Introduction

Amongst terrestrial mammals, carnivores are the most threatened group and the most challenging to conserve (Karanth & Chellam, Reference Karanth and Chellam2009). People tend to see carnivores, particularly large species such as the jaguar Panthera onca and lion Panthera leo, as a direct threat. These species compete for land and game and sometimes prey upon livestock (Sillero-Zubiri & Laurenson, Reference Sillero-Zubiri, Laurenson, Gittleman, Funk, Macdonald and Wayne2001). Intolerance for carnivores has led to the persecution, decline and local extinction of some species (Treves & Karanth, Reference Treves and Karanth2003). Although some carnivore populations are increasing as a result of conservation initiatives (e.g. LaRue et al., Reference Larue, Nielsen, Dowling, Miller, Wilson, Shaw and Anderson2012), encounters between people and carnivores will probably increase as the human population continues to grow.

Factors such as age, education, and knowledge about carnivores can affect people's attitude and willingness to conserve a species. For example, older respondents hold a more negative view of jaguars than younger individuals (Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Walpole and Leader-Williams2005), and ranchers who have completed fewer years of school show stronger negative attitudes towards the species than those with higher education (Cavalcanti et al., Reference Cavalcanti, Marchini, Zimmermann, Gese, Macdonald, Macdonald and Loveridge2010). The more knowledge a person has of a species, the more likely they are to protect it or view wildlife positively (Kellert, Reference Kellert1985), although more knowledgeable individuals, such as hunters, may have less favourable attitudes towards carnivores (Ericsson & Heberlein, Reference Ericsson and Heberlein2003). Therefore, the knowledge and attitudes of people living with wildlife need to be assessed and integrated into conservation strategies.

Attitudes towards carnivores may also reflect the degree of negative interaction between a person and a species (Kellert, Reference Kellert1985). In South Africa, for example, negative attitudes towards the African wild dog Lycaon pictus are related to the economic costs of livestock and wild game predation (Lindsey et al., Reference Lindsey, du Toit and Mills2005). Domestic livestock are ideal prey for carnivores as they are often abundant and easy to catch in comparison to other prey (Palmeira et al., Reference Palmeira, Crawshaw, Haddad, Ferraz and Verdade2008). Ranchers troubled by livestock predation have a range of protection techniques available to them (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Linnell, Odden and Swenson2000; Sillero-Zubiri et al., Reference Sillero-Zubiri, Reynolds, Novaro, Macdonald and Sillero-Zubiri2004; Sillero-Zubiri & Switzer, Reference Sillero-Zubiri, Switzer, Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffmann and Macdonald2004). Some of these strategies are non-invasive (e.g. flags on fencing), whereas others may result in the carnivore's death (e.g. shooting). Managers must appraise the expenditure of money and time, effectiveness, legality and cultural appropriateness of each technique.

Most research on human–carnivore interactions and attitudes towards these species has focused on larger species. Human–canid interactions are well documented for large species such as the grey wolf Canis lupus (Treves et al., Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves, Harper, Mladenoff, Rose, Sickley and Wydeven2004), Ethiopian wolf Canis simensis (Yihune et al., Reference Yihune, Bekele and Ashenafi2008), coyote Canis latrans (Draheim, Reference Draheim2012) and maned wolf Chrysocyon brachyurus (Emmons, Reference Emmons2012), but less so for small canids other than the red fox Vulpes vulpes (Moberly et al., Reference Moberly, White and Harris2004). Of the 36 species of canids, 10 live in South America (Sillero-Zubiri, Reference Sillero-Zubiri, Wilson and Mittermeier2009). Knowledge of interactions with these species is limited to a few studies of the Andean fox Lycalopex culpaeus (Travaini et al., Reference Travaini, Zapata, Martínes-Peck and Delibes2000), South American grey fox Lycalopex griseus (Silva-Rodrígues et al., Reference Silva-Rodríguez, Soto-Gamboa, Ortega-Solis and Jiménez2009), hoary and crab-eating foxes Lycalopex vetulus and Cerdocyon thous (Lemos et al., Reference Lemos, Azevedo, Costa and May-Junior2011a) and bush dog Speothos venaticus (DeMatteo, Reference DeMatteo2008).

