Introduction

In the second half of the nineteenth century, labour relations in Ottoman forestry underwent a substantial transformation. The expansion of market relations in forestry and agriculture created new confrontations between forestry labourers and timber merchants, officials, and landowners. This article provides an analysis of these confrontations through the struggles and adaptation strategies of a group of forestry labourers known as the Tahtacı, a semi-nomadic community specialized in lumbering in the forests of Mediterranean Anatolia.

For a long time, studies on nomadic adaptations were limited to archival and field research on pastoral nomads. Such studies tended to overlook spatially mobile craftspeople, traders, entertainers, and peddlers, who were either ignored or considered “social anomalies” or “aberrant cases”, even though these groups constituted an integral part of rural life.Footnote 1 From the end of the 1970s onwards, anthropologists extended the concept of nomadism to include subsistence practices beyond the traditional pastoral and hunter-gatherer strategies. They unearthed the adaptation strategies of peripatetics, a term referring to mobile groups selling specialized goods or services, such as basket makers, sieve makers, tinkers, and blacksmiths.Footnote 2

Despite this inspiring literature, peripatetic adaptations have received scant attention from historians of the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 3 In Ottoman historiography, research on nomadic adaptations is restricted to analyses of pastoral strategies,Footnote 4 even though peripatetics were significant in the countryside since the products and services they provided were vital for other nomadic groups and sedentary people living in towns and villages. Likewise, the literature on artisans concentrates on settled craftspeople organized into formal networks.Footnote 5 Nomadic craftspeople and service providers lacking these networks are either invisible or only problematized with respect to their ethnic identity rather than their extensive links with their environment.

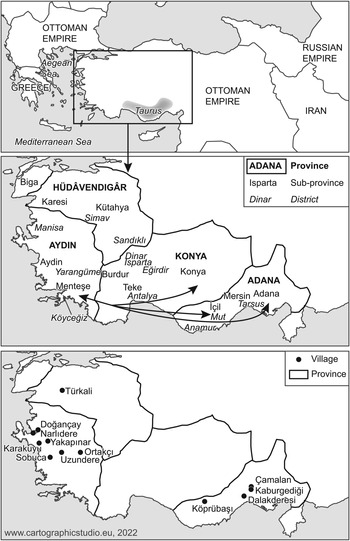

This tendency is probably best reflected in the literature on the Tahtacı. Occasionally cultivating and stockbreeding, these peripatetic hill communities were specialized in cutting, processing, and transporting trees. For at least five centuries, communities widely referred to as the Tahtacı (literally “woodcutters”, denoting the economic activity they were known for), trod the forest-covered highlands and the fringes of Mediterranean Anatolia to source wood, timber, charcoal, bark, and other forest products to be used by the state, sold to the local population, or exported to other regions by timber merchants.Footnote 6 According to an official report from 1918, their total population was approximately 150,000. From the northernmost Aegean region of Anatolia to the Binboğa plateau in Maraş, Tahtacı communities were scattered throughout the chains of valleys and forests in the provinces of Hüdâvendigâr, Aydın, Konya, and Adana. However, most of the population was concentrated in the sub-provinces of Isparta, Antalya, İçil, and Mersin.Footnote 7

Despite the many studies on the Tahtacı, the literature has seldom focused on their lived experience and everyday practices, such as their struggles and interactions with other groups, the subsistence strategies that shaped their culture, and their concrete contributions to local and regional economies. Instead, the literature is centred on the ethnic and religious origin of the Tahtacı, which remains a matter of contentious debate. Western missionaries, travellers, historians, and anthropologists who visited Anatolia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries argued that they were descended from pre-Greek Anatolian cultures, or were Crypto-Christians that had been forcibly Islamized.Footnote 8 Turkish nationalists, on the other hand, have regarded the Tahtacı as an authentic, Central Asian Turkish clan.Footnote 9

The debates on the ethnicity and religious practices of the Tahtacı mainly focus on the continuities and establish a causal relationship between their isolated way of life and their cultural pureness. Luschan, for example, argued that the Tahtacı in Lycia were a self-sufficient community that pursued an isolated life in high mountains, had not mixed with other peoples, and had therefore been able to preserve their Hittite features for more than 3,000 years.Footnote 10 The main assertion of the nationalists of the early Republican period – which remains the dominant reading in the historiography on the Tahtacı – was that, as a result of their closed way of life, and unlike other Turkish communities that had degenerated by mingling and mixing with other ethnic groups, the Tahtacı had managed to preserve their Central Asian roots, their Turkmen tribal traditions, and their shamanist, homeland religion by hiding it for centuries like a “divine mystery”.Footnote 11

The common assertion that the Tahtacı have a traceable, distinct origin stems from the belief that these hill communities had no interaction with their social environment, giving rise to stable cultural practices. Tahtacı communities, however, were more adaptive than is often thought. Like other peripatetic groups, their networks and ability to adapt to rapidly changing ecological, economic, and political conditions made it possible for them to earn their livelihood.

