1. Introduction

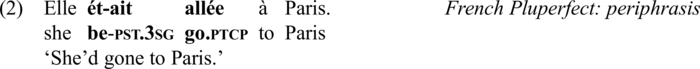

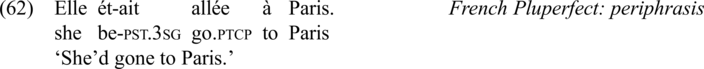

Many languages have a contrast between synthetic and periphrastic verbal constructions. For instance, in French, the Imperfect is synthetic, and the Pluperfect is periphrastic:Footnote 1

Periphrastic verbal constructions such as the Plurperfect in French and other languages have been argued to involve a default/expletive verb (normally, be) (Bach Reference Bach1967, Schütze Reference Schütze2003, Cowper Reference Cowper2010, Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2011), and thus, we refer to this type of periphrasis as default periphrasis (Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2011). We give a more precise characterization of default periphrasis in Section 2. In this paper, we investigate the relation between this type of periphrasis and head movement.

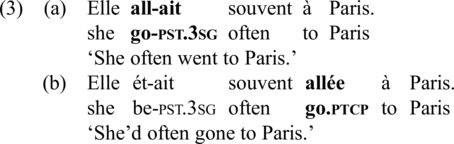

In many languages in which the lexical verb moves to T in simple tenses, this movement is impossible in periphrastic tenses. This has been observed in French and many other languages:

In the synthetic tense in (3a), the lexical verb moves to T, as diagnosed by its placement to the left of the adverb souvent demarcating the left edge of the VP (Emonds Reference Emonds1978, Pollock Reference Pollock1989). In the periphrastic tense in (3b), the same diagnostic tells us that the lexical verb has not moved to T.Footnote 2

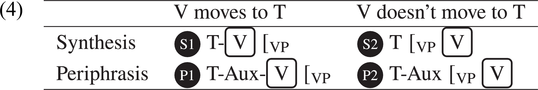

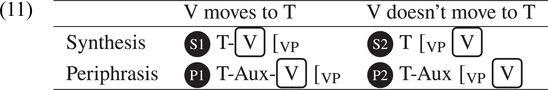

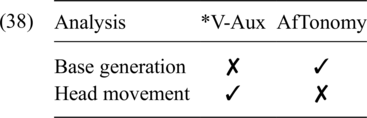

The French constructions above instantiate two out of four possible ways in which head movement could in principle interact with the presence/absence of an auxiliary. The following table represents the four options (the table assumes that T and Aux form a complex head):

The option French adopts for synthesis is S1 (synthesis of type 1), in which the lexical verb moves to T. One of the questions we ask here is whether S2 exists – that is, whether there are cases in synthesis in which the lexical verb and T do not form a complex head via head movement. We show in Section 4 that S2 indeed exists and is attested in Swahili (we also discuss in that section why English is not a perfect example of this pattern). Even though T is affixed to the lexical verb in both Swahili and French, the verb moves to T only in French. This difference between the two languages argues for a dissociation between the affixal nature of T from its being in a head movement with a verb. We refer to this dissociation as AfTonomy (for Affixal T Autonomy). As for periphrasis, French chooses option P2, in which the lexical verb does not move to T. Thus, a similar question arises as to the availability of P1 – that is, a periphrastic construction in which the lexical verb moves to T. Our claim is that such constructions are not attested. As explained in Section 3, we view this gap as a ban on head movement of the lexical verb to the auxiliary, what we call *V-Aux. Footnote 3

In Section 5, we argue that existing approaches to periphrasis derive one or the other generalization, but not both. In the traditional base-generation approach, the auxiliary verb is generated as the head of its own projection, which is present in periphrasis, but absent in synthesis. Since head movement is orthogonal to the presence of this projection, this approach derives AfTonomy because nothing requires movement of the lexical verb to T in either case. But precisely for the same reason, this approach cannot account for *V-Aux since nothing precludes head movement of the lexical verb to the auxiliary. A different family of approaches builds on the idea that T is an inflectional head requiring a verbal host, and the lexical verb and the auxiliary compete to provide one. This competition derives *V-Aux in a way we make precise in Sections 5.2–5.3. However, this approach does not derive AfTonomy: Since periphrasis arises whenever the lexical verb does not move to T, the approach predicts that in synthesis, this head movement necessarily occurs.

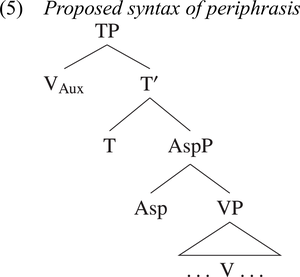

In Section 6, we argue that *V-Aux and AfTonomy can be explained by the combination of two hypotheses proposed in previous literature. The first is that head movement is parasitic on selection (Svenonius Reference Svenonius1994, Matushansky Reference Matushansky2006, Preminger Reference Preminger2019). The second is that auxiliaries are merged as specifiers selected by functional heads such as T (Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2017: 83–157; 2023):Footnote 4

This analysis entails that there is no selectional relation between the auxiliary and the lexical verb, which precludes the possibility of relating them by head movement, deriving *V-Aux. This analysis also accounts for AfTonomy, as it does not posit a direct link between synthesis/periphrasis and head movement. Instead, the relevant relation is selection: In synthesis, T’s V-selectional requirement is satisfied by the lexical verb, and in periphrasis, by the auxiliary. But, since selection does not entail head movement, this requirement is met irrespective of whether head movement takes place or not.

2. Defining default periphrasis

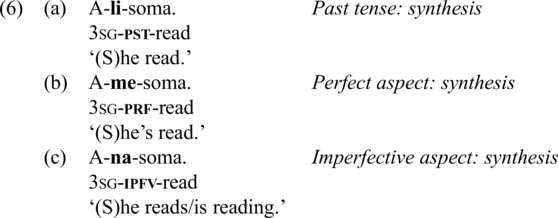

Default periphrasis can be characterized as arising due to increased inflectional complexity in clause structure, having to do with tense, aspect and voice. This increased complexity results in the use of the default/expletive verb be (sometimes have; see below) (Bach Reference Bach1967, Schütze Reference Schütze2003, Cowper Reference Cowper2010, Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2011, Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2017, Fenger Reference Fenger2020). In many languages, the sensitivity of the auxiliary be to inflectional complexity can be observed directly, as they display the so-called overflow pattern of auxiliary use (Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2011). We illustrate this pattern by the interaction of past tense, perfect aspect and imperfective aspect inflections in Swahili. Each of these infections on its own combines with the lexical verb in a synthetic way – that is, without an auxiliary:

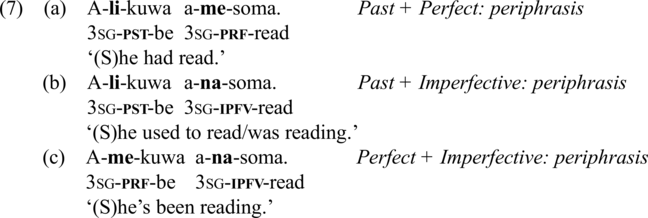

The combination of any two of these inflections requires an auxiliary be, which supports the realization of the higher of the two inflections (7).

