INTRODUCTION

In 2013, Vladimir Putin signed the so-called “anti-gay propaganda bill,” which imposes fines on individuals, who distribute such material, which informs about non-traditional sexual relationships, at minor (Telegraph 2013). In many Muslim majority states, such as Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen, Internet is censored on faith-basis, meaning that content which is considered contrary to Sharia or Islam is blocked (Noman Reference Noman2011). In China, “preachers are routinely monitored to ensure their sermons do not diverge from what the Party considers acceptable” (Phillips Reference Phillips2014). In Uzbekistan, unregistered religious groups are declared illegal, and the law “limits home possession of religious materials of all types and formats” (US Department of State 2017, 1).

Why are authoritarian regimes interested in spending government resources to impose such laws? Even though a student of political sciences would intuitively argue that restrictions, such as the ones described above, have less to do with the beliefs of the authoritarian leaders and more to do with pragmatism and their desire to stay in power, comparative research on authoritarian regimes does little to help us to understand the motives of the authoritarian leaders to enforce religiously inspired restrictions. Indeed, if we would make the decision solely based on the content of the comparative research on authoritarianism, we would conclude that God is dead. An illustrative example is provided by a recent article on co-optation, which distinguished between different pressure groups, such as workers and ethnic groups that may threaten the regime, but left religion out of the picture (Schmotz Reference Schmotz2015).

Much of the blame for the ignorance of religion in comparative political sciences is given to the secularization theory (Gill Reference Gill2001; Philpott Reference Philpott2009). Although different versions of the theory exist, common for all of them is the assumption about the decline of religion (for review, see Gorski and Altinordu Reference Gorski and Ates2008; Fox Reference Fox2013, 17–35). Yet, during the past two decades, several observers have concluded that secularization theory is simply not true (e.g., Berger Reference Berger1999). As for the separation of state and religion, a large majority of countries regulate religion, and in many cases regulation has been, contrary to the assumptions of the secularization theory, increasing (e.g., Fox Reference Fox2006). Such findings, together with the improved data availability on regulation, have led to an increase in the number of quantitative studies which discus cross-country differences in regulation of religion (Fox Reference Fox2008; Reference Fox2015), as well as the determinants (Fox Reference Fox2006; Finke and Martin Reference Finke and Martin2014) and consequences (Grim and Finke Reference Grim and Finke2007; Reference Grim and Finke2011; Bloom Reference Bloom2016; Tusalem Reference Tusalem2015) of such regulation. These studies, however, often have global focus and thus cannot inform us about the particularities of the authoritarian countries. Moreover, these studies are relatively isolated from the mainstream political science research. Indeed, the theoretical frameworks which are employed in these studies are often related to the secularization/modernization theory, economics of religion (Stark and Iannaccone Reference Stark and Iannaccone1994), and the clash of civilizations (Huntington Reference Huntington1993). References to the larger institutional set-up of the countries are still scarce, even though there recently has been more and more attempts to bring the state back in (Buckley and Mantilla Reference Buckley and Mantilla2013; Schleutker Reference Schleutker2016).

The current paper aims to build bridges between the research on authoritarianism and the research on regulation of religion by discussing how regulation of religion is used as a tool of authoritarian control. At the conceptual level, the argument of the paper is that positive endorsement of religion can be understood as co-optation, whereas negative restrictions can be understood in light of the regime's aim to prevent, control, and constrain collective action. The suggested conceptualization allows us to draw from the research on authoritarian regimes to distinguish between qualitatively different types of positive endorsement of religion (policy concessions; material benefits; institutional inclusion). Further, the conceptualization makes it possible to rely on the study of social movement resources and thus enables us to understand negative restrictions on religion as the regime's attempt to control the various resources of the religious groups (political role; cultural resources; moral resources; material resources; socio-organizational resources; human resources; leadership resources).

The descriptive part of the paper employs data from the third round of the Religion and State Project (Fox Reference Fox2008; Reference Fox2011; Reference Fox2015; Reference Fox2018) for ca. 70 countries in ca. 2014. With the help of hierarchical cluster analysis, three groups of countries are distinguished based on the way in which religion in these countries is positively endorsed and/or negatively restricted. Further, the qualitative differences between the clusters when it comes to the different types of regulation are explored.

Regarding the explanatory contribution, the paper draws from the research on co-optation and repression in authoritarian regimes in order to understand the determinants of regulation. The emphasis is on strategic interactions between the regime and the religious groups. In particular, it is argued that the supply of regulation (i.e., the capacity and ambition of the dictator to regulate religion) as well as the demand for regulation (i.e., capacity and ambition of the religious groups to threaten the dictator) are important determinants of the positive endorsement and negative restrictions of religion. The theoretical discussion is complemented with predictive discriminant analysis and OLS-regression. The results from these quantitative exercises suggest that according to the theoretical considerations, regime legitimacy claims which are related to religion, or to socialist or communist ideology; level of GDP/capita; as well as the ambition of the religious groups to have an influence on the society are associated to regulation of religion. Thus, it is concluded that future research on regulation of religion in authoritarian regimes should focus more on these aspects.

The paper is organized as follows: After this introductory section, previous research on regulation of religion is briefly described and contrasted to the argument of the current paper. The conceptualization of regulation of religion as co-optation and repression is discussed in section “Conceptualization: Regulation of religion in authoritarian regimes.” Identification of the country clusters and the description of the differences and similarities between the clusters is presented in section “Descriptive evidence: How do the countries cluster when it comes to regulation?”. The explanatory contribution of the paper, including the empirical investigations, can be found in section “Determinants of cross-country differences and similarities in regulation.” Section “Concluding remarks” concludes with some suggestions for future research.

STATE OF THE ART

In UN's (1948) Declaration of Human Rights, article 18 defines freedom of thought, conscience, and religion as the “freedom to change /…/ religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest /…/ religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.” Similarly, Finke (Reference Finke2013, 299) defines religious freedom as “/…/ the unrestricted practice, profession, and selection of religion” (emphasis in original). Gill (Reference Gill2007, 10), however, points out that “religious liberty involves more than the right of personal conscience; it includes a host of policies concerning property rights, education, media ownership, and public speech.” Against these definitions, regulation of religion can be understood as restrictions on religious freedom.