By tracing these adaptation strategies through archival material and oral histories, this article aims to demonstrate the potential of carrying the historical narratives on these communities beyond dominant, ethnonational fixations. Inspired by the ethnographical studies and historiographical debates on upland societies, it is also intended to highlight the limits of considering the livelihood strategies of the hill communities through the lens of a lowland–highland dichotomy.Footnote 12 The complicated interactions of the Tahtacı with timber merchants, officials, and peasants reveal the blurry boundaries between highlands and lowlands.

In drawing attention to these vague categories and uncovering complicated interactions in the triad of the forestry labourers, members of the Ottoman bureaucracy, and timber merchants, this article also seeks to emphasize the role of local actors in the introduction of modern commercial forestry. In the Ottoman context, timber merchants took a leading part in disciplining forest labour. From the 1850s on, commercial networks gradually permeated the remote forests of the highlands, which remained impenetrable for the administration for a few more decades. This process brought about more dependent forest labour, which was not only a prerequisite for profit maximization by timber merchants, but also for the “rational” exploitation of natural resources from the viewpoint of modern forest administration. Tahtacı communities’ valuable, cheap labour and localized knowledge of tree species, cutting seasons, forests, paths, and waterwaysFootnote 13 were vital for the constant supply of forest products for commercial purposes. Not only the technical knowledge (techne) of scientific foresters, but also the practical skills (metis) of the Tahtacı and their ability to adapt to constantly changing environments had to be utilized in line with the goals of bureaucratized, commercial forestry.Footnote 14

To contextualize the interaction of the Tahtacı with administrative and commercial actors, the discussion is divided into two parts dealing with two interrelated issues. The first part describes how the commodification of forests changed the subsistence strategies of the Tahtacı. It demonstrates that, in parallel with the rise of commercial forestry in the mid-nineteenth century and even in the absence of aggressive government efforts to penetrate the mountains, lowland dynamics, mainly administrative and trade networks, managed to leak into the highlands. Tahtacı communities developed novel strategies to cope with the impositions of these networks. In the mid-nineteenth century, some Tahtacı groups overwhelmed by the arbitrary debts imposed by contractor merchants found the opportunity to escape their debt bondage by migrating to other active production areas. In the 1870s, when they became subject to mandatory military service, many Tahtacı men strove to have their exemption continued by drawing on the common perception of them as “Gypsies”, thereby seeking to leverage this label in their favour. Nearly three decades later, some Tahtacı obtained Iranian passports for the same purpose.

The second part addresses the impact of the commercialization of agriculture on the Tahtacı communities’ livelihood practices. As a consequence of the increased agricultural productivity following the retreat of the Little Ice Age and the trend of rising demand for wheat and cotton, the Mediterranean region became a prominent commercial centre. As a result, the plains were reopened to cultivation and the need for agricultural labour increased. Not due to administrative pressure from the lowlands but as an adaptation strategy to the rise of export-oriented agriculture, Tahtacı communities adopted a less mobile life at lower altitudes, where they intentionally engaged in closer interaction with lowland communities.

Commodification of Forests, Bonding of Labour: Debt Burden and Migration

In the nineteenth century, the shipbuilding, mining, and construction industries – not to mention the development of public works, especially investments in communications and transportation facilities – spurred increasing demand from the Ottoman provinces and Europe for Anatolian timber as well as non-timber forest products.Footnote 15 From the 1830s onwards, Greek merchants formed new commercial networks linking Anatolia, Egypt, and the islands of the Mediterranean Sea.Footnote 16 One of the products that entered these networks was timber obtained from the Taurus Mountain chain, a forested region known for its strategic importance due to its proximity to trade routes and networks and for the hardness and durability of its trees.Footnote 17 Forest products provided from the forests of the Taurus Mountains were floated or carried down to the river mouths, then exported to Cyprus, Beirut, Alexandria, Damietta, Syria, the Greek Islands, and Palestine via the ports of Antalya and İçil.Footnote 18 As McNeill notes, Tahtacı communities in the Taurus Mountains had never been busier than in this period.Footnote 19

In the second half of the century, the Ottoman government introduced extensive legal and institutional arrangements to maximize forest revenues and increase the central control over forests, forest populations, and forestry products. The Edict of 1853, the Forest Bill of 1861, the Forest Regulation of 1870, and the codes and instructions issued subsequentlyFootnote 20 aimed at “rational” exploitation of human and natural resources and the provision of a sustainable yield for the state treasury. Restriction of customary rights and traditional privileges – alongside the emergence of a forest bureaucracy, the enforcement of new monitoring techniques (such as tree removal procedures based on scientific principles), and the invention of new forest crimes and penalties – were designed to eliminate local elements and establish strict administrative control over forests.Footnote 21

