In 1961, officials in the Central Africa Federation (CAF) intercepted an inflammatory leaflet penned by a hitherto unknown organization called the Freedom for Africa Movement (FFAM).Footnote 2 The content of the leaflet, addressed to ‘our Loyal African Brothers,’ was anti-colonial in nature and, more distressingly for the CAF officials, seemed to be pro-communist. Attempting to evaluate the risk posed by the leaflet, CAF officials reached out to their British counterparts, hoping to obtain knowledge of the FFAM, an organization they believed to be operating across the African continent. This message created a minor stir within the British Foreign Office (FO). What sent FO officials into damage control was not the perceived danger of a new anti-colonial movement. Rather, the concern for the British was that CAF intelligence would investigate further, and in so doing expose a long-running fiction. For the British knew something the CAF did not: there was no Freedom for Africa Movement. The organization, and its propaganda apparatus, was entirely the product of the Information Research Department (IRD), a clandestine propaganda unit within the Foreign Office, which authored and distributed the Loyal African Brothers (LAB) leaflet series.

The task for the IRD, then, was to dissuade CAF officials from investigating the source of the LAB leaflets too thoroughly, lest they undermine a viable propaganda scheme. There was a certain sense of urgency brought on by the fact that British officials believed the CAF government led by Sir Roy Welensky was at this time convinced that an Africa-wide communist plot to overthrow white minority rule was afoot.Footnote 3 Noting that this belief bordered on obsession among CAF officials, IRD was concerned that unless dissuaded, Welensky’s government would publicize the discovery of the FFAM as evidence to prove their concerns were warranted. That the LAB series was conceived as a means of undermining the attraction of communism among African readers injected a degree of irony into this episode, which IRD officials were quick to note in their discussion on how to proceed.

Using recently declassified documents, this article engages with the Loyal African Brothers project in four sections. First, it provides a brief overview of the series: its founding, goals, distribution network, target audience, and brief biography of key IRD figures involved. The second section provides an institutional biography of the notional organization responsible for the LAB series: the Freedom for Africa Movement. Though fictional, the implicit ideology and identity of the FFAM provides insight into how IRD propagandists interpreted and responded to shifts in African political trends over the course of the 1960s. This section also discusses the material form and rhetorical character of the LAB leaflets, and how these were crafted to reflect a certain kind of authenticity for African readers. I argue that the vocabulary of the leaflets and the profile of the FFAM reflect broader British conceptions of the nature of African politics, print cultures, and intellectual capacity. If propaganda is commonly conceived of as a component of psychological warfare, then I argue that the psychology of the propagandists is as important as that of the audiences they hope to influence, making the LAB important for broader understandings of the racial and ideological contours of British foreign policy in the 1960s. The final section analyzes key themes of the series through a close reading of two leaflets, highlighting the specificity of content directed at African audiences in their focus on Ghanaian subversion and Arab imperialism.

This article addresses an Africa-sized hole in much of the contemporary scholarship on the IRD. In so doing, it responds to Paul McGarr’s argument that ‘an essential methodological leap in intelligence studies requires that material from the Global South is linked to that from the Europe [sic] and North America to provide a more holistic picture of the impact and perceptions of British (and American) intelligence operations outside the Anglosphere.’Footnote 4 Recent works on IRD operations in Egypt, Malaya, and Latin America have extended this scholarship outside of its traditional geographies. However, Simon Collier notes in this increasingly global corpus that ‘IRD work in Africa is almost wholly unexplored,’ a nadir he himself begins to address. Footnote 5 For this reason, the archival materials on the LAB series are both important and unique in the broader history of IRD operations in the Cold War Global South.

That the majority of the recently declassified IRD materials pertain to the Global South suggests that the department prioritized operations in the decolonizing world in the latter decades of its existence. This shift necessitated reorienting propaganda outside of a solely anti-communist framework and grappling with the rise of other ideological projects emerging across the Global South. While recent IRD scholarship has addressed the department’s engagement with Arab Nationalism, the LAB series reflects a growing preoccupation with the politics of Afro-Asianism, Pan-Africanism, and Non-Alignment that became increasingly salient in Cold War Africa. Thus, not only do materials like that on LAB allow historians to track the involvement of individual IRD officials over time, but also allow us to track continuity and change in department policy, textual output, and ideological priorities in different geographic and cultural contexts.

The LAB project sits at the intersection of contemporary histories of African print culture and engagements with the Cultural Cold War. LAB texts sought to infiltrate African print cultures that functioned as a nascent civil society for colonized subjects, and often ‘helped form a communal political and moral identity’ among African readers.Footnote 6 Recent work has emphasized the expansive geographies of these print cultures, connecting African readers and writers not only across the continent, but also in the diaspora.Footnote 7 The Cultural Cold War as a heuristic device has similarly been utilized to broaden the historical analysis of this global conflict in both ideological and geographic frames. Footnote 8 This expanded framework is particularly relevant for studies of Africa’s multiple Cold War engagements, the historiography of which tended to be confined to diplomatic history emphasizing proxy wars, trade, and aid. Recent work on the Cultural Cold War in Africa has focused on avant-garde literary journals aimed at a decolonizing intelligentsia and African writers’ engagements with Cold War themes through aesthetic and literary criticism.Footnote 9 Intellectual journals and literary critique were important textual fronts in the Cultural Cold War and this work has done much to uncover both the lengths that different blocs went to in order to secure influence among the literary elite and intelligentsia in the decolonizing world as well as the agency of African subjects in adapting, recycling, or rejecting such interventions.

However, openly propagandistic texts like LAB receive less attention, perhaps due to their overtly political nature, perceived inauthenticity, or, as Robert Young argues, because they ‘always preach only to the converted.’Footnote 10 This article in contrast takes the view that propaganda materials are important texts for studies of how the Cultural Cold War unfolded for readers in the decolonizing Global South. Propaganda is a particularly useful subject of study for the Cultural Cold War as it appears ‘in the gap between the official discourse of policy and regulations, the popular response to official discourse and its appropriation in literary and other cultural texts.’ Footnote 11 Due to this unique position, propaganda has a particular utility in bridging official and popular perceptions of print culture and politics. That LAB’s appropriation of Pan-African discourse was for an overtly political aim does not negate the fact that these texts were cultural products relying on intimate knowledge of African politics, nor that they were composed through a dialectic relationship with ‘real’ African print culture. LAB thus illustrates the utility of using propaganda as a lens to examine the Cultural Cold War in Africa, showing how propaganda, like intellectual and literary journals, were ‘also a bottom-up phenomenon, not one directed solely from above.’ Footnote 12

