Introduction

Things change you know. They really change from what they used to be. I don't know why because when I was in school, I remember Mexicans and White all mixed together, you know in the lower grades.

—Julia Leyva, Worland, WyomingFootnote 1On September 11, 1956, a group of White parents—called the Committee of Citizens— attended a school board meeting in the small agricultural town of Worland, Wyoming. They were protesting the discrimination their children were experiencing in being forced to transfer to the recently desegregated West Side School, known locally as the “Mexican” or “Spanish school.”Footnote 2 Edith Scollard, one of the parents whose children were going to be placed in a classroom with majority Spanish children, protested against “her children integrating with the Spanish element in the school system.”Footnote 3 At the meeting, however, the school's principal read the school census out loud to reveal that out of a classroom of thirty-eight students, only four were Spanish-speaking or children of Mexican descent. Scollard was informed that the school board could not promise that her child would not be transferred and that the attitude of the board had always been one of seeking equality throughout the school system. The meeting recorder made note of the exchange, writing that “Mrs. Scollard's issue was racial and one against integration.”Footnote 4 The incident at Worland was not an isolated affair but signaled the collapse of a Jim Crow-like school system in Wyoming—officially nicknamed the Equality State—that targeted Mexican children during the Great Depression.Footnote 5

Figure 1. Documented locations of segregated Mexican rooms and schools in the upper Mountain West. Image created by author.

The educational experiences of Mexicans have always been tied to their racial status and identities. As historians of the Mexican experience in the US West have documented, although legally White, Mexicans were considered non-White and treated as a “race of their own.”Footnote 6 This racial logic in various places in the US was unclear, and some attempted to segregate Mexican children on grounds they had “black blood,” were racially mixed, or were Indigenous.Footnote 7 In other cases, Mexicans were declared part of the White race to dismiss Mexican parents’ challenges to school segregation.Footnote 8 One vivid example is a 1914 desegregation case in Colorado where Mexican parents challenged school segregation on grounds that they were of the “Mexican race,” and being forced to attend the city's segregated Mexican school was in violation of the state's constitution that barred discrimination in public schools on the basis of race or color.Footnote 9 The White school board countered that no violation occurred because Mexican children were “white children of the Caucasian race.”Footnote 10 Only in 1930 did the US Census identify Mexicans as a separate racial category; still, no state or federal laws allowed for the racial segregation of Mexican children in schools. In 1940, the US Census eliminated the Mexican race category, and once again Mexicans were identified as part of the White race.Footnote 11 With outright confusion on the racial status of Mexicans and no laws permitting their segregation, schools played a distinct role in dictating the place of Mexicans in racial hierarchies.Footnote 12 This especially holds true in Wyoming, where in many cases schools were the only institutions that could make and hold the color line.Footnote 13

Mexican American educational history in Wyoming is virtually nonexistent.Footnote 14 This scholarly neglect signifies a larger omission of the role public schools played in race formation in the state and the US West.Footnote 15 The omission has led to scholarly contradictions and a prevailing myth that despite having a permissive segregation law (allowed by not legally required), segregated schools based on race were never established in Wyoming.Footnote 16 This myth has deviated little from similar views promoted by Wyoming officials in the late nineteenth century. For instance, during congressional testimony in 1889 regarding Wyoming's statehood, the Wyoming territorial representative—Joseph Maull Carey—declared to Congress that in Wyoming, “there is no question of race. Our first legislature . . . opened the doors of her public schools to blacks as well as to the white children.”Footnote 17 When pressed further if race distinction existed in Wyoming schools, Carey simply stated, “No.”Footnote 18 Yet this myth is just that, a myth. Wyoming was home to failed and successful attempts to segregate Asian, Black, and Indigenous children.Footnote 19 However, no group experienced racial segregation in public schools on such a scale than the Mexican American and Mexican population residing in the state. By the dawn of World War II, segregated educational tracks, classrooms, and schools based on race were the experience of many Mexican American and Mexican children in Wyoming, mirroring the Jim Crow experiences of the Southwest.Footnote 20

In this article, I examine the development and expansion of racial segregation targeting children of Mexican descent in Wyoming during the Great Depression. In the 1920s segregation of Mexican children was a rarity. But it became commonplace in the 1930s. This study illuminates the central role of schools in the racial formation of Mexicans as a separate and distinct race.Footnote 21 Wyoming developed multiple segregation strategies for Mexican children, ranging from separate tracks and separate rooms to the establishment of separate schools.Footnote 22 Wyoming, in fact, received federal funds vis-à-vis the New Deal for the sole purpose of segregating Mexican children. New Deal funding and federal legislation such as the Sugar Act in 1934 and its subsequent revision in 1937 were essential to the buildup of structural discrimination targeting Mexicans in the state. Historian David G. García in his study of Oxnard, California, found that local elite and everyday White people—civic and business leaders, teachers, parents, homeowners—were central in the race and school segregation of the resident Mexican community. García named this group the “white architects of Mexican American education.”Footnote 23 Wyoming expanded this definition by demonstrating how European immigrants such as German Russians, as well as state and federal agencies, were part of this “white architects” group.

This study of Wyoming analyzes segregated schooling from a racial relational lens. Historian Natalia Molina aptly argues that to understand the construction of the racial category of “Mexican” we must understand its relationship to other racialized groups.Footnote 24 The areas in Wyoming where segregation developed were not governed by racialized binaries but instead were multiracial and ethnic environments. The sugar beet industry recruited Filipino, German Russian, Japanese, and Mexican agricultural labor to the state.Footnote 25 However, it was the relationship between Mexicans and Eastern European immigrants, the German Russians, that would be the most pronounced, especially in schooling.Footnote 26 Until the Great Depression, White school and state officials saw Mexican and German Russian children as part of the same “educational problem.” In fact, when comparing the two groups of students academically and attendance-wise, one superintendent noted that “of the two classes, the Mexicans are the better.”Footnote 27 It would not be until 1936 that Mexicans in said community would be sent to a segregated school and this would be duplicated in some fashion throughout Wyoming. Thus, one cannot talk about the segregation of the Mexican child on the one hand without acknowledging the integration of the German Russian on the other.Footnote 28 Emboldened by the New Deal and rising anti-Mexican sentiment by White and German Russian parents, schools became the architects of race, with educators such as teachers, principals, and superintendents becoming the final actors in the race-formation process that distinguished Mexicans from all other racial groups.Footnote 29 In Wyoming, public schools finalized the institutionalization of Mexicans as non-White and thus created the “Mexican race.”

