In April 1667, John Locke departed his lodgings in Christ Church, Oxford for the London household of Anthony Ashley Cooper, Lord Ashley.Footnote 1 Although Locke's day-to-day activities are not precisely known, the writing of the earliest drafts of his Essay Concerning Toleration occurred during this period, specifically after the publication of Sir Charles Wolseley's Liberty of Conscience, the Magistrates Interest in the autumn of 1667.Footnote 2 The impetus for the Essay is a matter of debate. The fall of the Earl of Clarendon after the Dutch raid on the Medway (19–24 June 1667) had spurred nonconformists to press for a new church settlement, reversing or ameliorating the persecutory regime that had taken hold since the Restoration, when Nonconformist worship was assailed by the successive passage of the Act of Uniformity (1662), the Conventicle Act (1664), and the Five Mile Act (1665). The possibility that Charles II would issue a bill for the “comprehension” or “indulgence” of Nonconformity—making his rule congenial to the sizeable corps of Dissenters it had previously discountenanced by comprehending their worship within the Church of England or indulging their worship outside it—prompted a wave of publications on the justification or dangers of religious toleration.Footnote 3 Locke's position on this matter had evolved markedly since 1660–62 and his Two Tracts on Government. The latter had defended the power of the magistrate to “impose and determine” aspects of worship—the wearing of the surplice, for example—that Dissenters had described as “adiaphora” or “things indifferent” to the question of salvation.Footnote 4 The stringency of the Tracts stemmed, in part, from an evident fear of the return of seditious violence, which defenders of the Church of England had attributed to the rise of Nonconformity during the Civil Wars. Yet Locke's position subsequently altered, particularly after his exposure to the religious pluralism of Cleves in 1665–6, when he visited the duchy in the train of a diplomatic mission.Footnote 5 By the following year, having commenced a draft of the Essay, Locke would move towards the rudiments of his Epistola de Tolerantia, in which the imposition of uniformity in matters of worship and “speculative belief” was criticized on several interdependent grounds: soteriological, epistemic, and political.

Locke's path to this position is the subject of considerable scholarship, lately enriched by the meticulous work of Jacqueline Rose and Jeffrey Collins.Footnote 6 The textual milestones on this path—Locke's Two Tracts, his Reasons for Tolerateing Papists Equally with Others, and his Essay—are typically studied alongside a set of notes to A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie, a work of 1669 by the Church of England cleric and controversialist Samuel Parker (1640–88). The notes were purchased by the Bodleian Library from a private owner in 1954 and first published—in part—in Maurice Cranston's John Locke, A Biography (1957).Footnote 7 Mark Goldie subsequently provided an abbreviated transcription of the notes in his edition of Locke's Political Essays (1997), after which J. R. Milton and Philip Milton included a full-scale transcription in their Clarendon edition of Locke's Essay Concerning Toleration.Footnote 8 The notes—particularly in those places in which Locke voiced a judgment of his own and departed from ad litteram transcription—appeared to be preparatory to a direct response to Parker's Discourse. But no such work was ever published and no further evidence of the project appeared to survive.

The Miltons were the first to observe that the notes on Parker appeared to be “stray survivors from a considerably fuller body of notes that have since been lost.”Footnote 9 The following article confirms the Miltons’ judgment. In 2016, J. C. Walmsley discovered a set of notes in Locke's handwriting, which constitute at least part—and perhaps all—of the missing notes that the Miltons conjecturally described. The notes are now preserved in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: a manuscript bifolium (now disjoined) of approximately three thousand words, with Locke's remarks and queries regarding the preface and first 158 pages of Parker's Discourse, presented under the headings “Magistrate” and “Church.” The previously known Bodleian manuscripts comprise three bifolia, the first a paraphrase of pages 1–64 of the Discourse, the second a set of queries regarding pages 11–30, and the third a set of queries regarding pages 144–53. Until its discovery in 2016, the Chapel Hill manuscript was unknown to scholars: no publications refer to its existence and no catalogue advertising its sale can be found. The following article provides the first discussion and transcription of the manuscript. It begins by contextualizing Parker's Discourse (section I), before addressing the implications of the discovery for future studies of Locke's theory of toleration and his authorial and secretarial practices, c.1669—in particular, it draws attention to the principal significance of the manuscript, as the first evidence of Locke's commitment to the doctrine that minimalistic theism would suffice for peaceable coexistence in any civil society (section II). The article then turns to a reconstruction of the provenance, structure, and content of the manuscript (section III) and it concludes with a transcription of the manuscript, and a retranscription of its counterparts in the Bodleian (section IV). In providing this full-scale transcription, the article constitutes the first complete edition of Locke's extant commentary on Parker.

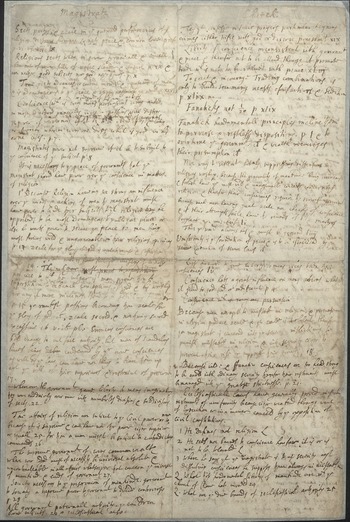

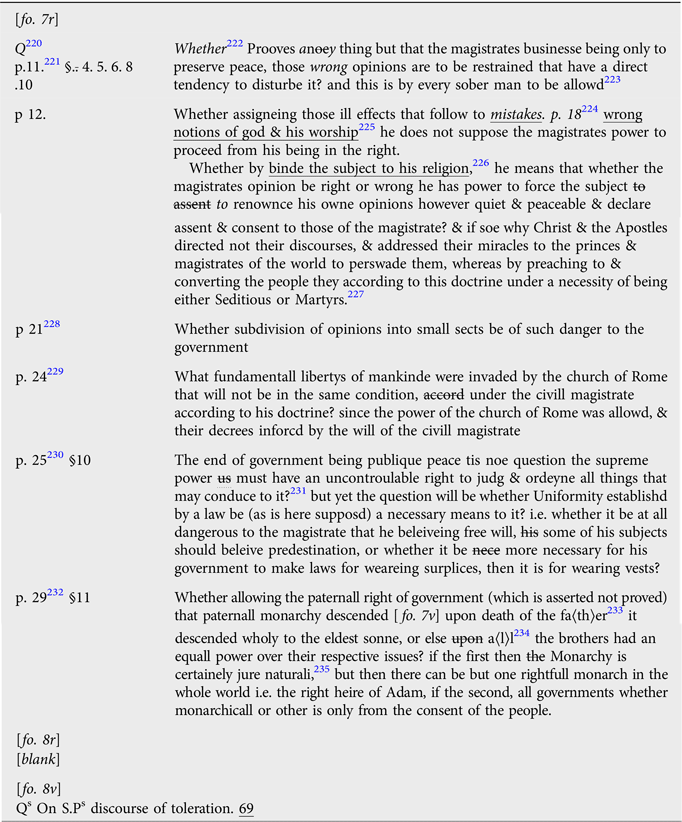

Fig. 1. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, Southern Historical Collection, 03406 (Folder 323), fo. 1r.

