1 Introduction

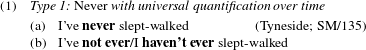

The word never has several uses in English. In its most prototypical function, it is a negative temporal adverb that expresses ‘universal quantification over time’ (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 463) and means ‘not on any occasion’ (Cheshire Reference Cheshire1985: 8; Smith Reference Smith2001: 127). This use of never, henceforth ‘Type 1’, is equivalent to not ever, as shown in (1).Footnote [2]

However, never can also function as a non-quantificational negator equivalent to didn’t (Cheshire Reference Cheshire1982: 67–68; Edwards Reference Edwards1993: 227; Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012; Hughes, Trudgill & Watt Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2013: 29). Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012) distinguish two non-quantificational uses, henceforth ‘Type 2’ and ‘Type 3’. Type 2 never, illustrated in (2), is found in Standard English and is associated with a specific ‘window of opportunity’ in which an event could have occurred but did not (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012). Type 3 never, sometimes called ‘punctual never’ (Palacios Martínez Reference Palacios Martínez2011: 21), is similarly non-quantificational but is always non-standard (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 460). It refers to a single point in time and means ‘not on one specific occasion’ (Smith Reference Smith2001: 127), as in (3).

Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012) find evidence that Type 1 was the original function of never and this eventually developed Type 2 and, subsequently, Type 3 uses. They document the different types of never and examine the history of the form using a predominantly qualitative approach, considering examples taken from corpora including the Helsinki Corpus (1500–1710), the Corpus of Early English Correspondence Sampler (1418–1680) and the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) for their historical analyses, and the BNC, Linguistic Innovators Corpus (LIC) and their own acceptability judgements for insights into modern English. Their data suggests that never has undergone grammaticalisation over time – a type of linguistic change ‘whereby particular items become more grammatical through time’ (Hopper & Traugott Reference Hopper and Traugott2003: 2) through ‘gradual and directed change leading to new pairings of linguistic form and function or content’ (Vincent & Börjars Reference Vincent and Börjars2010: 279).

The current state of sociolinguistic knowledge on the use and distribution of non-quantificational never is relatively limited. It regularly appears in publications which provide an overview of notable syntactic features of certain varieties of English, but few reports acknowledge the distinction between standard non-quantificational uses (Type 2) and non-standard ones (Type 3). The fact that non-quantificational never is frequently noted to be a characteristic of non-standard Englishes worldwide suggests that such reports might be based on observations of the Type 3 function only (see Coupland Reference Coupland1988: 35; Anderwald Reference Anderwald2002: 203; Kortmann & Szmrecsanyi Reference Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi2004; Britain Reference Britain and Kirkpatrick2010; Melchers & Shaw Reference Melchers and Shaw2011: 52–53; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2013: 29; Szmrecsanyi Reference Szmrecsanyi2013). Furthermore, few studies have examined never’s linguistic distribution from a sociolinguistic perspective. Cheshire (Reference Cheshire1985, Reference Cheshire, Cheshire and Stein1997, Reference Cheshire, Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1998) and Cheshire, Edwards & Whittle (Reference Cheshire, Edwards and Whittle1989) are exceptions which consider the semantic and discourse–pragmatic characteristics of never with qualitative discussion of elicited judgements of never’s acceptability in different linguistic contexts. Quantitative studies of never are similarly scarce – most have examined the alternation between Type 1 never and not ever, but as speakers use the never variant near-categorically, there is little variation to be observed in that regard (Tottie Reference Tottie1991; Cheshire Reference Cheshire, Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1998: 34–35; Palacios Martínez Reference Palacios Martínez2011).Footnote [3] To my knowledge at the time of writing, the only prior quantitative variationist study of never and didn’t as non-quantificational negators is Cheshire (Reference Cheshire1982), which identified some linguistic constraints on the variation using spoken data collected in Reading, UK, but focused only on Type 3 uses.

This paper addresses these gaps in our knowledge of never’s linguistic and sociolinguistic profile, through consideration of a fundamental question that emerges out of this current picture of the variation: to what extent does variation in the use of never in present-day English reflect the proposed historical development of the form? As a form grammaticalises, we can expect to see persistence, whereby ‘some traces of its original lexical meanings tend to adhere to it, and details of its lexical history may be reflected in constraints on its grammatical distribution’ (Hopper Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991: 22). To examine this with respect to never, the analysis incorporates insights from syntactic theory into a quantitative variationist methodology in order to gain a fuller understanding of the structure, meaning and development of the form. Doing so also allows us to gain insight into how variation arises from the grammar (see Fasold Reference Fasold, Chambers and Schilling2013: 185) and aligns with the mantra that ‘[w]e cannot fully explain language only as an internal object, any more than we can fully explain language only as an external object’ (Wilson & Henry Reference Wilson and Henry1998: 14). As shown in this paper, without close consideration of the syntactic and semantic constraints on a particular form, it is impossible to properly define a morpho-syntactic variable and its contexts of use according to the Principle of Accountability, which states that: ‘any variable form … should be reported with the proportion of cases in which the form did occur in the relevant environment [emphasis mine – CC], compared to the total number of cases in which it might have occurred’ (Labov Reference Labov1972a: 94). Never presents a particularly complex case in that there is a single form with multiple functions that have arisen at different points diachronically, each with a slightly different meaning and syntactic/semantic distribution, some of which are standard and some of which are non-standard. This complexity may in part explain why quantitative investigation of never has largely been avoided, but as demonstrated in this paper, variationist analysis is possible with careful consideration of its syntax, semantics and historical development.

The analysis proceeds in this vein, embarking on new territory in comparing both Type 2 and Type 3 uses of never and its equivalent didn’t in a quantitative, cross-dialectal analysis of the variation using spontaneous speech corpora from three Northern British locales – Glasgow (Scotland), Tyneside (North East England) and Salford (Greater Manchester). As noted earlier, Type 3 never has been documented in a wide range of vernacular Englishes around the world.Footnote [4] The three varieties under study here also have this use of never, as reported in accounts of Northern Englishes (Beal Reference Beal2004: 125), Scottish English (Miller & Brown Reference Miller and Brown1982; Miller Reference Miller1993: 115; Smith Reference Smith2001: 127–128) and Tyneside English (Beal Reference Beal1993: 198; Beal & Corrigan Reference Beal, Corrigan and Iyeiri2005: 145; Beal, Burbano-Elizondo & Llamas Reference Beal, Burbano-Elizondo and Llamas2012: 58; Buchstaller & Corrigan Reference Buchstaller, Corrigan and Hickey2015: 80). Glasgow, Tyneside and Salford therefore provide an ideal testing ground for systematic, comparative investigation of the variation. Just as typological approaches to linguistic phenomena aim to identify core properties of languages, comparative sociolinguistic studies aim to test whether the constraints on a phenomenon operate in the same way across different dialects, in order to assess their structural similarity and their respective positioning in terms of the advancement of linguistic change (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2013: 186).

This study demonstrates how linguistic constraints on non-quantificational never as a standard variant in Type 2 contexts – particularly relating to the lexical aspect of the verbs and the types of events they depict – maintain an influence on its usage in its newer, non-standard use in Type 3 contexts. The results show that as never expanded its linguistic distribution and changed in meaning between Type 2 and Type 3 contexts, it expanded its repertoire of discourse–pragmatic functions. While Type 2 environments almost always involve the expression of counter-expectation (regardless of variant), in Type 3 contexts the highest rates of never are reserved for when a speaker wishes to contradict a previously-stated proposition.

The following section explains the linguistic properties that distinguish the different types of never (Section 2), prior to a consideration of the diachronic development and synchronic distribution of never (Section 3). The sections that follow give details of the corpora and sample used for the investigation (Section 4), the variable context and data extraction (Section 5), and the hypotheses and coding (Section 6). Results of the quantitative analysis are presented in Section 7, followed by conclusions in Section 8.

2 Differentiating types of never

Drawing upon Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012), this section delineates the linguistic properties which distinguish the Type 1, Type 2 and Type 3 uses of never, and how these differ from some more marginal functions. Although the dependent variable in the present study is non-quantificational never vs. didn’t in Type 2 and Type 3 contexts, the linguistic characteristics of each type of never are outlined here because all are said to originally stem from Type 1 through grammaticalisation (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 473). Understanding how Type 1, Type 2 and Type 3 uses of never relate to one another historically and in terms of their semantic and syntactic properties is essential to address the central research question which asks to what extent the newer, non-quantificational uses exhibit behaviours that reflect their historical development. This is also essential for reliable data sorting and coding of the variable (see Section 5).

2.1 Type 1: Universal quantification over time

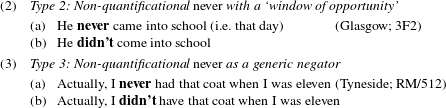

The prototypical use of never is Type 1, which expresses universal quantification over time, as follows:

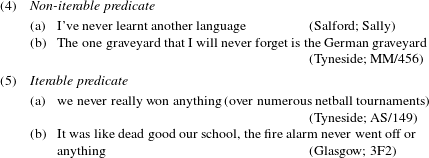

Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 463) argue that this type of never addresses a ‘question under discussion’ in the sense of Roberts (Reference Roberts1996), namely either: (i) When is/was/will p (be) true? or (ii) How often is/was/will p (be) true? Question (i) is relevant when never quantifies over a non-iterable predicate, i.e. where there was ‘some instant (or longer stretch of time) at which p is true’ (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 463), as in (4). Question (ii) is relevant for iterable predicates, i.e. where never ‘[denies] the assumption that the relevant proposition is true on multiple separate occasions within D’ (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 465), as in (5).

