1. Introduction

The widespread implementation of early teaching and learning of FLs/L2s (second languages), particularly English, has possibly become ‘the world's biggest policy development in education’ (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Enever, Moon and Raman2009, p. 33). Historically, interest in early FL learning dates back to the late 1960s; since then, the development of FL programs for YLs has advanced globally in three noticeable waves (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Enever, Moon and Raman2009), all of which were followed by a subsequent loss of enthusiasm toward an early start due to discouraging results. Currently, we are experiencing the fourth wave characterized by three trends in the exponential spread of early FL programs. These trends include (1) an emphasis on assessment for accountability and quality assurance, (2) assessment not only of YLs in the first years of schooling but also of very young learners of pre-school age, and (3) an increase in content-based FL teaching, thus adding to the broad range of early FL programs.

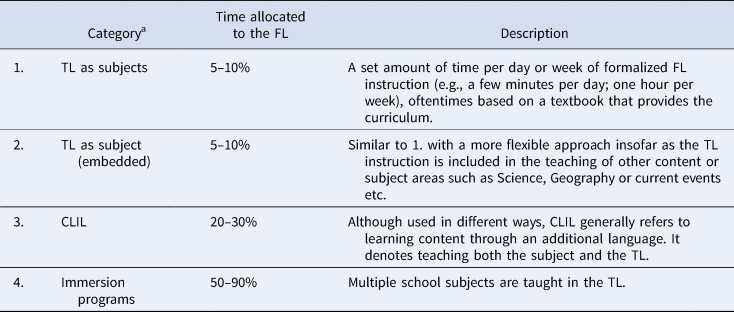

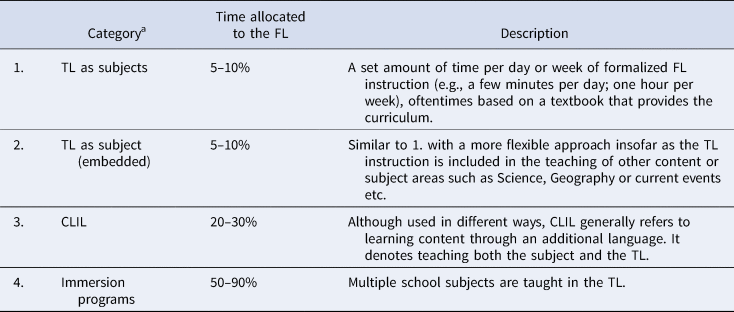

As shown in Table 1, early FL education programs vary substantially in their foci and amount of time allocated in the curriculum to learning the FL (Edelenbos, Johnstone, & Kubanek, Reference Edelenbos, Johnstone and Kubanek2006; Johnstone, Reference Johnstone and Johnstone2010). With regard to focus, the approaches to teaching FLs can be placed along a continuum between language and content (Inbar-Lourie & Shohamy, Reference Inbar-Lourie, Shohamy and Nikolov2009), ranging from (1) target language (TL) as subjects and (2) language and content-embedded approaches that aim to develop competence in the FL by borrowing topics from the curriculum (e.g., science, geography etc.) to (3) content and language integrated learning (CLIL), a popular term for content-based approaches (Cenoz, Genesee, & Gorter, Reference Cenoz, Genesee and Gorter2014) covering a wide range of practices, all the way to (4) immersion programs teaching multiple school subjects in the L2.Footnote 1 The time allocated to the TL in the four approaches gradually increases in line with the content focus from modest in the cases of (1) and (2), to significant in (3), and to substantial in (4) (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Enever, Moon and Raman2009, Reference Johnstone and Johnstone2010).

Table 1. Models of formal early FL education programs

Note: aThe labels and descriptions are partly adapted from Johnstone, Reference Johnstone and Johnstone2010, p. 16f.

Although in reality, the various programs and classrooms may be much more multifaceted, this broad categorization highlights two key aspects: (a) the diversity of the early FL education scene and (b) the variety of ‘language-related outcomes [that] are strongly dependent on the particular model of language education curriculum which is adopted’ (Edelenbos et al., Reference Edelenbos, Johnstone and Kubanek2006, p. 10). Hence, just as teaching and learning contexts vary substantially, so do the contents and goals of early FL learning.

Across this diverse landscape of early FL education programs and learning contexts, the fourth wave is characterized by an emphasis on assessment of YLs as part of a policy shift toward evidence-based instruction (e.g., Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2003). As a result, we have witnessed an increase in investigations—both in educational and social sciences (e.g., Haskins, Reference Haskins2018)—into how assessment in early language learning programs impacts children's overall development and their teachers’ work. Hence, the popularity of early FL programs, coupled with the emphasis of evidence-based instruction, has resulted in the ‘coming of age’ (Rixon, Reference Rixon and Nikolov2016) of YL assessment—a field as diverse as the early FL education landscape itself.

In this review, we explore the main trends in assessing YLs’ FL abilities over the past two decades, offering a critical overview of the most important publications. In particular, we offer insights into how and why the field of assessing YLs has evolved, how constructs have been defined and operationalized, what frameworks have been used, why YLs were assessed, what aspects of FL proficiency have been assessed and who was involved in the assessment, and how the results have been used. By mapping meaningful trends in the field, we want to indicate where more research is needed, thus outlining potential future directions for the field.

1.1 Criteria for choosing studies

We identified a body of relevant publications using a number of criteria for both inclusion and exclusion (Table 2). First, we followed Rixon and Prošić-Santovac's (Reference Rixon, Prošić-Santovac, Prošić-Santovac and Rixon2019, p. 1) definition of assessment as ‘principled ways of collecting and using evidence on the quality and quantity of people's learning’. Accordingly, our review includes a consideration of both summative and formative approaches to eliciting YLs’ knowledge and performances for the sake of informing classroom-based teaching and learning. Thus, this review encompasses research on formative assessment, including alternative assessments such as observations, self-assessment, peer assessment, and portfolio assessment, as well as studies on large-scale summative assessment projects and proficiency examinations.

Table 2. Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies

Second, in the larger area of YL assessment, the term ‘young learners’ is broadly used to denote students younger than those entering college, but young learners are far from being homogenous in terms of age and cognitive, emotional, social, and language development (McKay, Reference McKay2006; Hasselgreen & Caudwell, Reference Hasselgreen and Caudwell2016; Pinter, Reference Pinter2006/2017). In this review, we included publications in English on various TLs (not only English) that focused on YLs in pre-school (ISCED 0), lower-primary or primary (ISCED 1), and upper-primary or lower-secondary (ISCED 2; UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012) programs, ranging from age 3 to 14. Additionally, we focused on contexts where the TL is an FL, not an official language. Although we are aware that the status of a target language should be seen more like a continuum than a dichotomy of FL or L2, we excluded studies from our database that were conducted in L2 contexts, as well as those in language awareness and (bilingual) immersion programs. Hence, we reviewed studies conducted in FL contexts while taking into account the recent shift toward content-based instruction.

Third, as the body of research has substantially grown over the past two decades, we reviewed publications starting from the first discussions by Rea-Dickins and Rixon (Reference Rea-Dickins, Rixon, Clapham and Corson1997) and the seminal 2000 special issue of Language Testing. Our aim was to explore how the field has changed since then. We included relevant language policy documents, frameworks, and assessment projects published in a range of venues (Table 1) in order to analyze (1) how the assessment constructs have been defined, (2) what specific language proficiency models have been proposed and tested, (3) what principles test developers followed, and (4) how predictions and actual tests have been used, (5) how they have worked, and (6) how the results have been utilized.

Given these inclusion criteria and the primary focus on studies in which the proficiency of YLs in an FL is assessed, this review has a few limitations. For example, it does not discuss in detail phenomena that are related to early language learning. Accordingly, the review excludes the following aspects: (a) how children's attitudes toward their FL, their speakers and their cultures, and toward language learning in general are shaped, (b) how early learning of an FL evokes and maintains YLs’ language learning motivation, self-confidence, willingness to communicate, low anxiety, and growth mindset, or (c) other aspects of individual differences, including learner strategies and sociocultural background. It discusses, however, how these aspects have been found to impact YL's performance on assessments in studies which used them for triangulation purposes either to test models of early language learning or to complement qualitative data in mixed methods research. As will be seen, most studies have been conducted in European countries—an aspect that will be discussed in the future research section below.

