1 Introduction

Despite a widespread and ongoing perception of the ‘socialist bloc’ as a homogenous entity, demographers and sociologists had demonstrated by the late 1980s that the nations involved did not have uniform reproductive and population policies.Footnote 1 While several countries, including Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Yugoslavia, followed the USSR’s lead in the mid-1950s and liberalised abortion laws, others continued to strictly limit access to terminations. Legal requirements were only relaxed in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) during the late 1960s and in Albania after the collapse of communism, while one of the most liberal abortion policies in Europe, enacted in Romania during 1957, was replaced by the notoriously oppressive Decree 770 a decade later. Attitudes to contraception also diverged. Demographers have reported that in many state-socialist countries, such as Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Soviet Russia, abortion was the primary method employed to limit family size.Footnote 2 In Russia in particular, contraceptives were viewed with suspicion by both doctors and women, perhaps due to the virtual nonexistence of family planning advice services and limited access to the pill and IUD.Footnote 3 Yet, these modern contraceptive methods were widely distributed and easily available in other state-socialist countries, including the GDR, Yugoslavia and Hungary, where various forms of public family planning advice centres functioned within socialist health systems.Footnote 4

Family planning policies and practices in Poland only partially mirrored the models and activities in other ‘bloc’ countries. With abortion initially legalised in 1956, the addition of a 1959 decree had made the procedure practically available on demand, with state hospitals admitting women for terminations free of charge. However, doctors and family planning activists involved in popularisation of family planning consistently depicted abortion as a dangerous surgery that should only be used as a last resort, and recommended contraception as the preferable alternative.Footnote 5 In fact, from the late 1950s onwards, Polish authorities declared the provision of contraceptive advice and products a public health priority.

Additions to the 1956 law obliged doctors who performed terminations, whether in public hospitals or private surgeries, to instruct women about contraception, and legislated for the creation of a network of well-woman clinics, Poradnie K (kobiety [women]), as the main sites for this instruction. In addition, a voluntary association founded under the auspices of the Ministry of Health in 1957, the Society for Conscious Motherhood (henceforth Society), went on to open their own clinics, supplying birth control advice for a modest fee. The Cold War notwithstanding, the Society maintained a close relationship with Western family planning organisations such as the British Family Planning Association, from the mid-1950s, and the International Planned Parenthood Federation, becoming a member in 1958. The Polish Catholic Church also provided followers with information through pre-marital courses and Church family advice, including advice on which methods were Church-approved and which were not.

This article examines the development of different models of family planning advice in state-socialist Poland after 1956 using a wide range of print and archival sources. Apart from local press or Polish and international professional literature on family planning, in our scrutiny we rely on the publications of the Society such as manuals and brochures, a bi-monthly Problemy Rodziny [Family Issues], archival collections of local branches of the Society in Cracow and Poznań as well as the collection of the Ministry of Health and of Educational Film Studios in Lodz. For our analysis of Catholic ‘responsible parenthood’ advice, we use published manuals on marriage and family planning aimed at Catholic spouses and archival materials, including brochures, scripts and programmes located in the collection of the Department of the Chaplaincy of Families of the Cracow Metropolitan Curia Archive and the archival collection of the Section of the Families of Warsaw Catholic Intelligentsia Club.

Our article examines the relations between different models of family planning advice and their evolution in subsequent decades of state socialism, as well as their similarities and dissimilarities, conflicts and concordances. While commercial medical practice existed in state-socialist Poland and gynaecologists delivered family planning advice in private surgeries and medical cooperatives, this paper focuses on services designed to be accessible and universal – those sponsored, in a broad sense, by the State and by the Catholic Church. We argue that reciprocal influence and emulation existed between state-sponsored and Catholic family planning in state-socialist Poland, and that both models used transnational organisations and debates relating to contraception for their construction and legitimisation.

By evaluating the extent to which the strategies and practices for the delivery of birth control advice utilised by transnational birth control movements were employed in a ‘second world’ context such as Poland, we reveal unexpected supranational links that complicate and problematise historiographical and popular understandings of the Iron Curtain and Cold War Europe. We situate our work alongside emerging scholarship that places the previously neglected region of Central and Eastern Europe within the international history of family planning movements.Footnote 6

The majority of scholarship on family planning advice has focused on birth control clinics established in Europe and the United States by voluntary organisations and social movements for birth control, during the inter-war years and the decades following the Second World War.Footnote 7 Historians of the United States have emphasised the voluntary and charitable character of clinic provision, its functioning in ‘the market of birth control’, and the salient role of local organisations in establishing and running birth control advice centres.Footnote 8 A similar approach can be noted in scholarship on family planning advice in inter-war Europe highlighting the early initiatives of such prominent birth control movement leaders as Marie Stopes in Great Britain.Footnote 9 Recent work in British and Irish historiography has explored the roles played by a tradition of voluntary activism, the presence of women doctors and opposition by the Catholic Church in local-level birth control advice initiatives.Footnote 10 Little attention has been paid to more recent developments influenced by 1967 legislation that made abortion accessible or the free provision of contraceptive advice by local medical authorities operating within the National Health Service since 1972.Footnote 11 The role of state-funded medicine in family planning advice is a distinct historiographical gap that needs to be filled. Our article, albeit addressing the issue in a different political context, is intended to stimulate discussion in this area.

Scholarly debate relating to post-1945 developments in international family planning has largely been dominated by the so-called ‘overpopulation’ paradigm. While for the inter-war years historians have stressed the presence of eugenic discourse in birth control propaganda and collaboration between eugenicists and birth control proponents,Footnote 12 publications on international family planning initiatives since the 1950s have emphasised the efforts of ‘first world’ countries to control ‘third world’ populations.Footnote 13 Matthew Connelly’s influential Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population, published in 2008, has particularly dominated discussions of post-war family planning developments.Footnote 14 Purportedly a ‘global history’ and advertised as such, Fatal Misconception entirely ignores the Soviet bloc and the presence and role of socialist countries in the international movement for planned parenthood. More recent scholarly insights into this topic, such as Figuring the Population Bomb by Carol R. McCann, do not go beyond a ‘first world’/‘third world’ dichotomy despite efforts to embrace gender perspectives.Footnote 15 Our article sheds light on developments in the previously underrepresented region and prompts an evaluation of post-Second World War paradigms in research on family planning initiatives. One such emerging paradigm is ‘transnationalism’, a scholarship to which our paper is intended to contribute.Footnote 16

With regard to Poland, while research pertaining to twentieth-century reproductive and population policies has recently increased, this has tended to focus predominantly on inter-war debates and the movement for ‘conscious motherhood’, as birth control was euphemistically entitled.Footnote 17 Scholarly discussion on reproductive politics in the post-1945 years has so far concentrated on abortion, pro-natalism and the provision of contraceptives, particularly the oral contraceptive pill.Footnote 18 Likewise, while the history of twentieth-century intersections between Catholicism and contraception have attracted increasing attention from scholars in America,Footnote 19 and more recently Europe,Footnote 20 Catholic family planning in state-socialist countries – Poland included – has, with a few exceptions,Footnote 21 been particularly neglected, and restricted to memoirs or theological reflexions by priests and doctors involved in shaping the theoretical background and local provision of ‘family advice’ by the Polish Catholic Church from the mid-1950s onwards.Footnote 22 While these academic and non-academic accounts shed a degree of light on the development of Catholic family planning advice in post-war Poland, the full history awaits systematic study.

2 Secular Family Planning Advice: Public Healthcare and the Polish Family Planning Organisation

The Society for Conscious Motherhood played a pivotal role in the early years of family planning advice in state-socialist Poland. Comprised of birth control enthusiasts, the Society developed and subsequently attempted to implement a model of family planning advice throughout the health care system. In this section, following a brief introduction to the organisation and its international associations, we present the tenets of secular family planning advice the Society attempted to disseminate across Poland. We also discuss legislation pertaining to contraceptive advice in the public health care system and the implementation of birth control advice in well-woman clinics. Moreover, we describe the development of the Society’s own birth control clinics, initiated at the turn of the 1960s and expanded during the 1970s. Finally, we focus on the difficulties the Society and its clinics encountered with the ascendency of Catholic contraceptive doctrine in Poland during the 1980s, and the Society’s response.

Family planning advice centres were initially established in Poland during the 1930s by voluntary organisations, and doctors and activists from socialist, eugenic and literary backgrounds.Footnote 23 Many of these inter-war birth control advocates would also be involved with the Society during the 1950s, driving cooperation with gynaecologists and family planning advocates in Western Europe. Even before this time, many of the Polish doctors who would later fill Society ranks were liaising with the Family Planning Association (henceforth FPA) of Great Britain.Footnote 24 Barbara Evans, biographer of FPA leader Helena Wright, has argued that Wright’s visit to Warsaw in November 1957 directly contributed to the decision to restart a Polish family planning association.Footnote 25 Over the following years, Society gynaecologists and lay leaders from various branches visited London, testing Polish contraceptive devices at FPA headquarters and learning about the British association’s activism and operation.Footnote 26 As Evans claims, the structure and organisation of the Society and its clinics emulated a British model that emphasised a broad and holistic approach to reproductive health.Footnote 27

Almost since its founding, the Society also had close ties with the most prominent transnational family planning organisation at the time: the International Planned Parenthood Federation (henceforth IPPF). Established in India in 1952, IPPF had become the hub of population and reproductive policies for the global family planning movement.Footnote 28 In 1958, forsaking organisations in other state-socialist countries, the Society became affiliated with the IPPF region of Europe–Near East–Africa, the headquarters of which were situated in London.Footnote 29 As a result, the Society benefited from the international transfer of contraceptive information from its early years, acquiring contraceptive know-how and establishing contacts with Western birth control activists despite Cold War conditions.

