The Russian invasion of Ukraine has increased concerns over military aggression worldwide. Expressing such concerns, Marco Rubio, US senator from Florida, said that the invasion “does not just impact Ukraine, it becomes the model that China, Iran, [and] North Korea will follow.”Footnote 1 Japan's prime minister, Kishida Fumio, also expressed concern about Russian aggression emboldening China toward military coercion of Taiwan.Footnote 2 Similarly, prominent news agencies and policy journals have wondered how Russia's actions influence China's ambitions and speculated that Western reactions to the invasion might deter further military aggression around the globe.Footnote 3

These public debates highlight the possibility that foreign military aggression and international reactions to it could influence domestic political leaders and the public, shaping their opinions on using military force in international affairs. To empirically explore this possibility, our study focuses on the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Chinese public opinion on using military force in general and against Taiwan in particular. Given the current public debate on whether Russian aggression would influence China, this examination is timely and significant. Building on the burgeoning literature on public opinion on the use of force,Footnote 4 we ask: How do the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Western economic and military responses to it influence public support in China for the use of military force?

We identify two sets of determinants of public opinion on the use of force: instrumental considerations that directly concern its costs and benefits; and non-instrumental considerations that are more closely related to normative assessments.Footnote 5 We lay out several theoretical expectations about how each set of factors might shape Chinese public opinion following the Russian invasion and the Western military and economic reactions.

Through two original, preregistered online survey experiments, the first in June 2022 with 4,008 respondents and the second in June 2023 with 3,193 respondents, we show that the Russian invasion leads to a modest but statistically significant increase in Chinese public support for using military force in general and against Taiwan in particular. Causal mediation analyses reveal that both instrumental and non-instrumental factors contribute to these treatment effects. Specifically, the Russian invasion increases the perception that peaceful resolution of conflicts is infeasible and that employing military force can be morally acceptable. Moreover, the invasion amplifies optimism regarding military success, contributing to the support for military force. However, the invasion does not substantially impact the perceived economic and military costs of using military force or heighten perceptions of foreign threats to China among the respondents.

We also investigate the effects of Western military and economic countermeasures against Russia. We find that information on Western military countermeasures curbs the modest effects of Russian aggression, reducing support for using force. In particular, Western military actions reduce support for an outright military invasion of Taiwan, while their impact on support for more subtle military approaches, like military coercion of Taiwan, is negligible. In contrast, Western economic measures penalizing Russia only marginally offset the effect of the invasion.

Our study makes significant contributions to the literature on public opinion on foreign affairs in generalFootnote 6 and more specifically in nondemocracies like China.Footnote 7 While previous research on public opinion on using military force has focused on the influence of domestic factors, potential adversaries, and conflict-specific factors, our study highlights the possibility that military aggression abroad can influence domestic support for using military force. We find evidence for this dynamic in the case of Russian aggression against Ukraine and Chinese public opinion. Our findings point to promising new avenues for future research to see whether similar dynamics emerge in other contexts and the conditions under which they do. We elaborate on these extensions in the conclusion.

Public Support for the Use of Force

Despite the perception that nondemocratic governments like China are unrestricted by public opinion when making policy decisions, a growing body of research in comparative politics and international relations shows that public support can be influential even in nondemocraciesFootnote 8 and that nondemocratic governments invest significant resources in propaganda and censorship to shape public opinion.Footnote 9

In the realm of foreign policy, public opinion on using military force can be important for several reasons. First, even leaders of nondemocracies may incur audience costs from both the political elites and the masses while managing foreign relations, especially in single-party states with civilian leaders, like China.Footnote 10 Research shows that single-party states with civilian leaders behave similarly to their democratic counterparts in handling international conflicts.Footnote 11 For example, Li and Chen, as well as Weiss and Dafoe, find that Chinese leaders suffer public backlash for unpopular foreign policies.Footnote 12 Moreover, decisions to use military force are closely linked to regime legitimacy, and disregarding public opinion on these matters may challenge the foundations of nondemocratic regimes.Footnote 13 In China, for example, international conflicts are closely tied to Chinese nationalism and the legitimacy of the Communist Party.Footnote 14 Such conflicts frequently become the focal point for citizens to rally around and protest, affecting the regime's image and stability.Footnote 15 When US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi disregarded Beijing's warnings and visited Taiwan in August 2022, the Chinese public expressed anger and frustration over the inadequate response from the People's Liberation Army, putting pressure on the party leadership.Footnote 16

Given the domestic constraints Chinese leaders may encounter, one likely channel through which military aggression abroad (such as the Russian invasion) may impact bellicosity at home (such as China's potential aggression against Taiwan) is the former's impact on domestic public opinion. Specifically, the Russian invasion could shape Chinese public opinion on the government's use of force by informing the public about instrumental factors such as the potential costs, benefits, and consequences of using military force and by shaping non-instrumental, normative judgments regarding the use of force.