2. The larger picture: What is the construct and how has it changed over time?

In this section, we focus on constructs and frameworks underlying the assessment of YLs’ FL abilities and trace how these have developed over time. In particular, we show how the field has gradually identified those language skills relevant for young FL learners, YLs’ potential linguistic goals and FL achievements, as well as (meta)cognitive and affective variables that impact FL development and assessment.

2.1 First steps in early FL assessment

Initial studies provided some insights into approaches taken to evaluate what YLs are able to do in the FL, thus revealing glimpses into the local contexts and underlying constructs that were assessed. Mainly conducted in the context of type (1) and (2) FL education programs designated in the Introduction, initial assessment studies included both summative and formative assessments.

From a summative perspective, early YL assessment studies used data obtained in the context of national assessments that were administered at the end of primary education in various countries (e.g., Edelenbos & Vinjé, Reference Edelenbos and Vinjé2000; Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2000; Zangl, Reference Zangl2000). For example, Edelenbos and Vinjé (Reference Edelenbos and Vinjé2000) analyzed data collected in a National Assessment Programme in Education that aimed at measuring YLs’ achievements in English as a foreign language (EFL) at the end of their primary education in the Netherlands. Assessments were administered in paper-and-pencil format (listening, reading, receptive word knowledge, use of a bilingual wordlist) and in individual face-to-face sessions with an interlocutor. The latter included a focus on speaking elicited through a discussion with English-speaking partners, pronunciation gauged by means of reading aloud sentences, and productive word knowledge tested by providing students with pictures that they had to label or describe. Edelenbos and Vinjé (Reference Edelenbos and Vinjé2000) found that overall students performed well in listening, but not in reading. In particular for reading, they noted better outcomes if teachers used a communicative approach instead of a grammar-oriented one, while the latter approach tended to result in higher scores in word knowledge. Results were mediated by learners’ socioeconomic backgrounds, the amount of EFL instruction, the types of teaching materials used, and in particular, the training and proficiency of EFL teachers.

Similar to Edelenbos and Vinjé (Reference Edelenbos and Vinjé2000), Johnstone (Reference Johnstone2000) described efforts with regard to the assessment of YLs’ French as an FL attainments in primary schools in Scotland. He emphasized diversity and variability in teaching contexts as the main challenge in the assessment of YLs’ proficiency. Therefore, early assessments for reading, listening, and writing administered in Scotland were developed locally at the different schools, while the research team designed content-free speaking tasks that were deployed across learning contexts. As ‘vessels into which pupils could pour whatever language they were able to’ (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2000, p. 134), the content-free speaking assessments included three types of data elicitations: (1) systematic classroom observations of student-teacher and student-student interactions, (2) vocabulary retrieval tasks that were based on free word association tasks in which children were asked to say ‘whatever words or phrases came into their head in relation to topics with which they were familiar’ (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2000, p. 135), and (3) paired speaking tasks administered in face-to-face sessions that mirrored classroom interactions familiar to the students. Especially the latter served as the main oral assessment to gauge YLs’ pronunciation, intonation, grammar control, and range of structures—all of which were rated on a three-point scale. In his conclusion, Johnstone (Reference Johnstone2000) highlighted the need to explore in more detail the construct of FL proficiency at the early age and promote formative assessments in primary FL education—areas that were further investigated by Zangl (Reference Zangl2000) and Hasselgreen (Reference Hasselgreen2000).

Exploring in more detail YLs’ FL competences, Zangl (Reference Zangl2000) introduced the assessments deployed in a FL education program in primary schools in Austria in which English was taught for 20 minutes three times per week. Children were assessed at the end of primary school by means of observations of classroom interactions (e.g., students’ group work, role-plays with puppets, and student-teacher interactions centered on certain topics such as holidays, favorite books, or hobbies), semi-structured interviews conducted with individual learners to gauge spontaneous speech, and oral tests that aimed to elicit specific structures in the areas of morphology, syntax, and lexis/semantics. Similar to Johnstone (Reference Johnstone2000), Zangl (Reference Zangl2000) wanted to obtain a comprehensive picture of learners’ English language proficiency in the areas of social language use and developing discourse strategies, in particular with regard to spontaneous speech, pragmatics (the use of language in discourse and context) and specific structures in morphosyntax and lexis. Conducting a multi-component analysis, Zangl highlighted specific aspects of YL's FL development, including its non-linear nature and the interconnectedness of the different language components. For example, she found that a learner may first produce the correct morphosyntactic form and a little later, may produce an incorrect form. Thus, it may seem that the learner regresses. However, Zangl referred to this phenomenon as ‘covert progression’ (p. 256), arguing that learners tend to initially memorize a correct form which may then vanish as they begin to produce language more actively and freely, thus applying rules and occasionally overgeneralizing them—a phenomenon commonly referred to as U-shaped development. With regard to interconnectedness of language phenomena, Zangl found that a student's increasing ability to form questions positively impacted their ability to take turns and to participate actively in student-teacher interactions. She highlighted that these insights into the development of learners’ L2 acquisition provide important pieces of information for test developers who should adapt assessment materials to students’ age, cognitive and linguistic abilities, their interests, and attention span in order to provide assessments that ‘reflect the learning process’ (p. 257; italics in the original).

In addition to summative national assessment projects, early investigations also explored formative approaches to assessing YLs (e.g., Gattullo, Reference Gattullo2000; Hasselgreen, Reference Hasselgreen2000). Hasselgreen (Reference Hasselgreen2000), for example, described an assessment battery developed for primary-level classrooms in Norway—a context in which the curriculum was underspecified in terms of content and outcomes of early EFL education. As a first step, Hasselgreen conducted a survey with 19 teachers in Bergen, thus identifying four components of communicative language ability taught in early EFL education: (1) vocabulary, morphology, syntax, and phonology, (2) textual ability (e.g., cohesion), (3) pragmatics (i.e., how language is used in TL contexts), and (4) strategic ability (i.e., how to cope with communicative breakdown and difficulties in communication). Based on these four areas, she then developed an assessment battery with tests for reading, listening, speaking, and writing. Each test included integrated tasks that featured topics, situations, and texts YLs were believed to be familiar with through classroom activity. For instance, reading was assessed by means of matching tasks with pictures, true-false choice tasks, and gap-filling activities. During the listening test, students would listen to a mystery radio play and were asked to identify specific aspects in pictures (listen for detail). The writing test would then build on the mystery play with students being asked to write a diary entry or response letter to a character in the play. Finally, the speaking assessment was administered in pairs with picture-based prompts. Additionally, classroom-based observations were added to provide further insights about the learners’ speaking skills. Thus, Hasselgreen was among the first to develop systematically an initial assessment battery that was supposed to be used regularly in EFL classrooms in order to promote metalinguistic awareness and assessment literacy among EFL teachers and YLs.

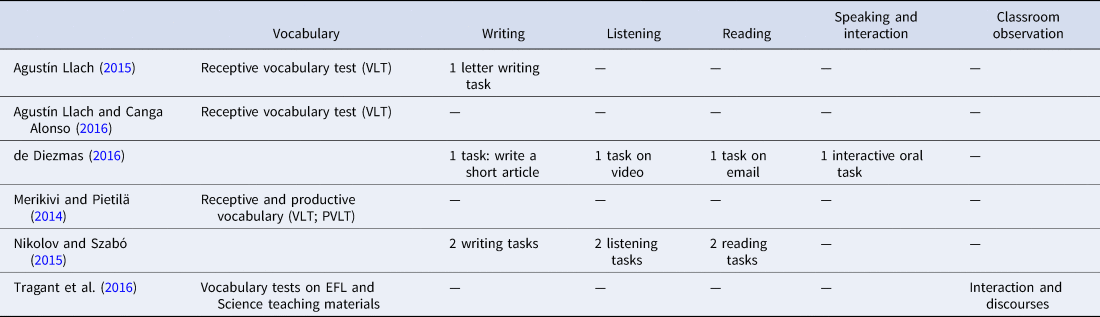

To summarize, early, largely descriptive accounts of summative and formative approaches to YL assessment provide insights into the diversity of early FL teaching contexts. In particular, they reveal the lack of a consensus with regards to what proficiency in the FL means for YLs and how the putative language abilities were supposed to be assessed. That is, the construct definition of what was assessed varied widely across contexts and included to various degrees the four macro-skills as well as different components of the language system such as lexis/semantics, grammar, pragmatics, intonation, cohesion and/or pronunciation (see Table 3 for an overview)—features that are strongly reminiscent of constructs proposed in the context of adult L2 learning and assessment. Additionally, many assessments used at this early stage were still based on rather traditional, paper-and-pencil formats such as multiple-choice items (Edelenbos & Vinjé, Reference Edelenbos and Vinjé2000).