I

Parker was born in Northampton in September 1640.Footnote 10 He entered Wadham College, Oxford in September 1656,Footnote 11 where he matriculated in October 1657, and graduated BA in February 1659.Footnote 12 His reputation at this time was apparently as an ascetic puritan. According to his vita in Anthony Wood's Athenae Oxonienses (1691–2), Parker was “so zealous and constant a hearer of the prayers and sermons … a receiver of the sacraments and such like, that he was esteemed one of the preciousest young men in the university.”Footnote 13 A contretemps with the warden of Wadham, Walter Blandford (1615/16–75), impelled him to enter Trinity College, Oxford in October 1660, where he graduated MA in July 1663,Footnote 14 and began an association with Ralph Bathurst (1619/20–1704), a fellow of the college.Footnote 15 Parker would later attribute to Bathurst's influence his “first Rescue from the Chains and Fetters of an unhappy Education.”Footnote 16 This eschewal of puritanism was followed swiftly by Parker's ordination in February 1665.Footnote 17 In the same year, his Tentamina de Deo (1665) was dedicated to Gilbert Sheldon (1598–1677), the Archbishop of Canterbury.Footnote 18 The Tentamina was reviewed positively by Henry Oldenburg (c.1619–77) in the first volume of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society,Footnote 19 and supplemented by two elucidations, A Free and Impartial Censure of the Platonick Philosophie (1666) and An Account of the Nature and Extent of the Divine Dominion and Goodnesse (1666), which were reissued in a conjoined second edition in 1667.Footnote 20 These works had several preoccupations: positing a compatibility between the new natural philosophy and “scholastic theology,” disinfesting Christianity of Platonism, defending the neurology of Thomas Willis (1621–75),Footnote 21 and attacking the Origenist position on the preexistence of the soul and the work of its alleged revivalists Henry More (1614–87) and Joseph Glanvill (1636–80).Footnote 22 With the nomination of John Wilkins (1614–72), Parker was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in June 1666.Footnote 23 In “Michaelmas 1667”Footnote 24 he was chosen to serve as Sheldon's domestic chaplain. In October he was made rector of Chartham in Kent and created MA by incorporation in Cambridge.Footnote 25

In roughly November 1669, A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie was published in London, bearing “1670” as its date of publication. Parker's publisher John Martyn (c.1619–80) had entered the work with the Stationers’ Company in September 1669.Footnote 26 A second edition—described as such in the term catalogues, but not the work itself—was issued in February 1670,Footnote 27 with minor corrections to the signatures and pagination, as well as the interpolation of the adjective “External” before the word “Religion” in the subtitle: Wherein The Authority of the Civil Magistrate Over the Consciences of Subjects in Matters of External Religion is Asserted. The Miltons describe Parker's work as a “belated” contribution to the debate of 1667–8 over the prospect of a bill of indulgence or comprehension.Footnote 28 The titular allusion to Richard Hooker's Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie (1594–7) served to align its argument with the “the flagship text of late-Elizabethan conformity,”Footnote 29 associating Hooker with a campaign that had—through Sheldon's offices—orchestrated a barrage of rejoinders to tolerationists in the previous year.Footnote 30 A third but substantively unaltered edition, anonymous like the first and second, was issued in November 1670, although dated “1671,”Footnote 31 to coincide with the publication of a separate and still anonymous Defence and Continuation of the Ecclesiastical Politie (1671),Footnote 32 in which Parker reiterated his initial case at greater length—the Discourse was 326 pages, the Defence was 750 pages—and responded to Truth and Innocence Vindicated … A Survey of a Discourse Concerning Ecclesiastical Polity (1669), by John Owen (1616–83), the doyen of Congregationalism.Footnote 33

Owen had initially asked Richard Baxter (1615–91) to respond to Parker.Footnote 34 Baxter having declined, Owen completed the task himself, in a point-by-point confutation of the first six chapters of Parker's work. This was accompanied, in 1669, by A Case of Conscience … Together with Animadversions on a New Book, Entituled, Ecclesiastical Polity by John Humfrey (c.1621–1719), the Nonconformist proponent of comprehension. The impetus for Owen's and Humfrey's interventions was, in part, Parker's unusually intemperate style.Footnote 35 The Discourse teemed with aspersions about Nonconformists: “Brain-sick people,” “Madmen,” “vermin.”Footnote 36 Parker's subsequent preferment is often attributed to the depth of this commitment to “Sheldonianism.”Footnote 37 In May 1670 he was appointed archdeacon of Canterbury.Footnote 38 In July 1671 he was preferred to the living of Ickham in Kent.Footnote 39 In November 1671 he was awarded a DD and “perhaps D. Med.” in Cambridge.Footnote 40 In November 1672 he was admitted to a prebend in Canterbury.Footnote 41 Five months earlier, in June, a posthumous work by John Bramhall (1594–1663) was entered in the term catalogues: Bishop Bramhall's Vindication of Himself and the Episcopal Clergy, from the Presbyterian Charge of Popery, as it is Managed by Mr. Baxter in his Treatise of the Grotian Religion (1672).Footnote 42 Parker contrived to adjoin a separate treatise to Bramhall's critique of Baxter's Grotian Religion Discovered (1658), in which he renewed the Discourse's attack on Nonconformity. Baxter contemplated a response,Footnote 43 but it was Andrew Marvell (1621–78), the parliamentarian and poet, who stridently intervened.

In around April 1672, Marvell commenced work on The Rehearsal Transpros'd.Footnote 44 He completed it in September 1672; it was published in December, pirated twice, and swiftly followed by a second edition in around January 1673.Footnote 45 In response, Parker reprinted his preface to Bramhall's Vindication and completed A Reproof to the Rehearsal Transpros'd (c. May 1673),Footnote 46 to which Marvell answered with a Second Part to his Rehearsal (November 1673), subjecting Parker to withering criticism, partly in the form of a derisive biography.Footnote 47 The controversy soon widened. Henry Stubbe's Rosemary and Bayes (1672) attacked both Marvell and Parker. John Humfrey's The Authority of the Magistrate, about Religion (1672) and Robert Ferguson's A Sober Enquiry into the Nature, Measure, and Principle of Moral Virtue (1673) criticized Parker, without defending Marvell. Edmund Hickeringill's Gregory, Father-Greybeard (1673) defended Parker—and criticized Marvell sufficiently to warrant the latter's ridicule in the Second Part to his Rehearsal.

The debate made Parker synonymous with hierocratic intolerance.Footnote 48 In 1673, this notoriety was compounded by an embarrassing miscalculation, committed in Parker's role of licenser to the press, which he held ex officio as a chaplain to Sheldon. Parker had licensed Mr. Baxter Baptiz'd in Bloud; or, A Sad History of the Unparallel'd Cruelty of the Anabaptists in New England (1673), a work narrated as a truthful tale of the murder by Nonconformist sectarians of “Benjamin Baxter,” a Church of England minister.Footnote 49 In May 1673 the Privy Council investigated the work and found its claims to be entirely fictitious.Footnote 50 Parker was compelled to acknowledge his error before the council,Footnote 51 as John Darby (d. 1704)—in all probability the printer of both parts of The Rehearsal Transpros'd—published an account of the affair.Footnote 52 Notwithstanding his appointment in August 1673 as master of the Hospital of Eastbridge in Canterbury, Parker's rise stuttered to a halt.Footnote 53 In 1673, he seems to have withdrawn from London to Kent, where he remained until 1684.Footnote 54 He declined to publish again until 1678, when he issued his Disputationes de Deo et Providentia Divina. The death of Sheldon in November 1677,Footnote 55 followed by the appointment of Parker's rival William Sancroft (1617–93) to the archbishopric of Canterbury, ended Parker's hopes for promotion to a bishopric—although only temporarily.Footnote 56