The definitions of regulation of religion vary in their conceptualization and scope. Fox (Reference Fox2008; Reference Fox2011; Reference Fox2015; Reference Fox2018) focuses on government involvement in religion and separates, for example, between discrimination against minority religions; regulation of and restrictions on the majority religion and all religions; and specific types of religious legislation. Grim and Finke (Reference Grim and Finke2006) distinguish between government regulation of religion; government favoritism of religion; and social regulation of religion. These definitions highlight the fact that regulation of religion can be negative (restrictions) or positive (favoritism), it might target different religious groups (minorities, majorities, or all religions), and it can be exercised both by governmental and societal actors.

Both Fox, and Grim and Finke have constructed indicators on regulation of religion, which correspond to their definitions. These indicators are comprehensive in their scope: Fox's Religion and the State Project has data for 1990–2014. Grim and Finke's International Religious Freedom data is available for 2001, 2003, 2005 and 2008. Further, the recent reports by Pew on religious restrictions (e.g., Pew Research Center 2018), as well as the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures-Project (which currently has data for 2007–2016) follow Grim and Finke's conceptualization and operationalizations regarding social and government restrictions. Due to the comprehensive scope and availability of these indicators (all three datasets are freely available online and cover a large majority of the independent countries), current research often follows these two conceptualizations.Footnote 1

As for the determinants of regulation, previous quantitative studies have three characteristics. Firstly, a large majority of these studies include (nearly) all countries for which there is available data (e.g., Fox Reference Fox2006; Buckley and Mantilla Reference Buckley and Mantilla2013; Finke and Martin Reference Finke and Martin2014; Finke, Martin, and Fox Reference Finke, Martin and Fox2017; Mataic Reference Mataic2018). However, as I have previously argued (Schleutker Reference Schleutker2016; Reference Schleutker2019), the determinants of regulation should be studied separately in authoritarian and democratic countries, given that the political context in these two regime types is substantially different. In accordance with this argument, the current study focuses on authoritarian regimes.

Secondly, previous studies employ one or several of the above-mentioned indicators on regulation as dependent variable(s). Thus, some studies aim to explain the different levels of discrimination (e.g., Finke, Martin, and Fox Reference Finke, Martin and Fox2017; Mataic Reference Mataic2018; Schleutker Reference Schleutker2019), others focus on the determinants of government restrictions (e.g., Finke and Martin Reference Finke and Martin2014), and some study the determinants of both negative restrictions and positive endorsements (e.g., Fox Reference Fox2006; Buckley and Mantilla Reference Buckley and Mantilla2013). It is also relatively common to employ one type of regulation as an independent variable to explain another type of regulation. For example, Finke and Martin (Reference Finke and Martin2014) use government favoritism and social regulation to explain government restrictions on religion. As will be discussed below, however, in authoritarian context, it is not particularly useful to treat positive endorsements and negative restrictions separately, but it is important to study which combinations of positive endorsements and negative restrictions the dictator employs in order to control the religious sector of the country.

Thirdly, the study of regulation is isolated from the mainstream comparative political science research. Indeed, the selection of independent variables is usually derived from one of the following three theories: (1) The sociological theory on secularization and modernization (for review, see Gorski and Altinordu Reference Gorski and Ates2008), for instance, by including variables on urbanization and birth mortality. (2) From Huntington's (Reference Huntington1993) theory on the clash of the civilizations, for example, by including dummies for the majority religion affiliation of the country, or by including variables which indicate, e.g., the proportion of Muslims in a country. (3) From the rational choice theory on regulation of religion (Stark and Iannaccone Reference Stark and Iannaccone1994; Gill Reference Gill1998, Reference Gill2007) by including variables on religious demography (e.g., percentage of largest religious group, religious fractionalization). The institutional set-up of the countries is mainly considered by including a control variable for democracy (e.g., Polity score); by studying the influence of judicial independence (e.g., Finke and Martin Reference Finke and Martin2014; Schleutker Reference Schleutker2019); and by including a dummy-variable to distinguish the current and former communist countries from the others (e.g., Finke, Martin, and Fox Reference Finke, Martin and Fox2017; Mataic Reference Mataic2018; Schleutker Reference Schleutker2019). Yet, a more profound connection to the theories of comparative politics is missing. In the current paper, I aim to address this gap by drawing from the theories on comparative authoritarianism. In particular, the paper builds on Gill's (Reference Gill1998, Reference Gill2007) work on cost-calculations of both the religious actors and the regimes and discusses how the capacity and ambition of the religious groups, state capacity, and ideological legitimacy claims of the regime influence regulation.

Even though the research on regulation of religion remains isolated from the mainstream political science and commonly has global focus with an emphasis on one type of regulatory policy only, there is one notable exception, namely Sarkissian (Reference Sarkissian2015), who provides a comprehensive large-N study on regulation of religion in authoritarian countries.Footnote 2 The current paper is greatly indebted to Sarkissian's work. For example, many of the ideas expressed here on the capacity and ambition of the religious groups are inspired by her discussion (Sarkissian Reference Sarkissian2015, chap. 2) about the reasons for why the regime may find even seemingly harmless expressions of religiosity as threatening. Sarkissian's focus, however, contrary to the current paper, is on the restrictions the authoritarian regimes place on religion. Even though she discusses government favoritism and points out that favoritism may be aimed at restricting the favored group (e.g., Sarkissian Reference Sarkissian2015, 27 and chap. 4), she does not systematically discuss cross-country differences in policy concessions, material benefits, and institutional inclusion granted to religious groups. Thus, the current paper adds to Sarkissian's work in that it systematically discusses both the positive endorsement and negative restrictions on religion. Another major difference is that Sarkissian investigates the treatment of both the majority and minority religions, while the current paper focuses on the interactions between majority religion and the regime.

As a consequence of these differences, the classification of the authoritarian countries in the current study is substantively different from the classification by Sarkissian. While Sarkissian (Reference Sarkissian2015, 40ff.) finds there to be four different types of authoritarian countries depending on which religious groups are targeted (all groups; all but one; some groups; none), the current paper distinguishes between three groups based on the mix of positive support and negative restrictions. Further, several countries also cluster differently in the two studies. Perhaps most notably, Sarkissian places countries such as North Korea and Uzbekistan into the same cluster as countries such as Iran and Oman (“countries which repress all groups”), whereas it in the current study is argued that regulation of religion in these countries is qualitatively so different that they need to be placed into different clusters.