The maned wolf, crab-eating fox, and hoary fox are sympatric in the Cerrado ecosystem (Juarez & Marinho-Filho, Reference Juarez and Marinho-Filho2002; Jácomo et al., Reference Jácomo, Silveira and Diniz-Filho2004; Lemos, Reference Lemos2016). The Cerrado was once an expansive grassland, but intense agriculture and ranching has severely altered the landscape (Klink & Moreira, Reference Klink, Moreira, Oliveira and Marquis2002; Klink & Machado, Reference Klink and Machado2005). Because of these activities, the hoary fox (endemic to the Cerrado) and the maned wolf are currently categorized as Vulnerable in Brazil (Lemos et al., Reference Lemos, Azevedo, Beisiegel, Jorge, Paula, Rodrigues and Rodrigues2013; Paula et al., Reference Paula, Rodrigues, Queirolo, Jorge, Lemos and Rodrigues2013), even though these species are categorized as Least Concern (Dalponte & Courtenay, Reference Dalponte and Courtenay2008) and Near Threatened (Paula and DeMatteo, Reference Paula and DeMatteo2016), respectively, on the IUCN Red List. The crab-eating fox remains common throughout its range and is categorized as Least Concern both globally (Lucherini, Reference Lucherini2015) and in Brazil (Beisiegel et al., Reference Beisiegel, Lemos, Azevedo, Queirolo and Jorge2013).

In such a highly fragmented landscape, native prey species may be uncommon and domestic livestock becomes an accessible alternative prey for carnivores. Abade et al. (Reference Abade, Lemos and Azevedo2012) reported that in the Cerrado ecosystem the perceived loss of domestic fowl (chickens, ducks, geese and guinea fowl) was an unwelcome interaction between landowners and Cerrado canids. Our study builds on this work, examining the socio-economic factors that may influence peoples’ attitudes towards Cerrado canid species. We used structured interviews to examine local knowledge of Cerrado canids and attitudes towards these species. Because Abade et al. (Reference Abade, Lemos and Azevedo2012) reported that canids in our study area preyed on domestic fowl rather other domestic species such as calves, we also quantified current chicken management practices and measured the perceived cost and effectiveness of these methods. We hypothesized that (1) interviewees who correctly identified and demonstrated knowledge about Cerrado canids would have a more positive attitude towards them, (2) the method perceived most effective for preventing predation of domestic animals would be the most frequently implemented, and (3) respondents who experienced predation of chickens would have a more negative attitude towards predators.

Study area

This study was carried out in the Limoeiro region, a farming area within the municipality of Cumari, Goiás state, in central Brazil (Fig. 1) that comprises contiguous private cattle ranches and small-scale agriculture operations (e.g. rubber trees, corn and sugarcane; collectively c. 150 km2). The landscape is dominated by exotic pasture (Urochloa spp.; 73%), with the remaining area being a mosaic of natural gallery and seasonal forests (21%) and open Cerrado sensu stricto (4%; Lemos, Reference Lemos2016). The climate is tropical with two well-defined seasons, cold/dry (May–September) and hot/wet (October–April; Alvares et al., Reference Alvares, Stape, Sentelhas, Moraes Gonçalves and Sparovek2013), with mean temperatures of 19 and 30 °C, respectively, and a mean annual precipitation of 1,551 mm (CPTEC/INPE, 2015).

Fig. 1 Locations of ranches in the Limoeiro region, municipality of Cumari, Goiás state, in central Brazil, where interviews were conducted to investigate local perceptions of three Cerrado canid species: the maned wolf Chrysocyon brachyurus, the crab-eating fox Cerdocyon thous and the hoary fox Lycalopex vetulus.