Appealing to Partee’s (Reference Partee1973) proposal that sentences with tense contain a temporal variable, Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 464) state that never ‘saturates this variable’ with non-iterable predicates, but not with iterable predicates. This explains why non-iterable predicates with Type 1 never, like those in (4), prohibit the use of temporal adverbials (e.g. this year, yesterday), whereas they are licensed with iterable predicates (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 464).

2.2 Type 2: Non-quantificational with ‘window of opportunity’

Unlike Type 1 never, Type 2 never does not quantify over time and is ‘equivalent to ordinary sentential negation’ (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 466). Type 2 never is identifiable by its reference to a ‘temporally restricted ‘window of opportunity’, given or inferable in context, in which the relevant event could theoretically have taken place at any time but didn’t’ (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 467). At the time of speaking, this window must be closed – hence, Type 2 never only occurs with the preterite (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 467). Type 2 never is also limited to achievement predicates that refer to the completion of a specific task (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 467–469), as explained further in Section 5.3. Some tokens of Type 2 never from my data are given in (6).

Although Type 2 never may seem similar to Type 1, if they were the same we would expect Type 2 never to be concerned with the ‘how often?’ question with iterable predicates, which is not the case (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 466). For example, someone was not expected to receive a specific, single text message several times (6a), bring a biscuit to the interview several times (6b) (because, in this context, the fieldworker set up the interview but intentionally left the participants alone to talk), or to go to a single parents’ evening several times (6c). The events are expected to occur only once within a ‘window of opportunity’.

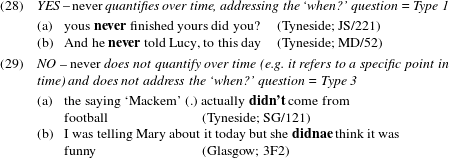

2.3 Type 3: Non-quantificational generic negator

Non-quantificational never in Type 3 contexts marks sentential negation, just like Type 2 never (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 469). However, the linguistic context differentiates the two, which also creates a distinction between a standard use – Type 2 – and a non-standard use – Type 3 (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 469). While Type 2 never is limited to achievement predicates with a ‘window of opportunity’, Type 3 can occur with a wide range of predicate types (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 469), as the examples in (7) illustrate.

Type 3 never is strongly associated with the preterite and is considered equivalent to didn’t (Labov Reference Labov and Shuy1972b; Cheshire Reference Cheshire1982: 67–68; Edwards Reference Edwards1993: 227; Smith Reference Smith2001: 128; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2013: 29). Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 469–470) agree, but hypothesise that this could be because with other tenses never can be ambiguous between Type 1 (where it has a habitual interpretation) or Type 3 (where it has a non-quantificational interpretation), as shown in (8), with examples in the present tense.

Type 3 never can also occur in clause-final position with an elided VP, as in (9), which could represent its reanalysis from a phrasal adverb to a head (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 470–471).Footnote [5]

Type 3 never has been described as emphatic or at least potentially emphatic (Beal Reference Beal1993: 198; Hickey Reference Hickey and Hickey2004: 524; Beal & Corrigan Reference Beal, Corrigan and Iyeiri2005: 145; Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 460; Buchstaller & Corrigan Reference Buchstaller, Corrigan and Hickey2015: 80). What individual authors mean by ‘emphatic’ is not always clear, but emphasis can generally be defined as ‘the exceptional force, intensity or otherwise unusual form of expression … which serves to indicate or attract attention to special meaning, importance, or prominence’ (Lauerbach Reference Lauerbach, Östman and Verschueren2011: 135). Emphatic negation in particular involves denial of a proposition and ‘that non-p is the most striking thing among the salient alternatives’ (Eckardt Reference Eckardt2006: 163). It has indeed been noted that Type 3 never can be used to explicitly deny propositions (e.g. He never! – Cheshire Reference Cheshire1982: 68; No I never! – Coupland Reference Coupland1988: 35) or assumptions (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 460). With respect to Scottish English, however, Miller (Reference Miller1993: 115) describes never as ‘regularly not emphatic, unlike the standard English example You will never catch the train tonight (= It is utterly impossible that you will catch the train tonight.)’. While this could indicate that Type 3 never is no more emphatic than didn’t in Scottish English (see also Miller Reference Miller, Kortmann and Upton2008: 303), it might instead simply reflect the observation that Type 1 never quantifies over time whereas Type 3 never does not. The pragmatic force of never across dialects therefore warrants further investigation, which this study pursues through comparison of a Scottish variety of English (Glasgow) with two Northern English varieties (Tyneside and Salford).

2.4 Other uses of never

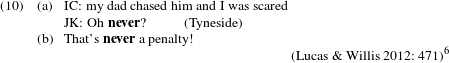

Two more marginal uses of never are Type 4 (categorical denial) and Type 5 (idiomatic uses), as Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012) outline. Type 4 never is not quantificational over time, but appears to quantify ‘over possible perspectives on a state of affairs’, often expressing surprise (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 471). As (10) shows, speakers use it to categorically deny a proposition (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 461). Type 4 never can be used with various tenses and predicate types, and is found in many varieties of English including Standard English (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 471).

Type 5 uses of never comprise idiomatic fixed expressions in which never is non-quantificational, including never know (11a), never fear and never mind (11b) (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 472).

Having described the different types of never, the next section outlines their origin and diachronic development, as relevant to the research question of how the present-day variation might show persistence of the syntactic–semantic properties and distributional behaviour of never’s earlier uses as it has grammaticalised.

3 The origins and historical development of never

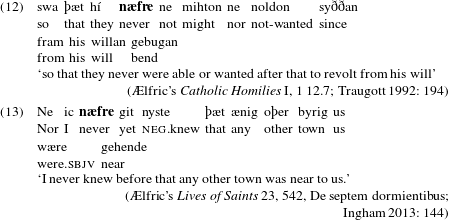

As already noted, never first appeared in English with its Type 1 meaning before developing other functions – a trajectory that is consistent with cross-linguistic trends whereby negative temporal adverbs often grammaticalise to become non-quantificational negators (see Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 473, inter alia). Type 1 appears as early as Old English, as shown in (12). Although Cheshire (Reference Cheshire, Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1998) suggests that Type 3 never was also found in Old English, Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012) show that this is not the case, as the examples she cites are actually Type 5 uses (e.g. never knew) similar to (13):

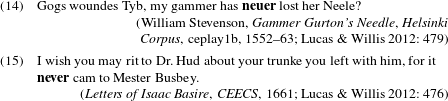

Type 4 was the next to appear, most likely as a development of Type 1 never given that it is not restricted to certain types of predicate and it ‘does seem to retain an element of quantification – over perspectives on a situation – and it is not clear how this could have arisen out of a use of never as a straightforward negator’ (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 479). Type 4 never first appeared in Early Modern English, as in (14), but was not used more widely until the 19th century (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 479). Type 2 never, as in (15), was also first used in Early Modern English.

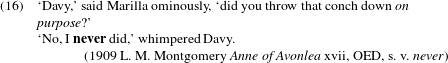

Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 474–475) find that Type 1, Type 2 and Type 5 uses of never all appear in the Early Modern component of the Helsinki Corpus (1500–1710) and Corpus of Early English Correspondence Sampler (1418–1680), alongside one instance of Type 4 never, whereas Type 3 does not appear at all. Their data indicates that Type 3 never was not used until the mid-19th century and increased in frequency in the subsequent century, with examples such as (16) (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 476).

This diachronic development of never from Type 1 negator (the oldest type) to Type 3 negator (the newest) shows a reduction in its ‘expressive force’ over time as it developed non-quantificational uses (Cheshire Reference Cheshire, Cheshire and Stein1997: 70: Reference Cheshire, Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1998: 31), which is consistent with Jespersen’s Cycle (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1917). The innovation of Type 3 never likely arose when speakers acquired non-quantificational never but without the specific (Type 2) constraints on its use (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 478). The present investigation will examine whether these older meanings and constraints persist in shaping its newer uses in the form of non-categorical constraints.

4 Corpora and sample

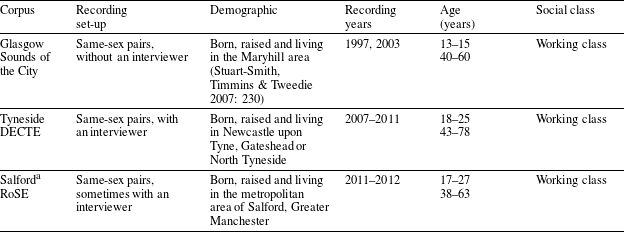

The quantitative investigation of the variation between never and didn’t uses three corpora of English, representing varieties spoken in Glasgow (Scotland), Tyneside (North East England) and Salford (Greater Manchester) respectively, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Map of localities.

The three corpora are the Glasgow Sounds of the City corpus (Stuart-Smith & Timmins Reference Stuart-Smith and Timmins2011–2014), the Diachronic Electronic Corpus of Tyneside English (DECTE, Corrigan et al. Reference Corrigan, Buchstaller, Mearns and Moisl2010–2012) and the Research on Salford English corpus (RoSE, Pichler Reference Pichler2011–2012), which the author has used previously for the investigation of negation phenomena in British English (Childs Reference Childs2017a, Reference Childsb for cross-dialectal comparisons; Childs Reference Childs2019 on Tyneside). All three corpora contain recordings of pairs of participants, who are native speakers of their local variety of English, in casual conversation (with or without an interviewer). The samples of speakers chosen from these corpora were intended to be as comparable as possible (see D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy, Maguire and McMahon2011): all were interviewed in same-sex pairs, were working-class (as indicated in the metadata), and were chosen to form ‘younger’ vs. ‘older’ groups for apparent-time analysis (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Wikle, Tillery and Sand1991), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Overview of sample demographic.

aOne speaker was born in the city of Manchester rather than Salford.