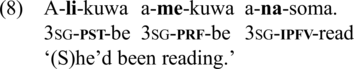

As expected, combining all three inflections requires two occurrences of be:

The overflow pattern shows that the presence of the auxiliary cannot be linked to any particular inflection (6) but rather is required by increased inflectional complexity (7–8).

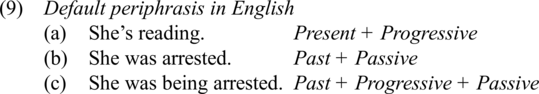

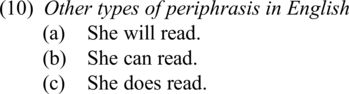

In some languages – for example, English – default periphrasis follows a different, additive, pattern (Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2011), in which the presence of the auxiliary be can be predicted by the presence of a specific inflection (e.g. passive voice in English). Bjorkman and others (Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2017, Fenger Reference Fenger2020) have argued that the additive pattern derives from the same underlying mechanism as the overflow pattern – they are both types of default periphrasis. The difference between the two is that in the overflow pattern, some inflections (e.g. present tense in Swahili) are unmarked and do not contribute to inflectional complexity. Thus, English, French and Swahili all have default periphrasis, derivable in a uniform way, and differing in the surface pattern (overflow vs. additive). Our goal here is to develop a theory of default periphrasis in general – that is, periphrastic constructions with the auxiliary be that arise due to inflectional complexity in the tense-aspect-voice domain. We do not offer new insights into the additive vs. overflow distinction (see footnote 18 for our adaptation of Bjorkman’s account). For clarity, (9) gives examples of default-pheriphrastic constructions in English, while (10) illustrates other types of periphrasis, which do not fall under the scope of this paper.

In some languages, the default auxiliary takes the form have, rather than be, in some contexts. We do not commit to an analysis of this alternation, but we adopt the general view that have is a special allomorph of the default verb (Freeze Reference Freeze1992, Kayne Reference Kayne1993, Cowper Reference Cowper2010, Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2011).

3. *V-Aux

We saw that in French periphrastic constructions, the lexical verb does not move to T (option P2 in (4), repeated in (11)). We argue in this section that the lack of this movement is principled and that P1 in (11) is not available crosslinguistically.

We view this gap as the impossibility of head movement of the lexical verb to the auxiliary, what we call *V-Aux. We discuss the precise nature of this generalization and apparent counterexamples to it.

*V-Aux can be stated as follows:

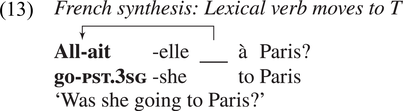

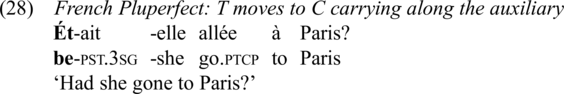

The generalization was illustrated for French in Section 1. In addition to the adverb-placement data shown there, further evidence comes from inversion contexts (in matrix questions), in which the [V-T] complex head moves to C, resulting in inversion of the lexical verb with the subject clitic in synthetic tenses, as in the following example:Footnote 5

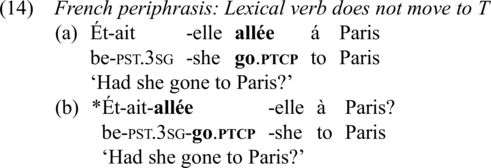

In periphrastic tenses, the auxiliary and T undergo head movement to C stranding the lexical verb (14a). While movement of the auxiliary, rather than the lexical verb, follows from the Head Movement Constraint (Travis Reference Travis1984, Baker Reference Baker1988), nothing in principle prevents the lexical verb and the auxiliary from forming a complex head and moving to C as a unit. In such a case, the auxiliary might take the form of an affix or form a compound with the lexical verb. Nonetheless, the lexical verb and the auxiliary cannot form a complex head that moves to C (14b).Footnote 6

The unacceptability of (14b) shows that *V-Aux holds in French.

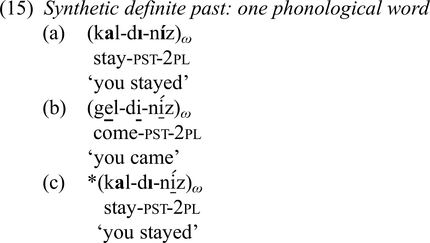

The pattern we observe in French is a common one crosslinguistically, but there are apparent counterexamples. Apparent exceptions to *V-Aux can be observed in languages such as Turkish, in which auxiliaries do seem to form some sort of unit with the lexical verb (Kornfilt Reference Kornfilt1996, Fenger Reference Fenger2019, Reference Fenger2020). Before we illustrate this, let us look at cases that do not look problematic. Turkish has both synthetic (15) and periphrastic (16) constructions. As in other languages, the auxiliary and the lexical verb are independent in the sense that they form separate phonological words, diagnosed by vowel harmony and stress. (We notate back vowels in bold, and front ones are underlined.)

The domain of both vowel harmony and stress is the phonological word. Specifically, all morphemes after the root within this domain harmonize with the root vowel in backness and roundness. In addition, stress within this domain is on the final syllable. According to these diagnostics, a synthetic expression such as those in (15) is a single phonological word, as all morphemes after the root of the lexical verb harmonize with the root vowel, and the final syllable in the verbal expression is stressed. In contrast, a periphrastic expression has two separate phonological words: As shown in (16), only the morphemes preceding the auxiliary harmonize with the root of the lexical verb, and the auxiliary and morphemes following it form a separate harmony domain. Accordingly, stress falls on the last syllable of the domain containing the root of the lexical verb. Auxiliary words are phonologically weak, hence the absence of stress on the final syllable of a periphrastic expression (Kornfilt Reference Kornfilt1996).

