Traditional gender norms and sexuality are closely intertwined with radical right politics in Europe (Akkerman Reference Akkerman2015; Grzebalska and Pető Reference Grzebalska and Pető2017a). Through their repeated emphasis on concepts such as the nefarious impact of “gender ideology” on society and their explicit support for traditional gender roles, radical right parties have made a name for themselves as defenders of a way of life that exalts the traditional family and embraces (at least some semblance of) a patriarchal social system. Despite the radical right's broader emphasis on the traditional family and gender norms, however, an equally strong narrative surrounding the preservation of “[European/Western] gender equality” has arisen in a variety of (primarily Western European) radical right parties, which use such language as part of a larger anti-immigrant or anti-Muslim discourse. While this “femonationalist” (Farris Reference Farris2017) rhetoric has become commonplace among some of these parties, its reception and potential impact on the general electorate so far appears to be largely nonexistent (Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015a).

These developments present a challenging paradox for scholars of the radical right, who have yet to fully make sense of this phenomenon. Strong arguments are emerging that traditionalism is no longer even a primary motivator for the radical right and that immigration and nationalism are now the “core” sources of concern for its supporters (Lancaster Reference Lancaster2020). This is in line with one of the most consistent findings in the literature on the radical right over the last half century: that there is a robust connection between harboring xenophobic, anti-immigrant attitudes and supporting the party family (Iversflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015b).Footnote 1

I argue that it is too soon to abandon the idea that traditional attitudes, particularly gender attitudes, matter deeply for radical right support. While it is true that we have well-established evidence that nativism is a significant driver of the demand for radical right politics, we still have a limited understanding of how attitudes beyond authoritarianism and populism (the other two “pillars” of the radical right ideology), such as gender attitudes, may factor in.Footnote 2 A growing body of work has noted that gender and nativism are related to the radical right project, especially in certain contexts (Farris Reference Farris2017; Mudde and Kastwaller Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2015; Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015a), but the nuances of this relationship are still largely unknown.

In this article, I analyze the relationship between gender role attitudes, nativism, and radical right support in 23 European countries using data from the 2017 European Values Study. I seek to answer two sets of questions about the radical right and its connection to traditional gender norms. First, are the traditional gender attitudes that radical right discourse seemingly seeks to tap into uniquely associated with radical right-wing support, or are they associated with support for mainstream conservative parties more broadly? Although the radical right appears to dominate the socially conservative issue space in many European countries, gender traditionalists might instead find a home with more mainstream conservative parties. Second, is the relationship between traditional gender attitudes and support for the radical right moderated by the influence of other factors, namely, nationalism and xenophobia (i.e., nativism), that have previously been identified as major conduits of support for the radical right? As I will argue, nativism and traditional gender norms share an analogous structure, which implies that they might complement each other in drawing individuals into the radical right fold.

I find that holding highly gender-traditional attitudes increases the likelihood of supporting the radical right but not mainstream conservative parties. Furthermore, an analysis of the interactive effect of gender attitudes and nativist attitudes on support for the radical right reveals that holding more gender-traditional attitudes increases the likelihood that both nativists and non-nativists will support the party family. Considering how integral nativism is to the radical right project, this finding is particularly poignant, suggesting that traditional gender attitudes are an additional pathway of support for individuals who otherwise would not be inclined to identify with the ideology.

These findings speak to the radical right's unique ability to capitalize on matters related to gender norms, the nation, and the intersection of the two. In addition to its strong nativist ideology, the radical right has, with few exceptions, a long history of associating itself with traditional positions on matters related to gender, the family, and sexuality, and it has repeatedly emphasized childbirth and child-rearing as matters related to the national interest (Akkerman Reference Akkerman2015).Footnote 3 Even in countries where the radical right has embraced what it characterizes as “Western” or “European” gender equality, much of its nativist rhetoric is framed in a way that speaks to implicit conceptualizations of gender. This allows both openly gender-traditional radical right parties and their slightly more progressive (at least in terms of their rhetoric) counterparts similar opportunities to appeal to people on a gendered dimension.Footnote 4

Ultimately, my findings suggest that both gender attitudes and nativism, including their intersection, play an important role in the radical right electorate. These findings also provide an additional explanation for the motivations that might prompt an individual to support the radical right more broadly, an area of study that so far has been lacking in the research addressing the “demand” side of the radical right's emergence and persistence (Fitzgerald Reference Fitzgerald2018).

THEORIZING GENDER ATTITUDES AND NATIVISM

Gender is a multifaceted paradigm that exists as part of an unspoken, taken-for-granted social ordering that both organizes power over individuals and dictates how they perceive the world around them (Brush Reference Brush2003). The state actively creates, reinforces, and reproduces the aforementioned social structures, which include the sexual division of labor, heteronormativity, and other gendered power hierarchies, through its various laws and policy priorities (Htun Reference Htun2005; Young Reference Young2002). Because this “gendering” is inherent to so many of our interactions and spaces, it becomes “invisible” and “second nature” in a way that makes its outcomes and consequences feel inherent and intuitive. It is one of the first systems of power that becomes fully fleshed out in our psyche, and its psychological potency over how we organize and interpret the social world is evident even in very young children (Charafeddine et al. Reference Charafeddine, Zambrana, Triniol, Mercier, Clément, Kaufmann, Reboul, Pons and Van der Henst2020; Leinbach, Hort, and Fagot Reference Leinbach, Hort and Fagot1997). These dynamics also structure adult behavior, with men and women segregating themselves into social and professional roles that reflect sex role stereotypes, for instance (Cejka and Eagly Reference Cejka and Eagly1999).

A vast literature has identified how identity-related attitudes, such as racial attitudes in the United States, shape the ways in which people interact with and process the world around them (e.g., Gilens Reference Gilens2009; Tesler Reference Tesler2012; Winter Reference Winter2008). For example, over the course of Barack Obama's presidency in the United States, several studies demonstrated that racial predispositions had a growing impact on individual perceptions of politics (Tesler Reference Tesler2016; Tesler and Sears Reference Tesler and Sears2010). Given how intrinsic gender is to the way we process the world, we should expect that an individual's beliefs or feelings (either conscious or subconscious) that are gendered also have important implications for how he or she arrives at certain political opinions. This point has been emphasized recently by Monica Schneider and Angela Bos (Reference Schneider and Bos2019, 202), who argue that we should expect gender roles and expectations to “shape public opinion, political participation, and elite and voter prejudice.” These are the gender “attitudes” referred to in this article.

