Introduction

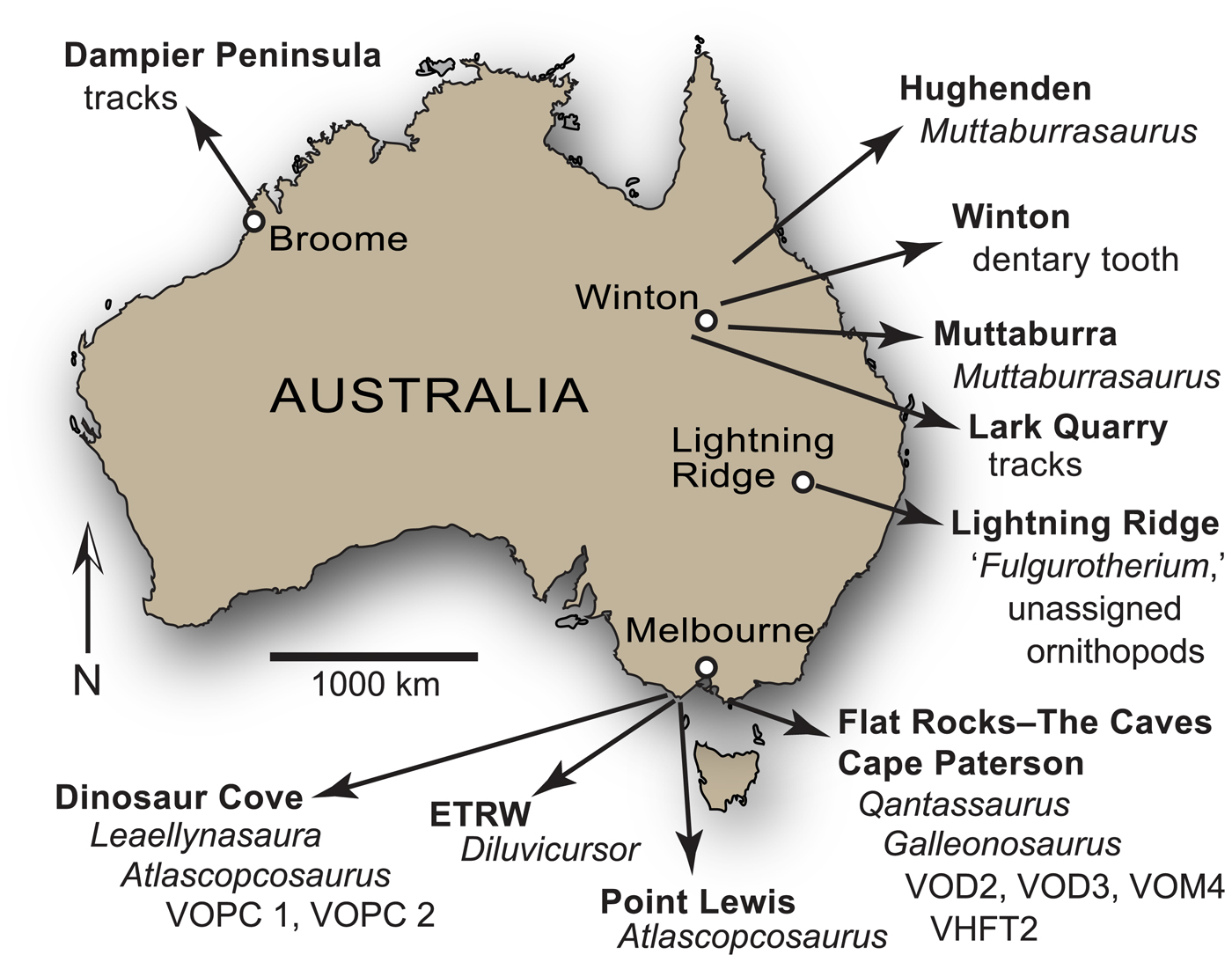

A rich assemblage of isolated body fossils and rare associated skeletal remains of small-bodied ornithopods has been recovered from Early Cretaceous rocks of the Australian-Antarctic rift system, strata of which crop out in sea cliffs and wave-cut shore platforms along the southern coast of Victoria, southeastern Australia (Fig. 1.1, 1.2). Four small-bodied ornithopods have been named from this region, including Atlascopcosaurus loadsi Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989, Leaellynasaura amicagraphica Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989, and Diluvicursor pickeringi Herne et al., Reference Herne, Tait, Weisbecker, Hall, Nair, Cleeland and Salisbury2018, all of which are from the lower Albian of the Eumeralla Formation in the Otway Basin (Fig. 1.2); and Qantassaurus intrepidus Rich and Vickers-Rich, Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999 from the Wonthaggi Formation in the Gippsland Basin (Fig. 1.2), which has been considered Valanginian–middle Barremian in age (Wagstaff and McEwen Mason, Reference Wagstaff and McEwen Mason1989). Of these four taxa, Atlascopcosaurus loadsi, L. amicagraphica, and Q. intrepidus are known from craniodental remains, whereas Diluvicursor pickeringi is known from a partial postcranium.

Figure 1. Maps of Australia, southern Victoria and Gondwana: (1) present-day eastern Australia indicating region of interest; (2) inset from (1) showing upper Barremian–lower Albian ornithopod localities and associated geology; (3) reconstruction of Gondwana during the late Barremian (~ 125 Ma) using GPlates (www.gplates.org). Dashed lines in (2) indicate basin boundaries. Geological information in (2) based on Bryan et al. (Reference Bryan, Constantine, Stephens, Ewart, Schon and Parianos1997, Reference Bryan, Ewart, Stephens, Parianos and Downes2000). V-shaped symbols in (3) indicate direction and position of plate subduction, based on Wandres and Bradshaw (Reference Wandres and Bradshaw2005). Australian paleoshoreline in (3) based on Heine et al. (Reference Heine, Yeo and Müller2015). Dashed arrows in (2–3) indicate paleoflow direction. AAR = Australian-Antarctic rift; AF = Africa; AN = Antarctica; AU = Australia; I = India; EF = Eumeralla Formation; ES = epeiric Eromanga Sea (in region of Eromanga Basin); ETRW = Eric the Red West; M = Madagascar; NC = New Caledonia; NZ = New Zealand; SA = South America; VHFT2 = Victorian Hypsilophodontid Femur Type 2; VOPC1 = Victorian ornithopod postcranium 1 (NMV P185992/P185993); VOPC2 = Victorian ornithopod postcranium 2 (NMV P186047); W = Whitsunday Large Siliceous Igneous Province (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Constantine, Stephens, Ewart, Schon and Parianos1997); WF = Wonthaggi Formation.

In addition to the named Victorian taxa, several isolated femora from the Eumeralla and Wonthaggi formations were referred to Fulgurotherium australe von Huene, Reference von Huene1932 (Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989; Rich and Vickers-Rich, Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999), a femoral-based taxon from the Albian Griman Creek Formation in the Lightning Ridge region of northern New South Wales (Molnar and Galton, Reference Molnar and Galton1986). However, Fulgurotherium australe has been reassessed as a nomen dubium (Agnolin et al., Reference Agnolin, Ezcurra, Pais and Salisbury2010). Another femur (NMV P156980) collected from Cape Paterson in the Wonthaggi Formation (Fig. 1.2), approximately double the size of the largest Victorian femora assigned to Fulgurotherium australe (see Rich and Vickers-Rich, Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999; Herne, Reference Herne2014), was informally termed ‘Victorian Hypsilophodontid Femur Type 2’ (Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989).

Excavated at the Slippery Rock site at the fossil vertebrate locality of Dinosaur Cove (Fig. 1.2), the holotype of Leaellynasaura amicagraphica (NMV P185991) comprises a left-side cheek fragment of a juvenile individual, including the maxilla (Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989) but lacks a dentary. A cranial table (NMV P185990) and two partial postcranial specimens (NMV P185992, P185993; confirmed as belonging to a single individual; Herne, Reference Herne2009; Herne et al., Reference Herne, Tait and Salisbury2016, fig. 5) were originally referred to L. amicagraphica, as scattered parts of the holotypic individual (Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989; Rich and Vickers-Rich, Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich2000). However, these referrals have also been questioned (Herne et al., Reference Herne, Tait and Salisbury2016). For this reason, the referrals of several isolated femora and another partial postcranium (NMV P186047) to L. amicagraphica from Dinosaur Cove (sensu Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989; Rich and Vickers-Rich, Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999; Rich et al., Reference Rich, Galton and Vickers-Rich2010) have also been questioned (Herne et al., Reference Herne, Tait and Salisbury2016).

Discovered at the locality of Point Lewis in the Eumeralla Formation (Fig. 1.2), the holotype of Atlascopcosaurus loadsi (NMV P166409) consists of a partial left maxillary fragment. In addition to the Atlascopcosaurus loadsi holotype, another left maxillary fragment from Point Lewis (NMV P157390), as well as a left maxillary fragment (NMV P157970) and several isolated maxillary teeth from Dinosaur Cove, were also referred to the taxon. Two isolated dentary fragments (NMV P182967, P186847) and two isolated dentary teeth (notably NMV P177934) were also referred to Atlascopcosaurus loadsi (Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989; see also Herne et al., Reference Herne, Tait and Salisbury2016). However, because none of these Atlascopcosaurus loadsi-referred dentary and dentary tooth specimens were found in association with a maxilla, we consider these assignments inconclusive.

Discovered at the locality of Eric the Red West in the Eumeralla Formation (Fig. 1.2), Diluvicursor pickeringi comprises the holotypic partial hind-region postcranium (NMV P221080) and a referred, isolated caudal vertebra (Herne et al., Reference Herne, Tait, Weisbecker, Hall, Nair, Cleeland and Salisbury2018). With future discoveries, this taxon could be found synonymous with any one of the Victorian taxa previously named from craniodental remains. However, the significance of Diluvicursor pickeringi as a rare, articulated Australian ornithopod skeleton, clearly differing from two other partial postcrania from the Eumeralla Formation (i.e., NMV P185992/P185993, P186047), were considered by Herne et al. (Reference Herne, Tait, Weisbecker, Hall, Nair, Cleeland and Salisbury2018) as justification for erecting the taxon.

Discovered during excavations at the Flat Rocks site in the Wonthaggi Formation (Figs. 1.2, 2), Qantassaurus intrepidus is known from the three isolated dentaries (Rich and Vickers-Rich, Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999)—that of the holotype (NMV P199075) and two additional specimens (NMV P198962, P199087). Originally referred to Hypsilophodontidae, the Q. intrepidus dentary was diagnosed by a combination of three features: possession of 10 cheek teeth; foreshortened morphology; and anteriorly convergent dorsal and ventral margins (sensu Rich and Vickers-Rich, Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999). Agnolin et al. (Reference Agnolin, Ezcurra, Pais and Salisbury2010) reassessed Q. intrepidus as a nondryomorphan ornithopod, agreeing that the foreshortened dentary with anteriorly convergent alveolar and ventral margins presented a combination of features that distinguished Q. intrepidus from other ornithopods.