However, the Ottoman government could neither efficiently exploit the forests itself, especially due to financial problems caused mainly by the Crimean War, nor increase tax revenues from the export of forest products due to widespread smuggling. For these reasons, granting forest concessions to private companies for the mass removal of trees became the primary way to generate state income from the forests. Even though Tahtacı families could obtain cutting licences, these were issued on a retail, not wholesale, basis. Retail licences allowed them to extract only small amounts of timber.Footnote 22 Deprived of the financial and political power to purchase trees via tender, Tahtacı families were left with little choice but to work on contract for those merchants who were able to win tenders, hire large ships, and bypass procedures such as counting, measuring, and marking trees due to their established connections with bureaucrats.Footnote 23 This practice continued until the promulgation of the 1937 Forest Law, which replaced concessions with state enterprises and established a General Directorate of Forestry as the ultimate manager of forests and the only contractor of forest labour.Footnote 24

The conditions of employment contracts imposed by the timber merchants drove many forestry labourers into a chronic debt burden. Before signing such contracts, the merchants would negotiate strict terms for the procurement and transportation of timber, which had to be delivered according to the agreed amount and by a given date. The merchants usually provided the animals used to transport the timber under a deferred payment arrangement, with the labourers required to make payment with interest for the animals once the timber was delivered. The merchants overcharged for these animals, which constituted an additional source of income for them. For their basic needs, labourers could also be paid in advance, which was a further opportunity for merchants to charge interest. After the products were transported to the ports, the cost of the animals and other provisions, advance payments, interest, and taxes were deducted from the market price of the timber. This calculation always ended with the labourer becoming indebted to the merchant.Footnote 25 In addition, some merchants intentionally manipulated the weight of the timber to their advantage.Footnote 26 Due to their debt burden, Tahtacı communities were trapped in an anticompetitive and exploitative relation with these local notables.

A decree of the Supreme Council dated 1857 demonstrates the dependency of the forestry labourers. This decree referred to contracts signed among peripatetic Tahtacı tribes and timber merchants in Menteşe. The terms of these contracts reveal the working conditions of the Tahtacı as well as their relations with the timber merchants. Each contract was signed between a group of Tahtacı consisting of fifteen to twenty people and an agha. These contracts were valid for three years. There was an exclusive relationship between the Tahtacı and the aghas, which meant that their timber could be sold to no one else except the agha for whom they were currently working. The food and animals provided by the aghas were valued at above-market prices, whereas the timber processed by the Tahtacı was valued at much lower than the going market rate. For instance, timber that would fetch four kuruş on the open market could be valued at two kuruş when delivered by Tahtacı labourers to the merchant. In this way, an agha could earn an income of 80,000–100,000 kuruş plus a twenty per cent güzeşte zammı (interest collected on debt). Since expenditures increased annually, it was impossible for Tahtacı families to repay their debts. In some cases, debt-ridden people were obliged to give away their products for free unless they could find another agha willing to pay their debts. Thus, according to the Supreme Council's decree, the Tahtacı had become “prisoners of a few people, with an increasing debt day by day”.Footnote 27 For this reason, the decree ordered that the exorbitant prices be amended and the labourer's debts repaid in reasonable instalments. Finally, so that the Tahtacı could repay these instalments, they would be allowed to sell their timber to whomever they wished.Footnote 28

A petition submitted by a group of Tahtacı some fifteen years after this case describes a comparable situation. According to the complaint, the group had migrated from Antalya to Mersin to work in timber production. The petitioners complained that the timber merchant Nikola had overcharged them for provisions he supplied during their work and bought their products for less than the market value. Nikola claimed 33,435 kuruş from the labourers, whereas they stated that he forced them to pay for timber that was lost or destroyed after they had delivered it to him. An investigation committee was established following this complaint. The committee, presided by Abdulkadir, prepared a chart of accounts including the debts between the timber merchant and the community – four households consisting of some fifty people in total. The committee decided that the merchant had to pay two thirds of the price of the damaged timber. Accordingly, the debt of the community decreased to 4,182 kuruş.Footnote 29 The 1857 decree and the 1872 petition thus indicate that at least in the early period of the commodification of forests from the beginning of the 1850s to the early 1870s, the administration was prepared – in certain circumstances – to intervene in local conflicts in favour of labourers.

