Introduction

Human life is deeply rooted in narratives. We engage in discussion, sharing our experiences and those of others to nurture meaningful connections with peers, comprehend the world, and construct our sense of self (Cherry, Reference Cherry1966; Fisher, Reference Fisher1985; May, Reference May2004). In today’s ultra-connected world, the need to share personal and emotional experiences is particularly present. Testimonies often recount past events that resonate with present concerns grounded in one’s cultural background, history, and collective memory (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Hogg and Turner, Reference Hogg and Turner1987; Liu and Hilton, Reference Liu and Hilton2005; Dresler-Hawke and Liu, Reference Dresler-Hawke and Liu2006; Klein et al., Reference Klein, Licata, Van Der Linden, Mercy and Luminet2012; Bouchat et al., Reference Bouchat, Klein and Rosoux2016; Hogg, Reference Hogg, McKeown, Haji and Ferguson2016; Hirst et al., Reference Hirst, Yamashiro and Coman2018; Van Bergen et al., Reference Van Bergen, Evans, Harris, Branagh, Macabulos and Barnier2024). Featured in the media, museums, and exhibitions, they create deeply personal connections between narrator and audience, as well as to history (Bouchat et al., Reference Bouchat, Klein and Rosoux2016; Van Bergen et al., Reference Van Bergen, Evans, Harris, Branagh, Macabulos and Barnier2024). Amidst this rich landscape of narratives, encountered testimonies either echo or diverge from collective memories. How do we navigate these narratives and discern their impact on our attitudes, particularly when they revolve around controversial episodes? This question sparked our reflection on the power of personal, emotional narratives within collective memory in modern media (i.e., the digital and interactive forms of communication that have evolved with advancements in technology, including text, audio, and audiovisual formats on social media).

The power of narratives

The way humans communicate through oral and written language, stepping outside the ‘here and now’, enables us to refer to the past and learn from prior experiences. This competence gives rise to Homo narrans, the storytelling human. Recognising the power of stories, Fisher (Reference Fisher1985) designed the narrative paradigm to highlight the influence that can be derived from narratives and memories. People integrate others’ attitudes and experiences to organise the environment and mobilise relevant information to guide behaviour. Attitudes are evaluations towards people, objects, actions, or ideas that are held in memory (Bouchat et al., Reference Bouchat, Klein and Rosoux2016; Yzerbyt and Klein, Reference Yzerbyt and Klein2019). In essence, Fisher’s narrative paradigm frames human communication as fundamentally story-based, with narratives serving as the primary means through which we make sense of our world and experiences.

A narrative is a representation of connected events and characters with a particular sequence, related from a particular perspective and containing implicit or explicit messages about a theme (May, Reference May2004; Volkman and Parrott, Reference Volkman and Parrott2012). Narratives shape attitudes by fostering reliability and enhancing the experience-taking processes (ie, transportation and character identification; Fisher, Reference Fisher1985; Hirst et al., Reference Hirst, Yamashiro and Coman2018; Shaffer et al., Reference Shaffer, Focella, Hathaway, Scherer and Zikmund-Fisher2018). Transportation is a mental process in which the audience is temporarily immersed in a narrative world, losing access to the real one. Research has found that the more a person is transported into the storied world, the more their attitudes are influenced towards story-consistent beliefs (Green and Brock, Reference Green and Brock2000; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee and Baezconde-Garbanati2013; Hoeken and Sinkeldam, Reference Hoeken and Sinkeldam2014). Character identification occurs when individuals feel compassion and imagine themselves as the narrative’s character, adopting their goals and feeling their emotions (Tal-Or and Cohen, Reference Tal-Or and Cohen2010).

When immersed in a narrative, the audience perceives no motivation to elaborate on their own knowledge, thoughts, or to look critically at the narrative. Instead, they rely on heuristics, such as emotions, to align their attitudes with those depicted in the narrative (Petty and Cacioppo, Reference Petty and Cacioppo1986; de Graaf et al., Reference de Graaf, Hoeken, Sanders and Beentjes2009; van Kleef et al., Reference van Kleef, Van Doorn, Heerdink and Koning2011; Volkman and Parrott, Reference Volkman and Parrott2012; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee and Baezconde-Garbanati2013; Hoeken and Sinkeldam, Reference Hoeken and Sinkeldam2014; van Kleef and Côté, Reference van Kleef and Côté2022).

In our media-rich environment, testimonies tend to go viral through the sharing of emotional experiences, which are more likely to be shared, repeated, and elaborated upon in everyday conversations (Rimé, Reference Rimé, Russell, Fernández-Dols, Manstead and Wellenkamp1995; Richardson and Schankweiler, Reference Richardson and Schankweiler2020). Emotions are adaptive signals indicating one’s interests and needs (Frijda, Reference Frijda2001; Damasio, Reference Damasio2011; Luminet and Cordonnier, Reference Luminet, Cordonnier, Bietti and Pogačar2024). Consequently, emotional narratives direct attention to individuals’ own emotional reactions and bias cognitive responses, working as powerful sources of social influence (van Kleef et al., Reference van Kleef, Van Doorn, Heerdink and Koning2011; Volkman and Parrott, Reference Volkman and Parrott2012). In that line, emotional narratives are more likely to provoke stronger and more persistent changes in attitude than historical facts (Hirst et al., Reference Hirst, Yamashiro and Coman2018). Morris et al. (Reference Morris, Chrysochou, Christensen, Orquin, Barraza, Zak and Mitkidis2019) demonstrated that narratives, especially those with negatively valenced endings, have a greater impact on pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours than factual accounts due to heightened emotional arousal: the higher the emotional arousal, the more attention and encoding of information into working memory is increased, thereby enhancing pro-environmental responses (Shaffer et al., Reference Shaffer, Focella, Hathaway, Scherer and Zikmund-Fisher2018; Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Chan, Heintzelman, Tay, Diener and Scotney2020). Even though this study relied on pro-environmental stories, we expect personal and emotional narratives about family memories to be susceptible to the same influences. However, very few models on narrative persuasion have integrated emotional dimensions, such as valence or discrete emotions, as independent components (Dillard and Peck, Reference Dillard and Peck2001; van Kleef et al., Reference van Kleef, Van Doorn, Heerdink and Koning2011; Shaffer et al., Reference Shaffer, Focella, Hathaway, Scherer and Zikmund-Fisher2018; Luminet, Reference Luminet2022). Discrete or specific emotions reflect unique person–environment relationships, favouring particular appraisal patterns, thereby acting differently on attitudes (Villalobos and Sirin, Reference Villalobos and Sirin2017).