As Society president Marcin Kacprzak emphasised, the association was not intended to create its own clinic network but rather develop family planning advice in close cooperation with the public health care system and ‘maintain and propagate the policies of the state’. The objective was to ‘advise and aid state health care institutions’ that were providing contraceptive information to Polish women. The provision of contraception – a requirement for the social health service after a number of regulations following the 1956 abortion law – was inscribed in the public health narrative of preventive medicine, promoted as the desirable alternative to abortion.Footnote 30

The 1959 Executive Order to the 1956 abortion law, which simplified the procedure of referring a woman for a termination, obliged the doctor issuing the referral to inform her about contraceptive methods, prescribe a suitable method, inform her about the necessity of post-abortion check-up and of visiting a women’s and ‘conscious motherhood’ clinic.Footnote 31 The Ministry of Health, renamed the Ministry of Health and Social Assistance (henceforth MHSA) in 1960, also issued instructions in 1957, 1960 and 1963 concerning the setting up of permanent contraceptive vending points in outpatient women’s health clinics within the public system.Footnote 32

At the turn of the 1960s, the early years of family planning campaigning in state-socialist Poland, healthcare authorities and Society members designed a two-level system of state family planning advice. The higher tier consisted of eighteen ‘conscious motherhood’ clinics, one in each voivodeship, to demonstrate exemplary practices and control lower-echelon institutions advising patients about contraception. In the first years of clinics’ functioning they were intended primarily for women (as the concept of ‘conscious motherhood’ implies) and expected mainly married women to be the patients. The ‘conscious motherhood’ clinics cooperated closely with the Society, often operating in the same premises as their local offices. Society doctors, among whom were both men and women, also provided contraceptive advice in voivodeship clinics, propagating the tenets of birth control advice developed by the Society.Footnote 33

In booklets intended for doctors published during the early 1960s by acclaimed Society gynaecologists, such as Jan Lesiński or Michalina Wisłocka,Footnote 34 one can find the main principles of contraceptive advice adopted by the lower-level state family planning institutions, the Poradnie K (well-woman clinics) and hospital maternity wards. Well-woman clinics that provided general gynaecological care were deemed particularly appropriate places for disseminating birth control propaganda and information. These were midwives and gynaecologists, and not general practitioners, who were to provide contraceptive advice to women as, in state-socialist Poland, trained gynaecological practitioners advised women on reproductive health issues. The number of outpatient clinics addressing women’s needs – understood as reproductive health – increased steadily after the Second World War, and by 1971 had doubled, with over 1300 in operation and eight million registered consultations.Footnote 35 The development of these clinics – freestanding or attached to primary healthcare facilities, outpatient clinics in regional and university hospitals, and clinics established to serve particular groups of women: namely factory workers and students – was symptomatic of intense investment in boosting maternal health and diminishing neonatal mortality, both declared top public health priorities in Poland during and beyond the six-year plan (1950–55).Footnote 36

From the beginning of the 1960s, well-woman clinics thus took on the additional role of contraceptive advice. Society doctors such as Lesiński clearly preferred channelling contraceptive advice through Poradnie K, as visiting a clinic specialising solely in contraception could ‘be troublesome and embarrassing for women, especially in rural contexts’.Footnote 37 However, as Wisłocka insisted, family planning advice should be offered during specific hours, and separately from general gynaecological advice so as not to intimidate women seeking contraceptive advice.Footnote 38 How to put patients not accustomed to family planning at ease was a foremost concern in the early years of birth control advice in Poland.

In their publications, both Wisłocka and Lesiński highlighted the primary role of gynaecologists in the family planning facility. Having performed a gynaecological exam, they would then select the most appropriate birth control method for the patient, preferably fitting a barrier contraceptive device (a cap or a diaphragm), prioritised by the Society during the 1960s.Footnote 39 The role of teaching the patient how to use the device correctly, however, was relegated to a midwife: the second crucial medical professional a patient would encounter in family planning advice at a well-woman clinic. Midwives, apart from providing patients with device instructions and filling in specially designed patient cards, were also designated to run the mandatory contraceptive vending points. Immediate access to birth control devices and products in well-woman clinics was regarded as one of the prerequisites for contraceptive success: again, there was concern about the potential embarrassment for patients having to purchase contraceptives outside the clinic.Footnote 40 Moreover, women were advised to return in a fortnight in case their contraceptive devices required adjustment and attend twice-yearly follow-up appointments.Footnote 41 This protocol was intended to entrench the medicalisation of birth control, one of the tenets of contraceptive advice in Poland at that time, as it was in Western Europe and North America.Footnote 42

As Wisłocka acknowledged in her 1959 publication, the network of state family planning advice facilities at that time was still in its infancy.Footnote 43 One of the most crucial organisational issues was the training of doctors in contraceptive advice. This was undertaken at two facilities established by the Society in Warsaw and Cracow. The Warsaw clinic was opened in 1958. Four years later the Cracow branch opened in the renovated part of an historic building called the ‘Grey House’ (Szara Kamienica), situated in an extremely privileged location at the very heart of the city: Rynek Główny.Footnote 44 In the early years, female and male doctors and lay activists were told to prioritise establishing contraceptive advice in the central and northern part of Poland (Warsaw clinic) as well as the southern region of the country (Cracow clinic). With the onset of the ‘conscious motherhood’ campaign, the two Society clinics were also to provide birth control advice, rarely available in the public health sector at that time.

While well-woman clinics and voivodeship ‘conscious motherhood’ centres admitted patients free of charge, the Society charged for the advice they provided – in the late 1950s, the fee was 10 złotys.Footnote 45 This amount was equal to the cost of a six-unit box of one locally manufactured condom brand, Eros,Footnote 46 and can be considered a relatively modest one if compared to the average salary in 1960, which amounted to 1560 złotys.Footnote 47 In this regard, Society’s family planning advice clinics functioned at the intersection of public and private medicine. The latter, due to doctors’ shortages and patients’ demand, had never been completely eliminated in state socialist Poland. Prices for contraceptive advice in the clinics fluctuated but remained affordable for the majority of patients and became a competitive alternative to the increasing number of gynaecologists establishing private practices during the 1980s.Footnote 48 The Society clinics were closely associated with the state healthcare system. Doctors providing advice in the Society’s clinics were officially state employees and could not exceed the state-mandated working hours and salaries, resulting in frequent personnel shortages.Footnote 49 The Cracow facility was subsidised by the state; in the early years government funding amounted to 78% of the clinic’s revenue, but decreased to 22% in the ensuing years.Footnote 50 During the 1960s this clinic also received subsidies from the Society, before the board insisted the Cracow facility needed to become financially independent.Footnote 51 The ‘Grey House’ clinic was at a disadvantage compared to the self-sufficient Warsaw facility, which relied not only on patient fees but also the earnings of the state-dependent but Society-controlled manufacturer of contraceptives, ‘Securitas’.Footnote 52

The Society clinics were also intertwined with state-socialist medicine with regard to the patients that came for contraceptive advice. In the years after contraceptive advice following termination became mandatory, the Society’s clinics largely received hospital-referred abortion patients. Over the ensuing years, however, as emphasised by Cracow clinic personnel, they succeeded in drawing patients actively seeking contraceptive advice to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Patient numbers increased to such an extent that by 1970 the Cracow clinic was struggling to meet demand.Footnote 53 In the mid-1980s, the ‘Grey House’ clinic was receiving around 67 000 patients a year and was prevented from expanding this number only by a shortage of space.Footnote 54

The Society clinics also disseminated contraceptive information beyond Warsaw and Cracow, replying to queries by phone and post. A number of voivodeship ‘conscious motherhood’ facilities, including those in Poznan, Lodz and Opole, adopted similar methods of contraceptive propaganda.Footnote 55 Shortly after the opening of the Society facility at Plac Trzech Krzyży, a ‘corresponding’ ‘conscious motherhood’ clinic was also opened in Warsaw. In the first two years of its existence, personnel replied to over 22 000 letters, around half of which were seeking advice on contraception.Footnote 56 As highlighted by the Society activist and doctor, Jadwiga Beaupre, letters were often sent by people who were too embarrassed to visit a clinic, or who lived in rural areas without access to contraceptive advice.Footnote 57 As historian Ewelina Szpak has detailed, the ‘conscious motherhood’ campaign had limited success in the countryside.Footnote 58 The corresponding clinic also circulated millions of Society brochures and booklets,Footnote 59 which may have gone some way to bridge the urban/rural divide.