Table 3. Language components in early assessment studies aiming to measure young learners’ FL abilities

However, despite the large diversity and at times traditional approaches to FL assessment, certain trends appeared to develop that emphasized the particular needs and individual differences of YLs. For example, all early assessment studies focused on speaking and interaction, thus accounting for the oral dimension of early FL learning. Moreover, most of the studies administered assessments in contexts that are familiar to YLs. Interviews or paired speaking assessments (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2000; Zangl, Reference Zangl2000) were carried out in settings that were meant to resemble familiar face-to-face classroom interactions, while several assessments even highlighted the use of classroom observations as a means of gauging insights into how YLs could use the FL in context and interaction. Also, administrators deployed integrated tasks based on materials that were regarded age-appropriate, familiar, and engaging to YLs, primarily using visual and tactile stimuli (Hasselgreen, Reference Hasselgreen2000). Finally, in all early assessment studies, researchers have highlighted the need to gain a detailed understanding of YLs’ FL development and proficiency in order to inform the design and construct underlying YL assessments—a call that was pursued in more depth in assessment-oriented research in the early 2000s.

2.2 Learning to walk: The evolution of frameworks for early FL assessment

While the first approaches to YL assessment largely prioritized ‘fun and ease’ in terms of providing anxiety-free, positive testing experiences (Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2016a, p. 4; italic in the original), the field soon faced a call for more accountability and thus the need to determine realistic, age-appropriate achievement targets (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Enever, Moon and Raman2009; Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2016a). As a result, researchers began to put forth principles, models, and frameworks intended to guide YL FL teaching and assessment (e.g., Cameron, Reference Cameron2003; McKay, Reference McKay2006). Among the first, Cameron (Reference Cameron2003, p. 109) proposed a multidimensional ‘model of the construct “language” for child foreign language learning’ that is aligned with children's first language (L1) acquisition and based on three fundamental principles that focus on: (a) meaning, (b) oral communication, and (c) development that is sensitive to children's emerging L1 literacy. Rooted in these principles, this framework distinguished between ‘oral’ and ‘written’ language, identifying in particular vocabulary (i.e., the comprehension and production of single words, phrases, and chunks) and discourse (i.e., understanding, recalling, and producing ‘extended stretches of talk’ including songs, rhymes, and stories) as key dimensions of oral and meaning-oriented language use (Cameron, Reference Cameron2003, p. 109). Discourse is further subdivided into conversation and extended talk as means of using the FL in communicative interaction. Grammar is argued to constitute more of an implicit element in YL instruction insofar as it is needed to develop a sense for patterns underlying the FL. Cameron (Reference Cameron2003) argued that teaching and assessment need to foreground meaning-oriented, oral communication—a step forward if we consider the relatively strong emphasis on grammar in the early YL FL assessments (see Table 3).

Building on principles included in Cameron (Reference Cameron2003)and Nikolov (Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2016a), in the context of developing a diagnostic assessment for YLs in Hungary, proposed a framework that provides a more comprehensive picture of how primary-level learners develop their EFL proficiency. In contrast to earlier frameworks that primarily drew upon insights from L1 acquisition, development of ESL learners’ academic language proficiency, and adult L2 ability, Nikolov also included findings from longitudinal projects in second language acquisition that investigated YLs FL development over a period of time relative to factors such as age (García Mayo & García Lecumberri, Reference García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003; Muñoz, Reference Muñoz, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003, Reference Muñoz2006), cognitive and socioaffective development (e.g., Mihaljević Djigunović, Reference Mihaljević Djigunović, Nikolov and Horváth2006; Kiss, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2009), learning strategies (e.g., Csapó & Nikolov, Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009), and the quality of FL instruction (e.g., Nikolov & Curtain, Reference Nikolov and Curtain2000). Based upon that research, she put forth the following high-level principles:

• The younger learners are, the more similar their FL development is to their L1 acquisition.

• Children tend to learn implicitly, based on memory, and only gradually develop the ability to rely on rule-based, explicit learning strategies, which becomes more prominent in their approach to learning around puberty.

• Children develop fairly similarly in terms of aural and oral skills (see Cummins, Reference Cummins2000), while more individual differences, related to YLs’ L1 abilities, aptitude, cognitive abilities, and parents’ socioeconomic status, can be found in their literacy development.

• Learning and assessment should (a) focus on children's aural and oral skills (i.e., listening comprehension and speaking abilities), while ‘reading comprehension and writing should be introduced gradually when they are ready for them’ (Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2016b, p. 75) and (b) always build upon what YLs know and can do in terms of their world knowledge, comprehension, and L1 abilities, thus promoting a positive attitude toward FL learning.

• Learning and assessment tasks need to be age-appropriate insofar as they recycle familiar language while offering opportunities to learn in a way that is ‘intrinsically motivating and cognitively challenging’ (Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2016b, p. 71).

Discussing each principle in detail, Nikolov highlighted that overall ‘achievement targets in [YLs’] L2 tend to be modest’ (Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2016a, p. 7) as children move from unanalyzed chunks to more analyzed language use (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone, Enever, Moon and Raman2009). Moreover, she captured the diversity with regard to FL educational contexts, learners’ individual differences, and developmental paths (for overviews, see Nikolov & Mihaljević Djigunović, Reference Nikolov and Mihaljević Djigunović2006, Reference Nikolov and Mihaljević Djigunović2011)—aspects that need to be considered in order to align assessment constructs and outcome expectations with specific learner groups in the given local educational contexts.

In addition to frameworks and principles, there was a need, in particular for national and international assessments, to provide accounts of quantifiable targets that describe in detail what children are expected to do at certain stages in their FL development. This need resulted in studies, mostly across Europe, that adapted the language descriptors included in the English Language Portfolio (ELP) and Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) for young learners of FLs (e.g., Hasselgreen, Reference Hasselgreen2003, Reference Hasselgreen2005; Curtain, Reference Curtain and Nikolov2009; Papp & Salamoura, Reference Papp and Salamoura2009; Pižorn, Reference Pižorn, Figueras and Noijons2009; Baron & Papageorgiou, Reference Baron and Papageorgiou2014; Benigno & de Jong, Reference Benigno, de Jong and Nikolov2016; Papp & Walczak, Reference Papp, Walczak and Nikolov2016; Szabo, Reference Szabó2018a,Reference Szabób). Benigno and de Jong (Reference Benigno, de Jong and Nikolov2016), for example, described the first phase of a multiyear project to develop a ‘CEFR-based descriptor set targeting young learners’ (p. 60) between 6 and 14 years of age. After identifying 120 learning objectives for reading, listening, speaking, and writing from English language teaching textbooks, curricula, and the ELP, they assigned proficiency level ratings to the objectives in standard-setting exercises with teachers, expert raters, and psychometricians who calibrated and scaled the objectives relative to the CEFR descriptors. Although Benigno and de Jong argued that they were able to adapt the CEFR descriptors from below A1 to B2 for YLs and align them with Pearson's continuous Global Scale of English, it remains unclear how key variables such as age, learning contexts, developing cognitive skills and L1 literacy, and empirical data on YLs’ test results feature into the rather generic descriptors (for the complete set of descriptors, see https://online.flippingbook.com/view/872842/).

In an attempt to account for individual differences with regard to social and cognitive development and provide a reference document for YL educators, Szabo (Reference Szabó2018a,Reference Szabób) presented a collation of CEFR descriptors of language competences for YLs between 7 and 10 as well as 11 and 15 years, respectively. She iteratively reviewed ELPs for YLs from 15 European countries and mapped the self-assessment statements to the CEFR descriptors, while rating the CEFR descriptors and the ELP can do statement with regard to perceived relevance for primary-level learners. For the age range of 7–11-year-old learners, for instance, she included CEFR levels ranging from pre-A1 to B2 across all language skills (C1 and C2 levels were excluded due to their limited relevance to the age group), thus outlining can do descriptors for reception, production, interaction, and mediation abilities in an effort to provide ‘the basis of language examination benchmarking to the CEFR’ (Szabo, Reference Szabó2018a, p. 10). Although a very thorough attempt to establish a potential benchmark, Szabo acknowledged a ‘“bias for best” approach’ (p. 15) with regards to the hypothetical learning context. In other words, whether or to what extent the B2 level can do descriptors constitute a realistic achievement target for primary-level FL education is questionable.

To summarize, the field of young learner assessment has put forth frameworks aimed at defining in more detail a construct of language for child FL learning to account for achievement targets both at local and more global levels. The framework descriptions proposed primarily in Europe (Cameron, Reference Cameron2003; Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2016a) and the United States (see e.g., Curtain, Reference Curtain and Nikolov2009) tend to foreground aural and oral FL abilities as opposed to language knowledge (e.g., grammar), while highlighting children's developing social, emotional, cognitive, and literacy skills. Additionally, more globally oriented frameworks such as the CEFR collation suggest a somewhat wider construct by including listening, speaking, writing, reading, and interaction skills ranging from pre-A1 to B2—skills that would also be mediated by differences in developing cognitive, literacy, affective, and socioeconomic aspects.

2.3 On firmer empirical footing: Investigating frameworks and variables of early FL education

To explore the considerable variation in achievements of young FL learners from similar backgrounds in similar learning contexts, researchers have increasingly focused on aspects related to YLs’ FL development such as cognitive, affective, and sociocultural variables. In particular, assessment studies have focused on aptitude and cognition (Kiss & Nikolov, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2005; Alexiou, Reference Alexiou and Nikolov2009; Kiss, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2009), affect, motivation, anxiety, and learning difficulties (Mihaljević Djigunović, Reference Mihaljević Djigunović and Nikolov2016; Kormos, Reference Kormos2017; Pfenninger & Singleton, Reference Pfenninger and Singleton2017), socioeconomic background (Bacsa & Csíkos, Reference Bacsa, Csíkos and Nikolov2016; Butler & Le, Reference Butler and Le2018; Butler, Sayer, & Huang, Reference Butler, Sayer and Huang2018; Nikolov & Csapó, Reference Nikolov and Csapó2018), learning strategies, emerging L1 and L2 literacy skills and how learners’ languages interact in order to explore what it means for children to learn additional languages and how these factors impact L2 assessment.

As a learner characteristic that is considered responsible for much of the variation in FL achievements, aptitude for language learning is generally viewed as a predisposition or natural ability to acquire additional languages in a fast and easy manner (Kiss & Nikolov, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2005; Kiss, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2009). While aptitude is relatively well researched in adult L2 learners, Kiss and Nikolov (Reference Kiss and Nikolov2005) were among the first to report on the development and psychometric performance of an aptitude test for YLs (specifically, 12-year-old L1 Hungarian learners of English). Based on earlier models and aptitude tests for adult L2 learners, they conceptualized aptitude as consisting of four traits. Accordingly, they included four tests in their larger aptitude test battery for YLs (Kiss & Nikolov, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2005, p. 120):

1. Hidden sounds: Associating sounds with written symbols

2. Words in sentences: Identifying semantic and syntactic functions

3. Language analysis: Recognizing structural patterns

4. Vocabulary learning: Memorizing lexical items (short-term memory).

They administered the aptitude test battery, an English language proficiency test with listening, reading, and writing sections based on the local curriculum, and a motivation questionnaire to 398 sixth graders from ten elementary schools in Hungary. Although they could not account for the children's oral abilities in English, Kiss and Nikolov found that the aptitude test exhibited evidence of construct validity with results indicating four relatively independent abilities that all showed strong relationships with students’ performance on the English proficiency measure. Overall, aptitude scores explained 22% and motivation explained 8% of variation in the English scores.

To help a primary school select children for a new dual-language teaching program, Kiss (Reference Kiss and Nikolov2009) administered a slightly adapted version of the same aptitude test to 92 eight-year-old Hungarian students in second grade. Additionally, students completed a five-minute oral interview and engaged in an oral spot-the difference task. Kiss was able to confirm the good performance of the aptitude test insofar as the test identified students with the higher FL oral performance. Additionally, she found short-term working memory ability to be quite distinct from other traits. Also, when comparing the results with the 8-year-olds in the earlier study (Kiss & Nikolov, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2005), she found that the 12-year-olds performed much better. She speculated that this was most likely because at about eight years of age, children did not have exposure to vocabulary memorization and thus, had not developed memorization strategies yet.

Additionally, studies began to investigate aptitude relative to specific language skills such as YLs’ vocabulary development in the FL (Alexiou, Reference Alexiou and Nikolov2009) and listening comprehension (Bacsa & Csíkos, Reference Bacsa, Csíkos and Nikolov2016). Alexiou (Reference Alexiou and Nikolov2009) investigated YLs’ aptitude and vocabulary development in English with five–nine-year-old L1 Greek students (n = 191). Using non-language measures as some of her test takers were not yet literate, Alexiou administered an aptitude measure consisting of memory and analytic tasks as well as receptive and productive vocabulary tests that featured words selected from the learners’ academic curriculum. She found rather moderate, yet statistically significant relationships between YLs aptitude and vocabulary development in English, hypothesizing that at the beginning YLs favor phonological vocabulary and only later does the orthographic recognition exceed phonological learning. Unfortunately, Alexiou's analysis did not account for differences in age. However, she still argued that aptitude appears to progress with age as cognitive skills evolved and potentially reached its peak when children become cognitively mature—a hypothesis that was further examined by Bacsa and Csíkos (Reference Bacsa, Csíkos and Nikolov2016).

Over the course of six months, Bacsa and Csíkos (Reference Bacsa, Csíkos and Nikolov2016) investigated the listening comprehension and aptitude of 150 fifth and sixth graders (age 11–12 years) in ten school classes in Hungary. After training teachers on how to add diagnostic listening tests to their current syllabi, they administered listening assessments at the beginning and end of the six-month period as pre- and posttests. In addition, Kiss and Nikolov's (Reference Kiss and Nikolov2005) aptitude test and questionnaires on motivation and anxiety were administered. Deploying correlations, regression analysis, cluster analysis, and path analysis, they focused their analysis on six variables, including parents’ education (or socioeconomic background), aptitude, language learning strategies, beliefs, attitudes, motivation, and anxiety. They found students’ achievements in both grades to be considerably higher on the posttest. The largest percentage of variation in children's listening comprehension was explained by YLs’ aptitude and parents’ education (28.3% and 4.4%, respectively). Additionally, learners’ beliefs about difficulties in language learning (6.8%), anxiety about unknown words (3.2%), and difficulty of comprehension (5.7%) in listening tests also contributed to their listening scores. Overall, cognitive factors explained more of the variation in YLs’ FL achievement than affective factors. Affective factors, however, changed consistently and seemed to depend upon the language learning context.

Similar findings were reported by Kormos (Reference Kormos2017) who critically reviewed research at the intersection of L1 and L2 development, cognitive and affective factors, and YLs’ specific learning difficulties (SLDs). With a particular focus on reading, she highlights that among the factors impacting YLs’ reading abilities are processing speed, working memory capacity (storage and processing capacity in short-term memory), attention control, and ability to infer meaning. Identifying these as ‘universal factors that influence the development of language and literacy skills in monolingual and multilingual children’ (Kormos, Reference Kormos2017, p. 32), Kormos specifically pinpoints phonemic awareness and rapid automated naming as those phonological processing skills that play a key role in decoding and encoding processes across languages and that may create particular issues for YLs with SLDs. Nevertheless, Kormos advocates for the assessment of the FL abilities of YLs with and without SLDs, emphasizing in particular the need to develop appropriate assessments to explore how motivational, affective and cognitive factors, instructional environment, and personal contexts impact the literacy development of all students.