IRD and the communist threat to Africa

Launched in 1960, the LAB was ‘the product of a notional African organization, concerned to free Africa of all forms of foreign interference;’ the series would include thirty-seven leaflets by 1969 when the program was discontinued. Footnote 13 LAB is classified as ‘grey’ propaganda, in which ‘The information was often true, albeit selectively edited, but crucially the sponsor stayed hidden.’ Footnote 14 As was common IRD practice, the information used in LAB leaflets was sourced from publicly available news, government and intelligence sources, and reporting from IRD field officers on the ground in Africa.Footnote 15 This data would be scoured for ‘a pregnant theme to exploit and a topical African peg on which to hang it,’ which would then be drafted in the specific style and format of LAB leaflets.Footnote 16 The need for a locally resonant theme was informed by experience of IRD failures in other parts of the world, where inappropriate content led to a lack of reader engagement.Footnote 17 From 1949 the IRD had established Regional Information Offices (RIOs) in Singapore, Hong Kong, Caracas, Beirut, and Cairo tasked with the collection of locally sourced information for use in tailoring propaganda for target audiences in the regions they covered.Footnote 18 The department initiated a Field Officer program in 1961 to supplement the collection of local information in areas not covered by the RIOs. A number of the key propagandists involved in the LAB series had served as Field Officers in Africa and elsewhere, which is reflected in the intimate knowledge of African politics and preferences that underwrote the leaflets. The importance of information tailored for local audiences is suggested by the fact that leaflets were occasionally rejected if they did not focus on a topical event or issue concerning Africa.Footnote 19

With one exception, sub-Saharan Africa had been neglected by IRD prior to 1960.Footnote 20 This is not to say, however, that anti-communist propaganda work was absent in British Africa. The IRD sent regular publications on different aspects of communist activity to diplomatic posts and Information Officers around the world, including Africa.Footnote 21 From as early as the 1930s the London based Colonial Office (CO) adopted a ‘two pronged approach whereby imported publications were rigorously censored…and local editors were subjected to proimperial public relations materials.’Footnote 22 Colonial governments and missionary organizations were also actively involved in anti-communist propaganda directed at African audiences. A salient example is a 1950 booklet entitled Utawala wa Kristo au Utumwa wa Komyunismu (Reign of Christ or Communist Slavery).Footnote 23 A co-production of the Kenyan colonial government’s East African Literature Bureau and the Anglican Church, Utawala wa Kristo provided examples of Soviet oppression and the incompatibility of communism with Christian ethics for an African audience. An important sub-theme throughout the text is the argument that communists actively work to subvert the youth of target countries, promoting premarital sex, drug use, and other social taboos. This theme would have appalled not only a Christian audience, but also the many African proponents of conservative social reform popularizing their ideas throughout Africa in the mid-twentieth century. Information on the reception of the booklet is unknown, but Utawala wa Kristo is an important example of pre-IRD anti-communist outreach to African audiences not least because of the involvement of John Reiss, who would become one of the key architects of the LAB project a decade later. The booklet also serves as an important thematic comparison to later LAB leaflets, and provides examples of pre-IRD anti-communist discourse rooted in Christian ethics and conservative reformism.

Anxieties about the presence of communist propaganda in British Africa heightened during the 1950s and 1960s because of two interrelated processes. First was the perception that postwar Africa was increasingly connected to global networks of news and media. This increased connection was recognized even before IRD began its African operations, as noted by a British official in 1953: ‘None of Africa is now so “bush” that world affairs cannot affect it deeply at short notice.’ Footnote 24 The increasing coverage of world news framed in Cold War terms exacerbated the anxieties of British officials from the mid-1940s onward. Indeed, a CO official who had toured East and Central Africa in 1953 reported ‘A good many people told me that the intelligentsia who read newspapers had developed a considerable curiosity on the subject [communism].’ The same report notes that several clerks working for British colonial authorities in Kenya had recently shown an interest in learning more about communism, ‘and that this interest had simply developed because the word occurred so often in English newspapers.’ Footnote 25 Decolonization in many ways sparked an informational scramble for Africa, where independent African states ‘became the arena where the leading global news agencies…battled with alternative visions for news ranging from the Soviet model to cooperative visions spearheaded by UNSESCO.’Footnote 26 The withering of Britain’s ability to censor outside information was compounded by the agency of African governments to shape new national mediascapes.

Second, the postwar period saw a significant increase in communist efforts to proselytize to the Global South. The quantity of communist propaganda noticeably increased after 1957, when the ‘Central Committee of the Soviet Presidium approved an expansion in the volume and reach of propaganda aimed at the developing world,’ which in turn prompted other Communist states to follow suit. Footnote 27 The increase in circulation of communist propaganda to Global South audiences coincided with a significant phase of decolonization in British Africa. This heightened British anxieties about their former colonies’ engagements with Cold War politics outside the apparatus of censorship and control they had held as colonial rulers. IRD was particularly concerned about their abilities to circulate their own material in independent Africa to counter the upsurge in communist propaganda. Much of IRD’s material in Africa had been circulated by Field Officers directly to African and European contacts on the ground on conditions of anonymity of the source’s origin.Footnote 28 IRD officials worried that the nationalist inclination of a post-Independence African bureaucracy would make association with former colonialists politically risky, thus endangering a key means of propaganda distribution. Nairobi Field Officer Colin MacLaren summarizes IRD’s general anxieties about the situation in 1964, writing that in Kenya ‘it seems to me that as the process of Africanisation goes on, the distribution of IRD material will be found to be too circumscribed to meet the needs of the situation… The growing Russian, East European and (perhaps especially) Chinese propaganda will not be confronted at the point of impact.’Footnote 29

The logistics of Loyal African Brothers

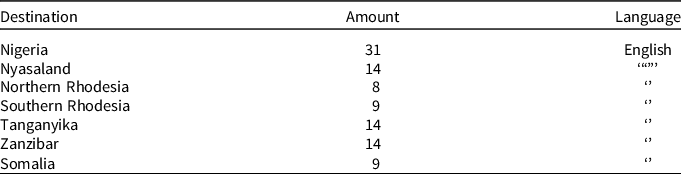

The LAB series was thus an attempt to sidestep such obstacles and ‘alert Africans to the dangers of communist penetration, through an acceptable medium.’Footnote 30 Composed in English, French, and occasionally Arabic, leaflets reached recipients across Africa through unsolicited mailings. Care was put into the leaflets’ physical appearance to make them seem authentic: ‘The leaflets were roneoed and somewhat scruffy’ and printed ‘on sheets of absorbent duplicating paper, of poorish quality, and the largest size most generally used locally.’Footnote 31 The distribution of LAB leaflets, with mailing from multiple cities, was meant to portray the FFAM as having a continental membership with ‘sources of information throughout Africa.’ Footnote 32 However, the sites from which LAB materials were mailed was in part dictated, or constrained, by other departments within the British foreign policy apparatus. Consistent in all the historical literature on IRD is a focus on the contentious nature of the relationships between the various departments within this apparatusFootnote 33 . The institutional constraints on IRD work applied directly to the LAB, as evidenced in a minute noting the IRD is required to obtain ‘political clearance’ from the Commonwealth Relations Office (CRO), Colonial Office (CO), and various security services prior to engaging in operations in African territories.Footnote 34 This was occasionally a source of frustration for LAB officials, as when key LAB official John Rayner complains that they are getting ‘shorter and shorter of posting points’ for the leaflets, with the implication that other departments are increasingly restricting options. Footnote 35 Friction between IRD and other departments extended to issues of content as well, with occasional references to leaflets being edited, delayed, or rejected due to pushback from other departments.

