Five years after the Umbrella Movement, the anti-extradition bill protests in 2019 have once again highlighted the deep political fault lines in Hong Kong. While these large-scale social movements have clear political objectives, conservative elites and officials are always eager to direct the blame to the socioeconomic grievances held by the protesters. To what extent this is true? Answering this question is no easy task, given the intertwined nature of political and economic issues (e.g., Wong Reference Wong2020). The same goes for party competition in Hong Kong, which has often been regarded as non-ideological and defined by the cleavage between the pro-democracy and pro-Beijing camps. With politics and elections usually centering on competition at the level of these two camps, socioeconomic (left–right) ideology has largely been overlooked or assumed to be negligible. This article provides evidence that there is a socioeconomic ideological dimension in party competition in Hong Kong, albeit one that is subordinate to the primary cleavage.

Using a new dataset capturing parties’ ideological positions based on election manifestos, it is found that parties take up positions along a left–right spectrum corresponding to our general understanding of what a position on that spectrum entails. In combination with existing data on the parties’ levels of political support, this study finds that a left-wing position is significantly associated with stronger popular support, providing evidence that the electorate in Hong Kong is generally left-leaning. It is also demonstrated that movements in aggregate voter ideological preferences are correlated with economic growth rates. In addition, ideology is found to be increasingly prominent in local politics at the expense of a narrow focus on welfare, which may be indicative of a more sophisticated voter base. Further, the coding provides empirical evidence that the traditional focus on democracy and freedom underlying the primary competition between the pro-democracy and pro-Beijing camps is gradually being replaced by the emerging concern of integration with mainland China. While such a development has its roots in the Umbrella Movement of 2014 and the emergence of a localist discourse, with the conflict surrounding Hong Kong's autonomous status intensifying, it remains to be seen whether this represents a long-term shift or a temporary phenomenon amidst the recent large-scale protests.

This article makes two main contributions. First, it provides manifesto coding data for Hong Kong following the framework established by the Manifesto Research on Political Representation (MARPOR) group (formerly the Manifesto Research Group and Comparative Manifesto Project). These data will facilitate the study of party ideologies in Hong Kong, which have until now been severely overlooked. In contributing to MARPOR, the Hong Kong data also broadens the scope of the larger project, which has overwhelmingly focused on (particularly Western) democracies. By applying the framework to Hong Kong, which is a sub-national hybrid regime with largely competitive elections, this article demonstrates the feasibility of its application to a more diverse set of regimes (this question of applicability is further discussed below). Overall, the study bridges different branches of literature by introducing Hong Kong to a robust comparative framework and providing international scholars with an additional perspective from which to understand Hong Kong, which is sometimes regarded as a unique case.

Second, this study fills a gap in the literature by investigating the dynamics of party competition in Hong Kong—an important topic that has seldom been systematically studied due to a lack of relevant data. The study particularly enriches the literature on electoral politics in Hong Kong in relation to the dynamics of party positioning, intra- and inter-camp competition, and voter preferences. It must be noted that this article does not discount the importance of the primary political divide in Hong Kong politics. One explanatory factor used in the analytical section is the major political cleavage between the pro-Beijing and pro-democracy parties; the study also provides data describing the changes in this cleavage over time. The article has three main objectives: to establish the manifesto coding framework as a viable tool for political analysis in Hong Kong; to consider how the pro-democracy versus pro-Beijing dimension has evolved; and to challenge the assumption that political parties in Hong Kong are non-ideological.

LITERATURE REVIEW

POLITICAL PARTIES AND SOCIAL CLEAVAGES

Political parties are often regarded as indispensable to a well-functioning democracy (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1942). In the process of preference formulation, individuals often rely on partisanship as a heuristic to bypass the complexities of politics. Party labels also provide an information shortcut for voters when they formulate their voting decisions. Given the centrality of political parties in democracies, party identification is still held to be a central element of democratic politics in spite of the gradual decline in partisanship around the world (e.g., Dalton and Weldon Reference Dalton Russell and Weldon2007).

The arrangement of political parties in a system depends on the underlying social cleavages (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). Parties originate from and compete along the politically relevant cleavages. While individual countries have their own combinations of social cleavages, the socioeconomic cleavage along class lines should be considered as the most prominent division in politics, at least in advanced industrial democracies (e.g., Caramani Reference Caramani2004; Stoll Reference Stoll2008). For example, Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1999) finds the socioeconomic cleavage to be salient in all of the thirty-six democracies he studies. Research repeatedly demonstrates that the majority of voters in most Western democracies conceive of politics in terms of the left–right ideological dimension and can place themselves properly on the scale (Castles and Mair Reference Castles and Mair1984; Inglehart and Klingemann Reference Inglehart, Klingemann, Budge, Crewe and Farlie1976). Parties are also found to rely on this scale as the principal dimension of voter communication across democracies (Gabel and Huber Reference Gabel and Huber2000). Building on the seminal contribution by Downs (Reference Downs1957), spatial models of voting emphasize how voters decide based on parties’ ideological positions. In its simplest form, the idea is that parties occupy different positions along an ideological spectrum, and voters support parties that approximate their own position. Therefore, there are good reasons to suspect that a left–right socioeconomic dimension will emerge in an electoral setting.

While a one-dimensional spatial model seems overly simplistic, subsequent studies incorporate more realistic assumptions, such as competition across more than one policy space (e.g., Adams, Merrill, and Grofman Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005). However, Stoll (Reference Stoll2008) argues that multiple cleavages are often simultaneously salient, and that different cleavages are politicized in different cases/periods. The practical significance of the identification of cleavages lies not only in the way people are politicized but also in the number of political parties in the system and in the formation of partisanship. This article examines whether a secondary socioeconomic cleavage exists alongside the primary pro-democracy/pro-Beijing cleavage in Hong Kong.

AUTOCRATIC ELECTIONS AND HYBRID REGIMES

Elections are not exclusive to democratic regimes. Hybrid regimes are systems that are undemocratic but nonetheless adopt formal democratic institutions. Electoral authoritarian regimes hold regular elections, but the playing field between the incumbent elites and opposition groups is manipulated in favor of the former (e.g., Geddes Reference Geddes2006; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010). Far from being free and fair, as in a democracy, elections in authoritarian regimes play a different political role. Studies of authoritarian elections often focus on the rationale behind the existence of such institutions, such as to demonstrate strength and deter potential challenges (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011; Geddes Reference Geddes2006; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006), resolve conflicts between ruling elites (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011), co-opt opposition elites (Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2006), or gain international legitimacy (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Schedler Reference Schedler2002).