The present study

Through Fisher’s narrative paradigm, it is clear that emotionally charged personal stories wield significant persuasion power. However, further research is needed to understand their influence on attitudes and the underlying mechanisms. The difficult topic of collaboration during WWII offers an opportunity to explore how the emotional framing of personal narratives can influence attitudes regarding a controversial past (Bouchat et al., Reference Bouchat, Klein and Rosoux2016, Reference Bouchat, Luminet, Rosoux, Aerts, Cordonnier, Résibois and Rimé2021). In Belgium, during the German occupation (1940–1944), pro-Nazi and anti-communist parties – the Flemish National Union (Vlaams Nationaal Verbond) in Flanders and the Rexist party in Wallonia – formed military legions, that fought on the Eastern Front alongside the Wehrmacht. After the war, collaborators who worked with the German occupying forces were persecuted on the streets (popular repression), in private sectors, and by the state (military courts). In contrast to other countries, amnesty – a political measure that pardons and erases committed actions and offences – has not been granted to former collaborators (Aerts et al. Reference Aerts, Luyten, Willems, Drossens and Lagrou2017; Reference CegeSomaCegeSoma n.d.). This underscores that the history of collaboration remains a highly polarised and complex topic in Belgium. Furthermore, since the 1990s, representations of this past have increasingly linked collaboration to the Holocaust, while paying less attention to other forms of collaboration, such as military collaboration against communism on the Eastern Front (Ballière, Reference Ballière2024). This makes it a particularly relevant test case for examining the influence of personal narratives and bringing nuance to a topic that still divides Belgian public opinion today.