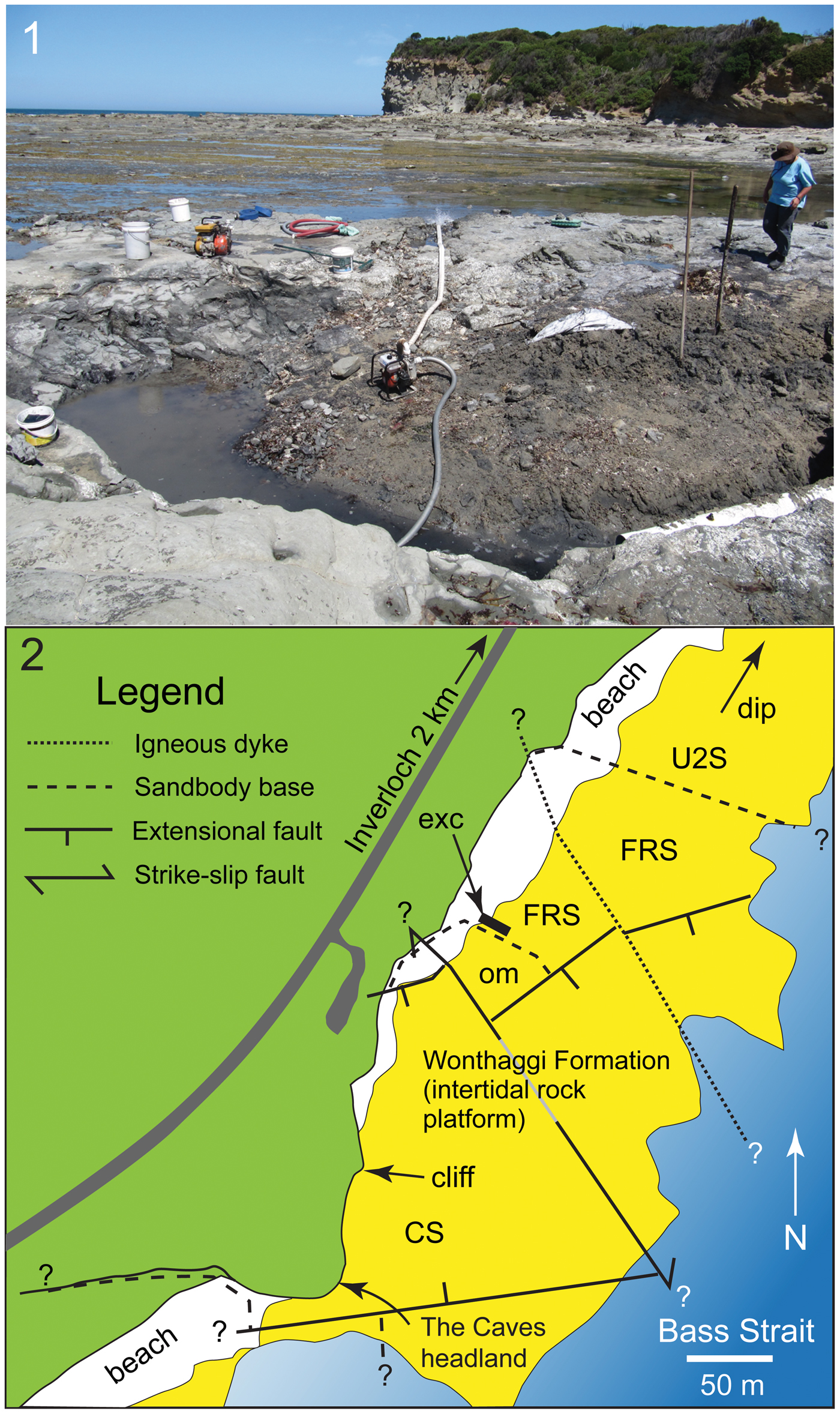

Figure 2. Flat Rocks locality in the Bunurong Marine National Park of the Strzelecki region, Victoria, southeastern Australia: (1) view looking southwest showing the Flat Rocks excavation (foreground), wave eroded rock platform (midground), and The Caves headland (background), which is ~ 230 m southwest of the Flat Rocks excavation; (2) map showing site positions, topographic and geostructural features, and estimated boundaries of sandstone units. ? = unknown extension of feature; CS = The Caves Sandstone; exc = excavations; FRS = Flat Rocks Sandstone; om = overbank mudstone; U2S = Unit 2 Sandstone.

A plethora of isolated body fossils have been collected from the Flat Rocks site, which among the dinosaur materials, some have been identified as ankylosaurian, avian, and nonavian theropodan bones and teeth (Close et al., Reference Close, Vickers-Rich, Trusler, Chiappe, O'Connor, Rich, Kool and Komarower2009; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Rich, Vickers-Rich, Tumanova, Inglis, Pickering, Kool and Kear2010; Benson et al., Reference Benson, Rich, Vickers-Rich and Hall2012; see also Poropat et al., Reference Poropat, Martin, Tosolini, Wagstaff, Bean, Kear, Vickers-Rich and Rich2018). However, Qantassaurus intrepidus has been the only ornithopod named from the Wonthaggi Formation. The partial maxilla of an ornithopod (NMV P186440) was further reported by Rich and Vickers-Rich (Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999) from a cliffed coastal headland site called The Caves ~200 m from the Flat Rocks excavations (Figs. 1.2, 2). However, Rich and Vickers-Rich (Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999) were uncertain whether NMV P186440 was assignable to Atlascopcosaurus loadsi or Q. intrepidus. In this investigation, we describe new craniodental materials of ornithopods from the Flat Rocks locality (=Flat Rocks and The Caves sites), revise Q. intrepidus, reassess the diversity and phylogenetic relationships of the Victorian ornithopods, and update the distribution of Australian ornithopods.

Geological setting

Most of the specimens of interest to this investigation were collected from the Flat Rocks site (=Dinosaur Dreaming Field Site; Seegets-Villiers, Reference Seegets-Villiers2012), which consists of a series of ~1 m deep excavations on the coastal, wave-eroded rock platform within the Bunurong Marine National Park, 2.2 km southwest of the town of Inverloch in Victoria, southeastern Australia (38.660792°S, 145.681009°E, GDA94 [Intergovernmental Committee on Surveying and Mapping, 2014]; Seegets-Villiers, Reference Seegets-Villiers2012), ~112 km southeast of the city of Melbourne (Figs. 1–2). One additional specimen (NMV P186440; reported by Rich and Vickers-Rich, Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999) discovered in a large boulder that had fallen from the sea cliff at The Caves (38.662792°S, 145.680108°E, Map Grid of Australia, 1994; see also Kool, Reference Kool2010, p. 60), ~230 m southwest of the Flat Rocks site (Figs. 1.2, 2) is also of interest to this study. The Flat Rocks site is located within the undifferentiated upper section of the Strzelecki Group in the Gippsland Basin (see Tosolini et al., Reference Tosolini, Mcloughlin and Drinnan1999), which has been informally termed the Wonthaggi Formation (Constantine and Holdgate, Reference Constantine and Holdgate1993; see also Chiupka, Reference Chiupka1996), the name used herein (Fig. 1.2).

The predominantly volcanogenic sediments of the Wonthaggi and Eumeralla formations (Fig. 1.2) in the Gippsland and Otway basins, respectively, were deposited during the Early Cretaceous as thick (to 3,000 m) depocenters within the extensional rift valley that formed between Australia and Antarctica, coinciding with the fragmentation of Gondwana (Willcox and Stagg, Reference Willcox and Stagg1990; Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Constantine, Stephens, Ewart, Schon and Parianos1997; Tosolini et al., Reference Tosolini, Mcloughlin and Drinnan1999; Hall and Keetley, Reference Hall and Keetley2009). The Gippsland and Otway basins, however, are most likely a single basin system (VandenBerg et al., Reference VandenBerg, Cayley, Willman, Morand, Seymon, Osborne, Taylor, Haydon, McLean, Quinn, Jackson and Sandford2006). The sediments were sourced from the Whitsunday Silicic Large Igneous Province (WSLIP) that was situated along the eastern margin of the Australian Plate (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Constantine, Stephens, Ewart, Schon and Parianos1997; Bryan, Reference Bryan2007; Fig. 1.3). In addition, quartzose grit and gravel admixtures were sourced from older basement rocks that formed the rift margins (based on Felton, Reference Felton1997). The Wonthaggi Formation has been described as comprising multistorey sheet-flood to braided river-like fluvial channel complexes to 200 m thick, interspersed with overbank sequences up to 100 m thick (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Constantine, Stephens, Ewart, Schon and Parianos1997). However, new research (unpublished data, Tait, Hall, and Herne, 2018) further suggests that the Wonthaggi and Eumeralla formations could be the product of a large-scale meandering river system with associated vegetated flood plains.

Sediments at the Flat Rocks site (Fig. 2) comprise interbedded volcaniclastic sandstones and mudstone conglomerates within the basal meter of a fluvial sandbody ~24 m thick (see also Seegets-Villiers, Reference Seegets-Villiers2012). This sandbody is hereafter termed the ‘Flat Rocks Sandstone.’ The erosive base of the Flat Rocks Sandstone has a relief of ~0.5 m at the dig site, cut into thinly interbedded mudstones and very fine-grained sandstones, thin coals, and paleosols with in situ tree stumps deposited on a fluvial floodplain (see also Seegets-Villiers, Reference Seegets-Villiers2012). The fossil-bearing sandstones and conglomerates also contain copious fossilized plant fragments up to small log-sized, which are now coalified and flattened, as well as contemporaneous charcoal (see also Seegets-Villiers, Reference Seegets-Villiers2012). The mudstone clasts range to cobble-size and include pale gray types, lithologically identical to the paleosol mudstones, and pale brown types thought to represent riverbank or abandoned channel deposits. The brown mudstone contains freshwater bivalve shell fossils, including two unionoidean species (Thompson and Stilwell, Reference Thompson and Stilwell2010). The bedding within the sandbody becomes thinner upward and the grain size becomes finer starting from medium to coarse sand at the unit base. Thus, the Flat Rocks Sandstone is potentially a single storey unit deposited by lateral accretion of a meandering river >24 m deep (considering postdepositional compaction). The fossil-bearing sediments were deposited as bedload by high-speed flow at the base of the river, with the alignment of elongate plant fragments and prograding bedforms indicating a local current direction toward ~240° (sensu Seegets-Villiers, Reference Seegets-Villiers2012, fig. 2.12). The boulders at the foot of the cliffed headland site (The Caves; Fig. 2) result from undercutting of the cliff by waves, or from weathering. The sandstone at The Caves could be a down-faulted section of the Flat Rocks Sandstone, although this assessment has yet to be verified. However, for the purposes of this investigation, we informally term the unit in this region ‘The Caves Sandstone’ (Fig. 2).

Detailed taphonomic investigation of the fossil vertebrate remains from the Flat Rocks site was conducted by Seegets-Villiers (Reference Seegets-Villiers2012). The specimens consist of isolated, reworked, multispecific whole bones and bone fragments that accumulated under conditions of in-channel hydraulic flow on low-angle prograding bedforms on the channel floor. Many bones from the locality had been subject to surficial weathering, possibly including heating and charring by fire (Seegets-Villiers, Reference Seegets-Villiers2012). Various degrees of in-channel abrasion suggest the bones differed in periods of transport, with some undergoing multiple stages of reworking (Seegets-Villiers, Reference Seegets-Villiers2012). Thus, the accumulation can be considered time-averaged (e.g., Behrensmeyer, Reference Behrensmeyer1982). Most of the vertebrate fossils in this deposit comprise disassociated bones and bone fragments. However, NMV P186440—collected at The Caves site and reported by Rich and Vickers-Rich (Reference Rich and Vickers-Rich1999, fig. 2) as a maxilla—constitutes an associated cranial fragment, rarely found in Victoria.

