1. Introduction

1·1. Background and main results

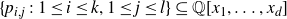

Let

![]() $(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

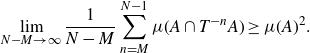

be an invertible probability measure-preserving system. A classical result of Khintchine [

Reference Khintchine31

] says that for any

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

be an invertible probability measure-preserving system. A classical result of Khintchine [

Reference Khintchine31

] says that for any

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

,

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

,

\begin{align*} \lim_{N - M \to \infty}{\frac{1}{N-M} \sum_{n=M}^{N-1}{\mu(A \cap T^{-n}A)}} \ge \mu(A)^2.\end{align*}

\begin{align*} \lim_{N - M \to \infty}{\frac{1}{N-M} \sum_{n=M}^{N-1}{\mu(A \cap T^{-n}A)}} \ge \mu(A)^2.\end{align*}

As a consequence, for any

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

is syndetic, meaning that it has bounded gaps (equivalently, finitely many translates of R cover

![]() $\mathbb{Z}$

). Furstenberg showed in [

Reference Furstenberg22

] that for any

$\mathbb{Z}$

). Furstenberg showed in [

Reference Furstenberg22

] that for any

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

and any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

and any

![]() $k \in \mathbb{N}$

,

$k \in \mathbb{N}$

,

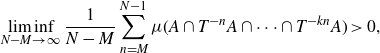

\begin{align*} \liminf_{N - M \to \infty}{\frac{1}{N-M} \sum_{n=M}^{N-1}{\mu(A \cap T^{-n}A \cap \dots \cap T^{-kn}A)}} > 0,\end{align*}

\begin{align*} \liminf_{N - M \to \infty}{\frac{1}{N-M} \sum_{n=M}^{N-1}{\mu(A \cap T^{-n}A \cap \dots \cap T^{-kn}A)}} > 0,\end{align*}

from which it follows that

is syndetic for some

![]() $c > 0$

. One may ask, for these longer expressions, if c can be made arbitrarily close to

$c > 0$

. One may ask, for these longer expressions, if c can be made arbitrarily close to

![]() $\mu(A)^{k+1}$

. (By considering weakly mixing systems, it is clear that c cannot exceed

$\mu(A)^{k+1}$

. (By considering weakly mixing systems, it is clear that c cannot exceed

![]() $\mu(A)^{k+1}$

in general.) A somewhat surprising answer was given in [

Reference Bergelson6

]:

$\mu(A)^{k+1}$

in general.) A somewhat surprising answer was given in [

Reference Bergelson6

]:

Theorem 1·1 ([ Reference Bergelson6 , theorems 1·2 and 1·3]).

-

(1) For any ergodic invertible probability measure-preserving system

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu,T)$

, any

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu,T)$

, any

$\varepsilon > 0$

, and any

$\varepsilon > 0$

, and any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, the set (1·1)is syndetic.

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, the set (1·1)is syndetic. \begin{align} \left\{ n \in \mathbb{Z} \;:\; \mu(A \cap T^{-n}A \cap T^{-2n}A) > \mu(A)^3 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align}

\begin{align} \left\{ n \in \mathbb{Z} \;:\; \mu(A \cap T^{-n}A \cap T^{-2n}A) > \mu(A)^3 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align}

-

(2) For any ergodic invertible probability measure-preserving system

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu,T)$

, any

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu,T)$

, any

$\varepsilon > 0$

, and any

$\varepsilon > 0$

, and any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, the set is syndetic.

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, the set is syndetic. \begin{align*} \left\{ n \in \mathbb{Z} \;:\; \mu(A \cap T^{-n} A \cap T^{-2n}A \cap T^{-3n}A) > \mu(A)^4 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \left\{ n \in \mathbb{Z} \;:\; \mu(A \cap T^{-n} A \cap T^{-2n}A \cap T^{-3n}A) > \mu(A)^4 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align*}

-

(3) There exists an ergodic system

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

with the following property: for any integer

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

with the following property: for any integer

$l \geq 1$

, there is a set

$l \geq 1$

, there is a set

$A =A(l) \in \mathcal{B}$

of positive measure such that for every integer

$A =A(l) \in \mathcal{B}$

of positive measure such that for every integer \begin{align*} \mu(A \cap T^{-n}A \cap T^{-2n} A \cap T^{-3n}A\cap T^{-4n}A ) \leq \frac 12\mu(A)^l \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \mu(A \cap T^{-n}A \cap T^{-2n} A \cap T^{-3n}A\cap T^{-4n}A ) \leq \frac 12\mu(A)^l \end{align*}

$n \neq 0$

.

$n \neq 0$

.

In the terminology of [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

], Theorem 1·1 shows that the families

![]() $\{n, 2n\}$

and

$\{n, 2n\}$

and

![]() $\{n, 2n, 3n\}$

have the large intersections property, while

$\{n, 2n, 3n\}$

have the large intersections property, while

![]() $\{n, 2n, \dots, kn\}$

does not have the large intersections property for

$\{n, 2n, \dots, kn\}$

does not have the large intersections property for

![]() $k \ge 4$

. The combinatorial content, via Furstenberg’s correspondence principle, is that, for arithmetic progression of length 3 and 4, one can find a “popular” common difference: if

$k \ge 4$

. The combinatorial content, via Furstenberg’s correspondence principle, is that, for arithmetic progression of length 3 and 4, one can find a “popular” common difference: if

![]() $E \subseteq \mathbb{Z}$

has positive upper Banach density

$E \subseteq \mathbb{Z}$

has positive upper Banach density

![]() $d^*(E) = \delta > 0$

and

$d^*(E) = \delta > 0$

and

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

, then there exists (syndetically many)

$\varepsilon > 0$

, then there exists (syndetically many)

![]() $n \ne 0$

such that

$n \ne 0$

such that

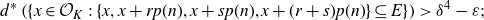

and there exists (syndetically many)

![]() $m \ne 0$

such that

$m \ne 0$

such that

A natural question to ask is whether various extensions of Szemerédi’s theorem also admit large intersections variants.

The polynomial Szemerédi theorem of the second author and Leibman [

Reference Bergelson and Leibman7

] extends Furstenberg’s result to polynomial configurations. We say that a polynomial

![]() $p(x) \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

is integer-valued if

$p(x) \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

is integer-valued if

![]() $p(\mathbb{Z}) \subseteq \mathbb{Z}$

.

$p(\mathbb{Z}) \subseteq \mathbb{Z}$

.

Theorem 1·2 ([

Reference Bergelson and Leibman7

, special case of theorem A]). Let

![]() $p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be integer-valued polynomials with zero constant term. Then for any invertible probability measure-preserving system

$p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be integer-valued polynomials with zero constant term. Then for any invertible probability measure-preserving system

![]() $(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and any

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and any

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

with

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

with

![]() $\mu(A) > 0$

, there exists

$\mu(A) > 0$

, there exists

![]() $c > 0$

such that the set

$c > 0$

such that the set

has positive lower density, i.e.

![]() $\liminf_{N \to \infty}{{|R \cap \{1, \dots, N\}|}/{N}} > 0$

.

$\liminf_{N \to \infty}{{|R \cap \{1, \dots, N\}|}/{N}} > 0$

.

The conclusion of Theorem 1·2 was strengthened in [

Reference Bergelson and McCutcheon12

, theorem 0·1], where it was shown that R is syndetic for some

![]() $c > 0$

depending on A.

$c > 0$

depending on A.

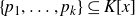

There is a wider variety of combinatorial configurations in play when polynomials are introduced, and there is not yet a full classification of which families of polynomials have the large intersections property. However, large intersections variants of the polynomial Szemerédi theorem are known for two natural classes of polynomial configurations: independent polynomials and polynomials that are integer multiples of a fixed polynomial (for

![]() $k=2, 3$

). This is summarised by the following two results, which we seek to extend in this paper:

$k=2, 3$

). This is summarised by the following two results, which we seek to extend in this paper:

Theorem 1·3 ([

Reference Frantzikinakis and Kra21

, theorem 1·3]). Let

![]() $p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be linearly independent integer-valued polynomials with zero constant term. Then for any invertible probability measure-preserving system, any

$p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be linearly independent integer-valued polynomials with zero constant term. Then for any invertible probability measure-preserving system, any

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and any

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

is syndetic.

Theorem 1·4 ([

Reference Frantzikinakis19

, theorem C]). Let

![]() $p \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be an integer-valued polynomial with zero constant term, and let

$p \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be an integer-valued polynomial with zero constant term, and let

![]() $a, b \in \mathbb{Z}$

be nonzero and distinct. Then for any ergodic invertible probability measure-preserving system, any

$a, b \in \mathbb{Z}$

be nonzero and distinct. Then for any ergodic invertible probability measure-preserving system, any

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and any

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

, the sets

$\varepsilon > 0$

, the sets

and

are syndetic.