In this context, studies of non-democratic elections often focus on the balance between the incumbents and opposition groups. Brownlee (Reference Brownlee2007) suggests that autocratic elections inform the rulers about the strength of political opposition and of critics among the general population. Electoral shocks to the ruling party signal citizen dissatisfaction, thereby prompting the ruling party to grant policy concessions (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Miller Reference Miller2015). Furthermore, voters strategically express their dissatisfaction (instead of maximizing it every time) to balance policy concessions with targeted rewards (or punishments) (Miller Reference Miller2015). Given that the key political divide is often democratization, support for different opposition parties is not often distinguished. Exceptions can be found when there are theoretical reasons for making such a distinction. For example, Mexico's Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) adjusted its policy positions based on the support enjoyed by populist and conservative opposition parties (Greene Reference Greene2007). According to Kosterina (Reference Kosterina2017), much of the literature assumes that the interests of the opposition parties are synonymous with those of their constituents. This assumption may work to the detriment of understanding political dynamics in hybrid regimes, as people may even become dissatisfied with opposition groups in response to behavior such as collaboration with the regime (e.g., Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2010).

POLITICAL PARTIES IN HONG KONG: A NON-IDEOLOGICAL COMPETITION?

Since its retrocession in 1997, Hong Kong has been on a very uncertain course of democratization as a special administrative region under Chinese sovereignty. Currently, it is generally regarded as a hybrid regime with regular elections (e.g., S. Wong Reference Wong2014; M. Wong Reference Wong2017), albeit with a growing tendency for more authoritarian-style manipulations (Fong Reference Fong2017). Political parties have a rather short history in Hong Kong, as they only appeared following the partial opening-up of the system in the 1990s. Despite their regular participation both inside and outside of formal institutions, the development of parties has been heavily constrained in the post-handover system due to Beijing's reluctance to permit strong parties in Hong Kong, even those that are pro-Beijing (Lau and Kuan Reference Lau and Kuan2002). The electoral system was switched from first-past-the-post to proportional representation in 1997, which served to weaken the established parties (Ma Reference Ma2007). Almost half of the seats in the legislature are not popularly elected, being returned from a narrow franchise, which renders parties less relevant in (although not absent from) those races. The Chief Executive, which is the highest political office, is legally required to be non-partisan, thus ruling out the possibility of a governing party. Parties can only compete in legislative and district elections but not directly for executive power. Up to the end of this study in 2016, parties could for the most part compete freely in the electoral races opened to them without the concern of being subjected to the repression often found in hybrid regimes.

Political parties in Hong Kong are traditionally characterized by their position on the divide between pro-democracy and pro-Beijing groups (Ma Reference Ma2007). The former group advocates more rapid democratization and the protection of civil liberties, whereas the latter is supported by Beijing and often aligns itself with the Chinese government's position. Despite many intra-group changes, such as the formation of new parties, the pattern of inter-group competition has been remarkably stable. Most voters and the media pay much more attention to the performance of each of the two camps as a whole than to that of individual parties. This is perhaps natural because pro-democracy legislators vote similarly on most political issues, as does the pro-Beijing camp, which usually adopts the opposite stance. The recent rise of localism (e.g., Kaeding Reference Kaeding2017) has challenged the status quo through the introduction of a group of new opposition parties advocating self-determination or even independence. This has realigned the competition to one between pro-establishment (Beijing) and “non-establishment” (made up of the original pro-democracy parties plus the new localist factions) groups. However, in response, Beijing is taking a different approach towards these localist forces, disqualifying their candidacies or even prosecuting them after they are elected. Traditional democrats are not subjected to this approach, as they ultimately recognize China's sovereignty (e.g., Kwong Reference Kwong2018). This strategy could undermine Beijing's claim of sovereignty in Hong Kong. Regardless of the arrangement of the opposition camp in the coming years, it is clear that questions about Hong Kong's political future and the level of autonomy it enjoys will dictate its political agenda for some time.

Due to the dominance of the pro-democracy/pro-Beijing divide, it is almost conventional wisdom that ideology on the left–right spectrum is of little importance in Hong Kong. There is no lack of anecdotal examples to illustrate this. The Democratic Party (DP) and its allies attained a majority in the last colonial legislature in 1995. After pondering what to do with this new-found influence, its leaders eventually agreed to reduce the profits tax precisely because “everyone expected them to increase [it]” (so as to appear reasonable and appeal to more people).Footnote 1 The primary cleavage has often taken precedence over socioeconomic considerations when the two have been in conflict. The Federation of Trade Unions (FTU), a pro-Beijing union-cum-party with an emphasis on worker welfare, abstained from voting on a seven-day paternity leave proposal in 2014, backing the government but directly contradicting its earlier platform.Footnote 2 This shows that parties in Hong Kong still prioritize politics over socioeconomic considerations. Under the proportional representation system used in legislative elections since 1997, voters usually have no problem voting strategically for another party to maximize the seats gained by their preferred camp. It is commonly believed that the pro-democracy camp used to enjoy a 60:40 edge (the so-called “golden ratio”) in popular support in elections regardless of the intra-camp split (e.g., Ma Reference Ma2007; Wong Reference Wong2015). Although the recent rise of localists might be eroding the support enjoyed by traditional pro-democracy parties, this development seems to reinforce the non-ideological nature of politics instead of challenging it.

However, it can also be argued that the non-ideological nature of party competition may be gradually changing, especially after the emergence of new parties representing a wider range of positions within both political camps. Since the switch to proportional representation in 1997, the number of parties has gradually increased. The effective number of political parties directly elected to the legislature in 1998 was 3.4; this figure rose to 7.7 in 2012 (Wong Reference Wong2017). Among the new parties formed in the pro-democracy camp within the last two decades, the League of Social Democrats (LSD) and the Labour Party have strong leftist leanings, whereas the Civic Party (CP) appeals to the middle class and professionals. In the pro-Beijing camp, the FTU has participated much more actively in recent elections to capture working class votes, while the New People's Party (NPP) and the Business and Professionals Alliance (BPA) were formed to capture middle class and business support. While Dalton and Weldon (Reference Dalton Russell and Weldon2007) report, based on data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, that there are hardly any partisans in Hong Kong, the share almost quadrupled in the period 2000–2005 (albeit from 7.9 percent to 28.1 percent, which still left it ranked among the lowest cases). Given these developments, therefore, it is worth revisiting if (and to what extent) party ideology matters. In fact, as I will show below, ideology has always played an implicit role in elections in Hong Kong despite the generally non-ideological impression held by observers of Hong Kong politics.

CAPTURING POLICY POSITIONS

The MARPOR provides data on political parties’ left–right policy positions based on content analysis of their election manifestos (e.g., Klingemann et al. Reference Klingemann, Volkens, Bara, Budge and McDonald2006; Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013). Its main measure captures the frequency of statements about right-wing issues versus left-wing ones, placing parties on a left–right scale for each election (with a set of new manifestos). The MARPOR incorporates a wide range of social and economic issues (for details, see Budge and Meyer Reference Budge, Meyer, Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013, 87–88), enabling scholars to trace parties’ ideological movements over time (Barth, Finseraas, and Moene Reference Barth, Finseraas and Moene2015; Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013; Williams and Whitten Reference Williams and Whitten2015) and examine puzzles that are otherwise difficult to tackle. For example, Tavits and Letki (Reference Tavits and Letki2009) find that in post-Communist Europe, where there was a dual transition to democracy and a market economy, the usual ideological expectations no longer hold, as leftist parties tighten budgets and rightist ones actually spend more.