In the 1680s, Parker continued to write on matters of theology. A Demonstration of the Divine Authority of the Law of Nature and of the Christian Religion (1681) was joined by The Case of the Church of England Briefly and Truly Stated (1681), An Account of the Government of the Christian Church (1683) and In Religion and Loyalty (1684–5), arguing variously for the necessity of absolute obedience to a temporal sovereign and iure divino episcopacy. The accession of James II changed Parker's fortunes practically overnight.Footnote 57 In July–August 1686 James nominated Parker to succeed John Fell (1625–86) as Bishop of Oxford.Footnote 58 In the following year, Parker endorsed James's Declaration of Indulgence.Footnote 59 In August 1687 he was nominated president of Magdalen College, Oxford, designedly to pressure the fellowship into admitting Roman Catholics.Footnote 60 A purge of twenty-five fellows in November was followed, in the next month, by the publication of Parker's Reasons for Abrogating the Test (1687), which questioned the Church of England's stance on transubstantiation.Footnote 61 Parker's subsequent presidency was characterized by suspicion of his crypto-Catholicism, but it was cut short by illness. He died in March 1688 and he was buried in Magdalen's chapel, without a memorial. His self-authored and tendentious Latin epitaph is reported by Wood:

II

There is no evidence that Locke and Parker ever met, either during the period when they overlapped in Oxford (c.1656–c.1664) or at any subsequent time, prior to Parker's death, when Locke resided in England (1664–75, 1679–83). There are no extant letters between Locke and Parker, and there is no evidence that they ever exchanged letters. A letter of August 1687 from James Tyrrell (1642–1719) to Locke, then an exile in the Netherlands, refers to Parker as “our old Friend Dr: P.,”Footnote 63 but the intimation is sarcastic. Parker's name occurs on only three further occasions in Locke's correspondence: in a letter from Tyrrell of November 1687, referring to Parker's intrusion as president of Magdalen,Footnote 64 in a letter from Tyrrell of July 1690, briskly complimenting Parker's Demonstration … of the Law of Nature,Footnote 65 and in a letter from Benjamin Furly (1636–1714), recalling that he and Locke had “read together” a satire on Parker's Reasons for Abrogating the Test.Footnote 66 Locke's booklists record a copy Gilbert Burnet's eight-page critique (1688) of Parker's Reasons for Abrogating the Test, and a copy of Parker's Reproof to Marvell's Rehearsal Transpros'd.Footnote 67 Locke possessed two copies of the First Part of Marvell's work—the pirated imprint of the first edition and bona fide second edition—and one copy of its Second Part,Footnote 68 a copy of an anonymous contribution to the Parker–Marvell controversy,Footnote 69 and a copy of Hickeringill's Gregory, Father-Greybeard.Footnote 70

Martin Dzelzainis and Annabel Patterson have contended that Marvell, in his search for exempla of “disreputable conduct by figures in the past who could be seen as analogies for Parker,”Footnote 71 made use of Locke's personal library while writing the First and Second parts of his Rehearsal Transpros'd. As an impecunious parliamentarian, deprived of the money to purchase books by the prorogation of Parliament between April 1671 and February 1673, Marvell appears to have relied on the library of his patron, Arthur Annesley (1614–86), the first Earl of Anglesey. The latter's vast collection of books contained all of the titles cited by Marvell in the Rehearsal Transpros'd, save for six works in specific editions that happen to be present in Locke's booklists: Sir William Davenant's Gondibert (1651),Footnote 72 Samuel Butler's Hudibras (1663–4),Footnote 73 Hickeringill's Gregory, Father-Greybeard, Richard Hooker's Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie (1666), Martin Del Rio's Disquisitionum magicarum (1600),Footnote 74 and Ammianus Marcellinus’ Rerum gestarum (1609).Footnote 75 The difficulty with this claim is that, excepting the 1666 edition of Hooker, which Locke never owned,Footnote 76 and a copy of Gondibert, which he demonstrably kept in his rooms in Christ Church in July 1681,Footnote 77 we cannot establish when Locke acquired each title, and thus whether they were accessible to Marvell in 1671–3. Marginal dashes and a page list in Locke's copy of Hickeringill suggest that Locke read the work, but this has no bearing on when he acquired it.Footnote 78 Locke's copies of Butler, Del Rio, and Ammianus show no signs of consultation by Marvell, although one should note the intriguing presence of a versified Latin translation in Locke's hand on the flyleaf of his copy of Hudibras, which one might—outlandishly—attribute to Marvell's poetical influence.Footnote 79 Locke's opinion of Marvell's Rehearsal is unknown—his copies do not bear any annotations and he does not refer to Marvell's work in any extant manuscript or publication—and no evidence survives to show that he ever met Marvell, yet an observer as informed as Roger L'Estrange (1616–1704) could wager in 1681 that Marvell was “very particularly acquainted” with the author of a Letter from a Parliament man to his Friend, Concerning the Proceedings of the House of Commons (1675), a pamphlet that probably issued from Shaftesbury's circle.Footnote 80

Notwithstanding the possibility of his collaboration with Marvell, Locke's interest in Parker is recoverable only from his notes to the latter's Discourse. Locke bought a copy of Parker's work soon after the publication of the first edition. A record of the purchase in his memorandum book for 1669 (“Parkers disc.—0—3 〈shillings〉—6 〈pence〉”) occurs between entries on 15 November and 2 December,Footnote 81 which one might safely conjecture delimits the period during which he acquired Parker's work.Footnote 82 If the record of purchase is a terminus a quo in dating his notes to the Discourse, a terminus ad quem is provided by the endorsement he supplied to a portion of the notes: “69.” This is a notation that Locke would have used until 25 March 1670,Footnote 83 although it is possible that Locke might have emended his notes after that date without recording the day or year of the emendation. Locke's notes match only the pagination of the first edition, which could provide an additional temporal delimitation: if the second or third edition were available, Locke might have used it. The absence of the Discourse from Locke's booklists—or any extant copy that can be identified as Locke's own, or any references within the notes to other publications—complicates the task of establishing when Locke desisted in commenting on the work, which is only compounded by the mystery surrounding Locke's activities as a factotum in Ashley's household, c.1667–9.

Locke's intentions in writing his Essay Concerning Toleration remain obscure. The recent recovery of his Reasons for Tolerateing Papists Equally with Others has clarified the matter slightly,Footnote 84 but it is difficult to favour one of several possibilities in explaining the Essay's aims. The Reasons and the Essay might have originated in Ashley's instruction to formulate a rationale for an indulgence of Nonconformists, or even Catholics, in anticipation of Charles II's or the Cabal ministry's designs after the fall of Clarendon. Yet Ashley's inclinations are difficult unambiguously to reconstruct between the aborted Declaration of Indulgence of 1662 and the Treaty of Dover of 1670. The Miltons are thus rightly cautious of attributing the Essay to Ashley's direction, as “no evidence whatever has survived” of it.Footnote 85 The intended audience for the Essay is similarly ambiguous: its use of the second person is too informal to suggest Charles II as a reader, at least.Footnote 86 It is clear that Locke—whether independently of Ashley's purposes, in anticipation of them, or by Ashley's direction—had begun to familiarize himself with arguments in favor of the toleration of Nonconformists in late 1667, when Wolseley's Liberty of Conscience was published. The latter was issued by a coalition of printers and writers surrounding the Earl of Anglesey, including Marvell's publisher Nathaniel Ponder (1640–99) and John Darby.Footnote 87 But the evidence of Locke's connection to the group is tenuous before March 1670, when the “longstanding enmity” that had characterized Anglesey's relationship with Ashley was briefly set aside after the renewal of the Conventicle Act by the Cavalier Parliament.Footnote 88 Ashley dined with Anglesey on several occasions in 1671–2,Footnote 89 and he protected Ponder in January 1673 when the latter was censured for publishing the First part of Marvell's Rehearsal Transpros'd.Footnote 90 It is not hard to imagine Ashley encouraging Locke in a similar enterprise, shortly after the publication of the Discourse. One of the three extant library catalogues of Ashley's grandson, the third Earl of Shaftesbury (1671–1713), records a copy of the Discourse, and one could plausibly assume that it was the copy used by Locke in preparing his notes on Parker's work.Footnote 91 This is not to endorse the contention, pace Dzelzainis and Patterson, that the notes reveal Locke “bringing his views closer to [Ashley's].”Footnote 92 This begs the question. After all, what were Ashley's views? More objectionably, it severs the threads of continuity in emphasis and argumentation between the notes and Locke's Essay Concerning Toleration.

