Modern studies of the Severan emperors often have placed a significant focus on the role played by women within the dynasty.Footnote 1 Unmitigated acceptance of ancient literary constructions of these women, in conjunction with a belief (from isolated epigraphic evidence) that this period saw an ‘orientalization’ of Roman religion and culture, often resulted in the belief that the Empress Julia Domna heralded the beginning of a dynasty of powerful eastern women who corrupted the essence of ‘Roman’ culture.Footnote 2 Von Domaszewski's condemnation of Domna was particularly influential in this respect,Footnote 3 but more recent works have come to a better understanding of the public role of these women,Footnote 4 demonstrating that the Severan empresses were not an ‘eastern’, corrupting force, but formed an important connective role. Initially the women of the Severan house created a sense of continuity with the Antonines, going on to form the connective basis for the Severan dynasty itself.Footnote 5 Central to this scholarly development in studies of the Severan women has been the separation of material authored by the regime from the representation of the Severan women in private and provincial contexts.Footnote 6

One of the best-preserved sources from which to gain a better idea of the image of the Severan women is the official coinage released by the imperial mints. The chief imperial mint was located in Rome, though in the Severan period smaller mints were also in sporadic operation in the Roman East, most notably at Antioch.Footnote 7 The large bulk of Severan imperial coinage, however, was struck at Rome. Imperial coins were designed and struck under the authority of the emperor as a monument of his regime, and should be differentiated from provincial coins, which were struck by local cities with imagery that reflected local culture and concerns.Footnote 8 A theme of provincial coinage was the relationship of the city and its inhabitants with the ruling power, entailing the representation of the emperor and his family. Though these representations were no doubt created within a framework acceptable to the emperor, they are best viewed as local monuments, akin to the arches, reliefs, inscriptions and other media erected by the cities and citizens of the empire. Since the purpose of this study is to focus on material authored by the regime in order to gain a better understanding of the public image of the empresses, provincial coin types are not considered here.

An examination of the numismatic representation of imperial women invites a consideration of who was responsible for the designs and motifs that graced their coinage. This is connected to the on-going discussion of the extent to which the emperor was responsible for the selection of his coin types. The bibliography on this subject is large, but in the study of the public image of the emperor somewhat irrelevant: as Metcalf has observed, it is obvious that the coin designs were flattering to the emperor and subject to his approval, and were considered by the inhabitants of the empire to be the product and responsibility of the emperor himself.Footnote 9 The potential role of the imperial women in the selection of coin types is trickier still, given the absence of evidence. But this very absence may be significant: although there are numerous instances of ancient authors connecting an emperor and his coin imagery, to my knowledge none connect the empress and her coin types, suggesting that the women concerned had little or no role in type selection (at least in the public mind-set). That the public images of empresses generated by their coinage largely conforms to and enhances the public ideology of the emperor supports this hypothesis (see the example of the changing numismatic image of Julia Domna under Severus and Caracalla, below, pp. 249–56).

However, to envisage a uniform situation is dangerous. Different emperors may have had different levels of involvement in their numismatic image, and likewise differing situations in the imperial family may have resulted in some imperial women being able to influence their numismatic image in a way others could not. Here the age of the ruling emperor may be significant: a young emperor likely meant that a greater influence was granted to the imperial women or to the consilium. In the Severan period, it is precisely at the moment when a young emperor (Elagabalus) assumes the throne that the numismatic images of the imperial women give the suggestion of individuality. Thus, although in general it is unlikely that imperial women had any significant influence on their numismatic image, we cannot exclude the possibility that some individuals did not conform to the general norm.

Though the coin types of the Severan women have been subjected to a type-by-type analysis, the numismatic images of the empresses have not been examined yet from a quantitative perspective. The results of such a study are revealing, and allow us to form a more accurate idea of the public image of each empress. A quantitative numismatic analysis reveals continuity between the imagery of the Severan women, but also highlights points of difference, particularly during the rule of Elagabalus.

The validity of using coin hoards to establish the relative frequency of different reverse types has been demonstrated elsewhere.Footnote 10 Though every coin type struck for a ruler was significant, since it consciously joined the portrait of an emperor or empress with a particular idea, deity or event, different coin types were struck in different quantities. Identifying which images formed ‘significant’ issues (commonly associated with a ruler) and which images formed ‘commemorative’ or small issues enables us to understand the overall associations and communicative messages of a ruler's coinage. In this endeavour coin hoards are a valuable tool, since they largely represent a sample of the currency in use at a particular period in time.

Duncan-Jones's analysis of coin hoards has revealed that before the reign of Hadrian, only small amounts of coinage were struck with the portrait of the empresses.Footnote 11 Livia, for example, has no presence on Augustus's coinage: her name first appears on two sestertii issues struck under Tiberius in ad 22–3, and her portrait first appears on a dupondius with the legend SALVS AVGVSTA around the same period.Footnote 12 The first imperial woman to appear on the obverse of an imperial coin, with an identifying legend, is Agrippina I, on an issue struck after her death (RIC 12 55).Footnote 13 Agrippina II continued the growth in the visibility of imperial women on coinage, but coinage struck for the empresses did not reach significant numbers in terms of quantity before the rule of Hadrian.Footnote 14

From Hadrian's decennalia, however, an increased quantity of coinage was struck for the emperor's wife Sabina, and from this point female coinage became a regular occurrence. This new production template at the mint, at a time when imperial succession occurred through adoption, communicated the idea of continuity within the imperial domus. Sabina also appears in public reliefs, the first empress to do so since the Augustan age.Footnote 15 The proportion of coinage struck for imperial women rises again under Antoninus Pius, who struck an extraordinary number of coins for his deified wife Faustina I. This increased visibility of imperial women continues under Marcus Aurelius and Faustina II.Footnote 16 An analysis of Severan coinage reveals that the proportion of coinage struck for the empresses remains constant, at least on silver, in the period ad 193–235. After the dramatic increases of Hadrian and the Antonines, the presence of the empresses on coinage had been established.