Finally, Sarkissian's explanation to the cross-country differences in authoritarian repression is political competition and religious divisions. The current paper also discusses political competition, but points more specifically to the capacity and ambition of both the regime and the religious groups as the causal forces behind regulation. Moreover, as the current paper does not discuss the treatment of minority religions, the role of religious divisions is not considered.

CONCEPTUALIZATION: REGULATION OF RELIGION IN AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES

The research on authoritarian regimes has substantially expanded during the past 20 years. The scholars of comparative authoritarianism have distinguished between different authoritarian regime types (Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Hadenius and Teorell Reference Hadenius and Teorell2007; Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010; Geddes, Wright, and Franz Reference Geddes, Wright and Franz2014), and discussed the ways in which the authoritarian regimes aim to legitimate their rule (Kailitz Reference Kailitz2013; von Soest and Grauvogel Reference Von Soest and Grauvogel2017). Further, several studies focus on authoritarian institutions of co-optation (Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2006; Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008; Wright Reference Wright2008; Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013), repression (Davenport Reference Davenport2007a; Møller and Skaaning Reference Møller and Skaaning2013), and the relationship between co-optation and repression (Conrad Reference Conrad2011; Frantz and Kendall-Taylor Reference Frantz and Kendall-Taylor2014). Legitimacy, co-optation, and repression are now argued to be the key mechanisms behind authoritarian stability (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013; Kailitz and Wurster Reference Kailitz and Wurster2017), and their impact on the longevity of the authoritarian rule is widely studied (e.g., Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Escribà-Folch Reference Escribà-Folch2013; Kailitz and Stockemer Reference Kailitz and Stockemer2016). By drawing from this comparative research on authoritarianism, we can better understand the cross-country patterns in regulation of religion. In particular, it is here argued that, to a certain extent, positive endorsement of religion can be understood as co-optation, whereas negative restrictions can be understood as empowerment rights repression.

Before we proceed with the discussion, it is important to point out the complexity of the religious sector in a country, and the challenges this complexity causes for large-N comparative research. To start with, there are several different types of religious actors, such as majority religion institutions, minority religion institutions, religious political parties, different religious associations, and sometimes even religious terrorist groups. Further, all these groups may be internally quite heterogeneous. The religious institutions, for example, consist of the leadership and the ordinary clergy, and there is usually also considerable geographical dispersion, given that the rural congregations may be hundreds of kilometers away from the administrative center. In addition to the internal heterogeneity of the religious groups, the complexity of the religious sector is influenced by the patterns of co-operation between the religious groups. For instance, religious parties may or may not co-operate with the leadership and the clergy. Finally, the number of religious actors; their relative strength and importance; their goals and strategies; their degree of internal homogeneity; and their patterns of co-operation are likely to vary from country to country.

As a consequence of such complexity, it is difficult to study the determinants of cross-country variation in regulation in detail. To illustrate, consider variable N22 in the RAS3-dataset, which measures the arrest/detention/harassment of religious figures, officials, and/or members of religious parties. Even though the variable informs us about the existence and severity of repression, we do not know who and/or which groups are targeted. In one country, the dictator may target religious parties, in another country the clergy, and in a third one religious figures who are involved with terrorist organizations. To put it differently, even though the general levels of regulation in a country are known to us, in many cases, we do not know which particular groups and actors these regulations aim to address. To overcome the problem, if only at the conceptual level, regulation of religion in this essay is understood as such regulation, which targets one or several actors in the religious sector.

Positive Endorsement of Religion as Co-optation

Co-optation is often understood as the use of some kind of favor by the regime to win over the strategically important groups and individuals in the society. The purpose is, on the one hand, to expand the support base of the regime and, on the other hand, to tie the co-opted groups to the regime, so that they have a vested interest in the survival of the regime. Previous research suggests that dictators co-opt the strategically important groups with policy concessions and material benefits (Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007, 1282). Yet, the focus of the research on co-optation has been on the institutions of co-optation, such as political parties and legislatures (Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2006; Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008; Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013).

To understand why and how religious groups would like to be co-opted, we can rely on the rational choice theory of religious markets. In the rational choice-approach, religious firms are understood as “social enterprises whose primary purpose is to create, maintain and supply religion to some set of individuals” (Stark and Iannaccone Reference Stark and Iannaccone1994, 232). Further, Gill (Reference Gill2007, 44) states that religious firms “seek to spread their brand of spiritual message.” Thus, we would expect the religious actors to trade their support to the regime with material benefits, which help them to provide services to their current members and to obtain a larger market share. For example, as preaching and spreading the message is costly, religious groups, in general, are likely to welcome any financial support from the regime. Thus, it is likely that co-optation through funding is in accordance with the preferences of the religious groups. Indeed, both bishops and clergy, as well as the center and periphery of the religious institutions should prefer additional financing. Even though religious parties do not directly benefit from the funding of religious groups, parties affiliated with the religious groups may wish to see at least some of the groups to be funded generously.

Concerning co-optation through policy concessions, according to the rational choice-approach those religious institutions, which have a monopoly, desire to have an influence on the society and sacralization of the society takes place. By sacralization, Stark and Iannaccone (Reference Stark and Iannaccone1994, 234) mean “that the primary aspects of life, from family to politics, will be suffused with religious symbols, rhetoric, and ritual.” It is here argued that even though religious groups definitely are interested in symbols, rhetoric, and ritual, the main interest of these groups is to get the dictator to introduce (or uphold the already existing) laws and regulations, which govern people according to the principles laid out in the religious teaching. Thus, sacralization may potentially extend to all aspects of the society. For example, Fox (Reference Fox2015; Reference Fox2018) distinguishes between laws on relationships, sex, and reproduction; laws restricting women; other laws legislating religious precepts (these laws are related to, for example, companies); and institutions and laws which enforce religion. Other authors have pointed out that religious groups are particularly interested in having influence over education (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan and Peter1990, 102), as well as over family law and the rights of women and sexual minorities (e.g., Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Laurel Weldon2010; Reference Htun and Laurel Weldon2011).

