Introduction

Assurance, defined as “a strategy of seeking to persuade another state that one harbors no aggressive intentions toward it” (Knopf, Reference Knopf2012, p. 383), is important but difficult to achieve. In contemporary East Asia, for example, one of the key issues is whether China has aggressive intentions toward neighboring countries. China has committed to peace with the slogan “peaceful rise,” later reframed as “peaceful development,” since the Hu Jintao era (e.g., Buzan, Reference Buzan2010). However, because of its growing military spending and provocative activities, other Asian countries are increasingly cautious about China’s intentions (e.g., Luo, Reference Luo2022). Although the failure to provide credible assurances can result in significant consequences, assurance remains an underinvestigated topic in general, and we still know little about how states can credibly assure other countries in particular.

One source of credible assurances is tying-hands costs. When domestic or international audiences impose costs on a country that fails to follow through on commitments to international peace, these costs can serve as a tying-hands signal, enabling the state to credibly reassure other states. However, there is insufficient empirical investigation into the existence and impact of such domestic and international costs. Regarding domestic audience costs for violating peaceful commitments, the evidence remains mixed. Concerning international reputation costs, only a few studies have examined whether, and under what conditions, such costs arise.

This study addresses the latter issue. While my interest is similar to that of Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro (Reference Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro2021), who examine international reputation costs resulting from violations of peaceful commitments, I argue that the magnitude of reputation costs differs between rivals and allies for an external country. Using the context of China-Japan relations, I conducted a preregistered survey experiment with a sample of 1,515 American adults. The experiment was designed as a harder test of reputation costs than that of Cebul et al. Overall, I find evidence of international reputation costs for violations of commitments to peace, especially for a rival country. However, respondents still express a desire to cooperate on issues of mutual concern, even when states are perceived as lacking credibility on other issues. The results obtained here suggest that, with some caveats, reputation costs can be a reliable mechanism for credible assurances.

Assurances, domestic audience costs, and international reputation costs

According to Knopf (Reference Knopf2012), there are four types of assurance: assurance as a component of deterrence, assurance as an alliance commitment, reassurance, and non-proliferation-related security assurance. In this paper, my focus is on reassurance – that is, how to signal non-aggressive or peaceful intentions toward other countries. Making assurances credible is a crucial task. If a state fails to assure other countries, it becomes difficult to make coercive diplomacy successful (Jakobsen, Reference Jakobsen2000), and/or a security dilemma is more likely to emerge (Glaser, Reference Glaser1997; Jervis, Reference Jervis1978; Kydd, Reference Kydd2000). Despite its importance, assurance remains an underinvestigated concept regardless of type, because previous scholars in International Relations (IR) have primarily focused on the credibility of threats rather than that of assurances (Cebul, Dafoe, and Monteiro, Reference Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro2021; Knopf, Reference Knopf2012). While recent studies have renewed attention to assurances (Cebul, Dafoe, and Monteiro, Reference Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro2021; Haynes and Yoder, Reference Haynes and Yoder2020; Pauly, Reference Pauly2024; Yoder and Haynes, Reference Yoder and Haynes2020), it is still unclear what makes assurances credible.

Scholars identify audience costs as a mechanism for credible assurances (Kydd and McManus, Reference Kydd and McManus2017; Quek, Reference Quek2017). Audience costs refer to domestic political costs that leaders incur when they fail to follow through on international promises (Fearon, Reference Fearon1994; Levy et al., Reference Levy, McKoy, Poast and Wallace2015). Since violating international commitments can damage a country’s reputation (Fearon, Reference Fearon1994; Guisinger and Smith, Reference Guisinger and Smith2002; Tomz, Reference Tomz2007) or demonstrate a leader’s incompetence (Smith, Reference Smith1998), domestic audiences have incentives to punish such leaders. Scholars argue that these audience costs, in turn, function as a tying-hands signal, thereby enhancing the credibility of commitments (Fearon, Reference Fearon1997; Morrow, Reference Morrow2000).