Ideally, a quantitative analysis of coin types would examine coins struck in gold, silver and aes metals. However, the paucity of well-recorded gold finds from the Severan period and the small amount of aes types struck by these emperors means that an analysis can be performed only on silver coinage.Footnote 17 None the less, the results of a sample of 56 hoards from diverse geographical areas, containing 67,151 coins struck in the Severan period, are revealing.Footnote 18 The results show a significant presence of coins struck in the names of Julia Domna, Julia Maesa and Julia Mamaea (Table 1), and, to a lesser extent, Julia Soaemias. Plautilla, Julia Paula, Aquilia Severa, Annia Faustina and Orbiana constitute a significantly smaller percentage. The proportions given in Table 1 are for the entire silver monetary output of each reign; a year-by-year analysis would also be revealing, but, since many Severan coins have not been dated to a specific year, such an analysis proves impossible when examining the dynasty as a whole. Consequently, the smaller percentages present for Plautilla, the wives of Elagabalus and for Orbiana are at first glance somewhat misleading: coinage was only struck for these individuals for a very short period. During the years these coins were struck they might have formed a far more significant proportion of the currency, but without more specific dating for Severan coinage we cannot estimate what this percentage might have been. None the less, from this larger perspective we are able to gauge what image was conveyed by an emperor's coinage in its entirety.

Table 1. Relative quantitites of Severan silver portrait types as suggested by the hoard evidence.

* percentages are rounded up to the nearest whole number

The surprisingly similar proportions of silver coinage struck for Julia Domna under Septimius Severus (17%), Domna under Caracalla (18%), Julia Maesa (18%) and Julia Mamaea (17%) is suggestive of a workshop or officina within the imperial mint that was responsible for producing types for these women. This hypothesis has existed for some time; it is suggested that each of the officinae within the mint was given a particular reverse type to strike. This acted as an identifier of the workshop, and thus formed a mechanism of quality control.Footnote 19 Though it is not known for certain, six workshops have been suggested for the mint in Rome in this period. From ad 248 the workshops within the mint began to sign their products with Greek numerals. From this we can deduce that there were six workshops at this time, one striking coinage exclusively for Philip's wife, Octacilia.Footnote 20 The model has been a guide to understanding the operation of the mint in earlier periods. If one workshop was dedicated to striking coins for the empresses in the Severan period, then one would expect that a sixth of silver coinage, or 16–17%, would bear the empress's portrait, as is the case here. The quantitative evidence seems to demonstrate the fact that at least one of the six workshops was dedicated to striking coinage for the empresses.

The hoards contained far less coinage struck in the name of the later imperial wives, and only 7% of Elagabalus's silver coinage was struck in the name of Elagabalus's mother, Julia Soaemias. No coins at all were found for Elagabalus's third wife, Annia Faustina. The problem of Soaemias's coinage will be returned to below (pp. 261–5). For Annia Faustina and the other imperial wives, their small numismatic presence likely reflects the fact that their marriages only lasted for a short period of time, in the case of Annia Faustina just a few months.

The very brief marriages of the later Severan emperors, in addition to the fact that no direct imperial heir was produced after Caracalla and Geta, resulted in a significant visual presence of the mothers and grandmothers of the Severan emperors: Julia Domna and her female relatives came to form the blood lineage of the dynasty. Domna lived into the rule of her son Caracalla, forming a living link between one ruler and the next. After the death of Caracalla, it was Domna's sister, Julia Maesa, who could claim a direct blood link. Caracalla's praetorian prefect Macrinus ruled for a brief period before being overthrown in favour of Julia Maesa's grandson Elagabalus. In fact, Elagabalus was touted as the biological son of Caracalla.Footnote 21 The claim was undoubtedly false, but the story, in addition to Elagabalus's early portraiture (which consciously recalled Caracalla) underscores the importance of a blood link in the accessions of this period. The youth of the emperors involved (Elagabalus was only fourteen when he came to power, as was Severus Alexander) would only have strengthened the importance of the dynastic connection.Footnote 22 After Elagabalus's overthrow, his cousin, Severus Alexander, replaced him. Maesa survived into Alexander's reign for a short period, and her daughter, Julia Mamaea (Alexander's mother), appears on the imperial coinage.

The fact that the Severan dynasty was connected through the female line meant a significant presence of empresses on the imperial coinage, underscoring the domus divina and the continuity of the regime. But what images and associations did this coinage convey? An analysis of the particular types, and their relative frequencies, reveals that the Severan imperial women extended imperial ideology in a manner that underscored continuity with the past. But there are also significant differences between the numismatic image of the different empresses, reflecting the fact that their public associations and their public role subtly changed from emperor to emperor, in keeping with the shifting ideology of the Severan period.

THE NUMISMATIC IMAGE OF JULIA DOMNA DURING THE REIGN OF SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS (ad 193–211)

Julia Domna appears in a large number of inscriptions and dedications, and received many honorary titles in her lifetime and after.Footnote 23 The significant amount of surviving material relating to her no doubt reflects the length of time she was associated with the imperial house (some 24 years), but perhaps also the increased output of inscriptions and provincial coinage in the Severan period.Footnote 24 Remarkably, Domna's name appears on milestones, an honour never before given to an imperial woman.Footnote 25 She also had a role in the rites associated with the celebration of the saecular games in ad 204, and is shown with the rest of the imperial family on the reliefs of the gate of the argentarii, and on the arch in Lepcis Magna.Footnote 26 Dio records that Caracalla trusted her with the imperial correspondence.Footnote 27 An inscription in Ephesus preserves the empress's response to a petition by the city, recording her pledge that she would work on behalf of the city with her ‘sweetest son’.Footnote 28 The textual evidence of the period casts her as a patroness of philosophers and rhetors. This is most notable in the works of Philostratus, who states that Domna commissioned the Life of Apollonius of Tyana, and who wrote a letter addressed to her concerning Plutarch.Footnote 29 Dio records that Domna turned to philosophy as a consolation for her treatment by Severus's praetorian prefect Plautianus, but her continued patronage of philosophers after Plautianus's fall from power suggests a real and abiding interest.Footnote 30 Philostratus records an example of the empress acting as a patroness, securing the chair of rhetoric at Athens for Philiscus.Footnote 31 From this array of evidence one can begin to gauge the varying roles and associations the empress had in the Severan dynasty.