Palynological work previously suggested that the region of the Wonthaggi Formation encompassing the Flat Rocks locality was middle Valanginian–middle Barremian in age (following Wagstaff and McEwen Mason, Reference Wagstaff and McEwen Mason1989). However, renewed palynological investigations (personal communication, B. Wagstaff, 2018) suggest that the Flat Rocks locality falls within the upper part of the Foraminisporis wonthaggiensis (Cookson and Dettmann, Reference Cookson and Dettmann1958) spore-pollen zone of Helby et al. (Reference Helby, Morgan and Partridge1987), indicating a late Barremian age (~125–127.2 Ma, following Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Finney, Gibbard and Fan2013). Using GPlates (v. 2.0.0; www.gplates.org), the position of the Flat Rocks locality at 125 Ma is estimated at ~72°S, 119°E (Fig. 1.3).

Materials and methods

Craniodental remains of ornithischians from the collections of Museums Victoria (NMV) and other comparative materials (Table S1) were examined first-hand in this investigation, from which new assignments were made and the diversity and phylogenetic relationships of the Victorian ornithopods were revised. The specimens were documented using digital photography, vernier callipers, and a microscope-mounted camera-lucida attachment. New NMV specimens were mechanically prepared (by L. Kool, Monash University, and D. Pickering, Museums Victoria). Additional anatomical data and imagery for the maxilla NMV P229196 utilized micro-Computed Tomography (μCT) scans (Zeiss Xradia XRM Versa520 X-Ray Microtomography: voxel size 45.61 µm; power 10 W; voltage 140 kV). The scans were digitally modelled and volume-rendered using Avizo software, v. 9 (FEI, Berlin). The production of figures utilized Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop software, CS4 (www.adobe.com). Nomenclature for the dentition used in the Systematic paleontology section and phylogenetic dataset is outlined in Figure 3 and Table 1. The phylogenetic relationships of the Australian taxa of interest were hypothesized from a cladistic analysis using TNT 1.5 (Goloboff and Catalano, Reference Goloboff and Catalano2016). The Systematic paleontology section follows the phylogenetic framework resulting from the cladistic analysis, and referrals in open nomenclature follow the criteria of Bengston (Reference Bengston1988). The phylogenetic definitions of clades predominantly follow Madzia et al. (Reference Madzia, Boyd and Mazuch2018; see Text S1) and the relative stratigraphic ages of taxa of interest are provided in Text S1.

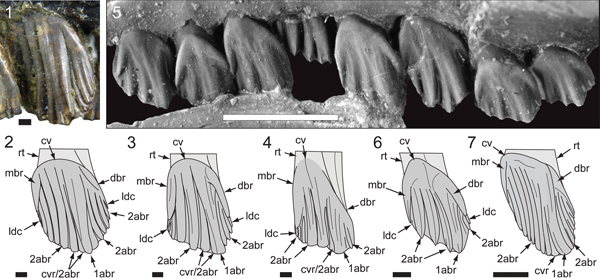

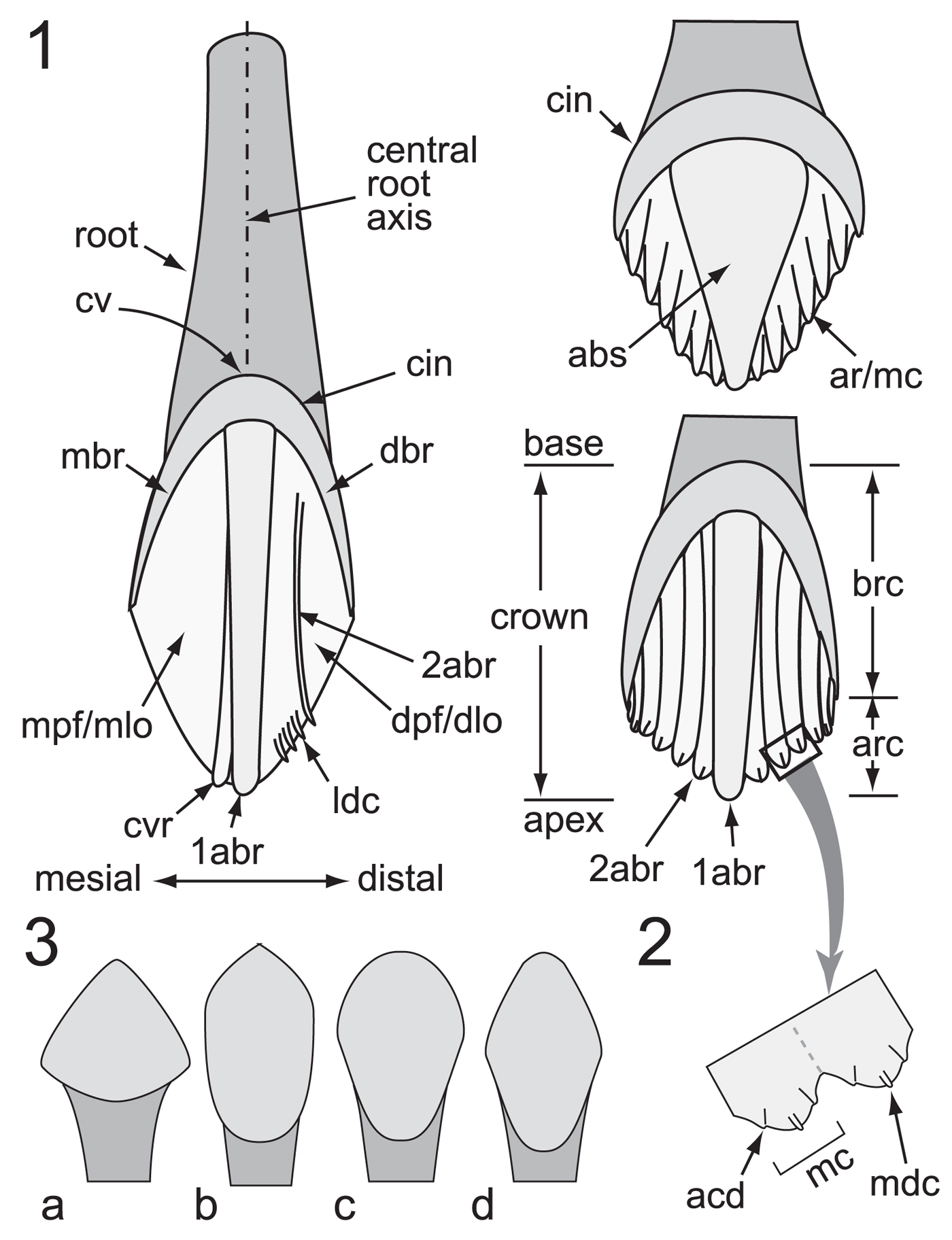

Figure 3. Ornithischian dental nomenclature: (1) crown ornamentation features; (2) portion of crown surface indicated by large arrow in (1), showing location of accessory denticles relative to the median denticle on the apical cusp (typically lingual maxillary and labial dentary faces); (3) variation in crown shape: subtriangular (a), urn-shaped (b), spatulate (c), and rhomboidal/lanceolate (d). 1abr = primary apicobasal ridge; 2abr = secondary apicobasal ridge; abs = apicobasal swelling; acd = accessory denticle; ar = apical ridge; arc = apical region of crown; brc = basal region of crown; cin = cingulum (= dbr + mbr); cv = cingular vertex; cvr = convergent (accessory) ridge; dbr = distal bounding ridge; dlo = distal lobe; dpf = distal paracingular fossa; ldc = lingulate denticle; mbr = mesial bounding ridge; mc = mamillated cusp; mdc = median denticle; mlo = mesial lobe; mpf = mesial paracingular fossa.

Table 1. Terminology used for ornithischian cheek tooth crown descriptions.

Repository and institutional abbreviations

CD = New Zealand Geological Survey Collection, Lower Hutt, New Zealand; CM = Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA; MB.R. = Collection of Fossil Reptilia, Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany; MCF-PVPH = Museo Carmen Funes-Paleontología de Vertebrados, Plaza Huincul, Neuquén Province, Argentina; MUCPv = Museo de Geologia y Paleontologia de la Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Paleontologia de Vertebrados, Neuquén Province, Argentina; NMV = Museums Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; NHMUK = The Natural History Museum, London, UK; QM = Queensland Museum, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; RBINS = Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Belgium; SAM-PK = South African Museum (Karoo Palaeontology collection), Cape Town, South Africa; UBB = Catedra de Geologie, Facultatea de Biologie şi Geologie, Universitatea din Babes-Bolyai, Cluj-Napoca, Romania; YPM VP = Yale Peabody Museum (Vertebrate Paleontology), New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Systematic paleontology

Dinosauria Owen, Reference Owen1842

Ornithischia Seeley, Reference Seeley1888

Neornithischia Cooper, Reference Cooper1985

Cerapoda Sereno, Reference Sereno1986

Ornithopoda Marsh, Reference Marsh1881

Genus Galleonosaurus new genus

Type species

Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., by monotypy.

Diagnosis

As for the type species.

Etymology

From galleon (Latinization of the English for a type of large sailing ship) + saurus (New Latin from the Greek sauros for lizard), in reference to the appearance of the maxilla to the upturned hull of a galleon.

Occurrence

Flat Rocks locality in the Inverloch region of Victoria, southeastern Australia (Fig. 1); Flat Rocks Sandstone and The Caves Sandstone, upper Barremian of the Wonthaggi Formation in the Gippsland Basin.

Remarks

Prior to the recognition of Galleonosaurus n. gen., Atlascopcosaurus loadsi and Leaellynasaura amicagraphica were the only Victorian ornithopods identified from maxillary remains (Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989). The maxillae of Atlascopcosaurus loadsi are highly incomplete and the only known maxilla of L. amicagraphica (that of the holotype, NMV P185991) is damaged, and due to its diminutive size, difficult to study. The maxillae of Galleonosaurus n. gen., as well as the complete palatine and fragment of the lacrimal, now provide new information from which the anatomy of the other Victorian ornithopods can be better understood. The holotype of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (NMV P229196) represents the most complete maxilla of a dinosaur currently known from Victoria.

Galleonosaurus dorisae new species

Figures 4–8, 10–13, 15–16, 17.4; Table 2

Figure 4. Specimens of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. from the Flat Rocks Sandstone in the upper Barremian, Wonthaggi Formation, Gippsland Basin, southeastern Australia: (1–2) holotype (NMV P229196), left maxilla in lateral (1) and medial (2) views; (3) NMV P208178, left maxilla in lateral view; (4) NMV P212845, left maxilla in lateral view; (5) NMV P209977, left maxilla in lateral view; (6) NMV P186440, left maxilla in lateral view; (7) NMV 208113, right maxillary tooth in labial view. Scale bars = 10 mm (1–6); 1 mm (7).

Figure 5. Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., digital 3D models of holotypic left maxilla (NMV P229196), derived from μCT scans in dorsal (1), lateral (2), medial (3), ventral (4), posterior (5), and anterior (6) views. Dashed arrow in (1) indicates line of neurovascular tract and posterodorsal foramen. alf = anterolateral fossa; alv = alveolus; aof = antorbital fossa; ap = anterior (premaxillary) process; asr = ascending ramus of maxilla; avp = anteroventral process; bur = buccal ridge; dmt = dorsal maxillary trough; eaof = region of external antorbital fossa; epf = ectopterygoid flange; for = foramen; iaof = region of internal antorbital fossa; js = jugal shelf; lpf = sutural flange for the lateral palatine ramus; m# = maxillary tooth position (from anterior end) and replacement number; mfo = anterior maxillary foramina; ml = medial lamina; mpf = medial palatine facet; mra = maxillary ramus; nuf = nutrient foramen; nvf = neurovascular foramen; plp = posterolateral process; pmp = posteromedial process; rid = ridge (crista); sal = supralveolar lamina; sgj, sutural grove for jugal; vgv = vomer groove. Scale bar increments = 5 mm.

