1. Introduction

Over the last three decades, data-driven learning (DDL) has been widely championed by those of us who see the exciting opportunities that it can bring to the language learner. From the initial days of DDL, there has been a sense of enthusiasm about turning language learners into researchers who will embrace language discovery (Johns, Reference Johns1986; Barlow, Reference Barlow1996; Tribble & Jones, Reference Tribble and Jones1997). We have believed that, as Pérez-Paredes (Reference Pérez-Paredes, Harris and Moreno Jaén2010) puts it, the methods of research in corpus linguistics can be transferred to the language classroom by turning linguists’ analytical procedures into a pedagogically relevant tool to increase both learners’ awareness of and sensitivity to patterns of language while also enhancing language learning strategies. Pedagogically core to DDL is the aim of fostering the independent acquisition of language knowledge (lexis, grammatical constructions, collocations, and so on). Within the ethos of DDL, learners are encouraged, in inductive processes, to discover patterns of language. It is widely claimed that such an endeavour aims to foster more complex cognitive processes such as making inferences and forming hypotheses (O'Sullivan, Reference O'Sullivan2007; Lee, Warschauer, & Lee, Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019).

It is fair to say that the early enthusiasm was counter-balanced by some words of caution. Leech (Reference Leech, Wichmann, Fligelstone, McEnery and Knowles1997, p. 5) observed that while research is a natural extension of teaching and enables the learner to explore, investigate, generalize and test hypotheses, ‘it does not itself initiate or direct the path of learning’. Leech saw this as part of the teacher's role. Widdowson (Reference Widdowson and Alatis1991, p. 20ff.), referring to corpus insights, argued that ‘[s]uch analysis provides us with facts, hitherto unknown, or ignored, but they do not themselves carry any guarantee of pedagogic relevance’. Authors such as Römer (Reference Römer2006), Tribble (Reference Tribble2008) and Pérez-Paredes (Reference Pérez-Paredes, Harris and Moreno Jaén2010) have pointed to the need to find a plausible way of moving DDL from a research-oriented process suited to university settings (where learners analyse, hypothesize and discover language) to one with a broader pedagogical application and theoretical underpinning. As Römer (Reference Römer2006, p. 129) noted, a lot still remains to be done before arriving at the point where it can be said that ‘corpora have actually arrived in language pedagogy’.

Over a decade ago, while the late Stig Johansson lauded the potential of DDL for enhancing language learning because of the parallels between the natural processes of language acquisition and the processes involved in hypothesizing about language in DDL, he also called for a greater connection between DDL and second language acquisition (SLA) research (Johansson, Reference Johansson and Aijmer2009). Johansson foresaw connections that could be made with ongoing SLA work on attention and awareness as well as concepts such as input enhancement. Unfortunately, few of the many worthwhile DDL studies over the years have engaged with SLA theory and indeed few SLA studies have sought out DDL as a means of exploring their hypotheses. In this plenary paper, I wish to make a case for a broadening in our research gaze. Firstly, I want to look closely at the pedagogical and theoretical underpinnings of DDL. These are often inter-connected with SLA but under-explored by both DDL and SLA researchers. I want to focus on the question of how and where DDL fits within current SLA models and debates. And underlying all of this, I want to address why, as DDL advocates and enthusiasts, we should care about these issues. In summary, I will argue that while there has been a number of helpful meta-analyses, reflections and reviews of ongoing DDL work across many variables, there has been a dearth of focus on the learning theories that underpin DDL and on how this approach might inter-relate with SLA theories and vice versa. I will also argue that DDL is well-placed to be part of experimental research that could lead to cutting-edge insights into the cognitive processes of language learning and enhance ongoing SLA debates, especially in relation to implicit and explicit learning processes. Before we look at these issues, let us briefly summarize where the current meta-studies have brought us to in terms of our aggregated understanding of DDL.

2. An overview of overviews of DDL

As Boulton and Cobb (Reference Boulton and Cobb2017) note, DDL is a flourishing field and it is fair to say that there has been no shortage of empirical DDL research, as well as many reviews, syntheses and meta-studies (see Chambers, Reference Chambers, Hidalgo, Quereda and Santana2007; Boulton, Reference Boulton, Boulton, Carter-Thomas and Rowley-Jolivet2012; Boulton & Pérez-Paredes, Reference Boulton and Pérez-Paredes2014; Cobb & Boulton, Reference Cobb, Boulton, Biber and Reppen2015; Mizumoto & Chujo, Reference Mizumoto and Chujo2015; Boulton & Cobb, Reference Boulton and Cobb2017; Vyatkina & Boulton, Reference Vyatkina and Boulton2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019). All of these point to the value of DDL and meta-studies show a positive effect size overall (Cobb & Boulton, Reference Cobb, Boulton, Biber and Reppen2015; Mizumoto & Chujo, Reference Mizumoto and Chujo2015; Boulton & Cobb, Reference Boulton and Cobb2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019). Studies illustrate an undying enthusiasm and express a conviction about the worthiness of DDL as an aid to learning, as well as an aspiration that it should become more mainstream. Recurring issues emerge within these meta-studies and for the most part, classroom-based studies have served to greatly inform these, as the main meta-studies show:

• What is the best DDL interaction type: learners engaging in hands-on computer-based processes or using pre-prepared print-outs of selected concordances?

