1. Introduction

This paper begins with a brief discussion of the overarching task of developing a model of LBC that can underpin research in the field. It then proposes a number of research tasks that we believe will help move research on LBC forwards. These tasks are organized under three headings: Settings, Learning processes, and Teaching. These headings correspond to three basic questions in LBC research to which we do not as yet have clear answers: Where does LBC take place? How does it take place? How should teachers be involved?

2. Modelling LBC

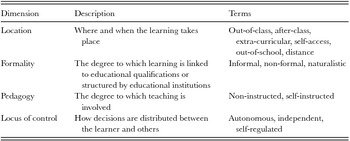

LBC has been identified by a variety of names, including: out-of-class, after-class, extra-curricular, self-access, out-of-school and distance learning; informal, non-formal and naturalistic learning; non-instructed learning and self-instruction; autonomous, independent, self-directed and self-regulated learning. These terms point to a number of dimensions of LBC that need to be untangled in order for LBC to become a coherent field of research. The development of a coherent descriptive model that can help us to separate out the different forms and dimensions of LBC is an overarching research task, to which data based studies in particular areas of LBC have much to contribute.

In educational research, Schugurensky's (Reference Schugurensky2000) model identifies three main forms of ‘informal learning’, which are distinguished by degree of intentionality and conscious awareness: ‘Self-directed learning’ is conscious and intentional; ‘incidental learning’ is conscious but not intentional; ‘socialization’ is both non-intentional and below the level of conscious awareness. While this model is often cited in the literature, its terminology is somewhat confusing. Informality is only one dimension of LBC, and the key terms of the model are linked to other terms that are not accounted for (e.g. ‘self-directed’ with ‘other-directed’, ‘intentional’ with ‘incidental’).

Benson's (Reference Benson, Benson and Reinders2011) preliminary model of LBC identifies four main dimensions based on four of the more cited oppositions in the literature: location (out-of-class vs classroom), formality (informal vs formal), pedagogy (non-instructed vs instructed) and locus of control (‘self-directed’ with ‘other-directed’). Table 1 includes a brief description of each dimension with terms used to describe LBC that correspond to them.

Table 1 Dimensions of LBC (Benson Reference Benson, Benson and Reinders2011a)

This model provides a basic framework for analysing participation in a particular LBC activity. Table 1 shows that, although LBC essentially refers to location, location is, in fact, only one of several dimensions of LBC. After identifying the location in which learning takes place, we may then determine whether the learning is informal or formal, non-instructed or instructed, self-directed or other-directed (bearing in mind that each distinction has its own complexities and should be treated as a matter of degree). Chik's (Reference Chik2014) study of digital gaming and Lai, Zhu & Gong's (Reference Lai2015) study of the quality of out-of-class learning illustrate how this model can be used in the analysis of data on LBC.

Benson's (Reference Benson, Benson and Reinders2011) model is rudimentary, however, and clearly in need of further development. Chik (Reference Chik2014) added a temporal dimension to the model, concerned with the ‘trajectory’ of a learner's engagement in a particular form of LBC. Lai et al. (Reference Lai, Zhu and Gong2015) also consider variety of activities and the degree to which they are meaning focused as factors in the quality of LBC. Other important dimensions may include: mediation, or the resources used in learning (teaching and learning materials, authentic texts, technologies, etc.); sociality, or the social relationships and networks involved in the learning process; modality, or the learning practices engaged in (e.g., language study, or language use: reading, listening, spoken or written interaction); and a linguistic dimension, concerned with the language skills and levels of language competence involved in LBC.

Three additional dimensions refer more to learning processes that may be characteristic of LBC:

-

a. Whether the learning is intentional (attention focused on language learning) or incidental (attention focused elsewhere with language learning as a by-product) (DeKeyser Reference DeKeyser, Doughty and Long2008).

-

b. Whether the learning is explicit (adds to the learner's conscious knowledge) or implicit (adds to abilities or skills that lie below the level of conscious awareness) (Ellis Reference Ellis, Cenoz and Hornberger2008).

-

c. Whether the learning is inductive (inferencing general rules from particular instances) or deductive (applying general rules to particular instances).

Modelling LBC is clearly a long-term task. We are only beginning to understand how the terms that describe LBC map on to its different dimensions, and still less how these dimensions are connected with each other. Any study of LBC in a particular context could profitably begin from a clear exposition of where the activity in focus stands in relation to the various dimensions of LBC identified in this section.