Nonetheless, whether domestic audience costs serve as a reliable source of credible assurances remains controversial. For instance, a survey experiment by Levy et al. (Reference Levy, McKoy, Poast and Wallace2015) demonstrates that U.S. citizens express greater disapproval of a president who fails to follow through on a commitment to staying out of a conflict. Using a similar experimental design, Quek (Reference Quek2017) also finds that domestic audiences punish a leader for violating a commitment to peace. On the other hand, in their replication study of Levy et al., Takei and Paolino (Reference Takei and Paolino2023) fail to replicate the findings of domestic audience costs associated with backing in, suggesting that the emergence of this type of audience cost may depend on time and context.

Then, how about international reputation costs? Reputation costs can be analogous to domestic audience costs as a tying-hands mechanism (Lupton, Reference Lupton2024; Post and Sechser, Reference Post and Sechser2024). Theoretically, international reputation costs are expected to bolster the credibility of assurances Kydd and McManus (Reference Kydd and McManus2017, pp. 334–335). The literature contends that not only domestic but also international audiences such as adversaries (Zhang, Reference Zhang2023) and allies (Crescenzi et al., Reference Crescenzi, Kathma, Kleinberg and Wood2012) can impose costs on a state that violates international commitments. By increasing international reputation costs, for example by committing to peace publicly, a state may credibly signal its peaceful intentions to other countries.

The literature on reputation is closely related to the concept of commitment credibility and the consequences of its absence. Violating a country’s international commitments is costly because it undermines the credibility of future commitments. States lacking peaceful reputations are more likely to face aggression from other countries (Crescenzi, Reference Crescenzi2018). This loss of credibility also hampers a country’s ability to elicit international cooperation, such as the formation of military alliances (Crescenzi et al., Reference Crescenzi, Kathma, Kleinberg and Wood2012; Gibler, Reference Gibler2008). Moreover, if the credibility of commitments is interdependent (Huth, Reference Huth1997; Schelling, Reference Schelling1966), the loss of credibility in one type of commitment (e.g., assurance) may lead to the erosion of another (e.g., deterrence), as the country’s overall reputation for honesty is damaged (Sartori, Reference Sartori2005).

Despite theoretical advances, systematic empirical investigation into the role of international reputation costs in the context of assurances remains limited. One notable exception is Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro (Reference Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro2021). In a survey experiment conducted in the United States regarding the Senkaku-Diaoyu Islands dispute between China and Japan, they find that the credibility of China’s assurances significantly decreases when U.S. citizens are informed that China violated previous commitments in a different dispute. Similarly, I expect that, on average, international audiences impose greater costs on a state that takes provocative actions such as massive military buildups when these actions are perceived as deviations from the country’s prior commitment to peace.

Scholars argue that a country’s commitment to peace can serve as a costly signal of benign intentions. For example, Fortna (Reference Fortna2003, Reference Fortna2004) shows that the breakdown of cease-fire agreements after a war can generate international audience costs, thereby increasing the durability of peace, especially when the strength of agreements is high. Fortna further contends that such commitments can function as a costly signal by tying a leader’s hands, although this assumption is not directly tested in her works. Therefore, I propose to test the following hypothesis:

H1: International reputation costs for a country that announces a massive military buildup are larger when audiences are informed that it can be considered a violation of its previous commitment to peace.