Instrumental Considerations

Instrumental considerations primarily relate to the perceived costs and benefits of using military force. In democracies, instrumental factors significantly influence public support for deploying the military in foreign affairs.Footnote 17 For instance, Gartner as well as Dill and Schubiger show that increasing the economic and military costs of war (for example, American military casualties) significantly reduces public support for military involvement.Footnote 18 Similarly, a greater perceived likelihood of military success raises the perceived benefits of using force and increases support for it. In nondemocracies, however, studies suggest that instrumental considerations play a lesser role in shaping public opinion. For instance, Weiss and Dafoe find that military costs have no effect on Chinese individuals’ approval of their government's foreign policy decisions.Footnote 19 Similarly, Li and Chen find that fewer than 20 percent of Chinese respondents disapprove of their government's foreign policies due to instrumental reasons, as opposed to over 60 percent for non-instrumental reasons.Footnote 20

We expect the Russian invasion of Ukraine to send mixed signals to the Chinese public regarding the costs and benefits of using military force. On the one hand, Russia has faced severe economic and military costs but failed to achieve complete territorial control or regime change in Ukraine, potentially increasing the perception that using military force is costly and unlikely to succeed. On the other hand, the Russian economy has shown resilience, bolstered by rising oil and gas prices and a relatively stable currency following the initial impact of Western measures, and the Russian Army has occupied most of the Donbas region and several major cities in Eastern Ukraine (at least by June 2023). More importantly, Chinese media tend to emphasize Russia's military and economic strength rather than its vulnerabilities.Footnote 21 Accordingly, we expect information on the Russian invasion to lead to a small yet positive increase in Chinese public support for using military force. We expect the effect to be small because of the mixed information about the costs of conflict in China and the evidence suggesting that citizens in nondemocracies are less responsive to the costs of using military force. We also expect specific information on the Western economic and military measures against Russia to influence instrumental considerations, decreasing public support for using force by decreasing the perceived likelihood of success and increasing the perception that using force is costly.

Another instrumental factor the public can learn from international conflicts is the level of threat from adversaries. A greater sense of threat can raise the perceived benefits of using force. According to Tomz and Weeks, the perception of foreign threats is the strongest mediator between the adversary's regime type and the American public's support for wars.Footnote 22 Similarly, research on China suggests that foreign threats, particularly from the United States, tend to boost hawkishness and reduce willingness to back down.Footnote 23 We expect the Russian invasion to increase the perception of foreign threats among the Chinese public. The Chinese government's propaganda repeatedly emphasizes NATO's eastward expansion as the root cause of the Russian invasion and highlights Russia's “legitimate security concerns.”Footnote 24 Thus, we expect the Russian invasion to increase the perception of Western threat and support for using military force among the Chinese respondents. Information on Western countermeasures against Russia might also augment the public perception of threats from the West and increase support for using force.

Non-instrumental Considerations

Non-instrumental considerations are less directly linked to cost-and-benefit calculations and more closely associated with normative judgments. Research underlines several non-instrumental considerations that can shape public support for military actions: morality, legality, and the feasibility of peaceful resolution.Footnote 25

Morality is a critical predictor of attitudes to using military force in foreign affairs.Footnote 26 Individuals may perceive the use of force as moral and justifiable based on several factors, including adversaries’ regime type and the targeting of civilians versus noncivilians.Footnote 27 We expect morality to play a significant role in shaping Chinese public opinion. Research on China's grand strategy highlights the importance of “righteousness” in using force in Chinese political thought and culture.Footnote 28 A large segment of the Chinese public believes that China is a peace-loving country that never engages in wars unless it is righteous to do so.Footnote 29 One important “righteous” course is the protection of territorial integrity.

In fact, both China and Russia frequently emphasize territorial integrity and historical ownership of certain territories to justify hawkish policies. Putin's rhetoric, claiming Ukraine is part of Russia and denying a separate Ukrainian identity, might reinforce the belief among the Chinese in the righteousness of using military force. According to US State Department briefings and multiple journalistic sources, such Russian rhetoric is dominant in the Chinese media.Footnote 30 Thus, the Russian invasion might bolster the perception that using military force is righteous and justifiable.

A distinct yet closely related non-instrumental consideration is the perceived feasibility of peaceful resolution. When morality or “righteousness” plays a significant role in shaping public opinion on using force, the adversary is perceived as immoral and unrighteous.Footnote 31 This perception can make compromises with the adversary unacceptable and peaceful resolution unlikely. Such pessimistic views of peaceful conflict resolution can bolster support for military force. For example, in conflicts involving historical territorial disputes, the Chinese public is less willing to pursue peaceful conflict resolution and compromise because they see historically owned territories as indivisibleFootnote 32 and territorial wars as righteous. We expect the Russian aggression to lead to pessimistic perceptions of peaceful conflict resolution among the Chinese public. First, if the public perceives Russian aggression as a righteous act for territorial integrity, they are unlikely to envision peaceful resolution. Second, the long-lasting tension between Russia and the West can inform Chinese citizens about the low feasibility of peaceful resolution. Over the past decades, the West and Russia have made significant efforts toward peace, most notably through NATO's Partnership for Peace program and the Minsk Agreements of 2014 and 2015, yet these efforts did not effectively prevent conflict in Ukraine.

A final non-instrumental consideration is the legality of using force.Footnote 33 Many scholars and policymakers have pointed out that Russia has violated Ukraine's territorial integrity and the Charter of the United Nations.Footnote 34 If the Russian invasion prompts respondents to think about potential violations of international law, it may reduce support for using military force. While such reasoning is more likely in democracies,Footnote 35 we can empirically test whether legality plays a role in China.