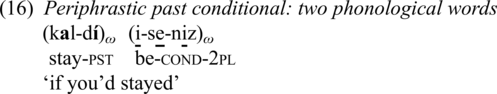

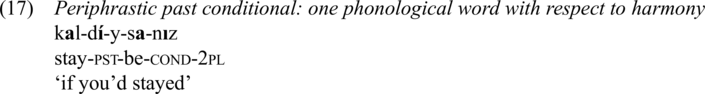

Interestingly, periphrastic tenses such as the past conditional expression in (16) can optionally form a single harmony domain, as shown in the following:

We assume that complex heads created by head movement are mapped to phonological words. If we assumed that this was the only way to generate phonological words, we could conclude that Turkish had optional V-to-Aux movement, which would be a counterexample to *V-Aux. However, the other diagnostic for phonological words – namely, stress – points to a different conclusion. Recall that in (16), the two diagnostics give the same result – namely, that the lexical verb forms a separate domain from the auxiliary with respect to both vowel harmony and stress. This is not the case in (17): While we observe one vowel-harmony domain that includes the lexical verb and the auxiliary, the lexical verb forms a domain of stress that excludes the auxiliary. If the two formed a single stress domain, we would expect the stress to fall on the final syllable of the vowel harmony domain, contrary to fact (cf. *kal-dı-y-sa-níz). This means that if we diagnose phonological words by stress, (17) is not a counterexample to *V-Aux.

Kornfilt Reference Kornfilt1996 and Fenger Reference Fenger2019, Reference Fenger2020 account for this apparent contradiction by proposing that the auxiliary and the lexical verb in (17) are put together not by head movement, but by a different operation that applies optionally. Kornfilt calls it cliticization, while Fenger proposes that it is a late PF operation that applies after Vocabulary Insertion (VI). (The standard assumption is that head movement applies before VI, an assumption that is crucial in Fenger’s analysis and which we adopt as well.) Furthermore, stress and vowel harmony apply at different stages in the derivation: Stress assignment occurs before cliticization, and vowel harmony, after. Fenger implements it in terms of the following order of operations:

Due to the absence of an auxiliary, cliticization does not occur in synthetic tenses, and the domains of stress and vowel harmony are identical. In a periphrastic construction, cliticization, if it applies, makes the domain for vowel harmony larger than the stress domain. This accounts for the misalignment of stress and vowel harmony domains in (17). If there is no cliticization, as in (16), the two domains are aligned. (17) is therefore not a counterexample to *V-Aux since the lexical verb and the auxiliary are not related by head movement. This conclusion is corroborated by syntactic diagnostics such as coordination (Fenger Reference Fenger2020). It is worth noting at this point that, even though we take head movement to be a syntactic operation, our claims are compatible with the view that it is an early PF operation, as proposed in works such as Fenger Reference Fenger2020 or Harizanov & Gribanova Reference Harizanov and Gribanova2019.

Similar observations and analyses have been made for Japanese and Slavic and Bantu languages, in which auxiliaries appear to form some sort of domain with lexical verbs (Borsley & Rivero Reference Borsley and Rivero1994; Migdalski Reference Migdalski2006; Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2018; Fenger Reference Fenger2020: 19–42). The important conclusion for present purposes is that known instances of word formation between a lexical verb and an auxiliary are distinct from head movement. This is manifested by the fact that the lexical verb and auxiliary belong to separate domains for at least some syntactic and phonological processes, contrasting with synthetic expressions. This is exactly what is expected from *V-Aux, which is a ban on relating the lexical verb and the auxiliary by head movement, and says nothing about post-VI building of phonological domains.

4. AfTonomy

The *V-Aux generalizaton discussed in the previous section accounts for the fact that the lexical verb and T are not related by head movement in periphrasis, which rules out option P1 in (11). In synthetic tenses, however, the lexical verb and T are in a head-movement relation in some cases, such as in French synthesis (option S1 in (11)). In this section, we argue that option S2, in which T and the lexical verb are not in a head movement relation in synthesis, is also attested. We propose that the crosslinguistic generalization that accounts for the presence of both S1 and S2 is the following:

This generalization dissociates the affixal nature of a T head from that head being in head movement relation with a verb.Footnote 7 This holds not only for the relation between T and a lexical verb in synthesis, but also between T and an auxiliary verb in periphrasis. We begin by illustrating AfTonomy in synthesis.

An obvious candidate for a language with S2 is English, which has been analyzed as lacking a head-movement relation between the lexical verb and T (i.a. Bobaljik Reference Bobaljik1995, Adger Reference Adger2003, Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2011). However, others have argued that T and the lexical verb in English are in fact related by head movement and that traditional arguments for its absence, such as do-support, are better explained otherwise (Arregi & Pietraszko Reference Arregi and Pietraszko2021). In addition, T in English does trigger head movement of a verb in some constructions: In periphrasis, the auxiliary verb undergoes head movement to T in this language. For these reasons, we do not argue for AfTonomy using English and instead present much clearer evidence for it from Swahili. In this language, T is never in a head-movement relation with a verb, and there are no complicating factors such as do-support.Footnote 8

Like French, Swahili has a synthetic-periphrastic distinction, illustrated here with the Simple Past and the Past Perfect:

Furthermore, *V-Aux holds in this language as well. This is shown by the fact that an adverb can intervene between the auxiliary and the lexical verb in the Past Perfect:

Previous literature has shown that the lexical verb and T in Swahili synthetic constructions such as (20) do not form a complex head (Barrett-Keach Reference Barrett-Keach1986; Ngonyani Reference Ngonyani1999; Buell Reference Buell2002; Henderson Reference Henderson2003; Ngonyani Reference Ngonyani2006; Henderson Reference Henderson2006: 68–166). The first piece of evidence that the lexical verb and T are not in the same complex head comes from stress, which in Swahili falls on the penultimate syllable of the phonological word. In synthetic tenses such as the Simple Past in (20), there are two domains for penultimate stress. One consists of the lexical verb stem (and thus includes the lexical verb root), and the other consists of all inflectional prefixes (including T). Thus, the stress pattern for the verb in (20) is (à-li-)(sóma).Footnote 9

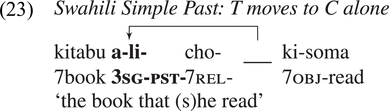

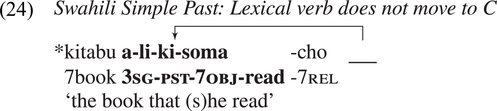

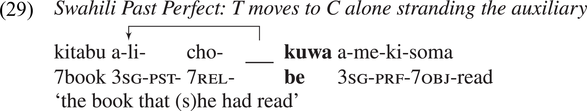

The second argument for the syntactic autonomy of the lexical verb and T in synthetic tenses has to do with inversion in relative clauses. As shown in (23), in a specific type of relative clause, the agreement and tense complex (a-li-) surfaces to the left of the relative C (cho-). Following Kinyalolo Reference Kinyalolo1991, Ngonyani Reference Ngonyani1999, Reference Ngonyani2006, Demuth & Harford Reference Demuth and Harford1999, and Henderson (Reference Henderson2003, Reference Henderson2006: 68–166), we assume this is the result of T-to-C movement.Footnote 10 Importantly, the verb is not carried along and is instead stranded after C.