Another story of the arbitrary practices of merchants towards the Tahtacı comes from Biga. According to a record dated 1865, the timber merchant Ahmed mistreated a group of Tahtacı who worked for him. This community had been living in Biga since 1845. Demanding 4,000 kuruş from the community, he not only seized the money of Kara Ali, Koca Mustafaoğlu Mahmud, Mehmed Ali, and Kadiroğlu Mustafa by force, but also turned them into his debtors by preparing a debt certificate for 26,000 kuruş. Thereafter, he brought them to Karesi in chains and sold their mules, obtaining 7,500 kuruş from the sale. Moreover, he beat one with his rifle and released them only after they accepted an additional debt certificate for another 2,000 kuruş. The man assaulted by Ahmed died three days later.Footnote 30

In this period, it was common among the Tahtacı to move to neighbouring regions to escape deepening debt and pressure from timber merchants. The migration routes Tahtacı groups followed were shaped by the accessibility of forest resources and the volume of labour demand in forestry. There are several petitions in the Ottoman Archives submitted by timber merchants during the 1850s and 1860s demanding the return of Tahtacı communities that had migrated due to their unpaid debts. These complaint petitions demonstrate the existence of two migration trends in the Teke region in this period (see Figure 1). The first was to move from the western to the eastern Taurus, mainly the Adana region, where, due to increasing demand from Egypt for Anatolian timber,Footnote 31 there was a substantial need for forest labour. The second tendency was to migrate to the northwest, basically the Menteşe sub-province, known for its rich forests and proximity to the Aegean islands and Egypt.Footnote 32

Figure 1. Major Administrative Units in Mediterranean Anatolia and the Migration Patterns of the Tahtacı.

A petition dated 1854 indicates that a group of Tahtacı in Teke had moved to İçil and Adana without paying their debts. The claimants from the Zenâiroğlu family thereupon demanded that the administration collect the debt from the community members who had stayed in Teke.Footnote 33 According to another document, dated 1858, a group of Tahtacı moved from Antalya to Adana, where demand for timber workers was greater. A group of merchants in Antalya sued them, claiming that they had left the province without paying their debts. Thereupon, the community members submitted a petition to defend themselves in which they stated that they had no occupation other than timber harvesting and had to migrate to Adana to work in the forests.Footnote 34 A similar migration from Teke was mentioned in a document issued in 1857. In the years 1854, 1855, and 1856, seventy-six Tahtacı and AbdalFootnote 35 families “slipped away” from Teke to the regions of İçil, Adana, and Konya without paying their debts to merchants or their taxes. The tax burden for 1855 alone was 28,000 kuruş. Moreover, twenty-three nomadic Tahtacı families in the Tarsus district owed debts to merchants amounting to 200,000 kuruş.Footnote 36

About a decade after these cases, it was recorded that a Tahtacı community in Teke had moved to the Menteşe sub-province without paying their taxes,Footnote 37 exemplifying the second migration route that the Tahtacı followed. Similarly, according to the petition submitted by the merchants from the Zenâiroğlu family, a group of Tahtacı, consisting of twenty-one households that had pursued a mobile way of life within the boundaries of the Teke sub-province, migrated to Menteşe without paying a debt of 90,515 kuruş. The merchants demanded their return to Teke and claimed that the new customers of the Tahtacı were not allowing their return to the Teke sub-province. They were worried that Tahtacı who had stayed in Teke would escape, too, so long as the local government refused to interfere in the matter.Footnote 38 Due to the perpetuation of community-based taxation practices, other members of the Tahtacı community in Teke began paying the share of the taxes of Tahtacı families that had moved to Menteşe, which amounted to 15,420 kuruş.Footnote 39

In 1868, contrary to the claim that it declined to intervene, the government of Teke demanded the repatriation of Tahtacı who had moved to Menteşe to escape their debts to locals. The local governor corresponded, however, that it was not possible to return the Tahtacı. It had been about twenty years since they arrived in Aydın, and they were generally pursuing a sedentary way of life.Footnote 40 Forcing these skilled workers to leave the production area and resettle in their previous abode would be contrary to the interests of the local merchants and the local government in Menteşe, as well as the central government. Notwithstanding the growing pressure from local merchants and indebtedness, such conflicting positions among officials and merchants created room for the Tahtacı to manoeuvre, allowing them to escape taxes and obligations related to their deepening debt by moving elsewhere.

Another challenge for the Tahtacı beginning in the 1870s was that they faced a more demanding administration. The government attempted to increase control over the human and natural resources in the countryside with centralist policies concerning forestry, taxation, and conscription. Hill communities, including the Tahtacı, developed new strategies to avoid the Ottoman officials’ efforts to exert administrative control. The major contested issue between the Tahtacı and the government in this period was military conscription. Losing young men to military service drained the community's labour pool, seriously undermining its subsistence livelihood.