3. Settings for LBC

At this early stage of research, it is important to develop our knowledge of the settings for LBC that are typically available to learners. Research tasks 1–3 are, therefore, concerned with documenting settings for LBC and the uses that learners make of them. These tasks are designed for researchers and teachers to carry out in the contexts in which they work.

3.1 LBC Environments

The term LBC covers a variety of settings that are defined, negatively, as being not ‘in the classroom’. One way of making sense of these settings is to view them as potential elements within broader ‘social ecologies’ of language learning (Kramsch Reference Kramsch2002; van Lier Reference van Lier2003; Palfreyman Reference Palfreyman and Murray2014). From this perspective, LBC does not exclude the classroom but rather connects with it. For example,

-

• Classroom learners can also engage in learning beyond the classroom.

-

• Autonomous learners can take classroom-based language courses.

-

• Self-study learners can use textbooks designed for classroom use.

The classroom is, thus, likely to be one of a number of settings that make up the affordances for, and constraints on, language learning within a broader environment. At present, however, we do not have an adequate understanding of how these settings blend in particular contexts of learning and teaching. There is also much to be done to build on innovative work that examines how students make use of the varied opportunities for LBC in their environments and connect these to classroom learning.

One study that addresses these issues is Lamb's (Reference Lamb2004) investigation of the English language learning of junior high school students in a provincial Indonesian city. Lamb explored relationships between the students’ learning in the classroom, after-school lessons at school and in private institutions, and their use of resources in their everyday environments outside school. He found that much of their learning took place outside school English classes, but that these classes were, nevertheless, important, due to the relationships that students established with teachers, rather than lesson content. Lai's (Reference Lai2015) study of Hong Kong undergraduate language learners investigated attitudes to in-class and out-of-class learning. It found that the students valued both but allocated different functions to them, which influenced their expectations of classroom teaching.

Research task 1

Document the settings and resources for LBC that are available to a group of learners with which you work. Analyse how they make use of these settings and resources and how they connect them with classroom learning.

This task can be carried out through ethnographic observation (e.g. Lamb Reference Lamb2004) or a questionnaire based on the researchers’ evaluation of available resources (Lai Reference Lai2015). However, LBC clearly can take place in many different settings, some of which may be private and some of which may not even be recognised by learners as contexts for learning. For this reason, a combination of methods is recommended and it is important that any instruments used make it clear that the researcher is interested in all forms of learning, not simply those that the participants may think the researcher is asking about. To understand what kinds of settings learning takes place in, quantitative methods such as the use of surveys can be helpful. And to understand how participants use different settings for their learning, further, in-depth information will need to be obtained. Ethnography involves the researcher observing learning from the point of view of the participant (as much as possible) and in the participant's context (as opposed to, for example, a laboratory setting). Observations over longer periods of time allow different types of learning behaviour to emerge, and a rich description of the environment (including the place, other learners, resources) helps to understand the affordances for learning in different contexts, as well as which aspects of language (e.g. vocabulary, pragmatics) are most likely to be learned in them. For any particular group of learners, the issues of interest will be (a) the configuration of settings and resources that is available, (b) the affordances they offer and constraints on access to them, and (c) the uses learners make of them.

3.2 The affordances and constraints of LBC

In addition to broad studies of the settings and resources for LBC that are available to particular groups of students, there is also an important role for in-depth studies of particular settings. Our knowledge of the variety of settings for LBC has increased considerably in recent years through studies that have focused on, for example, language ‘cafés’ in educational institutions (Murray, Fujishima & Uzuki Reference Murray, Fujishima, Uzuki and Murray2014), self-organized communities or ‘English corners’ (Gao Reference Gao2007, Reference Gao2009), face-to-face or Skype tutoring in the home (Barkhuizen Reference Barkhuizen, Benson and Reinders2011; Kozar & Sweller Reference Kozar and Sweller2014), independent learning in the home (Kuure Reference Kuure, Benson and Reinders2011; Palfreyman Reference Palfreyman, Benson and Reinders2011) and heritage language learning in the community (e.g. Back Reference Back2013; Moore & MacDonald Reference Moore and MacDonald2013). There are also a growing number of studies of language learning in online settings, for example, ‘fan fiction’ (Black Reference Black, Knobel and Lankshear2008), digital gaming (Chik Reference Chik2014) and online TV dramas (Wang Reference Wang2012).

