One important factor that underlies political conflict around immigration concerns the ways in which natives perceive immigrants, with perceptions not necessarily reflecting the reality. Indeed, immigrants are often seen as poorer, less educated, and more culturally distant than they are (for a review, see Lutz and Bitschnau Reference Lutz and Bitschnau2022). Since all these attributes are usually seen by natives as undesirable for potential immigrants (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile, Hahn, Hansen, Harell, Helbling, Jackman and Kobayashi2019), negative perceptions are politically consequential. Existing studies show that variance in perceptions about immigrants – concerning their reasons for migrating, employment, and legality – predicts attitudes toward immigration (Blinder Reference Blinder2015; Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2021b).

The same logic should extend onto specific immigrant origins: natives likely form distinct perceptions about immigration from different countries and regions. These origin-specific perceptions have not yet received enough attention in the literature, but they have important implications for immigration policy opinions and anti-immigrant prejudice. If immigrants from some regions are seen as having desirable characteristics, whereas immigrants from other regions are believed to have undesirable ones, it can explain the presence of systematic discrimination against certain origins (Newman and Malhotra Reference Newman and Malhotra2018; Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2021a). Support for restrictive policies and stricter enforcement can be higher if immigration is seen as coming primarily from regions associated with undesirable attributes.

In the present paper, I address this gap by exploring Americans’ perceptions about immigrants from different world regions. In an original conjoint task with a multinomial outcome, I present respondents with profiles of hypothetical immigrants and ask them to guess whether each immigrant came from Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, or the Middle East. Results of the experiment demonstrate that immigrants from all world regions other than Europe are associated with poor English skills. Perceptions about immigrants from Latin America are particularly negative: they include welfare dependency and rule-breaking behavior. Immigrants from Asia, on the contrary, are seen as self-sufficient and law-abiding. Positive perceptions about European immigrants are exhibited by both white and nonwhite respondents, although they are somewhat weaker among the latter. Overall, these results show that Americans’ opposition to non-European immigration, and Latin American immigration in particular, may stem from negative perceptions. Methodologically, my analysis demonstrates how conjoint experiments with multinomial outcomes can help to answer important questions in political science.

Measuring perceptions about immigrant origins

Influential experimental studies suggest that Americans, as well as citizens of other industrial democracies, have broadly meritocratic preferences on immigration: they are ready to admit immigrants who have valuable skills, speak good English, and follow the rules – whereas country of origin has little effect (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile, Hahn, Hansen, Harell, Helbling, Jackman and Kobayashi2019). At the same time, there is no agreement in the literature regarding both absolute and relative role of origin in attitudes toward immigration. Indeed, Americans seem to differentiate between more and less desirable immigrant groups (Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2021a). Most prominently, attitudes toward Hispanics impact whites’ opinions on immigration, and featuring immigrants from Latin America in the media boosts nativism (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Branton et al. Reference Branton, Cassese, Jones and Westerland2011; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013). According to more recent evidence, immigrants from the Middle East can be another group that provokes particularly strong opposition (Konitzer et al. Reference Konitzer, Iyengar, Valentino, Soroka and Duch2019).

While there exists research on perceptions about immigrants vs. natives (Blinder Reference Blinder2015; Lutz and Bitschnau Reference Lutz and Bitschnau2022; Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2021b), perceptions about immigrants from specific countries or regions are usually not directly measured. Existing literature offers only suggestive evidence that mostly concerns perceptions about Hispanic immigration. For instance, white Americans think that immigrants from Latin American countries are more likely to not have legal status in the United States (Flores and Schachter Reference Flores and Schachter2018). Evaluations of Hispanic immigrants also more strongly depend on their skills and perceived transgressions (Newman and Malhotra Reference Newman and Malhotra2018; Hartman, Newman, and Bell Reference Hartman, Newman and Scott Bell2014), but these findings provide only indirect evidence for the presence of the corresponding negative perceptions. In addition, there is almost no research on perceptions about Asian immigrants, another group that is important for Americans’ opinions on immigration (Citrin et al. Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Malhotra, Margalit, and Mo Reference Malhotra, Margalit and Hyunjung Mo2013), as well as about immigrants from Africa and the Middle East.