The emergence of international reputation costs may also be conditional. While this study’s focus is similar to that of Cebul et al., I advance their findings by examining the conditions under which reputation costs for violating assurances are greater. One important contextual factor influencing opinions on foreign policy is the distinction between rivals and allies, as it shapes what observers perceive as (un)desirable behavior (Mercer, Reference Mercer1996). Scholarship shows that the rival-ally distinction can induce opposition toward out-groups and favoritism toward in-groups (Carnegie and Gaikwad, Reference Carnegie and Gaikwad2022). The bad behavior of out-groups is often attributed to undesirable dispositions, eliciting punitive responses from observers. In contrast, similar behavior by in-group members is typically interpreted as situational, reflecting constraints and opportunities rather than inherent traits. Applying the concept of intergroup bias to an international relations context, Lyall, Blair, and Imai (Reference Lyall, Blair and Imai2013) find that, in Afghanistan, violence committed by the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) (an out-group) has a significant negative effect on support for ISAF, whereas violence by the Taliban (an in-group) is only marginally associated with negative attitudes toward the Taliban. They term this weaker punishment of in-groups relative to out-groups the “home team discount” (p. 682).

This pattern of intergroup bias can also manifest in the context of assurances. International audiences are likely to view an increase in military spending by a rival with concern, as it may reduce the security of their own country. In contrast, an ally’s military buildups may not generate high reputation costs, even if they could be considered violations of previous commitments, because such actions may be perceived as beneficial to the country’s security.

H2: International reputation costs due to violating an international commitment to peace are larger for a rival of a country of the audiences than an ally.

Research design

I test these hypotheses by focusing on the case of China-Japan relations and how U.S. citizens perceive them. I employ a survey experiment with a sample of 1,515 U.S. adults. The sample is nationally representative in terms of gender, race, and partisanship.Footnote 1 The survey was fielded in May 2024 via Prolific, a cloud-sourcing platform widely used for academic and scientific research in political science and international relations (e.g., Diamond, Reference Diamond2020; Takei, Reference Takei2024). Research shows that participants recruited through Prolific tend to be more diverse and provide higher-quality responses than those from other platforms (Peer et al., Reference Peer, Brandimarte, Samat and Acquisti2017).

There are at least three advantages to conducting an experiment in the United States using a scenario focused on China-Japan relations. First, the military buildups of both China and Japan are, and will continue to be, critical issues in East Asia. Though China previously committed to its peaceful rise/development, China’s military budget has significantly increased (Wu and Bodeen, Reference Wu and Bodeen2024). Meanwhile, Japan has also shown a willingness to pursue military buildups, despite its commitment to military restraint since World War II (Lind, Reference Lind2022).Footnote 2 These developments have intensified concerns among scholars and policymakers about the risks of a security dilemma and regional instability in East Asia. Second, U.S.-China-Japan relations provide an appropriate context for testing my hypotheses. China is, and will remain, a strategic rival of the United States, while Japan is one of its most important allies, particularly for regional stability in East Asia. It is therefore reasonable to expect that U.S. citizens would perceive China’s violation of its commitment to peace as unfavorable, but view Japan’s regression from pacifism less negatively, as Japan’s military buildup may be seen as desirable for U.S. interests. Third, given the general lack of detailed knowledge about international issues among most U.S. citizens (Council on Foreign Relations, 2019), it is unlikely that respondents are aware of the previous commitments made by China and Japan.Footnote 3

After answering questions on standard demographic and attitudinal characteristics, respondents read a hypothetical scenario about China-Japan relations that could occur in the future. The vignette begins with the following paragraph:

China and Japan are engaged in conflict over several security-related issues in East Asia, chief among these being ownership of the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands and the status of Taiwan. In the latter case, China has not abandoned the use of force as an option for resolving the Taiwan issue, while Japan has encouraged a peaceful resolution. Because of these Chinese-Japanese tensions, the stability of the East Asian region is of concern. Please read the hypothetical situation below and answer the following questions.

The Taiwan issue has become increasingly imminent following the Ukraine-Russian War (Worrell, Reference Worrell2023), and there is ongoing debate about whether U.S.-Japan alliance commitments would apply in the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan (Jash, Reference Jash2024), given that China has not renounced the use of force over Taiwan (Cash and Blanchard, Reference Cash and Blanchard2024). Therefore, it is appropriate to describe not only the direct dispute over the Senkaku-Diaoyu islands but also the Taiwan issue, where Japan is a potential third party.