In sum, aptitude appears to be a significant predictor of FL achievements (Kiss & Nikolov, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2005; Kiss, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2009), with cognitive variables explaining a large portion of the variation in YLs’ achievements (Csapó & Nikolov, Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009; Bacsa & Csíkos, Reference Bacsa, Csíkos and Nikolov2016). Additionally, affective variables such as motivation and the perception of the learning environment which have only been examined indirectly in many studies (e.g., Kiss & Nikolov, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2005; Bacsa & Csíkos, Reference Bacsa, Csíkos and Nikolov2016; Kiss & Nikolov, Reference Kiss and Nikolov2005) have been identified as predictors of YLs’ FL achievement. For example, over seven months, Sun, Steinkrauss, Wieling, and de Bot (Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Wieling and de Bot2018) assessed the development of English and Chinese vocabulary of 31 young Chinese EFL learners (age 3.2–6.2). Additionally, aptitude was assessed together with internal and external variables. Participants’ vocabulary was tested by four tests: the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test and the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test, the depth of vocabulary by semantic fluency and word description tests both in English and in Chinese (translated versions) before and after the English program. Two aptitude measures tapped into the children's phonological short-term memory and non-verbal intelligence. The study reported stronger effects of external factors (e.g., exposure to English at school and at home) than aptitude, thus pointing to stronger effects of external factors over aptitude when it comes to Chinese YLs in an EFL context.

Overall, longitudinal research with larger samples would be desirable in order to gauge causal relationships and to account for the relative impact of these variables on language learning. While these variables constitute key factors in determining YLs’ FL learning, they are not necessarily stable characteristics. Rather, they seem to change and evolve over time as children mature cognitively, become literate in their L1 and additional languages, and gather experiences related to formal language learning. Moreover, they are impacted by parents, teachers, and peers, for example, and their roles and impact change as YLs age (for an overview see Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, Reference Mihaljević Djigunović, Nikolov, Lamb, Csizér, Henry and Ryan2019). Future research should focus on how memory-based learning, more typical of younger learners, shifts toward more rule-based learning. One would expect memory to be a better predictor of L2 learning for younger children than inductive or deductive abilities—a hypothesis which, if proven, could provide valuable information for the design and administration of assessments aimed to measure YLs’ FL abilities.

3. Assessment of learning

Summative assessment, also referred to as assessment of learning, serves the purpose of obtaining information regarding YLs’ achievements at the end of a teaching or learning process (e.g., a task, a unit, a program etc.). In summative assessment, the aim is to measure to what extent YLs have mastered what they were taught, or in the case of proficiency tests, to what extent students have achieved the targets in the FL along certain criteria. Research reviewed in this section—including national assessment projects, validation projects, and examinations contrasting different types of learning contexts—pertains to this larger paradigm of assessment of learning.

Most of the reviewed studies were motivated by changes in policies regarding language learning and subsequent accountability needs, on the one hand, as well as researchers’ interests in various aspects of early language learning, on the other. Quality assurance and accountability typically underlie national assessment projects and validation studies, as decision-makers want to know student learning outcomes relative to curricular goals or how YLs in programs starting earlier and later as well as FL and CLIL programs compare to one another. Additionally, validation projects aim to find evidence on how effective traditional and more innovative types of (large-scale) tests are for assessing YLs’ language skills, thus also accounting for the quality of assessments. Finally, other projects—oftentimes small-scale experimental studies—reflect researchers’ interests in various aspects of early language learning.

3.1 YLs’ performance on large-scale national assessment projects

Over the past decade, as early FL programs have become the norm rather than the exception in many countries, attainment targets have been defined and national assessments have been implemented (Rixon, Reference Rixon2013, Reference Rixon and Nikolov2016). A recent publication by the European Commission (2017, pp. 121–128) offers insights into the larger picture in 37 countries along three characteristics of national curricula and assessments: (1) which of the four language skills are given priority, (2) what minimum levels of attainment are set for students’ first and second FLs, and (3) what language proficiency levels the examinations target. Curricula in ten countries give priority to listening and speaking, and in two of these reading is also included. All four language skills are emphasized in 20 countries, whereas no specific skill was specified in 7 countries. Over half of the countries offer a second FL (L3) in lower secondary schools, yet no information is shared on L3 examinations. Overall though, attainment targets tend to be at a lower level than in the first FL. Out of 37 countries included in the survey, 19 European countries reported a national assessment for YLs in their first FL and defined expected learning outcomes along the CEFR levels. The levels specified in the examinations for YLs ranged between A1 and B1; A2 is targeted in six, whereas three levels (A1, A2, B1) are listed in another six countries; B1 is targeted in 13 countries at the end of lower secondary education. There is no data on how many YLs achieve these levels, nor are any diagnostic insights provided relative to YLs’ strengths and weaknesses.

Two examples that report national assessment projects provide additional details into YLs’ development: one in a European (Csapó & Nikolov, Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009; Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2009) and another one in an African context (Hsieh, Ionescu, & Ho, Reference Hsieh, Ionescu and Ho2017). In Hungary, YLs’ proficiency was assessed on nationally representative samples of about ten thousand participants in years 6 and 8 in 2000 and in 2002 to measure their levels of FL proficiency, analyze how their language skills changed after two years, and what roles individual differences and variables of provision (number of weekly classes and years of FL learning) played. A larger sample learned English and a smaller one learned German. YLs’ listening, reading, and writing skills in the L2 and reading in L1, as well as their inductive reasoning were assessed, and their attitudes and goals were surveyed (Csapó & Nikolov, Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009). The research project was followed by a national assessment using the same test specifications in 2003 (Nikolov, Reference Nikolov and Nikolov2009). At all three data points, English learners’ achievements were significantly higher across all skills than their peers’ scores in German. YLs of English were more motivated, set higher goals in terms of what examination they aimed to take, and their grades in other school subjects were also higher than those of German learners. The relationships between proficiency and number of years of learning English or German were weak in both languages. Based on the datasets from the first two years, students’ test scores in year 6 were the best predictor of L2 skills in year 8 (Csapó & Nikolov, Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009). Additionally, relationships between L2 and L1 reading weakened and between L2 skills strengthened over the years.

In Kenya, the English proficiency of 4,768 YLs who spoke 8 different L1s was assessed in years 3–7 (Hsieh et al., Reference Hsieh, Ionescu and Ho2017). Researchers administered the TOEFL Primary Reading and Listening test—a large-scale standardized English language assessment for children between 8 and 11 years of age—in 51 schools to find out if students were ready to start learning school subjects in English. Students obtained higher scores across school grades; however, scores varied considerably by region. In year 7, about two thirds of YLs were at A2 level of proficiency, and very few achieved B1 level, the threshold assumed to be necessary for English-medium instruction.

3.2 Test validation projects

Test validation is a key component of quality assurance in test development. Validation studies provide crucial evidence as to whether an assessment measures what it is intended to measure and whether test scores are interpreted properly relative to the intended test uses (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014). Compared to the number of assessment projects pertaining to YLs, relatively few publications focus on validation (e.g., for a discussion of validating national assessments, see Pižorn & Moe, Reference Pižorn and Moe2012). The majority of validation projects have been conducted in the context of international, large-scale assessments as a means of ensuring test quality. By contrast, the field has seen relatively few validation projects on locally administered, small-scale assessments. Among the limited validation research on small-scale assessments are studies of locally administered speaking assessments and C-tests.

3.2.1 International proficiency examinations for YLs

Most of the validation work on tests for YLs has been carried out in the context of large-scale, standardized English language proficiency assessments (e.g., Bailey, Reference Bailey2005; Wolf & Butler, Reference Wolf and Butler2017; Papp, Rixon & Field, Reference Papp, Rixon and Field2018). Examples of these assessments offered primarily by testing companies such as Educational Testing Service, Cambridge Assessment English, Pearson, and Michigan English Assessment, include the TOEFL® Young Student Series, the Cambridge Young Learners English Tests, PTE Young Learners, as well as the Michigan Young Learners English tests. These assessments have been supported to varying degrees by empirical research, in particular with regard to the validity of the test scores.