In the 1870s, when Ottoman officials attempted to extend the requirement for compulsory military service to Tahtacı men, the latter demanded a continuation of their exemption from military duty by stating “they had been Kıbtî since time immemorial (mine'l-kadîm)”.Footnote 41 Kıbtî was a term used in the Ottoman Empire to designate peripatetic groups such as the Roma, the Poşa or the Abdal, also known as “Gypsies”.Footnote 42 These communities, Muslim or otherwise, were excluded from military service and paid the cizye, a poll tax collected from non-Muslim subjects.Footnote 43 Even though Tanzimat reformers abolished the cizye in 1856, it was replaced first with iane-i askerî (military assistance) and then with bedel-i askerî (military payment-in-lieu), taxes paid by non-Muslim subjects in place of military service.Footnote 44 In other words, the practice of cizye continued under the label bedel-i askerî for a couple more decades. In this period, both Muslim and non-Muslim Kıbtîs continued to pay this taxFootnote 45 until the government prepared a decree at the end of 1873, which was delivered to the provinces in early 1874, that extended the obligation of military service on Muslim Kıbtîs.Footnote 46 Until the obligation was extended to the Kıbtîs, the term was somewhat derogatory, and the label itself had functioned as a tool for exclusion. Now, the Tahtacı leveraged it as part of a shrewd counter-strategy to protect their autonomy and resist encroachment by the state.Footnote 47

When the Ottoman government introduced compulsory military service also for Kıbtî-registered groups, the Tahtacı communities employed another novel strategy. Through their networks, they obtained Iranian passports from the Iranian consuls in the empire and claimed exemption as foreign subjects. In 1906, a group of Tahtacı in the Burdur sub-province, for example, was found to have avoided military service because of their Iranian citizenship.Footnote 48 According to the report of the Konya Governorate, Battal Kahya, a member of a nomadic Tahtacı community in Dinar, helped thousands of Tahtacı in Isparta obtain Iranian passports from the Iranian Consulate in Konya to claim exemption from military duty and taxes.Footnote 49 In 1908, another group of Tahtacı in the Isparta sub-province, who were referred to as Kıbtî Tahtacı in official records, asserted their Iranian citizenship to demand the continuation of their exemption from military duty.Footnote 50 The 1918 report of Niyazi Bey also mentions 30 settled and 200 nomadic Tahtacı communities in Sandıklı and Eğridir as well as some families in Kaburgediği in the province of Adana who obtained Iranian citizenship to gain exemption from military duty.Footnote 51

Since male labourers of draft age were vital due to their contribution to timber production, the conscription of these labourers disrupted the industry. For this reason, timber merchants helped deserters by using their influence in local politics. For example, according to a report prepared by the Ministry of War in 1910, a group of timber merchants and their allies in the local government protected Tahtacı deserters in Anamur. The ministry's report asserted that to enlist the Tahtacı, these merchants had to be brought under control.Footnote 52 Niyazi Bey asserts a similar claim in his report on the Tahtacı. He alleges that non-Muslim timber merchants in the Mersin region helped the Tahtacı escape military service.Footnote 53

One result of deepening poverty brought about by the unequal relationship between the Tahtacı and timber merchants was the increasing trend among the community toward involvement in alternative livelihood strategies. This trend coincided with an increasing demand for agricultural labour in the Adana and Aydın regions due to the rapid expansion of export-oriented agriculture. As a result of these two overlapping tendencies, a growing number of Tahtacı engaged in agriculture, which led them to a more sedentary way of living. The next part discusses the dynamics of this process.

Expansion of Export-Oriented Agriculture: From Nomadism to Permanent Settlement

In the eighteenth century, western Anatolia was one of the most export-oriented regions in the empire. This trend became even stronger in the nineteenth century. From the 1830s on, a vast area in western Anatolia was opened up to export-oriented, commercial agriculture.Footnote 54 Increasing demand for cotton, tobacco, raisins, and figs from both the domestic market and industrialized countries like Britain and France saw these crops become the core of commercial agriculture on the Aegean coast.Footnote 55 Southern Anatolia experienced this process a few decades later. Adana-Mersin region, Çukurova in particular, shifted to export-oriented agriculture from the late 1870s on, when cotton agriculture was commercialized as an outcome of the infrastructural developments, increasing credit opportunities, and the expansion of commercial networks.Footnote 56