However, the MARPOR is limited by the fact that parties do not always follow their manifestos once they are elected (Netjes and Binnema Reference Netjes and Binnema2007); nonsystematic errors might also arise from the text generation and text coding process (Klingemann et al. Reference Klingemann, Volkens, Bara, Budge and McDonald2006; Lacewell and Werner Reference Lacewell, Werner, Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013). Benoit and Laver (Reference Benoit and Laver2007) further argue that the MARPOR data are plagued by moving benchmarks, measurement uncertainty, and a lack of reliability between coders. Expert surveys are another popular tool, allowing academic experts to evaluate party positions subjectively (e.g., Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2007; Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015). By combining various sources of information, including manifestos and political behavior, an expert survey can better capture what parties say and what they do (Netjes and Binnema Reference Netjes and Binnema2007; Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015). Nonetheless, the coding of positions by experts is highly subjective and often less transparent than the process of manifesto coding (Busch Reference Busch2016). While a more detailed discussion of the strengths and weakness of the MARPOR is out of the scope of this work (see e.g., Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2007; Volkens Reference Volkens2007; Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013), manifesto coding will be the primary methodology used in this article, supplemented by expert judgments. The MARPOR has been found to have high levels of data reliability (Klingemann et al. Reference Klingemann, Volkens, Bara, Budge and McDonald2006; Budge and Pennings Reference Budge and Pennings2007) and is the only dataset providing longitudinal data on party positions (Barth, Finseraas, and Moene Reference Barth, Finseraas and Moene2015). Research has found that the scores correspond very well to observers’ judgments over time and to other measurements of ideological position (Budge and Meyer Reference Budge, Meyer, Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013; Volkens Reference Volkens2007).

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

As discussed above, political competition in Hong Kong has traditionally been centered on the pro-Beijing/pro-democracy divide. This study is guided by two research questions. First, have the areas of contention in the primary cleavage remained unchanged over time? Second, the predominance of the primary divide has created the impression that political competition is non-ideological, but how accurate is this impression? In other words, are there ideological differences between the political parties beyond the primary political cleavage?

With the exception of Ma (Reference Ma2007), who classifies parties along their political and socioeconomic positions, there has been little scholarship on the ideological properties of parties in Hong Kong, let alone assessment of whether there is a secondary ideological dimension to party competition. One reason for this is the lack of objective indicators of party positions. For example, the Liberal Party (LP) has often been described as a pro-business party based on its source of power, leadership characteristics, and pro-market and anti-welfare policy positions. But is it more or less pro-business than the BPA, another pro-business party, and has its position changed over the past decade? Ideological positions inferred from election results, for instance, are unreliable, as they are endogenous to the preferences of the overall electorate (parties might move strategically in response to changing popular preferences to maximize electoral gain, and voters might also switch their support in response to party platforms). To overcome this problem, this article uses the MARPOR methodology to create a dataset of party positions in Hong Kong over time. The introduction of such data opens up the potential to systematically examine the research questions posed and allows for an investigation of the dynamics underlying the ideological dimension over time.

CAN THE MARPOR BE APPLIED TO HONG KONG?

Although the MARPOR is widely used in the literature for analyzing party ideology across parties and countries and over time (Barth, Finseraas, and Moene Reference Barth, Finseraas and Moene2015; Williams and Whitten Reference Williams and Whitten2015; Busch Reference Busch2016), the question of its applicability to Hong Kong needs to be addressed (e.g., Molder Reference Molder2016). As MARPOR is derived primarily from the European context, and it might not be applicable to non-Western political systems (although Japan and South Korea are notable exceptions; see Proksch, Slapin, and Thies Reference Proksch, Slapin and Thies2011), let alone non-democratic systems. Two additional characteristics of Hong Kong might render it unsuitable for a direct application of MARPOR: its status as a hybrid regime and its lack of full sovereignty. Despite the existence of elections, the political system of Hong Kong does not allow for the popular suffrage of the Chief Executive or for half of the legislature. This shortfall in political competition makes it a hybrid (competitive authoritarian) regime, which sets it apart from typical MARPOR cases. Furthermore, Hong Kong is not a sovereign state, but a special administrative region of China. This raises the question of whether the framework is at all compatible with sub-state systems.

While the differences might seem unbridgeable, I have argued elsewhere that the very combination of these two characteristics makes Hong Kong a suitable case for inclusion into the MARPOR framework (Wong Reference Wong2015). Under the “one country two systems” arrangement, Hong Kong is promised a high degree of autonomy and its own government formed by the local people. While there are increasing concerns about political interventions from Beijing undermining this promise (e.g., Fong Reference Fong2017), for the most part, Beijing does not directly involve itself in Hong Kong politics except through its local agents (pro-Beijing forces). Furthermore, in other hybrid regimes (and in non-democratic systems such as single-party dictatorships), the ruling party combines sovereign power with the power to govern. Even if somewhat competitive elections are offered, the ruling party always enjoys an advantage over opposition parties in terms of resources, media control, or the use of outright suppression (typical of competitive authoritarian regimes) (e.g., Schedler Reference Schedler2002). This is why Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2010) regard “an uneven playing field between government and opposition” as a key characteristic of hybrid regimes. As discussed, no political party in Hong Kong has direct access to executive power; on the flip side, this precludes the existence of a dominant incumbent party in the electoral system. The unique combination of a non-partisan Chief Executive who has not been popularly elected and the sub-sovereignty of Hong Kong (separating sovereignty from the local polity) has the unintended side-effect of making the party system more competitive. It follows that the dynamics of party competition commonly found in democracies might also be observed in Hong Kong (Wong Reference Wong2015).

A further question is whether the left–right socioeconomic conception of ideological competition (and the RILE scale discussed below) is meaningful in Hong Kong. Based on the classic definition of politics as “who gets what, when, and how,” socioeconomic issues should be a central concern for all kinds of political systems everywhere. Given the longstanding domestic debates about welfare, housing, and redistribution, there is little reason to assume that socioeconomic concerns would be any less relevant in Hong Kong. Granted, the idea of left–right (i.e., the framework and design of the instrument) might differ from case to case, but the value of frameworks like the MARPOR lies in having a standard benchmark for comparative analysis. In any event, if ideology is not a real factor in Hong Kong politics, this exercise (the attempt to identify a non-existent ideological dimension) would simply generate random data (noise) rather than any significant or notable results. In the analysis below, the coding framework of the MARPOR is directly adopted, with the only adjustment being to change those categories that reference “Europe/European Union” to instead refer to “mainland China.”Footnote 3

METHODOLOGY

DATA

Few political parties in Hong Kong publish formal manifestos before an election, and such manifestos receive little attention even when they are released. To maintain consistency and maximize data coverage, election platforms provided by candidates to the official election agency are used as manifestos in this study. These platforms appear on official election materials sent to voters (reminding them when/where to vote, who the candidates are, etc.), and the space allowed for each ticket is standardized (although candidates can decide how much text/graphics to fit into the space). An example of a platform is shown in the Appendix. Given that party-election is our unit of analysis, parties running in multiple districts are considered as a unit, and their materials are aggregated to form a full manifesto.Footnote 4 The same procedure is followed for parties fielding more than one list in the same constituency.Footnote 5