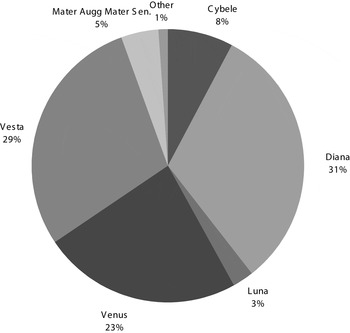

An analysis of Domna's coin types provides another perspective on her role in the dynasty, and highlights her changing public image from Severus to Caracalla. In the hoard sample 5,525 identifiable coins were found struck with Domna's portrait during Septimius's reign (ad 193–211). The breakdown of the reverse types on this coinage can be seen in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Reverse silver types of Julia Domna during the reign of Severus (no. = 5,525).

The overall impression given by the coinage is one of diversity. Domna is associated with a variety of goddesses, but also with the felicity of Severus's rule, communicated through types of Fortuna, Hilaritas and Laetitia. The largest proportion of Domna's silver coinage is made up of Pietas types (18%). This is the result of a single type struck in extremely large quantities (RIC 574; with 618 examples in the hoard sample). The type has the legend PIETAS PVBLICA and an image of Pietas with both arms raised in front of an altar (Fig. 2). Hill dated this coin type to the period of Plautianus's ascendancy, ad 204. Few other coin types were struck for Domna in this period, and this has been interpreted as a loss of status for Domna as a result of Plautianus's intrigues.Footnote 32 Yet the quantitative perspective demonstrates that although only a few types were being struck for Domna, this does not necessarily mean that fewer coins were being struck for her, or that she suffered a drop in status.

Fig. 2. Denarius of Julia Domna showing Pietas with raised arms (RIC 574). (Reproduced courtesy of the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.; http://www.cngcoins.com .)

A similar Pietas type, showing Pietas dropping incense onto an altar and holding a box with the legend PIETAS AVGG (RIC 572), was struck in significant quantities also for Domna (390 examples). The epithet AVGG likely refers to Caracalla and Severus, and Domna's role as the wife and mother of the ruling emperors. This connection between the concept of Pietas and Domna's role in the imperial family is visualized on an aes type struck for Domna, which portrays Julia Domna standing frontally, with Severus and Caracalla on either side, accompanied by the legend PIETATI AVGVSTAE (RIC 864, 866).

Other significant coin types associated with Domna (with more than 200 occurrences) are Diana Lucifera (RIC 548 — 231 examples), Hilaritas with two small figures (likely representing Caracalla and Geta, RIC 557 — 242 examples), Juno (RIC 559 and 560 — 267 and 261 examples respectively), a coin type showing Cybele on a throne with the legend MATER DEVM (RIC 564 — 382 examples), Pudicitia (RIC 576 — 263 examples), an image identified by Mattingly as Isis and Horus with the legend SAECVLI FELICITAS (RIC 577 — 401 examples), a Venus Felix type (RIC 580 — 437 examples) and an image of Vesta with the legend VESTAE SANCTAE (RIC 587 — 326 examples). This last type probably commemorates Domna's patronage of the restoration of the sanctuary of the Vestals after fire severely damaged the structure under Commodus.Footnote 33

Domna's coinage visualizes her role as a traditional Roman empress. She is associated with the traditional Roman goddesses Juno, Venus and Diana, is seen as an embodiment of sexual virtue, and is shown contributing to the joy of the age through her role as mother to the heirs apparent. The Cybele type may seem unusual at first glance, but it had been struck for empresses since the time of Faustina I, and its appearance here underlined the connection between the Severan and Antonine dynasties.Footnote 34

The Isis type is more unusual and warrants closer investigation (Fig. 3).Footnote 35 Apart from the fact that the female figure is offering her breast to a young child, there is nothing to indicate to the viewer that the figures are Isis and Horus. The legend on this coin, SAECVLI FELICITAS, had been used under Marcus Aurelius to communicate the continuation of the dynasty, an idea also communicated by this image. Coins struck for Faustina II with the legend SAECVLI FELICITAS show two children seated on a throne, presumably meant to represent Commodus and Antoninus (RIC 509, 709–12, 1665–6). On coins struck for Septimius Severus, the legend was employed with a crescent and seven stars (associated with eternity), and with the portraits of Domna, Geta and Caracalla (RIC 159, 175, 181, 360, 416–18B, 513). On Severus's aes coinage the legend SAECVLI FELICITAS is accompanied by an image of Felicitas with her foot on a prow, holding a caduceus and cornucopiae (RIC 692, 698, 710–11). The imagery on Domna's coin does not show the typical Isis lactans seated with Horus; rather, a female figure stands holding a child with her foot on a prow, with an altar and rudder behind her.Footnote 36 The image may have been meant as an allusion to Fortuna (who is commonly portrayed with a rudder), or some sort of Isis-Fortuna.Footnote 37 This suggestion is strengthened by the fact that one of Domna's other coin types shows a seated Fortuna holding a cornucopia and rudder with a child at her feet, accompanied by the legend FORTVNAE FELICI (RIC 552–4, 854, 875–6). The common attributes between Domna's ‘Isis’ type, the coins of Severus showing Felicitas with a prow, and Domna's types showing Fortuna with a rudder and child, suggest that an identification of the image as Isis may be too simplistic.

Fig. 3. Denarius of Julia Domna showing a female goddess breastfeeding a child (RIC 577). (Reproduced courtesy of the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.; http://www.cngcoins.com .)

Coin types that have formed the focus of modern discussions on the public image of Julia Domna have little or no representation in the hoard sample. The reverse types highlighting Domna's position as mater castrorum, for example, have only a small presence.Footnote 38 Thus, while Domna's assumption of this title has attracted considerable modern focus, and it was commonly given to the empress in Greek and Latin inscriptions, the official silver coinage of the Empire did not emphasize the position.Footnote 39 A coin type showing Cybele in a chariot with the legend MATER AVGG had only nineteen occurrences (RIC 562). Though this image closely associates Domna with Cybele, the small number of examples found in the archaeological record argues for caution in interpretation of the type: these coins may have been struck with specific recipients in mind, or on a specific occasion.Footnote 40 The series of coins highlighting the imperial family with Domna on the obverse and Severus, Caracalla and Geta on the reverse in a variety of combinations, had only two occurrences (RIC 539–45).Footnote 41 Again, the coins may have been struck for a specific occasion.