• What is the most suited level of proficiency required for successful DDL? Is it best suited to learners at an intermediate level of proficiency, and above?

• What is the best type of corpus data to use: locally curated corpora or publicly available data?

• What is the degree of learner training required to ensure successful learning outcomes?

• In which context does DDL work best: general ELT, ESL, EFL, EAPFootnote 1 or specialized university programmes or settings?

• Is DDL best suited to certain teaching points: vocabulary, grammar, lexicogrammar, text-awareness or discourse level items?

Boulton and Cobb (Reference Boulton and Cobb2017, p. 386), whose meta-study analysed 64 empirical studies, concluded that DDL seems to be ‘most appropriate in foreign language contexts for undergraduates as much as graduates, for intermediate levels as much as advanced, for general as much as specific/academic purposes, for local as much as large corpora, for hands-on concordancing as much as for paper-based exploration, for learning as much as reference, and particularly for vocabulary and lexicogrammar’. They note that many of these findings go against common perceptions and they arrive at the ‘surprising and possibly encouraging conclusion that DDL works pretty well in almost any context where it has been extensively tried’ (Boulton & Cobb, Reference Boulton and Cobb2017, p. 39).

Taking a different focus and using a different methodology to correlate their meta-study, Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019) looked at 29 studies, concentrating only on the effect of corpus use on second language (L2) vocabulary learning. They reported that their ‘meta-analysis showed a medium-sized effect on L2 vocabulary learning, with the greatest benefits for promoting in-depth knowledge to learners who have at least intermediate L2 proficiency’ (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019, p. 25). As with Boulton and Cobb (Reference Boulton and Cobb2017), they found a positive effect size for learners from intermediate level upwards, but they warn that their finding is based on very limited data: there were only four effect sizes coming from one unique sample for high proficiency levels. Slightly varying with Boulton and Cobb (Reference Boulton and Cobb2017), they found that corpus use was more effective when the concordance lines were purposefully curated for learners and when learning materials were given along with hands-on corpus-use opportunities (though it is noted that they were not comparing like-with-like as they were only focusing on vocabulary and were using a different quantitative approach to calculate effect size). Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019) also report that corpus use was effective for vocabulary learning even without prior training, regardless of the corpus type or the duration of a given intervention.

In summary, encoded within many of the key works on DDL has been a strongly held belief in, enthusiasm for and evidence of the benefits of DDL by those who use it. It is seen to enhance learning through the active and independent approach that underpins it. However, I make a call for DDL researchers to broaden their research gaze so as to inform the debates within the field of instructed SLA. By doing so, researchers will be opened up to more refined outcome variables in classroom-based research. A broader focus will also provide opportunities for experimental research work within DDL through engagement with SLA researchers. As a first step in broadening our research base, let us consider the lack of robust definition of the theoretical underpinnings of DDL as a pedagogical approach in itself.

3. DDL and theories of learning

3.1 Constructivism and DDL

As noted by Cobb (Reference Cobb1999) constructivism can provide theoretical support for corpus use. When we think of constructivism (a term linked to educational psychology, and derived from psychology), we think of processes and concepts such as: induction, inference, hypothesizing, learner-centredness and discovery learning. It is fair to say that from the outset, we have lauded such constructivist ideals in DDL. Johns (Reference Johns and Odlin1994, p. 297), for instance, sought to ‘cut out the middleman as far as possible’ so as to give direct access to the corpus data and thus allow learners to build up their own profiles of meaning and use. We saw corpus data as offering ‘a unique resource for the stimulation of inductive learning strategies – in particular the strategies of perceiving similarities and differences and of hypothesis formation and testing’ (Johns, Reference Johns and Odlin1994, p. 297). In its purest form then, we saw DDL as open discovery rather than a teacher-curated or -mediated focus on language input. In this sense, the aim is that the learner will discover as salient (i.e. notice as relevant to them) any new language input, based on their own free-range explorations. Increased and intensive exposure to linguistic input through DDL is seen as increasing the likelihood of a given linguistic item becoming noticed by a learner (Cobb, Reference Cobb1997, Reference Cobb1999; Collentine, Reference Collentine2000; Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew, Leńko-Szymańska and Boulton2015). The long-held and widespread consensus is that the core pedagogical benefit of DDL lies in its potential to encourage learners to construct their L2 knowledge independently by exploring the linguistic data from corpus input (Johns, Reference Johns and Odlin1994; Cobb, Reference Cobb1999; Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew, Leńko-Szymańska and Boulton2015; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019). The associative link to constructivism is seen as a pedagogical hallmark for DDL.