As well as the aforementioned training of gynaecologists and providing patients with contraceptive advice, the Warsaw and Cracow Society clinics fulfilled several other roles. The Cracow facility instructed midwives and students of medicine, midwifery and nursing about contraception up until the end of the 1980s.Footnote 60 The Warsaw clinic specialised in researching contraceptive methods as well as testing newly developed contraceptive devices and products made by ‘Securitas’ and other local manufacturers.Footnote 61 One such product was the Polish contraceptive pill Angravid, the reliability and side effects of which were tested on the clinic’s patients.Footnote 62 Clinic personnel and Society activists in general also encouraged and then supervised the dissemination of contraceptive advice in well-woman clinics.

In a 1972 report summarising the first fifteen years of activism, the Society took pride in its leading role in preparing the public health service for family planning advice, particularly during the early years: ‘Between 1957 and 1958 public healthcare was not taking action, because it was unprepared. Doctors lacked experience; there was no professional or popular literature for doctors and women. Doctors themselves did not know which contraceptive products were available.’Footnote 63 Although later superseded by a more organisational role, the training of doctors in family planning advice had been the Society’s main task. Over the following years the Society’s regional authorities had visited the public well-woman clinics to supervise their family planning provision. This did not always go down well with local doctors, or healthcare inspectors, who deemed family planning a minor issue compared to other problems the public healthcare system had to face.Footnote 64

Reports on the activities of Poradnie K published in medical journals and by the Society suggest that despite the legal obligation to provide contraceptive advice and products, compliance varied according to the motivations of local staff, a situation that appears to have endured throughout the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. ‘Some Poradnie K can be proud of their high sales. In others, the results are modest’, wrote physician Zbigniew Tarnawski in 1967 in an article published in the foremost Polish journal for gynaecology and obstetrics, Ginekologia Polska.Footnote 65 Several reports by the Cracow branch of the Society, published four years earlier, had highlighted a lack of interest among local doctors in providing contraceptive training, and the fact that some midwives, rather than promoting the more effective but time-consuming-to-fit diaphragms and cervical caps, were recommending easy to use but less reliable spermicides.Footnote 66 One of the six Poradnie K located in smaller towns that Society activists visited in 1963 had not established a contraceptive vending point, apparently this was ‘due to a lack of patient interest’: however, as the Society report explained, the local midwife was ‘hostile towards contraceptive propaganda’. In two of the other Poradnie K clinics, doctors were fitting patients with diaphragms, and one devoted every Saturday to family planning consultation.Footnote 67

Similar discrepancies were also noted in Poznań. A 1970 report highlighted disparities between Poradnie K clinics in contraceptive sales: while some failed to establish the service, others were selling dozens of thousand złotys’ worth of contraceptives.Footnote 68 A possible reason for this, a local branch activist argued, could be overburdened midwives: also expected to become involved in STD prevention, they had little time left to deal with contraceptive advice.Footnote 69 Other midwives, however, saw running vending points as an opportunity to increase their income, as they received commission from the sales of contraceptive products, books and booklets.Footnote 70

A recurrent trend that Society activists noted in their reports on family planning advice during the 1960s was voivodeship ‘conscious motherhood’ facilities taking over the contraceptive role previously carried out by well-woman clinics. Faced with reluctant Poradnie K doctors and midwives, patients increasingly sought contraceptive advice at the voivodeship centres: these were often run by Society members who were far more likely to prescribe the most effective barrier contraceptives (the contraceptive pill and the IUDs became available to a larger extent from late 1960s onwards).Footnote 71 As Society member Leokadia Grabowiecka pointed out, not only were women seeking birth control advice being provided with reliable products and devices, this could contribute to a further demobilisation of those gynaecologists reluctant to offer contraception.Footnote 72

One of the reasons for disparities and problems with contraceptive advice in outpatient women’s clinics may have been the apparent lack of systematic supervision by the Ministry of Health and Social Assistance. It is doubtful the MHSA insisted the regulations concerning family planning advice were being put into practice, or even collected data on whether contraception was being offered in public clinics. Ministry reports on the activities of these clinics, covering the period between 1959 and 1988 and located in the Central Archive of Modern Records in Warsaw, only include the provision of contraceptive advice twice: in the 1962 and 1963 reports, both in relation to consultations with pregnant women. According to these reports, 350 000 and 400 000 patients respectively received birth control advice, amounting to around thirty per cent of the pregnant women seeking prenatal care in these clinics.Footnote 73 The evident paucity of contraceptive advice in outpatient women’s clinics and the MHSA’s lack of interest in encouraging family planning advice in such amenities may have contributed to the expansion of Society facilities during the 1970s, a development that will be discussed later in this paper.

