1. Introduction

This paper is concerned with the syntactic representation of inner aspect in Hungarian. Although there is a sizeable literature on various aspectual markers such as verbal particles (VPrts), result predicates (RPs), pseudo-objects (POs) or created/consumed objects (CCOs) (É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss2004, Reference É. Kiss, Piñón and Siptár2005, Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a, Reference É. Kiss and Kissb; Kiefer Reference Kiefer2006; Kardos Reference Kardos2012, Reference Kardos2016, Reference Kardos2019; Farkas & Kardos Reference Farkas and Kardos2018, Reference Farkas and Kardos2019a, Reference Farkas and Kardosb; Farkas Reference Farkas2019, Reference Farkas2020a, Reference Farkas2021; Hegedűs Reference Hegedűs2020), there is no consensus on the right analysis regarding their syntactic behaviour. In this work, our main goal is to attribute the event aspectual interpretations associated with the different marking elements to the syntactic configuration characterizing these elements. There are two main claims that we argue for:

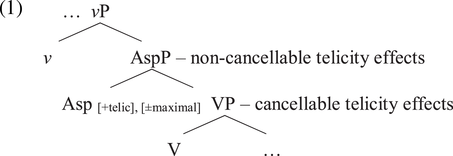

First, in line with previous literature on the syntax of inner aspect (see MacDonald Reference MacDonald2008 or Travis Reference Travis2010), we claim, building on Surányi (Reference Surányi2014), that Hungarian also has an aspectual functional projection, called AspP, sandwiched between VP and vP in the event domain, which is directly responsible for the aspectual interpretations associated with VPrts, RPs and POs. The analysis that we propose in this paper pertains to separable particles with an obligatorily telic function like meg in examples such as János meg-evett egy almát ‘János prt-ate an apple’ and János meg-szerelt egy gépet ‘János prt-fixed a machine’. In addition, with respect to the aspectual differences between VPrts/RPs, on the one hand, and POs, on the other hand, we argue, following Kardos (Reference Kardos2012, Reference Kardos2016) and Farkas & Kardos (Reference Farkas and Kardos2019a, Reference Farkas and Kardosb), that while the former serve an event-maximalizing function in their respective predicates by virtue of encoding an event-maximalizing operator, the latter have a non-maximalizing function by virtue of encoding an operator that picks out a contextually-defined, non-maximal subpart of the events in the denotation of their verbal predicates. In other words, although members of both classes of aspectual markers give rise to quantized and telic VPs, telicity in the case of the former goes hand in hand with maximality, whereas in the latter case it does not. In minimalist terms, AspP can be characterized in terms of two types of features: it is associated with a [+telic] feature and, in addition to that, a maximality feature as well, which can be valued in one of two ways, i.e. [+maximal] or [−maximal]. Thus, the properties of these two classes of aspectual markers can be described as follows: VPrts/RPs = [+telic, +maximal], POs = [+telic, −maximal].

Second, in accordance with prior literature (e.g. É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a; Kardos Reference Kardos2012, Reference Kardos2019), we show that telic readings in Hungarian are also available with verbs complemented with CCOs in the absence of any other aspectual marking elements. We show that while telicity in the previous case, i.e. when AspP is present, is an entailment; it is an implicature in the case of creation/consumption predicates, which means that telicity is cancellable in this verb class. Whereas non-cancellable telicity effects will be shown to be exerted by grammatical elements occupying the [Spec, AspP] position associated with the [+telic] feature and, in addition, the [±maximal] feature, characteristic of two subclasses of telic predicates; cancellable telicity will be argued to arise in the absence of a telic structure in the class of creation/consumption predicates. In other words, whereas AspP is projected in the case of aspectual markers with non-cancellable telicity effects, aspectual markers with cancellable telicity effects do not trigger the projection of this phrase. We also assume that in the case of other elements with no telicity effects (e.g. non-telicizing verbal particles or internal arguments other than quantized CCOs appearing in the environment of base verbs) AspP is, again, not projected.

In this paper we propose the following skeleton for Hungarian telicity-marking elements:

The chief aim of this paper is to provide an analysis of telicity entailments and the lack thereof as well as the (non)maximality effects with which telic predicates are associated by examining the aspectual behaviour of members of (i) the class of VPrts and RPs, (ii) the class of non-subcategorized POs, and (iii) the class of CCOs.

We also find it important to stress at the outset that, as far as verbal particles are concerned, given the complexity of the event structural and argument structural consequences of these elements, we cannot do justice to the richness of the verbal particle system in Hungarian within the confines of this paper. Concerning their event structural effects, telicizing particles like fully grammaticalized meg and particles associated with some lexical information in addition to their telicizing function, such as fel ʻupʼ in fel-mászott a fára ʻclimbed up the treeʼ, are assumed to exert their telicizing/event-maximalizing effects in [Spec, AspP]. By contrast, particles that do not make the predicate telic may be simply predicative elements, as in the case of ki ʻoutʼ in Az ing ki-lóg a nadrágból ʻThe shirt hangs out of the pantsʼ, occupying the specifier of a Pred projection (É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a). Particles with a purely predicative function are plausibly merged within the VP similarly to result predicates such as ropogósra ‘(lit.) onto crispy’ as in ropogósra sütötte a csirkét ‘roasted the chicken crispy’, where the latter are also argued to move to [Spec, AspP] to make the predicate telic (see Section 4.1).

The structure of the paper is as follows: In Section 2 we provide a summary of some important generalizations about Hungarian inner aspectual markers based on previous literature and also review some recent syntactic analyses of these marking elements. In Section 3 we present our theoretical assumptions about lexical aspect and grammatical aspect, two distinct, albeit related aspectual categories, as well as the structure of the VP so that we can present our proposal in Section 4 with these assumptions in mind. In Section 5 we discuss some consequences of the proposal focusing on various co-occurrence restrictions pertaining to the different inner aspectual markers. In Section 6 we conclude.

2. Previous literature on hungarian inner aspectual markers

Grammatical aspect (more specifically, perfectivity) has long been at the forefront of attention in the literature on Hungarian (see É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss2002, Kiefer Reference Kiefer2006, among many others), but the study of inner aspect is relatively new in Hungarian aspectology. In this section, we review some important generalizations that have been made about inner aspectual markers in prior literature in an effort to lay the groundwork for our analysis in subsequent sections.

2.1 Some generalizations about telic predicates in Hungarian and across languages

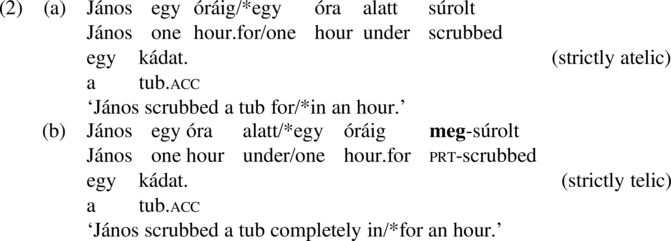

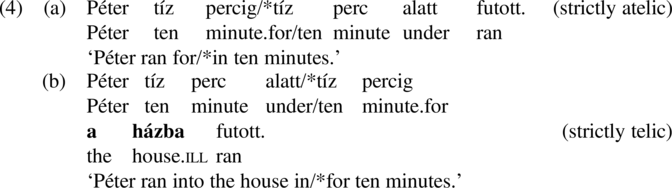

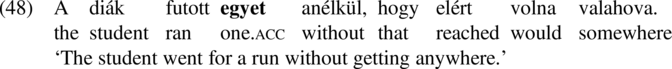

It is well-known that telic interpretations in Hungarian can arise in the presence of (i) verbal particles (2b), result predicates (3b) or goal-denoting predicates (4b) (see Csirmaz Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008a; É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a, Reference É. Kiss and Kissb; Kardos Reference Kardos2012, Reference Kardos2016); (ii) non-subcategorized pseudo-objects (5b) (see Piñón Reference Piñón, Bakró-Nagy, Bánréti and Kiss2001; Kiefer Reference Kiefer2006; Csirmaz Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008b; Farkas & Kardos Reference Farkas and Kardos2018, Reference Farkas and Kardos2019a, Reference Farkas and Kardosb; Farkas Reference Farkas2019, Reference Farkas2020a, Reference Farkas2021); and (iii) subcategorized created/consumed objects (6) (see É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss, Piñón and Siptár2005, Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a; Kiefer Reference Kiefer2006; Csirmaz Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008a; Piñón Reference Piñón and Kiss2008; Kardos Reference Kardos2019):

As shown above, all the elements in boldface may result in telicity, but there are differences in their telicity-inducing effects. Whereas the verbal particle meg in (2b), the result predicate laposra ‘(lit.) onto flat’ in (3b), the goal-denoting predicate a házba ‘into the house’ in (4b) as well as the POs egyet ‘one.acc’ and egy jót ‘one good.acc’ in (5b) give rise to non-cancellable telicity; the created object egy házat ‘a house.acc’ and the consumed object egy limonádét ‘a lemonade.acc’ in (6a) and (6b) yield variable telicity, as evidenced by the temporal adverbial test. Crucially, themes alone in the class of non-creation/non-consumption predicates will generally not give rise to telicity irrespective of their referential properties (see (2a) and (3a) above) (for a caveat, see fn. 3 below). Telicity obtains only if a verbal particle like meg, a resultative predicate like laposra ‘(lit.) onto flat’, a goal-denoting predicate like a házba ‘into the house’ or a pseudo-object like egyet ‘one.acc’ appears in the predicate (É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a; Kardos Reference Kardos2012, Reference Kardos2016).