Studies of these kinds not only extend our knowledge of the range of affordances for LBC, they can also contribute to theory on the roles of learning spaces and social networks in learning. Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Fujishima, Uzuki and Murray2014), for example, draw on theory from human geography and mediated discourse analysis, to discuss what they call the ‘semiotics of place’ in LBC in relation to a university facility in Japan that they describe as a ‘social learning space’. They argue that the ways in which students imagine, perceive and define a space determines what they do in it and influences their autonomy within that environment. Palfreyman (Reference Palfreyman, Benson and Reinders2011), on the other hand, draws on social network theory to explore how female English language students in the United Arab Emirates draw on networks of family and friends to organize their learning in the home.

Research task 2

Conduct an in-depth study of how one emerging setting is used for LBC by an individual or small number of language learners.

In contrast to Research task 1, which focuses on the settings that make up a particular LBC environment, this task focuses on a particular setting within the environment that is used by some, but not all learners. Because of this narrower focus it is best carried out with an individual or a small number of learners, and data might be collected through retrospective interviews on the learners’ experiences of learning in the setting or concurrent observation of their learning practices. Chik's (Reference Chik2014) study of digital gaming, for example, included interviews and ethnographic observation and, in addition, data was gathered from an online forum thread on language learning and gaming. Studies of this kind often begin from the researchers’ own everyday interests or from noticing an interesting setting for LBC that a particular learner is using. There are many undocumented settings for LBC, especially online, and those that have been mentioned here are under-researched. Studies of particular settings can also contribute to the theory of LBC, especially if they focus on the nature of the setting as an LBC ‘space’ and the social networks involved in learning.

3.3 Study abroad

Study abroad is a well-researched area that often involves both classroom learning and LBC (Kinginger Reference Kinginger2009). As a context for LBC, it deserves special attention, partly because it is often the opportunities for immersion in out-of-class target language use that is most valued in study abroad and partly because the affordances for LBC are often very different to those available in the home environment. Studies have also found, however, that access to opportunities to use the target language, especially with native speakers, are often constrained and largely confined to language classes (Cotterall & Reinders Reference Cotterall and Reinders2001). In one recent study, Trentman (Reference Trentman2013) found that American students studying in Egypt used English more than Arabic, partly because of the difficulty of accessing native speakers of Arabic and partly because they tended to use English even when talking with Arabic speakers. At present, however, we know relatively little about the ecologies of particular study abroad environments. In particular, we know little about homestay and other LBC settings that are unique to study abroad. Emerging qualitative research has, however, begun to cast light on the part that learners play in constructing their own LBC environments in study abroad (Benson Reference Benson, Chan, Chin, Bhatt and Walker2012; Benson et al. Reference Benson, Barkhuizen, Bodycott and Brown2012) and the kinds of learning and teaching that occur in homestays (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2002; Zimmermann Reference Zimmerman, Benson and Reinders2011).

Research task 3

Document and analyse the configuration of LBC settings in a particular study abroad programme and the uses that students make of them.

This task is similar to Research task 1 in that it involves both documenting the settings and resources in a learning environment and examining how students make use of them. However, this task would be best carried out through in-depth study of the experiences of individual students, both because students tend to construct their own learning environments in study abroad and because it is important to understand how study abroad represents a change from the learning environment that the student is accustomed to at home. Data collection methods might include retrospective interviews and concurrent learner diaries. In the past, it has been difficult for researchers from the students’ home countries to gather data from them while they are studying abroad and new methods such as Skype interviewing and photo-blogging are worth exploring. Benson's (Reference Benson, Chan, Chin, Bhatt and Walker2012) individual case study of a Hong Kong student's study abroad environment in an Australian city relied on a retrospective interview based on the student's photo-blog, and would have been considerably enhanced if it could have been carried out in collaboration with a researcher in the host city. Audio-recordings of spoken interaction also proved to be a valuable source of data in Wilkinson's (Reference Wilkinson2002) and Zimmermann's (Reference Zimmerman, Benson and Reinders2011) homestay studies. While homestay remains an under-researched setting, there are also other important study abroad settings that have barely been investigated at all, including interactions with ‘study buddies’, interactions with strangers in the street and public transport, and, in longer-term study abroad, part-time jobs.