Constructivist pedagogies are process-oriented, meaning that learners engage in tasks that draw upon and activate higher-order cognitive skills that are associated with inductive learning. As O'Sullivan (Reference O'Sullivan2007, p. 277) speculates, DDL is likely to draw on and refine cognitive skills such as: ‘predicting, observing, noticing, thinking, reasoning, analysing, interpreting, reflecting, exploring, making inferences (inductively or deductively), focusing, guessing, comparing, differentiating, theorizing, hypothesizing, and verifying’. However, this link between DDL and the application of higher-order cognitive skills has seldom been tested, leaving open the possibility of logical fallacy. This point has not gone unnoticed by some of the main researchers of DDL. Boulton (Reference Boulton, Boulton, Carter-Thomas and Rowley-Jolivet2012, p. 86) put it starkly: ‘ …it is notable that much of the research to date focuses on targets that are easy to measure in a highly controlled experimental environment – short-term learning outcomes in vocabulary and lexico-grammar, as well as error correction and Likert-scale questionnaires of learner attitudes, etc.’. Additionally, Boulton notes that while such studies undoubtedly provide some valuable insights, ‘there is a notable dearth of studies looking at the major advantages that are generally attributed to DDL’ (Reference Boulton, Boulton, Carter-Thomas and Rowley-Jolivet2012, p. 86), including its long-term effects on learner autonomy, responsibility, life-long learning, constructivism, cognitive and metacognitive development, among other areas listed in Boulton (Reference Boulton, Boulton, Carter-Thomas and Rowley-Jolivet2012, p. 86). Essentially, while independent discovery learning is (rightly) much lauded in DDL work, the specific nature of this learning is under-explored and rarely critiqued.

Constructivism and DDL have been investigated in terms of the benefits for vocabulary learning, retention and transferability through delayed post-tests (cf. Cobb, Reference Cobb1997, Reference Cobb1999). Such studies attempt to explore the nature of vocabulary learning. These studies add weight to the benefits of computer-based learning of vocabulary, and related patterns, over more transmissive definitional learning of vocabulary (see Cobb & Boulton, Reference Cobb, Boulton, Biber and Reppen2015, for an overview).

Albeit small in scale, Chang (Reference Chang2012) is one of a small number of studies that examines the types of cognitive skills with which DDL actually engages. This study, involving seven doctoral students, evaluated a web-based corpus interface developed to enhance authorial stance. One of the research goals sought to investigate whether the tool fostered a constructivist environment which would prompt learners to infer linguistic patterns so as to attain deeper understanding. Chang found that the application of higher-order skills, such as inference, was infrequent and reported that users deployed more lower-level cognitive skills such as making sense and exploring as their main learning processes. Studies such as Todd (Reference Todd2001) and Gabel (Reference Gabel2001) also attempted, through quasi-experimental methods, to explore and measure learners’ ability to induce rules and self-correct. While both report positive results and correlations, as Papp (Reference Papp, Hilgado, Quereda and Santana2007) notes, neither study's research design captured students’ ability to induce patterns and self-correct (see also Pérez-Paredes, Sánchez-Tornel, & Alcaraz Calero, Reference Pérez-Paredes, Sánchez-Tornel and Alcaraz Calero2012).

Constructivism is not an educational panacea. Over the years, there have been many critics of it. However, apart from some notable exceptions (e.g. Boulton, Reference Boulton and Gimeno Sanz2010, Reference Boulton, Boulton, Carter-Thomas and Rowley-Jolivet2012; Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew, Leńko-Szymańska and Boulton2015), critiques do not often feature in DDL literature. For example, key criticisms include that while learner independence and self-directed discovery learning are rightly lauded within the constructivist paradigm, such approaches may not work for all learners. Many learners may resist independent process-oriented learning (see McGroarty, Reference McGroarty1998; Kirschner, Sweller, & Clark, Reference Kirschner, Sweller and Clark2006). Others have commented on the cognitive demands that this approach puts on learners, advocating for the need for more supports for learners in terms of scaffolding (see Cobb & Boulton, Reference Cobb, Boulton, Biber and Reppen2015 for a useful discussion on this).

Gabrielatos (Reference Gabrielatos2005) distinguishes between hard and soft approaches across a spectrum from teacher- to learner-controlledness. As evidenced by recent meta-studies (Section 2), this is manifested in terms of hands-on corpus use versus teacher-curated handouts of corpus data; the degree of learner training and teacher mediation and support; the degree of curation of corpus data and software by the teacher; the role of pre-teaching of form versus free discovery, and so on. However, these are not linked to or discussed in the context of what they mean for or how they relate to learning. As meta-studies have shown, there is a tendency to measure net learning through pre- and post-testing rather than to scrutinize the nature of the learning.

3.2 Sociocultural theory and DDL

Constructivism, within educational psychology, came in for some criticism because too much wandering off on independent learning pathways was seen as opening up the possibility that some learners simply went astray in terms of learning outcomes. In DDL, it is possible that learners too may get lost amid the data (and some would argue that this is not a bad thing!) or that they may induce or infer incorrectly or just not infer anything at all. To counter this, some work on DDL has focused on the importance of ‘scaffolding’, a term coined by psychologist Jerome Bruner to refer to the use of some kind of supporting mediation in the learning process within a sociocultural theory (SCT) paradigm. Some key SCT-related concepts are seen as a boon of DDL for learners. These include, for example, the development of learner agency and self-regulation (O'Keeffe, McCarthy, & Carter, Reference O'Keeffe, McCarthy and Carter2007; Cobb & Boulton, Reference Cobb, Boulton, Biber and Reppen2015; Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew, Leńko-Szymańska and Boulton2015). Learner agency refers to empowerment, whereby the learner takes control of learning rather than assuming a passive role in a transmissive relationship with the teacher. The enhancement of learner agency is cited, though not empirically explored, as one of the main advantages of DDL by O'Keeffe et al. (Reference O'Keeffe, McCarthy and Carter2007). It is argued that learners can be trained to operate independently to develop skills and strategies and, in the process, they can ‘surpass instructional intervention and become a better, self-regulated learner’ (O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, McCarthy and Carter2007, p. 55).