That verbal particles, result predicates of end state/end location and incremental themes such as created and consumed objects figure in the calculation of telicity has also been widely discussed in the literature with respect to numerous other languages. In English, for example, while themes that have a measuring role are sufficient for telicity to obtain if they are associated with quantized reference (Verkuyl Reference Verkuyl1993, Tenny Reference Tenny1994, Krifka Reference Krifka and Rothstein1998), resultative predicates like clean in (7b) and verbal particles like up in (8c) also play a role in the aspectual make-up of the sentence in that they ensure non-cancellable telicity. Atelic readings in the environment of these elements are not available provided that the theme has quantized reference (Beavers Reference Beavers, Demonte and McNally2012).

As pointed out by Levin & Sells (Reference Levin, Sells, Uyechi and Wee2009), examples like (7a) are characterized by aspectual duality. A telic reading is available if the theme the table is meant to measure out the event of the verb, whereas an atelic interpretation is also possible if the verbal predicate is understood iteratively. On the other hand, examples like ate the soup/ate the sandwich in (8b) are also characterized by variable telicity, as discussed by Dowty (Reference Dowty1979), Hay et al. (Reference Hay, Kennedy, Levin, Matthews and Strolovitch1999) and Kardos (Reference Kardos2019), among others. In the presence of a resultative predicate like clean or a verbal particle like up, however, the examples in (7b) and (8c) become clearly telic.

As for telicity marking via pseudo-objects, it is more difficult to find examples in other languages whose grammatical behaviour is comparable to that of Hungarian egyet ‘one.acc’ and egy jót ‘one good.acc’. Regarding its semantic properties, a somewhat similar telicizing element is the prefix po- in Polish and other Slavic languages (see Piñón Reference Piñón, Avrutin, Franks and Progovac1994). The examples in (9) serve as illustration; the superscript I stands for ʻimperfective’ and P stands for ʻperfective’.

Piñón (Reference Piñón, Avrutin, Franks and Progovac1994) uses a number of diagnostics to show that verbs associated with the prefix po- exhibit features of both perfectives and imperfectives. He also argues that po- has the meaning of a durative adverbial with a contextual parameter and that given the analysis of this prefix as a derived measure function, verbs like poczytała ‘PO-read’ are associated with quantized reference, similarly to perfective verbs.

The subsequent discussion will show that Hungarian verbal predicates containing POs like egyet ‘one.acc’ also have quantized reference (see Farkas & Kardos Reference Farkas and Kardos2018), similarly to predicates containing VPrts or RPs (Kardos Reference Kardos2012, Reference Kardos2016), and their interpretation is also contingent on context. In this respect, they contrast with particle verbs. However, verbs prefixed by po- are also different from Hungarian egyet-type VPs in that the former allow for-adverbials and disallow the adverbial prawie ‘almost’, while the latter disallow for-adverbials and can co-occur with the adverbial majdnem ‘almost’, as will be illustrated in Section 4.

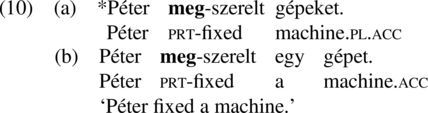

As for the semantic effects of verbal particles and resultative predicates in Hungarian, it has also been shown that in neutral sentences (i.e. declaratives without progressive aspect, negation or narrow focus) they impose constraints on themes such that their quantity must be known (É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss, Piñón and Siptár2005). This is exemplified in (10).

Whereas the bare plural gépeket ‘machines’ is unacceptable in the environment of the particle verb meg-szerelt ‘prt-fixed’ by virtue of having cumulative reference, the theme egy gépet ‘a machine’, which is interpreted with quantized reference, gives rise to a grammatical sentence with the same verb.

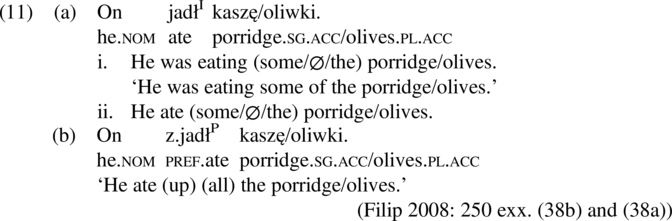

Slavic languages also show a similar behaviour, as has been pointed out by numerous scholars including, for example, Slabakova (Reference Slabakova2004) and Filip (Reference Filip and Rothstein2008). Here we illustrate this with Polish examples from Filip (Reference Filip and Rothstein2008).

What is of interest regarding the data above is that the example in (11b), which contains a perfective verb and a theme expressed by a bare noun, can only be interpreted with specific reference with respect to the theme. The event description in (b) is also obligatorily telic. By contrast, specificity of the theme is not required in (11a), where the sentence contains an imperfective verb, and telicity here is only an implicature as it can be cancelled. As noted by Filip (Reference Filip and Rothstein2008: 251), the interpretation of the theme is contingent on contextual factors.

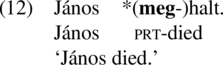

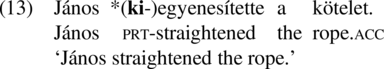

Another important generalization regarding Hungarian is that events that have an inherent endpoint must be overtly marked (É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a, Reference É. Kiss and Kissb; Kardos Reference Kardos2012, Reference Kardos2016). This is evidenced by the fact that, in the class of non-creation/non-consumption verbal predicates, achievements (12) and degree verbs associated with closed scales (13) (Wechsler Reference Wechsler, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005) must appear with a verbal particle or a resultative predicate (É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008b, Kardos Reference Kardos2016, Hegedűs Reference Hegedűs2017) in a sentence with a non-progressive, telic interpretation.Footnote 3

In (12) the verbal predicate meg-hal ‘prt-die’ expresses a dying situation, which is associated with an inherent endpoint, and thus omission of the verbal particle meg is not possible. Likewise, the verb stem egyenesít ‘straighten’ cannot occur without the particle ki in (13), as this predicate encodes a maximal endpoint, which corresponds to the state of (complete) straightness.

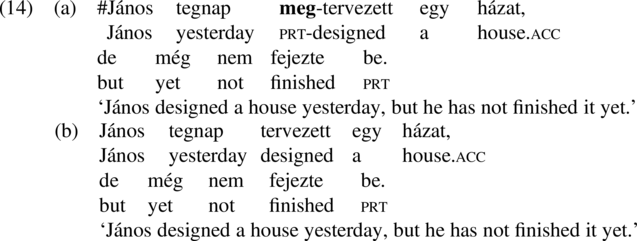

Finally, as already discussed above, the class of telicity markers in Hungarian is heterogeneous. Whereas VPrts, RPs and POs ensure non-cancellable telicity with respect to the verbal predicate, CCOs give rise to aspectual variability. Here we illustrate this further with the examples below:

As evidenced by the entailment test, meg-tervezett egy házat ‘prt-designed a house’ can only be interpreted as telic, whereas tervezett egy házat ‘designed a house’, which does not appear with a verbal particle, is compatible with an interpretation that the attainment of an endpoint has not been achieved. Telicity in this latter case can be cancelled.

In recent decades, researchers have attempted to represent telicity-marking elements in the syntax of the Hungarian sentence in different ways. We briefly review some of these proposals in the next section.