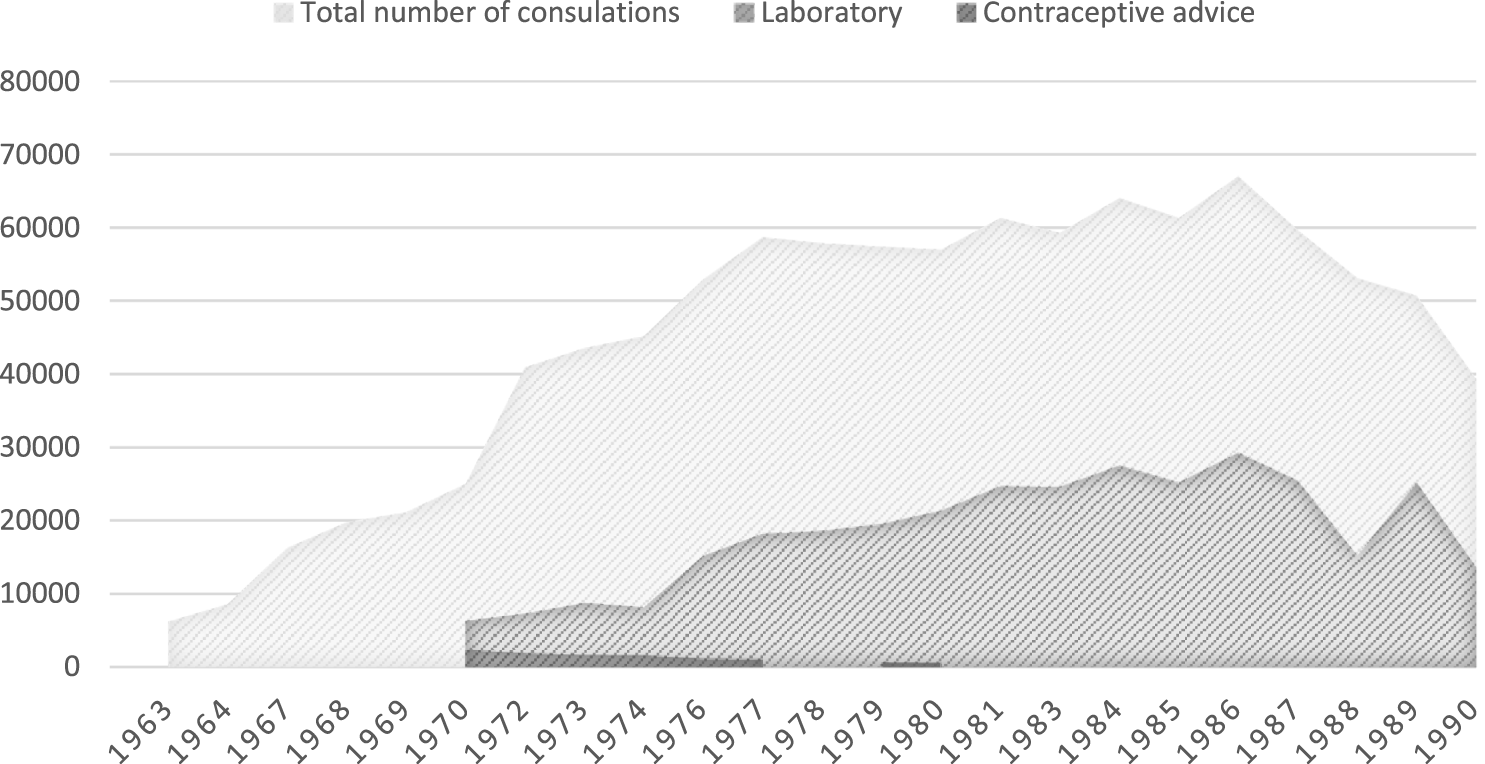

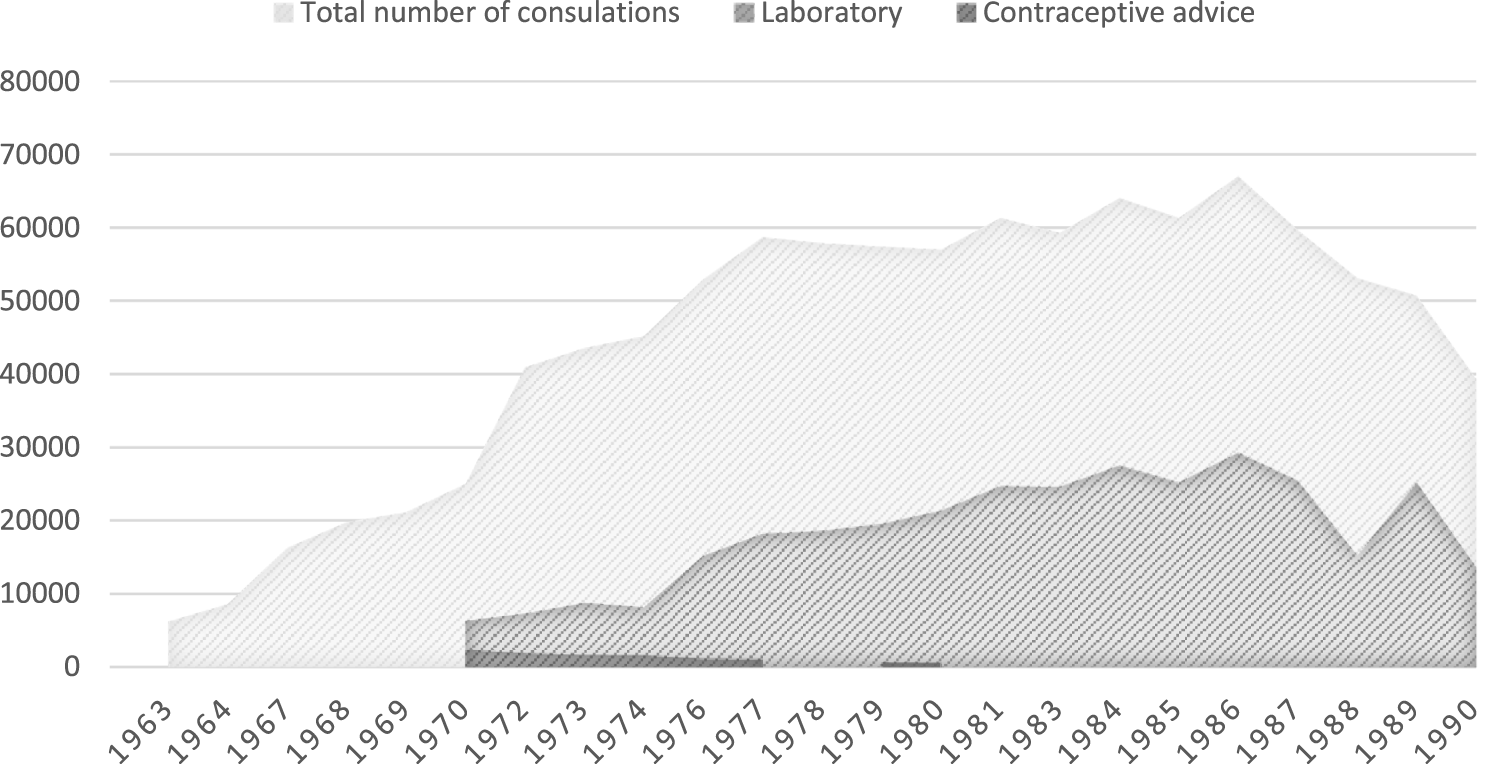

The Society’s clinics established at the turn of the 1960s provided a wide range of advice on reproductive health. It is likely the Society was influenced to adopt such a holistic approach to sexuality and reproduction by the ‘trainer’ of Society doctors and lay activists: the British Family Planning Association.Footnote 74 As was common practice in England, as well as contraceptive advice the Cracow and Warsaw Society clinics provided pre-marital, marital and family advice, sexual education, infertility treatment and access to a trained sexologist, a lawyer and an educator. Moreover, Society clinic doctors could conduct check-ups, run laboratory tests for their female patients and treat minor gynaecological ailments.Footnote 75 The affordability of these services drew a sizeable number of patients, and, at the Cracow clinic, demand for family planning information had been overtaken by requests for other types of advice by the mid-1960s (figure 1).

Figure 1: Consultations in Doctor’s Specialist Clinic in Cracow, 1963–90. Data from SFPC – NAC 29/1435/0/20; 29/1435/0/31; 29/1435/0/34-41; 29/1435/0/44-47; 29/1435/0/50-51.

This trend, particularly visible during the 1970s and 1980s, may have resulted from several discrepant factors. First and foremost, it manifested a diminishing emphasis on ‘conscious motherhood’ and a growing concern with family-related matters, emblematised by the many changes in the association’s name. Functioning since 1970 as the Society for Family Planning and since 1979 as the Society for Family Development (SFD), the organisation opened several new clinics during the 1970s. A number of these provided highly specialised and comprehensive medical advice from gynaecologists, sexologists and psychologists and thus mirrored the profile of the Cracow and Warsaw clinics. For a fee, the new facilities advised patients on contraception, infertility, gynaecological ailments and sexual dysfunctions. Six of these dispensaries, along with the Warsaw and Cracow facilities, were termed ‘Doctors’ Specialist Clinics’ (Lekarskie Przychodnie Specjalistyczne). Some had been developed from earlier voivodeship ‘conscious motherhood’ clinics, such as the facility in Poznan, which continued its earlier initiatives under the Society, providing contraceptive advice over the phone and in cooperation with a local newspaper.Footnote 76 All the new clinics were set up in voivodeship capital cities and continued functioning until the early 1990s.Footnote 77

The Society started to place more emphasis on pre-marital and family clinics as well as youth counselling. In the 1970s and 1980s they opened twenty-five such facilities in large cities and mid-sized towns.Footnote 78 The clinics provided sexual and psychological advice free of charge; the sexologist at the Warsaw youth counselling facility provided information and instruction over the phone and by post, answering letters sent by young people throughout Poland.Footnote 79 The Society’s pre-marital and youth counselling clinics also offered contraceptive advice but this was only a small part of the information provided: around twenty per cent for the Poznan clinic.Footnote 80 Undeniably, the opening of new clinics significantly expanded the Society’s activism and facilitated outreach to new patients, with numbers reaching around 250 000 a year.Footnote 81 When Martial Law was imposed towards the end of 1981, state authorities planned a further increase in pre-marital and family counselling clinics, reserving a sizeable sum of money in the state budget for twenty new facilities.Footnote 82 This initiative did not materialise, however, foreshadowing the stagnation and ultimate demise of the Society’s clinics during the 1980s.

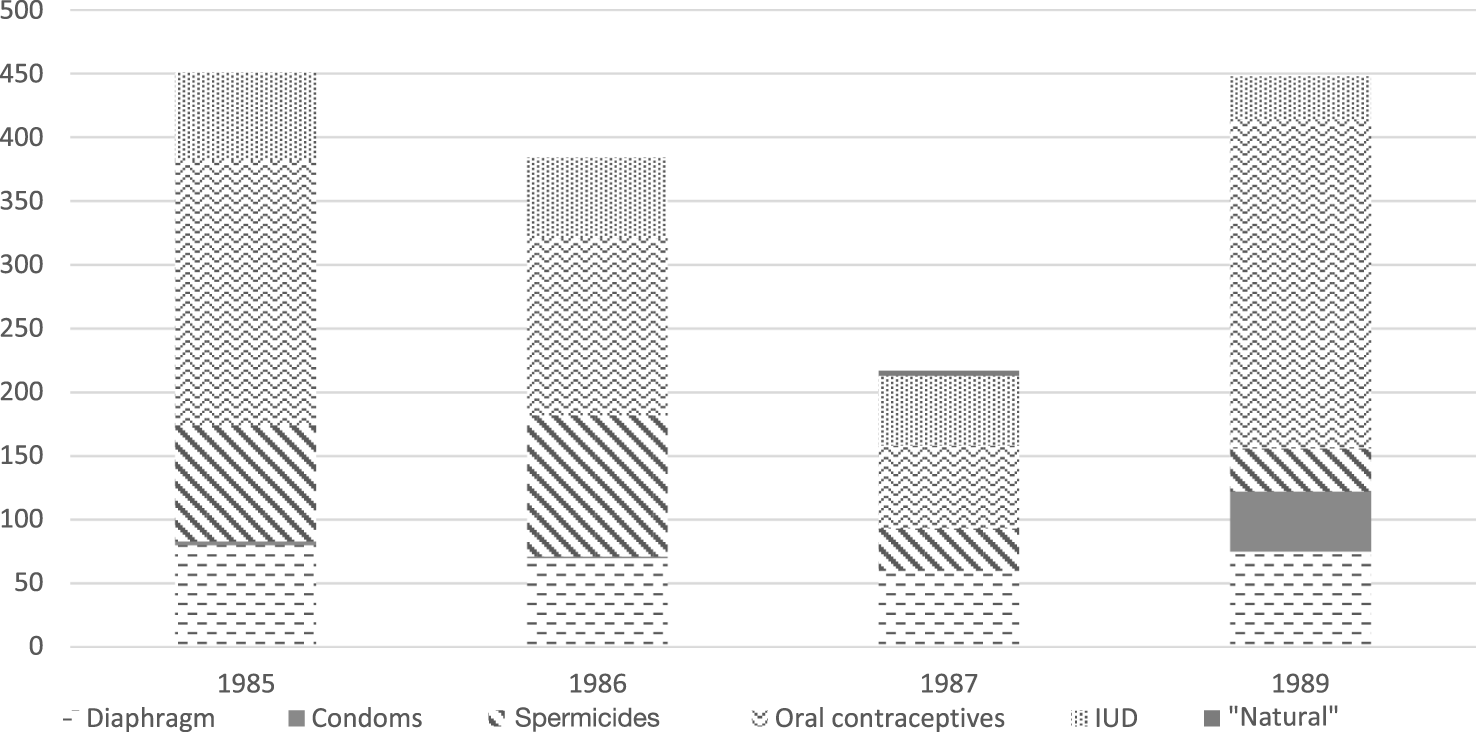

The decreasing importance of birth control advice in the Cracow clinic may also have related to the fluctuating availability of contraceptive products in the centrally-planned economy. At times, the Society’s clinics were able to offer clients modern contraceptives that were often unavailable elsewhere. From the late 1960s onwards the ‘Grey House’ clinic was one of the first places to prescribe the Lippes Loop IUD.Footnote 83 At the Poznan Doctors’ Specialist Clinic, the pill was the most frequently prescribed birth control method during the 1980s (figure 2). By providing IUDs and the pill, the Society’s clinics were often viewed as attractive and more affordable alternatives to private gynaecology practices, the small number of university clinics or the chain of hard currency shops (Pewex) that supplied goods otherwise unobtainable on the Polish market.Footnote 84 More often, however, clinic personnel complained about shortages of contraceptive products and devices. A 1975 report penned by doctors at Cracow linked the small amount of family planning advice carried out at the clinic to the scarcity of condoms, diaphragms and IUDs. The Society’s doctors and activists also consistently complained about the quality of barrier contraceptives (1960s onwards) and IUDs (1970s onwards) manufactured in Poland.Footnote 85

Figure 2: Contraceptive methods recommended in SFD Doctors’ Specialist Clinic in Poznan during the late 1980s. Data from SFPC – NAP, 54/4809/20.