In response to this geographical differentiation, two forms of mobility emerged in Mediterranean Anatolia. Unlike the lowlands in the Aegean, where there was an increase in demand for agricultural labour on the plains due to large-scale cultivation, the lowlands along the southern coasts remained thinly populated. To a considerable extent, the rural population occupied the middle and high altitudes of the Taurus Mountains, and the overall mobility level of the rural population was much higher than that in western Anatolia. Until the late nineteenth century, transhumance, based on the seasonal movement of shepherd tribes between summer and winter pastures, remained the most widespread subsistence strategy in the Taurus Mountains, especially in the eastern and middle ranges.Footnote 57 According to a report prepared by the British consulate in 1881, most tribes in the Adana region were purely nomadic until the mid-1860s.Footnote 58 According to another report on the human geography of the Adana Plains, in the middle of the century, the Turkmen tribes in this region lived a nomadic way of life “without recognizing the government”. Wandering with their flocks and herds, they spent five to six months in the plain and the remainder of the year in the mountains.Footnote 59

In line with this general pattern, Tahtacı communities along the western coasts of Anatolia experienced the sedentarization process differently than those along the southern coasts. As export-oriented agriculture emerged earlier in western Anatolia, the Tahtacı groups in this region became more readily involved in agriculture, while the subsistence of almost all Tahtacı households along the southern coasts of Anatolia was based on peripatetic strategies. The Ottoman temettuat (income) registers indicate that the subsistence strategies of the Tahtacı along the Aegean coasts were more heterogeneous, and Tahtacı settlements established before the middle of the nineteenth century were all located in Aydın and Hüdâvendigâr provinces, where the mobility level of the community was relatively low. Even though nomadic forest work continued at high altitudes in western Anatolia up until the 1950s, some Tahtacı groups had already abandoned forest work in the first half of the nineteenth century. This process constituted the first wave of the sedentarization of Tahtacı communities.

According to the temettuat registers, a Tahtacı village located in the Simav district of Kütahya in the sub-province of Hüdâvendigâr province, accommodated eighteen households. None was occupied with lumbering. Most were engaged in agriculture and cultivated wheat, barley, and chickpeas. The villagers earned an average of 500–600 kuruş annually. Each household had some twenty to thirty goats and ten sheep.Footnote 60 In Yarangüme, located in Menteşe, in the Aydın province, there were six settled Tahtacı households that had lived and paid taxes in Manisa the year before moving to this region. They earned their living by stockbreeding and lumbering. The average income was about 1,000 kuruş.Footnote 61 There were fifty-five households in another Tahtacı village in Sobuca, Aydın. None of them was lumberers, cultivators, or stockbreeders. Most men in the village were weavers. Almost all households had one or two dönüm of vineyards and kept bees. The income of each household varied from 500 to 2,590 kuruş.Footnote 62 Another village named Tahtacı, located in the Köyceğiz district in Menteşe in the Aydın province, consisted of fifty-six households. All were peasants who cultivated wheat, barley, and millet on between ten and fifty dönüm of land. They were also engaged in subsistence husbandry. The income of the villagers varied from 125 to 1,500 kuruş. The richest household, which earned 3,525 kuruş per annum, was engaged in trade and possessed sixty goats, five mares, five cows, a mill, and seventy-five dönüm of land that they rented out to others.Footnote 63

There was a clear differentiation and social stratification in these two villages that distinguished them from traditional Tahtacı communities that could only survive by adopting certain communal practices. Another remarkable difference was that lumbering was no longer an occupation in which all members of a specific community or village were engaged, beyond the fact that none were left mass-producing timber to meet the demands of distant populations via timber merchants involved in cross-continental trade. Instead, timber was produced mainly for the local population and used as a construction material.

Türkali, Narlıdere, Göğdelen (also known as Alurca or Doğançay), Tolaz (also known as Uladı or Yakapınar), Karakuyu, Bademler, and Uzundere were further Tahtacı villages established before the middle of the nineteenth century.Footnote 64 These villages were all located in the west of the Antalya Plain.

From the 1870s onwards, owing to the escalation of demand for cotton and wheat under the Pax Britannica, the plains in the eastern Mediterranean were also opened for cultivation, and pastures, forests, and wastelands began to be converted into cropland.Footnote 65 Since this region re-emerged as a prominent commercial centre and croplands in the plains gained importance, the rural population tended to leave the highlands and pursue a less mobile life at lower altitudes.Footnote 66 The efforts of the Ottoman government to sedentarize nomadic groups showed results only when the forced attempts of the government were combined with the commercialization of agriculture, the rise of landowners, and the reclamation of land.Footnote 67 In this period, with the help of the high land-to-labour ratio and the availability of forests for clearing, many nomadic groups obtained land by sharecropping, outright purchase, and intermarriage with sedentary families.Footnote 68

Another factor that contributed to the sedentarization process was the retreat of the Little Ice Age (1300/1650–1850), a period of declining temperatures marked by extreme weather conditions, including increased glaciation, intense drought, and erratic precipitation. This climate change brought freezing cold and dry winters, crop failures, and famine to Ottoman Anatolia.Footnote 69 The overall warming trend following the end of the Little Ice Age had a distinct effect on regional economies and livelihood strategies. Duffy contends that changing climate patterns in the nineteenth century contributed to the decline of pastoral nomadism and the rise of commercial agriculture in the Mediterranean.Footnote 70 This was a period when warmer climate conditions coincided with technical advancements, including drainage of lowlands through reclamation projects,Footnote 71 which resulted in higher agricultural productivity in the coastal plains of southern Anatolia.