2.2 More recent claims concerning the syntax of event aspectual markers in Hungarian

It is verbal particles and result predicates that have generated the most amount of research in the past few decades regarding aspectualizers in Hungarian. According to the most influential analysis (É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss2004, Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a), the verbal particle is a secondary predicate that merges in the postverbal domain of the Hungarian sentence and, in a one-step derivation, moves to the specifier position of PredP, situated above VP, to check the predicative feature of the head, whereas V moves to Pred in the course of the derivation. The telicizing effect of the particle is a direct consequence of its lexical semantics. As discussed in Section 4, this is in contrast to our analysis, as we assume that it is the grammar that is directly responsible for creating telic structures (Borer Reference Borer2005) associated with verbal particles and result predicates.

In another study, Surányi (Reference Surányi2009) advocates a vP-shell analysis of the Hungarian event domain based on Surányi (Reference Surányi2006), and proposes a two-step derivation of verbal particles and result predicates whereby they first move from their base-generated postverbal position to [Spec, PredP], sandwiched between VP and vP, and then to [Spec, TP] to check the EPP feature of T.

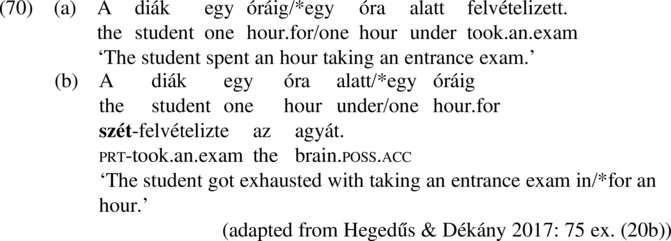

Another recent analysis of verbal particles is given by Hegedűs & Dékány (Reference Hegedűs, Dékány, Lipták and van der Hulst2017), where both separable and inseparable particles are addressed. On the one hand, in separable particle verbs like el-fut ‘run away’, the particle appears in the immediately preverbal position in neutral sentences (i.e. declaratives without progressive aspect, negation or narrow focus) and in a postverbal position in non-neutral sentences (declaratives with progressive aspect, negation, narrow focus, wh-interrogatives and imperatives). On the other hand, in inseparable particle verbs like felvételizik ‘take an entrance exam’ (where fel is the inseparable particle), the particle appears in the immediately preverbal position in both neutral and non-neutral sentences. The authors take separable verbal particles to be small clause predicates in the complement zone of V. They also claim that separable particles that can occur with inseparable particle verbs such as szét in szét-felvételiztem az agyam ‘I got exhausted with taking entrance exams’ are merged in a specifier position ([Spec, PredP]) located between VP and vP.

Next, Hegedűs (Reference Hegedűs2017) provides a preliminary syntactic account of endpoint-denoting elements in Hungarian. Her main concern is the structural characterization of the cross-linguistic variation between verb-framed and satellite-framed languages (Talmy Reference Talmy and Shopen1985). She points out that Hungarian, a satellite-framed language, differs from verb-framed languages and also from English, another satellite-framed language, in that results/goal points must be separately instantiated in this language. Particles never incorporate into the V head, and there is no N-to-P incorporation, where the resulting compound incorporates into V in the manner proposed by Hale & Keyser (Reference Hale and Keyser2002) for denominal verbs like shelve. On this view, particles appear as p heads in the syntax, where pPs are complements of V and the internal argument occupies the specifier of this phrase.

Finally, Surányi (Reference Surányi2014) argues for an aspectual functional projection, AspP, flanked by VP and vP, in line with MacDonald (Reference MacDonald2008) and Travis (Reference Travis2010), thereby directly associating inner aspectual interpretations with the syntactic structure of the Hungarian sentence. On this analysis, verbal particles, goal-point denoting PPs and some other elements such as bare nominals are base-generated in a postverbal position and first move to [Spec, AspP] for the purpose of pseudo-incorporation before they eventually end up in a vP-external position. As will be clear in the subsequent discussion, we side with Surányi (Reference Surányi2014) in assuming a vP-medial aspectual functional projection in Hungarian, but also argue that (i) AspP is associated not only with the [+telic] feature but also with the [±maximal] feature, and (ii) telicity may also arise in the absence of AspP in the case of creation/consumption predicates. These assumptions will allow us to capture the different event structural properties associated with VPrts, RPs, POs and CCOs.

Similarly to particles, POs like egyet ‘one.acc’ and egy jót ‘one good.acc’ have also been argued to merge within vP and move to [Spec, PredP] when they precede the (semelfactive) verb. Just like on É. Kiss’s (Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a) analysis of verbal particles, the telicity of predicates containing pseudo-objects has been regarded as a matter of semantics (Csirmaz Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008b).

In this work we propose a syntactic analysis of the three classes of aspectual markers discussed so far, where we pay special attention to how the event structural properties characterizing these elements are to be represented in the structure of the Hungarian sentence. Before proposing our analysis, however, we discuss our assumptions regarding the relationship between grammatical aspect and lexical aspect and the structure of the VP in Section 3.

3. The framework in a nutshell

3.1 Outer aspect versus inner aspect

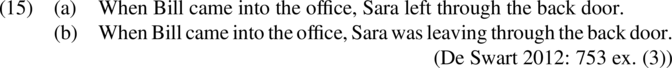

Aspect is a term that has been used to refer to (at least) two distinct domains of study: outer (also called grammatical or viewpoint) aspect and inner (also called lexical or situation) aspect, also referred to as Aktionsart; see Smith (Reference Smith1991). On the one hand, outer aspectual categories are generally encoded by morphological devices or periphrastic constructions. Outer aspect is often responsible for grammatically signalling whether the verbal predicate expresses an ongoing situation or one that is completed. We illustrate this opposition with the following pair of sentences from English:

The sentence in (15a) presents both Bill’s coming into the office and Sara’s leaving through the back door as completed events, where the former precedes the latter in time. By contrast, (15b) expresses Bill’s coming into the office as a completed event, whereas Sara’s leaving through the back door as ongoing. The two events are described as overlapping; a consecutive reading is not available.

On the other hand, the categories that belong to inner aspect are encoded in the verb phrase by means of inherent aspectual features. As we will see below, inner aspect, a vP-related functional category, can be morphologically encoded for instance by verbal particles.

Evidence for these distinct – albeit related – aspectual categories with respect to Hungarian has been provided by Csirmaz (Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008a). Here we only illustrate the perfective–imperfective distinction with the examples in (16), where inner aspect is kept constant; both sentences contain a telic predicate.

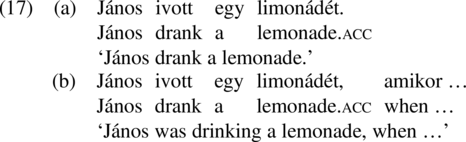

The interpretational differences are significant: whereas the perfective and telic (16a) means that Kati climbed up the tree, the progressive and telic (16b) means that Kati was engaged in the event of climbing up the tree when the event of the subordinate clause occurred. The perfective–imperfective contrast is reflected in word-order differences. Whereas in (16a) the particle fel precedes the verb, in (16b) it follows it. Outer aspectual differences are also reflected in the prosody of the Hungarian sentence. Consider (17).

The sentences in (16a) and (16b), and also in (17a) and (17b), are different regarding the stress pattern they are associated with. Whereas in the (a) examples the verbs bear the main stress, in the (b) examples stress is distributed over the words mászott ‘climbed’, fel ‘prt’ and fára ‘tree.sub’ in (16b) and ivott ‘drank’ and limonádét ‘lemonade.acc’ in (17b) (for similar data, see É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss2002: 63). Non-contrastive topics like Kati and János cannot receive the main stress. For more on Hungarian sentence prosody, see Hunyadi (Reference Hunyadi2002).

In what follows we will keep outer aspect constant, as the analysis of this aspectual category is beyond the scope of this paper. The Hungarian examples in the rest of the paper are meant to receive a perfective interpretation.

