Introduction

The ceaseless search by African Americans for legal equality, equal opportunity, the ability to earn a livable wage and to support their families, and protection from racial violence emerged as defining features of U.S. race relations during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Until recently, historians have referred to this period as the “nadir” or as the “triumph of white supremacy,” a time when African Americans across the nation, but especially in Southern states, lost many of the legal rights and privileges that they had attained during the era of Reconstruction. Although historians acknowledged the growth and flowering of predominantly Black institutions, such as schools, churches, women’s clubs, and fraternal societies, and the emergence of capable Black leaders on the state and national level, historians continue to portray this era as one in which African Americans moved backward rather than forward. As the scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in his seminal work, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880 (1935), “The attempt to make black men American citizens was in a certain sense all a failure, but a splendid failure.”Footnote 1

Although these interpretations are not inaccurate, they are incomplete, for they fail to incorporate the views of Black leaders and their families, who utilized numerous strategies to improve their lives and to find their place in American society. Not all African Americans, to be sure, possessed either the education or the resources to utilize the many options that were available to carve out successful lives and careers during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, considering the persistence of Jim Crow laws, racial violence, and a widespread belief that Blacks constituted an inferior racial caste. Yet some Black families bucked the odds and succeeded despite these obstacles, and their example helps us to understand how Black families across time and space rejected their characterization as helpless victims and forged meaningful lives.Footnote 2 The Stewart family is one example of a Black middle-class family that navigated the difficult and fraught terrain of race relations in the late nineteenth and early twenties centuries.

The Stewarts were a remarkable African American family, but they would have been regarded as a remarkable family irrespective of their race or nationality. Defying the odds, they succeeded in obtaining an education in an era when it was difficult, if not rare, for most African Americans to gain even the rudiments of reading and writing in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They also established careers and worked a variety of professional jobs in cities, territories, and countries that spanned the globe, including Charleston, South Carolina; New York, New York; Portland, Oregon; San Francisco, California; the U.S. territory of Hawaii; London, England; the U.S. Virgin Islands; and Liberia, Africa.

The Stewart family helps inform Gilded Age and Progressive Era historians because their collective family histories document their lives and struggles across three generations.Footnote 3 Some family members broke under the strain of unreasonable expectations by a demanding patriarch and unrelenting racism. But the majority, both men and women, persevered and navigated difficult and often insurmountable obstacles that were repeatedly placed in the path of African Americans of all classes over the past two centuries, obstacles that were designed to strip African Americans of their dignity, maintain white supremacy, and enforce second-class citizenship. The Stewarts, however, rejected these pejorative and racist images of themselves and other African Americans as unambitious, shiftless, and racially inferior. They argued that American society, not African Americans, was sick and in need of healing and repair. The Stewarts believed, too, that as a family they had been blessed, that they were gifted, that their mission in life was to improve the condition of African Americans less fortunate than themselves, to serve as role models, and to provide leadership to their communities. They felt that it was just as important to transmit these values of service and sacrifice and uplift from one generation to the next, so that future generations would continue to serve the race and the nation in some capacity.

The Stewart family

T. McCants Stewart was the most pivotal figure in the Stewart family. The elder Stewart was a feared and respected patriarch, a domineering father, and a Black leader of national stature. Born a free man in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1853, Thomas McCants Stewart came to maturity during the tumultuous decades of the 1850s and 1860s. Like most free Blacks in the United States, little is known about his early years. It is not known, for example, who provided Stewart’s formative education or instilled in him the desire to excel, for antebellum Charleston, like most Southern cities, had no public schools for free Blacks and none, of course, for enslaved people. Yet Stewart had demonstrated sufficient academic promise by the age of twelve as to attend the Avery Normal Institute, an elite preparatory training school for Black Charlestonians.Footnote 4 [Figure 1]

Fig. 1. T. McCants Stewart, photographer and date unknown, Stewart-Flippin Family Papers, Box 97-31, Folder 568, image ID 097-S-031-568_284, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

Stewart left Avery in 1869 to attend Howard University. Apparently, dissatisfied with the level and quality of academic work at Howard during its formative years, he enrolled at the University of South Carolina at Columbia, where he earned a degree in mathematics and law during the era of Reconstruction. From there, Stewart attended the Princeton Theological Seminary, where he spent three years, a stellar accomplishment for a Black student, although he did not graduate from the prestigious seminary. His years at Princeton represented his first formal religious training and the first occasion when he lived in a Northern state. Nevertheless, with a college diploma in hand from the University of South Carolina and three years of seminary training behind him, Stewart joined an expanding circle of African Americans, predominantly men, who had earned college degrees and attended professional schools during the post-Civil War era. W.E.B. Du Bois would later refer to these individuals as the “talented tenth.”Footnote 5