As Flowerdew (Reference Flowerdew, Leńko-Szymańska and Boulton2015) notes, some studies involving learners have explored learner agency, for example Cobb (Reference Cobb1999) and Chau (Reference Chau2003). Though these studies are not designed to measure these aspects experimentally (e.g. findings were observed from delayed post-tests), their results suggest positive outcomes in relation to learner agency. The emergence of DDL work on the role of mediation through intra- and interpersonal dialogues in the acquisition of grammar through computer-aided discovery is found in Huang's (Reference Huang2011) study. Though small in scale, this fourteen-week study of undergraduates examined ten groups of three learners. Learners’ peer-to-peer dialogues were recorded. Students also kept logs. Reflected in the findings was a link between higher performance and engagement with peers in negotiating form-focused episodes, leading to correct conclusions about a given form. Huang (Reference Huang2011) is tentative about her findings, given the sample size and the many variables that were not controlled within the study. Albeit fledgling in nature, an importance aspect of this study is that its research gaze expanded to include a core concept within a learning theory (in this case SCT) in relation to DDL.

Despite the many possibilities for seams of DDL research in relation to SCT, large-scale studies that robustly investigate the role and nature of mediation and scaffolding in terms of the use of DDL do not yet exist. As we shall discuss, the scope for enhancement in this regard, in terms of expanding the research scope of DDL, is great.

Central to the Vygotskyan notion of SCT is the idea that cognitive processes are mediated and that language is one of the most important tools in this activity (see Swain, Reference Swain and Byrnes2006). Through dialogue, higher-order cognitive processes are shaped and re-shaped. Within the classroom, mediation may happen through a teacher or a peer or it may involve the self, through private talk or inner speech. Essentially, it is via mediation, manifested through dialogue, that we learn because, in this collaborative process, we engage in the co-construction of knowledge. Clearly, while there is some overlap between SCT and constructivist tenets, fundamentally, an SCT view of DDL moves away from the notion of a learner independently grappling (Cobb, Reference Cobb2005) with the data in a discovery process to a focus on the nature of such grappling and how it can be supported in order to lead to enhanced learning opportunities through self-regulation or mediation by peers or a teacher.

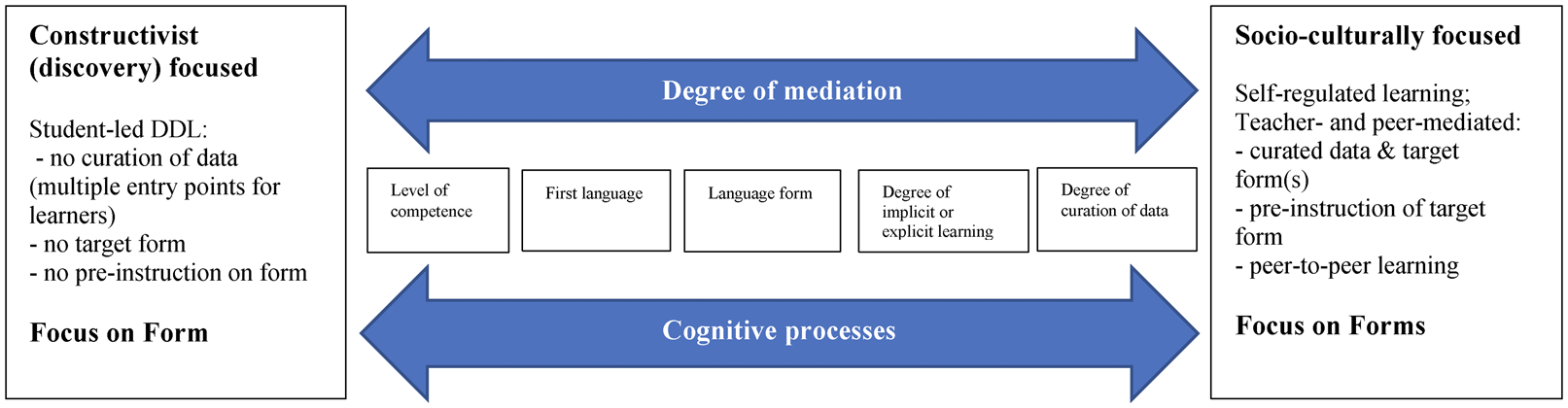

3.4 Positioning DDL theoretically

As we have discussed, one way of looking at work on DDL over the years has been to broadly categorize it in terms of how it views learning. Some studies view learning more within a constructivist paradigm where learners engage with language using independent discovery processes. Other studies take a more SCT-like perspective on learning which values peer- and teacher-mediation and learner self-regulation. Figure 1 represents this as a schematic cline from constructivism to SCT across some key variables. Note: this cline is not presented as a longitudinal development, rather is it a framework for interpretation of the pedagogical stance underpinning work on DDL.

Figure 1. DDL cline of learning from constructivist to socioculturalist stances on learning

By mapping out the theoretical position and what this means for learners, data type, target form (learning outcome), in-class treatment and the role of peers, for example, we can see that at one end of the cline, learner-led discovery means the learner controls what is being learnt (e.g. through choices of which data searches and processes). At the other end of this schematic cline, in a more mediated SCT scenario, the teacher and learners (as individuals and with peers) have a role in the learning process either through self-regulation or collaboration. For instance, the teacher may have chosen the target language that is being focused on, in line with an external syllabus, the teacher may have provided pre-instruction on the target form(s) and may have curated the data and interface (e.g. a corpus of learner readers at the proficiency level of the class, e.g. Allan, Reference Allan2009). The teacher may have chosen a corpus task that is designed for peer-to-peer learning.