3.2 The structure of the VP

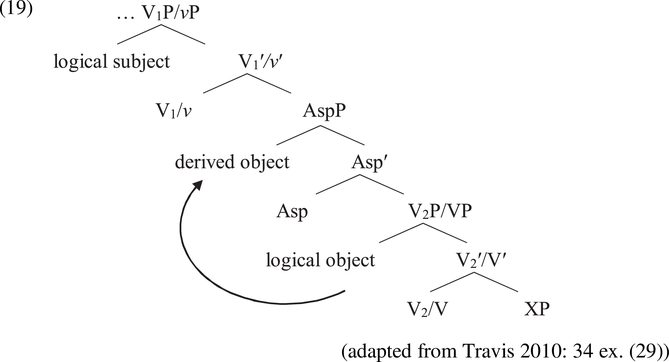

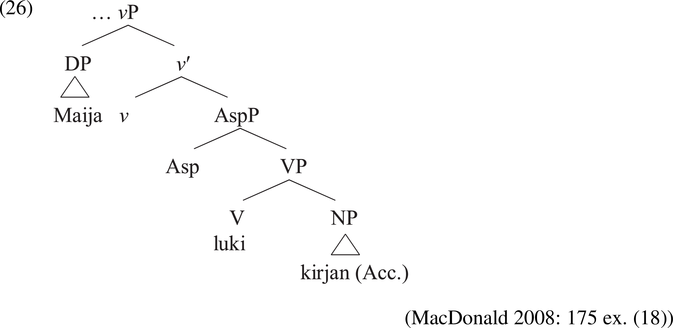

As far as the structure of the verb phrase is concerned, we follow MacDonald (Reference MacDonald2008), Travis (Reference Travis2010) and Surányi (Reference Surányi2014) (see Section 2.2) in assuming that they can be split into a lexical VP and a light vP, and in claiming that there is an inflectional aspectual category sandwiched between these two phrases (called AspP).

The main goal of MacDonald’s (Reference MacDonald2008) analysis is to explore the syntactic nature of inner aspect from a minimalist perspective. With respect to English inner aspect, two independent properties must be taken into consideration. To account for the object-to-event mapping property (i.e. the ability of a nominal expression to affect the aspectual interpretation of a predicate), the author argues for the existence of an aspectual phrase (AspP) within the verbal domain (more exactly, between vP and VP), which is implicated in the aspectual interpretation of the predicate and determines a domain of aspectual interpretation. Moreover, the Agree relation with Asp is the syntactic instantiation of the object-to-event mapping (and it is always the nominal expression closest to Asp that enters this mapping relation). To capture properties related to event structure, the author argues for the existence of interpretable event features that enter the syntax on certain heads (Asp, V), and which express whether the event has a beginning (<ie> feature) and/or an end (<fe> feature). These event features contribute to the aspectual interpretation of the sentence.

An important consequence of AspP is that it is only elements that are within the domain of aspectual interpretation that can contribute to the aspectual interpretation of the predicate. In other words, for an element to contribute to the aspectual interpretation of a predicate, it must be within the domain of aspectual interpretation defined by AspP and everything contained by AspP. This implies that subjects and adjuncts, which are outside the domain of aspectual interpretation defined by AspP, cannot delimit the event of V, in sharp contrast to complements, which are argued to be below AspP, occupying a position internal to VP and hence influencing the aspectual interpretation of the predicate; see the following tree diagram:

The starting point for the discussion in Travis (Reference Travis2010) is the hypothesis that, similarly to the movement of the subject DP from its merged position ([Spec, vP]) to the specifier of a functional projection ([Spec, TP]), the object DP also undergoes movement from its merged position to the specifier of a functional projection. This means that there must be a functional head within the VP which is responsible for this latter movement and there seem to be morphological reasons to believe that there is an inflectional category within the VP, and that this non-lexical category is Aspect. Moreover, the specifier position of this latter functional projection ([Spec, AspP]) serves as the landing site for derived objects. More precisely, internal DP arguments affecting the aspectual interpretation of the predicate are merged in [Spec, VP] (logical object position) but they move to [Spec, AspP] (derived object position) if they induce a telic interpretation on it (see below). Similarly to MacDonald (Reference MacDonald2008), direct object themes are allowed to remain in [Spec, VP], in which case they do not measure out the event. In addition, it is not the case that all elements in the domain of inner aspect are part of the computation, but in order to be part of the computation, they must be part of this domain. The tree diagram in (19) shows these syntactic assumptions:

There are multiple positions in the articulated VP that have been claimed to figure into the calculation of inner aspectual interpretations. Travis (Reference Travis2010: 242, 244) argues for three positions where telicity can be marked and that languages can utilise in different ways:

The different positions have important consequences with respect to the interpretation of the theme DP in the verbal predicate. For example, telicity-marking elements in v (e.g. preverbs) in Bulgarian impose semantic restrictions on the theme DP such that it must be specific (or have a specific reading) by virtue of having this DP within their scope, i.e. in their c-command domain.

4. The proposal

In this section of the paper we argue that telic interpretations become available in two different ways in Hungarian: (i) telicity may arise as an entailment due to an aspectual functional projection, AspP, sandwiched between VP and vP in the structure of the sentence, and (ii) it may also arise as an implicature in the case of a specific predicate class, the class of creation/consumption predicates. It is verbal particles like meg in VPs such as meg-eszik egy almát ‘prt-eat (up) an apple’, result predicates like laposra ‘(lit.) onto flat’ in resultative constructions such as laposra kalapálja a fémet ‘hammer the metal flat’ and non-subcategorized pseudo-objects like egyet ‘one.acc’ in VPs such as fut egyet ‘go for a run’ that induce telicity in the [Spec, AspP] position by functioning as aspectual operators picking out maximal or contextually defined non-maximal subparts of the events denoted by their verbal predicates, thereby ensuring that the resulting verbal predicates have quantized reference. Telicity in this case cannot be cancelled, which is expected as it is ʻthe grammar, rather than the lexical semantics of any particular listeme’ that forces ʻthe projection of telic structure’ (Borer Reference Borer2005: 153). On the other hand, created or consumed objects with quantized reference may also give rise to telic readings, but the predicates whose telicity is due to such objects can also easily receive atelic interpretations. It is also crucial to note that Hungarian objects with quantized reference in other verb classes do not have the ability to measure out events and thus such constituents do not give rise to telicity. Thus, Hungarian turns out to be different from languages like English, German, Dutch and Spanish, where bounded objects often have a measuring-out function in the environment of members of the class of creation/consumption verbs and those of other verb classes.

In this section we provide an analysis of entailed versus implied telicity by first discussing the syntax of verbal particles, result predicates and pseudo-objects in Sections 4.1 and 4.2, respectively, and then we devote Section 4.3 to the aspectual effects of created/consumed objects.

4.1 Verbal particles and result predicates

As noted earlier, Hungarian verbal particles and result predicates appear in the immediately preverbal position in neutral sentences and often have a telicizing function (Csirmaz Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008a; É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a, Reference É. Kiss and Kissb):

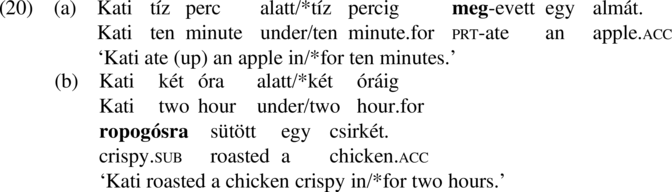

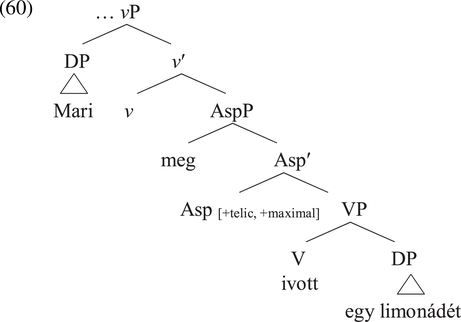

Verbal particles like meg (20a) and result predicates like ropogósra ‘(lit.) onto crispy’ (20b) have been shown to encode an event-maximalizing operator (MAXE) (Filip & Rothstein Reference Filip, Rothstein, Lavine, Franks, Filip and Tasseva-Kurktchieva2006), which is applied to a partially ordered set of events, from which they pick out the unique largest event at a given situation, thereby ensuring that the resulting predicates have quantized reference, and thus they are interpreted telically, as shown by the temporal adverbial test (see Kardos Reference Kardos2012, Reference Kardos2016). We argue that particles like meg exert their event-maximalizing function in their base-generated [Spec, AspP] position by checking the [+telic] and [+maximal] features of the Asp head. As we will see in Section 4.2, meg-type telicity-marking verbal particles in examples like (20a) are different from pseudo-objects like egyet ‘one.acc’ in VPs such as aludt egyet ‘got some sleep’, which we also assume to be base-generated in [Spec, AspP], in that the latter are not associated with maximality, though they also give rise to verbal predicates with quantized reference and non-cancellable telicity. The representation that we propose for sentences like Kati meg-evett egy almát ‘Kati prt-ate an apple’ is given below:Footnote 5

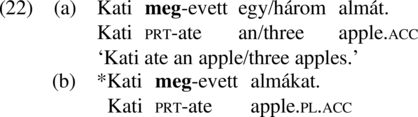

An important consequence of the event maximalizing element meg in [Spec, AspP] is that it imposes semantic constraints over the theme in its c-command domain such that it cannot be a bare plural associated with cumulative reference. Consider (22) below.