Figure 6. Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (NMV P186440), left cranial fragment in dorsal (1), ventral (2), lateral (3), medial (4), medial (5, bottom lighting), and anterior (6) views, and schematics (7–11) of (1–4, 6), respectively. Specimen has been ammonium chloride coated. Dashed arrow in (7) indicates line of neurovascular tract and posterodorsal foramen. alv = alveolus; aof = antorbital fossa; bur = buccal ridge; cem = cementum; cho = choana; epf = ectopterygoid flange; lac = lacrimal; m#’ = maxillary tooth position (from posterior end) and replacement number; mfos = muscular fossa; mgv = medial groove; mra = maxillary ramus; nuf = nutrient foramen; nvf = neurovascular foramen; nvt = neurovascular tract; pfos = pneumatic fossa; plf = palatine lateral flange; plp = posterolateral process; plr = palatine lateral ramus; pmal = palatine medial ala; pmf = palatine maxillary flange; pmp = posteromedial process; sal = supralveolar lamina; sgj = sutural grove for jugal; sul = sulcus on lacrimal fragment. Scale bars = 10 mm.

Figure 7. Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (NMV P209977), left maxillae and schematics in ventral (1), dorsal (2), lateral (3), and medial (4) views. Dashed lines in (2) indicate approximate margins of the palatine facet. alf = anterolateral fossa; alv = alveolus; aof = antorbital fossa; ap = anterior (premaxillary) process; asr = ascending ramus of maxilla; avp = anteroventral process; bur = buccal ridge; dalv = developing alveolus; dmt = dorsal maxillary trough; epf = ectopterygoid flange; gv = groove; iaof = region of internal antorbital fossa; lpf = sutural flange for the lateral palatine ramus; lprf = facet for the lateral ramus of the palatine; m# = maxillary tooth position (from anterior end) and replacement number; ml = medial lamina; mpf = medial palatine facet; mra = maxillary ramus; nuf = nutrient foramen; nvf = neurovascular foramen; nvt = neurovascular tract; plp = posterolateral process; pmp = posteromedial process; pro = protuberance; sal = supralveolar lamina; sep = septum; sgj = sutural grove for jugal; sl = slot; sml = sutural margin for lacrimal; vgv = vomer groove. Scale bars = 10 mm.

Figure 8. Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (NMV P212845), left maxillae and schematics in ventral (1), dorsal (2, 3), dorsolateral (4), lateral (5), and medial (6) views. Specimen in (3) has been ammonium chloride coated; dashed line in schematic indicates presumed internal path of the neurovascular tract. alf = anterolateral fossa; alv = alveolus; aof = antorbital fossa; ap = anterior (premaxillary) process; asr = ascending ramus of maxilla; avp = anteroventral process; bur = buccal ridge; dmt = dorsal maxillary trough; epf = ectopterygoid flange; iaof = region of internal antorbital fossa; lpf = sutural flange for the lateral palatine ramus; lprf = facet for the lateral ramus of the palatine; m# = maxillary tooth position (from anterior end) and replacement number; ml = medial lamina; mra = maxillary ramus; nuf = nutrient foramen; nvf = neurovascular foramen; nvt = neurovascular tract; plp = posterolateral process; sal = supralveolar lamina; sep = septum; sgj = sutural grove for jugal; vgv = vomer groove. Scale bar = 10 mm.

Figure 9. Camptosaurus dispar Marsh, Reference Marsh1879, left maxilla and schematics (YPM VP 1886) in dorsal (1) and ventral (2) views. Dashed arrow in (1) indicates presumed dorsal path of the neurovascular tract; dashed lines indicate approximate margins of the palatine facet. alv = alveolus; aof = antorbital fossa; ap = anterior (premaxillary) process; asr = ascending ramus; avp = anteroventral process; bur = buccal ridge; epf = ectopterygoid flange; js = jugal shelf; lprf = sutural flange for the lateral palatine ramus; m# = maxillary tooth position (from anterior end) and replacement number; ml = medial lamina; mpf = medial palatine facet; mra = maxillary ramus; nuf = nutrient foramen; plp = posterolateral process; pmg = premaxillary groove; pmp = posteromedial process; pro = protuberance; rid = ridge; sal = supralveolar lamina; sut = sutural margin. Scale bars = 50 mm. Image (1) by A. Heimer, courtesy of YPM. Image (2) by S. Hochgraf, courtesy of YPM.

Figure 10. Comparisons of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp.: (1–4) schematics of holotype of G. dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (NMV P229196) (1), G. dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (NMV P209977) (2), Atlascopcosaurus loadsi Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989 (NMV P157390) (3), and original Atlascopcosaurus loadsi holotype (NMV P166409) (4), posterior maxillary regions in ventral view, showing extent of the posteromedial processes; (5) schematic of holotypic maxilla of Leaellynasaura amicagraphica Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989 (NMV P185991) in ventral view showing shapes of the alveolar and posterior margins; (6, 7) illustration of G. dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (NMV P186440) (6) and cast of the original Atlascopcosaurus loadsi holotype (NMV P166409) (7) in dorsal view, with schematics showing difference in the shape of the lateral palatine rami/sutural facets. alv = alveolus; aof = antorbital fossa; bur = buccal ridge; cho = choana; epf = ectopterygoid flange of maxilla; lpf = lateral palatine flange on maxilla; lprf = facet for the lateral ramus of the palatine; m# = maxillary tooth position (from anterior end) and replacement number; m#’ = maxillary tooth position (from posterior end) and replacement number; mfos = muscular fossa on palatine; mpal = medial palatine ala; mpf = facet for medial palatine flange on maxilla; mra = maxillary ramus; nvt = neurovascular tract; pfos = pneumatic fossa on palatine; plp = posterolateral process; plf = palatine lateral flange; plr = palatine lateral ramus; pmp = posteromedial process; sal = supralveolar lamina; sgj = sutural grove for jugal. Scale bars = 10 mm.

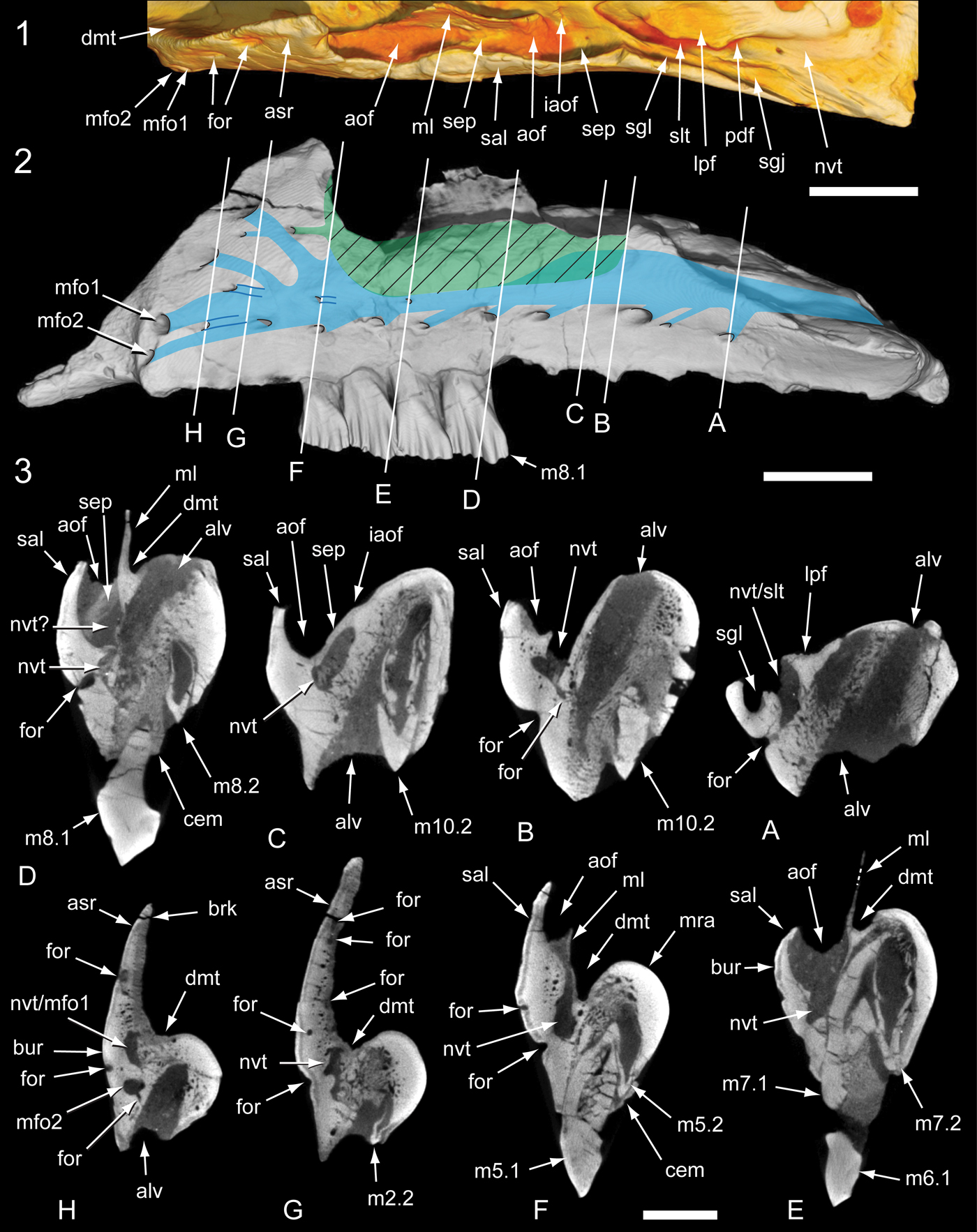

Figure 11. Internal anatomy of the Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. holotypic left maxilla (NMV P229196) from μCT scans: (1) antorbital region in dorsal view; (2) maxilla in lateral view with schematic overlay showing internal locations of the antorbital fossa (in green; ventral extent, cross-hatching) and neurovascular tract (in blue); (3) coronal sections through maxilla as indicated in (2). alv = alveolus; aof = antorbital fossa; asr = ascending ramus of maxilla; brk = breakage; bur = buccal ridge; cem = cementum; dmt = dorsal maxillary trough; for = foramen; iaof = region of internal antorbital fenestra; lpf = lateral palatine facet and flange on maxilla; m# = maxillary tooth position (from anterior end) and replacement number; mfo# = anterior maxillary foramen (1 = dorsal branch; 2 = ventral branch); ml = medial lamina; mra = maxillary ramus; nvt = neurovascular tract; nvt? = uncertain dorsal moity of neurovascular tract; pdf = posterodorsal foramen of the maxilla; sal = supralveolar lamina; sep = septum; sgj = sutural groove for jugal; sgl = sutural groove for lacrimal; slt = slot. Scale bars: 10 mm (1, 2); 5 mm (3).

Figure 12. Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., holotypic left maxilla (NMV P229196) in dorsal view and schematic showing broken surface (dark shading) of the ascending ramus and separation of the supralveolar and medial laminae indicated by a seam of sediment infill. aof = antorbital fossa; asr = ascending ramus of maxilla; fos = fossa; ml = medial lamina of maxilla; mra = maxillary ramus; sed = host sediment infill; sal = supralveolar lamina. Scale bar = 10 mm.