Notwithstanding the relatively mild weather conditions, the inhabitants of Anatolia continued in the nineteenth century to face periodic extreme weather patterns, especially severe droughts, caused by either regional or global climate trends.Footnote 72 Moreover, due to the greater vulnerability of animals to extreme weather events, it was more challenging for nomadic populations than agriculturalists to recover from these environmental crises.Footnote 73 In short, both the increased agricultural productivity and the vulnerability of nomadic populations triggered the tendency toward sedentarization.

This transformation heavily influenced the migration patterns of the Tahtacı communities. As an outcome of increasing productivity and the reopening of the plains for cultivation, the Tahtacı gradually descended to lower altitudes of the Taurus Mountains,Footnote 74 and some became involved in agriculture. In this period, Tahtacı communities developed more complex subsistence practices – a mix of peripatetic and pastoral strategies. From the 1870s onwards, the degree of mobility among the Tahtacı lessened and new villages were established, signifying a second wave of sedentarization. This trend became more evident in the early Republican period and continued over the entire twentieth century. Eventually, some Tahtacı families moved to the suburbs, where they transformed into wage-labourers.Footnote 75 Crafts related to their traditional occupation, such as carpentry and burning lime, became prominent among these groups.Footnote 76

The results of the fieldwork conducted by Niyazi Bey, whom the Ministry of Internal Affairs charged with investigating the Tahtacı living in the Adana province in 1918, affirm the tendency toward sedentarization. He witnessed these communities following a semi-nomadic lifestyle, moving to the high plateaus and forests from spring to winter. In recent years, he noted, the Tahtacı groups had been living a less mobile way of life based on nomadism between fixed winter quarters at lower altitudes and changeable forested lands close to their winter quarters.Footnote 77 Roux states that at the beginning of the twentieth century, ten to thirty related Tahtacı families constituted an oba, the most important unit of social organization among the Tahtacı. Several obas shared a summer territory and a winter territory.Footnote 78 In winter, they lived in their villages down in the valleys. Shortly before spring, they left their villages to inhabit the forests in the highlands until the following winter.Footnote 79 They built temporary sheds over several days from materials they collected from the forests. Almost all Tahtacı houses were made of wood. At the beginning of winter, these houses were dismantled, and the materials were sold on the market. The winter villages of the Tahtacı functioned as storage for the timber they had cut and processed during spring and summer.

Niyazi Bey underlines that the Tahtacı villages at the highest altitude in the province of Adana were at 800–900 metres. Families spent their summers in forests that were located much closer to their winter quarters compared to the forests they had inhabited in previous decades. For instance, the Tahtacı communities in Dalakderesi began to spend summers in Ayvagediği, four hours from their village. As of 1908, the Tahtacı in Kaburgediği were climbing to Kalecik, which was three hours from their village. Before that, they used to spend their summers at higher elevations in the Tanzıt region. Just like the Tahtacı of Belenkişlek, except for five to ten families, they engaged in agriculture and lived at lower altitudes.Footnote 80

Even though most Tahtacı families were piece-rate wage earners employed by timber merchants, there were still a few self-employed kin producers among them in this period.Footnote 81 In his report on the Tahtacı in the Adana region, for example, Niyazi Bey mentions Tahtacı families wandering on the streets of the Tarsus district every Monday and Thursday, their mules loaded with timber and firewood to be sold in the local market in exchange for grain, sugar, coffee, and fabric.Footnote 82

The establishment of most Tahtacı villages in the last decades of the nineteenth century resulted from the availability of empty land and forests to clear. The inhabitants of Çamalan and Kaburgediği, two current-day Tahtacı settlements in Mersin province, say that their villages were established in the 1860s on empty fields at altitudes above 700 metres in Tarsus.Footnote 83 Some Tahtacı groups of Tarsus migrated west in the 1870s and established the village of Dalakderesi by clearing a forest. A further factor contributing to this area's settlement process was sharecropping. The pioneers of Dalakderesi continued lumbering but also worked for landowners.Footnote 84 Some three decades later, a group of Tahtacı in Mut descended to lower elevations where large landowners were increasingly searching for labourers to work in their fields. They began to work for the Kravgas, a notable, influential family, as sharecroppers, thus adopting a mixed subsistence strategy based on forest work and cultivation. In this process, their mobility gradually decreased. The forests they worked in spring and summer grew closer to their winter quarters, which then became their permanent settlements. Köprübaşı village, located in the current province of Mersin, was formed as a result of this process.Footnote 85