That themes like almákat ‘apples’ cannot appear in the environment of event maximalizing elements follows from the fact that the event maximalizing operator MAXE encoded in the particle meg can only apply to events that are ordered with respect to the scalar arguments of their verbal predicates such that they function as a measuring device allowing the identification of the size of the denoted events. Since a measuring scale cannot be deduced with bare cumulative NPs, MAXE cannot apply (Filip Reference Filip and Rothstein2008).

Cross-linguistically, it is not clear whether such an effect characterizes preverbs in languages such as Dutch and German. As also noted by Kardos (Reference Kardos2019: 506–507 fn. 20), speaker judgements vary regarding the co-occurrence of particle verbs and themes with cumulative reference in these languages. In Travis (Reference Travis2010: 248 ex. (10)), the German sentence Ich habe zwei Stunden lang Weinflaschen ausgetrunken ‘I drank up wine bottles for two hours’ is shown to be grammatically somewhat questionable, whereas in Fleischhauer & Czardybon (Reference Fleischhauer and Czardybon2016: 189 ex. (29b)) the sentence Der Mann hat Äpfel aufgegessen ‘The man ate up apples’ is marked as clearly ungrammatical. The latter example suggests that German particles like auf are similar to Hungarian verbal particles in that they also have an event-maximalizing role.

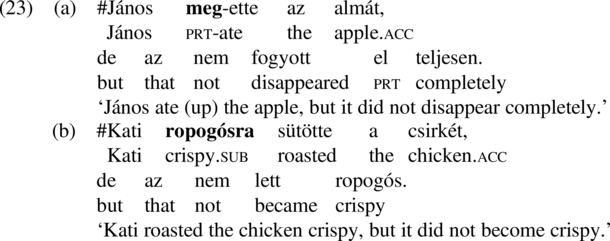

Another important consequence of event maximalization is that, in the presence of a verbal particle (23a) or a result phrase (23b), the attainment of a specific final state cannot be cancelled.

The negation of the inference that the apple completely disappeared in (23a) and that the chicken became crispy in (23b) results in infelicity. This is evidence that the presence of the particle meg and that of the result predicate ropogósra ‘(lit.) onto crispy’ ensures the attainment of the final states of being ‘gone’ and crispy, respectively.

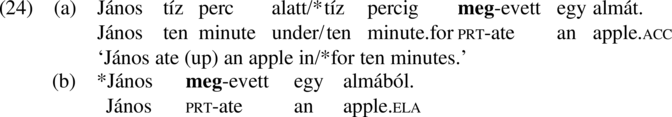

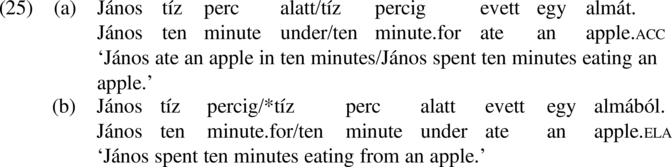

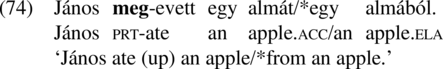

Another important syntactic effect of particles like meg in the examples discussed so far is that they must appear with accusative-marked incremental themes. By contrast, in the absence of meg, the theme argument may also be assigned a case other than accusative. Compare and contrast the (a) and (b) examples in (24) and (25).

As the examples show, the particle verb meg-evett ‘prt-ate’ requires the accusative case marking -t on the theme (24a) and rejects the constituent egy almából ‘from an apple’, which carries the elative case marking -ból (24b) and is associated with the meaning that the apple has been partially affected in the denoted eventuality. By contrast, the particleless verb evett ‘ate’ can occur either with a theme carrying accusative case, as in (25a), or one associated with elative case, as in (25b). We believe that these facts are compatible with the standard assumption that accusative case is assigned by little v via Agree. When discussing data from Finnish, MacDonald argues that ʻgiven the structural proximity of v to Asp, there is no syntactic reason why the internal argument cannot Agree with Asp as well’ (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2008: 176). The representation that he gives for Finnish Maija luki kirjan ‘Mary read a book (and finished it)’ is as follows:

The syntactic representation that we propose for the Hungarian counterpart of the Finnish sentence above is given below, where, again, we represent the verb in its base-merged position:

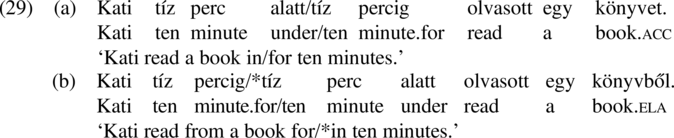

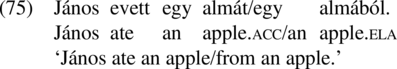

An important difference between Finnish and Hungarian when it comes to these structures is that whereas [Spec, AspP] is filled by an overt verbal particle in Hungarian (see (27)), there is no overt marking element in Asp or [Spec, AspP] in Finnish (see (26)). Likewise, the particle verb el-olvas ‘prt-read’ in (28) is also incompatible with a theme argument that is assigned a case other than accusative. This is shown below.

The particleless verb olvasott ‘read’, on the other hand, readily accepts objects with accusative case or elative case associated with a partitive reading, as illustrated in (29).

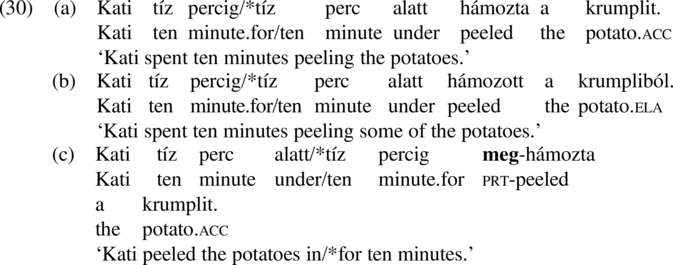

Overall, then, we agree with MacDonald (Reference MacDonald2008: 171) in that case and aspect are independent syntactic categories, as evidenced by the fact that, for example, atelic stative structures also contain objects carrying accusative case (see the Hungarian examples in (31a) and (32a) below and the Finnish examples in MacDonald (Reference MacDonald2008: 175 exx. (17a) and (17b)). However, it appears that aspect and case are also related in a way that once AspP is projected, the morphosyntactic properties of the internal theme argument inside VP are constrained such that this argument must receive accusative case unless the internal argument is assigned nominative case in [Spec, TP] as the subject of the sentence in the case of unaccusatives.Footnote 6 On the other hand, however, Hungarian objects alone do not contribute to the aspectual interpretation of the sentence in the absence of AspP regardless of the case assigned to them, as shown in (30).Footnote 7 For more on this regarding other languages, see also Pereltsvaig (Reference Pereltsvaig, Alexiadou and Svenonius2000)Footnote 8 and Travis (Reference Travis2010).

As shown above, the particleless verb hámoz ‘peel’ in (30a) and (30b) heads an atelic predicate regardless of the type of case that is assigned to the internal theme argument, whereas the particle verb meg-hámoz ‘prt-peel’ and the accusative object in (30c) form a telic predicate. By contrast, in English and other similar languages, an accusative DP that is also bounded is sufficient in the environment of the verb peel to express a telic situation.

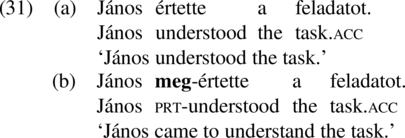

Verbal particles like meg may also be attached to stative verbs like ért ‘understand’ and ismer ‘know’. The particle verbs meg-ért ‘prt-understand’ and meg-ismer ‘prt-know’ are no longer stative but they express change-of-state events.

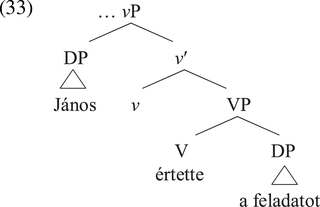

The examples in (a) both describe stative situations, whereas the examples in (b) express telic changes of state. In (31b) the experiencer, János, ends up in the mental state of understanding the task, whereas in (32b) Bálint ends up in the final state of knowing the teacher. The telicity of the examples in (b) is due to the particle meg functioning as an event maximizer in [Spec, AspP], whereas the atelicity of the examples in (a) is attributed to the lack of AspP below vP.Footnote 9 Crucially, we side with Borer (Reference Borer2005) in claiming that ʻatelicity is lack of telicityʼ (Borer Reference Borer2005: 125), i.e. there is no specific atelic structure in the syntax: atelicity arises in the absence of AspP. Consider the representation of (31a) in (33), whereas (31b) is illustrated in (34).