A Brief History of Mexican Children in Wyoming Schools

Wyoming's Mexican presence dates back to territorial days of the late nineteenth century, though the Mexican population became noticeably permanent in the twentieth century.Footnote 30 The number of Mexicans grew quickly, from 2,051 in 1920 to 7,174 in 1930, making Wyoming the state with the seventh highest percentage of Mexicans in the US.Footnote 31 The majority of the Mexican population settlement was a consequence of the state's expanding sugar beet industry, which was dependent on migrant and family contract labor. Mexicans soon became invaluable to Wyoming's agricultural economy, even prompting Wyoming senators and farmers to go before Congress in 1928 to protest restrictive immigration legislation.Footnote 32 In compelling testimony by John B. Kendrick, senator and former governor of Wyoming, he claimed, “I say to you in all sincerity that if you do prevent us from getting that Mexican labor you are going to destroy the beet sugar industry of my State.”Footnote 33 The former governor understood that Mexican labor was central to the state's economy.

The fact that the Mexican laborers brought their children to Wyoming influenced the way sugar beet companies went about recruiting and retaining them.Footnote 34 A distinct component of the sugar beet industry of the Mountain States—Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, and Wyoming—was the massive Mexican colonization project focused on family recruitment and the creation of company colonies that housed families during the winter.Footnote 35 This strategy reached its apex during the latter 1920s, and by 1929, the colonization endeavor in Wyoming created Mexican settlements in areas such as the Big Horn Basin, the North Platte Valley, Sheridan, and Wheatland.Footnote 36 As a consequence of the family labor practice and colonization schemes, the education of farm laborers’ children developed into a pressing issue where Mexican colonies were established in Wyoming. At first, these students, along with the children of other laborers, attended school with the children of local White Americans. However, congressional committee hearing testimony on immigration restrictions called into question the viability of mixing Mexican and White children. At one point, White Wyomingites testified that they had no issues with integration, and one farmer—Jess Crosby—from Cowley testified that “the white people accept [the Mexican children] alright.”Footnote 37

The testimony from the Cowley farmer was not just appeasement to anti-immigration legislators, but seemed to describe the experience of most Mexican children in the sugar beet communities in Wyoming before the Great Depression. The schooling problem produced by the sugar beet industry, however, was on the radar of school officials as early as 1922 when Wyoming passed its first child labor laws.Footnote 38 And as the beet industry expanded throughout the state, so did the educational “problem.” It included irregular school attendance from child laborers, especially those working in the beet fields.Footnote 39 By 1929, responding to the education needs of children working in the sugar beet fields, Wyoming's governor, Frank C. Emerson, ordered the state's Child Labor and Welfare Committee to find a solution to the irregular school attendance of “beet children.”

Between 1929 and 1931, Wyoming school and state officials launched an intrastate campaign to develop an educational policy for its beet children, a policy that centered on their labor class status and not their race and ethnicity. The educational campaign consumed the governor-appointed Child Labor and Welfare Committee led by Grace Raymond Hebard, a University of Wyoming professor and Americanization advocate.Footnote 40 Hebard and the committee focused on creating an educational policy that allowed beet children to “catch-up” and integrate with White American children outside of the sugar beet industry.Footnote 41 As Hebard noted, “In this way, directly or indirectly, the two sets of children come into contact which helps in an educational democracy.”Footnote 42 Here the committee embraced a view of the Mexican and beet child as an “immigrant” child worthy of Americanization at a time when similar movements almost exclusively focused on European immigrants.Footnote 43 The placing of Mexican children in White schools as a form of Americanization was different from other historical accounts that saw segregation in controlled environments where they were Americanized and taught English.Footnote 44 In fact, the issue of English language acquisition was not discussed in Wyoming until after segregation was in place.Footnote 45

Hebard's discussion with the superintendent of Worland schools, C. H. Studebaker, is by far the most vivid indication that educational policy for students of Mexican descent at that time was focused on a form of inclusion rather than racial exclusion. Studebaker and Worland school officials objected to any form of segregation of Mexican, German Russian, or Japanese students. He objected to segregation on economic grounds but most of all believed segregated schools conflicted with Americanization. In his words, “There has been talk here several times of segregating these students [Mexicans], but we school people have always opposed it, first because it would increase our expense, which we can ill afford, and that we feel we would be doing a poor job of Americanizing them in that way.”Footnote 46 In fact, Studebaker's position against segregating Mexicans was also informed by his opinion that Mexicans were academically better students than other beet children, particularly German Russians:

What I have said about the Mexicans applies also to the Russian-German element we have here. Of the two classes though, the Mexicans are the better. Once the Mexican children start school they go through to the end of the year without trouble, while the others are hard to handle, and very irregular in attendance. . . . We have several Mexican students in the upper grades who are very good students. At present there is a part Mexican girl in High School, I believe in the senior class, who is really a brilliant girl.Footnote 47

As Hebard and the committee presented their plan to educationally mainstream both groups throughout the state, they ran into pushback from a source they had not anticipated, German Russian parents. Hebard acknowledged, “We are finding practically no objection from the Mexican parents, but we find objection from the Russians and Germans and hence we feel they are the ones who need it the most.”Footnote 48 Unlike Mexican parents, German Russian parents objected to any educational services or interventions that conflicted with their children working on family-owned farms. Studies of other states found that unlike with Mexican families, it was the German Russian families who kept more of their school-age children in the sugar beet fields, partially because many were tenant farmers or farm owners themselves, which was not the case for Mexicans in the industry.Footnote 49

Figure 2. German Russian, Japanese, Mexican, and White children in pre-segregation elementary classroom photo in Worland, 1932. Image courtesy of Joe Ramirez.

The relationship between German Russians and Mexicans was central in defining whiteness in the sugar beet communities of Wyoming. For instance, Paul S. Taylor, noted economist and pioneering Mexican labor researcher, noted that although European, German Russians were not considered fully White in sugar beet communities:

Another problem arises in the use of the term “white.” It is a mistake to think that because white and Negroes are used as opposing terms, that “white” always refers to color. In northeastern Colorado one encounters the strange popular usage which in its terminology divides the community into three: “whites,” meaning English-speaking Americans or Americanized Europeans; “Mexicans” meaning indiscriminately Mexicans from Old Mexico and Spanish Americans; and “German Russians” (“Russians” or “Rooshians”), who are still a large and sufficiently unassimilated group not to be covered by the term “white.”Footnote 50

In Wyoming, German Russians specifically identified themselves in relation to Mexicans. For instance in 1919, German Russian sugar beet workers refused to share a passenger coach with Mexican workers in Lingle, causing such a protest that representatives of the Great Western Sugar Company intervened.Footnote 51 Only after separate accommodations in town were made for the German Russians did the protest end, while the Mexicans remained in the railroad car.Footnote 52 In Worland, Mexican Americans noted that it was the German Russians who made it a priority for their children to not to play with Mexican children. One woman commented, “Well, when I went to school some of the white kids, most of your Russians, they would tell their kids you know you can't play with them and Mexicans were you know, you just didn't hang around with them.”Footnote 53 However, German Russian families also linked their educational fates to the presence of Mexicans in the sugar beet industry, one German-Russian, Paulina Hahn, acknowledged, “Well, in one way it [the increased use of Mexican labor] was the best thing that ever happened to German Russians, because their children were in school year round.”Footnote 54 In other words, “school was the place German-Russians could be converted from German-Russian immigrants into American citizens.”Footnote 55 Or where German Russians could become White.