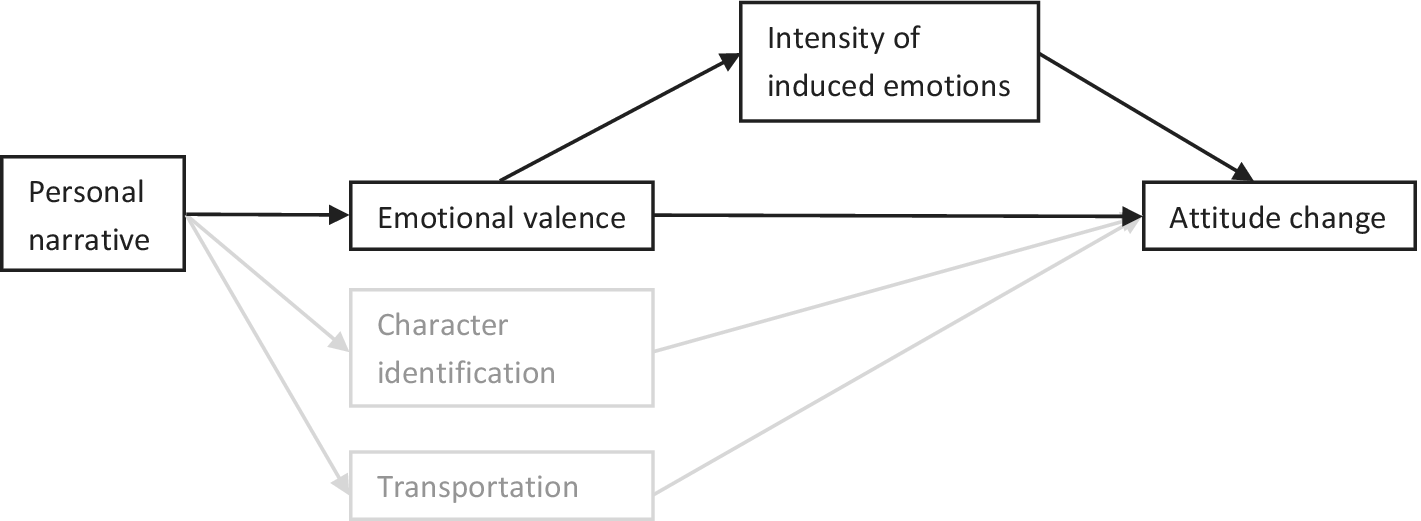

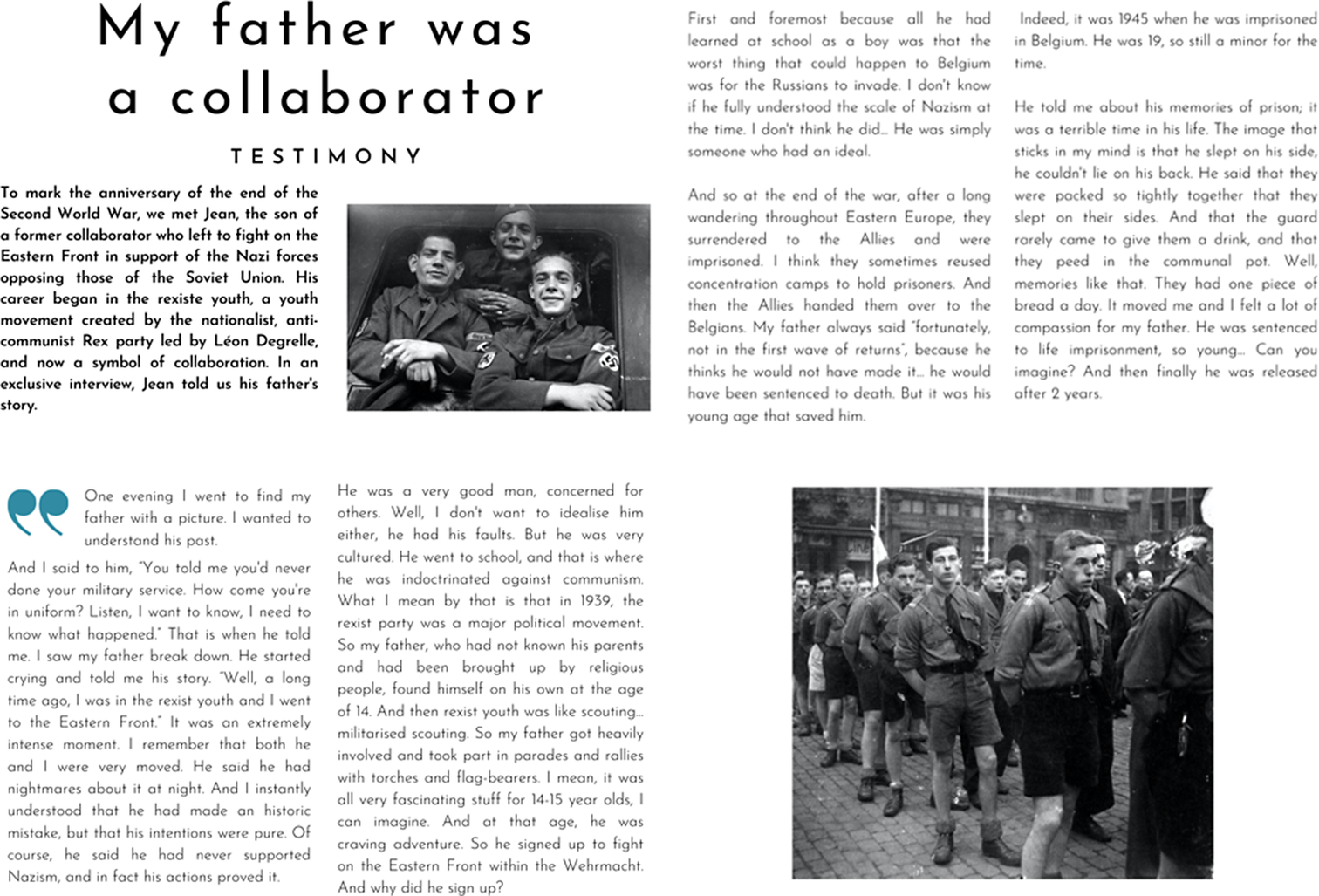

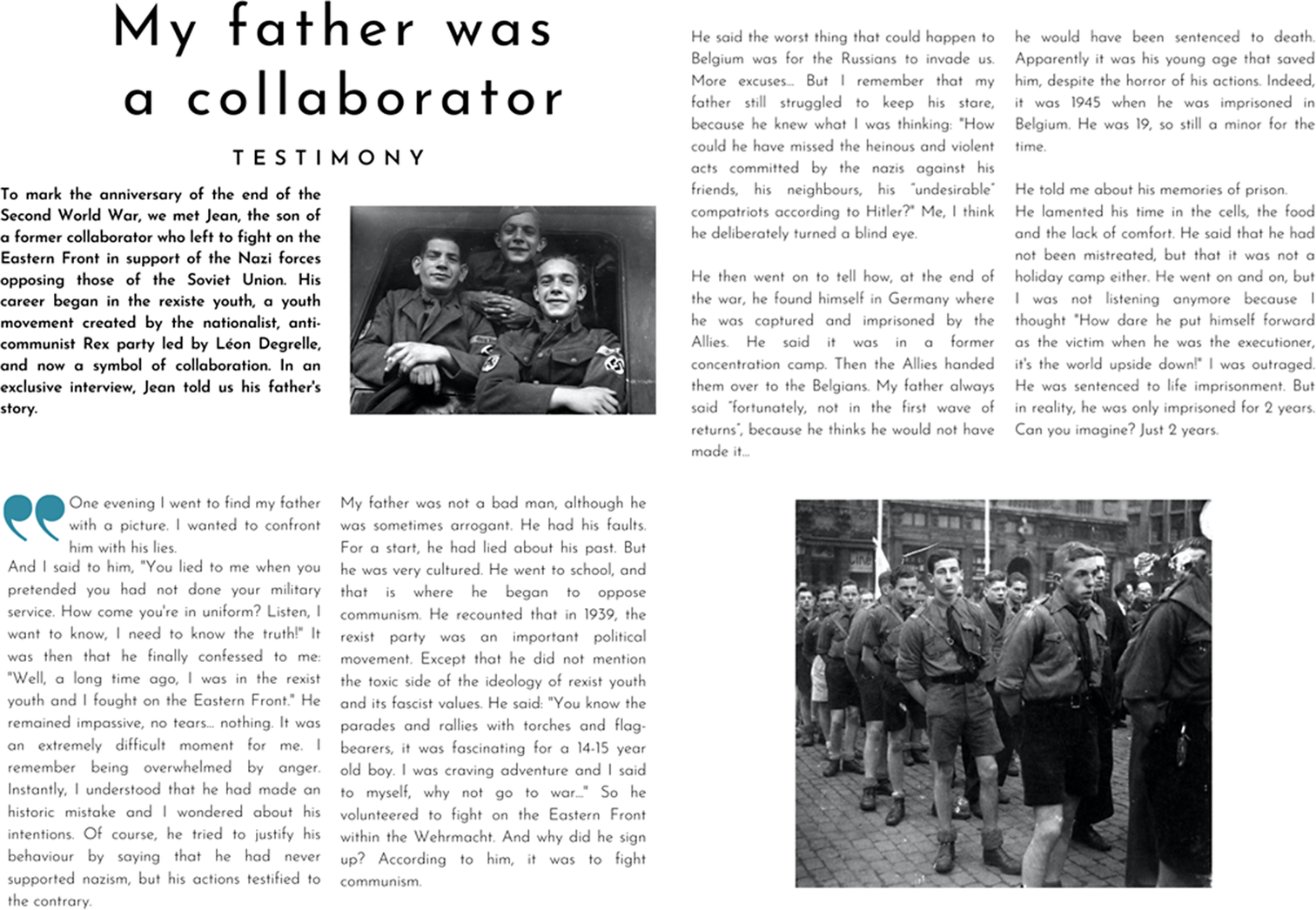

This study aims to investigate whether the emotional frame (positively valenced vs negatively valenced) of a personal narrative about a Belgian Eastern Front volunteer during WWII affects audience attitudes concerning collaboration and its repression (i.e., legal and social repression of collaborators after the war), mediated by induced emotions (Figure 1). The ecologically valid narrative, derived from authentic interviews with family members of former collaborators, features a magazine interview with the son of a former collaborator testifying about his father’s past as an Eastern Front Volunteer, accompanied by two wartime photographs. We created two versions of the interview, portraying either positive or negative feelings about the father’s past (Figures 2 and 3, respectively).

Figure 1. A hypothetical model for the influence of personal narratives on the audience’s attitude change.

Figure 2. Positively valenced interview translated for the purpose of this article.

Figure 3. Negatively valenced interview translated for the purpose of this article.

We formulate the following hypotheses. First, the emotional valence of the personal narrative will influence the direction of attitude change. The positively valenced account will lead to a more supportive attitude towards collaboration and to less understanding attitudes towards repression, while the negatively valenced account will produce the opposite effect (H1). Second, the influence of the narrative’s emotional valence on attitude change is mediated by the intensity of specific emotions induced in the audience (H2). While specific induced emotions are expected to influence the direction of attitude change, which emotions and their required intensity remain debated due to the variability in emotional responses. As such, this hypothesis is exploratory.