The purpose of this exercise is to arrive at an ideological position for individual political parties. Following MARPOR, we focus only on the written information provided by breaking manifestos down into “quasi-sentences.”Footnote 6 Each quasi-sentence is then coded using 57 issue categories. For example, a sentence might be coded as a positive reference to welfare state expansion or a negative statement toward immigrants. All of the documents were coded twice by different coders based on the MARPOR codebook,Footnote 7 and the author provided an independent assessment in cases of discrepancies.Footnote 8

The primary variable, representing positioning on the MARPOR Left–Right Scale (RILE), is constructed as the difference between the percentage of quasi-sentences emphasizing right-wing ideology (e.g., freedom, law and order, economic incentives) and the percentage emphasizing left-wing ideology (e.g., social service expansion, labor rights). The theoretical range of the scale is from −1.0 (most left-wing) to + 1.0 (most right-wing). A concise summary and validation of the RILE can be found in Budge and Meyer (Reference Budge, Meyer, Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013), among others (but see, e.g., Molder Reference Molder2016 for a critique). Instead of the general left–right spectrum, some studies have focused on the narrower concept of welfare using sub-measures of the MARPOR. Following Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) and Barth, Finseraas, and Moene (Reference Barth, Finseraas and Moene2015), the Welfare measure is constructed by subtracting statements on limiting welfare programs from favorable mentions of their expansion divided by the total number of quasi-sentences. As opposed to RILE, a more positive score indicates a more pro-welfare election platform (ranging from 0 to 1). The scores for both RILE and Welfare for all parties in Hong Kong over time are available in the Appendix. While the dataset reports data for all political groups that have ever participated in a legislative election, not all of them are included in the regression analysis due to the use of party fixed-effects (dropping all one-time groups) and missing data for other variables.

ANALYTICAL STRATEGY

The unit of analysis in this research is party-election (a single political party at a single legislative election). It includes a total of 39 parties in Hong Kong from 1998 to 2016 (six legislative elections).Footnote 9 The analysis section is divided into three parts to answer each of the research questions. First, the dataset is used to examine the differences between the pro-democracy and pro-Beijing camps, which is regarded as a simple approach to assessing whether the dataset returns logical and understandable results, and to answering the first research question on the stability of the primary divide. The validity of the data is further examined by comparing the measurements to expert assessments of party positions, which are used to complement the manifesto measure, as discussed above. For this purpose, expert scores are taken from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES 2015) (by the local investigator), which is a popular source for benchmarking manifesto scores (e.g., Best Reference Best, Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013). Expert assessments of the left–right socioeconomic positions of major parties in Hong Kong are available on a scale of 0 (most left-wing) to 10 (most right-wing) up to 2008 (which was the end of CSES coverage).

Second, an analysis focusing on two elections (2012 and 2016) explores the dynamics between political camps, party positions, and electoral performance. The purpose of this exercise is to highlight the strategic interactions of parties in terms of their positions and support, as well as whether they correspond to some of the actual party dynamics during that period. This is followed by an assessment over time of the overall ideological position of the general electorate in Hong Kong, which is traced by aggregating the positions of all parties weighted by their share of votes across all elections. The changes can be interpreted as the movement of the preference of the general electorate, the shifting position adopted by the parties, or, more realistically, a combination of both. In line with theoretical expectations, a tentative explanation of the overall ideological movement is also provided based on the electorate shifting to more pro-welfare positions during times of economic downturn and uncertainty, and the opposite shift occurring during periods of strong growth. Regardless, it is argued that both sets of results, though ultimately descriptive, help to demonstrate the existence of an ideological dimension in party politics.

Finally, a regression analysis is conducted to uncover the correlation between the ideological characteristics of party competition and political support, while controlling for potential covariates. Political support is measured as the vote shares obtained by parties in legislative elections and the level of popular support.Footnote 10 As there are five constituencies, the vote shares of parties running in multiple districts will be averaged (while being summed for parties fielding multiple lists in the same district). For parties that run under a joint ticket (explicitly listed, such as the DAB and FTU, instead of with the use of a new label, such as the 7-1 United Front), the vote share obtained by the ticket is treated as the figure obtained by each of the affiliated parties.Footnote 11 To capture popular support, survey data from the University of Hong Kong Public Opinion Programme (HKUPOP) (2017) are used. This project regularly conducts telephone surveys using randomly generated phone numbers, which is considered to be a method capable of returning a largely representative sample of the Hong Kong population.Footnote 12 Respondents are asked to indicate their level of support for major political parties on a scale of 0–100.Footnote 13 The level of support immediately after an election is used as the second dependent variable. The following equation is estimated:

where Support i,t is the vote share/support rating of party i in the election at time t, μ is the vector of control variables (discussed below), β 1 … k are coefficients to be estimated, α denotes the intercept, ν is the party fixed-effects, and ε i,t is the error term. Robustness tests with election (time) fixed-effects are presented in the Appendix. It should be noted that a significant result does not necessarily mean that ideology causally explains support (or vice versa), but only that the electorate as a whole lean towards a certain direction, given the correlation between vote share/support rating and parties’ ideological standing. For the RILE measure, a positive (negative) coefficient points to a more right-wing (left-wing) electorate; the reverse holds for the Welfare measure. Additional tests assess the temporal changes by separating the models before and after 2008.Footnote 14 More formally, interaction models are used by including a time variable (the number of years since 1998) alongside the interaction term with ideology. To control for vote share, the number of legislators affiliated with the party before the election, the number of other parties competing in the constituencies the party ran in (as each party will receive less votes with more lists in a proportional election), and the number of districts the party competed in are all included. For popular support, a dummy variable for whether a party has an incumbent legislator at the time of election and the number of elected district councilors affiliated with the party (in natural logarithm as the distribution is skewed) are used as controls.