In the last decade of state-socialism in Poland, the Society and their clinics reached crisis point. Following the ‘Solidarity’ revolution, the Society lost one-third of its members and was, as Andrzej Kulczycki has stated, ‘neglected by the socialist state’.Footnote 86 Several obstacles faced during the 1980s significantly decreased the number of clinics providing advice.Footnote 87 The Cracow facility suffered not only due to a lack of space, personnel and contraceptives, but also because the antique building that hosted it required constant renovation.Footnote 88 At least since the late 1980s the Cracow clinic had competed for patients with a Catholic family planning service, provided daily in the nearby St Mary’s Basilica.Footnote 89 This competition is emblematic of the 1980s, when the Catholic Church’s teachings on family planning became increasingly mainstreamed as Church and state population policies became aligned.

Rivalry with Catholic advice may be one of the reasons the Society’s teachings on contraception were re-oriented. At the Society’s conventions during the 1980s, attendees emphasised the need to acknowledge the Catholic affiliation of the majority of their potential patients.Footnote 90 Over the previous decades, the Society’s attitude towards church-approved ‘natural family planning’ had been largely critical, despite one of the founders, Jan Lesiński, praising the rhythm method as ‘the most ethical and moral birth control method’ back in 1959. In the following decades the Society produced material for a general audience describing the principles of the rhythm method, encouraging women to learn to understand their menstrual cycle, their fertile and infertile periods. At the same time, this literature discouraged women from relying on the rhythm whatsoever or recommended adding an additional contraceptive – such as a barrier and spermicide – around the expected ovulation date.Footnote 91 Through the 1980s, the Society’s clinics increasingly began to provide instructions in ‘natural family planning methods’, such as the Billings ovulation method, based on observation of changes in cervical mucus.Footnote 92 The Society’s approach to ‘natural family planning’, however, differed significantly from the one of the Catholic advice with its stress on ‘natural family planning methods’ being a part of a larger holistic philosophy of a Catholic life style. During the democratic transition, when the Catholic Church’s influence on reproductive matters considerably expanded,Footnote 93 the Cracow clinic personnel deemed the Billings method to be ‘particularly suitable for young women’.Footnote 94

The problems with contraceptive provision the Society faced during the last decades of its activities also complicate evaluation of its functioning within the International Federation for Planned Parenthood. Although admitted to the IPPF as a voluntary association, throughout the 1970s and 1980s the Society depended on the fluctuating support of the state that in the 1970s adopted a more pro-natalist policy and in the 1980s acted under the growing pressure of Solidarity movement. Despite official endorsement of family planning, the limited and erratic availability of contraception show this was not a government priority.Footnote 95 Therefore, Poland did not fulfil the 1970s and 1980s principles of the international planned parenthood movement, which with its ‘human rights model’ emphasised universal access to family planning advice and contraception.Footnote 96 Financial aid and subsidised contraceptives from the IPPF mitigated the Society’s crisis during the 1980s to a certain degree.Footnote 97 At the turn of the 1990s, however, as Kulczycki has stated, the Society was a ‘marginalised and almost bankrupt organisation’, the ‘low profile and ineffectiveness’ of which prompted the IPPF to switch affiliation to the newly established Federation for Women and Family Planning.Footnote 98 At the same time, since the mid-1970s and throughout the 1980s the Society was involved in sex education programmes introduced to public schools that became an alternative channel of spreading contraceptive advice. A systematic study of this effort is still awaiting research.

3 Catholic Preparation for Marriage in State-Socialist Poland

In this section, we discuss some early initiatives in family and ‘responsible parenthood’ counselling provided by Catholic doctors and other medical professionals during the late 1950s and early 1960s. We then analyse the ideas and strategies presented by the Catholic hierarchy intended to mainstream ‘Catholic preparation for marriage’ from the late 1960s onwards. We discuss local implementations of these ideas and strategies, paying particular attention to Cracow and Warsaw. Finally, we discuss ways in which Catholic family planning literature was in dialogue with Society experts.

Initiatives by the Polish Catholic Church’s hierarchy providing theoretical and practical support for Catholic spouses exercising their rights and obligations, in relation to what Vatican II had established as ‘responsible parenthood’,Footnote 99 started to blossom from the early to mid-1960s. This was when the Polish Episcopate and local curiae intensified their efforts towards the creation of specific institutions for the purpose and published instructions intended to mainstream Catholic preparation for marriage in Poland.

This explosion of activities, which we will discuss in more detail in what follows, was preceded from 1956 onwards by radical opposition of Catholic hierarchy towards the legalisation of abortion and campaigns popularising contraception: both identified as major threats to Catholic families and the entire community.Footnote 100 A number of priests, including Tadeusz Ryłke, whose writings from the late 1950s are held in the Chaplaincy of Families’ Section of the Archives of the Metropolitan Curia in Cracow, labelled the Society and its ‘neo-Malthusian’ campaign’ as ‘anti-Church’, the complete antithesis of Catholic values and a direct attack on Catholicism in Poland.Footnote 101 Others, such as Andrzej Bardecki, a long-term contributor to Tygodnik Powszechny [Catholic Weekly], the country’s foremost Catholic magazine, and one of the key disseminators of Vatican II ideology within Poland,Footnote 102 called for an urgent organisation of doctor-run Catholic Family Counselling services to counteract state birth control campaigning and help fight abortion. In Cracow during the late 1950s, Bardecki claimed that such a counselling service was being run successfully by a group of four doctors.Footnote 103 We have found no further record of this service in the DCF archives, however, which leads us to believe this must have been a short-term venture.

Other local initiatives around ‘responsible parenthood’ run by Catholic doctors in Polish cities during the late 1950s and early 1960s were also short-lived, such as one by the Catholic medical cooperative Ognisko [Bonfire], which established an interdisciplinary clinic in Warsaw during 1958 to deliver medical and psychological advice on ‘marital and sexual ethics in accordance with the Catholic Church’s teaching’. Amongst the medical professionals involved, historian Katarzyna Jarkiewicz has identified the female dentist Janina Cyranowa, who presided over the Polish Catholic Doctors’ Association, the feldsher (auxiliary health professional) and fertility awareness instructor Teresa Strzembosz, and gynaecologist Joanna Massalska, who openly opposed the 1956 liberalisation of abortion law.Footnote 104 The Catholic association PAX also opened similar clinics in smaller towns including Oświęcim, Giżycko and Iława.Footnote 105 All of these clinics were short-lived: the PAX ones closed their doors after a few months, and the Ognisko venture only lasted to 1963.Footnote 106 According to Jarkiewicz, the main reason for this was a lack of finances, while historian Natalia Jarska, argues Ognisko was shut down upon explicit instructions from the communist authorities, who considered it promoted the Church’s anti-abortion campaign.Footnote 107

In order to support anti-abortion medical professionals, the Episcopate established specific Chaplaincy of Healthcare in 1957.Footnote 108 Its aim, according to priest (later archbishop) Kazimierz Majdański, one of its principal organisers, was to inform and convince doctors and other healthcare professionals about the dangers of contraception and ‘about the fact that no circumstances can justify abortion and that, according to modern medicine, there were no “medical” grounds to kill a child’ (foetus: authors).Footnote 109 The Chaplaincy of Healthcare, according to Majdański, was also to provide counselling as well as gather scientific and pastoral literature on (or rather, against) contraception and raise fertility awareness. It is possible that this strategy had not proven sufficiently effective, prompting a shift towards – or prioritising of – another strategy, which focused on the dissemination of Catholic ‘regulation of conceptions’ through parishes and lay female counsellors, rather than clinics staffed by medical doctors.