Regarding the institutions of co-optation, religious groups need to have access to the decision makers in order to advance their preferences regarding material benefits and policy concessions. Such access may be formal or informal, and is not limited to the inclusion of religious parties in the parliament. Indeed, as pointed out by Grzymala-Busse (Reference Grzymala-Busse2016) in the democratic context, there is a broad variety of direct institutional channels the religious actors may have to the decision makers, such as joint church-parliamentary commissions, informal legislative proposals, and consultation. Likewise, it can be assumed that in the authoritarian countries, the institutions of co-optation in regards to religion need to be understood more broadly than as legislatures, parties, and elections.

Negative Restrictions on Religion as Empowerment Rights Repression

Repression can be understood as “state or private action meant to prevent, control, or constrain noninstitutional, collective action (e.g., protest), including its initiation (Earl Reference Earl2011, 263).” It is common to divide between two types of repressive activities. Physical integrity rights repression (PIR) takes the form of, e.g., physical abuse, imprisonment, and killing and is often selective, targeted toward certain individuals, such as leaders of the oppositional groups. Empowerment rights repression (ER) refers to repressive activities, which limit the civil and/or political rights, and thus have an influence on larger groups in the society. Thus, ER aims to constrain collective action by making it more difficult to act against the regime, and by modifying and taming the behavior of the regime opponents (for discussion, see e.g., Davenport Reference Davenport2004, 543f; Escribà-Folch Reference Escribà-Folch2013, 546ff).

Following this logic, we can understand negative restrictions on religion as empowerment rights repression with the aim to prevent, control, and constrain collective action (cf. Sarkissian Reference Sarkissian2012; Reference Sarkissian2015). To distinguish between the different types of restrictive practices, the sociological study of social movements and organizations provides a promising starting point. This scholarship is focused on the study of the rise, mobilization, ideology, and success of social movements (for review, see Walder Reference Walder2009). Consequently, it can help us to understand the collective action power of the religious groups, and the type of restrictions the authoritarian leaders impose on religious groups.

According to the resource mobilization theory (McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977), the success and failure of social movements can be attributed to the various collective action resources these movements have at their disposal. It is further possible to distinguish between different types of collective action resources, namely moral (e.g., legitimacy and celebrity of the group), cultural (e.g., knowledge about tactical repertoires, technical know-how), human (e.g., labor, experience, skills, expertise, leadership), social organizational (infrastructures, social networks, organizations), and material (“financial and physical capital, including monetary resources, property, office space, equipment, and supplies”) (Edwards and McCarthy Reference Edwards, McCarthy, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004, 128). Religious groups have many of these collective action resources at their disposal, for example, public pulpit, political connections, places to meet and organize, organizational resources, financial resources, leadership, civic skills, and congregants (Fox Reference Fox2013, 85–88). These resources may be employed to engage in a political protest, but also to broaden the opposition and bridge between the different opposition groups, which are based on, for instance, class interests or ethnicity (Johnston and Figa Reference Johnston and Figa1988). Consequently, we would expect authoritarian leaders who wish to prevent, control, or constrain collective action, to lay negative restrictions both on the political activities and on the collective action resources of religious groups.

Following this logic, it is further possible to distinguish between qualitatively different types of repressive activities depending on which collective action resources are targeted. As for moral resources, “the moral authority of churches /…/ is the popular perception that the church represents the national interest, a political resource that allows churches to frame and influence policy” (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2016, 3). Repression of moral resources can consist of, for example, the control of the content of the religious sermons, religious material, and religious speech. In extreme cases, propaganda and disinformation may be employed by the regime in order to discredit the moral authority of the religious groups.

Concerning the repression of human resources, the regime may, for example, declare the membership in religious organizations illegal, or apply physical integrity rights repression on individuals who are (active) members of a religious group. Further, it is important to distinguish leadership from other human resources. Indeed, “Leaders are critical to social movements: they inspire commitment, mobilize resources, create and recognize opportunities, devise strategies, frame demands, and influence outcomes” (Morris and Staggenborg Reference Morris, Staggenborg, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004, 171). As a consequence, the authoritarian regimes have a strong motivation to exercise control over the leadership of the religious organizations. For example, government control over clergy nominations is a powerful tool for the regime to make sure that only regime-friendly individuals get positions on top of the religious hierarchy (Sarkissian Reference Sarkissian2015, 35). Further, repression of leadership can take the form of physical integrity rights repression of central figures such as party leaders, bishops, and clergy.

Regarding the repression of material resources, the regime may limit the religious groups' access to material resources through instruments such as heavy taxation, restrictions on voluntary contributions to religious organizations, and regulation of inflows of foreign money. In extreme cases, the regime may even confiscate or nationalize the property of the religious groups. Finally, the regime may impose various restrictions on the socio-organizational resources, which considerably influence the internal workings of the organization, or even ban the organization. Moreover, given that it is in the religious meetings the believers can exchange ideas and opinions, get influenced by the preaching of the leaders, and possibly even discuss strategies concerning anti-regime action, restrictions on religious meetings can be understood as repression of the socio-organizational resources.

Relationship Between Positive Endorsement and Negative Restrictions

The leaders of authoritarian regimes always need to choose between different combinations of repressive and co-optive policies (e.g., Wintrobe Reference Wintrobe2001, 40), and there is some evidence that co-optation influences repression (Frantz and Kendall-Taylor Reference Frantz and Kendall-Taylor2014). Further, co-optation and repression, together with legitimation can be understood as the “three pillars” of authoritarian regime stability (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013). In other words, the research on comparative authoritarianism points out that co-optation and repression should not be studied in isolation from each other. Following this logic, the positive endorsement and negative restrictions regarding religion in authoritarian countries should be studied jointly.

Co-optation increases some of the co-opted group's resources of collective action (e.g., material benefits increase material resources), but at the same time may negatively influence other resources (e.g., co-operation with the regime may weaken the moral standing of the religious groups). Yet, in general, the higher the degree of co-optation, the stronger the co-opted group may grow vis-à-vis the regime. Indeed, even though the dictator hopes that the co-opted group has a vested interest in the survival of the regime, there is always the risk that the co-opted group will at some stage turn from a friend to an enemy. To prevent this from happening, it is reasonable to assume that even the co-opted groups need to be controlled with at least some repression. To put it differently, the dictator counterbalances positive endorsement with negative restrictions.