ANALYSIS

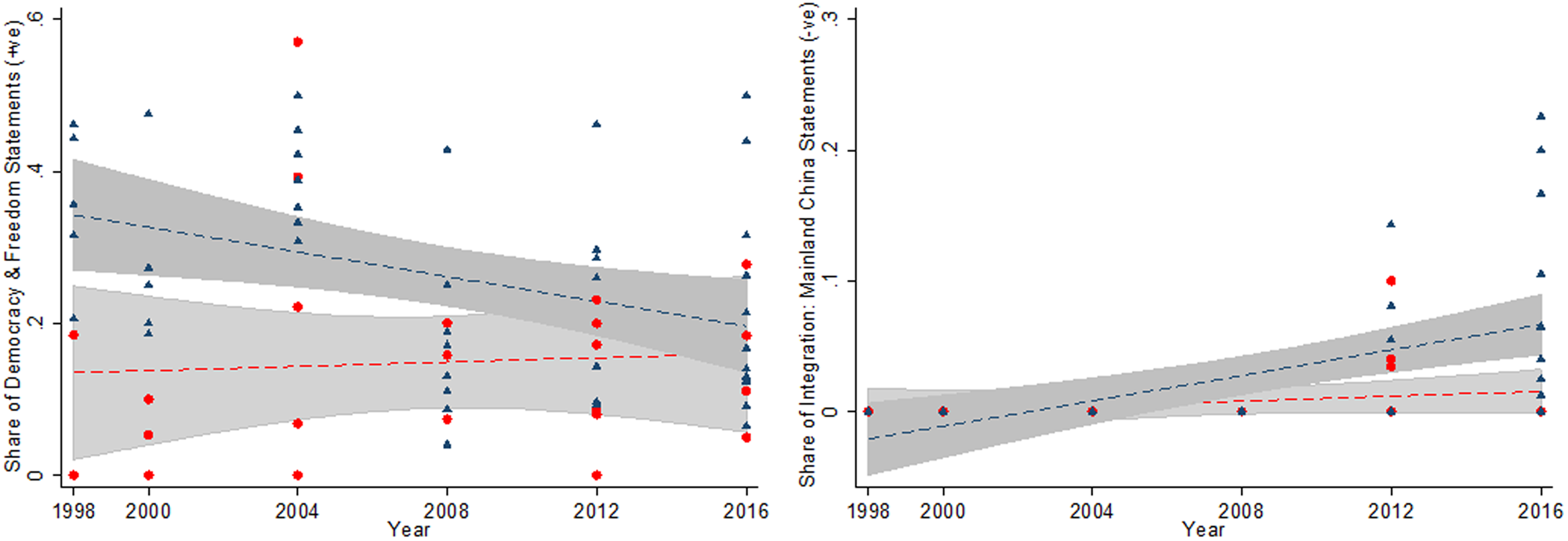

To demonstrate the prima facie validity of the MARPOR in Hong Kong, I apply the framework to examine the well-established pro-democracy/pro-Beijing divide. As discussed, the pro-democracy camp generally advocates more rapid democratization and puts a greater emphasis on human rights and freedom (Ma Reference Ma2007; Wong Reference Wong2017). Using the appropriate coding instructions from MARPOR, Figure 1 shows the share of all positive references to “democracy,” “freedom,” and “human rights” contained in each party's manifesto by political camp. The confidence intervals show that the two camps take distinct positions on this dimension up to 2012 (when the differences were no longer significant) and 2016 (when there was virtually no difference).Footnote 15 Two explanations can be offered for this shift. First, in 2010 the DP reached a compromise with the government on a limited political reform proposal, which was heavily criticized by its allies. This dampened democrats’ unified calls for universal suffrage, as well as allowing some pro-Beijing parties to also claim support for ideas like “democratic progression.” Second, in the aftermath of the Umbrella Movement, many pro-democracy parties relegated their traditional focus on democracy to the background in the 2016 election. Instead, the development of the discourse of localism and the fear of the erosion of Hong Kong's autonomy (Kaeding Reference Kaeding2017; Fong Reference Fong2017) brought the issue of Hong Kong's political future to the forefront and even led to the formation of localist parties. As shown from the panel on the right side of Figure 1, negative references to integration with mainland China first entered the electoral arena in 2012 (in fact, not a single such sentence exists until that date for any party) and became a significant cleavage between the two camps in 2016.Footnote 16 From this brief analysis, it can be seen that the MARPOR quantitatively captures the established competition pattern in Hong Kong reasonably well, according to our understanding of local politics, while also adding valuable additional insights.

Figure 1 Manifesto Coding and the Political Divide in Hong Kong

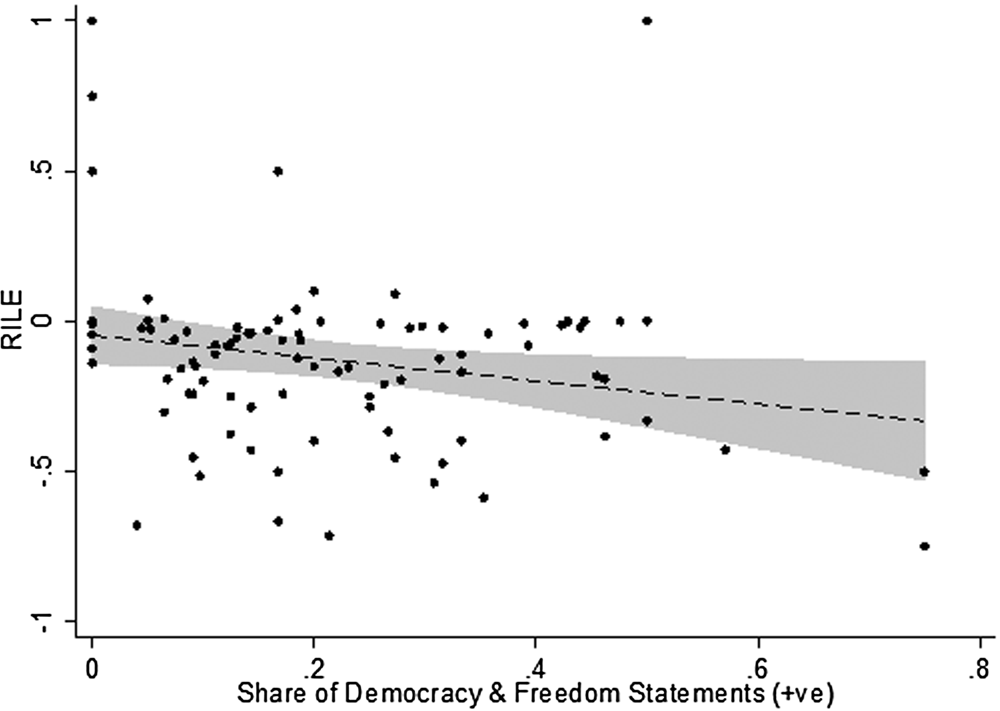

The adopted ideology measures also need to be evaluated, given that socioeconomic ideology is not considered as a dominant dimension of party competition in Hong Kong. To check whether the left–right ideological dimension overlaps with the primary divide, Figure 2 plots the RILE scores of all observations against their corresponding share of positive democracy/freedom references (the scale used in Figure 1). Although the fitted line is downward-sloping (a more pro-democracy party would take a more leftward position on average), the differences are not significant (the lowest boundary of the interval at x = 0 overlaps with the top at the other end of the spectrum). Plots of RILE and Welfare by political camp over time, similar to those in Figure 1, tell a similar story (as shown in the Appendix). Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that the socioeconomic ideological dimension, if it exists, is distinct and orthogonal to the primary political divide in Hong Kong.

