Introduction

In the last decade, social media have superseded the functions and roles of traditional media as a tool for framing political issues and making audiences for political causes. In particular, Twitter and other participatory online platforms have become tools for states and state actors to boost their images and galvanize support from their perceived voter bases and/or audiences. On social media platforms, populist leaders generally appeal to direct mechanisms of governance through narratives, leitmotifs, and strategic metaphors embedded in political language to reveal specific discourses and agendas that shape the collective rationality of the public (see Korkut et al. Reference Korkut, Mahendran, Bucken-Knapp and Cox2015; Korkut and Eslen-Ziya Reference Korkut and Eslen-Ziya2016; Ozduzen and Korkut Reference Ozduzen and Korkut2020; Şahin et al. Reference Şahin, Johnson and Korkut2021). Authoritarian governments that privilege internal control and authority are concerned with establishing control within national jurisdictions (see Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2020). Despite recent controversies on Twitter, it continues to be a popular tool for state actors. Using Twitter, state actors perform nationalist populism (see Rothschild and Shafranek Reference Rothschild and Shafranek2017; Shahin and Huang Reference Shahin and Huang2019; Yesil Reference Yesil2020), and at times engage in information operations and warfare (Burns and Eltham Reference Burns, Eltham, Papandrea and Armstrong2009), to control and exert influence (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2020).

More than ever before, contemporary political leaders use social media platforms, particularly Twitter, in their daily governance and diplomatic practices (see Collins et al. Reference Collins, DeWitt and LeFebvre2019; Duncombe Reference Duncombe2017), which Šimunjak and Caliandro (Reference Šimunjak and Caliandro2019) name as “Twiplomacy.” Embracing a novel perspective on digital governance, Pamment (Reference Pamment2016) associates transmedia storytelling and participatory cultures with surveillance in diplomatic campaigning, as this sort of storytelling performs a disciplining role for stakeholders. Although digital storytelling can have bottom-up empowering roles for ordinary users (see Burgess Reference Burgess2006; Couldry Reference Couldry2008), authoritarian politicians also create stories and present themselves online, which generally relates to surveillance and the leaders’ aims to create polarization and heightened emotional response, especially in populist and/or authoritarian contexts.

Existing research has studied the populist communication of political leaders such as former US President Donald Trump (see Bucy et al. Reference Bucy, Foley, Lukito, Doroshenko, Shah, Pevehouse and Wells2020; Shahin and Huang Reference Shahin and Huang2019; Šimunjak and Caliandro Reference Šimunjak and Caliandro2019) and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi (see Pal Reference Pal2015; Rodrigues and Niemann Reference Rodrigues and Niemann2019). Bucy et al. (Reference Bucy, Foley, Lukito, Doroshenko, Shah, Pevehouse and Wells2020) showed how during the 2016 electoral campaign, Trump’s brashness on social media provoked a heightened response from viewers, compared with his rival Hillary Clinton’s more measured approach. While some of this previous research on populist communication has focused on individual leaders’ online relationships with their perceived audiences from a comparative perspective, other research has looked at the specific online strategies of leaders through their profiles on social media platforms. Largely shunning the mainstream media, Rodrigues and Niemann (Reference Rodrigues and Niemann2019) show how Modi uses his social media accounts to communicate with the nation, keep followers informed of his day-to-day engagements and government policies, and more specifically engage with young, educated, middle-class voters in India. Sinha (Reference Sinha2017, 4167) identifies Modi’s love for social media as part of his political makeover and a crucial component of his attempted techno-populist project, which aims to constitute him as a man that is ahead of the times. Similar to Trump’s bold and aggressive use of Twitter as a strategy for identity and audience-making, Modi aims to reach a specific group and uses social media platforms effectively for nation-branding and his own personal branding within his political project.

Previous research on the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi; AKP) Twitter governance has similarly shown the emergence of a cult of personality around President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (see Yesil Reference Yesil2020), as well as political trolling (see Bulut and Yörük Reference Bulut and Yörük2017; Saka Reference Saka2018; Uysal and Schroeder Reference Uysal and Schroeder2019). These studies looked at the general authoritarian tendencies in the online communication of the AKP regime, such as their use of paid political trolls. Şahin (Reference Şahin2021) shows how the AKP as a populist party used the Kurdish question to trigger perceptions of ontological insecurity, enabling it to securitize the elections in November 2015. In this article, we explore the period before the peace processFootnote 1 came to an effective end in the summer of 2015 and investigate the AKP’s political leaders’ social media rhetoric during and shortly after the peace process to understand the power shift and the mediation of this crucial political problem in this period. In doing so, we contribute to the existing literature on the populist online communication of right-wing populist leaders by looking at the role of the social media platform Twitter under the authoritarian rule of Erdoğan (and the AKP more broadly) during the peace process.

In this article, we define populism as a political style or a repertoire of discourse and performance, rather than an ideology (see DeHanas and Shterin Reference DeHanas and Shterin2018; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016). More specifically, we identify populism as a political communication style in the construction of power and identity (Block and Negrine Reference Block and Negrine2017; Laclau Reference Laclau2007), where we focus on the unique contribution of communication processes to construct and seed populist ideas (De Vreese et al. Reference De Vreese, Esser, Aalberg, Reinemann and Stanyer2018). We observe that populism as a political style is consistent across the political speeches of key actors of AKP in their management and negotiation of the peace process online. While previous research has conceptualized the motives and aims of populist communication, scholarship has also investigated the populist actors or messengers of populist communication (see Aalberg et al. Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and De Vreese2017; Engesser et al. Reference Engesser, Fawzi and Larsson2017). In the digital era, the message delivered/shared becomes viral and populistically effective if it is direct, unmediated, outrageous, polarizing, shocking, and emotional (Gil de Zúñiga et al. Reference Gil de Zúñiga, Koc Michalska and Römmele2020). With this background, this article studies the communicative self-presentation of populist communication of the AKP’s prominent political actors on the most contentious issue in Turkey over the past few decades: the peace process between Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan; PKK) (Ernst et al. Reference Ernst, Blassnig, Engesser, Büchel and Esser2019).

The peace process between 2013 and 2015 was the first official “peace” attempt in the history of modern Turkey, and eventually failed. Within the growing literature on the Turkish state’s failed peace process with the PKK, one can find analyses of the aims and motivations behind the AKP’s “democratization attempts” (Günay and Yörük Reference Günay and Yörük2019; Jongerden Reference Jongerden2019; Kaya and Whiting Reference Kaya and Whiting2019), as well as discussions of the causes of disagreement in the fall out between the AKP and the PKK (Baser and Ozerdem Reference Baser and Ozerdem2021; Tekdemir Reference Tekdemir2016; Toktamış Reference Toktamış2019). Although limited, some studies discuss the impact of the Rojava experience Footnote 2 in Northern Syria on Turkey’s peace process with the PKK (Çiçek Reference Çiçek2018; Özpek Reference Özpek2017; Savran Reference Savran2020; Weiss Reference Weiss2016). Our article contributes to this literature by carrying out a rhetorical analysis of the failed peace process. We focus on four key AKP actors – Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (prime minister until 2014, and president since then), Ahmet Davutoğlu (prime minister following Erdoğan’s election as president), Yalçın Akdoğan (deputy prime minister under Davutoğlu), and Efkan Ala (minister of interior affairs) – and their populist Twitter framing of the peace process and the changes in the rhetoric concerning the resolution of Turkey’s Kurdish question. By doing so, we reveal the shifting online narrative of the AKP’s key actors in the peace process between 2012 and 2015.