We have so far stated all results about polynomial multiple recurrence only for polynomials with zero constant term. The essential feature of such families of polynomials is that they avoid “local obstructions.” To be precise, we say that a family of polynomials

![]() $\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is jointly intersective if for every

$\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is jointly intersective if for every

![]() $m \in \mathbb{N}$

, there exists

$m \in \mathbb{N}$

, there exists

![]() $n \in \mathbb{Z}$

such that

$n \in \mathbb{Z}$

such that

![]() $p_i(n) \in m\mathbb{Z}$

for every

$p_i(n) \in m\mathbb{Z}$

for every

![]() $i = 1, \dots, k$

. If a family of polynomials is not jointly intersective, then the set appearing in (1·2) will be trivial for some rotations on finitely many points. In [

Reference Bergelson, Leibman and Lesigne11

], it was shown that there are no other obstacles to multiple recurrence:

$i = 1, \dots, k$

. If a family of polynomials is not jointly intersective, then the set appearing in (1·2) will be trivial for some rotations on finitely many points. In [

Reference Bergelson, Leibman and Lesigne11

], it was shown that there are no other obstacles to multiple recurrence:

Theorem 1·5 ([

Reference Bergelson, Leibman and Lesigne11

, theorem 1·1]). For a family of integer-valued polynomials

![]() $\mathcal{P} = \{p_1, \dots, p_k\} \subseteq \mathbb{Q}[x]$

, the following are equivalent:

$\mathcal{P} = \{p_1, \dots, p_k\} \subseteq \mathbb{Q}[x]$

, the following are equivalent:

-

(i)

$\mathcal{P}$

is jointly intersective;

$\mathcal{P}$

is jointly intersective;

-

(ii) for any probability measure-preserving system

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and any

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, there exists

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, there exists

$c > 0$

such that is syndetic.

$c > 0$

such that is syndetic. \begin{align*} \left\{ n \in \mathbb{Z} \;:\; \mu \left( A \cap T^{-p_1(n)}A \cap \dots \cap T^{-p_k(n)}A \right) > c \right\} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \left\{ n \in \mathbb{Z} \;:\; \mu \left( A \cap T^{-p_1(n)}A \cap \dots \cap T^{-p_k(n)}A \right) > c \right\} \end{align*}

The proofs of Theorems 1·3 and 1·4 can also be easily modified to apply to families of jointly intersective polynomials.

The polynomial Szemerédi theorem is in fact known for polynomials of several variables with zero constant term (see [

Reference Bergelson and Leibman7

, theorem A] for the result with positive lower density and [

Reference Bergelson and McCutcheon13

, theorem 0·7] for syndeticity). For polynomials arising from rings of integers, the polynomial Szemerédi theorem holds for all jointly intersective polynomials. We now make this result precise. Fix a number field K and denote by

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

its ring of integers. By an

$\mathcal{O}_K$

its ring of integers. By an

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system, we will mean a quadruple

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system, we will mean a quadruple

![]() $(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

, where T is a measure-preserving action of

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

, where T is a measure-preserving action of

![]() $(\mathcal{O}_K,+)$

on a probability space

$(\mathcal{O}_K,+)$

on a probability space

![]() $(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu)$

.

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu)$

.

Definition 1·6. A family of

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials

![]() $\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is jointly intersective if for every finite index subgroup

$\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is jointly intersective if for every finite index subgroup

![]() $\Lambda \subseteq (\mathcal{O}_K, +)$

, there exists

$\Lambda \subseteq (\mathcal{O}_K, +)$

, there exists

![]() $\xi \in \mathcal{O}_K$

such that

$\xi \in \mathcal{O}_K$

such that

![]() $\{p_1(\xi), \dots, p_k(\xi)\} \subseteq \Lambda$

.

$\{p_1(\xi), \dots, p_k(\xi)\} \subseteq \Lambda$

.

Recall that in an abelian group G, a set

![]() $E \subseteq G$

is syndetic if finitely many translates of E cover G. That is,

$E \subseteq G$

is syndetic if finitely many translates of E cover G. That is,

![]() $G = \bigcup_{i=1}^m{(E + g_i)}$

for some

$G = \bigcup_{i=1}^m{(E + g_i)}$

for some

![]() $g_1, \dots, g_m \in G$

.

$g_1, \dots, g_m \in G$

.

Theorem 1·7 ([

Reference Bergelson and Robertson14

, theorem 1·6]). Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

![]() $p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathcal{O}_K[x]$

be jointly intersective polynomials. For any

$p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathcal{O}_K[x]$

be jointly intersective polynomials. For any

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

![]() $(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and any

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and any

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

, there exists

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, there exists

![]() $c > 0$

such that the set

$c > 0$

such that the set

is syndetic.

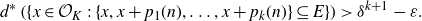

It is therefore natural to ask whether Khintchine-type recurrence theorems hold for polynomial configurations in rings of integers. That is, under what conditions on the polynomials

![]() $\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

can the constant c in (1·3) be made arbitrarily close to

$\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

can the constant c in (1·3) be made arbitrarily close to

![]() $\mu(A)^{k+1}$

?

$\mu(A)^{k+1}$

?

In this paper, we provide an answer to this question in natural and important cases by proving extensions of Theorems 1·3 and 1·4.

Theorem A.

Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

![]() $\{p_1, \dots , p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

be a jointly intersective family of linearly independent

$\{p_1, \dots , p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

be a jointly intersective family of linearly independent

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. Then for any measure-preserving

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. Then for any measure-preserving

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

,

$\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

,

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

is syndetic.

Theorem B.

Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

![]() $p(x) \in K[x]$

be an

$p(x) \in K[x]$

be an

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued intersective polynomial. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued intersective polynomial. Let

![]() $r,s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero. Then for any ergodic measure-preserving

$r,s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero. Then for any ergodic measure-preserving

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

,

$\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

,

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

is syndetic.

Moreover, if

![]() ${s}/{r} \in \mathbb{Q}$

, then

${s}/{r} \in \mathbb{Q}$

, then

is syndetic.

Note that for a pair of polynomials

![]() $\{p,q\} \subseteq K[x] \setminus \{0\}$

, either p and q are linearly independent over K or

$\{p,q\} \subseteq K[x] \setminus \{0\}$

, either p and q are linearly independent over K or

![]() $q = cp$

for some

$q = cp$

for some

![]() $c \in K$

. Thus, we have the following immediate consequence of Theorems A and B together:

$c \in K$

. Thus, we have the following immediate consequence of Theorems A and B together:

Corollary 1·8.

Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Suppose

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Suppose

![]() $\{p, q\} \subseteq K[x]$

is a jointly intersective pair of

$\{p, q\} \subseteq K[x]$

is a jointly intersective pair of

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. Then for any ergodic measure-preserving

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. Then for any ergodic measure-preserving

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

, any

$\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

, any

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and any

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

is syndetic.

Theorem A shows that for independent families of any size, we can achieve Khintchine-type results. In contrast, Theorem B only demonstrates a Khintchine-type result for configurations of length three or four and requires ergodicity of the system (for counterexamples in the non-ergodic case, see [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

, section 11·1]). Moreover, for length four, we have made additional assumptions, which we discuss below. To complete the picture, we now address what happens for patterns of length five and longer. For concreteness, let us consider general polynomial families of the form

![]() $\{a_1p, \dots, a_kp\}$

, where

$\{a_1p, \dots, a_kp\}$

, where

![]() $a_i \in \mathcal{O}_K$

and

$a_i \in \mathcal{O}_K$

and

![]() $p(x) \in K[x]$

is

$p(x) \in K[x]$

is

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued. In the simplest case when

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued. In the simplest case when

![]() $K = \mathbb{Q}$

and

$K = \mathbb{Q}$

and

![]() $a_i = i$

, a combinatorial construction of Ruzsa rules out Khintchine-type results when

$a_i = i$

, a combinatorial construction of Ruzsa rules out Khintchine-type results when

![]() $k \ge 4$

(see item 3 of Theorem 1·1 above). In [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

, corollary 12·14], this was generalised to any number field K and any integers

$k \ge 4$

(see item 3 of Theorem 1·1 above). In [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

, corollary 12·14], this was generalised to any number field K and any integers

![]() $a_i \in \mathbb{Z}$

for

$a_i \in \mathbb{Z}$

for

![]() $k \ge 4$

. Furthermore, [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

, proposition 12·13] gives a combinatorial criterion for checking the case

$k \ge 4$

. Furthermore, [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

, proposition 12·13] gives a combinatorial criterion for checking the case

![]() $k = 4$

for any coefficients

$k = 4$

for any coefficients

![]() $a_i \in \mathcal{O}_K$

. We do not know how to prove the requisite combinatorial result, but we believe that Khintchine-type results will fail for any non-trivial family

$a_i \in \mathcal{O}_K$

. We do not know how to prove the requisite combinatorial result, but we believe that Khintchine-type results will fail for any non-trivial family

![]() $\{a_1p, \dots, a_kp\}$

with

$\{a_1p, \dots, a_kp\}$

with

![]() $k \ge 4$

.

$k \ge 4$

.

Now we turn to the other conditions imposed for the patterns of length four appearing in Theorem B. The strategy of proof in Theorem B is to reduce to the linear case

![]() $p(n) = n$

and then apply knowledge about linear patterns. General Khintchine-type results for linear patterns appear in [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

] (subsequently improved in [

Reference Ackelsberg1, Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Shalom3

]), where a similar distinction is made between patterns of length three and of length four:

$p(n) = n$

and then apply knowledge about linear patterns. General Khintchine-type results for linear patterns appear in [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

] (subsequently improved in [

Reference Ackelsberg1, Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Shalom3

]), where a similar distinction is made between patterns of length three and of length four:

Theorem 1·9 ([

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

, theorems 1·10 and 1·11]). Let

![]() $(G,+)$

be a countable discrete abelian group. Let

$(G,+)$

be a countable discrete abelian group. Let

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

be an ergodic measure-preserving G-system. Let

$\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

be an ergodic measure-preserving G-system. Let

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

and

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

and

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

.