The notes reveal Locke's minute attention to Parker's reasoning. In the Chapel Hill manuscript, more so than in the Bodleian manuscripts, Locke engages in extensive transcription of Parker's wording, studded with queries marked “Q” for “Quaere” and signed “JL” or “L.” The format of the notes is discussed below, but it is important to note the manner in which the notes move from excerpting the text under review to formulating a pointed response or reflection. The effect is similar in the Reasons, in which Locke used Wolseley's arguments as a foil to consider whether the toleration of Nonconformists would inadvertently favor Catholics or whether the toleration of Catholics might find its rationale in the “interest” or prosperity it entrained. Locke's Essay would echo Wolseley on this point, in buttressing a case for toleration by referring to its promotion of domestic “riches,”Footnote 93 and it is not implausible to associate Locke's interest in Parker with an anxiety about the latter's criticism of the court's warmth for Wolseley's politique reasoning, as Collins has recently argued.Footnote 94 In Collins's judgment, Parker jolted Locke out of his sympathy for Wolseley's position, and towards the elaboration of a clearer defence of freedom of speculative belief, detachable from any consideration of the magistrate's “interest.” But this difficulty constitutes only one portion of Locke's transcriptions and queries, which touch on several components of Parker's argument.

The earliest scholarship on the latter had tended misleadingly to characterize it as “Hobbism pure and simple.”Footnote 95 Parker's language, stretching back to a laudatory citation of De Cive in Of the Nature and Extent of God's Dominion (1666),Footnote 96 had drawn on Hobbes's metaphors, to the extent that Parker himself admitted his Discourse had “savour[ed] not a little of the Leviathan.”Footnote 97 It is now generally accepted, however, that the resemblance of Parker's ecclesiology to Hobbes's in Leviathan is “overstated,”Footnote 98 or arose merely from the latter's conceptual and rhetorical “proximity” to the Erastianism countenanced by Anglican royalists after 1660.Footnote 99 Parker never accepted Hobbes's hyper-Erastian empowerment of the civil sovereign to dictate the theology of the established church. Perhaps more importantly, he never endorsed iure humano episcopacy, which he later decried in criticisms of Edward Stillingfleet's Irenicum (1659) and Mischief of Separation (1680).Footnote 100 The irony of Parker's intentions, supposedly to associate Wolseley's “interest”-centered tolerationism with the chimera of a state grounded exhaustively in the areligious self-interest of its inhabitants, or Hobbesianism simpliciter,Footnote 101 was that it was countervailed by a defence of temporal sovereignty so full-throated that it was—in Locke's judgment—indistinguishable from “Mr Hobbs's doctrine.”Footnote 102 The accusation was characteristic of the contemporary association of magisterial intervention in religious worship with “Hobbism” pur sang, and it betokened the flexible and polemical properties of that label. But the accusation stuck insistently to Parker for the remainder of his life. In March 1685 Henry Dodwell (1641–1711) could assure a correspondent that his friend's Discourse was not congenial to Hobbes, in spite of appearances.Footnote 103

Parker used the Discourse to defend the royal prerogative in “Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction,” while insisting that it ought not to be exercised by Charles II in favour of Nonconformity: Charles's principal obligation was to preserve the peace of his subjects, which was securable only via uniformity in outward religious practices. Freedom of “conscience,” in Rose's summary of Parker's reasoning, “was a freedom of judgement, not a freedom of action in worship.”Footnote 104 This was the significance of Parker's interpolation of External in the title page of the second edition. He reserved to the magistrate a power to impose “outward Practices” in religious worship. These “publique and visible” practices were controllable by civil authority, nourishing the allegation of Parker's sympathy for Hobbes's vision of a sacerdotal magistrate. But conscience, Parker maintained, was nonetheless inviolable.

These arguments plainly offended the principles that Locke had adumbrated in the manuscripts of his Essay Concerning Toleration in 1667–8. Parker permitted freedom of speculative belief, but insisted on outward conformity. The Essay had claimed that imposition in matters of conscience lay outside the competence of the magistrate, and this argument applied equally to imposition in matters of worship. Parker's attempt to disassociate freedom of conscience from freedom of external worship was an ingenious response to this proposition, but it could hardly persuade Locke that compulsion of external worship was compatible with the inviolable status of one's conscience. Locke's difficulty lay partly in how he could explain why this was specious, but a more urgent problem stemmed from his claim that religious sects were persecutable if their beliefs or their worship impinged upon civil matters. Catholics were excepted from toleration precisely because their theology required a commitment to the universal sovereignty of the Pope. If Catholicism was intolerable on this basis then so too was any religious sect whose doctrines carried deleterious implications for civil peace. Yet this was the nub of Parker's indictment of Nonconformity, and its force is obvious when one peruses Locke's commentary on the Discourse.

The Chapel Hill manuscript, in particular, focuses on Parker's insistence that unchecked Nonconformity would revive the antinomian political theology of the Civil Wars. Parker's “ecclesiastical politie” is invested with the necessary power to ensure the safety of its subjects. In the Chapel Hill manuscript, Locke concentrates on the scope of this power. “He sets noe bounds to conscience how far it is or is not to be tolerated,” Locke notes, before asking, “What are the due bounds of ecclesiastical authority?”Footnote 105 Is anything, in matters of conscience, invulnerable to the oversight of the magistrate or the established church? Parker inveighs against the invasion by the Catholic Church of the “Fundamental Liberties of mankind.”Footnote 106 But “[w]hat,” Locke asks, “[are] those fundamental libertys of mankinde … which the church of Rome hath invaded?”Footnote 107 Locke adverts to the inconsistency in Parker's reasoning: Rome is contemptible because it invades precisely the liberties that the Discourse denies to Nonconformists.

The notes turn to Parker's emphasis on outward conformity. The dictates of conscience are not matters that can concern the magistrate until they issue in external actions. Only “outward Actions,” Parker argues, are “subject to the Cognizance of Humane Laws.”Footnote 108 “Opinions”—“moral or religious”—are outside the magistrate's cognizance until they are instantiated by action. But “are [opinions] not capable of haveing any influence upon the Publique good or ill of man kinde?” Locke asks.Footnote 109 If the measure of a magistrate's authority is the preservation of civil peace, the latter would require the invigilation of “opinions.” Parker insists that inward judgment is “inviolate.”Footnote 110 If its protection against civil compulsion is assured, “it matters not … what restraints are laid upon our Outward Actions.”Footnote 111 But this can only be true if our outward actions do not violate the dictates of our conscience: “whether … [this] be true in any thing but barely what I judg in its self indifferent,” Locke notes, “but what becomes of those things I judg unlawfull”?Footnote 112 Parker alternates between treating the debate as one pertaining restrictedly to “ceremonies,” which could be said to encompass only adiaphora, and one pertaining capaciously to “religion,” which must encompass one's speculative beliefs, including in matters that are not “indifferent.” Which is it? Locke demands. “Whether haveing in the foregoing §§s & this spoken only of ceremonys he doth not here call ceremonys religion”?Footnote 113 Locke quotes Parker in noting that the “dutys” of religious devotion are not “essentiall parts of religion.” “Devotion” is performed only and superfluously because it tends “to the practise of vertue.”Footnote 114 Following Parker's own logic, imposition in matters of “ceremony” must be dispensable to the “essentiall” object of religious belief, making any insistence on imposition in external worship rather similar to the politique position that Parker ostensibly eschews.