Nevertheless, going beyond perceptions about immigrants at large and studying Americans’ beliefs about specific immigrant origins is important. Public support for policies and, ultimately, outcomes of the policy process depend on what members of the public think about populations targeted by the policies in question (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). Even though immigration policies are usually formulated in legally neutral terms, they often target specific immigrant origins. For instance, some of the strictest immigration enforcement policies enacted by the first Trump administration – such as family separation – have been seen as predominantly targeting immigrants from Latin America (Wallace and Zepeda-Millan Reference Wallace and Zepeda-Millan2020). Similarly, Trump’s Executive Order 13769 that suspended entry from six Muslim-majority countries located in the Greater Middle East was almost universally known as the “Muslim ban” (Collingwood, Lajevardi, and Oskooii Reference Collingwood, Lajevardi and Oskooii2018). Studying perceptions about immigrants from specific world regions can provide insights into why such policies are enacted and why they are supported by non-trivial shares of the U.S. public.

The goal of this paper is to understand whether there exist systematic differences in perceptions about immigrants from various world regions in the American public. To answer this question, I rely on an increasingly popular application of conjoint survey experiments that measure perceptions rather than preferences (Flores and Schachter Reference Flores and Schachter2018; Goggin, Henderson, and Theodoridis Reference Goggin, Henderson and Theodoridis2020; Myers, Zhirkov, and Lunz Trujillo Reference Myers, Zhirkov and Trujillo2024). In such conjoint designs, respondents are shown profiles of hypothetical individuals with several randomized attributes – but asked to categorize them rather than choose the preferred option. As observed choices in standard conjoint analysis are used to infer preferences, observed guesses about group memberships in classification conjoint experiments allow researchers to measure respondents’ perceptions about the social groups that profiles are categorized into.

Since I simultaneously measure perceptions about immigrants from multiple regions – Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East – my design deviates from standard conjoint experiments in one important respect. It uses a multinomial rather than binary outcome, and I use multinomial logistic regression to analyze data from the conjoint task.Footnote 1 This estimation strategy involves parametric assumptions about the error structure, but it does not interfere with the main benefit of conjoint experiments: the causal interpretation of estimated effects. Multinomial conjoint design has not been used in the literature before, but it is useful for experiments that measure perceptions.Footnote 2 Since perceptions are group specific, conjoint experiments that measure them must employ real-world group labels in categorization tasks – and the numbers of theoretically relevant groups in such applications are often greater than two. I make a methodological contribution by demonstrating how researchers can estimate and present the quantities of interest in conjoint experiments with multinomial outcomes – and how such experiments can be used to address substantively important questions in political science.

Data and method

Respondents for the online survey-experimental study were U.S. adults recruited in August 2022 on the Lucid Theorem platform.Footnote 3 It has been shown to yield samples comparable to national probability benchmarks, such as the American National Election Studies, in terms of the key demographics (Coppock and McClellan Reference Coppock and McClellan2019). The final sample in my experiment consisted of 1,979 respondents. Its characteristics were the following. The mean age was 45.1 years. The gender ratio was 48.5 male to 51.5 female. College education was reported by 45.1% of respondents. Median income was $40,000 to $44,999. In terms of race and ethnicity, 68.6% of respondents identified as non-Hispanic whites. Finally, 36.3% of the sample were Democrats, 30.7% were Republicans, and 33% were independents (Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2025).