Methods

Surveys

Fifty ranches in the Limoeiro region that raised domestic fowl were opportunistically surveyed during June–August 2014. The selected respondent at each ranch was at least 18 years old and was directly responsible for managing the domestic fowl: either the owner (rancher, 44%) or the hired ranch hand (cowboy, 56%). Each respondent was asked to sign a consent form before starting the interview, was assured confidentiality, and could discontinue or withdraw from the interview at any time. All interviews were conducted in Brazilian Portuguese, with the assistance of a native speaker, and recorded.

Questionnaire

We used a structured questionnaire developed to evaluate the interviewees’ knowledge, experience, and attitudes towards the maned wolf and crab-eating and hoary foxes, and domestic fowl management practices. The questionnaire was first tested at 15 ranches, refined, and retested at the same 15 ranches. The final questionnaire (Supplementary Material 1) was administered at an additional 35 ranches and comprised 20 questions that combined multiple-choice (nominal data) and open-ended questions (Bernard, Reference Bernard2006). Comments made by interviewees that complemented answers were noted, but were not included in the data analysis.

The questionnaire had sections on demographics, knowledge of carnivores and Cerrado canids, domestic fowl management practices, and attitudes towards Cerrado canids. A canid knowledge score was calculated. Participants were first asked to identify the three species from photographs, and then, for each species, to select its prey from a list, its social structure, and indicate when it is most active. An interviewee was assigned one point for each correct response, for up to a total of four points per species. An overall knowledge score was calculated by summing the three canid knowledge scores (the maximum possible score was 12).

Chicken management practices observed during initial ranch visits were standardized on the questionnaire to nine common methods of preventing predation. Perceptions of the cost and effectiveness of these methods were measured by asking interviewees to identify the most and least expensive, and most and least effective predation prevention practice. Interviewees also answered questions about each perceived chicken predation by Cerrado canids and other species, and the occurrence of these events.

Attitudes towards each Cerrado canid species were measured using a series of suggested statements. Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with each statement, or they could indicate ‘unknown’. Interviews concluded with a tour of the ranches’ domestic fowl rearing facilities.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were derived for all qualitative questions. A t test was used to determine if selling chickens (yes, no) influenced the quantity of chickens raised in the past year at each ranch. Canid knowledge scores among species were compared using a repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference post-hoc test. A multiple linear regression model was used to identify which combination of explanatory variables (age, education level, position on the ranch, sale of chickens) contributed to a person's knowledge of Cerrado canids. Relationships with categorical variables (predation prevention method, attitudes towards canid species, action taken in response to domestic fowl predation) were analysed using a χ 2 test. If the expected outcome was < 5, a Fisher's exact test was used instead (Sokal & Rohif, Reference Sokal and Rohlf1995). Bivariate analyses were conducted between reported perceived predation and number of chickens, and between predation and number of predation prevention methods employed. A bivariate regression analysis was conducted between attitude (agreement or disagreement with the statement ‘I like having this animal on my ranch’) and explanatory variables (education level, sale of chickens, experience with predation, knowledge score and age).

All statistical analyses were conducted using R 3.2.3 (R Development Core Team, 2015). Models were fitted by a backwards stepwise process: all variables were initially included in the model (a saturated model) and then the Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to remove the parameters that least affected the model fit (Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson2002).

Results

Demographics

Fifty male respondents participated in structured interviews (men generally oversaw the management of the domestic fowl). The mean age of the study population was 53.62 ± SE 2.09 years and 68% had completed ≤ 8 years of schooling. Ranch size varied (1.21–1,306.80 ha) but the majority (56%) were < 300 ha. The respondents who sold their chickens and/or eggs (< 20%) raised significantly more chickens (73.89 ± SE 8.90) than those who did not sell them (44.53 ± SE 5.57; t 31 = 2.80, P < 0.01). Respondents sold a dozen eggs for BRL 5–8, and chicks, hens and roosters for BRL 10, 15–20 and 30 each, respectively. Almost all respondents (96%) reported the domestic fowl and their eggs formed part of the family's diet.