Methods

Participants

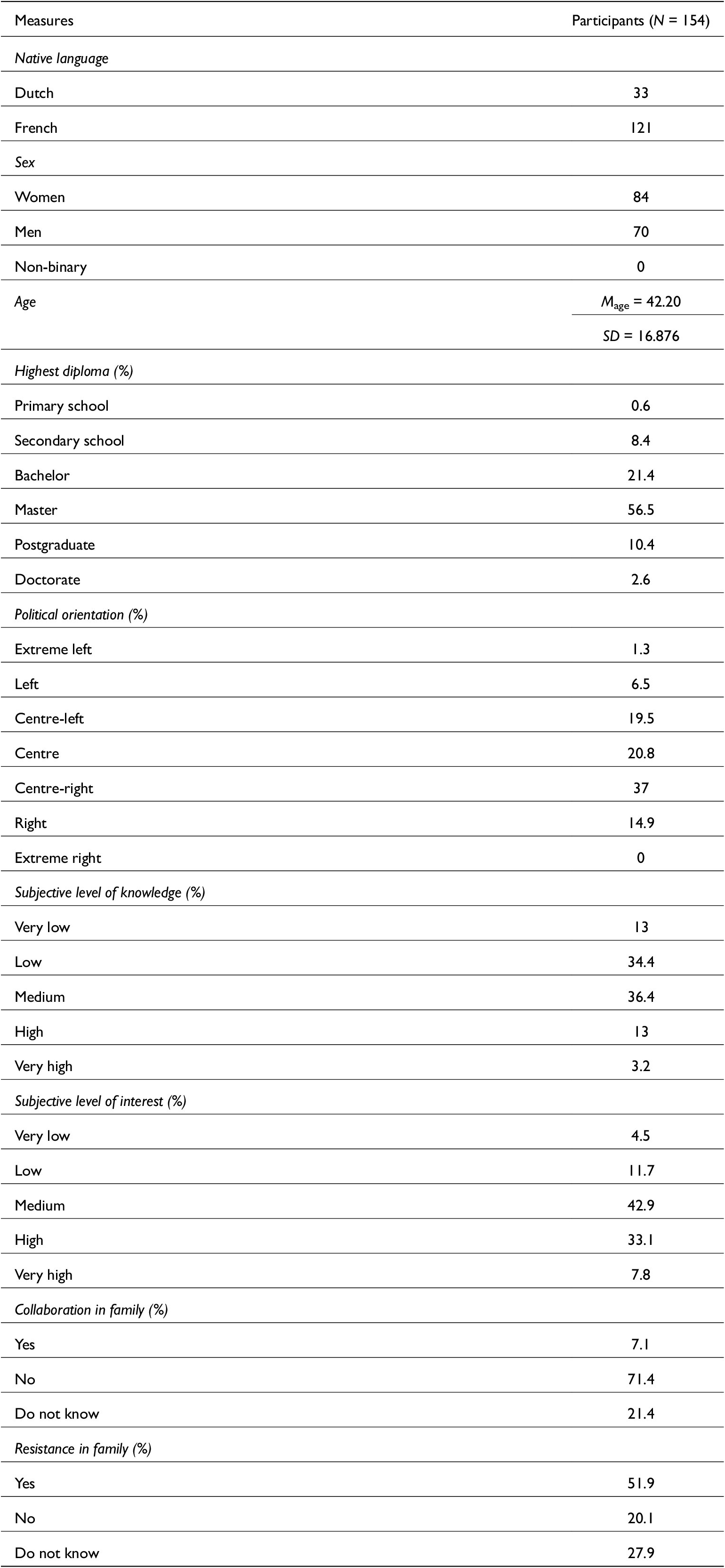

To measure changes in attitudes, our study relied on two online questionnaires on Qualtrics available in Dutch or French, presented at least 7 days apart (M = 8.19; SD = 2.60). Of the 335 participants who completed the first questionnaire, 161 proceeded to complete the second questionnaire. One participant’s answer sheet could not be paired due to mismatched codes. Six participants were discarded as they were non-Belgians, which did not meet the inclusion criteria: holding Belgian citizenship. The final sample consisted of 121 French-speaking and 33 Dutch-speaking Belgian adult participants (84 women and 70 men, M age = 42.20, SDage = 16.88). In Belgium, the two main linguistic communities (Dutch- and French-speaking) present distinct contexts. However, as baseline attitudes showed no significant differences between the groups, the data were analysed as a single sample. Table 1 provides an overview of the participants’ main characteristics. Recruitment occurred via social media and email, between June 25 and July 17, 2023.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics on the sample

Procedure

A first questionnaire gathered demographic information and baseline attitudes towards WWII collaboration and subsequent repression. Seven days later, participants received an email inviting them to answer the second questionnaire, with a reminder sent 3 days later to non-respondents. The second questionnaire included an interview framed by two wartime photographs from archival sources (CegeSoma 1942) to maximise ecological validity and emphasise real-world relevance. Participants were randomly assigned to either the positively or negatively valenced condition. Questions regarding transportation, identification, emotions, and attitudes followed.