Figure 2 Left-Right and the Pro-Democracy/Beijing Divide

The next analysis compares MARPOR data with expert surveys. Figure 3 plots the trends of RILE scores of the DP and the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment of Hong Kong (DAB), the flagship pro-democracy and pro-Beijing parties, respectively. The reference series is the expert scores for the two parties provided by the CSES (left axis; available up to 2008). It can be seen that the manifesto and expert scores demonstrate very similar trends for DAB, concurring in the finding that the DAB drifted leftward between 2000 and 2004 before bouncing back to the right in 2008. The figures for the DP require more discussion because the changes from 2000 to 2004 were in opposite directions, with the RILE recording a large movement toward the right while expert judgment suggests that a slight leftward shift took place. The DP experienced a major factional struggle during this period between the mainstream elites and the “Young Turks” (Ma Reference Ma2001). One of the key disputes between the two factions was whether to include support for a minimum wage in the official party program. The initiative was put forward by the Young Turks, who argued that the DP should adopt a more pro-labor position (Ma Reference Ma2001). The struggle ended with the victory of the mainstream faction, which adhered more to a free market ideology, and the exodus of the Young Turks in 2002. Therefore, it would be more reasonable to expect that the DP would move toward the right in 2004 without the counterbalance of the pro-labor faction. This is reflected in the figures based on manifesto coding but not the expert scores, providing some confidence in the former's validity and utility. Indeed, while the various DP's platforms in 2000 had a total of nine references to “Market Regulation: Positive” and “Controlled Economy: Positive,” the corresponding figure dropped to two in 2004.

Figure 3 Manifesto Coding and Expert Scores of Two Major Parties

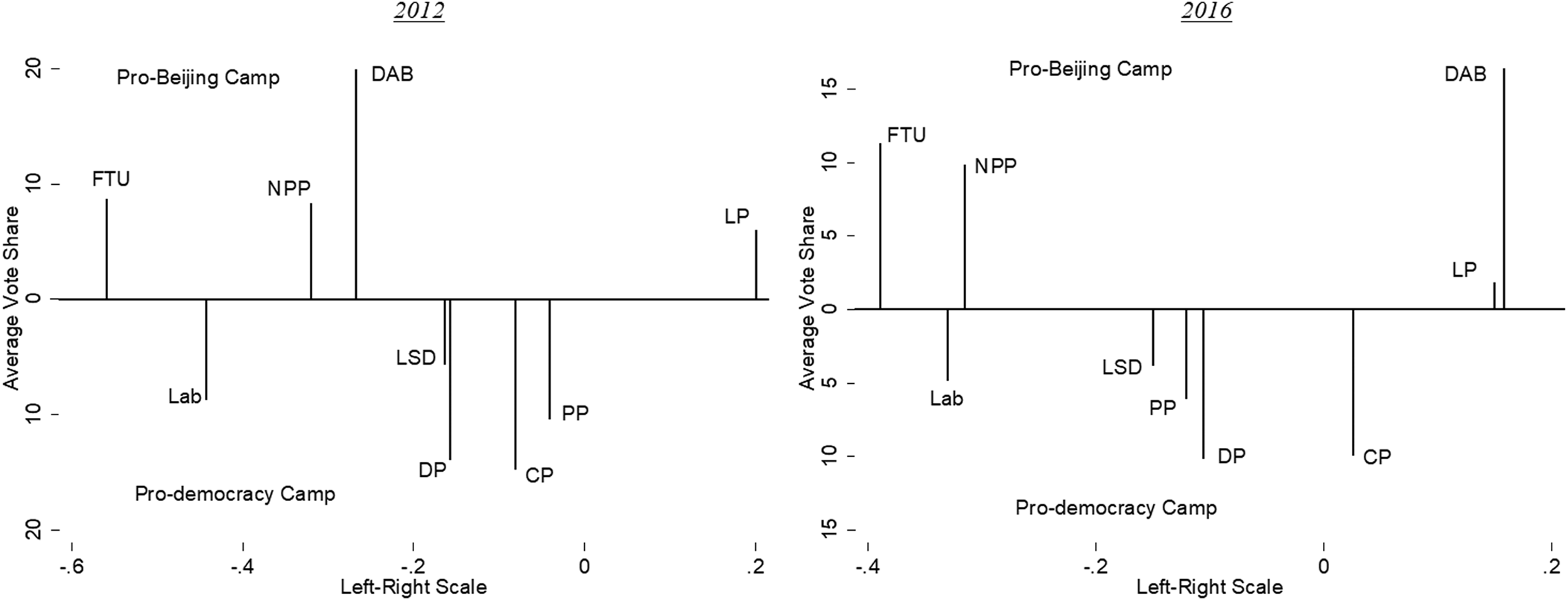

Figure 4 assesses the dynamics between ideological platform and electoral performance in the elections in 2012 and 2016. Pro-Beijing and pro-democracy parties are shown at the top and bottom of the figure, respectively. In both elections, it can be seen that pro-democratic parties collectively tended to adopt more centrist positions, as compared to the more diverse pro-Beijing camp. These results corroborate the fact that middle class and educated voters tend to support the pro-democracy camp (e.g., Ma Reference Ma2007; Wong Reference Wong2014). In 2012, the LP and the FTU served as the pro-Beijing camp's right- and left-wing parties, respectively, whereas the DAB and NPP appealed to voters in the middle. However, the LP was rather weak electorally and, more importantly, fell out of favor with Beijing.Footnote 17 In 2016, the DAB adopted a position similar to that of the LP. Although this move brought with it a lower vote share for the DAB, it benefitted both the FTU and NPP and offered a more attractive right-leaning party for pro-Beijing supporters. As this left a large vacuum in the middle for the camp, it is doubtful that this ideological shift would be long-term; in fact, following the formation of the new BPA (which had not yet fully participated in direct elections in 2016) to replace the LP as the dominant pro-Beijing pro-business party, it is expected that the DAB will revert to its centrist position in the upcoming election. The positioning of the pro-democracy parties also fits with our expectation. In 2012, the Labour Party was the camp's left-wing choice, followed by the LSD, which was a self-proclaimed social democratic party. The DP and the CP were in the middle, with the latter slightly to the right with its elitist and professional appeal. The PP's right-wing position also sparked some controversy in that election. In contrast to the pro-Beijing camp, the balance within the pro-democracy camp was rather stable over the 2012–16 period, the only exception being the PP moving from a right-wing to a centrist position in 2016. The PP experienced a major split, which saw the departure of one of its founders, and the organization became very different from what it was in 2012. It is interesting to note that the PP formed an election alliance with the LSD in 2016, which might explain why their positions were so similar from a manifesto coding perspective (even though they had unique manifestos). These descriptive accounts all demonstrate how the positional data generated from manifestos can allow us to meaningfully interpret and analyze political competition dynamics among parties in Hong Kong.

Figure 4 Ideological Position and Legislative Election Results

The subsequent assessment is of the change in voter ideology over time. As no primary data on voter ideology are available over long periods (given that the last CSES was in 2008), we use the manifesto coding data to estimate the aggregate ideology of the entire electorate. The overall voter ideology is estimated using the position of each party weighted by their vote shares in that election (the slightly more complex methodology suggested by Kim and Fording (Reference Kim and Fording2003) to estimate the median position yields similar results). Note that this exercise does not posit any causal effect but assumes a certain level of endogeneity between party positions and election outcome. Nevertheless, the results are also illustrative of the preferences of the general electorate. As a simple illustration, a leftward change in overall ideology means that voters cast their votes for more left-leaning parties (assuming parties do not change their positions) or parties shift their platform leftwards (assuming voters’ support for each party is unchanged). Of course, both assumptions are unrealistic, but the point is that the score reflects a real change in the ideology of the entire electorate of Hong Kong.