After practicing law in South Carolina and becoming an ordained minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, in 1880, Stewart decided to spread his wings and move to New York. There, he worked as a journalist, writer, politician, minister, civil rights activist, and Black nationalist. Upon arriving in New York, Stewart served as pastor of the Bethel AME Church, an interracial church with approximately one thousand members. The Black Church in New York and throughout the nation, irrespective of region or the size of the Black community, had a long history as an agency of racial uplift, and Stewart attempted to place his ministry within this tradition.Footnote 6

In the two decades that he resided in New York between 1880 and 1898, Stewart was transformed into a national leader. These were among the most productive years of Stewart’s career. Like many Black leaders of national stature at the time, Stewart advocated self-help, moral reform, industrial education, and racial pride, clearly putting him in the camp of Booker T. Washington and his followers. An active supporter of Washington’s leadership, Stewart delivered the prestigious commencement address at Tuskegee Institute in 1893, succeeding Frederick Douglass, widely regarded as the leading Black spokesperson for African Americans in the nineteenth century. Stewart two sons, McCants and Gilchrist, both attended and graduated from Tuskegee.Footnote 7

Stewart, however, was too complicated to be placed in merely one box or racial category, and like many Black and white leaders of his era, his racial ideology shifted over time. In addition to embracing Washington’s philosophy of racial accommodation, which hit its high-water mark following Washington’s famous speech in September 1895 at the Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition, Stewart was also a Black nationalist and emigrationist, who had immigrated to Liberia, Africa, in 1883, under the auspices of the American Colonization Society, where he accepted a professorship at Liberia College. Moreover, unlike Booker T. Washington, Stewart was a vigorous advocate of civil rights, and an uncompromising champion of racial equality. He used the pages of the New York Age, one of the leading Black newspapers of the era, to press for full equality for African Americans.Footnote 8

Hawaii

In 1898, Stewart abruptly left New York and migrated to Hawaii, where he would spend the next seven years working as an attorney, an activist, and an advocate of civil rights for the Hawaiian people. Stewart had also hoped to make his fortune in Hawaii by investing in local industries such as sugar and pineapples, as well as to organize the Republican party on the island. He expected, too, like many Black leaders of his era, to gain a major political appointment because of his long years of service to the Republican party.Footnote 9

Despite the territory’s minute Black population in 1900 (only 233 African Americans lived in Hawaii in 1900, two years after Stewart first arrived), Stewart believed that Hawaii offered an ambitious man like himself the opportunity to prosper. The Honolulu Advertiser noted that Stewart came to Hawaii “highly commended,” with letters of commendation from former president Grover Cleveland, the U.S. minister to Spain, and C.P. Huntington, the noted financier and industrialist. The relocation to Hawaii in 1898 was remarkably consistent with the pattern that Stewart had established early in his career. He had shown a pioneering determination to improve his condition when he moved from South Carolina to New Jersey, then to New York, then to Liberia, and now to Hawaii.Footnote 10

Stewart perceived Hawaii in the early 1900s as a frontier community, and he wanted to take ample advantage of the economic and political opportunities on the islands during the early stages of American settlement. Yet Stewart, a realist, was also attempting to escape racial discrimination in the United States, which had grown more intense as the century drew to a close.Footnote 11 In a candid letter to his eldest son, McCants, he wrote: “I am a victim of the white man’s unholy color line. In 1878 I left South Carolina to escape it [prejudice]. In 1883 I left New York to escape it [prejudice]. And now, ah, whither shall I flee?”Footnote 12

T. McCants Stewart wasted no time in making his presence felt in Hawaii. He established a law practice in Honolulu and is generally regarded as the first Black lawyer in Hawaii. Stewart also enrolled his young daughter Carlotta in Oahu College (the Punahou School) and then, to no one’s surprise, he became active in Republican party politics. Stewart became the most prominent Black leader in Hawaii prior to the emergence of other distinguished African Americans, such as William F. Crockett, who later served in the Territorial House of Representatives, as a district magistrate of Wailuku, Hawaii, and deputy county attorney for Maui. Stewart received glowing reports regarding his political activities in the Honolulu Advertiser, no easy task for an African American in those days. And he received an occasional distinguished visitor from the mainland, including his close friend T. Thomas Fortune, the militant editor of the New York Age, who stopped off in Hawaii to visit Stewart en route to the Philippines.Footnote 13

