Introduction

Armenian (![]() or

or ![]() , /hɑjeˈɾen/, ISO 639-1 hy) comprises an independent branch of the Indo-European language family.Footnote 1 Its earliest attested ancestor is Classical Armenian in the fifth century CE (see Godel Reference Godel1975; Thomson Reference Thomson1989; DeLisi Reference DeLisi2015; Macak Reference Macak2016). Modern Armenian is classified into two dialect families: Eastern Armenian (ISO 639-3 hye) and Western Armenian (ISO 639-3 hyw). Eastern Armenian is spoken in modern-day Armenia, and large speaker communities also exist in Georgia, Russia and Iran (shown in Figure 1). Western Armenian was historically spoken in the Ottoman Empire, but now includes varieties spoken throughout the Armenian diaspora in the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas (Donabédian Reference Donabédian and Bulut2018). There are substantial Western Armenian speaker communities in Turkey (Istanbul), Lebanon (Beirut), Syria (Aleppo, Damascus), California (Fresno, Los Angeles County), France (Marseilles), Australia (Sydney) and Argentina (Buenos Aires). There are also recent diaspora communities of Eastern Armenian speakers in California (Karapetian Reference Karapetian2014), as well as communities of Western Armenian speakers in Armenia who escaped the Armenian genocide during World War I, who repatriated after World War II, or who fled the ongoing Syrian civil war. UNESCO lists Western Armenian as an endangered language in Turkey, and there are significant language promotion efforts in many diaspora communities that are intended to combat declining use by speaker generations born in the Americas and Europe (Al-Bataineh Reference Al-Bataineh2015; Chahinian & Bakalian Reference Chahinian and Bakalian2016).

, /hɑjeˈɾen/, ISO 639-1 hy) comprises an independent branch of the Indo-European language family.Footnote 1 Its earliest attested ancestor is Classical Armenian in the fifth century CE (see Godel Reference Godel1975; Thomson Reference Thomson1989; DeLisi Reference DeLisi2015; Macak Reference Macak2016). Modern Armenian is classified into two dialect families: Eastern Armenian (ISO 639-3 hye) and Western Armenian (ISO 639-3 hyw). Eastern Armenian is spoken in modern-day Armenia, and large speaker communities also exist in Georgia, Russia and Iran (shown in Figure 1). Western Armenian was historically spoken in the Ottoman Empire, but now includes varieties spoken throughout the Armenian diaspora in the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas (Donabédian Reference Donabédian and Bulut2018). There are substantial Western Armenian speaker communities in Turkey (Istanbul), Lebanon (Beirut), Syria (Aleppo, Damascus), California (Fresno, Los Angeles County), France (Marseilles), Australia (Sydney) and Argentina (Buenos Aires). There are also recent diaspora communities of Eastern Armenian speakers in California (Karapetian Reference Karapetian2014), as well as communities of Western Armenian speakers in Armenia who escaped the Armenian genocide during World War I, who repatriated after World War II, or who fled the ongoing Syrian civil war. UNESCO lists Western Armenian as an endangered language in Turkey, and there are significant language promotion efforts in many diaspora communities that are intended to combat declining use by speaker generations born in the Americas and Europe (Al-Bataineh Reference Al-Bataineh2015; Chahinian & Bakalian Reference Chahinian and Bakalian2016).

Figure 1 Map of the distribution of Armenian in the Southern Caucasus (CC-BY-SA 4.0 figure created by Wikimedia Commons user GalaxMaps, retrieved June 20, 2021).

Each of the two dialect families has dozens of documented varieties (Adjarian Reference Adjarian1909; Vaux Reference Vaux1998:ch1.1; Sayeed & Vaux Reference Sayeed, Vaux, Klein, Joseph and Fritz2017).Footnote 2, Footnote 3 Instrumental phonetic research on the Armenian languages began with Adjarian Reference Adjarian1899, which first proposed the concept of voice onset time to differentiate plosive voicing contrasts prior to its independent development in Lisker & Abramson Reference Lisker and Abramson1964 (Khachatryan & Airapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Airapetyan1987; Braun Reference Braun2013). Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988 provides a detailed phonetic description of Eastern Armenian including acoustic measurements, palatography, tracings of mid-sagittal X-ray images of the vocal tract, and discussion of perceptual experiments. Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971 report instrumental articulatory and acoustic descriptions of Eastern Armenian consonants. Both works focus on a high-register literary variety spoken by students and broadcast announcers. Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948, Johnson Reference Johnson1954, and Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009 are general linguistic grammars of standardized Eastern and Western dialects with substantial phonetic material, and Allen Reference Allen1950 is a phonetic description of an Eastern Armenian speaker who had grown up in Iran.

This illustration describes and compares the phonetics of two Armenian varieties: the Western variety spoken in Beirut, and the Eastern variety spoken in modern Yerevan and surrounding regions. The Beirut Western Armenian recordings were made by Hossep Dolatian (HD), a twenty-eight-year-old male speaker who was born in Beirut, Lebanon. He grew up in an Armenian-speaking community in Beirut and moved to the USA at the age of twenty-one. In addition to Western Armenian, he is fluent in English and has advanced proficiency in Arabic. His recordings were made with a stand-mounted MXL 770 microphone in a quiet environment. The Yerevan Eastern Armenian recordings were made by Susanna Khechoyan (SK), a fifty-six-year-old female speaker who was born in Artsvashen. She lived in Yerevan, Armenia from the age of six up to thirty-eight, and has lived in Los Angeles since then. She grew up speaking Eastern Armenian and continues to use it daily, and also speaks English fluently and has advanced proficiency in Russian. She taught Armenian as an elementary school teacher in Armenia for twelve years. Her recordings were made with a head-mounted Shure SM10A microphone in a sound isolation booth.

One coauthor, Tabita Toparlak (TT), grew up speaking Western Armenian and Turkish in Istanbul and also speaks French and English. Another coauthor, Peter Guekguezian (PG), identifies as a heritage speaker of Western Armenian with intermediate proficiency and grew up in the western USA speaking English as a first language. When we had metalinguistic questions about pronunciation, we also discussed them with several other Eastern and Western Armenian speakers that we knew in the USA, Canada, Istanbul, Yerevan and Beirut. The speakers who contributed recordings, judgments and commentary to this illustration are Armenian language instructors, linguistics researchers and educated professionals in other fields. As such, the Armenian varieties that we describe are high-register varieties. In particular, HD describes the variety in his contributed recordings as a standardized variety of Western Armenian as it is spoken in Beirut,Footnote 4 though his illustrated plosive pronunciations differ from more Arabic-dominant Western Armenian speakers still living in Beirut (discussed in Beirut Armenian plosives; see also Godson Reference Godson2004; Kelly & Keshishian Reference Kelly and Keshishian2021; Tahtadjian Reference Tahtadjian2021).

Consonants

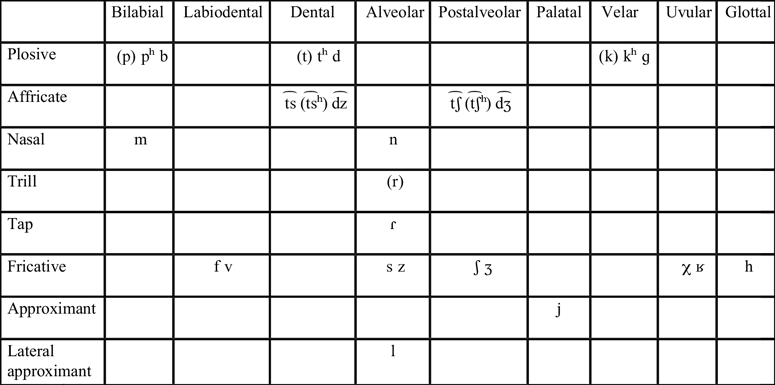

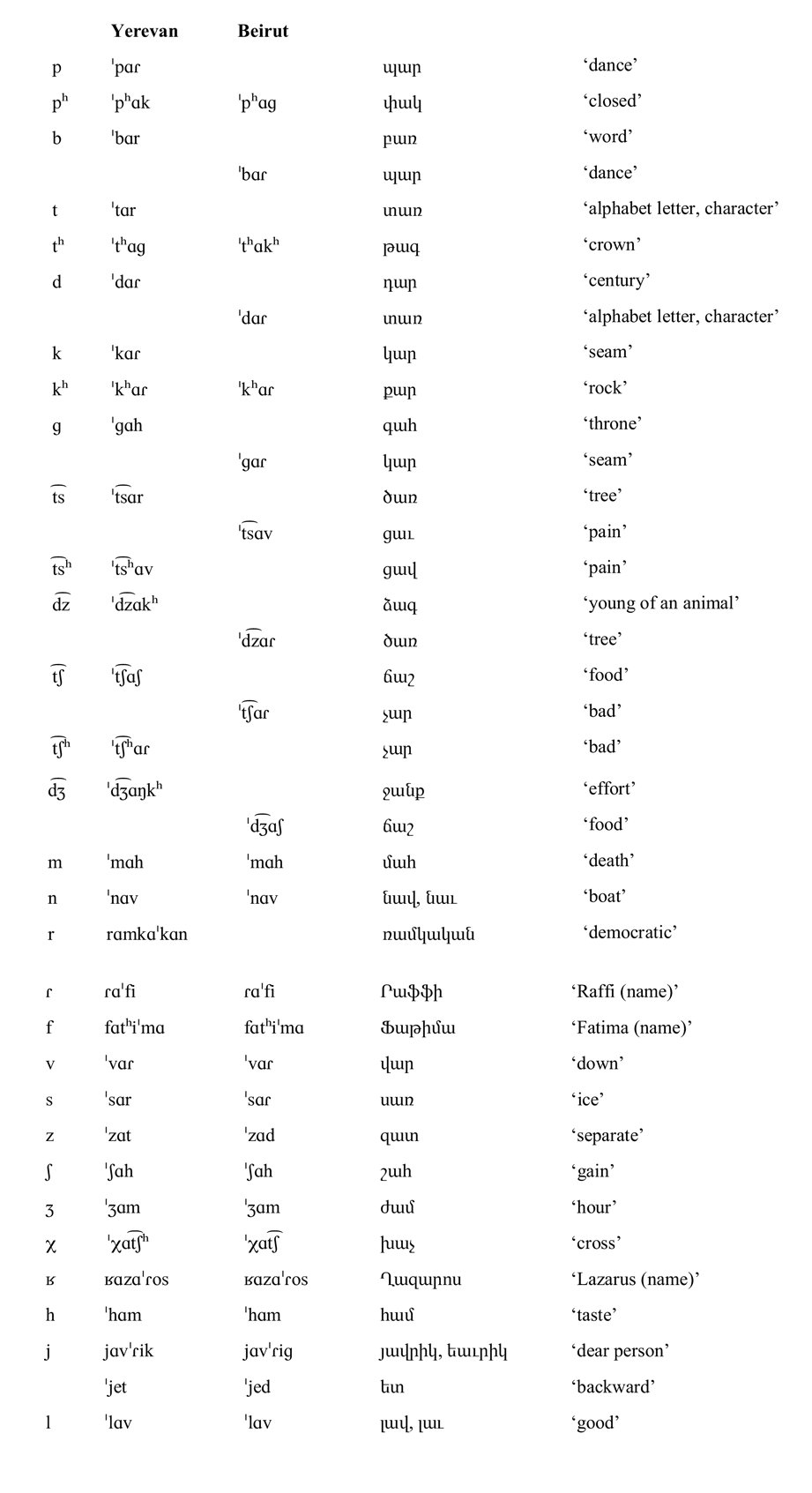

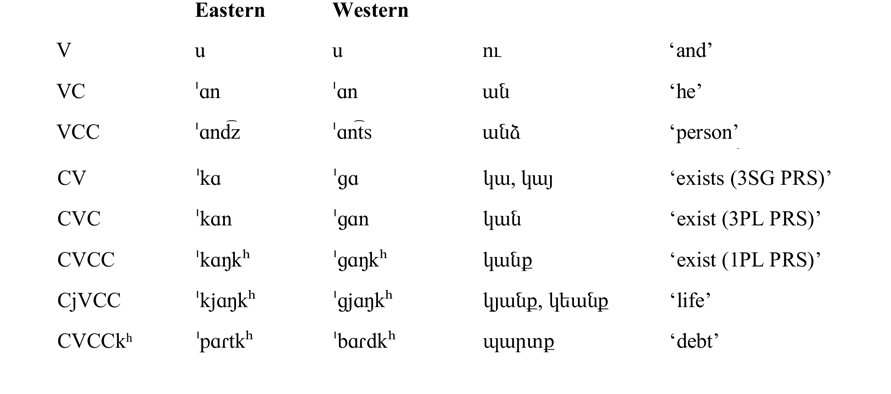

The consonant inventory of the two Armenian varieties is given in the ‘Consonants’ table above (see also Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 85; Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 16; Dum-Tragut, Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 13). Consonants in parentheses are found only in Yerevan Armenian. Yerevan Armenian and most Eastern varieties have a three-way laryngeal contrast for plosives and affricates (voiced, voiceless unaspirated and voiceless aspirated), while Beirut Armenian and most Western varieties make only a two-way distinction for these sounds (Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 7ff). Yerevan Armenian also has a phonemic trill, which is merged to the tap in Beirut Armenian.Footnote 5

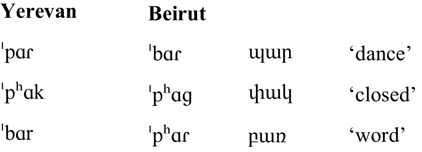

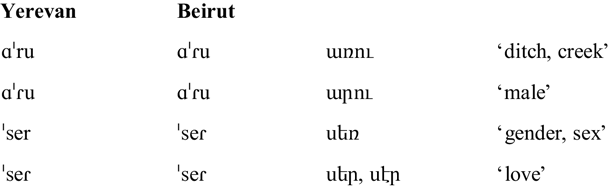

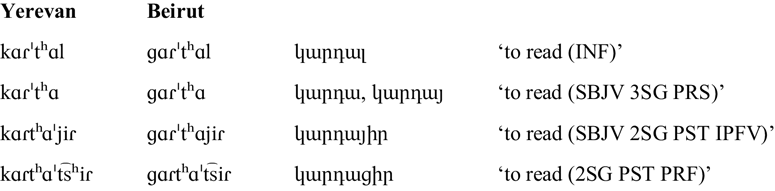

The Yerevan voiceless unaspirated plosives correspond with Beirut voiced ones, and the Yerevan voiced plosives correspond with Beirut aspirated ones (Baronian Reference Baronian2017). These correspondences are shown below for labial plosives in word-initial position. The orthography is given with the Soviet-era reformed system that is currently used in Armenia. In cases where this differs from the Classical orthography used by the Western Armenian diaspora, the Classical orthography is listed second.