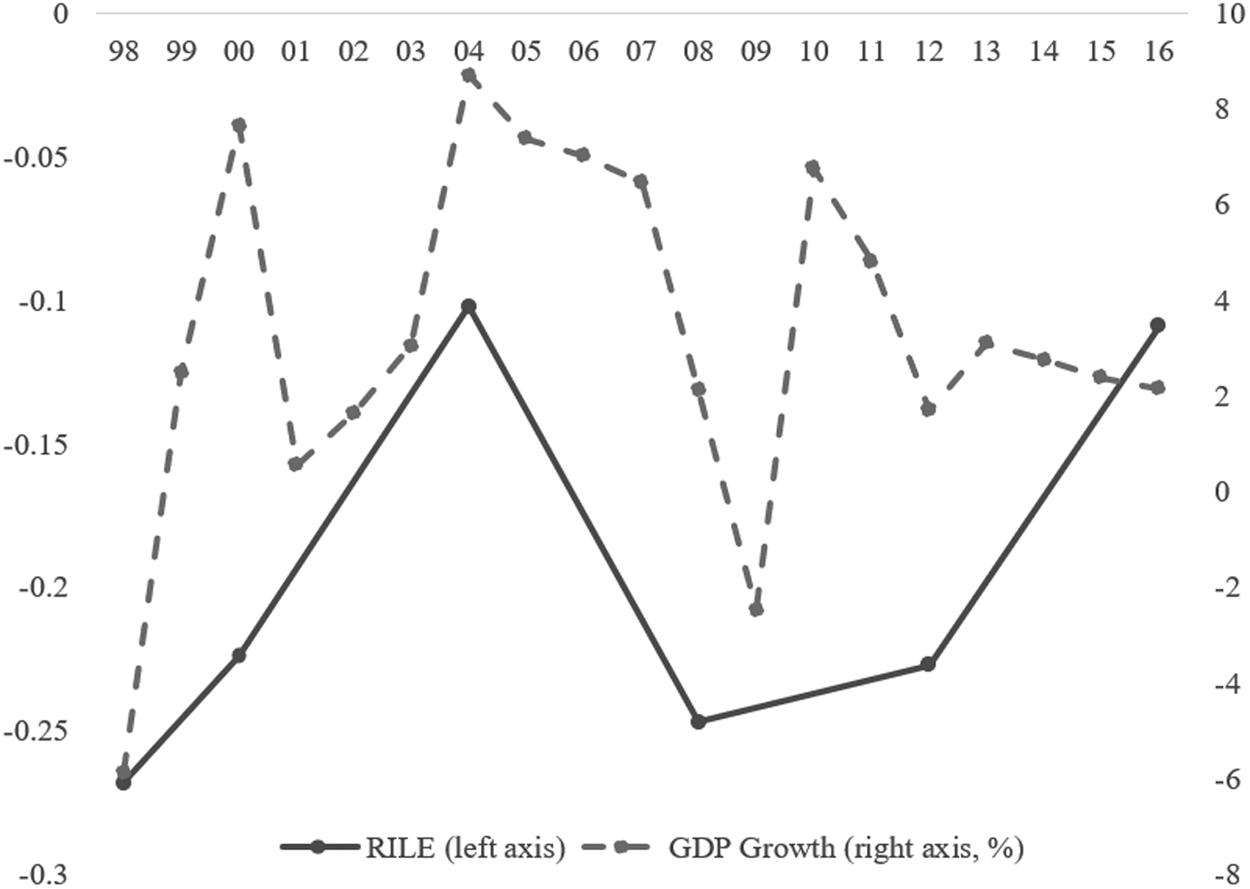

The figures for each election from 1998 to 2016 are shown in Figure 5 (solid line; left axis). It can be seen that the overall ideology of the Hong Kong electorate has indeed changed over time (although the changes were not large relative to the full range of RILE from −1 to + 1). It is argued that this change may be caused by volatility in the economic environment. To examine this, the GDP growth rate for Hong Kong is also plotted in the figure (dotted line; right axis). For example, the electorate shifted to a relatively left-wing position (more negative scores) during the 1998 Asian financial crisis and again during the 2008 global financial crisis, both of which coincided with a recession in Hong Kong (1998 and 2009 being the only two years of negative growth over the last two decades). On the other hand, the overall rightward shifts in voter ideology often took place during periods of strong economic growth. The two series also correlate at r = 0.56. This finding is in line with the wider literature on support for redistribution, which suggests that it drops in times of prosperity as personal income rises. Conversely, redistribution is thought to be more popular during economic downturns as people seek protection against unemployment and poverty (e.g., Blekesaune Reference Blekesaune2007; Jaeger Reference Jaeger2013). An anecdotal example is the LP, the only pro-business party consistently running in direct elections. In 2008, its leader James Tien's manifesto contained notable mentions of “Controlled Economy: Positive” and “Equality: Positive,” none of which were found in his 2012 manifesto. The LP as a whole also moved substantially rightward in 2012.

Figure 5 Estimated Aggregate Voter Ideology in Hong Kong, 1998–2016

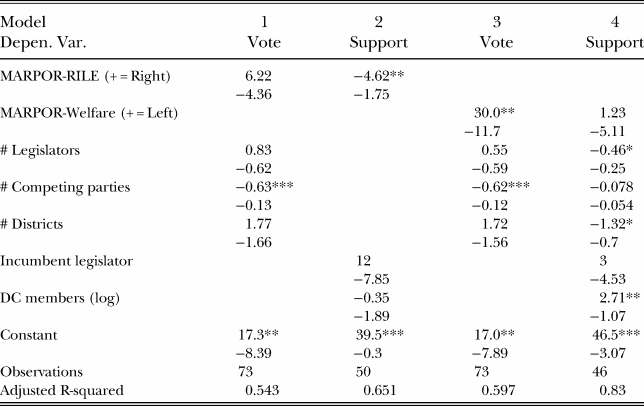

We turn to the regression results next, presented in Table 1. Although RILE does not reach conventional levels of significance with vote share as the dependent variable (Model 1), it does become significant (p < 0.05) for the political support model (Model 2), indicating a correlation between left-wing ideology and stronger support. On the other hand, the welfare sub-measure (Welfare) is significantly correlated with vote share (Model 3) but not general political support (Model 4) (recall that Welfare is operationalized in the opposite direction to RILE). It is interesting to note that RILE and Welfare are significantly associated with political support and vote share respectively, but not the reverse. This pattern will be further discussed below.

Table 1 Ideology and Political Support

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. OLS estimates. The dependent variables are the average vote share obtained by the party in legislative elections and the level of support in HKUPOP surveys. Party fixed effects are included but not reported. Standard errors are in brackets.