4. How do learners learn beyond the classroom?

4.1 The experience of LBC

The ways in which learners approach, structure and feel about their experiences of LBC are of particular interest in that they are both reflective of, and – in as yet largely unknown ways – cause of learners’ motivation, attitudes and their sense of identity as language learners or users. To understand the contribution that LBC makes to learning, it is therefore crucial to understand how LBC relates to the learner. There are several approaches to exploring this profoundly personal aspect of learning, for example, through the use of ‘language learning histories’, or accounts of how individuals go about learning languages over relatively long periods of time (Benson & Nunan Reference Benson and Nunan2005), often covering what Benson (Reference Benson2011b) calls their language learning ‘careers’. Language learning histories that cover the whole period from beginning to learn a language to achieving a high level of proficiency in it (e.g., Benson, Chik & Lim Reference Benson, Chik, Lim, Palfreyman and Smith2003) typically have two important characteristics. First they show how, both concurrently and sequentially, language learning tends to involve in-class and out-of-class learning experience. For example, many individuals begin learning a language mainly in the classroom, gradually accumulate LBC experiences, and later in life continue learning, often ‘naturalistically’, without attending classes. In Benson et al. (Reference Benson, Chik, Lim, Palfreyman and Smith2003), this pattern was observed to be typical for Asian learners who become proficient in English, but other patterns might well be observed for learners of other languages in other parts of the world (see, for example, Kalaja, Barcelos & Menezes Reference Kalaja, Barcelos and Menezes2008). Second, they show how, in the longer term, learning a second or foreign language is not simply a matter of learning the forms and structures of the language or even of learning how to use it to communicate; it is also a process that is tied in with the development of identity (Block Reference Block2007; Benson et al. Reference Benson, Barkhuizen, Bodycott and Brown2012). While any engagement with a new language, arguably, leads to a development of identity, Block (Reference Block2007) shows that experiences of classroom learning are in themselves unlikely to have a deep impact on L2 identity, which is far more likely to emerge from critical experiences of using the language outside the classroom in situations that destabilize identity, such as those often encountered by migrants or students abroad.

Although such studies provide fascinating insight into the language learning journey from a learner's perspective, most do not include a linguistic focus and do not (aim to) record the types of input and output the learners engage in and how this relates to subsequent learning. There is a need to better understand how LBC experiences affect both language use in the moment as well as their broader impact on the learner and the learning process. One useful method for this is to apply Critical Incident Analysis. This entails the recording and analysis of events that profoundly shape the learning experience. Such incidents can be purely linguistic insights (‘that was when I finally understood the difference between the active and the passive tense’), or they can be significant affective sources of (de)motivation (‘I felt so embarrassed when those people couldn't understand my accent’). Analysis of such incidents can help to identify underlying causes, their impact on the learner, and their impact on subsequent learning (Tripp Reference Tripp2011).

Research task 4

Use Critical Incident Analysis to identify and deconstruct key experiences in LBC for their potential to inhibit or facilitate the language learning process.

Although Critical Incident Analysis is most commonly used in language teacher education (Farrell Reference Farrell2008), a study such as the above could be used with learners to, for example, draw on reflective writing or stimulated recall to encourage recollection and interpretation (for coverage of stimulated recall, or the use of audio, text or video materials of the learner's language, see Gass & Mackey Reference Gass and Mackey2013). Such a study could look at, for example, the types of (opportunities for) second language (L2) interaction in particular situations, how learners feel about encounters with native speakers, factors affecting their willingness to communicate, or their self-motivation (Macintyre et al. Reference MacIntyre, Dörnyei, Clément and Noels1998), and where they perceive the locus of control to be in such situations (with learners who have a strong internal locus of control having been shown to be more successful in LBC (Bown Reference Bown2006)). Such studies would be particularly valuable in that they can help to identify key enabling (or inhibiting) experiences and ways in which learners could be supported to cope with and learn from them.