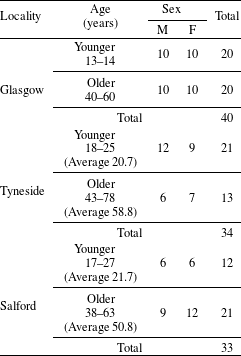

As the speakers in Sounds of the City were listed as aged 13–15 and 40–60 (specific ages were not provided), these age groups formed the basis for selecting speakers from the other two corpora. Because of the unavailability of speakers aged 13–15 in the other two corpora and the lack of 40–60 year-olds in DECTE, the age ranges had to be expanded slightly. Nevertheless, there is a clear distinction between the ‘younger’ and ‘older’ categories in each dataset, as Table 2 shows, and the sample consistently exceeds the ‘5 speakers per cell’ recommendation (Meyerhoff, Schleef & MacKenzie Reference Meyerhoff, Schleef and MacKenzie2015: 22).

Table 2 Final sample.

5 The variable context and data extraction

As noted earlier, the variable of investigation is non-quantificational uses of never – Type 2 and Type 3 – in variation with didn’t. Although Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 470) note the potential for never to be used in place of verbs other than didn’t in Type 3 contexts (including tenses besides the preterite), possible examples they find are ambiguous between Type 1 and Type 3 uses (see Section 2.3, example (8)). Indeed, the consensus is that non-quantificational never and didn’t are equivalent negators (Cheshire Reference Cheshire1982: 67–68; Edwards Reference Edwards1993: 227; Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2013: 29). This unites the Type 2 and Type 3 uses of never in meaning and differentiates them from all others (see Section 2).

The present analysis concerns a single variable akin to Cheshire (Reference Cheshire1982), but my approach differs in that I do not focus only on the Type 3 use but distinguish the two linguistic contexts in which the variants alternate: (i) Type 2 contexts, i.e. achievement predicates in the preterite with a ‘window of opportunity’ where an event could have occurred but did not (in which never is a standard variant); and (ii) Type 3 contexts, i.e. predicates in the preterite where there is no ‘window of opportunity’ but never nonetheless has a non-quantificational meaning (in which never is a non-standard variant). Separating these is essential to establish the linguistic constraints on never and how it has grammaticalised from Type 1 to Type 2 to Type 3 contexts. Conflating these would mask not only the differences in their linguistic licensing but also the fact that Type 2 is standard whereas Type 3 is not.

Tokens of the variable were extracted using AntConc (Anthony Reference Anthony2011) by searching for never and didn’t, plus equivalents of the latter, e.g. did not and (for Glasgow) didnae.Footnote [7] The extracted tokens were scrutinised to isolate those within the definition of the variable, i.e. semantically-equivalent tokens of non-quantificational never and didn’t in Type 2 or Type 3 contexts. Type 4 never (which appeared only once) and Type 5 tokens, including their equivalents with didn’t or where verbs had been elided (e.g. Did you know that? I didn’t), were excluded.

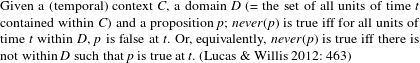

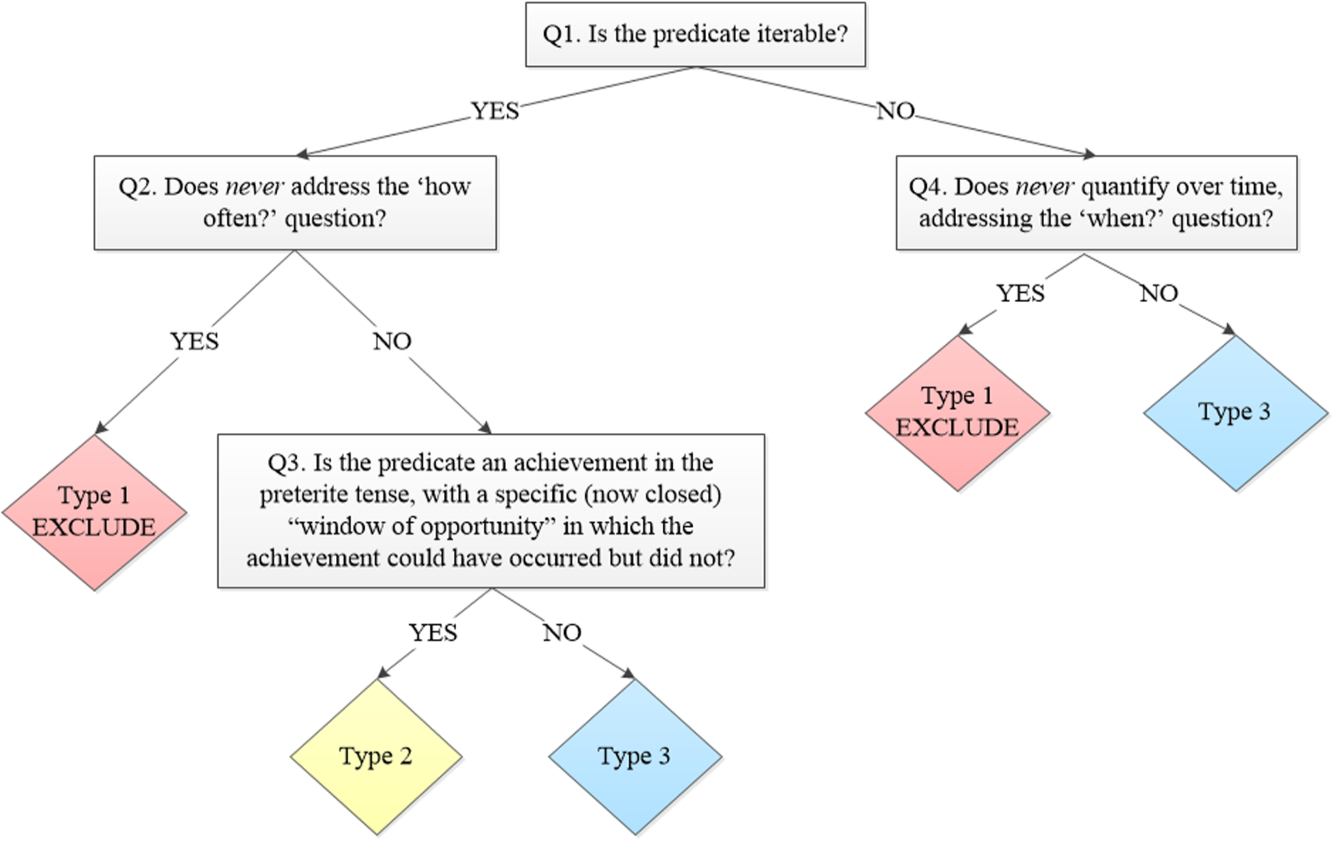

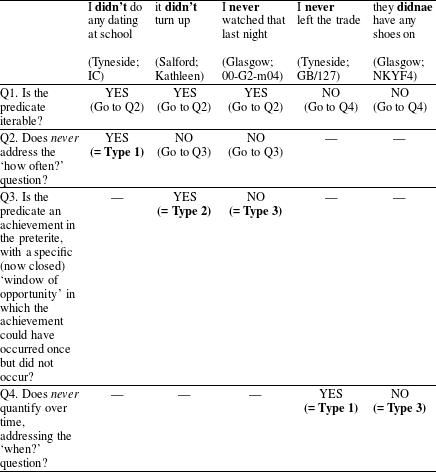

From the remaining tokens, it was necessary to establish whether they were Type 1 (to be excluded), Type 2 or Type 3. Tokens of non-quantificational never and its variant didn’t with an elided verb were necessarily Type 3. For the rest, I devised a decision tree comprising a series of questions to ask with respect to each token, shown in Figure 2. The questions were chosen for their ability to distinguish the different types of never, based on the properties explained by Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012), discussed earlier. Coding the tokens of didn’t involved constructing the alternative with never (e.g. he didn’t go vs. he never went) and applying the decision tree in the same way.Footnote [8] This ensured that each token was subjected to the same coding procedure, minimising the subjectivity of the decision-making process (see also Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Hesson, Bybel and Little2015, who took a similar approach in coding general extenders).

Figure 2 Decision tree.

The following sections focus on each of the four questions in Figure 2 to explain how they allow the different uses of never/didn’t to be distinguished. Explaining the inclusion and exclusion of tokens in the variable and its contexts is essential to any quantitative variationist analysis (see Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2006: 86–88), but is even more important given that, to my knowledge, no previous study has quantified variation between never and didn’t in separate Type 2 and Type 3 contexts. The high level of detail in the remainder of this section serves to make these procedures transparent.

5.1 Q1: Is the predicate iterable?

Non-iterable predicates do not allow the addition of phrases that explicitly restrict the temporal domain over which never applies (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 464) – for example, (17a). The symbol # in (17b) indicates the impossibility of a Type 1 iterable reading in this context – instead, a Type 3 reading ensues.

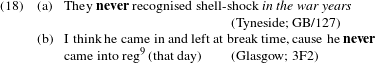

Iterable predicates, on the other hand, allow explicit restriction on the temporal domain that never operates over (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 465), as in (18).

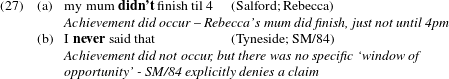

5.2 Q2: Does never address the ‘how often?’ question?

Answering YES to Q1 entails that the predicate is iterable and allows temporal restriction on the domain of never, as is the case for the sentences in (18). Q2 asks whether those sentences address the ‘how often?’ question, i.e. how often was p true?. Example (18a) addresses this question, specifically how often did they recognise shell-shock in the war years? Following the decision tree in Figure 2, example (18a) must be an example of Type 1 never because there were multiple separate opportunities for shell-shock to be recognised. Example (18b), on the other hand, does not address the ‘how often?’ question: we do not expect the referent to come into a specific registration period at school multiple times. Example (18b) therefore must be tested further with Q3.