Given this, we conclude that in Swahili synthetic expressions, the lexical verb does not undergo head movement to T, as observed in the literature cited above. If it did, we would expect the verb to surface before the complementizer, contrary to fact (24).

By comparison, recall that T-to-C movement in French carries the lexical verb along in synthesis, a fact that we interpreted in the previous section as evidence that the lexical verb moves to T in this language.

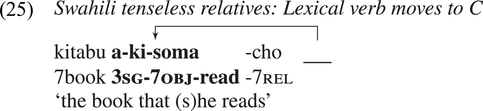

One may be tempted to analyze the contrast in (23–24) in postsyntactic terms; that is, the lexical verb does move to T in synthetic tenses and is thus carried along to C, but is postsyntactically displaced to the right of C. This could be viewed as a nonfinality requirement on the relative complementizer, or a finality requirement on the verb, along the lines of Arregi & Nevins (Reference Arregi and Nevins2012: 237–340; Reference Arregi and Nevins2018). Evidence against this analysis comes from so-called tenseless relatives, in which the verb does precede the relative complementizer (25). In contrast with tensed relatives, such as (23), tenseless relatives have been analyzed as lacking a TP layer and involving V-to-C head movement (Henderson Reference Henderson2003).

Tenseless relatives show that a verb that moves to C is linearized to the left of C. This confirms that in tensed relatives (23), T moves to C alone, stranding the verb. This, in turn, entails that there is no head movement relating the lexical verb and T in Swahili synthetic constructions.

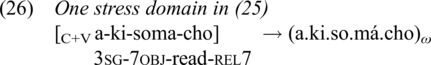

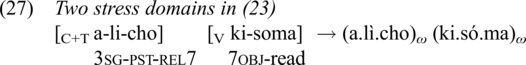

This conclusion is supported by evidence from stress. Recall that stress in Swahili falls on the penultimate syllable of the phonological word. In tenseless relatives, stress falls on the penultimate syllable of the entire verbal expression, showing that it is a single phonological word (26). This is expected under the assumption that complex heads created by head movement map onto phonological words.

In tensed relatives, however, there are two stress domains:

Importantly, the two stress domains align with the complex heads predicted under the claim that the lexical verb does not move to T: The T-C complex head forms one stress domain, and the lexical verb forms the other.

This confirms AfTonomy for synthesis: The lexical verb moves to T in French synthesis, but not in Swahili synthesis. Interestingly, a parallel contrast between the two languages is observed in periphrasis: In French, T is in a head-movement relation with a verb (the auxiliary), but no such head movement occurs in Swahili. Evidence for this comes again from inversion. As we showed in (14a), repeated below, the auxiliary is carried along to C under T-to-C movement in French:

In contrast, Swahili auxiliaries behave just like lexical verbs with respect to inversion, as shown in Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2023: 368–369. The tense-agreement prefix alone inverts with C, leaving the auxiliary behind:

The stress facts confirm this. In (29), the auxiliary forms a separate stress domain from tense inflection and the complementizer: (a.l![]() .cho)

ω (kú.wa)

ω.

.cho)

ω (kú.wa)

ω.

The fact that the contrast between Swahili and French holds in both synthesis and periphrasis suggests that the relevant factor is a property of T, which may or may not require a head-movement relation with a verb, regardless of the identity of the verb (lexical or auxiliary). This is captured by AfTonomy as stated above, and how our analysis derives the contrast between the two languages (see Section 6).

5. Three existing analyses and their shortcomings

In the previous two sections, we argued that the relation between head movement and the synthesis-periphrasis distinction is characterized by the following two generalizations:

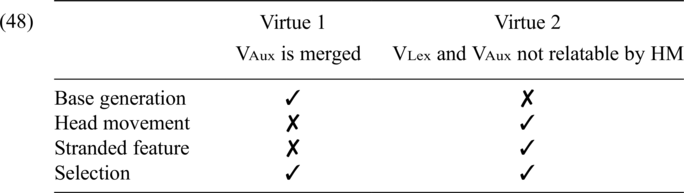

In this section, we discuss three approaches to periphrasis and show that none of them can account for both generalizations, and thus cannot capture the correct relationship between head movement and periphrasis.

5.1. The base-generation approach to periphrasis

In this subsection, we argue that the traditional, base-generation approach to periphrasis derives AfTonomy but fails to account for *V-Aux. Both predictions are due to the fact that the head movement is orthogonal to the formation of periphrastic constructions.

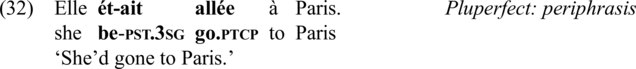

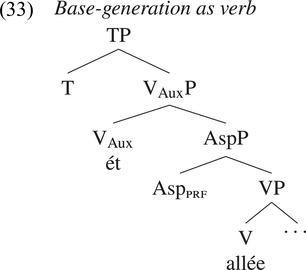

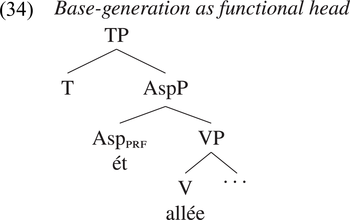

In this approach, an auxiliary is a lexical item that is merged as a verb (i.a. Ross Reference Ross and Todd1969, Déchaine Reference Déchaine, den Dikken and Hengeveld1995, Harwood Reference Harwood2014) or functional head (i.a. Tenny Reference Tenny1987, Adger Reference Adger2003, Cinque Reference Cinque2006) whose complement is a VP (or an extended projection of VP). The structure of the French periphrastic verbal expression in (32) (repeated from (2)) is as in (33–34).

On this approach, the source of the auxiliary is the presence of particular a functional head, here AspPRF, which, by stipulation, is either selected (33) or realized (34) by an auxiliary. In synthesis, the aspectual head, if present, does not have these properties.