Our argument in this article is threefold. First, we show that AKP actors persistently label the Kurdish political movement in Turkey and in Syria Footnote 3 as a threat to the national security of Turkey, reflected in their online rhetoric toward the remilitarization and resecuritization of Turkey’s Kurdish question within and across its borders. Second, we argue that the AKP uses the peace process and various persuasive and performative communicative techniques not only to consolidate Kurds’ electoral support but also to reach its aim to remove the Kemalist military–bureaucratic tutelage in Turkey (see Akkaya Reference Akkaya2020; Özpek Reference Özpek2019; Polat Reference Polat2016) and replace it with the hyper-presidentialism of Erdoğan. Third, we argue that the intensification of Erdoğan’s one-man rule has been reflected in the AKP’s branding itself using social media platforms as the only viable alternative for the region’s stability, which has blocked more constructive dialogue toward a peaceful resolution to the Kurdish question.

The rest of the article follows with a brief chronology of the intermittent peace process (2009–2015) between Turkey (the ruling AKP and the Turkish National Intelligence Organization [Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı; MİT]) and the PKK, delegated by the Peace and Democracy Party (Barış ve Demokrasi Partisi; BDP) and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi; HDP). We then briefly explain our methodological framework and present the findings of the interpretative rhetorical analysis of data collected from social media.

The AKP’s intermittent peace process with the PKK

The talks between the PKK and the Turkish state during the AKP period date back to 2005, when Erdoğan accepted a former Norwegian prime minister’s offer to “take the initiative to solve the problems between the Kurdish movement and Turkey” (Dicle Reference Dicle2017, 26). At the end of 2005, an institution in Geneva started another initiative that evolved into the Oslo Talks in subsequent years. These talks did not lead to any solid results and the conflict re-escalated in the aftermath of the general elections in 2011. Following Abdullah Öcalan’s call to stop hunger strikes going on in prisons at the time, dialogue and peace talks between the AKP and the PKK started once again in 2012.

Various symbolic events took place between 2013 and 2015, such as a reading of Öcalan’s letter during the Newroz celebrations in Diyarbakır in 2013 and the establishment of the Wise People Commission. Despite their “positive impact on shifting the perceptions on the Kurdish issue from a national security problem to an issue of rights and freedoms,” the AKP failed to take concrete steps to establish democratic reforms and was often criticized for handling the process outside the scope of the law (Hakyemez Reference Hakyemez2017, 6). Furthermore, the AKP has been criticized for instrumentalizing the peace process to consolidate its power and “conquer” the state (Jongerden Reference Jongerden2019, 270). Günay and Yörük (Reference Günay and Yörük2019, 15) relate the peace process to the power play and political hegemony of the AKP while pointing out its location within the AKP’s political Islamist ideology and its pragmatic aims to appeal to Kurdish voters, as the Kurds represent a critical electoral bloc in the country.

From the beginning of the peace process, Turkey underlined that it would not allow a de facto Kurdish administration led by the Democratic Union Party (Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat; PYD), viewed as a sister organization to the PKK (Çiçek Reference Çiçek2018, 187). Previous research identifies how the AKP government and the Turkish state feared that the successes of the Rojava experience and the People’s Protection Units (Yekîneyên Parastina Gel; YPG) in the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and how a Kurdish-dominated territory along its southern border would imply the formation of a similar region in Turkey (Baser and Ozerdem Reference Baser and Ozerdem2021; Gunter Reference Gunter2016). Despite the international attention and sympathy that the YPG and YPJ (Women’s Protection Units, Yekîneyên Parastina Jin; YPJ) received for their resistance against ISIS in Kobani (Ayn al-Arab) – which borders the Suruç district in Turkey’s Urfa province – Turkey remained indifferent and uncooperative. Soon after Kobani had been liberated from ISIS by the YPG/YPJ forces on January 26, 2015, the AKP government initiated a dialogue with the PYD (Dicle Reference Dicle2017, 191). However, as the existing literature highlights, the AKP expected the collapse of the democratic autonomy model in Rojava so that it would get the upper hand on the negotiation table with the PKK (Dicle Reference Dicle2017; Özpek Reference Özpek2017; Savran Reference Savran2020; Weiss Reference Weiss2016). Arguably, the continuation of the peace process would be possible only if the strategic interests of the negotiating leaders continued to overlap, but the PKK did not abandon the novel success and support it gained in Rojava, which made Rojava an existential threat in the eyes of the AKP government and the Turkish state. As the chances of the Rojava experience in Syria turning into a proto-Kurdish state increased, so did Erdoğan’s “tendency to deal with the legal Kurdish opposition (HDP) in a manifestly heavy-handed and repressive manner” (Weiss Reference Weiss2016, 585).

Despite these national and transnational setbacks, there was a series of talks between the PKK and Turkey, leading to the Dolmabahçe AgreementFootnote 4 in February 2015. The agreement, first cheered by Erdoğan and AKP circles, was soon denounced. An internal security package was later passed by the Turkish Parliament in 2015, which signaled the AKP’s plan to remilitarize the Kurdish question, instead of peaceful dialogue. Concurrently, Erdoğan’s discourse shifted back to the denial of a Kurdish issue. In a meeting held with neighborhood heads (mukhtars) in March 2015, Erdoğan said: “When the state acknowledged the [Kurdish people’s] problems and started efforts to resolve them, the concept of Kurdish problem lost its validity” (Presidency of the Turkish Republic 2015).

Political tensions between the AKP and the HDP continued to escalate in the pre-general election period in the spring of 2015. Its loss of its parliamentary majority on the June 7, 2015 elections due to the HDP’s unprecedented electoral success was a deal-breaker for the AKP, a party that was arguably never “really willing and ready to transform the ethno-national hierarchies that favor Turks” (Ercan Reference Ercan2013, 121; Ercan Reference Ercan2019). The peace process effectively came to an end in July 2015, and urban warfare between the PKK and Turkey began in various Kurdish cities in Turkey. The urban warfare continued for eight months, between August 2015 and March 2016, leading to the death of thousands of people (including several hundred civilians), the internal displacement of thousands, and the destruction of Kurdish cities (International Crisis Group 2016). The collective violence against Kurds in the post-peace process was also visible in other parts of Turkey via nationalist demonstrations against the PKK, which also indirectly targeted the HDP as well as the Kurdish people (Günay Reference Günay2019). The re-escalated conflict, added to the coup attempt against the AKP government on July 15, 2016, also led to increased oppression of the opposition in Turkey, including restrictions on freedom of expression in politics, media platforms, and academia. Since then, Turkey has carried out three military operations in northern Syria: Operation Euphrates Shield (August 2016), Operation Olive Branch (January 2018), and Operation Peace Spring (October 2019) with questionable legitimacy under international law (Stockholm Center for Freedom 2020).

Methods and the methodological perspective on Twitter analysis

Politicians still mainly use Twitter on a global scale as a unidirectional way of disseminating information, where they can communicate directly with citizens as well as monitor public opinion without having to overcome the gatekeeping functions of legacy media (Rauchfleisch and Metag Reference Rauchfleisch and Metag2016). While politicians have also used Instagram effectively for their visual communication with the public in recent years, Twitter remains the most popular text-based platform on which politicians are (and expected to be) active (Tromble Reference Tromble2018). To capture the shifts in the AKP’s four key actors’ political narratives and performance on Kurdish politics during the peace process, we used Twitter communication on the issue as a case study.