Domna's varied numismatic image during the reign of Septimius Severus reflects the fact that Severus himself utilized an array of ideologies to justify and sanction his new dynasty. Underscoring the connection to Severus's adopted family, the Antonines, Domna is connected with deities and ideals that already had been motifs on the coinage of Faustina the Elder and Faustina the Younger. That Domna's image was defined largely by Severus's own ideologies becomes apparent when we consider the transformation of her coin types under the sole rule of her son Caracalla.

JULIA DOMNA'S NUMISMATIC IMAGE UNDER THE SOLE REIGN OF CARACALLA (ad 211–17)

Severus died in ad 211 in York and was succeeded by his sons, Caracalla and Geta. Caracalla killed his brother by December of this year, and from that point ruled alone.Footnote 42 The accession of a new emperor resulted in a change in the official image of the princeps. Severus had utilized an array of different imagery on his coin types, above all the idea of military victory. Victory types form 21% of Severus's silver coin types according to the data gathered from the hoard sample.Footnote 43 During Caracalla's sole rule, however, military types form a mere 2% of the emperor's silver coinage, and instead deities come to have an increasing association with the emperor.Footnote 44 The hoard evidence suggests that 21% of Severus's silver coinage displayed deities, whereas under Caracalla's sole rule this proportion rises to 59%. During Caracalla's co-rule with his father the divine types on his coinage included Mars, Minerva and Sol, but during his sole rule the divine repertoire expanded, constituting Venus, Sol, Jupiter, Mars, Apollo, Aesculapius, Sarapis and Hercules.Footnote 45 Thus in terms of sheer quantity, and in variety, deities gained a greater presence on the emperor's coinage under Caracalla.

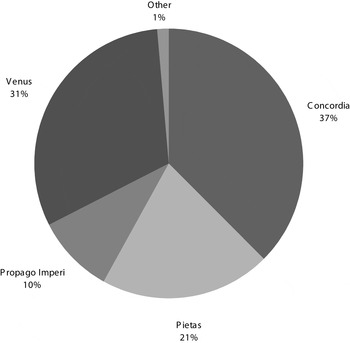

This change in the imperial image is reflected also in the coinage of Julia Domna: her coin types come to have an almost exclusive focus on the divine (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Reverse silver types of Julia Domna during the reign of Caracalla (no. = 1,110).

Under Severus, Domna's coinage had a variety of types struck in significant quantities. During the rule of her son, however, Domna's silver coinage focuses on Vesta, Venus and Diana. The single largest type struck for Domna in this period was an issue showing Diana holding a torch with the legend DIANA LVCIFERA (RIC 373A — 353 examples) (Fig. 5). The same type had been struck for Domna under Septimius Severus (RIC 548, 851, 871). The image thus communicated continuity with the previous regime. The connection of Domna with the virgin goddesses Diana and Vesta also may have been a conscious decision after the death of Geta. The portrayal of the empress as a mother may have been thought too awkward after the death of one of her sons.

Fig. 5. Denarius of Julia Domna showing Diana holding a torch (RIC 373A). (Reproduced courtesy of the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.; http://www.cngcoins.com .)

After the death of Severus, Domna's obverse titulature changes from Iulia Augusta to Iulia Pia Felix Augusta. Domna appears on coinage as mater augusti, mater senatus and mater patriae, the latter being an innovation on the traditional imperial title pater patriae. The date of these titles is debated; they may have been bestowed after the death of Plautianus, but they only appear on coinage after the death of Severus and before the death of Geta (the double ‘G’ of the AVGG legend indicating that both of Domna's sons were alive).Footnote 46 The abandonment of the mater augusti type after Geta's death (suggested by the fact that no issues survive that give the title MAT. AVG), again suggests that the public image of Domna as a mother may have become too loaded in Caracalla's sole rule. The MATER AVGG coin types appear to have been struck in small, but none the less significant, quantities. Twenty-four examples of this type (RIC 380) were found in the hoard sample, with a reverse type showing Domna standing, holding branch and sceptre, and 28 examples of RIC 381 were uncovered, a variety in type that shows Domna seated. These numbers become more impressive when one considers they all must have been struck in the first few months after Severus's death, while Geta was alive.

The Vesta types (RIC 390–1), which constitute about 29% of Domna's silver coins under Caracalla, continue the close association of Domna to the Vestals seen under Severus. Unlike Severus, Caracalla also associated himself with the restoration of the temple: two gold coins were struck for the emperor showing him sacrificing in front of the structure (RIC 249–50). Venus Genetrix types continue from the rule of Severus.Footnote 47 Venus Victrix types, however, do not continue under Caracalla.Footnote 48 This again might be attributed to the shift in imperial ideology from an emphasis on military prowess to one that highlighted divine support. The Cybele type, with the legend MATRI DEVM, can be seen also as a continuation from Severus's principate, though these types constitute only 8% of Domna's coinage. The image of the emperor changed significantly under Caracalla, and Domna's types were able to communicate continuity with the previous ruler while enhancing and supporting the new ideology of power.

THE NUMISMATIC IMAGE OF PLAUTILLA (ad 202–5)

In ad 202, Caracalla married Plautilla, the daughter of Severus's praetorian prefect Plautianus.Footnote 49 After the downfall of her father in ad 205, Plautilla was sent into exile; Dio records that she was put to death when Caracalla became sole ruler.Footnote 50

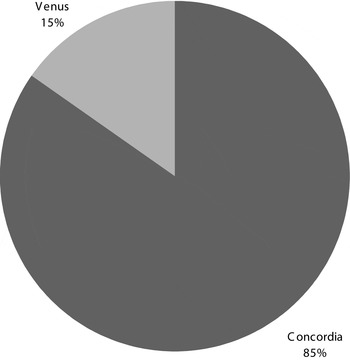

Plautilla's coin types have an emphasis on Venus and Pietas, similar to the coins of Julia Domna, but also underscore the idea of Concordia and the continuation of the dynasty (Fig. 6). The Pietas type of Plautilla is subtly different from that of her mother-in-law. Though the legend on the coin, PIETAS AVGG, is also seen on the coinage of Domna, it is accompanied by an image of Pietas holding a sceptre and child, a reference to Plautilla's role as the mother of future emperors, and perhaps a reference to a daughter she may have borne to Caracalla (RIC 367).Footnote 51 The Venus types of Plautilla in the hoard analysis are all of the Venus Victrix type (RIC 369), similar to the type seen for Domna under Severus and part of the military ideology that characterized Severus's principate (Fig. 7). With 311 examples in the hoard sample, this type was the largest struck for Plautilla.

Fig. 6. Reverse silver types of Plautilla (no. = 1,006).

Fig. 7. Denarius of Plautilla showing Venus Victrix (RIC 369). (Reproduced courtesy of the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.; http://www.cngcoins.com .)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the idea of Concordia constitutes the majority of Plautilla's silver types (37%). This idea was expressed with several images and legends. Two issues were released with the legend CONCORDIA AVGG and an image of Concordia standing, holding a patera and sceptre (RIC 359 — 31 examples; RIC 363 — 156 examples). A variation showed Concordia seated with a patera and cornucopiae.Footnote 52 That these Concordia types were to celebrate the marriage of Plautilla and Caracalla is evident from the third type, which showed Caracalla and Plautilla grasping hands with the legends CONCORDIAE AETERNAE (RIC 361 — 94 examples), and CONCORDIA FELIX (RIC 365 — 35 examples). This same image was accompanied by the legend PROPAGO IMPERI, an issue that constituted 10% of Plautilla's silver types (RIC 362 — 96 examples). The image of Plautilla and Caracalla shaking hands was displayed also on several provincial coin types.Footnote 53 One imagines that if Plautilla had remained married for longer, her image might have become more diverse. But Caracalla's marriage, and those of the remaining Severan emperors, was short. Consequently Plautilla's coinage, along with that of her successors, has an overwhelming emphasis on Concordia.

THE NUMISMATIC IMAGE OF JULIA PAULA (ad 219–20)

Julia Paula, of the Cornelian gens, was married to the Emperor Elagabalus in ad 219. Her marriage was short-lived, ending in ad 220 so that Elagabalus could marry the Vestal Virgin Aquilia Severa.Footnote 54 The small amount of coinage that was struck for Paula in this period understandably emphasizes the imperial marriage (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Reverse silver types of Julia Paula (no. = 427).

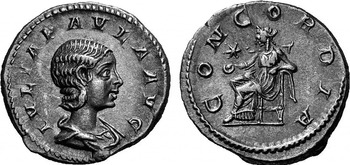

More so than for Plautilla, Concordia forms a focus, but Paula's marriage was even shorter than Plautilla's three years. The gold types of Julia Paula also focus on the theme of Concordia, and were likely struck on the occasion of the emperor's marriage.Footnote 55 The largest silver type of Paula in the hoard sample was RIC 211 (323 examples), with a reverse type showing a seated Concordia holding a patera, with a star in the field (Fig. 9). Coin types showing Elagabalus and Julia Paula clasping hands with the legend CONCORDIA were also present in the hoard sample (RIC 214 — fifteen examples), as was a type showing a seated Concordia holding patera and double cornucopiae with the legend CONCORDIA AVGG (RIC 216 — 24 examples). The Venus examples of Paula were all of the same type, Venus seated holding a globe and sceptre with the accompanying legend VENVS GENETRIX (RIC 222). Venus Genetrix had also appeared on the coinage of Domna and Plautilla. No other types were found for the empress in the silver hoard sample.

Fig. 9. Denarius of Julia Paula showing Concordia (RIC 211). (Reproduced courtesy of Numismatik Lanz, Munich/Dr Hubert Lanz.)

THE NUMISMATIC IMAGE OF AQUILIA SEVERA (ad 220–2)

Elagabalus married the Vestal Virgin Aquilia Severa in ad 220, divorced her in favour of Annia Faustina in ad 221, and then remarried her later that year.Footnote 56 The empress's silver coinage in the hoard sample has an almost exclusive focus on the idea of Concordia (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Reverse silver types of Aquilia Severa (no. = 141).

The large proportion of Concordia types is largely the result of a single issue showing Concordia seated, holding a patera and double cornucopiae with the legend CONCORDIA and a star in the field (Fig. 11).Footnote 57 A Concordia type also was released showing Elagabalus and Aquilia Severa with clasped hands (RIC 228), but this had only five examples in the sample. Only one other type of Severa was uncovered, a coin showing Laetitia holding a wreath and a rudder resting on a globe with the legend LAETITIA (RIC 229 — one example).

Fig. 11. Denarius of Aquilia Severa showing Concordia (RIC 225). NAC Auction 42 (20 November 2007) lot 149. (Reproduced courtesy of Numismatica Ars Classica NAC AG.)

Dio and Herodian record that Elagabalus justified his marriage to the Vestal Aquilia by stating that a union between a priest and priestess was sacred, and would result in ‘godlike’ children.Footnote 58 From this statement some have postulated that Elagabalus was attempting to alter the nature of the Roman principate, instituting the rule of a high priest and high priestess, who would give birth to the next generation of priest rulers.Footnote 59 One must remain cautious of this interpretation in view of Aquilia's coin types. If the emperor or his advisers intended to alter the Roman principate by instituting a new priestly government, this was not communicated actively on the imperial coinage. Instead, in terms of numismatic iconography, Aquilia looks remarkably similar to her predecessor.

No coins struck for Elagabalus's third wife, Annia Faustina, were found in the hoard sample. Considering that only one silver type is known for her (RIC 232), this result is not surprising. Still, this small number suggests that this particular marriage was not marked or celebrated by a large emission of coinage. Since this was the third marriage of the emperor in as many years, the celebration of the event may have been circumspect.

THE NUMISMATIC IMAGE OF JULIA SOAEMIAS (ad 218–22)

The numismatic images of Julia Paula and Aquilia Severa might be understood by their very brief association with the imperial family. The same cannot be said for the coinage of Elagabalus's mother, Julia Soaemias. Both Julia Soaemias and her mother, Julia Maesa, had been in Rome during the rule of Septimius Severus, and thus both had first-hand experience of court life.Footnote 60 Soaemias had participated in the saecular games celebrated in ad 204 with other wives of equestrian rank.Footnote 61 Quantitative analysis of Soemias's silver types reveals an almost exclusive focus on Venus Caelestis, an incarnation of Venus never seen before on Roman imperial coinage (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Reverse silver types of Julia Soaemias (no. = 619).

The Venus Caelestis types have two differing iconographies. One portrays Venus standing, holding an apple and sceptre (sometimes with a star in the field), with the legend VENVS CAELESTIS (RIC 241 — 357 examples). The other type also has the legend VENVS CAELESTIS, but here Venus is seated holding an apple and sceptre with a child at her feet (RIC 243 — 442 examples) (Fig. 13). The latter image may have been intended to communicate Soaemias's role as the mother of the Augustus. The Juno types that constitute 3% of Soaemias's silver coinage are all of the IVNO REGINA type (RIC 237 — sixteen examples).

Fig. 13. Denarius of Julia Soaemias showing Venus (RIC 243). NAC Auction 39 (16 May 2007) lot 144. (Reproduced courtesy of Numismatica Ars Classica NAC AG.)

‘Caelestis’ or ‘heavenly’ is a known, if uncommon, epithet of Venus in inscriptions, but is not otherwise known on Roman imperial coinage.Footnote 62 Venus standing with an apple and sceptre is a common image on imperial coinage, as is a seated Venus (Fig. 13). Seated Venus types with Cupid in front, for example, had been struck for Julia Domna, with the legend VENVS GENETRIX, and seated Venus Gentrix types had been issued for Plautilla and Julia Paula (see above, pp. 256–8, 259).Footnote 63 The innovation of this type, then, is in the legend. Indeed, if the seated Venus Caelestis types were being struck for Soaemias at the same time as Julia Paula's seated Venus Genetrix types, then the viewer would have been presented with almost identical images that could be differentiated only through the legend. The viewer might have blurred different female figures. Indeed, that the only alteration is in the legend suggests that this coin type (and others) were intended to be viewed in a precise and technical manner. The introduction of this new legend, and the fact that Venus Caelestis forms almost the entire numismatic image of Soaemias, calls for explanation.

In the British Museum Catalogue, Mattingly suggested that what is shown on Soaemias's coinage is the Carthaginian goddess Ourania, whom Dio and Herodian record was married to the cultic stone Elagabal.Footnote 64 Since the image forms such a large proportion of Soaemias's silver types, one imagines that it was struck for the empress from the beginning of Elagabalus's reign, before the marriage of the god took place. However, the smaller than usual proportion of silver types struck for Soaemias during Elagabalus's reign (only 7% compared to the normal 16–17% for other imperial woman) (Table 1), may mean that coinage was struck for Soaemias only for part of her son's rule, perhaps after the marriage of the god Elagabal to Ourania.Footnote 65 An alternative avenue of interpretation is to see the Venus Caelestis type as an interpretatio romana of an Emesene goddess, an idea also suggested by Mattingly.Footnote 66 An Aphrodite figure did exist in the Emesene pantheon, though given the paucity of material evidence from the city it is difficult to reconstruct Emesa and its culture with any certainty.Footnote 67

The Venus Caelestis type only occurs on the coins of Soaemias, and not on the coinage of other imperial women during Elagabalus's rule.Footnote 68 Since Dio and Herodian draw explicit parallels between the marriages of the emperor and the marriages of his cultic stone, some have suggested that the marriage of the god Elagabal was mirrored in the emperor's own marriages, a hieros gamos.Footnote 69 However, we should not accept the literary tradition surrounding the emperor at face value. The same hostile tradition that gave the emperor the nickname Elagabalus, closely aligning the emperor and his god, no doubt also resulted in an alignment between the marriages of the emperor and the marriages of the god, reflected in Herodian's erroneous tale that the god Elagabal also married the Roman palladium (no doubt invented from the fact that the emperor had married a Vestal Virgin).Footnote 70 The fact that the new goddess Venus Caelestis only appears on the coins of Elagabalus's mother also should suggest caution before any interpretation of hieros gamos. Even here, the numismatic imagery does not confirm an identification of the goddess as Ourania/Dea Caelestis. Given the new epithet of Venus, a connection with the cultic practices of the god Elagabal is likely, but what precise connection with the cult Soaemias's coinage communicated remains uncertain.

Another peculiarity is that though Soaemias's silver coinage has an almost exclusive focus, this was not the case for the emperor himself. Though a significant proportion of the emperor's coinage showed the emperor as high priest of the god Elagabal, very few coins were found in the hoard sample that displayed the Emesene stone itself, and overall the emperor's types had a variety of images and themes.Footnote 71 While Domna is given the title ‘mother of the emperors’, and later in the Severan dynasty Mamaea appears on medallions alongside her son as mater augusti, Soaemias's coinage neglects this maternal role, except for (perhaps) the addition of the child to the image of the seated Venus Caelestis.Footnote 72

The precise connotations intended by the Venus Caelestis coin type, and Soaemias's entire numismatic image, then, remain elusive. Apart from the epithet of Caelestis, the association of the empress with Venus can be seen as a continuation of the coinage of the earlier Severan empresses. But the legend VENVS CAELESTIS is not seen before or after Elagabalus's reign on imperial coinage,Footnote 73 and one must then conclude that it likely had some connection with the Emesene cult that rose to prominence during these years. If so, Soaemias was connected very publicly with the cultic activities of Elagabalus, an idea that is confirmed when one examines the coinage of Soaemias's mother, Julia Maesa.

THE NUMISMATIC IMAGE OF JULIA MAESA (ad 218–22)

In epigraphic evidence Julia Maesa is represented in a similar manner to Julia Domna, described as mater castrorum and mater senatus, though it is not known whether these titles were official.Footnote 74 Her numismatic image differs significantly from that of her daughter, and possesses no hint of the Emesene cult that defined the principate in this period (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. Reverse silver types of Julia Maesa (no. = 2,220).

The largest proportion of Maesa's coinage is made up of Pudicitia types, communicating sexual virtue.Footnote 75 This is the result of a single type struck in very large quantities, which shows Pudicitia seated, raising her veil and holding a sceptre, with the legend PVDICITIA (RIC 268 — 990 examples) (Fig. 15). Another large issue struck for Maesa emphasized the good fortune of the age, with Felicitas holding a caduceus and sacrificing over an altar with the legend SAECVLI FELICITAS (RIC 271 — 570 examples). Pietas forms another major theme, with one issue in particular struck in large numbers, showing Pietas sacrificing over an altar while holding an incense box (RIC 263 — 222 examples). Juno also has a significant showing on the empress's coinage, shown holding a patera and sceptre with the legend IVNO (RIC 254 — 143 examples). Another major issue carries the legend FECVNDITAS AVG and shows Fecunditas with a child and cornucopiae (RIC 249 — 137 examples).

Fig. 15. Denarius of Julia Maesa showing Pudicitia (RIC 268). (Reproduced courtesy of the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.; http://www.cngcoins.com .)

The overall impression is of a virtuous, traditional empress. The radical difference between the coinage of Julia Maesa and that of her daughter Soaemias is reminiscent of their differing portrayals in the account of Herodian, whose history gives Julia Maesa a significant role in the running of the Empire.Footnote 76 The author presents Maesa as the moderating influence on Elagabalus's excesses: she worries about his eastern dress (5.5.5), she is concerned about the soldiers' reaction to Elagabalus's activities and persuades him to adopt Alexander as Caesar (5.7.1–2); she prevents Elagabalus's plans to murder Alexander (5.8.3), and then survives to influence the reign of Alexander (5.8.10). Soaemias is mentioned rarely in Herodian's account, except at the end when she is killed with her son. Herodian records that both their bodies were mutilated and dragged through Rome before being thrown into the sewers (5.8.8–9). It may be that Herodian was inspired by the different public images of Maesa and Soaemias, demonstrated here in the numismatic evidence, to cast them in these roles in his account.

Whatever Herodian's portrayal of events, it is historical fact that Maesa survived into the reign of Severus Alexander, whereas Soaemias's body was dragged through the streets, the only empress to suffer this form of public abuse.Footnote 77 Popular perception must have held that Soaemias was deeply involved in Elagabalus's outrages, whereas Maesa escaped reproach.Footnote 78 Did the differing public images of these women, suggested by the numismatic evidence, affect this perception? And do the differing numismatic images of Maesa and Soaemias reflect a real difference of ideology between the women? As discussed above, it seems unlikely that the imperial women had any direct voice in their numismatic image. Levick has observed that it is difficult to imagine anything beyond informal consultation.Footnote 79 We are left with two possible interpretations. Julia Maesa's image may have formed part of an overall imperial ideology that highlighted the continuation of Roman traditions alongside the introduction of the new Emesene cult (communicated on the coinage of Elagabalus and Soaemias). Or, the differing images of Maesa and Soaemias might reflect their different roles and ideas in the reign of Elagabalus. A difference of opinion between the empresses may have been communicated directly to the Roman mint, or the mint workers responded on their own initiative with a sophisticated and nuanced understanding of the imperial family and its activities (monetales, after all, were appointed directly by the emperor himself).Footnote 80 The reign of Elagabalus in many ways is a break from the norms associated with the principate; we should not be surprised to find the public image of the imperial women is also different.

THE NUMISMATIC IMAGE OF JULIA MAMAEA (ad 222–35)

Julia Maesa did not survive long into Severus Alexander's rule, and was deified.Footnote 81 Alexander's reign emphasized restoration and renewal after Elagabalus.Footnote 82 The emperor's mother, Julia Mamaea, is granted honours similar to Julia Domna. Mamaea appears on milestones, is associated with building projects in Rome, and receives the title mater castrorum.Footnote 83 Like Domna, it appears that Mamaea had contact with rhetors and philosophers. Eusebius records that the empress summoned the Christian author Origen to the court while she was at Antioch, and the empress was likely also addressed by Hippolytus.Footnote 84 A quantitative analysis of Mamaea's silver types also reveals a close association with Julia Domna (Fig. 16).

Fig. 16. Reverse silver types of Julia Mamaea (no. = 2,571).

The largest proportion of Mamaea's silver coinage displays the goddess Juno. The vast majority of these types is of Juno Conservatrix, showing Juno holding a patera and sceptre with a peacock at her feet and the legend IVNO CONSERVATRIX (RIC 343 — 789 examples) (Fig. 17). Alexander Severus's own coin types have a significant emphasis on Jupiter Conservator at the beginning of his reign, and then again during the Persian Wars.Footnote 85 Carson placed Mamaea's Juno Conservatrix issues at the beginning of Alexander's reign, in ad 222.Footnote 86 Thus the emphasis on Juno would have occurred immediately after Elagabalus's downfall, with the epithet Conservatrix communicating Alexander's escape from his murderous cousin Elagabalus, and the restoration of traditional Roman cultic practices.Footnote 87 A smaller number of types were struck showing Juno seated holding a flower and swathed infant with the legend IVNO AVGVSTAE (RIC 341 — 58 examples).

Fig. 17. Denarius of Julia Mamaea showing Juno (RIC 343). © Lübke & Wiedemann KG, Stuttgart. (Reproduced courtesy of Lübke & Wiedemann KG, Stuttgart and Gorny & Mosch, Munich.)

A significant proportion of Mamaea's silver coinage also displayed Vesta types. Although Vesta types are known to exist for the imperial women under Elagabalus, and are listed in Roman Imperial Coinage, no examples of these types were found in the hoard sample, suggesting that any Vesta types under Elagabalus were struck in very small quantities.Footnote 88 Thus the return to a significant quantity of Vesta types under Severus Alexander makes a public statement: not only does it tie Mamaea to the patronage of the Vesta cult given by Julia Domna, but it underscores the return of the sacrosanct nature of the cult and its priestesses, which had been violated by Elagabalus. Two different types of Vesta imagery formed the bulk of the types in the hoard sample, both bearing the legend VESTA: Vesta veiled, holding the palladium and a sceptre (RIC 360 — 489 examples), and Vesta holding a patera and transverse sceptre (RIC 362 — 171 examples).

Venus Caelestis disappears from the imperial coinage, and instead Mamaea is associated with Venus Felix, Genetrix and Victrix, types seen on the coinage of Julia Domna (RIC 350–8, 694–707). All three incarnations of Venus feature on the examples found in the hoards.Footnote 89 Two Fecunditas types are also present in significant numbers: one with Fecunditas standing, holding a hand over a child with a patera and cornucopiae, and the other showing Fecunditas seated, holding the arm of a child.Footnote 90 Both types have the legend FECVND AVGVSTAE, and the imagery highlights Mamaea's role as the mother of the emperor. Felicitas also features. One type shows a standing Felicitas holding a caduceus and leaning on a column, the other a seated Felicitas holding a caduceus and cornucopiae. Both types have the reverse legend FELICITAS PVBLICA, and both feature significantly in the hoard sample.Footnote 91 Thus the numismatic image of Julia Mamaea highlights the return to a felicitous and conservative government after the rule of Elagabalus.

THE NUMISMATIC IMAGE OF ORBIANA (ad 225–7)

Orbiana married Alexander in ad 225, but when her father tried to rouse the Praetorian Guard to riot, Orbiana's father was executed and she was sent to Libya in exile.Footnote 92 Orbiana's silver coinage was found in very small amounts in the hoard sample, and the examples uncovered have an overwhelming emphasis on Concordia (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. Reverse silver types of Orbiana (no. = 125).

Nearly all the coins of Orbiana found in the hoard sample are of a single type, showing a seated Concordia with a patera and double cornucopiae, with the legend CONCORDIA AVGG (RIC 319 — 124 examples) (Fig. 19). The emphasis on Concordia recalls the numismatic images of the other imperial wives whose marriages remained brief.

Fig. 19. Denarius of Orbiana showing Concordia (RIC 319). (Reproduced courtesy of the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.; http://www.cngcoins.com .)

Only one other coin type was uncovered in the hoard sample, a single specimen of RIC 325, which has a reverse type showing Felicitas holding a caduceus and a patera over a lighted altar with the legend SAECVLI FELICITAS.

CONCLUSIONS

The numismatic images of the Severan women have points of continuity and difference. It appears that a set proportion of silver coinage was struck for the empresses in this period, likely the work of a dedicated officina. The similarity in the proportion of silver coinage struck for the imperial women across the entire Severan dynasty is suggestive also of the central role the ideology of the domus divina played in this period. Comparison with the Flavian and Antonine periods highlights the fact that mint production templates could change. The fact that this did not occur in the Severan dynasty underscores the central role played by lineage in the transfer of power. The Severan women occupied a significant ideological place in this discourse, forming the blood connection between one emperor and the next. This role is underscored by the continuity in the imagery associated with the empresses throughout the dynasty, with types of Venus Felix, Venus Genetrix, Venus Victrix, Vesta, Juno, Felicitas and Fecunditas appearing and reappearing, underscoring the connection to the past. Despite these points of similarity, however, the overall numismatic image of each empress is different, just as each emperor's image was different.

The imagery on the empress's coinage was utilized to extend the prevailing ideology of the emperor in power. Domna was granted a diverse numismatic image under Severus, reflecting his own array of ideological claims. Domna's types were simplified under the sole rule of Caracalla, a reflection of the fact that he emphasized one factor (divine support) as a supporting pillar of the regime. Julia Mamaea's coin types extend the dialogue of Roman restoration under the rule of Severus Alexander. The numismatic iconography of the imperial wives after Domna has a significant emphasis on Concordia, but this is no doubt due to the very short marriages of the later Severan emperors, meaning little more than the marriage itself could be communicated on coinage.

It is in the conflicting numismatic images of Julia Soaemias and Julia Maesa that we see the most radical points of difference. While Maesa's coinage as represented in the hoard sample proclaims values appropriate for a Roman matron, the coinage of her daughter Julia Soaemias has an almost exclusive focus on Venus Caelestis, a type never seen before or after on imperial coinage. The reasons behind these conflicting images may never be understood fully, but this, more than any other point in the Severan period, suggests the potential for some individuality in the numismatic representation of imperial women. Whether through official intention, or through a more organic knowledge of the activities and characters of these women, or for some other reason, Mamaea and her daughter present radically different public images, and one must imagine that this was a contributing factor in Soaemias's death and Maesa's survival.

By examining the coinage of the imperial women from a quantitative perspective we can understand better what each empress's coinage was communicating, and we can identify points of continuity and difference throughout the dynasty. Coinage, inscriptions and other official outputs of the regime remain our best way of reconstructing the public image of the women of the imperial house. Gauging the relative quantities of different coin types struck for the imperial women means we are able to move beyond a simple listing of all types to a better understanding of the context of each image; whether it was struck for a specific purpose, or for more general circulation. The reception of these images and ideas is more difficult to uncover. Though there is a variety of evidence speaking to the reception of the emperor's public image by local cities in the Severan period, the Severan empresses are often aligned with the Tyche of a city or other local cult.Footnote 93 It appears, then, that in these local negotiations of imperial power, the Severan women were integrated firmly into local culture. Consequently, their representation on provincial coinage (and provincial monuments more generally) is different from region to region, and different from the numismatic image released by the mint at Rome. A fuller study of these representations, aided by the work being performed on the Roman Provincial Coinage catalogues, will result in a better understanding of how the ‘official’ numismatic imagery of Rome intersected with civic ideologies. At the moment one can merely observe that the presence of many of the Severan imperial women in provincial and private contexts underscores a wider understanding of their central role in the continuation of the Severan dynasty.