Figure 13. Comparisons of Victorian ornithopod maxillae in lateral view and schematics, showing dorsalmost extent of the maxillary ramus (indicated by large arrows): (1) Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n sp., holotypic left maxilla (NMV P229196); (2) Atlascopcosaurus loadsi Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989, left maxilla (NMV P157390); (3) cast of original holotypic left maxilla of Atlascopcosaurus loadsi (NMV P166409). alv = alveolus; bur = buccal ridge; lpf = lateral palatine flange of maxilla; m#’ = maxillary tooth position (from posterior end) and replacement number; ml = medial lamina of maxilla; mra = maxillary ramus; nvt = neurovascular tract; plp = posterolateral process of maxilla; pmp = posteromedial process of maxilla; sal = supralveolar lamina of maxilla. Scale bars = 10 mm.

Figure 14. Hypsilophodon foxii Huxley, Reference Huxley1870, partial right cranium (NHMUK R2477) and schematics in oblique posterodorsal (1) and medioventral (2) views. Cross-hatching in (1) indicates missing supralveolar lamina bordering the antorbital fenestra; dashed arrow indicates entrance of the posterodorsal foramen of the neurovascular tract. aiaof = anterior (accessory) internal antorbital fenestra; aof = antorbital fossa; ap = anterior process of maxilla; asr = ascending ramus of maxilla; cem = cementum; dmt = dorsal maxillary trough; ept = ectopterygoid; iaof = internal antorbital fenestra; j = jugal; lac = lacrimal; mfos = muscular fossa of palatine; ml = medial maxillary lamina; mra = maxillary ramus; nld = nasolacrimal duct; nvf = neurovascular foramina; nvt = neurovascular tract; ped = pedestal; plr = palatine lateral ramus; pm = premaxilla; pmal = palatine medial ala; pmf = palatine maxillary flange; ppt = pterygoid process of the palatine; sal = supralveolar lamina. Scale bar = 10 mm (2; for scale in 1, refer to 2).

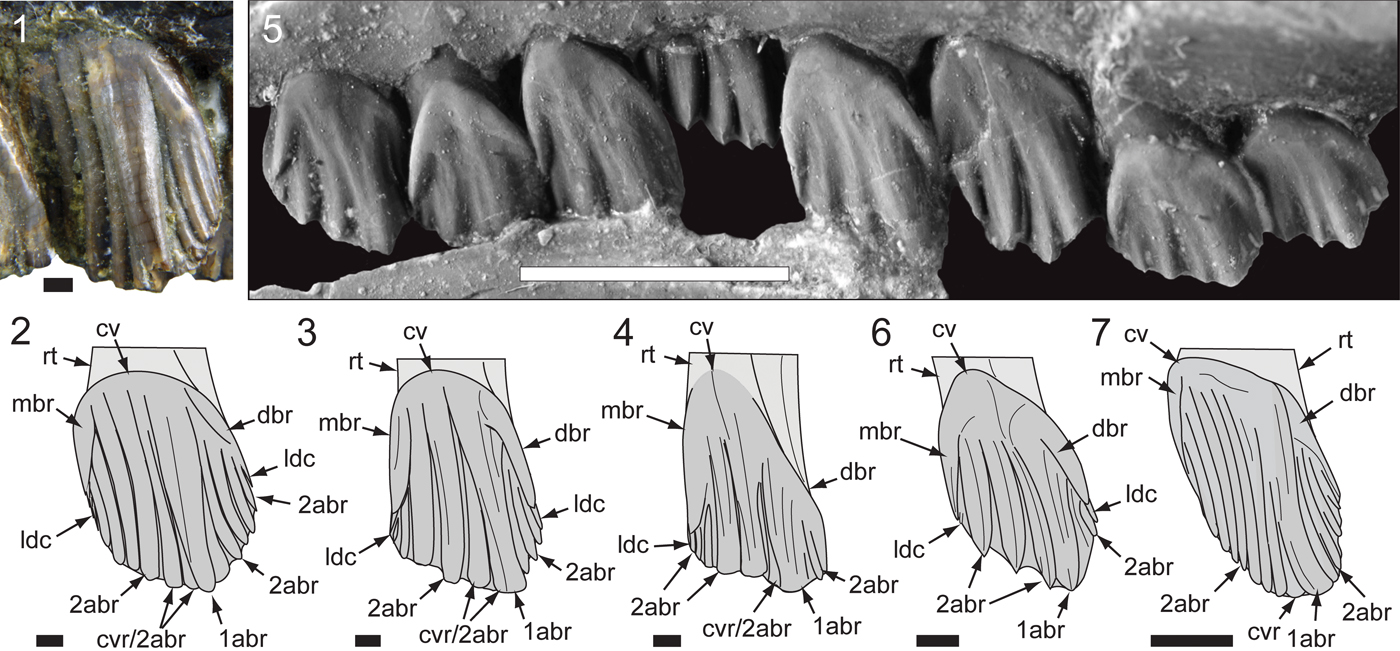

Figure 15. Maxillary dentition of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp.: (1, 2) holotypic left dentition (NMV P229196) in labial (1) and lingual (2) views; (3) enlargement of maxillary tooth (m7.2) in (2); (4) left dentition of NMV P186440 in labial view. 1abr = primary apicobasal ridge; 2abr = secondary apicobasal ridge; 3abr = tertiary apicobasal ridge; abr = apicobasal ridge (see definition, Table 1); acd = accessory denticle; cv = cingular vertex; dbr = distal bounding ridge; dpf = distal paracingular fossa; gch = growth channel/fossa; m# = maxillary tooth position (from anterior end) and replacement number; m#’ = maxillary tooth position (from posterior end) and replacement number; mbr = mesial bounding ridge; mdc = median denticle; ocf = occlusal facet. Scale bars: 5 mm (1, 2, 4); 1 mm (3).

Figure 16. Maxillary dentition of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., digital 3D model of holotypic maxillary tooth m8 (NMV P229196) derived from μCT scans in labial (1), dorsal (2), apical (3), and lingual (4) views. Larege arrow in (4) indicates sinuous bend on the lingual margin of the root. 1abr = primary apicobasal ridge; alv = alveolus; cr = crown; cv = cingular vertex; dbr = distal bounding ridge; gch = growth channel/fossa; mra = maxillary ramus; ocf = occlusal facet; rt = root. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Figure 17. Comparisons of Australian ornithopod maxillary tooth crowns in left labial view: (1, 2) Atlascopcosaurus loadsi Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989 (NMV P157390), m5’ (counted from posterior end) and schematic (2); (3) Victorian ornithopodan maxillary morphotype 4 (cf. Atlascopcosaurus loadsi; NMV P208133), schematic of right m3’ (reversed; counted from posterior end); (4) Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., schematic of holotypic (NMV P229196) m8; (5, 6) Leaellynasaura amicagraphica Rich and Rich, Reference Rich and Rich1989, holotypic (NMV P185991) m5–m12 with schematic of m9 (6); (7) Muttaburrasaurus sp. (QM F14921), schematic of left ~m4’ (counted from posterior end). 1abr = primary apicobasal ridge; 2abr = secondary apicobasal ridge; cv = cingular vertex; cvr = convergent (secondary) ridge; dbr = distal bounding ridge; ldc = lingulate denticle; mbr = mesial bounding ridge; rt = root. Scale bars: 10 mm (7); 5 mm (5); 1 mm (1–4, 6).

Holotype

NMV P229196, a complete left maxilla with partial dentition.

Table 2. Measurements (in mm) of Victorian ornithopod maxillary specimens. APL1 = anteroposterior length of maxillary ramus (without anterior process); APL2 = anteroposterior length of the dentulous maxillary portion (extent of alveoli); APL3 = anteroposterior length of anterior (premaxillary) process; DVDR = greatest dorsoventral depth of maxillary ramus; TVW1 = greatest transverse width of maxillary ramus; TVW2 = transverse width of ramus at fifth alveolus; TVW3 = narrowest transverse width of ramus; + = measurement incomplete. In incomplete specimens (NMV P166409, P157390, P208133), the alveoli are counted from the posterior end of the ramus.

Diagnosis

Small-bodied, noniguanodontian ornithopod characterized by five potential autapomorphies: (1) ascending ramus of maxilla has two slot-like foramina on the anterior margin that communicate with the neurovascular tract; (2) neurovascular tract bifurcates internally to exit at two anteroventral maxillary foramina; (3) lingual margin of maxillary tooth roots in midregion of tooth row form an S-bend at their bases; (4) posterior third of maxilla on some, but not all, specimens deflects posterolaterally at an abrupt kink; and (5) lateral end of palatine lateral ramus forms a hatchet-shaped flange.

Occurrence

Flat Rocks locality in the Inverloch region of Victoria, southeastern Australia (Fig. 1); Flat Rocks Sandstone and The Caves Sandstone, upper Barremian of the Wonthaggi Formation in the Gippsland Basin.

Description

The taxon is known from five isolated left maxillae with dentition, an isolated right maxillary tooth, the palatine, and a partial lacrimal. The most complete of the maxillae, the holotype (NMV P229196), retains four fully erupted teeth (Figs. 4, 5). Marginally larger than the holotype but incomplete, NMV P186440 (Figs. 4, 6) preserves the posterior region of the maxilla with six tooth positions (five crowns fully erupted), the complete left palatine, and a ventrolateral fragment of the lacrimal, preserved in situ. NMV P208178 is ~73% of the holotype in size and retains five erupted crowns (Fig. 4). The two smallest maxillae (NMV P209977, P212845) lack erupted dentition (Figs. 4, 7, 8). Because the complete lacrimal is presently unknown, the anteroposterior and dorsoventral extent of the antorbital fossa and external antorbital fenestra are also unknown.

Maxilla

Two maxillary forms are apparent. On NMV P229196 (the holotype), P208178, and P212845, an abrupt kink causes the posterior third of these maxillae to angle posterolaterally outward (Figs. 5, 8). This kink coincides with a bulge on the medial surface at the anterior end of the facet for the palatine, and resembles the kink on the maxilla of Camptosaurus dispar Marsh, Reference Marsh1879 (YPM VP 1886; Fig. 9). However, in the latter taxon, deflection is relatively less. On one of the smallest maxillae (NMV P209977; Fig. 7.1, 7.2), the kink is absent and could also be absent on the largest maxilla (NMV P186440; Fig. 6.1, 6.2, 6.7, 6.8), although noting that the latter specimen is incomplete anteriorly (see further comments under Variation, below). The largest complete maxillae (NMV P229196, P208178) each contain 15 alveoli, and the smallest maxillae (NMV P209977, NMV P212845) contain 13 and 14 alveoli, respectively. Viewed ventrally, the maxillary teeth are arranged en echelon, with one replacement crown present per alveolus (Figs. 5, 6). Staggered tooth replacement occurs across groups of two tooth families. The tooth row is laterally concave with the alveoli in the middle of the tooth row obliquely angled relative to the anteroposterior tooth row axis. The anterior alveoli outturn laterally relative to the lateral margin of the maxilla (Fig. 5), as in Camptosaurus dispar (YPM VP 1886; Fig. 9) and Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki Pompeckj, Reference Pompeckj1920 (Janensch, Reference Janensch1955, table 11), and similar to these taxa, no substantial diastema is developed. As a result, the anterior alveolus locates in the anteroventral process that abuts the posterolateral end of the premaxilla (Figs. 5, 7, 8). In Leaellynasaura amicagraphica, the anterior alveoli are oriented parallel to the lateral margin of the maxilla (Fig. 10.5).