Historically, however, most of the research focused on the intersection of gender and public opinion has been concentrated on either the “gender gap” in voting or opinion differences or how one's understanding of one's own gender (i.e., gender consciousness) impacts political behavior—with several important exceptions.Footnote 5 Nicholas Winter (Reference Winter2000, Reference Winter2008) found that gender attitudes significantly influenced opinions about Hillary Clinton during her time as first lady of the United States in the 1990s, while Mary McThomas and Michael Tesler (Reference McThomas and Tesler2016) extended this research and found that Clinton's exceptional popularity during her tenure as secretary of state was driven almost entirely by gender egalitarians. More recently, the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States, and the growing influence of the far right globally, prompted a variety of scholarship on the role of sexist attitudes on vote choice, largely confined to the 2016 U.S. presidential election (Bracic, Israel-Trummel, and Shortle Reference Bracic, Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019; Cassese and Barnes Reference Cassese and Barnes2019; Glick Reference Glick2019; Ratliff et al. Reference Ratliff, Redford, Conway and Smith2019; Schaffner, Macwilliams, and Nteta Reference Schaffner, Macwilliams and Nteta2018; Valentino, Wayne, and Oceno Reference Valentino, Wayne and Oceno2018; Winter Reference Winter2018), with comparatively little focus on party systems across Europe (Lodders and Weldon Reference Lodders and Weldon2019).Footnote 6

In the European context, most recent scholarship related to gender attitudes has focused on the development of pro-gender equality attitudes (rather than the consequences of persistent traditional gender attitudes) and how these attitudes are related to questions not directly linked to party evaluations, a practice that Niels Spierings (Reference Spierings and Verloo2018) labels “progress bias.” Even studies that are framed as more questioning or skeptical “take positive development [toward gender equality] as their starting point” (Spierings Reference Spierings and Verloo2018, 173). Important exceptions to these trends include works by Niels Spierings and Andrej Zaslove (Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015b), who use data from the 2010 European Social Survey to assess whether attitudes regarding gender equality and equal rights for gays and lesbians helps explain the sex gap in voting for radical right parties, and by Jane Green and Rosalind Shorrocks (Reference Green and Shorrocks2021), who find that “gender resentment” and other gender-related concerns appear to have played a role in prompting some individuals in the United Kingdom (particularly men) to vote to leave the European Union in 2017.Footnote 7

Therefore, we still have much to learn about how gender attitudes impact political behavior, including how they interact with other factors known to influence opinion, such as nativism. Preliminary scholarship to this end is beginning to emerge in the American politics literature. Laura Van Berkel, Ludwin E. Molina, and Sahana Mukherjee (Reference Van Berkel, Molina and Mukherjee2017) analyze whether the American identity itself is gendered and find that both men and women were likely to construct the “prototypical” American as more masculine than feminine. Meanwhile, Melissa Deckman and Erin Cassese (Reference Deckman and Cassese2021) find that “gendered nationalism” strongly predicted support for Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. presidential election among both men and women.Footnote 8 This literature is nascent, however, and much work remains to be done—particularly in the non-American context.

I theorize that traditional gender attitudes are an important conduit for radical right support. The considerable influence of these attitudes stems from their ability to, on their own, increase the likelihood that an individual supports the radical right, as well as their ability to magnify the influence of other conduits for radical right support, including nativism. Regarding the latter, I theorize that gender attitudes can moderate the relationship between radical right support and nativism because of both the implicitly gendered structure of nativism and the explicitly gendered goals of the nativist project. As a result, traditional gender attitudes have the capacity to influence public opinion on their own, as well as work in conjunction with nativism to produce support for political leaders and parties that adopt a nativist policy agenda and rhetoric—such as the radical right. For clarity, I am not arguing that gender traditionalism raises the probability of being nativist and therefore support for the radical right. Rather, I argue that while each likely exerts an independent influence on the propensity to support the radical right, nativism and gender traditionalism are attitudinally compatible in such a way that when both are present, the likelihood of supporting the radical right is higher than when one is not present.

Nativism's implicit congruence with gender traditionalism is most closely connected to the ways in which patriarchal power relations are analogous at both the macro (state) and micro (individual) levels. For example, Iris Marion Young (Reference Young2003) traces the existence of the security state to the pervasiveness of patriarchy, arguing that individuals raised in societies where women are used to trading freedom for security from a benevolent patriarch are much more receptive to similar trade-offs made with the state, a phenomenon she dubs the “logic of masculine protection.” Just as a husband and father can expect obedience, respect, and loyalty in exchange for providing protection (be it physically or financially), the state can demand the same fealty from its citizens in exchange for protection from all enemies “foreign and domestic.”

The logic of masculine protection creates a parallel relationship between the man protecting the woman and children at home and the state protecting the nation and its citizens. The normalization of this dynamic has important implications for democracy and citizens’ willingness to acquiesce to the erosion of their freedoms and privacy under the guise of “protection.”Footnote 9 The security state becomes normalized because individuals are already conditioned to the protector (masculine)/protected (feminine) dynamic in their homes and throughout society and popular culture.

If the security state naturally becomes gendered masculine as it takes on the role of protector, then the nation, which must be protected, becomes gendered feminine. This symbolism lies at the heart of the congruence and potential synergy of nativism and gender traditionalism. Nira Yuval-Davis (Reference Yuval-Davis1993, Reference Yuval-Davis1997) emphasizes that we cannot understand the nation without considering that women reproduce it biologically, culturally, and symbolically. This reality, combined with the reinforcement of the traditional family (wherein women are confined to the private home while men occupy the public world) creates a scenario in which female bodies become wrapped up in conceptualizations of the nation. As the embodiment of a common historical identity or destiny that must be continually renewed and carefully preserved, the nation displays a sense of vulnerability and defenselessness—two traits that are gendered feminine. The nation becomes a feminine space that calls for protection from masculine actors (i.e., the state) because “protection” and “defending” are gendered masculine.Footnote 10

Of course, not all the connections between gender and the nation are symbolic. The survival of individual, unique nations cannot be achieved unless native women commit to having children, and therefore this particular gendering must become much more explicit. Literal women are essential to the nationalist project, because they not only physically reproduce the nation through childbearing but conceptually reproduce it by raising ethnically pure children with a nationalist mindset (Yuval-Davis and Anthias Reference Yuval-Davis and Anthias1989). When Hungary promises to give a minivan to every native woman with more than three children (Kingsley Reference Kingsley2019; Reuters for Budapest 2018), or when the Alternative for Germany party puts up a poster featuring a photo of a white pregnant belly and the slogan “New Germans? We'll Make Them Ourselves” (Nelson Reference Nelson2017), the message is subtle but still clear: have children so that we can rely on your offspring, and not migrants, to keep this country alive.

The radical right is enmeshed within the gendered logic of masculine protection and feminine vulnerability just outlined. As a nativist party family, its rhetoric and imagery are replete with calls to protect both the physical borders of the nation and its values. And because a portion of these nationalistic claims rest on an unspoken, traditionally gendered logic, they are able to speak to voters who are already predisposed to thinking about the world through an analogously gendered lens (Winter Reference Winter2008). For individuals with a more “traditional” gender lens, their gendered beliefs may serve as a beacon for what is true and real in a world that seems increasingly unfamiliar. When America was “great,” for instance, the world was organized around what are now considered traditional gender roles (man at work, woman at home).

For these individuals, a return to traditional roles and values is a critical step in life returning to “normal,” because life as they once knew it feels like it is slipping away. By espousing policies that seek to “turn back the clock and reestablish eras of homogeneous demography, rigid hierarchy, and protectionist economics” (Gest, Reny, and Mayer Reference Gest, Reny and Mayer2018, 1695), radical right parties portray themselves as some of the last and only institutions and people capable of bringing back this lost sense of “normalcy,” which is closely tied to traditional gender norms—even if they are never mentioned outright. This phenomenon fits under the umbrella of the larger “cultural backlash” to the displacement of traditional gender roles, familial structures, and sexualities, in addition to countless other socially liberal and postmaterialist values that have swept the Western world over the last several decades (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019).

Given the ways in which traditional gender norms are closely intertwined with the nativist elements of the radical right, I have several expectations. First, traditional gender attitudes will be associated with support for the radical right more generally. Stated formally,

H1a: Compared with those who hold more gender-egalitarian attitudes, highly gender-traditional individuals will be more likely to select a radical right party as most appealing.

One way to further test this hypothesis is to compare support for the radical right among gender traditionalists with their support for mainstream conservative parties, which have not been as closely associated with gendered and nativist rhetoric over the last several decades. In other words,

H1b: Compared with those who hold more gender-egalitarian attitudes, individuals with higher gender-traditional attitudes will have a greater likelihood of finding radical right parties more appealing than mainstream conservative parties.

Finally, if nativism and gender traditionalism are psychologically congruent in the way argued earlier, I anticipate that this will be reflected in support for the radical right among people who profess high levels of both attitudes:

H2: Compared with those who hold more gender-egalitarian and non-nativist attitudes, individuals who hold both stronger gender-traditional attitudes and nativist attitudes will have a greater likelihood of finding radical right parties more appealing.

DATA AND METHODS

To analyze the connections between gender traditionalism and the appeal of the radical right, I utilize data from the 2017 European Values Study (EVS 2019). The EVS is conducted every nine years, and it is intended to gauge how Europeans “think about life, family, work, religion, politics, and society.” As of this writing, it included the most comprehensive and current data on the items and countries of interest to this analysis. The 2017 study features a probabilistic representative sample and a minimum of either 1,000 or 1,200 respondents per country, depending on whether the population was less than or more than two million. All told, the analyses presented in this article draw on upwards of 20,000 observations across 23 countries from within the EVS.Footnote 11

Dependent Variables

To assess support for the radical right, I created a binary variable coded 1 when an individual selected a radical right party as “most appealing” and 0 for all other parties.Footnote 12 Responses labeled “don't know,” “no answer,” “not applicable,” “not included,” or “missing” were dropped from the data set.Footnote 13 To assess the equivalent support for mainstream conservative parties, I created a second binary variable coded in the same fashion.

There are drawbacks to relying on self-reported data about either people's preferences for parties or their vote choice. It is possible that an individual might be willing to express a preference for a radical right party and not actually follow through with that preference at the ballot box. However, it is also possible that an individual might be hesitant to express open preference for a radical right party on a survey because of social desirability bias. A meaningful difference likely exists between someone's preference versus actual behavior, as the former may capture the radical right's potential electorate, while the latter captures (or at least attempts to) the present electorate. I approach my analysis of expressed appeal for the radical right (versus confirmed vote choice) with these realities in mind.

Independent Variable

To gauge an individual's gender attitudes, I constructed a scale from eight survey questions asking about opinions regarding the roles men and women should play in society. Exploratory factor analysis confirmed that each of these survey items load on the same factor.Footnote 14 The survey items included are as follows:

• When a mother works for pay, the children suffer.

• A job is alright, but what most women really want is a home and children.

• All in all, family life suffers when the woman has a full-time job.

• A man's job is to earn money; a woman's job is to look after the home and family.

• On the whole, men make better political leaders than women do.

• A university education is more important for a boy than for a girl.

• On the whole, men make better business executives than women do.

• When jobs are scarce, men have more right to a job than women.

Each question was measured using a 4-point scale (except for the job scarcity question, which used 5). The combined gender attitudes scale created for this analysis was normalized to run from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher levels support for gender traditionalism.

Moderating Variable: Nativism

To capture nativist attitudes, I selected questions that fall along both the nationalist and xenophobic elements of the ideology. This is in keeping with the accepted definition of nativism in the broader literature on the radical right, which sees the ideology as a combination of nationalism and xenophobia that argues countries should be made up solely of members of the “nation” (natives) to the exclusion of non-native outsiders, who are perceived as a threat to the largely homogeneous shared values and customs encapsulated by the nation-state (Mudde Reference Mudde2017). To approximate the nationalist component of nativism, I include a question asking respondents about the importance of being born their native country. The question was prefaced with the following statement: “Some people say the following things are important for being truly [nationality]. Others say they are not important. How important do you think each of the following is?” The respondents were then asked whether being born in their country was important. For xenophobia, I created an index from four variables that deal with a respondent's attitudes toward immigrants:

• What impact do you think immigrants have on the development of [your country]?

• Do immigrants take away jobs from [nationality]?

• Do immigrants increase crime problems?

• Are immigrants a strain on the welfare system?

Each of these survey items load on the same factor.Footnote 15

It is important to note here that although nativism is a singular construct, these questions are entered into the model separately because of methodological constraints. No single question on the EVS fully captures nativism, nor do any of the separate survey items in the data set dealing with nationalism and xenophobia load onto the same factor, which significantly lowers the reliability of any scale that attempts to combine them.

Controls

A number of other ideological positions have been identified as predictors of support for either nativism or the radical right, including authoritarianism and beliefs about income redistribution. To capture authoritarianism, I include one item measured using a 10-point scale asking whether respondents think it is an “essential characteristic of democracy that people obey their rulers” (with higher scores indicating it is an essential characteristic) and one categorical variable asking whether respondents think it would be “good,” “bad,” or “don't mind” if there were a societal shift toward greater respect for authority. To account for attitudes about income redistribution, I include a 10-point scale asking whether the respondent considered “governments tax the rich and subsidize the poor” an essential characteristic of democracy, with higher levels corresponding with the belief that such measures are essential.Footnote 16

I also include controls for respondents’ left-right ideology, religious identity, and level of confidence in their national parliament. Ideology was measured using a 10-point scale by asking the following question: “In political matters, people talk of ‘the left’ and ‘the right.’ How would you place your views on this scale, generally speaking?” Higher items indicate the right. Religious identity is a categorical variable asking whether a person identifies as “religious,” “not religious,” or a “convinced atheist” independent of church attendance. Confidence in parliament was measured with a categorial variable asking respondents whether they considered themselves to have a “great deal,” “quite a lot,” “not very much,” or “none at all” in terms of confidence.

Controls were also added for demographics, socioeconomic factors and other attitudes identified as predictors of support for the radical right in the literature, including age, sex, education, employment status, and political memberships. Finally, to account for unobserved heterogeneity between the different countries represented in these data, I employ country-level fixed effects in the form of dummy variables for each country represented in the analysis.

RESULTS

Descriptive Analyses

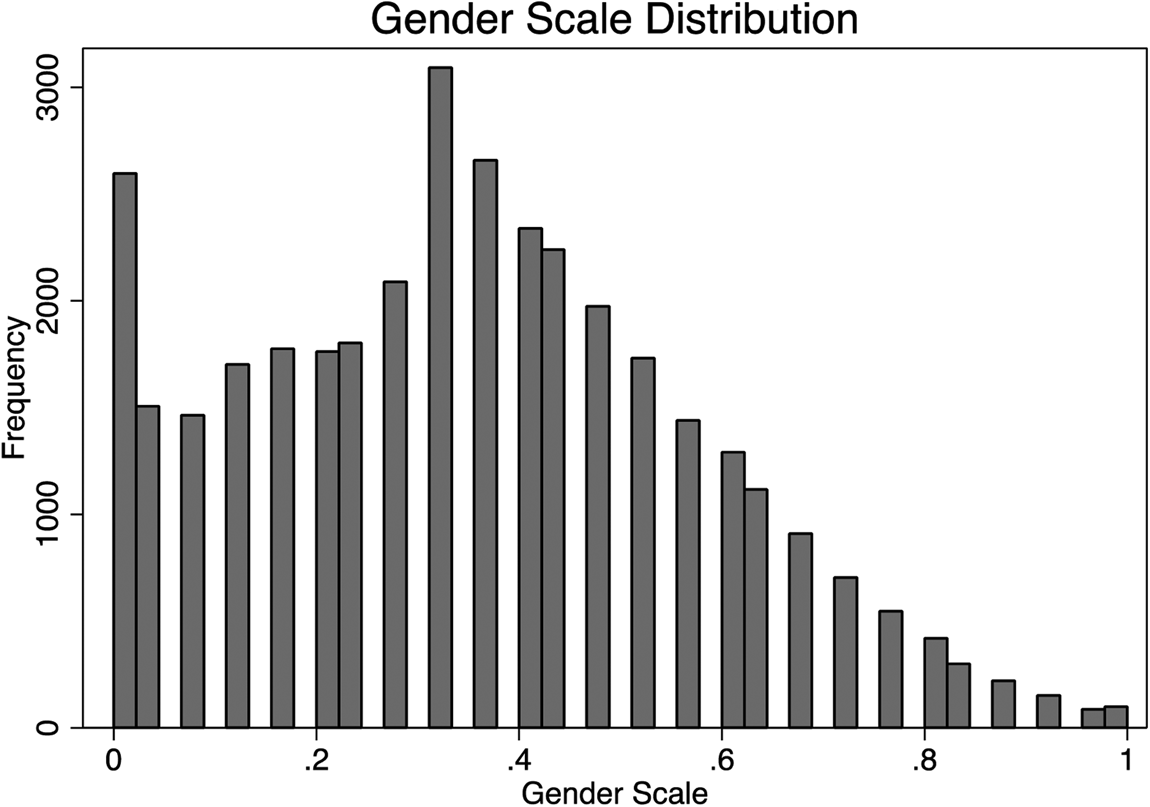

Figure 1 displays the full distribution of gender attitudes in the EVS sample. Among all respondents, the mean score on the gender attitudes scale was .35 and the median was .36. Broken down by sex, the mean gender attitudes score for all women in the sample was .34 versus .38 for men.

Figure 1. Gender scale distribution.

This distribution tells us that a majority of respondents in the EVS sample trend toward gender egalitarianism in their beliefs, with relatively few individuals selecting answers that would place them at the highest levels of gender traditionalism. Among the countries included in the full analyses in this article, Slovakia had the highest mean score on the gender scale (.48) and Norway had the lowest (.13). Northern European countries had a mean score of .19, Western European countries had a mean score of .29, and Eastern European countries had a mean score of .45.

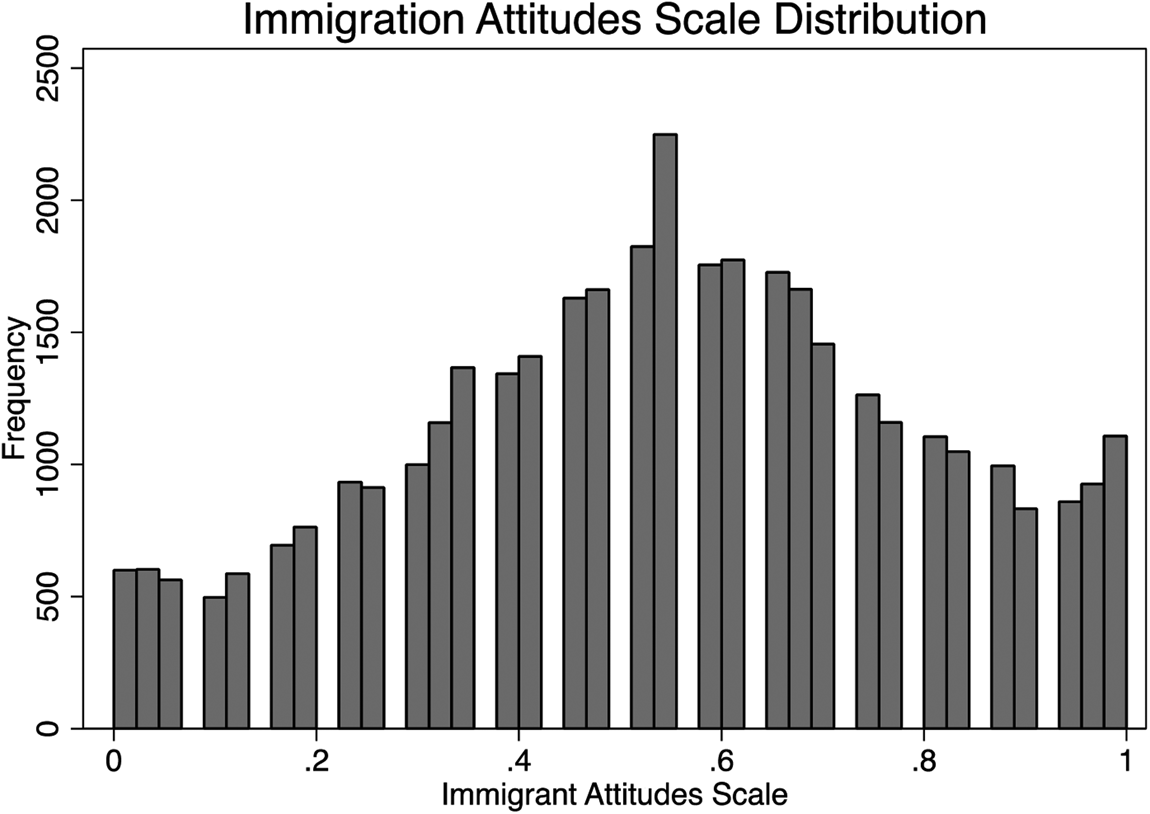

Regarding nationalism, a clear majority of respondents (61%) said that they felt it was important to be born in their country in order to be a part of their country's nationality. For the more xenophobic attitudes, the mean value on the constructed immigration attitudes scale among all respondents was .54 (see Figure 2 for the full distribution) and the median was .55, which indicates that the average respondent in the sample was mostly neutral on the potential contributions or downsides of immigrants in their country.

Figure 2. Immigration attitudes scale distribution.

Among the individual countries included in the full analysis, Hungary had the highest mean score on the immigration scale (.72) and Albania had the lowest (.32). When categorized by region, the mean immigration score was much closer across the three groups than the mean gender attitudes score. Northern European countries had a mean score of .49, Western European countries overall had a mean score of .54, and Eastern European countries had a mean score of.58.

In terms of overall support for the radical right, 7.6% of respondents selected a radical right party and 14% selected a mainstream conservative party as “most appealing.” Broken down by sex, 46.7% of respondents who selected the radical right were women and 53.3% were men, a 6.6 percentage point difference (p < .000).Footnote 17 Among those who selected a mainstream conservative party 51.9% were women and 48.1% were men (3.8 percentage point difference, p < .000).

From here, I divide the explanatory results into two sections: gender attitudes and support for the radical right, and the potential interactions between both gender attitudes and nativist attitudes on radical right support.

Explanatory Analyses

Gender Attitudes and the Radical Right

To assess the relationship between gender attitudes and support for the radical right, I estimated two different logistic regression models. The first model looks solely at the bivariate relationship between support for the radical right and gender attitudes. The results are presented in the first column of Table B1 in Appendix B.Footnote 18 This initial model is consistent with H1a: higher levels of gender traditionalism positively predict support for the radical right (B = .73, SE = .078, p < .000). This finding holds in the fully specified model that includes the nativist and other control variables outlined above (column 5 in Table B1, Appendix B).

To illustrate whether gender-traditional attitudes have a unique impact on support for the radical right, I reestimated the foregoing models after replacing radical right support with mainstream conservative support in the dependent variable. The results for the bivariate model (column 2 in Table B1) show a negative, statistically significant correlation (B = –.67, SE = .062, p < .000), but this result disappears in the fully specified model (column 6 in Table B1).

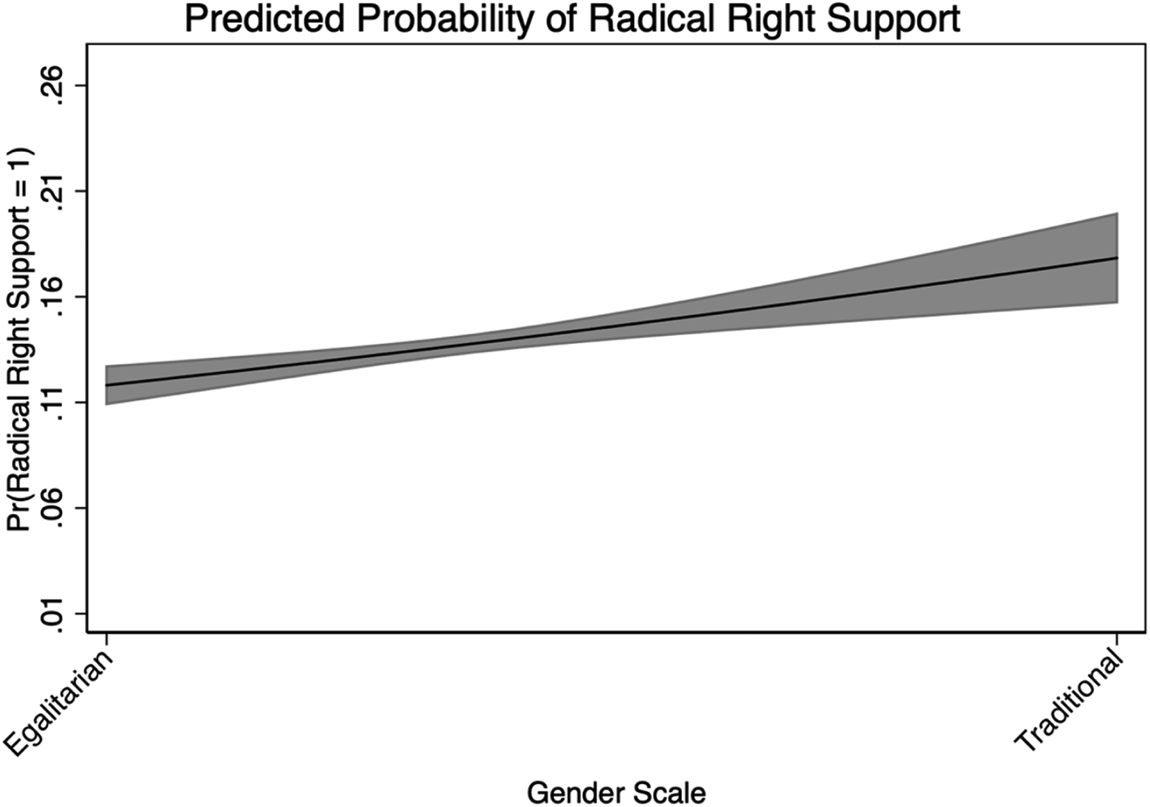

Because logistic regression coefficients must be interpreted through either logged odds or odds ratios (which are not as intuitive as the interpretations for coefficients reported using ordinary least squares regression), I turn here to predicted margins/probabilities for a more straightforward, fine-grained interpretation of the results discussed earlier. Figure 3 displays the predicted probability and 95% confidence interval that an individual selected a radical right party as “most appealing” across all potential values of the gender traditionalism scale, holding the other variables in the model at their observed values.Footnote 19, Footnote 20

Figure 3. Predicted probability of radical right support.

Those at the highest level of gender traditionalism have a .178 predicted probability of supporting the radical right, while those at the lowest level have a .118 predicted probability—a 6 percentage point difference. The results are statistically significant at the p < .000 level.Footnote 21, Footnote 22 This suggests that, all else being equal, being more gender traditional raises the probability that an individual will support the radical right.

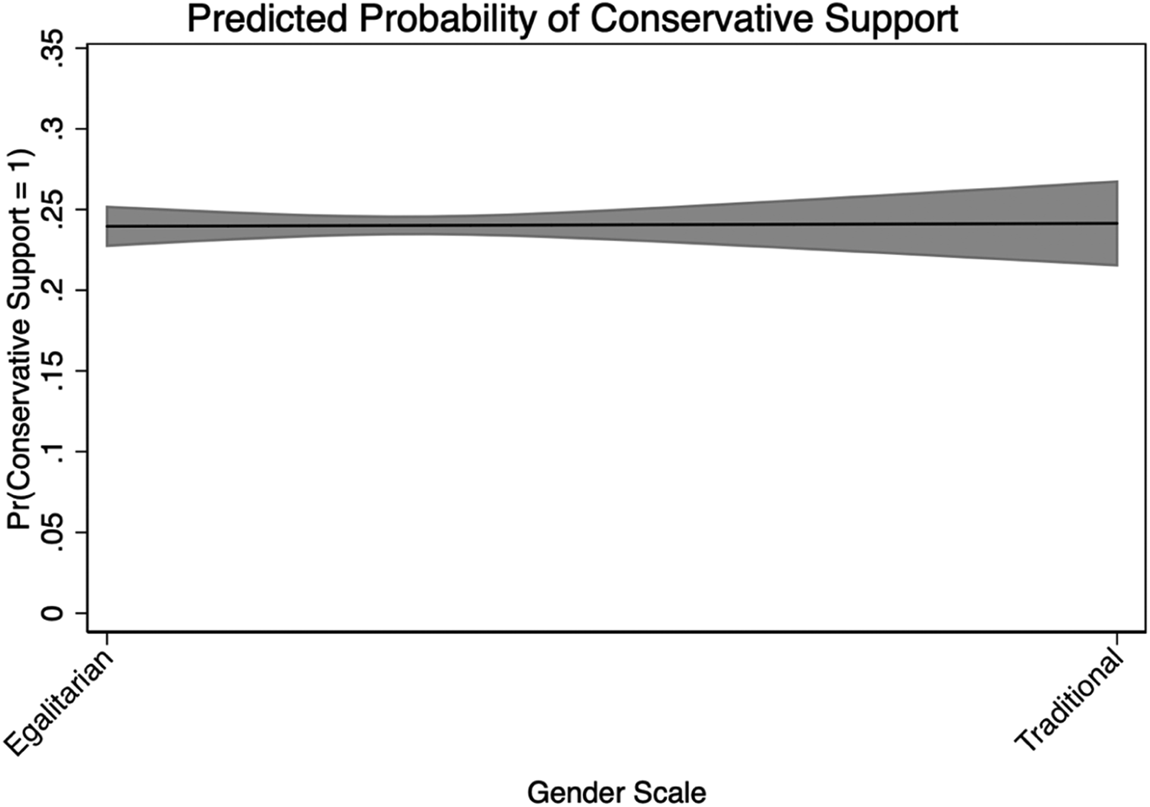

To ascertain whether gender traditionalism has a unique impact on support for radical right parties, I conducted the same analysis on an individual's likelihood of selecting a conservative party as “most appealing” given their position on the gender traditionalism scale. The predicted probabilities are presented graphically in Figure 4. Note that in the full models, gender traditionalism is positively correlated with support for mainstream conservative parties, but this result is not statistically significant.

Figure 4. Predicted probability of conservative support.

As the graph demonstrates, those who are more gender traditional do not have a significantly higher likelihood of supporting mainstream conservative parties than gender egalitarians, with the predicted probability of support increasing by only 0.2 percentage points between the lowest and highest values of the gender attitudes scale (.239 versus .241). This suggests that while there is a greater probability that respondents will choose a conservative party over a radical right party more generally (and therefore slightly less ability for gender traditionalism to shift support either way), moving from low to high gender traditionalism appears to play almost no role in the probability of choosing to support mainstream conservative parties, providing support for the second component of my first hypothesis (H1b).Footnote 23

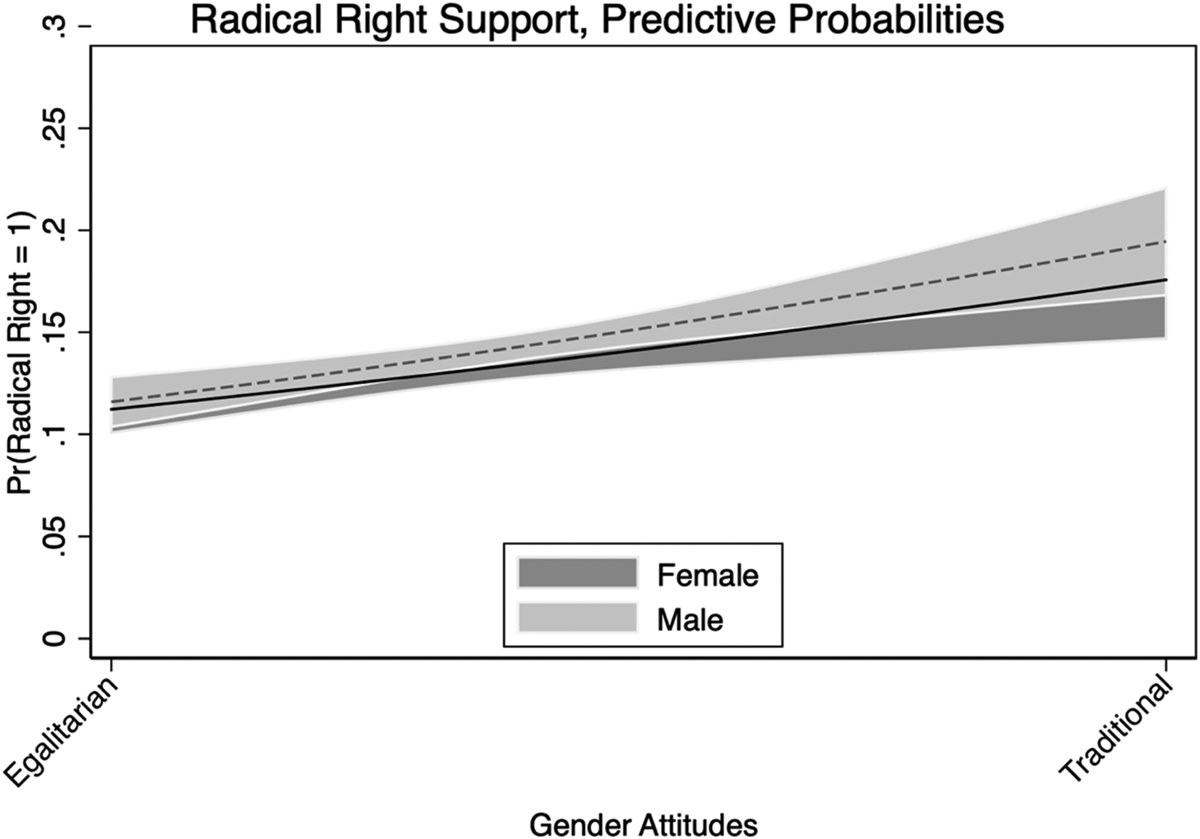

Gender Attitudes and Sex

It is also worth mentioning that in these data, respondent sex does not moderate the relationship between gender attitudes and radical right support. In the full model (Appendix B, Table B1), respondent sex is correlated with a higher likelihood of supporting the radical right. However, this finding disappears when respondent sex is interacted with the gender attitudes scale (Table B2). Although the average marginal effect of gender attitudes on support is 1.4 percentage points higher for men (7.3) than it is for women (5.9), there is no significant difference between the two (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Radical right support, predictive probabilities.

In other words, whether someone identifies as male or female does not appear to be the primarily “gendered” avenue to radical right support in these data. Instead, it appears to be certain beliefs and attitudes (either more egalitarian or more traditional) about the ways in which men and women are expected to operate within society that increase the likelihood of supporting the radical right party family.

Gender Attitudes, Nativism, and the Radical Right

So far, I have presented evidence that gender attitudes predict support for the radical right but not mainstream conservative parties. This finding suggests that gender traditionalism, like the well-established conduit that nativism provides, is a probable pathway toward supporting radical right-wing parties. But do these two pathways interact in any significant way? This section investigates whether simultaneously being both more gender traditional and nativist matters for radical right support. Studying the interactions of these two variables greatly enhances our understanding of the dynamics of these two constructs as they relate to supporting the radical right.

Using the same base model from the previous section, I interacted the gender attitudes scale with both the country of birth variable and the immigration attitudes scale. From there, I calculated the predicted probability that an individual selected a radical right party as “most appealing” across all potential values of the gender traditionalism scale and each of the nativist variables in question.Footnote 24

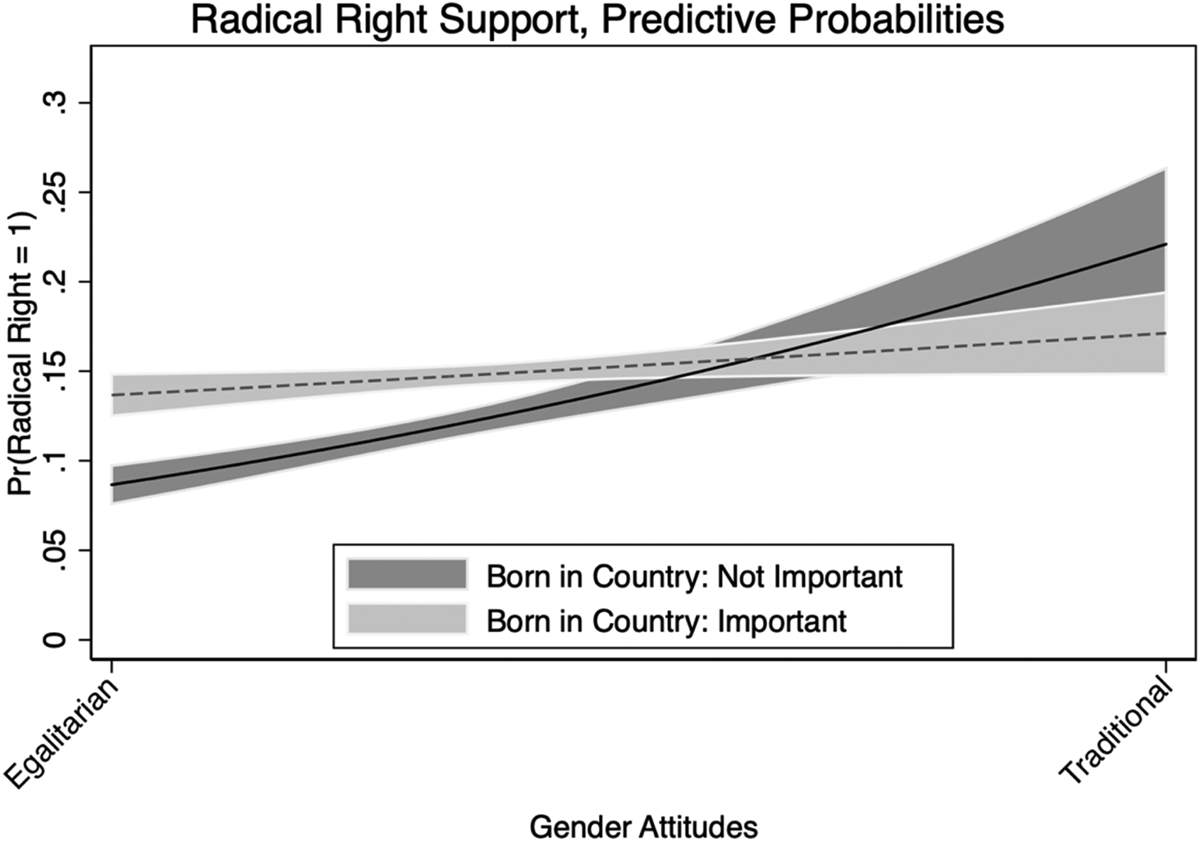

Country of Birth Attitudes and Gender Attitudes

Figure 6 graphically examines the relationship between a respondent's belief in the importance of being born in one's country to having one's nationality, holding gender-traditional attitudes, and radical right support. Fervent nativists tend to place a particularly high importance on the genetics of an individual for national “belonging.” While this question does not directly capture the question of genetics (certainly someone could be born in one's country yet still have a different national or ethnic ancestry), it is a close proxy. It strikes right at the heart of the implicit connections between nativism and traditional gender norms—that is, the idea that native women need to produce native children in order to preserve the nation's legacy and heritage.

Figure 6. Radical right support, predictive probabilities.

The results here indicate that being more gender traditional moderates the relationship between attitudes regarding the importance of one's birthplace and support for the radical right, but the “effect” size is much greater (13.5 versus 3.5 percentage points) for those who do not think being born in their country is important for nationality. The boost for nativists, while modest, is still significant at the p < .000 level. What is fascinating, however, is the steep increase in the probability of support between the non-nativist egalitarians and the non-nativist traditionalists. While it is possible that some of this effect may be coming from non-native, socially conservative migrants (who therefore would be less inclined to think being born in the country is important for nationality), one would expect those individuals to be even more likely to eschew the radical right due to the party family's exclusionary rhetoric towards non-natives. Therefore, while these results do provide evidence in support of H2, they also suggest that gender traditionalism does not work solely in favor of nativists.

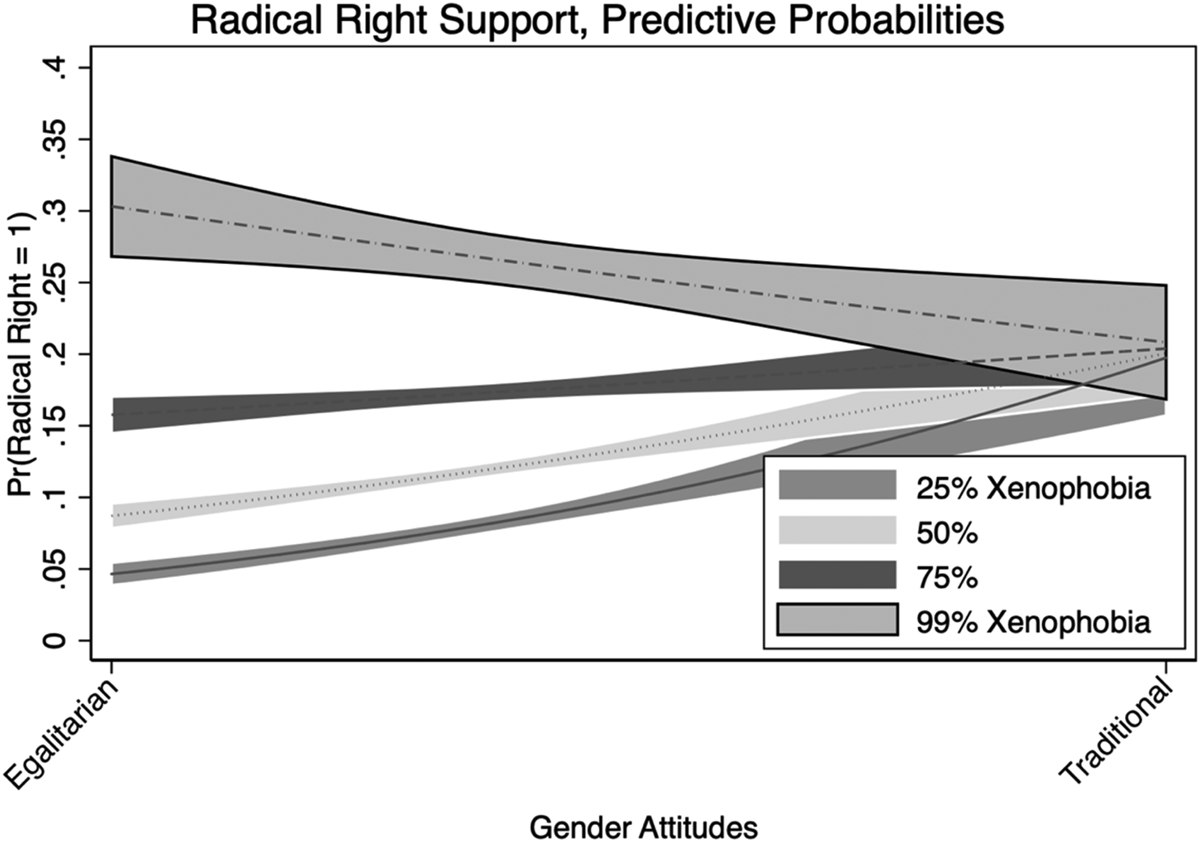

Immigration Attitudes and Gender Attitudes

I selected several points of interest along the composite immigration scale (the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 99th percentiles) before calculating the marginal effects. As a reminder, higher values on the scale indicate higher levels of anti-immigrant (and therefore xenophobic attitudes). Figure 7 displays the results.

Figure 7. Radical right support, predictive probabilities.

Here we see clear variation. Holding more gender-traditional attitudes is associated with a reduced probability of support for the radical right among the most fervent xenophobes (99th percentile, an overall 9.5 percentage point reduction), but a higher probability of support for everyone else.Footnote 25 This finding provides mixed support in favor of H2. Gender-traditional individuals at the 75th percentile of xenophobia do appear more likely to support the radical right than egalitarians, but this finding does not extend to the most (99th percentile) xenophobic individuals. While the most xenophobic gender traditionalists have the same probability of support for the radical right as those individuals in the other three quartiles, the largest probability of support comes from the most xenophobic egalitarians.Footnote 26

Why might this be the case? Prior work has identified a subset of “sexually modern nativists” (Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Reference Spierings, Lubbers and Zaslove2017) who are pro-gender and LGBTQ+ equality and have strong anti-migrant attitudes. It stands to reason that some sexually modern nativists might feel threatened by an influx of conservative immigrants and respond to such threats by choosing to vote for the radical right. These results suggest as much. However, the mechanisms behind why these individuals become activated along an anti-migrant dimension are still unclear, particularly because there is a current lack of evidence demonstrating a strong link between sexually modern nativists voting for the radical right in countries (such as the Netherlands) where the radical right is most vocal about its support for LGBTQ issues (Spierings Reference Spierings2021). Further work is needed to understand this phenomenon.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Radical right parties have long emphasized traditional family values in their manifestos, rhetoric, and policy agendas (Akkerman Reference Akkerman2015). In doing so, they speak to fears individuals may have about the decline in what they perceive as the “proper” roles for men and women in society, as well as more deeply rooted anxieties about what it means for the traditional gender order to be disrupted.

Overall, I find that traditional gender attitudes do predict support for the radical right, which stands in contrast with recent preliminary work on the topic (e.g., Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015b), a difference that could be the result of different samples (European Social Survey versus European Value Study, seven Western European countries versus a larger sample of countries across the continent, etc.) or time periods. What is clearer than ever is that there is still much we do not understand about the relationship between gender and radical right-wing parties; more research is urgently needed to further enhance our understanding of this relationship. A second major finding of this article is that while gender traditionalism is positively associated with radical right support, this is not the case with more mainstream or “traditional” conservative parties. This finding suggests that the appeal of radical right parties is uniquely gendered and that more research is needed to understand the ways that radical right parties and politicians incorporate traditional gender appeals in to their political communication.

Importantly, I also find that traditional gender attitudes and nativism combined have a nuanced yet meaningful impact on the likelihood of finding the radical right appealing. Anti-immigrant attitudes remain the highest predictors of support for the radical right in the full models—above and beyond gender attitudes and other common explanations—and a belief that it is important to be born in one's country in order to “truly” be a part of one's nationality is also a strong predictor. However, although nativists might appear to need very little extra “help” to support the radical right, my results suggest that being gender traditional still provides a boost that fits nicely within their broader paradigm.

Even more telling is that the “effect” of gender traditionalism on support also extends to non-nativists. This is a poignant finding, because most non-nativists should have strong priors against supporting the radical right, which, by and large, is defined as a party family by their subscription to nativist ideology. Theoretically, they should be able to find a “home” with another conservative party who, while perhaps not being as publicly forceful about their socially conservative agenda, still harbor similar views. We do not see that story play out in these data, however, since gender-traditional attitudes appear to play little role in inducing support for mainstream conservative parties. This finding forces us to reckon with whether nativism is always the common dominator of radical right support and suggests that holding gender-traditional attitudes is a potential backdoor pathway into the radical right fold for non-nativists. Although this is a purely speculative statement (this data set cannot fully validate this argument either way), such conjectures remain a potentially fruitful area for future research.

One limitation of this analysis is that I cannot ascertain a causal direction between either gender attitudes and nativism or gender attitudes, nativism, and radical right support. It is possible that the relationship between nativism and gender attitudes is truly multidirectional because of the analogous structure of both phenomena. Supporting more nativist viewpoints may subsequently increase the likelihood of expressing more gender-traditional attitudes or vice versa, and the subsequent outcomes would be relatively unchanged because they are so closely intertwined. On the other hand, experimental evidence is certainly needed to validate my claim that at least some of the connection between gender attitudes and nativism as it relates to the radical right is due to the congruence between implicitly gendered, nativist rhetoric and traditional gender attitudes. Future research should investigate these questions directly.

Another drawback of this study is that although it provides illuminating insights regarding the relationship between traditional gender attitudes and support for the radical right in Europe at a broad level, it is incapable of speaking directly to developments in strategic choices being made by radical right parties regarding gendered rhetoric. In particular, to help advance their nativist agenda while simultaneously expanding their base of support, some radical right-wing groups frame their Islamophobic stances as being primarily rooted in a defense of gender equality, a strategy seemingly at odds with gender traditionalism. Future research should investigate directly how such rhetoric is received by gender traditionalist individuals that this paper has identified as being more likely to support radical right-wing parties.

My results provide us with an additional motivation for why someone might be drawn to the radical right above and beyond our prevailing explanations. Although we know much about the demographic profile of the average radical right voter (male, working class, less educated, etc.), we still lack a complete explanation of the motivations that prompt individuals to support the radical right or not (Fitzgerald Reference Fitzgerald2018), and therefore why these individuals find the radical right so appealing. This paper adds individual gender attitudes to the list of potential motivations, for both nativists and non-nativists. Gender traditionalism can heighten the already vigorous connections between nativism and the radical right and draw in non-nativists who otherwise might be less inclined to support the party family.

Finally, this article imparts new context to our growing knowledge of how gender attitudes, similar to racial attitudes, impact political behavior (e.g., Deckman and Cassese Reference Deckman and Cassese2021; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019). There is a large scholarship on the impact of being either “male” or “female” on political behavior, but we know relatively little in comparison about the ways in which ideas regarding how either “men” or “women” should behave, or what is appropriately “masculine” or “feminine,” may exert an additional influence. Considering the fact that ideas about gender pervade almost every aspect of our lives, it is more important than ever to fully explore how they shape our politics.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X21000374