Although the Child Labor and Welfare Committee found racial integration to be the norm for Mexican children, it also found that German Russian families increasingly looked to schools to separate themselves from Mexicans. In the summer of 1929, the school board in Torrington, Wyoming, decided to build a new school, the South Torrington School, in its sugar beet factory district.Footnote 56 The new school was built to meet the special educational needs of beet children, specifically those from Mexican and German Russian families.Footnote 57 Before this time, beet children, regardless of race, nationality, or labor status, had attended the city school with all children in a desegregated setting.Footnote 58 Usually beet children were placed in designated classrooms, “opportunity rooms”—designed to integrate them fully into Torrington schools. However, once the new school was built, it was a source of racial tension. Fighting was a constant problem in the school and German Russian parents objected so strenuously to their children mixing with the Mexicans that they withdrew their children from the two-room school.Footnote 59 The German Russian parents threatened to boycott the entire Torrington school system unless they were allowed to attend the city classrooms with the White children. Responding to the parents’ protest, the superintendent, A. H. Dixon, allowed German Russians to reenter the city schools rather than force them to return to the South Torrington School. Consequently, by 1930, the school that was intended to serve all beet children became a “Mexican school.”Footnote 60 The incident in Torrington was an omen for the entire state as the Depression worsened, and Whites and German Russians looked to public schools to clarify and define their racial standing in the state.

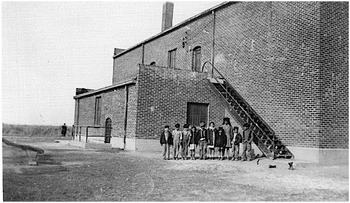

Figure 3. The Mexican School pictured in Torrington newspaper. Source: Torrington Telegram (WY), September 2, 1943, 4.

The Mexican Race and Child in Wyoming on the Eve of the New Deal, 1930–1933

The 1930s can be considered the nadir of race relations for Mexicans in the United States during the twentieth century.Footnote 61 During this decade, the US Census Bureau created, for the first and only time, a racial category for “Mexicans” that set them apart from White Americans.Footnote 62 The 1930s also saw an unprecedented deportation program that targeted Mexicans. This was an issue for Mexicans in sugar beet communities, where many sugar companies and local charity organizations coordinated repatriation to move Mexicans out of depressed areas.Footnote 63 Deportation drives disproportionately focused on Mexicans—regardless of citizenship—because they were racialized and were seen as “welfare dependent.”Footnote 64 Repatriation of Mexicans became so widespread that Mexican communities feared accepting or applying for relief.Footnote 65 The repatriation program eventually deported approximately five hundred thousand Mexicans regardless of citizenship.Footnote 66 As early as 1932, Wyoming newspapers acknowledged the massive repatriation of Mexicans.Footnote 67 Wyoming alone saw almost two-thirds of the local foreign-born Mexican population depart by 1940.Footnote 68 However, Wyoming still had the largest percentage of Mexicans of all Mountain States outside of the Southwest.Footnote 69

In Wyoming, the status of the Mexican child and laborer became increasingly salient as the Depression spread. On February 18, 1931, Governor Frank C. Emerson died, and by the end of the year the Child Labor and Welfare Committee had lost Hebard as its chair.Footnote 70 The collapse of the committee coincided with the increasingly racist tone of many committee members and frustration on the part of many educational leaders regarding how to solve the state's Mexican beet children problem. In its final report on the sugar beet labor problem in Wyoming, the committee offered no viable recommendations on the best means to educate the children of the sugar beet fields.Footnote 71 Beatrice McLeod, Wyoming state director of special education, in one of her last correspondences with Hebard on the Mexican schooling issues, lamented what seemed to be intractable issues and suggested that “further investigation is necessary to determine the educational needs of these children.”Footnote 72 Though the committee came to no definitive conclusions, its members began providing a racial explanation for the issues rather than explaining them in terms of immigrant or labor class status. The end of Emerson's Child Welfare Committee was a devastating blow to the fate of Mexican American children in the state. As observed in the committee's campaign, school and state officials were central in combating calls for racial segregation in Wyoming's public schools. With the committee gone, the educational fate of Mexican children was now left in the hands of communities that held anti-Mexican sentiment.

Correspondence from Thomas Mahony, head of Colorado's Mexican Welfare Committee, to Hebard is a case in point.Footnote 73 Though Colorado sugar beet factories employed German Russians and native White Americans along with Mexicans, he described how Mexicans, in particular, were becoming targets as the economic situation in the state deteriorated. In his last correspondence with Hebard, he predicted Mexican sugar beet workers were in for a “terrible winter.”Footnote 74 In Colorado, the Great Depression exasperated the anti-Mexican sentiment in sugar beet districts already present in the 1920s.Footnote 75 However, Mahony observed an intensification of existing anti-Mexican sentiment in the 1930s, anticipating a larger shift in the relationship between the sugar beet industry and Mexican laborers:

The company and others [sic] seem to be adopting a rather “hard-boiled” attitude towards them. I am receiving many reports of laborers not receiving their pay for the spring work. In a good many instances in addition to this, they are being driven off from ranches. A good many seem to have the idea that because of general unemployment throughout the country they can be rehired for fall work at a price less than the price specified in contract.Footnote 76

The “hard-boiled attitude” Mahony described was not isolated to Colorado but extended to Wyoming. By the end of 1930, the tone in Wyoming began to change as both Hebard and educators throughout Wyoming began to describe the education of Mexican sugar beet students in racial and cultural terms, minimizing the discussion of beet children in general. Nothing displayed the drastic racialization more than one of Hebard's last correspondences regarding the beet children issue with fellow Child Welfare Committee member and future president of the state's Board of Education, J. J. Early:

It looks as if I wore [sic] emergency, temporarily perhaps, in making the preparation for six or seven weeks of special instruction for these children, who even though Mexican and dark skinned are human beings. . . . Not for publication, I would like to say I believe that Wyoming would be economically, socially, and educationally better off today if we had no Mexican laborers within our boundary. There would be a period, of course, of semi-adjustment that might be depressing, but ultimately there would be a standard of living and social equilibrium, which we do not possess now in some localities where there are numerous Mexicans.Footnote 77

The anti-Mexican sentiment and attention to racial characteristics—skin color—was a stark contrast to Hebard's discussion of Mexicans earlier in the educational campaign. The attention to skin—a biological trait—demonstrates that Hebard and her colleagues were transitioning to a racial difference rationale to explain the condition of the Mexican child in Wyoming schools.Footnote 78 Initially, the discussion of educating Mexican beet children centered on their eventual inclusion in the citizenry of Wyoming.Footnote 79 Hebard's faith in that plan collapsed by the end of 1930 as the Great Depression worsened. In its place was a new faith in the racial segregation of Mexican children to solve a schooling problem that was increasingly viewed as a social problem in Wyoming. Before the New Deal, many Wyoming communities began to look for ways to segregate Mexican children just as economic constraints prevented them from doing so.

This change was reflected in areas such as the Torrington School District, where Mexican children continually found themselves shut out of the normal public school system, associated with poverty, and discussed in racialized terms. Juanita Patton, who was now teaching exclusively Mexican children by 1931, discussed the problems of teaching at a segregated school. Patton identified social discrimination as the source of isolation of Mexican children, stating, “A few came to the regular grade school in Torrington, but the White children fought them and called them dirty Mexicans, and the ones that came were not happy.”Footnote 80 She also noted that Mexicans were cut out not only from the school system but from the welfare system in the community; many Mexican children did not attend school because of lack of clothing, shoes, and poor hygiene. In response, school officials had to create a “sort of Red Cross” to assist the Mexican students.Footnote 81 However, Patton's concern for the welfare of Mexican children was not based on a belief in the eventual inclusion of Mexicans into Wyoming society but rather was the product of racial paternalism.Footnote 82 She clearly marked Mexican and White children as opposites, and never discussed Mexicans and German Russians as the same student population, which was not the case before segregation. For instance, when writing to Amy Abbot of the Child Welfare Committee to describe the experience of Mexican students in the South Torrington School, Patton described Mexicans as racially and nationally different than Whites, stating, “Can you put yourself in their place, a lone white child in Mexico?”Footnote 83 Once allowed into White schools, German Russian children ceased to be a named “educational problem,” even though many still worked in the sugar beet fields.Footnote 84

Patton was both a problematic advocate and teacher of Mexican children. Although acknowledging the discrimination faced by Mexicans in Wyoming and noting that Whites commonly referred to Mexicans in the community as just “dirty Mexicans,” many times she also described the Mexican population as “child like,” prone to drunkenness, engaged in wife beating, and unable to manage their finances, effectively making them complicit in their community standing.Footnote 85 More importantly, she never questioned the segregation that emerged in her school, even though she noted that her school's racial segregation emerged out of racial negotiations between German Russian parents and White school officials. Patton was not alone in this analysis—A. H. Dixon, the school superintendent in Torrington, shared this view. In a telling interview of Dixon in 1931, he explained that anti-Mexican sentiment from the German Russian parents was a critical factor in racial segregation in the Torrington schools, particularly the school that German Russian parents had boycotted because their children were placed exclusively with Mexicans.Footnote 86

The German Russian experience in Torrington and the rest of Wyoming is a reminder of the central role of schools in creating race. The final decision on segregation came down to Superintendent Dixon, who allowed German Russians to attend any school of their choice with White children, showcasing the power of school authorities to define race. Once the South Torrington School became segregated, Dixon fully embraced a racial view of education. For instance, when Dixon was interviewed in 1931 by a University of Wyoming student about the school, he observed, “The beautiful part of our system here in Torrington is that the school tries to let the Mexican put himself into his environment and not mold the environment to the Mex [sic].”Footnote 87 As the interview proceeded, Dixon was more specific about the “Mexican environment,” stating:

The Mexicans in this Colony like to be called the Spaniard. They have the clear eye, high forehead, smooth features, etc., but most of them are the offspring from the Indians and are not as high class as the Spanish of this type. However, it should be remembered that these Mexicans are the lowest of the low working classes who live in Mexico.Footnote 88

His view of the German Russian element, especially students, was a striking contrast: “The Russian-Germans are quite regular in school and are in the main trustworthy as well as conscientious about their work.”Footnote 89 Dixon failed to reconcile or explain the placement of German Russian children in the same school with Mexicans in the first place, considering the school was best suited for the Mexican child.Footnote 90 Additionally, the attention to racial attributes and “color” was a marked contrast from his discussion of Mexicans as simply a “foreign element,” as shown in his correspondences with the Wyoming Committee for Child Welfare in 1929.Footnote 91 For Dixon, the Mexican was a racial other distinct from Whites, including the previously racially ambiguous German Russians, and the South Torrington School, now the “Mexican School,” operationalized and fixed this racial view.Footnote 92

Creating the Mexican Race: Segregated Mexican Rooms and Schools in New Deal Wyoming, 1934–1941

The worsening conditions of the sugar beet industry, dire need for relief in sugar beet communities, and the avalanche of protests by Mexican and Mexican American sugar beet workers forced federal intervention. The passage of the 1934 Sugar Act included a minimum wage scale for beet workers and a child labor clause.Footnote 93 The child labor provision caused little protest by sugar beet officials and politicians, who saw their biggest concern as the increasing unionization and radicalization of Mexican workers.Footnote 94 Many viewed the curtailing of Mexican child labor in the sugar beet fields as a pathway toward higher wages for Mexican heads of families, with many arguing said action would lead to “freedom from premature toil in the beet fields and improved opportunities of school attendance for the children, together with higher wages, increased work opportunities, and improved living conditions for their families.”Footnote 95 However, it would be the child labor restrictions implemented in 1935 that would be most impactful. For Wyoming, the 1934 Sugar Act—renewed in 1937—brought the Mexican child and schooling into a racialized New Deal.

With the passage of the federal act, sugar beet growers could not apply for federal loans or assistance if they utilized child labor under fourteen years old.Footnote 96 A survey from the National Child Labor Committee found widespread compliance with the clause in the sugar beet industry, reporting, “Statements by land owners, renters, and laborers indicated that the child labor provisions of the 1935 contracts had been carried out both in the letter and spirit of the law.”Footnote 97 In communities like Lovell, Torrington, and Worland, this had an immediate impact as local newspapers called on growers and the sugar beet industry to comply with the Sugar Act.Footnote 98 According to a 1935 survey by the US Department of Labor's Children's Bureau, the usage of child labor ages six through twelve dropped from 22.5 percent to 7.35 percent in northern Wyoming.Footnote 99 Combined with the issue of relief, the Sugar Act curtailed the prevalence of beet children and increased the presence of Mexican children in the Wyoming schools, an unwelcome addition in many White communities.

As part of the Sugar Act, the Children's Bureau sent a number of agents to sugar beet-producing states to assure that anti-child labor provisions were being observed.Footnote 100 In northern Wyoming—Big Horn, Park, and Washakie Counties—agents found educational neglect of Mexican beet children. In one glaring example, one school district had actively discouraged Mexican children from attending school. The agents discovered that in many communities, the restriction of child labor did not translate into increased enforcement of the state's compulsory attendance laws.Footnote 101 In one case, agents found that in an unnamed Wyoming town, school officials “at their own discretion, refused to admit children who did not enroll in the first 15 days of the school term.”Footnote 102 This policy chiefly affected Mexican children, since many were from migrant families. One Mexican family that permanently resided in the town had to enroll their children almost two years late, with one child entering the first grade at nine years old.Footnote 103 In another community, children from a local Mexican colony were not offered school bus services. In the winter, many Mexican children from the colony had to run as fast as possible to school in an effort to keep from “being thoroughly chilled.”Footnote 104 The 1935 study by the Children's Bureau discovered that race displaced class in public schools. The most common distinction made in the application of school-attendance standards was that of “Whites” and “Mexicans.”Footnote 105

In the wake of the New Deal and the passage of the 1934 Sugar Act, Wyoming witnessed the creation of segregated Mexican rooms and entire schools in sugar beet communities with a noticeable Mexican student population. Although communities adopted different types of segregation, ranging from a segregated grade room to an entire school, segregation was expanded in schools across the state. The explanation of the need for segregation took on an overtly racist tone in some instances, a tone that was at odds with how Mexican students had been described in the past, even as recently as 1929. In Torrington, what was once the South Torrington School for German Russian and Mexican children by 1932 was exclusively for Mexican students and recorded as the “Mexican School” in superintendent reports and newspaper reports.Footnote 106 In Torrington, it was public policy that no children from the Mexican Colony or Mexican District were allowed in the city schools.Footnote 107 In Lovell, a segregated, ungraded classroom named the “Mexican Room” in an official ledger was reserved only for “maladjusted” Mexican children—all Mexican children were considered maladjusted. These children, a paper explained, “are backward because they are unable to speak the English language, and the White children do not accept them into the social life of the school. This condition gives rise to an educational problem.”Footnote 108 In neighboring Powell, officials debated the creation of an entirely separate school based on the same logic, ultimately opting to create a segregated school for the local Mexican children.Footnote 109 Only after population pressures demanded a new school for White students did the Powell school board abandon its plans for a Mexican school, but it continued to maintain a segregated Mexican classroom.Footnote 110 In Basin, the school board actively recruited a teacher for just the Mexican children in the community.Footnote 111 Deaver—a small town of only a hundred with a minor Mexican presence—developed its own segregated Mexican room, despite having only one school for all grades.Footnote 112

Mexican children experienced discrimination even in schools outside the sugar beet districts. In one account from the mining community of Sunrise, a Mexican student recalled that “speaking Spanish was strictly forbidden, and Mexican students were beaten if they strayed into their home language.”Footnote 113 In Worland, an entirely new school was built exclusively for Mexican children with New Deal funds. The school was interchangeably called the Mexican or Spanish School.

The segregated school is Worland is a particularly compelling example, since the city created a separate school for Mexican children, not just a separate classroom. Worland serves as a case study that racial understandings—not demographic, economic, or labor pressures—created and accelerated segregation in the Wyoming schools. Unlike most communities, Worland had successfully weathered both the Depression of the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 114 For Washakie County (where Worland was located), a small county with a diverse farming economy and a sugar beet factory, the 1930s was described as the “construction decade.”Footnote 115 In an early survey of relief conditions in Wyoming, Washakie County was found to rank last in percentage of population on relief in the state. Of this segment, only 2.1 percent were Mexican, but they made up almost 10 percent of the entire county.Footnote 116 Almost 98 percent of all relief families in Washakie County were White.Footnote 117 Unemployment was steady throughout the county, reaching its peak in the winter months, but never exceeding a total of four hundred people unemployed, thus consistently putting the county lowest among the beet-producing counties.Footnote 118 Yet it was in Washakie County where racial segregation in public schools reached its apogee in the state. Such a development is even more interesting considering that in the early 1930s the education of the Mexican child was temporarily in the background of public community concerns.

From 1930 to 1933, there was little to no discussion in the local newspapers or the school board minutes of segregating Mexican students in Worland. In fact, there was no discussion of the beet child problem publicly in the community.Footnote 119 Although there was some discussion about deportations of Mexicans, little was said on the status of educating Mexicans during this period.Footnote 120 For instance, a report from the Mexican consul in Denver, Colorado, found that 14,068 Mexicans were deported back to Mexico from Colorado and Wyoming by 1933, including Worland.Footnote 121 Still, the schooling of the local Mexican American and Mexican children was seemingly a nonissue. Interestingly, in early 1934, the school board minutes indicated there was some protest on the division of the elementary grades into three tracks, because students in the “C” track—the lowest one—felt marginalized.Footnote 122 At that time, all students, regardless of race, were placed in educational divisions based on ability.

This inattention changed during a special roundtable convened at the local Parent Teachers Association meeting in the spring of 1934. The major topic of discussion was constructing a separate school for the “foreign” or “Mexican element” in the community.Footnote 123 German Russians, unlike Mexicans, would attend the “regular” White schools. The special roundtable was headed by elementary school superintendent Frank Watson and included G. C. Muirhead of the governor-appointed and New Deal-funded Wyoming State Planning Commission.Footnote 124 The meeting ended with a yes vote in favor of constructing the segregated school and securing aid from the local sugar factory, the Wyoming Emergency Relief Administration, and other government relief agencies. Muirhead was the one who suggested the school district should apply for relief funds to fund the construction of the segregated school.Footnote 125 The meeting demonstrated the continued collaboration between school officials and the sugar beet industry. For the Mexican community, the continued collusion between White factory owners, state representatives, and White school officials regarding school policy left Mexican children in Wyoming vulnerable to shifting attitudes toward race. After the meeting, the matter of segregation was then presented to the local school board for approval.

During the Worland School Board of Trustees meeting in 1934, Frank Watson once again brought up the matter of a segregated school. “Mr. Watson brought up the matter of a separate school building for foreign children near the foreign settlement,” read the meeting's minutes. “It was thought the matter was worth looking into to see what might be accomplished.”Footnote 126 This suggestion for a segregated school symbolized the rise of race in marking citizenship in Worland. This was particularly true of Watson, considering that, as recently as 1929, he and Worland school officials had opposed segregating Mexican children. The calls for segregating Mexican children grew louder as Worland school officials wrote letters to the chairman of the Wyoming State Planning Board and the Holly Sugar Company factory manager, inquiring about possible assistance in building a separate school for the “non American” students. One letter read, “The Board feels the segregation of this class of pupils in a separate building will be for the good of both classes of students.” The secretary of the school board added, “Knowing the Holly Sugar Corporation has co-operated in other places along this line, the Board asked that the matter be taken up with you and solicit such co-operation here. We have in mind that possibly some Government Relief Agency would co-operate also.”Footnote 127 Worland officials probably thought their chances were quite good given that the Holly Sugar Company had given assistance to the schooling of Mexican children in other towns.Footnote 128 The same school officials also asked the Wyoming Commissioner of Education and Government Relief Agencies for some additional assistance.Footnote 129 The school board opted to apply for federal New Deal funds to construct the new school.

In applying for federal and state aid for the new school, Worland school and city officials deviated from the reasons historically cited for segregating Mexican American children, including their perceived lack of English proficiency, their child labor status, or both, instead opting for a purely racial segregation rationale.Footnote 130 For instance, in their Public Works Administration (PWA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA) funding applications under the “Justification” heading, Worland officials wrote, “That the Mexican children may be segregated from the white children, the project is socially desirable.”Footnote 131 Despite the explicitly racist premise given, Worland's PWA and WPA applications were approved.Footnote 132

In follow-up school board meetings, the “Mexican School” was recorded in official school board minutes.Footnote 133 The naming of the “Mexican School” is significant because it negates a pedagogical basis for segregating Mexican American children and documents a racial reasoning. In a 1974 desegregation case in Oxnard, California, similar language in school board minutes from the 1930s served as evidence in a ruling against the school district. The court ruled that a term such as “Mexican school,” demonstrating segregation in Oxnard, was not voluntary or based on educational standards but racial in nature.Footnote 134

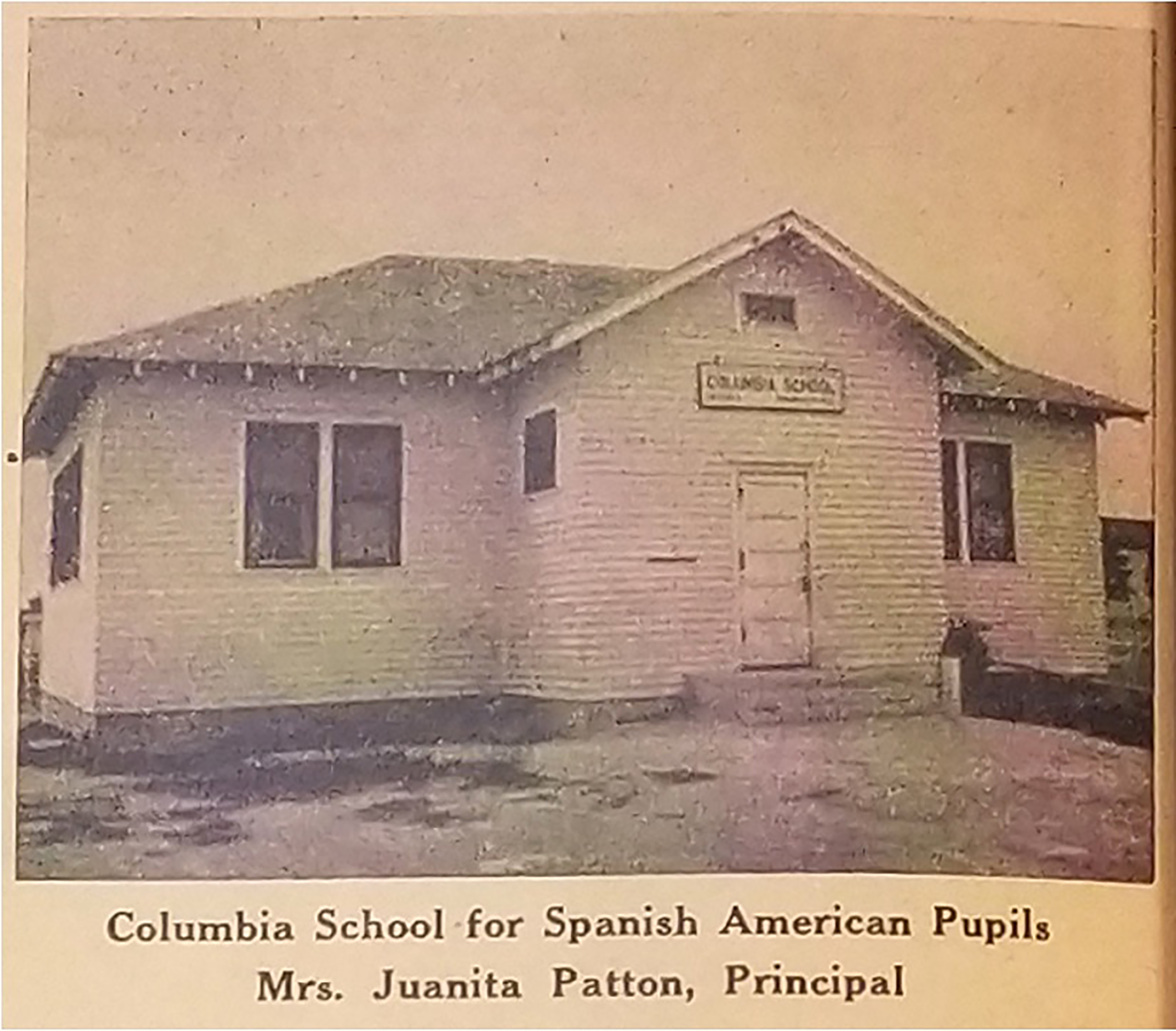

Soon after Worland officials had received federal and state support, they moved quickly to construct the school, which opened in 1936.Footnote 135 Worland represents one of the few cases of federal documentation confirming that New Deal funding was explicitly approved and used to segregate Mexican children in a place where segregation did not exist earlier. The school's construction also violated a Wyoming school law that forbade any distinction or discrimination in public schools “on account of sex, race, or color.”Footnote 136

On the eve of the opening of the segregated school, a front-page article in the newly established Wyoming News justified the new school to the general public as a racial project:

The new grade school in the Mexican Colony, which is being built for the children of the Spanish-speaking people to segregate them from the regular schools, is being rapidly completed. The school will be a model building. . . . It is the intention of the board, as soon as practical, to employ only the best grade teachers of the Spanish race . . . with the ever increasing attendance of more children in the regular schools here it has been impossible to accommodate them and it was decided by the educational board here that by segregating the children of the different race, it would work out more economically and more satisfactory to all concerned. As the Mexican labor is always in demand here in the valley, the children growing up will be developed into the highest class of citizens.Footnote 137

The newspaper never mentioned any pedagogical justifications or that Hebard and Worland's school officials had regarded the segregation of the races in schools as detrimental to developing the “highest class of citizens” as recently as 1929. Additionally, the justification that all children of the “Spanish race” were necessarily segregated was never fully explained, given that Mexican children in the upper grades were allowed to attend the regular schools and were observed as “very good students.”Footnote 138 The attention to the increase in population was ironic considering the overall Mexican population in Wyoming was decreasing.Footnote 139 Thus the response by the White community to schooling the Mexican child was based on a change in racial views and the presence of a more stable Mexican student population. As political scientist Benedict Anderson so aptly demonstrated, sometimes imagined communities are more powerful than real ones.Footnote 140 In this case, the imagined view of the Mexican as a distinct and lesser race than Whites justified racial segregation.

In the winter of 1936, the school was completed, and over one hundred Mexican American children were bussed from their former integrated school to the new segregated Mexican School.Footnote 141 The construction of the Mexican School in Worland in 1936 constituted a drastic policy change from the community that once considered Mexican children a “better class” than German Russians. Worland not only promoted its new Mexican School but openly embraced the new inferior status of the Mexican student. For instance, the major newspapers in the county, the Wyoming News, the Worland Grit, and the Northern Wyoming Daily News, ran a weekly column on “Worland Grade Schools” with a separate “Spanish School” section in a tone almost celebratory in regard to segregation. Also, the Wyoming News reported specifically on news from the Mexican colony in Worland, called “News at the Colony,” celebrating the newly built settlement for the Mexican population, constructed at the same time as the school.Footnote 142 Everything about the school was modern, a product of New Deal relief in action. The school, described as a “fine facility,” was a modern brick school with four rooms and teachers for each of the four grades.Footnote 143 As noted by Worland school officials and WPA reports, “only a few of the best” ever made it to the eighth grade and rarely did any go on to graduate high school.Footnote 144 Thus, racial understanding of Mexican educational achievement was mapped onto the Mexican School, ensuring the underachievement of Mexican children.Footnote 145

The facilities at the Worland Mexican School were in stark contrast to the description of most Mexican schools of the Southwest, characterized as vastly inferior to White schools and having “inadequate resources, poor equipment, and unfit building construction.”Footnote 146 Even studies of Worland from the post-World War II era described the Mexican School as a “fine facility.”Footnote 147 Scholars have debated the rationale of building a segregated school that was modern and, in some cases, more attractive than White schools. Historian Gilbert G. González in his study of Southern California found similar exceptions and argued that this was a deliberate strategy by White school boards. To González the schools were designed as an attempt to make segregated schools more readily acceptable to Mexican parents.Footnote 148 However, educational scholar and Mexican American civil rights leader George I. Sánchez advanced a more insidious justification: it made segregation more permanent.Footnote 149 Illuminating this view was Sánchez's comments regarding the debate over improving segregated Mexican schools versus pursuing full racial integration:

It is exceedingly easy, and therefore particularly dangerous, to want to make the segregated school more efficient and more attractive. Usually, this means that it becomes increasingly difficult to eliminate segregation since the segregated institutions has been made more attractive, more palatable, and sometimes has attained a peculiarly prized prestige. . . . But as I have said in past addresses, the segregated school is a concentration camp—you may gold plate the fence posts and silver plate the bobbed [sic] wire and hang garlands of roses all the way around it, it is still a concentration camp!!Footnote 150

In Worland, the Mexican School was the most modern and newest school in the community, yet no White children ever attended the school. Whereas the architecture and conditions differed from that of most Mexican schools of the era, the emphasis on an Americanization curriculum in a segregated space was the same.Footnote 151 In the Mexican School all instruction was designed to solve an English-language proficiency problem and to teach Mexican children “how to be American,” as alumna Estela Vasquez described.Footnote 152 This was a clear departure from the pre-segregation era, when instruction was focused on remedial education with the final outcome of integration.

Wyoming education officials also made no distinction between the Mexican child and parent during this time. Mexican parents throughout the state were also targeted for Americanization education, illustrating the consolidation of a distinct “Mexican” racial category in Wyoming during the 1930s.Footnote 153 WPA officials observed similar accounts focused on the education of Mexican adults throughout the state, such as in the sugar beet district in Platte County:

It was our privilege to attend at one time the meeting of a class in Platte County where one of our teachers was instructing a group of Mexican beet workers in the rudiments of the English language and business procedure. . . .This appealed greatly to those childlike people from below the border who under the sympathetic instruction given made rapid progress.Footnote 154

Observers described similar classes throughout the state in which the Mexican community was vocal about its appreciation of these courses.Footnote 155 Although Mexicans were not the only group recorded as taking “Americanization” courses, they were the center of such racial descriptors as “childlike” and the assumption that all were foreign-born. Many teachers emphasized the skin color of Mexicans attending night school, with one account from Torrington stating, “There were twenty-three or four men, their dark faces bent over their primers, learning to read and others doing their sums.”Footnote 156 In Worland, adult education for Mexican beet workers was promoted as a relief activity, to assist but not change their status as a beet laborer.Footnote 157

The creation of the Mexican School in Worland not only reverberated through Wyoming but reflected a larger racial project in which Whites throughout the Mountain States were demanding racial segregation. As a researcher from the Children's Bureau noted about the entire Mountain States region, “The public schools in the locales where the Mexicans work . . . are not anxious to receive them [Mexican children] and in many districts do not encourage them to enroll but almost discourage them.”Footnote 158 In Scottsbluff County, Nebraska, one woman observed that, “The prejudice against the Mexican is very great. In Nebraska they house separate schools for the race[s] because the ‘white’ people object to them [Mexicans] attending ‘white schools.’”Footnote 159 An earlier 1924 study of the sugar beet industry in Scottsbluff by the National Committee on Child Labor found segregation to be rare: “Their [Mexican] children attend the public school and only in rare instances are separated from other children into classes or rooms by themselves.”Footnote 160 By the end of 1936 when the Worland Mexican School was open, there were instances of racial segregation of Mexican American and Mexican immigrant children in every Mountain State, effectively constituting separate Mexican and non-Mexican social worlds in relief, medical care, and schooling.Footnote 161 This affirmed the expansion of racial segregation in public schools that was well in place in the Southwest in the 1920s but encompassed almost all of the US West by the end of the 1930s.