5.3 Q3: Is the predicate an achievement in the preterite, with a specific (now closed) ‘window of opportunity’ in which the achievement could have occurred but did not?

Type 2 contexts obligatorily feature an achievement predicate in the preterite that depicts a closed ‘window of opportunity’ in which an event could have occurred but did not (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 466). If a token satisfies these conditions, i.e. YES is the answer to Q3, it is a Type 2 token. If not, i.e. NO is the answer to Q3, it is a Type 3 token.

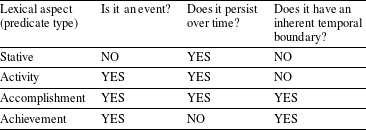

To answer Q3, the tokens were coded for the lexical aspect of their predicate – that is, ‘the inherent temporal structure of a situation’ (Croft Reference Croft2012: 31) – according to Vendler’s (Reference Vendler1957) classic four-way distinction between stative, activity, accomplishment and achievement predicates. Although at this point we are primarily concerned with whether the predicate is an achievement or not, all four categories are defined here, as comparing them gives a clearer understanding of the properties of achievements. Lexical aspect is also a factor in the quantitative analysis (see Section 7 below).Footnote [10]

5.3.1 Stative, activity and accomplishment vs. achievement

Stative predicates denote a constant state over time (Vendler Reference Vendler1957: 147; Croft Reference Croft2012: 34) and cannot be used to answer what happened? (Miller Reference Miller2002: 144). They do not take a progressive form in Standard English, e.g. *I’m having a car (Comrie Reference Comrie1976: 35), though there are exceptions, such as stative mental verbs (Römer Reference Römer2005: 116–117).Footnote [11] Stative predicates include those with the verbs need, like, live and understand, as well as those in (19).

Activities, on the other hand, are dynamic events that proceed in the same way over an unbounded period of time (Vendler Reference Vendler1957: 146; Croft Reference Croft2012: 34). They can occur in the progressive, and in the preterite they can be used with adverbials such as for hours (Miller Reference Miller2002: 144–145). Verbs that denote activities include walk, talk, swim, sing and those in (20).

Accomplishments are also dynamic events, but are bounded and occupy a defined period of time (Vendler Reference Vendler1957: 149; Miller Reference Miller2002: 146). They ‘lead to a ‘natural’ endpoint such as arriving at the other side of the street or the end of the book’ (Croft Reference Croft2012: 34–35). These predicates can occur in the progressive and consist of ‘an activity phase and then a closing phase’ (Miller Reference Miller2002: 145), such as watching a programme (21a) or building something (21b).

Achievement predicates are similar to accomplishments in the sense that they too are dynamic events that occur within a bounded time period, but for achievements this period is an ‘instant’ (Vendler Reference Vendler1957: 149; Miller Reference Miller2002: 145–146; Croft Reference Croft2012: 34). Achievements therefore have ‘no time elapsing between the beginning and the end of the event; the beginning and the end occur at the same time’ (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2008: 78). Examples of verbs which typically form achievement predicates are ask, take, go, hit and those in (22).

Table 3 below summarises the characteristics of these four predicate types.

Table 3 Summary of lexical aspect categories (table adapted from Miller Reference Miller2002: 146).

Achievement tokens are now examined further because only the achievements which could have taken place in a specific ‘window of opportunity’ can be Type 2.

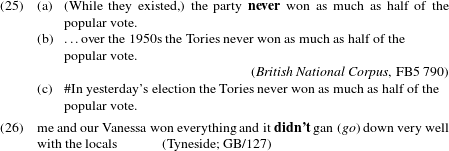

5.3.2 Achievements that could have taken place in a (now closed) specific ‘window of opportunity’

Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 468) state that achievements do not permit Type 2 never ‘if the predicate refers to some chance event’, which they exemplify with (23). The instances of never in (23a) and (23b) are Type 1 because they allow temporal restriction (YES to Q1) and address the ‘how often?’ question (YES to Q2), i.e. she did not on any occasion forget to get the hen-food. As their example with yesterday in (23c) shows, a Type 2 reading is impossible.

It is not clear, however, what is meant by ‘chance event’. Achievements with verbs such as hear (24) are likely candidates for chance events because a subject does not intend to hear something – just as with forget in (23). Hear is therefore not expected to licence Type 2 never, but as (24) shows, this interpretation is available. I therefore suggest that Lucas & Willis’ (Reference Lucas and Willis2012) condition that Type 2 achievements must be ‘non-chance’ events is not necessary and the reason why to forget to prohibited Type 2 never is because it is a negative-implicative predicate.Footnote [12]

Another restriction on Type 2 tokens is that the achievement must relate to ‘the completion of a specific task, not merely to some process coming to an end and resulting in one of several possible outcomes’, as shown with Lucas & Willis’ (Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 468) example won as much as half of the popular vote in (25). Examples of this kind in my data similarly do not allow a Type 2 reading but are interpreted as Type 3, as (26) shows when reconstructed with never (i.e. it never went down very well).

The final stipulation to characterise a token as ‘Type 2’ is that there must have been a specific ‘window of opportunity’ where an achievement could have occurred but did not, which was closed at the time of speaking (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 467). For example, the tokens in (27) are Type 3 rather than Type 2 because although they depict achievements in the preterite, they do not refer to a specific closed ‘window of opportunity’.

We have now reached the end of the trail of questions that follows from a YES response to Q1 in Figure 2. A NO response to Q1 necessitates asking Q4, as follows.

5.4 Q4: Does never quantify over time, addressing the ‘when?’ question?

Q4 is relevant to those tokens that do not permit explicit restriction of the temporal domain over which never applies (NO to Q1). I now ask whether these quantify over time and address the question ‘when was p true?’ (Lucas & Willis 2012: 463), as shown in (28) for YES and (29) for NO.

These questions from the decision tree in Figure 2 have allowed the majority of tokens to be categorised into Type 2 and Type 3 groups, with Type 1 excluded. The following section describes the handling of ambiguous tokens.

5.5 Ambiguous tokens

Some tokens are ambiguous as to whether they refer to a single point in time (Type 3) or multiple occasions (Type 1). In relation to Q1, although there is a strong association between stative predicates and non-iterability (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 464), some statives can have an iterable reading, e.g. where living with someone (30) may have been true on multiple separate occasions over a period of time.

Similarly, some iterable predicates may or may not address the question ‘how often was p true?’. For example, in (31) below, Abbey may be referring to a single Christmas (Type 3) or several (Type 1).

Such ambiguities were often resolved by considering the discourse context and asking whether it was more likely that the sentence addresses how often was p true? (Q2) or when was p true? (Q4). Where this could not be satisfactorily resolved, the token was excluded from the sample.

5.6 Summary of coding procedure

Table 4 includes five tokens of never/didn’t that illustrate all possible outcomes of Q1–4, to show the processes involved in deciding whether tokens should be excluded (Type 1) or belong to the Type 2 or Type 3 contexts. The final number of tokens for quantitative analysis is 97 for Type 2 (Glasgow = 36, Tyneside = 34, Salford = 27) and 235 for Type 3 (Glasgow = 57, Tyneside = 117, Salford = 61). Although the dataset is of a relatively modest size, this is not atypical of grammatical variables, and is not surprising when we consider the low frequency of negative clauses compared to affirmatives (Tottie Reference Tottie1991) and the fact that this study deals with a specific subset of these.

Table 4 Demonstration of coding procedure with example tokens.

6 Hypotheses and coding independent variables

As described in this section, the tokens were coded for linguistic factors which were hypothesised to affect the choice of never vs. didn’t in Type 2 or Type 3 contexts, to examine how older uses of never shape its newer uses as it grammaticalises.

6.1 Lexical aspect

The tokens were coded for the lexical aspect of the predicate as detailed in Section 5.3: stative, activity, accomplishment, achievement. Type 2 tokens are necessarily achievements, whereas Type 3 tokens can have any predicate type.Footnote [13] Given the temporal development of Type 2 into Type 3 never, it is hypothesised that in Type 3 contexts, never (as opposed to didn’t) will be used at higher frequencies with achievements than with other predicate types, demonstrating persistence of the aspectual constraints.

6.2 Discourse function

As noted in Section 2.3, non-quantificational never, especially in Type 3 contexts, is often said to have an ‘emphatic’ function – either variably or in general (Beal Reference Beal1993: 198; Hickey Reference Hickey and Hickey2004: 524; Beal & Corrigan Reference Beal, Corrigan and Iyeiri2005: 145; Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 460; Buchstaller & Corrigan Reference Buchstaller, Corrigan and Hickey2015: 80). This emphatic quality of never has been characterised as overstatement (Cheshire Reference Cheshire, Cheshire and Stein1997: 75), negating an assumption evoked by prior discourse (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 460), or negating an explicit assertion (Coupland Reference Coupland1988: 35). The latter two, here labelled ‘counter-expectations’ and ‘contradictions’ respectively, can be characterised as expressions of ‘disclaim’, whereby ‘some prior utterance of some alternative position is invoked so as to be directly rejected, replaced or held to be unsustainable’ (Martin & White Reference Martin and White2005: 118).

The claims that never is emphatic are based on qualitative observations of speech and/or intuitions and therefore empirical evidence in support of these is lacking. Furthermore, no previous work has established whether this emphatic quality applies equally to Type 2 and Type 3 never. Testing these claims quantitatively will provide insight into whether never has developed an emphatic quality, as is common for negative adverbs cross-linguistically (Willis, Lucas & Breitbarth Reference Willis, Lucas and Breitbarth2013a: 14). The hypothesis is that when a speaker explicitly contradicts a previous speaker’s proposition (‘contradictions’) or expresses a negative proposition that was expected to be true (‘counter-expectations’), never will be used more frequently than in contexts where there was no prior expectation as to the truth/falsity of the proposition or the expectation was met (‘no-counter-expectations’). This follows from contradictions and counter-expectations being more pragmatically-marked than no-counter-expectation contexts, since the speaker indicates a contrast between what they say and what was previously said or assumed.