Plosive correspondences in Yerevan and Beirut Armenian

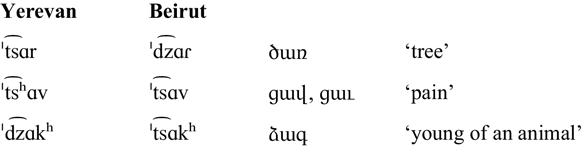

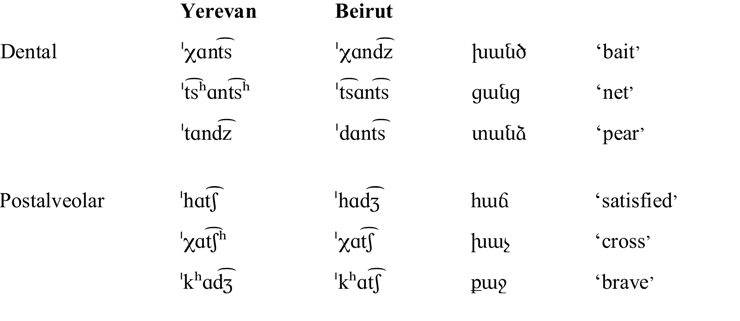

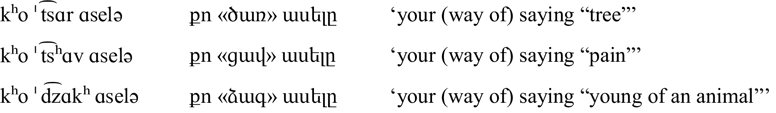

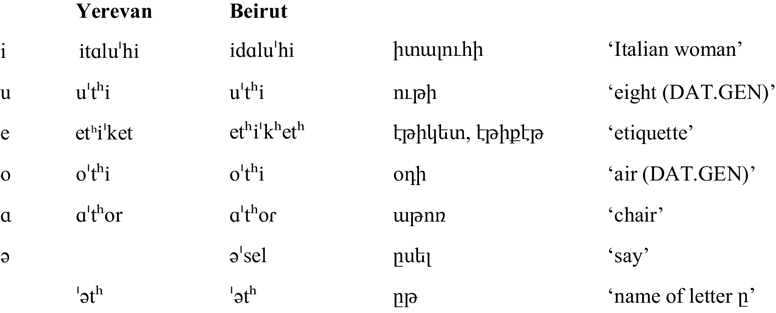

Like the plosives, the Yerevan voiceless unaspirated affricates correspond with Beirut voiced ones, but Yerevan voiceless aspirated and voiced affricates are both voiceless unaspirated in HD’s Beirut Armenian variety. These correspondences are shown below for dental affricates in word-initial position.

Affricate correspondences in Yerevan and Beirut Armenian

Plosives and affricates in recent loanwords do not respect these correspondences. In recent loanwords, these sounds are typically borrowed using the same pronunciation (voicing or aspiration) in both dialects, and are spelled differently in each dialect. For example, the borrowed city name /bejˈɾutʰ/ ‘Beirut’ has a word-initial voiced plosive in both Yerevan and Beirut Armenian, but is spelled ![]() in the Eastern orthography and

in the Eastern orthography and ![]() in the Western orthography. The accompanying recording of the Yerevan form was contributed by Vahagn Petrosyan (VP), a thirty-five-year-old male speaker who has lived in Yerevan since birth.

in the Western orthography. The accompanying recording of the Yerevan form was contributed by Vahagn Petrosyan (VP), a thirty-five-year-old male speaker who has lived in Yerevan since birth.

The consonant inventory is illustrated in the table below. While almost all of the words in the table exist in both dialects, the dialectal forms that do not illustrate the target sound in each row are omitted.

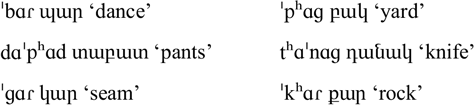

Yerevan Armenian plosives

Yerevan Armenian has three labial, three dental, and three velar plosives that contrast in both onset and coda position:

With respect to their distribution, final /b/ is very rare and attested mostly in loanwords, such as /ˈʃtɑb/ ‘headquarters’ borrowed from Russian штаб (originally German Stab).Footnote 6 The Armenian orthography does not reliably index final voicing due to diachronic change and perhaps cross-dialectal borrowings.Footnote 7 For example, the form ![]() ‘young of an animal’ (in table Affricate correspondences in Yerevan and Beirut Armenian) is written with final

‘young of an animal’ (in table Affricate correspondences in Yerevan and Beirut Armenian) is written with final ![]() . This letter typically corresponds to /ɡ/ in Yerevan Armenian and /kʰ/ in Beirut Armenian, but this word is pronounced /ˈd͡zɑkʰ/ in Yerevan and /ˈ t͡sɑkʰ/ in Beirut with the same final voiceless aspirated plosive in both varieties.

. This letter typically corresponds to /ɡ/ in Yerevan Armenian and /kʰ/ in Beirut Armenian, but this word is pronounced /ˈd͡zɑkʰ/ in Yerevan and /ˈ t͡sɑkʰ/ in Beirut with the same final voiceless aspirated plosive in both varieties.

Some Yerevan Armenian speakers report a (lamino-)alveolar pronunciation of the dental /d, t, tʰ/ plosives, such as for the accompanying recording of /tʰəˈtʰu/ ![]() ‘sour’ contributed by speaker VP. The velar /k/ plosive can be placed farther back toward [k̠, q]. This is illustrated in the accompanying recording of /ˈkoʁ/

‘sour’ contributed by speaker VP. The velar /k/ plosive can be placed farther back toward [k̠, q]. This is illustrated in the accompanying recording of /ˈkoʁ/ ![]() ‘rib’ pronounced [k̠oʁ], which was contributed by a twenty-year-old female speaker of Eastern Armenian who grew up in Yerevan. This pronunciation is optional, and the X-ray tracings in Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988 show a clearly velar [k] between two /ɑ/ vowels.

‘rib’ pronounced [k̠oʁ], which was contributed by a twenty-year-old female speaker of Eastern Armenian who grew up in Yerevan. This pronunciation is optional, and the X-ray tracings in Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988 show a clearly velar [k] between two /ɑ/ vowels.

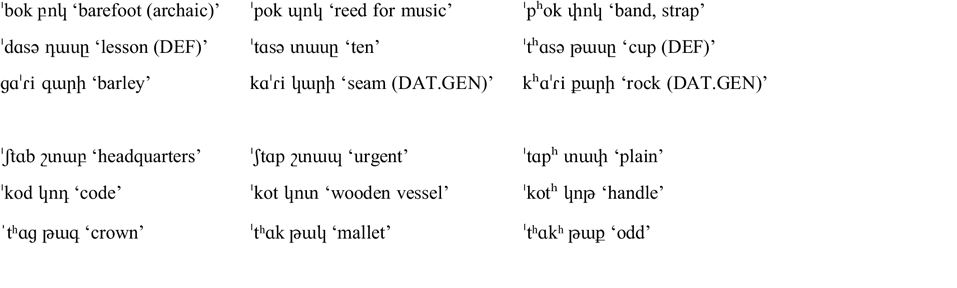

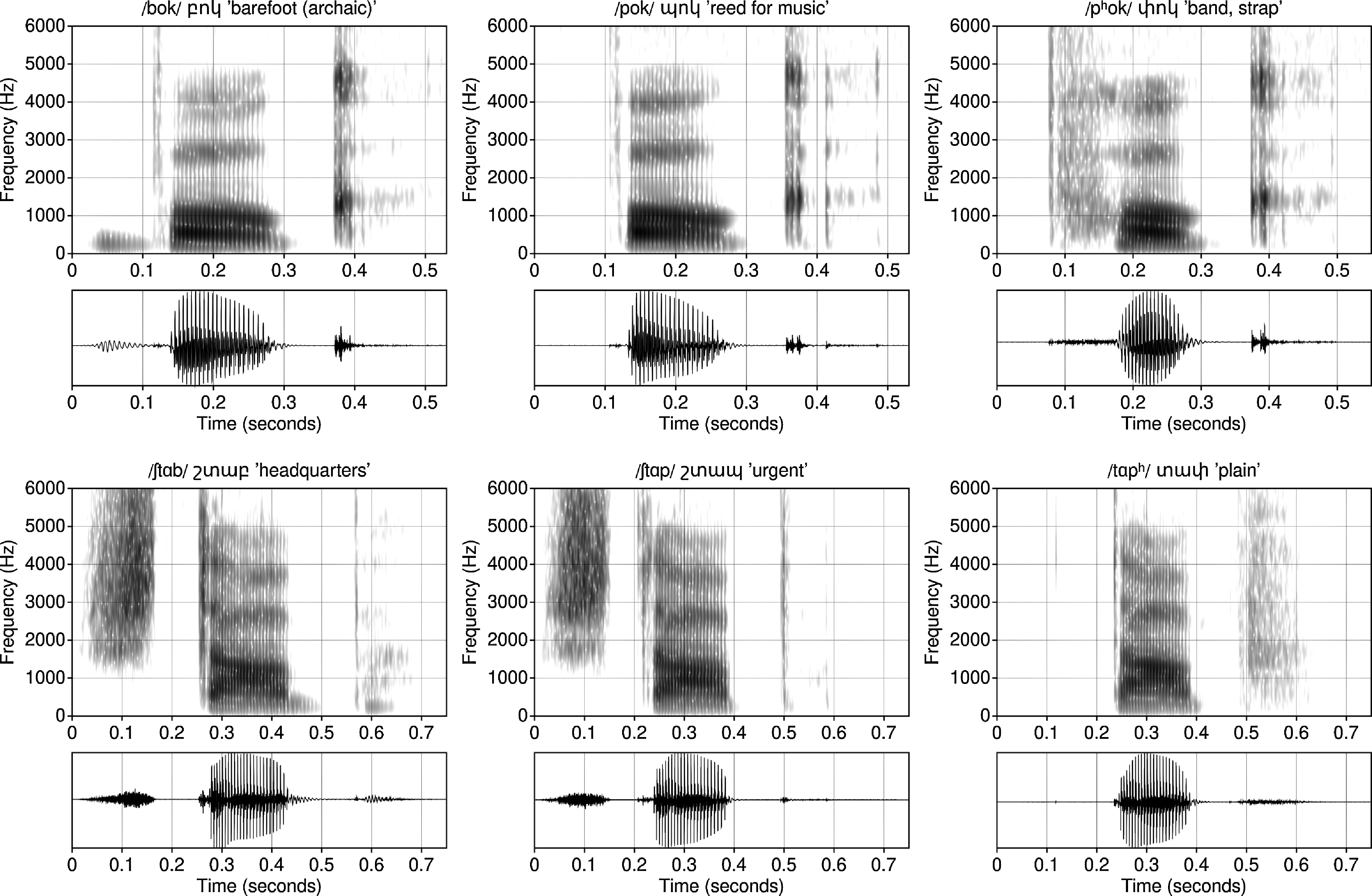

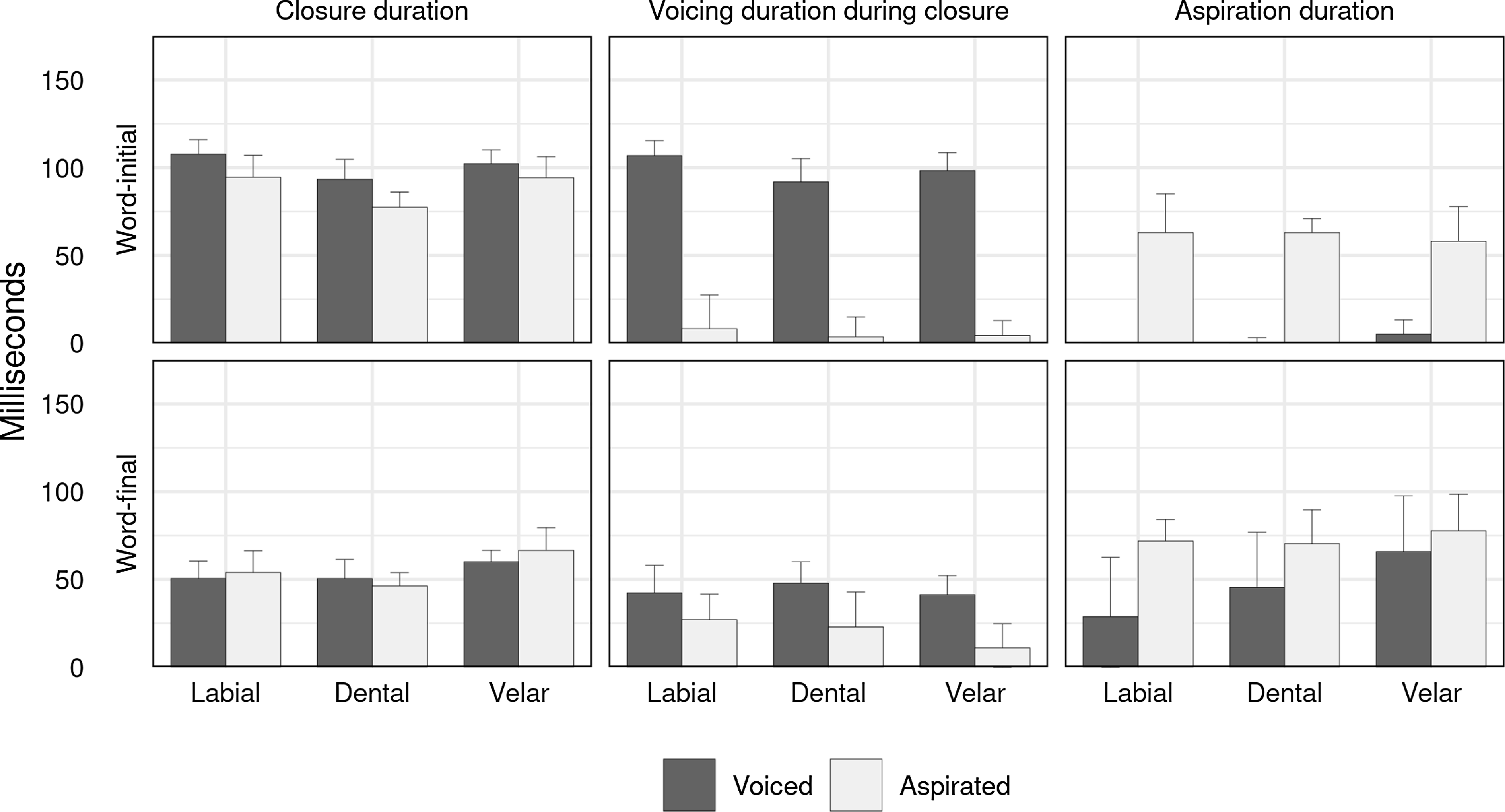

Figure 2 shows spectrograms and waveforms of SK’s recordings of the labial plosives in word-initial (upper row) and word-final (lower row) positions. Figure 3 shows the mean and standard deviation of closure duration, closure voicing duration, and aspiration duration for all nine plosives in each position. These measurements are from eight speakers who grew up in Yerevan, each reading aloud 155 unique words in a carrier phrase with nuclear accent (collected in Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018).

Figure 2 Yerevan Armenian labial plosives in words produced in isolation. Upper row shows voiced, voiceless unaspirated, and voiceless aspirated plosives in word-initial position; lower row shows the same plosives in word-final position. All spectrograms are calculated with a 5-millisecond Gaussian window and a 2-millisecond window advance.

Figure 3 Mean (filled bars) and standard deviation (whiskers) for closure duration, closure voicing duration, and aspiration duration for the nine Yerevan Armenian plosives in word-initial and word-final position, based on measurements from eight speakers in Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018. Each bar includes between 32–176 tokens.

The voiced series /b, d, ɡ/ typically has breathy voicing during the closure and could be closely transcribed as [b̤, d̤, ɡ̈] (Macak Reference Macak, Klein, Joseph and Fritz2017; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018). Seyfarth & Garellek (Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018) report that 15

![]() $\%$

of word-initial /b, d, ɡ/ tokens lack voicing during the closure; the accompanying recording of /ɡɑˈɾi/

$\%$

of word-initial /b, d, ɡ/ tokens lack voicing during the closure; the accompanying recording of /ɡɑˈɾi/ ![]() ‘barley’ contributed by SK is an example of such a token. In syllable onset position, the breathy voice quality can be measured in the initial portion of the following vowel as a louder first harmonic (2–3 dB) and lower cepstral peak prominence (1 dB) relative to the voiceless unaspirated plosives (Schirru Reference Schirru, Olander, Annette Olsen and Elmegård Rasmussen2012; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018). These measures index a more open glottis (Klatt & Klatt Reference Klatt and Klatt1990; Chai & Garellek Reference Chai and Garellek2022) with more noise during the vowel transition (Hillenbrand, Cleveland & Erikson Reference Hillenbrand, Cleveland and Erickson1994), respectively.

‘barley’ contributed by SK is an example of such a token. In syllable onset position, the breathy voice quality can be measured in the initial portion of the following vowel as a louder first harmonic (2–3 dB) and lower cepstral peak prominence (1 dB) relative to the voiceless unaspirated plosives (Schirru Reference Schirru, Olander, Annette Olsen and Elmegård Rasmussen2012; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018). These measures index a more open glottis (Klatt & Klatt Reference Klatt and Klatt1990; Chai & Garellek Reference Chai and Garellek2022) with more noise during the vowel transition (Hillenbrand, Cleveland & Erikson Reference Hillenbrand, Cleveland and Erickson1994), respectively.

Unlike the voiced aspirated consonants found in many South Asian and other languages (Berkson Reference Berkson2013; Namboodiripad & Garellek Reference Namboodiripad and Garellek2017; Esposito & Khan Reference Esposito2020; Faytak, Steffman & Tankou Reference Faytak, Steffman and Tankou2020), Yerevan Armenian breathy-voiced plosives typically lack noisy post-aspiration, at least in onset position (Khachatryan & Airapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Airapetyan1987; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018; see Figure 2 and cf. Figures 2, 14 in Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018). However, Khachaturian (Reference Khachaturian1983, Reference Khachaturian and Greppin1992) indicates that speakers of some other regional Eastern Armenian varieties produce more extended and audible aspiration after voiced plosive onsets than in the Yerevan variety. In syllable coda position, voiced plosives more often have short post-aspiration (< 50 ms in citation forms) in addition to reliable closure voicing and a longer nucleus vowel (Adjarian Reference Adjarian1899; Lisker & Abramson Reference Lisker and Abramson1964; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988; Hacopian Reference Hacopian2003; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018).

The series /p, t, k/ is voiceless without aspiration in both onset and coda position. Relative to the other two series, these plosives are characterized by a longer voiceless closure (Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018). This series is sometimes reported to be associated with glottal constriction or a glottalic airstream (e.g., Allen Reference Allen1950; Fleming Reference Fleming2000; Ladefoged & Maddieson Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996; Schirru Reference Schirru, Olander, Annette Olsen and Elmegård Rasmussen2012). The acoustic and articulatory evidence for this in contemporary Armenian varieties is mixed (see Amirian Reference Amirian2017; Toparlak Reference Toparlak2017; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018). The word-final plosives in the accompanying recordings of /ˈʃtɑp/ ![]() ‘urgent’, /ˈkot/

‘urgent’, /ˈkot/ ![]() ‘wooden vessel’, and /ˈtʰɑk/

‘wooden vessel’, and /ˈtʰɑk/ ![]() ‘mallet’ are ejectives. It seems likely that some Eastern Armenian speakers may constrict or tense the vocal folds in order to inhibit airflow and maintain a longer voiceless closure, but that this articulation is not universal or obligatory for these sounds in this Eastern variety (Allen Reference Allen1950: 188; Hacopian Reference Hacopian2003: 54–55; Khachatrian Reference Khachatrian1996; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 17–18; Toparlak Reference Toparlak2017; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018 §4.1.2). As these words were recorded in minimal triplets alongside aspirated and voiced final plosives, they probably have contrastive focus. In other languages, audible word-final glottalization can be a side-effect of overlapping constrictions or can be used to enhance a voicing contrast (e.g., Germanic: Kohler Reference Kohler1994; Gordeeva & Scobbie Reference Gordeeva and Scobbie2013; McCarthy & Stuart-Smith Reference McCarthy and Stuart-Smith2013; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2020; Brandt & Simpson Reference Brandt and Simpson2021), which may also be the case here.

‘mallet’ are ejectives. It seems likely that some Eastern Armenian speakers may constrict or tense the vocal folds in order to inhibit airflow and maintain a longer voiceless closure, but that this articulation is not universal or obligatory for these sounds in this Eastern variety (Allen Reference Allen1950: 188; Hacopian Reference Hacopian2003: 54–55; Khachatrian Reference Khachatrian1996; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 17–18; Toparlak Reference Toparlak2017; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018 §4.1.2). As these words were recorded in minimal triplets alongside aspirated and voiced final plosives, they probably have contrastive focus. In other languages, audible word-final glottalization can be a side-effect of overlapping constrictions or can be used to enhance a voicing contrast (e.g., Germanic: Kohler Reference Kohler1994; Gordeeva & Scobbie Reference Gordeeva and Scobbie2013; McCarthy & Stuart-Smith Reference McCarthy and Stuart-Smith2013; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2020; Brandt & Simpson Reference Brandt and Simpson2021), which may also be the case here.

The other voiceless series /pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/ is defined by post-aspiration in both syllable onset and coda positions, along with a correspondingly higher f0 during the initial portion of a following vowel in onset position (Allen Reference Allen1950; Lisker & Abramson Reference Lisker and Abramson1964; Khachatryan & Airapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Airapetyan1987; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988; Hacopian Reference Hacopian2003; Schirru Reference Schirru, Olander, Annette Olsen and Elmegård Rasmussen2012; Toparlak Reference Toparlak2017; Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018). Yerevan Armenian is thus typologically rare in that it maintains a three-way voicing and aspiration contrast in both initial and final position using virtually the same acoustic cues in both positions (Hacopian Reference Hacopian2003).

Beirut Armenian plosives

Western Armenian is described as having a two-way contrast between voiceless aspirated and voiced plosives (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948; Vaux Reference Vaux1998; Baronian Reference Baronian2017).

Among Western Armenian speakers in Anglophone Canada and the USA, the voiceless plosives are aspirated, and the other plosive series varies phonetically between voiceless unaspirated and voiced (Kelly & Keshishian Reference Kelly and Keshishian2021; Tahtadjian & Kochetev Reference Tahtadjian and Kochetev2021; Tahtadjian Reference Tahtadjian2021; also compare to Balabanian Reference Balabanian2020 with Armenian-English-French speakers in Quebec). This pattern is similar to North American English, though closure voicing may be somewhat more common in North American Western Armenian than English (compare to e.g., Lisker & Abramson Reference Lisker and Abramson1964: 395; Schertz Reference Schertz2013: 254; Davidson Reference Davidson2016).

Among speakers of Western Armenian in Lebanon, the plosive voicing contrast is between voiceless unaspirated and voiced plosives (Kelly & Keshishian Reference Kelly and Keshishian2019; Tahtadjian Reference Tahtadjian2021). This pattern corresponds to what has been described for Lebanese Arabic stops (Bellem Reference Bellem2014; Al-Tamimi & Khattab Reference Al-Tamimi and Khattab2018). As Lebanese Arabic was the most dominant non-Armenian language for the speakers in Kelly & Keshishian Reference Kelly and Keshishian2019 and Tahtadjian Reference Tahtadjian2021, it is possible that the phonetic contrast used by these speakers is influenced by their multilingualism.

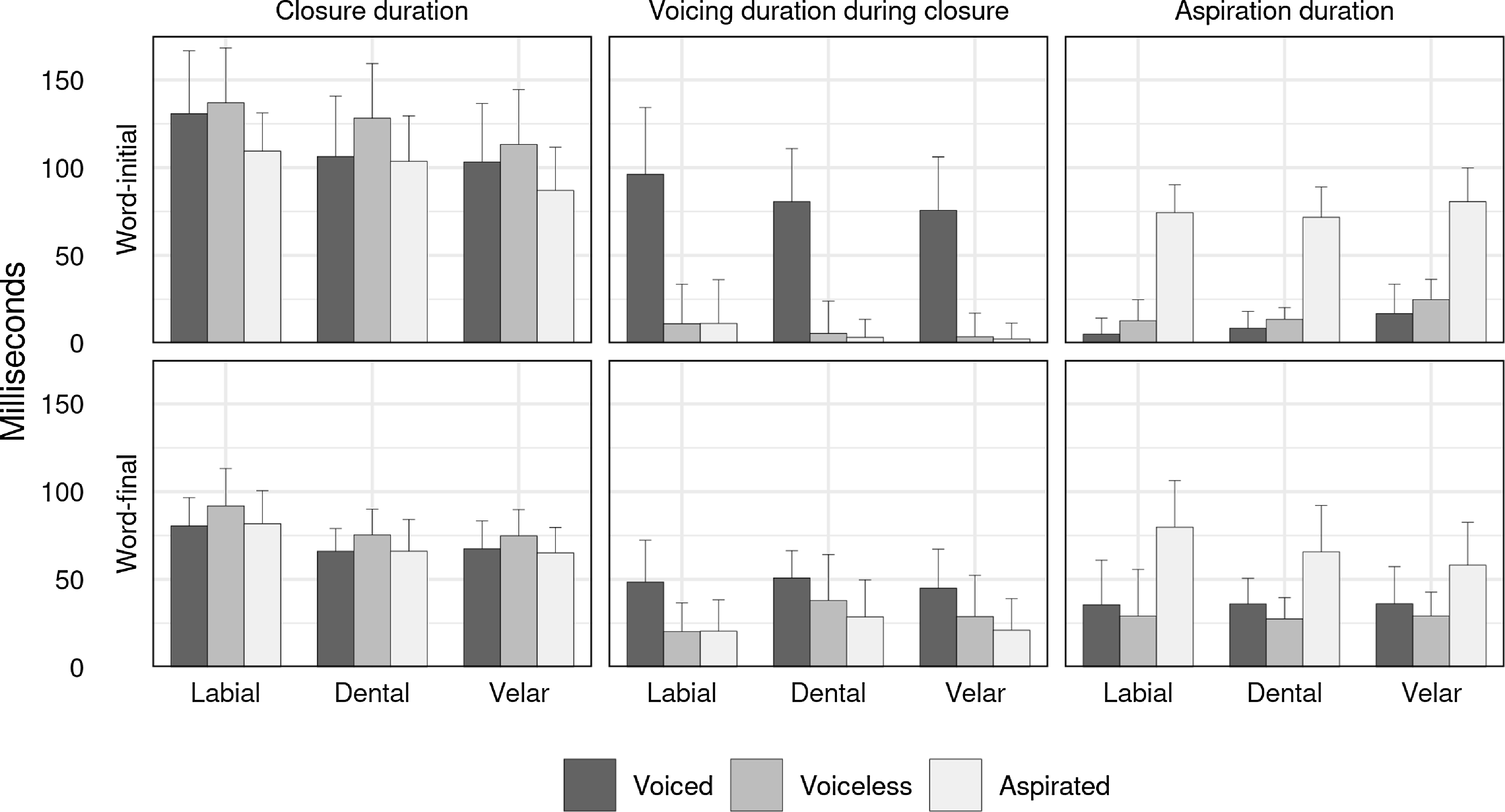

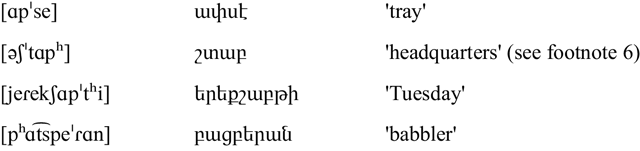

HD grew up in Beirut, Lebanon but has lived in the USA for the past eight years at the time of recording. His Armenian plosives currently follow the Western Armenian pattern reported for speakers in Anglophone Canada and the USA: one series is voiceless aspirated in most environments while the other can be either voiced or plain voiceless. Figure 4 shows the mean and standard deviation of closure duration, closure voicing duration, and aspiration duration for all six plosives in prevocalic word-initial (upper row) and postvocalic word-final (lower row) position. In this intervocalic context, HD consistently produces the voiced series with closure voicing, but in other environments he often produces these plosives as voiceless unaspirated, especially in utterance-initial position. For example, the initial sound of the accompanying recording of /bɑɾdkʰ/ [pɑɹ̝̊tkʰ] ![]() ‘debt’ is voiceless (see also Figure 9 in Syllable structure).

‘debt’ is voiceless (see also Figure 9 in Syllable structure).

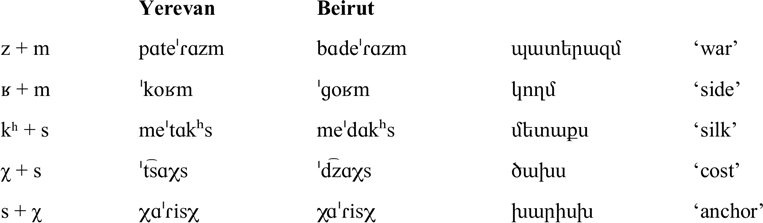

In HD’s Beirut Armenian variety, the voiceless plosives are not aspirated adjacent to voiceless sibilants (see Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 4–5), with word-medial examples shown below:

Figure 4 Mean (filled bars) and standard deviation (whiskers) for closure duration, closure voicing duration, and aspiration duration for the six Beirut Armenian plosives in word-initial and word-final position. Measurements are from recordings of HD reading aloud ten unique words containing each plosive twice in one or two carrier phrases, collected and annotated using the procedure in Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018. Each bar includes twenty tokens.

Word-final voiceless plosives are also unaspirated after voiceless sibilants, though utterance-final plosives are typically still aspirated. This is illustrated in utterance-final [ˈɑskʰ] ![]() ‘nation’ compared to utterance-medial [mɑɾˈjɑmə ˈɑsk əˈsɑv]

‘nation’ compared to utterance-medial [mɑɾˈjɑmə ˈɑsk əˈsɑv] ![]()

![]()

![]() ‘Mariam said “nation”.’

‘Mariam said “nation”.’

Aspiration is variable in sequences of two plosives, where the first plosive is often unaspirated even when it has a definite release, such as in /jeɾekʰʃɑpʰˈtʰi/ [jeɾekʃɑpˈtʰi] ![]() ‘Tuesday’ in the table above (see Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 4–5). However, when a sequence of two voiceless plosives has the same place of articulation, it is consistently pronounced as a long aspirated plosive and not rearticulated. This is illustrated in the form /pʰɑtʰtʰəˈvɑd͡z/ [pʰɑtʰːəˈvɑd͡z]

‘Tuesday’ in the table above (see Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 4–5). However, when a sequence of two voiceless plosives has the same place of articulation, it is consistently pronounced as a long aspirated plosive and not rearticulated. This is illustrated in the form /pʰɑtʰtʰəˈvɑd͡z/ [pʰɑtʰːəˈvɑd͡z] ![]() ‘wrapped’ as compared with the borrowing /pʰɑtʰɑˈtʰes/ [pʰɑtʰɑˈtʰes]

‘wrapped’ as compared with the borrowing /pʰɑtʰɑˈtʰes/ [pʰɑtʰɑˈtʰes] ![]() ‘potato’.

‘potato’.

With respect to place of articulation, we perceived the Western Armenian speakers in Lebanon recorded by Kelly & Keshishian (Reference Kelly and Keshishian2021) as using a dental articulation for the coronal plosives. Impressionistically, some of the speakers in the USA pronounced dental plosives while others pronounced alveolar ones.

Affricates and fricatives

Yerevan Armenian has a three-way voicing contrast for both dental and postalveolar affricates, including voiced, voiceless unaspirated and voiceless aspirated affricates. Word-initial examples are given in the Consonants table above; word-final examples appear below:

The word-final voiceless unaspirated affricates in Yerevan /ˈχɑnt͡s/ ![]() ‘bait’ and /ˈhɑt͡ʃ/

‘bait’ and /ˈhɑt͡ʃ/ ![]() ‘satisfied’ are audibly ejectives (see discussion in Yerevan Armenian plosives).

‘satisfied’ are audibly ejectives (see discussion in Yerevan Armenian plosives).

Figure 5 illustrates the closure, sibilant frication and aspiration intervals of the three dental affricates in a carrier phrase for Yerevan Armenian:

Figure 5 Yerevan Armenian dental affricates in a carrier phrase. Spectrograms and waveforms show a 300-millisecond excerpt beginning with a preceding /o/ vowel, then the target dental affricate indicated above the panel, and then the following /ɑ/ vowel.

Although all three affricates show some carry-over voicing from the preceding vowel, it is more robust for the voiced affricate in the right panel of Figure 5. The closure is longer in the unaspirated affricate than in the aspirated one (Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988). For the aspirated affricate (center panel), the aspiration interval begins at the 0.2-second mark. There is not always such a clear boundary between the sibilant frication and the aspiration in the aspirated affricates. However, the interval of combined frication and aspiration in the aspirated affricates is reliably longer than the frication in the unaspirated affricates (Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971; see Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 139 for perceptual evidence). Khachatryan & Airapetyan (Reference Khachatryan and Airapetyan1987) report substantially more overlap in the distributions of voicing lag time for the voiceless aspirated and unaspirated affricates than we observed, but they also show that the voiceless aspirated and unaspirated affricates can nevertheless be distinguished by a linear combination of voicing lag time and the intensity of noise above 2 kHz after the closure.

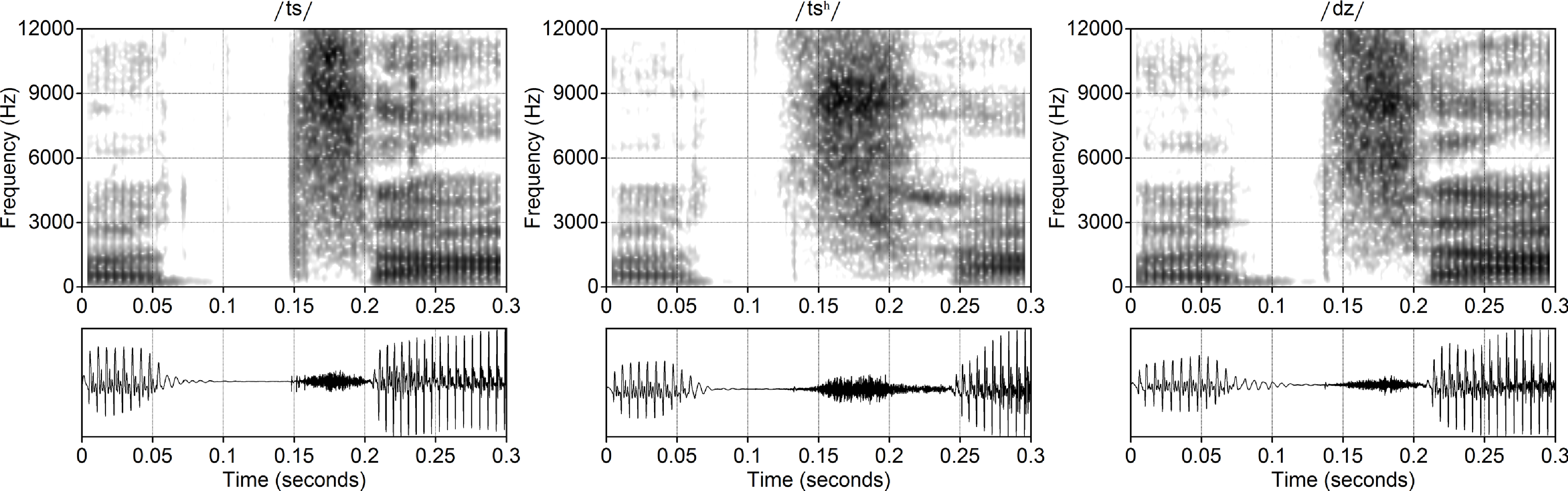

Beirut Armenian has a two-way voicing contrast for both affricate places. The broader Western affricate contrast is commonly reported as voiceless aspirated and voiced, matching the Western plosive contrast (Vaux Reference Vaux1998, in contrast with Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948). Because HD’s voiceless affricate pronunciations are unaspirated (shown in Figure 6), which is different than his plosive pronunciations, we categorize the voiceless affricates in his Western variety as /t͡s, t͡ʃ/. Kelly & Keshishian (Reference Kelly and Keshishian2019) also found that the voiceless affricate series is unaspirated for Lebanese Western speakers more broadly.

Figure 6 Beirut Armenian affricates in words produced in isolation.

The dental series /d͡z, t͡s, t͡sʰ/ (/d͡z, t͡s/ for Beirut Armenian) may be lamino-alveolar apico-dental, with the tongue tip incidentally contacting the upper teeth. Based on palatography and X-ray images, Xačatryan (Reference Xačatryan1988: 170) and Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan (Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971: 296) describe these affricates as apical and post-dental, having gingival contact which differs from the greater dental contact in the plosives. Other descriptions have labeled these affricates as alveolar (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009) and dental (Allen Reference Allen1950; Johnson Reference Johnson1954). Our speakers express disagreement and uncertainty as to whether the tongue usually makes contact with the back of the upper teeth. The X-ray tracings in Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988 do show dental contact during the affricate closure (Figures 29–30). In recordings of connected speech, we perceive these sounds as having a dental closure after vowels when the frication release is removed from the audio.

The sibilants /s, z/ are described as ‘dental’ (Allen Reference Allen1950; Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971), ‘post-dental’ (Johnson Reference Johnson1954: 26; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 85, 110), or ‘alveolar’ (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009). SK, TT, and a Yerevan speaker report that the tongue tip is held behind the upper teeth, while HD and three Yerevan speakers report that the tongue tip touches the back of the lower teeth during these sounds. The sagittal X-ray tracings for /s, z/ in Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988 show a lamino-alveolar place of articulation with an inconsistent tongue tip position (Figures 23–24, as described on p. 178).

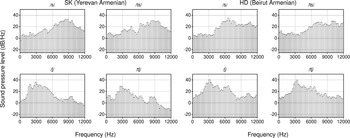

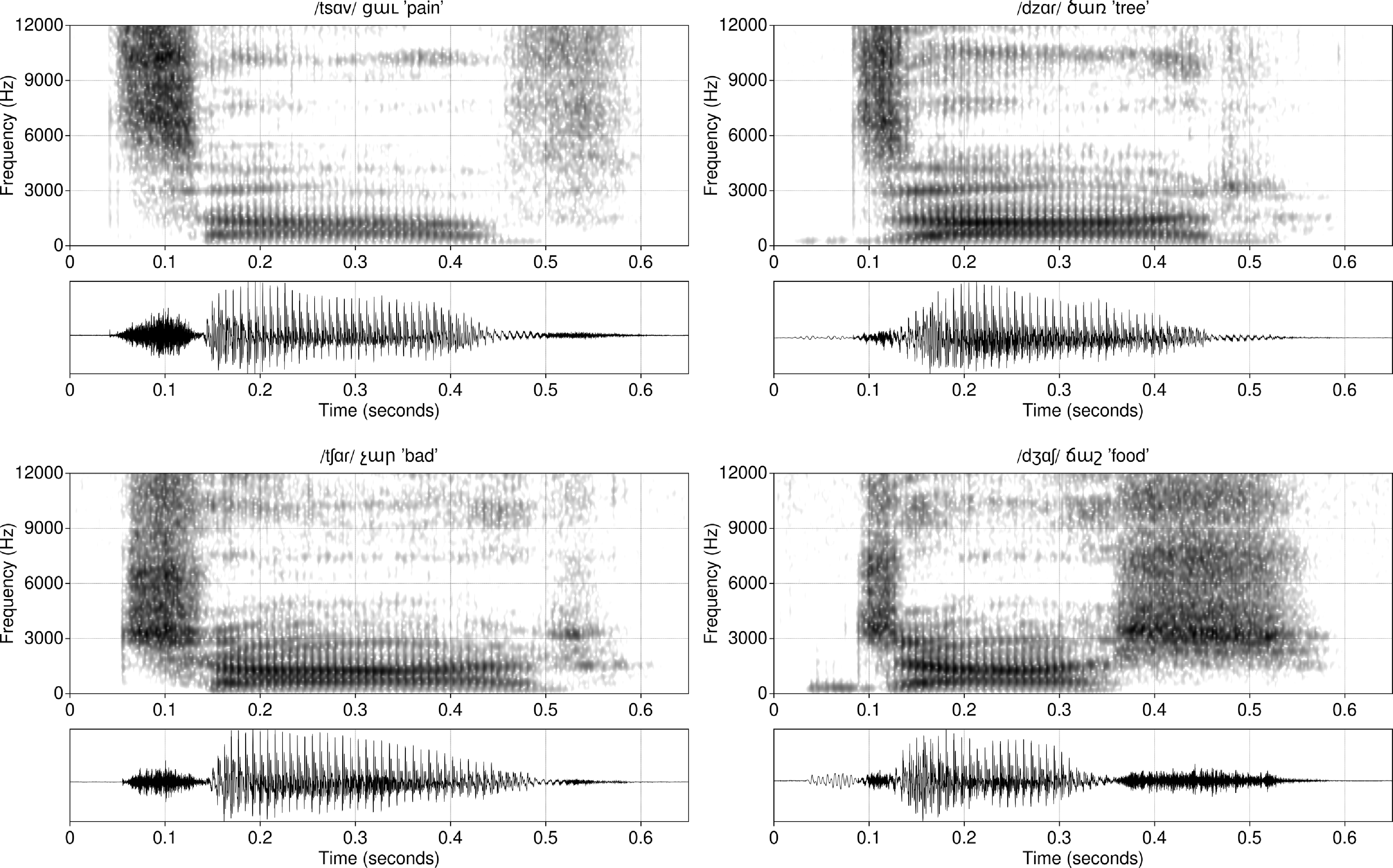

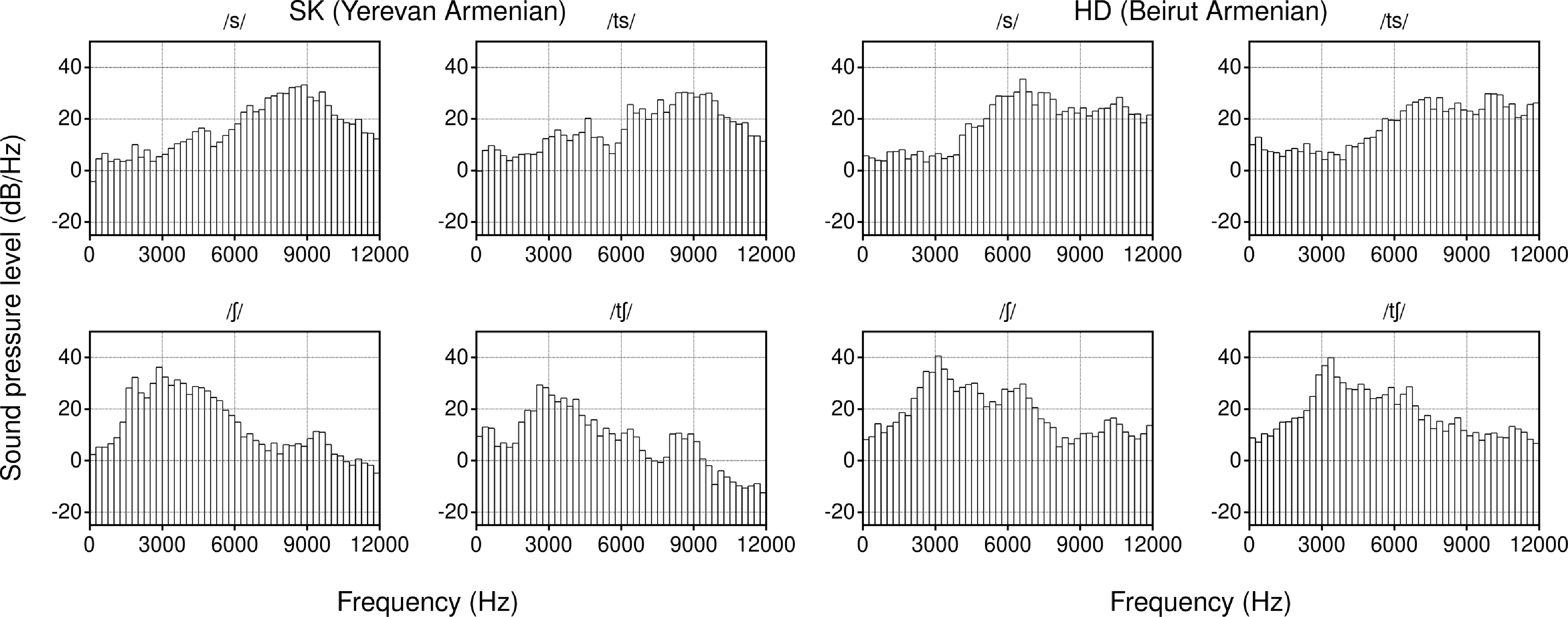

Figure 7 shows the log power spectral density for the voiceless fricatives and affricates for SK and HD. For /s/ and /t͡s/, SK has a high spectral peak at roughly 9 kHz (as in Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971: 302; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 178) which may index an apico-dental articulation (cf. lower peak for alveolar /s/ in Jongman, Wayland, & Wong Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000; Maniwa, Jongman, & Wade Reference Maniwa, Jongman and Wade2009). HD has a lower spectral peak for /s/ around 7 kHz, consistent with a lamino-alveolar but not apico-dental articulation. For /ʃ/ and /t͡ʃ/, both speakers have a relatively low peak around 3 kHz (as in Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971: 304), and SK has a second mode at 9 kHz.

Figure 7 Log power spectral density for /s/, /ʃ/, /t͡s/, and /t͡ʃ/ for speakers SK (Yerevan Armenian) and HD (Beirut Armenian). Each panel shows a long-term average spectrum which is calculated over the center 30 milliseconds of sibilant energy (for fricatives), or over the 30 milliseconds immediately following the closure release (for affricates), omitting the release transient if one is present. Measurements are taken from the illustrative recordings accompanying the consonant table above.

The postalveolar sibilants /ʃ, ʒ/ are also called ‘pre-palatal’ (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 85), ‘palato-alveolar’ (Allen Reference Allen1950; Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971), or ‘mid-palatal’ (Johnson Reference Johnson1954). The X-rays in Xačatryan (Reference Xačatryan1988: Figures 25–26, 32–34) show a laminal postalveolar constriction for /ʃ, ʒ/ and during the frication release of /d͡ʒ, t͡ʃ, t͡ʃʰ/. A laminal postalveolar constriction is consistent with the low spectral peak in the lower panels of Figure 7. Allen (Reference Allen1950: 188) and Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan (Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971: 303) report that these are accompanied by lip-rounding. SK employs lip-rounding for /ʃ, ʒ/ while HD does not.

Voiceless labiodental /f/ (grapheme ![]() ) is rare and occurs primarily in borrowed words, though many borrowings date to the twelfth century or earlier. Dum-Tragut (Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 20) transcribes the voiced labiodental /v/ as the approximant [ʋ] when it occurs in word-initial position before /o/, as well as in medial and final position after /e/. Our speakers have the voiced fricative [v] in all positions. Xačatryan (Reference Xačatryan1988: 176) measures a wider labiodental constriction for /ɑvɑ/ compared to /ɑfɑ/ from X-ray tracings (ibid., Figures 21–22). This may be a categorical manner difference ([f] vs. [ʋ]), or the wider /v/ constriction may simply facilitate voicing, which is unnecessary for voiceless /f/.

) is rare and occurs primarily in borrowed words, though many borrowings date to the twelfth century or earlier. Dum-Tragut (Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 20) transcribes the voiced labiodental /v/ as the approximant [ʋ] when it occurs in word-initial position before /o/, as well as in medial and final position after /e/. Our speakers have the voiced fricative [v] in all positions. Xačatryan (Reference Xačatryan1988: 176) measures a wider labiodental constriction for /ɑvɑ/ compared to /ɑfɑ/ from X-ray tracings (ibid., Figures 21–22). This may be a categorical manner difference ([f] vs. [ʋ]), or the wider /v/ constriction may simply facilitate voicing, which is unnecessary for voiceless /f/.

The back continuants (/χ, ʁ/ in the table above) vary between the uvular and velar places. Previous work describes these as ‘velar’ (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948; Johnson Reference Johnson1954), ‘post-velar’ (Johnson Reference Johnson1954; Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971), and ‘uvular’ (Vaux Reference Vaux1998; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009), while Allen (Reference Allen1950) along with HD and PG report that the voiceless fricative is roughly velar while its voiced counterpart is roughly uvular. Xačatryan (Reference Xačatryan1988: 85, 181) uses the term ![]() ‘of the soft palate’ and provides X-ray tracings (Figures 27–28) that show a uvular constriction for both /χ, ʁ/ between two /ɑ/ vowels.

‘of the soft palate’ and provides X-ray tracings (Figures 27–28) that show a uvular constriction for both /χ, ʁ/ between two /ɑ/ vowels.

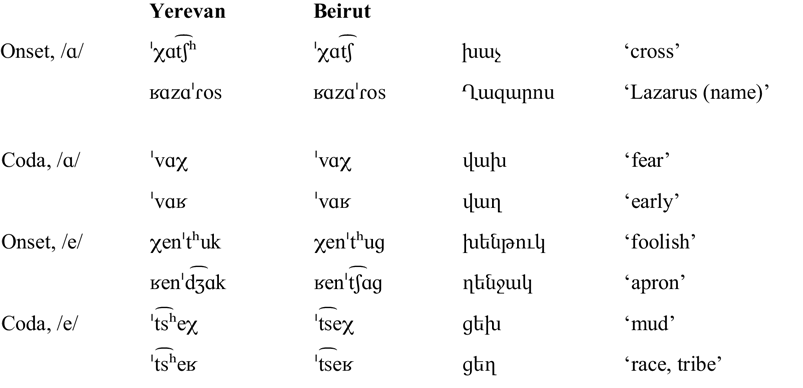

The examples listed below illustrate the two sounds adjacent to the near-back vowel /ɑ/ and the front vowel /e/ in syllable onsets and codas:

The voiced back continuant varies between the fricative [ʁ] and the approximant [ʁ̞]. The preceding Beirut Armenian recording of /ʁɑzɑˈɾos/ ![]() ‘Lazarus (name)’, as well as the accompanying recording of Yerevan Armenian /səˈʁel/

‘Lazarus (name)’, as well as the accompanying recording of Yerevan Armenian /səˈʁel/ ![]() ‘to increase a price’ contain approximant realizations.

‘to increase a price’ contain approximant realizations.

Obstruent cluster devoicing

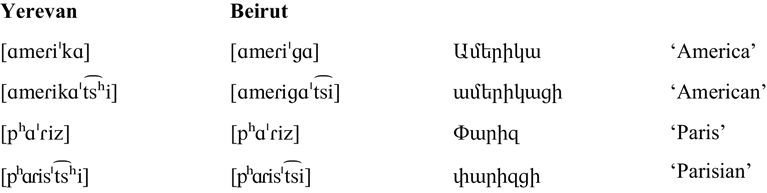

All obstruents participate in a regressive devoicing pattern when a cluster of two obstruents is formed by compounding, suffixation, or other morphological alternations. In both dialects, the first obstruent is devoiced if the second obstruent is voiceless (see Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 104; Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 17–18). For example, the suffix /-t͡sʰi/ (Yerevan), /-t͡si/ (Beirut) -![]() is used to form demonyms (rows 1–2 of the table below). When this voiceless-initial suffix follows a word such as /pʰɑˈɾiz/

is used to form demonyms (rows 1–2 of the table below). When this voiceless-initial suffix follows a word such as /pʰɑˈɾiz/ ![]() ‘Paris’ that has a final voiced obstruent, the stem-final obstruent is voiceless (rows 3–4). The Yerevan Armenian recordings in this subsection were contributed by VP.

‘Paris’ that has a final voiced obstruent, the stem-final obstruent is voiceless (rows 3–4). The Yerevan Armenian recordings in this subsection were contributed by VP.

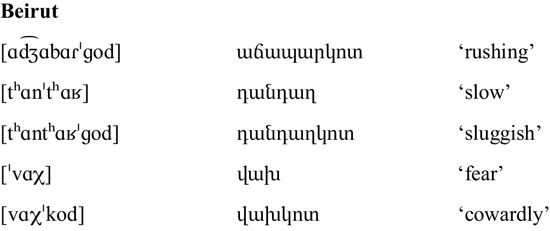

In addition to this regressive devoicing pattern, Beirut Armenian also has a progressive devoicing pattern: if the first obstruent is voiceless, then the second obstruent is devoiced. For example, the Beirut Armenian suffix /-ɡod/ -![]() is used to form adjectives (following a stem-final sonorant in row 1, and a voiced obstruent in rows 2–3 of the table below). When it combines with a word that has a final voiceless obstruent, such as /ˈvɑχ/

is used to form adjectives (following a stem-final sonorant in row 1, and a voiced obstruent in rows 2–3 of the table below). When it combines with a word that has a final voiceless obstruent, such as /ˈvɑχ/ ![]() ‘fear’, the suffix-initial obstruent is voiceless (rows 4–5).

‘fear’, the suffix-initial obstruent is voiceless (rows 4–5).

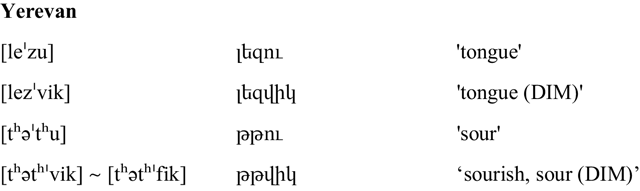

In Yerevan Armenian, we observed optional progressive devoicing of /v/ following a voiceless obstruent. For example, when the diminutive suffix /-ik/ -![]() combines with a word ending in /u/, the final syllable is pronounced /-vik/ (rows 1–2 of the table below; see Syllable structure on vowel hiatus). However, the syllable onset varies between [v] and [f] when it follows a voiceless obstruent in the stem word (rows 3–4 below).

combines with a word ending in /u/, the final syllable is pronounced /-vik/ (rows 1–2 of the table below; see Syllable structure on vowel hiatus). However, the syllable onset varies between [v] and [f] when it follows a voiceless obstruent in the stem word (rows 3–4 below).

VP indicates that both the voiced [v] and devoiced [f] pronunciations are natural in ![]() , as well as in the /v/-initial passive suffix when it follows a voiceless obstruent (not illustrated here). However, other than obstruent sequences involving /v/, the morphophonological context where progressive devoicing could potentially occur is very rare in Yerevan Armenian, and it is thus not clear whether progressive devoicing is generally optional, obligatory, or idiosyncratic in this dialect.

, as well as in the /v/-initial passive suffix when it follows a voiceless obstruent (not illustrated here). However, other than obstruent sequences involving /v/, the morphophonological context where progressive devoicing could potentially occur is very rare in Yerevan Armenian, and it is thus not clear whether progressive devoicing is generally optional, obligatory, or idiosyncratic in this dialect.

Sonorants

The nasal /n/ has been categorized as ‘dental’ (Allen Reference Allen1950; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988), ‘post-dental’ (Khachatryan & Ayrapetyan Reference Khachatryan and Ayrapetyan1971), ‘alveodental’ (Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009), ‘alveolar’ (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948), and ‘nondistinctly … postdental to alveolar’ (Johnson Reference Johnson1954). Our speaker consultants disagree on whether /n/ involves dental contact. The nasal /n/ assimilates to the place of a following obstruent, as in Yerevan [ˈsuŋk], Beirut [ˈsuŋɡ] ![]() ‘mushroom’ (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 8; Allen Reference Allen1950: 196–197; Johnson Reference Johnson1954: 26–27; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 27; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 106).

‘mushroom’ (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 8; Allen Reference Allen1950: 196–197; Johnson Reference Johnson1954: 26–27; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 27; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 106).

The lateral /l/ is described as alveolar by Fairbanks (Reference Fairbanks1948: 9), Johnson (Reference Johnson1954: 27), and Dum-Tragut (Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 21); and as dental by Allen (Reference Allen1950), and Xačatryan (Reference Xačatryan1988: 85). As with /n/, our speaker consultants disagree on whether /l/ involves dental contact in their individual pronunciation.

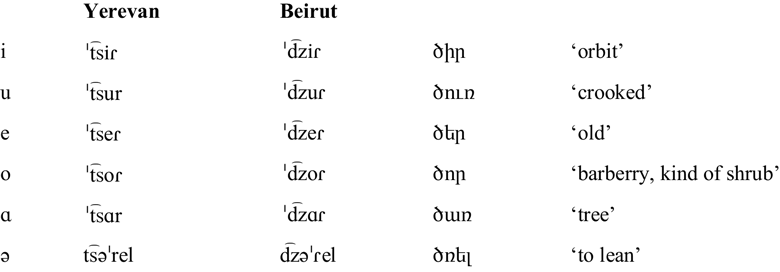

The rhotics /r, ɾ/ are contrastive in Yerevan Armenian, with minimal pairs such as the following:

The tap is often spirantized in syllable codas (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 8; Allen Reference Allen1950: 195; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 186; Toparlak Reference Toparlak2017: Appendix 2). We observed this especially in citation forms and in emphatic speech.Footnote 8 For example, SK’s recordings contrast /ˈseɾ/ and /ˈser/ primarily via louder frication noise for the tap /ɾ/ with a low spectral peak around 4 kHz (perhaps non-sibilant postalveolar fricative [ɹ̝̊])Footnote 9. However, word-final /ɾ/ is often unambiguously tapped or approximated in connected speech, such as in the accompanying recordings of the North Wind and Sun by HD and SK (see Transcription of recorded passage). Tap and approximant variants are both common in intervocalic position. The recordings of /kʰɑˈɾi/ ![]() ‘rock (DAT.GEN)’ and /χɑˈɾisχ/

‘rock (DAT.GEN)’ and /χɑˈɾisχ/ ![]() ‘anchor’ contributed by SK illustrate approximant variants of /ɾ/.

‘anchor’ contributed by SK illustrate approximant variants of /ɾ/.

The recording of /ˈser/ is not trilled, but has a falling third formant that is excited by aspiration without voicing, and only weak or absent oral frication noise. Most of the coda trills in the accompanying recordings contributed by SK are voiceless and/or spirantized. For example, the recording of /ˈ t͡sɑr/ ![]() ‘tree’ in the section Vowels (below) includes a voiceless trill, while the recording of the same word in the Consonants table is more similar to the variant in /ˈser/. A voiced trill coda is illustrated in the recording of /ˈkor/

‘tree’ in the section Vowels (below) includes a voiceless trill, while the recording of the same word in the Consonants table is more similar to the variant in /ˈser/. A voiced trill coda is illustrated in the recording of /ˈkor/ ![]() ‘coerced labor (archaic)’, from the speaker who contributed /ˈkoʁ/

‘coerced labor (archaic)’, from the speaker who contributed /ˈkoʁ/ ![]() ‘rib’ in the subsection Yerevan Armenian plosives.

‘rib’ in the subsection Yerevan Armenian plosives.

Although the two rhotics are contrastive in Yerevan Armenian, the tap is sometimes trilled before coronals (Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 108; Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 19; also noted by speaker VP), and word-initial trills are often reduced to the tap.Footnote 10

In Western Armenian, both sounds are merged to the tap /ɾ/ in all environments (Vaux Reference Vaux1998), though they are prescriptively taught as contrastive in Canadian Armenian language schools (Talia Tahtadjian, p.c.) and some Western Armenian dictionaries (Sak’apetoyean Reference Sak’apetoyean2011; also in Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948). For the Western Armenian community in Canada, Tahtadjian (Reference Tahtadjian2020) reports that the Western Armenian tap and trill are acoustically distinguishable: the Western trill sometimes has multiple articulator contacts (occurring in about 30

![]() $\%$

of onset trills produced by older speakers, and <15

$\%$

of onset trills produced by older speakers, and <15

![]() $\%$

of other trills), and the trill is about 2 ms longer in onset position and 4 ms longer in coda position. These differences are probably too small or too variable to reliably index a category difference. In the accompanying recording of Beirut Armenian [rɑzmɑˈɡɑn]

$\%$

of other trills), and the trill is about 2 ms longer in onset position and 4 ms longer in coda position. These differences are probably too small or too variable to reliably index a category difference. In the accompanying recording of Beirut Armenian [rɑzmɑˈɡɑn] ![]() ‘military’ contributed by HD, the onset consonant has multiple contacts, but HD indicates that the tap and trill were perceptually indistinguishable for his peer group in a Lebanese Armenian school.

‘military’ contributed by HD, the onset consonant has multiple contacts, but HD indicates that the tap and trill were perceptually indistinguishable for his peer group in a Lebanese Armenian school.

In both dialects, the two rhotics are rare word-initially. While there are some native rhotic-initial words such as Yerevan /rɑmkɑˈkɑn/ ![]() ‘democratic’, most such words are names like Yerevan /rɑfɑˈjel/

‘democratic’, most such words are names like Yerevan /rɑfɑˈjel/ ![]() ‘Raphael (name)’ and borrowings such as Yerevan /rɑˈbi/

‘Raphael (name)’ and borrowings such as Yerevan /rɑˈbi/ ![]() ‘rabbi’. For these words, the Beirut forms use a tap instead of the trill: /ɾɑmɡɑˈɡɑn/, /ɾɑfɑˈjel/ (

‘rabbi’. For these words, the Beirut forms use a tap instead of the trill: /ɾɑmɡɑˈɡɑn/, /ɾɑfɑˈjel/ (![]() ), /ɾɑˈpʰi/. Both rhotics are more frequent medially and finally, and occur in Yerevan minimal pairs such as the above.

), /ɾɑˈpʰi/. Both rhotics are more frequent medially and finally, and occur in Yerevan minimal pairs such as the above.

Most sources treat /j/ as phonemic (in contrast with Vaux Reference Vaux1998), though it has a limited distribution. In word-initial position, the palatal approximant /j/ primarily occurs before /e/, such as in /ˈjeɾpʰ/ ![]() ‘when’ (see Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 13 for a phonological analysis and Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 14–17 for a lexical catalog; see also Vowels). All attested word-initial /jɑ/ are borrowings, such as /ˈjɑvɾəm/

‘when’ (see Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 13 for a phonological analysis and Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 14–17 for a lexical catalog; see also Vowels). All attested word-initial /jɑ/ are borrowings, such as /ˈjɑvɾəm/ ![]() ,

, ![]() ‘my dear’ from Turkish. It is also found word-initially before the back vowels /u/ and /o/ in a handful of native words, such as /ˈjuʁ/

‘my dear’ from Turkish. It is also found word-initially before the back vowels /u/ and /o/ in a handful of native words, such as /ˈjuʁ/ ![]() ,

, ![]() ‘oil’ and /ˈjotʰə/

‘oil’ and /ˈjotʰə/ ![]() ,

, ![]() ‘seven’. In some words, the Yerevan Armenian sequence /ju/ is pronounced [ʏ] in Beirut Armenian, though there is substantial variation (Khanjian Reference Khanjian2011). For example, Yerevan /ˈɡjuʁ/

‘seven’. In some words, the Yerevan Armenian sequence /ju/ is pronounced [ʏ] in Beirut Armenian, though there is substantial variation (Khanjian Reference Khanjian2011). For example, Yerevan /ˈɡjuʁ/ ![]() ‘village’ corresponds to Beirut [ˈkʰʏʁ] ∼ [ˈkʰjʏʁ] ∼ [ˈkʰjuʁ]

‘village’ corresponds to Beirut [ˈkʰʏʁ] ∼ [ˈkʰjʏʁ] ∼ [ˈkʰjuʁ] ![]() .

.

In native words, coda /j/ does not appear after /ə/, or word-finally after /i/ or /u/. It occurs in native complex codas only after /ɑ/ and /u/, such as in /ˈhɑjɾ/ ![]() ‘father’. Word-medially, /Cj/ sequences may have ambiguous onset syllabification (Margaryan Reference Margaryan1997: 55), such as in Yerevan /sen.jɑk, se.njɑk/

‘father’. Word-medially, /Cj/ sequences may have ambiguous onset syllabification (Margaryan Reference Margaryan1997: 55), such as in Yerevan /sen.jɑk, se.njɑk/ ![]() and Beirut /sen.jɑɡ, se.njɑɡ/

and Beirut /sen.jɑɡ, se.njɑɡ/ ![]() ‘room’ (see also Syllable structure).

‘room’ (see also Syllable structure).

Vowels

Word-initial vowels

Word-medial vowels

Word-final vowels

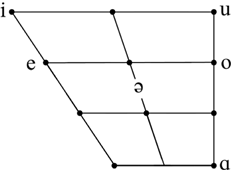

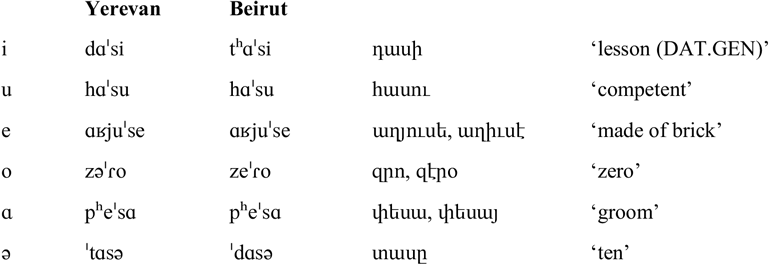

For this illustration, we summarize the acoustic vowel measurements originally collected by Toparlak (Reference Toparlak2019). Other vowel measurements are provided by Xačatryan (Reference Xačatryan1988: 152–164), Godson (Reference Godson2003, Reference Godson2004), Gordon et al. (Reference Gordon, Edita Ghushchyan and Parker2012) and Seyfarth & Garellek (Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018).

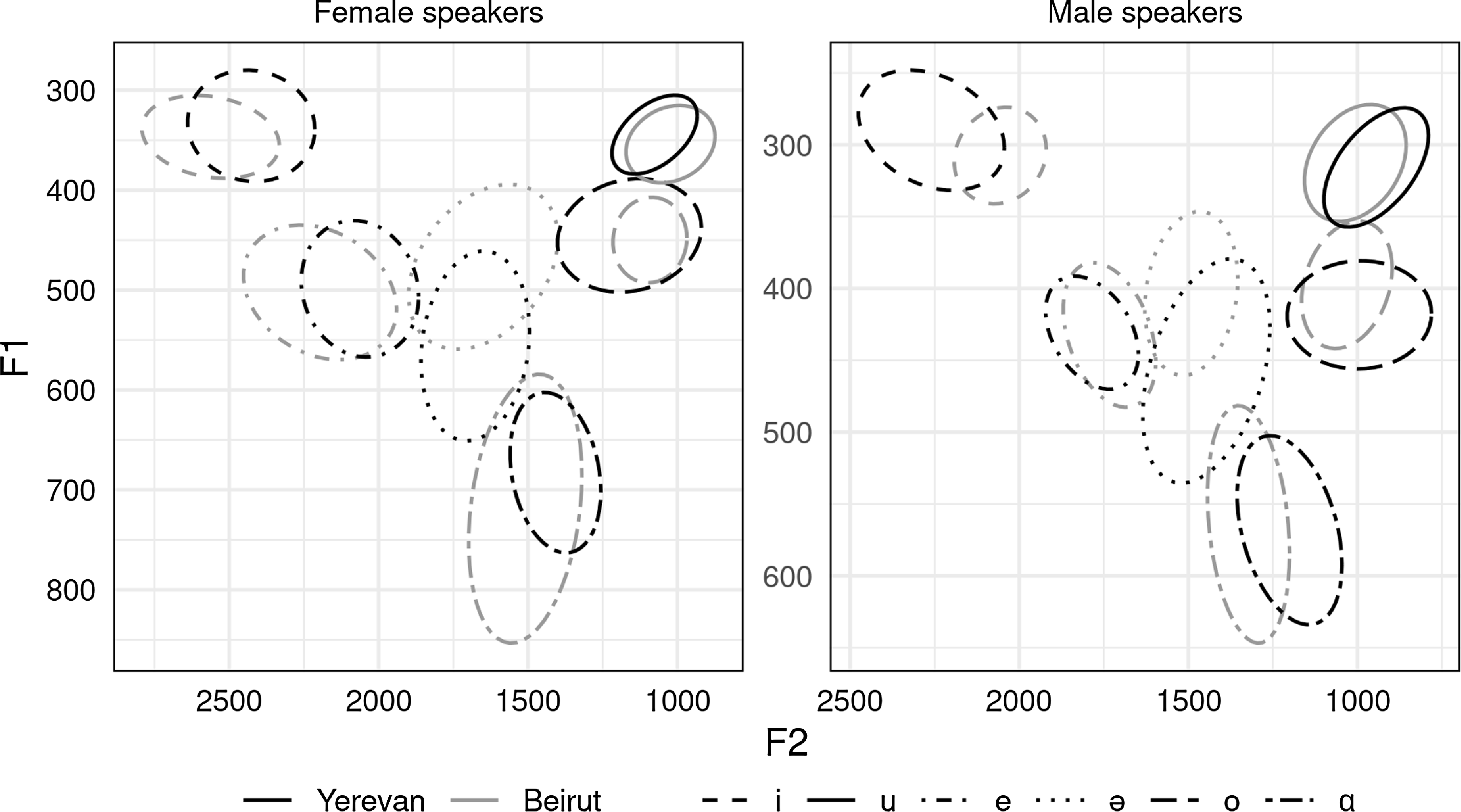

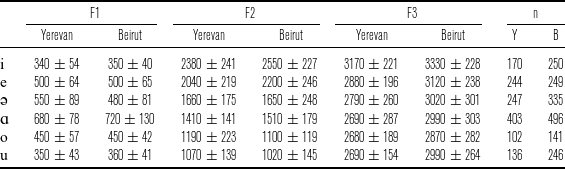

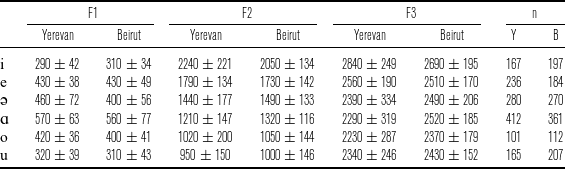

Toparlak (Reference Toparlak2019) measured vowels that were elicited from six speakers each of Yerevan Armenian and Beirut Armenian, including three female and three male speakers per variety. All speakers were aged 21–40 and living in Paris, and Armenian was their dominant language. The speakers each read aloud thirty-two dialect-appropriate sentences containing target words with initial, medial, and final vowels, and then repeated the target words in isolation. The sentences and isolated words were repeated multiple times by each speaker for a total of approximately 5,800 measured vowel tokens. Figure 8 shows a graphical summary of formant measurements for the six Armenian vowels, with values given in Table 1 (female speakers) and Table 2 (male speakers).

Figure 8 Average first and second formant frequencies for the six vowels in Yerevan and Beirut Armenian, based on measurements from three female and three male speakers per language variety in Toparlak Reference Toparlak2019. Ellipses cover the central 50

![]() $\%$

of the observations for a vowel type.

$\%$

of the observations for a vowel type.

Table 1 Formant frequency mean and standard deviation for the six vowels in Yerevan and Beirut Armenian, based on measurements from Toparlak Reference Toparlak2019 with three female speakers per language variety. Mean values are rounded to the nearest 10 Hz.

Table 2 Formant frequency mean and standard deviation for the six vowels in Yerevan and Beirut Armenian, based on measurements from Toparlak Reference Toparlak2019 with three male speakers per language variety. Mean values are rounded to the nearest 10 Hz.

The mid-front vowel /e/ varies acoustically between /e/ and /ɛ/ and could be narrowly transcribed as [e̞]. As an example, the recording of /ɑʁjuˈse/ ![]() ‘made of brick’ contributed by SK has a final vowel closer to open-mid [ɛ] while the corresponding vowel in the recording contributed by HD is closer to [e]. On the other hand, the vowel in the recording of /ˈjet, ˈjed/

‘made of brick’ contributed by SK has a final vowel closer to open-mid [ɛ] while the corresponding vowel in the recording contributed by HD is closer to [e]. On the other hand, the vowel in the recording of /ˈjet, ˈjed/ ![]() ‘backward’ in Consonants contributed by HD is lower than in the corresponding recording by SK. Godson (Reference Godson2004) shows that this vowel is lower for Western Armenian speakers in southern California with increasing English dominance, closer to the California English open-mid front vowel.

‘backward’ in Consonants contributed by HD is lower than in the corresponding recording by SK. Godson (Reference Godson2004) shows that this vowel is lower for Western Armenian speakers in southern California with increasing English dominance, closer to the California English open-mid front vowel.

The mid-back vowel is categorized as /ɔ/ by some grammars (e.g., Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 13), but it has a low F1 distribution that partially overlaps with the /u/ category (Toparlak Reference Toparlak2019), which makes the broad symbol /o/ more appropriate.

We transcribe the low vowel with /ɑ/, as in Vaux (Reference Vaux1998), Godson (Reference Godson2004), and Dum-Tragut (Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 13). It could be narrowly transcribed as central or near-back [ɑ̈] (Allen Reference Allen1950). Some descriptions transcribe this vowel as central or near-front /a/ (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 2; Johnson Reference Johnson1954: 18), and Xačatryan (Reference Xačatryan1988: 55) reports that this vowel can vary widely from front to back. In Yerevan Armenian, the back vowels /ɑ, o, u/ are further fronted by about 200 Hz after aspirated and (breathy-)voiced plosives (Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018).

Although all six vowels occur in all three environments, word-initial mid vowels are uncommon (see below on Schwa). Word-initial /e/ occurs in forms of the copula ![]() as found throughout the Transcription of recorded passage as well in as a few other native words such as /ˈeʃ/

as found throughout the Transcription of recorded passage as well in as a few other native words such as /ˈeʃ/ ![]() ‘donkey’, but is mostly used in loanwords. In word-final position, most roots with final /o/ are loanwords such as Yerevan /k(ʰ)iˈlo/

‘donkey’, but is mostly used in loanwords. In word-final position, most roots with final /o/ are loanwords such as Yerevan /k(ʰ)iˈlo/ ![]() or Beirut /kʰiˈlo/

or Beirut /kʰiˈlo/ ![]() ,

, ![]() ‘kilogram’. However, the native Armenian hypocoristic suffix /-o/ is used widely, as in /ˈmɑɾo/ or /mɑˈɾo/

‘kilogram’. However, the native Armenian hypocoristic suffix /-o/ is used widely, as in /ˈmɑɾo/ or /mɑˈɾo/ ![]() ,

, ![]() from /mɑɾˈjɑm/

from /mɑɾˈjɑm/ ![]() ‘Mariam (name)’.

‘Mariam (name)’.

Schwa

Khachaturian (Reference Khachaturian1985) and Dum-Tragut (Reference Dum-Tragut2009) treat the Armenian schwa as a phoneme, but Vaux (Reference Vaux1998) and Allen (Reference Allen1950) analyze the schwa as purely epenthetic, and Hovhannisyan (Reference Hovhannisyan2014: 89) argues that it is excrescent in some environments such as before final rhotics. Acoustically, schwa is mid-central for Yerevan Armenian, but might be transcribed as [ə̝] for Beirut Armenian (cf. lower F1 in Figure 2 and Tables 1–2; Toparlak Reference Toparlak2019; see also Gordon et al. Reference Gordon, Edita Ghushchyan and Parker2012 and Seyfarth & Garellek Reference Seyfarth and Garellek2018). The two different acoustic distributions suggest that it has an acoustic or articulatory target in at least one of the dialects, in at least some environments.

Schwa is used in careful speech of both Eastern and Western Armenian (Ġaragyowlyan Reference Ġaragyowlyan1979: 37; Margaryan Reference Margaryan1997: 51), but schwa elision is common in colloquial and connected speech (Allen Reference Allen1950). Further, the schwa is optionally elided even in citation form for some lexemes, especially adjacent to rhotics, fricatives, and post-aspiration (Ġaragyowlyan Reference Ġaragyowlyan1974: 127, 145–147; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 73; Hovakimyan Reference Hovakimyan2016: 18ff). For example, the words /kʰ(ə)ˈsɑn/ ![]() ‘twenty’ and /kʰ(ə)ˈʃel/

‘twenty’ and /kʰ(ə)ˈʃel/ ![]() ‘to drive’ are acceptable without schwa in citation form (for similar patterns in English and French, see Davidson Reference Davidson2006; Racine & Grosjean Reference Racine and Grosjean2005; Bürki, Ernestus, & Frauenfelder Reference Bürki, Ernestus and Frauenfelder2010).

‘to drive’ are acceptable without schwa in citation form (for similar patterns in English and French, see Davidson Reference Davidson2006; Racine & Grosjean Reference Racine and Grosjean2005; Bürki, Ernestus, & Frauenfelder Reference Bürki, Ernestus and Frauenfelder2010).

In monosyllabic non-onomatopoeic free-standing words, schwas are unattested except for the name of the alphabet letter /ˈətʰ/ ![]() . Schwas are also used in initialisms, in which consonant letters are pronounced as the corresponding consonant sound plus schwa, as in /i.iˈhə/

. Schwas are also used in initialisms, in which consonant letters are pronounced as the corresponding consonant sound plus schwa, as in /i.iˈhə/ ![]() ‘I.I.H., the Islamic Republic of Iran’. Polysyllabic words generally have at least one other non-schwa vowel with word-level stress (see Word-level prosody below). A few polysyllabic words have only schwa vowels, but many of these are onomatopoeic or nativized loanwords, such as /fəsˈtəχ/

‘I.I.H., the Islamic Republic of Iran’. Polysyllabic words generally have at least one other non-schwa vowel with word-level stress (see Word-level prosody below). A few polysyllabic words have only schwa vowels, but many of these are onomatopoeic or nativized loanwords, such as /fəsˈtəχ/ ![]() ‘pistachio’ (cf. Turkish /fɯstɯk/ fıstık).

‘pistachio’ (cf. Turkish /fɯstɯk/ fıstık).

Schwa often appears in morphophonological alternations involving stress changes or consonant clusters (Vaux Reference Vaux1998, Reference Vaux2003). For example, Yerevan /t͡səˈrel/, Beirut /d͡zəˈɾel/ ![]() ‘to lean’ is a verb form of the adjective /ˈ t͡sur/, /ˈd͡zuɾ/

‘to lean’ is a verb form of the adjective /ˈ t͡sur/, /ˈd͡zuɾ/ ![]() ‘crooked’ in which the stressed high vowel alternates with an unstressed schwa. The first- and second-person possessor suffixes /-s/, /-t/ (Yerevan), /-tʰ/ (Beirut) appear directly after vowel-final stems, but are preceded by a schwa when they are used with consonant-final stems. The presence of schwa in these alternations is not predictable from the phonology alone (Dolatian Reference Dolatian2021): high vowels do not generally alternate with schwa when they are unstressed (see the Vowels table for examples), and /-s/ can occur in other word-final coda clusters such as in /ˈ t͡sɑχs/, /ˈd͡zɑχs/

‘crooked’ in which the stressed high vowel alternates with an unstressed schwa. The first- and second-person possessor suffixes /-s/, /-t/ (Yerevan), /-tʰ/ (Beirut) appear directly after vowel-final stems, but are preceded by a schwa when they are used with consonant-final stems. The presence of schwa in these alternations is not predictable from the phonology alone (Dolatian Reference Dolatian2021): high vowels do not generally alternate with schwa when they are unstressed (see the Vowels table for examples), and /-s/ can occur in other word-final coda clusters such as in /ˈ t͡sɑχs/, /ˈd͡zɑχs/ ![]() ‘cost’ without schwa (see Syllable structure). Moreover, some free-standing forms like Yerevan /vəˈkɑ/

‘cost’ without schwa (see Syllable structure). Moreover, some free-standing forms like Yerevan /vəˈkɑ/ ![]() and Beirut /vəˈɡɑ/

and Beirut /vəˈɡɑ/ ![]() ‘witness’ have no related forms without schwa (Vaux Reference Vaux1998), and our speakers indicate that it is impossible or unnatural to elide the schwa (*vkɑ, *vɡɑ) in isolation or in citation form.

‘witness’ have no related forms without schwa (Vaux Reference Vaux1998), and our speakers indicate that it is impossible or unnatural to elide the schwa (*vkɑ, *vɡɑ) in isolation or in citation form.

Prosody

Syllable structure

Armenian generally allows up to CjVCCkʰ syllables, with all elements optional except for V. There are some exceptional complex onsets other than /Cj/ which are never pronounced with an intervening schwa, primarily in non-nativized loanwords (Ġaragyowlyan Reference Ġaragyowlyan1974: 65).

When vowel hiatus would occur between a stem-final vowel and a suffix-initial vowel, various repair strategies are attested (Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 27ff; Dolatian Reference Dolatian2020: 35ff). Vowel repair strategies include [j]-insertion between vowels and /u/ devocalizing to [v]. Different words and different vowel sequences show different types of vowel hiatus repairs. In some cases, multiple vowel hiatus repair strategies are possible for the same word. For example, the instrumental case form of the vowel-final stem /leˈzu/ ![]() ‘tongue’ with the vowel-initial suffix /-ov/ -

‘tongue’ with the vowel-initial suffix /-ov/ -![]() is variably [lezuˈjov]

is variably [lezuˈjov] ![]() ([j]-insertion) or [lezˈvov]

([j]-insertion) or [lezˈvov] ![]() (/u/ → [v]). The form with [j]-insertion is more typical in Western Armenian and preferred by HD, while the form with /u/ changing to [v] is more typical in Eastern Armenian and preferred by SK.

(/u/ → [v]). The form with [j]-insertion is more typical in Western Armenian and preferred by HD, while the form with /u/ changing to [v] is more typical in Eastern Armenian and preferred by SK.

Words with initial sibilant-stop clusters are variably pronounced with an initial schwa, such as in [(ə)stɑˈnɑl] ![]() ‘receive’. In citation form, word-initial sibilant-stop clusters are obligatorily pronounced with an initial schwa in Western Armenian. Such schwas used to be obligatory in earlier stages of Eastern Armenian too (Ġaragyowlyan Reference Ġaragyowlyan1974: 139ff), but the absence of a schwa in initial sibilant-stop clusters has now become more common, arguably due to contact with Russian (Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 31ff; see also Avetisyan Reference Avetisyan2011: 14). For both dialects, the presence of the schwa in word-initial sibilant-stop clusters varies in connected speech. For example, Ġaragyowlyan (Reference Ġaragyowlyan1974: 143ff) reports that the presence of Eastern word-initial schwa before sibilant-stop clusters depends on the preceding word’s coda. A word-initial invariant schwa is found before other consonant clusters in a handful of words, such as in Yerevan [əŋˈkeɾ] and Beirut [əŋˈɡeɾ]

‘receive’. In citation form, word-initial sibilant-stop clusters are obligatorily pronounced with an initial schwa in Western Armenian. Such schwas used to be obligatory in earlier stages of Eastern Armenian too (Ġaragyowlyan Reference Ġaragyowlyan1974: 139ff), but the absence of a schwa in initial sibilant-stop clusters has now become more common, arguably due to contact with Russian (Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 31ff; see also Avetisyan Reference Avetisyan2011: 14). For both dialects, the presence of the schwa in word-initial sibilant-stop clusters varies in connected speech. For example, Ġaragyowlyan (Reference Ġaragyowlyan1974: 143ff) reports that the presence of Eastern word-initial schwa before sibilant-stop clusters depends on the preceding word’s coda. A word-initial invariant schwa is found before other consonant clusters in a handful of words, such as in Yerevan [əŋˈkeɾ] and Beirut [əŋˈɡeɾ] ![]() ‘friend’.

‘friend’.

A variety of coda clusters are found in word-medial and word-final positions. Almost all two-consonant coda clusters with falling sonority are attested without schwa epenthesis. However, nasal + obstruent clusters are homorganic, and coda /l/ generally does not occur in native coda clusters except after /j/. A few exceptional two-consonant coda clusters with rising or level sonority are attested, with examples below:

The accompanying recording of Yerevan /pɑteˈɾɑzm/ is pronounced [pɑteˈɾɑsm̥], and SK sometimes deletes the final /m/ in this word. The accompanying recording of Beirut /meˈdɑkʰs/ is pronounced [meˈdɑks] with an unaspirated [k] due to the following sibilant (see Beirut Armenian plosives) though still without schwa. The orthography indicates other coda clusters with rising or level sonority, but many of these are pronounced with an intervening schwa (Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 26–27).

Stem-final /-kʰ/ is an exception to these generalizations about coda clusters: it can occur after any singleton consonant or two-consonant cluster without any degree of schwa epenthesis, regardless of sonority, in both dialects (see Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 83; Dolatian Reference Dolatian2021 for phonological analyses). Figure 9 shows spectrograms of /pɑɾtkʰ, bɑɾdkʰ/ [pɑɹ̝̊tkʰ, pɑɹ̝̊tkʰ] ![]() ‘debt’ from SK and HD, which each show three final consonant articulations — a spirantized /ɾ/, a /t, d/ constriction and release, and a final aspirated /kʰ/ release — with no acoustic evidence for schwa.Footnote 11

‘debt’ from SK and HD, which each show three final consonant articulations — a spirantized /ɾ/, a /t, d/ constriction and release, and a final aspirated /kʰ/ release — with no acoustic evidence for schwa.Footnote 11

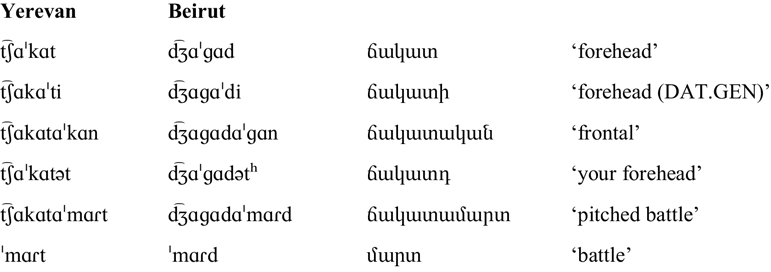

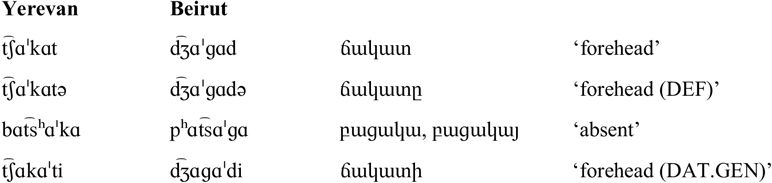

Word-level prosody

Words in citation form are typically stressed on the final syllable, unless the final syllable nucleus is schwa. If the final syllable nucleus is schwa, then stress is on the last non-schwa vowel, which is typically in the penultimate syllable. The table below illustrates these stress generalizations for the word /t͡ʃɑˈkɑt, d͡ʒɑˈɡɑd/ ![]() ‘forehead’ and several of its derived forms. In the forms with a full vowel in the final syllable, stress is word-final, no matter whether the word ends in an open syllable (row 2) or a closed syllable (rows 1, 3 and 5), or whether the word is unsuffixed (row 1), suffixed (rows 2–3) or a compound (row 5). The form /t͡ʃɑˈkɑtət, d͡ʒɑˈɡɑdətʰ/

‘forehead’ and several of its derived forms. In the forms with a full vowel in the final syllable, stress is word-final, no matter whether the word ends in an open syllable (row 2) or a closed syllable (rows 1, 3 and 5), or whether the word is unsuffixed (row 1), suffixed (rows 2–3) or a compound (row 5). The form /t͡ʃɑˈkɑtət, d͡ʒɑˈɡɑdətʰ/ ![]() (row 4) has a final schwa and penultimate stress.

(row 4) has a final schwa and penultimate stress.

Final non-schwa stress with suffixes and in compounds

Figure 9 Spectrograms of /pɑɾtkʰ/ and /bɑɾdkʰ/ ![]() ‘debt’, illustrating a three-consonant coda.

‘debt’, illustrating a three-consonant coda.

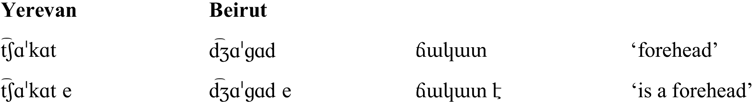

Clitics are unstressed, as illustrated in the table below (contributed by VP), as well as in the Yerevan form /viˈ t͡ʃum ejin/ in the first phrase of the North Wind and Sun (Transcription of recorded passage), which contains a bisyllabic clitic.

Clitics are unstressed

For words with only schwa nuclei, our speakers produce final stress: /fəsˈtəx/ ![]() ‘pistachio’. Ač̣aṙyan (Reference Ač̣aṙyan1971: 194) reports that these words have final stress, while Vaux (Reference Vaux1998: 133) reports initial stress. This disagreement may reflect inter-speaker variation or differences in (loan)word origin. There are very few words with only schwa nuclei in Armenian and many of these words are onomatopoeic, which tend to be exceptional cross-linguistically.

‘pistachio’. Ač̣aṙyan (Reference Ač̣aṙyan1971: 194) reports that these words have final stress, while Vaux (Reference Vaux1998: 133) reports initial stress. This disagreement may reflect inter-speaker variation or differences in (loan)word origin. There are very few words with only schwa nuclei in Armenian and many of these words are onomatopoeic, which tend to be exceptional cross-linguistically.

Besides primary stress, most grammars report that Armenian has word-initial secondary stress (Vaux Reference Vaux1998: 134; Abeġyan Reference Abeġyan1933: 20; Ġaragyowlyan Reference Ġaragyowlyan1974: 133; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009). Some sources report that secondary stress can fall on word-initial schwas (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 2; Johnson Reference Johnson1954: 11).

Some notable classes of exceptions to the general stress patterns include ordinal numbers, vocatives, and hypocoristics, as well as some common adverbs and a few other idiosyncratic words, suffixes, and clitics, though exceptional non-final stress can be variable (Vaux Reference Vaux1998:ch4; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009). For example, the Yerevan Armenian clitic /el/ ![]() ‘also’ can carry stress, while the Beirut cognate /ɑl/

‘also’ can carry stress, while the Beirut cognate /ɑl/ ![]() cannot, as in Yerevan /t͡ʃɑkɑt ˈel, t͡ʃɑˈkɑt el/

cannot, as in Yerevan /t͡ʃɑkɑt ˈel, t͡ʃɑˈkɑt el/ ![]() contributed by VP versus Beirut /d͡ʒɑˈɡɑd ɑl/

contributed by VP versus Beirut /d͡ʒɑˈɡɑd ɑl/ ![]() ‘also a forehead’.

‘also a forehead’.

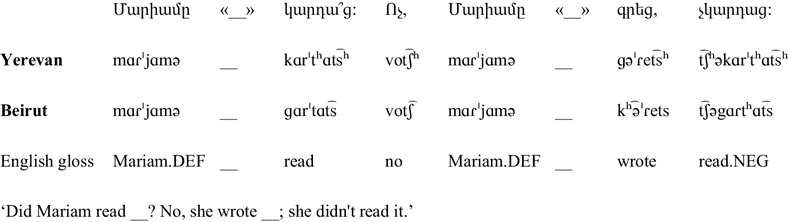

Exceptional stress also occurs in some morphological alternations, which is also dialect-specific. For example, in subjunctive past imperfective forms in HD’s Beirut Western Armenian, stress exceptionally occurs on a theme vowel which precedes the tense-agreement suffix, regardless of where the theme vowel is in the word. This means that the Beirut Armenian subjunctive second-person singular form has stress on the penultimate syllable – which contains the theme vowel – even though the final syllable has a peripheral vowel that would normally be stressed (cf. rows 2–4 in the table below). In Yerevan Eastern Armenian, the final syllable (the tense-agreement suffix) receives expected stress in all inflected forms.

Idiosyncratic theme vowel stress in Beirut Armenian

Additionally, in negative past perfective verb forms, the finite verb negation prefix ![]() is /t͡ʃ-, t͡ʃə-/ in Western Armenian, and /t͡ʃʰ-, t͡ʃʰə-/ in Eastern Armenian. The prefix has exceptional initial stress in Western Armenian, but is unstressed as expected in Eastern Armenian. The recorded sentences that accompany the subsection Acoustics of stress and focus illustrate the contrast of Yerevan Eastern

is /t͡ʃ-, t͡ʃə-/ in Western Armenian, and /t͡ʃʰ-, t͡ʃʰə-/ in Eastern Armenian. The prefix has exceptional initial stress in Western Armenian, but is unstressed as expected in Eastern Armenian. The recorded sentences that accompany the subsection Acoustics of stress and focus illustrate the contrast of Yerevan Eastern![]() / and Beirut Western /ˈ

/ and Beirut Western /ˈ![]()

![]() ‘to read (3SG PST PRF NEG)’. The difference in stress correlates with the variable deletion of initial schwa in the Yerevan Eastern forms (final stress) but not the Beirut Western forms (initial stress).

‘to read (3SG PST PRF NEG)’. The difference in stress correlates with the variable deletion of initial schwa in the Yerevan Eastern forms (final stress) but not the Beirut Western forms (initial stress).

Sentence-level intonation and focus

In Eastern Armenian, broad focus (neutral context) sentences can have either SVO or SOV word order (Samvelian, Faghiri & Khurshudyan Reference Samvelian, Faghiri and Khurshudyan2023). In broad-focus SVO sentences in Eastern Armenian, each prenuclear prosodic constituent (i.e., S and V) has a rising -L H- contour aligned with its right edge. Each prenuclear constituent has a successively lower pitch, i.e., there is downstep or declination between successive H tone targets (Haghverdi Reference Haghverdi2016; Skopeteas Reference Skopeteas2021). Skopeteas (Reference Skopeteas2021) also finds sentence-final lowering in Eastern Armenian, which he analyzes as an L-

![]() $\%$

boundary tone at the right edge of the intonational phrase. In Western Armenian, broad focus sentences have an unmarked SOV order, and Toparlak (Reference Toparlak2019) reports the same intonational patterns as Skopeteas (Reference Skopeteas2021).Footnote 13 Western Armenian listeners perceive nuclear accent on the pre-verbal element – usually the object – and the verb undergoes post-focal compression or deaccenting (Toparlak Reference Toparlak2019; Toparlak & Dolatian Reference Toparlak and Dolatian2022; Dolatian Reference Dolatian, Özçelik and Kennedy2022).

$\%$

boundary tone at the right edge of the intonational phrase. In Western Armenian, broad focus sentences have an unmarked SOV order, and Toparlak (Reference Toparlak2019) reports the same intonational patterns as Skopeteas (Reference Skopeteas2021).Footnote 13 Western Armenian listeners perceive nuclear accent on the pre-verbal element – usually the object – and the verb undergoes post-focal compression or deaccenting (Toparlak Reference Toparlak2019; Toparlak & Dolatian Reference Toparlak and Dolatian2022; Dolatian Reference Dolatian, Özçelik and Kennedy2022).