Our analysis concentrates on the populist online political speech of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Ahmet Davutoğlu, Yalçın Akdoğan, and Efkan Ala. The main reason why we focus on the profile data of the AKP government’s main actors but not the official or institutional (e.g. Presidency or Prime Ministry) Twitter accounts of the AKP is because of the personality cult around Erdoğan, which is not only related to the wider regime that combines elements of electoral authoritarianism, neopatrimonialism, Islamism, and populism (Yılmaz and Bashirov 2018), but also Erdoğan’s one-man rule within the AKP. Today, right-wing populist and far-right “celebrity” politicians are instigators of social, political, and economic forces, rather than being just reflections of them (Zeglen and Ewen Reference Zeglen and Ewen2020, 271–272). Erdoğan has been, and continues to be, the perceived oracle on the key political issues that determine the future of Turkey, the Kurdish question being one of these. Along with Erdoğan’s Twitter communication, other actors such as Davutoğlu, Akdoğan, and Ala were the “appointed” agents of the peace process, determined by Erdoğan himself. Therefore, instead of looking at the institutional accounts, we focus on these four key actors and their “personal” online communication rhetoric and patterns throughout the peace process.

Our research rests on publicly available data collected from public accounts of well-known politicians. As two native Turkish-speaking authors, we translated the tweets from Turkish to English. Although Twitter data is public, users’ social media contents cannot be directly quoted or cited for research purposes.Footnote 5 Translation from another language thus helped us to “fabricate” the data in the sense that it helped individual posts not to be directly identified and found through a simple search on search engines (Markham Reference Markham2012).

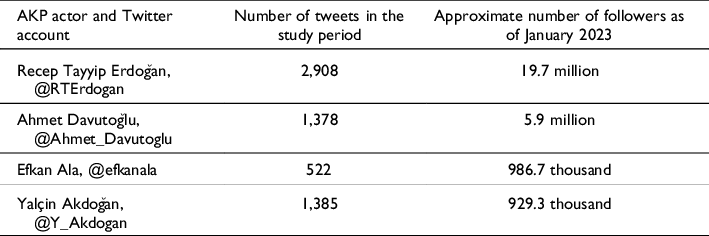

To study the categories and rhetoric in the AKP’s important political actors’ online statements targeted at domestic, Turkish-speaking members of the public during the peace process, we harnessed 6,195 tweets from Erdoğan, Davutoğlu, Ala, and Akdoğan’s official Twitter profiles between July 1, 2012 and November 1, 2015 (see Table 1). Our data collection starts in July 2012, when the Rojava cantons declared de facto autonomy in North-Eastern Syria. We end the data collection in November 2015, Footnote 6 when the peace process with the Kurds in Turkey had already ended, and snap elections took place in Turkey with which the AKP regained a majority in parliament.

Table 1. The AKP’s four key actors’ Twitter profiles and the number of followers and tweets shared in the study period