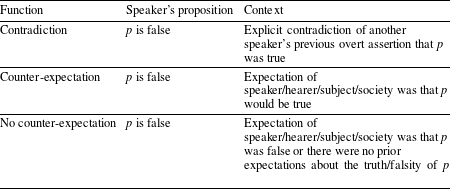

Table 5 summarises the three coded functions and their definitions, which are explained further in the remainder of this section. By containing the word never as the sole negator, the tokens express a negative proposition (p), but how this relates to preceding discourse and/or speaker expectations differs depending on the context. A small number of ambiguous utterances were excluded from analyses of this factor (N = 3).

Table 5 Coding schema for discourse function.

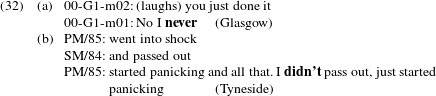

Contradictions are similar to what Wallage (Reference Wallage2012: 5) terms ‘denials of an antecedent proposition’, where ‘the negative proposition denies an earlier proposition that was explicitly stated in the discourse’, but they must additionally result in ‘exclusion’, i.e. one proposition must be true and the other false (see Frawley Reference Frawley1992: 28), as shown in (32).

Counter-expectations feature a proposition that was expected to be true but was false. The prior expectation can be held by a speaker, hearer, or third-party referenced as the subject, or is reasonably assumed to be held by society in general. These expectations can arise due to prior discourse, speaker knowledge, or general world knowledge (see Ocampo Reference Ocampo, Downing and Noonan1995: 438). The examples illustrate how the falsity of the proposition can be unexpected for the speaker (33a), hearer (33b), or society more generally (33c).

The final category of utterance, ‘no counter-expectation’, are those where the false proposition was expected to be false or there was no prior expectation about its truth/falsity. For example, in (34a) below, the interviewee confirms the fieldworker’s expectation, on the basis of prior discourse, that he and his brother (his co-interviewee) did not get on well when they were younger. In (34b), Moira’s assertion that’s why I never went for a tall man is an unanticipated statement that does not relate to any prior expectation.

6.3 Locality, speaker age and speaker sex

The tokens were coded for the speakers’ locality – Tyneside, Glasgow or Salford. Speaker age comprised two groups of younger and older speakers (see Section 4) for apparent-time analysis (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Wikle, Tillery and Sand1991). The speakers had described themselves as either male or female and thus sex was coded as such to examine whether there was any differentiation in the frequency of never between the two groups that might reflect change in progress (Labov Reference Labov2001).

7 Results of quantitative analysis

This section presents the results of the quantitative analysis of the alternation between non-quantificational never and didn’t in Glasgow, Tyneside and Salford, in Type 2 and Type 3 variable contexts. This begins with the overall distribution per locality (Section 7.1) followed by consideration of the factors that were hypothesised to affect the choice of variant (Sections 7.2–7.4). Finally, a mixed-effects logistic regression is undertaken to ascertain the relative impact of these factors (Section 7.5).

7.1 Overall distribution

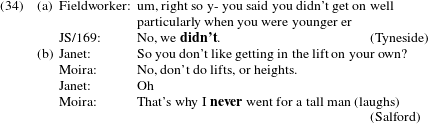

The overall frequency of never and didn’t in Type 2 and Type 3 contexts for each locality is given in Figure 3. In the analysis of regional variation in frequency, we must always bear in mind the fact that these corpora were collected by different researchers; nevertheless, non-quantificational never is present in all three varieties here, which reflects the fact that it is a supra-local feature of English (Britain 2010; Szmrecsanyi 2013: 70). Never’s status as non-standard in Type 3 contexts results in the variant being used to a lesser extent than when it is a standard variant in Type 2 contexts. However, there are still differences in the frequency of never across locales, which are significant for both Type 2 (

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03C7}^{2}$

= 22.428, df = 2, p < .001) and Type 3 (

$\unicode[STIX]{x03C7}^{2}$

= 22.428, df = 2, p < .001) and Type 3 (

![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x03C7}^{2}$

= 20.509, df = 2, p < .001). In Type 2 contexts, never usage increases from the southernmost community (Salford) to the northernmost (Glasgow) – only in Glasgow is it the majority variant. Glasgow speakers also use never as a Type 3 non-standard negator more often (at a rate of 24.6%) than speakers from Tyneside and Salford (who use it < 5% of the time).

$\unicode[STIX]{x03C7}^{2}$

= 20.509, df = 2, p < .001). In Type 2 contexts, never usage increases from the southernmost community (Salford) to the northernmost (Glasgow) – only in Glasgow is it the majority variant. Glasgow speakers also use never as a Type 3 non-standard negator more often (at a rate of 24.6%) than speakers from Tyneside and Salford (who use it < 5% of the time).

Figure 3 Overall distribution of variants in Type 2 and Type 3 contexts.

Supra-local features are sometimes assumed to pattern socially rather than geographically (Coupland Reference Coupland1988: 35), but here we see regional differences. The suggestion that non-quantificational never ‘appears to be spreading in Broad Scots’ (Miller & Brown Reference Miller and Brown1982: 15), in which it is said to be ‘the normal negative with past tense verbs’ (Miller Reference Miller1993: 115), suggests an association between the use of this feature and Scottish varieties of English. This is consistent with its prevalence in Glasgow compared to the two English locales in Figure 3.