The ventral region of an anteroposteriorly extensive antorbital fossa is formed by the maxilla (Figs. 5–8, 11, 12). The supralveolar lamina forms the lateral wall of the maxilla and the buccal ridge formed by this lamina is shallowly rounded dorsoventrally (Figs. 5.6, 6.11, 7, 8, 11, 12). Buccal emargination, measured midway along the tooth row in ventral view, approximately equals the labiolingual width of one crown on the holotype (Fig. 5) and two crowns on the smallest maxillae (NMV P209977, P212845; Figs. 7, 8). Buccal emargination on the maxilla of Leaellynasaura amicagraphica is shallower (approximately two-thirds of the crown width at the deepest point along the tooth row; Fig. 10.5). Similarly to L. amicagraphica, the buccal ridge is protrusive in Atlascopcosaurus loadsi, however, buccal emargination is at least as deep as in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. or possibly deeper (Fig. 10).

Viewed laterally (Figs. 4–8), the alveolar margin is shallowly concave and the anterior margin of the ascending ramus is convex. The premaxillary process is spinose and slightly inset medially from the lateral surface of the maxilla by the anteroventral process at the base of the ascending ramus (Figs. 5, 7, 8). A groove on the medial margin of the premaxillary process could have accommodated the vomer. A shallow cleft-like fossa containing neurovascular foramina is present anteriorly on the ventrolateral margin of the maxilla, dorsal to the anteroventral process (Figs. 5, 7, 8, 11), as in Changchunsaurus parvus Zan et al., Reference Zan, Chen, Jin and Li2005 (Jin et al., Reference Jin, Chen, Zan, Butler and Godefroit2010), Jeholosaurus shangyuanensis Xu, Wang, and You, Reference Xu, Wang and You2000 (Barrett and Han, Reference Barrett and Han2009), Tenontosaurus tilletti Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1970 (Thomas, Reference Thomas2015, fig. 2) and Zalmoxes robustus Nopcsa, Reference Nopcsa1900 (NHMUK R3395; unpublished data, Herne, 2009). A fossa on the anterolateral margin of the maxilla has been considered an ornithopodan synapomorphy (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Upchurch and Norman2008). Along the anterior margin of the ascending ramus, the medial lamina forms a thin, buttress-like crista with a straight anterodorsal edge connecting the dorsal edge of the premaxillary process (Figs. 5, 7). A fortuitous break through the ascending ramus on the holotype (during its preparation) indicated that the ascending ramus is formed from both the thicker supralveolar and far thinner medial laminae (Fig. 12), as in Lesothosaurus diagnosticus Galton, Reference Galton1978 (Porro et al., Reference Porro, Witmer and Barrett2015). A thin seam of sediment infill indicates that these two laminae are unfused. In places, the medial lamina is <150 µm thick and its medial surface in the region of the ascending ramus is roughened, forming a shallow fossa (Figs. 5, 12). The external antorbital fenestra is bordered anteriorly by the ascending ramus (Figs. 5, 12). Although the full form of the external antorbital fenestra cannot be assessed, because the ventral margin formed by the supralveolar lamina is degraded on all of the specimens, its ventral margin is positioned dorsally, well above the buccal ridge.

Medially (Fig. 6), the maxillary ramus is differentiated from the alveolar parapet by a medial groove, along which elongate nutrient foramina (‘special foramina’ of Edmund, Reference Edmund1957) align with the alveoli. The developing crowns and roots are encased in cementum (suggested by grayer contrast in the μCT imagery; Fig. 11). The dorsal surface of the maxillary ramus is penetrated by the alveoli (Figs. 5–8, 10, 11), as in Zalmoxes robustus, which was previously considered unique in that taxon (Weishampel et al., Reference Weishampel, Jianu, Csiki and Norman2003).

Viewed dorsoventrally, the posterior margin of the ectopterygoid flange is straight to shallowly concave and oriented orthogonally to the axis of the tooth row (Figs. 5–7). A knob- to spike-like posteromedial process projects from the posteromedial corner of the flange. The posteromedial process is separate from the maxillary ramus, which might also occur in Camptosaurus dispar (YPM VP 1886; Fig. 9). We are presently uncertain whether a separate posteromedial process is commonly developed in other taxa. The posterolateral process is weakly developed, as in Leaellynasaura amicagraphica, and contrasts with that of Atlascopcosaurus loadsi, which is more pronounced (Fig. 10). The dorsal surface of the ectopterygoid flange is striated and horizontal in posterior view (Fig. 5). Viewed medially, the dorsal surface of the maxillary ramus is convex and dorsoventrally deepest roughly midway along the ramus (Figs. 5, 7, 8). A deeply striated sutural surface for the medial flange of the palatine is developed posterior to the medial bulge that coincides with the anterior end of the medial palatine facet (Figs. 5, 7). A slotted sutural facet for the jugal and lacrimal is developed dorsally on the posterolateral edge of the maxilla (Figs. 5–8, 10, 11). Viewed laterally, the jugolacrimal margin is sinuous (Figs. 5, 6). The overall line of these margins slopes posteroventrally at ~30° relative to the alveolar margin, as in Atlascopcosaurus loadsi (Fig. 13) and L. amicagraphica (see Herne, Reference Herne2014, fig. 5.3). This margin is more steeply angled in Hypsilophodon foxii Huxley, Reference Huxley1870 (Galton, Reference Galton1974, figs. 2–3) and the anterior end of the sutural margin for the jugal on the maxilla of Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis Coria and Salgado, Reference Coria and Salgado1996 is distinctly stepped (Coria and Salgado, Reference Coria and Salgado1996, fig. 2).

The dorsal and internal structures of the maxilla are complex. Micro-CT imagery (Fig. 11) reveals regions of the antorbital fossa hidden by the matrix and the internal passage of the neurovascular system. The neurovascular tract (= neurovascular canal of Witmer, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997; maxillary canal of Thomas, Reference Thomas2015) extends the length of the maxillary ramus (Fig. 11.2) and would have conveyed the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (cn V2; see Witmer, Reference Witmer1995, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997; Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Manger and Rubidge2016; Barker et al., Reference Barker, Naish, Newham, Katsamenis and Dyke2017). Posteriorly, the neurovascular tract forms a shallow channel on the dorsal surface of the maxilla medial to the sutural groove for the jugal (Figs. 5–8, 11). The neurovascular tract enters the internal region of the maxilla at the posterodorsal foramen (Figs. 5.1, 6.7, 11.1), which is roofed dorsally by a rugose flange on the maxilla for the lateral ramus of the palatine (Figs. 5–8; 11.2, 11.3, coronal section A). A slot opening dorsally from the neurovascular tract surrounds the lateral and anterior margins of this flange (Fig. 11.1; 11.2, 11.3, coronal sections A, B).

The antorbital fossa is walled laterally and ventrally by the supralveolar lamina and medially by the medial lamina (Figs. 7, 8, 11). The posterior region of the antorbital fossa is located anterior to the flange for the lateral ramus of the palatine and lateral to the internal antorbital fenestra (Fig. 11.1, 11.2; 11.2, 11.3, coronal sections B, C). In this posterior region of the antorbital fossa, the neurovascular tract forms an internalized duct separated from the antorbital fossa by a thin septum (Fig. 11.3, coronal section C). This septum thickens in the midregion of the antorbital fossa and the neurovascular tract appears to divide into dorsal and ventral moieties (Fig. 11.3, coronal section D). In the anteriormost region of the antorbital fossa, the neurovascular tract and the antorbital fossa merge (Fig. 11.2, 11.3, coronal sections E, F). The neurovascular tract forms a dorsally opening channel on the ventral floor of the antorbital fossa. The anteriormost end of the antorbital fossa terminates at the ascending ramus (Fig. 11.1, 11.2). From this point, the neurovascular tract continues anteriorly and bifurcates to exit at two anterior maxillary foramina within a shallow anterolateral fossa, dorsal to the anteroventral process (Figs. 5, 7, 8; 11.2, 11.3, coronal sections G, H). The neurovascular tract is separated medially from the alveoli by a septum through which foramina pass (e.g., Fig. 11.3, coronal sections B, H).

Two slot-like foramina penetrate the anterolateral margin of the ascending ramus and extend posteroventrally to communicate with the merged region of the neurovascular tract and the anteriormost region of the antorbital fossa (Fig. 11.2, 11.3, between coronal sections F–H). These slot-like foramina are walled medially by the medial lamina, which in this region is exceedingly thin (<100 µm). A small foramen that exits laterally on the ascending ramus communicates with the uppermost of the two slot-like foramina (Fig. 11.2, 11.3, coronal section G). A further small foramen extends from the anterior end of the antorbital fossa dorsally to the neurovascular tract to exit laterally on the ascending ramus (Fig. 11.2, 11.3, between coronal sections F, G). Apart from the aforementioned foramina of the neurovascular tract, ~13 additional neurovascular foramina penetrate the supralveolar lamina to communicate with the neurovascular tract. The ventralmost of these foramina (Fig. 11.2, 11.3, between coronal sections B–F) pass ventrally to the antorbital fossa to communicate directly with the neurovascular tract.

The dorsal maxillary trough extends anteriorly on the dorsal surface of the maxilla, from the region of the internal antorbital fenestra and onto the dorsal surface of the premaxillary process (Figs. 5, 7, 8; 11.2, 11.3, coronal sections D–H). The antorbital fossa and dorsal maxillary trough are separated by the medial lamina. The central portion of the medial lamina extends dorsally as a thin sheet of bone (~1.2 mm thick). Sutural striae on the medial surface of the lamina suggest the region of contact with the medial lamina of the lacrimal, as in Leaellynasaura amicagraphica (see Herne, Reference Herne2014, fig. 5.8). Viewed dorsally (Fig. 5), the medial lamina on the holotype bows medially at its midpoint, partly encroaching on the dorsal maxillary trough. The degree of medial bowing is greater in the smallest maxillae (NMV P209977, P212845; Figs. 7, 8), which in this aspect, approaches the condition in Camptosaurus dispar (YPM VP 1886: Fig. 9). However, bowing of the medial lamina in the latter taxon is greater and more posteriorly positioned. A gap in the medial lamina between the anterior ascending ramus and its central region (Fig. 5) could indicate the presence of an anterior internal antorbital fenestra (‘promaxillary fenestra’ of Carpenter, Reference Carpenter, Mateer and Chen1992; Witmer, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997) as in Heterodontosaurus tucki Crompton and Charig, Reference Crompton and Charig1962 (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Crompton, Butler, Porro and Charig2011) and Hypsilophodon foxii (see Galton, Reference Galton1974), or alternatively, could have resulted from breakage.