T. McCants Stewart made neither a fortune, as he had hoped, nor obtained a political appointment of any magnitude. Yet Stewart emerged as an important figure in Hawaiian history. Stewart immediately distinguished himself as an attorney in Hawaii, at least among his colleagues and fellow jurists. He was admitted to the Hawaiian bar in 1898, and during his seven years on the island, Stewart made sixteen appearances before the Hawaii Supreme Court and argued five cases before the U.S. district court of Hawaii. Similarly, Stewart “became the first lawyer in Hawaii [of any race] to litigate a case in the newly established federal court.”Footnote 14

Stewart also played a prominent role in Republican party politics in Oahu, attempting to secure a larger role and a more significant voice for the Hawaiian people in local government and identifying with the labor struggles of Hawaiian and Chinese workers in the islands. Notably, Stewart opposed the Chinese Exclusion Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 1882 and a similar act passed by the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1886. Stewart, a stalwart and committed racial activist on the U.S. mainland, detested the 1882 act because it promoted exclusion based on race. Indeed, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act represented the first immigration act ever passed by Congress to exclude a person based upon their race and class.Footnote 15 It is also reasonable to assume that Stewart, give his own working-class background, equated the plight of Chinese laborers with the struggle of black southerners to advance economically during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Stewart had a long history of supporting the less fortunate in areas of civil rights and social justice.Footnote 16 He would, no doubt, have agreed with the view of Albert Francis Judd, chief Justice of the Hawaii Supreme Court, who had also served as a mentor to Stewart, that to exclude the Chinese laborer would constitute “rank tyranny.” True, Stewart identified with and supported the Hawaiian people in their quest for greater autonomy, but this was also consistent with his own political ambition, which rested on cracking the island’s centralized government. These two motivations were never far apart.

By the spring of 1900, the Honolulu Advertiser reported that Stewart had managed a Republican party meeting in Honolulu, and that he and a group of local political leaders were attempting to organize the GOP on the island of Oahu. That same year, Stewart was appointed by the Republican party territorial central committee to draft an act granting the Hawaiian people local government. Stewart collaborated with a group of local leaders to write the organic act, and the conservative Honolulu Advertiser reported that Stewart favored including a broader sector of the Hawaiian electorate in the Republican party, such as the Portuguese, than the party bosses did.Footnote 17

Stewart’s rapid rise within Republican party circles was remarkable given his lack of familiarity with Hawaii’s history, culture, and language, as well as the nuances of Hawaiian politics, and both subtle and overt racism within the Republican party. Yet racism, even three thousand miles from the American mainland, reared its ugly head, and Stewart, despite his accomplishments, often felt its sting. The local press occasionally mocked him and referred to him as “the African,” and in a related instance, Stewart accused a fellow lawyer, of calling him a racial slur, a common occurrence in many southern courtrooms, but perhaps a bit surprising in early twentieth century Hawaii.Footnote 18

Stewart’s political fortunes, however, never measured up to his expectations. He received a minor political appointment from Sanford B. Dole, the governor of Hawaii, and Stewart boasted to his eldest son McCants that “I am a boss here as compared to New York.” Similarly, Stewart’s investment in Hawaiian sugar did not produce the returns that he anticipated, for these industries were dominated by American industrialists before his arrival. Although he praised the political progress that had taken place on the islands, Stewart was clearly dissatisfied with his own status and perhaps a bit troubled by intermittent racism directed at him personally. “I must confess that I am not happy, and I have been for the past two or three years under a cloud of race prejudice,” he lamented. Discouraged, Stewart left Hawaii in 1905 and migrated to London, England, where he resided for several years and used as a base to conduct business with Liberia, a nation that he had renounced after his departure in 1885.Footnote 19

T. McCants Stewart also expressed contempt at the thought of ever residing permanently in the United States. He felt that London was a more accepting and egalitarian society racially than the United States, and he was also reluctant, he admitted, to surrender the social status and acclaim that he enjoyed in London, and the freedom from overt discrimination. In perhaps the strongest language that Stewart ever expressed privately, he informed his son McCants that “I could not live in America for a gold mine, if the conditions was [sic] that I must reside there.” He expressed grave doubts, too, about the United States’ ability to improve the racial situation sufficiently for Blacks to ever achieve full equality. This pessimistic comment was in stark contrast to the optimism that Stewart had expressed throughout his life as he searched for new opportunities and challenges.Footnote 20