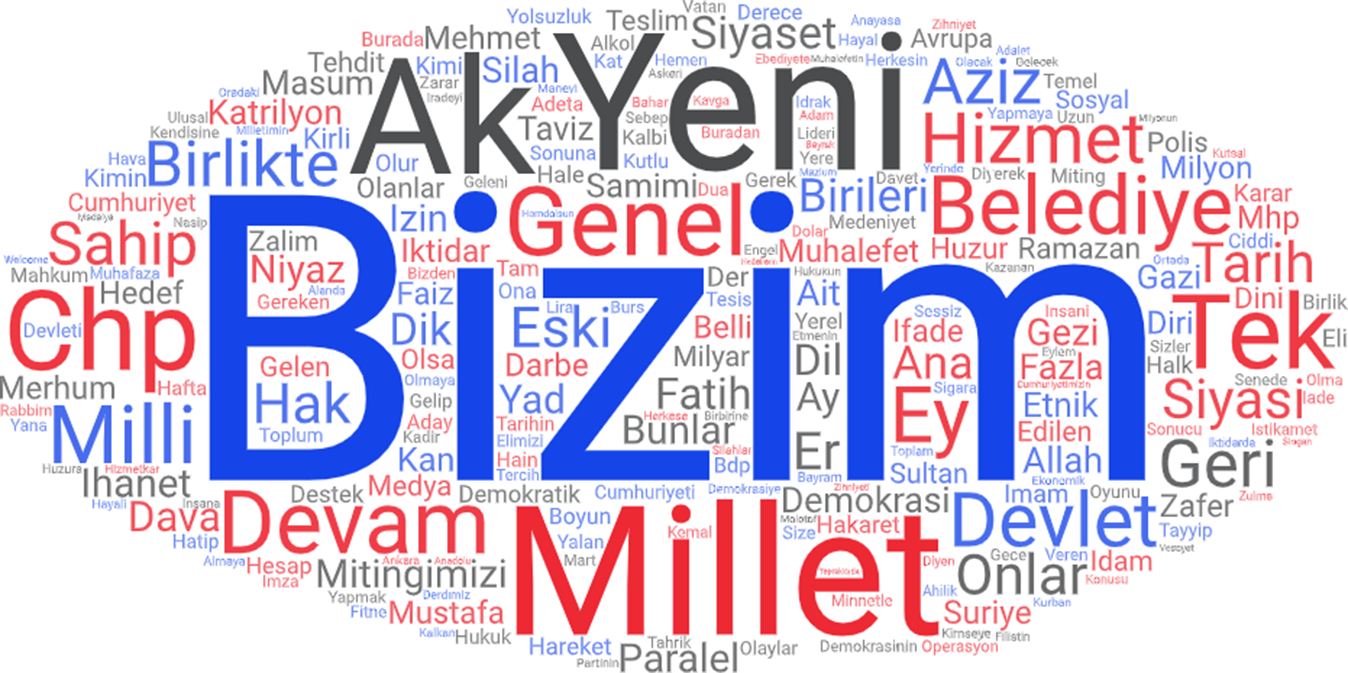

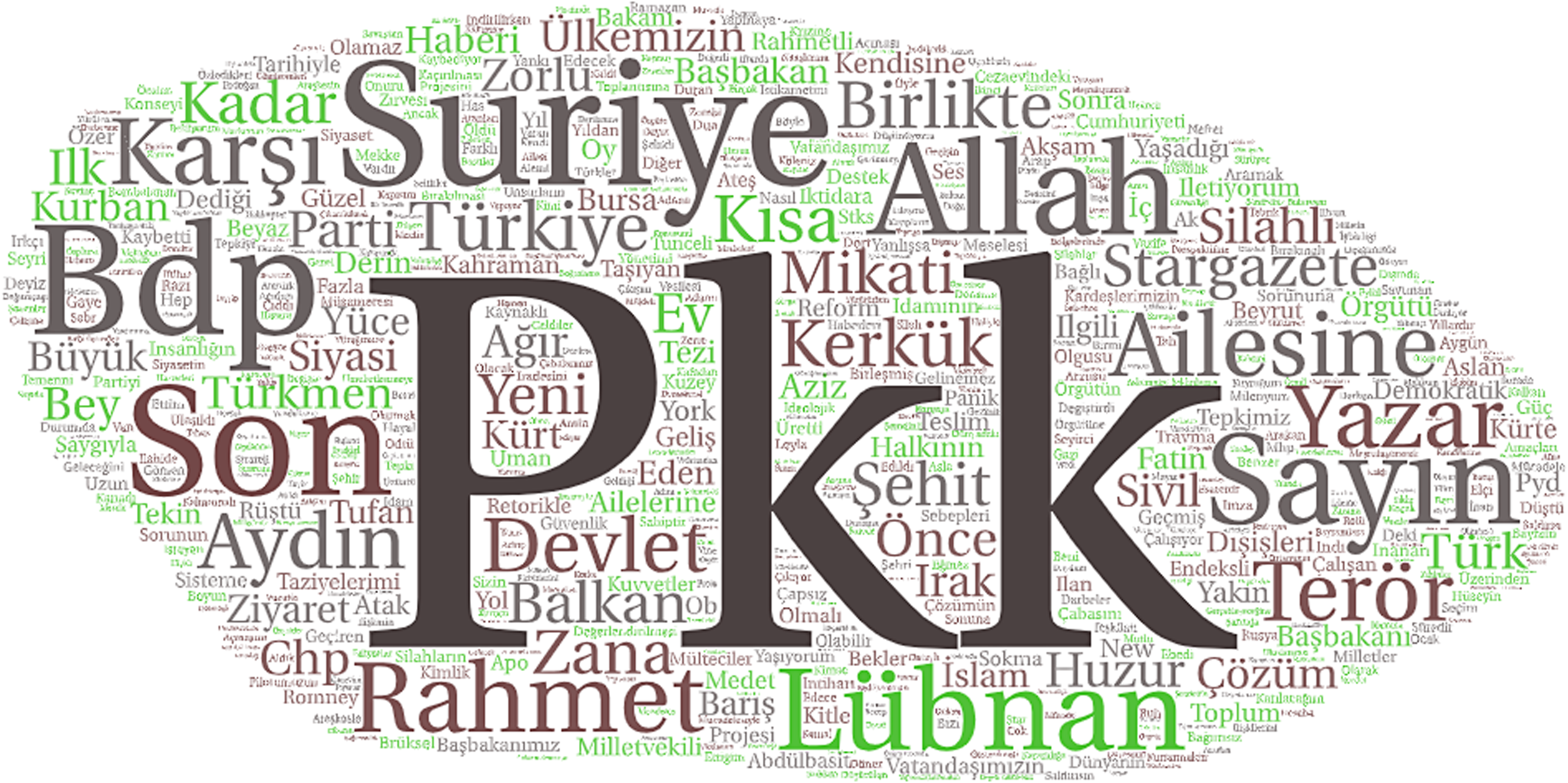

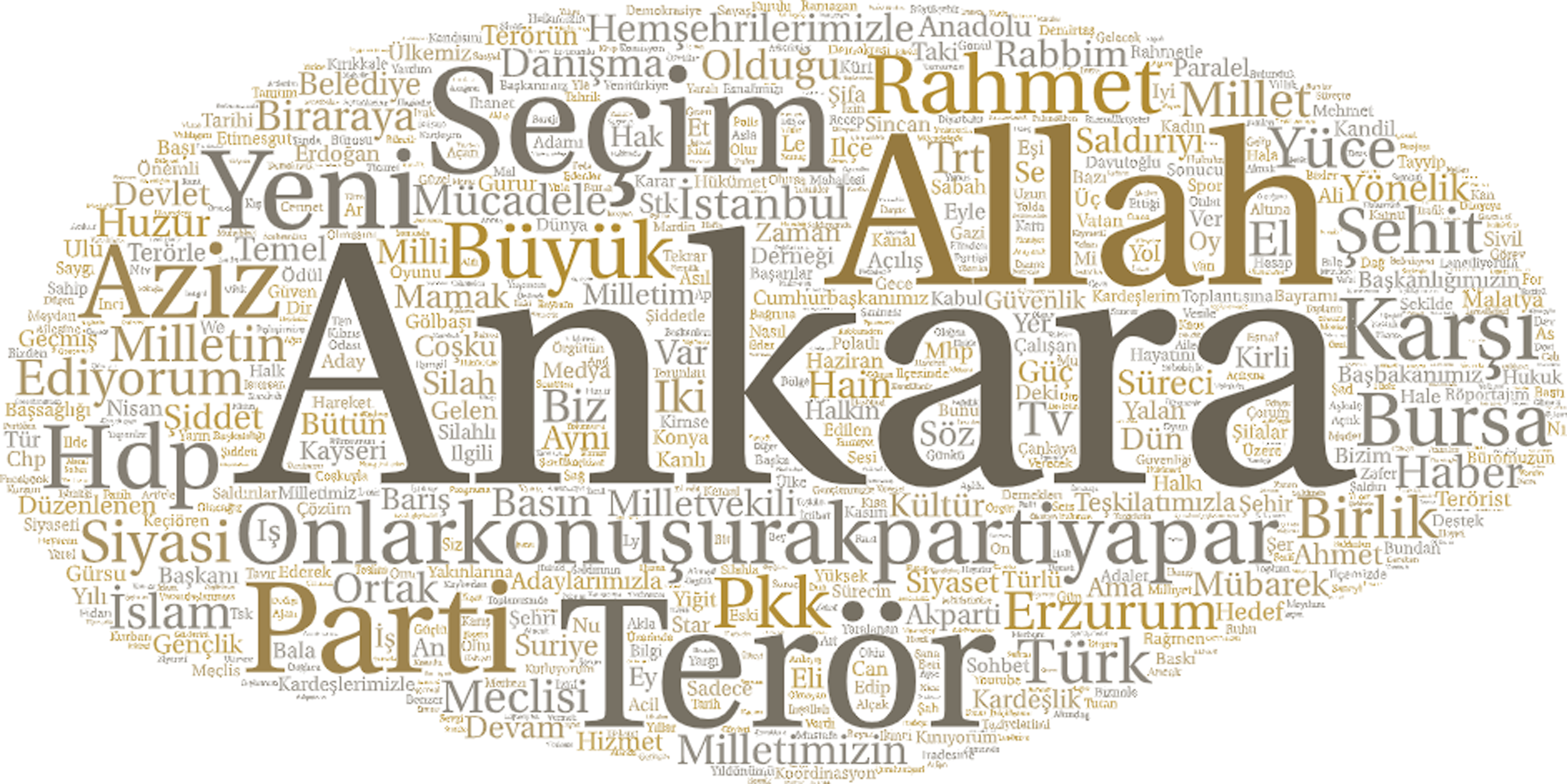

To collect the social media data, we used the software Mozdeh and the programming language Python to time-stamp the actors’ profile data for the duration of the peace process. We used Excel to first clean the data and remove duplicates. We only removed the duplicates but did not omit any tweets. We then used WordArt (https://wordart.com/) to create word clouds from the Twitter profile data of Erdoğan and the other three actors between 2012 and 2015. Word clouds are a straightforward and visually appealing data visualization method for text and are used in various contexts to provide an overview by distilling text down to the words that appear with the highest frequency (Heimerl et al. Reference Heimerl, Lohmann, Lange and Ertl2014). The word clouds show the most used words, excluding the stop words, to help us detect evolving trends in the political speech of these key political actors in this period.