To guarantee anonymity, participants created a personal code linking both questionnaires. Participation was voluntary, with signed informed consent. Two respondents were each awarded a €100 voucher. The study’s procedure and questionnaires were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Commission of the Institute for Research in Psychological Sciences (UCLouvain).

Materials

This section outlines the measures used in both questionnaires in order of appearance. Unless specified, items were assessed on 5-point scales from 1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree).

Questionnaire 1

The first section is Demographics: gender, age, educational level, political orientation, family involvement in WWII collaboration or resistance, subjective knowledge and interest in WWII collaboration, and repression. The measure Attitudes regarding WWII collaboration and subsequent repression includes nine items inspired by Bouchat et al.’s research (2021). Four items refer to attitudes towards former collaborators, covering responsibility, victimisation, morality, and necessity (e.g., ‘I have the impression that during WWII and the repression that followed, collaborators particularly suffered’). Another four items address attitudes towards repression, including victimisation, morality, and necessity (e.g., ‘I think that under certain circumstances the repression of collaborators was too severe’). The final item, ‘Today, Belgians are still suffering from what happened during WWII and the events that followed’, captures the attitude towards the ongoing impact of the past on the present.

Questionnaire 2

Transportation measures participants’ subjective experience and comprises five items, based on Cordonnier et al. (Reference Cordonnier, Barnier and Sutton2018); e.g., ‘When I was reading the text, I was totally absorbed in the story’. Character identification includes seven items adapted from de Graaf et al. (Reference de Graaf, Hoeken, Sanders and Beentjes2009), assessing identification with the character who collaborated (the father) and the narrator (the son). For example, ‘As I read the text, I imagined myself in the shoes of the father/ the son who collaborated’. Induced emotions. We first assess the overall emotional intensity (from 0: no intensity to 4: very high intensity), then the overall (un)pleasantness felt when reading the interview (from 1: very unpleasant to 5: very pleasant). Consequently, in line with the discrete-emotion approach, participants indicate the level of intensity (from 0: not felt to 4: felt very intensely) on a list of emotions they might have felt while reading: happiness, sadness, shame, pride, anger, guilt, disdain, gratitude, feeling of injustice, feeling of abandonment, disgust, fear and compassion. These emotions were selected based on their relevance to the topic of collaboration and repression. Moreover, emotions are measured twice to distinguish between emotions experienced at the individual and then at the collective level. Level of identification with Belgium contains seven items, inspired by Bouchat et al. (Reference Bouchat, Luminet, Rosoux, Aerts, Cordonnier, Résibois and Rimé2021), measuring participants’ pride and attachment to Belgium.

Interviews

A key element was prioritising narratives with high ecological validity. We integrated second-hand testimonies of five children of former collaborators collected by the last author in a previous project - the TRANSMEMO project that examined the intergenerational transmission of memories linked to the Second World War in the families of collaborators and members of the resistance. We represented them as faithfully as possible to preserve authenticity, better capturing the historical context and enhancing real-world relevance. We developed a positively valenced and a negatively valenced version of the interview, nearly identical in sentence structure and word count but with intentional differences in emotional tone (Figures 2 and 3). The interviews were translated into Dutch by one of the researchers and subsequently reviewed by two native Dutch-speakers. We conducted a pre-test (N = 11) to evaluate the similarity between the different conditions (positive vs negative and Dutch vs French translation) and found comparable levels of character identification, transportation, and emotional intensity.

Results

Preliminary results

Table 2 displays correlations between attitudes regarding collaboration and repression at pre- and post-test and participants’ characteristics. Age, subjective level of knowledge, level of identification with Belgium, and family involvement in the resistance significantly vary with attitudes at pre- and post-test. In particular, older participants held less favourable views on collaboration and saw repression as more justified and moral. This aligns with prior research linking attitudes to generational belonging (Bouchat et al., Reference Bouchat, Luminet, Rosoux, Aerts, Cordonnier, Résibois and Rimé2021).

Table 2. Spearman’s correlations between attitudes (towards collaboration and repression) and sample characteristics

Note: Spearman’s correlations were used as the variables are ordinal in nature, except for age. PRE-Attitude = global attitude at pre-test; PRE-Attitude-collaboration = attitude towards collaboration at pre-test (1 = negative; 5 = positive); PRE-Attitude-repression = attitude towards repression at pre-test (1 = positive; 5 = negative); POST-Attitude = global attitude at post-test; POST-Attitude-collaboration = attitude towards collaboration at post-test; POST-Attitude-repression = attitude towards repression at post-test (1 = positive; 5 = negative); Native language (−1 = Dutch; 1 = French); Sex (1 = Woman; 2 = Man); Highest diploma (1 = primary education; 5 = doctorate); political orientation (1 = extreme left; 5 = extreme right); Level of subjective knowledge and interest (1 = very low; 5 = very high); Level of identification with Belgium (1 = very low; 5 = very high); Collaboration in family (1 = yes; 2 = no/do not know); Resistance in family (1 = yes; 2 = no/do not know); **p < 0.01 (two-tailed); *p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