$\varepsilon > 0$

.

-

(1) suppose

$\varphi, \psi \;:\; G \to G$

are homomorphisms such that the subgroups

$\varphi, \psi \;:\; G \to G$

are homomorphisms such that the subgroups

$\varphi(G)$

,

$\varphi(G)$

,

$\psi(G)$

, and

$\psi(G)$

, and

$(\psi-\varphi)(G)$

have finite index in G. Then is syndetic in G.

$(\psi-\varphi)(G)$

have finite index in G. Then is syndetic in G. \begin{align*} \left\{ g \in G \;:\; \mu \left( A \cap T_{\varphi(g)}^{-1}A \cap T_{\psi(g)}^{-1}A \right) > \mu(A)^3 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \left\{ g \in G \;:\; \mu \left( A \cap T_{\varphi(g)}^{-1}A \cap T_{\psi(g)}^{-1}A \right) > \mu(A)^3 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align*}

-

(2) suppose

$r, s \in \mathbb{Z}$

are distinct and nonzero such that the subgroups rG, sG,

$r, s \in \mathbb{Z}$

are distinct and nonzero such that the subgroups rG, sG,

$(r+s)G$

, and

$(r+s)G$

, and

$(s-r)G$

have finite index in G. Then is syndetic in G.

$(s-r)G$

have finite index in G. Then is syndetic in G. \begin{align*} \left\{ g \in G \;:\; \mu \left( A \cap T_{rg}^{-1}A \cap T_{sg}^{-1}A \cap T_{(r+s)g}^{-1}A \right) > \mu(A)^4 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \left\{ g \in G \;:\; \mu \left( A \cap T_{rg}^{-1}A \cap T_{sg}^{-1}A \cap T_{(r+s)g}^{-1}A \right) > \mu(A)^4 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align*}

The second half of Theorem 1·9 was also proved independently in [

Reference Shalom37

, theorem 1·3]. By absorbing a constant into the polynomial p in Theorem B, imposing the condition

![]() $\frac{s}{r} \in \mathbb{Q}$

is equivalent to assuming

$\frac{s}{r} \in \mathbb{Q}$

is equivalent to assuming

![]() $r, s \in \mathbb{Z}$

, so our assumptions allow us to apply Theorem 1·9 in the linear case

$r, s \in \mathbb{Z}$

, so our assumptions allow us to apply Theorem 1·9 in the linear case

![]() $p(n) = n$

.

$p(n) = n$

.

In [

Reference Berger, Sah, Sawhney and Tidor16

], it was shown that, for a related finitary problem, there are automorphisms

![]() $\varphi$

and

$\varphi$

and

![]() $\psi$

such that

$\psi$

such that

![]() $\varphi + \psi$

and

$\varphi + \psi$

and

![]() $\psi - \varphi$

are also automorphisms but for which a Khintchine-type result fails:

$\psi - \varphi$

are also automorphisms but for which a Khintchine-type result fails:

Theorem 1·10 ([

Reference Berger, Sah, Sawhney and Tidor16

, theorem 1·3]). There is an absolute constant

![]() $c > 0$

such that the following holds. If

$c > 0$

such that the following holds. If

![]() $\alpha \in (0, c)$

, then for all sufficiently large n (depending on

$\alpha \in (0, c)$

, then for all sufficiently large n (depending on

![]() $\alpha$

), there is a set

$\alpha$

), there is a set

![]() $A \subseteq (\mathbb{F}_5^n)^2$

with

$A \subseteq (\mathbb{F}_5^n)^2$

with

![]() $|A| \ge \alpha \cdot 5^{2n}$

such that

$|A| \ge \alpha \cdot 5^{2n}$

such that

for all

![]() $(a, b) \in (\mathbb{F}_5^n)^2 \setminus \{(0,0)\}$

.

$(a, b) \in (\mathbb{F}_5^n)^2 \setminus \{(0,0)\}$

.

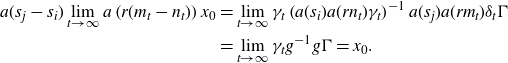

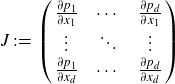

The authors of [ Reference Berger, Sah, Sawhney and Tidor16 ] explain the failure of large intersections in Theorem 1·10 as a consequence of an eigenvalue condition. Namely, for the corresponding matrices

the eigenvalues of

![]() $M_1M_2^{-1}$

are negatives of each other. They also show that in the absence of such an eigenvalue condition, a Khintchine-type result holds for patterns

$M_1M_2^{-1}$

are negatives of each other. They also show that in the absence of such an eigenvalue condition, a Khintchine-type result holds for patterns

(see [ Reference Berger, Sah, Sawhney and Tidor16 , theorem 1·2]).

In our context of rings of integers, we can translate the eigenvalue condition into an algebraic criterion. Recall that two algebraic numbers

![]() $\alpha, \beta \in K$

are conjugate (over

$\alpha, \beta \in K$

are conjugate (over

![]() $\mathbb{Q}$

) if they have the same minimal polynomial (over

$\mathbb{Q}$

) if they have the same minimal polynomial (over

![]() $\mathbb{Q}$

). Equivalently, there is a field automorphism

$\mathbb{Q}$

). Equivalently, there is a field automorphism

![]() $\varphi \;:\; K \to K$

such that

$\varphi \;:\; K \to K$

such that

![]() $\varphi(\alpha) = \beta$

. If we denote by

$\varphi(\alpha) = \beta$

. If we denote by

![]() $M_{\alpha}$

the

$M_{\alpha}$

the

![]() $\mathbb{Q}$

-linear map

$\mathbb{Q}$

-linear map

![]() $M_{\alpha}x = \alpha x$

on the

$M_{\alpha}x = \alpha x$

on the

![]() $\mathbb{Q}$

-vector space K, then the eigenvalues of

$\mathbb{Q}$

-vector space K, then the eigenvalues of

![]() $M_{\alpha}$

are exactly the conjugates of

$M_{\alpha}$

are exactly the conjugates of

![]() $\alpha$

(this follows from, e.g., [

Reference Conrad18

, theorem 5·9], which gives a formula for the characteristic polynomial of

$\alpha$

(this follows from, e.g., [

Reference Conrad18

, theorem 5·9], which gives a formula for the characteristic polynomial of

![]() $M_{\alpha}$

). We therefore make the following conjecture:

$M_{\alpha}$

). We therefore make the following conjecture:

Conjecture 1·11.

Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

![]() $r, s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero. The following are equivalent:

$r, s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero. The following are equivalent:

-

(i) for any ergodic measure-preserving

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

, any

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

, any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, any

$\varepsilon > 0$

, and any

$\varepsilon > 0$

, and any

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued intersective polynomial

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued intersective polynomial

$p \in K[x]$

, the set is syndetic;

$p \in K[x]$

, the set is syndetic; \begin{align*} \left\{ n \in \mathcal{O}_K \;:\; \mu \left( A \cap T^{-rp(n)}A \cap T^{-sp(n)}A \cap T^{-(r+s)p(n)}A \right) > \mu(A)^4 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \left\{ n \in \mathcal{O}_K \;:\; \mu \left( A \cap T^{-rp(n)}A \cap T^{-sp(n)}A \cap T^{-(r+s)p(n)}A \right) > \mu(A)^4 - \varepsilon \right\} \end{align*}

-

(ii) no two conjugates of

${s}/{r}$

over

${s}/{r}$

over

$\mathbb{Q}$

are negatives of each other.

$\mathbb{Q}$

are negatives of each other.

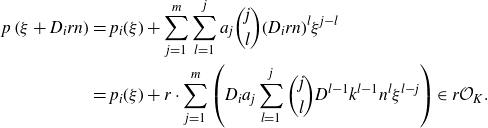

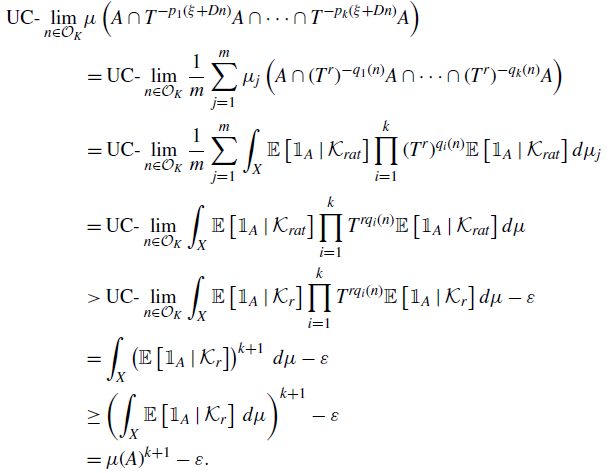

1·2. Method

In order to prove Khintchine-type recurrence results such as Theorem A and Theorem B, it is natural to consider associated multiple ergodic averages. The appropriate averaging schemes in rings of integers are those arising from Følner sequences. A Følner sequence in

![]() $(\mathcal{O}_K, +)$

is a sequence of subsets

$(\mathcal{O}_K, +)$

is a sequence of subsets

![]() $(\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

of

$(\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

of

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

such that, for every

$\mathcal{O}_K$

such that, for every

![]() $n \in \mathcal{O}_K$

,

$n \in \mathcal{O}_K$

,

Examples of Følner sequences include boxes in

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K \cong \mathbb{Z}^d$

with increasing side lengths. We say that a sequence

$\mathcal{O}_K \cong \mathbb{Z}^d$

with increasing side lengths. We say that a sequence

![]() $(u_n)_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}$

has uniform Cesàro limit u, denoted

$(u_n)_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}$

has uniform Cesàro limit u, denoted

![]() $\text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{u_n} = u$

, if

$\text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{u_n} = u$

, if

for every Følner sequence

![]() $(\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

in

$(\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

in

![]() $(\mathcal{O}_K, +)$

. The usefulness of uniform Cesàro limits in proving Khintchine-type theorems comes from the following routine fact (for a proof, see [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

, lemma 1·9]):

$(\mathcal{O}_K, +)$

. The usefulness of uniform Cesàro limits in proving Khintchine-type theorems comes from the following routine fact (for a proof, see [

Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2

, lemma 1·9]):

Proposition 1·12.