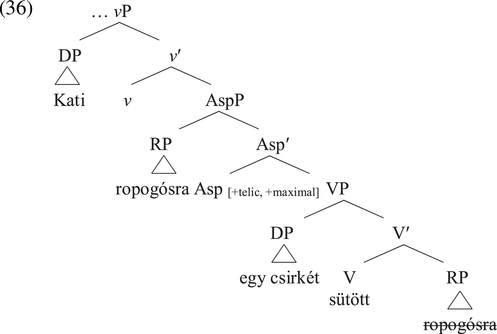

As far as resultative predicates are concerned, we first remark that they are frequently sublative case-marked, where the sublative suffix -ra/-re is primarily a directional case suffix expressing the meaning ‘onto’. The RP is merged inside VP and moves to [Spec, Asp], where it exerts its telicizing function by virtue of checking the [+telic] and [+maximal] features. As opposed to particles like meg, the RP has two functions: it turns the VP telic and it also specifies the result state. Sentence (20b), repeated as (35), is represented in (36). It must also be noted that the final word order characterizing this example is achieved by further movement of the RP and that of the verb to the specifier/head position of TP above vP, see also fn. 5 above.

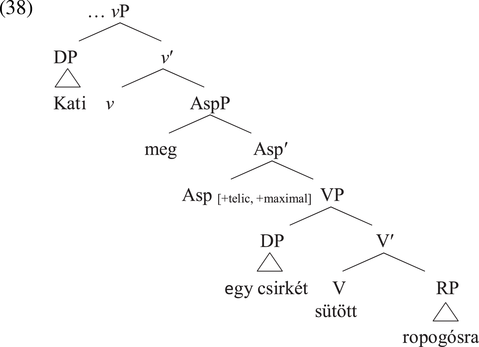

Crucially, RPs may co-occur with particles like meg as illustrated by the example in (37). This can be captured if we assume that particles like meg are merged in [Spec, AspP], whereas result predicates are generated as complements of V and stay in situ, as shown in (38) (again, further movements account for the final word order given in (37) below).Footnote 10

To summarize, in this section, we have shown that VPrts like meg and RPs like ropogósra ‘(lit.) onto crispy’ are both capable of checking the [+telic] and [+maximal] features of the Asp head and thus they ensure that the predicates that contain them are telic. An important difference between them is that whereas the former is merged in [Spec, AspP], the latter is generated within the VP and obligatorily moves to [Spec, AspP] from its base position in the absence of a telicity-marking element in this specifier position.

In the next section, we turn to other aspectual marking elements which also give rise to telicity, but they do so without ensuring that the verbal predicate is associated with a maximal-event interpretation.

4.2 Pseudo-objects

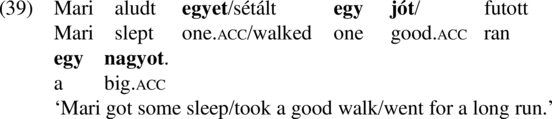

POs like egyet ‘one.acc’, egy jót ‘one good.acc’, and egy nagyot ‘one big.acc’, which typically accompany activity verbs (39), are accusative-marked constituents with no referential value.Footnote 11

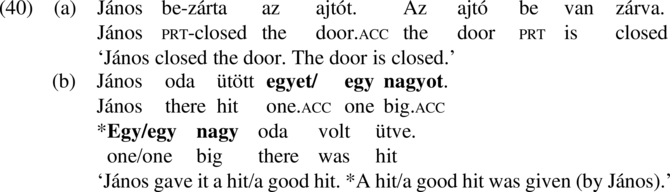

They are also non-subcategorized and non-thematic objects, which do not denote an affected entity.Footnote 12 They stand in contrast to subcategorized, referential and thematic internal arguments, as shown by the test of passivization below; see also Csirmaz (Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008b), Farkas & Kardos (Reference Farkas and Kardos2018) or Farkas (Reference Farkas2019, Reference Farkas2021):

The example in (40b) shows that the PO does not denote a referential entity, one that could be interpreted as the undergoer directly affected by the event of the verb, therefore it cannot appear in the derived subject position of passive structures, contra the object in (40a). For further syntactic tests that demonstrate the non-subcategorized, non-referential and non-thematic quality of the PO, see Farkas (Reference Farkas2021).

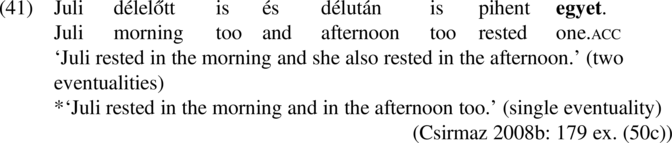

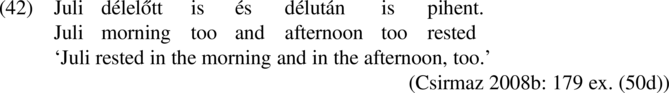

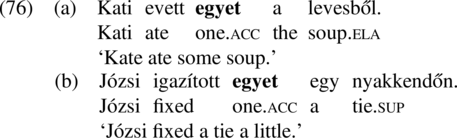

Drawing on Tenny’s (Reference Tenny1994) terminology, Csirmaz (Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008b: 169) calls these POs situation delimiters, which turn atelic predicates into telic ones, as evidenced by the coordination test below:

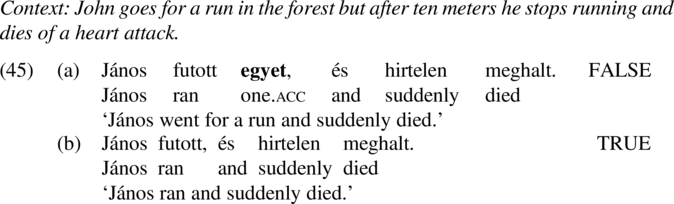

This sentence can only be interpreted to describe two distinct resting eventualities, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. This kind of semantics is associated with telic event descriptions (Verkuyl Reference Verkuyl1993). Coordinated atelic event descriptions, on the other hand, can also be interpreted as expressing a single eventuality, as evidenced by (42), where the resting eventuality holds during both temporal intervals as a single eventuality.

Farkas & Kardos (Reference Farkas and Kardos2018: 371) argue that these POs encode an aspectual operator that picks out a contextually specified non-maximal subpart of the events in the denotation of the verbal predicate.

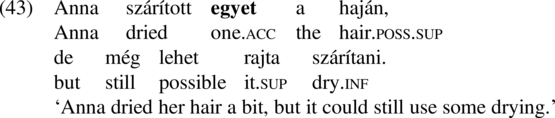

The non-maximality requirement is evidenced by the fact that the event expressed by the verbal predicate in the first clause can still be continued as in (43) or performed once again, as shown below:

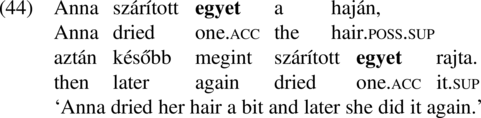

However, there is a minimum amount of hair-drying/sleeping/running etc. event that needs to occur for the truth of sentences containing egyet-type POs. This is illustrated below:

As shown by these examples, any amount of running will not satisfy the truth conditions of (45a). However, no such restriction is observable in (45b).

The fact that maximality is not associated with egyet-VPs is also evidenced by their incompatibility with adverbials such as teljesen ‘completely’, egészen ‘completely’ or maximálisan ‘maximally’ (see also Farkas & Kardos Reference Farkas and Kardos2018: 372). Consider the example below:

As expected, the verbal predicate szárított egyet a haján ‘dried her hair a bit’ may also appear in a sentence where the attainment of a maximal endpoint corresponding to the state of complete dryness is cancelled.Footnote 13 This is shown below.

In addition, in line with the non-maximality requirement, egyet-VPs are not associated with a prominent end result state or location, unlike verbal particles or result predicates. Thus, clauses containing a PO are compatible with continuations that express that no specific endpoint has been reached at the termination of the event described by the verbal predicate.

Furthermore, predicates encoding an open scale can appear with egyet ‘one.acc’ (49a), but those encoding a closed scale – where maximality is encoded in the verb – cannot (49b); see also Farkas & Kardos (Reference Farkas and Kardos2018: 371):

Then, egyet ‘one.acc’ cannot appear with achievements, which are maximally delimited; see also Csirmaz (Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008b: 179):

As will be further illustrated in Section 5, verbs like érkezik ‘arrive’ are also incompatible with POs since it is not possible for the latter to be assigned accusative case in an unaccusative structure.