In summary, we expect the Russian invasion to influence Chinese public support for using force through two sets of mechanisms. First, the invasion can affect instrumental calculations, bolstering public confidence in military success and raising threat perceptions from the West, heightening Chinese hawkishness. But more information on Western economic and military measures against Russia should increase the perceived cost of using force and decrease support for it. Second, the invasion may spur Chinese hawkishness through non-instrumental considerations—the perception that the use of military force is morally justifiable and that conflict resolution is unfeasible.Footnote 36

Experimental Design

We conducted two online survey experiments in China to assess the impact of the Russian invasion on public opinion on using military force—the first in June 2022, shortly after the conflict began, and the second a year later, in June 2023. The second experiment allowed us to assess whether the initial findings depended on the timing of the first experiment.Footnote 37

We recruited 4,008 and 3,193 participants, respectively, for the two surveys. They were recruited from a Chinese online survey platform and then directed to Qualtrics, a US-based website, where they completed the survey anonymously.Footnote 38 We employed a quota sampling strategy to recruit respondents over the age of eighteen from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. The demographic characteristics of our samples are presented in Table A1 in the appendix. Both men and women, various age groups, and all major geographical regions were adequately represented. Although our respondents had higher education levels than the general population, highly educated individuals tend to be more politically active, making them more likely to influence foreign policy. Thus, they are a particularly relevant group for our study. We also checked that our results remain substantially unchanged even after adjusting weights to match our target population—specifically, the population of internet users in China (Tables B1 and B2 in the appendix).

Both surveys began by gathering information on respondents’ demographic characteristics and political predispositions. Next, we presented an excerpt from an actual news report from Xinhua News Agency, a Chinese state-affiliated media organization.Footnote 39 We randomly assigned participants to one of four groups, with three treatment groups, each seeing a different excerpt on the Russian invasion of Ukraine.Footnote 40 Our baseline (control) group saw an excerpt about a Chinese festival reported at the same time as the other excerpts. This emulates the “selective-history design” previously used in surveys of Chinese public opinion on military force.Footnote 41

The first treatment groups in both surveys saw a vignette on the Russian invasion. In Experiment 1, they read this:

Russian President Putin declared the commencement of a specialized military operation in Ukraine. Presently, armed conflicts between the Russian and Ukrainian armies are ongoing within Ukraine. The two nations’ governments have not yet arrived at an agreement on how to resolve the military conflict and have not reached a consensus on Ukraine's political status.

In Experiment 2, they read this:

A series of recent developments in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine have garnered significant attention. While the war is still at a stalemate, both Russia and Ukraine have regularly been attacking each other. In Ukraine, in the early hours of the 16th, local time, reporters from Xinhua News Agency heard countless explosions in the capital, Kyiv. Ukrainian officials said that Russia carried out an exceptionally intensive air strike on Kyiv that day, and the Ukrainian air defense system was intercepting the missiles.

We maintained the original wording of the news reports to replicate the information environment in China. The other two treatment groups in each experiment received the same information on the Russian invasion as the first group, plus details on Western countermeasures. That is, in both experiments, the second treatment group saw information on the Western economic measures in response to the invasion, while the third treatment group saw information on the Western military measures in response to the invasion. We present the vignettes in Appendix D.

Following the vignettes, we measured respondents’ support for their government's use of force in general and against Taiwan in particular. First, we asked whether they thought China should rely more on military strength to achieve its foreign policy objectives, a question taken directly from previous surveys conducted in China.Footnote 42 Second, we asked whether China should rely more on military force to “reunify” Taiwan, which allows us to empirically assess how the Russian invasion affects the Chinese calculus regarding Taiwan.Footnote 43

The phrase “using military force to reunify Taiwan” can be interpreted in various ways, including waging a unification war against Taiwan or applying military pressure to coerce Taiwan into accepting reunification.Footnote 44 Therefore, in Experiment 2, we ask more detailed questions about Taiwan. We directly borrow from Liu and Li and ask for respondents’ approval of (1) outright invasion of Taiwan, (2) military coercion of Taiwan,Footnote 45 (3) economic sanction and coercion of Taiwan, (4) maintaining the status quo, and (5) keeping the separate political systems, with unification not necessarily being the endgame.Footnote 46

We examine both instrumental and non-instrumental mechanisms through which the treatments can influence Chinese public opinion. For instrumental calculations, we assess the role of perceived threats to China, perceived economic and military costs, and perceived likelihood of military success. We also examine the role of non-instrumental considerations, including the perceived morality, legality, and feasibility of peaceful resolution. The wording of all questions is presented in Appendix E.