This precedes the most remarkable statement in the Chapel Hill manuscript. Parker observes that “Religion … is the strongest Bond of Laws, and only support of Government.” “[W]hen the Obligations of Conscience and Religion are Cashier'd, men can have no higher Inducements to Loyalty and Obedience, than the Considerations of their own Private interest and Security.”Footnote 115 Parker, however, neglects to define “religion,” yet again. Is it outward conformity, in our performance of mandatory ceremonies, or inward belief, in our assent to an article of faith? After summarizing Parker's position on religious belief as a source of “obligation to obedience,” preferable simply to “self interest,” Locke asks whether “religion” should extend “any farther then a beleife of god in general. but not of this particular worship.”Footnote 116 Belief in God “in general”—detached from any ceremonial or doctrinal appurtenances—is sufficient to ensure the moral conduct of a political subject. Parker's insistence on particular ceremonies in religion—“why soe much stress & stir about ceremonys,”Footnote 117 Locke asks—distracts from the possibility of civil coexistence on the basis of mere theism. It is clear that Locke arrived at this position after carefully considering Parker's reasoning. The compositional layers of the manuscript show that he returned to Parker's point on our “obligation to obedience” only having read and summarized the ensuing pages of the Discourse: his comment on “beleife of god in general” is an interlineation.

The Bodleian manuscripts of Locke's commentary on Parker do not refer to this position. They echo many portions of the Chapel Hill manuscript. “What fundamentall libertys of mankinde were invaded by the church of Rome,” Locke asks again, in one of the Bodleian manuscripts.Footnote 118 They also elaborate on queries that the Chapel Hill manuscript presents only elliptically. In the latter, Locke notes that Parker supposes Nonconformists to be “always in mistakes.” As Locke adds, however, the knowledge of whether their practices or beliefs are erroneous is indeterminable in “indifferent” matters, which is precisely why they are “indifferent.” The Bodleian manuscripts expand on this point by asking whether Parker supposes “the magistrates power to proceed from his being in the right.”Footnote 119 This would postulate a basis for the magistrate's authority—rectitude in theology—that is separable from merely “preserving peace.” But how, Locke asks, can one resolve a contradiction between the imperatives of rectitude in theology and the imperatives of civil peace? The power to preserve the latter, the Bodleian manuscripts continue, “is by every sober man to be allowd.”Footnote 120 But either it can extend to any religious belief that the magistrate considers dangerous to civil peace, a point that is not short of “Mr Hobbs's doctrine,” or it cannot, in which case Parker concedes that there must be limits to the magistrate's authority. If those limits are determined by theology, the debate will return to the same impasse that characterizes the question of “indifferency.” In place of arguing over what is or is not indifferent, Locke implies in the Chapel Hill manuscript, it is easier merely to stipulate a subject's “beleife of god in general.”

The discovery of the Chapel Hill manuscript reveals that Locke had reached this conclusion by c.1669, where it had previously been thought that he had not contemplated it any earlier than c.1671, the point from which the Miltons had dated three manuscript additions to Locke's Essay Concerning Toleration.Footnote 121 These alterations, the Miltons maintained, expressed a “very different outlook” to the Essay: “a significant shift away from the views that Locke had maintained in 1667 and towards those expressed in the Epistola de Tolerantia.”Footnote 122 One of these alterations revealed Locke's hesitation to endorse the stance he had adopted in the “first draft” of the Essay, in which the magistrate was empowered to suppress religious dissent “if the professors of any worship shall grow soe numerous & unquiet as manifestly to threaten disturbance to the state.”Footnote 123 Instead, Locke deprived the magistrate of this power which, if consistently applied, would extend to any “things” which may “occasion disorder or conspiracy in a commonwealth.” “All discontented & active men must be removd,” Locke reasoned, in a reductio ad absurdum, “& whispering must be lesse tolerated then preaching.”Footnote 124 Nonconformism, Locke adds, will only become seditious when it is persecuted. The premises of this position are absent from the earlier versions of the Essay, the Chapel Hill manuscript, and the Bodleian manuscripts of Locke's commentary on Parker, the latter of which expressly concede to the magistrate a power to “restraine seditious doctrines.”Footnote 125 The second and third alterations reported by the Miltons are different, in that both are anticipated by the Chapel Hill manuscript. First, in his revision to the Essay, Locke notes that the determination of “indifferency” is a matter for the individual believer: “when I am worshiping my god in a way I thinke he has prescribd & will approve of I cannot alter omit or adde any circumstance in that which I thinke the true way of worship.”Footnote 126 Second, in his revision to the Essay, Locke notes that atheism is not entitled to toleration. Without “beleif of a deitie,” Locke writes, “a man is to be counted noe other then one of the most dangerous sorts of wild beasts & soe uncapeable of all societie.”Footnote 127 Locke's exception of atheists from toleration, reiterated infamously in the Epistola, is formulated here for the first time. Yet the minimalistic theism in the Chapel Hill manuscript—“beleife of god in general”—is a conceptual prerequisite of both approaches: the “individualistic”Footnote 128 notion of “indifferency” expounded by the revised Essay and the conceit that the absence of a belief in God is an insuperable barrier to our coexistence in any civil society, a doctrine that Locke shared with Parker, and many others, but distinctively coupled with minimalistic theism as its corollary. We now know that both doctrines are present—if only inchoately—as early as 1669.

This brings us to an obvious question about the Bodleian and Chapel Hill manuscripts: their purposes. Locke's queries and responses in the manuscripts are exiguous. It is possible that the manuscripts are only fragments of a larger corpus of notes on Parker, which Locke completed in 1669–70, but which are now not extant. The Essay Concerning Toleration is more far more elaborate and systematic, but it was nonetheless left unpublished. Every extant manuscript of the Essay terminates with a note that Locke would complete it “when I have more leisure.”Footnote 129 The Parker notes terminate in medias res, having reached only page 158 in its commentary on the Discourse.

Locke persistently hesitated to publish works that would attract attention to his political or religious sympathies. In April 1690, he complained bitterly to Philipp van Limborch (1633–1712) when the latter admitted that he had divulged Locke's authorship of the otherwise pseudonymous Epistola to a mutual friend.Footnote 130 It is difficult to attribute this anger to anything other than what Peter Laslett once described as Locke's “obsessive” caution: the Epistola can hardly have endangered Locke in the year of its publication.Footnote 131 It is possible that this same caution inhibited Locke from publishing against Parker. But other alternatives deserve consideration. In 1669–70 Locke became increasingly occupied in collaborating with Thomas Sydenham (1624–89) in medical practice, and he might not have had time to complete a full-scale response to either the Discourse or its Defence and Continuation.Footnote 132 In early 1671 Locke commenced Draft A of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding, again depriving him of the “leisure” to complete the Essay Concerning Toleration or a response to Parker.Footnote 133 Richard Ashcraft has suggested that Locke's reading of the Discourse might have served as a fillip for Draft A,Footnote 134 but it would be hard to associate the inspiration for Draft A with Parker's Discourse, tout court, in lieu of works within Locke's reach on the intellect, the soul, logic, medicine, and natural philosophy, to name only a few rival sources of inspiration for Locke's work.Footnote 135 If Locke desisted in responding to the Discourse, it is probably because his interests had settled elsewhere. An alternative possibility is that the impetus behind a response had abated when Locke learned that Anglesey's circle was preparing a response of its own. Locke presumably shelved his notes on Parker and later spectated contentedly, as Marvell entered the fray.