Leaflet recipients and languages varied depending on the topic of the leaflet with mailing sites similarly shifting based on the content of specific leaflets.Footnote 36 In general, recipients were involved in government, journalism, trade unionism, education, and religion, with the youth and student wings of African political parties well represented. This target audience is commensurate with general IRD practice in this period of its institutional life. In its early years, the preferred audience of IRD propaganda was primarily ‘the broad masses of workers and peasants in Europe and the Middle East.’ Footnote 37 However, by 1955 IRD publications were increasingly directed at ‘the small number of people in every country who influence and form public opinion.’ Footnote 38 The LAB series was slightly different, in that it self-consciously targeted not simply those in power or with influence, but more specifically the rising generation of post-independence figures of influence. This was a coveted audience for propagandists on all sides of the Cold War who sought the ‘allegiance of the next generation of African leaders.’Footnote 39 Indeed, discussing recipients of IRD propaganda in Uganda John Reiss writes that ‘All have been chosen because of their capacity and opportunity to influence the thinking of up and coming Ugandans,’ a dynamic that was not unique to this country.Footnote 40

The heavy representation of journalists and newspaper editors on recipient lists indicates the desire for LAB materials to be exposed to African audiences through media as well as direct mailings. This is concomitant with longstanding IRD practice, which from its founding sought to cultivate relationships with journalists and other media figures. Standard practice was for IRD officials to pass material directly to trusted contacts in the media of various target countries. This process reflects the character of media relationships in the era of decolonization, in which Cold War powers and private news organizations vied with each other and with new national governments to corner the market in newly independent states.Footnote 41 IRD official John McQuiggan comments on the omnivorous nature of information reproduction in Uganda stating that the media ‘is receptive to any material of topical interest that comes from any source. They cannot afford to subscribe to Reuters or any other news agency service and, therefore rely for their international news coverage…on what is provided by TASS, Novosti, B.I.S., U.S.I.S., and the Ugandan Ministry of Information.’Footnote 42 This dynamic was not unique to Uganda, as noted by James Brennan in his study of the Tanganyika Opinion, an Indian-run newspaper that ‘As late as 1955…ran anti-NATO publicity from the Indian consulate right alongside pro-American publicity from the United States Information Service.’ Footnote 43 This latter example illustrates not only the eclectic nature of news reproduction in Africa in the 1960s, but also the necessity of countering propaganda of Cold War actors outside an East/West binary.

LAB materials did infiltrate African and international media on at least two occasions. A report on the project states that a LAB leaflet criticizing the Soviet Union for not more actively supporting Egypt in the Six Days War, was quoted in East African Standard in an August 1, 1967 issue.Footnote 44 As the leading English language paper in Kenya, the East African Standard would have reached the influential audience the IRD was hoping to sway, as well as a means of imparting a stamp of legitimacy on LAB as a credible source of information. In a similar vein, a 1969 BBC ‘From Our Own Correspondent’ piece states that after a police raid on the office of a radical newspaper in Lagos, ‘ready-made page proofs were found in the building designed and supplied for use free by the Russian Information and Cultural Organisation, which is being spread in Nigeria at a time when British expenditure in this direction is being cut back.’Footnote 45 This information was sourced directly from an LAB leaflet, from which the BBC story ‘usefully repeats important points.’Footnote 46

There is an ironic element to the intertextuality of this latter episode, where British clandestine propaganda is used a source in reporting on Soviet clandestine propaganda by a legitimate news source. This inauthentic intertextuality is seen again in a leaflet criticizing the attitude of the communist-aligned World Federation of Democratic Youth (WFDY) over racism faced by African students studying in Sofia. A secret minute of 1964 notes that ‘The leaflet reprinted the text of an offending W.F.D.Y. letter published in the Zanzibar daily Zanews. (The W.F.D.Y. letter in question was also one of our productions).’Footnote 47 The intertextuality of this leaflet highlights the importance of forgeries as tools in the repertoire of propagandists on all sides of the Cold War in Africa. Forged documents purported to emanate from the CIA were indispensable for Soviet propaganda schemes in Africa, and other communist powers similarly relied on this tool.Footnote 48 The many international conferences occurring in Africa in the 1960s were key venues for the circulation of forgeries, as in the 1961 ILO Conference in Lagos where the Ghanaian delegation circulated a forged British Cabinet paper to other African delegations.Footnote 49 In this case, the forgery was ‘produced in one of the Iron Curtain countries’ but served Ghanaian interests in that it attacked western-aligned Kenyan politician Tom Mboya and the proposed East African Federation to which Ghana was strongly opposed. The overlap between Ghanaian and communist interests in Africa was a perennial concern of IRD officials, and it is episodes like this that perhaps inspired the LAB’s continual focus on the theme of Ghanaian subversion, which will be discussed below. It is also noteworthy that these examples show how the borders between black and grey propaganda were more porous than this categorization implies.

There is no mention of any leaflets being composed in vernacular African languages throughout the LAB’s existence, a factor that could have been a serious impediment to the exposure of these materials to African audiences. However, IRD propagandists likely assumed that their material, including LAB leaflets, would be translated into vernacular by recipients themselves. John McQuiggan indicates that the Ugandan vernacular press translates information received from outside sources in their reproductions for a domestic audience as a matter of course, and a plethora of secondary literature on African print culture in the twentieth century indicate that Uganda was not unique in this respect.Footnote 50 A possible example of propaganda material entering the vernacular media in this way is seen in a 1965 article in Sauti ya Mwafrika, (SYM) the newspaper of Kenya’s ruling KANU Party. The article concerns a letter issued by an organization called the East African People’s Front accusing Oginga Odinga, Ochieng Oneko, and Bildad Kaggia of receiving the support of communist countries and casting doubt on their nationalist bona fides. Footnote 51 While the letter in question is not identifiably an IRD production, there are clues pointing to British involvement, or at least knowledge, of the provenance of the letter. In a 1969 correspondence, an anonymous source writes to John Rayner regarding a potential successor organization and propaganda text series to the FFAM/LAB. In discussing possible ideological orientations for the successor group, the respondent suggests a ‘Maoist body to the left of the Russians castigating them for revisionism and frightening everyone with its extreme proposals, e.g., the erstwhile Peoples’ Front of East Africa.’Footnote 52 The correspondence does not make clear whether this organization was a previous fiction created by outside sources or a legitimate African Maoist organization. Regardless of the letter’s true provenance, that it was reproduced in Swahili in SYM indicates that Cold War propaganda was reproduced in African vernacular media. Now that LAB documents are becoming increasingly available to researchers, it may be possible to comb through vernacular sources to identify more systematic inclusion of the project’s texts in this mediascape.