Knowledge of Cerrado canids

Respondents’ knowledge of canids differed significantly by species (F 2,98 = 40.82, P < 0.01). Post-hoc tests indicated that knowledge scores (on a scale of 0–4) were significantly higher for the maned wolf (3.64 ± SE 0.07) than for the crab-eating (2.84 ± SE 0.12) and hoary foxes (2.36 ± SE 0.13), and knowledge of the crab-eating fox was greater than that of the hoary fox (P < 0.01). Eighty-eight per cent of the interviewees correctly identified the maned wolf from a photograph, whereas 28% misidentified the two fox species for each other. A multiple regression model did not reveal (P > 0.05) any combination of variables (i.e. age, education level, position on the ranch, sell chickens) that could explain overall knowledge of Cerrado canids.

Current chicken management practices

Domestic fowl included chickens, guinea fowl, ducks and geese. All respondents raised chickens and < 20% raised a small number (≤ 10) of guinea fowl, ducks and/or geese in addition to chickens. As chickens were the predominant domestic fowl species, results hereafter will be presented in the context of management of chickens. However, management practices were consistent across all types of domestic fowl.

On 90% of the ranches chickens were allowed to range freely around the property during the day. Less than half (44%) of the ranches confined their chickens in some form of chicken coop or fenced yard at night. At the other ranches, chickens roosted in trees (48%), in a covered cattle corral (6%) or on roosting ladders (2%) at night. Chicks aged 5–30 days were kept in an enclosed area both day and night at 62% of the ranches. No difference in the use of chicken coops/fenced yards was found between respondents who sold their chickens and/or eggs and those who did not (χ 2 = 0.41, df = 1, P = 0.58).

Nine additional management practices to prevent chicken predation were identified (Table 1). The most common practice (90%) used by the study population was keeping one or more untrained, outdoor dogs. Lights, noise, flags, poison, electric fencing and scarecrows were used at ≤ 26% of the ranches (Table 1).

Table 1 A summary of the per cent of 50 ranches in the Limoeiro region, central Brazil (Fig. 1), using common chicken predation prevention techniques in relation to interviewees’ views of the perceived cost and effectiveness of each method. Perceived predation events are reported as the percentage of ranches experiencing predation while using the method. A goodness-of-fit test determined the ability of each method to prevent predation.

*P ≤ 0.05.

1 All interviewees used multiple predation prevention methods.

Perceptions of common management practices

Respondents perceived chicken coops to be the most expensive (72%) and most effective (38%) management practice to prevent predation (Table 1). Dogs and banners/flags were identified as being among the cheapest methods (30 and 34%, respectively); however, the use of dogs was perceived as being more effective (30%) than banners/flags (26%; Table 1). Interviewees considered the use of scarecrows to be an ineffective management practice, although the few ranches that used them reported not experiencing predation (Table 1).

Perceived chicken predation by Cerrado canids

A total of 32 cases of perceived chicken predation were reported to have occurred among 20 of the 50 ranches in the year prior to the study. Respondents reported the hoary fox as the culprit in 38% of the predation events, the maned wolf in 35% and the crab-eating fox in 28%. When asked how they knew which animal took the chicken(s), some respondents stated that either they or the ranch hand had seen the canid (hoary fox: 72%, maned wolf: 52%; crab-eating fox: 55%). Birds of prey and the striped hog-nosed skunk Conepatus semistriatus were also frequently reported to have taken chicks and eggs, at 18 and 16% of ranches, respectively. A full list of species perceived to be predators of chickens is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Reported predation events were not related to the number of chickens on the ranch (Z = 0.86, P = 0.39).