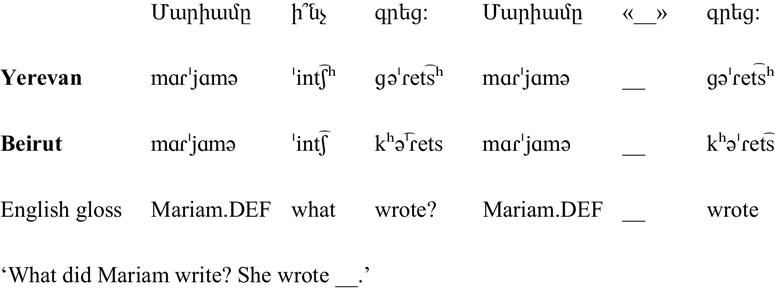

Skopeteas (Reference Skopeteas2021) gives experimental evidence that narrow or contrastive focus is marked by a falling contour H*+L on the stressed syllable of the focused word.Footnote 14 The H* tone – indicated by maximal f0 – is aligned with the left edge of the stressed syllable, followed by the L tone, indicated by a steep fall starting either immediately after the H* or at the right edge of the prosodic word. For questions, Skopeteas (Reference Skopeteas2021) finds a sharp rise L+H* on the stressed syllable of either the focused element in narrow focus questions or the verb in broad focus questions. After this rise, he finds post-focal deaccenting. Toparlak & Dolatian (Reference Toparlak and Dolatian2022) find similar results for unmarked, SOV sentences with narrow object focus in Western Armenian: a pitch rise on the focused word, followed by post-focal deaccenting.

Simple yes–no questions with the unmarked SOV order have a final pitch rise on the verb (H

![]() $\%$

) in both dialects, with no change in word order. Wh-questions have a pitch rise on the wh-word followed by post-focal deaccenting. In Eastern Armenian, wh-questions have a sentence-final fall (L

$\%$

) in both dialects, with no change in word order. Wh-questions have a pitch rise on the wh-word followed by post-focal deaccenting. In Eastern Armenian, wh-questions have a sentence-final fall (L

![]() $\%$

) while in Western Armenian these questions have a pitch rise (H

$\%$

) while in Western Armenian these questions have a pitch rise (H

![]() $\%$

) instead (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 29; Johnson Reference Johnson1954: 15, Ġowkasyan Reference Ġowkasyan1990; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 54ff; Toparlak & Dolatian Reference Toparlak and Dolatian2022).

$\%$

) instead (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1948: 29; Johnson Reference Johnson1954: 15, Ġowkasyan Reference Ġowkasyan1990; Dum-Tragut Reference Dum-Tragut2009: 54ff; Toparlak & Dolatian Reference Toparlak and Dolatian2022).

Acoustics of stress and focus

Previous research on Eastern Armenian reports the acoustic correlates of stress as duration, intensity, and/or f0 including a final pitch rise (T’oxmaxyan Reference T’oxmaxyan1983: 119; Xačatryan Reference Xačatryan1988: 76–79), but most of this earlier work did not clearly differentiate word-level stress and intonation. Skopeteas (Reference Skopeteas2021) reports that a word-final pitch rise is a cue to the right edge of prenuclear constituents in Yerevan Armenian (see also Sentence-level intonation and focus and Haghverdi Reference Haghverdi2016). Both final and non-final stressed syllables can host a nuclear pitch accent that is aligned earlier within the syllable than this right edge tone.

For Western Armenian, Athanasopoulou et al. (Reference Athanasopoulou, Vogel and Dolatian2017) report that word-level stress is cued only by mean f0 and f0 excursion. They find that word-level stress has similar acoustic cues regardless of whether stress is final or non-final (due to a final schwa nucleus). Using the same data, Vogel & Athanasopoulou (Reference Vogel and Athanasopoulou2018) also report that stress does not involve significant enhancement in duration. To measure a word-level stress and focus paradigm, we elicited four target word forms in the following two carrier contexts, adapted from Athanasopoulou et al. (Reference Athanasopoulou, Vogel and Dolatian2017) and Vogel, Athanasopoulou & Pincus (Reference Vogel, Athanasopoulou, Pincus, Heinz, Goedemans and van der Hulst2016):

Non-focus condition

Focus condition

The four target word forms are listed below:

As described in Word-level prosody, stress is final in these forms except /t͡ʃɑˈkɑtə/, /d͡ʒɑˈɡɑdə/ ![]() , which has a final schwa nucleus. The first and second row contrast final and non-final stress. The third row has a trisyllabic form with final stress, for comparison with the non-final stress in the second row. The fourth row contrasts unstressed word-medial /ɑ/ with the stressed word-medial syllable in the second row.

, which has a final schwa nucleus. The first and second row contrast final and non-final stress. The third row has a trisyllabic form with final stress, for comparison with the non-final stress in the second row. The fourth row contrasts unstressed word-medial /ɑ/ with the stressed word-medial syllable in the second row.

Vowel measurements for these elicitations are shown in Figures 10–11. HD (Beirut Western Armenian) produced stressed /ɑ/ vowels with longer duration, higher F1 and lower F2 (i.e., more peripheral). In the focus condition, stressed /ɑ/ also had a higher f0 and a wider range. SK (Yerevan Eastern Armenian) produced stressed /ɑ/ vowels with a similar effect on F2, but duration and f0 were affected only in the focus condition (see Skopeteas Reference Skopeteas2021). This suggests that duration may be an acoustic correlate of stress for HD’s Beirut Armenian, while vowel space expansion may be a stress correlate for both dialects. Both speakers showed post-focal compression or deaccenting. In two of four tokens, word-final schwa had an f0 rise even though it followed the stressed syllable (Figure 13).

Figure 10 Measurements for /ɑ/ vowels for SK (Yerevan Armenian). Connected points show the actual token measurements and large open circles show group means for each measure. Gray circles (/ɑ/ vowels without primary stress) include six tokens per group, and black circles (/ɑ/ vowels with primary stress) include three tokens per group.

Figure 11 Measurements for /ɑ/ vowels for HD (Beirut Armenian). Connected points show the actual token measurements and large open circles show group means for each measure. Gray circles (/ɑ/ vowels without primary stress) include six tokens per group, and black circles (/ɑ/ vowels with primary stress) include three tokens per group.

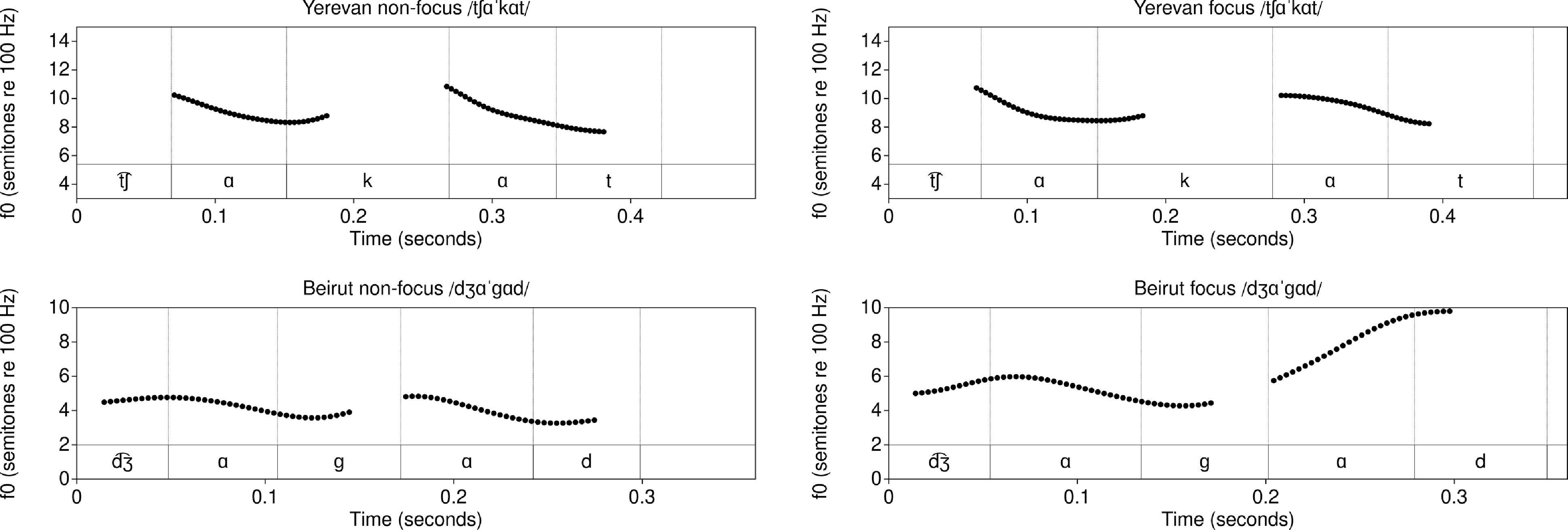

Figure 12 f0 contours for /t͡ʃɑˈkɑt/ and /d͡ʒɑˈɡɑd/ ‘forehead’ (Yerevan Armenian non-focus top left, Yerevan Armenian focus top right, Beirut Armenian non-focus bottom left, Beirut Armenian focus bottom right).

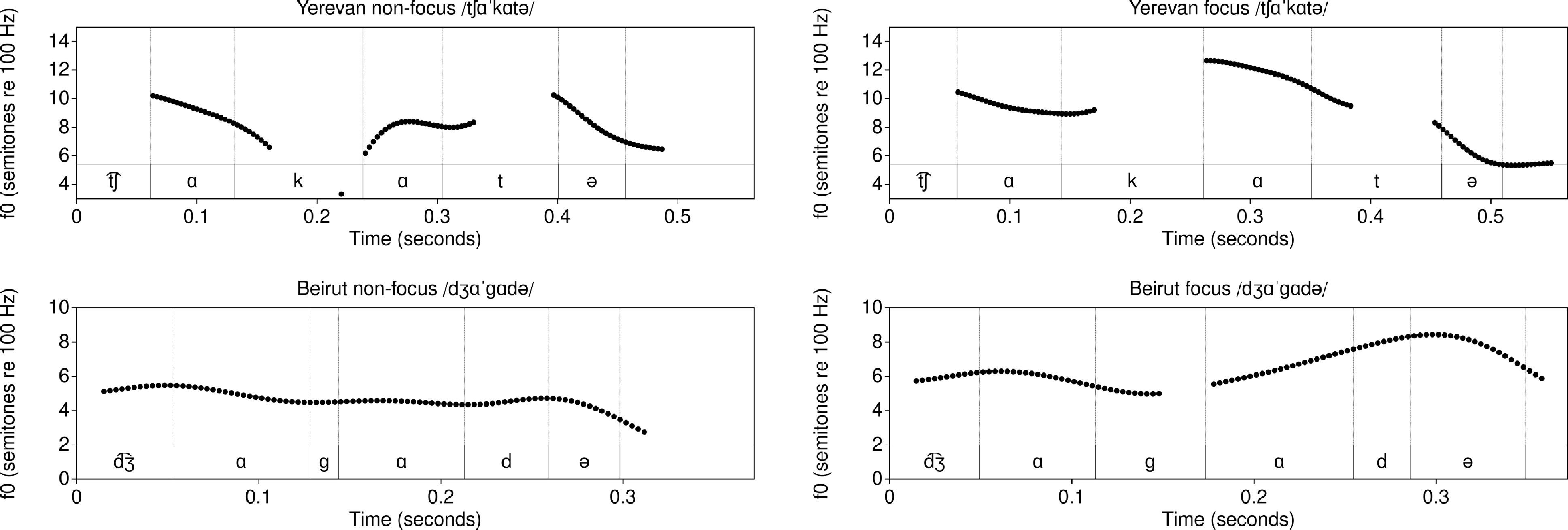

Figure 13 f0 contours for /t͡ʃɑˈkɑtə/ and /d͡ʒɑˈɡɑdə/ ‘forehead (DEF)’ (Yerevan Armenian non-focus top left, Yerevan Armenian focus top right, Beirut Armenian non-focus bottom left, Beirut Armenian focus bottom right).

As Figures 10–11 and 12–15 illustrate, the f0 of stressed syllables is higher under the focused condition than either unstressed or stressed syllables in the non-focused condition, except in SK’s recording of bisyllabic /t͡ʃɑˈkɑt/. In our elicitations, all vowels were also longer in words under focus.

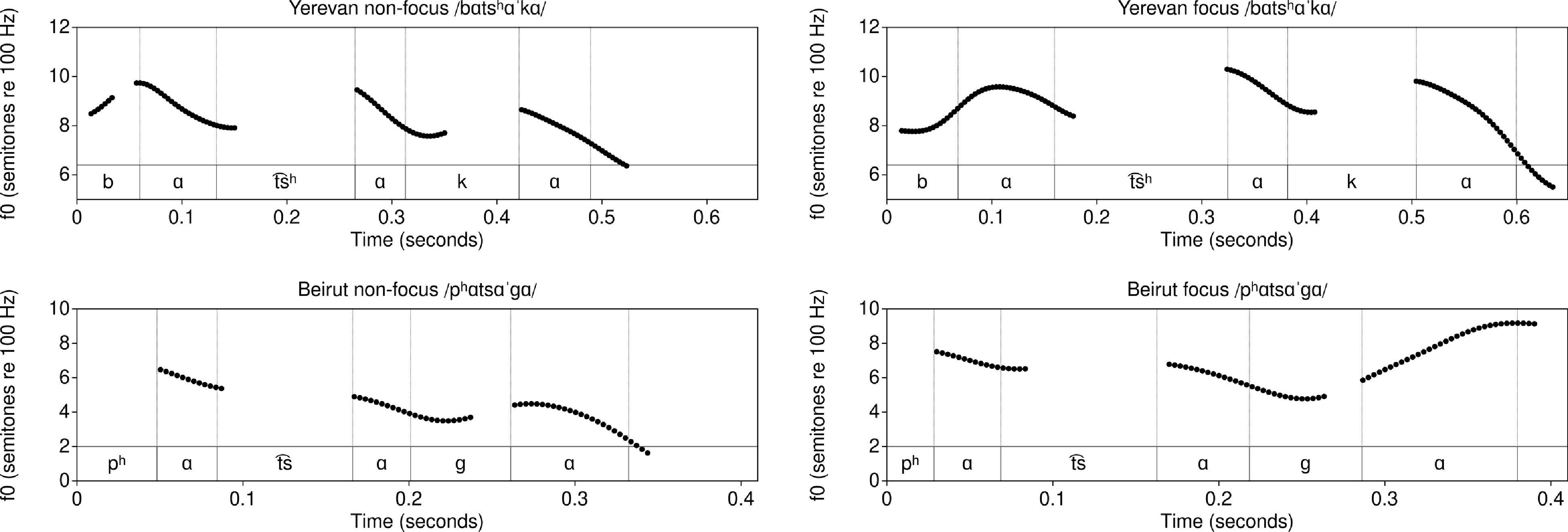

Figure 14 f0 contours for /t͡ʃɑkɑˈti/ and /d͡ʒɑɡɑˈdi/ ‘forehead (DAT.GEN)’ (Yerevan Armenian non-focus top left, Yerevan Armenian focus top right, Beirut Armenian non-focus bottom left, Beirut Armenian focus bottom right).

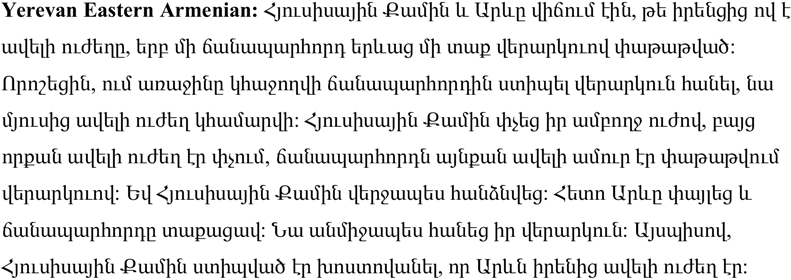

Figure 15 f0 contours for /bɑt͡sʰɑˈkɑ/ and /pʰɑt͡sɑˈɡɑ/ ‘absent’ (Yerevan Armenian non-focus top left, Yerevan Armenian focus top right, Beirut Armenian non-focus bottom left, Beirut Armenian focus bottom right).

Transcription of recorded passage

Broad phonetic transcription