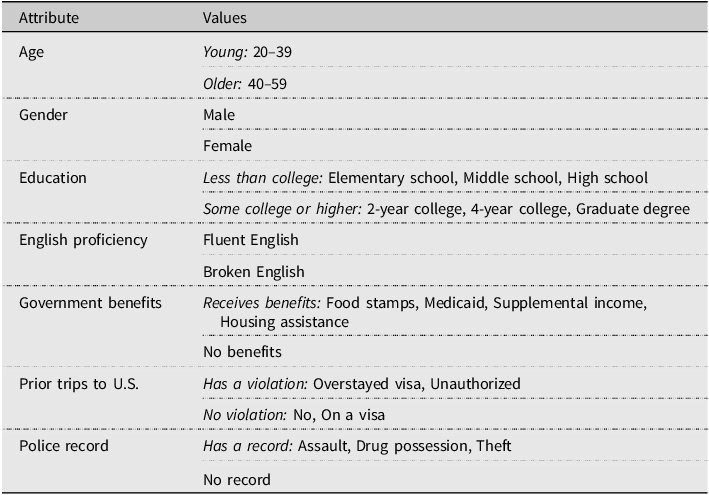

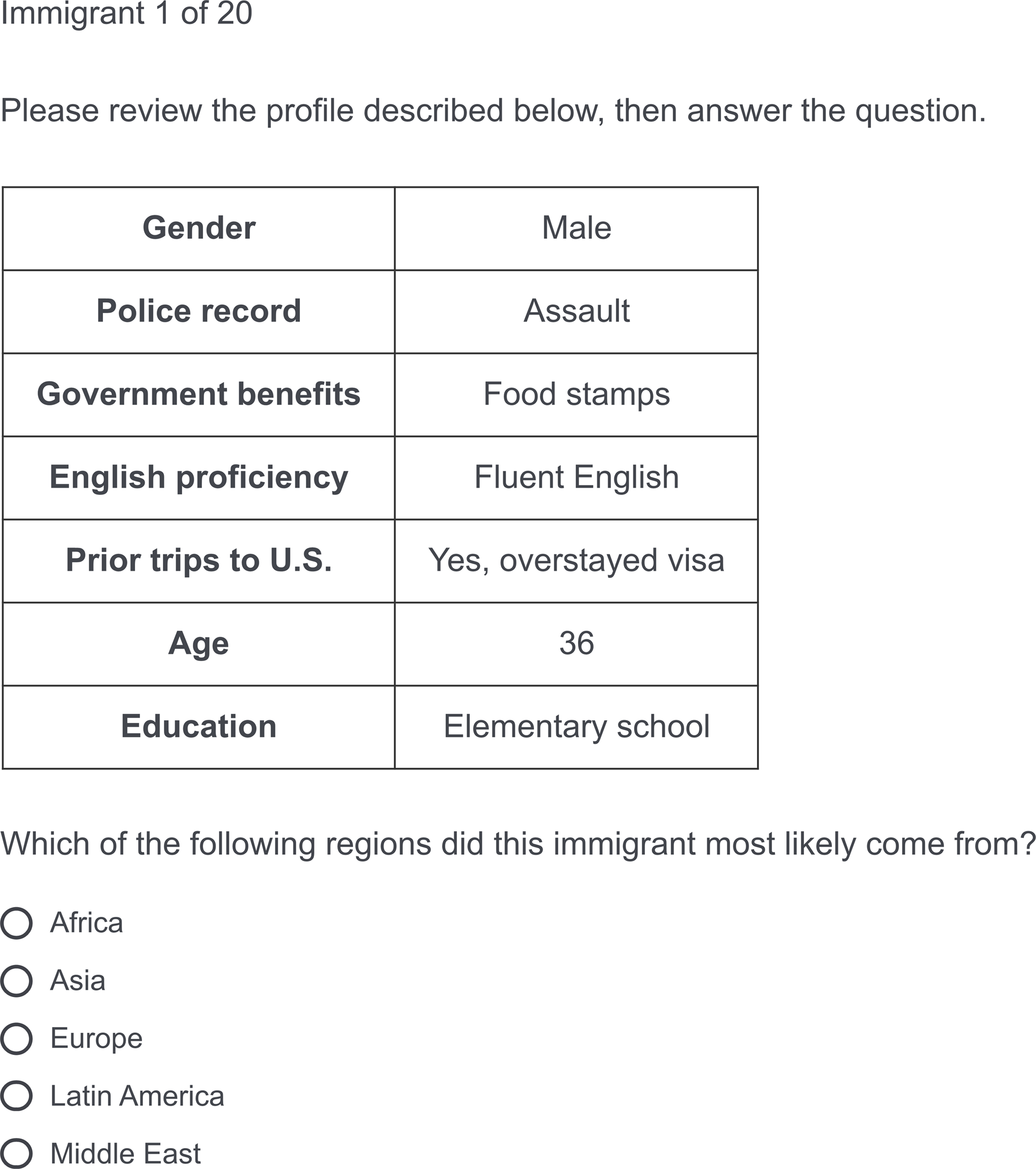

In the conjoint experiment, respondents were presented with profiles of hypothetical immigrants and asked to guess which world region each immigrant came from.Footnote 4 There were five categorization options for each profile: Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East. Each respondent was asked to categorize the total of 20 profiles, and only one profile was shown per a separate survey page. Each profile was described in terms of seven attributes that according to prior studies matter for public attitudes toward immigration: age and gender (Ward Reference Ward2019), education as a proxy for skill (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010), English proficiency (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2015; Newman, Hartman, and Taber Reference Newman, Hartman and Taber2012), receipt of government benefits (Garand, Xu, and Davis Reference Garand, Xu and Davis2017),Footnote 5 prior trips to the United States as a proxy for a history of status violations (Wright, Levy, and Citrin Reference Wright, Levy and Citrin2016), and police record (Hartman, Newman, and Bell Reference Hartman, Newman and Scott Bell2014). All these attributes were included in the seminal conjoint studies on either perceptions about unauthorized immigrants or preferences for immigrant admission (Flores and Schachter Reference Flores and Schachter2018; Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015). See Table 1 for the full list of profile attributes and their potential values.

Table 1. Attributes for immigrant profiles in conjoint experiment

Note. Age values (in years) were randomly chosen from the specified intervals.

The order of attributes was randomized between respondents but kept constant for each individual respondent. All attribute values were randomized independently with uniform distributions. Attributes for government benefits and police records each had one value where only one label was present, whereas the other value included multiple labels. Therefore, each profile had a 50% probability of being described as having no benefits or no record. The specific labels for profiles described as having government benefits and police records had equal probabilities of being presented. See Fig. 1 for a sample profile.

Figure 1. Sample conjoint profile as shown to respondents.

The survey also included a battery of items that measured respondents’ level of ethnocentrism (Bizumic and Duckitt Reference Bizumic and Duckitt2012). See Section B of Online Appendix for the questions.

Results

Respondents in the conjoint experiment categorized the total of 39,568 hypothetical immigrant profiles.Footnote 6 Of them, 16.2% were guessed as coming from Africa, 15.8% from Asia, 25.0% from Europe, 28.2% from Latin America, and 14.8% from the Middle East.Footnote 7 I analyze the data using a multinomial logistic regression that predicts profile categorizations based on specific attribute values. I also aggregate some attribute values to keep the reasonable number of estimated effects. Following the standard practice of conjoint analysis (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014), standard errors are clustered on the level of respondents.