Respondents used 0–5 predation prevention methods (2.42 ± SE 0.18); however, there was no relationship between number of predation events and the number of methods employed (Z = 0.83, P = 0.41). Furthermore, interviewees reported that predation occurred regardless of which prevention method they used, except for scarecrows (Table 1). Poison was particularly ineffective (P = 0.01) at preventing predation of chickens (Table 1). Of those who lost chickens to predation, 65% stated that predation events occurred when the chickens were in the yard during the day. Total economic loss as a result of chicken predation could not be calculated because some respondents (39%) were unsure of the number of chickens killed, and others (54%) gave a range rather than a number.

Attitudes towards Cerrado canids

Most respondents (78–86%) agreed that they liked having Cerrado canids on their property even though 92% of the interviewees perceived these species to be a threat to chickens (Table 2). Fewer respondents (8%) perceived them to be a threat to cattle (Table 2). When asked about the ecological benefits of wild canids, 50–64% of respondents remarked that these animals eat the rodents and insects on their ranch, and 78–92% agreed that Cerrado canids were valuable (Table 2).

Table 2 The per cent of 50 respondents who agreed with each of the following statements related to attitude, risk, and ecological benefits of the maned wolf Chrysocyon brachyurus, and crab-eating fox Cerdocyon thous and hoary fox Lycalopex vetulus, and the action they would take in response to chicken predation.

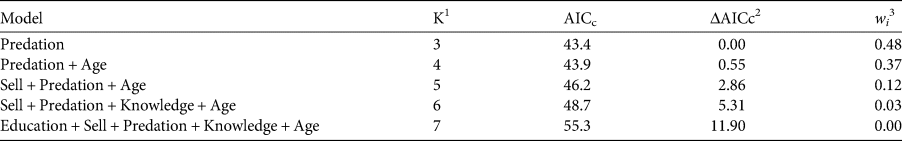

A logistic regression model indicated that perceived predation was the best variable for explaining the attitudes of interviewees towards Cerrado canids (Tables 3 & 4). Local people who experienced predation of their livestock reported not liking these species. Four interviewees admitted to killing at least one Cerrado canid while living in the area but no one stated they had killed a wild canid in the previous year. One respondent commented that the killing was in response to chicken predation, and two respondents said their dogs had carried out the killing. Attitude was a significant predictor of wanting to protect these species (Z = 2.18, P = 0.03); those who had a positive attitude towards these species agreed they should be protected. When asked what action participants would take in response to chicken predation by a Cerrado canid, significantly more respondents remarked that they would change their management practices, regardless of their attitudes towards these species (maned wolf: χ 2 = 10.48, P = 0.02; crab-eating fox: χ 2 = 13.68, P = 0.01; hoary fox: χ 2 = 12.88, P = 0.01; Table 2).

Table 3 Candidate model rankings for predicting attitudes of local residents towards Cerrado canids.

1 Number of estimable model parameters.

2 Difference in value between Akaike's Information Criterion for small sample size (AICc) of the current and best model.

3 Akaike weight: the probability that the current model is the best model.

Table 4 Logistic regression model parameter estimates for predicting attitudes of local residents towards Cerrado canids.

Discussion

Knowledge

This was the first study to quantify local community knowledge and attitudes towards the maned wolf, crab-eating fox and hoary fox in relation to interactions with people. Respondents in the Limoeiro region exhibited greater knowledge about the diet, activity period and social structure of the maned wolf in comparison to the crab-eating and hoary foxes, and frequently confused the two fox species. This is in line with the trend that more is typically known about large, charismatic, flagship species, such as the maned wolf, than mesocarnivores such as small canids (e.g. the dhole Cuon alpinus; Jenks et al., Reference Jenks, Songsasen, Kanchanasaka, Leimgruber and Fuller2014).