We have seen examples of how LAB materials were distributed and touched briefly on their target audience. But who was crafting these materials? Unfortunately, the archival records available to date do not provide much evidence on who was writing the LAB leaflets, aside from a brief reference to one Mr. Webber who ‘is reading African papers and gradually learning the language’ so that he can better compose LAB materials.Footnote 53 IRD propaganda projects in Europe relied on local agents to not only provide information for propaganda, but also to compose propaganda materials. This practice was similarly used in IRD operations in the Global South, including Egypt and Malaysia, where the department similarly made use of local writers and broadcasters to compose their materials. Indeed, in the latter case IRD recruited local staff to draft propaganda ‘partly on the grounds that expatriates could not hope to fathom the inscrutable workings of the oriental mind.’Footnote 54 It is unclear whether this occurred in the LAB series, but it is likely that the leaflets were crafted solely by IRD officials. As noted above, there was a sense that African contacts could not be trusted to receive materials for distribution directly from IRD sources in the post-independence context. Given the sensitive and clandestine nature of the LAB project, it seems unlikely that IRD would risk exposure by hiring African writers. Comments on the nature of African reading habits by IRD officials imply that African writers would also be unnecessary as it becomes clear that these propagandists believed that, unlike their counterparts in Asia, the minds of their target audience were not complex enough to warrant extra attention.

What is clear is that a select handful of IRD officials were involved in implementing the project and editing leaflet content. Key among them was John Rayner, who worked on the LAB project for its entire run. Rayner’s employment history is characteristic of IRD officials in that it spanned journalistic and clandestine propaganda work. Prior to World War II, Rayner was an editor at the Daily Express and worked in propaganda and intelligence during the war.Footnote 55 After the war he became the Head of RIO Singapore before moving to work for IRD in London, becoming the head of the Special Editorial Unit. Colin MacLaren was the Head of IRD’s Africa Section during the early rollout of the LAB series from 1961-1964, when he became the IRD Field Officer based in Nairobi, with a brief covering Tanzania as well. He had previously served as the Director of Information Services and as UK Information Officer in Nigeria; in this latter position he was involved in the process of decolonization and handover to Nigerian personnel following independence in 1960. Similarly, John Reiss had a depth of experience working in Africa during and prior to his involvement in LAB. Reiss served as Head of the Africa Section of the Kenyan colonial government’s Information Department from 1945, being promoted to Director in 1954 where he was responsible for establishing much of the colony’s radio infrastructure for the Kenya Broadcasting Service. He would then serve as Director of Information Services in South Africa and New Zealand, before being recruited to work for IRD in 1966.Footnote 56 The depth of experience in journalism and propaganda held by these officials formed the foundation of the LAB series.

Reception and effects of LAB leaflets are difficult to gauge with certainty. This is not unique to the LAB project but rather is one that haunts work on clandestine propaganda projects. Indeed, Andrew Defty notes ‘It is notoriously difficult to assess the impact of propaganda, particularly if it is directed at a foreign audience. One may identify propaganda policies, and assess the output of propaganda agencies, but it is very difficult to gauge how the propaganda is received.’ Footnote 57 It is thus necessary to rely on references made by LAB propagandists themselves as to the effects of their materials. IRD official D.M. Biggin provides perhaps the clearest statement of LAB’s circulation base in a letter on a 1969 trip to Nigeria where he writes ‘It was confirmed during my recent visit to Lagos that the LAB leaflet had had an impact both in official and press circles there. I was told that it had circulated widely among journalists in Lagos, and it was known in the High commission that the leaflet had been examined by the agencies of the Federal Military Government, including Special Branch.’Footnote 58 Wide circulation does not necessarily translate into action, however. IRD speculated two years earlier that a leaflet accusing Tanzanian politician Oscar Kambona of undermining President Julius Nyerere’s economic transformation of the country led to the former’s resignation from government.Footnote 59 Earlier, a secret report indicates that IRD believed a 1962 LAB leaflet accusing the Soviet Ambassador to Leopoldville of espionage work led to that ambassador, Sergei Nemtchina, being officially reprimanded by the Congolese government for interference in local politics. Footnote 60 While IRD officials cite these episodes as proof of efficacy, we must be cautious in taking these at face value. As Susan Carruthers notes, IRD was ‘Ever keen to promote its own business’ in the face of hostility from other departments, budget cuts, and even contradictory facts.Footnote 61 The claims above must therefore be taken with a degree of skepticism until such time as more detailed records on reception are made available to researchers.

Generic Pan-Africanism: discourse and authorship in Loyal African Brothers

While we do not know the effects of LAB materials, I argue that they nonetheless serve as important windows into the psychology of British propagandists during the Cold War. To analyze this propaganda psychology, it is instructive to analyze the discourse of the series’ notional authors: the Freedom for Africa Movement. The fictional backstory of this organization and the form of the leaflets themselves reflect a deep knowledge of African political debates and print cultures on the part of IRD propagandists. However, the leaflets exhibit a paradoxical characteristic of being simultaneously specific and generic, displaying the granular detail of an intelligence report yet articulated in a political vocabulary devoid of ideological commitment or nuance. Correspondence between involved officials show that they were aware of the ideological disagreements between specific brands of Pan-Africanism and African nationalism then occurring in the continent, yet the LAB series is marked by generic appeals to a primordial and contentless ‘Africanness.’ I argue that this character was the result of an all-Africa approach to the series, which was refracted through the biases held by IRD propagandists themselves. On the one hand, the generic Pan-Africanism of the LAB could be interpreted as a means of reaching as broad an audience as possible without being constrained by a particular ideological commitment. On the other hand, when read in tandem with evaluations of African readers intellectual capacity it becomes clear that IRD propagandists believed that this audience would be unbothered by the lack of ideological nuance. As one propagandist noted, ‘The popular appeal of these letters is largely based on their semi-educated prose’ and ad hominem attacks that occasionally descended into salacious rumormongering.Footnote 62 ‘Semi-educated’ is used to describe African readers multiple times in IRD correspondence, and one official notes that LAB vocabulary was chosen to be ‘attractive to the half baked intelligentsia because it is part of the hideous jargon which Marxist polemics have made fashionable.’Footnote 63