III

The Chapel Hill manuscript is preserved in the Wilson Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where it forms part of a collection donated by Preston Davie (1881–1967), an American attorney, serviceman, and collector.Footnote 136 The manuscript consists of two half-sheets, now disjoined, but apparently once forming a bifolium, each leaf measuring approximately 339 × 228 millimeters. The paper bears a countermark letter “H” (fo. 1) and watermark (fo. 2) of a horn and baldric in a coat of arms surmounted by a crown, followed, in vertical order, by a large “4,” and a combination of the letters “W” and “R”; this watermark closely resembles Heawood 2715.Footnote 137 Locke folded each half-sheet vertically, forming two columns on each page. On the recto and verso of the first leaf, the left-hand column is headed “Magistrate” and the right-hand column “Church.” On the recto of fo. 2, the left-hand column is headed “Magistrate” (again), but there is no heading on the right-hand column, and it appears that Locke's notes on the “Magistrate” continue from the bottom of the left-hand column on this page directly onto the right-hand column, and then conclude at the top of the left-hand column of fo. 2v (which has no heading). This columnar division of the manuscript resembles a similar arrangement in a manuscript of 1674, “Excommunication,” in which Locke and an unidentified scribe divided his observations into two columns: “Civill Society or the State” and “Religious Society or the Church,” on the basis that “There is 2 fold Society of which allmost all men in the world are Members and that from the 2 fold concernment they have to attaine a 2 fold happinesse, viz: That of this world and that of the other.”Footnote 138 This division might have appealed to Locke, in reading Parker, by revealing the limits of an attack on the Discourse as a species of Erastianism. Locke could follow Parker in disentangling the perspective of the “Magistrate” from the perspective of the “Church,” and formulate a response to each, in turn and independently.Footnote 139 The Chapel Hill manuscript is endorsed in Locke's hand (vertically in the left margin of fo. 2v): “S Parker of Toleration.” Immediately underneath this endorsement is another, but in pencil (“Mr Locke's Notes”), possibly written by an auctioneer or a dealer in manuscripts.

The Davie Collection contains a second manuscript with a connection to Locke: a “Draft of act of Parliament for regulation of Elections” in the hand of Locke's friend, the Whig lawyer John Freke (1652–1717).Footnote 140 The Wilson Library does not retain Preston Davie's records of acquisition, and the authors have not found a record of the manuscript's sale.Footnote 141 But similarities to other Locke manuscripts permit a conjectural identification of its provenance. The “Draft” for the regulation of elections is closely related to three manuscripts now held in the Somerset Heritage Centre; these manuscripts discuss the electoral process, date from c.1699, and derive from the activities of Locke's friend Edward Clarke (1650–1710) as an MP for Taunton (1690–1710).Footnote 142 The manuscripts are part of the Sanford papers: a collection formed by Clarke and his descendants, and purchased from the Sanford family of Nynehead, Somerset.Footnote 143 Edward Clarke's daughters, Anne (1683–c.1744) and Jane (1694–1732), married into the Sanford family: Anne to William Sanford (c.1685–1718) and Jane to William's younger brother Henry (fl. 1717). In 1829 the Clarke estate at Chipley was bequeathed to Edward Sanford (1794–1871), the great-great-grandson of Anne Clarke and William Sanford. The electoral manuscripts were deposited in the Somerset Record Office between 1936 and 1942.Footnote 144 The electoral manuscript in the Davie collection resembles the manuscripts in Somerset in handwriting, content and wording, and it is reasonable to conclude that it once formed part of the Sanford collection.Footnote 145

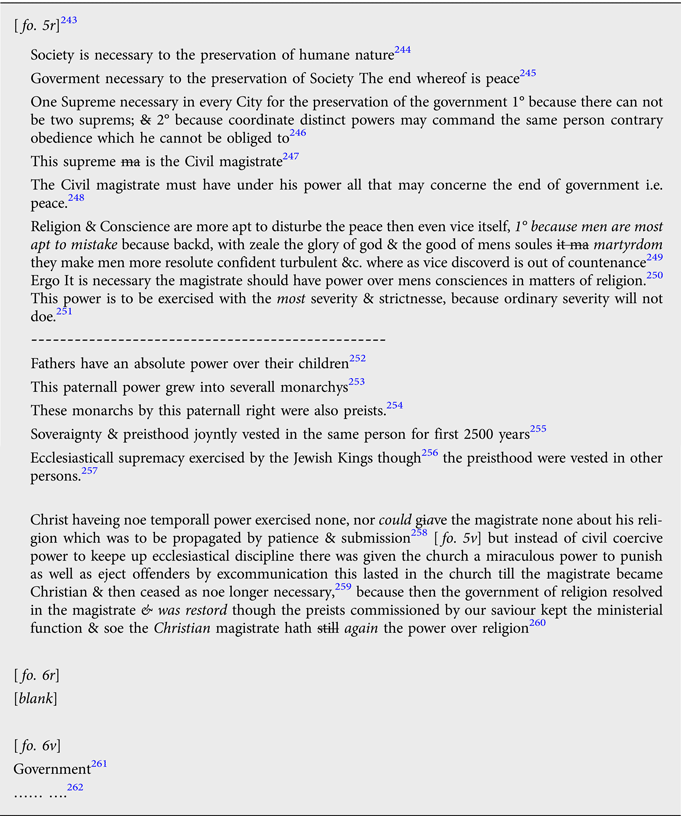

The provenance of the new manuscript on Parker's Discourse appears to share a Sanford connection. In content, as we have argued, the new manuscript and the Bodleian manuscripts must have constituted a single collection of notes, preparatory to a response against Parker. A physical description of the manuscripts strengthens this surmise. The Bodleian manuscripts are presented on three bifolia, each containing a separate set of notes, each discontinuous with the other. It is possible that these three bifolia were grouped together by Locke, but there is no clear evidence to suggest it. The first bifolium (fos. 5–6) was folded vertically down the middle to produce two columns, each leaf measuring 294 × 194 millimeters. The watermark for this paper is an arrangement of grapes on columns, most closely resembling COL.016.1 in the Gravell Watermark Archive,Footnote 146 and there is no visible countermark. It is a different type of paper, in other words, from the new manuscript. The text appears in the left-hand column of fo. 5r, and continues on the verso of fo. 5v for approximately one-quarter of the page. The rest of fo. 5 and all of fo. 6 are blank, excepting an endorsement “Government / 〈illegible〉” written vertically in pencil on the far right of fo. 6v, in a fairly modern hand, possibly dating from the early twentieth century, and probably supplied by an auctioneer or dealer. These notes present a paraphrase of Parker's account of the foundations of civil and ecclesiastical government in the first chapter of the Discourse. As this manuscript has no endorsement by Locke, we have designated it a title from the incipit (“Society is necessary …”) and assigned it the siglum O1.