Stewart’s favorable treatment in London, like his situation in Hawaii, was due in large measure to his class standing and his association with influential white Englishmen. Most Black Britons struggled economically and socially during the early decades of the twentieth century and lived on the margins of English society. White Englishmen discriminated against people of African descent, including those from the former English colonies, based on class as well as color. Black Britons also faced intermittent racial violence and race riots, like their counterparts in the United States, and were treated as an inferior racial caste. Stewart, therefore, misread perhaps consciously, because he was a keen observer of race, his own acceptance in London society as a sign that conditions for all Blacks had progressed. He was mistaken.Footnote 21

Liberia, Africa

Almost as abruptly as he had left Hawaii in 1905 to sail to London, Stewart uprooted and moved to Liberia, Africa, in 1906. As a mature man in his fifties, Stewart moved more cautiously within Liberian political circles than he had as a young Black leader in the 1880s. This discretion proved to be a wise strategy. In addition to being part of the Liberian government’s inner circle of leadership, T. McCants Stewart also had the ear of the president, Arthur Barclay. President Barclay invited Stewart to organize the Liberian National Bar Association and write the revised statutes for the Republic of Liberia. Stewart also conducted diplomacy for President Barclay with foreign nations, functioning like a secretary of state, requesting loans, and encouraging economic development. Stewart also attempted to encourage African Americans in the United States to migrate to Liberia in larger numbers, a strategy that had never met with much success.Footnote 22

Stewart’s loyalty and service to the president of Liberia was rewarded with a choice of two political appointments: the cabinet position of secretary of education or a seat on the Liberian Supreme Court. In 1911, at a time when racism, xenophobia, and disfranchisement were at a fever pitch in the United States, Stewart accepted the invitation to become an associate justice of Liberia’s Supreme Court. No Black American in the United States would be considered for a similar judicial appointment until 1965, when Thurgood Marshall was nominated for the U.S. Supreme Court by President Lyndon B. Johnson.Footnote 23

Stewart’s tenure on the Liberian Supreme Court, however, was short-lived. Within three years he had fallen out of favor with both the Liberian legislature and President Barclay and was removed from his position by joint resolution of the two houses of the legislature. Although the peripatetic Black leader attempted to exonerate himself in the court of public opinion, his star had fallen as quickly as it had risen.Footnote 24

Members of the “Talented Tenth,” like most professional parents, irrespective of racial restrictions that they were certain to encounter, had high hopes for their children. This was especially true for the sons of Black leaders, who frequently struggled to forge successful careers when they operated in the shadow of their more famous fathers.Footnote 25 As an ordained Methodist minister, Stewart expected his children, above all, to be devout. It was essential, he informed them, “that the bible be made your rule of conduct and Christ your example. To be good should be the chief aim of your life every day; and the best time to begin is now.” The elder Stewart encouraged his two sons, McCants and Gilchrist, to read the bible regularly, and he was certain that if they followed his advice that they would find tranquility and good fortune.Footnote 26 This moral-laden advice, which appeared frequently between the family patriarch and his sons, was absent between Stewart and his four daughters, suggesting differing expectations and perhaps a less assertive role that they would play in their communities.Footnote 27

McCants and Gilchrist also exemplified their father’s commitment to racial betterment and community service and rejected white society’s view of African Americans as an inferior, degraded caste. They also led equally interesting, although occasionally tragic lives. McCants, the eldest son, grew up in South Carolina, and was groomed to follow in the footsteps of his father. A bright, precocious, and often mischievous young boy, McCants and his younger brother Gilchrist attended Claflin University, a Historically Black College located in Orangeburg, South Carolina, and founded by northern missionaries to educate the freedmen after the Civil War, before enrolling in the Tuskegee Institute, the industrial school established by Booker T. Washington in 1881. Both boys rebelled against the authoritarian leadership of Washington, who ruled Tuskegee with an iron fist, and the school’s rigid structure. Each, however, would fall into line over time, and Washington, a close friend of Stewart more than a decade before he delivered his famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech, also served as a surrogate father to McCants and Gilchrist. As Stewart assured his sons, Booker T. Washington was “a warm personal friend of mine,” and he “will be a father to you.”Footnote 28 Yet Stewart had other reasons to send his sons to Tuskegee. It was far more prestigious than Claflin or most Black colleges and universities during the Gilded Age, and Stewart, like Booker T. Washington, believed that the future and the best hope for African Americans lay in the South. “I see very little hope for the Negro out of it,” he wrote.Footnote 29

After graduating from Tuskegee in 1896, the year of the famous Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which legalized segregation and established the separate-but-equal doctrine, young McCants attempted to fulfill his personal obligation to succeed as well as gain the respect and admiration of his father by forging a successful legal career. In 1897, McCants attended the University of Minnesota law school, only the second African American student to be admitted. Unlike his years at Tuskegee, where McCants had been expelled for one semester for repeatedly violating school rules, he was a model law school student. McCants excelled academically at the University of Minnesota, wrote for the school newspaper, and was an active member of the Kent Literary Society. In only one instance did he record disparate treatment because of his race, after a white restaurant proprietor refused to serve him and other Black customers. This one deplorable racial episode, notwithstanding, Stewart graduated from the University of Minnesota and became an active member of its small Black leadership class.Footnote 30 [Figure 2]

Fig. 2. McCants Stewart sitting with arms folded, photographer and date unknown, image ID 097_S-030-555_198, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

McCants Stewart’s time in Minneapolis, however, was brief, for in 1902, he left the Twin Cities and moved to Portland, Oregon, where he attempted to build a legal practice and start a new life. Disregarding his father’s advice to move to the Philippines, where, in his father’s opinion, he could practice law, “grow up with your new country and at 60 have your nest egg,” McCants struck out in a new direction. The young Black attorney was admittedly fighting an uphill battle as Portland, Oregon, like most west coast urban centers, attracted a small Black population less than 1 percent of the state’s total before World War II. Yet McCants was as optimistic as his father had been when he left New York and moved to Hawaii in 1898 searching for greener pastures.Footnote 31

The young Black attorney confronted a grim and dark reality as he navigated Portland’s legal community. White attorneys throughout the state of Oregon were reluctant to either hire Black attorneys or to offer them senior positions as partners in their law firms, so the majority struggled to earn a living. McCants Stewart was no exception. Nor did the young Black attorney’s wife, Mary Delia Weir, whom he married in 1905, and had earned degrees from the University of Minnesota and the Manning College of Music, Oratory, and Language, work outside of the home to help supplement his meager income. The birth of their daughter Katherine in 1906, no doubt, made his financial situation even more precarious.Footnote 32

Perhaps the one bright spot during McCants’s fourteen years that he lived and practiced law in Portland was his racial activism. Following in the footsteps of his more famous father, McCants challenged both legal and de facto segregation in Portland and throughout the state of Oregon. In his most important legal case, Taylor v. Cohn (1906), McCants represented a Black Pullman porter who had been denied an opportunity to occupy a box seat in a Portland theater solely because of his race. The case challenged Oregon’s public accommodation law, and the Oregon supreme court sided in favor of McCants and his client.Footnote 33

This significant legal victory notwithstanding, Black attorneys such as McCants in Portland or throughout the Pacific Northwest were in no position to capitalize on their success in the courtroom. Unlike white attorneys, who used a much larger network of connections to obtain political appointments, Black attorneys, with rare exceptions, seldom were appointed to but the most menial positions such as sergeant-at-arms or notary publics. McCants’s desire to become Portland’s public defender, a position that he coveted and would have guaranteed a modicum of financial security, was therefore unrealistic in an era when Black leaders had little political capital with which to bargain.Footnote 34

So, what happened to this bright, young, well qualified Black attorney who decided to stake out his future in the far west? First, misfortune struck. In a freak accident, McCants slipped while running to board a streetcar and mangled one of his legs severely. Eventually the leg had to be amputated. Shortly thereafter, McCants began to have difficulty with his vision and feared that he would ultimately lose his sight. Although neither of these ailments halted his legal career, they each hurt his confidence and thereby hindered his already struggling practice.Footnote 35

McCants’s legal career began floundering in Portland, so he decided to relocate to San Francisco in 1917. Like Portland, San Francisco also had a small Black population that numbered a mere 1,642 black residents in 1910 and, like Portland or Seattle, located approximately 174 miles to the north, the Black professional class was miniscule. But taking a page out of his father’s book, McCants did not fault racism for his predicament, but rather the declining economy in Oregon and the Pacific Northwest. “We are suffering here in this section of the country. The slump seemingly has come to stay,” he wrote to an old friend about his status.Footnote 36 Upon his arrival in San Francisco, McCants formed a partnership with Oscar Hudson, a respected Black attorney and the first African American admitted to membership in the San Francisco and California bar associations. Hudson was McCants’s senior and served as a de facto mentor. He was also well established in the legal community, and McCants had hoped to ride his coattails through this challenging financial period.Footnote 37

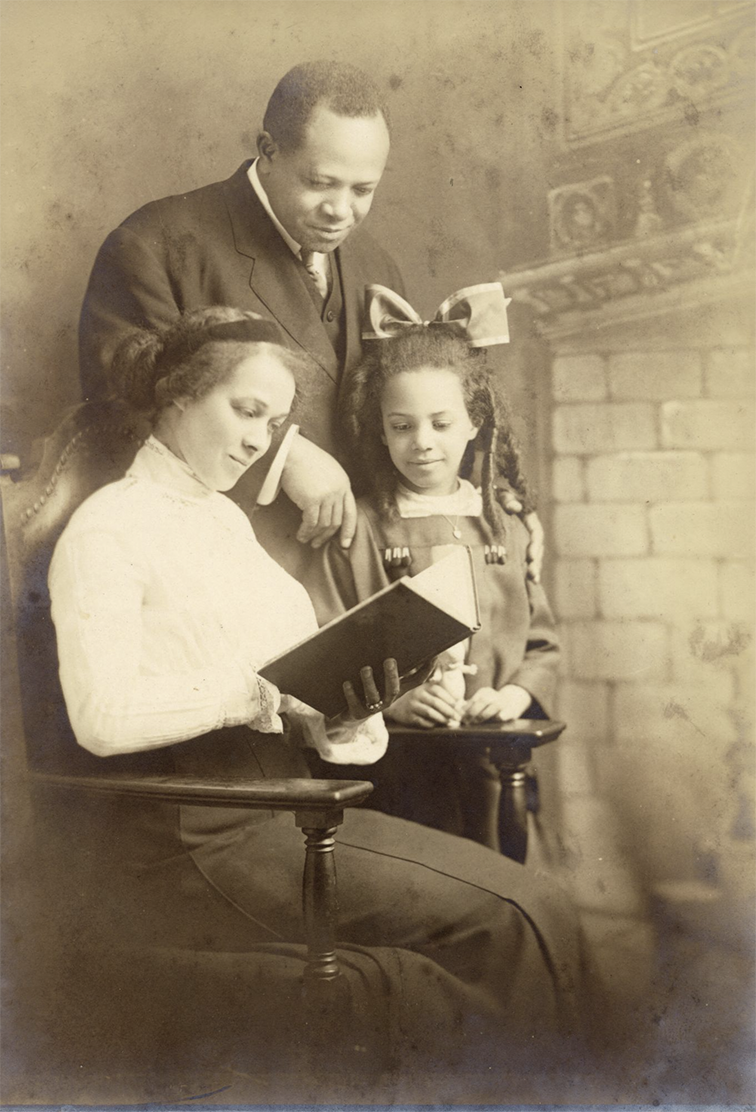

Although destitute, McCants was optimistic that his career would improve over time. Unfortunately, it never did. Black attorneys were barred as assistants, clerks, or partners in most white law firms in the San Francisco Bay Area and throughout the state of California.Footnote 38 Given the situation in San Francisco, McCants also had difficulty earning a living there. He informed his young daughter Katherine in an anguished letter that his financial circumstances were dire, that his savings account contained only $5, and he had no immediate prospect of earning additional revenue. On a spring day in April 1919, McCants, whose future appeared so full of promise when he graduated from the University of Minnesota Law School in 1899, in a fit of resignation and total despair, committed suicide, leaving behind a wife, daughter, and numerous debts.Footnote 39 [Figure 3]

Fig. 3. McCants Stewart and Family (Mary Delia Stewart and Katherine Stewart), Photographer and date unknown, Image ID 097-S-0310564_251, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

Although grief-stricken, the remaining members of the Stewart family persevered. T. McCants Stewart, the family patriarch, would survive his eldest son by four years and none of his surviving correspondence mentioned his feelings surrounding his son’s suicide. As restless in his old age as he had been in his youth, Stewart had moved to the U.S. Virgin Islands in 1921, after returning to London following his ouster from Liberia’s Supreme Court. There, he established a joint legal practice with Christopher H. Payne, a noted Black attorney. Payne, a native of West Virginia, had been appointed U.S. consul to the Virgin Islands by President Theodore Roosevelt. Thereafter, he became a prosecuting attorney and a police judge for the district of Frederiksted, St. Croix. Payne and Stewart, who now relished his role as an elder statesman, established a successful legal practice on the island of St. Thomas.Footnote 40

Gender and racial obligation

The Stewart family possessed many remarkable women who shared the family’s proud tradition of racial service and betterment, while also attempting to advance their professional careers during an era when Black women were marginalized even more than Black men. Dr. Verina Morton-Jones, for example, a graduate of the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, regarded as one of the leading medical schools for women in the nation, earned a medical degree in 1888 during a time when it was rare for a woman of any race to attend medical school. Morton-Jones became a suffragette, a settlement-house worker, a cofounder of the National Urban League, and an active member of the National Association of Colored Women. Following the example of many Black professional women, Morton-Jones was also a pivotal figure in the colored YWCA in Brooklyn, New York.Footnote 41 But Carlotta Stewart, who accompanied her father, T. McCants Stewart to Hawaii in 1898, excelled as a Black professional woman, in part because of her bold, pragmatic choices and an independent streak that she possessed as a young woman.

Unlike her brothers, who were born in South Carolina, Carlotta was born in New York, and spent her formative years in Brooklyn, where she attended integrated schools and lived and operated in an integrated society. Residing in Hawaii, no doubt, represented a stark contrast with New York. Carlotta’s migration to Hawaii was unique in several other important respects: aside from a handful of Black female missionaries, virtually no African American women came to Hawaii in the nineteenth century. In fact, few African Americans at all lived in Hawaii prior to World War II, and the territory’s Black population did not exceed one thousand residents until the 1950 census. Therefore, the number of African Americans in Hawaii before World War II may well have been too small to constitute a cohesive community. [Figure 4]

Fig. 4. Young Carlotta Stewart sitting in a chair, photographer and date unknown, image ID 097-S-030-548_147, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

These factors did not phase or deter Carlotta in the least. Rather, she looked at her new environment through the eyes of a young woman who had made a conscious decision to come to a new land where she might not only pursue her education but also fresh opportunities. In a word, Carlotta Stewart arrived in Hawaii as someone who expected or knew she had a future. Carlotta attended Oahu College (the Punahou School), where she played on the school’s basketball team, served as member of the school’s literary society, majored in English, and completed a rigorous course of study.Footnote 42

By all indications, Carlotta was well-adjusted and enjoyed her years at Oahu College. After graduation in 1902, Carlotta completed the requirements for a normal school certificate, after which she promptly accepted a teaching position. For the next four decades Carlotta Stewart made steady advancement in her professional career and served as a highly respected teacher and principal on the islands of Oahu and Kauai. Carlotta’s achievements as a Black professional were particularly striking for a woman in a society where African Americans had no political influence because of their small numbers to request or demand jobs of this magnitude. What is equally striking is that Carlotta Stewart was more likely to obtain a professional position in Hawaii as an elementary school teacher and, later, as a principal, than in many West Coast cities such as San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, Portland, and Seattle. Teaching and administrative jobs would not become available to African Americans in most far western cities until the 1940s and during the postwar era.Footnote 43

To merely suggest that Carlotta enjoyed her life in Hawaii constituted an understatement. She was respected as a professional and a colleague, had a supportive network of friends, and loved living and working in the tranquil environment of Oahu and Kauai. Nor did she face the systemic racism, de facto discrimination, or racial violence that African Americans faced on the mainland. Carlotta, unlike her older brother McCants or her father, never reported a single instance of racial discrimination during her residence in Hawaii. She resided in an integrated neighborhood in Oahu and later purchased a comfortable home in Kauai without incident. Moreover, her teaching and administrative salary was sufficient to support her lifestyle in Hawaii, but also to provide limited financial assistance to her two brothers. On at least one occasion, following the panic of 1907, Carlotta contemplated leaving Hawaii for a job on the mainland. The move would have made perfect sense on one level: she would have been closer to a family member rather than three thousand miles away. After weighing her options, however, Carlotta informed her brother McCants, who was having his own trouble in Portland, Oregon: “the thought of staying out here [in Hawaii] three or four years longer wears on me at times. But I am perfectly sensible about it now, as I see the situation east. I would not leave now for anything.”Footnote 44