This analysis allows, but does not require, head movement of the auxiliary to T. The same holds for synthetic tenses, in which the lexical verb may or may not move to T. This freedom of movement to T is coextensive with AfTonomy, as argued for in Section 4. However, this same freedom should allow the lexical verb to move to the auxiliary, at least in some languages. The absence of this movement crosslinguistically (Section 3) is accidental on this account. For this reason, this analysis does not derive *V-Aux.

5.2. The head-movement approach to periphrasis

In this subsection, we discuss the head-movement approach to periphrasis and argue that it makes the opposite predictions to the base-generation approach: It derives *V-Aux but not AfTonomy. The signature property of this approach is the requirement that T form a complex head with a verb. This requirement is satisfied either by movement of the lexical verb to T (synthesis) or by inserting an auxiliary verb directly in T (periphrasis). *V-Aux is derived because an auxiliary is inserted only when the lexical verb cannot move to T. For this reason, the lexical verb and the auxiliary can never end up in the same complex head. However, synthesis requires head movement of the lexical verb to T (otherwise, auxiliary insertion would occur), which directly contradicts AfTonomy.

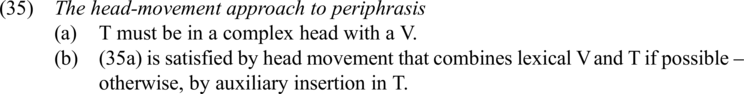

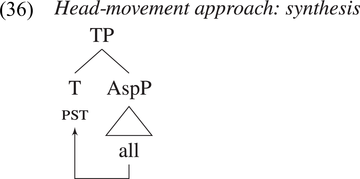

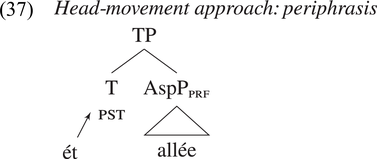

Under the head-movement analysis, the auxiliary verb is not the realization of any verbal or functional head initially merged in the clausal spine. Instead, the auxiliary is a dummy verb inserted in T only in cases when the lexical verb does not move to T, which is possible only in synthetic constructions (Laka Reference Laka1990: 18–25; Arregi Reference Arregi2000; Embick Reference Embick2000; Schütze Reference Schütze2003; Kornfeld Reference Kornfeld2004: 95–129; Saab Reference Saab2008: 200–221, Fenger Reference Fenger2019, Reference Fenger2020; Calabrese Reference Calabrese2019; Cruschina & Calabrese Reference Cruschina, Calabrese, Hinzelin, Pomino and Remberger2021). The basic idea is that T cannot be stranded, which is normally implemented as a constraint, such as (35a).

For instance, in the synthetic Imperfect in French (1), (35a) is satisfied by head movement of the lexical verb to T (36). This movement does not take place in the Pluperfect, triggering insertion of an auxiliary verb in T (37).

The reason the lexical verb does not move to T in a periphrastic tense such as the Pluperfect is that a functional head (here AspPRF) intervenes between T and V, blocking head movement. An important stipulation of this analysis is that whereas AspPRF blocks V-to-T head movement, other Asp heads do not.Footnote 11

This derives *V-Aux as follows. Under this account, an auxiliary is only ever inserted in a stranded T – that is, a T that is not already in a complex head with a verb. This logically precludes the cooccurrence of an auxiliary and a lexical verb in the same complex head. However, this account is incompatible with AfTonomy. In synthesis, the lexical verb necessarily moves to T (otherwise, an auxiliary would be inserted in T, producing periphrasis), and in periphrasis, the auxiliary is inserted directly in T. Therefore, neither the verb in synthesis nor the auxiliary in periphrasis should be strandable in Swahili, contrary to fact (see (23) and (29)).

In sum, while the head-movement approach can derive *V-Aux, it is incompatible with AfTonomy. The base-generation approach faces the opposite problem:

In the next subsection, we consider a third existing type of approach and argue that it faces the same problems as the head-movement approach.

5.3. The stranded-feature approach to periphrasis

The head-movement approach discussed in the previous subsection can be described as involving insertion of an auxiliary verb in a stranded head – namely, a head that is not already in a complex head with the lexical verb. A similar approach based on a featural relation has been proposed in Cowper Reference Cowper2010 and Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2011 – in those accounts, what ends up stranded is a feature of a functional head, not the head itself. The repair strategy is the same as in the head-movement approach – namely, auxiliary insertion in the head that carries that stranded feature. In this subsection, we discuss Bjorkman’s implementation of this approach and argue that, because of its similarities with the head-movement approach, it also derives *V-Aux but fails to derive AfTonomy in either synthesis or periphrasis.

Following Adger Reference Adger2003, Bjorkman (Reference Bjorkman2011) assumes that some functional heads have a valued [iinfl] feature. For instance, a past tense T has [iinfl:pst]. Lexical verbs, however, have an unvalued [uinfl: __] counterpart of this feature. In a synthetic construction such as (39), the [uinfl: __] on V enters into an upward Agree relation with [iinfl] in T:

Notably, this account of synthesis does not necessitate a head-movement relation between T and the lexical verb and therefore may be understood as deriving AfTonomy. However, other details of the analysis crucially make it impossible to account for the facts that support AfTonomy, as explained below.

In Bjorkman’s theory, while [iinfl] features may be relevant for semantic interpretation, [uinfl] plays a pivotal morphosyntactic role: (i) it is the feature exponed by tense inflection, and (ii) it is the feature that must be in a (complex) head with a verb – that is, it is the feature that cannot be stranded. As shown in (40), [uinfl] in V is the only such feature present in a synthetic construction, so the requirement that it occur in the same head as a verb is met. Importantly, this [uinfl] in V is what is realized as tense inflection in (39). Consequently, tense inflection and the lexical verb are necessarily located in the same head on this analysis. This makes it impossible to account for the Swahili inversion facts, which, as discussed in Section 4, demonstrate that tense inflection is syntactically independent of any verb. For this reason, the stranded-feature approach fails to derive AfTonomy, in the sense that it cannot account for the facts that support it. As discussed below, this approach also fails to derive AfTonomy in periphrasis.