This statement is significant in that it confirms LAB materials were crafted in conversation not only with African print culture, but also with the globally circulating vocabulary of anti-colonialism. It also indicates that IRD had learned from previous failures, particularly in the Middle East where department propagandists failed to accurately gauge the political priorities of Arab readers.Footnote 64 Paul McGarr shows how IRD incorporated lessons of previous failures in India, replacing the ‘relatively long-winded and abstruse IRD copy’ of previous materials and with content modeled on communist propaganda which were ‘written in plain language…focusing on basic themes calculated to attract the attention of rural readers.’ Footnote 65 In the context of LAB, it was the bombastic tone and superficial politics that characterized the leaflets that were thought to make them appealing to a middlebrow African audience. In this the leaflets resemble, in both form and function, the political memes populating contemporary social media. Both text forms ‘build strength through repetition and recognition, and…call attention to themselves through techniques of likeness, indication, guideposting, exclamation, attention-forcing, thrown-togetherness.’Footnote 66 These are not the kinds of texts that form the platform of substantive debate or intellectual discussions, but rather fodder for the politics of point scoring and leveraging of position that characterizes much of contemporary political debate. That this style and content was thought to be appealing to the future leaders and opinion-shapers of independent Africa shows that IRD propagandists in the 1960s held many of the same racial biases and ideas of African intellectual capacity that underwrote centuries of colonial rule. Indeed, in other parts of the world Cold War powers actively sought to cultivate intellectuals with propaganda as they ‘assumed that intellectuals would play important toles in influencing public opinion and form the vanguard of social change.’Footnote 67 That LAB appears to have eschewed addressing African intellectuals could indicate that the department did not believe that there were intellectuals worth cultivating, or that African societies were undeveloped such that intellectuals would not play as influential a role as they would in other decolonizing societies.

These aspects of the project become clearer when analyzing the discourse that populated LAB texts, as well as their style and physical appearance and the fictional backstory of the FFAM. IRD propagandists never directly provided a profile of the FFAM for readers. The leaflets were never signed by any individuals, and the nominal authors never stated directly where they were based. However, the style, syntax, content, and form of the leaflets were meant to provide clues for readers to come to directed conclusions about the organization’s details. The ambiguity surrounding the FFAM was not unique to the LAB series; rather, IRD tapped into a longer history of pseudonymous authorship in twentieth-century African print culture.Footnote 68 In her analysis of this phenomenon in West Africa, Stephanie Newell argues that pseudonyms are not merely means of disguising authors’ identities, they also convey information about the authors’ positions in and of themselves. Newell’s analysis bears directly on the FFAM, particularly her argument that pseudonyms ‘reveal the ways in which correspondents selected identities that revealed their cultural and racial affiliations and political interests, as well as a powerful sense of their place in the world.’Footnote 69 The clues provided by the name chosen for the notional authors of the LAB series as well as the particularities of the leaflets’ language attempted to establish the FFAM’s place in the world both geographically and ideologically.

IRD officials meant for African readers to conclude that the FFAM was ‘by implication based in one of the francophone countries.’Footnote 70 Readers were meant to come to this conclusion primarily through the format of the leaflets themselves, specifically the spelling and syntax. The English versions of LAB leaflets were riddled with spelling mistakes made to appear as if they had been written by a native French-speaker. The rationale for this tactic was that the francophone spellings ‘dissociates them from the U.K.’Footnote 71 There is no mention of how recipients responded to this stylistic camouflage, so it is impossible to know if African readers were as fixated on or convinced by the consistency of francophone misspellings as were IRD officials.

The IRD was less regionally specific when it came to the FFAM’s ideological background. The FFAM’s ideological position can best be described as generic Pan-Africanism. The FFAM’s politics were Pan-African in that they constantly referenced the inherent unity of Africans across the continent regardless of any metric of internal division. The leaflets are littered with references to ‘our african traditions,’ ‘our african way of life,’ and ‘the african consciousness’ and how these are incompatible with communist ideology and designs for Africa.Footnote 72 These politics were generic in that the leaflets never actually elaborate what these aspects of African consciousness or society were, or what their vision for African politics entailed. The leaflets occasionally provided frames of reference for what their Africanism could stand for, as example being a leaflet expressing support for Nigeria’s federal government in their offensive against the breakaway state of Biafra: ‘Our Continent of Africa cannot sustain tribalist secessions.’Footnote 73 The leaflets similarly reflect the FFAM’s antipathy to nuclear testing and support for global disarmament, though IRD propagandists admit that this position had less to do with African political currents and was ‘intended to annoy the Russians.’Footnote 74

The closest the leaflets ever get to articulating a specific ideological position is through support for African Socialism and neutralism. Discussions about the nature and shape of African Socialism was a regular feature of political debate in this period when ‘many African leaders made significant attempts to “localise” socialist ideas’ and, thus, this is another example of the LAB’s discursive mimicry.Footnote 75 Again, however, the African Socialism in LAB leaflets is never defined with any specificity and is primarily deployed as a foil for attacking the scientific socialism of communist states. Generic appeals to undefined African Socialism belied the diversity of this ideological category, debates on which appeared in middlebrow African press as much as in the speeches of individual leaders and the intellectual journals of the African intelligentsia in the 1960s. Competing streams of African Socialist thought developed along nationalist lines in the 1960s, with Tanzania’s Ujamaa, Uganda’s Move to the Left, and Ghana’s Afro-Marxism being prominent examples. On the one hand, then, LAB’s African Socialism could not afford to be specific lest they ‘tarnish the organisation with the political brush of that country.’Footnote 76 On the other hand, however, the diversity and idiosyncrasy of competing streams of African Socialist thought could have undermined the appeal of the LAB’s generic interventions in these debates.

Promotion of neutralism and non-alignment was perhaps the most clearly articulated political position held by the FFAM and was an attempt by the IRD to ‘co-opt the literary cold war geography of Afro-Asia.’Footnote 77 Examples drawn from several leaflets associate between African nationalism with neutralism in such a way as to make them seem inherently related. Most directly, a leaflet attacking Zanzibari communists, concludes ‘The interference of the great powers in any form will only drag us into their cold war and destroy our ideal of a united and non-aligned Africa, which is of a primordial importance for us if we are to carry out our common task of developing our countries.’Footnote 78 Not only is neutralism presented here as a danger to the development priorities that lay at the heart of African nation-building agendas in the postcolonial era, but it is also positioned as a threat to the sense of a common Africanness that stood at the core of the FFAM’s ideological platform.