Rhetorical political analysis extends the “rationalities” on which politics is based into areas that involve the affective, the traditional, the figurative, and the poetic (Finlayson Reference Finlayson2007, 560). This requires an examination of the multiple influences on styles and strategies of the political argument. We use rhetorical analysis to examine how “techniques of persuasion operate in political life and how argumentative strategies are employed to shape political judgements” (Martin Reference Martin2013, 1–2) and to decipher multiple styles and strategies within the individual tweets of the four AKP actors in their aims to make the nation, brand their political image, and appeal to different voters using online platforms.

Our analysis follows a macro-to-micro path, which is mutually supportive: from an analysis of the yearly most used words in the overall profiles, we move toward an examination of the keyword-specific posts of these actors. We first analyze the overall tweets using word clouds to study the patterns in the tweets of these actors in this period. We then individually identify important keywords to study the peace process and rhetorically analyze how these leaders appealed to their audiences on this issue.

The AKP’s online message during the Turkey–PKK peace process

Social media created a convenient arena for the top-down regulatory governmental rhetoric aiming to construct fear and paranoia among their perceived audiences and blame others for threatening or damaging “our” society (Wodak Reference Wodak2015, 1). The four AKP actors have effectively used Twitter for praising their role in bringing peace to Turkey while labeling the Kurdish political actors as “terrorists.” In what follows, we first present the macroanalysis, which reveals the right-wing populist approach of Erdoğan and the three other AKP actors’ tweets. Then we move on to the microanalysis where we focus specifically on these actors’ reference to the peace process and the Kurdish question in Turkey as well as Syria.

An analysis of Twitter posts from a macro perspective: populist nationalism

Right-wing populist leaders and political parties typically appeal to notions such as the “heartland” or imagined home of the imagined community that is “the people.” The heartland represents “the good old days,” a romanticized time in national history when the people were much better off (see Cromby Reference Cromby2019; Mudde Reference Mudde, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017). National myths play into such depictions of the heartland, which often exclude ethnic or racial minorities from the category of “the people” (Mudde Reference Mudde, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017).

The most used words in Erdoğan’s overall tweets between 2012 and 2015 are “ours” (bizim), “new” (yeni), “only” (tek), “nation” (millet), “state” (devlet), and “treason” (ihanet) (see Figure 1), which sums up his normalization of the exclusionary practices of the state and the shaping of the stratification structure of the state in this period (Rosenhek Reference Rosenhek1999). These common expressions in Erdoğan’s tweets account for his polarizing politics, which has been analyzed as a strategy of the new regime in consolidating fear and surveillance of various dissident communities (see, for instance, Borsuk et al. Reference Borsuk, Dinc, Kavak and Sayan2022; Bulut and Yörük Reference Bulut and Yörük2017; Ozduzen Reference Ozduzen2021), especially the Kurds.

Figure 1. Overall word cloud of Erdoğan’s tweets between 2012 and 2015.

From a closer perspective, the 2012 social media data collected from Erdoğan, Davutoğlu, Ala, and Akdoğan’s Twitter profiles (see Figures 2 and 3) shows that the main difference is the centrality of the words “PKK,” “BDP,” and “Syria” in the latter three AKP actors’ tweets. In addition to “ours” (bizim), “us” (biz), “big” (büyük), “CHP,” and “AK Party,” the most used word is “terror” (terör) in Erdoğan’s tweets in 2012, referring in general to the clashes between the Turkish state and the PKK. While Davutoğlu, Ala, and Akdoğan’s accounts target the pro-Kurdish party, the BDP, Erdoğan more visibly targets the main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi; CHP).

Figure 2. Word cloud of Erdoğan’s tweets in 2012.

Figure 3. Word cloud of the other AKP actors’ (Davutoğlu, Akdoğan, and Ala’s) tweets in 2012.

In the tweet samples of all the actors, “Allah” remains one of the most used words in 2012, which is a consistent trend across data collected in different periods. This accounts for the new phase in the imposition of a new form of Turkishness, an Islamized version of national identity (Lüküslü Reference Lüküslü2016, 638–645), which instills fear for minoritized communities in Turkey and fosters polarization in society. Populist majoritarianism in favor of a religious conservative narrative of Turkish history and view of Turkish society dominated the online discourse of the key actors (see DeHanas and Shterin Reference DeHanas and Shterin2018; Grigoriadis Reference Grigoriadis2017). In the eyes of Turkey’s Islamists, the policies of oppression and assimilation toward the Kurds in the Republican past were resulting from Kemalist nationalism and its national and racial formation of the Turkish state (Günay Reference Günay2013).

Some argue that with this approach, the AKP intended to form a “Kurdish–Turkish peace agreement in Turkey [that] would have convinced the Muslim population in Turkey and worldwide that the AKP could unite Muslims of various nations” (Günay and Yörük Reference Günay and Yörük2019, 15). This was reflected in the sharing imagination of a “united we” under the symbols and characteristics of Islam, which was shared by the AKP actors.

The exclusive nature of being a citizen in the AKP’s Turkey persisted in 2013, evidenced by the use of “us” (biz) the most (see Figures 4 and 5), which was followed by the “nation” (millet), “ours” (bizim), and “AK Party.” Different from his online political speech in 2012, Erdoğan’s political speech revolved around an additional “Syria” (Suriye) in 2013, which is even more evident in tweets of the other three main actors of AKP at the time. Egypt is the most used word in the political speech of these actors in 2013, followed by Syria (see Figure 5). As the tweets of these actors in this period show, Turkey increasingly aimed at becoming the hegemonic power in the Middle East.

Figure 4. Word cloud of Erdoğan’s tweets in 2013.

Figure 5. Word cloud of the other AKP actors’ (Davutoğlu, Akdoğan, and Ala’s) tweets in 2013.

Consistent with 2013, Erdoğan’s tweets in 2014 reinforce the idea of an exclusive narrative of “us” (biz) and “ours” (bizim) constituting Turkey (see Figure 6). Populism, which rests on a construction of “the people” as the central audience of populist leaders, is mostly reflected in the oral, written, and visual communication of individual politicians, parties, and social movements (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2022; Reinemann et al. Reference Reinemann, Aalberg, Esser, Strömbäck, De Vreese, Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and De Vreese2017). The most important transformation in the online communication of these key governmental actors in 2014 is the addition of “election” (seçim) and “vote” (oy), as there was an upcoming election in 2015 (see Figures 6 and 7). Concurrently, “build” (yaptık) and “road” (yol) also emerged as important words in 2015, which were the most crucial catchphrases of the AKP’s election campaigns.

Figure 6. Word cloud of Erdoğan’s tweets in 2014.

Figure 7. Word cloud of the other AKP actors’ (Davutoğlu, Akdoğan, and Ala’s) tweets in 2014.

During the election campaign in 2015, the tweets of Davutoğlu, Ala, and Akdoğan also used the words “going on,” which represents their election campaign in 2015, entitled “keep going” (yola devam). The same tendency related to the general elections continues in 2015 with an added proposition of “thank you” (teşekkürler) for “their” (onların) voters in Erdoğan’s tweets (see Figure 8). The difference between 2015 and the previous years is the use of the word “terror” (terör) and the PKK in the wake of the collapse of the peace process. We traced a similar pattern in the three other AKP actors’ tweets, where they increasingly referred to the PKK and the PYD as terrorist organizations in 2015 (see Figure 9). This accounts for the changing dynamic of the peace process in 2015 and the AKP’s approach to the Kurdish movement as well as the changing online political campaign and rhetoric.