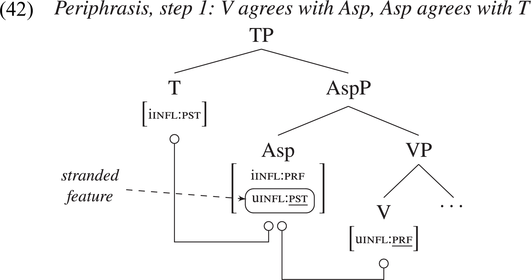

Even though this approach fails to derive AfTonomy, it does derive *V-Aux. Just like the other approaches reviewed in this section, the stranded-feature approach makes a stipulation specific to perfect aspect that plays a role in deriving periphrasis in this aspect. Specifically, Bjorkman proposes that AspPRF has its own [infl] features. As shown above, the Asp head present in synthetic tenses does not have such features. Thus, in the Swahili Past Perfect (41), there are two [uinfl] features (one in V and one in Asp), and each is valued by the head immediately above it (Asp and T, respectively), as shown in (42).

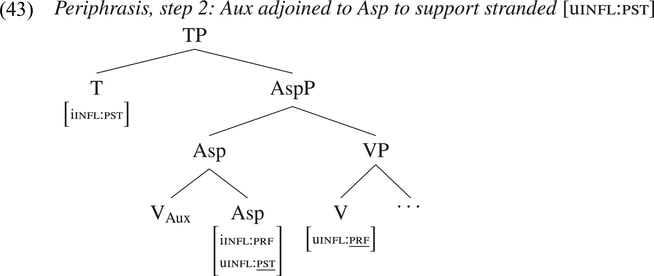

Because of this, [uinfl] in Asp is stranded; that is, it is not in a complex head with a verb. This stranded feature triggers insertion of an auxiliary in Asp to satisfy this requirement:Footnote 12

After auxiliary insertion, tense inflection (i.e. the exponent of [uinfl:pst] in Asp) is in a complex head with a verb. This account derives *V-Aux in a similar way to the head-movement approach: Because the auxiliary is only inserted in a head with a stranded feature – that is, a feature that is not already in a complex head with a verb – the auxiliary cannot logically cooccur in the same complex head as the lexical verb. However, for the same reason, tense inflection is necessarily in the same complex head as the auxiliary. It thus fails to predict AfTonomy in periphrasis, just like it does for synthesis. As we argued in Section 4, tense inflection in Swahili is not in the same complex head as the auxiliary.Footnote 13

5.4. Tacking stock

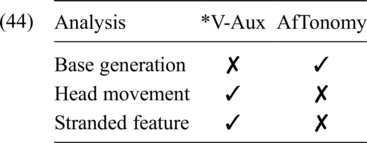

The following table summarizes the predictions made by the three different approaches with respect to *V-Aux and AfTonomy:

Consider the base-generation approach first (45). Since the auxiliary is merged, rather than inserted directly in T, it may, but need not, form a complex head with T, depending on whether head movement applies. This derives AfTonomy. However, the same is true of the relation between the auxiliary and the lexical verb: Nothing prevents head movement of the lexical verb to the auxiliary, which makes this account unable to derive *V-Aux.

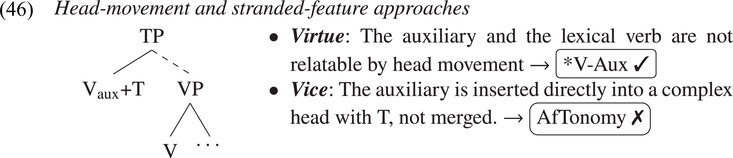

As we showed above, the auxiliary and the lexical verb are not relatable by head movement in the other two approaches (46), allowing them to derive *V-Aux. This advantage is, however, brought about by the requirement that T form a complex head with a verb, which is in turn incompatible with AfTonomy.

In the next section, we argue that there is no necessary connection between the virtue and the vice of each of these approaches. We propose an analysis that maintains the virtues of both types of approaches without inheriting any of their vices.

6. A selection-based theory of the relation between head movement and periphrasis

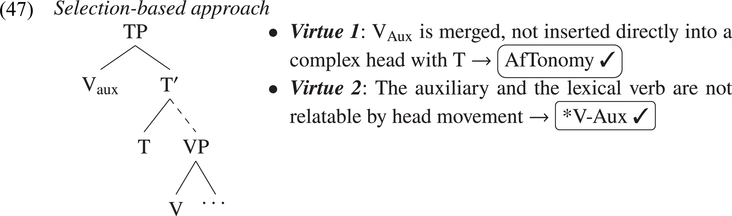

In this section, we argue that *V-Aux and AfTonomy can be derived from two existing claims: i) that auxiliaries are selected by T as specifiers (Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2017, Reference Pietraszko2023) and ii) that head movement is parasitic on a selectional relation (Svenonius Reference Svenonius1994; Julien Reference Julien2002: 52–98; Matushansky Reference Matushansky2006; Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2017; Preminger Reference Preminger2019). The idea to incorporate these two claims into a theory of periphrasis was originally proposed in Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2017. Here, we develop a detailed analysis in this vein and demonstrate how it derives the two generalizations. In brief, since the auxiliary is merged as a specifier of T (47), it need not end up in the same complex head as T (virtue 1), which derives AfTonomy in periphrasis. For the same reason, the auxiliary is not in a selectional relation with the lexical verb, unlike in the base-generation approach. We claim that the absence of this selectional relation is the reason why these two elements are not relatable by head movement (virtue 2), which derives *V-Aux.

The following table compares our analysis with with previous approaches (see (45) and (46)):

We start with the derivation of synthesis first and then turn to periphrasis, focusing on how the generalizations are derived in each construction type.

6.1. Synthesis

In this subsection, we present our analysis of synthesis and show how it derives AfTonomy. We illustrate our analysis with the Simple Past in Swahili and the French Imperfect. Recall that, even though both are synthetic, the lexical verb moves to T in French, but it does not in Swahili. This point of variation is what we refer to as AfTonomy.