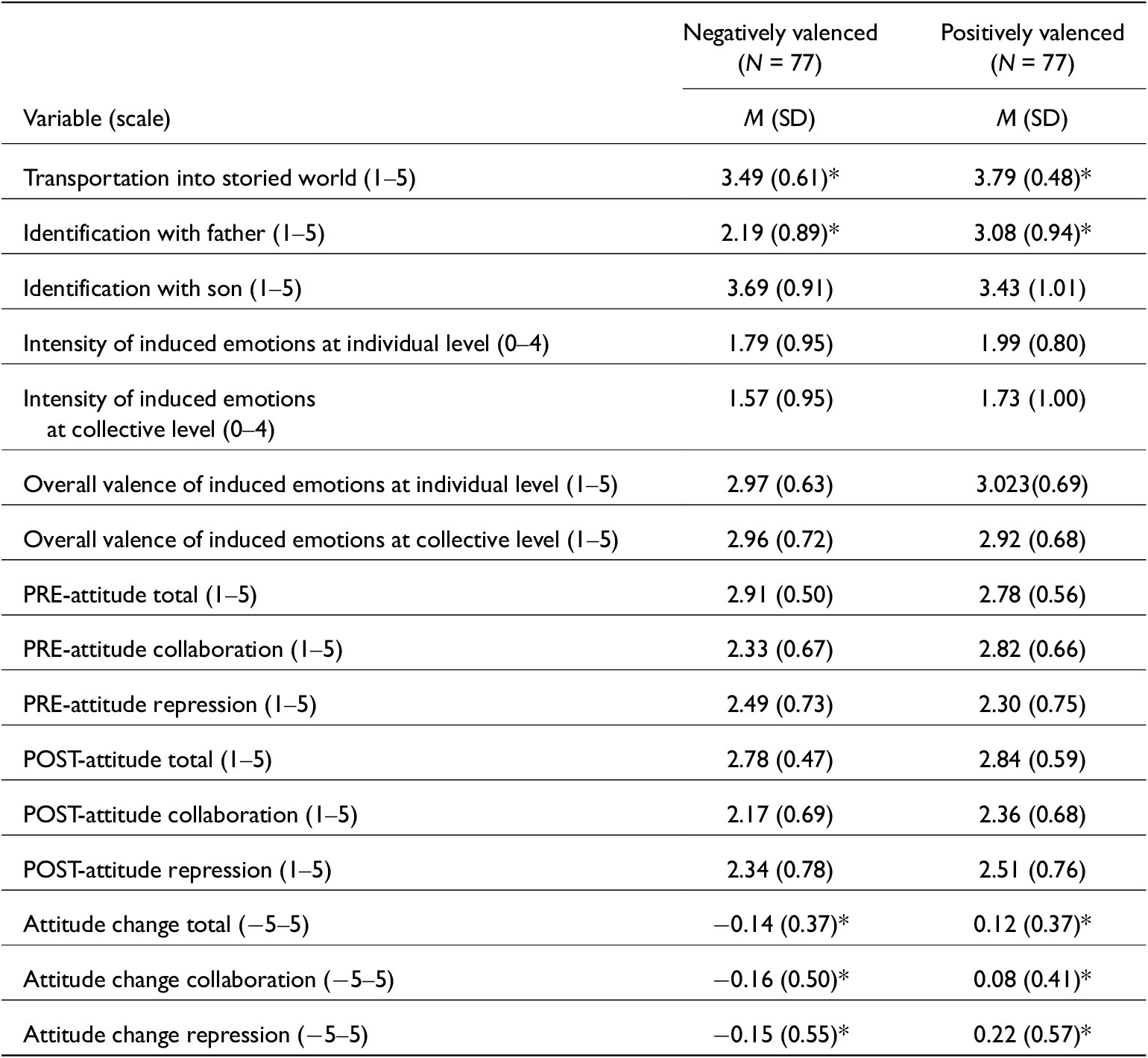

Table 3 presents descriptive measures of the variables in relation to the narrative’s emotional valence. Participants identified less with the collaborationist father (M = 2.64, SD = 1.01) than with the son who narrates the story (M = 3.56, SD = 0.97; Table 3). As the correlation between both variables is not significant (rs = 0.098, p = .229), we will examine them separately: ‘Character identification father’ and ‘Character identification son’. Regarding the overall intensity of induced emotions, the reported intensity was generally low.

Table 3. Descriptive measures on the variables in relation to the emotional valence of the narrative

Note: Negative and positive = emotional valence of the interview; PRE-attitude = global attitude at pre-test; PRE-attitude-collaboration = attitude towards collaboration at pre-test; PRE-attitude-repression = attitude towards repression at pre-test; POST-attitude = global attitude at post-test; POST-attitude-collaboration = attitude towards collaboration at post-test; POST-attitude-repression = attitude towards repression at post-test; Scales from 1 to 5, except for induced emotions (0: no intensity to 4: very strong intensity) and overall valence of induced emotions (1: very unpleasant, 3: medium, 5: very pleasant); N = sample size; M = mean; SD = standard deviation. Means in the same row marked with * differ at p < .05 by the Bonferroni method.

The influence of the emotional valence on attitude change

We conducted a linear regression to test whether the emotional valence of a personal narrative about a Belgian Eastern Front volunteer influenced attitude change (assessed by computing the difference between pre- and post-attitudes for each item). In addition, age, subjective level of knowledge, level of identification with Belgium, and resistance in family were included as predictors because these variables correlated significantly with the majority of the attitudes’ variables regarding collaboration and repression.