Figure 8. Word cloud of Erdoğan’s tweets in 2015.

Figure 9. Word cloud of the other AKP actors’ (Davutoğlu, Akdoğan, and Ala’s) tweets in 2015.

An analysis of Twitter posts from a micro perspective: the peace process and Syria between 2012 and 2015

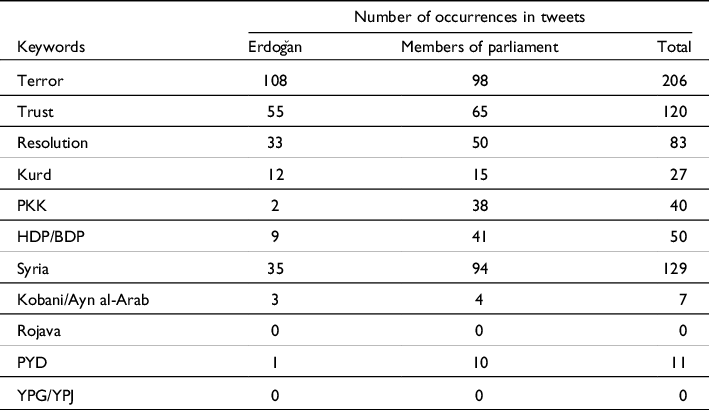

Our attention in the microanalysis shifted from a populist discourse around “us” to the polarizing discourse that aimed to identify “them.” In a deductive approach, we identified and searched for certain keywords relevant to the peace process, including different actors of the Kurdish movement in Turkey and Syria (see Table 2). In doing this, we aimed to expand on the “rationalities” on which politics is based (Finlayson Reference Finlayson2007) and explore how the AKP’s most important actors framed the peace process domestically, while depicting the Rojava experience in Syria.

Table 2. Occurrence of selected/searched keywords related to the peace process in the tweets of Erdoğan and three members of parliament (Davutoğlu, Akdoğan, Ala) between 2012 and 2015

Our analysis of social media data in this period exemplifies the governmental actors’ simultaneous use of terrorism in relation not only to the PKK but also Kurdish political parties in Turkey (i.e. HDP, BDP) and in Syria (i.e. PYD). On the one hand, the AKP actors rhetorically excluded and criminalized all Kurdish political actors by identifying Kurdish organizations as “terrorists.” On the other hand, they repeatedly blamed other opposition parties in the parliament for not supporting the attempts of the AKP to secure a peaceful resolution of the Kurdish question. The contradictory rhetoric of the AKP’s key actors was persistent throughout the period that we analyzed, which seemingly encouraged peace while closing off potential avenues for a peaceful resolution of the Kurdish question by criminalizing the key agents in this process.

We find that terror is the most frequently used keyword among all tweets. This keyword was sometimes used for terror in Turkey and sometimes for terror in other countries. For the purposes of this article, we focused on the use of the term terror addressing the PKK and the Kurdish movement in Turkey and in Syria. The use of terror in Erdoğan’s tweets shows how he linked the PKK with the BDP. In September 2012, Erdoğan shared a series of tweets that read:

Those who embrace terrorists cannot fight on behalf of the nation in the parliament. Even if they try to do so, they will not be respected. Because there are two choices. The solution to all kinds of problems is the field of democratic politics. Those who want to do politics on the mountains, let them go up the mountains. It has to be either Qandil [Mountains, where the PKK has its main bases], or the Turkish Grand National Assembly. If you choose the assembly, come and make your struggle in the assembly. Then you will find the politics, the government to negotiate with you.

This was a period when secret talks between the AKP government and the PKK had ended in 2011 but there were still indicators that a dialogue could be reinitiated (Savran Reference Savran2020). Shortly after this tweet, Erdoğan confirmed that the Oslo Talks took place under his orders to end terror. In parallel with this statement, Erdoğan shared tweets highlighting the AKP’s role to bring peace to Turkey. In 2013, Erdoğan repeatedly said that the peace talks should not be understood as weakening the struggle against terrorism and that the “solution to conflict in democratic societies would not be the mountains but the assembly, the tools for resolution are not weapons but politics.”

In his tweets on the peace process, Erdoğan also hinted at the motivation of an Islamic unity and fraternity in Turkey and underlined how the AKP is different from other political parties, such as the main opposition party, the CHP. In January 2013, Erdoğan shared three tweets, saying:

Some people may love only the Turks, some only the Kurds, they may speak in the language of anger, blood, revenge, but we are different. We wholeheartedly desire the solution, and we will never compromise our dignity to make it happen. We love human beings and people, not a race, an ethnic origin, a belief group, we love humankind because of the Creator.

Even at times when he was criticized by the opposition parties, Erdoğan remained defensive of the process and denied accusations of being treasonous to the Turkish state by conducting the peace talks. On the contrary, Erdoğan blamed those who stood against the peace process. The emphasis on resolution and democracy in his tweets increased in 2013 and 2014. In line with his political ambitions, Erdoğan in his tweets frequently targeted other strong political parties in the parliament while portraying the AKP as the only party that could enable a resolution of the armed conflict between Turkey and the PKK. Erdoğan ridiculed the CHP in his tweets, saying that the CHP could not go to Diyarbakır, which is referred to as the Kurdish capital in Turkey, or wave the Turkish flag in Hakkari, another Kurdish-dominated city with borders to Iran and Iraq.

In 2013, Erdoğan’s online narrative and performance revealed that he was happy about the wider societal support for the peace process. Throughout the year, and despite the Gezi protests that troubled the AKP government, Erdoğan continued to exchange messages of democracy and peace in his tweets. In July 2013, Erdoğan wrote: “We will solve our issues by advancing the Solution Process, by not reckoning but by making amends (helalleşerek). Footnote 7 We will candidly work for a lasting spring [bahar used to symbolize peace].” Erdoğan said that the mountains in Turkey, where there was terror in the past, were now places of happy incidents. Erdoğan also emphasized the unity of all people in Turkey and said, “We are against political Kurdism as well as political Turkism.”

One of the key events in 2013 was Erdoğan’s meeting with the President of the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq, Masoud Barzani, which took place in Diyarbakır on November 16, 2013. In these days, Erdoğan shared two tweets addressing the importance of peace for not only Turkey but for the wider Middle East: “As Diyarbakır changes, Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia will change, and Iraq and Syria will change. I hope the sun of peace rising from Diyarbakır will warm our entire geography.” These tweets indicated his larger ambitions of not only finding a peaceful solution to Turkey’s Kurdish question but also becoming a soft power in the Middle East at large.

Throughout the peace process, Erdoğan continued to ask for electoral support from Kurdish voters, using various online platforms and physical visits to Kurdish cities and neighborhoods. In March 2014, Erdoğan visited several Kurdish provinces and asked the Kurds “not to vote for political Kurdism but to vote for serving Kurdism,” with reference to the AKP’s narrative as the servants of the people.