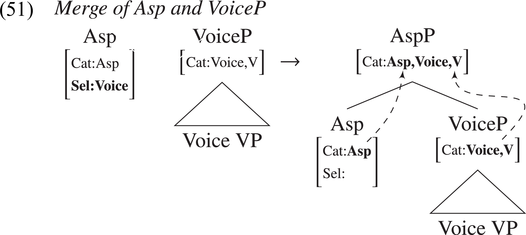

As is standardly assumed, Merge of a head with its complement is licensed by a selectional feature on the head. For the Swahili Simple Past (49), T selects for Asp, Asp for Voice, and Voice for V.Footnote 14 As shown in (50), we formalize selectional feature checking as deletion of the value of a feature with attribute Sel. Furthermore, we build on previous literature proposing that functional projections in the extended projection of the verb are themselves verbal (Abney Reference Abney1987: 54–88; van Riemsdijk Reference van Riemsdijk, Pinkster and Genee1990, Reference van Riemsdijk1998; Grimshaw Reference Grimshaw1991, Reference Grimshaw, Coopmans, Martin and Grimshaw2000). Following Keine Reference Keine2019, we implement this idea by projecting the category of the complement of the functional head as well as its own category. The first few steps of the derivation of a synthetic construction are thus the following:

Following previous work on the synthesis-periphrasis distinction, we adopt the hypothesis that T has a V-selectional requirement (Déchaine Reference Déchaine, den Dikken and Hengeveld1995, Cowper Reference Cowper2010, Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2017). Specifically, we propose that T selects both for the category of the complement and for V, as shown in (52). In synthesis, both selectional requirements are met by the complement of T, due to category projection:

This completes the syntactic derivation of synthetic tenses in languages like Swahili. Importantly, this derivation of synthesis does not necessitate head movement of the lexical verb to T, but it is compatible with this process, as we show below for French.Footnote 15 That is, the analysis accounts for the fact that a head-movement relation between the lexical verb and T in synthesis is optional crosslinguistically; that is, AfTonomy holds.

French synthetic constructions, such as (53), involve head movement of the lexical verb to T.

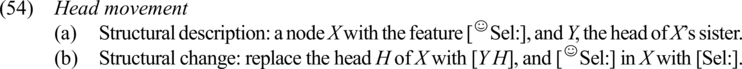

Recall our hypothesis that head movement is parasitic on selection. We implement this as follows: A head that triggers head movement has a selectional feature whose attribute is ☺Sel, instead of simply Sel. For instance, an Asp head that triggers head movement has the selectional feature [☺Sel:Voice]. Specifically, after the value of the selectional feature is checked, the remaining valueless [☺Sel:] is what triggers head movement:

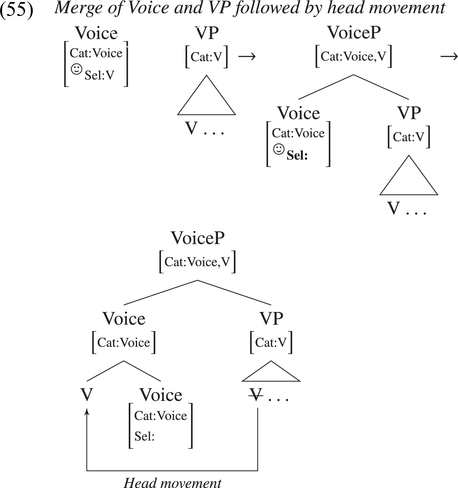

Since in French the lexical verb moves all the way up to T, all functional heads have ☺Sel. We illustrate the effect of ☺Sel with the first part of the derivation involving Voice and VP:

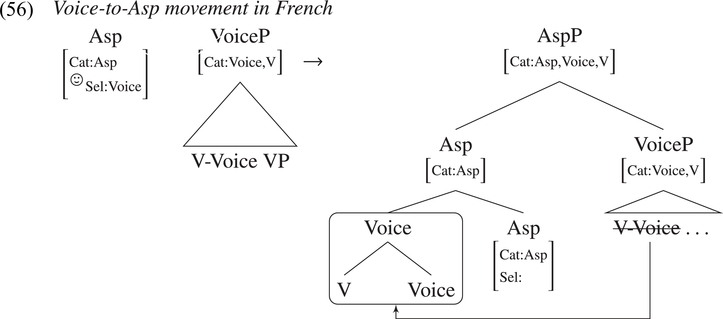

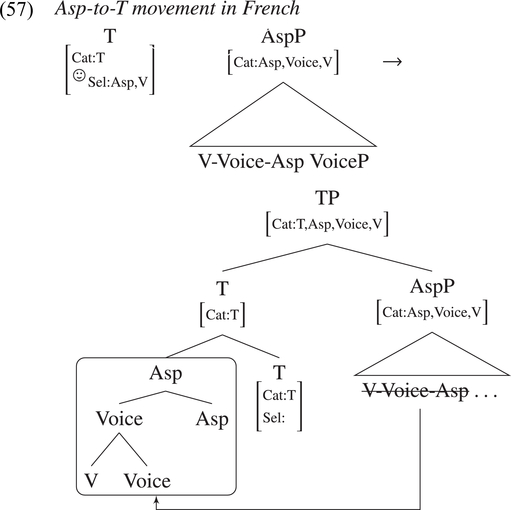

After Merge of Voice and VP, the selectional requirement of Voice is satisfied, leaving a valueless [☺Sel:] that triggers head movement of V to Voice. Further head movement all the way up to T is derived in the same way:

To summarize so far, the analysis derives that synthetic expressions can involve head movement, as in the French Imperfect, but need not, as in the Swahili Simple Past. This analysis, then, derives AfTonomy in synthesis.

6.2. Periphrasis

In this subsection, we present our analysis of periphrasis and show how it derives AfTonomy in periphrasis, as well as *V-Aux. We illustrate our account with the Swahili Past Perfect and the French Pluperfect.

As mentioned above, we claim that T selects for V in addition to the category of its complement. In a synthetic tense, the V-selectional feature of T is satisfied by T’s complement (AspP) because of category projection from VP all the way up to AspP (see Section 6.1). In contrast, periphrasis arises when T’s V-selectional feature is not satisfied by T’s complement. We propose that this occurs when T’s complement does not participate in category projection; that is, it does not inherit the category features of lower projections. This is how our analysis implements the difference between functional projections that trigger periphrasis, such as the perfect AspP in Swahili, and those that do not. Parallel stipulations are needed in other approaches, as reviewed in Section 5.

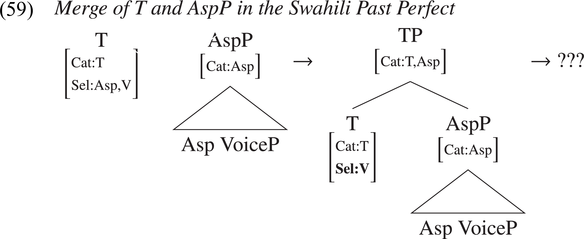

Consider the derivation of Swahili Past Perfect below, which proceeds the same way as synthetic tenses, but only up to AspP. Unlike the type of AspP found in synthesis, perfect AspP does not inherit the category of lower projections. Because of this, the category of AspP is just [Cat:Asp] – crucially, it does not include V. Consequently, T’s V-selectional feature remains unchecked after T is merged:

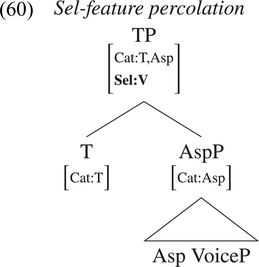

We propose that unsatisfied selectional features percolate to the phrasal level, here to TP:

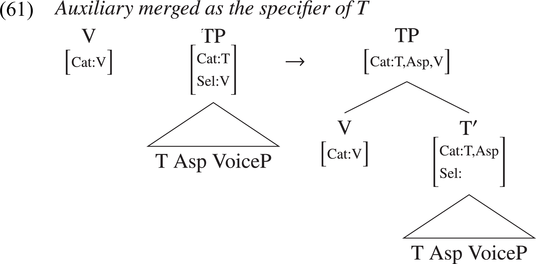

The [Sel:V] feature in TP triggers Merge of TP with an element of category V, a process referred to as cyclic selection in Pietraszko Reference Pietraszko2017, Reference Pietraszko2023:

The V in the specifier of T is realized as auxiliary be (kuwa in Swahili). Recall that the auxiliary is inflected for tense, and the lexical verb is inflected for perfect aspect (58). The tense inflection on the auxiliary is the realization of T,Footnote 16 while the perfect aspect inflection on the lexical verb is the realization of Asp. This completes the syntactic derivation of the Swahili Past Perfect. Importantly, no head movement applies between the auxiliary and T, in compliance with AfTonomy. Evidence against this head-movement relation is given in Section 4.

In summary, synthesis arises when T’s V-selectional feature is satisfied by the [Cat:V] feature projected from the lexical verb. Periphrasis is Merge of a new V to satisfy the V-selectional requirement of T when it cannot be satisfied this way.Footnote 17 As shown above, this occurs when T’s complement is not verbal.Footnote 18

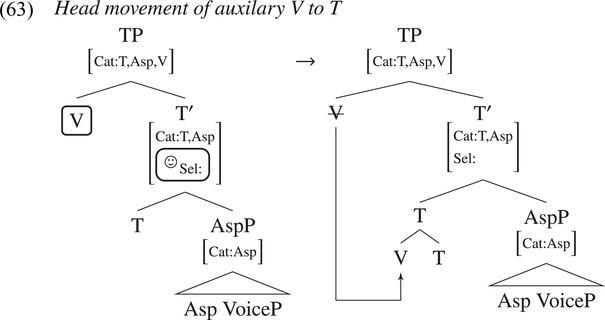

The derivation of the French Pluperfect is the same as the Swahili Past Perfect: Because perfect AspP is not verbal, an auxiliary is merged in the specifier of T to satisfy T’s V-selectional requirement. As discussed for synthesis in Sections 4 and 6.1, unlike Swahili, T triggers head movement in French. This correctly predicts that some head undergoes movement to T in periphrasis as well. Importantly, in this case, what undergoes head movement is the auxiliary in the specifier of T. The relevant [☺Sel:] feature is in TP, which according to our definition of head movement in (54), triggers movement of (the head of) its sister to its own head (T):

Although this looks like lowering, the locality condition imposed by the definition of head movement in (54) is the same in all cases – namely, sisterhood. In the standard case of head movement, the trigger is in the head, resulting in head movement out of the complement. In (63), however, the trigger is in the projection of the head, resulting in head movement out of the specifier. In both cases, however, the structural relation is the same: The moved head is the head of the selectee.

Recall that our analysis links head movement to selection: X can move to Y if it satisfies a selectional requirement of Y. It follows from the definition of head movement in (54) that, if more than one element satisfies the selectional requirement of a head, head movement must occur from the last such element. This is because head movement is triggered by a valueless [☺Sel:] feature. Consider the case of T, which has two selectional requirements (Sel:Asp,V). In synthesis, both are satisfied by T’s complement AspP, and so Asp undergoes head movement. In periphrasis, however, the complement of T satisfies only one of those requirements – namely, Asp. The V-selectional requirement is satisfied by the auxiliary at a later step, after the Sel:V feature projects to

![]() $ {\mathrm{T}}^{\prime } $

. Since it is the auxiliary that makes T’s Sel feature valueless, it must be the auxiliary that undergoes head movement to T.

$ {\mathrm{T}}^{\prime } $

. Since it is the auxiliary that makes T’s Sel feature valueless, it must be the auxiliary that undergoes head movement to T.

The selection-based analysis of periphrasis derives *V-Aux in the following way. First, the lexical verb embedded in AspP in (63) cannot undergo head movement to the auxiliary in the specifier of T because the two are not in a selectional relation (unlike in the base-generation analysis). Furthermore, they cannot both end up in T by head movement since, as we explained in the previous paragraph, only the auxiliary can undergo head movement to T in periphrasis.

Our analysis derives the complementarity between moving the lexical verb and the auxiliary to T, without positing that the auxiliary is inserted directly into T (as in the head-movement and stranded-feature approaches). Whether the auxiliary moves to T in a language depends on the properties of T. This derives not only AfTonomy (T triggers head movement only in some languages), it also derives uniformity of head movement across synthesis and periphrasis given a common T: Since French T triggers head movement, it forms a complex head with a verb in both synthesis and periphrasis ((13), (14a)). In Swahili, T does not trigger head movement, and so neither the lexical verb nor the auxiliary move to T in this language ((23), (29)).

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we argued that a selection-based theory of periphrasis combined with a selection-based theory of head movement correctly predicts two generalizations: that the lexical verb and the auxiliary cannot be related by head movement (*V-Aux) and that affixal Ts vary as to whether they are in a head movement relation with a verb (AfTonomy). *V-Aux follows from the view that T’s verbal selectional requirement is satisfied by different elements in synthesis and in periphrasis: by the lexical verb in the former and by the auxiliary in the latter. Assuming that head movement is parasitic on selection, we derive that in synthesis, only the lexical verb can move to T, and in periphrasis, only the auxiliary can do so. Given this analysis, AfTonomy is simply a consequence of lexical variation as to whether T triggers head movement or not.

Acknowledgments

We wouldd like to thank three anonymous Journal of Linguistics reviewers for their thoughtful comments, as well as audiences at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, the Southern African Linguistics Network, the 2024 Annual Cornell Undergraduate Linguistics Conference, LingDay 2024 at Boğazići University, and colloquia at the University of Göttingen, HSE University, the University of Southern California, the University of Maryland, the University of California, Santa Cruz, Rutgers University, Harvard University, Washington University in St. Louis, University College London, Yale University, the University of Potsdam and McGill University. We are also grateful to a Swahilli consultant and to Benjamin Spector and Z Sellami for their help with French data.