Finally, predicates containing POs have a simple event structure. This is evidenced by their non-ambiguous counterfactual reading with the adverb majdnem ‘almost’ (see also Farkas & Kardos Reference Farkas and Kardos2019b: 301), which makes these structures similar to what Piñón (Reference Piñón and Kiss2008: 91–92) refers to as weak accomplishments.

In the case of this sentence the only reading available is the counterfactual one, in which the adverb majdnem ‘almost’ has wide scope and modifies the entire event, so the event almost begins (i.e. ‘this morning Mari almost went for a run but crucially she did not’). The incompletive interpretation, in which majdnem ‘almost’ has narrow scope and modifies the end of the event, so the event begins and almost ends, is not available.

Overall, then, it is clear that egyet-type pseudo-objects are responsible for non-maximal event delimitation and in this respect they contrast with verbal particles and result predicates, which are associated with a maximal-event interpretation, as discussed in Section 4.1.

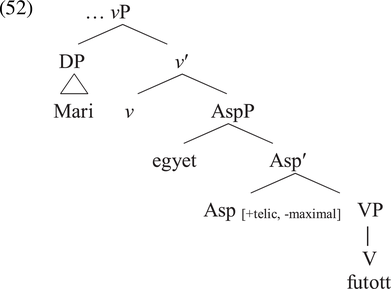

With respect to their syntax, two properties need to be taken into consideration: (i) POs differ from subcategorized, thematic and referential internal arguments, which are merged inside the VP; and (ii) they are associated with telicity and non-maximality. We argue that they are merged in the specifier of AspP, where they check the [+telic] and [−maximal] features of the head. The tree diagram that we propose for a sentence like Mari futott egyet ‘Mari went for a run’ is given below:

In addition, as egyet ‘one.acc’ does not undergo movement to a position inside a higher (functional) phrase but the verb undergoes head movement (at least) from V to Asp and then to v, at the end of the derivation the postverbal position of egyet is ensured.Footnote 14

In sum, in this section we have taken a close look at the properties of the Hungarian PO egyet ‘one.acc’, and some other POs with similar aspectual features. We have shown how these pseudo-objects are different from canonical, referential objects in their grammatical behaviour. In the next section, we turn to a subset of referential objects, created/consumed objects, which can also make verbal predicates telic given their specific grammatical properties.

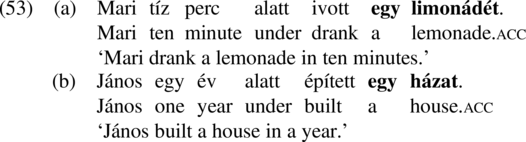

4.3 Created/consumed objects

CCOs in Hungarian, similarly to English, German, Dutch, Italian and Spanish, can measure out events (Tenny Reference Tenny1994) when associated with quantized reference (É. Kiss Reference É. Kiss, Piñón and Siptár2005, Reference É. Kiss and Kiss2008a; Csirmaz Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008a; Piñón Reference Piñón and Kiss2008), as shown in (53):

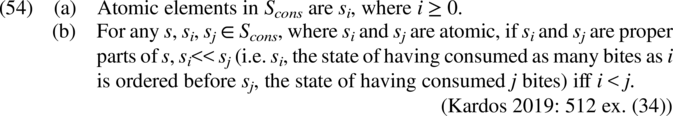

Kardos (Reference Kardos2012, Reference Kardos2019) argues, assuming Beavers’s (Reference Beavers, Demonte and McNally2012) figure–path relations model, which is built on Krifka’s (Reference Krifka and Rothstein1998) mereological analysis of telicity, that it is the unique homomorphic relation obtaining between the part structure of the scalar argument of creation/consumption predicates and that of the theme that gives rise to the aspectual effects characterizing these predicates. On this analysis, verbs like Hungarian eszik ‘eat’ and English eat are four-place predicates expressing a relation between a scalar argument s, a causer y, a figure x, and an event e. Scales are assumed to have a mereological part structure comprising atomic subparts, which are totally ordered states (s0, s1) corresponding to states of affairs in which the referent of the theme has been consumed bite by bite. Consumption scales Scons are characterized as follows:

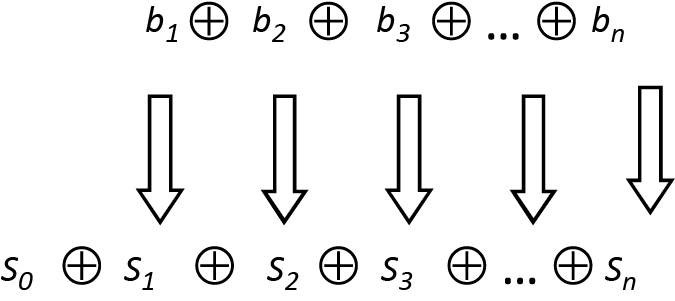

The unique homomorphic relationship that obtains between scales and themes in this predicate class is shown in Figure 1, taken from Kardos (Reference Kardos2019: 512), where b1, b2 correspond to the bites the theme can be divided into in an eating event:

Figure 1 The part structure of the consumption scale as determined by the part structure of the theme.

On this analysis, consumption (and creation) verbs lexically encode a homomorphic relation between the scale and the theme, which ensures that the initial subevent of the eating event corresponds to a state of affairs wherein not a single bite of the referent of the theme has been consumed and the final subevent corresponds to a state of affairs wherein the theme has completely disappeared. Telicity obtains if the final subpart of the scale can be determined, as in the case of themes having quantized reference (ibid.).Footnote 15

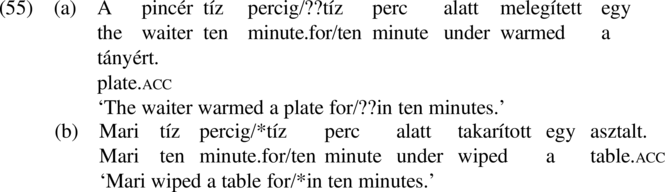

In the case of non-creation/non-consumption predicates, where the structure of the scale encoded in the head verb is independent of the theme, as in (55), Hungarian predicates containing a quantized theme and a base verb are obligatorily atelic.Footnote 16

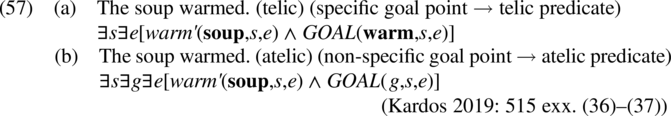

As expected based on the discussion in Subsection 4.1, the telicity of these predicates is ensured by constituents external to the verb and the thematic object; it is either a verbal particle, a result predicate or a pseudo-object that is directly responsible for non-cancellable telic interpretations in the class of non-creation/non-consumption predicates. The difference in the semantics of the predicates representing the two predicate classes is also captured in the logical representations below the examples in (56) and (57), where the function f’ is responsible for picking out the final subpart of consumption scales in the presence of quantized themes.Footnote 17

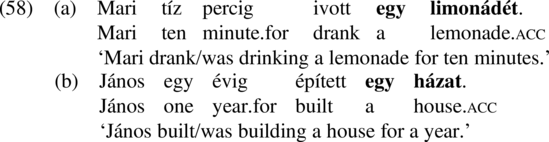

Crucially, however, Hungarian objects like egy limonádét ‘a lemonade.acc’ and egy házat ‘a house.acc’ can just as easily give rise to atelic interpretations with ivott ‘drank’ and épített ‘built’, respectively, as shown in (58) below.Footnote 18

Here we would like to reiterate Borer’s (Reference Borer2005: 153–154) idea that the projection of some grammatical structure (due to, for example, a DegP headed by completely in straighten the rope completely) is what ensures the impossibility of cancelling telicity. If our hypothesis that no quantity structure (using Borer’s terminology) is associated with Hungarian predicates like those in (58) is correct, it is perhaps to be expected that telicity in such cases is cancellable.

Once the particle meg appears in the predicate, however, which, as we argue above, occupies [Spec, AspP], telicity is not cancellable. The representation of (59) is given in (60).