After winning the presidential elections in August 2014, Erdoğan continued to emphasize his dedication to building peace. In October 2014, he tweeted: “The Solution Process is not condoning to bratty behavior. The Solution Process is not about submission, fear of threats, and retreat.” Erdoğan accused the HDP of being insincere since the beginning of the peace process, writing: “In the Solution Process, I have never seen sincerity from the HDP. If they were sincere, events such as October 6–7, Cizre, and SilopiFootnote 8 would not have happened.” Erdoğan also tweeted to question the sincerity of others, including the Western powers, as he blamed them saying: “The world is rising for Kobani; No one speaks for Aleppo, Mosul, Kirkuk, and Gaza, Mogadishu.” While the tweets on Syria in the previous years signified a “humanitarian” sensibility for refugees and general discontent with Bashar al-Assad, in 2015 the emphasis was on war against “the terrorists” in Syria. By this, Erdoğan mainly addresses the PKK and the PYD as sister organizations that operate not only in Turkey, Syria, and Iraq but also, in his view and rhetorical performance, in various parts of Europe.

Although Erdoğan was still sharing tweets that praised the peace talks, the tone of his tweets became more aggressive following the AKP’s loss of parliamentary majority in the June 2015 elections. As the peace talks with the PKK at home were interrupted and the Rojava experience in northern Syria gained more international support, Erdoğan addressed the “whole world” and said: “Whatever the costs may be, Turkey will never allow a state to be established in the north of Syria.” The armed conflict between Turkey and the PKK escalated in the summer of 2015, causing an increase in the number of tweets that Erdoğan shared on terror in a bid to show Turkey’s dedication to struggling against it by giving the terrorists “what they deserve.”

The populist online communication of Davutoğlu, Ala, and Akdoğan was in parallel with Erdoğan’s online narrative. On the one hand, they emphasized a strong desire to bring peace to Turkey. On the other hand, they labeled Kurdish political parties in Turkey and across borders as terrorists, shifting from a rather peaceful tone to a threatening one, particularly as the peace talks came to an end. Among the other three key actors of the peace process, Akdoğan stands out as the one who more persistently underlined that the PKK, BDP, and Abdullah Öcalan represent the same idea and that Turkey would stand against a stronger PKK in Syria.

In the summer of 2012, Akdoğan wrote that the AKP would not let the PKK exist in the “new Syria.” Like Erdoğan, Akdoğan also drew parallels between the PKK and the BDP, saying that the only aim of the BDP is to legitimize the PKK and to free Abdullah Öcalan. As the peace talks between Turkey and the PKK progressed in 2013, the narrative and performance in these actors’ public Twitter profiles became milder, although they were consistent in their argument that the PKK, BDP, and Öcalan were the representatives of terror. Despite these claims, however, the tweets of the three actors in 2013 show that the AKP seemed determined to continue with the peace talks and that criticizing the PKK did not mean the process would come to an end. Like Erdoğan, Akdoğan also addressed the importance of the peace talks for peace and security in Turkey as well as for Turkey’s regional aims and vision. In July 2013, Akdoğan shared a tweet in a threatening tone to warn the PYD not to “look for an adventure” in Syria and that if it declared democratic autonomy, it would mean they are simply “playing with fire.” In the same period, Akdoğan criticized the PYD for not being there when Assad was tyrannizing the Kurds and said that criticizing the PYD does not mean being against the Kurds or their desire for rights. In August 2013, the three tweets that Akdoğan shared signaled the close connection between the Rojava experience and the AKP’s perception of it as a PKK–PYD project, which affected the nature of the peace process in Turkey:

PYD’s imagination that it will achieve status in Syria produces a brattiness and condescending discontent with the democratic reforms in Turkey. Every step taken by the AK Party in the Kurdish issue has been ignored, belittled, or portrayed as the result of its own struggle by the organization. Öcalan has tried to reach an instrumental role through the PKK, and is now trying to reach a strategic role through the PYD.

In the same period, Efkan Ala shared a tweet with the hashtag #çözümesahipçık (#protecttheresolution), which is one of the most important instances of an authority figure starting a hashtag campaign on the issue. Although Ala pointed out that Syria was a security issue for Turkey and revealed Turkey’s frustration with the Kurdish movement(s) in Turkey and Syria, he still showed a determination to continue with the peace process.

Before Erdoğan met Barzani in November 2013, Akdoğan also shared tweets underlining the positive impacts of this meeting on the peace process, as well as democracy, peace, and fraternity in Turkey. On the day of the meeting, Davutoğlu wrote #kardeslikdiyari (#landoffraternity) to refer to Diyarbakır. Following the Diyarbakır meeting, Akdoğan shared tweets arguing that “the BDP/organization” were “perplexed” by Erdoğan’s meeting with Barzani and that they were most likely worried because their hegemony over the Kurds was shattered. It is important to highlight how Akdoğan uses a slash between the BDP and “organization” (implying the PKK) as mutually complementary terms. He also implied that the AKP’s good relationship with Barzani would weaken the PKK’s hegemony in the region.

In 2014, the tweets of the three actors were primarily focused on the war in Syria, the humanitarian crisis it had caused, and Turkey’s role in the war and the subsequent humanitarian crisis. Despite tensions with the PKK, the discursive dedication to a peaceful resolution of the Kurdish issue in Turkey was still visible in their tweets. In October 2014, Akdoğan wrote that the AKP would not be happy if Kobani fell or with the presence of ISIS on its borders. However, referring to the criticisms against Turkey for its passive stance on the war in Kobani, Akdoğan wrote: “Using the incidents outside of Turkey, which we [as Turkey] are not directly involved in, as excuses to create fragility in the peace process is irresponsible.”

Regardless of such tweets, there were also references to determination and the declaration of intentions for a successful peace process. In March 2014, Davutoğlu wrote that they would persistently hold on to fraternity to maintain the peace process and stability under the AKP’s rule. In June 2014, Ala shared a tweet with a photograph from the Peace Process Workshop. Starting from early 2015, however, there were increasing references to terror and security in the AKP actors’ top-down online communication. There were no references to Rojava and the YPG in the tweets in February 2015, although Operation Shah Euphrates was jointly conducted with the YPG/YPJ fighters in Northern Syria. In February 2015, after signing the Dolmabahçe Agreement, Akdoğan tweeted “May the resolution have a good result.” From March 2015 onwards, however, the Dolmabahçe Agreement was denounced and there was a significant increase in the criticism against the HDP and its then co-chair, Selahattin Demirtaş. Before the elections, Akdoğan continued to identify the AKP as the “warden of peace,” saying: “If the AK Party remains strong then peace and stability can be maintained, the peace process can succeed, a new constitution can be made.”

Following the June 7 elections and HDP’s unprecedented electoral success, the online narrative and performance against the HDP became visibly more hostile. The reference to “peaceful mountains” by Erdoğan was replaced with a pejorative discourse that implied that the HDP came from the mountains. From July 2015 onwards, when the peace process had effectively ended and urban warfare began between the Turkish state and the PKK, the dominant narrative on Twitter was related to terror and the PKK. In this way, the official social media discourse of the AKP turned into a heightened emotional response against Kurds, targeting their political movement and appealing to Turkish nationalism. A tweet shared by Akdoğan in July 2015 supports this argument: “We have already said that it is the vote the AKP gets – not the vote that HDP gets – that affects how the process would continue, and that the main determining actor is the AKP.” Overall, the microanalysis of the AKP actors’ online narrative and performance shows continuously contradictory rhetoric, where they label the Kurdish political parties as “terrorists” while portraying the AKP as the only actor in Turkish politics that could bring peace and service to the Kurds.