7.2 Lexical aspect

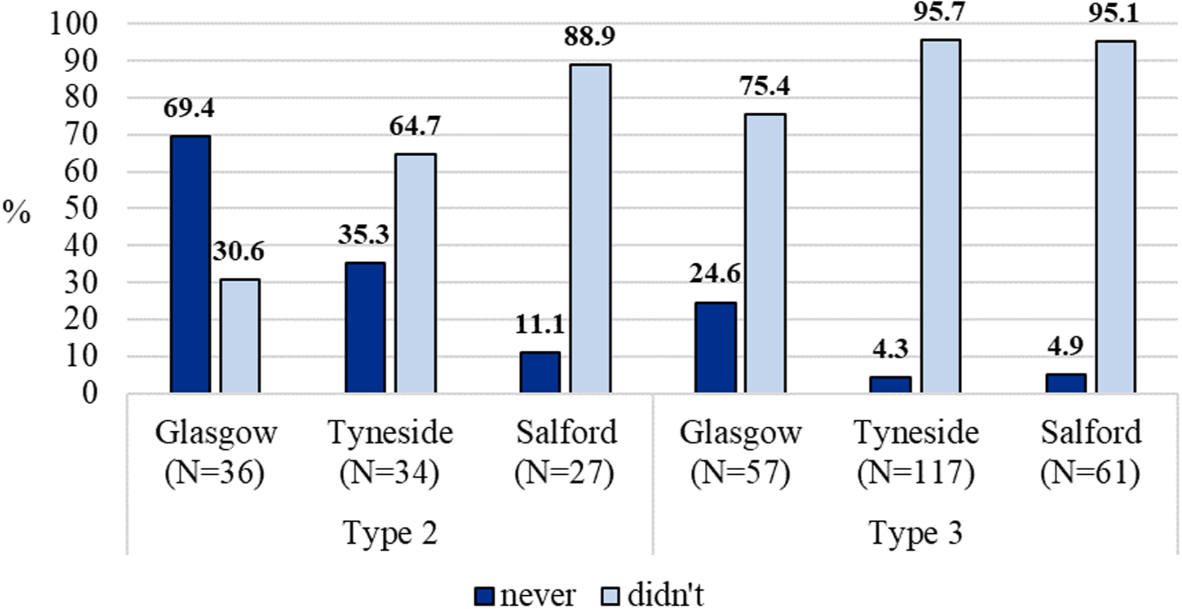

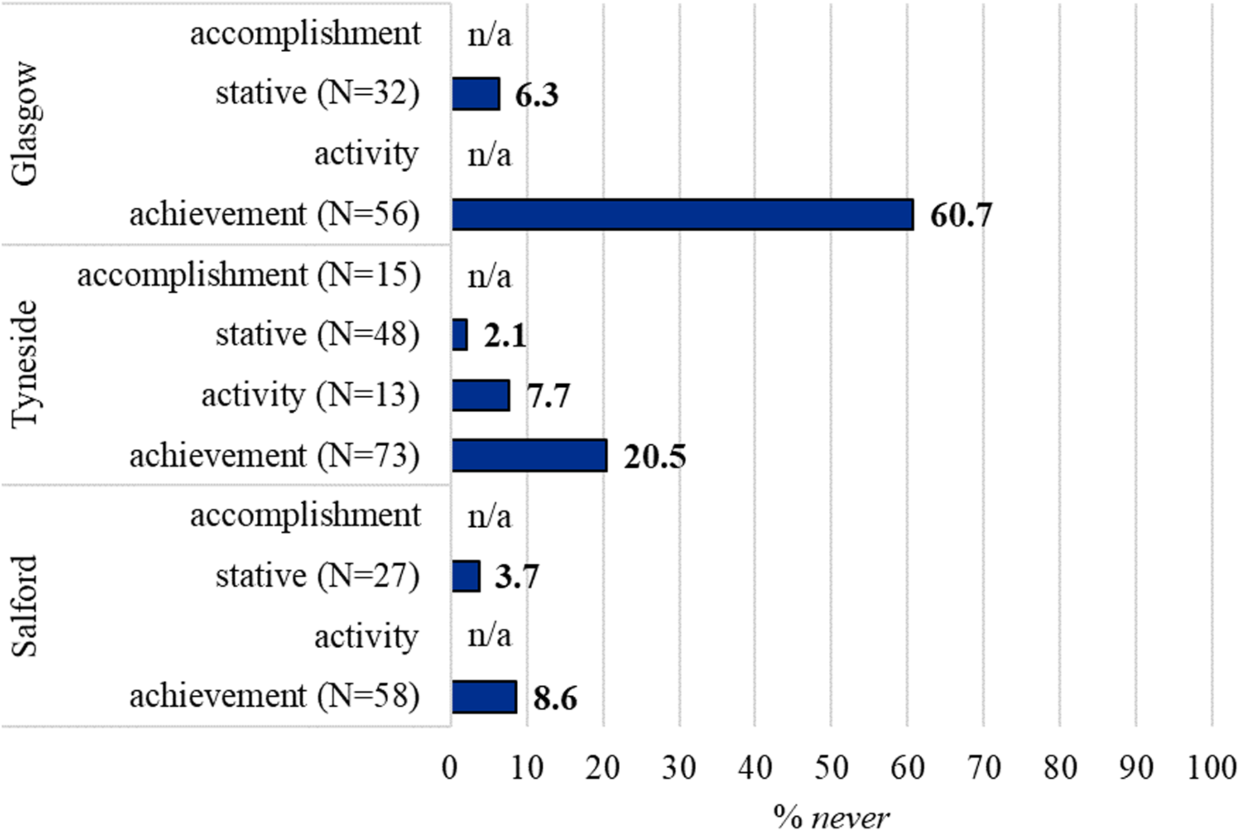

By definition, Type 2 never occurs with achievement predicates. Type 2 never is considered the historical predecessor of never used in Type 3 contexts, where it can occur with a much wider range of predicates (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012). Therefore, it was hypothesised in Section 6.1 that in Type 3 contexts, never would be used more frequently than didn’t with achievement predicates than other predicate types. The results in Figure 4 confirm this hypothesis. A chi-squared test is inappropriate for this distribution due to some low cell counts, but Fisher’s Exact Test can reliably be used instead (Warner Reference Warner2008: 334) and this yields a significant result (p < .05).

Figure 4 Distribution of Type 3 never (vs. didn’t) according to lexical aspect.

The fact that Type 3 never is used at the highest relative frequency in achievements demonstrates persistence (Hopper Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991: 22), in that the form’s distribution reflects its earlier roots in Type 2 achievement predicates. Accomplishments promote the use of never over didn’t only slightly less than achievements, which is no surprise given that these two predicate types have similar semantic properties: both depict dynamic events that take place in a bounded time period (Vendler Reference Vendler1957: 149). In contrast, never is least likely to occur in the two temporally-unbounded predicate types: activities and statives. The semantics of Type 3 never as a ‘punctual’ negator that refers to a specific point in time (Smith Reference Smith2001: 127) therefore results in its greater compatibility with predicates that similarly refer to single instants (achievements) or events with an inherent boundary (accomplishments), rather than unbounded events or states. This can explain Cheshire’s (Reference Cheshire, Cheshire and Stein1997) suggestion that speakers find never less acceptable when it refers to shorter periods of time. Although her conclusion did not appear to be well supported by the intuition data collected from her participants (e.g. it was difficult to disentangle the potential influence of other factors when considering the test sentences),Footnote [14] it nevertheless seems to hold true in the sense that, as my data show, the non-standard use of never is more common in predicates with a restricted temporal boundary.

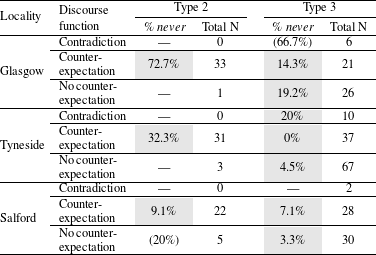

Figure 5 tests the robustness of these trends across the three communities (excluding predicate types that occurred less than 10 times in each locale).Footnote [15] As before, never is most likely to be chosen over didn’t in achievements as opposed to any other predicate type. The distribution is significant in Glasgow (Fisher’s Exact Test, p < .001) and Newcastle (p < .01), but not Salford. These frequencies of never in Type 3 achievement predicates are strikingly similar to the rates of never usage in Type 2 (necessarily achievement) predicates from Figure 3 earlier: 69.4% (Type 2) and 60.7% (Type 3) for Glasgow, 35.3% (Type 2) and 20.5% (Type 3) for Tyneside, 11.1% (Type 2) and 8.6% (Type 3) for Salford. As such, the non-standardness of Type 3 never appears to be somewhat neutralised in achievement predicates, since the rate of use does not change significantly between Type 2 and Type 3 achievement contexts.Footnote [16] This neutralisation of structure and meaning in discourse is ‘the fundamental discursive mechanism of (nonphonological) variation and change’ (Sankoff Reference Sankoff and Newmeyer1988: 153).

Figure 5 Distribution of Type 3 never (vs. didn’t) according to lexical aspect, per locality.

An area of cross-dialectal variation that emerges from Figure 5 is that accomplishments do not occur with never at all in Tyneside, even though in the dataset overall they promoted the use of the variant almost as much as achievements, though this could be due to low token numbers for this category. The rate at which never occurs in statives and achievements (the two categories that can be compared across all three varieties) is proportional to each locality’s overall frequency of the variant in Type 3 contexts, i.e. most frequent in Glasgow, followed by Tyneside, then Salford. Thus, the more often speakers use a variant overall, the more likely they are to use it in its less favoured environments.

7.3 Discourse function

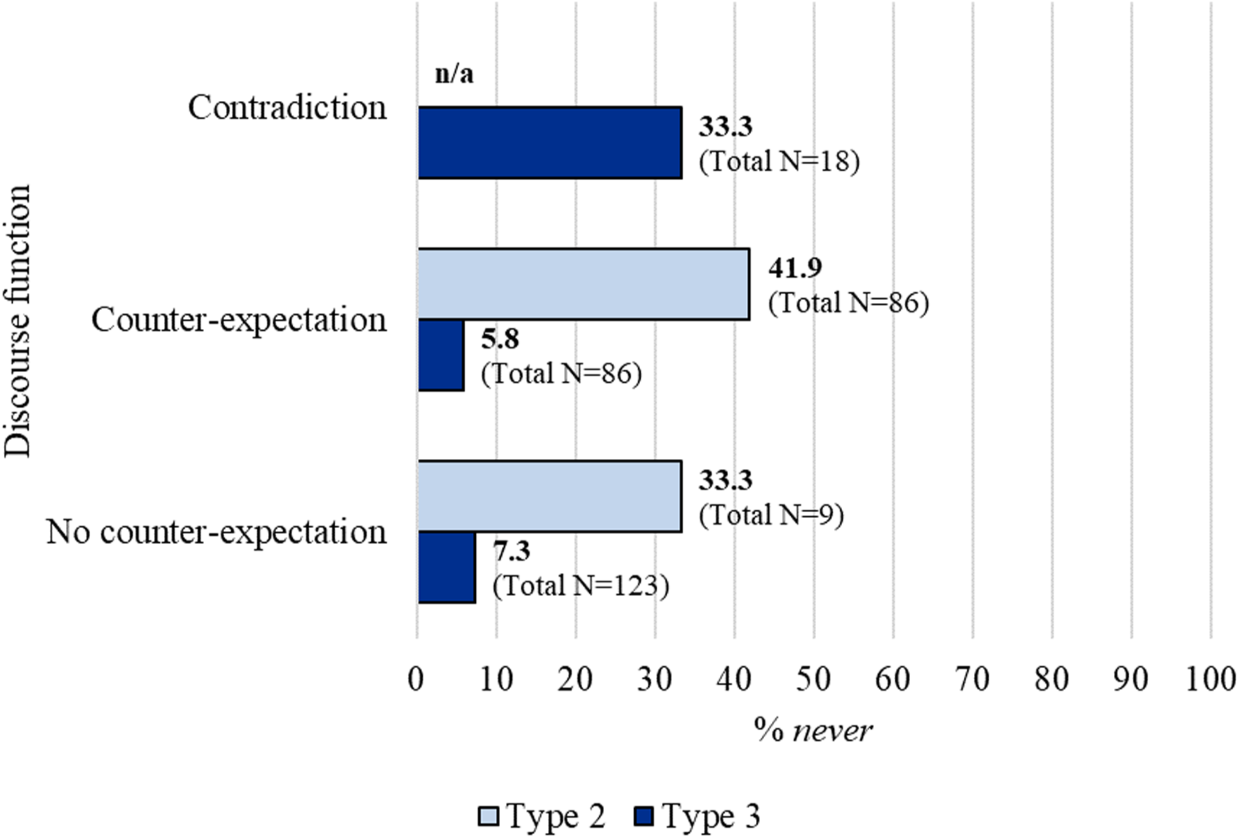

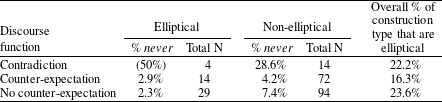

The hypothesis outlined in Section 6.2 was that contradictions (the explicit contradiction of a speaker’s previous overt assertion that a proposition, p, was true) and counter-expectations (negation where the expectation of a speaker/hearer/subject/society was that p would be true) would exhibit higher relative frequencies of never than in no-counter-expectation expressions, i.e. where there was no previous expectation of the truth/falsity of the proposition or the expectation was met. Figure 6 shows the frequency of never for these discourse functions in Type 2 and Type 3 contexts, with ‘Total N’ representing the total number of tokens for the variable in each category.