In the context of international proficiency tests, a popular way to support the validity of test scores is the argument-based approach to validation (Chapelle, Reference Chapelle, Chapelle, Enright and Jamieson2008; Kane, Reference Kane2011). The main objective of an argument-based approach to validation is to provide empirical support for claims about qualities of test scores and their intended uses. For example, a test developer may claim that test scores are consistent or reliable. To provide support for claims, a series of statements (or warrants) is put forth which then need to be backed up by theoretical and/or empirical evidence such as, for example, reliability estimates. In contrast to warrants, rebuttals constitute alternative hypotheses that challenge claims. Hence, research produces evidence that may either support claims about an assessment or undermine them (i.e., supporting rebuttals).

One of the most comprehensive applications of an argument-based approach to validation in the context of a large-scale proficiency test for YLs is the empirical validity evidence gathered for the assessments in the TOEFL® Young Student Series (YSS). Following Chapelle (Reference Chapelle, Chapelle, Enright and Jamieson2008), the interpretive argument approach was applied from the outset, driving test development as well as the subsequent research agenda. In the test design frameworks for the TOEFL Junior test and the TOEFL Primary tests, So et al. (Reference So, Wolf, Hauck, Mollaun, Rybinski, Tumposky and Wang2015) and Cho et al. (Reference Cho, Ginsburgh, Morgan, Moulder, Xi and Hauck2016) specified the intended populations and uses of the test. They discussed in detail the test design considerations, the TL use domains, skills, and the knowledge components that are assessed and how these components are operationalized for the purpose of YL assessment. Additionally, the frameworks laid out the inferences, warrants, and types of research needed to provide empirical evidence for validating the different uses of the TOEFL YSS assessments (for a detailed overview, see So et al., Reference So, Wolf, Hauck, Mollaun, Rybinski, Tumposky and Wang2015, p. 22). Over the years, research has been conducted for these assessments in order to support the validity of test scores and their uses. For instance, in the context of the TOEFL Primary tests, studies have investigated content representativeness of the tests (Hsieh, Reference Hsieh and Nikolov2016), YLs’ perceptions of critical components of the assessment (Cho & So, Reference Cho and So2014; Getman, Cho, & Luce, Reference Getman, Cho and Luce2016), YLs’ test-taking strategies (Gu & So, Reference Gu, So, Wolf and Butler2017), the relationship between test performance and test taker characteristics (Lee & Winke, Reference Lee and Winke2018), the use of the test for different purposes such as a measure of progress (Cho & Blood, Reference Cho and Bloodin press), and standard-setting studies mapping scores to the CEFR levels (Papageorgiou & Baron, Reference Papageorgiou, Baron, Wolf and Butler2017).

In addition to argument-based approaches, other approaches to validation such as Weir's (Reference Weir2005) sociocognitive framework for test development and validation have been utilized in the context of large-scale YL assessment. An example of this type of approach is Papp et al. (Reference Papp, Rixon and Field2018), who used a set of guiding questions put forth by Weir (Reference Weir2005) when discussing constructs and research related to the Cambridge Young Learners English Tests. While placing the main focus on describing language skills, test taker characteristics, and the language development of YLs, they also critically discuss a few validity studies carried out with or in relation to the Cambridge Young Learners English Tests. Among the research discussed are pilot studies that investigated aspects such as test delivery modes of paper-based and digitally delivered tests (Papp, Khabbazbashi, & Miller, Reference Papp, Khabbazbashi and Miller2012; Papp & Walczak, Reference Papp, Walczak and Nikolov2016;), investigations of test administration for speaking assessments in trios vs. in pairs (Papp, Street, Galaczi, Khalifa, & French, Reference Papp, Street, Galaczi, Khalifa and French2010), washback studies (e.g., Tsagari, Reference Tsagari2012), and candidate performance and scoring (e.g., Marshall & Gutteridge, Reference Marshall and Gutteridge2002).

A critical component in the process of test validation—in particular when it comes to large-scale, standardized proficiency assessments for YLs—is collaboration with local users and stakeholders to ensure the fit of a given assessment for the local group of learners. For example, Timpe-Laughlin (Reference Timpe-Laughlin2018) systematically examined the fit between the EFL curriculum mandated by the ministry of education in the state of Berlin, Germany and the competencies and language skills assessed by the TOEFL Junior Standard test. To gauge the fit, curricula were reviewed and activities in textbooks were coded systematically for competences and language skills. Additionally, interviews were conducted with teachers at different schools to take into account their perspectives. While results suggested that the TOEFL Junior Standard test would be an appropriate measure for EFL learners in Berlin, findings also revealed critical areas in need of further research such as the limited availability of diagnostic information on score reports.

Overall, regardless of the validation approach utilized, it is crucial for international proficiency tests to make available empirical evidence that supports all claims made about a given assessment in order to help stakeholders in their decision-making processes. For example, when implementing a standardized assessment, it is important to consider the empirical research behind a test and whether an assessment company can back up all claims they make relative to an assessment. Paying close attention to the purpose of a large-scale assessment and potentially conducting (additional) research in the local context may provide insights into whether a large-scale assessment is a good fit, provides the intended information, and can support FL teaching and learning. Additionally, collaborative research may prevent unfounded uses of a test, promote dialog, and maybe mitigate the fact that ‘language assessment is often perceived as a technical field that should be left to measurement “experts”’ (Papageorgiou & Bailey, Reference Papageorgiou, Bailey, Papageorgiou and Bailey2019, p. xi).

3.2.2 Small-scale speaking assessments for YLs

In addition to validity research carried out in the context of international large-scale assessments, validity investigations have been conducted in relation to different types of smaller-scale assessments, among them in particular speaking tests. Most if not all curricula for YLs aim to develop speaking (Cameron, Reference Cameron2003; Edelenbos et al., Reference Edelenbos, Johnstone and Kubanek2006; McKay, Reference McKay2006); therefore, projects investigating the validity of speaking tests are of great importance. Testing YLs’ speaking ability poses unique challenges, both in classrooms and in large-scale projects. For instance, assessing speaking skills is time consuming, and special training is necessary to make sure teachers and/or test administrators can elicit children's best performances. Therefore, it is key to explore how children perform on oral tasks, how their speaking abilities develop, and how they can be assessed. In what follows in this section, we review a number of publications that feature test validation projects conducted in different countries for speaking assessments with English, French, and Japanese as TLs. These assessments include locally administered interview tasks, as well as national and international examinations.

Kondo-Brown (Reference Kondo-Brown2004), for instance, assessed the speaking skills of 30 American YLs of Japanese as a FL in fourth grade. The study explored how interviewers offered support, how the scaffolding provided by the interviewers impacted children's responses, negotiation of meaning processes, and students’ scores. The oral tasks were based on the curriculum and teachers’ classroom practices. Without clear guidance, interviewers offered inconsistent scaffolding, most often correction, and YLs had no opportunities to negotiate meaning. Supported performances tended to get better scores. This study and a similar project conducted with Greek pre-schoolers whose speaking performances were assessed with and without help from their teacher (Griva & Sivropoulou, Reference Griva and Sivropoulou2009) raise important questions about scaffolding children's speaking skills: How should teachers assess what YLs can do with support today so that it will to lead to better performance without help tomorrow? Also, to what extent do we introduce construct-irrelevant variance when providing support during interviews when scaffolding is natural and authentic in oral interactions with children?

In a similar interview format, about 110 Swiss YLs of English were tested after one year of English in year 3 to gauge their oral interaction skills (Haenni Hoti, Heinzmann, & Müller, Reference Haenni Hoti, Heinzmann, Müller and Nikolov2009). In two tasks children spoke with an adult, whereas in a role-play they interacted in pairs. Most of the YLs were able to do the tasks and fully or partially achieved A1.1 level in speaking, although considerable differences were found in their oral skills. For example, while most children used one-word utterances, a few high achievers produced utterances of nine or more words. Analyses of YLs’ task achievement, interaction strategies, complexity of utterances, and range of vocabulary offered insights into the discourse they used. This strategy allowed the authors to fine-tune expectations and evaluate the assessments.