A set

![]() $S \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

is syndetic if and only if for any Følner sequence

$S \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

is syndetic if and only if for any Følner sequence

![]() $(\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

in

$(\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

in

![]() $(\mathcal{O}_K, +)$

, one has

$(\mathcal{O}_K, +)$

, one has

![]() $\bigcup_{N \in \mathbb{N}}{\Phi_N} \cap S \ne \emptyset$

.

$\bigcup_{N \in \mathbb{N}}{\Phi_N} \cap S \ne \emptyset$

.

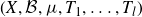

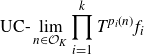

Rather than computing the multiple ergodic averages

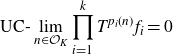

\begin{align} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)}f_i}}\end{align}

\begin{align} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)}f_i}}\end{align}

directly for an arbitrary

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system, we reduce to computing the averages (1·7) in simpler classes of systems. To be precise, we say a system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system, we reduce to computing the averages (1·7) in simpler classes of systems. To be precise, we say a system

![]() $\textbf{Y} = \left( Y, \mathcal{D}, \nu, S \right)$

is a factor of

$\textbf{Y} = \left( Y, \mathcal{D}, \nu, S \right)$

is a factor of

![]() $\textbf{X} = \left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

if there are full measure subsets

$\textbf{X} = \left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

if there are full measure subsets

![]() $X_0 \subseteq X$

and

$X_0 \subseteq X$

and

![]() $Y_0 \subseteq Y$

and a measure-preserving map

$Y_0 \subseteq Y$

and a measure-preserving map

![]() $\pi \;:\; X_0 \to Y_0$

such that

$\pi \;:\; X_0 \to Y_0$

such that

![]() $S^n\pi(x) = \pi(T^nx)$

for every

$S^n\pi(x) = \pi(T^nx)$

for every

![]() $x \in X_0$

,

$x \in X_0$

,

![]() $n \in \mathcal{O}_K$

. There is a natural correspondence between the factor Y and the T-invariant sub-

$n \in \mathcal{O}_K$

. There is a natural correspondence between the factor Y and the T-invariant sub-

![]() $\sigma$

-algebra

$\sigma$

-algebra

![]() $\pi^{-1}(\mathcal{D})$

. This allows us to take conditional expectations, and in a standard abuse of notation, we write

$\pi^{-1}(\mathcal{D})$

. This allows us to take conditional expectations, and in a standard abuse of notation, we write

![]() $\mathbb{E}\left[ {f} \mid {Y} \right] \;:\!=\; \mathbb{E}\left[ {f} \mid {\pi^{-1}(\mathcal{D})} \right]$

. The factor

$\mathbb{E}\left[ {f} \mid {Y} \right] \;:\!=\; \mathbb{E}\left[ {f} \mid {\pi^{-1}(\mathcal{D})} \right]$

. The factor

![]() $\textbf{Y}$

is characteristic for a family of sequences

$\textbf{Y}$

is characteristic for a family of sequences

![]() $\{a_1(n), \dots, a_k(n)\}, n \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, if for any

$\{a_1(n), \dots, a_k(n)\}, n \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, if for any

![]() $f_1, \dots, f_k \in L^{\infty}(\mu)$

,

$f_1, \dots, f_k \in L^{\infty}(\mu)$

,

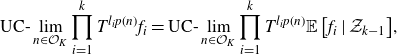

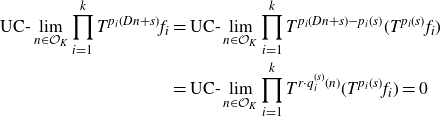

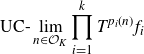

\begin{align*} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\left( \prod_{i=1}^k{T^{a_i(n)}f_i} - \prod_{i=1}^k{T^{a_i(n)}\mathbb{E}\left[ {f_i} \mid {Y} \right]} \right)} = 0\end{align*}

\begin{align*} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\left( \prod_{i=1}^k{T^{a_i(n)}f_i} - \prod_{i=1}^k{T^{a_i(n)}\mathbb{E}\left[ {f_i} \mid {Y} \right]} \right)} = 0\end{align*}

in

![]() $L^2(\mu)$

.

$L^2(\mu)$

.

The main family of factors that we will deal with is the family of nilfactors

![]() $(\mathcal{Z}_r)_{r \in \mathbb{N}}$

(also called Host–Kra factors from the work of Host and Kra on

$(\mathcal{Z}_r)_{r \in \mathbb{N}}$

(also called Host–Kra factors from the work of Host and Kra on

![]() $\mathbb{Z}$

-actions [

Reference Host and Kra30

]). Assume for this discussion that T is an ergodic action of

$\mathbb{Z}$

-actions [

Reference Host and Kra30

]). Assume for this discussion that T is an ergodic action of

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. The factor

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. The factor

![]() $\mathcal{Z}_r$

is defined to be the minimal factor that is characteristic for all families

$\mathcal{Z}_r$

is defined to be the minimal factor that is characteristic for all families

![]() $\{l_1n, \dots, l_{r+1}n\}$

with

$\{l_1n, \dots, l_{r+1}n\}$

with

![]() $l_1, \dots, l_{r+1} \in \mathcal{O}_K$

distinct and nonzero. For our purposes, it will suffice to discuss some general properties of nilfactors.

$l_1, \dots, l_{r+1} \in \mathcal{O}_K$

distinct and nonzero. For our purposes, it will suffice to discuss some general properties of nilfactors.

The tower of factors

![]() $\mathcal{Z}_1 \subseteq \mathcal{Z}_2 \subseteq \dots$

is a sequence of compact extensions. The first factor,

$\mathcal{Z}_1 \subseteq \mathcal{Z}_2 \subseteq \dots$

is a sequence of compact extensions. The first factor,

![]() $\mathcal{Z}_1$

, is the Kronecker factor, which is the smallest factor for which every eigenfunction is measurable. As a measure-preserving system, it is isomorphic to an action by rotations on a compact abelian group. The Kronecker factor contains a subfactor that will also be of interest, namely the rational Kronecker factor, denoted

$\mathcal{Z}_1$

, is the Kronecker factor, which is the smallest factor for which every eigenfunction is measurable. As a measure-preserving system, it is isomorphic to an action by rotations on a compact abelian group. The Kronecker factor contains a subfactor that will also be of interest, namely the rational Kronecker factor, denoted

![]() $\mathcal{K}_{rat}$

, which is an inverse limit of finite rotational systems (for a more detailed discussion of the rational Kronecker factor, see Section 2.1).

$\mathcal{K}_{rat}$

, which is an inverse limit of finite rotational systems (for a more detailed discussion of the rational Kronecker factor, see Section 2.1).

The higher-level nilfactors also have the structure of (inverse limits of) “rotational” systems but on more complex algebraic objects. Let G be an r-step nilpotent Lie group and

![]() $\Gamma < G$

a co-compact discrete subgroup. The quotient space

$\Gamma < G$

a co-compact discrete subgroup. The quotient space

![]() $X = G/\Gamma$

is called an r-step nilmanifold. An r-step nilsystem is a system

$X = G/\Gamma$

is called an r-step nilmanifold. An r-step nilsystem is a system

![]() $(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

, where

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

, where

![]() $X = G/\Gamma$

is an r-step nilmanifold,

$X = G/\Gamma$

is an r-step nilmanifold,

![]() $\mu$

is the Haar probability measure on X, and T is an

$\mu$

is the Haar probability measure on X, and T is an

![]() $(\mathcal{O}_K,+)$

-action by niltranslations, i.e. transformations of the form

$(\mathcal{O}_K,+)$

-action by niltranslations, i.e. transformations of the form

![]() $x \mapsto ax$

for some

$x \mapsto ax$

for some

![]() $a \in G$

. The nilfactor

$a \in G$

. The nilfactor

![]() $\mathcal{Z}_r$

is an inverse limit of r-step nilsystems. For

$\mathcal{Z}_r$

is an inverse limit of r-step nilsystems. For

![]() $\mathbb{Z}$

-actions, this was established by Host and Kra in [

Reference Host and Kra30

] and independently by Ziegler in [

Reference Ziegler39

]. For our generality of

$\mathbb{Z}$

-actions, this was established by Host and Kra in [

Reference Host and Kra30

] and independently by Ziegler in [

Reference Ziegler39

]. For our generality of

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-systems, this follows from [

Reference Griesmer27

, theorem 4·1·2].