Palatine

Viewed dorsoventrally (Fig. 6), the ala of the palatine forms a reniform, posteroventrally sloping sheet of bone that projects medially from the medial maxillary flange, which tightly adjoins the maxilla. Viewed medially, the maxillary flange has a boot-shaped profile (Fig. 6.4, 6.10). The medial ala slopes posteroventrally and fails to rise dorsally above the level of the maxillary ramus. Viewed anteriorly, the medial ala is horizontally oriented (Fig. 6.6, 6.11), as in Leaellynasaura amicagraphica (see Herne, Reference Herne2014, figs 5.6, 5.7) and differs from the angled to subvertical orientation of the alae in Muttaburrasaurus langdoni Bartholomai and Molnar, Reference Bartholomai and Molnar1981 (unpublished data, Herne, 2018), Hypsilophodon foxii (Fig. 14), styracosternans, Tenontosaurus tilletti (see Thomas, Reference Thomas2015), and Thescelosaurus neglectus Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1913 (Boyd, Reference Boyd2014). Viewed dorsally, the choanal margin is anterolaterally concave and the posterolateral margin of the flange in contact with the maxilla is laterally concave (Fig. 6.1, 6.7). The choana coincides with the internal antorbital fenestra, as in other ornithopods (Witmer, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997). A transverse ridge, posterior to the choana (‘postchoanal strut’ of Witmer, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997), crosses the dorsal surface of the palatine body (Fig. 6.1, 6.7). A deep muscular fossa is developed posterior to the strut, as in H. foxii (Fig. 14), and a shallower pneumatic fossa is developed anterior to the strut (see Witmer, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997), as in Lesothosaurus diagnosticus (see Porro et al., Reference Porro, Witmer and Barrett2015, fig. 8A, D). The pneumatic fossa is reportedly absent in Heterodontosaurus tucki (see Norman et al., Reference Norman, Crompton, Butler, Porro and Charig2011) and among ornithopods, also absent in at least H. foxii and Iguanodon bernissartensis Boulenger, Reference Boulenger1881 (Witmer, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997), Tenontosaurus tilletti (see Thomas, Reference Thomas2015, fig. 14), and the hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus regalis Lambe, Reference Lambe1917 (Heaton, Reference Heaton1972, figs. 2, 5). A strap-like lateral ramus extends over the convex dorsal surface of the maxilla and a hatchet-shaped, dorsoventrally compressed flange is developed at the end of the lateral ramus. This flange is accommodated in the sutural flange on the maxilla (Figs. 5–8, 11.1; 11.3, coronal section A), coinciding with the medial face of the lacrimal (see below), and most likely the anteriormost end of the jugal.

Lacrimal

A small, plate-like fragment of bone adjoining the maxilla in NMV P186440 (Fig. 6) is interpreted as the posteroventral portion of the left lacrimal. The irregular ventral edge of the fragment locates in the sutural slot on the maxilla anterior to the margin for the jugal. The lacrimal slightly overlaps the sutural edge laterally on the maxilla. The anterolateral surface of the lacrimal is slightly scalloped.

Maxillary dentition

The crowns and roots have en echelon emplacement relative to the long axis of the tooth row and the erupted crowns are imbricated (Figs. 5, 6, 15), as in all ornithischians (e.g., Porro et al., Reference Porro, Butler, Barrett, Moore-Fay and Abel2011, Reference Porro, Witmer and Barrett2015). Viewed labially, the distal margins of the crowns mostly overlap the mesial margins of the adjacent crowns. This pattern of overlap is reversed on some crowns (Fig. 15). The roots taper toward their distal ends and are roughly ovoid in section (Fig. 16). The axis of the root is straight. However, the lingual margin of the root on the teeth in the middle of the tooth row forms a marked S-shaped bend extending dorsally from its base at the cingulum (Fig. 16.4). As a result, mesiolingual and distolingual fossae are formed that accommodate developing crowns of the abutting tooth families. Twisting of the root shaft also aligns the broad mesial and distal surfaces of the roots with the oblong, obliquely angled alveoli (Fig. 5.4). The resorption facets on the roots follow the profile of the apical margins of the successively developing crowns (Fig. 15). At full-length, the roots reach the dorsal surface of the maxillary ramus (Fig. 16). Tooth replacement is posterior to anterior with a Zahnreihe spacing (‘Z-spacing,’ sensu Edmund, Reference Edmund1960) of 1.65 suggested (calculated at M7–M8 on the holotype; based on methods of Osborn, Reference Osborn1975, fig. 1).

The largest maxillary crowns are in the posterior region of the tooth row. However, the two posteriormost teeth are reduced (Fig. 17), as in most ornithopods. At M8 on the holotype, the ratio of apicobasal depth/mesiodistal width is 1.8 (Fig. 17.4), noting that that the unworn depth of the crown would have been greater. The unworn crowns are spatulate and asymmetrical in labiolingual profile. Wear facets on the worn (working) crowns form a continuous occlusal surface, which slopes at ~ 45° to the root axis, in mesiodistal view (Figs. 5; 11.3, coronal section D; 15). Labially and lingually, the basal region forms a deep V-shaped cingular vertex, offset mesially relative to the central axis of the root (Figs. 15–17). Lingually, the cingulum forms a smooth base lacking bounding ridges. Labially, the cingulum forms the mesial and distal bounding ridges (Figs. 15–17). The mesial bounding ridge is straight and vertically oriented. The distal bounding ridge is longer than the mesial, obliquely sloping from the vertex and arcuate toward its apical end. The primary ridge, developed labially, is arcuate (mesially concave/distally convex), strongly offset to the distal third of crown surface, and merges with the distal bounding ridge, distal to the cingular vertex (Figs. 15–17). On many of the crowns, a shallow labial furrow is formed at the point of confluence with the primary ridge, as in Leaellynasaura amicagraphica (Fig. 17). On some crowns, the primary ridge is slightly undercut by the narrow distal paracingular fossa, as in Atlascopcosaurus loadsi and Muttaburrasaurus sp. (QM F14921). Labially, the secondary apicobasal ridges are closely abutting. Four stronger ridges are developed mesial to the primary ridge (Figs. 15–17). The ridge closest to the primary ridge is convergent with the latter. Two finer secondary ridges are developed in the paracingular fossa distal to the primary ridge (Figs. 15–17). These distal ridges merge with the inside margin of the mesial bounding ridge. Tertiary ridges are additionally developed on the surface of the primary and secondary ridges (Fig. 15.1), as in Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis (Hooley, Reference Hooley1925) (Norman, Reference Norman1986). Narrow apicobasal ridges, separated by channels, are developed on the lingual crown surfaces (Fig. 15). These ridges merge with the smooth crown base. The distal ends of all secondary ridges terminate apically in a transversely oriented, blade-like denticle. The stronger, mesial secondary ridges additionally form tridenticulate mamillated cusps (Fig. 15.3), as in Nanosaurus agilis Marsh, Reference Marsh1877 (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Galton, Siegwarth and Filla1990; Carpenter and Galton, Reference Carpenter and Galton2018).

Variation

Among the four maxillae with complete alveoli, the number of alveoli varies (Figs. 4, 5, 7, 8). The holotype (NMV P229196) and midsized maxilla (NMV P208178) each have 15 alveoli, and the smaller maxillae (NMV P209977, P212845) each have 13 and 14? (15?) alveoli, respectively. In NMV P209977, a protuberance at the anterior end of the alveolar margin, within the anteroventral process, is interpreted as a blind, developing alveolus (Fig. 7). In NMV P212845 (with 14 or 15 alveoli), the anteriormost alveolus is small and contains a germ tooth. This developing tooth is in the same position as the protuberance on NMV P209977 (Fig. 8). As a result of the abrupt kink on the maxillae of the holotype (NMV P229196), NMV P212845, and possibly in P208178, the posterior portion of the ramus is posterolaterally deflected (Figs. 5, 8). The kink, however, is lacking on NMV P209977 and P186440 (Figs. 6, 7). Therefore, although noting limitations in sample size, the kink is both present and absent on maxillae of larger and smaller sizes. We postulate that the presence and absence of the kink is due to dimorphic rather than ontogenic variation. The dorsal surface of the maxillary ramus on the small maxilla NMV P209977 differs from the other maxillae by forming a pyramid-shaped peak (compare Figs. 5–8). On the other maxillae, including the similarly sized NMV P212845, the surface is smoothly convex. This variation is also incongruent to maxillary size and could be dimorphic. The reasons for dimorphism are unknown. Subspecies variation seems possible, particularly given that the fossil assemblage of the Flat Rocks Sandstone is time-averaged. Sexual dimorphism is also possible, although extremely difficult to assess (see Mallon, Reference Mallon2017). Minor variation is apparent among the observable tooth crowns, although secondary ridge numbers appear uniform. The distal paracingular fossa excavates the distal bounding ridge on the crowns of NMV P186440 to a greater degree than on the holotype (Fig. 15).

Etymology

dorisae, in recognition of Doris Seegets-Villiers for her geological, palynological, and taphonomic work on the Flat Rocks fossil vertebrate locality.

Materials

Flat Rocks Sandstone: NMV P212845, partial left maxilla lacking erupted dentition; NMV P208178, partial left maxilla with erupted dentition; NMV P208113, worn right maxillary tooth; NMV P208523, worn left maxillary tooth; and NMV P209977, partial left maxilla, lacking erupted dentition. The Caves: NMV P186440, posterior portion of left maxilla, left palatine, and fragment of left lacrimal.

Remarks

The maxilla of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. possesses several traits typically shared with noniguanodontian neornithischians, including: (1) extensive excavation of the maxilla by the antorbital fossa; (2) articulation of the ectopterygoid restricted to the posterior margin of the maxilla; (3) a single replacement cheek tooth per tooth family; (4) shallow medial inset of the premaxillary process on the maxilla; (5) absence of channel on the anterior ascending ramus of the maxilla for the premaxilla; (6) an obtuse anterior margin on the maxilla; and (7) the lack of contact between the jugal and the external antorbital fenestra by insertion of the lacrimal (as indicated on NMV P186440; Fig. 6). These traits are apparent in neornithischians such as Heterodontosaurus tucki (see Norman et al., Reference Norman, Crompton, Butler, Porro and Charig2011), Hypsilophodon foxii (see Galton, Reference Galton1974), Lesothosaurus diagnosticus (see Porro et al., Reference Porro, Witmer and Barrett2015), and Changchunsaurus parvus (see Jin et al., Reference Jin, Chen, Zan, Butler and Godefroit2010). However, an extensive antorbital fossa is also present in the rhabdodontids (e.g., Zalmoxes robustus [NHMUK R3395; unpublished data, Herne, 2009; see also Nopcsa, Reference Nopcsa1904, table 2; Weishampel et al., Reference Weishampel, Jianu, Csiki and Norman2003]) and basal dryomorphans (e.g., Camptosaurus dispar [YPM VP 1886, Fig. 9] and Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki [see Janensch, Reference Janensch1955; Galton, Reference Galton1983; Hübner and Rauhut, Reference Hübner and Rauhut2010]). Like Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., the premaxillary process on the maxilla of Muttaburrasaurus langdoni lacks strong medial inset (unpublished data, Herne and Nair, 2018). However, as in styracosternans, the premaxillary process in M. langdoni is dorsally elevated and a deep channel for the premaxilla is developed on the posterodorsally sloping anterior margin of the anterior ascending ramus (e.g., Norman Reference Norman, Weishampel, Dodson and Osmólksa2004; Gasulla et al., Reference Gasulla, Escaso, Ortega and Sanz2014).

The maxilla of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. differs from that of Atlascopcosaurus loadsi by having a less protrusive posterolateral process and a shallower posterior slope on the dorsal surface of the maxillary ramus leading from the dorsal summit of the maxillary ramus to the ectopterygoid shelf. The maxilla of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. differs from that of Leaellynasaura amicagraphica by having greater lateral concavity of the maxillary alveolar axis and deeper buccal emargination. The number of alveoli in the largest complete maxillae of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (up to 15) is greater than that currently known in L. amicagraphica (12 in the holotype, NMV P185991). However differing numbers of alveoli between these two taxa could be due to differing stages of ontogeny. On three of the five maxillary specimens currently assigned to Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., the posterior third of the maxilla deflects posterolaterally outward at an abrupt kink (see Variation, above). The kinked form is regarded herein as a potential autapomorphy, with its absence on some maxillae interpreted as dimorphic variation.