This strategy became more explicit from mid- to late 1960s onwards, with specific institutions created to this aim, such as the Sub-Commission (later Commission) of the Polish Episcopate for the Chaplaincy of Families, created in 1965. The (Sub)Commission defined this strategy as a move from ‘intervention’ through Catholic healthcare providers towards mainstream ‘prevention’, by ‘popularising a family model that recognises its role in God’s plan’.Footnote 110 Catholic doctors, as well as nurses and midwives, continued to be targeted as experts that priests could refer their parishioners to for advanced training in fertility awareness. However, a number of Catholic commentators considered placing doctors at the centre of Catholic family planning as counterproductive, as they were too busy, not sufficiently trained in the realm of ‘natural’ family planning or discouraged ‘patients’ with excessively complex language. Such ideas were presented in the widely circulated brochure Co każdy ksiądz wiedzieć powinien o naturalnej regulacji poczęć [What Every Priest Should Know about the Natural Regulation of Conceptions] (probably first edited in the late 1950s, and re-edited at least four times) and were also formulated by the Catholic psychiatrist Wanda Półtawska, personal friend of Karol Wojtyła (later Pope John Paul II) and one of the main intellectual and medical authorities in the realm of Catholic preparation for marriage from the late 1950s onward.Footnote 111

In materials produced by the Catholic hierarchy throughout the period covered in this paper, periodic abstinence was presented as the only ethical method of birth control. Elicited by commercialisation of the oral contraceptive pill, publication of the encyclical Humanae Vitae in August 1968 – a watershed in the Catholic world, as it affirmed the rejection of ‘artificial’ contraception after almost a decade of deliberation, and was contested by hierarchies and theologians across the globeFootnote 112 – had little effect on the Polish hierarchy’s discourse on contraception. As priest Jerzy Buxakowski, head of the Chaplaincy of Healthcare (1966–77) and secretary of the Episcopal Commission on Chaplaincy of Families (nominated in 1966), noted, the Encyclical merely reaffirmed the Polish Church’s position, which struggled from a ‘lack of support by Western Churches’.Footnote 113 It was therefore no surprise that the Polish Episcopate unquestionably adhered to Humanae Vitae, which was utilised in the intensification of efforts to mainstream Catholic marriage and ‘family planning’ ethics in Poland during the late 1960s.Footnote 114

This intensification led the Polish Episcopate to release the ‘Instruction to Priests on the Preparation of the Laity for the Sacrament of Marriage and on Chaplaincy of Families’ in February 1969, which emphasised the need for Catholic education to focus on marriage preparation.Footnote 115 As the Instruction specified (and the second Instruction, published in 1975, reiterated),Footnote 116 this should cover long-term preparation for marriage, aimed at children and teenagers, as well as ‘immediate’ preparation for fiancées, for whom it became mandatory to attend marriage preparation courses.Footnote 117

After publication of the Instruction and during the 1970s in particular, local dioceses and lay Catholic intellectuals continued to elaborate scripts and programmes for ‘long-term’ and ‘immediate’ marriage preparation to guide and support priests and lay instructors.Footnote 118 This material showcases multi-disciplinary aspirations for such preparation, with a broad range of topics covered, including choosing a partner, ‘natural’ gender differences and their role in marriage, conflict management, and guidance for raising children. ‘Fertility regulation’ is extensively described for those engaged in ‘immediate’ marriage preparation, and is inscribed into ‘marital ethics’, intertwined with a strong anti-abortion and anti-contraception stance.

As well as multi-disciplinary, Catholic preparation for marriage was also conceived as multi-site and multi-level: it involved both the clergy and laity, and would be developed through different methodological tools, including age-specific talks, sermons, confessions, and individual and group consultations with lay counsellors. Priests and (female) lay instructors were to work in ‘collaborative symbiosis’.Footnote 119 In 1965 and 1971, the clergy received specific instructions on how to intervene in the laity’s family planning practices. Priests were reminded about their obligation to play a proactive role in helping penitents realise that artificial contraception and coitus interruptus were sins. These instructions were accompanied by a short text providing basic training in the ‘natural regulation of conception’,Footnote 120 but priests were encouraged to refer spouses to parochial instructors for specific training. Lay counsellors were to receive detailed training and hold regular – if often short – parish office hours,Footnote 121 as well as deliver talks on the ‘natural regulation of conceptions’ during pre-marital courses for fiancées.Footnote 122 In contrast to priests, their role was to cover the biological, rather than moral, aspects of Catholic family planning.Footnote 123

Actual implementation of these recommendations varied according to the local setting. In Cracow Archdiocese, Wojtyła’s influence and personal interests led to substantial investment in family counselling, making the city an important training centre with a dense network of instructors. Facilities operated regularly on various levels, including parishes, local Academic Ministries ([Duszpasterstwo Akademickie], henceforth AM) intended to support spirituality among university students,Footnote 124 and a specialised research and teaching centre, the Institute of Families.Footnote 125 Founded between 1967 and 1969 and directed by Półtawska, the Institute provided training and reference materials on topics relating to marriage, sexuality and fertility regulation for priests and secular instructors from across Poland. In 1975, it became affiliated to the Pontifical Academy of Theology.Footnote 126