At one end of this theoretical cline, discovery leaves learning open and more to chance (and of course this can lead to many insights). It may also leave more open the possibility of incidental discovery of form and meaning at a subconscious level through implicit subconscious processes. Equally, the freer discovery approach runs the risk of no learning taking place or the risk of fake discovery. At the other end of the cline, the more mediated and structured model poses a more teacher-controlled format, with a more explicit syllabus where a form or particular data is overtly curated for the learners. This difference will tie in with the second part of this paper when I look at a key debate in SLA, in relation to Focus on Form (FonF) and Focus on Forms (FonFs) approach.

One of the many reasons why these theoretical considerations are important to DDL research is because we cannot compare classroom-based studies from an instructional perspective without an insight into the ontological stance of the teacher(s) in the study.

If we can provide a more detailed articulation of the pedagogical underpinnings of DDL and the related teaching and learning processes, we will be able to align more with key areas of concern within instructed SLA, as we shall now discuss.

4. DDL, theories of SLA and new opportunities for research

In their meta-study, Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019) draw links between some of the SLA concepts and the use of concordance lines. They cite Schmidt's Noticing Hypothesis (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1990, Reference Schmidt and Robinson2001; Lai & Zhao, Reference Lai and Zhao2006); the usage-based (UB) model (Ellis, Reference Ellis2002; Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2003); input enhancement (Chapelle, Reference Chapelle2003; Wong, Reference Wong2005); involvement load hypothesis (Laufer & Hulstijn, Reference Laufer and Hulstijn2001) as supporting the DDL approach. So from this we can clearly see that some aspects of SLA theory get a mention in DDL research but these references often form part of the rationale for using DDL or appear as add-ons within the discussion of empirical findings. Flowerdew (Reference Flowerdew, Leńko-Szymańska and Boulton2015) and Pérez-Paredes (Reference Pérez-Paredes2019) are some of the lone voices that have called out this lack of connection with SLA. Papp (Reference Papp, Hilgado, Quereda and Santana2007) is another exception; she offers a worthwhile summary of the psycholinguistic processes relating to the concept of noticing.

4.1 Attention, noticing and exposure

Within SLA, there is a general acceptance that paying attention to certain features of language input is a requirement for language development (Indrarathne, Ratajczak, & Kormos, Reference Indrarathne, Ratajczak and Kormos2018). Many studies have looked at the effect of attention on input processing (e.g. Cintrón-Valentín & Ellis, Reference Cintrón-Valentín and Ellis2015). The Noticing Hypothesis (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1990, Reference Schmidt and Robinson2001; Lai & Zhao, Reference Lai, Zhao and Zhao2005) is widely accepted and the related term ‘noticing’ is defined as attention that involves conscious awareness (Indrarathne et al., Reference Indrarathne, Ratajczak and Kormos2018). Though the Noticing Hypothesis is frequently cited in DDL studies as a boon of the approach, the broader concept of attention (and how it manifests via DDL) might be worth much more investigation. Over the years, many DDL studies refer to experimental groups showing enhanced noticing which must have resulted from either conscious or subconscious attention (see Boulton, Reference Boulton and Gimeno Sanz2010; Shi, Reference Shi2014).

Noticing and attention are linked with salience of input for learners (where salience refers to the degree to which something stands out or catches the learner's attention, see VanPatten & Benati, Reference VanPatten and Benati2010). Sometimes learners will give attention to, notice and make salient a form at an implicit or subconscious level. Other times (and often relative to the form itself), explicit instruction may be needed in order for this process to take place. In essence, SLA studies of attention, noticing and salience seek to establish how frequently a learner needs to be exposed to a novel item through encounters in a text before they acquire the form (see Bybee, Reference Bybee, Robinson and Ellis2008; Ellis, Reference Ellis, Gass, Spinner and Behney2018; Gass, Spinner, & Behney, Reference Gass, Spinner, Behney, Gass, Spinner and Behney2018). Variables such as the effectiveness of explicit and implicit instruction techniques and the degree of attention, noticing and learning are variously explored (in SLA). Indrarathne et al. (Reference Indrarathne, Ratajczak and Kormos2018) note that the role of frequency and nature of exposure to constructions is crucial to understanding how grammatical knowledge develops both from a pedagogical and a theoretical perspective.

Given the use of computer screens as a central part of learning within (most forms of) the DDL approach, it is really surprising how few have looked at what learners actually do when they are grappling with language using a computer (see Pérez-Paredes et al., Reference Pérez-Paredes, Sánchez-Tornel and Alcaraz Calero2012 for some interesting insights). With a direct interface between the learner, the patterns on a computer screen, coupled with facilities for screen- and voice-capturing and eye-tracking, DDL has a major role to play in addressing this lacuna in this area of SLA research. We are in a position to investigate questions around form, attention, noticing and salience. For instance: What is the nature of attention in DDL? What is the nature of noticing in DDL relative to key variables (e.g. level, form (lexical versus grammatical), degree of exposure, etc.)? What is the optimum type/frequency of exposure within DDL? Which format of DDL fosters greater learner attention? What is the relationship between form and attention (are some forms more noticeable)? What is the impact of type of corpus data on attention (curated and differentiated data matching the level of the students versus large corpora)? What is the impact of pre-instruction on noticing and attention in DDL?