Figure 6 Distribution of never (vs. didn’t) in Type 2 and Type 3 contexts according to discourse function.

Considering Type 2 first, Figure 6 shows that never is used at higher relative frequencies in pragmatically-marked contexts where the speaker poses a contrast between what was expected and what actually happened, as it is used more frequently to express counter-expectation (41.9%) than no counter expectation (33.3%). Given this, we might predict a similarly high rate of never in Type 2 contradictions, since they too pose a contrast (between a previously-stated proposition and an explicit rejection of that proposition). However, there are no instances of Type 2 contradictions at all, for either variant; furthermore, the distribution for Type 2 never is not statistically significant. This finding, along with the low number of Type 2 no-counter-expectation tokens (N = 9) compared to the Type 3 equivalent (N = 123), indicate that Type 2 contexts as a whole are associated with counter-expectation, rather than the use of the never variant specifically. Indeed, counter-expectation constitutes 90.5% of all Type 2 tokens. Type 3 contexts, on the other hand, are not associated with one particular function. The never variant is, however, most likely to feature in contradictions (33.3%) and only marginally in counter-expectations (5.8%) or where there is no counter-expectation (7.3%), in a statistically significant distribution (Fisher’s Exact Test, p < .01). Table 6 shows that these effects are consistent across the communities, at least as far as can be seen with datasets of this size: (i) counter-expectation is a core characteristic of the Type 2 context regardless of variant; (ii) Type 3 never is used more frequently in contradictions than for other functions (where there is sufficient data for this to be examined – parentheses indicate where token numbers for a cell are between five and 10); and (iii) there is little differentiation between the counter-expectation and no-counter-expectation categories in terms of the frequency of Type 3 never.

Table 6 Distribution of never (vs. didn’t) in Type 2 and Type 3 contexts according to discourse function, per locality. The numbers in shaded cells indicate the percentages based on at least 10 tokens. Percentages in parentheses are based on fewer than 10 tokens.

The Glasgow data in Table 6 shows that never is the majority variant for Type 2 counter-expectations and Type 3 contradictions, which are the most emphatic functions. This suggests that Miller’s (Reference Miller1993: 115) statement that never is not emphatic in Scottish English was not necessarily alluding to the potential pragmatic import of Type 3 never but was instead drawing a contrast between never in Type 1 contexts (a standard usage that could potentially be considered more emphatic in that it quantifies over time) versus Type 3 contexts. What these findings in Table 6 might suggest is that never is actually further towards becoming an unemphatic negator in Glasgow than in the other varieties. If an emphatic negative marker comes to be used by speakers in pragmatic contexts where there is not ‘a high degree of counter-expectation on the part of the listener’, this can lead to a new, expressive, routine of speaking, causing the frequency of the marker to increase (Detges & Waltereit Reference Detges and Waltereit2002: 183). This ‘overuse’ of emphatic negation gradually leads to a loss of its emphatic quality (Detges & Waltereit Reference Detges and Waltereit2002: 185). The fact that never is used at the highest relative frequencies in Glasgow, particularly in contexts where there was no counter-expectation, reflects its place further along the trajectory towards becoming a simple negator, as the next step in Jespersen’s Cycle (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1917; see also Cheshire Reference Cheshire, Cheshire and Stein1997, Reference Cheshire, Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1998).

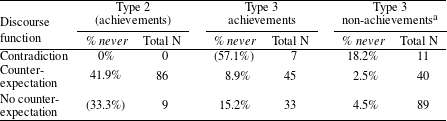

The results in this section thus far suggest that in the diachronic process of expanding from Type 2 into Type 3 uses, never changed its discourse–pragmatic function. Is this simply an artefact of the properties of achievement predicates vs. other predicate types? To address this question, Table 7 compares how often never is used for each of these three functions in Type 2 contexts (necessarily achievements), Type 3 achievements and Type 3 non-achievements.

Table 7 Distribution of never (vs. didn’t) in Type 2 (achievements), Type 3 achievements and Type 3 non-achievements according to discourse function.

a There is one fewer token of the Type 3 counter-expectation and Type 3 no-counter-expectation categories than the previous analyses in Section 7.3 because these tokens were ambiguous in terms of lexical aspect.

Table 7 reveals a parallel between Type 3 achievements vs. non-achievements in terms of never’s distribution, in contrast to the Type 2 contexts. For both sets of Type 3 environments, the ranking of functions (from the most to least likely to feature never) is the same: contradiction > no counter-expectation > counter-expectation. Type 2 and Type 3 achievements do not pattern alike, so we can conclude that the functional differences are not an epiphenomenon of predicate type, but that never has undergone specialisation as it has grammaticalised (see Hopper Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991: 25), namely developing a functional niche in Type 3 contexts not found in Type 2 contexts: contradiction of previous propositions. This functional innovation may have arisen through reanalysis (Brinton & Traugott Reference Brinton and Traugott2005: 110; Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2010a: 39), whereby never was first associated with the counter-expectation meaning so central to Type 2 constructions, but became reinterpreted as expressing contradiction when used non-standardly in Type 3 contexts.

This development likely arose due to similarities between counter-expectations and contradictions. Both mark disclaim (Martin & White Reference Martin and White2005: 118) and are reminiscent of the ‘emphatic’ function often ascribed to non-quantificational never (Beal Reference Beal1993: 198; Hickey Reference Hickey and Hickey2004: 524; Beal & Corrigan Reference Beal, Corrigan and Iyeiri2005: 145; Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 460; Buchstaller & Corrigan Reference Buchstaller, Corrigan and Hickey2015: 80).Footnote [17] The contradiction is a stronger, potentially more face-threatening act since it concerns explicit denials of explicit propositions, as opposed to the denial of an implicit assumption. The innovation of non-standard never therefore appears to be a pragmatically-motivated change whereby the form first appears in ‘the most salient, most monitored, marked environment, from which it may spread, as it loses its novelty, to less salient, unmarked environments’ (Andersen Reference Andersen and Andersen2001: 34). This trajectory can also explain why never rarely expresses counter-expectation in Type 3 contexts even though counter-expectation is characteristic of Type 2 constructions.

A final consideration in this section is whether there is any interaction between the discourse function of never and VP-ellipsis, as shown in Table 8, given reports that never in elliptical constructions may be used for contradiction (Cheshire Reference Cheshire1982: 68; Coupland Reference Coupland1988: 35) or emphasis (Cheshire Reference Cheshire1982: 68; Beal Reference Beal and Jones1997: 372). Standard English requires did not/didn’t in these cases, so the never tokens considered here are all non-standard, Type 3 uses (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 471).

Table 8 Distribution of Type 3 never (vs. didn’t) according to ellipsis and discourse function. Percentage in parentheses is based on fewer than 10 tokens.

Never is more frequently chosen over didn’t in elliptical contradictions than non-elliptical contradictions (50% vs. 28.6%), as Cheshire (Reference Cheshire1982: 68) also found in Reading English. Table 8 shows little difference in the frequency of never between elliptical and non-elliptical constructions for the other two functions. While one must remain cautious given the low number of tokens for elliptical contradictions, these results are consistent with Cheshire’s (Reference Cheshire1982: 68) observation that never ‘occurs alone [i.e. in elliptical constructions] mainly in arguments, to contradict what has been said before’, i.e. contradictions. Speakers are therefore more likely to use the most marked variant, non-standard never, in the most marked linguistic context (i.e. clause-final position), for the most marked function – contradiction. The fact that this type of construction was the least accepted of all sentences containing never in Cheshire’s (Reference Cheshire, Cheshire and Stein1997) survey reflects that it is a particularly marked usage. This tallies with the characterisation of the non-standard use of never as the result of a pragmatically-motivated change in which we will expect the form to gradually expand into less marked contexts (Andersen Reference Andersen and Andersen2001: 34) and eventually become an unemphatic negator (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1917; Cheshire Reference Cheshire, Cheshire and Stein1997, 1998).

7.4 Speaker sex and age

Social trends are considered in case these provide further insight into the nature of linguistic changes in the use of never. Comparing the distribution of never between the sexes proved not to be significant, for either Type 2 or Type 3 uses, in any community.Footnote [18] Similarly, the differences in the frequency of never (both types) according to age within each community were not significant. Therefore, the results for sex and age do not satisfactorily support the conclusion that non-quantificational never is ‘spreading’ in Scottish varieties (Miller & Brown Reference Miller and Brown1982: 15) and potentially other dialects of English (Beal Reference Beal and Jones1997: 32). However, changes in the use of never are certainly observable in diachronic data (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012) and the synchronic data presented in this paper, so it appears that either the change does not have any particular social correlates or else a larger dataset with a wider timeframe could potentially uncover social trends.

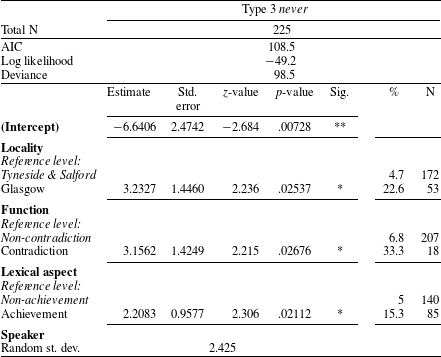

7.5 Regression analysis

The distributional analysis has shown that the variation between non-quantificational never and didn’t is affected by locality, lexical aspect and discourse function. The analysis proceeds with a mixed-effects logistic regression using the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (R Core Team 2014) to ascertain the relative impact of these factors. The Type 2 tokens cannot feature in such a model because they are not sufficiently frequent (N = 97), so the analysis will concern the Type 3 tokens (N = 225).