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-systems, this follows from [

Reference Griesmer27

, theorem 4·1·2].

By careful application of the van der Corput differencing trick, one can reduce polynomial expressions to (potentially much longer) linear expressions. This works so long as the polynomials

![]() $p_1, \dots, p_k$

are essentially distinct, meaning that

$p_1, \dots, p_k$

are essentially distinct, meaning that

![]() $p_j - p_i$

is non-constant for every

$p_j - p_i$

is non-constant for every

![]() $i \ne j$

. Hence, for any family of essentially distinct polynomial sequences

$i \ne j$

. Hence, for any family of essentially distinct polynomial sequences

![]() $\{p_1(n), \dots, p_k(n)\}, n \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, there is a characteristic factor that is a nilfactor (but the step of the nilfactor may far exceed

$\{p_1(n), \dots, p_k(n)\}, n \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, there is a characteristic factor that is a nilfactor (but the step of the nilfactor may far exceed

![]() $k-1$

in general):

$k-1$

in general):

Theorem 1·13 (cf. [

Reference Bergelson and Robertson14

, theorem 5·2]). Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Suppose

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Suppose

![]() $\{p_1, \dots, p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

are non-constant and essentially distinct

$\{p_1, \dots, p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

are non-constant and essentially distinct

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. Then there is an

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. Then there is an

![]() $r \in \mathbb{N}$

such that for any ergodic

$r \in \mathbb{N}$

such that for any ergodic

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

![]() $(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and any

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and any

![]() $f_1, \dots, f_k \in L^{\infty}(\mu)$

,

$f_1, \dots, f_k \in L^{\infty}(\mu)$

,

\begin{align*} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)}f_i}} = \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)} \mathbb{E}\left[ {f_i} \mid {\mathcal{Z}_r} \right]}}. \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)}f_i}} = \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)} \mathbb{E}\left[ {f_i} \mid {\mathcal{Z}_r} \right]}}. \end{align*}

in

![]() $L^2(\mu)$

.

$L^2(\mu)$

.

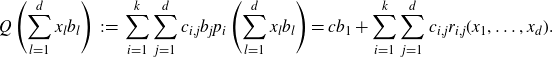

For the specific configurations appearing in Theorem A (independent polynomials) and in Theorem B (multiples of a single polynomial), we can control the step of the characteristic nilfactors. In order to properly formulate our results, we need one more definition.

Definition 1·14. A family of polynomials

![]() $\{p_1, \dots, p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

is independent if for all

$\{p_1, \dots, p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

is independent if for all

![]() $(c_1, \dots, c_k) \in K^k \setminus \{0\}$

, the polynomial

$(c_1, \dots, c_k) \in K^k \setminus \{0\}$

, the polynomial

![]() $\sum_{i=1}^k{c_ip_i}$

is non-constant.

$\sum_{i=1}^k{c_ip_i}$

is non-constant.

Note that the family

![]() $\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is independent if and only if

$\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is independent if and only if

![]() $\{1, p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is linearly independent over K. Furthermore, a jointly intersective family

$\{1, p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is linearly independent over K. Furthermore, a jointly intersective family

![]() $\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is independent if and only if it is linearly independent.

$\{p_1, \dots, p_k\}$

is independent if and only if it is linearly independent.

Theorem C.

Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Suppose

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Suppose

![]() $p_1, \dots, p_k \in K[x]$

are independent and

$p_1, \dots, p_k \in K[x]$

are independent and

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued. Then for any ergodic measure-preserving

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued. Then for any ergodic measure-preserving

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

and any

$\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

and any

![]() $f_1, \dots, f_k \in L^{\infty}(\mu)$

,

$f_1, \dots, f_k \in L^{\infty}(\mu)$

,

\begin{align*} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)}f_i}} = \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)} \mathbb{E}\left[ {f_i} \mid {\mathcal{K}_{rat}} \right]}}, \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)}f_i}} = \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{p_i(n)} \mathbb{E}\left[ {f_i} \mid {\mathcal{K}_{rat}} \right]}}, \end{align*}

where the limits are taken in

![]() $L^2(\mu)$

.

$L^2(\mu)$

.

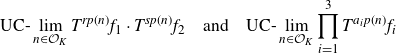

Theorem D.

Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

![]() $p(x) \in K[x]$

be a non-constant

$p(x) \in K[x]$

be a non-constant

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomial. Then for any ergodic measure-preserving

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomial. Then for any ergodic measure-preserving

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

, any

$\left( X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T \right)$

, any

![]() $l_1, \dots, l_k \in \mathcal{O}_K$

distinct and nonzero, and any

$l_1, \dots, l_k \in \mathcal{O}_K$

distinct and nonzero, and any

![]() $f_1, \dots, f_k \in L^{\infty}(\mu)$

,

$f_1, \dots, f_k \in L^{\infty}(\mu)$

,

\begin{align*} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{l_ip(n)}f_i}} = \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{l_ip(n)} \mathbb{E}\left[ {f_i} \mid {\mathcal{Z}_{k-1}} \right]}}, \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{l_ip(n)}f_i}} = \text{UC-}\lim_{n \in \mathcal{O}_K}{\prod_{i=1}^k{T^{l_ip(n)} \mathbb{E}\left[ {f_i} \mid {\mathcal{Z}_{k-1}} \right]}}, \end{align*}

where the limits are taken in

![]() $L^2(\mu)$

. Moreover, if T is totally ergodic, then this limit does not depend on the polynomial p.

$L^2(\mu)$

. Moreover, if T is totally ergodic, then this limit does not depend on the polynomial p.

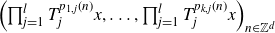

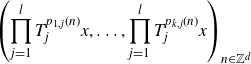

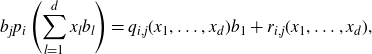

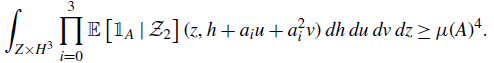

We will prove Theorems C and D via equidistribution results for polynomial sequences in nilmanifolds, which are of independent interest (see Theorem 3·3 and Proposition 3·12 below). After several reductions, the main technical result in the proof of Theorem C is the following far-reaching generalisation of Weyl’s polynomial equidistribution theorem for families of independent polynomials in several variables:

Theorem 1·15 (Theorem 3·8). Let

![]() $d, l, k, m \in \mathbb{N}$

. Let

$d, l, k, m \in \mathbb{N}$

. Let

![]() $\{p_{i,j} \;:\; 1 \le i \le k, 1 \le j \le l\} \subseteq \mathbb{Q}[x_1, \dots, x_d]$

be

$\{p_{i,j} \;:\; 1 \le i \le k, 1 \le j \le l\} \subseteq \mathbb{Q}[x_1, \dots, x_d]$

be

![]() $\mathbb{Z}$

-valued and independent over

$\mathbb{Z}$

-valued and independent over

![]() $\mathbb{Q}$

. Let

$\mathbb{Q}$

. Let

![]() $T_1, \dots, T_l \;:\; \mathbb{T}^m \to \mathbb{T}^m$

be commuting unipotent affine transformations generating an ergodic

$T_1, \dots, T_l \;:\; \mathbb{T}^m \to \mathbb{T}^m$

be commuting unipotent affine transformations generating an ergodic

![]() $\mathbb{Z}^l$

-action. Then the polynomial sequence

$\mathbb{Z}^l$

-action. Then the polynomial sequence

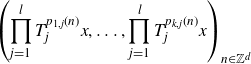

\begin{align*} \left( \prod_{j=1}^l{T_j^{p_{1,j}(n)}}x, \dots, \prod_{j=1}^l{T_j^{p_{k,j}(n)}}x \right)_{n \in \mathbb{Z}^d} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \left( \prod_{j=1}^l{T_j^{p_{1,j}(n)}}x, \dots, \prod_{j=1}^l{T_j^{p_{k,j}(n)}}x \right)_{n \in \mathbb{Z}^d} \end{align*}

is well-distributed in

![]() $\mathbb{T}^{mk}$

for all x in a co-meager set of full measure.

$\mathbb{T}^{mk}$

for all x in a co-meager set of full measure.

The upshot of Theorem C is that we may compute multiple ergodic averages for independent polynomials by studying the corresponding averages in a finite rotational system, where computations are much easier to carry out. Similarly, Theorem D says that in order to compute multiple ergodic averages for k distinct multiples of a fixed polynomial, we can make use of the algebraic structure of a

![]() $(k-1)$

-step nilsystem.

$(k-1)$

-step nilsystem.

From here, we can follow a standard technique to deduce the corresponding Khintchine-type results. The assumption that the families of polynomials under consideration are jointly intersective, together with a standard approximation argument, allows us to reduce to the case that the action T is totally ergodic, i.e. that

![]() $\mathcal{K}_{rat}$

is trivial. For independent polynomials, Theorem C guarantees that

$\mathcal{K}_{rat}$

is trivial. For independent polynomials, Theorem C guarantees that

for totally ergodic T, from which Theorem A immediately follows. The details of this argument are carried out in Section 4.1. When all of the polynomials involved are multiples of a fixed polynomial and T is totally ergodic, Theorem D says that the relevant multiple ergodic average can be reduced to a linear average (corresponding to

![]() $p(n) = n$

). We are therefore able to capitalise on Khintchine-type results for linear averages (see Theorem 1·9 above) and extend them to the polynomial configurations we consider in Theorem B. The full details of this argument appear in Section 4.2.