The positive view of neutralism contrasts with how this political position appeared in IRD propaganda in other parts of the world. Rory Cormac, for example, notes that British feared the election of a leftist government in Iceland in the mid-1950s would provide an opening for the Soviets to ‘detach Iceland from NATO and spread neutralism across the region.’Footnote 79 Anxieties over neutralism and non-alignment similarly haunted IRD propaganda work in Egypt, where the ‘fear was that Soviet propaganda might succeed in disrupting the Western position in the Middle East thus ensuring the area’s neutrality in any future conflict.’Footnote 80 A core focus of British anti-communist propaganda in the Middle East in the 1950s was thus discrediting neutralism and tying it explicitly to communist threats to the region’s independence and stability. That neutralism and non-alignment were actively supported in the LAB series is thus a significant departure from earlier IRD propaganda projects, which in turn reflects the evolution of both the ideological valence of non-aligned politics and the different strategic value and priorities attached to Africa.

The FFAM was built around generic Pan-Africanism to provide a sense of authenticity as well as to exploit communication divisions between Anglophone and Francophone African nationalists that undermined the Pan-African project in the 1960s. However, the same divisions that deflected suspicion away from British sources potentially created an obstacle to LAB’s reception among certain audiences. For example, IRD official D.M. Biggin writes ‘I must admit that I find it hard to reconcile the evident francophone origins of the paper on the one hand with the intimate knowledge of an Anglophone territory on the other. One must assume that what are evidently francophone-African authors have no anglophone-African brothers who assist them in their draftsmanship.’Footnote 81 Biggin’s assumption speaks to contemporary tensions within African politics on the continent and in the diaspora. The borders created by colonialism were as much linguistic as they were geographic, and cooperation across linguistic barriers was not a given among African nationalists. The kind of bilingual African nationalist readership addressed by LAB was thus more a creation of British propagandists than an accurate reflection of the realities of African political relationships.

Conversations between IRD propagandists reveal how they attempted to circumvent these political tensions to maintain the broadest base of LAB readership. Echoing the point raised by Biggin, Hans Welser states he has no objections to the FFAM being coded as francophone per se, but wonders ‘whether East Africans, who are the main target [of this leaflet], pay much attention to the views of their French-speaking brothers.’Footnote 82 Responding to these concerns, J.B. Ure concedes that ‘in general…East Africans are not greatly impressed by the views of French-speaking West Africans,’ however an exception is often made for Guineans. Ure argues that Guineans are seen as ‘experts on African independence’ by African nationalists in general and are especially well regarded in Tanganyika due to Guinean leader Sekou Toure’s recent overtures to Julius Nyerere. He concludes that ‘if these letters were posted from Guinea there would be no harm done by their apparently francophone origin.’Footnote 83 Whether Ure was right in this argument is of less importance than the fact that the discussion indicates that there were serious political disagreements in Africa that could have potentially undermined the LAB’s generic Pan-Africanist appeal. That IRD propagandists do not seem to have developed a systematic solution to this issue indicates that they hoped to paper over such disagreements through a generic appeal to supposedly universal African cultural referents and bombastic style of argumentation.

By 1969 the IRD began to realize that the FFAM needed updating. In a discussion between involved officials, the prospect of a successor to the LAB series was debated. Proposals included a radical New Left student group, a Maoist body, and a Black Power movement. The Maoist option was seen as being too limited in lines of attack, while for Black Power groups on the continent and in the diaspora ‘our impression is that the Africans are not receptive to their ideas’.Footnote 84 The consensus appeared to land on the successor being a militant student group of ‘African students behind the Iron Curtain by implication in East Germany, with possibly some adherents in the USSR.’Footnote 85 John Rayner writes of his approval for this move and, on naming, states ‘we had already been attracted by the slogan value of the word “power” and called our student organisation “The Organisation of African Students for African Power.”’Footnote 86 While there was continuity in the form of providing a fictional identity through implication and having a Pan-African membership, the specificities of the successor organization’s ideological and geographic position indicates that IRD had recognized that generic Pan-Africanism was no longer a viable propaganda lexicon.

Africanizing the Cold War: Ghanaian subversion and anti-Arabism

The thematic content of the LAB series shows both overlap and divergence with IRD practice and earlier anti-communist propaganda in Africa. LAB shared with other IRD propaganda elsewhere in the Global South the making of distinctions between ‘real’ nationalists and those acting under communist pretenses.Footnote 87 Earlier anti-communist propaganda in Africa critiqued communism from a Christian perspective, and these materials also reflected earlier IRD stock content that publicized repression under communist regimes. Such arguments may have swayed Christian Africans and those literate elites engaged in the debates on moral reform and socially conservative moralizing that characterized much African political print culture in the twentieth-century.Footnote 88 However, it would be difficult for even this audience to read examples of Soviet suppression of the Church, free press, and individual freedom and not see echoes of the same under British colonial rule. This is particularly true during and after the Mau Emergency in Kenya when the colonial government’s draconian methods of quelling the insurgency brought mass incarceration, suppression of Kikuyu independent schools and churches, and widespread censorship of African media. By the late 1950s, associations with the inequities and repression of colonial rule inherently undermined the receptivity of positive British propaganda aimed at African readers.

As unattributable propaganda from a nominally African source, the LAB series was not constrained by the obstacles facing more public, attributable British anti-communist work. The freedom to maneuver is reflected in the themes that characterized many of the leaflets in the series. A close reading of two LAB leaflets illustrates themes that were developed within the series for a specifically African readership. The first of these themes is Ghanaian subversion. While criticisms of Ghana’s subversive role across Africa was referenced in several leaflets, this section focuses primarily on a leaflet attacking the Ghanaian periodical The Spark to expand upon the broader theme of Ghanaian subversion and highlight the intertextuality of the LAB series and Cold War propaganda more generally. The leaflet on The Spark is also significant in that it reflects the care with which IRD criticized individual African leaders. Indeed, the leaflet attacking The Spark was released when it was because materials attacking Nkrumah directly had not yet been cleared for use. The Spark, though a ‘more superficial aspect of Ghanaian subversion,’ was oblique enough of a target that it was ‘enough for a first shot’ in what would become a longer-running campaign targeting Ghana’s subversive role.Footnote 89

The leaflet displays the generic Pan-Africanist criticism of the paper which ‘calls itself a socialist weekly organe [sic] of African Revolution, but whose contents are in no way in accordance with true African aims and ideals.’Footnote 90 It goes on to associate The Spark with communist interests through the figure of Batsa Kofi, the paper’s editor who is described as the Secretary-General of the Pan-African Union of Journalists but also a ‘well-known communist and closely allied to the Chinese.’Footnote 91 The identification of Kofi’s position, from which he is ‘admirably well placed to impose his deformed point of view, his thirst for power and lust for violence throughout all our continent,’ recycles a recurrent focus of LAB leaflets in exposing communist subversion of Pan-African institutions.Footnote 92 The leaflet also highlights the intertextual nature of Cold War propaganda in Africa through its association between The Spark and Chinese communists, ‘fiery extracts from whose publications it has published in serial form.’Footnote 93 When read against leaflets criticizing Nkrumah for his ties to the Soviets, the association of Kofi with Chinese interests could have been meant to subtly foreground the consequences of involvement in the Sino-Soviet competition for influence in postcolonial Africa, an argument that occurred not infrequently in later leaflets.

