into and perpetuated this trend.

Second, Photo-FIT provides a clear demonstration of the ways in which the development and acceptance of a given technology are socially constructed, and of the persuasive power of pseudo-science. New technology does not simply represent new and better ideas, but rather always emerges from and is determined by particular social contexts.Footnote 96 Forensic technologies with the appearance of science offer the public and the state the illusion of certainty, of order in the face of the unquiet and turbulence which deviance manifests. But the long history of forensic science scandals indicates that Photo-FIT was by no means the last technology to be embraced by the criminal justice system in spite of its flimsy claim to scientific underpinnings.Footnote 97

Third, Photo-FIT speaks to the power of visual culture and of photography in particular. The photographic realism of Photo-FIT contributed significantly to its acceptance, tapping into an implicit belief that a visual description is superior to a textual one, and that a photo-realistic image is more efficacious than an artist's impression or line-drawing composite. Photo-FIT is part of the story of the way in which culture in Britain became increasingly visual during the twentieth century.Footnote 98

At the inception of the modern police in the later eighteenth century, Jeremy Bentham argued that the state should ‘lose no occasion of speaking to the eye’, and that criminals should experience ‘a permanent subjection to the conditions of being onstage, albeit with none of the sense of an approving audience’.Footnote 99 Photo-FIT may be seen as one in a succession of technologies designed to provide just that. Its adoption and use, however, serve as an interesting case study of both the ambition and the limitations inherent in the state's desire to observe and to know.