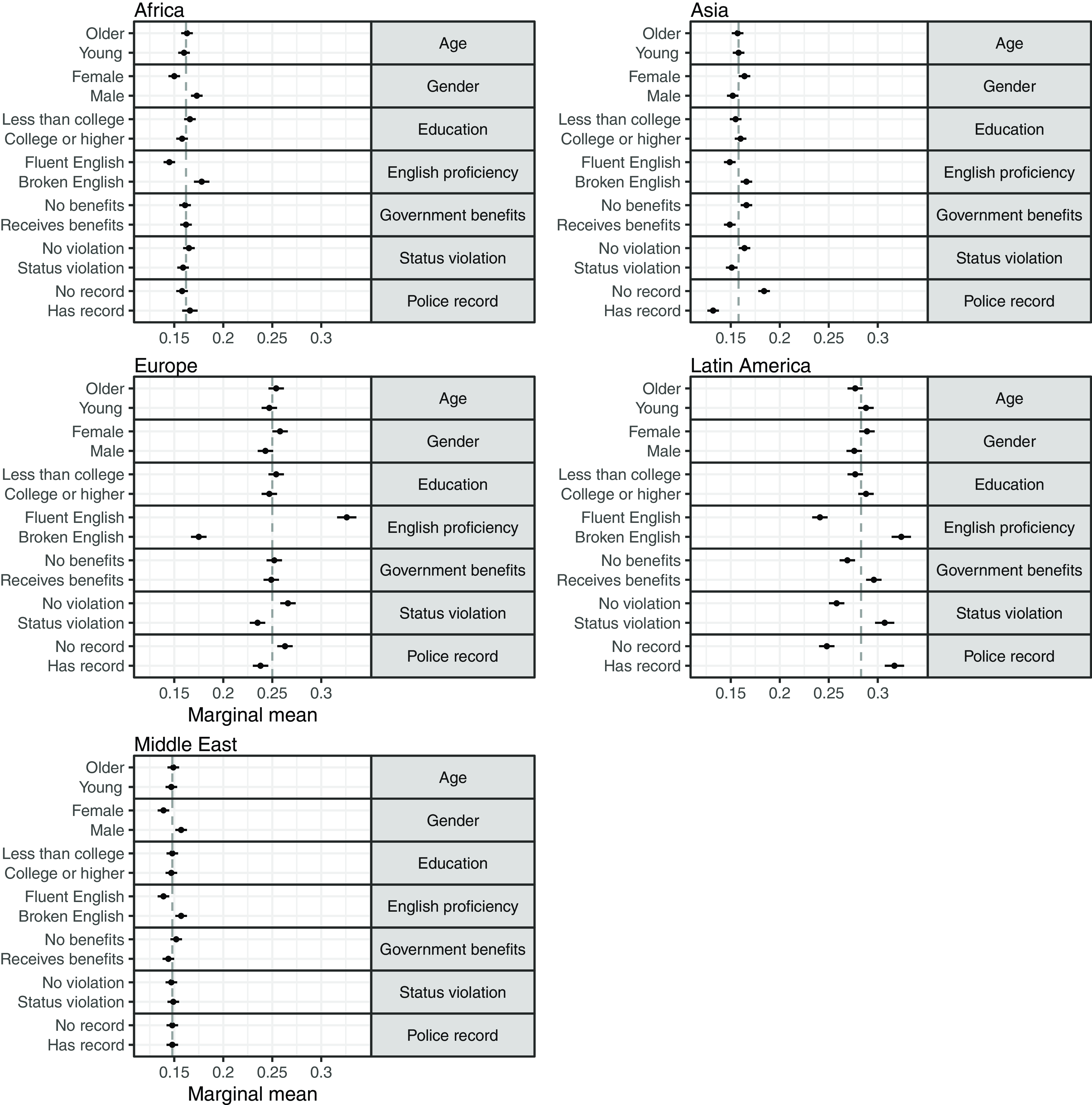

Results of the analysis are presented in Fig. 2 using marginal means (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020). Marginal means represent categorization probabilities for a profile with a certain attribute value while keeping all other attributes constant at their average values. To account for different average probabilities, results are grouped by the region. The most consistent finding is that speaking broken (as opposed to fluent) English strongly decreases hypothetical immigrant’s probability of being categorized as European and significantly increases classification probabilities for all non-European origins.Footnote 8 Probabilities of being classified as European are also higher for profiles described as having no police record and no immigration status violations. Surprisingly, respondents do not really use education levels (a proxy for skill) when categorizing immigrant origins. Still, European immigrants are associated with desirable attributes like knowing English and being law-abiding.

Figure 2. Conjoint results: marginal means.

Note. Dashed lines are region-specific average probabilities.

There are other interesting origin-specific perceptions. For instance, immigrants from Africa and the Middle East are gendered: being described as male increases a profile’s probabilities of being categorized as coming from these two regions. Not having government benefits, police records, and immigration status violations all positively impact guesses that hypothetical profiles belong to immigrants from Asia, indicating that the latter are seen as self-sufficient and law-abiding. Perceptions about immigrants from Latin America are the opposite: the categorization probability increases for profiles described as having government benefits, police record, and immigration status violations. Taken together, non-European immigrants are seen less positively than European ones, but this difference in perceptions is almost nonexistent for immigrants from Asia, while immigrants from Latin America are seen particularly negatively.

To explore the role of respondents’ racial identity and racial attitudes in perceptions about different immigrant origins, I estimate marginal means independently for whites and nonwhites and, then, for whites with high and low levels of ethnocentrism. These results are presented in Sections D and E of Online Appendix. They show that whites and nonwhites generally have the same associations between immigrant origins and the attributes of interest. At the same time, nonwhites are slightly less likely to classify profiles as European and slightly more likely to classify them as African and Asian. There is almost no variation in perceptions across the levels of ethnocentrism among non-Hispanic whites.