These were powerful words, and particularly so for an African American woman who had few Black peers to interact with in her community. Carlotta’s decision to remain in Hawaii, rather than relocate to the west coast, reflected her pragmatic approach to most problems and worked to her advantage. Within two years, the young Black teacher had been promoted to principal of the Koolau Elementary School and earned an increase in salary. In the space of just seven years, Carlotta had set down roots, gained the respect of her peers and colleagues, and been promoted to principal of a multiracial school. These achievements, while neither noteworthy nor exceptional in some northern cities or in the Jim Crow South, where Black teachers and administrators were in ample supply, were impressive in a society like Hawaii with a small Black community and where Blacks could exert little, if any, political power to demand white-collar and professional employment.Footnote 45

Surviving records and photographs of Carlotta Stewart’s employment between 1902 and 1940 reveal that her students reflected the rich racial and ethnic diversity of the islands. A revealing photo of Carlotta as a teacher in 1928 shows her posing with her students in traditional Hawaiian dress at the Anahola School. Similarly, Carlotta poses with a smaller class of students of all races in a class photo when she served as principal of the Hanamaulu School in 1933. That year, Carlotta’s students included Hawaiians, Japanese, Filipinos, Koreans, Chinese, and Portuguese. Sixteen white students were also listed in school records, but no African American students, a reflection that few school-aged Blacks lived in Hawaii prior to World War II. Carlotta’s responsibilities as principal included supervising classroom teachers, the school librarian, the cafeteria manager, and teaching English.Footnote 46 [Figure 5]

Fig. 5. Carlotta Stewart Lai, principal, Hanamaulu School, photographer unknown, June 1933, image ID, 097-S-030-554_188, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

Carlotta Stewart attempted, with limited success, to compliment her successful career as a Black professional woman with an eligible partner. The odds were not in her favor. Indeed, Hawaii’s Black population had grown since Carlotta first arrived on the island of Oahu in 1898. But a handful of Black professionals did not comprise a community. Carlotta’s options were understandably limited if she chose to marry within her race. So she married Yun Tim Lai, a man of Chinese ancestry in 1916, at Anahola, Kauai County.Footnote 47 Mixed-race marriages were both legal and tolerated in Hawaii, so long as Blacks did not marry whites. Lai, who was five years younger than Carlotta, worked as sales manager of the Garden Island Motors, Ltd., an automobile dealership in Lihue, Kauai. The union was presumably a happy one, but it produced no children, and her husband died unexpectedly in Hong Kong while visiting his parents in 1935. Because Carlotta rarely mentioned her husband in her personal correspondence, no details regarding his death have ever surfaced.Footnote 48 Carlotta Stewart Lai never remarried, for reasons she did not disclose, but remained in Hawaii for the next seventeen years, where she had a strong network of friends and professional associates to sustain her, and where she dedicated herself to her students. Carlotta retired in 1945 after a distinguished career in public education that spanned over four decades. Like her father, T. McCants Stewart, she chose to live her final years in a U.S. territory rather than return to the mainland, where her professional opportunities were more limited and racial discrimination was ubiquitous. And although Carlotta Stewart Lai never expressed the pessimism that her father wrote about the future of U.S. race relations in his latter years, she concluded early in her professional career that living and working as a Black professional woman in Hawaii offered opportunities that she could not obtain on the American mainland. Thus, she remained in Hawaii until her death in 1952.Footnote 49

Conclusions

No one family of any race, nationality, or ethnicity, including the Stewarts, to be sure, can speak to the larger group. People are too complex to be reduced to simplistic racial or ethnic categories, and these broad generalizations often fail to account for class differences and the way individuals within families understand their peculiar circumstances and respond to both opportunity and adversity. The Stewarts were reared and educated during the era of Jim Crow, lynching, and restricted opportunities for African Americans in every region of the nation. Yet their search to find a place in American society led them think outside of the box, so to speak, and to strike out to pursue opportunities in nations, regions, and territories where relatively few African Americans had either migrated to or resided. As historian Kendra T. Fields demonstrated effectively in her book, Growing Up with the Country: Family, Race, and Nation after the Civil War,Footnote 50 painting the black struggle or individual families with a broad brush can be problematic, and it undermines the agency of these individuals and the creative and unorthodox approaches that individuals and family members used to set new goals and to meet collective obligations. Understanding Black families in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era on their own terms and evaluating their unique experiences will help historians illuminate many new strategies, goals, and expectations that they may have ignored or minimized. Some families, such as the Stewarts, do not fit into neat categories and defy familiar Black tropes. It is important, therefore, for historians, as Leon Litwack demonstrated in his monumental study of African Americans in the wake of emancipation, Been in the Storm So Long, The Aftermath of Slavery, to listen to the distinctive voices of individuals and Black families, and to study these individuals on their own terms.Footnote 51