Results

Main Findings

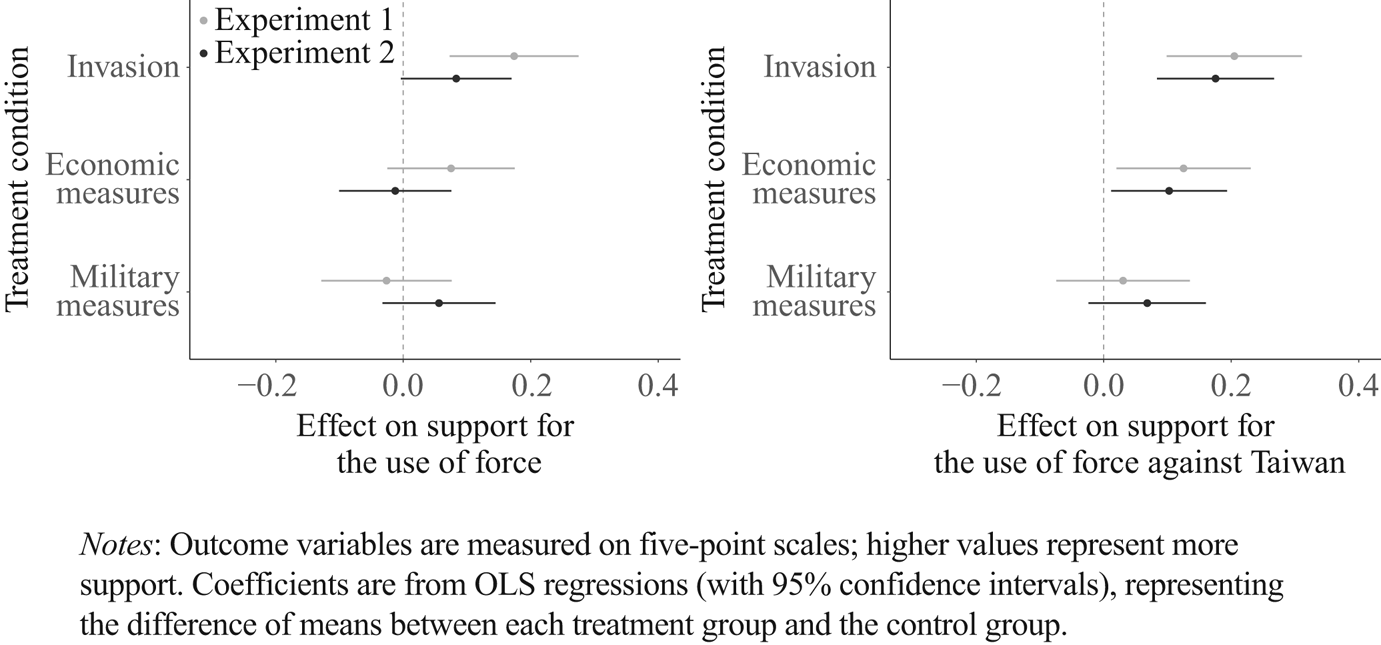

Figure 1 presents the main findings on public support for using military force in general (left) and against Taiwan in particular (right). Each treatment group is compared to the control group exposed to the festival vignette. The plots display the mean differences for each outcome variable, along with their corresponding 95 percent confidence intervals.

FIGURE 1. Effect of each treatment condition on support for the use of force in general (left) and against Taiwan (right)

The invasion treatment leads to a modest increase in support for using military force in general. In Experiment 1, it is 0.17 higher (on a five-point scale) than in the control group, with an adjusted p-value (adj-p) (correcting for multiple hypothesis testingFootnote 47) of 0.0024. In Experiment 2, the coefficient is smaller (an increase of 0.08) and not statistically significant (after correcting for multiple hypothesis testing). The invasion treatment more consistently induces a statistically significant increase in support for using military force against Taiwan specifically, with an increase of 0.21 (adj-p = 0.0007) in Experiment 1 and 0.18 (adj-p = 0.0024) in Experiment 2.Footnote 48

To provide an intuitive interpretation of the treatment effects, we created two binary outcome variables measuring support for using force in general and against Taiwan in particular, with 1 for “somewhat support” or “strongly support” and 0 otherwise. In Experiment 1, slightly less than half of the control group supported using force, both in general and against Taiwan in particular. Following exposure to the Russian invasion vignette, this proportion increased by more than eight percentage points over the control group (adj-p = 0.0017 for both outcomes). In Experiment 2, around 57 percent of the control group supported using force in general and against Taiwan in particular. Compared to Experiment 1, the treatment effect for using force in general is smaller and cannot be statistically distinguished from zero (a 3.9-point increase, adj-p = 0.25) but remains of a similar magnitude for the use of force against Taiwan (an 8.1-point increase, adj-p = 0.015).Footnote 49 Overall, the invasion treatment led to a modest but non-negligible increase in public support for using military force.

We turn now to the effects of information on Western economic and military measures against Russia. The information on economic measures reduced the initial increase in support for the general use of force (middle bars in Figure 1, left), but respondents still maintained higher support (compared to the control group) for using force against Taiwan specifically (middle bars in Figure 1, right). In contrast, for the information on military measures, the initial increase in support for using force (either in general or against Taiwan) cannot be statistically distinguished from zero (bottom bars in Figure 1). Overall, these findings suggest that information on military countermeasures may be more effective than economic countermeasures in curbing the emboldening effects of the Russian invasion.