The temporal dynamics of ideology and political support are assessed in Table 2 by splitting the estimation into two time periods, with 2008 as the cut-off. While RILE is more prominent in the recent period (significant at p < 0.01), it is insignificant in the period before 2008; again, Welfare displays the opposite pattern. Models 9 and 10 test the changing effects of ideology more formally by using an interaction model. It should be noted that in interaction models the coefficient and significance of each constituent term becomes less important than the joint significance of the constituent terms and their interaction (Kam and Franzese Reference Kam and Franzese2007). An F-test shows that these two sets of interactions are significant at p < 0.05 (Model 9) and 0.01 (Model 10). The results are also in line with those in Models 5 to 8. A negative interaction term for RILE indicates that RILE's correlation with political support becomes more negative with time, whereas Welfare becomes less positive in more recent elections.

Table 2 Effect of Ideology Over Time

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. OLS estimates. The dependent variable is the average vote share obtained by the party in legislative elections. Party fixed effects and control variables are included but not reported. Standard errors are in brackets.

Besides statistical significance, the results are also substantively significant. Based on the estimates of Models 2 and 3, a one-standard-deviation change in RILE (0.28) is associated with a shift in 0.28*−4.62 = 1.29% in political support; a similar change in Welfare (SD = 0.08) would come with a 0.08*30.0 = 2.4% change in vote share. Alternatively, a hypothetical shift from a right-wing position (e.g., the pro-business and pro-Beijing LP; RILE = 0.15) to the left (e.g., the pro-labor FTU of the same camp; average RILE = −0.31) would come with a (0.15 + 0.31)*4.62 = 2.13% increase in vote share. While it is acknowledged that the results are not statistically significant across all models, these estimated changes should be considered rather significant in the context of electoral competition.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This article concludes by discussing the findings and their implications. Building on an established framework, this study contributes to the literature by creating an original party manifesto coding dataset, allowing for an objective assessment of parties’ ideologies and positions. This yields two important findings. First, the primary political division of pro-democracy versus pro-Beijing has undergone a shift away from the traditional concerns. While the major differences between the two camps had previously been on the issues of democratic progression and individual liberties, this was superseded in the 2016 election by the acceptance or rejection of integration with mainland China. This provides some empirical underpinnings of the rising discourse of “localism.” Applying the framework to the upcoming elections would allow us to determine if this change is solidified by the recent protests, or if the wave of localism has already been subdued by the government's electoral manipulation. Second, the dataset enables us to empirically test the relationship between party ideology and political support in Hong Kong. Contrary to popular impressions of a non-ideological system, I contend that parties do position themselves along a left-right socioeconomic ideological spectrum, and voters do formulate their preferences along the same dimension. Although the exact causal relationship of ideology, party position, and voter support cannot be ascertained (due to likely endogeneity), the clear-cut ideological dimension found in this article provides evidence challenging the conventional non-ideological view of party competition in Hong Kong. Regardless of their political persuasion (pro-democracy or pro-Beijing), parties take positions (as signified by their manifestos) on the socioeconomic left–right spectrum generally in line with their party labels and support base; notable shifts in positions can be logically explained in terms of political competition dynamics; and aggregate voter ideology can be linked to the wider economic environment. Such a finding enriches our understanding of parties and their roles in the political system in Hong Kong beyond the pro-democracy/pro-Beijing dimension and into the more contentious issues of freedom, China–Hong Kong relations, and identity.

Regression results also corroborate the above findings and can provide some nuanced observations. In general, a left-wing position is found to be correlated with stronger support, reinforcing the existence of an ideological dimension in the political arena. However, the full ideology measure (RILE) is only significantly associated with the general level of popular support and the welfare sub-measure (Welfare) only with vote share, but not the reverse. This may be due to the fact that people in general agree with leftist ideology (demonstrating a stronger support in polls) but this does not always translate into votes. Voters seem to be more pragmatic and economically rational in elections, as parties can only gain more votes by adopting a stronger pro-welfare position (rather than by espousing general left-wing ideologies). As for temporal changes, RILE is found to have a stronger association with political support in more recent elections, while the coefficient of the welfare sub-measure is only significant in the earlier period. This might hint at voters in Hong Kong previously focusing more narrowly on welfare policies in elections but gradually developing a more comprehensive understanding of left-right ideology over time. Of course, the explanations offered here are speculative, and a detailed investigation must be left for future studies.

Two additional characteristics are worthy of discussion. First, it is noted that the party system in Hong Kong is left-leaning overall based on the MARPOR framework (Figure 5 and the RILE scores in the Appendix). Second, the effect of ideology is not consistently significant statistically (based on the choice of measures and time discussed in the previous paragraph). Hong Kong is commonly characterized as a hybrid regime with a “stunted party system,” which precludes the possibility of a ruling party (Lau and Kuan Reference Lau and Kuan2002; Wong Reference Wong2015). The head of the government, the Chief Executive, cannot be affiliated with any political party. In such a system, political parties, pro-Beijing or pro-democracy, can only have constrained roles in the legislature, with limited opportunities to realize their platforms.Footnote 18 In these circumstances, political parties do not need to consider the financial consequences of their platforms, and should always advocate greater welfare in an attempt to maximize their appeal towards the general electorate. This is compounded by the fact that the legislature has reserved half of the seats for business sectors returned by indirect elections, in which parties can safely ignore popular preferences and focus on business interests (which will generally reflect right-leaning ideologies).

In a similar vein, because parties do not have genuine policymaking power, voters may not pay much attention to their platforms when casting their votes, resulting in the lack of a more consistent relationship or the general impression that ideology is not very important. Given the greater prominence of the concern over the relationship with Beijing, it is also implausible for voters to switch their allegiance to a similarly positioned party from the opposite camp. Although this study partially challenges the myth of a non-ideological party system, it is acknowledged that this factor will remain subordinate to the pro-democracy/pro-Beijing divide (or the potential variants of this divide in the future).

A final limitation is perhaps more fundamental: this is the question of whether political parties and elections are in fact still relevant in Hong Kong. Although the 2016 legislative election set the stage for the rise of a new opposition advocating greater autonomy, they were wiped out by hardline responses from the government/Beijing (which disqualified elected legislators and barred others from candidacy). At the time, this might have seemed prudent as it handed the pro-Beijing camp an advantage in the legislature and forced other pro-democracy politicians to fall back in line (by distancing themselves from anything that might seem too “radical”). However, that lack of any formal representation of these ideas in the system might have radicalized the supporters of these opposition groups and led to the recent unprecedented waves of protests. Given the repeated clashes and instability, with no apparent end in sight, there was even discussion of suspending the district elections in 2019 using emergency powers (which did not happen eventually). These worrying developments are not only disruptive to the normal functioning of political institutions in Hong Kong, but also call into question the very role of local parties and elections. While electoral competition and opposition dynamics in hybrid regimes and dictatorships is an emerging area in the literature, it is hoped that the framework introduced here (for mapping party positions not only socioeconomically but also on matters of democracy, freedom, and autonomy) provides a more in-depth understanding of the main areas of contention.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author reports none.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2020.3.