In light of this, a question arises regarding the English data: Why is it that English creation/consumption predicates like drink a lemonade and build a house, which contain a theme with quantized reference and no verbal particle, are preferably telic? Borer’s (Reference Borer2005) answer to this question is that such predicates are associated with a quantity structure and thus they are telic, whereas according to Travis’s (Reference Travis2010: 261–262) analysis of these and other similar data, the telicity of these predicates is due to a zero telicity marker in the complement of the lower VP. However, this position can also be filled, as in the case of resultative constructions like that in (61).

In Hungarian, by contrast, we argue that non-cancellable telicity is due to verbal particles like meg and result predicates, among other aspectual markers, which exert their telicity-marking function in a position higher than VP (i.e., in [Spec, AspP]).

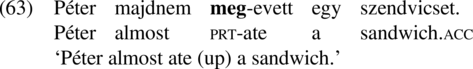

Finally, it is important to note that Hungarian predicates whose telicity is an implicature, as shown above, are associated with a simple event structure. This is evidenced by their non-ambiguous counterfactual reading when they appear with the adverb majdnem ‘almost’ (Piñón Reference Piñón and Kiss2008: 92).

The example above can only receive a single reading in which the adverb majdnem ‘almost’ has wide scope and modifies the whole event such that Péter did not begin eating a sandwich. The incompletive reading such that Péter did not finish eating a sandwich is not readily available. Once the verbal particle meg appears in the sentence, however, both readings become available (Piñón Reference Piñón and Kiss2008: 93).

The predicate in (63) can either mean that Péter did not even begin eating a sandwich (counterfactual interpretation) or that he began eating a sandwich but did not finish it (incompletive interpretation). Likewise, the predicate majdnem fel-épített egy házat ‘almost prt-built a house’ is ambiguous, as illustrated by the examples below:

As shown above, majdnem fel-épített egy házat ‘almost prt-built a house’ is compatible with a scenario in which Péter did not even begin building a house and also with one in which he began building a house but failed to finish it. If we take event structural facts to be reflected in the syntax, as argued by Borer (Reference Borer2005) and also discussed in Section 4.1, the data in (64) can be regarded as evidence for a more complex syntactic structure associated with these predicates. However, in light of this discussion and that of egyet-type marking elements in Section 4.2 (see example (51)) we conclude that both telicity and event maximality seem to be necessary for a complex-event interpretation.

5. Some co-occurrence restrictions in the event domain

After giving an analysis of three classes of telicity marking strategies in Hungarian, in this section of the paper we discuss two consequences of the analysis by focusing on various co-occurrence restrictions pertaining to inner aspectual marking elements.

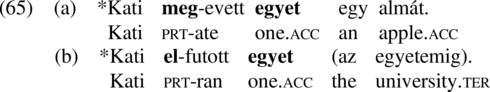

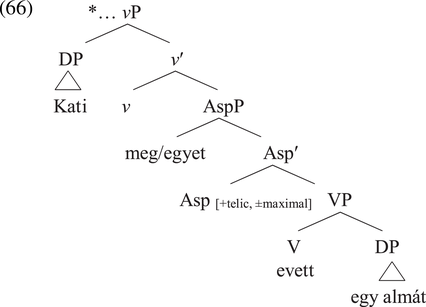

The first prediction of our analysis is that VPrts like meg and el and POs cannot co-occur in the same verbal predicate because they compete for the same position in the Hungarian sentence, with [Spec, AspP] being the merged position of these elements. This is confirmed by the ungrammaticality of the following examples (see also Csirmaz Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008b), with (65a) represented in (66).

Resultative predicates like that in (67) are also expected to be ungrammatical with egyet ‘one.acc’ in them, since although result predicates are assumed to be merged as complements in VP, whereas POs are merged in [Spec, AspP], they are associated with the features [+maximal] and [−maximal], respectively. This causes a maximality conflict in the sentence.Footnote 19

Crucially, the complementary distribution of POs and VPrts only applies to separable VPrts which are associated with the [+telic] and [+maximal] features. As shown in Hegedűs & Dékány (Reference Hegedűs, Dékány, Lipták and van der Hulst2017) and also discussed earlier in our paper, particle verbs may also be associated with an inseparable particle, where the particle appears in the immediately preverbal position in both neutral (68a) and non-neutral (68b) sentences (e.g. declaratives with negation).

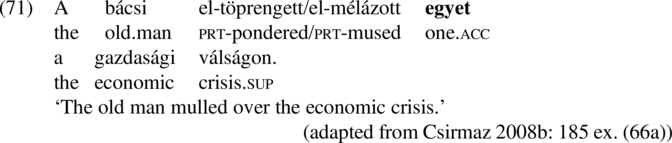

If the assumption of Hegedűs & Dékány (Reference Hegedűs, Dékány, Lipták and van der Hulst2017) that inseparable particles are merged low is correct and our claim that POs are merged in [Spec, AspP] is also correct, inseparable particle verbs should be compatible with POs. This is borne out in (69):

We also believe that there is evidence for particles like szét to be merged in [Spec, AspP] when they are attached to inseparable particle verbs like felvételizik ‘take an entrance exam’ as the particle szét turns the base predicate, which is atelic, into a telic one.Footnote 20

Moreover, POs can also co-occur with separable particles that do not have a telicizing function, as shown below.Footnote 21

Contra Csirmaz (Reference Csirmaz and Kiss2008b: 185), who rules out the above sentence and argues that POs can never appear with particles, independently of the aspectual contribution of the latter, we consider such sentences to be fully acceptable. As in such and similar cases the particle does not make the predicate telic, it is arguably located in a different position than [Spec, AspP] and the PO enters the syntax in [Spec, AspP].

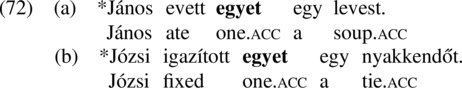

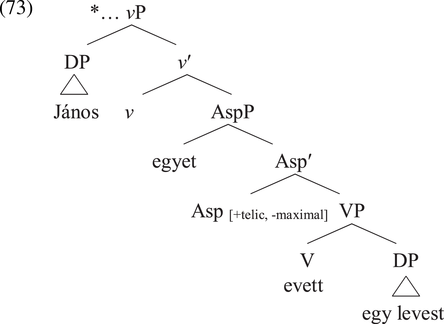

Another significant co-occurrence restriction is one pertaining to POs and accusative DP arguments, and is illustrated below:

What is puzzling about the examples above is that although POs and thematic objects are argued in our analysis to occupy different positions in the syntax (and hence they do not compete for the same syntactic position, as shown below), the examples in (72a) and (72b) are ungrammatical.

We believe that this has to do with how (accusative) case assignment and inner aspect interact in Hungarian. On the one hand, we have already noted in Section 4.1 that in the presence of event-maximizing verbal particles like meg, merged in [Spec, AspP], the assignment of accusative case to the internal theme argument becomes obligatory; see the following examples, repeated from Section 4.1:

Conversely, in the absence of an event-maximizing verbal particle like meg, the theme may receive accusative case (e.g. egy almát ‘an apple.acc’) or elative case (e.g. egy almából ‘an apple.ela’).

On the other hand, the incompatibility of POs and accusative theme DPs is assumed to be a consequence of the theme DP’s inability to get accusative case from v since egyet ‘one.acc’ intervenes between v and the theme DP.Footnote 22 By contrast, non-accusative theme DPs can appear in the presence of egyet-POs, as evidenced by the following examples:

Finally, we find it important to reiterate that there is no one-to-one correspondence between case and inner aspect in Hungarian: accusative case and the boundedness of the theme alone will not give rise to telicity in the case of the majority of verbal predicates, contra what we often see in English and other similar languages (see Section 4.1). Telicity is guaranteed in the presence of aspectual markers contributing to the aspectual interpretation of the sentence once they merge in the syntax due to the presence of AspP in the event domain.

6. Conclusion

In this paper we have analysed the syntax of inner aspect in Hungarian by attributing the event aspectual interpretations associated with three classes of telicity-marking elements to the syntactic configuration characterizing these elements. We have proposed, building on much recent literature on inner aspectual markers in Hungarian, that, (i) similarly to many other languages, Hungarian has a vP-internal aspectual projection, AspP, which is directly responsible for non-cancellable telicity effects induced by verbal particles, result predicates and non-subcategorized pseudo-objects, and (ii) telicity may also obtain in the presence of bounded themes in the class of creation/consumption predicates. As opposed to the previous case, where telicity is an entailment, telicity in this latter case is an implicature and so it is cancellable. Our analysis has also allowed us to make some predictions about the co-occurrence restrictions pertaining to POs and verbal particles as well as result predicates, and we have also made some important observations about how inner aspect and case interact in Hungarian.