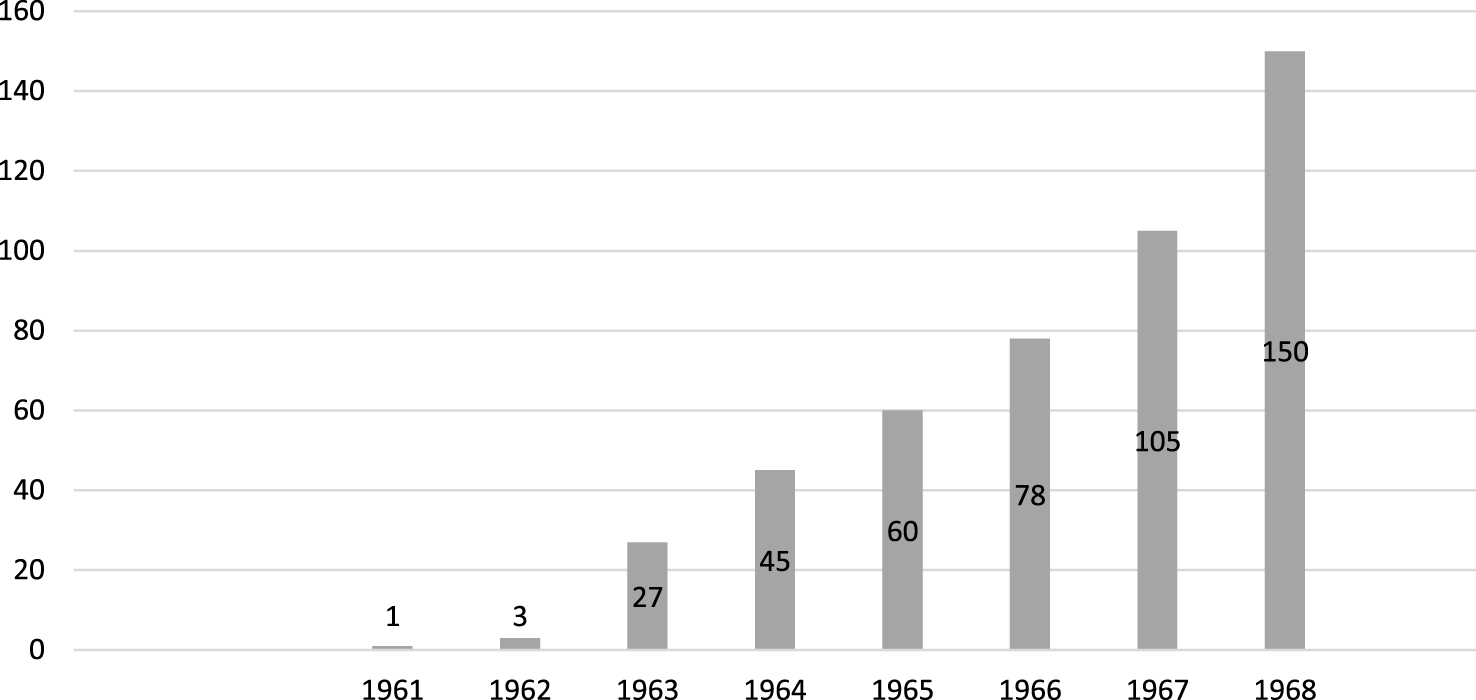

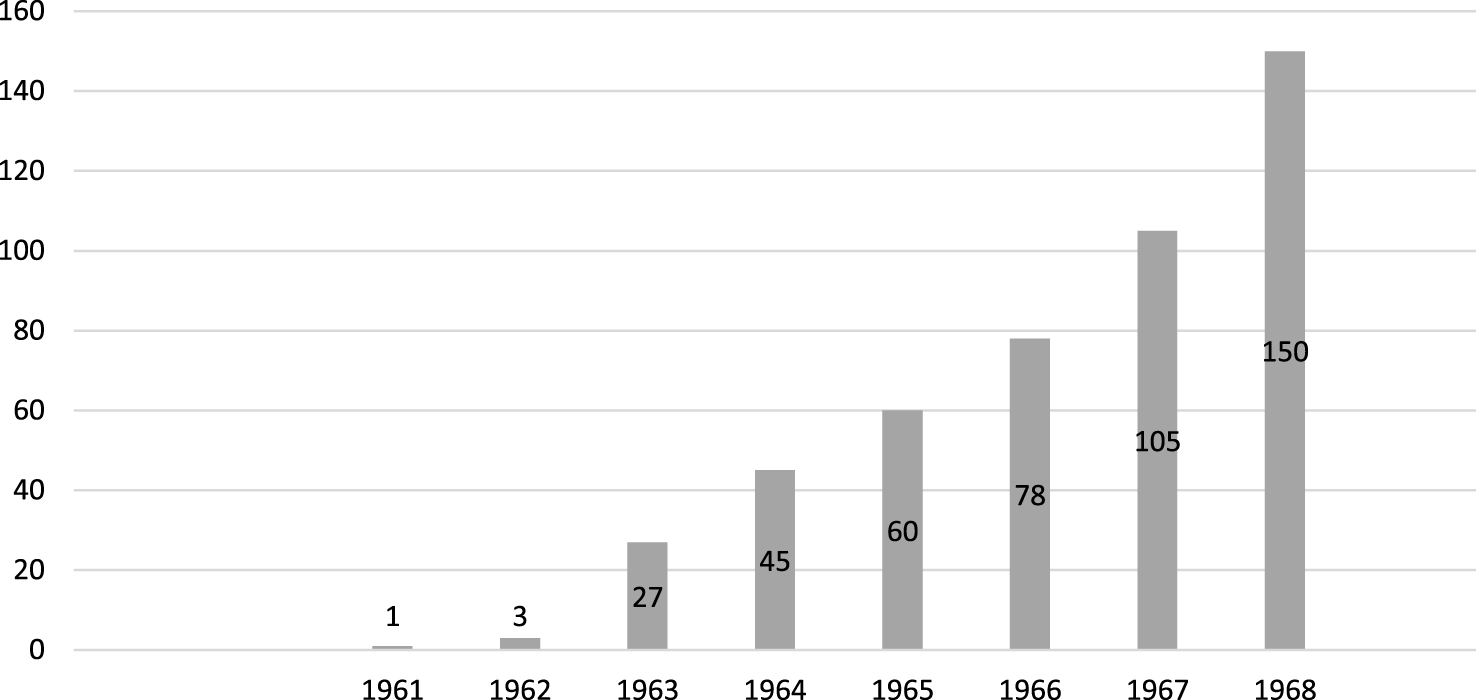

Establishing the Institute of Families was inscribed into a wider programme of investment in expanding the organisational structure of family counselling in Cracow Archdiocese during the second half of the 1960s. Wojtyła aspired to develop and mainstream what he considered the ‘Polish model of pastoral care of families’, based on wide accessibility to teaching, the ethical ‘regulation of conception’ and unconditional adherence to the Humanae Vitae.Footnote 127 The year the Encyclical was published, Wojtyła promoted the creation of a separate Department of the Chaplaincy of Families in the Archdiocese to design the framework for local marriage preparation courses for fiancées, which were to include three meetings with a priest and a mandatory consultation regarding ‘ethical conception control’.Footnote 128 These consultations were to be carried out by secular instructors of fertility awareness, selected by the aforementioned Teresa Strzembosz.Footnote 129 Another element of what historian Katarzyna Jarkiewicz termed the ‘crash campaign’ of Humanae Vitae-based teaching on marriage and procreation promoted by Wojtyła in CracowFootnote 130 was the expansion of counselling centres in the Archdiocese, with 150 Catholic counselling centres funded between 1961 and 1968, a process that accelerated after Wojtyła became head of the Archdiocese in 1963 (figure 3).Footnote 131

Figure 3: Catholic counselling centres in Cracow Archdiocese, 1961–68. Data from ‘Parafie w których rozpoczęto pracę…’, DCF – CMCA.

Although the number of parishes providing counselling in Cracow Archdiocese systematically expanded, the majority of ‘counselling centres’ were actually the weekly office hours of a local female counsellor trained by archdiocesan instructors in fertility awareness. Only a small number of parishes provided full-time consultancy and, according to the priest Władysław Gasidło, head of the Department of the Chaplaincy of Families of Cracow Metropolitan Curia in 1973 and its avid chronicler, many such centres had opened in 1968, as a response to Humanae Vitae, but were short-lived.Footnote 132 According to an internal report in the late 1960s in the DCF archive, the ‘fluctuation of the work in parishes’ was due to a number of reasons, such as the ‘impatience of some clergy’:

…which turns them against counselling, because they cannot see short-term results. Some female counsellors – even those deeply devoted to this work – get discouraged, too, because of lack of comprehension from priests, lack of understanding of the long-term nature of this work. They are sometimes bullied with mean comments.Footnote 133

This extract reveals tensions between priests and female counsellors that merit further exploration beyond the scope of this article.

In Warsaw Archdiocese, the executive order to the aforementioned 1969 Instruction on marriage preparation issued by the Polish Episcopate was published in May 1970 and included the decision to offer two-year marriage preparation schemes for all over eighteens. The meetings were to be held at least twice a month and followed a programme of forty lectures, fifteen specifically covering ‘preparation for marriage and Catholic (family) life’. Upon completion, participants would receive certificates excusing them from attending intensive pre-marital courses for fiancés, which the Archdiocese also continued to provide.Footnote 134

The AMs and other pastoral activities established by clergy in a number of parishes to reach university students and the broader academic community, played an important role in delivering these courses in Warsaw, as they did in Cracow, Lodz and other university cities. According to historian Milena Przybysz, the Lodz AM started marriage preparation seminars in 1972, and provided open discussion groups on Catholic ethics throughout the 1970s and 1980s, with abortion and euthanasia among the most popular topics.Footnote 135 Jarkiewicz reports that clergy involved in the Cracow AM established weekly pre-marital consultation sessions as early as 1962.Footnote 136 In Warsaw, the AM Church of Saint Anne hosted a regular seminar cycle, ‘Marriage Upon Us’. During the academic year 1972 to 1973, these seminars took place every Thursday after evening mass. Topics included ‘Partner Selection and Knowing Each Other’, ‘Correct Development of Sex Drive (Why Abstinence?)’ or ‘Marriage as a Source of New Life: The Problem of the Number of Children’.Footnote 137 Apart from these seminars for students and the academic community, Saint Anne’s Church also held meetings for fiancées, which included specific retreats (rekolekcje) for each of their target groups.Footnote 138

The title of the ‘Marriage Upon Us’ seminar cycle was certainly no coincidence given the strong influence of the Catholic intellectual Andrzej Wielowieyski in Warsaw’s Klub Inteligencji Katolickiej ([Catholic Intelligentsia Club] henceforth CIC) activities relating to Catholic marriage preparation. Wielowieyski was the author of Przed nami małżeństwo [Marriage Upon Us], a widely circulated advice book for preparation for Catholic marriage. The CIC, active in Warsaw and other Polish cities, was an organisation of Catholic intellectuals independent from the hierarchy and the communist authorities. Cradle to many key oppositionists to the communist regime, the CIC was also an important agent for dissemination in Poland of the ideas of Vatican II, including those on contraception.Footnote 139

Throughout the 1970s, different forms of marriage preparation were mainstreamed through Warsaw parishes. A 1978 brochure, Spotkania z narzeczonymi w punkcie poradnictwa rodzinnego [Meeting Fiancées in the Family Counselling Office], produced by the Department of the Chaplaincy of the Warsaw Metropolitan Curia for use by family counsellors, provides a flavour of local training for fiancées during the late 1970s. Although recommending counsellors be empathic and cordial, the authors insisted on fertility awareness training for all couples, including those already expecting: ‘It depends on us whether after the baby is born, these people will start to use contraception or regulate [their fertility] naturally.’ The brochure recommended holding three meetings with fiancées: the first discussing love and the transmission of life, in line with the encyclical Humanae Vitae, the second on ‘sexual culture’ (kultura życia seksualnego, a term popularised by Polish sexologists and Society experts from the late 1950s onwards, which bore direct relationship with Soviet notions of ‘sexual moral education’Footnote 140) and the third on ‘ethical and unethical means of controlling fertility’. The booklet advised counsellors to emphasise that using artificial contraception predisposed the couple to terminate any pregnancy (‘homicide’) if contraception failed. Among visual aids listed, the booklet mentions a set of photographs of a three-month-old foetus given the name ‘Jaś’, thereby constructing anti-abortion discourse on foetal personhood while also underlining the dangers to women’s health.Footnote 141

The booklet’s argument about abortion as both immoral and unhealthy was characteristic of Catholic family planning materials published in Poland from the 1950s onwards. Linking abortion to health problems and infertility was also a constant strategy in popular family planning literature produced by state-sponsored family planners.Footnote 142 In fact, Catholic literature aimed at secular believers as well as instructor training materials quite consistently – and instrumentally – used Society expertise. This occurred more frequently in relation to abortion than contraception, as the attitudes of Catholic and Society activists to the latter differed greatly. As mentioned earlier, Catholic family planning literature and materials portrayed all contraceptive methods, devices and techniques as dangerous weapons with which the ‘anti-church’ promoted immoral and unhealthy practices. Even so, compilers of material for the marital preparation courses occasionally and selectively referred to the Society when emphasising the negative side effects of contraceptive methods. For instance, a pamphlet on ‘Dangerous Oral Contraceptives’ quoted Problemy Rodziny [Family Issues], the professional family planning journal edited by the Society, as a source of information to support their claims against the pill.Footnote 143 However, this reference did not originate from one of the research articles, in which the pill was generally described as a safe method when used under medical supervision,Footnote 144 but from the ‘News from Abroad’ section, where some heated international debates on the safety of the recently released drug had been described.