This survey experiment employs a 2-by-2 factorial design, with respondents randomly assigned to one of four groups. The first treatment arm varies whether China or Japan announces a massive military buildup in 203X. The second treatment arm manipulates whether respondents are informed that this military buildup constitutes a deviation from the respective country’s previous commitment, while others receive no such information. Utilizing hypothetical scenarios in this manner allows researchers to avoid deception while ensuring the scenarios remain sufficiently realistic.

Foreign actors frequently use this type of framing when criticizing other countries, particularly adversaries. For example, U.S. politicians, media, and other domestic institutions have often highlighted inconsistencies between China’s commitments to peace and its subsequent behavior (e.g., Council on Foreign Relations, 2024). Conversely, China has repeatedly criticized Japan’s statements, and actions such as constitutional reinterpretations can be seen as deviations from its pacifist stance (e.g., King, Reference King2014). Notably, such criticism is rarely directed at Japan by U.S. actors, suggesting that reputation concerns are invoked differently depending on whether the observer is evaluating an adversary or an ally.

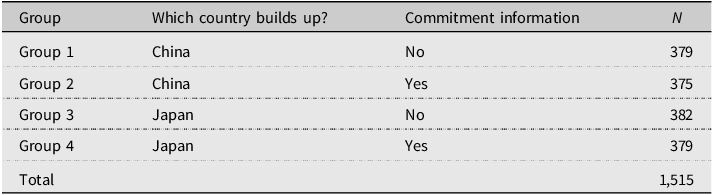

Table 1 summarizes the experimental design. My power analysis suggests that approximately 392 respondents per group are required (effect size = 0.2, alpha = 0.05, power = 0.8), which justifies the chosen sample size for each group.Footnote 4 Therefore, even if null results are found, it is unlikely that they are due to insufficient statistical power.

Table 1. Experimental design

After reading one of the vignettes, respondents were asked how likely they would be to believe commitments made by China or Japan in the future. I adapted the survey question from Levy et al. (Reference Levy, McKoy, Poast and Wallace2015) with slight modifications. As discussed, the loss of credibility by adversaries or allies can have significant international consequences (Crescenzi et al., Reference Crescenzi, Kathma, Kleinberg and Wood2012; Zhang, Reference Zhang2023). The measure uses a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (“Very unlikely”) to 4 (“Very likely”). As a robustness check, I also construct a dichotomous variable coded as 1 when the response is “Very likely” or “Somewhat likely,” and 0 otherwise. Both the 4-point scale and the dichotomous outcome variables were preregistered.

Following H1, I expect that U.S. citizens will perceive China’s and Japan’s future commitments as less credible when informed that current massive military buildups can be considered violations of their previous commitments to peace. Additionally, the operational hypothesis for H2 is that, given China’s status as a rival and Japan’s as an ally of the United States, the loss of commitment credibility will be greater for China than for Japan. H1 is tested through a series of t-tests.Footnote 5 If, for example, the credibility of China’s future commitments is lower when respondents are informed of the previous Chinese commitment to peace, that constitutes support for the hypothesis. For testing H2, I employ ordinary least squares regression models and linear combinations of the estimated parameters.Footnote 6