The intent of leaflets attacking Ghanaian subversion was to undermine the appeal of Ghanaian propaganda to a wider African audience. Indeed, it was in terms of audience that Ghana’s propaganda apparatus was perhaps most threatening to the aims of the IRD. Summarizing the danger of Ghanaian propaganda, the British High Commissioner in Uganda writes ‘Nkrumah is not interested in carrying with him Houphouet-Boigny in his gold and malachite palace, nor the Mwami of Burundi in his night club. His appeal is to the fierce young secondary school leaver out of a job, the Youth Winger or the struggling trade unionist.’Footnote 94 This was precisely the audience to which LAB was addressed, putting Ghanaian propaganda in direct competition with the IRD. Reports reveal a particular concern over the effect that Ghanaian propaganda might have in East Africa, where ‘the Ghanaian missions…have done much to etch his [Nkrumah’s] image on the minds of trade unionists…and journalists.’Footnote 95 British officials had noted with alarm Ghanaian influence in Ugandan media, with the editor of the government daily newspaper being described as ‘Nkrumah indoctrinated’ and Radio Uganda having a ‘Ghanaian and Moscow influenced staff.’Footnote 96 Ghanaian penetration went beyond mere influence, with the country’s representatives in Uganda actively distributing propaganda and cultivating contacts in political and media circles. A prominent example of this is the case of Paul Muwanga, a ruling party member of parliament who founded the African Pilot periodical with funding from Ghana’s High Commissioner David Busumtwi-Sam. Published in English and Luganda, the Pilot was nominally a product of the ruling Ugandan Peoples Congress but, due to content limited to praise for Ghana and invective against Britain, was seen as a vehicle for Ghanaian interests in the country. Muwanga was also the Uganda distribution agent for The Spark, thus serving as both a direct and indirect distributor of Ghanaian propaganda.Footnote 97

IRD was concerned with the extent of Ghanaian propaganda as it was proving to be effective among some African audiences. Not only was Nkrumah revered by a broad swathe of African nationalist activists, but also his ideas found fertile soil in the minds of some African leaders. Ugandan president Milton Obote, for example, stated he had been convinced by Nkrumah’s arguments on continental unity and had expressed a ‘degree of belief in the argument that the East African Federation is an Anglo-American plot, which is a Ghanaian propaganda line.’Footnote 98 Ghanaian agents flooded East Africa with propaganda targeting the Federation, which was anathema to Nkrumah’s vision of a continental United States of AfricaFootnote 99 However, IRD propagandists had to tread lightly in undermining Ghanaian propaganda because of Nkrumah’s stature in African nationalist circles. In The Spark leaflet, Nkrumah himself only comes in for criticism at an oblique angle of disappointment that such a visionary of African unity ‘should permit the diffusion of a newspaper whose purpose, according to its contents, is to destroy the very essentials of that same unity.’Footnote 100 This critique implies that Nkrumah may be unaware of The Spark’s content, or even that he is being misled by members of his inner circle. Betrayal and undermining of African visionary leaders by unscrupulous confidantes – all inevitably shown to be communist stooges – is a recurring theme in the LAB series, with Nkrumah and Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba being used as object lessons throughout the series’ run. The reader was thus urged to consider that the failures of leaders like Nkrumah and Lumumba were not failures of African nationalism, but rather of sincere, though flawed, nationalists who were manipulated by unscrupulous communists.

The second theme developed for a specifically African audience is anti-Arabism, often articulated as opposition to Arab imperialism. Recycling stock themes of the series, leaflets accused ‘Arab progressive parties’ in Africa of working to undermine African Socialism, seeking to dominate Pan-African organizations, and draw African into the ‘Arab Cold War.’Footnote 101 Racism and histories of slavery were also foundations of the LAB’s anti-Arabism, to the extent that a leaflet claims, erroneously, that the in Arabic the word for ‘slave’ is used as a synonym for ‘African’.Footnote 102 More generally, LAB leaflets articulated a general opposition to Arab imperialism in much the same way as they accused communist powers of imperial ambitions. Arab imperialism was a theme that, while not universally relatable, could apply to several different African contexts. However, a leaflet attacking radical socialists in the Zanzibari revolutionary government dredged specific local histories to articulate a position equating communism with ‘Arabism’ and a return to the era of slavery.

The leaflet attacks the radical socialists among the leadership of the 1964 Zanzibar Revolution which overthrew the Sultan of Zanzibar and the ruling Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP), installing a government composed of African nationalist Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP) and the Umma Party, a radical ZNP splinter group. The leaflet attacks Abdullah Kassim Hanga and Abdurrahman Mohamed Babu, the post-Revolution Prime Minister and Minister of Defense and External Affairs respectively. The crux of this leaflet is the accusation that Hanga, Babu, and their comrades are cynically using communist resources to re-assert Arab dominance of black Africans. As discussed, establishing the inherent opposition between Africanism and Communism in the minds of African readers was a central element of the LAB series. But in this leaflet, we see what had elsewhere been a vague and homogenizing Africanist cultural politics adopt a direct racial rubric of inclusion/exclusion: ‘the Afro-Shirazi party is an African nationalist party. Why is it getting muddled up with Arabs like Babu and Hanga? As is well know [sic] these two are Communist agents.’ Footnote 103 This line most directly sets up the opposition of African/nationalist and Arab/communist for the reader, implying that it was impossible to claim racial and ideological identities outside of this duology. The leaflet also reiterates the theme of communist betrayal consistent in LAB leaflets, arguing ‘The revolutionaries have helped the Africans to power, but instead of succeeding in the permanent Africanisation of Zanzibar, we now find that the Communist Arabs today are as much in power as the Sultan and his gang were before.’ Footnote 104 The legacy of slavery and racial exploitation was a central theme of contemporary Zanzibari print culture and politics, which was particularly contentious in the 1950s and 1960s as African nationalism challenged the ZNP’s articulation of a Zanzibari nationalism rooted in cosmopolitan Afro-Asianism.Footnote 105 Thus, warnings of a communist future coded as simultaneously a betrayal of African nationalism and a return to the Arab domination and slavery likely found fertile soil in the minds of Zanzibari readers.