The segregation of Mexican children in Wyoming was never about solving an educational problem. It was about race.Footnote 162 For Wyoming's White community, the Mexican School solidified racial boundaries, or as historian David Torres-Rouff aptly argued, “Segregated schools . . . simultaneously functioned as architects of race and as signifiers of Mexican Americans’ subordinate status in the realm of social and political citizenship.”Footnote 163 Some Wyomingites considered it similar to the racism Blacks experienced in the Jim Crow South. For instance, Susie Alamos, an alumna of the Mexican School in Worland, remembers:

We came from a town where they treated you like colored people. . . . In fact, I'll tell you how bad that town was, while we stayed there so long, they built us our own school, they wouldn't let us go with los gabochos [Whites] to school. They did our own school and we had to go to the Mexican school.Footnote 164

White community members like John Davis also remember the segregated experience:

I didn't go to school with a single person of Mexican descent until the sixth grade; they had a separate (but probably not equal) school called the “Spanish school.” We on the east side of the tracks didn't think much about this situation, just seeing it as the way life was lived. Hispanic kids sure did; they were very sensitive to being discriminated against.Footnote 165

These recollections were distinctly different from the public face of the government. In 1941, the WPA travel guide for Wyoming depicted the state as “a land of opportunity . . . where few questions are asked of a newcomer concerning his past or ancestry. It is not altogether rhetoric that man is accepted for what he is and what he can do.”Footnote 166 Such publications portrayed racial segregation in the state's schools as an abnormality of the territorial era, with the rest of narrative barely mentioning Mexican Americans. Such a glowing depiction of the “Equality State” contradicted the lived experience and unpublished WPA material of Mexicans in Wyoming. While one WPA report found that there were fewer “prejudices against Mexicans in certain circles that one would find directed against the negro group,” it also found that “in other communities the prejudice against the Mexicans would be greater than that manifested against the negroes.”Footnote 167 Mexicans and Blacks were interchangeable in the racial hierarchy of Wyoming and they were both targets of racial segregation.Footnote 168 In fact, oral histories indicate that the few Black students who lived in Worland were forced to attend the Mexican School as well.Footnote 169 This association is important given that Black children were the only group ever named in the permissive segregation law of Wyoming.Footnote 170

Figure 4. Mexican children standing in back of segregated school in Worland. Source: T. Joe Sandoval, “A Study of Some Aspects of the Spanish-Speaking Population in Selected Communities in Wyoming” (master's thesis, University of Wyoming, 1946), 85.

At the same time, WPA racial element reports vilified Mexicans for their unwillingness to assimilate and become Americanized.Footnote 171 They depicted German Russians as a group that blended in and were “hard to distinguish from other men and women of the community.”Footnote 172 It was not that Mexicans were unwilling to assimilate; they were not allowed to enter the American mainstream. At one time, Mexicans and German Russian were treated as the same group in educational matters, but by the end of the 1930s, German Russians were distinguished from Mexicans, signaling the Mexicans’ racial standing as non-White. The Japanese were described as a conditional “model minority”—they did not pose a racial problem because they were a small population, they did not marry outside their race, and their children were excellent students.Footnote 173 However, this was not the case for the Mexican populace, who was defined as distinct from all other racial groups and the only group targeted for segregation in the WPA reports.Footnote 174 The WPA reports indicated that the “Mexican or Spanish race” recently had a segregated settlement built for them and also that “plans were being made at present to build a school for the Mexican children, locating it in their own locality.”Footnote 175 The descriptions portrayed the group, in educational terms, as not making much progress in school, and that “not many graduate from High School.”Footnote 176 That so much attention was paid to Mexican differences and their schooling illuminates how schooling was viewed as a race problem not just in this Wyoming community but in the state.

Conclusion

W. E. B. Du Bois discussed the notion of the “Immortal Child” in his first autobiography, Darkwater. He argued that “in the treatment of the child the world foreshadows its own future and faith.”Footnote 177 This observation was not lost on Mexican parents in Wyoming. A 1935 Children's Bureau report that included northern Wyoming noted that Mexicans found the segregation of their children the worst aspect of anti-Mexican sentiment, viewing it as a manifestation of pure race and social discrimination.Footnote 178 Both Du Bois and Mexican parents recognized the distinct place child welfare and, by extension, public schooling played in manifesting racism and the future of race itself.

This analysis of Wyoming demonstrates the role of schools in structuring Whiteness in the absence of laws and legislation. In Wyoming, no laws named Mexicans or Spanish speakers as a specific group of people in any sense. By all measures—naturalization laws, miscegenation laws, education codes—Mexicans were part of the White race. The only institutions that specifically named Mexican or Spanish speakers as a race were public schools and classrooms. Not only did schools and classrooms structure Mexicans as a distinct race but they also associated the Spanish language with immigration and non-Whiteness—despite the fact that many German Russian immigrants did not speak English either, and the fact that most Mexican American children were fluent English speakers. As historian Rosina Lozano has demonstrated, this effectively racialized and nationalized Spanish as a non-US language, bound to Latin America (especially Mexico) and native only to non-Whites.Footnote 179

The experience of Mexican children in Wyoming schools during the Great Depression should complicate the assumption that schools and educational policies were tangential to racial history in the United States. Educational professionals exerted a powerful role in racialization in Wyoming, acting as a substitute for formal Jim Crow laws by being the final decision-makers in the segregation of Mexican children. In some cases, White school officials superseded White parent demands for segregating Mexican children, thus actively creating and maintaining racial integration. In many others, White educators and parents—both European immigrant and US-born—worked together with federal and state assistance to enact segregation.Footnote 180 Ultimately, I found the necessity of expanding the scope of Mexican American educational histories beyond the Southwest and from a racial relational lens.Footnote 181 Wyoming illuminates that almost everywhere Mexican settlement occurred, some form of racial segregation in public schooling followed.Footnote 182 Most importantly, the segregation of Mexican children effectively nullified any claims to Whiteness Mexicans had, making public schools the architects of the “Mexican race.”

Gonzalo Guzmán (gguzman1@colgate.edu) is a visiting assistant professor in foundations of education at Colgate University. His research focuses on the racialization and educational histories of ethnic Mexican communities in the Mountain States and Pacific Northwest of the US. He thanks Rubén Donato, David G. García, and Joy Williamson-Lott for their comments on earlier drafts of this article, as well as the HEQ editors and anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback.