INTRODUCTION

In East Malaysia, many fishermen regard cetaceans and dugongs as fish. Despite federal and state legislation that protects the species, directed fisheries or incidental catches of cetaceans and dugongs in fisheries are not routinely monitored or documented, and animals caught are known to be consumed, traded or used as fishing bait (Jaaman et al., Reference Jaaman, Anyi and Ali1999, Reference Jaaman, Ali, Anyi, Miji, Bali, Regip, Bilang, Wahed, Bennett, Chin and Rubis2000; Jaaman & Lah-Anyi, Reference Jaaman and Lah-Anyi2003; Jaaman, Reference Jaaman2004). Perrin et al. (Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005) note that the issue of fishery by-catch of marine mammals and turtles in south-east Asia has not been addressed in a meaningful or satisfactory way anywhere in the region.

East Malaysia, which comprises the states of Sabah and Sarawak and the Federal Territory of Labuan, occupies the northern one-third of the island of Borneo (Figure 1). It is surrounded by the South China Sea to the north and west, the Sulu Sea to the north-east and the Celebes Sea to the east. East Malaysian territorial waters, including the 200-nautical mile (nm) Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), cover an area of about 330,800 km2, and the total length of the East Malaysian coastline is approximately 2607 km (MOSTE, 1997). The continental shelf is relatively wide (over 100 km) along the Sarawak coast, between 30–100 km wide on the west and north-east and becomes very narrow (<30 km) to the east of Sabah (Figure 1). It is extremely nutrient rich and supports a remarkable diversity of species (MOSTE, 1997; Oakley et al., Reference Oakley, Pilcher, Wood and Sheppard2000).

Fig. 1. East Malaysia, with location of fishing districts/landing points (towns) and the survey regions.

Although predominantly small-scale and coastal, with more than 70% of catches taking place within 30 nm from shore, the fisheries sector is an important source of employment in East Malaysia and plays a significant role in the economy (DFS, 2003; DMFS, 2004). Fish constitutes 60–70% of animal protein intake by humans, with an average annual consumption of 47.8 kg per person. Fishing is regulated by the Fisheries Regulations 1964 (within the territorial waters of Sabah) and Fisheries (Maritime) Regulations 1976 (within the territorial waters of Sarawak) and the Fisheries Act 1985 (up to the EEZ boundaries). The relevant management authorities in Sabah and Sarawak are the Department of Fisheries Sabah (DFS) and the Department of Marine Fisheries Sarawak (DMFS), respectively. The Fisheries Act 1985 established a licensing scheme, with four fishing zones defined in terms of distance from shore, fishing gears, classes of vessels and ownership (Figure 1; Table 1), with the aim of providing equitable allocation of resources and reducing conflict between traditional and commercial fishermen. According to DFS (2004) there are 20,845 registered fishermen and a fleet of 10,456 boats in Sabah (Table 2). This compares with 13,185 registered fishermen and the fishing fleet consisted of 4648 boats (DMFS, 2004; see Table 2). The fishing industry in Sarawak is more commercialized than in Sabah and a higher number of boats in Sarawak fish more than 12 nm from the coast.

Table 1. Fishing zones in East Malaysian waters.

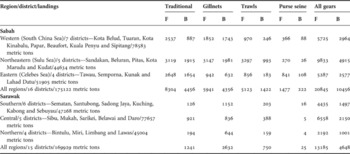

Table 2. Fishing regions, districts, landings and register of numbers of fishermen (F) and boats (B), by gear type, in Sabah (register of boats and fishermen from 1998, based on DFS, 2004) and Sarawak (fishermen not listed by gear-type, based on DFMS, 2004).

A range of commercial and traditional fishing gears (Table 3) is used to harvest a large variety of species, of which prawns are the most valuable commercially. Between 25–50% of the tonnage of fish landed in 2002, particularly from trawlers, was by-catch of miscellaneous fish (trash fish) including undesirable sizes of target species (DFS, 2003, 2004; DMFS, 2004). The commercial sector includes trawls and purse seines are operated using (inboard) motor-powered boats in Zones B to C2. Gillnets or driftnets are operated using non-motorized, outboard-motor powered or small inboard-powered boats, mainly in Zone A. The traditional sector is based mainly in Zone A (inshore), using non-motorized or outboard motor-powered boats and a wide variety of fishing gears. Fishermen often have more than one type of gear, such as a set of gillnet and long-line, or other traditional gear, and use them alternately or simultaneously, depending on locality and season (S.A.J., personal observation).

Table 3. Fishing gears and target species in East Malaysia (based on DFS, 2003; DFMS, 2004).

At least 21 species of cetaceans (three Mysticeti and 18 Odontoceti) and one sirenian are present in East Malaysian territorial and EEZ waters (Jaaman, Reference Jaaman, Ong and Gong2001, Reference Jaaman2004) and, based on records from neighbouring countries, a further nine species of cetaceans are likely to range into or pass through the study area. Of these, the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) is listed as ‘endangered’ and both dugong (Dugong dugon) and sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) as ‘vulnerable’ to extinction by the World Conservation Union (Hilton-Taylor, Reference Hilton-Taylor2000; IUCN, 2001).

The most common species in coastal waters are the Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) and Indo-Pacific humpbacked dolphin (Sousa chinensis) (Beasley & Jefferson, Reference Beasley and Jefferson1997; Jaaman, Reference Jaaman, Ong and Gong2001, Reference Jaaman2004; Jaaman et al., Reference Jaaman, Lah-Anyi, Tashi, Bennett and Chin2001), although the dugong was the most common marine mammal species recorded stranded between 1996 and 2001 (S.A.J., unpublished data). The most abundant cetaceans in deeper waters of East Malaysia are the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops aduncus), spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris) and pantropical spotted dolphin (Stenella attenuata) (Beasley, Reference Beasley1998; Jaaman, Reference Jaaman, Ong and Gong2001, Reference Jaaman2004).

This study represents a first attempt to determine the nature and magnitude of marine mammal by-catch and estimate the associated level of mortality in fisheries in East Malaysia. It uses a combination of interview surveys and on-board observations. The combination of these two methods has proved useful previously in estimating by-catch of cetaceans from a large fleet using a diversity of fishing gears in Galicia, Spain (López et al., Reference López, Pierce, Santos, Gracia and Guerra2003) and has been recommended for use in south-east Asia (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection: interview surveys

Semi-structured and informal interviews (following Dolar, Reference Dolar1994; Aragones et al., Reference Aragones, Jefferson and Marsh1997; Dolar et al., Reference Dolar, Yaptinchay, Jaaman, Santos, Muhamad, Perrin and Alava1997) were carried out between March 1997 and December 2004 at fishing villages, fish markets, fish landing jetties and anchored fishing boats in all 16 fishing districts along the coastline of Sabah (Figure 1). Interviews in Sarawak were conducted during November 1999 in Lawas and Limbang in the northern region and between September and October 2000 in the other 13 fishing districts (Figure 1). Numbers of interviews in each fishery sector are indicated in Tables 4 & 5.

Table 4. Summary of interview-based estimates of marine mammal by-catch in Sabah (B, number of boats; I, number of interviews; BC, number of boats with incidental catch; TMB, number of trips per month per boat; AT, annual total trips; BC1, number of boats with incidental catches of cetaceans; AC1, total annual catch of cetaceans; ACB1, mean annual incidental catch of cetaceans per boat; ACF1, total annual incidental catch of cetaceans raised to the whole fleet (median with 95% confidence limits); ACT1, annual incidental catch of cetaceans per 1000 trips; BC2, number of boats with incidental catches of dugongs, etc).

Table 5. Summary of interview-based estimates of marine mammal by-catch in Sarawak (B, number of boats; I, number of interviews; BC, number of boats with incidental catch; TMB, number of trips per month per boat; AT, annual total trips; BC1, number of boats with incidental catches of cetaceans; AC1, total annual catch of cetaceans; ACB1, mean annual incidental catch of cetaceans per boat; ACF1, total annual incidental catch of cetaceans raised to the whole fleet (median with 95% confidence limits); ACT1, annual incidental catch of cetaceans per 1000 trips; BC2, number of boats with incidental catches of dugongs, etc).

During site visits, fishermen (skippers and/or crew of Zone A or Zone B boats), village headmen and/or knowledgeable villagers were interviewed. Respondents were asked questions about sightings of marine mammals, the incidence and frequency of by-catches and the species involved. If fishermen reported by-catch, they were asked how many marine mammals were caught in the previous year. If the answer was none, they were then asked to give the number of animals caught in the past 5 or 10 years. Respondents were also asked if they utilized marine mammal by-catch. To assess the reliability of the respondents and their answers, several test (validation) questions were asked (i.e. to which a respondent would be expected to know the answer and to which the answer was not known). Officers from relevant local authorities (Department of Wildlife Sabah, Department of Fisheries Sabah, Sabah Parks, Department of Fisheries F.T. Labuan, Department of Marine Fisheries Sarawak, or National Parks and Wildlife Division of Sarawak Forest Department), who had extensive knowledge of the community, area, and local fishing industry, assisted in conducting the interviews.

Almost all of the fishermen interviewed could readily distinguish between dugongs and cetaceans. Based on the fishermen's descriptions and their identification from illustrations in the field guides and poster, six species or groups of cetaceans were present. In all regions, most fishermen could differentiate the Irrawaddy dolphin and Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin and finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides) from other cetaceans. Bottlenose, spinner and spotted dolphins were also reported but fishermen did not routinely distinguish these species from each other and these are therefore grouped as ‘open water dolphins’. Interviewees also recalled encountering larger cetaceans but groups of dark-coloured cetaceans that were larger than dolphins (grouped here as ‘small whales’) and extremely large animals that produced water spouts (probably sperm whales or baleen whales), were categorized as large whales.

Any indication of marine mammal by-catch in the area was photographed. Respondents were asked to identify the species of marine mammal taken and present in the area, where appropriate by referring to illustrations in field guides (Leatherwood et al., Reference Leatherwood, Reeves and Foster1983, Reference Leatherwood, Reeves, Perrin and Evans1988; Jefferson et al., Reference Jefferson, Leatherwood and Webber1993; Tan, Reference Tan1997) and a poster called Mamalia Marin Malaysia produced by the Universiti Malaysia Sabah.

Data collection: observer trips

Due to the large extent of the fishery and study area, plus limited time and availability of trained personnel, only a small proportion of fishing trips in Sabah were observed and none were followed in Sarawak. Between June 2003 and December 2004, 46 fishing trips (36 on trawlers and 10 on purse seiners), each of 1–2 days duration, were accompanied in Zone B in Sabah. Although trawlers in each region were sampled (5 western, 16 north-eastern and 15 eastern), observation of purse seine fishing was made only in the eastern region. During the study period, many purse seiners in the western and north-eastern regions and inboard-powered boats employing gillnets were inactive. No attempt was made to accompany gillnet or traditional fishermen using non-powered or outboard-powered boats because the boats were small and could not accommodate an extra person onboard. Any by-catches, as well as sightings, of marine mammals were noted during sampled fishing trips.

Analysis of by-catch rates: interview data

Interview data were analysed to estimate a ‘minimum’ by-catch rate for Sabah and Sarawak. Data were divided into strata on the basis of fishing region and gear-type. Overall, 753 boats in Sabah and 358 boats in Sarawak were included in data analysis. These were boats employing trawl nets, purse seine nets, gillnets and (for Sabah only) fish stakes. Fish stakes are seldom used in Sarawak and therefore there were no interviews for this gear type in Sarawak. Within each stratum, the boats sampled are assumed to be representative, i.e. the proportion of boats reporting by-catch and the calculated by-catch rates can be raised to give estimates for the fleets.

When answers about numbers of animals by-caught encompassed a range of values, such as 1–2, 3–5, 6–10, 11–20 per 5 or 10 years, the mid-point value was taken and all estimated by-catch rates were standardized as the number of animals taken per year. The overall mean annual by-catch per boat for each region and gear-type is given by the total number of animals caught per year divided by the number of interviews. By-catch rates for the fleets were estimated using the number of boats for each region and gear-type (DFS, 2004; DMFS, 2004) as a raising factor. The number of fishing trips per month was estimated as follows. Most of the fishermen interviewed said they fished every day except Friday (since most of them are Muslim and go to the mosque on Friday). Trawl and purse seine fishermen interviewed said they sometimes stayed overnight or at most three days at sea. Therefore, boats employing gillnets and fish stakes are estimated to make an average of 26 trips per month, whereas trawlers and purse seiners could make an average of 20 trips per month. These data were used to derive estimates of mean by-catch per trip.

Analysis of factors affecting the reported incidence of by-catch of marine mammals was based on generalized linear models (GLM), fitted using Brodgar software (Highland Statistics Ltd.). The response variables were the presence (1) or absence (0) of by-catch of (a) all marine mammals, (b) cetaceans or (c) dugongs. Explanatory variables considered were interview year, region, fishing gear-type and boat-type, all nominal variables. The models were run assuming a binomial distribution for the response variable and using a logit link function. The initial models had the formula:

where Y1 is the occurrence of by-catch, α is the intercept, ɛi is the residual (unexplained information or noise, ɛi~N(0, σ2)).

Nominal explanatory variables were recoded as binomial dummy variables. In each case, the final (best-fit) model was identified by stepwise removal of non-significant terms until no further decrease in the Akaike information criterion (AIC) value was seen. The individual probability (P) value associated with each explanatory variable in the final model was used to identify significant effects on the occurrence of by-catch.

Confidence limits for numbers of by-catches were estimated using a bootstrap procedure. A purpose-written BASIC program was used to simulate the data collection procedure, repeatedly re-sampling with replacement from the set of N interviews in a stratum to generate multiple sets of N interviews. In the present application 10,000 repeats were used, each yielding an estimate of the number of by-caught animals in the stratum, raised to the level for the fleet. In each case, the 10,000 estimates were then sorted and the 251st and 9750th values represent the 95% confidence limits (i.e. only 5% of values are more extreme). Confidence limits were thus derived separately for each region and gear-type. Confidence limits were also derived for the total across all regions and/or all gear-types, by running versions of the program in which a series of strata was sampled, the total by-catch stored, and the procedure repeated 10,000 times.

Using another version of the bootstrap program and actual interview data for the fleets, expected confidence limits for the total number of animals caught annually were simulated for different numbers of interviews (10–500), including extrapolation to larger numbers of interviews than were actually carried out. We also estimated the number of observer trips needed to corroborate the interview findings on the by-catch rate.

Analysis of by-catch rates: observer data

Following López et al. (Reference López, Pierce, Santos, Gracia and Guerra2003), we estimated the 95% confidence limits of the underlying by-catch rate, and a retrospective power analysis was carried out to specify requirements for a long-term monitoring programme. Assuming that catching a single animal in a net can be modelled as a Poisson process, if λ is the mean by-catch per sampled unit of fishing effort and X is the number of by-catches, the probability of seeing r by-catches during a single sampling unit is given by:

Since the terms λr and r! are both equal to 1 for X = 0, the probability of observing at least one by-catch during N observed units of fishing activity is simply:

Based on a bootstrap re-sampling procedure and assuming a Poisson distribution, confidence limits for observed by-catch were estimated for a range of sample sizes and underlying by-catch rates. A similar approach was used to assess the number of observer trips needed to test if the by-catch rate exceeds the sustainable mortality limit for the population. We assume that an (annual) anthropogenic removal of more than 2% of the best available cetacean population estimate is an ‘unacceptable interaction’ (ASCOBANS, 1997). In the case of dugong by-catch, simulations by Marsh (Reference Marsh, O'Shea, Ackerman and Percival1995, Reference Marsh, Boyd, Lockyer, Marsh, Reynolds and Twiss1999) suggested that the maximum sustainable level of mortality may be as low as 2% of females annually.

RESULTS

Marine mammal sightings

Interview results indicated that the most commonly sighted cetaceans in Sabah were Irrawaddy dolphins and open water dolphins (Figure 2). Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins were also commonly reported in the north-eastern and eastern regions. All sightings of Irrawaddy dolphins and Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins were reported to occur in estuaries, bays or waters close to shore, and fishermen interviewed in the north-eastern and eastern regions said that the species often followed trawlers during fishing. The open water dolphins were said to come close to shore occasionally, but most sightings were reported to occur offshore or in deeper waters. In all regions, occasional sightings of finless porpoises, small whales and large whales were also reported. Many interviewees said that dugongs usually avoid humans and could be seen only when the animals were hunted or incidentally caught during fishing. Nevertheless, a few interviewees reported occasional sightings of dugongs at night, swimming slowly or grazing on sea grass in shallow areas.

Fig. 2. Summary of marine mammal sightings reported by fishermen in (a) western, (b) north-eastern, and (c) eastern regions, Sabah. The bar graph shows proportions of interview records reporting common (vertical stripes), occasional (dots) and no (unfilled bars) marine mammal sightings.

In all regions of Sarawak, Irrawaddy dolphins, open water dolphins and Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins were commonly reported, although the latter had the fewest records (Figure 3). Dolphins ere occasionally reported as following trawlers fishing in shallow waters. Occasional sightings of finless porpoises, small whales and large whales during fishing were also reported from all regions. Except in Limbang and Lawas (northern region) where a few fishermen reported occasional sightings of dugongs, many fishermen interviewed in other areas of Sarawak said that they had never seen a dugong. Nevertheless, two interviewees in Sematan (southern region) claimed that they had seen dugongs on a few occasions in waters near the Kalimantan (Indonesia) border.

Fig. 3. Summary of marine mammal sightings reported by fishermen in (a) southern, (b) central, and (c) northern regions, Sarawak. The bar graph shows proportions of interview records reporting common (vertical stripes), occasional (dots) and no (unfilled bars) marine mammal sightings.

Reports of by-catch from interviews

In all regions in Sabah, incidental catches of both dugongs and cetaceans were reported. Irrawaddy dolphins and open water dolphins were the most frequently reported cetacean species caught by boats employing gillnets. Several gillnet boats with cetacean by-catch also reported catching Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins and finless porpoises. All trawlers with cetacean by-catches reported catching Irrawaddy dolphins, although some also reported catching open water dolphins and Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins. Finless porpoises and open water dolphins were caught by boats employing fish stakes and purse seines, respectively. There were no reports of by-catch of small or large whales.

Although cetacean by-catches were reported from all regions in Sarawak, dugong by-catches were reported only from the northern region. As in Sabah, Irrawaddy dolphins were the most frequently reported cetacean species caught by boats employing gillnets in Sarawak. About half of the gillnet boats with cetacean by-catches reported catching open water dolphins, and a few reported catching Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins and finless porpoises. The majority of trawlers with cetacean by-catches reported catching Irrawaddy dolphins and open water dolphins, although some also reported catching Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins. The open water dolphins were the only cetacean group reported caught by purse seiners.

The majority of fishermen who reported by-catches of dugongs, open water dolphins and finless porpoises said they took the animals for family consumption and often shared the meat among neighbours, although some of them also said they traded or used the meat as shark bait. Almost all fishermen who reported by-catches of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins and Irrawaddy dolphins said they released/discarded the animals. There seems to be a general belief among fishermen that disturbing or harming these species will bring bad luck. Carcasses of incidentally caught dugongs, Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins, pantropical spotted dolphins and finless porpoises were recovered from a number of fishermen and fish traders during the survey period.

By-catch rates estimated from interview data

Of 753 boats sampled in Sabah, fishermen from 310 boats (41%) indicated the occurrence of incidental catches of marine mammals (Table 5): 188 boats (61%) caught dugongs, 41 (13%) caught cetaceans and 81 (26%) caught both. Cetaceans were reported to be caught in all gear-types, and dugongs in all gears except purse seine. Approximately 45 cetaceans and 69 dugongs were reported caught incidentally in fishing gears per year with an average catch of 0.06 cetaceans and 0.09 dugongs per boat (Table 4). Among regions, by-catches were highest in the north-east while, among gears, by-catches were highest in gillnets (Table 4). By raising the interview data to fleet level, an estimated 306 cetaceans (95% CI = 250, 369) and 479 dugongs (95% CI = 434, 528) were by-caught per year by the Sabah fishing fleet (Table 4).

Of 358 boats sampled in Sarawak, 99 (28%) indicated the occurrence of incidental catches of marine mammals (Table 5). In contrast to Sabah, 94 boats (95%) caught cetaceans, 3 (13%) caught dugongs and 2 (2%) caught both. Cetacean by-catch was reported from all regions, fishing gear-types and boat-types. Dugongs were not reported caught in purse seines or in the southern and central regions. Around 24 cetaceans and 2 dugongs were reported by-caught per year with an average catch of 0.07 cetaceans and 0.01 dugongs per boat (Table 5). Boats employing gillnets recorded the highest number of cetacean by-catches. Raising the figures to fleet level, around 221 cetaceans (95% CI =189, 258) were caught incidentally per year by the Sarawak fishing fleet (Table 5), over half from the southern region. Approximately 14 dugongs (95% CI = 2, 30) were caught incidentally per year by the northern region fishing fleet.

Generalized linear model analysis of data from Sabah confirmed the existence of significant effects of region, gear-type and boat-type on the overall reported incidence of marine mammal by-catch in Sabah (Table 6). Higher proportions of boats reported by-catches in the north-eastern and eastern regions, when gillnets were deployed, and if an outboard engine was fitted. There were no effects of interview year on the overall reported incidence of marine mammal by-catch. Considering cetacean and dugong by-catch separately, in both cases gear-type and boat-type had significant effects and higher proportions of boats reported by-catches when deploying gillnets and when using outboard-engines. Purse seiners reported no dugong by-catch. There was significant regional variation in dugong by-catch, with a higher incidence in the north-eastern and eastern regions than in the western region (Table 6).

Table 6. Results from binomial GLM for variation in the incidence of by-catch between different categories of boats in Sabah. The table lists all explanatory variables in the final models. Significant terms are indicated in bold face.

In analysing the Sarawak data set, interview year was not considered as one of the explanatory variables because there was collinearity between interview year and region. GLM results indicated that only region had significant effect on the overall reported incidence of marine mammal or cetacean by-catches in Sarawak. A higher proportion of boats in the southern region were reported to catch marine mammals or cetaceans, as compared to boats in the central and northern regions. There were no significant effects of gear-type and boat-type (Table 7). Dugong by-catch was not reported from purse seiners nor from the central and southern regions; therefore these data were excluded from GLM analysis. No significant effects of explanatory variables were detected in the remaining data set for dugong by-catch.

Table 7. Results from binomial GLM for variation in the incidence of by-catch between different categories of boats in Sarawak.

By-catch rates estimated from observer data

No marine mammal by-catch was seen during the 46 observed fishing trips in Sabah (5 in the western area, 16 north-eastern, 25 eastern). However, cetaceans (Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris), Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops aduncus), Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) and spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris)) were often sighted during the trips. Assuming the trips to have been representative, we can be 95% certain that the overall by-catch rate is less than 0.05, i.e. less than one occurrence per 20 trips.

Power analysis

The Sabah fishing fleet is estimated to make approximately 1.8 million fishing trips and incidentally catch around 306 cetaceans and 479 dugongs annually, i.e. around 0.17 cetacean and 0.27 dugong by-catches per 1000 trips, respectively. Treating results for each region separately and using the actual number of observed trips and estimated mean annual cetacean by-catch per trip for each region (Table 4), the probabilities of observing any cetacean by-catches during the observed fishing trips would have been 1–((1000–0.1)/1000)5 = 0.0005 in the western region, and 0.0034 and 0.005, in the north-eastern and eastern regions, respectively. The probabilities of observing any cetacean by-catches during the 36 trawl and 10 purse seine fishing trips observed in Sabah would have been 0.0014 and 0.0022, respectively. In the case of dugong by-catch, the probabilities of observing any by-catches during observed fishing trips would have been 0.0011, 0.005 and 0.0033 in the western, north-eastern and eastern regions, respectively. The probability of observing any dugong by-catches during the 36 trawl fishing trips observed would have been 0.00036.

The only available estimate of cetacean population size is in Philippines waters adjacent to the north-eastern region of Sabah. Dolar et al. (Reference Dolar, Yaptinchay, Jaaman, Santos, Muhamad, Perrin and Alava1997) estimated a population size of 3979 (CV = 0.59) spinner dolphins, 3455 (CV = 0.32) pantropical spotted dolphins and 415 (CV = 0.96) bottlenose dolphins in the Southern Sulu Sea. Assuming that dolphin by-catches reported in the north-eastern region are from the same population and that the maximum allowable anthropogenic removal is 2% of the population annually (ASCOBANS, 1997), there will be an upper limit of 80 spinner dolphins, 69 pantropical spotted dolphins, and 8 bottlenose dolphins, or a total of 157 dolphins caught annually. We estimated the total number of fishing trips in the north-eastern region to be around 880000 annually (see Table 4) hence the maximum acceptable by-catch corresponds to approximately 0.18 dolphins by-caught per 1000 trips. Results from simulated observer trips with underlying by-catch rates in the range 0.1 to 1 by-catch per 1000 trips indicate that around 10,000 observer trips would be needed to obtain accurate estimates of by-catch rates, and the precision of estimates increases markedly for up to around 15,000 trips (see Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Accuracy and precision of marine mammal by-catch estimates from observer trips in relation to number of simulated fishing trips observed. Median estimated marine mammal by-catch rate and 95% confidence limits, in relation to the number of observer trips, for (A) 0.1, (B) 0.5 and (C) 1 by-catch events per 1000 trips.

If the level of variability in reported catches in the actual interviews is realistic, precision and accuracy of by-catch estimates increase markedly for up to around 200 interviews per sector (i.e. dividing boats into categories according to region and gear-type) (see Figure 5). The results suggest that the numbers of interviews for boats employing gillnets was adequate, but that more data are needed for boats employing trawl nets, purse seines and fish stakes.

Fig. 5. Accuracy and precision of marine mammal by-catch estimates from interviews in relation to number of simulated interviews. Median estimated marine mammal by-catch and 95% confidence limits for four of the studied strata, for different numbers of interviews. The vertical lines indicate the actual number of interviews conducted. (A) Dugong by-catch in gillnets in western region, Sabah; (B) dolphin by-catch in trawl nets in north-eastern region, Sabah; (C) dolphin by-catch in purse seines in eastern region, Sabah; and (D) dolphin by-catch in gillnets in southern region, Sarawak.

DISCUSSION

Although there have been several studies focused on the effects of localized, inshore fisheries on cetaceans within south-east Asian waters (e.g. Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Smith, Crespo and Notarbartolo di Sciara2003; Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005), this study represents the first attempt to determine the nature and magnitude of by-catches of marine mammals and estimate the associated level of mortality in fisheries in East Malaysia.

The placement of observers on-board fishing boats is considered to be the most reliable method for collecting information regarding marine mammal by-catch (Tregenza et al., Reference Tregenza, Berrow, Hammond and Leaper1997; Morizur et al., Reference Morizur, Berrow, Tregenza, Couperus and Pouvreau1999; Silvani et al., Reference Silvani, Gazo and Aguilar1999; Tudela et al., Reference Tudela, Kai Kai, Maynou and El Andalossi2005), but such a monitoring programme is lacking in Malaysia. Even within the European Union, many governments of the Member States have not established routine monitoring of marine mammal catches and kills in fisheries (Morizur et al., Reference Morizur, Berrow, Tregenza, Couperus and Pouvreau1999; López et al., Reference López, Pierce, Santos, Gracia and Guerra2003), despite an obligation to do this under Article 12.4 of the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) and EC Council Regulation 812/2004. Furthermore, fishermen frequently refused to accept voluntarily the boarding of observers, especially in boats employing fishing gears that are known to catch cetaceans (Morizur et al., Reference Morizur, Berrow, Tregenza, Couperus and Pouvreau1999; López et al., Reference López, Pierce, Santos, Gracia and Guerra2003; Tudela et al., Reference Tudela, Kai Kai, Maynou and El Andalossi2005).

Given the nature of the fisheries in East Malaysia, which involve a large number of small fishing boats that employ a variety of fishing gears, obtaining an adequate sample of trips from this large fleet can be almost impossible. Given that fisheries in many parts of south-east Asia are often characterized as illegal, undocumented, and unregulated (IUU) (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005), it would probably take tremendous commitment and effort before any routine on-board observation or landing site monitoring schemes could be introduced. In this study, only a small number of fishing trips in Sabah were observed and none were accompanied in Sarawak. No marine mammal by-catch took place during any of the observed fishing trips onboard trawlers and purse seiners. Boats employing gillnets, fish stakes or other traditional gears were not sampled. Applying by-catch rates estimates from interviews we show that upwards of 10,000 trips would have to be monitored annually to get good by-catch estimates.

Evidently, the estimate of by-catch rate and the number of animals caught annually in this study is derived mainly from interviews. Lien et al. (Reference Lien, Stenson, Carver and Chardine1994) note that by-catch estimates derived from interviews of fishermen to estimate by-catch may contain unknown or uncontrolled errors and biases, especially if fishermen wish to conceal the occurrence of such mortality, and may be regarded as providing, at best, a rough guide to the scale of the problem. However, it seems unlikely that by-catch rates would be overestimated and therefore, as previously suggested by López et al. (Reference López, Pierce, Santos, Gracia and Guerra2003), interviews may indicate a minimum level of by-catch mortality.

In most of the interview sessions during the survey, at least an officer from relevant local authorities was present. However, most fishermen readily spoke about the occurrence of marine mammal by-catch and what they do with a by-caught animal. This is probably because it was the first time they were asked such questions and they had not experienced punishment from the authorities for catching cetaceans and/or dugongs, although the majority of them knew that catching marine mammals is illegal (S.A.J., unpublished data). This finding is also consistent with Dolar et al. (Reference Dolar, Leatherwood, Wood, Alava, Hill and Aragones1994, Reference Dolar, Yaptinchay, Jaaman, Santos, Muhamad, Perrin and Alava1997), Marsh et al. (Reference Marsh, Rathbun, O'Shea and Preen1995), Persoon et al. (Reference Persoon, de Iongh and Wenno1996) and López et al. (Reference López, Pierce, Santos, Gracia and Guerra2003) who reported the willingness of respondents in relaying information regarding marine mammal catches and utilization during their surveys. Clearly such willingness to provide information is likely to diminish if the provision of information is seen to be followed by imposition of restrictions on fishing activity.

Another potential source of bias in estimating and reporting rates of marine mammal by-catch, particularly in Sabah, is the fisheries statistics used. The Summary of Annual Fisheries Statistics Sabah 2002 (DFS, 2004) was based on listings made in 1998. The number of full-time fishermen is probably an underestimation; the number of illegal immigrants active in the industry has not been ascertained but could run into thousands (TRPDS, 1998). Many unlicensed boats and gears of the traditional types and part-time fishermen were observed during the survey and these do not appear in the official statistics. Underestimation of true fleet size would tend to lead to underestimation of total by-catch.

The present study suggests that at least four marine mammal species (D. dugon, O. brevirostris, S. chinensis and N. phocaenoides), and probably two others (Tursiops spp. and Stenella spp.) were by-caught in East Malaysian fisheries. Most of the reported by-catch in Sabah was dugongs, whereas cetaceans were the main by-catch in Sarawak. Given that dugongs were not reported to be caught in Sarawak (except in Limbang and Lawas) and many fishermen had never seen them, it is likely that the species' distribution on the west coast of Borneo is limited to Limbang and Lawas waters (and probably also Brunei waters). The coast of Sarawak is generally characterized by sandy shores as compared to the dominance of mangrove swamp, coral reefs, sea grass beds and coastal islands along the coast of Sabah, which offers habitats which are preferred by dugongs.

Finless porpoise sightings and by-catches were only occasionally reported. This suggests that its population, like that of the dugong, has greatly declined. Previously, the species was reported to be common in estuaries and coastal waters of Borneo (Weber, Reference Weber1923; Bank, Reference Bank1931; Medway, Reference Medway1977; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Francis and Phillips1985). Perrin et al. (Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005) stated that a factor to consider in present and future assessments is that low by-catch rates in many areas reflect the fact that cetacean and dugong populations have already been severely reduced by direct and incidental removals.

Dugongs and cetaceans in East Malaysian waters are particularly susceptible to gillnets. Trawl nets were reported to catch all species, except the finless porpoise, while purse seines were reported to catch open water dolphins occasionally. In Sabah, besides being reported to be caught in gillnets, dugongs and finless porpoises were also caught by fish stakes. Beside carcasses of incidentally caught dugongs, Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins, pantropical spotted dolphins and finless porpoises, a few hunted dugong and spinner dolphin carcasses were also recovered from fishermen and fish traders during the survey period. Although whales were occasionally sighted farther offshore, fishermen reported no by-catch of small or large whales in fishing gears. Thus, by virtue of their ecological habits, such as being close to shore, dugongs, Irrawaddy dolphins, Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins, and possibly also finless porpoises, are more susceptible to human impacts than other species, as previously suggested by Dolar et al. (Reference Dolar, Yaptinchay, Jaaman, Santos, Muhamad, Perrin and Alava1997).

Incidentally caught cetaceans, except the Indo-Pacific humpback and Irrawaddy dolphins, and dugongs are sometimes utilized for human consumption, and traded and used as shark bait, particularly in Sabah. The Bajau Pelauh and Bajau Laut people, who are common in the eastern and north-eastern regions, may take all catches, as they are known to have regarded marine mammals as a source of red meat and an important element in their tradition and culture for generations (Jaaman & Lah-Anyi, Reference Jaaman and Lah-Anyi2003; Jaaman, Reference Jaaman2004). Almost all fishermen interviewed in this survey claimed that the number of coastal cetaceans and dugongs has dropped significantly in the past few decades. The sighting of dugongs is rarely reported nowadays.

The Fisheries Act 1985, Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997 (Sabah) and Wild Life Protection Ordinance 1998 (Sarawak) protect all marine mammals from directed or incidental catches in fisheries. Generally, fishermen interviewed acknowledge these regulations, but many ignore the ban on taking marine mammals, especially in Sabah (S.A.J., unpublished data). In general marine conservation and management activities in East Malaysia appear to be under-resourced, with no by-catch reporting or monitoring schemes and poor enforcement of existing laws. When dolphin parts are confiscated in fish markets, often only a warning is issued (S.A.J., personal observation).

The magnitude of marine mammal by-catch is apparently greater in Sabah than in Sarawak, consistent with higher fishing effort in Sabah. Boats fishing in the Sulu Sea (north-eastern Sabah) and Celebes Sea (eastern) reported a higher number of incidences involving dugongs than boats fishing in the South China Sea (western). The magnitude of cetacean by-catch is apparently similar throughout Sabah. No cetacean or dugong by-catch was reported in several region-gear-type strata but under-recording is strongly suspected owing to the nature of fishing practices. Among the various fishing gears used in Sabah, gillnets appear to have the most detrimental effect on marine mammal populations, again at least in part because of the high level of fishing effort. Most gill-netters use outboard-powered boats and this category recorded a significantly higher number of incidences of by-catch than boats in the non-powered or inboard-powered categories. Fishermen using gillnets and outboard-powered boats in Sabah also reported a significantly greater magnitude of marine mammal hunting (S.A.J., unpublished data). Gillnets, which are relatively cheap, easy to operate, effective in catching high-valued fish species (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Donovan and Barlow1994) and widely used by fishermen in East Malaysia (DFS, 2004; DMFS, 2004), have been recognized as the main cause for cetacean and dugong by-catches worldwide (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Donovan and Barlow1994, Reference Perrin, Dolar and Alava1996, Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005; Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Penrose, Eros and Hugues2002).

As mentioned earlier, dugongs were reported seen and caught only in the northern waters of Sarawak South China Sea. Cetacean by-catches, however, were reported throughout the State, although more in the southern than in central and northern regions. However, the magnitude of cetacean by-catch is more similar between gillnets, trawl nets and purse seines, and between outboard- and inboard-powered boats.

The number of cetaceans or dugongs present in Malaysian waters has never been ascertained. However, the cetacean population is assumed to be small in numbers, as suggested for the populations in other countries in the south-east Asian region (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Dolar and Alava1996, Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005). For the dugong, substantial populations are known to exist in the coastal waters of tropical Australia, but throughout the remainder of the region its populations are believed to be fragmented and the numbers low and declining (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Penrose, Eros and Hugues2002; Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005).

The results of the present study show that dugongs in Sabah were more susceptible to fishing gears than cetaceans, as indicated by generally higher by-catch rates, most notably in gillnets. Gillnets are usually set in shallow areas with large tidal fluctuations and often on sea grass beds, to catch species such as rabbit fish (Siganus spp.) and threadfin bream (Nemipterus spp.) (S.A.J., personal observation) and these are also the areas preferred by dugongs. Poor visibility (at night or due to high turbidity) can increase the probability of dugong by-catch. Furthermore, many fishermen said that cetaceans are much cleverer than dugongs in detecting and avoiding fishing nets, but sometimes become entangled when actively chasing their prey. They also mentioned that cetaceans, like sharks, are strong ‘fish’ and, when caught in nets, the animals usually struggled violently and were more likely to free themselves, as compared to dugongs, which are often found dead. Dugongs were more commonly stranded than cetaceans between 1996 and 2001, and some animals may have died due to entanglement in fishing gears (S.A.J., unpublished data).

Dugongs were also reported to be caught by trawlers in the north-eastern region of Sabah and Lawas and Limbang in Sarawak. In these areas, the international (EEZ) boundaries are obviously close to shore, which makes the area for fishing relatively small. This may have forced trawling to take place in shallow waters and increased the chances for the dugongs and inshore cetaceans to be caught. It was evident during the survey that trawlers in the Sandakan, Darvel and Cowie Bays and Kinabatangan in Sabah were sometimes seen operating illegally in estuaries or waters close to shore.

The estimated annual numbers of cetacean and dugong by-catches for the various regions and gear types, particularly in gillnets, were high and may be unsustainable. Assuming that dolphin by-catches reported in the north-eastern region of Sabah are from the Philippines population (Dolar et al., Reference Dolar, Yaptinchay, Jaaman, Santos, Muhamad, Perrin and Alava1997) and applying the maximum 2% annual anthropogenic removal (ASCOBANS, 1997), dolphin by-catch in the area should not exceed 157 dolphins annually. The estimated annual number of 188 (95% CI = 112–282) dolphins caught incidentally in fisheries in the north-eastern region exceeds this figure and is in any case of similar magnitude. It should also be noted that dolphin populations, particularly the open water dolphins, subject to mortality by fisheries in Sabah are also subject to hunting (Jaaman & Lah-Anyi, Reference Jaaman and Lah-Anyi2003; Jaaman, Reference Jaaman2004), and directed and incidental catches in neighbouring Philippines waters (Dolar, Reference Dolar1994; Dolar et al., Reference Dolar, Leatherwood, Wood, Alava, Hill and Aragones1994, Reference Dolar, Yaptinchay, Jaaman, Santos, Muhamad, Perrin and Alava1997).

Even with the most optimistic combination of life-history parameters (e.g. low natural mortality and no human induced mortality) a dugong population is unlikely to increase more than 5% annually or 27.6% over five years (Marsh, Reference Marsh, O'Shea, Ackerman and Percival1995, Reference Marsh, Boyd, Lockyer, Marsh, Reynolds and Twiss1999). In East Malaysia, the lowest estimated number of dugong by-catches is in the northern region of Sarawak (14, 95% CI = 2–30). If half of this figure (7) is females, based on the maximum sustainable level of fishing mortality of 2% of females annually (Marsh, Reference Marsh, O'Shea, Ackerman and Percival1995, Reference Marsh, Boyd, Lockyer, Marsh, Reynolds and Twiss1999), at least 350 female dugongs would be needed in the region for the population to be maintained. This is unlikely because the population is probably shared with the other regions in Sabah where a higher magnitude of by-catch occurs. A similar suggestion has been made concerning the maintenance of dugong populations in Palau waters (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Rathbun, O'Shea and Preen1995) and in some other areas within the species' range (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Penrose, Eros and Hugues2002). Furthermore, dugongs were also reported as the main marine mammal species hunted in Sabah waters (Jaaman & Lah-Anyi, Reference Jaaman and Lah-Anyi2003; Jaaman, Reference Jaaman2004).

Conservation recommendations

There are three acts (i.e. Fisheries Act 1985, Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997 and Wild Life Protection Ordinance 1998) currently in place in East Malaysia to manage fisheries and protect marine mammals from directed or incidental catches. Generally, fishermen interviewed acknowledge these regulations, but many ignore the ban on taking marine mammals, especially in Sabah. There are several factors that may explain this, particularly poor enforcement of the relevant laws and the absence of reporting or monitoring by-catch.

Therefore, it is suggested that the management and enforcement authorities, fisheries organizations and community leaders should act promptly to establish a collaborative and dedicated programme to report or monitor marine mammal by-catch. Routine monitoring of fish markets and landing sites should be carried out, even if there is no observer monitoring of fishing trips. Enforcement of laws prohibiting direct takes or landing of incidental catches of marine mammals can increase the difficulty in obtaining information on such takes (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Dolar and Alava1996, Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005). Furthermore, enforcing law within a large area is often difficult and costly, thus it is essential to educate coastal communities towards compliance with fishing regulations and conserving their environment, and encourage their involvement in species monitoring.

There is currently no mitigation measure or area closure that is specifically established to reduce marine mammal by-catch in Malaysia. Since fishing is the main activity that provides food and generates income to the coastal communities, measures that significantly restrict it are unlikely to be successfully implemented (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Reeves, Dolar, Jefferson, Wang and Estacion2005). Nevertheless, several Marine Parks have been established, with the primary objective to conserve coral reefs and turtles, while allowing some traditional fishing and recreational activities to take place. These parks indirectly protect coastal marine mammal species and their habitats, such as dugongs and seagrass beds. Therefore, the establishment of more Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), at least in areas where marine mammals or their habitats are in serious conflict with humans, needs to be given serious consideration. MPAs should also be established with as much involvement by local people as possible and designed with features to maximize their social and economic benefits (Oakley et al., Reference Oakley, Pilcher, Wood and Sheppard2000; Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Smith, Crespo and Notarbartolo di Sciara2003). This will increase the likelihood that those affected by the MPA will comply with the regulations put in place.

Live marine mammals can be more valuable than some small-scale or traditional fisheries. In addition to the proposed MPAs, a carefully-planned, small-scale dolphin watching industry may help to stimulate further interest in conservation and increase awareness and could provide an alternative source of income to the fishermen. The Irrawaddy and Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins appear to be locally common in several locations. This is conducive to dolphin watching, but also means that dolphins may be susceptible to disturbance, especially from increased boat traffic. One way of compensating for disturbance is to use the dolphin watching industry to help accomplish research and management objectives (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Smith, Crespo and Notarbartolo di Sciara2003).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Surveys in Sabah and Sarawak were funded by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment Malaysia IRPA Grant No. 08-02-10-0010 ‘An integrated study of marine mammals and whale shark in the Malaysian Exclusive Economic Zone’, Universiti Malaysia Sabah and University of Aberdeen, UK. We extend our gratitude to the Department of Wildlife Sabah (especially to Edward Tangon, Francis Masangkim and Tawasil Butiting), Department of Fisheries Sabah (Abdul Hamid Mohamad, Abdul Rahman Othman, Albert Golud, Alip Mono, Chin Tet Foh, Haripudin Boro, Irman Isnain, Jalil Karim, Masrani Madun, Matusin Ali and Raden Kitchi), Sabah Parks (Fazrullah Rizally, Salimin and Selamat), Department of Fisheries F.T. Labuan (Adaha Hamdan), Department of Marine Fisheries Sarawak, Sarawak Forest Department (James Bali, Jeloo Sigit (deceased), Oswald B. Tisen, Rahas Bilang and Roslan Wahed), the Royal Malaysian Police, Royal Malaysian Navy, District Offices Sabah and Resident Offices Sarawak. A number of assistants (Ardiyante Ayadali, Cornel J. Miji, Ismail Tajul, Jennifer E. Sumpong, Josephine M. Regip, Mohamad Kasyfullah Zaini, Mukti Murad and Syuhaime A. Ali) helped with this work; we are grateful to them. Special thanks are due to many fishermen, village headmen and coastal villagers who have relayed to us precious information on cetaceans and dugong by-catches and exploitation. G.J.P. would like to acknowledge funding from the Commission of the European Communities (project ANIMATE, MEXC-CT-2006-042337). We also thank Begoña Santos and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments on the manuscript.