Conclusion: changing online narratives of the unchanging Kurdish politics in the new Turkey

Already in the late 2000s, the AKP was criticized for increasingly leaning toward authoritarianism (Sözen Reference Sözen2008). This tendency became more evident with the government’s policies toward political dissent in the country during the Gezi protests in 2013, in the process of the termination of the peace process with the PKK, and even more so following the failed coup attempt on July 15, 2016. Internationally, the civil uprisings in Syria in 2011 led to a civil war in the country and the emergence of de facto autonomy led by the Kurdish movement in northern Syria in 2012, known as the Rojava Revolution (Boyraz Reference Boyraz2021; Cemgil Reference Cemgil2016; Dinc Reference Dinc2020; Duman Reference Duman2016; Knapp et al. Reference Knapp, Flach and Ayboga2016; Küçük and Özselçuk Reference Küçük and Özselçuk2016; Schmidinger Reference Schmidinger2018). The latter has troubled the Turkish state and the AKP government, which has identified the Rojava administration as an extension of the PKK in Syria and a terrorist organization. Turkey has launched a series of cross-border military operations led by the Turkish army (together with the Syrian National Army, also referred to as the Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army) since 2016. As Turkey prepares to celebrate the centenary of its founding in 2023, it is also reportedly preparing for the fourth incursion into northern Syria.

Existing research has addressed the misrepresentation and/or under-representation of the Kurdish question and Kurdishness in Turkish media over the years (see Sezgin and Wall Reference Sezgin and Wall2005; Somer Reference Somer2005), which has been bolstered under the AKP’s rule (see Akser and Baybars-Hawks Reference Akser and Baybars-Hawks2012; Emre Cetin Reference Emre Cetin2018; Tunç Reference Tunç2018; Yesil Reference Yesil2016; Yıldırım et al. Reference Yıldırım, Baruh and Çarkoğlu2021). The current “media autocracy,” resting primarily on conglomerate pressure, judicial suppression, online banishment, and surveillance defamation (Akser and Baybars-Hawks Reference Akser and Baybars-Hawks2012), consolidates the discursive techniques used by the main AKP leaders in their personal accounts, particularly in relation to Kurds, who have been their most important perceived national threat. While recent research rightly shows that sharing images of “mutilated and humiliated dead bodies” of the PKK militants by members of the Turkish security forces in the aftermath of the peace process was part of the media performances of dehumanization of the “other” (Tutkal Reference Tutkal2022, 166), our article argues that there are nuances in the official online message around the “re-humanization” and “dehumanization” of the “Kurdish figure” in Turkey in different periods of the peace process. We showed how this amounts to a populist political communication style in the re-construction of power through the reconstitution of Turkishness and Sunni-Muslim identity and the re-dehumanization and re-criminalization of Kurdish identity via online rhetoric (Block and Negrine Reference Block and Negrine2017; Laclau Reference Laclau2007). This rhetoric bolsters and spreads right-wing populist ideas (De Vreese et al. Reference De Vreese, Esser, Aalberg, Reinemann and Stanyer2018), especially through the performance and self-presentation of right-wing populist actors (Aalberg et al. Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and De Vreese2017; Engesser et al. Reference Engesser, Fawzi and Larsson2017), using direct, unmediated, outrageous, polarizing, shocking, and emotional rhetoric (Gil de Zúñiga et al. Reference Gil de Zúñiga, Koc Michalska and Römmele2020).

Our findings show that, despite the ongoing peace talks, the AKP consistently labeled the Kurdish political movement in Turkey, legal and illegal alike, as “terrorists.” Even during times of peace talks, the AKP actors addressed different Kurdish organizations in Turkey and Syria under the banner of “terrorists.” In the meantime, the AKP sustained a “strategic partnership” (Ozeren et al. Reference Ozeren, Bastug, Cubukcu, Orofino and Allchorn2023, 129) with the Free Cause Party (Hür Dava Partisi; HÜDAPAR) to divide the Kurdish vote between the “violent/secular” Kurds and “peaceful/conservative” AKP, which similarly rested on an “us” and “them” division in society.

We also show how Twitter is used to reach specific stakeholders during rapidly changing time periods and how online platforms transform into avenues for digital storytelling (Burgess Reference Burgess2006; Couldry Reference Couldry2008; Pamment Reference Pamment2016), targeting specific audiences or making new audiences. States and governmental actors also increasingly carry out parallel online management of key national and transnational issues, which helps them appeal to their onlookers, young voters, and sympathizers. Our analysis of the tweets shared by the four key actors of the AKP between 2012 and 2015 shows that the AKP used Twitter effectively to consolidate power and reach its voter bases through a populist majoritarian strategy, propaganda, and agenda-setting. Through active engagement with the Kurdish question on social media platforms, Erdoğan and his key members of parliament aimed to build a widespread agenda and appeal that cater to their young national audiences (voters and potential voters), while also helping them in keeping their international counterparts and other potential onlookers aligned with their shifting aims and strategies.

Our research indicates that the AKP, while appearing to challenge Kemalism and its relationship with the Kurds in its media rhetoric, was in fact mimicking it under the strong leadership and personality cult of Erdoğan, also defined as Erdoganism (Christofis Reference Christofis2018; Dinc Reference Dinc2021; Yilmaz and Bashirov Reference Yilmaz and Bashirov2018). In the early periods of the peace process, the AKP aimed to manage its social media presence to market itself as a “softer” alternative to the Kemalist history and ideology of modern Turkey that had “already” denied and oppressed Kurdish identity (Zeydanlıoğlu Reference Zeydanlıoğlu2008). In this earlier online performance, the main opposition party, the CHP, was the main actor that was not only criticized but also openly blamed for Turkey’s unresolved Kurdish question. Although the AKP’s critique was not groundless, the analysis of macro- and micro-level online political speech of the key AKP actors shows the transition in the depiction of the solution process from a historical step toward building peace between Turkey and the PKK to an expendable attempt to build peace with the Kurdish political movement that was now identified under the homogeneous entity of “internal threat” and “terror.”

Overall, our analysis shows that the AKP presented itself both as the only actor that persistently aims for peace and as the power holder that can use force to fight against terror at home and abroad when needed. This fluid representation of the AKP allowed it to ridicule the opposition parties who stood against the peace talks, maintain the framing of the pro-Kurdish parties as terrorists, and therefore underline that the AKP was the only party that could democratize and bring peace to Turkey and the Middle East. Our study of the Twitter performance of key political actors of the AKP government in different time periods of the peace process accounts for how the AKP aimed at Kurdish voters in 2013 and 2014, whereas it aimed at the Turkish nationalist voters in 2015, when the peace process ended and when the AKP formed a new pact with the Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi; MHP). This is consistent with previous research that has shown the rise of online hate and polarization from 2015 onwards, informing the expansion of such trends on social media platforms more recently (see Ozduzen Reference Ozduzen2020), as the AKP turned into a hegemonic force that relies increasingly on coercion rather than consent to enforce its policies and shape an ever-increasing proportion of the everyday lives of Kurds and dissident communities at home and beyond, especially using populist narratives on social media platforms.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Cansu Ozduzen, James Root, and Bogdan Ianosev for their help with the manuscript. Finally, we would like to thank the editors of New Perspectives on Turkey and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on the earlier drafts of this article.

Conflicts of interest

None.