$p(n) = n$

). We are therefore able to capitalise on Khintchine-type results for linear averages (see Theorem 1·9 above) and extend them to the polynomial configurations we consider in Theorem B. The full details of this argument appear in Section 4.2.

1·3. Notions of largeness

Syndeticity is just one of many notions of largeness that naturally appear in ergodic theory and combinatorics. While it is useful in quantifying the size of subsets, it does not have all of the properties that one may desire. To illustrate one shortcoming of syndeticity, we return to Szemerédi’s theorem. Consider the family of sets

![]() $\mathcal{R}_k \;:\!=\; \{R_k(\textbf{X}, A) \;:\; \textbf{X} = (X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)\;\text{mps}, A \in \mathcal{B}, \mu(A) > 0\}$

, where

$\mathcal{R}_k \;:\!=\; \{R_k(\textbf{X}, A) \;:\; \textbf{X} = (X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)\;\text{mps}, A \in \mathcal{B}, \mu(A) > 0\}$

, where

The family

![]() $\mathcal{R}_k$

has the filter property: for any

$\mathcal{R}_k$

has the filter property: for any

![]() $R, S \in \mathcal{R}_k$

, we have

$R, S \in \mathcal{R}_k$

, we have

![]() $R \cap S \ne \emptyset$

. Indeed, given two measure-preserving systems

$R \cap S \ne \emptyset$

. Indeed, given two measure-preserving systems

![]() $\textbf{X} = (X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and

$\textbf{X} = (X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and

![]() $\textbf{Y} = (Y, \mathcal{D}, \nu, S)$

, one can form the product system

$\textbf{Y} = (Y, \mathcal{D}, \nu, S)$

, one can form the product system

![]() $\textbf{X} \times \textbf{Y}$

and easily verify that

$\textbf{X} \times \textbf{Y}$

and easily verify that

One may hope that there is a different notion of largeness that captures this filter property. To discuss one such notion, we introduce the class of IP sets.

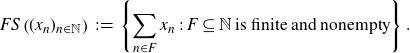

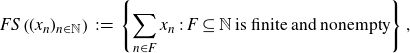

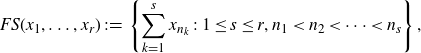

Let

![]() $(x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$

be a sequence in

$(x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$

be a sequence in

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. The finite sum set associated to

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. The finite sum set associated to

![]() $(x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$

is the set

$(x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$

is the set

\begin{align*} FS\left( (x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}} \right) \;:\!=\; \left\{ \sum_{n \in F}{x_n} \;:\; F \subseteq \mathbb{N}\;\text{is finite and nonempty} \right\}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*} FS\left( (x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}} \right) \;:\!=\; \left\{ \sum_{n \in F}{x_n} \;:\; F \subseteq \mathbb{N}\;\text{is finite and nonempty} \right\}.\end{align*}

We say that

![]() $A \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

is an IP set if

$A \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

is an IP set if

![]() $A \supseteq FS\left( (x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}} \right)$

for some infinite sequence

$A \supseteq FS\left( (x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}} \right)$

for some infinite sequence

![]() $(x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$

. A theorem of Hindman [

Reference Hindman28

] asserts that IP sets are partition regular:

$(x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$

. A theorem of Hindman [

Reference Hindman28

] asserts that IP sets are partition regular:

Theorem 1·16 (Hindman’s Theorem [

Reference Hindman28

, theorem 3·1]). Let A be an IP set. If A is finitely partitioned

![]() $A = \bigcup_{i=1}^r{C_i}$

, then for some

$A = \bigcup_{i=1}^r{C_i}$

, then for some

![]() $i_0 \in \{1, \dots, r\}$

,

$i_0 \in \{1, \dots, r\}$

,

![]() $C_{i_0}$

is an IP set.

$C_{i_0}$

is an IP set.

A set E is

![]() $\text{IP}^*$

if

$\text{IP}^*$

if

![]() $E \cap A \ne \emptyset$

for every IP set A. It follows from Theorem 1·16 that

$E \cap A \ne \emptyset$

for every IP set A. It follows from Theorem 1·16 that

![]() $\text{IP}^*$

sets have the filter property. From this point of view, the IP polynomial Szemerédi theorem is more satisfactory:

$\text{IP}^*$

sets have the filter property. From this point of view, the IP polynomial Szemerédi theorem is more satisfactory:

Theorem 1·17 ([

Reference Bergelson and McCutcheon13

, theorem 0·7]). Let

![]() $p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be integer-valued polynomials with zero constant term. Then for any ergodic invertible probability measure-preserving system and any

$p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be integer-valued polynomials with zero constant term. Then for any ergodic invertible probability measure-preserving system and any

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

, the set

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, the set

is

![]() $\text{IP}^*$

.

$\text{IP}^*$

.

Remark 1·18. For the linear pattern

![]() $p_i(n) = in$

, Theorem 1·17 follows from [

Reference Furstenberg and Katznelson23

, theorem A].

$p_i(n) = in$

, Theorem 1·17 follows from [

Reference Furstenberg and Katznelson23

, theorem A].

When bounding the size of the intersections from below, the filter property is no longer a straightforward consequence from considering product systems. Furthermore,

![]() $\text{IP}^*$

turns out to be too strong of a notion of largeness. (Indeed, in a skew-product system on the torus

$\text{IP}^*$

turns out to be too strong of a notion of largeness. (Indeed, in a skew-product system on the torus

![]() $\mathbb{T}^2$

, one can find a set A for which the set (1·1) fails to be

$\mathbb{T}^2$

, one can find a set A for which the set (1·1) fails to be

![]() $\text{IP}^*$

for small

$\text{IP}^*$

for small

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

.) However, we can use a slightly weaker notion that retains the filter property. Define the upper Banach density of a set

$\varepsilon > 0$

.) However, we can use a slightly weaker notion that retains the filter property. Define the upper Banach density of a set

![]() $E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

by

$E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

by

We say that E is almost

![]() $\text{IP}^*$

, or

$\text{IP}^*$

, or

![]() $\text{AIP}^*$

for short, if E can be written as

$\text{AIP}^*$

for short, if E can be written as

![]() $E = A \setminus B$

, where A is an

$E = A \setminus B$

, where A is an

![]() $\text{IP}^*$

set and B is a set with

$\text{IP}^*$

set and B is a set with

![]() $d^*(B) = 0$

. In [

Reference Bergelson and Robertson14

], it was shown that the set (1·3) in Theorem 1·7 is in fact a shift of an

$d^*(B) = 0$

. In [

Reference Bergelson and Robertson14

], it was shown that the set (1·3) in Theorem 1·7 is in fact a shift of an

![]() $\text{AIP}^*$

set.

$\text{AIP}^*$

set.

In a similar vein, Theorem 1·3 was strengthened in [

Reference Bergelson and Leibman9

]. There, the notion of largeness used is the even stronger notion of

![]() $\text{AVIP}_0^*$

, which we define in Section 5.

$\text{AVIP}_0^*$

, which we define in Section 5.

Theorem 1·19 ([

Reference Bergelson and Leibman9

, theorem 4·2]). Let

![]() $p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be linearly independent integer-valued polynomials with zero constant term. Then for any ergodic invertible probability measure-preserving system, any

$p_1, \dots, p_k \in \mathbb{Q}[x]$

be linearly independent integer-valued polynomials with zero constant term. Then for any ergodic invertible probability measure-preserving system, any

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and any

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

, and any

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

is

![]() $\text{AVIP}_0^*$

.

$\text{AVIP}_0^*$

.

In Section 5, we similarly strengthen the conclusions of Theorem A and Theorem B. In particular, we show that, if T is ergodic, then the sets (1·4), (1·5) and (1·6) are shifts of

![]() $\text{AVIP}_0^*$

sets (see Theorem 5·6 and Theorem 5·7).

$\text{AVIP}_0^*$

sets (see Theorem 5·6 and Theorem 5·7).

1·4. Combinatorial applications

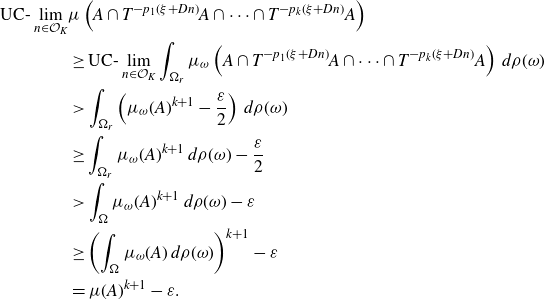

We deduce several combinatorial facts from the ergodic-theoretic theorems above. For some of the combinatorial results, we have stronger finitary versions. For other combinatorial facts derived from ergodic-theoretic results under the assumption of ergodicity, we cannot easily deduce finitary consequences. This distinction arises from subtleties in Furstenberg’s correspondence principle, which we discuss in more detail below. The first version of Furstenberg’s correspondence principle that we will use is as follows:

Theorem 1·20 ([

Reference Bergelson4

, theorem 4·17]). Fix a Følner sequence

![]() $\Phi = (\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

in

$\Phi = (\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

in

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Suppose

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Suppose

![]() $E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

has positive upper density along

$E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

has positive upper density along

![]() $\Phi$

, i.e.