Some re-categorisation of the data was required because certain groups had little variation and thus could not be included in the model (Guy Reference Guy and Preston1993: 239). Firstly, in relation to locality, Tyneside and Salford had low frequencies (< 5%) of Type 3 never (as seen in Section 7.1 above). Groups with such little variation can be excluded from the model (see Guy Reference Guy, Ferrara, Brown, Walters and Baugh1988: 132), but this would prevent the consideration of locality as a factor conditioning the variation, which could be a crucial predictor. For these reasons, the tokens from Tyneside and Salford were combined into a single group, allowing for comparison between Northern English and Glaswegian English – a decision preferable to not considering locality at all. Secondly, the distributional analysis in Section 7 revealed that the relative frequency of never in Type 3 contexts was almost the same for counter-expectation and no-counter-expectation functions (5.8% and 7.3% respectively). As both of these functions are less pragmatically marked than contradictions (recall Section 6.2 above), the model includes a binary distinction between ‘non-contradictions’ (combining the counter-expectation and no-counter-expectation categories) and ‘contradictions’. Thirdly, in relation to lexical aspect, the stative category had a low relative frequency of never in Type 3 contexts (3.8%). Excluding statives from the model would reduce the total number of tokens by almost half (N = 106), which is far from desirable. Instead, a binary variable comprising ‘non-achievements’ (including stative, activity and accomplishment predicates) and ‘achievements’ is employed, which will allow me to test the hypothesis that never in Type 3 contexts is favoured in achievements due to persistence of the aspectual constraints on Type 2 uses.

Ideally, one would not need to collapse groups to form binary variables, but these decisions maintain meaningful distinctions for hypothesis-testing while retaining the largest possible number of tokens overall, as well as per group and per level – only 10 were lost from the original total of 235. Even though more complex models may have the potential to explain more of the variation, a simple, more reliable model is preferable here given the relatively small dataset.

Table 9 shows the results of the mixed-effects logistic regression to investigate the significance of locality, function and lexical aspect in the variation between Type 3 never and didn’t. ‘Speaker’ is included as a random effect to account for inter-speaker variation. The fixed factors all contribute significantly to the variation, corroborating the earlier distributional analyses.

Table 9 Mixed-effects logistic regression of the combined effect of factors in the use of Type 3 never (vs. didn’t).

* = p < .05; ** = p < .01

Locality has the largest estimate value and the results show that although non-quantificational never is a feature of many English dialects, its frequency differs significantly between the varieties in Table 9. Speakers in Glasgow are significantly more likely to use never than those in Tyneside and Salford in Northern England. The significantly high frequency of Type 3 never in Glasgow is in line with previous reports that this feature is characteristic of Scottish varieties of English (Miller & Brown Reference Miller and Brown1982: 15; Miller Reference Miller1993: 115; Reference Miller, Kortmann and Upton2008: 303).

Function has the next largest estimate value, with never favoured for contradictions more than non-contradictions. Never is therefore favoured in specific pragmatically-marked contexts, namely contradictions, which express contrast between two explicit, opposing propositions.

The results for the final fixed factor, lexical aspect, show that never is favoured in achievement predicates over non-achievement predicates. This finding is consistent with Lucas & Willis’ (Reference Lucas and Willis2012) account of the historical trajectory of never, in which its use as a standard variant in Type 2 ‘window of opportunity’ environments (categorically achievement predicates) was followed by its subsequent expansion into Type 3 contexts (of various predicate types), where it is non-standard. Never’s restriction to achievement predicates in Type 2 environments therefore persists as a probabilistic constraint on its Type 3 distribution.

8 Conclusion

Although never originated as a universal quantifier over time (Type 1) in Old English, the form subsequently developed new functions including – in the Early Modern and Late Modern English periods – non-quantificational uses equivalent to didn’t which are still used in present-day English (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012). This paper focused on the variation between non-quantificational never and didn’t in two separate contexts as described in Lucas & Willis (Reference Lucas and Willis2012): (i) Type 2 ‘window of opportunity’ contexts, comprising achievement predicates in the preterite where there is a specific temporal window in which an event could have occurred but did not (e.g. she never got my message); and (ii) Type 3 contexts, comprising various predicate types in the preterite where there is no ‘window of opportunity’ but never still has non-quantificational meaning (e.g. I never had that coat). Never in Type 2 contexts is found in Standard English, but the form subsequently developed a Type 3 use where it is non-standard (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012).

The paper presented a quantitative analysis of the variation between never and didn’t in Type 2 and Type 3 contexts across three varieties of English spoken in Glasgow, Tyneside and Salford, UK. This was a novel approach in that previous work on never has been predominantly qualitative (Cheshire Reference Cheshire1985, Reference Cheshire, Cheshire and Stein1997, Reference Cheshire, Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1998; Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Edwards and Whittle1989; Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012) or quantitative but without comparing the Type 2 and Type 3 uses (Cheshire Reference Cheshire1982), and these studies have not investigated its use across different dialects of English. Analysing the variation as a single variable (never vs. didn’t) with two variable contexts captures the idea that the speaker has a choice between these two variants to express non-quantificational negation in the preterite, but that their choice is subject to different linguistic constraints in Type 2 and Type 3 contexts (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012), as well as the fact that never is standard in the former but non-standard in the latter.

This approach allowed me to test hypotheses that the distribution of never as a non-quantificational negator in ‘window of opportunity’ achievement predicates (Type 2) would impact upon never’s distribution in the predicates in which it is non-standard (Type 3), as a form of persistence as it grammaticalises (Hopper 1991). The results showed that non-standard uses of never (Type 3) are constrained by lexical aspect, being used most often in achievement predicates – the precise environment in which Type 2 never inherently occurs. Type 3 never was also more likely to be used with bounded dynamic events (achievements and accomplishments) rather than unbounded events (activities) or statives, reflecting its status as a punctual negator. Furthermore, the frequency of never in Type 3 achievements in each locale was remarkably similar to the localities’ respective overall rates of never in Type 2 (achievement) contexts, suggesting that the non-standardness of never becomes less salient in predicates of this type where both standard and non-standard uses of never can occur.

The investigation also tested qualitative reports that non-quantificational never can be emphatic (Beal Reference Beal1993: 198; Hickey Reference Hickey and Hickey2004: 524; Beal & Corrigan Reference Beal, Corrigan and Iyeiri2005: 145; Buchstaller & Corrigan Reference Buchstaller, Corrigan and Hickey2015: 80) or contradict propositions, either explicit (Cheshire Reference Cheshire1982: 68; Coupland Reference Coupland1988: 35) or implicit (Lucas & Willis Reference Lucas and Willis2012: 460). Analysing the distribution of variants according to whether they expressed ‘contradiction’, ‘counter-expectation’ or ‘no-counter-expectation’ revealed key differences in never’s discourse–pragmatic function in Type 2 vs. Type 3 contexts. Type 2 predicates tended to express counter-expectation regardless of the variant, but never was especially likely to be used in such contexts. In Type 3 constructions, never was most frequently used over didn’t in contradictions (a non-existent function among the Type 2 tokens of either variant) and rarely for other functions. If contradictions had an elided VP, never was even more likely to appear, in keeping with Cheshire’s (Reference Cheshire1982: 68) observations that these constructions were most common in interactions where one speaker contradicts another. More linguistically-marked contexts (ellipsis of the VP) and more pragmatically-marked contexts (contradiction of previous speaker’s proposition) therefore yield the highest rates of non-standard never. Overall, the function of never appears to have been reanalysed from denoting mainly counter-expectation in Type 2 contexts to develop a stronger expression of denial – a contradiction – when it came to be used non-standardly in a wider range of contexts (Type 3), as an example of pragmatically-motivated specialisation (see Andersen Reference Andersen and Andersen2001: 34). If Type 3 never gains traction in contexts where there is no such counter-expectation or contradiction, it may eventually become an unemphatic negative marker as predicted by Jespersen’s Cycle (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1917; see also Cheshire Reference Cheshire, Cheshire and Stein1997, Reference Cheshire, Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1998; Detges & Waltereit Reference Detges and Waltereit2002).

Given reports that non-quantificational never is a feature of Englishes around the world (Kortmann & Szmrecsanyi Reference Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi2004; Britain Reference Britain and Kirkpatrick2010; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2013: 29), one might not anticipate substantial differences in its frequency across British communities. However, locality was a significant factor in the use of non-quantificational never. In the mixed-effects logistic regression of Type 3 never vs. didn’t, Glasgow speakers favoured the use of never more than those in Northern England (Tyneside and Salford). Not only does this result support associations between Scotland and higher frequencies of non-quantificational never (Miller & Brown Reference Miller and Brown1982: 15; Miller Reference Miller1993: 115; Reference Miller, Kortmann and Upton2008: 303), but it demonstrates that even the most ubiquitous linguistic features can exhibit localised patterns.

Overall, this research has emphasised how ‘later constraints on structure or meaning can only be understood in the light of earlier meanings’ (Hopper & Traugott Reference Hopper and Traugott2003: 96). The grammaticalisation of never poses many challenges for quantitative variationist analysis, given that it involves a single form that: (i) has developed new meanings and contexts of use over time, as it has grammaticalised; (ii) varies with another form, didn’t, only in a subset of these contexts; (iii) is standard in some of these contexts and non-standard in others; and (iv) has maintained all of these uses diachronically such that all of them are used today. This study has demonstrated that integrating syntactic theory and variationist methodology offers a fruitful approach for the analysis of morpho-syntactic variation and change, particularly with respect to understudied and/or complex linguistic phenomena. Careful consideration of the linguistic properties of the various uses of never and a systematic coding procedure has therefore enabled us to see how the linguistic distribution of never in English dialects in the present day reflects historical persistence of semantic and syntactic constraints, but also a pragmatically-motivated change in which non-standard (Type 3) never is initially associated with the most marked contexts but, we predict, will eventually become an unemphatic negative marker.