4.2 Strategies in LBC

Early research on language learning strategies paid a good deal of attention to the strategies that learners employed beyond the classroom (e.g. Wenden Reference Wenden, Wenden and Rubin1987). Subsequent work has tended towards evaluation of strategy use independently of specific contexts of learning and, in survey instruments such as the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (Oxford Reference Oxford1990), the social and affective strategies that are likely to be most important in LBC are less well developed than cognitive and metacognitive strategies. While there is research on learners’ capacity for strategy use in independent learning (Hurd & Lewis Reference Hurd and Lewis2008), little is known about actual strategy use in LBC and the affordances of different learning environments for (the development of) strategy use. There is much to be learned about out-of-class language learning strategies in the context of approaches that link strategy use to self-regulation and motivation (Vandergrift Reference Vandergrift2005; Tseng, Dörnyei & Schmitt Reference Tseng, Dörnyei and Schmitt2006) There have also been calls for more qualitative research on the use of strategies (Woodrow Reference Woodrow2005; Rose Reference Rose2012). The most important questions that are specific to LBC may be concerned less with cognitive and metacognitive strategies than they are with the social and affective strategies that learners use to create opportunities for LBC and to control communicative interactions (Edwards & Roger Reference Edwards and Roger2015). Benson (Reference Benson2011c) uses the term ‘self-directed naturalistic learning’ to describe situations in which learners set up an activity (e.g. a face-to-face interaction with native speakers in the target language) for the purpose of language learning or practice, but shift their focus away from language learning to the content of the activity once they are engaged in it. The ability to set up such situations is crucial to learners engaging in a range of LBC activities that depend on the learner's initiative to seek out people and resources that can both engage their interests and enhance their language learning. Arnold & Fonseca-Mora (Reference Arnold, Fonseca-Mora, Nunan and Richards2015: 229), for example, describe an English-speaking student studying in Spain who, finding that ‘the need she felt to make herself understood was stronger than the fear of making mistakes’, ‘jumped in’ to conversations with Spanish speakers. Her success is described as being partly due to the fact that she planned and visualized interactions in advance and was ‘proactive’ in finding ways to contact Spanish speakers. Stanley's (Reference Stanley, Nunan and Richards2015: 244) account of her own learning of Spanish also describes how she got out of her ‘comfort zone’ by ‘pushing’ herself into situations where she needed to use the language before she felt ready to do so.

Research task 5

Conduct a case study of a learner's efforts to learn a language beyond the classroom, focusing on the strategies used to identify, take advantage of, and/or create opportunities to learn and use the language. Examine the factors that affect the learner's success in these efforts.

Following Woodrow's (Reference Woodrow2005) call for more qualitative research on strategies, this task is, perhaps, best conducted as a case study, using diaries, observation or interviews to explore individual experiences of strategy use in LBC in depth. This task could be carried out either as a third-person study (Arnold & Fonseca-Mora Reference Arnold, Fonseca-Mora, Nunan and Richards2015) or first-person self-study (Stanley Reference Stanley, Nunan and Richards2015). Interviews might focus on successes and failures in LBC and strategies that worked or did not work. If several interviews are carried out at intervals, they can also address developments in strategy use over time. Edwards & Rogers (Reference Edwards and Roger2015), for example, interviewed a migrant to Australia shortly after arrival and again two years later, and reported interesting developments in his strategies for overcoming anxieties in speaking English concerning listening and control. If learners can be persuaded to keep a diary or journal, recording occasions of LBC and the strategies they use shortly after the event, more immediate recollections can be collected and developments can be observed over time. Diaries are an especially useful tool for self-study and were used to good effect in a recent study of ecological influences on the authors’ strategies in learning Japanese in Japan by Casanave (Reference Casanave2012).

4.3 Technology-enhanced learning

Although technology has the potential to facilitate LBC, it does not necessarily do so (Reinders & White Reference Reinders and White2016). Technology-enhanced learning may cover a wide range of ‘locations’ (e.g. in class, in a computer lab, at home, while moving about), may be more or less formal, can involve teacher instruction or self-instruction and can be highly directed or carried out autonomously. Nonetheless, previous studies have given valuable insight into how learners and teachers draw on technology to support LBC. For example, studies of computer-mediated communication (CMC) have been fruitful in research on instructed second language acquisition, but have also given insight into how learners use CMC in out-of-class settings. For example, Sanders (Reference Sanders2006) showed that out-of-class online chat led to more language production than in-class chat. Noting that most research on negotiation of meaning in L2 interaction had been conducted among L2 users and under experimental conditions, Tudini (Reference Tudini2007) investigated negotiation of meaning in online interactions between learners of Italian and native speakers. In contrast to many earlier studies, she found that negotiation of meaning episodes were often triggered by intercultural issues and often occurred outside the context of interactional repair. Similarly, research on social networking has looked at the ways communities can support L2 learners beyond the language classroom (Lamy & Zourou Reference Lamy and Zourou2013). Learners can derive motivation and affective support from other learners and find opportunities for L2 interaction in meaningful contexts. Social networking also sits well in an ecological view of language learning as it foregrounds the relationships between people as the starting point for interaction and learning. There is some emerging evidence from research that such environments encourage learners to persist in their language studies where otherwise they might have stopped; however, there are also considerable impediments to independent learning (Clark & Gruba Reference Clark and Gruba2010).