$\Phi$

, i.e.

![]() $\overline{d}_{\Phi}(E) \;:\!=\; \limsup_{N \to \infty}{{|E \cap \Phi_N|}/{|\Phi_N|}} > 0$

. Then there exists an

$\overline{d}_{\Phi}(E) \;:\!=\; \limsup_{N \to \infty}{{|E \cap \Phi_N|}/{|\Phi_N|}} > 0$

. Then there exists an

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

![]() $(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and a set

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and a set

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

with

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

with

![]() $\mu(A) = \overline{d}_{\Phi}(E)$

such that, for any

$\mu(A) = \overline{d}_{\Phi}(E)$

such that, for any

![]() $k \in \mathbb{N}$

and any

$k \in \mathbb{N}$

and any

![]() $n_1, \dots, n_k \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, one has

$n_1, \dots, n_k \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, one has

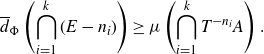

\begin{align} \overline{d}_{\Phi} \left( \bigcap_{i=1}^k{(E - n_i)} \right) \ge \mu \left( \bigcap_{i=1}^k{T^{-n_i}A} \right). \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline{d}_{\Phi} \left( \bigcap_{i=1}^k{(E - n_i)} \right) \ge \mu \left( \bigcap_{i=1}^k{T^{-n_i}A} \right). \end{align}

Applying Theorem 1·20 directly alongside Theorem A, we get the following:

Theorem 1·21.

Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

![]() $\{p_1, \dots , p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

be a jointly intersective family of linearly independent

$\{p_1, \dots , p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

be a jointly intersective family of linearly independent

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. Fix a Følner sequence

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. Fix a Følner sequence

![]() $\Phi = (\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

and suppose

$\Phi = (\Phi_N)_{N \in \mathbb{N}}$

and suppose

![]() $E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

satisfies

$E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

satisfies

![]() $\overline{d}_{\Phi}(E) > 0$

. Then for any

$\overline{d}_{\Phi}(E) > 0$

. Then for any

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

,

$\varepsilon > 0$

,

is syndetic.

Taking the natural Følner sequence

![]() $\Phi_N = \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

under the isomorphism

$\Phi_N = \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

under the isomorphism

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K \cong \mathbb{Z}^d$

, we deduce a related finitary result:

$\mathcal{O}_K \cong \mathbb{Z}^d$

, we deduce a related finitary result:

Corollary 1·22.

Let K be a degree d number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K \cong \mathbb{Z}^d$

. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K \cong \mathbb{Z}^d$

. Let

![]() $\{p_1, \dots , p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

be a jointly intersective family of linearly independent

$\{p_1, \dots , p_k\} \subseteq K[x]$

be a jointly intersective family of linearly independent

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. For any

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued polynomials. For any

![]() $\delta, \varepsilon > 0$

, there exists

$\delta, \varepsilon > 0$

, there exists

![]() $N = N(\delta, \varepsilon) \in \mathbb{N}$

such that: if

$N = N(\delta, \varepsilon) \in \mathbb{N}$

such that: if

![]() $A \subseteq \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

with

$A \subseteq \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

with

![]() $|A| > \delta N^d$

, then A contains at least

$|A| > \delta N^d$

, then A contains at least

![]() $(\delta^{k+1} - \varepsilon)N^d$

configurations of the form

$(\delta^{k+1} - \varepsilon)N^d$

configurations of the form

![]() $\{x, x + p_1(n), \dots, x + p_k(n)\}$

for some

$\{x, x + p_1(n), \dots, x + p_k(n)\}$

for some

![]() $n \ne 0$

.

$n \ne 0$

.

Proof. Let

![]() $\delta, \varepsilon > 0$

, and suppose no such N exists. That is, for some sequence

$\delta, \varepsilon > 0$

, and suppose no such N exists. That is, for some sequence

![]() $N_m \to \infty$

, we can find sets

$N_m \to \infty$

, we can find sets

![]() $A_m \subseteq \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

with

$A_m \subseteq \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

with

![]() $|A_m| > \delta N_m^d$

such that

$|A_m| > \delta N_m^d$

such that

for every

![]() $n \ne 0$

.

$n \ne 0$

.

By passing to a subsequence if necessary, we may assume

exists for all

![]() $r \in \mathbb{N}$

,

$r \in \mathbb{N}$

,

![]() $n_1, \dots, n_r \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, and

$n_1, \dots, n_r \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, and

![]() $i_1, \dots, i_r \in \{0, 1\}$

, where

$i_1, \dots, i_r \in \{0, 1\}$

, where

![]() $A_{m,0} = A_m$

and

$A_{m,0} = A_m$

and

![]() $A_{m,1} = \mathcal{O}_K \setminus A_m$

. Then we may define a measure on

$A_{m,1} = \mathcal{O}_K \setminus A_m$

. Then we may define a measure on

![]() $X = \{0,1\}^{\mathcal{O}_K}$

by letting

$X = \{0,1\}^{\mathcal{O}_K}$

by letting

and extending using Kolmogorov’s extension theorem. Note that the shift map

![]() $(T^nx)(m) = x(n+m)$

preserves the measure

$(T^nx)(m) = x(n+m)$

preserves the measure

![]() $\mu$

. Taking

$\mu$

. Taking

![]() $A = \{x \in X \;:\; x_0 = 1\}$

, we have

$A = \{x \in X \;:\; x_0 = 1\}$

, we have

and on the other hand,

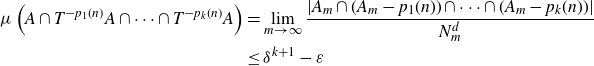

\begin{align*} \mu \left( A \cap T^{-p_1(n)}A \cap \dots \cap T^{-p_k(n)}A \right) & = \lim_{m \to \infty}{\frac{\left| A_m \cap (A_m - p_1(n)) \cap \dots \cap (A_m - p_k(n)) \right|}{N_m^d}} \\ & \le \delta^{k+1} - \varepsilon \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \mu \left( A \cap T^{-p_1(n)}A \cap \dots \cap T^{-p_k(n)}A \right) & = \lim_{m \to \infty}{\frac{\left| A_m \cap (A_m - p_1(n)) \cap \dots \cap (A_m - p_k(n)) \right|}{N_m^d}} \\ & \le \delta^{k+1} - \varepsilon \end{align*}

for

![]() $n \ne 0$

. This contradicts Theorem A.

$n \ne 0$

. This contradicts Theorem A.

Note that the system in Theorem 1·20 may not be ergodic. To obtain an inequality similar to (1·8) while ensuring that the system is ergodic, one needs to allow for replacing the density along

![]() $\Phi$

by the density along some other Følner sequence depending on the choice of translates

$\Phi$

by the density along some other Følner sequence depending on the choice of translates

![]() $n_1, \dots, n_k$

. (An example due to Hindman [

Reference Hindman29

] can be used to show that, for certain sets E, the measure-preserving system in the conclusion of Theorem 1·20 is necessarily non-ergodic; see the discussion following theorem 1·3 in [

Reference Bergelson and Ferré Moragues5

] for more detail.) Using the notion of upper Banach density, we can formulate an ergodic version of Furstenberg’s correspondence principle:

$n_1, \dots, n_k$

. (An example due to Hindman [

Reference Hindman29

] can be used to show that, for certain sets E, the measure-preserving system in the conclusion of Theorem 1·20 is necessarily non-ergodic; see the discussion following theorem 1·3 in [

Reference Bergelson and Ferré Moragues5

] for more detail.) Using the notion of upper Banach density, we can formulate an ergodic version of Furstenberg’s correspondence principle:

Theorem 1·23.

Suppose

![]() $E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

has positive upper Banach density. Then there exists an ergodic

$E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

has positive upper Banach density. Then there exists an ergodic

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-system

![]() $(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and a set

$(X, \mathcal{B}, \mu, T)$

and a set

![]() $A \in \mathcal{B}$

with

$A \in \mathcal{B}$

with

![]() $\mu(A) = d^*(E)$

such that, for any

$\mu(A) = d^*(E)$

such that, for any

![]() $k \in \mathbb{N}$

and any

$k \in \mathbb{N}$

and any

![]() $n_1, \dots, n_k \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, one has

$n_1, \dots, n_k \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, one has

\begin{align*} d^* \left( \bigcap_{i=1}^k{(E - n_i)} \right) \ge \mu \left( \bigcap_{i=1}^k{T^{-n_i}A} \right). \end{align*}

\begin{align*} d^* \left( \bigcap_{i=1}^k{(E - n_i)} \right) \ge \mu \left( \bigcap_{i=1}^k{T^{-n_i}A} \right). \end{align*}

For

![]() $\mathbb{Z}$

-actions, Theorem 1·23 appears in [

Reference Bergelson6

, proposition 3·1], utilising an observation of Emmanuel Lesigne based on the original argument of Furstenberg. For a general version in amenable groups (a class containing all countable abelian groups), see [

Reference Bergelson and Ferré Moragues5

, theorem 2·8].