Within this type of exploration, we have scope to investigate the relationship between noticing, attention and form. The question of whether certain forms are more noticeable, and thus subconsciously learnable, can be examined through eye-tracking attention experimentation as exemplified in Cintrón-Valentín and Ellis (Reference Cintrón-Valentín and Ellis2015) and Indrarathne et al. (Reference Indrarathne, Ratajczak and Kormos2018). Of importance to DDL researchers, as Indrarathne et al. (Reference Indrarathne, Ratajczak and Kormos2018) note, many within the field of SLA have examined the connection between successful acquisition of lexical knowledge and multiple exposure in reading through eye-tracking experimentation but far fewer look at syntactic constructions. For DDL, this type of research could also tie in with a number of established SLA concepts. For instance, input enhancement (Sharwood Smith, Reference Sharwood Smith1981; Chapelle 2003; Wong, Reference Wong2005), which refers to the making salient of selected language items so as to bring learners’ conscious attention to them. DDL, with its use of key word in context (KWIC) formats, offers an obvious testbed for degrees of input enhancement (from purely concordance level to teacher mediation). Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019) make the connection between engagement with concordances and higher involvement, which, in line with Laufer and Hulstijn's Involvement Load Hypothesis, makes learning lexical items easier because the learner is more engaged with the item of focus within a concordance line. For DDL researchers, this is another area waiting to be explored more extensively, especially in relation to grammatical constructions and patterns.

Exploring the nature of learner cognition is central to our understanding of notions of exposure, attention, noticing, input enhancement and involvement load. The question of whether cognition operates at a conscious or subconscious level is part of a long-running SLA debate relating to the nature of the connection between conscious explicit processes and subconscious implicit processes of learning, especially the degree to which learners’ attention should be focused on form versus meaning. This debate also ties in with the widely held UB model of SLA (Ellis, Reference Ellis2002), discussed further in Section 4.2.

4.2 DDL and the Interface Debate

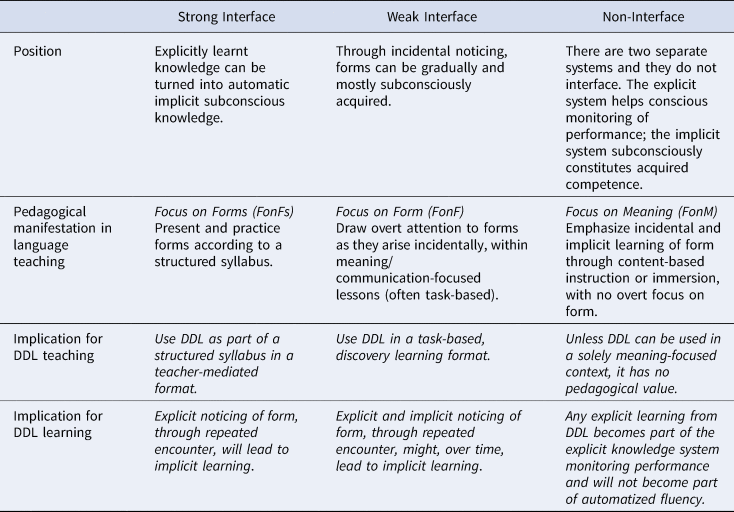

Let us now consider this fundamental debate that has dominated instructed SLA for over 20 years, namely the Interface Debate. DDL has kept its eyes averted from it but it is time to engage. The Interface Debate ultimately relates to whether the brain works on a conscious or a subconscious level (or both) in the process of learning. Subconscious learning is referred to as implicit while conscious overt learning is referred to as explicit (Graus & Coppen, Reference Graus and Coppen2016). The long-running debate centres on the question of whether there is any interface, or connection, between the explicit and implicit knowledge systems. Core to this, in terms of instruction, is the issue of whether explicit and consciously taught (or learnt) knowledge can ever be internalized by learners to become part of the implicit automatized subconscious knowledge system. It is the automatized subconscious system which is the basis of long-term and fluent language use (Han & Finneran, Reference Han and Finneran2013; Graus & Coppen, Reference Graus and Coppen2016).

This debate has given rise to three overall positions within the field of instructed SLA (Han & Finneran, Reference Han and Finneran2013; Graus & Coppen, Reference Graus and Coppen2016), namely strong, weak and non-interface positions. These three positions, in turn, manifest in three different stances on the teaching of language forms. These are (respectively): FonFs, FonF and FonM (Focus on Meaning), as Table 1 summarizes. Each of these three positions has a distinct implication for DDL in terms of its pedagogical underpinning, ranging from discovery to mediated manifestations (and these are summarized in the shaded cells in Table 1).Footnote 2

Table 1. Three main positions in the Interface Debate and how they relate to pedagogical underpinnings (Strong Interface, Weak Interface, Non-Interface)

From a pedagogical perspective, the strong position aligns well with a teacher-mediated form of DDL, linked to an external syllabus, manifesting in a FonFs approach where form is given overt focus. Within this view, DDL would support explicit noticing through repeated encounters with a given form. Ideally, this would lead to implicit learning.