Conclusion

In this paper, I report on results of an original conjoint experiment that measures Americans’ perceptions about immigrants from five world regions: Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East. I find that Americans think of immigrants from regions other than Europe as speaking poor English. In addition, immigrants from Latin America are seen as welfare-dependent and law-breaking, whereas perceptions about immigrants from Asia are the opposite. Fluent English and respect for laws can signal integration into the American society (Levy and Wright Reference Levy and Wright2020; Ostfeld Reference Ostfeld2017), whereas violation of immigration laws is known to provoke strong opposition among natives (Wright, Levy, and Citrin Reference Wright, Levy and Citrin2016). Independently of the specific mechanism, perceptions linking immigrants from outside Europe to undesirable attributes can lead Americans to oppose non-European immigration.

At the same time, my results do not show notable perceptions that connect different immigrant origins with higher or lower education levels. This is an important finding since education can be seen as a close proxy for skill that is known to strongly impact immigration preferences (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile, Hahn, Hansen, Harell, Helbling, Jackman and Kobayashi2019). However, this is just one possible interpretation of this result. For instance, respondents can see language as a more important cue for economic contribution than education or discount the value of non-Western education. Future experiments can try manipulating immigrants’ occupations as a different proxy for skill or including an attribute representing work ethic, such as employment status and/or effort to find employment.

Another interesting finding concerns the association between immigrant origins and reliance on government benefits. I demonstrate that the corresponding perceptions are not uniform: immigrants from Latin America are seen as more reliant on benefits than Europeans whereas immigrants from Asia are less so. This result can explain a recent controversy in the literature that concern “immigrationization” of welfare in the United States (Garand, Xu, and Davis Reference Garand, Xu and Davis2017; Levy Reference Levy2021). Do Americans increasingly see immigrants as welfare recipients? My results suggest that these perceptions vary across origins: some immigrant groups are seen as being more likely to receive government benefits than others.

When interpreting these findings, some limitations of the chosen conjoint design should be considered.Footnote 9 First, while classification-based conjoint analysis allows isolating the causal effects of the target’s attributes on guesses about its category membership, the task ultimately measures perceptions or mental associations (Goggin, Henderson, and Theodoridis Reference Goggin, Henderson and Theodoridis2020). These associations themselves are not causal in the sense of the Neyman–Rubin model, which is the standard way of thinking about causality in the modern social sciences. Second, forced-choice conjoint designs, like the one used in this study, produce estimated effects that are relative rather than absolute. For instance, the finding that immigrants from Europe are seen as speaking better English than those from the Global South does not necessarily imply that all Europeans are seen as speaking objectively fluent English. It is necessary to emphasize, however, that these limitations apply to any categorization-based conjoint experiment with a forced-choice outcome.

A separate question deals with the role of race in Americans’ perceptions about immigrant origins. Since the importance of ethnocentrism in U.S. public opinion is well documented (Kinder and Kam Reference Kinder and Kam2009), do positive perceptions about European immigrants indicate the presence of racial prejudice? My results do not provide a definite answer. Some perceptions indeed follow the “white vs. nonwhite” dichotomy: for instance, all non-European immigrant groups are believed to speak worse English. Others do not, however, since Asian immigrants are seen as more law-abiding than Europeans. These perceptions also show little variation across respondents’ ethnic and racial identities as well as across levels of ethnocentrism among non-Hispanic white respondents. Future studies can address this question more in-depth by collecting oversamples of Asian, Black, and Hispanic respondents and analyzing perceptions within those groups separately.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2025.5

Data availability

The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PTX4RU

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this project were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association and the Quantitative Collaborative Seminar at the University of Virginia. I am grateful to Matt Blackwell, Chris Carter, Dan Gingerich, Melle Scholten, and Rachel Smilan-Goldstein for their helpful comments.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Democratic Statecraft Lab of the Democracy Initiative at the University of Virginia.

Competing interests

I have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethics statements

This study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board for the Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Virginia (protocol number 4964). This study adheres to APSA’s Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research. See Section F of Online Appendix for further details.