If the dictator decides to use mainly repression as an instrument to control the religious groups, it can be assumed that the dictator aims to prevent, control, and constrain the behavior of the religious groups at all fronts. When the dictator decides to use both co-optation and repression, however, he needs to strike a right balance between the two. For example, as part of the co-optation, the dictator may have granted the co-opted groups some negative rights, such as the right to gather in religious services. Consequently then, we would expect there to be qualitative differences in repression depending on whether the religious groups which are repressed are co-opted or not.

DESCRIPTIVE EVIDENCE: HOW DO THE COUNTRIES CLUSTER WHEN IT COMES TO REGULATION?

To describe the patterns of regulation in authoritarian countries, authoritarian countries are distinguished from the democratic ones by employing Polity-score of five or lower. According to this criterion, there were 73 non-democratic countries in 2014. Data on regulation of religion from the third round of the Religion and State project (RAS3) is employed for year 2014 or latest available data (variables with the suffix 2014X) (Fox Reference Fox2008; Reference Fox2011; Reference Fox2015; Reference Fox2018). The RAS3-dataset contains indicators for 1990–2014 for independent countries, which have a population of 250,000 or larger. As for positive endorsements, the dataset includes 52 binary-coded variables on government laws or policies, which legislate or support various aspects of religion. As for negative restrictions, the dataset contains 29 variables, which refer to the regulation on the majority religion or all religions. These variables are coded from 0 to 3 (0 = no restrictions; 1 = slight restrictions including practical restrictions or the government engages in this activity rarely and on a small scale; 2 = significant restrictions including practical restrictions or the government engages in this activity occasionally and on a moderate scale; 3 = the activity is illegal or the government engages in this activity often and on a large scale). For the purposes of the current study, the variables were classified into categories (see Table 1) following the conceptual framework presented above.

Table 1. Summary of the classification of the variables

Hierarchical cluster analysis was applied to explore the cross-country patterns in supportive policies and negative restrictions.Footnote 3 The purpose of cluster analysis is to distinguish between different groups of countries in the data in such a manner that (1) the countries in one group are as similar to each other as possible and (2) the different groups are as different from each other as possible. In the hierarchical clustering, the clusters are built from bottom-up (similar clusters are merged with each other at each step). To determine the mathematically optimal number of clusters, the R-package NbClust (Charrad et al. Reference Charrad, Ghazzali, Boiteau and Niknafs2014) was employed. According to the majority of the indices included in the package, the optimal number of clusters in the data is three. Thus, hierarchical cluster analysis (Ward's method, Euclidean distance) was conducted by enforcing three clusters as the solution. Finally, silhouette statistics were calculated to get information about the cohesion within and separation between the clusters (see the online Appendix for details regarding these results).

Three Worlds of Authoritarian Control of Religion

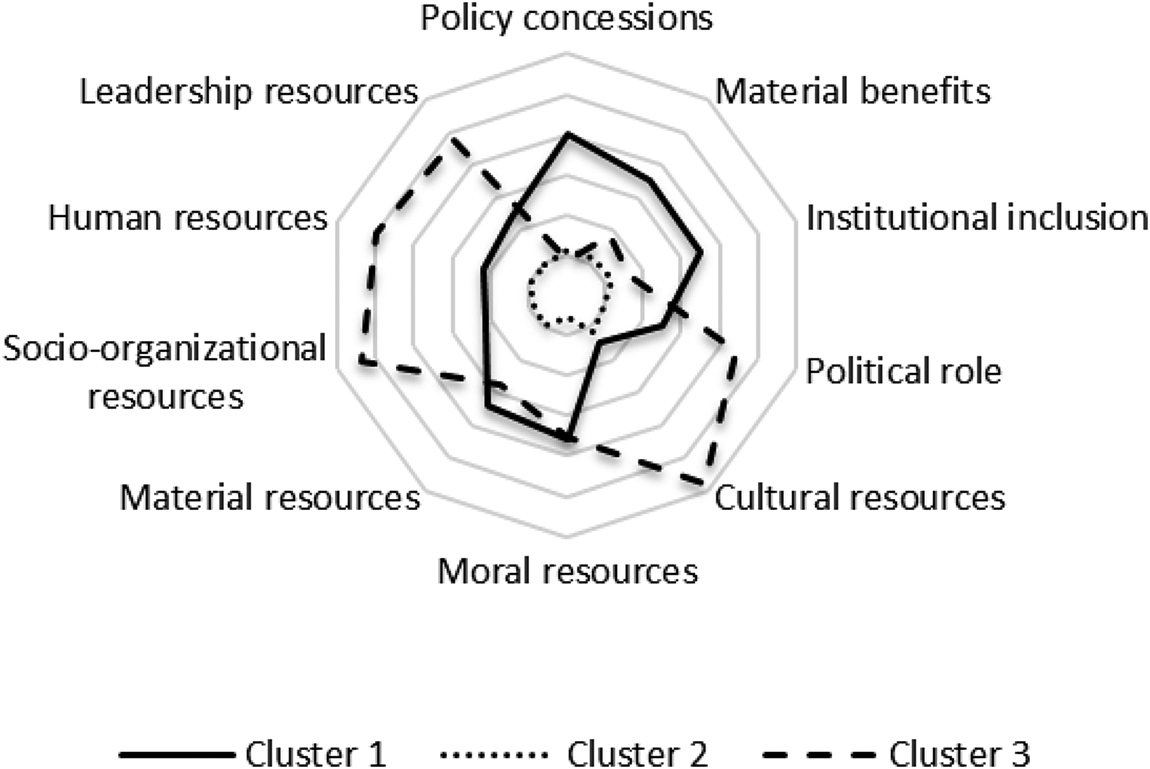

The dendrogram for the results of the hierarchical cluster analysis can be found in Figure 1. Figure 2 illustrates the qualitative similarities and differences in regulation across the clusters and Figure 3 shows the total level of both supportive policies and restrictive practices in each of the clusters. Together these results paint a picture of three worlds of authoritarian control of religion.

Figure 1. Results of the hierarchical cluster analysisFootnote 8

Figure 2. Cluster averages of different types of supportive and restrictive policies

Notes: Cluster characteristics refer to cluster averages of the z-standardized values. The higher the value, the further away from the center the cluster is.