Another area of growing interest is the use of digital games as avenues for encouraging L2 use beyond the classroom (Gee Reference Gee2003; Reinders Reference Reinders2012). Reinders & Wattana (Reference Reinders and Wattana2014, Reference Reinders and Wattana2015), for example, looked at the effects of completing game quests on L2 learners’ willingness to communicate. Although there was a degree of instructional intervention in the form of the requirement for students to complete specific tasks, the medium (an online role-playing game) is one that students were frequent users of. By moving their language learning from the more formal classroom environment (as perceived by the students) to one that they engaged in outside the classroom, students reported lower anxiety, greater confidence and higher motivation, all of which translated into increased interaction compared with classroom activities. Recent studies have also started to look at the ways in which learners use digital games to support their learning outside the classroom (Kuure Reference Kuure, Benson and Reinders2011; Chik Reference Chik and Reinders2012; Sundqvist & Sylvén Reference Sundqvist, Sylvén and Reinders2012). Similarly, mobile technologies offer a great deal of potential for the delivery and support of out-of-class learning (Beatty Reference Beatty2013; Pegrum Reference Pegrum2014). Their characteristics of portability, social interactivity, context sensitivity, connectivity and individuality (Klopfer, Squire & Jenkins Reference Klopfer, Squire and Jenkins2003) facilitate the creation of learning opportunities that are distributed, collaborative, situated, networked and autonomous (Reinders, Lakarnchua & Pegrum Reference Reinders, Lakarnchua, Pegrum, Thomas and Reinders2015). These affordances are not fully understood yet, neither is their impact on the type and amount of learning they encourage beyond the classroom, and it is important that more research is carried out. In particular, it is not yet known in what ways learners use technology and which aspects of their LBC they seek to use it for. Do learners use technology to ‘mimic’ classroom learning when engaged in LBC with technology or do they find alternative ways of learning? And what is the relationship between the type of LBC and acquisition? Preliminary evidence shows a considerable effect for type of activity on success in LBC (Lai et al. Reference Lai, Zhu and Gong2015) but research has not looked at the specific affordances of technology in LBC.

Research task 6

Use Social Network Analysis to track the ways learners use technology for LBC in one particular setting (e.g. in an online community, or in an online role-playing game) to identify how learners create opportunities for language learning within them.

Social Network Analysis, or SNA, (Scott Reference Scott2012) is used to identify relationships and social structures in groups and has been applied in sociolinguistics studies. It draws on observations and the collection of online data to graphically display how people are connected. SNA could be applied, for example, to the ways in which L2 learners connect with native speakers online, in what settings, and what factors influence the type and amount of communication that ensues. By combining SNA with recordings and analysis of learners’ interaction (e.g. Kurata Reference Kurata2010), evidence of (the development of) different types of language use can be collected and interpreted on the basis of the type of relationship between interlocutors as well as to identify how certain kinds of interaction lead to more or less L2 input and interaction.

5. How do teachers support LBC?

5.1 Teachers’ beliefs about LBC

Much of what we have written in this paper suggests that teachers should link classroom teaching to their students’ LBC activities. This is supported by the strong interest in the field of language teaching in notions such as learner-centredness and autonomy (Benson Reference Benson2007, Reference Benson2011c), agency and identity (van Lier Reference van Lier2007; Mercer Reference Mercer2011), which bridge classroom and out-of-class worlds and place learners’ interests, experiences and development at the centre of classroom teaching. In practice, however, such links are not commonly made. From the perspective of learners, the classroom is usually only one of several settings in which they carry out their language learning. From the perspective of teachers, the classroom is likely to be seen as central to their students’ learning, with LBC playing a supplementary role as an opportunity to practise or extend classroom learning. Teachers’ beliefs about the relationship between classroom learning and LBC can influence student learning, therefore, especially if they are unaware of what their students do outside the classroom, underestimate the amount of time and degree of engagement with LBC, or fail to capitalise on knowledge and skills that the students bring to class. By prescribing homework or by setting tasks and tests that require preparation outside class, teachers may also reduce the time available for self-initiated LBC. At the same time, through initiatives such as self-access learning or extra-curricular activities, teachers may also create opportunities for LBC in situations where they are lacking or difficult to access outside the school. Relatively little is known about the ways in which teachers encourage, support and prepare students for LBC, how related classroom practices are influenced by teachers’ beliefs, how their beliefs and practices are constrained by curricula (Graves Reference Graves2008), and what effect these factors have on student learning (both in the short term, and in the long term, after the course has finished).