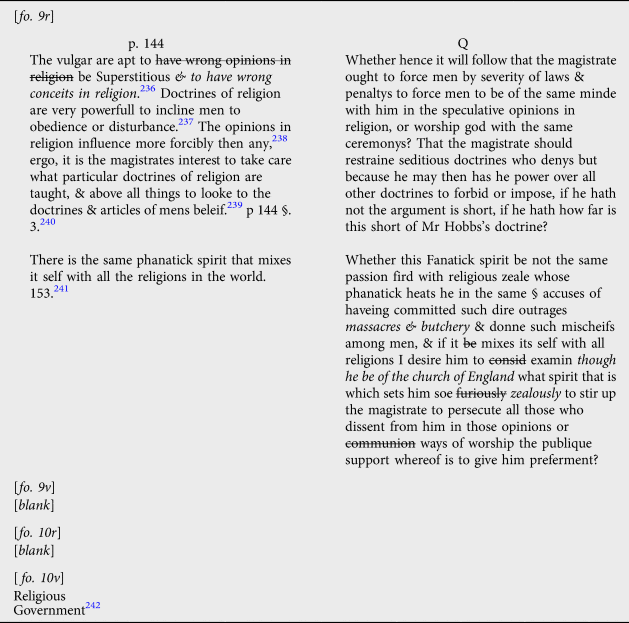

The second bilfolium (fos. 7–8) was folded vertically to produce a left-hand margin approximately one-quarter of the width of the page, each leaf measuring 230 × 172 millimeters. There is no visible countermark, but the watermark for this paper is the same as the new manuscript: closely resembling Heawood 2715. It is a different type of paper, in other words, from O1, but the same type of paper as the new manuscript. The text begins at the top of fo. 7r and continues onto fo. 7v, ending approximately one-quarter of the way down the page; fo. 8r is blank and fo. 8v is endorsed by Locke “Q〈uerie〉s On S. P〈arker〉s discourse / of toleration. 69.” These notes present a set of queries on Parker's Discourse, with references to the places that prompted Locke's queries in the margin. Locke's handwriting in this manuscript is somewhat freer than was typical, and there are a number of changes of ink as Locke's queries progress. We have designated it a title from the endorsement (“Qs On S.Ps discourse of toleration”) and assigned it the siglum O2.

The third bifolium (fos 9–10) was folded vertically down the middle to produce two columns, each leaf measuring 342 × 233 millimeters. The watermark for this paper is the same as the new manuscript and O2.Footnote 147 The left-hand column presents extracts from Parker, each with a page reference. The right-hand column is headed “Q,” and presents queries salient to the adjacent extracts. There are only two such queries at the top of fo. 9r, the rest of the document being blank, save an endorsement “Religious / Government” written vertically in pencil on the far right of fo. 10v, in a fairly modern hand, probably by the same auctioneer or dealer who endorsed O1. As this manuscript has no endorsement by Locke, we have designated it a title from the incipit (“The vulgar are apt …”) and assigned it the siglum O3.

Though these three bifolia are held in the Bodleian Library, they were not acquired from the Lovelace family with the bulk of the Library's Locke Collection in 1947.Footnote 148 The guardbook in which they are now preserved is an assortment of papers acquired or identified by the Bodleian Library between 1951 and 1957. The Parker manuscripts (O1–3) were purchased from Sotheby's on 15 March 1954.Footnote 149 The sale catalogue gives no indication of the provenance of the manuscripts, but previous Sotheby's sales provide a clue. Papers related to Locke and Clarke were consigned to Sotheby's by E. C. A. Sanford (1859–1923)—a member of the Sanford family—in (at least) three sales before his death: 1913, 1915 and 1922.Footnote 150 The 1922 sale contained a number of items on the subject of toleration: lots 866 and 867 consisted of Locke's autograph of the Essay Concerning Toleration, which is now preserved in the Huntington Library; lot 868 consisted of the Reasons for Tolerateing Papists Equally with Others, which is now preserved in the Greenfield Library at St John's College, Annapolis; and lot 871 consisted of the following miscellany: “LOCKE (J.) On the Clipping of Money, holograph MS, 2 pp. folio (Sept. 1694); An Essay concerning ‘Whigs and Torys,’ holograph MS, 1 3/4 pp. 4to; Two short Notes in his hand concerning Government; Notes concerning Toleration in another hand, 1¼ pp. 4to.”Footnote 151 Several circumstances suggest that the last three items are O1–3. First, it is clear that Clarke—and, subsequently, E. C. A. Sanford—owned manuscripts by Locke on the subject of toleration. Second, another manuscript from that sale, the Reasons for Tolerateing Papists Equally with Others, bears an endorsement in pencil (“Toleration”) in a hand that resembles the hand of the modern endorsement on O1 and O3. Finally, it is notable that both O1 and O3 bear endorsements with the word “Government,” and are relatively “short”; O2 bears an endorsement with the word “toleration” and its text is one and a quarter pages in length. The catalogue indicates that the last item is not in Locke's hand, but, as we have noted, Locke's handwriting was somewhat freer in O2. An inexpert auctioneer might have mistaken it for “another hand.” These concordances must indicate that the last three items in lot 871 were O1–3.Footnote 152 The latter therefore derived from the Sanford collection. Clarke's possession of three sets of manuscripts on the subject of toleration (Locke's Reasons, Locke's Essay, and O1–3) could point to a purposive act of acquisition on his part, but it is nonetheless probable that the manuscripts were deposited by Locke somewhat indiscriminately, as part of the “many papers” that he sent to Clarke in August 1683, before his departure into exile. Clarke ex hypothesi would have retained the manuscripts after Locke's return to England in February 1689.Footnote 153

We have designated the Chapel Hill manuscript a title from the endorsement (“S Parker of Toleration”) and assigned it the siglum C. C has a number of characteristics in common with O1–3, aside from sharing the same subject. O2, O3, and C appear to have the same watermark and might have derived from the same stock of paper. It is a reasonable conclusion that C and O1–3 share a provenance, and that all four manuscripts came from the Sanford collection. This hypothesis is somewhat supported by the fact that C is endorsed in pencil (“Mr Locke's Notes”) in a hand resembling the endorsing hand in O1, O3, and the Reasons. This must suggest that the four manuscripts passed through the same chain of custody at some point, possibly as part of their shared consignment for sale. That the “Draft of an act of Parliament for regulation of Elections” mentioned above almost certainly derives from the Sanford collection lends circumstantial support to the conclusion that C was purchased with the “Draft” by Davie en bloc from the Sanford family, its representatives, or a dealer in manuscripts.Footnote 154

We cannot assume that the current dispersal of these manuscripts is anything more than an accident of transmission. There is no basis to assume that O1–3 should be considered as a single unit, or that they were grouped by Locke in a specific order, or deliberately to exclude C. C examines the preface and first 158 pages of Parker's Discourse, making it significantly longer and more comprehensive than O2 and O3. O2 examines pages 11–29 and O3 examines pages 144–53. Moreover, there is no clear reason why Locke ceased taking notes at page 158 of Parker's work, in the middle of Chapter 4. The Discourse comprised eight chapters and the subject matter did not drastically change in the latter half of the book. There are changes of ink in both C and O2, but there is no clear evidence that Locke was making notes on both manuscripts at the same time, using the same implement. This would indicate that Locke set aside his work on the Discourse, which in turn suggests that he made the notes in C, O2, and O3 at roughly the same time, perhaps taking a new sheet for O2 and O3 to make notes when his more comprehensive notes (C) were not ready to hand. O1—written on a different type of paper—presents neither notes nor queries, but rather paraphrases the first chapter of the Discourse (pages 1–64). It might have been written before O2–3 and C, as a first attempt to summarize Parker's arguments, or it might have been written after O2–3 and C, as a preparatory sketch for a longer confutation. Our inclination is to favour the former possibility: Locke began a paraphrase, returned to make notes in more detail, and then set the entire project aside. But this reconstruction should be considered no more than a plausible hypothesis. In the transcription below, the manuscripts will be presented together for the first time, and in the following order:

-

C “S Parker of Toleration” (Southern Historical Collection, 03046, Folder 323).