Figure 3. Level of supportive policies and restrictions in 73 authoritarian countries

Notes: The sum of restrictions (26 variables) and supportive policies (49 variables) are employed and rescaled by dividing the original values with the theoretical maximum value (78 and 49 for restrictions and legislation, respectively), and by multiplying with 100. Thus, 100 represents the theoretical maximum value of the respective indicators.

The first cluster (“restrictive–supportive cluster”) consists largely of Muslim majority countries located in the MENA-region. Further, Bangladesh and Malaysia (both Muslim majority countries) as well as Belarus, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Russia (Christian majority countries) belong to this cluster. In these countries, the level of both supportive and restrictive policies toward religion is high, in most (but not all) cases at or above 20% of the maximum. Further, the level of restrictive policies appears to increase together with the level of supportive policies (r = 0.59). It is also of interest that the level of supportive policies is, in general, higher than the level of negative restrictions (with the exception of Belarus, Djibouti, and Eritrea, where the total level of restrictive policies is higher than the level of supportive policies). As for the quality of regulation, the average levels of support in the form of policy concessions, material benefits, and institutional inclusion are substantially higher in this cluster than in the other two clusters. Regarding the restrictive policies, the average levels are moderately high in all categories (with the exception of human and cultural resources), which further shows how support and restrictions go hand in hand.

The second cluster (“residual cluster”) consists of 38 countries, a majority of which is located in Sub-Saharan Africa. The common denominator for these countries is the low level of both supportive policies and negative restrictions (in general, at or below 20% of the theoretical maximum score). In Bhutan, Libya, Somalia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, however, the supportive policies are much higher (around 30% of the theoretical maximum or higher) than in the other countries in the cluster. Thus, these countries can be understood as borderline cases between the first and the second cluster.

The third cluster (“restrictive cluster”) consists of five post-Soviet Central Asian countries, four contemporary communist countries as well as of Myanmar, Syria, and Turkey. In these countries, the level of supportive policies toward religion is in general low (at or below 20% of the theoretical maximum), whereas the level of repressive policies is high (at or above 25% of the theoretical maximum). In Myanmar and Syria, however, the level of supportive policies is higher than in the other countries in the cluster. Regarding the patterns of supportive policies, particularly the level of policy concessions is low and thus, the supportive policies in this cluster consist mainly of material benefits and institutional inclusion. This may at first seem surprising, but it is important to keep in mind that financial support for religion often comes with conditions attached to it (cf. Fox Reference Fox2015, 85). Thus, funding of religion may be a convenient way even for the repressive countries to exercise control over the religious groups. As for institutional inclusion, all countries in this cluster with the exception of North Korea have an official government ministry or department, which deals with religious affairs. This shows that institutional inclusion can also be used for repressive purposes. Concerning the restrictive policies, in contrast to the supportive–restrictive cluster, the average levels are high for all types of policies. This shows that while countries both in the supportive–restrictive and restrictive clusters impose restrictions on religion, there are important qualitative differences in the type of applied restrictions.

DETERMINANTS OF CROSS-COUNTRY DIFFERENCES AND SIMILARITIES IN REGULATION

The above discussion suggests that there are three worlds of authoritarian control of religion, which differ from each other both when it comes to the quantity and quality of regulation. The discussion in this section draws from the research on authoritarianism to make some preliminary suggestions as to why the countries cluster into three groups. Further, quantitative techniques are employed to explore how the factors identified as consequential for the regulation of religion are related to regulation.

Capacity and Ambition of the Religious Groups

The dictator's decision to co-opt or repress the different groups in the civil society is assumed to partially depend on the characteristics of these groups. For example, Schmotz (Reference Schmotz2015) argues that co-optation can be understood as a means for the regime to compensate for its vulnerability toward the different pressure groups. He further argues that regime vulnerability in this respect can be determined by studying the capacity of the different groups to engage in a political protest, as well as by examining the ambition/willingness of these groups to challenge the regime. Similarly, in the research on repression, it is assumed that the dictator relies on repression to control threatening behavior and dissident (for discussion, see Davenport Reference Davenport2004, 541–45; Davenport Reference Davenport2007b, 7–10). Following this line of reasoning, it can be assumed that countries where both the capacity and ambition of the religious groups to engage in a protest are high, the government will compensate for its vulnerability toward the religious groups by co-opting or/and repressing the different groups.

It is here argued that the capacity of a religious group can be understood as the sum of the collective action resources it has at its disposal. The ambition of the religious groups to get engaged in politics can be demonstrated in a large variety of actions, such as content of sermons, protests by religious groups, statements by religious leaders, establishment of religious parties, and religious terrorism. Interestingly, even though religious groups would have enough capacity, they may not always want to get involved in politics. For example, engagement in political issues may divide the congregation, and consequently weaken the group and distract it from its main purpose. In addition, political engagement may lead to repression of the congregants and religious leaders (for discussion, see Fox Reference Fox2013, 89ff). Further, depending on the political theology (Philpott Reference Philpott2007) of the group in question, engagement in politics, and consequently a confrontation or co-operation with the regime may or may not be desirable.

Cross-country differences in the capacity and ambition of the religious groups may at least partially explain the cross-country differences in the extent of the regulation of religion. Such differences, however, cannot explain why some countries treat religious groups in a restrictive manner, whereas others use a mix of both supportive and restrictive policies. Indeed, in addition to the capacity and ambition of the religious groups, we need to study the capacity and ambition of the regime to understand the clustering of the countries.

Capacity of the Regime

Buckley and Mantilla (Reference Buckley and Mantilla2013) provide an extensive discussion about the relationship between state capacity and regulation of religion. In particular, they suggest that economic advances increase the state capacity (i.e., the ability of the state to formulate and implement policy) to regulate religion. On the one hand, increases in state capacity strengthen the state institutions, and encourage the state to expand its activities to new areas, such as the religious sphere. For example, the government may take over the control of education from the religious organizations. On the other hand, due to the expansion of government activities, the religious actors are pulled into the political debates and push through their own agenda. As a consequence, the government needs to develop its regulatory framework to distinguish between the division of labor between the state and the religious sphere.

The argument by Buckley and Mantilla (Reference Buckley and Mantilla2013) may provide a partial explanation to the low levels of both restrictive and supportive policies in the residual cluster. Further, regarding countries in the restrictive–supportive cluster, the religious actors often, due to co-optation, have responsibility over institutions such as education and marriage, and it is also in these countries that the religious actors are integrated into the political debates. As a consequence, regulation can indeed be understood as the regime's attempt to distinguish between the responsibilities of the state and the religious actors, and the regime's need to keep the religious actors under control. Consequently, we can expect the level of regulation to be positively related to the economic wealth in these countries.