$\mathbb{Z}$

-actions, Theorem 1·23 appears in [

Reference Bergelson6

, proposition 3·1], utilising an observation of Emmanuel Lesigne based on the original argument of Furstenberg. For a general version in amenable groups (a class containing all countable abelian groups), see [

Reference Bergelson and Ferré Moragues5

, theorem 2·8].

As a consequence, we obtain the following combinatorial version of Theorem 5·7:

Theorem 1·24.

Let K be a number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K$

. Let

![]() $p(x) \in K[x]$

be an

$p(x) \in K[x]$

be an

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued intersective polynomial. Let

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued intersective polynomial. Let

![]() $r,s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero. Then for any set

$r,s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero. Then for any set

![]() $E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

with

$E \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$

with

![]() $d^*(E) > 0$

and any

$d^*(E) > 0$

and any

![]() $\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon > 0$

, the set

is

![]() $\text{AVIP}_{0,+}^*$

(in particular, it is syndetic).

$\text{AVIP}_{0,+}^*$

(in particular, it is syndetic).

Moreover, if

![]() $\frac{s}{r} \in \mathbb{Q}$

, then

$\frac{s}{r} \in \mathbb{Q}$

, then

is

![]() $\text{AVIP}_{0,+}^*$

(in particular, it is syndetic).

$\text{AVIP}_{0,+}^*$

(in particular, it is syndetic).

As discussed above, the ergodicity assumption in Theorems B and 5·7 precludes us from easily deducing finitary results along the lines of Corollary 1·22. Nevertheless, we suspect that a finitary analogue holds, which we formulate below:

Conjecture 1·25.

Let K be a degree d number field with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K \cong \mathbb{Z}^d$

. Suppose

$\mathcal{O}_K \cong \mathbb{Z}^d$

. Suppose

![]() $p(x) \in K[x]$

is an

$p(x) \in K[x]$

is an

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued intersective polynomial.

$\mathcal{O}_K$

-valued intersective polynomial.

-

(1) let

$r, s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero. For any

$r, s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero. For any

$\delta, \varepsilon > 0$

, there exists

$\delta, \varepsilon > 0$

, there exists

$N = N(\varepsilon, \delta) \in \mathbb{N}$

such that: if

$N = N(\varepsilon, \delta) \in \mathbb{N}$

such that: if

$A \subseteq \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

with

$A \subseteq \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

with

$|A| > \delta N^d$

, then A contains at least

$|A| > \delta N^d$

, then A contains at least

$(\delta^3 - \varepsilon)N^d$

configurations of the form

$(\delta^3 - \varepsilon)N^d$

configurations of the form

$\{x, x + rp(n), x + sp(n)\}$

for some

$\{x, x + rp(n), x + sp(n)\}$

for some

$n \ne 0$

.

$n \ne 0$

. -

(2) let

$r, s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero such that

$r, s \in \mathcal{O}_K$

be distinct and nonzero such that

${s}/{r} \in \mathbb{Q}$

(or more generally, no two conjugates of

${s}/{r} \in \mathbb{Q}$

(or more generally, no two conjugates of

$\frac{s}{r}$

are negatives of each other). For any

$\frac{s}{r}$

are negatives of each other). For any

$\delta, \varepsilon > 0$

, there exists

$\delta, \varepsilon > 0$

, there exists

$N = N(\varepsilon, \delta) \in \mathbb{N}$

such that: if

$N = N(\varepsilon, \delta) \in \mathbb{N}$

such that: if

$A \subseteq \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

with

$A \subseteq \{1, \dots, N\}^d$

with

$|A| > \delta N^d$

, then A contains at least

$|A| > \delta N^d$

, then A contains at least

$(\delta^4 - \varepsilon)N^d$

configurations of the form

$(\delta^4 - \varepsilon)N^d$

configurations of the form

$\{x, x + rp(n), x + sp(n), x + rp(n) + sp(n)\}$

for some

$\{x, x + rp(n), x + sp(n), x + rp(n) + sp(n)\}$

for some

$n \ne 0$

.

$n \ne 0$

.

In the simplest case when

![]() $K = \mathbb{Q}$

and

$K = \mathbb{Q}$

and

![]() $p(n) = n$

, Conjecture 1·25 was posed as a question in [

Reference Bergelson6

] and verified in [

Reference Green25

, theorem 1·10] and [

Reference Green and Tao26

, theorem 1·12]. For more general linear patterns (the case

$p(n) = n$

, Conjecture 1·25 was posed as a question in [

Reference Bergelson6

] and verified in [

Reference Green25

, theorem 1·10] and [

Reference Green and Tao26

, theorem 1·12]. For more general linear patterns (the case

![]() $p(n) = n$

), closely related finitary results were recently established in [

Reference Berger, Sah, Sawhney and Tidor16, 32

].

$p(n) = n$

), closely related finitary results were recently established in [

Reference Berger, Sah, Sawhney and Tidor16, 32

].

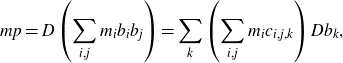

1·5. Outline of the paper

The structure of the paper is as follows. In Section 2, we collect several useful facts that will be used repeatedly in the proofs of the main theorems. Section 3 is devoted to proving Theorems C and D on characteristic factors corresponding to the polynomial configurations of interest via equidistribution results on nilmanifolds. Using the knowledge of characteristic factors, we prove Khintchine-type results (Theorems A and B in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 handles the refinements of our Khintchine-type theorems to conclude stronger combinatorial properties about the abundance of combinatorial configurations.

2. Preliminaries

2·1. Rational Kronecker factor

Recall that the Kronecker factor for an ergodic measure-preserving system is spanned by eigenfunctions. As suggested by the name, the rational Kronecker factor will be spanned by eigenfunctions with rational eigenvalues. To make this precise, we need to define what it means for an eigenvalue (a group character) to be rational.

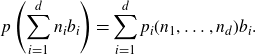

Since the additive group structure for the ring of integers in a degree d extension of

![]() $\mathbb{Q}$

is

$\mathbb{Q}$

is

![]() $\mathbb{Z}^d$

, we say that a character

$\mathbb{Z}^d$

, we say that a character

![]() $\chi \;:\; \mathbb{Z}^d \to \mathbb{T}$

is rational if there is an element

$\chi \;:\; \mathbb{Z}^d \to \mathbb{T}$

is rational if there is an element

![]() $(q_1, \dots, q_d) \in \mathbb{Q}^d$

such that

$(q_1, \dots, q_d) \in \mathbb{Q}^d$

such that

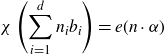

For notational convenience, we will let

![]() $e \;:\; \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{T}$

be the function

$e \;:\; \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{T}$

be the function

![]() $e(x) = e^{2\pi ix}$

so that we can write equation (2·1) in the more compact form

$e(x) = e^{2\pi ix}$

so that we can write equation (2·1) in the more compact form

for the usual dot product

![]() $\cdot$

on

$\cdot$

on

![]() $\mathbb{R}^d$

.

$\mathbb{R}^d$

.

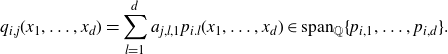

The property of rational characters that we will utilise later on is periodicity. Given a number field K with ring of integers

![]() $\mathcal{O}_K$

, we say that a character

$\mathcal{O}_K$

, we say that a character

![]() $\chi \;:\; \mathcal{O}_K \to \mathbb{T}$

is periodic, with period

$\chi \;:\; \mathcal{O}_K \to \mathbb{T}$

is periodic, with period

![]() $p \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, if for all

$p \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, if for all

![]() $n, m \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, we have

$n, m \in \mathcal{O}_K$

, we have

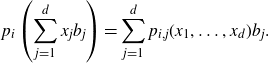

To translate this back into language where rationality makes sense, take an integral basis

![]() $\{b_1, \dots, b_d\}$

so that

$\{b_1, \dots, b_d\}$

so that

![]() $(\mathcal{O}_K,+) \cong \bigoplus_{i=1}^d{\mathbb{Z} \cdot b_i}$

. Since

$(\mathcal{O}_K,+) \cong \bigoplus_{i=1}^d{\mathbb{Z} \cdot b_i}$

. Since

![]() $\widehat{\mathbb{Z}^d} \cong \mathbb{T}^d$

, there is an element

$\widehat{\mathbb{Z}^d} \cong \mathbb{T}^d$

, there is an element

![]() $\alpha \in \mathbb{T}^d$

so that

$\alpha \in \mathbb{T}^d$

so that

\begin{align*} \chi \left( \sum_{i=1}^d{n_ib_i} \right) = e(n \cdot \alpha)\end{align*}

\begin{align*} \chi \left( \sum_{i=1}^d{n_ib_i} \right) = e(n \cdot \alpha)\end{align*}

for

![]() $n \in \mathbb{Z}^d$

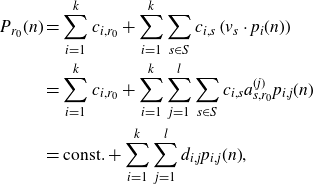

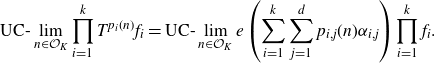

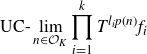

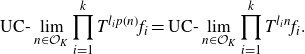

. We can then say that