-

O2 “Qs On S.Ps discourse of toleration” (MS Locke c. 39, fos. 7–8).

-

O3 “The vulgar are apt …” (MS Locke c. 39, fos. 9–10).

-

O1 “Society is necessary…” (MS Locke c. 39, fos. 5–6).Footnote 155

IV

Editorial conventions

Manuscript forms for words such as “ye,” “yt,” “yu,” “yr,” “wch,” “wt,” “spt,” and “agt” have been replaced by the usual printed forms, as have suffixes such as “–mt:” [–ment] and “–cōn” [–tion]. Contractions and abbreviations such as “K” [King], “Bps” [Bishops], “X” and “Xt” [Christ], “Xan” [Christian], “Xanity” [Christianity], “Sts” [Saints], “nāāl” [natural], “meū” [meum] and “ib” [ibidem] have been silently expanded. Locke's “i.e” has been rendered as “i.e.”. Citations of Parker have only been provided in those instances where Locke's citations are missing, incomplete, or erroneous. C, O3, and O1 typically provide Locke's paraphrase of Parker's text, rendering the presentation of Parker's own text otiose. In O2, and in some instances in C, quotations from Parker have been provided to contextualize Locke's comments. O1, O2, and O3 each present material also covered in C. In addition, O2 and O1 also overlap to a certain extent. Cross-references between each of the manuscripts have been provided where appropriate. These references use the siglum of the manuscript, the column in which the reference appears (in the case of C), the page number Locke cited (if any), and the folio on which the reference appears (since there is no duplication of folio numbers amongst the manuscripts, there is no need to cite the full shelfmark to distinguish them).

Editorial signs

-

italics scribal addition

-

word scribal deletion

-

mbad scribal cancellation by superimposition of correction

-

a () the letter “a” is conjectural; the next is indecipherable

-

〈 〉 editorial insertion or substitution in a text

-

{ } editorial excision

Transcriptions

C—“S Parker of Toleration”

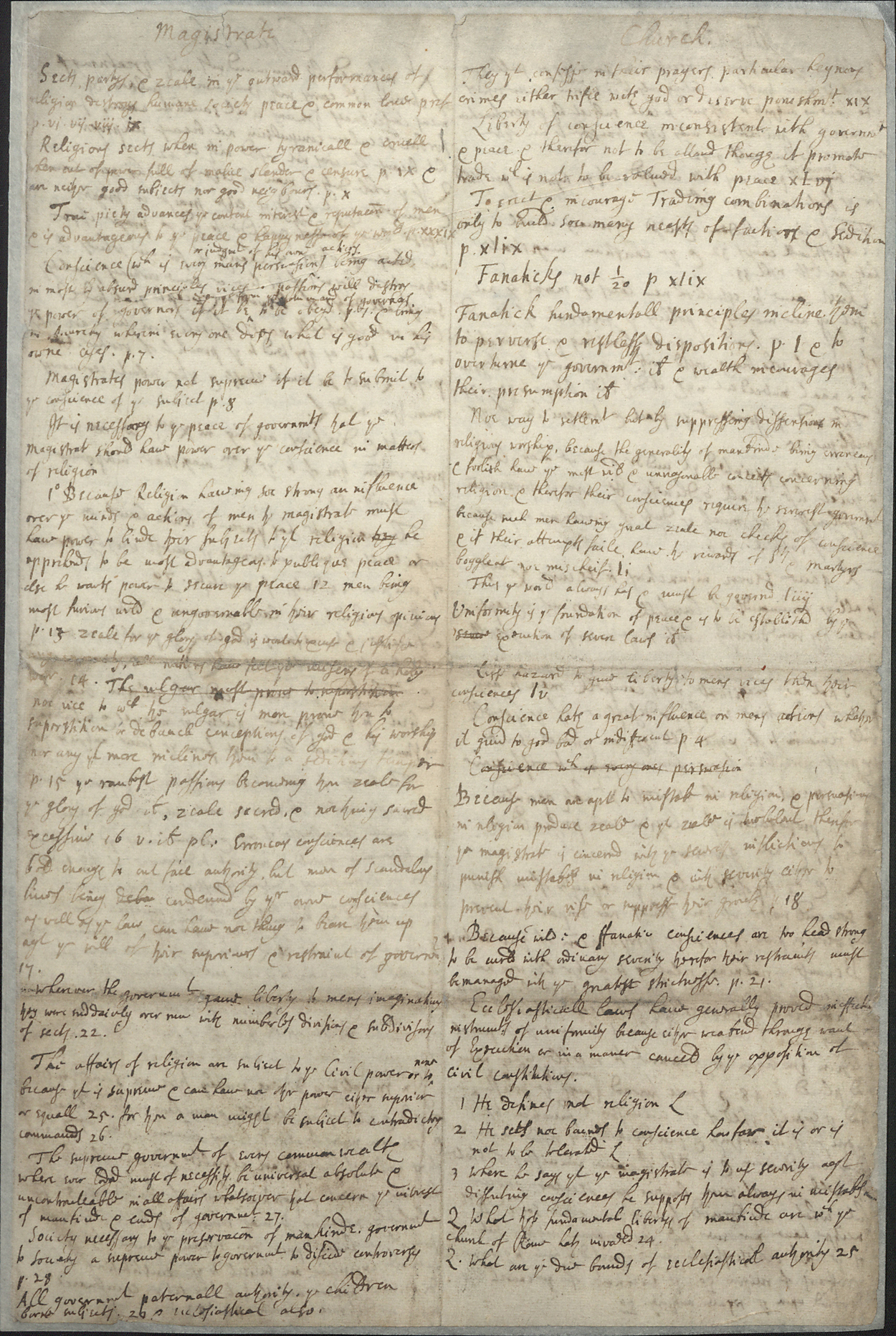

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, Southern Historical Collection, 03406 (Folder 323). A series of notes with occasional queries on Samuel Parker's A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie in Locke's hand.

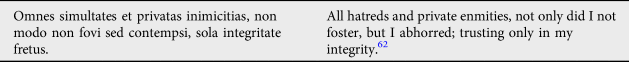

O2—“Qs On S.Ps discourse of toleration”

Bodleian Library, MS Locke c. 39, fos. 7–8. A series of queries on Samuel Parker's A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie in Locke's hand.

O3—“The vulgar are apt…”

Bodleian Library, MS Locke c. 39, fos 9–10. A pair of queries on Samuel Parker's A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie in Locke's hand.

O1—“Society is necessary …”

Bodleian Library, MS Locke c. 39, fos 5–6. A paraphrase of the first chapter of Samuel Parker's A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie in Locke's hand.

Acknowledgment

The manuscript printed in this article was discovered by J. C. Walmsley. The article is a collaboration of the authors, who are grateful for the help provided by Jeffrey Collins, Mark Goldie, Christine Jackson-Holzberg, Duncan Kelly, J. R. Milton, Jacqueline Rose, the Somerset Heritage Centre, and the referees for Modern Intellectual History. The authors are additionally grateful to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for access to the manuscript material presented above and permission to reproduce images of manuscript material in its possession.