Living at lower altitudes and logging in forests that were closer to towns and villages brought not only new opportunities but also new challenges. Tahtacı communities were considered both by nomadic herding communities and sedentary agriculturalist villagers as distinct and therefore unmarriageable.Footnote 86 Unlike the nomadic pastoral groups known as Yörük, who used the opportunity to obtain land by intermarriage with sedentary agricultural groups in the late Ottoman and early Republican periods, the peripatetic Tahtacı had no such opportunity.Footnote 87 Furthermore, the presence of the Tahtacı groups in the valleys produced social tensions. The locals of Ortakçı village of Aydın, for example, sued the Tahtacı communities that the government settled on their plateau.Footnote 88 Another example is the complaint of several villagers from Antalya dated 1909. Their petition indicates that a timber merchant named Lülüzade Ömer Efendi hired a group of Tahtacı to harvest timber. The villagers asserted that, by allowing the animals of the Tahtacı onto their land, Ömer Efendi and the Tahtacı prevented them from cultivating it and caused the destruction of olive groves.Footnote 89 It was evidently not exceptional that closer interaction of the Tahtacı with sedentary communities caused disputes at the local level.Footnote 90

Conclusion

Regarding Simmel, Berland emphasizes that, like the “inner enemies of Sirius”, peripatetics are not seen as organically connected members of communities, even though they are constitutive elements of every society.Footnote 91 From this starting point, this article has tried to see the peripatetic Tahtacı communities from a perspective that considers them connected components of the Ottoman countryside. Exploring the intersection of nomadism, forestry, and labour relations, the article has problematized the conventional wisdom on lowland–upland relations and offered a historical representation of the Tahtacı in dialogue with their social, economic, and political environment.

The main question addressed in this article is what sort of strategies the Tahtacı developed in order to cope with commercialization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One of the main differences from previous centuries in terms of the working environment of the Tahtacı was that they rarely confronted their clients. The most common way Tahtacı communities earned a living in the late Ottoman era, especially given the increasing commercialization of forestry in the middle of the century, was to provide forest products to timber merchants embedded in regional trade networks and – owing to their relations with officials – could lease state forests for long-term use. This transformation marked a significant shift in labour relations in Ottoman forestry. Even though self-employment did not completely disappear, there was a significant shift to wage labour. The central tendency among the Tahtacı households involved in forest work was piece-rate wage labour.

Moreover, it was not an exception that wage labour evolved into debt bondage, indicating “the grey area between the poles of chattel slavery and ‘free’ wage labour”.Footnote 92 In the mid-nineteenth century, many Tahtacı households were contracted by timber merchants to work as bonded labourers to repay their debts. As a result of their peonage, Tahtacı communities became more impoverished and dependent on these merchants. As forest work was a challenging, labour-intensive occupation, which required geographically localized knowledge that could not be replaced by any contemporaneous technology or expertise of scientific foresters, timber merchants and officials were also dependent on the Tahtacı. With their cheap, valuable labour and knowledge of mountains, forests, and trees – based on their sustained experience in timber harvesting – Tahtacı communities were indispensable for the continued provision and transportation of substantial amounts of forest products. The bonded labour and specialized expertise of the Tahtacı made the Taurus region a prominent centre for timber production.

This was also a period when the Ottoman Empire was incorporated into the global economy through export-oriented agriculture. The level and form of involvement in agricultural production among the Tahtacı in this process varied depending on economic, climatic, and geographical conditions. Some depended on crops produced by villagers, some practised subsistence farming, others worked as sharecroppers or wage-labourers, and a minority of self-employed producers cultivated for commercial purposes. The varying levels of integration into the world system created a differentiation among the Tahtacı. Along the Aegean coasts, where commercial agriculture emerged earlier, increasing export-oriented agriculture created an opportunity for some Tahtacı families to obtain land from the beginning of the nineteenth century onwards, while others worked as agricultural wage-labourers or sharecroppers, signalling an important shift in labour relations. The subsistence strategies of the Tahtacı on the southern coasts, on the other hand, substantially changed in the 1870s, once the Little Ice Age had ended and commercial agriculture began expanding. For many Tahtacı groups, spatial mobility remained the main component of their survival strategies, but in a narrower area and at lower altitudes and occasionally based on both peripatetic lumbering and sharecropping.

Acknowledgements

I thank Ali Sipahi, Egemen Yılgür, Özkan Akpınar, the Editorial Committee, and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier versions of this article. I also thank the Suna and İnan Kıraç Research Center for Mediterranean Civilizations (AKMED) for their generous support for my project (KU AKMED 2021/P.1057).