Results

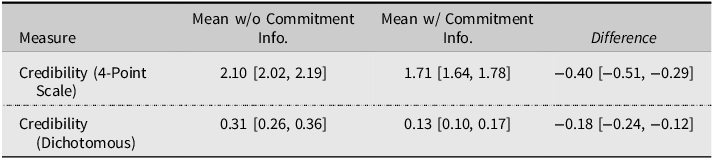

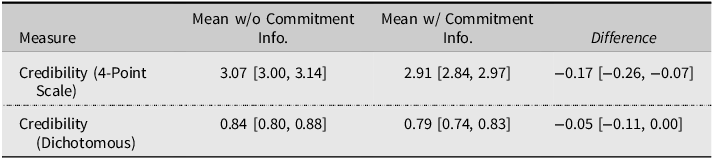

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the series of t-tests. Overall, I find evidence supporting H1 and H2. For China, when respondents receive information about its previous commitment to peaceful rise, there is a 0.40-point decrease in the 4-point scale (p = 0.000) and an 18-percentage point drop in the dichotomous measure (p = 0.000). Cebul, Dafoe, and Monteiro (Reference Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro2021) report that bad reputation decreases assurance credibility by approximately 0.30 points on a 5-point likelihood scale, so this effect size is slightly larger than theirs. The results for Japan show a similar pattern, but the evidence is weaker. When respondents are informed that Japan’s massive military buildup can be considered a breach of its commitment to military restraint, the mean of the 4-point scale measure drops from 3.07 to 2.91 (p = 0.001). However, the dichotomous variable indicates a 5-percentage point decrease that is not statistically significant (p = 0.056). The effect size of commitment violation is approximately twice as large (continuous measure) or three times larger (dichotomous measure) for China than for Japan. The results of the regression models and the linear combination of parameters reported in the Appendix show that the differences in international reputation costs between China and Japan are statistically significant (p = 0.002 for the 4-point scale, p = 0.003 for the dichotomous measure).

Table 2. International reputation costs (China)

Note: 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. The reported first differences may differ slightly due to rounding.

Table 3. International reputation costs (Japan)

Note: 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. The reported first differences may differ slightly due to rounding.

The results of a series of robustness checks on credibility are reported in the Appendix. First, I employ ordinary least squares regression models including a range of demographic and attitudinal variables (e.g., gender, income, partisanship, ideology, feelings toward, and knowledge of China and Japan). Second, I estimate the models after excluding inattentive respondents or those who failed manipulation checks. These adjustments do not alter the main findings. Third, using pre-treatment variables, I examine heterogeneous effects of the violation of peaceful commitments on commitment credibility. The results indicate that the effect is largely homogeneous across different demographic and attitudinal groups.

The findings of this study differ meaningfully from those of Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro (Reference Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro2021), who also examine the role of reputation in assurances, in at least three ways. First, Cebul et al.’s experiment supports only the independent effect of reputation; the interaction terms between a country’s power and reputation are not statistically significant in any model (pp. 985–987). In contrast, the present experiment confirms the expectation that the difference between a rival and an ally conditions the magnitude of reputation costs. This study thus corroborates the claim that IR scholars should shift their focus from whether reputation matters to under what conditions it does (Jervis, Yarhi-Milo, and Casler, Reference Jervis, Yarhi-Milo and Casler2021). Second, this study’s experiment constitutes a harder test of reputation costs than that of Cebul et al. In their study, the treatment context is a crisis in which China issues a threat coupled with a commitment to peace if the U.S. concedes; the subjects’ home country is directly involved in the dispute; and the commitment is specific. These conditions are conducive to the emergence of reputation costs (Press, Reference Press2005; Trager and Vavreck, Reference Trager and Vavreck2011). By contrast, in my study, although there is tension between China and Japan, there is no crisis or specific demand; the respondents’ home country is an outside observer; and the violation of the commitment is vague. Nonetheless, the current survey experiment provides support for both H1 and H2. Lastly, in Cebul et al.’s experiment, a past commitment violation is associated with more aggressive past behavior by China, conflating the causal effects of reputation with those of a different mechanism. In contrast, my survey experiment explicitly holds aggressive behavior (i.e., a military buildup) constant and varies only the commitment violation. Given these differences, the present findings make an important contribution to the emerging literature on reputation costs and assurances following Cebul et al.