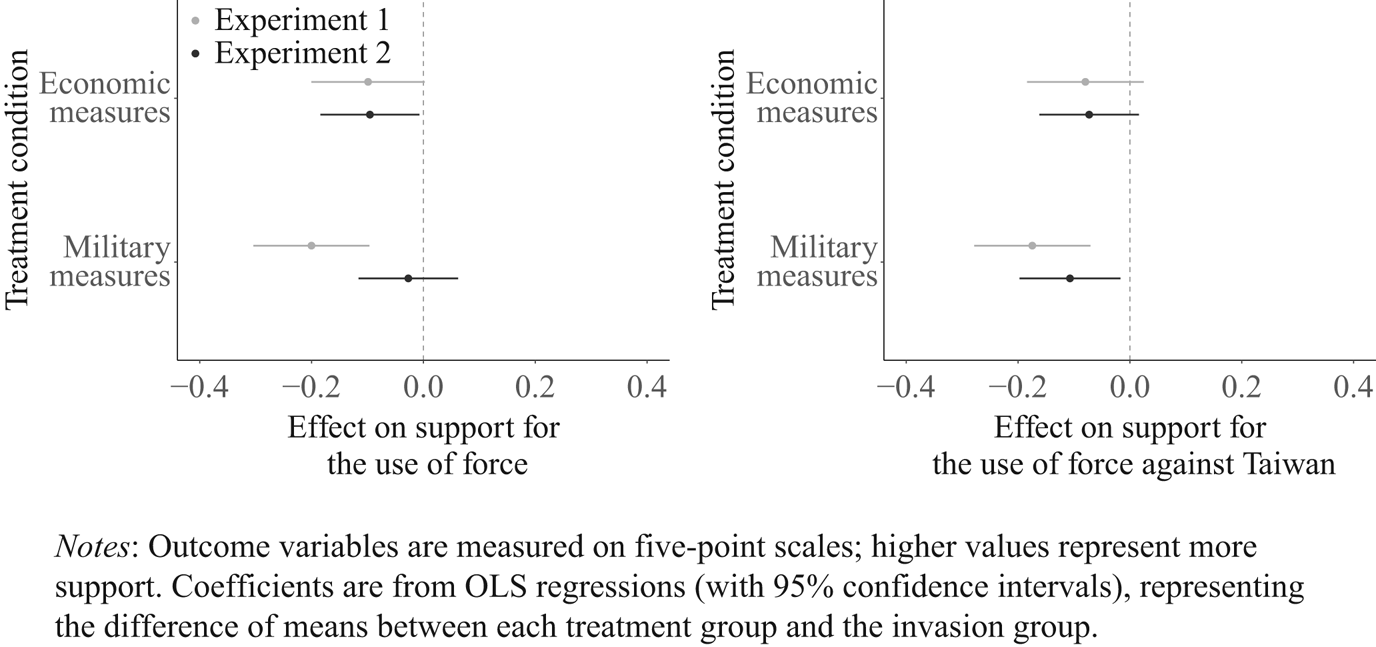

To further illustrate the effect of Western countermeasures, Figure 2 shows results using the invasion treatment group as the baseline. Economic measures weakly mitigate the effect of the Russian invasion for general use of force (a 0.10 decrease) and against Taiwan in particular (a 0.07 decrease). However, in both cases, such mitigation cannot be statistically distinguished from zero after correcting for multiple hypothesis testing. Information on military measures diminishes support for the general use of force only in Experiment 1 (a 0.20 decrease, adj-p = 0.0007) but reduces support for using force against Taiwan in both experiments (a 0.18 decrease with adj-p = 0.0024 in Experiment 1, and a 0.11 decrease with adj-p = 0.06 in Experiment 2). Overall, these results suggest that information on military measures limits the bolstering impact of the invasion on support for using force.

FIGURE 2. Effect of each treatment condition vis-à-vis the invasion treatment on support for use of force in general (left) and against Taiwan (right)

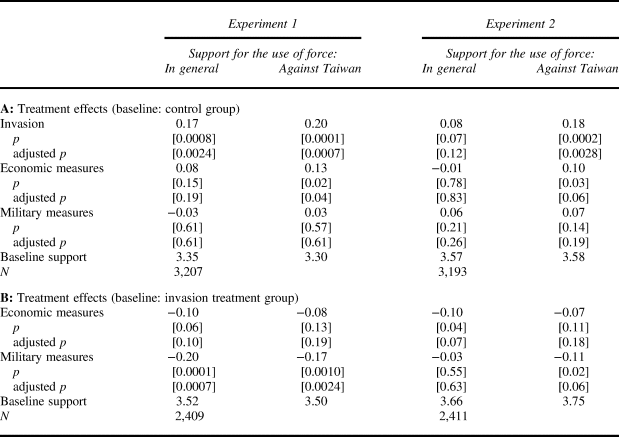

We summarize the main results in Table 1. Panel A shows treatment effects when the baseline group is the control group. Panel B shows treatment effects when the baseline group is the invasion treatment group.

TABLE 1. Summary of the main results

Notes: Outcome variables are measured on five-point scales; higher values represent more support. Coefficients represent the difference of means between each treatment group and the baseline group. P-values and adjusted p-values, using the Benjamini-Hochberg method, are in brackets. Table B3 in the appendix confirms these findings using Bonferroni's family-wise error rate correction instead.

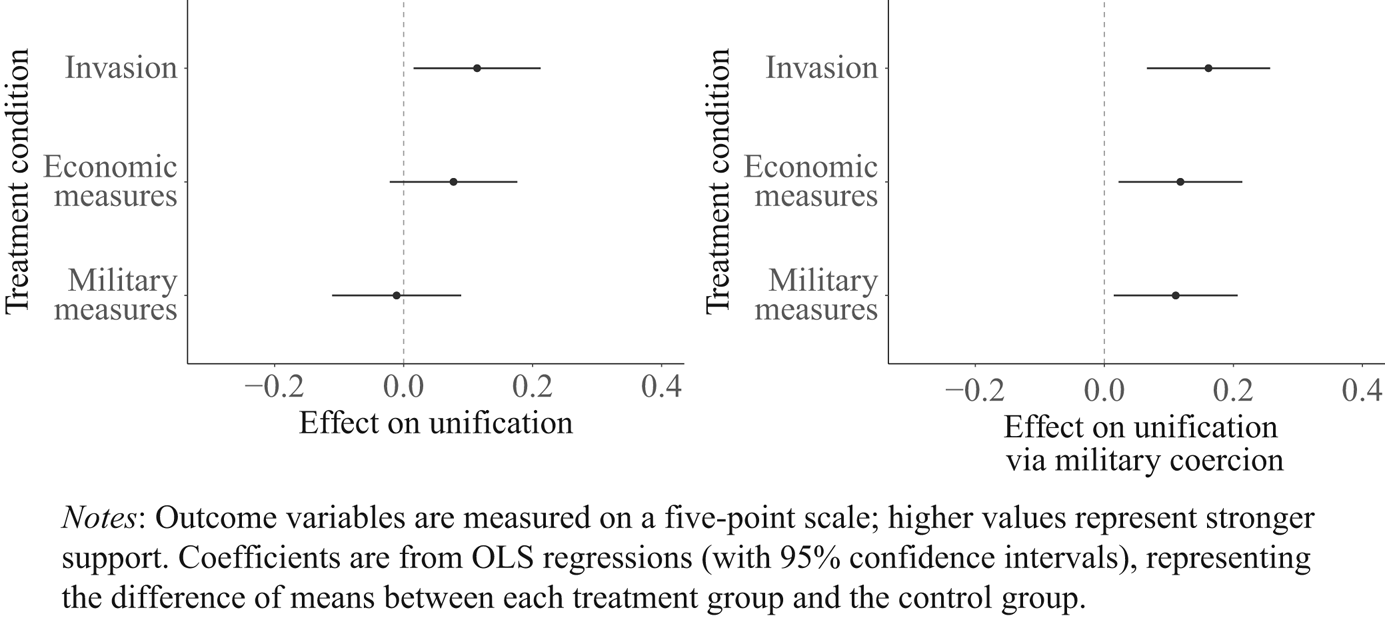

Next, we examine how the Russian invasion and the subsequent countermeasures influence endorsements of particular ways of using military force against Taiwan in Experiment 2. Consistent with the findings of Liu and Li, slightly over half of our respondents express support for both outright invasion (58 percent) and military coercion (53 percent).Footnote 50 The invasion treatment leads to a modest increase in support for both war and military coercion (Figure 3), with a slightly larger effect on coercion (a 0.16 increase on a five-point scale, adj-p = 0.009) than war (a 0.11 increase on a five-point scale, adj-p = 0.06). Moreover, these modest treatment effects persist after we provide additional information about the Western economic (0.12 increase, adj-p = 0.06) and military countermeasures (0.11 increase, adj-p = 0.06). In contrast, support for an outright reunification war cannot be statistically distinguished from zero after that information is presented. Thus, military measures appear to be more effective in mitigating the invasion's boost in support for an outright invasion of Taiwan.Footnote 51

FIGURE 3. Effect of each treatment condition (Experiment 2) on support for Taiwan's unification via war (left) and via military coercion (right)

There are two concerns we would like to address here. The first is potential noncompliance. Due to Chinese respondents’ potential real-life exposure to information on the Russian invasion, our vignettes may fail to elicit beliefs among some respondents, attenuating the treatment effects.Footnote 52 To partly address this concern, in Experiment 2, we use news excerpts reported only days before the survey, increasing the likelihood that the vignettes provide new and current information. Nevertheless, our estimates can be interpreted as intent-to-treat effects, providing conservative measures of the complier average causal effect—that is, the treatment effect on those responsive to manipulation. Intent-to-treat effects do not require additional assumptions for identification and offer valuable insights into the relationship of interest. Since our second experiment largely replicates the initial findings, we are confident that the patterns are not spurious but represent evidence for a modest but statistically significant increase in hawkishness following exposure to information on the invasion.

The second concern is the potential for positive emotions elicited by the festival vignette in the control group. In constructing this vignette, we aimed to control the priming of state media and avoid information related to invasion, military, and war. However, it could have triggered positive and peaceful emotions (such as love, happiness, or calm) to create a “feel-good” treatment group which establishes a different baseline than a neutral control group. In Appendix C, we show that as long as the proportion of “feel-good” individuals is not too large (more than half), our main findings are likely to be driven by individuals for whom it acts as a neutral message. We also show that our main conclusions are unaltered when accounting for pretreatment covariates such as age, gender, education, and income, which have been identified as strong predictors of positive emotions.Footnote 53 Nevertheless, given our inability to directly observe whether a respondent exposed to the festival vignette experiences a “feel-good” reaction or a more neutral one, we acknowledge this as a source of potential bias when interpreting our findings.

Mechanisms

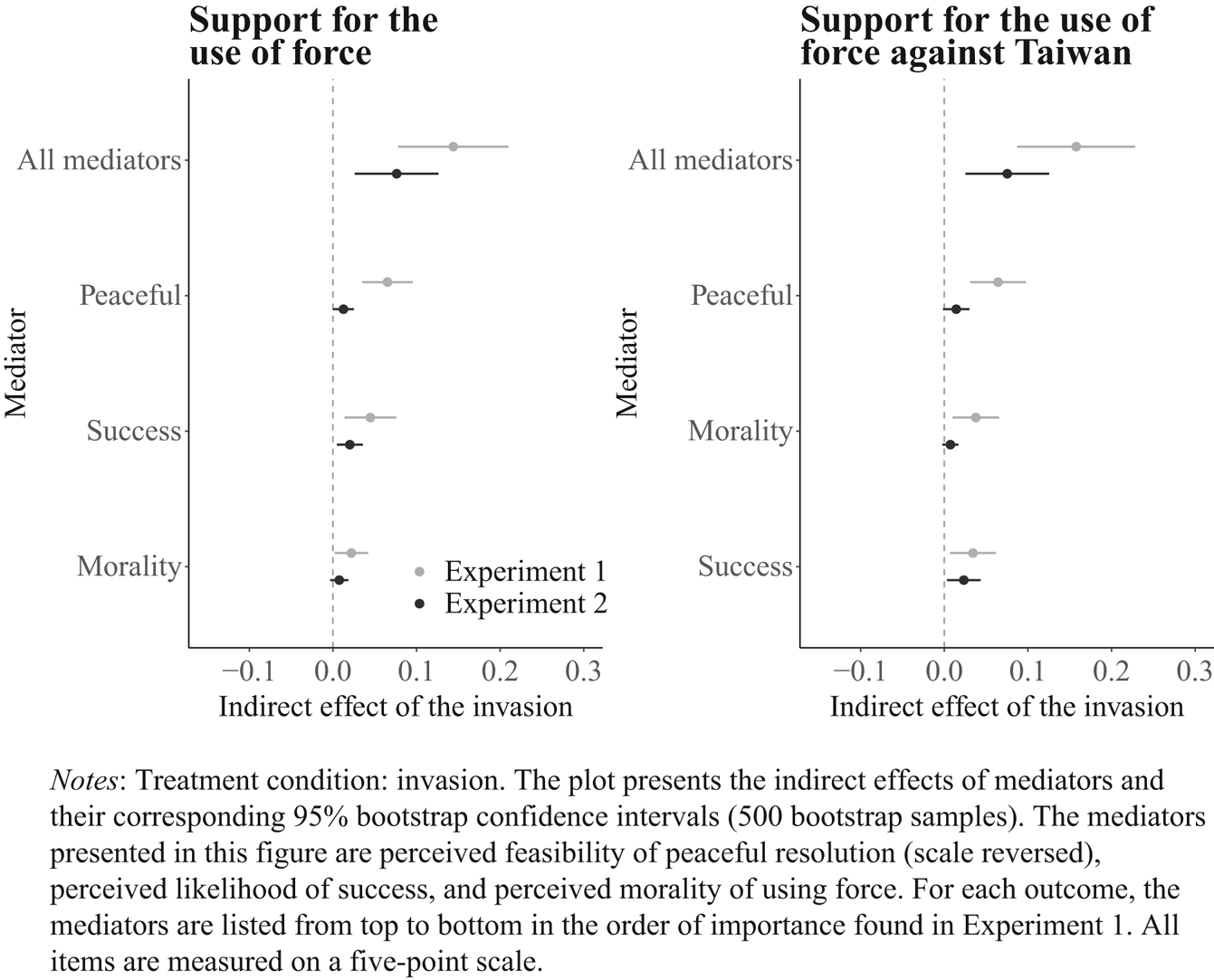

Why does the Russian invasion result in a modest but statistically significant increase in Chinese hawkishness? To answer this question, we examine the direct and indirect effects of the invasion treatment.Footnote 54 We adopt the causal mediation framework that allows for multiple mediators to contribute concurrently to the indirect effect of the treatment.Footnote 55 Figure 4 presents the indirect effect (horizontal axis) of the invasion treatment on the support for the use of force in general (left) and against Taiwan in particular (right). On the vertical axis, we list the mediators that explain most of the variation in the indirect effect (from top to bottom): all mediators combined; perceived feasibility of peaceful resolution (scale reversed);Footnote 56 perceived likelihood of success; and perceived morality of using force. Figures B7 and B9 in the appendix present the mediation analysis for all treatment conditions and mediators.

FIGURE 4. Mediation analysis of support for use of force in general (left) and against Taiwan (right)

Overall, the first experiment exhibited larger mediation effects than the second. In Experiment 1, non-instrumental factors explained about 50 percent of the total effect of the invasion treatment on both outcomes. The perceived feasibility of peaceful resolution and the perceived morality of using military force were the most influential. However, in Experiment 2, the mediation effect through non-instrumental factors shrank to approximately 25 percent and 12 percent of the total impact of the invasion treatment on the general use of force and against Taiwan, respectively. We also do not find evidence for effects from the additional non-instrumental factors included in Experiment 2, including perceived legality.

Furthermore, the Russian invasion consistently leads to modest boosts of public confidence in the likelihood of military success (Figure 4). In Experiment 1, perceived likelihood of success ranked second in importance among all mediators, after perceived feasibility of peaceful resolution, accounting for approximately 20 percent of the total effect of the invasion treatment. The second experiment reaffirms this finding, indicating that perceived likelihood of success is equally, if not more, influential than the combined effects of perceived feasibility of peaceful resolution and perceived morality. Other instrumental factors like perceived economic and military costs play negligible roles, explaining less than 5 percent of the total effect in both experiments.Footnote 57

Overall, the mediation analysis points to both instrumental and non-instrumental considerations. In terms of non-instrumental factors, our findings align with previous evidence that citizens in China tend to perceive international conflicts through the lens of “righteousness” and justifiability.Footnote 58 The pro-Russian information environment in China, as reported by recent scholarly research,Footnote 59 the State Department, and major news sources,Footnote 60 might be presenting the Russian invasion to our Chinese respondents as a highly justifiable instance of military aggression, influencing their thought processes in favor of using military force to achieve righteous political goals.

The close connection between China's international conflicts and its historical territorial claims, nationalism, and irredentism may further explain why the perceived feasibility of peaceful resolution and the perceived morality of wars are among the most influential mediators.Footnote 61 The frequent exposure of the Chinese public to Russia's war propaganda, which denies Ukraine's statehood and distinct national identity, is likely to heighten this connection. This narrative is similar to the one China uses in its international disputes, such as those regarding Taiwan, Diaoyu/Senkaku Island, and the South China Sea. The Russian invasion might have reinforced the belief among the Chinese public that peaceful negotiation is less effective and feasible, and that using force is a justifiable option. Furthermore, the failure of the NATO Partnership for Peace program and the Minsk agreements might have undermined the confidence of Chinese citizens in peace agreements with the West.

Regarding instrumental considerations, our findings suggest that Chinese respondents place greater weight on the likelihood of military success than on the military and economic costs of using force. These findings align with previous research conducted in authoritarian regimes, which indicates that individuals in such regimes are less sensitive to costs but more focused on the potential to achieve favorable outcomes through the use of military might.Footnote 62

The persistence from 2022 to 2023 of Chinese respondents’ optimism about the likelihood of military success is puzzling. However, this might be due to the media environment in China offering positive evaluations of the Russian Army's performance.Footnote 63 Across all experimental groups in Experiment 2, Chinese respondents rated the Russian Army highly, at an average of 7.4 out of 10, and about 35 percent of respondents said that the Russian Army's performance exceeded their expectations, while less than 20 percent said it underperformed. Despite the battlefield stalemate, the Russian invasion seems to have increased the perception that military force can bring success. Another possible explanation for this finding is that the Russian invasion boosted the belief that China would be successful militarily, particularly against Taiwan, while the West is preoccupied with the conflicts in Europe.

Conclusion

This study is motivated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent public debates on whether international military aggression can shape public opinion on military force in other countries observing the aggression. We conducted two online survey experiments in China to see whether the Russian invasion boosted Chinese hawkishness, a timely and crucial case. We find that reminders of the Russian invasion lead Chinese respondents to exhibit a modest but non-negligible increase in support for using military force in general and against Taiwan in particular. Moreover, we find that information on Western military countermeasures against Russia might be more effective than information on economic countermeasures in limiting the emboldening effect of the Russian invasion.

Causal mediation analyses indicate that the bellicosity is driven by a combination of non-instrumental considerations, such as pessimism regarding peaceful conflict resolution, and instrumental considerations, such as optimism regarding the likelihood of military success. In contrast, we find no evidence that perceived military and economic costs, perceived foreign threats to China, or the legality of using force significantly influence Chinese public opinion. These results partly align with previous research, which highlights the effect of non-instrumental factors, such as whether military conflicts are perceived as moral and justifiable, on foreign policy decisions within authoritarian regimes like China.Footnote 64

As of December 2023, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is ongoing, which is a starkly different outcome than initially expected by most observers at the outset of the war, in late February 2022. As the conflict has dragged on and Russia has faced challenges in taking and holding territory, its downstream influence on Chinese public opinion might have changed. To assess the impact of ongoing events in the war, we conducted our experiment twice: in June 2022 and in June 2023. Interestingly, the course of the conflict had little effect on Chinese public opinion: our findings remain largely consistent across the two experiments.

Our study points to a novel source of determinants of public opinion on the use of force and paves the way for promising future research directions. We focus on one of the most significant contemporary international conflicts, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and provide systematic evidence that international military aggression can influence public opinion in another country on the use of force. Beyond the China context, we believe that similar experiments in other countries can help us assess the extent to which Russian aggression bolsters support for military aggression globally. More importantly, further research can examine whether the effect of international military aggression on public opinion in observer countries depends on factors such as the aggressor's regime type, the similarity between the aggressor and observer country regimes, or their alliance ties. Overall, our study demonstrates that the impact of international military aggression on domestic public opinion on the use of force is a promising area of future research.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this research note may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ALRWOJ>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818324000043>.

Acknowledgments

The authors contributed equally to the research. Author names are listed alphabetically. We thank the participants at the International Relations seminar at Washington University in St. Louis and the 57th North American Meeting of the Peace Science Society (International) for their helpful comments.

Funding

We are grateful for the financial support from the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy at Washington University in St. Louis.