In Croatia, 24 high, average, and low ability YLs were selected from four schools to assess their speaking skills in years 5–8 (age 11–14) to map how they were related to their motivation and self-concept (Mihaljević Djigunović, Reference Mihaljević Djigunović and Nikolov2016). The difficulty of the speaking tests (picture description tasks and interviews) increased over the four years to reflect curricular requirements, but the same assessment criteria were used. Children's test scores indicated slightly different trajectories along task achievement, vocabulary, accuracy, and fluency on the two oral tests. Their self-concept, an affective variable reflecting how good they thought they were as language learners, changed along similar lines resulting in a U-shape pattern, whereas their motivation showed an inverted U shape.

3.2.3 C-tests for YLs

In addition to speaking assessments, the field is beginning to see validation research conducted on other types of YL assessment formats such as a C-test, a type of gap-filling test that is based on the principle of reduced redundancy and measures general language proficiency (Klein-Braley, Reference Klein-Braley1997). For example, validating an integrated task was the aim of a study on 201 German fourth graders learning English. Porsch and Wilden (Reference Porsch, Wilden, Enever and Lindgren2017) designed four short C-tests based on adapted texts and analyzed relationships between YL's school grades in English and test-taker strategies. They found statistically significant relationships (.40–.50) between grades and scores, and frequency of strategy use conducive to reading comprehension. They did not investigate how much practice children needed to do C-tests or how scores compared to other reading comprehension tests. Additional research may want to investigate via think aloud or eye-tracking methodology how YLs approach and engage with C-tests.

3.3 Comparative YL assessment projects across ages, contexts, and types of programs

Much of assessment of learning research has been conducted to compare achievements across different YL programs such as those in which students start at an earlier and later age. In addition, YLs’ achievements have been compared across countries as well as across different types of YL education programs. In particular, outcomes of FL and CLIL programs have been investigated.

3.3.1 Comparative assessments of YLs in early and later start programs

As new FL programs were gradually introduced that targeted increasingly younger learners, it made sense to compare YLs’ L2 skills on the basis of the age at which they began programs. Such a comparative research design could offer evidence in what domains YLs are better in the L2 and how implicit and explicit learning emerge. Thus far, we have witnessed a number of projects across Europe: in the 1990s, studies were conducted in Croatia (Mihaljević Djigunović & Vilke, Reference Mihaljević Djigunović, Vilke, Moon and Nikolov2000) and in Spain (García Mayo, Reference García Mayo, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003; Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2006), followed by research in Germany (Wilden & Porsch, Reference Wilden, Porsch and Nikolov2016; Jaekel, Schurig, Florian, & Ritter, Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017), Switzerland (Pfenninger & Singleton, Reference Pfenninger and Singleton2017, Reference Pfenninger and Singleton2018), and Denmark (Fenyvesi, Hansen, & Cadierno, Reference Fenyvesi, Hansen and Cadierno2018) in the 2000s.

In Croatia (Mihaljević Djigunović & Vilke, Reference Mihaljević Djigunović, Vilke, Moon and Nikolov2000), over 1,000 YLs (age 6–7) started to learn English, French, German, and Italian in their first grade in four or five hours a week in the first four years; then, from year 5, similarly to control groups who started in fourth grade (age 10–11), all YLs had three weekly classes. YLs were assessed after eight and five years, respectively, in their last year in primary school. Children in the early start cohort were significantly better at pronunciation, orthography, vocabulary tasks, and a C-test, and slightly better at reading comprehension. The control group outperformed their peers on a test of cultural elements. YLs’ oral skills assessed by a single interview task were better in the early start groups, although significant variability was observed in all groups.

In Spain, two studies involved bilingual YLs who started English as their third language at the ages of 4, 8, and 11. A similar research design was used to compare 135 Basque-Spanish (Cenoz, Reference Cenoz, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003; García Mayo, Reference García Mayo, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003) and over 2,000 Catalan-Spanish (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003, Reference Muñoz2006) children in three cohorts after about 200, 400, and 700 hours of EFL instruction. In order to compare results of the different age groups, the same tests were used to assess participants’ English speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003, p. 167). The key variables in both projects were starting age and amount of formal instruction. The tests were not based on the YLs’ respective curricula, but they targeted what all groups were expected to be able to do. Some tests were meaning-focused (e.g., story-telling based on pictures, C-test on a well-known fairy tale, matching sentences in dialogs with pictures, letter writing to host family), whereas others focused on form (e.g., fill in blanks with ‘auxiliaries, pronouns, quantifiers’ and ‘choose adverbs to describe eating habits’ Cenoz, Reference Cenoz, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003, p. 84). Overall, the later the groups started learning English, the better they performed on the tests at each point of measurement. In both projects, lower levels of cognitive skills were identified as the main reason for the slower rate of progress among YLs (Cenoz, Reference Cenoz, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003; García Lecumberri & Gallardo del Puerto, Reference García Lecumberri, Gallardo del Puerto, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003; García Mayo, Reference García Mayo, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003; Lasagabaster & Doiz, Reference Lasagabaster, Doiz, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003; Muñoz, Reference Muñoz, García Mayo and García Lecumberri2003). This outcome might be due to the lack of age-appropriate tests, as many assessments seemed to favor cognitively more mature age groups, thus potentially failing to tap into what YLs at earlier stages were able to do well. Unfortunately, no data were collected on factors that must also have impacted outcomes such as what was taught in the courses, how proficient the teachers were, and how much English they used for what purposes in the classroom.

In Germany, a recent change in language policy motivated a large-scale assessment project comparing the proficiency of YLs who started English in years 1 and 3 (Wilden & Porsch, Reference Wilden, Porsch and Nikolov2016; Jaekel et al., Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017). The listening and reading comprehension skills of more than 5,000 YLs were tested in year 5 after learning English for two vs. three and a half years and in year 7 after two more years in grammar schools. In addition to testing participants’ English development, the researchers also assessed students’ literacy skills, their socioeconomic status (SES), and whether German was their L1 to examine what factors contributed to YLs’ English scores. In year 5, listening comprehension was tested by multiple-choice items on picture recognition and sentence completion in German, whereas reading comprehension was assessed by multiple-choice and open items. In year 7, both the listening and reading comprehension tests included open and multiple-choice items, and some items were identical in years 5 and 7. In year 5, YLs in the earlier start cohort performed significantly better at the English tests than their peers starting later, and scores on German reading comprehension tests contributed to the outcomes indicating the importance of an underlying language ability. However, in year 7, late starters outperformed their peers, which cast serious doubts on the value of starting English early (Jaekel et al., Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017). Interestingly, test results in year 9 showed a different picture: early starters achieved significantly higher scores than late starters (Jaekel, p.c., July 17, 2019), making the outcome in year 7 hard to explain.

Lowering the starting age of mandatory EFL education triggered yet another comparative study on YLs starting at different times in Denmark. A total of 276 Danish YLs were assessed in two groups after learning English for a year in grades 1 (age 7–8) and 3 (age 9–10) (Fenyvesi et al., Reference Fenyvesi, Hansen and Cadierno2018) to assess how their development in receptive vocabulary and grammar interacted with individual differences and other variables. The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test PPVT-4 and the Test for Reception of Grammar TROG-2 (Bishop, Reference Bishop2003) were used twice, following Unsworth, Persson, Prins, and de Bot (Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and de Bot2014): at the beginning and the end of their first year of English. Both tests used pictures and YLs had to choose the correct word or sentence from four options. Children in the early start group achieved significantly lower scores on both tests at both points of measurement than their peers starting in year 3. Both groups achieved significantly better results after a year, but the rate of learning was not higher for the older group. Interestingly, older YLs at the beginning of formal EFL learning achieved similar scores to those in the early start group after a year of EFL. This result indicates how children benefit from extramural English activities (see a more detailed discussion in Section 3.5).