In the restrictive cluster, however, regulation cannot be seen as an attempt to determine the division of labor between the government and the religious actors, but more as an attempt to keep religious groups under control by giving them very limited room to breathe. Indeed, in the repressive countries, the religious actors are not integrated into the political debates, but are rather isolated from these debates as efficiently as possible. Thus, even though it still can be argued that wealthier repressive countries have higher levels of regulation due to resource availability, the other parts of the argument by Buckley and Mantilla are more difficult to reconcile with the logic of the repressive control of religion.

Ambition of the Regime

As for the ambition of the regime, it is helpful to rely on the research on legitimation. According to Gerschewski (Reference Gerschewski2018, 655), “Legitimacy is a relational concept between the ruler and the ruled in which the ruled sees the entitlement claims of the ruler as being justified, and follows them based on a perceived obligation to obey.” Against this background, it is possible to understand legitimation as “the process of gaining legitimacy” (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2018, 655). In general, the dictator's claims to legitimacy are important, as they enhance elite cohesion, set the limits within which opposition can voice their concerns, make it possible for the regime to uphold their power even in times of crisis, and influence the tools which the regime uses to stay in power (for discussion, see von Soest and Grauvogel Reference Von Soest and Grauvogel2017).

The argument put forward here is that the ideological legitimacy claims of the regime have an impact on which groups in the civil society are defined as, on the one hand, suitable allies and, on the other hand, as foes of the regime.Footnote 4 It can be postulated that when the ideological justification of the regime is tied to religion, the regime sees religious groups as convenient allies and pursues a restrictive–supportive strategy toward the religious groups. One of the benefits of co-opting the religious groups is that these groups can support the regime in its legitimation strategies and thus give credibility for the regime. Further, religious groups may be preferred as allies in comparison to groups, which undermine the religious credentials or legitimation strategies of the ruler (e.g., parties, which promote secular nationalism or communism).

When the legitimacy claims of the regime are related to ideologies, which are unfriendly or even hostile toward religion (most notably, communism, for a review, see Pfaff Reference Pfaff and McCleary2011; Madsen Reference Madsen and Smith2014), the regime is likely to perceive religious groups rather as opponents than allies. Indeed, the regime is not likely to co-operate with religious groups, but rather takes a restrictive stance toward them. Moreover, the religious groups are not likely to support regimes, which in their ideological legitimacy claims declare a negative stance toward religion and religious groups. In conclusion, the regime is likely to pursue a restrictive strategy toward religion.

Empirical Investigations

The above discussion highlights the importance of capacity and ambition. It is, however, important to emphasize that the specific patterns of regulation of religion have evolved over time as a combination of different factors. While for some countries the patterns of regulation have formed relatively recently (e.g., post-Soviet countries), in many cases one would need to go back for several decades (e.g., Iran) or even centuries (e.g., Saudi Arabia) to understand the regulatory regime. Further, it is clear that the capacity and ambition of the different groups are influenced by the actual policies of the regime. Indeed, the very idea of restrictive policies is to lower the capacity and ambition of religious groups, whereas the supportive policies will increase the capacity of the religious groups. Is it not possible here, within the scope of the paper, to make use of extensive quantitative or qualitative studies to explore the interaction between the different factors. Rather, the purpose of the cross-sectional investigations presented below is to provide a first description of the correlation between the regulatory regimes and the factors which above were suggested to be of importance for the regulatory practices.

Data

The capacity of the religious groups is operationalized as the share of the population affiliated with the largest religious group in 2010 (Pew 2015). The ambition of the religious groups is measured with data from the International Religious Freedom Data 2008 (Harris, Martin, and Finke Reference Harris, Martin and Finke2019). This dataset is based on ARDA's coding of the 2008 U.S. State Department's International Religious Freedom Reports. The variable which is employed in the current study is a 0–10 scale response to the question “According to the Report, to what extent do the society's religious groups, associations, or culture at large restrict the practice, profession, or selection of religion?”

It is clear that these operationalizations are not optimal. Yes, it is difficult to find data, which would accurately capture the theoretical construct. For example, regarding the capacity, we would need to have data on the different collective action resources of the religious actors. This would include, but would not be limited to, factors such as number of clergy, number of places of worship, number of members, economic resources, co-operation with foreign actors, leadership resources, strategical repertoire, and legitimacy in the eyes of the population. It is impossible to find reliable data on these aspects for one authoritarian country, let alone for several ones. Thus, due to the lack of better alternatives, the decision was made to employ indicators, which have good availability.

Regarding the capacity of the regime, data on GDP/capita for 2014 is employed (World Bank 2019). As for the ambition of the regime, data on legitimation comes from V-Dem (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Steven Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Wilson, Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Ilchenko, Krusell, Maxwell, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Pernes, Johannes von Römer, Stepanova, Sundstr¨om, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2018; Tannenberg et al. Reference Tannenberg, Bernhard, Gerschewski, Lührmann and von Soest2019). This data is based on a survey, where country experts were asked questions about the regime legitimation strategies. Regarding the ideological legitimation strategies, the country experts were at first asked to estimate to what extent the government promotes a specific ideology or societal model to justify their regime. Thereafter, the country experts were asked to characterize the ideology/ideologies, which were employed by the regime. Five ideologies were given as response options (nationalist; socialist or communist; restorative or conservative; separatist or autonomist; religious). The responses of the experts were aggregated to give one estimate for each country and ideology. The two categories of religious and socialist or communist ideologies should most accurately capture those authoritarian regimes, which have a favorable or hostile ambition toward religion and they were consequently included in the empirical investigations.

Four countries are excluded from the below empirical investigations due to missing data, namely South Sudan (no data on ambition of the religious groups) and North Korea, Syria, Somalia (no data on GDP/capita).