This leaflet departs from standard IRD propaganda practice that in general ‘sought to raise doubts about individuals rather than whole groups.’Footnote 106 The association of Arabs with communism through the theme of betrayal could easily reignite the racial tensions that undergirded the revolution, which included mass killings and displacement of the islands’ Arab and Indian populations. That Zanzibar had previously been a receptive site for Nasserist propaganda in the 1950s and early 1960s, and the fact that the revolutionary government had invited aid and advisors from across the communist world, perhaps instilled a sense of urgency in IRD propagandists that outweighed the risks of instigating further pogroms. Indeed, there is a plaintive air to a line in the leaflet persuading readers that ‘The british and americans [sic] will not interfere against a genuinely nationalist movement but they will interfere if they think that Zanzibar is going to become a Communist state.’Footnote 107 Here too is an example of longstanding IRD practice of making distinctions between ‘real’ nationalists and communists in their propaganda output.

The leaflet argues that ‘real’ African patriots must support Abeid Karume, the leader of the ASP and a proponent of a more racially exclusive form of African nationalism. It is not just Karume’s ideological orientation that is presented as desirable, but also his racial bona fides: ‘M. Abeid Amane Karume, president of the new Republic of Zanzibar is africain [sic] from the continent, of congolese [sic] origin,’ and, thus, is ‘loyal to african [sic] aspirations.’ Footnote 108 Not only does this presentation reiterate the universal and primordial character of Africanness that the series constantly affirmed, but it also advocates for a hardening of racial and cultural boundaries in an area that has historically been associated with cosmopolitan intermixing.Footnote 109 Here again the leaflet mirrors arguments about the connection between autochthony and the right to make political claims then occurring on the Swahili Coast, in which ideas of race, geography, and culture were marshaled in support of or opposition to competing political visions, arguments that became increasingly fraught in the periods immediately before and after independence. Footnote 110 The racial and geographic backgrounds of Karume, Babu, and Hanga presented by the LAB leaflet were, however, factually inaccurate, as all three could make legitimate claims to ‘Africanness’ in their respective family backgrounds. However, accuracy was not of primary importance for LAB authors. Rather, the emphasis was on sidelining the radical socialists from political leadership and, in so doing, undermining the appeal of communism and the solidarities of Afro-Asianism that could have facilitated a communist bastion on the Swahili Coast.

Conclusion

A close reading of LAB leaflets provides insight into the competing political discourses circulating throughout Africa and indeed the decolonizing Global South more broadly. Adopting the discourse of generic Pan-Africanism to frame anti-Communist arguments shows that LAB authors were not political innovators and leaflet content did not emerge in a vacuum. Rather, they reflected debates occurring in the heady days leading up to and immediately after independence in which African subjects ‘gave considerable attention to the vexed question of how to project a unique African personality and identity in a world in which the West’s neocolonial influence appeared virtually unassailable.’Footnote 111 By mimicking these debates IRD propagandists used the LAB series to argue that the neocolonial danger lay not only to the West, but also to the East. The series thus grafts Cold War specificities onto conversations that had long been staples of African politics and print culture, ‘in which questions about political relationships were part of a wider set of questions about what kind of society could and should be built.’Footnote 112 However, the LAB’s appeal to generic Pan-African sensibilities belied the complexity and competitiveness of different streams of discourse and divisions within African politics, potentially undermining the series’ appeal to African audiences.

The LAB project was discontinued in 1969, likely due to a combination of budget cuts and ‘partly because it had led to a proliferation of similar type leaflets attacking contrary targets which saturated the market…and because there were beginning to be doubts expressed about the authors’ identity.’Footnote 113 In a way, perhaps, imitation of the LAB model speaks to a certain kind of success for the project. More concretely, however, it is difficult to determine how effective LAB leaflets were on the ground due to the nature of the files that have been released and what they do and don’t tell us about how the LAB unfolded. Most of the declassified files pertain to the topics and vocabulary of LAB texts. This data provides an insight into the psychology of British anti-communism in Africa, insights that can perhaps be analogized to other parts of the Global South. An official in the UK Information Office writes in 1961 that for propaganda projects to succeed ‘they must be devised to fit the social and psychological, as well as political, frame within which they take place.’Footnote 114 I argue that the LAB files tell us more about the psychology and priorities of IRD propagandists than they do about African readers. Correspondence around the project reveals that IRD propagandists held paternalistic views of African politics and culture that in turn influenced the form and substance of LAB texts. Similarly, LAB texts reflect anxieties about Cold War geopolitics that may not have been of direct concern to recipients. However, I argue LAB texts were perhaps more useful as ammunition in domestic political feuds. This argument is necessarily speculative, but it aligns with recent scholarship on how African politicians manipulated Cold War relationships to achieve goals more directly salient to politics in a national framework.Footnote 115 Whether LAB texts were in fact used in this manner, and whether this usage was purposeful on the part of IRD or due to the agency of recipients, is a question that must be pursued in further research on the series.

In other words, these files do not tell us how LAB texts may have shaped African political debates on the ground, nor the details of how they were meant to be disseminated to a wide audience. The files contain many recipient lists and descriptions of mailing logistics. However, there is no information on what, if anything, recipients did with the materials or indeed what IRD propagandists expected them to do. Were they distributed or otherwise communicated to colleagues, students, and journalists? Or were they the Cold War equivalent of the unsolicited junk mail that clogs mailboxes to this day? There are brief references to leaflets making the rounds among politicians and journalists in certain settings and some evidence of LAB content filtering into African media. What is missing is information on whether leaflets catalyzed specific actions by African politicians or stirred debates among African readers. The letter to the editor pages of African newspapers is the field with perhaps the most potential to answer the latter question, as they often served as forums for debate on social and political issues throughout the twentieth century. As more files on IRD work in the decolonizing Global South become available to researchers, it may become possible to systematically determine whether LAB texts were consequential in these debates, or whether the series was sustained through its nine-year run solely by the optimism of British propagandists.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful for the comments and suggestions provided by James R. Brennan, Robert Rouphail, Jenny Peruski, three anonymous reviewers, and the editors for the Journal of Global History on versions of this article.

Appendix 1

LAB Leaflet No. 17. FCO 168/734, TNA.

From Khartoum:

From Addis Ababa: note: all sent by Air Mail.

From Dakar: note: all by Surface Mail

From Casablanca: note: all by Air Mail

From Rabat/Meknes: note: all by Air Mail