Brunei Malay (ISO 639-3: kxd) is spoken in the Sultanate of Brunei Darussalam and also in some nearby places in East Malaysia such as Miri and Limbang in Sarawak (Asmah Reference Omar2008: 65), on the island of Labuan (Jaludin Reference Chuchu2003: 35) and around Beaufort in western Sabah (Saidatul Reference Saidatul, Omar, Said and Majid2003). Of the population of about 400,000 in Brunei, about two-thirds are native speakers of Brunei Malay (Clynes Reference Clynes2001), and the language is generally used as a lingua franca between the other ethnic groups (Martin Reference Martin1996), so even most Chinese Bruneians, numbering about 45,000 (Dunseath Reference Dunseath1996), are reasonably proficient in Brunei Malay. Although Standard Malay is promoted as the national language of Brunei (Clynes & Deterding Reference Clynes and Deterding2011), in fact it is only used in formal situations, such as government speeches and television and radio broadcasts (Martin Reference Martin1996). The language that is spoken most extensively is Brunei Malay, though English is also widely used by the educated elite (Deterding & Salbrina 2013).

Brunei Malay is generally treated as a dialect of Malay (Jaludin Reference Chuchu2003), though some would regard it as a language in its own right (Martin Reference Martin1996, Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer, Adelaar and Himmelmann2005). Nothofer (Reference Nothofer and Steinhauer1991) estimates the level of lexical cognates between Brunei Malay and Standard Malay to be about 84%. The pronunciation of Brunei Malay differs quite substantially from Standard Malay, particularly in having only three vowels, /i a u/, compared to the six of Standard Malay, /i e a o u ə/ (Asmah Reference Omar2008: 55; Clynes & Deterding Reference Clynes and Deterding2011), and also in having no initial /h/ (Clynes Reference Clynes2001). These issues will be discussed in greater detail below.

In fact, Brunei Malay is rather closer to Kedayan, the dialect traditionally spoken by land-dwelling farmers, and also to Kampung Ayer, the dialect spoken by the community that lives in the Water Village in the capital of Brunei (Martin & Poedjosoedarmo Reference Martin and Poedjosoedarmo1996). Nothofer (Reference Nothofer and Steinhauer1991) estimates the level of lexical cognates between Brunei Malay and Kedayan to be 94%, and that between Brunei Malay and Kampung Ayer also to be 94%. In terms of phonology, the most salient differences between Brunei Malay and Kedayan are the absence of /r/ in Kedayan (Soderberg Reference Soderberg2014), while Brunei Malay has /r/ word-initially, medially and finally; and the presence of initial /h/ in Kedayan, while Brunei Malay has final /h/ but no initial /h/. Kampong Ayer also has no /r/, but unlike Kedayan, in Kampung Ayer /j/ tends to occur in place of the /r/ of Standard Malay and Brunei Malay (Martin & Poedjosoedarmo Reference Martin and Poedjosoedarmo1996).

The consultant

The recording of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ passage and also the word lists is by a 22-year-old female third-year undergraduate at Universiti Brunei Darussalam. She was selected on the basis of her self-reported proficiency in speaking the language, something that was confirmed by one of her classmates. Her first language is Brunei Malay, and she speaks it with her parents and siblings. She is also competent in both Standard Malay and English. In fact, she completed an internship at the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Brunei (the Brunei Language and Literature Bureau), where she wrote magazine articles in Standard Malay; and her written assignments and oral presentations in English are of a high quality.

Many scholars prefer to base their research on recordings of older speakers, in the search for a ‘pure’ variety of the language. For example, Jaludin (Reference Chuchu2000: 19) obtained most of his data from consultants over 50 years old. However, here we choose to study a younger speaker, to emphasise that Brunei Malay is a vibrant language widely used by young people in Brunei. While it would be valuable to record two speakers, one old and one younger, to provide an indication about how the language may be undergoing change, it is beyond the scope of the current study to offer a comprehensive coverage of variation in Brunei, and instead the study aims to provide an in-depth study of one speaker. Although the pronunciation that the consultant uses does not include all the features of traditional Brunei Malay, it reflects the way that the language is currently used by young people.

Data and analysis

‘The North Wind and the Sun’ text was translated into Brunei Malay with the help of colleagues in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam. The consultant then read it through carefully and suggested some changes to ensure that it conforms to the way that she speaks the language.

Word lists were derived to illustrate all the consonants and vowels of Brunei Malay. Care was taken to ensure that all the items are common words in the language. In addition, the consultant helped in finding words to illustrate the occurrence of the /u j/ diphthong, such as sikoi ‘melon’ and langoi ‘look up’.

The passage and word lists were recorded directly onto a Sony laptop computer using a high-quality Shure US692 microphone and saved in WAV format. Analysis was done by repeated listening by both researchers, and measurements of the VOT of the consonants and formant frequencies of the vowels were made using Praat (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2013).

Consonants

Brunei Malay can be considered as having the 18 consonants shown in the Consonant table. This is the inventory given in Jaludin (Reference Chuchu2003: 44), though Mataim (Reference Bakar2007: 28) excludes /w/ and /j/ on the grounds that they are ‘margin high vowels’, and Clynes (Reference Clynes2001) includes /w/ but excludes /j/.

The places of articulation shown in the Consonant table are the same as those in Jaludin (Reference Chuchu2000: 154) and Mataim (Reference Bakar2007: 27), though Clynes (Reference Clynes2001) prefers to group /s/ together with /tʃ dʒ ɲ/ and label them as ‘laminals’ (on the basis of the active rather than the passive articulator).

In addition to these 18 consonants, Jaludin (Reference Chuchu2000: 154) lists the glottal stop /ʔ/ as a consonant of Brunei Malay, though Jaludin (Reference Chuchu2003: 44) omits it. Poedjosoedarmo (Reference Poedjosoedarmo1996: 40) notes that a glottal stop tends to be appended to word-final vowels in utterance-final position to indicate stress, in which case it is non-contrastive. It is therefore not listed as a phoneme here.

The consonants are illustrated in the word list below, in which the words in italics are the orthographic versions listed in the Brunei Malay dictionary (DBP 2007). They are all common words in Brunei Malay, and as far as possible they were chosen as minimal pairs for the voiceless/voiced contrasts, so for example parang ‘machete’ contrasts with barang ‘thing’.

All these 18 consonants can occur in initial position except for /h/, which usually only occurs in final position. As a result, words that have initial /h/ in Standard Malay, such as hutan /h u t a n/ ‘forest’ and hitam /h i t a m/ ‘black’ are utan /u t a n/ and itam /i t a m/ respectively in Brunei Malay. In addition, [h] may be inserted between two identical vowels in words such as saat ‘second’, which may be pronounced [s a h a t] (Mataim Reference Bakar2007: 128), and tuut ‘knee’, which may be [t u h u t] (Clynes Reference Clynes2001). In fact, in the passage, matahari ‘sun’ might be analysed as /m a t a a r i/ and the [h] is inserted between the two consecutive /a/ vowels, especially as the word is a compound of mata ‘eye’ + ari ‘day’. However, we should note that the [h] in matahari is obligatory. The optional insertion of [h] between two vowels contrasts with Standard Malay, in which a glottal stop is typically inserted in the middle of words such as saat (Clynes & Deterding Reference Clynes and Deterding2011). Although /h/ is clearly articulated at the end of ngalih, rumah and labih in the word list above and all three tokens of jubah ‘cloak’ in the passage, it is omitted from the end of iatah ‘is’ in the reading of the passage, possibly because it is a function word.

All the consonants can occur in final position except the palatal sounds /tʃ dʒ ɲ/ and the voiced plosives, /b d ɡ/. These sounds are only found in final position in a few loanwords such kabab /k a b a b/ ‘kebab’ (Clynes Reference Clynes2001).

The voiceless plosives of Brunei Malay are unaspirated, as is the case for most varieties of Malay (Clynes & Deterding Reference Clynes and Deterding2011), as well as Indonesian (Soderberg & Olson Reference Soderberg and Olson2008). The initial voiceless plosives in the word list above all have minimal aspiration: for the /p/ in parang ‘machete’, VOT is measured at 17 msec; for /t/ in taun ‘year’, it is 16 msec; and for /k/ in kali ‘times’, it is 29 msec. There is a little more aspiration on the voiceless plosives in medial position: the /t/ in yatim ‘orphan’ has VOT of 24 msec, while the tokens of /k/ in wakil ‘representative’ and laki ‘husband’ have VOT of 56 msec and 49 msec respectively. In ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ passage, all voiceless plosives in both initial and medial positions have minimal aspiration, except for the /k/ in the six tokens of kuat ‘strong’, which has an average VOT of 44 msec. Apart from kuat, the largest value of VOT for /k/ is 30 msec in ngakun ‘admit’. For /p/, the average VOT is 17 msec, for /t/ it is 18 msec and for /k/ (excluding kuat) it is 27 msec, and there is no difference between the results for initial and medial plosives. The VOT for /k/ in the passage is significantly longer than that for /p/ (t = 7.02, df = 23, p < .001) and also for /t/ (t = 4.32, df = 18, p < .001) but there is no significant difference between the values for /p/ and /t/ (t = 0.2, df = 32, p = .84). Greater aspiration for /k/ than for /p/ and /t/ is similar to what has been reported in other languages, such as English (Docherty Reference Docherty1992), French (Nearey & Rochet Reference Nearey and Rochet1994), and Chinese (Deterding & Nolan Reference Deterding, Nolan, Trouvain and Barry2007). Voiceless plosives in final position may be unreleased, as is the case with dapat ‘can’ in the third line of the passage and kuat ‘strong’ in the last line.

/b d ɡ/ are generally fully voiced. In the word list, voicing starts 146 msec before the release of the plosive in barang ‘thing’ and 88 msec in daun ‘leaf’, though surprisingly there is no prevoicing in gaji ‘wage’. In the passage, most instances of /b d ɡ/ occur following another voiced sound, either a vowel or a nasal, and there is no break in voicing. However, diurang ‘they’, which occurs at the start of a sentence, has 17 msec of voicing before the release of the plosive, and dari ‘than’, which occurs after kuat ‘strong’ near the end of the passage, has 76 msec of voicing before the release of the plosive and following the silence associated with the unreleased /t/ in kuat.

/r/ is usually trilled or tapped, though it may sometimes be an approximant. In the word list, parang ‘machete’ and barang ‘thing’ both have a trilled /r/, cari ‘search’ has a tap, and both jari ‘finger’ and rumah ‘house’ have an approximant. In ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ passage, most tokens of /r/ are tapped, but the /r/ in the second token of pangambara ‘traveller’ is trilled, and so is the /r/ at the end of batangkar ‘argue’, while the /r/ in diurang ‘they’ and also at the end of mamancar ‘shine’ is an approximant. The first /r/ in banar-banar ‘really’ is dropped, but that is the only instance of omitted /r/.

/l/ is generally clear in all positions, including at the end of words such as sambal ‘shrimp paste’ and wakil ‘representative’ in the word list and also pasal ‘about’ in the passage.

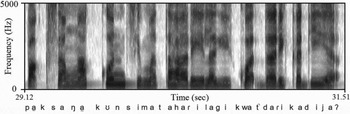

Figure 1 shows a spectrogram of the final phrase paksa ngakun si Matahari lagi kuat dari kadia ‘must admit the Sun more strong than him’, illustrating many of the features of consonants discussed above. Notice the use of a tapped /r/ in matahari ‘sun’ and also dari ‘than’, and the occurrence of a glottal stop at the end of the final word, kadia ‘him’.

Figure 1 Spectrogram of the last phrase of the passage.

In paksa ‘must’, there is virtually no aspiration on the initial /p/, with VOT measured at 12 msec. In contrast, there is a little aspiration on the /k/ in ngakun ‘admit’ and kadia ‘him’, with VOT measured at 30 msec and 29 msec respectively, and the /k/ in kuat ‘strong’ has VOT of 33 msec.

Vowels

There are just three vowels in Brunei Malay: /i a u/ (Mataim Reference Bakar2007: 35). Their quality is shown in the vowel quadrilateral. The words illustrating the occurrence of the three vowels are all common words in Brunei Malay, and in each one the vowel in question occurs in both syllables.

With such a sparsely filled vowel space, there is considerable scope for allophonic variation. For example, in closed final syllables, /i/ may be [ɪ] or [e], and /u/ may be [ʊ] or [o] (Clynes Reference Clynes2001). In ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ passage, angin ‘wind’ and makin ‘the more’ both have [ɪ], and maniup ‘blow’ and pun ‘then’ both have [ʊ].

The frequency of the first two formants of all the vowels in the recording of the passage was measured in Praat, with the exception of the first syllable of satuju ‘agree’ and sakuat ‘as strong’, for which there is no vowel. (The representation of these words will be discussed below in the section on syllable structure.) The formant frequencies were then converted to an auditory Bark scale using the formula suggested by Traunmüller (Reference Traunmüller1990) and plotted on inverted axes of F1 against F2 to show the quality of the vowels. In Figure 2, ellipses are drawn based on a bivariate normal distribution to encircle 68% of the tokens of each vowel, representing plus or minus one standard deviation (McCloy Reference McCloy2012).

Figure 2 The acoustic quality of the vowel phonemes.

In addition to the allophonic variation involving /i/ and /u/ mentioned above, there is substantial variation in the quality of /a/, as can be seen by the size of the ellipse for /a/ in Figure 2 below. One tendency is for /a/ before a velar consonant such as /k/ or /ŋ/ or final /h/ to have a relatively back quality. A further example of variation in the realisation of /a/ involves the prefixes ba-, maN- and paN-, such as in batangkar ‘argue’, mamigang ‘hold’, maniup ‘blow’, and pangambara ‘traveller’ from the passage. In most tokens of these words, the vowel in the first syllable has a relatively close quality, so it might be represented as [ə]. However, in mamigang and also the third token of pangambara, the vowel has a more open quality, so it is [a]. The vowel plot with these prefixes shown separately from /a/ and labelled as ‘e’ is in Figure 3. It can be seen that the quality of these vowels substantially overlaps with /u/, while there is reduced overlap compared with Figure 2 between /u/ and the remaining tokens of /a/.

Figure 3 The acoustic quality of the vowels with the prefix shown as ‘e’.

In fact, the Brunei Malay dictionary (DBP 2007) uses ‘e’ to represent the vowel in these prefixes, so for example mamigang ‘hold’ and maniup ‘blow’ are shown with ‘e’ in the first syllable. However, here we prefer to use ‘a’ rather than ‘e’ in these words as this is consistent with the claim that there are only three vowels in Brunei Malay, /i a u/, even if we acknowledge that /a/ may sometimes be pronounced as [ə]. Furthermore, this is how other scholars represent these words, so for example Jaludin (Reference Chuchu2003: 56) discusses the pronunciation of mamigang, Clynes (Reference Clynes2001) includes example sentences with mambali ‘buy’ and manjual ‘sell’, and Mataim (Reference Bakar2007: 182) offers a detailed analysis of the pronunciation of mambawa ‘carry’. Finally, as mentioned above, in the recording of the passage, mamigang and one token of pangambara are pronounced with [a] in the first syllable, so the use of an open vowel in these prefixes does sometimes occur.

Diphthongs?

There are three vowels that might be listed as diphthongs in Brunei Malay: /a j/, /a w/ and /u j/ (Mataim Reference Bakar2007: 36). The following words illustrate their occurrence:

These three diphthongs usually occur in word-final position, though kaola, which is listed in DBP (2007: 151) as the first person pronoun when talking to people of noble rank, has /a w/ in its initial syllable. A diphthong can never be followed by a consonant within the same syllable (so kaola is /k a w.l a/), and the basic syllable structure of Malay is CVC, so the diphthongs are regarded as a monophthong vowel followed by a glide. This is consistent with most analyses of Malay (e.g. Clynes Reference Clynes1997, Clynes & Deterding Reference Clynes and Deterding2011), and Asmah (Reference Omar1983: 44) similarly notes that although diphthongs are quite common in Malay, phonemically they can be analysed as a monophthong vowel followed by a glide.

Two issues remain with these vowels: Why is /u j/ spelled as ‘oi’? And is there a distinction between /o j/ and /u j/?

The Brunei Malay dictionary (DBP 2007) lists words such as /p a l u j/ ‘stupid’ as paloi, but it then shows the pronunciation as /p a l u i/. In most entries in the dictionary, the pronunciation is not given, as it is predictable from the spelling and showing the pronunciation would therefore be redundant. On this basis, it is not clear why the spelling is not listed as palui. In fact, in addition to paloi, the dictionary offers both spelling and pronunciation for the following words (here, the orthographic version is shown first, to reflect the entry in the dictionary):

The second issue involves a comparison of the pronunciation of paloi ‘stupid’ and sikoi ‘melon’. The consultant insists that, for her, they do not rhyme, and paloi is [p a l u i] while sikoi is [s i k o i]. This may reflect the fact that the consultant is quite young, so the description presented here is of ‘modern’ Brunei Malay rather than a more traditional variety. Nevertheless, in analysing the pronunciation of this speaker, the lack of a rhyme between paloi and sikoi suggests that, in her idiolect, there are more than just the three potential diphthongs listed above, and it is not clear how sikoi should be analysed in terms of one of the three monophthong vowels followed by a glide. Clynes (Reference Clynes2001) states that a relatively open allophone of /u/ can occur in paloi, but he also claims that the same open allophone can occur in sikoi, and this is not supported by the observation of the consultant that they do not rhyme. It seems that the occurrence of this allophonic variation for /u/ before /j/ varies between speakers and may also be lexically conditioned.

Syllable structure

As with other varieties of Malay (Clynes & Deterding Reference Clynes and Deterding2011), the syllable structure of Brunei Malay is CVC, where only V is obligatory. However, at the phonetic level, CGVC syllables may be heard, where G is an approximant. For example, in the passage kuat ‘strong’ is sometimes pronounced as [k w a t]. Similarly, siapa ‘who’ is pronounced as [s j a p a] and diurang ‘they’ is [d j u r aŋ], with two syllables rather than the underlying three.

In addition, satuju ‘agree’ and sakuat ‘as strong’ are pronounced as [s t u dʒu] and [s k w a t] respectively, with no vowel between the initial /s/ and the plosive. This appears to be a recent innovation, as older speakers would have [a] in the first syllable of these two words. We could either say that Brunei Malay now allows initial clusters with /s/ followed by a plosive, as is proposed by Asmah (Reference Omar1983: 51) for Standard Malay to account for words such as stor ‘store’ that originate from English; or we can say that the vowel in the sa- prefix may be omitted in some circumstances. Here we prefer the latter analysis.

Asmah (Reference Omar1983: 52) notes that most words in the Austronesian languages are bisyllabic, though they may be longer as a result of affixation. Indeed, all the words chosen for the consonant and vowel word lists above consist of two syllables. In the passage, a number of words are longer as a result of prefixes; for example, batangkar ‘argue’ is ba+tangkar, maniup ‘blow’ is maN+tiup, and mamigang ‘hold’ is maN+pigang.

Transcription of recorded passage: ‘The North Wind and the Sun’

Orthographic version

Masa si Angin Utara sama si Matahari batangkar pasal siapa yang lagi kuat, ada tia urang pangambara datang. Diurang satuju siapa yang dapat manggalkan jubah pangambara atu, iatah yang paling kuat. Si Angin Utara pun maniup sakuat-kuatnya, tapi makin kuat ia maniup, makin tah pulang pangambara atu mamigang banar-banar jubahnya. Si Angin Utara pun mangalah. Udah atu si Matahari lagi mamancar kuat-kuat sampai pangambara atu inda tahan, tarus ia buka jubahnya. Jadi si Angin Utara pun paksa ngakun si Matahari lagi kuat dari kadia.

Phonemic transcription

m a s a s i aŋi n u t a r a s a m a s i m a t a h a r i b a t aŋk a r p a s a l s i a p a j aŋ l aɡi k u a t || a d a t i a u r aŋ p aŋa m b a r a d a t aŋ || d i u r aŋ s a t u dʒu s i a p a j aŋ d a p a t m aŋɡa l k a n dʒu b a h p aŋa m b a r a a t u i a t a h j aŋ p a l iŋ k u a t || s i aŋi n u t a r a p u n m a n i u p s a k u a t k u a tɲa || t a p i m a k i n k u a t i a m a n i u p m a k i n t a h p u l aŋ p aŋa m b a r a a t u m a m iɡaŋ b a n a r b a n a r dʒu b a hɲa || s i aŋi n u t a r a p u n m aŋa l a h || u d a h a t u s i m a t a h a r i l aɡi m a m a n tʃa r k u a t k u a t s a m p a j p aŋa m b a r a a t u i n d a t a h a n || t a r u s i a b u k a dʒu b a hɲa || dʒa d i s i aŋi n u t a r a p u n p a k s a ŋa k u n s i m a t a h a r i l aɡi k u a t d a r i k a d i a

Phonetic transcription

In this recording, the first token of kuat ‘strong’ seems to be bisyllabic, while later tokens are monosyllabic. This is why the first is transcribed as [k u a t] while later ones are shown as [k w a t]. Similarly, the first token of maniup ‘blow’ is bisyllabic and is transcribed as [mən jʊp] while the second token is trisyllabic and is shown as [mən iʊp].

The first and fourth tokens of si angin ‘the Wind’ involve three syllables, while in the second and third tokens, si is merged with angin, resulting in si angin being pronounced as two syllables which are transcribed as [s j a ŋɪn].

The use of [ʒ] instead of the expected /dʒ/ at the start of jadi ‘so’ seems to be an idiosyncrasy of the consultant's speech and is not a general feature of Brunei Malay. She herself noted this in subsequent discussions. The omission of /d/ in inda ‘not’ pronounced as [i n a] presumably arises from the fast speaking rate.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the contributions of Salbrina Sharbawi and Hjh Aznah Hj Suhaimi for help in developing early versions of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ text for Brunei Malay. We are further grateful to the two reviewers for their helpful and insightful comments. Finally, we are most grateful to the consultant for her time and patience in providing the recording and also substantial feedback about her pronunciation of Brunei Malay.