The weak position, which foregrounds the importance of subconscious engagement with language as the driver of learning, has gained much attention (Graus & Coppen, Reference Graus and Coppen2016; R. Ellis, Reference Ellis2006, Reference Ellis2016). It ties in with the UB model of first and second language acquisition (Ellis, Reference Ellis and Rebuschat2015; Tyler & Ortega, Reference Tyler and Ortega2016). If the weak interface position holds true, then there are implications for the classroom. From an FonF perspective, there is a need to take a more subtle approach so as to incidentally focus on form as part of a process that also engages subconscious implicit learning. According to Long (Reference Long, de Bot, Ginsberg and Kramsch1991, pp. 45–46), this can involve the overt drawing attention to elements of form ‘as they arise incidentally in lessons’ but the ‘overriding focus is on meaning or communication’. Within the weak position, there is discussion and divergence in relation to the role of attention and whether learning springs primarily from a conscious or a subconscious process (see Han & Finneran, Reference Han and Finneran2013; R. Ellis, Reference Ellis2006, Reference Ellis2016). Crucially for DDL research and practice, this further underscores the need to consider the role, nature and frequency of exposure to a new language form.

From a cognitive perspective, within the UB model, based on many years of empirical work on first language (L1) acquisition and latterly SLA, N. Ellis (Reference Ellis2006) argues that frequent exposure to constructions contributes to models of associative cognitive learning. Within this process, learners establish or encode form-meaning mappings or associations (Ellis, Reference Ellis and Rebuschat2015; Indrarathne et al., Reference Indrarathne, Ratajczak and Kormos2018). Proponents of a UB model, N. Ellis, and his associates, for instance, envisage a process whereby learners intuitively identify and organize constructions or form-function mappings based on their probabilistic encounters with relevant exemplars in the communicative environment (Ellis, Römer, & O'Donnell, Reference Ellis, Römer and O'Donnell2016). Ultimately, while the process of learning involves conscious attention and noticing of constructions and form-function mapping, the internal reorganizing of one's system of knowledge of the language is done at a subconscious or implicit level (see Han & Finneran, Reference Han and Finneran2013, p. 373). As noted by Reference Pérez-Paredes, Mark and O'KeeffePérez-Paredes, Mark & O'Keeffe (In Press), within this view of language learning, learners first abstract constructions from meaningful input and then gain understanding of the relationships between constructions. Learning is largely determined by frequency of exposure to new language – the more often constructions are experienced and understood together, the more entrenched they become. Therefore, it is predicted that learners subconsciously acquire first the constructions that they encounter most frequently in the input that they receive. This theory has obvious relevance for DDL and holds a lot of potential for further exploration, as we discuss in Section 4.3.

The third position of non-interface derives from a Chomskyian view and sees no connection between conscious and subconscious learning. The work of Krashen (Reference Krashen1991) promotes the idea that for adult learners of a second language, there are two possible learning paths and they do not interface (see Han & Finneran, Reference Han and Finneran2013). Firstly, learning can be a conscious process resulting in explicit declarative knowledge that can be drawn upon in performance of language and, secondly, learning can happen subconsciously and this becomes deep-set implicit knowledge and part of the learner's store of language competence. From this perspective, one can consciously learn and explicitly know a form (or other knowledge or skills) and this can be explicitly assessed but this has no bearing on learning at a subconscious level. From the non-interface position comes the notion that teaching should not overtly focus on form in the classroom but rather on meaning (i.e. meaning-focused instruction). From this stance, DDL could only be incorporated pedagogically if it had a meaning focus and any learning that might result from it would remain in the realms of the explicitly learnt knowledge system. This linguistic knowledge could be used in (self-) monitoring of performance but would not become part of automatized fluency (it would be interesting to test this using DDL).

Crucially, this much debated form- versus meaning-focused instruction motif is not found in the discourse of DDL research. Given the fundamental nature of noticing of form, either implicitly or explicitly, within the process of looking at concordance lines and patterns of language, DDL is perfectly-positioned to contribute much to this debate through experimentation. By blithely assuming that noticing leads to some kind of learning, in some cases, we are missing out on many research questions that DDL-based studies could address, as we shall now discuss.

4.3 New opportunities for DDL research

Let us attempt to evolve a research purview where DDL can make some important empirical contributions to SLA research questions, across a number of outcome variables. By designing research studies that can control for variables such as degree of mediation and cognitive processes across variables such as level of competence, L1, language form, implicit/explicitness of the learning format and type of corpus data, our research could offer more fine-grained results through careful experimentation. This might require the DDL research paradigm to expand beyond quasi-experimentation in the classroom and to avail more of instruments which capture screen activity, eye movement, private and peer speech and so on. This could offer endless opportunities for gaining insight into areas such as noticing and attention in relation to multiple encounters with constructions. With a more longitudinal focus, it would also allow for exploration around which language forms at which levels of proficiency might be more learnable. For example, it could test assertions within the UB model of acquisition that point to a movement from the acquisition of low scope morphemes, words and constructions that have basic meaning to more abstract and productive ones as learners gain proficiency. With such a focus, DDL could be contributing to studies that tie in with cutting-edge issues in instructed SLA. For instance, current emerging learner corpus work on the acquisition of Verb Argument Constructions (VACs) could be enhanced by DDL-based explorations (see, for example, Römer, Reference Römer2019).