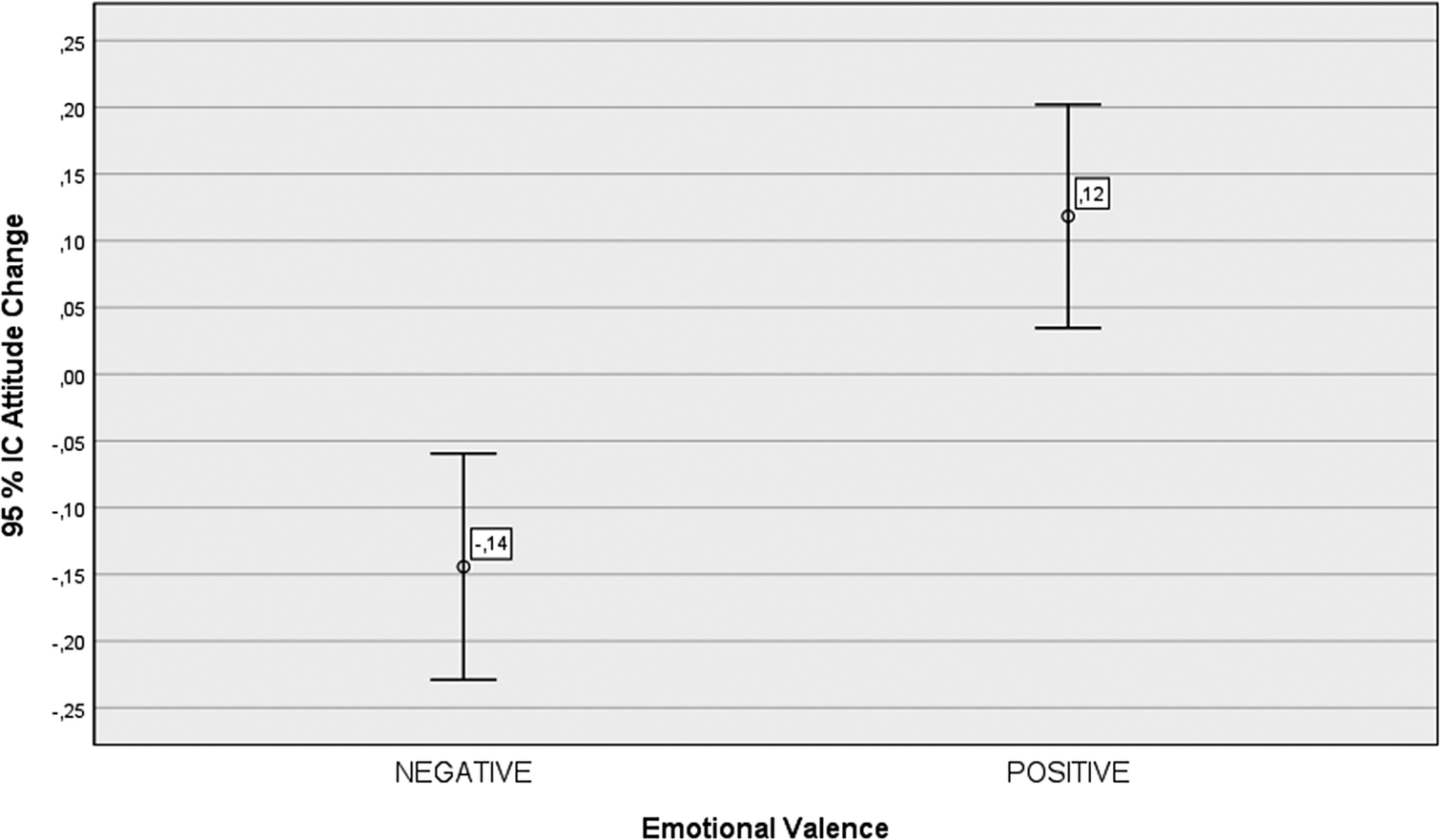

As hypothesised, the emotional valence of personal narratives influenced the direction of attitude change: F(1, 148) = 20.81, PRE = 0.13, p = <.001 (Figure 4). The positively framed interview led to more positive attitudes towards collaborators and a more nuanced view on repression (M att_change = 0.12, SD = 0.37), while the negatively framed interview demonstrated a significant impact in the opposite direction, leading to less favourable attitudes towards collaboration and regarding repression as more justified and moral (M att_change = −0.14, SD = 0.37). None of the control variables emerged as statistically significant predictors for attitude change.

Figure 4. Graph of the model representing attitude change as a function of emotional valence.

In addition, emotional valence influenced attitude change regarding collaboration and repression in the same direction, whether analysed individually or together, with respective test values of F(1,148) = 8.91, PRE = 0.10, p = .003 and F(1,48) = 20.04, PRE = 0.13, p = <.001. The negatively valenced interview resulted in mean levels of attitude change of −0.16 (SD = 0.50) for collaboration and − 0.15 (SD = 0.55) for repression, while the positively valenced interview led to changes of 0.08 (SD = 0.41) and 0.22 (SD = 0.57), respectively (Table 3).

According to the model we constructed based on Fisher’s narrative paradigm (Figure 1), transportation into the storied world and character identification (both with the father and the son) should also predict attitude change after controlling for the previously mentioned factors. Results showed that character identification with the son was not significant: F(1, 148) = 1.14, PRE = 0.02, p = .288 with B ID_Son = 0.038, 95% confidence interval (CI) [−0.032–0.107]. However, transportation and character identification with the father significantly predicted attitude change, respectively F(1, 148) = 7.63, PRE = 0.06, p = .006 and F(1,148) = 8.02, PRE = 0.06, p = .005. The higher the degree of transportation and character identification with the father, the bigger the change in attitude (B Transportation = 0.151, 95% CI [0.043, 0.259]; B ID_Father = 0.088, 95% CI [0.027–0.150]). Although character identification was higher for the narrating son than for the father on average, only identification with the father significantly predicted attitude change.

To test the robustness of emotional valence in conjunction with transportation and identification with the father, as they are predictors within Fisher’s narrative paradigm, we performed a linear regression combining them and controlling for the same factors. The results demonstrated that emotional valence plays a major role in predicting attitude change towards collaboration and repression, as it was the only predictor remaining significant: F(1,146) = 12.82, PRE = 0.16, p = <.001.