Catholic family planning literature and marriage preparation materials also referred to renowned gynaecologists and family planning activists linked with the Society who described the rhythm method favourably. The aforementioned gynaecologist Jan Lesiński was amongst the most frequently quoted in the Cracow Chaplaincy of Families material, especially during the 1960s.Footnote 145 In Wojtyła’s 1960 Miłość i odpowiedzialność [Love and Responsibility],Footnote 146 one of the key texts for Catholic marriage preparation, the future Pope recognised the Society doctor’s expertise by recommending the chapter on ‘Periodic Sexual Abstinence’ in Lesiński’s Zarys zapobiegania ciąży dla lekarzy i studentów medycyny [Introduction to Birth Control for Doctors and Medical Students] (1959)Footnote 147 in his bibliography on sexology. This recognition could, however, be due to the limited availability of Polish literature on the rhythm method at that time.

Another key manual for Catholic marriage preparation, Katolik a planowanie rodziny [A Catholic and Family Planning] (published in 1964 and re-edited four times before 1984), the authors of which were linked to the progressive Catholic magazine Więź [Bond], edited by the CIC, also quoted Lesiński’s Introduction to Birth Control to discuss the alleged dangers of abortion. A collection of scripts for the delivery of marriage preparation seminars for fiancées, prepared by the Cracow Chaplaincy of Families in 1975, extensively quoted the female doctor and Society activist Barbara Trębicka-Kwiatkowska’s pamphlet with the suggestive title Zapobieganie czy przerywanie ciąży [To Terminate or to Prevent Pregnancy],Footnote 148 dedicated specifically to possible complications resulting from abortions.Footnote 149 Ewa Czerwińska, author of the script, summarised (or exaggeratedly paraphrased) the gynaecologist, simplifying her argument to ‘It is practically impossible for abortion not to cause damage’,Footnote 150 an assertion Trębicka-Kwiakowska had not in fact made.Footnote 151

During the 1970s and 1980s, CIC marriage preparation materials often quoted – and at times literally reproduced – publications by experts linked to the Society, including those by long-term president Mikołaj Kozakiwicz in reference to preparation for parenthood.Footnote 152 The already mentioned influential Catholic manual Marriage Upon Us by Wielowieyski dialogued with the works of sexologist Kazimierz Imieliński and with Kozakiewicz, whose two books on sex education were also included in the reference list of the aforementioned marriage manual, A Catholic and Family Planning.Footnote 153

This selective cross-referencing showcases two concurrent and seemingly mutually exclusive trends in Catholic marriage preparation materials. One was the push against ‘birth control’ language, which was mainstreamed in public discourse and propaganda when contraception became a public health project in state-socialist Poland after 1956. The Chaplaincy of Families in Cracow compiled – and most probably also disseminated – numerous brochures and scripts from the late 1950s onwards calling on people to reject the Society in defence of the ‘conceived children’, murdered in the wombs of (and by) their mothers.Footnote 154

The large printed manuals of Catholic marital ethics, however, such as Love and Responsibility, A Catholic and Family Planning and Marriage Upon Us, took a different strategy. Rather than definitively reject mainstream terms such as ‘family planning’, these manuals consciously embedded them in elaborate discourses, furnishing the terms with new meanings more aligned with the principles of Humanae Vitae. In Love and Responsibility, for instance, Wojtyła underlined that self-control was the key to ‘conscious motherhood’, which he defined as ‘the attempt to adequately grasp the relationship between marital cohabitation and the possibility of conception’, and must be accompanied by an ‘honest parental attitude’, meaning an overall willingness to become a parent.Footnote 155 With ‘conscious motherhood’ defined in this way, Wojtyła claimed periodic abstinence was the only technique that fulfilled its requirements.Footnote 156

A Catholic and Family Planning represented a more progressive stream of Catholic laity: the title reflected an attempt to re-signify ‘family planning’ and ‘conscious motherhood’ in Catholic terms. ‘Conscious motherhood’, according to the authors, meant ‘engaging consciousness and responsibility to fulfil the basic task a family has, which is bringing children to the world’.Footnote 157 The authors emphasised similarities between secular and Catholic ideas, claiming the Church accepted family planning if ‘reasonable’ but not if it meant an ‘egoistic rejection of children whatsoever’. The divergence in ideology lay in the Church’s rejection of ‘artificial’ contraceptive methods and abortion. According to the authors of this book, secular family planning considered abortion a ‘necessary evil’; for the Church it was an ‘unacceptable evil’.Footnote 158 Similar ideas were put forward in Wielowieyski’s Marriage Upon Us, first published in 1972, and re-edited in 1977 and 1988.

Marriage Upon Us, however, as anthropologist Agnieszka Kościańska has argued, was exceptional in its overt criticism of Humanae Vitae. Wielowieyski wrote about periodic abstinence as a method that strengthened mutual comprehension between spouses through discipline and sacrifice and did not interfere with the natural balance of the human body. However, he was also explicit about its drawbacks and compassionate towards couples who faced difficulties practising it and opted in favour of other contraceptive methods or techniques. He was also unique in explicitly mentioning condoms (first edition, 1971) and later barrier methods in general (second edition, 1974) as ‘artificial’ methods which could perhaps be considered a ‘lesser evil’.Footnote 159 As Kościańska noted, the 1974 edition of Marriage Upon Us was slightly modified: the result of direct intervention by Wojtyła, who criticised the book for not sufficiently adhering to the spirit of Humanae Vitae. Footnote 160

4 Conclusions

From 1956 onwards, the delivery of family planning advice became a priority for both the Polish Catholic Church and the party-state, especially its health authorities, which supported the foundation of the Society of Conscious Motherhood and aspired to mainstream birth control advice through the network of public well-woman clinics. As a consequence, two systems of family planning counselling emerged: the professional, family planning movement and Catholic pre-marital and marital counselling. These systems had different relationships with the party-state. Family planning activists and professionals aligned with the Society enjoyed state support, at least theoretically, while Catholic family planning counselling was carried out as a counteraction, especially during the late 1950s and 1960s. However, a shift in state population policies, initiated in the mid-1970s, triggered the mainstreaming of Catholic family planning principles in Poland. At this time, attempts by health authorities to channel family planning through the public healthcare system had been largely unsuccessful and the Society was obliged to play a greater role in family planning advice. However, without sufficient, systematic and on-going state support as well as investment in improving contraceptive provision, the Society was unable to fully develop their family planning services.

These two seemingly mutually exclusive systems of family planning advice openly clashed, especially during the late 1950s and 1960, but also communicated with each other, with documented mutual recognition of authority: medical knowledge was recognised by the Church, moral expertise by the Society. From the turn of the 1950s onwards, Catholic marriage preparation manuals and scripts cited the works of key Society activists such as Lesiński, Beaupre and Wisłocka, a number of whom also referred to Catholic ethics in their writings and consistently covered – but rarely recommend – the rhythm method. It must be emphasised, however, that this mutual recognition of authority was, in our view, subordinated to particular ideological goals, especially in the case of Catholic authors, who quoted Society-affiliated doctors on the negative health effects of abortion and contraception, but ignored those writings where doctors emphasised the safety and security of contraceptive methods.

Cycle-observation based family planning was the key locus of connection between the two systems. Fertility awareness and (periodic) abstinence lay at the very basis of the Catholic family planning. Health professionals and activists involved with the Society, on the other hand, considered fertility-observation-based contraception unreliable. Their position changed during the 1980s, when some of the Society’s clinics started to train clients in fertility awareness techniques such as the Billings ovulation method. This shift reflects not only the increasing standing of the Church, and its alignment with the party-state vision of marriage, family and fertility, but also the rocketing economic crisis, which deepened shortages in all consumer goods, including contraceptives. Teaching fertility awareness, which did not require any product or device, perhaps proved the most practical family planning system in this complicated context.

The history of birth control in state-socialist Poland also provides ample ground for studying transnational movements for planned parenthood beyond the limiting ‘First’–‘Third’ world paradigms. In state-socialist Poland, both state-sponsored and Catholic family planning systems gained legitimisation from transnational links. The Society’s connections with the British FPA and the IPPF were certainly a somewhat unexpected source of this legitimisation. Their support, in terms of expertise and international, but also local, visibility, proved essential during the Society’s infancy, and during its decline in the 1980s. For Catholic family planning in Poland – at least the version promoted by the national hierarchy and adhering ideologists – legitimisation was based on positioning itself starkly against trends in transnational Catholic debates during the 1960s on liberalisation of the contraception ban. Years before the encyclical Humanae Vitae was published, the hierarchy prided itself on proposing a vision of marriage, fertility and contraception – and family (planning) – that later materialised in this document. Following its publication, the hierarchy used the encyclical as the ideological basis for an entire marriage preparation system during the 1970s and 1980s, intended to permeate throughout Polish society. At this point in our research we can only speculate about its actual impact. With regard to transnationalism – and as a recommendation for further research – there is evident need to explore the Catholic family planning movement’s transnational relations and cooperation beyond Humanae Vitae, a milestone which has received by far the most academic attention. Such a transnational perspective, we believe, will be particularly fruitful in further charting the almost virgin terrain of the history of Catholic family planning in Poland.