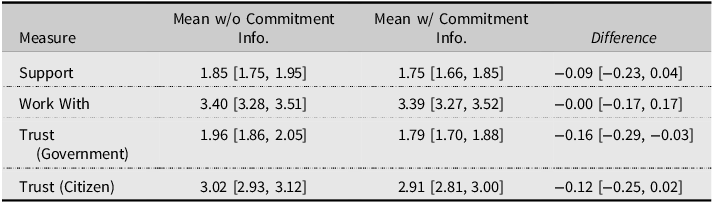

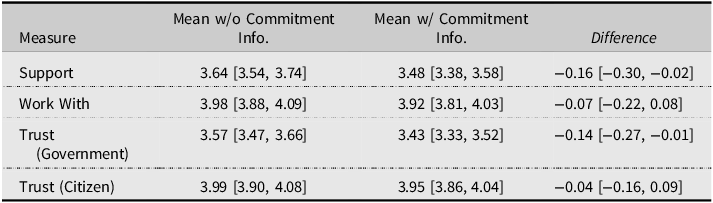

While the findings on credibility strongly support the hypotheses, one cautionary note is that, as reported in Tables 4 and 5, the results are not robust when alternative measures of international reputation costs are used. I constructed four additional measures of reputation costs: Support (the degree to which respondents support China’s/Japan’s change in foreign policy), Work With (the willingness to cooperate with the Chinese/Japanese government), and Trust in Government and Trust in Citizens of China/Japan. All variables use a 5-point scale. To be fair, evidence for H1 is stronger than for H2. Three out of eight results (China on Trust in Government, and Japan on Support and Trust in Government) are statistically significant, with the effect direction negative as expected. However, contrary to H2, I find no evidence across these alternative measures that China incurs higher reputation costs than Japan. Future research should investigate which forms of reputation costs arise from failures to honor peaceful commitments and under what conditions differences between rivals and allies become salient.

Table 4. International reputation costs (China)

Note: 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. The reported first differences may differ slightly due to rounding.

Table 5. International reputation costs (Japan)

Note: 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. The reported first differences may differ slightly due to rounding.

Conclusion

This paper examines whether and under what conditions international reputation costs arise from the violation of commitments to peace. The results suggest that, despite some limitations, these costs can serve as a reliable mechanism for credible assurances. While this study represents an important first step, there are several promising directions for future research. For example, although this study demonstrates the existence of reputation costs, whether such costs actually enhance the credibility of international commitments remains an open question, albeit one supported by the findings of Cebul, Dafoe, and Monteiro (Reference Cebul, Dafoe and Monteiro2021). Additionally, given that the magnitude of international reputation costs depends on the nature of relationships among states, a valuable avenue for future inquiry is to determine which countries face larger reputation costs under various conditions. Relatedly, decision-makers may be interested in strategies to increase international reputation costs to strengthen credible commitments. Prior research suggests that public threats tend to be more credible than private ones due to the greater political costs they impose (Fearon, Reference Fearon1997; Morrow, Reference Morrow2000; Takei, Reference Takei2024). Future studies could fruitfully explore whether the advantage of publicity similarly applies in the context of assurances.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/xps.2025.10005

Data availability

The data code and any additional materials (Takei, Reference Takei2025) required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HTD5WQ

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yu Aoki, Andrew Enterline, Austin Perkey, Meilin Li, Naonari Yajima, and Sung Min Yun for their feedback in the different stages of this project. The authors also extend their gratitude to the participants at Tecnologico de Monterrey’s departmental workshop and the panelists at the International Studies Association conference, whose comments significantly improved the manuscript. Finally, we thank our editor and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Funding

I gratefully acknowledge the support from the Suntory Foundation (2022W114) and Tecnologico de Monterrey for this project.

Competing interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics statement

The research adheres to the American Political Science Association’s (APSA) Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Tecnologico de Monterrey (Protocols: ECSG-24-009). Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The authors did not compensate participants directly. Participants were compensated for their participation by the survey panel provider (i.e., Prolific).