Discriminant Analysis

The comparison of the mean values of the three clusters (Table 2) shows that the three clusters do not substantially or statistically significantly differ regarding the average size of the largest religious group. The average level of ambition is highest in the restrictive–supportive cluster and at relatively high levels also in the restrictive cluster. This gives some support to the idea that the ambition of the religious groups is of importance when it comes to understanding the cross-country similarities and differences in regulation. Regarding the capacity and ambition of the regime, the mean of GDP/capita is not substantially or statistically significantly different in the three clusters. In accordance with the theoretical considerations, the average level of religious legitimacy claims is highest in the restrictive–supportive cluster and lowest in the restrictive cluster. Conversely, the mean of the socialist or communist legitimacy claims is highest in the restrictive cluster and lowest in the restrictive–supportive cluster. Even though the differences between the groups are not statistically significant for all variables, all variables are included in the discriminant analysis due to the theoretically strong reasons to suspect that these variables are of importance.

Table 2. Mean values and standard deviations of the variables in each of the three clusters

Notes: Standard deviations are in parentheses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Predictive discriminant analysis is employed to study how well the knowledge about the capacity and ambition of the regime and religious groups helps us to predict the cluster membership of the countries. Table 3 shows the actual group of the countries (i.e., results from the cluster analysis) as well as the group membership, which is predicted by the discriminant analysis based on the five variables on capacity and ambition.Footnote 5 As can be read from the table, 63.8% of the countries are correctly classified based on the knowledge about the capacity and ambition of the religious groups and the regimes. The hit rates are best for the restrictive–supportive cluster (73.9% of the countries correctly classified) and the residual cluster (61.1% of the countries correctly classified). The hit rate for the restrictive cluster, however, is only 50.0%. While it is clear that the knowledge about the four variables does not fully help us to predict the cluster membership of the countries, the results are encouraging in that they give some support to the idea that the four variables are important. This, in turn, supports the idea that the study of how the countries cluster in terms of regulation of religion is a promising avenue for future research.

Table 3. Actual and predicted groups

Notes: Numbers in parentheses refer to hit rates.

OLS-regression

Table 4 shows the results from OLS-regressions, where the association between the supportive policies (output variable) and the five variables on capacity and ambition (input variables) is studied. A comparison of the adjusted R 2 shows that model 1, which includes only the two variables on religious groups, performs poorly in comparison to model 2, which includes information only on the regime. In model 3, all five input variables are included. In accordance with the theoretical discussion, all variables with the exception of socialist or communist regime ideology are positively associated with supportive policies (the results for the largest religious group are not statistically significant). The conclusion from the exercise is that future research on the determinants of supportive policies in authoritarian countries should focus more on variables, which are related to the capacity and ambition of the regime.

Table 4. OLS-regression with total level of supportive policies as the outcome variable

Notes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The results from the regressions with the total level of restrictive policies as the outcome variable (Table 5) are less straightforward. While all five input variables are positively related with restrictive policies (the results are statistically significant only for GDP/capita and the ambition of the religious groups), the adjusted R 2 of the models is very low. This further gives some support to the idea that supportive and restrictive policies need to be studied jointly in order to understand the logic of authoritarian control of religion.

Table 5. OLS-regression with total level of restrictive policies as the outcome variable

Notes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The simultaneous study of positive endorsement and negative restrictions on religion and the distinction between clusters of authoritarian regimes appears helpful in order to understand the authoritarian regulation of religion. Yet, more theoretical and empirical work is required in this respect. For example, it is not clear if minority religion regulation and social regulation of religion should be taken into consideration when the countries are clustered. Further, the theoretical discussion regarding the determinants of regulation is both preliminary and static (i.e., there is no discussion on how the variables are related to each other over time). More discussion (and accordingly, empirical studies) is needed regarding the dynamic interaction between the different factors over time.

In addition, particularly four areas require more attention in the future. Firstly, more work needs to be done to understand if and how religion is related to the different legitimacy strategies employed by the authoritarian regimes; why such ties between religion and legitimation developed in the first place and how the legitimacy claims influence regulation of religion. For example, many countries in the restrictive–supportive cluster are monarchies, where the legitimacy claims are tied to tradition and/or God-given right to rule (for discussion, see Schlumberger Reference Schlumberger2010; Kailitz Reference Kailitz2013). Further, in many countries in the restrictive–supportive cluster (e.g., Russia, Malaysia), religion is unified with nationalistic legitimacy claims (for discussion about the ties between nationalism and religion, see Brubaker Reference Brubaker2012; Soper and Fetzer Reference Soper and Fetzer2018). The restrictive cluster, in turn, consists largely of communist countries; formerly communist Central Asian countries and countries such as Syria and Turkey, where the ideological legitimacy claims of the regime are related to secular nationalism.Footnote 6 These differences in authoritarian legitimacy claims, as well as their origins and consequences for the interaction between the regime and the religious groups should be carefully studied. Finally, it would be important to understand how vital religion is vis-à-vis the other types of legitimacy claims such as performance and procedures.

Secondly, it must be explored if the link between legitimacy claims and positive endorsement of religion really is due to co-optation.Footnote 7 An alternative explanation is that authoritarian regimes positively endorse religion in order to appeal to the religious population and in that way gain legitimacy. It is further possible that some dictators aim to appeal to the population, whereas others target the religious groups and elites, or that a regime introduces supportive policies toward religion to both co-opt the religious groups and to appeal to the population.

Thirdly, the consequences of economic crisis for regulation of religion need to be theorized and studied in detail. Indeed, economic crisis influences the capacity of the regime, and thus also the strategical calculations of the regime and the oppositional groups (for discussion, see e.g., Conrad Reference Conrad2011). Further, economic crisis may contribute to a legitimacy crisis of the regime, which in turn may lead the regime to (increasingly) rely on religious groups for legitimacy. At the same time, when the regime is confronted with an ideological crisis, this may increase the moral authority of religious actors and thus their capacity.

Fourthly, it is important to study how supportive policies and negative restrictions influence the capacity and ambition of the religious groups and thus, in turn, the dictator's decisions about regulation. Such discussion is particularly important in order to understand, for example, why a change in the authoritarian regime type sometimes leaves the treatment of religious groups almost unchanged.

Regarding the methodology, qualitative studies which research a long time span are the only way to fully appreciate the complex interactions between the different religious groups and the regime, particularly as the capacity and ambition of the various religious groups is difficult to capture at macro-level. Yet, a broad comparative framework of the different types of state–religion interactions, such as the one presented above, should be helpful in order to contextualize such case studies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048320000383.