The mediating role of discrete emotions

The second hypothesis explored the mediating role of induced discrete emotions on the relationship between the emotional valence of a narrative and attitudes towards collaboration and repression. For this purpose, the fourth model of the PROCESS macro extension on SPSS was used (Hayes, Reference Hayes2022). The results provided insights into the direct, indirect, and total effects of emotional valence on attitude change in the presence of the mediating variable: intensity of a specific induced emotion. We introduced the discrete emotions experienced at least at minimal levels by participants (i.e., above 1) as mediating factors in the model: sadness, shame, anger, disdain, injustice, disgust, and compassion. The findings revealed no significant indirect effects. This means that no conclusion can be drawn regarding the mediating role of these discrete emotions on attitude change towards collaboration and repression.

Discussion

This study investigates how the emotional framing of a second-hand testimony about a Belgian Eastern Front volunteer during WWII shapes Belgians’ attitudes towards collaboration and repression. Through the lens of emotions, we applied Fisher’s narrative paradigm to second-hand testimonies about a controversial past and explored the social implications of using emotional and personal narratives in media to shape attitudes.

The results confirmed the hypothesis that emotional framing affects attitude change. In the interview where the son expressed understanding for his father’s past (positive valence), participants became more tolerant of collaboration and more critical of repression, viewing it as overly harsh. Conversely, in the interview where the son expressed anger and disgust (negative valence), participants viewed collaboration less favourably and regarded repression as justified and moral. These findings support the idea that emotionally framed information significantly influences attitudes.

While emotional narratives personalise history and encourage dialogue about difficult pasts (Bouchat et al., Reference Bouchat, Klein and Rosoux2016; Erll and Hirst, Reference Erll and Hirst2023; Van Bergen et al., Reference Van Bergen, Evans, Harris, Branagh, Macabulos and Barnier2024), which might be instrumental in collective memory construction (Rosoux, Reference Rosoux, Caluwaerts, Reuchamps and Exceptionalism2021), they can also be used manipulatively, particularly in a digital age dominated by (mis)information and echo chambers (Kligler-Vilenchik et al., Reference Kligler-Vilenchik, Tsfati and Meyers2014). The misuse of these narratives risks exacerbating divisions, especially on difficult and controversial topics (e.g., wars of communication; Smoor, Reference Smoor2017). As such, it becomes imperative to continue exploring their effects, recognising both their potential to engage the public with significant historical pasts and the risks they pose for manipulation (Wertsch, Reference Wertsch2002; Hoeken and Sinkeldam, Reference Hoeken and Sinkeldam2014).

However, the overall change in attitude was modest, with emotional valence accounting for only 13 per cent of the observed change in attitudes. When including transportation into the storied world and identification with the father in the model, emotional valence emerged as the only significant variable, explaining 16 per cent of attitude change. These results underscore the value of incorporating emotional dimensions into narrative models and the need for further research to enhance their explanatory power (Green and Brock, Reference Green and Brock2000; de Graaf et al., Reference de Graaf, Hoeken, Sanders and Beentjes2009; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee and Baezconde-Garbanati2013). This is particularly relevant given that, contrary to findings in the existing but limited literature, the mediating effect of discrete induced emotions did not yield significant results. The emotional framing is expected to induce emotions in the audience by increasing interest and focussing attention on their own emotional reactions, which enhances memory encoding and leads to lasting changes in attitudes (Holland and Kensinger, Reference Holland and Kensinger2010; Volkman and Parrott, Reference Volkman and Parrott2012; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee and Baezconde-Garbanati2013; Hoeken and Sinkeldam, Reference Hoeken and Sinkeldam2014; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Chrysochou, Christensen, Orquin, Barraza, Zak and Mitkidis2019). The non-significant results may reflect the relatively low intensity of induced emotions, possibly influenced by the narrative’s second-hand account and text-based medium. A meta-analysis showed that films are more effective at inducing emotions than readings (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Chan, Heintzelman, Tay, Diener and Scotney2020). However, studies on narrative communication have yielded mixed results regarding the most persuasive format, often examining cognitive and emotional mediators separately (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Chan, Heintzelman, Tay, Diener and Scotney2020; Oschatz and Marker, Reference Oschatz and Marker2020).

Although participants seemed to identify more with the son of the former collaborator, our data indicate that identification with the father figure, the Eastern Front volunteer himself, better predicted attitude change towards collaboration and repression. Future research could benefit from developing autobiographical first-person narratives through video interviews. Allowing the person directly involved to express their emotions authentically could evoke a stronger emotional response from the audience, enabling a more detailed examination of the interplay between emotional valence, emotional responses, and attitude change.

Conclusion

As storytelling humans, we shape our identities, social relationships, and perceptions of the world by discussing and remembering the past to navigate our future. This study improves our understanding of how the emotional framing of a personal narrative about a former Belgian Eastern Front volunteer during WWII influences audience attitudes towards collaboration and repression. The positively valenced interview promoted more understanding attitudes regarding collaboration and nuanced views on repression, while the opposite occurred with the negatively valenced story. The results imply that the emotional framing of storytelling may, though modestly, challenge attitudes about a difficult past rooted in collective memories. Nevertheless, the role of emotions needs further investigation, particularly through the development of first-person narratives to elicit stronger emotional reactions. Furthermore, future research should explore other dimensions, such as the medium of narrative presentation, which plays a crucial role in today’s media landscape and in how history is taught in schools.

Data availability statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are openly available on OSF at https://osf.io/f83h7/.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their colleagues from the project, Louise Ballière and Wouter Reggers, for their help with the Dutch translation of the interviews and dissemination of the questionnaires.

Funding statement

The authors are the members of a project titled ‘The transmission of memories related to stigmatisation: Official and family memories related to collaboration and colonisation in Belgium’ (RE-Member), funded by a UCLouvain Concerted Research Action grant (ARC 20/25–110). Olivier Luminet is the Research Director of the Funds for Scientific Research (FRS/FNRS).

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors declare that this manuscript is original work and has not been published before, nor is it being considered for publication elsewhere, whether in printed or electronic form. However, the original idea for this article was presented in a grant proposal for an UCLouvain Concerted Research Action project titled ‘The transmission of memories related to stigmatisation: Official and family memories related to collaboration and colonisation in Belgium’ (RE-Member: ARC 20/25-110).