Research task 7

Carry out a mixed method research study that compares survey results of teachers’ beliefs about LBC with observations of classroom practices relating to LBC.

Borg & Al-Busaidi (Reference Borg and Al-Busaidi2012) designed a questionnaire to evaluate teachers’ beliefs on autonomy. The questionnaire included two items on LBC (‘Autonomy can develop most effectively through learning outside the classroom’ and ‘Out-of-class tasks which require learners to use the internet promote learner autonomy’.) Though the levels of agreement with these statements were not reported, extracts from open-ended responses showed that some of the teachers attended to LBC in their teaching. Borg & Al-Busaidi's questionnaire could be adapted to include more questions on teachers’ beliefs about the value and roles of LBC, while observational data on how teachers incorporated students’ LBC into classroom activities would give insight into relationships between beliefs and classroom practices, and teachers’ repertoires of techniques and activities used for bringing LBC into the classroom.

5.2 LBC ‘in the classroom’

Many courses require learners to complete activities that extend coursework to settings outside the classroom, usually in the form of homework assignments. Some such activities merely require learners to do things outside the classroom, such as read a book, watch a movie, or interview a speaker of the target language. Others are more extensive and use projects that have a major impact on the shape of the curriculum and what happens in class. In one recent study, Chang et al. (Reference Chang, Wall, Tare, Golonka and Vatz2014) observed that educational research had shown how positive attitudes to homework are linked to higher achievement, but the relationship between time spent on homework and outcomes is inconsistent. Their study of homework in intensive foreign language courses for adults revealed a negative correlation between time spent on homework and course outcomes, which they suggested might be because the time spent on assigned homework reduced the time available for unassigned individualized study.

Although they are less common than homework, out-of-class projects have received more attention over the years. Legutke pioneered efforts to use project work outside the classroom by having German learners of English interview travellers at Frankfurt airport (Legutke & Thomas Reference Legutke and Thomas1991; see also Knox Reference Knox, Burns and da Silva Joyce2007). Linguistic landscape research has also inspired LBC projects in which learners observe and analyse language they observe on the street (Rowland Reference Rowland2013; Chern & Dooley Reference Chern and Dooley2014). Chern & Dooley, for example, take young learners on ‘literacy walks’ in the streets of Taipei to observe and photograph examples of English signage. Their project combines out-of-class excursions with explicit teaching, because, they argue, ‘merely immersing students in print is inadequate’. An important difference between project work and homework is that, while the homework typically extends in-class work to LBC, out-of-class project work brings LBC into the classroom. While there are a number of published accounts of such projects, they tend to be descriptive and there is a need for more studies that describe, analyse and evaluate the impact of innovative project work on learning and classroom activities.

Research task 8

Carry out an action research project in which you design and evaluate an out-of-class learning project for a group of learners that you teach.

Action research is an approach to research that allows teachers to both design and evaluate the impact of an innovation. In this case, the out-of-class project could be inspired by projects reported in the literature or designed by a teacher according to the affordances in the local environment. Ideally, an evaluation of an innovation in teaching and learning would assess its impact on language proficiency. However, it can be difficult for practitioners to set up a control group, who do not participate in the innovation, for comparison. In addition, pre- and post-tests of proficiency typically fail to show significant differences over short periods. For this reason, action researchers tend to look for internal evidence of learning. For example, learners may be asked to keep a learning log in which they regularly record their learning activities and the amount of time spent on them, and document language that they have learned, challenges they experience and their thoughts and feelings about the project. Teacher-researchers should also keep their own field notes, including observations of student motivation and engagement, learning outcomes and the impact of the project on classroom life. The objective would be to produce a rich qualitative data set that could be used to improve the project in the future. Although it is often impractical to set up a control group, interesting comparisons can be made if the innovation is preceded by similar observations over a period in which the learners’ assigned LBC activities are limited to homework tasks.