The neurovascular tract in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. is separated from the posterior region of the antorbital fossa by a septum (see coronal section F in Fig. 11.3), which is potentially autapomorphic; however, this region has not been described in adequate detail in most ornithischians to fully confirm its uniqueness. In contrast to Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., the neurovascular tract of Hypsilophodon foxii merges with the antorbital fossa. In Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., the ventrolateral neurovascular foramina bypass the antorbital fossa to directly connect the neurovascular tract (Fig. 11.3, coronal sections B–F). These foramina in H. foxii (NHMUK R1477; Fig. 14), and most likely Zalmoxes robustus (NHMUK R3395; unpublished data, Herne, 2009), penetrate the supralveolar wall to directly enter the antorbital fossa. A similar condition is described in Changchunsaurus parvus and Jeholosaurus shangyuanensis (see Barrett and Han, Reference Barrett and Han2009; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Chen, Zan, Butler and Godefroit2010). In Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis, the neurovascular tract is separated from its reduced antorbital fossa and restricted to the region between the internal and external antorbital fenestra (see Witmer, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997, fig. 11B). Similar morphology is likely in Tenontosaurus tilletti (see Thomas, Reference Thomas2015). In this aspect, separation of the neurovascular tract and posterior region of the antorbital fossa in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. appears closer to that of the nonrhabdodontid iguanodontians than to the condition in H. foxii and basal neornithischians. Future investigation of this region in other ornithischians could prove phylogenetically informative.

In Hypsilophodon foxii (NHMUK R1477; Fig. 14) and Tenontosaurus tilletti (see Thomas, Reference Thomas2015), the size of the posterodorsal neurovascular foramen relative to the dorsal surface of the maxilla is substantially larger than in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (Figs. 6–8, 10, 11). The relatively small foramen in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. more closely resembles the condition in Camptosaurus dispar (YPM VP 1886; Fig. 9) and Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis (see Witmer, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997, fig. 11B). The two slot-like foramina on the anterolateral margin of the anterior ascending ramus in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (Fig. 5) that communicate with the neurovascular tract have not been previously described in any other ornithischian. Bifurcation of the neurovascular tract in the maxilla forming two anterior exits is also unique. For example, in Tenontosaurus tilletti (see Thomas, Reference Thomas2015) and Zephyrosaurus schaffi Sues, Reference Sues1980 (Sues, Reference Sues1980), a single maxillary foramen is reported within the anteroventral fossa. However, there is the possibility that dual foramina in other ornithischians have been previously overlooked.

In Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., the anterior region of the antorbital fossa is partitioned from the internal nasal cavity by the medial lamina of the maxilla (Figs. 8, 11, 12) as in basal neornithischians (e.g., Jeholosaurus shangyuanensis [see Barrett and Han, Reference Barrett and Han2009]), basal dryomorphans (e.g., Dryosaurus elderae Carpenter and Galton, Reference Carpenter and Galton2018 [see Galton, Reference Galton1983], Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki [see Janensch, Reference Janensch1955; Hübner and Rauhut, Reference Hübner and Rauhut2010, p. 4], and Camptosaurus dispar [YPM VP 1886]), and possibly the rhabdodontid Zalmoxes robustus (suggested on the incomplete left maxilla, NHMUK R3395). However, in Tenontosaurus tilletti (see Thomas, Reference Thomas2015, figs. 10, 19) and styracosternans (e.g., Iguanodon bernissartensis [see Witmer, Reference Witmer, Currie and Padian1997, fig. 11B]), the medial lamina fails to partition the antorbital fossa. Similarly, in Hypsilophodon foxii (NHMUK R2477), the medial lamina of the maxilla is absent along the posterior margin of the ascending ramus and as a result, the anterior region of the antorbital fossa opens into the nasal cavity through the anterior (accessory) internal antorbital fenestra (Fig. 14.2). Therefore, among ornithopods, the form of the medial lamina in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. appears closer to basal dryomorphans than to H. foxii and Tenontosaurus tilletti.

The presence of a well-developed dorsal maxillary trough, as in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., is uncertain in Atlascopcosaurus loadsi and Leaellynasaura amicagraphica. A dorsal maxillary trough has been reported in Zalmoxes robustus (NHMUK R4901; Weishampel et al., Reference Weishampel, Jianu, Csiki and Norman2003), although this region in NHMUK R4901 is obscured by matrix. However, on another maxilla of Z. robustus (NHMUK R3395; unpublished data, Herne, 2009), the dorsal maxillary trough is absent because the maxilla is strongly excavated by the antorbital fossa (see also Nopcsa, Reference Nopcsa1904, table 2.3). In comparison to Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., the dorsal maxillary trough is shallow in Tenontosaurus tilletti (see Thomas, Reference Thomas2015, figs. 14, 17) and Hypsilophodon foxii (NHMUK R2477; Fig. 14) and absent in Camptosaurus dispar. In the last taxon, the medial lamina of the maxilla markedly bulges medially to accommodate a transversely broad antorbital fossa (Fig. 9). Bulging of the medial lamina is also developed on the maxillae of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., in particular, in the smaller maxillae (NMV P209977, P212845; Figs. 7.2, 8.2, 8.3), but not to the extent observed in Camptosaurus dispar.

The lateral ramus of the palatine in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. is horizontally oriented and strap-like and expands laterally to form a flange (Figs. 6, 10). The hatchet-shaped form of the lateral palatine flange is a potential autapomorphy of the taxon. The lateral flange on the palatine is received in an anteroposteriorly oriented sutural facet on the dorsal surface of the maxilla posterior to the antorbital fossa (Figs. 5–8, 11). This facet on the maxilla for the palatine forms the dorsal surface of the flange that overlies the neurovascular tract (Figs. 5, 7, 8, 11.1; 11.2, 11.3, coronal section A)—morphology shared with Atlascopcosaurus loadsi (Fig. 10.6, 10.7) and possibly Leaellynasaura amicagraphica—and might be unique to these taxa. A lateral palatine flange is also postulated for Atlascopcosaurus loadsi (Fig. 10), as indicated by the facet on the dorsal surface of the maxilla as mentioned. However, in contrast to the hatchet-shaped flange on the lateral ramus of the palatine in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., that of Atlascopcosaurus loadsi was likely to have been asymmetrically expanded in the posterior direction (Fig. 10). As in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., the lateral palatine ramus in Camptosaurus dispar (YPM VP 1886) would have been horizontally oriented, as suggested by a rugose facet on the dorsal surface of its maxilla (Fig. 9). However, unlike in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., a facet on the maxilla for a lateral flange of the palatine is not apparent. The lateral ramus of the palatine in Jeholosaurus shangyuanensis is reportedly horizontally oriented (Barrett and Han, Reference Barrett and Han2009), as in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., but differs in being hook-like. Unlike in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., the lateral rami on the palatines of Hypsilophodon foxii (NHMUK R2477; Fig. 14) and Tenontosaurus tilletti (see Thomas, Reference Thomas2015) form thickened, dorsolaterally directed struts, which adjoin dorsally raised pedestals on their maxillary rami. The distal ends of these rami lack an expanded flange. A lateral ramus on the palatine is absent in Thescelosaurus neglectus (see Brown et al., Reference Brown, Boyd and Russell2011; Boyd, Reference Boyd2014) and styracosternans (e.g., Horner, Reference Horner1992). This region currently lacks detailed description in dryosaurids and ornithischians in general, thus inhibiting more extensive comparisons.

The maxillae of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. suggest that new alveoli developed at the anterior end of the tooth row during ontogeny, which is consistent with the pattern of development interpreted in Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki (see Hübner and Rauhut, Reference Hübner and Rauhut2010), Jeholosaurus shangyuanensis (see Barrett and Han, Reference Barrett and Han2009), and Heterodontosaurus tucki (see Norman et al., Reference Norman, Crompton, Butler, Porro and Charig2011). The sinuous lingual margin on the maxillary tooth roots in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. is not presently reported in any other ornithischian (Fig. 16).

Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. possesses a combination of seven maxillary crown features, which include: (G1) spatulate, asymmetrical crowns, resulting from having markedly V-shaped labial and lingual cingular vertices offset mesially relative to the central root axis and the primary ridge (developed labially) offset to distal third of the crown surface; (G2) the primary ridge on some crowns slightly undercut by the distal paracingular fossa; (G3) the distal bounding ridge developed labially being longer and more sloping than the mesial bounding ridge, which is relatively straight and vertical; (G4) secondary ridges, developed labially, closely abutting the ridges distal to the primary ridge more finely developed than those mesially; (G5) secondary ridges developed lingually, with mesiodistally narrow crests; (G6) the primary ridge and secondary ridges mesial to the primary ridge, terminating apically in mamillated, tridenticulate cusps; and (G7) apical crown margins lacking the development of multiple unsupported lingulate denticles.

Nearly all of the aforementioned maxillary crown features (G1–7) in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. are shared with Atlascopcosaurus loadsi, Leaellynasaura amicagraphica, and Muttaburrasaurus spp. (see comparisons, Fig. 17). However, specific differences are apparent among these taxa. Whereas the cingular vertex on the labial crown surfaces of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., L. amicagraphica, and Muttaburrasaurus spp. are V-shaped and mesially offset (in part, crown feature G1), the labial cingular vertex on the Atlascopcosaurus loadsi crowns is U-shaped and more centrally positioned. However, the lingual vertex on the Atlascopcosaurus loadsi crowns is V-shaped and mesially offset, as in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. The base of the primary ridge on the crowns of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp., Atlascopcosaurus loadsi, and Muttaburrasaurus spp. merges more distally with the distal bounding ridge than on the crowns of L. amicagraphica (Fig. 17). On crowns of similar size, those of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. differ from those of Atlascopcosaurus loadsi by having fewer secondary ridges mesial to primary ridge (four ridges compared with six) and fewer, more finely developed, secondary ridges distal to primary ridge (two ridges compared with four). In secondary ridge number and development, the crowns of L. amicagraphica are closer to those of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. than to those of Atlascopcosaurus loadsi. The number of secondary ridges on the maxillary crowns of Muttaburrasaurus spp., mesial to the primary ridge, is substantially greater (~11 ridges) than on the crowns of the Victorian taxa. However, the number of secondary ridges in the distal paracingular fossa on the crowns of Muttaburrasaurus sp. (QM F14921; four ridges) is comparable to that in Atlascopcosaurus loadsi. Tridenticulate mamillated cusps on the crowns of Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. (crown feature G6; Fig. 15) are shared with the holotype of Atlascopcosaurus loadsi (NMV P166409), and are unknown on the crowns of L. amicagraphica and Muttaburrasaurus spp. Tridenticulate marginal cusps have previously been reported only in the Late Jurassic Laurentian neornithischian Nanosaurus agilis (‘multi-cuspid cusps’ of Carpenter and Galton, Reference Carpenter and Galton2018).

Most of the maxillary crown features in Galleonosaurus dorisae n. gen. n. sp. are also shared with the Argentinian ornithopods Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis (MUCPv 208; unpublished data, Herne, 2008) and Talenkauen santacrucensis Novas, Cambiaso, and Ambrosio, Reference Novas, Cambiaso and Ambrosio2004 (based on Cambiaso, Reference Cambiaso2007, fig. 17). These include having: (1) spatulate crowns (Fig. 3.3c) with V-shaped cingular vertices and asymmetrical form, resulting from distal offset of the primary ridge (crown feature G1; noting that mesial offset of the cingular vertices is uncertain); (2) closely abutting secondary ridges developed labially, eliminating space for ridge-free paracingular fossae with finer secondary ridges developed distal to the primary ridge (crown feature G4); (3) the primary ridge slightly undercut by the distal paracingular fossa (crown feature G2); and (4) the absence of multiple unsupported lingulate denticles along the apical margins of the crowns (crown feature G7). Apicobasal ridges are also developed on the lingual crowns of Talenkauen santacrucensis (crown feature G5), but these are presently unknown in Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis.