INTRODUCTION

The political science literature has emphasized that voting for religious parties, such as Christian-democratic parties, reflects cleavages that date back to conflicts from centuries ago (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Duncan Reference Duncan2015). The age-old conflict between church and state remains relevant for religious voters. Supporters of Christian-democratic parties are embedded in networks of religious organizations. Arzheimer and Carter (Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009) suggest that this has “immunized” them from new temptations such as the appeal of radical right-wing populist parties. The rise of radical right-wing populist parties is part of a development that can be seen all over Europe: that is the growing polarization along the “new cultural” dimension. Issues like immigration, the civic integration of immigrants, and national identity have become an important part of a competition between “cosmopolitan” and “parochial” parties (Pellikaan, Van der Meer, and De Lange Reference Pellikaan, Van der Meer and De Lange2003; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; De Vries Reference De Vries2018).

The central thesis of this article is that this image of “immunization” underestimates the importance of external developments for the constituencies of religious parties. Religious parties are not fully isolated from party competition, particularly in systems where there are multiple religious parties vying for the religious voter. Therefore, the politicization of the immigration dimension is likely to shape support for religious parties. The central question of this article therefore is to what extent has the politicization of immigration affected the electorates of religious parties.

Two mechanisms may link attitudes toward immigration and party choice. On the one hand, attitudes on immigration could affect party choice, as voters “sort”, they move to the party that shares their policy positions on immigration (Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen and Dahlberg2017). On the other hand, attachments to a party may shape voters' attitudes toward immigration as they follow party cues (Lenz Reference Lenz2009; Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017; Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen and Dahlberg2017). In particular, voters who identify strongly with their party may be more sensitive to cueing. So it may paradoxically be the case that the same party identification that shields these voters from voting for other parties makes them more susceptible to moving to more extreme policy positions on immigration if their party does the same.

The effect of the politicization of immigration issues on the support for religious parties may be visible in particular in a system with multiple religious parties, where different parties have pursued diverging policy agendas. To this end, the electorates of multiple religious parties in the Netherlands are studied.Footnote 2 The Netherlands has a diverse set of religious parties: Christian-democratic, Christian-social, and conservative Christian. In recent times, these have pursued different policy agendas when it comes to immigration and national identity (Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013). This article shows that immigration attitudes are related to supporting these parties since 2002, when immigration became an important political issue.

This article has the following structure: the first sections formulate the expectations about the relationship between voting for religious parties and immigration, propose the mechanisms between voting and policy attitudes and introduce the control variables. The next section focuses on the case selection and discusses the three parties under study, their historical development, and their positions on immigration, civic integration, and national identity. The following section discusses the research methods. This study uses eight different Dutch Parliamentary Election Studies, spanning more than two decades to study how the party politicization of immigration has affected the electorates of these parties. The empirical results of these analyses are discussed next: first for the over-time relationship between voting and immigration attitudes, and then for the mechanisms of cueing and sorting. The final section draws conclusions about the hypotheses.

BEYOND IMMUNIZATION

Ever since the seminal work of Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967), political scientists understand politics in terms of political conflicts between groups with specific interests and identities. Models of the political space can be made to understand these conflicts. The dominant model of West-European party politics sees the European political space as two-dimensional (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kitschelt and McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1997; Pellikaan, Van der Meer, and De Lange Reference Pellikaan, Van der Meer and De Lange2003; Reference Pellikaan, De Lange and Van der Meer2007; De Lange Reference de Lange2007; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Van Kersbergen and Krouwel Reference Van Kersbergen and Krouwel2008; De Vries Reference De Vries2018). The meaning of these dimensions has changed between the 1970s and the 2010s.Footnote 3 In the 1970s, the political space was structured by two dimensions: the first dimension is a moral dimension that divided parties and voters which believed that the government should be neutral toward conceptions of the good life and voters and parties that believed that the government had a role in upholding the traditional conception of morality which was justified on Biblical grounds. This religious cleavage has strong historical roots and reflects the age-old conflict between church and state (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). The second dimension is an economic dimension that divides parties and voters that supported government intervention to create greater economic equality and voters and parties that believed that laissez-faire policies created better economic outcomes even at the cost of greater inequality. By the early 2000s, the structure of the political space had changed due to globalization. The exact timing of this change differs between countries. Competition on the economic dimension was reinvigorated due to economic globalization. The moral dimension was “replaced” by a cultural dimension that concerned questions like immigration, national identity, and civic integration. Parties that favor a strong demarcation of national borders and seek to protect their national identity are divided from parties that favor immigration and a more multicultural conception of national identity.

The rise of this new dimension can be seen in the growing support for radical right-wing populist parties that oppose immigration and seek to protect the national identity from foreign influence. Evidence suggests that religious communities have been “immunized” against these developments (Arzheimer and Carter Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009, 1005; Immerzeel, Jaspers, and Lubbers Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013; Montgomery and Winter Reference Montgomery and Winter2015, 399). As religious communities tend to be closely linked to religious parties, these voters are encapsulated (Arzheimer and Carter Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009, 988). Their strong party identification has a “vaccine effect” that protects them from the appeal of radical right-wing populism (Arzheimer and Carter Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009)

In this view, religious voters as part of networks of religious organizations are protected from the changes in the “outside” world. Yet attitudes about immigration and religiosity are not necessarily unrelated. There are different ways in which religion and attitudes toward immigration can correlate. Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche (Reference Bloom, Arikan and Courtemanche2015) differentiate between religions as a social identity and religious values such as compassion. If a religious person's religious identity is activated, this will lead to a heightened tendency to protect the in-group and see outsiders as dangerous, increasing opposition to immigration (Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche Reference Bloom, Arikan and Courtemanche2015, 2). If in contrast religious values, like compassion, are activated within religious individuals, they will become more sensitive to the needs of disadvantaged groups such as refugees (Knoll Reference Knoll2009; Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche Reference Bloom, Arikan and Courtemanche2015, 3).

Given that religion and immigration can be related in different ways, it is no surprise that in country-comparative research indicates that so far the link between voting for Christian-democratic parties and anti-immigration sentiments is inconsistent at best (Duncan Reference Duncan2015, 585–86). Like religious voters, Christian-democratic parties can hold different positions on immigration. Moreover, the saliency of migration as a political issue differs between countries and time periods, therefore one can see voting for Christian-democratic parties and immigration attitudes is unrelated, negatively related, and positively related.

More than any other issue, immigration is the key issue that constitutes the new cultural dimension. Political parties politicize the issue of immigration by paying attention to it. In this article, we follow the issue of competition literature in understanding that the attention parties spend on issues is primarily driven by party competition (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989, 6; Meguid Reference Meguid2008; Green-Pedersen and Otjes Reference Green-Pedersen and Otjes2019). In this case, when anti-immigration parties gain support, other, established, parties will spend more attention to immigration (Green-Pedersen and Otjes Reference Green-Pedersen and Otjes2019). When parties politicize the issue, it would be reasonable to expect it to also matter for the vote choice of citizens. Crucially for this article, the expectation is that views about immigration will also matter for those who cast their vote for religious parties.

(1) Voting Hypothesis: When parties politicize immigration, the relationship between the likelihood of voting for religious parties and voter positions on immigration is greater than when parties do not politicize immigration.

MECHANISMS BETWEEN ATTITUDES AND VOTING BEHAVIOR

Two mechanisms may underlie how party and voter positions relate: sorting and cueing. The traditional Downsian idea of voting behavior comes down to sorting: citizens vote for the party that is closest to them (Downs Reference Downs1957; Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen and Dahlberg2017, 1179–80). Sorting means that voters switch parties based on their positions on immigration. That is when policy differences between the various religious parties become apparent and salient for voters those who favor a more restrictive immigration policy no longer vote for the party with the most liberal immigration policy but opt for the party that is more anti-immigrant. In this model, the causal relationship flows from the opinions of voters to their choice for a party.

Cueing proposes a reversed relationship. Party preferences shape voters' views about issues (Lenz Reference Lenz2009; Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen and Dahlberg2017, 1,178): that is voters observe the changes in the immigration policy in the party they feel close to and take over these views. Students of cueing emphasize that voters are only rational within bounds (Steenbergen, Edwards, and De Vries Reference Steenbergen, Edwards and De Vries2007, 17): citizens may use the position of the party of their first preference as a heuristic in order to determine their position on an issue that is newly politicized by parties. Group loyalty is an important driver of this relationship (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017): party identification plays a major role in this process of cueing (Slothuus Reference Slothuus2016, 304). Voters who feel more attached to their party are more sensitive to cues that parties give than voters who are less loyal to their party. Therefore, one would expect that the cueing matters more for voters of religious parties, who are embedded in networks around the party.Footnote 4 The stronger this bond to the party is, the more likely cueing effects will occur. If cueing is the driving force behind this change, the constituency of a party can change their opinion about immigration but no voter would need to change their party preference. Therefore, we expect that:

(2) Cueing Hypothesis: the more voters that identify with their party, the more likely that they will adapt to the positions of their party.

CONTROL VARIABLES

In addition to these factors, other indicators that also predict voting for Christian-democratic parties will be included in the analyses as control variables. The first set of control variables comes from their historic position as religious parties defending a moral conception of the government. Therefore, religion, moral attitudes, and age may matter. Religion and voting for religious parties are obviously entwined: these parties are embedded in religious communities. Voting for these parties reflects the old religious cleavage between church and state (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). The central predictor of voting for Christian-democratic parties is being religious (Knutsen Reference Knutsen2004; Duncan Reference Duncan2006, 472; Van der Brug, Hobolt, and De Vreese Reference Van der Brug, Hobolt and De Vreese2009; Botterman and Hooghe Reference Botterman and Hooghe2012, 13; Duncan Reference Duncan2015, 587). Although non-Christian voters may vote for these parties, Christian voters are more likely to vote for religious parties. The decline of Christian-democratic parties is both the result of declining religious affiliation and a decreasing loyalty of religious voters to religious parties (Te Grotenhuis et al. Reference Te Grotenhuis, Eisinga, van der Meer and Pelzer2012). Due to historical differences, some parties may be more attractive for Catholics and others for Protestants (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967, 33–41). It is not just the membership of religious communities that matters, but also the policy preferences related to morality. When it comes to the conflict between individual liberty and traditional morality, religious parties and voters tend to side with the latter (Duncan Reference Duncan2015, 581). Therefore, the expectation is that morally conservative voters are more likely to vote for religious parties. Moreover, religious parties have tended to be strong in the period of “frozen party systems” and since then their support has declined. This means that older generations were more likely to be socialized to vote for these parties than younger generations (Duncan Reference Duncan2006, 471; Duncan Reference Duncan2015, 580). Therefore, the expectation is that older voters are more likely to vote for religious parties.

The second set of predictors has to do with the economic issues. The conflict between economic classes was the second cleavage that structured party preferences during the period of frozen party systems. In general, factors related to this dimension (class, economic preferences) are likely to play a limited, secondary role compared to the first set of factors. The first dimension is the economic dimension: religious parties tend to have center-right positions on economic issues (Duncan Reference Duncan2015, 580). It is likely that their voters reflect this and that voters with right-wing economic preferences are more likely to vote for religious parties. Despite their center-right orientation, Christian-democratic parties have a cross-class appeal uniting religious voters from the working and middle class (Duncan Reference Duncan2015, 579). Therefore, the expectation is that there is no relationship between class and voting for religious parties.

Gender and political trust are also included in the analyses: Duncan (Reference Duncan2015; Reference Duncan2017) shows that there is no relationship between gender and voting for religious parties, although historically women were more likely to vote for these parties. Finally, political distrust plays a role in whether voters vote for government parties (Miller and Listhaug Reference Miller and Listhaug1990; Hetherington Reference Hetherington1999). Therefore, this variable is included with the expectation that voters with low political trust are more likely to vote for religious parties’ government experience but less likely to vote for religious parties without this experience.

CASE SELECTION

This article looks at the electorates of three religious parties in the Netherlands: the Christen-Democratisch Appèl (Christian Democratic Appeal, CDA), the Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij (Political Reformed Party, SGP), and the ChristenUnie (ChristianUnion, CU) and its predecessors, the Reformatorisch Politieke Federatie (Reformed Political Federation, RPF) and the Gereformeerd Politiek Verbond (Reformed Political League, GPV). This section will motivate the selection of these parties.

The key goal of this article is to understand how voters of religious parties have responded to the politicization of immigration policies by political parties. The ideal case is a country that has multiple religious parties and where one can pinpoint the moment where immigration issues became politicized exactly. The Netherlands is this ideal case: for as far as they have religious parties in their parliament, most West-European countries only have a single large, catchall Christian-democratic party. There are five West-European countries that have (had) multiple religious parties in parliament: Germany, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. Germany has the Christlich Democratische Union (CDU) and Christlich Soziale Union (CSU); Belgium has Christen-Democratisch & Vlaams (CD&V) and the Centre Démocrate Humaniste (CDh); Italy has a number of Christian-democratic parties that were formed after the collapse of Democrazia Cristiana (DC); Switzerland has the Christlichdemokratische Volkspartei (CVP), the Evangelische Volkspartei (EVP), and the Eidgenössich-Demokratische Union (EDU); and the Netherlands has the CDA, CU (its predecessors), and SGP. Germany and Belgium are difficult cases because these parties compete in different regions (Bavaria and the rest of Germany and Flanders and Wallonia). Italy is a difficult case because of the organizational instability of these parties. Both Switzerland and the Netherlands offer a similar constellation of parties, but the key difference here is that in the Netherlands, the on-set of party politicization of immigration was sudden (Kriesi and Frey Reference Kriesi, Frey, Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008), while in Switzerland, this was more gradual (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2015). Therefore, the Dutch case is selected. The selection is also relevant for the cueing hypothesis, as we have a case where party and electorate have stronger ties, namely the SGP where voters identify strongly with the party and a case where party and electorate have weaker ties, in particular the CDA, which has developed into a catchall party and their electorate tends to identify less with their party.

RELIGIOUS PARTIES AND IMMIGRATION IN THE NETHERLANDS

The Netherlands has always been diverse in religious terms. It has both strong Catholic and Protestant communities. Until the 1970s, Dutch society was organized in pillars, communities that followed religious lines: Catholics were part of the Catholic pillar and Protestants of a Protestant pillar. Pillars were tightly knit networks of organizations (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1968). Voters were encapsulated in their pillars and therefore were closely tied to the religious parties (Arzheimer and Carter Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009, 991). In the 1960s and 1970s, the pillars weakened and with that the support of the major religious parties declined; voters became less religious and at the same time the almost one-on-one relationship between Catholicism and voting for a Catholic party and Protestantism and voting for a Protestant party weakened (Te Grotenhuis et al. Reference Te Grotenhuis, Eisinga, van der Meer and Pelzer2012).

The Netherlands has a diverse set of religious parties. These are rooted in the historical cleavage between church and state and the cleavage between Protestants and Catholics. However, more recent political and theological developments also affected their formation. Figure 1 shows its electoral support between 1994 and 2017. The largest religious party is the CDA. This party was formed in 1980 as a merger of three religious parties: the Catholic People's Party (Katholieke Volkspartij, KVP), the Christian-Historical Union (Christelijk-Historische Unie, CHU), and the Anti-Revolutionary Party (Anti-Revolutionaire Partij, ARP). The latter two had their strongest support in two different Protestant churches: the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederlands-Hervormde Kerk, NHK) for the CHU and the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands (Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland, GKN) for the ARP. The NHK was the largest Protestant church in the Netherlands. It had more liberal and more conservative tendencies within it. The GKN had split from the NHK. It had a more conservative orientation.Footnote 5 Until 1998, the CDA was the largest party on the right side of the political spectrum. The party has moderate right-wing positions on economic and moral issues such as same-sex marriage.Footnote 6 When it was out of government between 1994 and 2002, a government of social democrats, progressive liberals, and conservative liberals adopted liberal legislation on many moral issues. Therefore, they declined in saliency (Aarts and Thomassen Reference Aarts and Thomassen2008, 212). The CDA is a catchall party, with a broader appeal than the SGP and CU, in particular among right-wing secular voters (Irwin and Van Holsteyn Reference Irwin and Van Holsteyn2008).

Figure 1. Share of the votes of Dutch religious parties

In addition to the CDA and its predecessors, the Netherlands had always had different religious parties. The oldest of these is the SGP, which was founded in 1918 by the members of the Reformed Congregations (Gereformeerde Gemeenten, GG), a community of pietistic Calvinists (Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 83; Van Lieburg Reference Van Lieburg, Vollaard and Voerman2018). The SGP still is part of a network of social organizations, media, and schools related to Reformed Congregations and similar churches (Exalto Reference Exalto, Vollaard and Voerman2018, 48–49). The SGP has been characterized as “extreme and right-wing but not right-wing extremist” (Lucardie Reference Lucardie, Holsteyn and Mudde2002, 74). The party has conservative positions on most issues, which it justifies on Biblical principles (Van Holsteyn, Koole, and Den Ridder Reference Van Holsteyn, Koole, Den Ridder, Vollaard and Voerman2018, 121).Footnote 7 The SGP was anti-papist, which they based on the original version of the Article 36 of the Belgian Confession (1561). This holds that the government “should suppress and eradicate all idolatry and false religion” (translation by Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 83).

In 1944, a religious split occurred in the GKN about a theological issue (Klei Reference Klei, Hippe and Voerman2010, 12; 2011, 32).Footnote 8 A new congregation was formed by the Reformed Churches (Liberated) (Gereformeerde Kerken (Vrijgemaakt), GKV). This led to tension within the ARP. In 1948, the GPV was founded in 1948 by former ARP members who had joined this new church.Footnote 9 The GPV won its first seats in 1963.Footnote 10 The GPV defended the network of organizations around the GKV from outside influence (Klei Reference Klei, Hippe and Voerman2010, 22; Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 85). In the 1960s and 1970s, the ARP began to cooperate intensively with the CHU and KVP. This led to resistance within the ARP's right flank (Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 85–86). Many of those who were upset with the course of the ARP felt that the GPV represented them better. The by-laws of the GPV, however, prevented those who were not a member of the GKV from joining the party (Koole Reference Koole1995, 138). In 1975, these GPV-sympathizers together with other right-wing groups that had split from the ARP formed their own party, the RPF. In 1981, they entered the parliament. The RPF and the GPV shared similar policy positions. They were conservative on moral issues. In the 1990s, they both moved to the center on economic issues (Klei Reference Klei, Hippe and Voerman2010, 28; Van Mulligen Reference Van Mulligen, Hippe and Voerman2010, 46–47). On issues of immigration and civic integration, the GPV in particular was quite conservative (Klei Reference Klei, Hippe and Voerman2010, 26). In the 1990s, the GPV opened itself up to non-GKV members. This allowed for cooperation between the GPV and RPF in the 1990s (Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 86). In 2001, the two parties merged to form the CU. The CU further continued on the “Christian-social” course of its predecessors: conservative on moral issues, but closer to the left on economic issues (Harinck and Scherff Reference Harinck, Scherff, Hippe and Voerman2010).

The politicization of immigration issues by political parties in the Netherlands was sudden. The year can be exactly pinpointed: 2002 (Pellikaan, Van der Meer, and De Lange Reference Pellikaan, Van der Meer and De Lange2003; Reference Pellikaan, De Lange and Van der Meer2007; Aarts and Thomassen Reference Aarts and Thomassen2008, 212; Kriesi and Frey Reference Kriesi, Frey, Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Van Kersbergen Reference Van Kersbergen2008, 269–70; Otjes Reference Otjes2011; Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 79). Before 2002, immigration policy was dealt with in a non-politicized fashion.Footnote 11 Public dissatisfaction with Dutch immigration policy existed before but no party was successfully able to politicize it (Duncan Reference Duncan2006, 479). Until in 2002, a new party was formed by maverick columnist and sociology professor Pim Fortuyn, the List Pim Fortuyn (Lijst Pim Fortuyn, LPF). Fortuyn was a vocal opponent of the Dutch immigration policy: he feared the growing influence of Islam in the Netherlands. He proposed to close the Dutch borders for immigrants until issues with civic integration were dealt with. Fortuyn's support grew in the polls. Civic integration, immigration, and the place of Islam in society became a major political issue in the campaign. Fortuyn was shot by an animal activist days before the election; his party won an unprecedented 17% of the vote. Despite Fortuyn's death, immigration remained a dominant issue in Dutch politics, with other parties taking over the position of the LPF as an anti-immigration advocate.

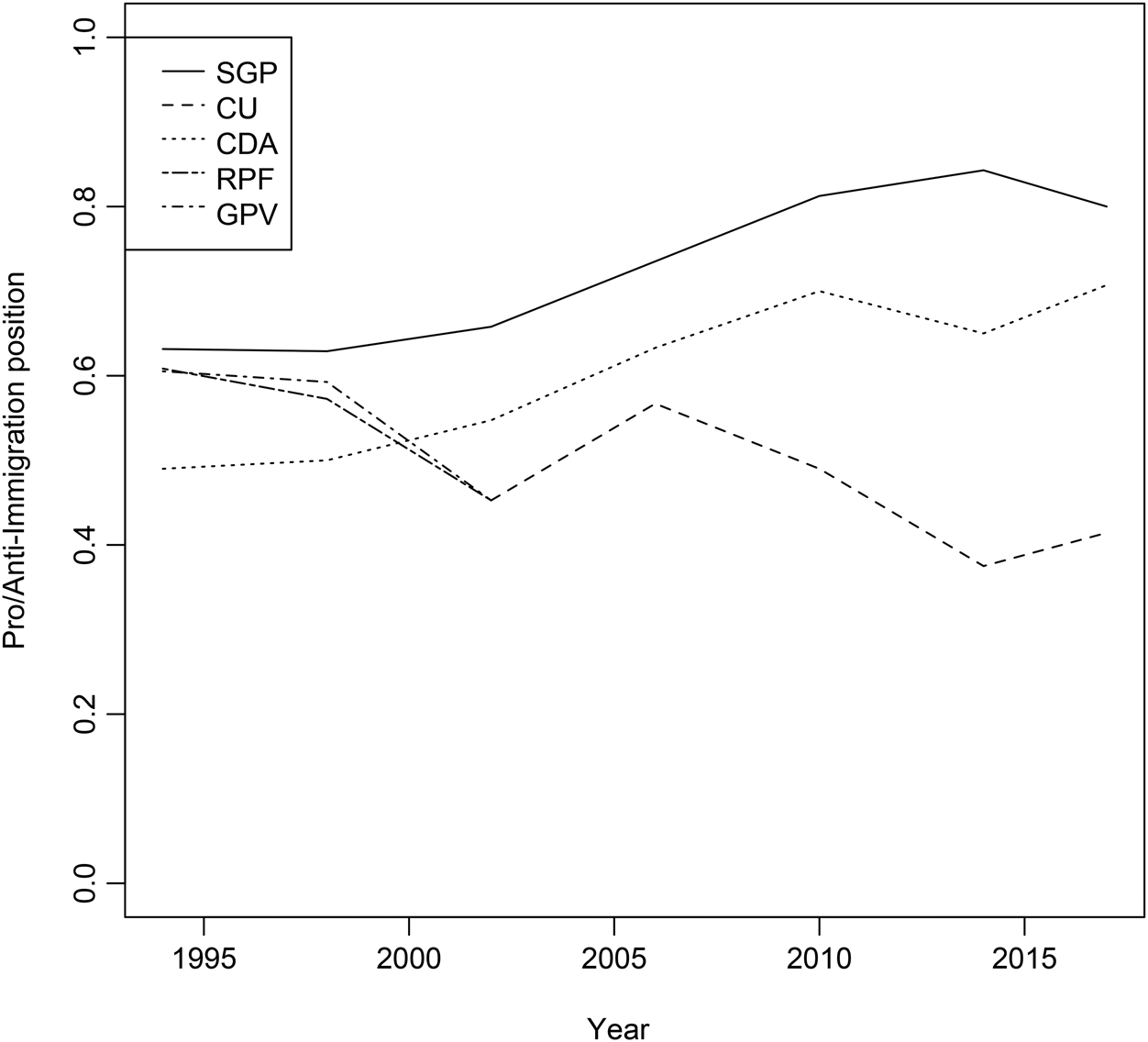

The parties responded in different ways to the changed political circumstances. Figure 2 visualizes their policy positions. Before 2002, the CDA took a centrist position on immigration. In contrast, the SGP, RPF, and GPV favored a more restrictive policy on immigration. The CDA even spoke positively about multiculturalism and saw Dutch society as a mosaic of different groups, new and old, with their own traditions (Kennedy, Ten Napel, and Voerman Reference Kennedy, Ten Napel and Voerman2011, 124–25). After 2002, the CDA moved to the right on immigration. In its view shared, Judeo-Christian values were necessary in the view of the party for the successful integration of immigrants into Dutch society (Van Kersbergen Reference Van Kersbergen2008, 270–72; Van Kersbergen and Krouwel Reference Van Kersbergen and Krouwel2008, 406; Kennedy, Ten Napel, and Voerman Reference Kennedy, Ten Napel and Voerman2011, 125–27; Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 83). Voters also recognized this shift (Aarts and Thomassen Reference Aarts and Thomassen2008, 43).

Figure 2. Immigration positions of Dutch religious parties. Based on expert surveys of Laver and Mair (Reference Laver and Mair1999), Benoit and Laver (Reference Benoit and Laver2006), and Bakker et al. (Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks and Vachudova2015)

For the SGP, the Belgian Confession was a key inspiration for its position on new cultural issues, but now Islam was swapped in for Catholicism: the SGP considers Islam to be on equal footing with Christianity (Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 85; Van Holsteyn, Koole, and Den Ridder Reference Van Holsteyn, Koole, Den Ridder, Vollaard and Voerman2018, 122). Hence it has been reticent about allowing visible expressions of Islam such as mosques with minarets (Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 85). Existing evidence suggests that the SGP has voters with more restrictive attitudes toward immigration (Immerzeel, Jaspers, and Lubbers Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013). Vollaard (Reference Vollaard2013, 85) characterizes the CU response as “creative”. The party has branched out to Christian-migrant communities (Vollaard Reference Vollaard2013, 87). Moreover, it has advocated for a more lenient policy toward refugees, for instance championing a general pardon for asylum seekers who arrived in the Netherlands as children. It justifies this on Biblical grounds, citing Leviticus 19:34–35 in their manifesto: “When a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not do him wrong. The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself”Footnote 12. As can be seen in Figure 2, between 1998 and 2017, the CDA and the SGP drifted to the anti-immigration on the issue. The CU in contrast moved to the pro-immigration side.

METHODS

This article analyzes the support for three religious parties in the Netherlands over time. To this end, eight surveys of the Dutch Parliamentary Election Studies between the 1994 and 2017 are combined (SKON et al. Reference Thomassen1994; Reference Kamp, Aarts, Van der Kolk and Thomassen1998; Reference Irwin, Van Holsteyn and Den Ridder2003; Reference Brinkman, Van der Kolk, Aarts and Rosema2007; Reference Thomassen2012a; Reference Van der Kolk, Aarts and Tillie2012b; Reference Van der Kolk, Tillie, Van der Erkel and Damstra2017).Footnote 13 Two questions are examined. The first question is: did the role of immigration attitudes in determining voting for religious parties changed before and after this issue was politicized by parties? The second question is: what drives this change?

The first hypothesis is that after the politicization of cultural issues by political parties, views about immigration are more strongly correlated with voting CU, SGP, and CDA. To examine this expectation, vote choice, views about immigration, and the moment of politicization of immigration by parties are included in the model. First, vote choice. Each survey has a question, which party an individual voted for in the elections. Voting for the SGP, CDA, and CU is examined.Footnote 14 To capture the politicization of immigration issues by parties, a dummy variable is included. This was zero before 2002 and is one afterwards. Immigration attitudes are measured with a single item that concerns whether foreigners should adapt to Dutch culture.Footnote 15 The differences between the CU on the one hand and the SGP and CDA on the other hand are larger when it comes to immigration, but when it comes to civic integration, this measure is likely to underestimate the size of the effects. Table 1 provides an overview of the descriptives of key variables.

Table 1. Descriptives

A number of control variables are included in the analyses concerning the first hypothesis: first, related to the religious nature of these parties. The DPES includes a question about the respondents' religion. Since different answer categories were used in different surveys, the lowest level of aggregation that is possible between surveys is to differentiate between Protestants, Catholics, and those belonging to other or no religion.Footnote 16 Differences between question wording and categorization do not allow one to assess how citizens that are members of specific Protestant congregations vote over time.Footnote 17 SGP and CU are expected to perform well among Protestants and CDA among Catholics and Protestants. The second indicator related to the religious nature of these parties is an opinion item about moral issues. Each survey contains an item whether respondents favor or oppose euthanasia.Footnote 18 Third is year of birth: each survey has an item on year of birth.

There are a number of items related to the economic profile of these parties. First, voters' views about economic issues, an item to measure support for income redistribution is used.Footnote 19 Second, an item about social-economic status is included: self-identification on a five-point class-ladder. The analysis employs a dichotomy split between working class on the one hand and middle class on the other. A binary question about the respondent's self-identified gender (female one, male zero) is included as well as a two-item scale on political distrust.Footnote 20

In order to see the change in the electorates over time, we run three separate multilevel logistic regressions, one for each party: one regression to see whether voters support CU (or its predecessors), one to see whether they vote SGP, and one to see whether they cast their ballot for the CDA. Interactions are used to assess whether there are significant differences in how predictors perform over time. As a number of different surveys from different years are combined, multilevel logistic regression with each year as a level is used.

The second question is what drives the changing role of immigration policy attitudes: is this sorting or cueing? Ideally, one would have a multi-wave survey that would allow one to examine the interplay between elite positions and voter positions: voters responding after a party signaled its ideological shift (cf. Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen and Dahlberg2017). Such surveys are not available for the period before the 2002 elections. One can see which pattern is most likely in the following way: focusing on the 2002 election, we compare the respondents in 1994 and 1998 survey to those in the 2002 survey, specifically examining the immigration attitudes of those that stayed loyal to the party they voted for in 1998, those who switched to a new party, and those who switched away from their party. If cueing is the dominant mechanism, switchers would not be significantly different in their views about immigration than non-switchers. If switching is the dominant mechanism, there would be a significant difference between those who switch and those who stay. The hypothesis explicitly says that cueing is more likely when voters identify strongly with the party. We measure this with an indicator on party identification. As we do not have a multi-wave survey, we cannot directly correlate changes in opinion with party identification. The aggregate numbers allow us to say something about the strength of the patterns however.

REGRESSION RESULTS

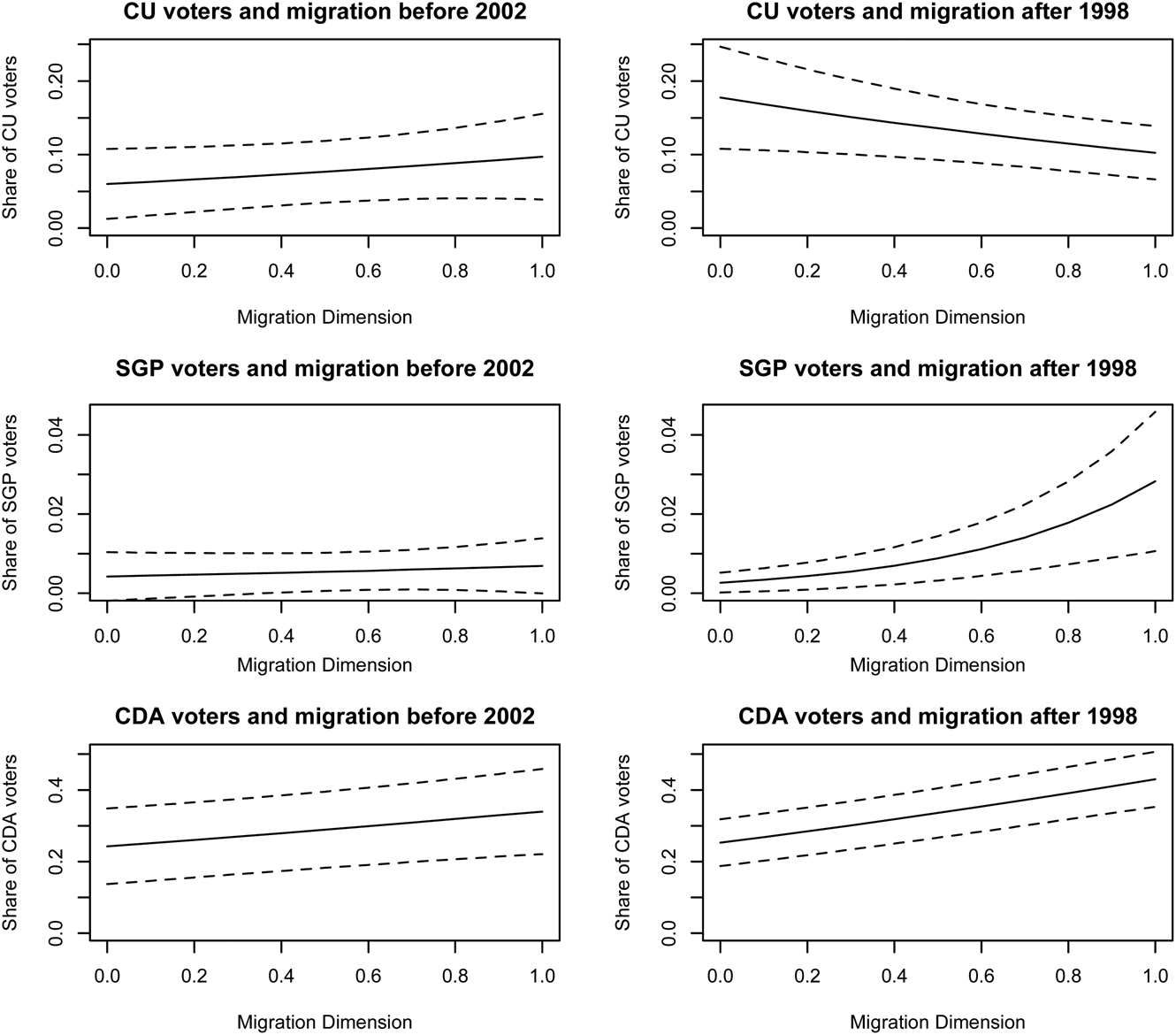

The first question we look at is the effect of immigration attitudes on voting CU, SGP, and CDA over time. To answer this question, three models are presented in Table 2: each model looks at what kind of voters support one of the three parties.Footnote 21 Figure 3 visualizes these patterns.

Table 2. Logistic regression results for party choice

*>0.05; **>0.01.

Figure 3. Predicted share of votes for the CDA, CU, and SGP on the basis of voters' position on immigration. Predicted chance of voting for each for the three parties with 95% confidence intervals for different positions on the migration issue for Protestants (not Catholics) who have moral views one standard deviation more conservative than mean, while keeping moral positions, political distrust, at their mean, and class and gender at their median. Based on Models 1–3. The Y-Scales are not the same in a column, they are the same across rows

Our key expectation is that after 2002, attitudes about immigration mattered more for the likelihood to vote CDA, CU, and SGP then before. There would be a positive relationship between anti-immigration views and voting CDA and SGP, which took a more restrictive view on immigration, and negative relationship for the CU, which took a more liberal view on immigration. The models show that before 2002, there is a positive relationship between restricting immigration attitudes and voting for each of the three parties. Yet for the CU or SGP, this relationship is not significant. The lines in Figure 3 are relatively flat, and for CU and SGP, any increase falls within the confidence interval. After 2002, the figures are different, and the effect of immigration attitudes is stronger for each of the three parties and significant when one goes from one side of the spectrum to the other. The most striking thing however is that the direction of the relationship has reversed for the CU. The more anti-immigrant a voter is, the less likely they are to vote for the CU. This is in line with the voting hypothesis.

The control variables mainly conform to our expectations. As expected, Protestant voters are more likely to vote CU, CDA, and SGP. Catholics are less likely to vote CU or SGP but more likely to vote CDA. Moral views matter for the likelihood of voting CU. They matter even more strongly for the likelihood of voting SGP. The effect on voting for the CDA is much smaller. This indicates already something of the catchall nature of the CDA. When it comes to year of birth, there is a strong difference between CU and SGP on the one hand and CDA on the other: as expected, the CDA attracts older voters, those socialized during pillarization, but in contrast to the expectation that the CU and SGP attract younger voters. This may be a sign that the CU and SGP are still part of pillar-like networks, where younger voters are socialized into voting for these parties.

When it comes to economic issues, the CU attracts voters with more left-wing economic issues, the SGP and CDA voters with more right-wing economic issues.Footnote 22 When it comes to class, the CU and CDA attract middle class voters. The SGP's appeal does not differ between working or middle class voters.

Finally, there are gender and political trust. The CU is stronger among female voters. The CDA and SGP are as strong among female as they are among male voters. Finally, there is political distrust: as expected the CDA attract voters that have high political trust. The same is true for the CU.Footnote 23 There is no significant relationship between voting SGP and political trust.

EMPIRICAL EXAMINATION OF THE MECHANISM

The second question is what drives these effects? Table 3 shows the average immigration positions per year of four groups per party: its voters in the period 1994–1998; those who stayed with the party in 2002; those who vote for the party in 2002 but did not vote for the party in 1998; and those who voted for the party in 1998 but not in 2002. In 2002, the CDA received an influx of voters that were significantly more conservative on immigration than both those who voted for the party in 1994–1998 and those who stayed loyal to the party in 2002. What is striking, however, is that in 2002, loyal voters are also significantly more conservative on immigration than the voters in the 1994 and 1998 survey. This provides evidence of both cueing (the increase among the loyalists) and of switching (with the influx of conservatives in 2002).

Table 3. Migration attitudes 1994–2002

With 95% confidence interval.

The group of CU voters is smaller; therefore, the standard errors are considerably larger. In 2002, the voters who left the CU were considerably more conservative on immigration than those who stayed with the party. There are no significant differences in the immigration attitudes between those who voted for the party in 1998 and those who stayed loyal to the party in 2002. This provides evidence of sorting: the CU lost its anti-immigration wing in 2002.

The group of SGP voters is even more limited: for some categories, the number of respondents is only one. A single respondent is not a reliable source and therefore we do not show them. Yet this already shows how small the voter exchange between the SGP and other parties is. Still the SGP voters are significantly more conservative on immigration issues in 2002 than before. This cannot be explained by sorting.

So when it comes to the underlying mechanism, the evidence is mixed; there is some evidence of sorting in particular in 2002: the CU lost the conservative segment of its constituency, while the CDA saw an influx of voters with conservative views on this issue. Yet, the SGP voters became considerably more conservative without much voters switching to or from the party. Our hypothesis is that voters that are more embedded in the pillarized networks are more likely to be affected by cueing. Therefore, we have included the share of party adherents as an indicator of inclusion in these networks. In both 1994–1998 and 2002, SGP voters are more likely to consider themselves party adherents than CDA or CU voters. This indicates that party adherence is likely the driving force behind accepting party cues. The strength of partisan identity is a better explanation for the patterns we found than embeddedness in religious networks. Weekly church attendance cannot be the driving force behind cueing: CU voters score as high or higher as SGP voters on church attendance but they are more likely to sort.Footnote 24

CONCLUSION

Since 2002, immigration has moved from a marginal issue in Dutch party politics to become one of the key issues. The views of religious parties on immigration in the Netherlands have bifurcated: the CU adopted a more liberal course on this issue, while the CDA and SGP adopted a more conservative course. In line with the voting hypothesis, these changes are reflected in their electorates. The CU voters became more liberal and the SGP and CDA voters became more conservative. The results indicate that the idea of “immunization” only goes so far: previous evidence shows that religious voters are immune to the allure of anti-immigration parties, because they are loyal to religious parties. This study shows however that they are not immune to the politicization of immigration and national identity by parties. Attitudes toward immigration are a driver to voting for religious parties, if the issue is politicized and parties have different views.

Yet this is not even the entire story: for some parties with particularly loyal voters, their attachment to their party may make them more sensitive to the politicization of immigration. In line with the cueing hypothesis, we find evidence that parties whose electorates are most loyal, in particular the SGP, also see the largest shifts in opinion to meet the more conservative views of the leadership of their own party. For the CU and CDA, there is evidence that sorting played a role: as one party lost its conservative flank, the other saw an influx of voters who had more conservative views on immigration. This evidence is only preliminary and a more robust experimental or quasi-experimental research design that looks at the mediating effect of the party and religious identification on cueing would be necessary to fully corroborate this hypothesis; but this evidence suggests that party identification can be the link between voting for a party and adopting their positions.

So what do these results mean beyond the borders of the Netherlands, for countries where religious voters are not divided between parties that are more and less supportive of immigration? For one, it shows that party positions matter. Christian-democratic parties hold many different positions on the issue of immigration. This is the result of the fact that both conceptually and empirically different elements of religion, such as its role as important social identity and its teachings of compassion, can match with both pro-immigration and anti-immigration positions (Arzheimer and Carter Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009; Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche Reference Bloom, Arikan and Courtemanche2015). The European Christian-democratic party family shows considerable variance on this issue: there are Christian-democratic parties that are more supportive of immigration (like the German CDU, the Walloon CDh, or the Italian Alternative Popolare) and those that are more opposed to immigration (like the Bavarian CSU, the Austrian Österreichische Volkspartei, or the Slovenian Nova Slovenija—Krščanski Demokrati). It is likely that the views of their voters on immigration are either positively or negatively related to the likelihood of voting for these parties. Voters of religious parties are not immune to the increased political competition over immigration, civic integration, and national identity. A logical next step in the study of immigration attitudes and voting for religious parties is to take a comparative approach: and see how the different positions religious parties take affect voting patterns.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048319000518.