5.3 Preparing learners for LBC

There are a variety of ways to develop learners’ ability to engage in LBC, from classroom-based activities, to alternative forms of ‘learner support’. Classroom-based methods include short courses (where the focus is on developing skills for independent learning and raising students’ awareness of the importance of learning outside the classroom) (Rubin & Thompson Reference Rubin and Thompson1994; Rubin Reference Rubin and Griffiths2008). Other, common forms of learner support include language advising (Reinders Reference Reinders2007; Mynard & Carson Reference Mynard and Carson2012). There are relatively few accounts, however, of classroom-based programmes or initiatives that are specifically designed to help students with LBC. One interesting example of such a study is Ryan's (Reference Ryan, Benson and Voller1997) account of a course for adult English language learners in Japan that involved research into the English language learning resources available in the local environment, training on strategies to use them for language learning, and activities to raise awareness of the language learning principles that underlie these strategies. As in the case of LBC projects, however, there is a need for accounts of strategy or learner training initiatives to incorporate a stronger element of evaluation.

Research task 9

Carry out an action research project in which you design and evaluate an initiative or programme to help students make better use of the resources for LBC in their local environments.

This project would ideally follow Research task 1 (a survey of the resources available in a particular environment) as well as a survey, using a questionnaire or interviews, to establish the students’ interests and perceptions of their needs. As this is an action research project, the methods of data collection would be similar to those used in Research task 8, although the emphasis in this task should be on the impact of the classroom programme on LBC, rather than the LBC work itself. Language learning logs and the teacher-researchers’ field notes would provide evidence of the students’ uptake of training provided in the programme. If the programme specifically involves learner strategy training, pre- and post-project questionnaires could be designed to evaluate students’ perceptions of how relevant the strategies covered by the programme were to their learning outside the classroom. Interviews with a selection of students (including those who appear to have benefited most and least from the programme) could also be conducted to provide insight into the particular challenges that students face in putting the principles and techniques taught in the classroom in practice in actual contexts of LBC.

6. Conclusion

This paper has attempted to set a research agenda for LBC that addresses three main areas: settings for LBC and the affordances and constraints that they offer, the processes involved in LBC, and the roles that teachers can play in supporting LBC. This research agenda is a broad one, and necessarily so, not only because LBC is a relatively new area of interest in a field that has, hitherto, paid much more attention to learning in classrooms but also because opportunities for LBC are multiple, dynamic and highly dependent on the language being learned and the context of learning.

At the start of this article we argued that LBC is not just a matter of learning away from the classroom but is rather, in many cases, an extension of classroom learning. Increasing our attention to LBC may, therefore, lead to a realisation that the classroom is less the centre of most learners’ learning, than just one of many centres. Changes in technology (in particular mobile-assisted language learning) and a shift of attention to the learner as an active agent in his or her learning, make it all the more important that we deepen our understanding of the relationship between LBC and learning in or from the classroom. We argue that this deeper understanding will lead to a reconceptualisation of the classroom as a ‘third space’ (Kramsch & Steffensen Reference Kramsch, Steffensen and Hornberger2008), created by learners and teachers in a dynamic and interactive manner, based on learners’ individual experiences. This reconceptualisation will lead to a much more fluid, dynamic view of the classroom as one node (albeit an important one) in an interconnected web of learning opportunities. It is vital that future research places greater value on the role of the individual learner. Looking at his or her life and learning outside the classroom is an excellent starting point.

Hayo Reinders (www.innovationinteaching.org) is Professor of Education and Head of Department at Unitec in New Zealand and Dean of the Graduate School at Anaheim University in the United States. He is also Editor-in-Chief of the journal Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching (Taylor & Francis). Hayo's interests are in educational technology, learner autonomy, and out-of-class learning and his most recent books are on teaching methodologies, digital games, and second language acquisition. He edits a book series on ‘New Language Learning and Teaching Environments’ for Palgrave Macmillan.

Phil Benson is Professor of Applied Linguistics at Macquarie University, with more than 30 years’ experience of language teaching and teacher education in North Africa, the Middle East, East Asia and Australia. His main interests in teaching and research are in learner autonomy and out-of-class learning. Pursuing these interests has led him into research on long-term narratives of language learning, study abroad, and informal language learning using digital media and popular culture resources. He has a preference for qualitative research methods and is especially interested in narrative inquiry as an approach to language teaching and learning research.