It is also time for DDL empirical work to move towards a research design which will investigate the long-held assertions that it enhances learning processes. As discussed, given the micro-interface of DDL with the learner (through screens), it seems a missed opportunity that within the meta-analyses of DDL research of the last three decades, we find no aggregation of work on what has been learnt about the mechanics of acquisition and instruction. DDL has the potential to explore and test tenets of the differing positions within the FonF(s) versus FonM debate. However, there are two critical changes required. Firstly, there is a need to devise a more robust means of capturing longitudinal data (especially in relation to the administration of delayed post-tests, as noted by Lee et al., Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019). Most studies only conduct post-tests immediately after the test period of the DDL intervention and the control groups but if we are to gain insight into implicit learning, delayed post-tests are essential to exploring what has been implicitly learnt (Han & Finneran, Reference Han and Finneran2013). Secondly, there is a need to expand our research design so that we can capture data on cognitive processes through eye-tracking, screen and voice-capturing as well as learner protocols. These data will inform us on the nature of attention, noticing and salience. They will also capture data on learning processes and degrees and effects of mediation, from self to other.

As Figure 2 illustrates, a broader research perspective can bring focus to many exciting research questions.Footnote 3 By digging deep into research questions across the variables of cognitive processes and degrees of mediation, we can examine research questions on the cline from a constructivist to a more SCT-focused type of DDL, relative to key variables such as level of student competence, L1, language form (being either discovered or investigated), degree of implicitness or explicitness of learning and the degree to which data is curated for the purpose of learning. Other variables such as learners’ pedagogic culture, year of study, etc., could be included. It can also bring our focus to contemporary questions emerging from learner corpus research about UB models of SLA (Ellis, et al., Reference Ellis, Römer and O'Donnell2016).

Figure 2. A broader research framework for DDL

Learner corpora increasingly are being explored so as to identify the process of construction development across levels of competence. Römer (Reference Römer2019) offers an interesting example of this type of research. She explores, using learner corpora, the type and nature of VACs produced by German English language learners at different levels of competence (based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages). Insights from work such as this could be tested pedagogically. For example, through experimentation, DDL could be explored as a means of increasing exposure to VACs both through explicit (overt) and implicit (covert) means. Within this focus, we could explore cognitive processes and outcomes when corpora are used to ‘accelerate’ language experience or exposure. There are many variables that could be investigated in such research, for example, the role of L1 in terms of developmental and transfer errors; the role of meaning in terms of the types of data that is curated for learners, the nature of learning (implicit or explicit) and degree of learning relative to level of proficiency; the degree of mediation (teacher- or peer-led) relative to learning, and so on. There are challenges in doing this kind of research not least of all in finding an appropriate methodology but the tools are there and are already widely used in SLA studies (e.g. recall protocols, journaling, screen capturing, eye-tracking).

5. Conclusion

As I have discussed, while there is clear evidence of vibrant research on DDL often leading to successful learning outcomes, this paper argues that there is a need for greater critical engagement with the pedagogical underpinnings in the form of theories of learning and theories of language acquisition (see also Pérez-Paredes, Reference Pérez-Paredes2019). While we need to continue and improve on pre- and post-testing in quasi-experimental studies (and meta-studies such as Boulton and Cobb (Reference Boulton and Cobb2017) and Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Warschauer and Lee2019) offer us much by way of how the future studies can be enhanced), we also need to add new research questions and explore new methodologies as well. Informed by learning and acquisition theories, DDL research has an important role to play by feeding into and informing the wider SLA research community. Its results can have a far-reaching impact. From the perspective of how we learn languages, DDL can help us gain a refined view on some important outcome variables, including the role, nature and degree of mediation in form-focused instruction. Within the field of SLA, there are so many exciting research questions being asked in relation to noticing, attention, salience, UB acquisition of constructions, to name but a few. DDL can add to this body of work from the perspective of individual learners by enhancing our understanding of the cognitive processes that second language learning entails within DDL. We can also learn more from those who mediate learning: the teachers, the peers and the self. Now is the time to shift our gaze. We will see more in the process of adopting a more pedagogically aware and SLA-focused approach to researching DDL and by doing so we can open up opportunities for SLA to use DDL within its methodological repertoire.

Dr Anne O'Keeffe is Senior Lecturer in Applied Linguistics, at the Department of English Language & Literature, Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick, Ireland. She has written numerous books and papers on corpus linguistics, language teaching and pragmatics, including From corpus to classroom (CUP, with Michael McCarthy and Ronald Carter). English grammar today (CUP, with Ronald Carter, Michael McCarthy and Geraldine Mark), Introducing pragmatics in use (2nd ed. 2020, Routledge, with Brian Clancy and Svenja Adolphs). She also co-edited the Routledge handbook of corpus linguistics (with Michael McCarthy) and is currently curating its second edition. She was co-principal investigator of the English Grammar Profile, a research project commissioned by CUP which explored the Cambridge Learner Corpus so as to build an online grammar competency framework resource. She is co-editor of Routledge book series: Routledge Corpus Linguistic Guides and Routledge Applied Corpus Linguistics Series. She has also guest edited a number of international journals, including Corpus Pragmatics, International Journal of Corpus Linguistics and Language Awareness. Dr O'Keeffe is also founder and coordinator of the Inter-Varietal Applied Corpus Studies research centre and network.