In one of the most comprehensive, longitudinal studies, over 600 Swiss YLs participated in a study to find out why older learners tend to perform better in classroom settings (Pfenninger & Singleton, Reference Pfenninger and Singleton2017, p. 2018). In addition to age of onset (when YLs started learning English), they included the impact of YLs’ bilingualism/biliteracy and their families’ direct and indirect support. Participants were 325 early (age 8) and 311 later (age 13) starters; they were assessed after five years and six months of English, respectively. Early and later starters included subgroups of monolingual Swiss German children, simultaneous bilinguals (biliterate in one or two languages), and sequential bilinguals (illiterate in their L1; proficient in Swiss German). As the authors point out, Swiss curricula target B1 at the end of compulsory education, and they intended to use the same tests four years later. Therefore, the proficiency of all YLs was tested by (1) two listening comprehension tests at B2 level, (2) Receptive Vocabulary Levels Test (Schmitt, Schmitt, & Clapham, Reference Schmitt, Schmitt and Clapham2001); (3) Productive Vocabulary Size Test (Laufer & Nation, Reference Laufer and Nation1999); (4) an argumentative essay on talent shows; (5) two oral (retelling and spot-the-difference) tasks that were evaluated based on four criteria: lexical richness, syntactic complexity, fluency, and accuracy; and (6) a grammaticality judgment task. However, they did not use the listening and the productive vocabulary tests in the first round. Using multilevel modeling, they found that in neither written nor oral production did the early starters outperform the late starters. Over a period of five years, late starters were able to catch up with early starters insofar as late starters needed only six years to achieve the same level as early starters had after eleven years—a result that Pfenninger and Singleton (Reference Pfenninger and Singleton2017) attributed to strategic learning and motivation. Additionally, findings showed that biliterate students scored higher than their monoliterate peers, and family involvement was always better than no involvement. A combination of biliteracy and family support was found to be particularly effective. Besides these factors, random effects made up much of the variance, indicating that it is almost impossible to integrate all factors into models.

In all of the comparative studies reviewed in Section 3.3, the research design impacted when and how YLs were tested. Findings indicate that the tests that were used were intended to tap into both implicit and explicit learning, but the exact emphasis on each is unclear. It is remarkable that hardly any of the tests were aligned with early FL curricula or the age-related characteristics of the YLs. Hence, it is quite likely that the tests were more appropriate for more mature learners, while failing to elicit the full potential YLs’ FL achievements.

3.3.2 Comparative assessments of YLs in different educational contexts

In addition to comparisons with regard to age or age of onset, several studies that focused on the assessment of learning were conducted to examine impacts of learning environments. In this section, we discuss assessment projects comparing YLs’ achievements in early FL programs. In Section 3.3.3, we review research that focused on different types of early FL programs, in particular CLIL contexts.

The most ambitious comparative project, Early Language Learning in Europe (ELLiE), assessed YLs from seven European countries over three years. The project applied mixed methods and involved about 1,400 children from Croatia, England, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Sweden. In particular, Szpotowicz and Lindgren (Reference Szpotowicz, Lindgren and Enever2011) analyzed what level YLs achieved in the first years of learning an FL. In the first two years, YLs’ listening and speaking skills were assessed, whereas in the third year, their reading comprehension was also tested. The number of items and the level of difficulty increased in the listening and speaking tests every year. Oral production was elicited by prompts in YLs’ L1 to assess what they would say in a restaurant situation. The publication includes sample oral performances and graphic presentation of data, but it lacks any statistical analyses. The authors claimed that by age 11, average YLs made good progress toward achieving A1 level, the typical attainment target in YL curricula, but they emphasized high variability among learners.

In Croatia and Hungary, Mihaljević Djigunović, Nikolov, and Ottó (Reference Mihaljević Djigunović, Nikolov and Ottó2008) compared Croatian and Hungarian YLs’ performances on the same EFL tests in the last year of their primary studies (age 14) to find out how length of instruction in years, frequency of weekly classes, and size of group impacted YLs proficiency. They used ten tasks to assess all four language skills and pragmatics. Although Hungarian students started learning English earlier, in smaller groups, and in more hours overall, Croatian EFL learners were significantly better at listening and reading comprehension, most probably due to less variation in their curricula and more exposure to media in English (e.g., undubbed television).

Over the course of three years, Peng and Zheng (Reference Peng, Zheng and Nikolov2016) compared two groups of young EFL learners from the same elementary school in Chongqing, China. Teachers used two different textbooks and corresponding assessments in the two learner groups. One group used the PEP English (n = 304) which tends to foreground vocabulary and grammar, the other used the Oxford English (n = 194), which was identified as having a stronger focus on communicative abilities. Students were assessed in years 4, 5, and 6 using the assessments that accompany the materials they learned from. Overall, scores declined slightly over the years. To triangulate the data, teachers were interviewed to reflect on the coursebooks, the tests, the results, and the difficulties they faced when assessing YLs. The authors offered valuable insights into how children's performances decreased over the years, indicating in particular motivational issues in the group that used PEP English with its focus on grammar and vocabulary.

3.3.3 Comparative assessments of YLs in FL and content-based programs

As early FL programs and approaches to teaching FLs to YLs vary considerably (see Introduction), contents and goals of early FL learning do so as well. In FL programs, the achievement targets in knowledge and skills are defined in terms of the L2. In CLIL programs, by definition, the aims include knowledge and skills in the FL as well as in the subject (content area) studied in the FL. In short, there are considerable differences between the goals and contents of YL instruction in FL programs and CLIL programs.

From a measurement perspective, it is important that the construct of an assessment is in line with curricular goals. Therefore, summative assessments aimed at capturing YLs’ achievements should operationalize aspects of the constructs that reflect the various curricular objectives. In FL programs, the construct should be operationalized in terms of FL learning, while in CLIL programs, both the FL proficiency and the subject area domains should be accounted for in the test construct. However, this juxtaposition of FL and content learning is not necessarily reflected in assessment projects that focus on CLIL programs. For example, Agustín Llach (Reference Agustín Llach2015) compared two groups of Spanish fourth graders’ (72 CLIL, Science; 68 non-CLIL) productive and receptive vocabulary profiles on an age-appropriate letter writing task (introduce yourself to a host family) and the 2k Vocabulary Levels Test (VLT; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Schmitt and Clapham2001). The VLT Receptive Vocabulary Test uses multiple matching items organized in ten groups of six words corresponding to three definitions. Scores ranged between 0 and 30. No significant differences were found between the two groups, despite 281 hours of CLIL in addition to 419 hours of EFL. On the writing task, YLs’ vocabulary profiles were drawn up based on type/token ratios and lexical density. In both groups phonetic spelling was frequent and low scores on cognates were typical, indicating, in our view, low level of vocabulary knowledge and use of strategies. The author suggested that children's lack of cognitive skills must have been responsible for not benefiting from CLIL, although, most probably, the two selected tests must have played a role in not capturing vocabulary from YLs’ CLIL classrooms.

In a longitudinal study, Agustín Llach and Canga Alonso (Reference Agustín Llach2016) assessed growth in receptive vocabulary of 58 CLIL and 49 non-CLIL Spanish learners of English in fourth, fifth and sixth grade by using the VLT test. After three years, the differences were modest, but vocabulary knowledge was significantly higher for CLIL learners. The rate of growth was quite similar in the two groups: 914 vs. 827 words, respectively, in year 6 after 944 vs. 629 hours of instruction. No tests were used to tap into the vocabulary taught in the CLIL classes.

A similar research design was used in Finland by Merikivi and Pietilä (Reference Merikivi and Pietilä2014) to compare CLIL (n = 75) and non-CLIL (n = 74) sixth graders’ (age 13) English vocabulary. In this context, CLIL instruction was not preceded by or complemented by EFL learning. YLs in the CLIL group had 2,600 hours of English and in the non-CLIL group 330 hours. In addition to the VLT, the Productive VLT (PVLT) was also used (version 2; YLs fill in parts of missing words in sentences). CLIL learners’ receptive and productive vocabulary scores were significantly higher (4,505; 1,853, respectively) than those of their non-CLIL peers (2,271; 788). Nevertheless, results on the VLT are directly comparable with those of the Spanish sixth-graders (Agustín Llach & Canga Alonso, Reference Agustín Llach2016). Although Finnish belongs to a different (Finno-Ugric) language family, and English and Spanish are both Indo-European languages, Finnish sixth-graders achieved much higher scores than their Spanish peers not only in the CLIL group but also in the EFL group (2,271 vs. 827). These outcomes must have resulted from the quality of instruction and should be examined further.