Our hypothesis that interviewees who correctly identified and demonstrated more knowledge about Cerrado canids would have a more positive attitude towards them was not supported. These results probably reflect that the overall knowledge varied only slightly amongst respondents and that direct experience with Cerrado canids was more important; i.e. among the tested variables, the predation of domestic fowl was the best predictor of attitude in the Limoeiro region.

Cerrado canids and chicken management

Canid species are known to attack poultry (Sillero-Zubiri & Laurenson, Reference Sillero-Zubiri, Laurenson, Gittleman, Funk, Macdonald and Wayne2001), and scat dietary analysis has been used to confirm predation (e.g. Silva-Rodríguez et al., Reference Silva-Rodríguez, Soto-Gamboa, Ortega-Solis and Jiménez2009). Poultry remains have been found in the scat of both maned wolves and crab-eating foxes (Juarez & Marinho-Filho, Reference Juarez and Marinho-Filho2002; Courtenay & Maffei, Reference Courtenay, Maffei, Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffmann and MacDonald2004; Jácomo et al., Reference Jácomo, Silveira and Diniz-Filho2004) but never in the scat of hoary foxes (Juarez & Marinho-Filho, Reference Juarez and Marinho-Filho2002; Jácomo et al., Reference Jácomo, Silveira and Diniz-Filho2004; Lemos et al., Reference Lemos, Facure, Azevedo, Rosalino and Gheler-Costa2011b; Kotviski, Reference Kotviski2017). Ninety per cent of the hoary fox diet comprises insects (Lemos et al., Reference Lemos, Facure, Azevedo, Rosalino and Gheler-Costa2011b). Our results indicated that 40% of the ranches sampled perceived that Cerrado canids preyed on their chickens. All three canid species were perceived to be predators of chickens, although the hoary fox was more frequently identified as the culprit. The hoary fox is nocturnal and frequently dens and forages in open cattle pastures (Lemos et al., Reference Lemos, Facure, Azevedo, Rosalino and Gheler-Costa2011b; Lemos, Reference Lemos2016). Respondents reported seeing the hoary fox often when working with their cattle in the field, particularly during dawn and dusk. It is possible they considered the hoary fox responsible for killing chickens simply because they saw it more often. Additionally, respondents frequently confused the hoary and crab-eating foxes. Thus, they could also be misidentifying the hoary fox as a chicken predator when the culprit was the crab-eating fox.

Our second hypothesis, that the method perceived as being the most effective at preventing predation would be the most frequently implemented among ranches, was mostly supported. The chicken coop was identified as the most effective practice to prevent chicken predation. Yet in practice, chickens were free-range during the day, and confined at night at only 44% of the ranches; and not all structures were observed to be predator-proof (e.g. there were broken doors and holes in fencing). Respondents also identified dogs as an effective preventive method, with 90% of interviewees reporting using one or more dogs for this purpose. Chicken coops were identified as the most expensive method of predation control because of the cost of wire and wood, whereas dogs were considered to be one of the cheapest methods (domestic dogs are commonly fed scraps and are rarely vaccinated in the Limoeiro region). The perceived cost of building a chicken coop could be limiting the use and soundness of this type of structure, even though it was deemed the most effective.

Most ranches used multiple predation control methods but none were found to effectively prevent predation, probably because most of the reported predation events occurred during the day, when the chickens were foraging around the house. Confinement of chickens during the day and at night could potentially solve the problem of daytime predation (e.g. Silva-Rodrígues et al., Reference Silva-Rodríguez, Soto-Gamboa, Ortega-Solis and Jiménez2009); however, culturally, local people prefer to raise caipira (free-ranging) chickens. Respondents commented that caipira chickens have a broader diet and taste better than those that are raised in confinement (fed only with corn), and command a higher price in the city. Moreover, the cost of having to feed the chickens in addition to the already perceived high cost of fencing and wood makes permanent confinement an impractical solution. Johnson & Franklin (Reference Johnson and Franklin1994) and Silva-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Silva-Rodríguez, Soto-Gamboa, Ortega-Solis and Jiménez2009) suggested that night confinement of chickens was potentially a cost–benefit compromise to permanent confinement because it prevents more losses when canid species are most active. However, our results indicated that chickens, when allowed to roam freely during daylight hours, were still at risk of predation by other wildlife (e.g. hawks, tegus and snakes).

Attitudes towards Cerrado canids

In support of our third hypothesis, and consistent with carnivore research elsewhere (e.g. Lindsey et al., Reference Lindsey, du Toit and Mills2005; Cavalcanti et al., Reference Cavalcanti, Marchini, Zimmermann, Gese, Macdonald, Macdonald and Loveridge2010), the attitudes of respondents in the Limoeiro region were linked with economic loss. Respondents who experienced predation events were more likely to report they did not like having wild canids on their property. However, most interviewees agreed that Cerrado canids need to be protected and that they are valuable; a response possibly induced by social norms or a product of interviewing bias (Bernard, Reference Bernard2006). It is encouraging that most respondents (46%) stated they would change their management practice in response to predation events rather than eliminate the predator, and 14% of interviewees perceived the use of poison to be an ineffective predator-control method, although some continue to use it (Lemos et al., Reference Lemos, Azevedo, Costa and May-Junior2011a,Reference Lemos, Facure, Azevedo, Rosalino and Gheler-Costab; Lemos, Reference Lemos2016).

Future directions for Cerrado canid conservation

In the Limoeiro region, perceived predation of domestic fowl by Cerrado canids is the strongest predictor of a negative attitude towards these species. Our study, along with those of Lemos et al. (Reference Lemos, Azevedo, Costa and May-Junior2011a,Reference Lemos, Facure, Azevedo, Rosalino and Gheler-Costab) and Lemos (Reference Lemos2016), found that lethal control is sometimes used in retaliation for such events, or as a preventive measure. Improving management practices could potentially reduce chicken predation and the need for lethal control of canids. Physical barriers such as fences and walls are used extensively as a predator control method (Sillero-Zubiri & Switzer, Reference Sillero-Zubiri, Switzer, Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffmann and Macdonald2004). Respondents in our study and in that of Silva-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Silva-Rodríguez, Soto-Gamboa, Ortega-Solis and Jiménez2009) commented on the expense of wood and wire for fencing, and food supplements (grain) for a chicken coop. Financial assistance towards building coops from wood and wire or pooling together other natural or unused material to maintain structural soundness could support the use of coops as a regional model for predation management. Domestic dogs used on the ranches are usually untrained, but taking the time to formally train a dog to stay and guard the chickens while they forage in the field during the day could reduce predation risk and the costs associated with supplemental feeding, and the caipira status of the chickens.

In summary, this study highlights the importance of incorporating human dimensions in wildlife management and conservation. Changes in behaviours and management practices can often mitigate undesirable interactions with carnivore species. The results of this research are being used to guide outreach efforts that promote the conservation of Cerrado canids by collaboratively working with the ranchers in the Limoeiro region and with other stakeholders of Cumari, such as the municipal environmental secretary.

Acknowledgements

We thank the interviewees for their participation and hospitality, the Fulbright Brazil Student Grants, George Mason University, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, Suzanne B. Engel, Jane Smith Turner Foundation, and Maned Wolf Species Survival Plan for financial support, and Ricardo Corassa Arrais for carrying out the interviews and translations.

Author contributions

Project design, securing permits, writing and/or revision: SMB, FGL, MPG, FCA, EWF and NS; data collection and analyses: SMB; overall supervision: NS.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The research protocol was approved by Universidade Federal de Goiás/Plataforma Brasil (23120213.6.0000.5083) ethics committee, George Mason University Human Subjects Review Board (478275), and the Smithsonian Institution Human Subject Review Board (0005809).