In popular music historiography, Abbey Road Studios is depicted as a beacon of sound recording excellence, an ‘ivory tower’ workplace evoking ‘golden age’ popular music sound recording. Alan Williams (Reference Williams2010) recognised the ‘canonization of (recording) process’ in the Classic Albums documentary series. Indeed, this recognition of established ‘classic rock’ recording techniques is further reinforced in wider academic discourse, particularly in significant works by Cunningham (Reference Cunningham1998), Zak (Reference Zak2001) and Burgess (Reference Burgess2005). In recent years, as phonomusicological study has shifted towards the examination of recording and production processes, so too has formed a ‘recording studio canon’, further reinforced by 2013 film documentaries Sound City Footnote 1 and Muscle Shoals. Footnote 2 Studies by Théberge (Reference Théberge2004), Leyshon (Reference Leyshon2009), Bates (Reference Bates2012), Bennett (Reference Bennett2010, Reference Bennett2012a) and Schmidt Horning (Reference Schmidt Horning2013) exemplify the recording workplace as a significant contributing factor to music production. Central to this ‘studio canon’ is Abbey Road, alongside US recording workplaces such as Sun Studios in Memphis, Tenessee, Goldstar and Sound City Studios in Los Angeles and Hitsville USA, Detroit. Abbey Road Studios, its history, artist associations and recording personnel, feature heavily in rock music and sound recording discourse, particularly in Mark Cunningham's Good Vibrations (Reference Cunningham1998, p. 137), Greg Milner's Perfecting Sound Forever (Reference Milner2009, p. 157) and Virgil Moorefield's The Producer as Composer (Reference Moorefield2005, pp. 28–9). The fascination with Abbey Road Studios is also reflected in ongoing newspaper and music journalism, television programmes, radio broadcasts and, in recent years, a gradual increase in public accessibility via public lectures and open days, as well as the 2015 announcement of an ‘Abbey Road Institute’ education programme.

In addition to ongoing cultural commentary, scholarly discourse surrounding Abbey Road has become more intricate, meticulously researched and revealing. The appetite for ‘behind the scenes’ details – no matter how small – has grown in recent years. This is, however, unsurprising and largely indicative of public curiosity surrounding Abbey Road Studios. After all, this is the site of the creation of some of popular music's most critically acclaimed and canonised works; the studio hosted recording sessions of many multi-platinum selling British popular music artists, including Cliff Richard and The Shadows, The Beatles, The Hollies, Pink Floyd and Kate Bush. Thus the interest in music recorded at Abbey Road Studios can be attributed to genuine, musical appreciation and the acknowledgement of the recording studio as part of the music creation process. It is not, therefore, the intention of this article to reduce or interpret matters of straightforward appreciation and curiosity as evidence of heritage or ‘aura branding’. Instead, this article illustrates how Abbey Road has changed from a recording house into a marketable brand to ensure its future sustainability.

Weighing in at almost 5 kilos as a hardcover volume, Brian Kehew and Kevin Ryan's exhaustive study, Recording the Beatles (Reference Kehew and Ryan2006), is a methodically researched and comprehensive account of 1960s Abbey Road studio technology. The inner workings of each control aboard the REDD console, every microphone specification and the precise technical construction of each tape recorder are thoroughly discussed and illustrated. Alistair Lawrence's Abbey Road: The Best Studio in the World (Reference Lawrence2012) is another example of an over-sized text featuring a detailed photographic history of ‘never seen before’ images. Such studies have further reinforced Abbey Road as the rock canon's ultimate recording house, an iconic workplace where hit records were made by maverick recordists and chart-topping artists.

Abbey Road Studios’ evolutionary trajectory is well documented in extensive works by Southall et al. (Reference Southall, Vince and Rouse1982), Cunningham (Reference Cunningham1998) and Milner (Reference Milner2009). One of the first dedicated recording houses in the world, EMI built the studio in 1931. Renowned for Elgar's early classical recordings in the 1930s, through to 1960s and 1970s ‘classic album’ output, in the 1980s, the studios refocused on film score recording, post production and mastering. Yet Abbey Road Studios’ relationship with its single most cited artist, The Beatles, is a simultaneously beneficial and problematic aspect of its history. Academic discourse, cultural commentators and biographical accounts from former employees rarely mention the studios without using The Beatles and their music as a contextual framework. The Beatles function as important artistic corroborators to the legacy of Abbey Road Studios and, therefore, the two are intrinsically linked, not least owing to the Beatles’ 1969 Abbey Road album. Abbey Road Studios benefit from this association: the building is part shrine, part tourist attraction and part heritage site for those interested in The Beatles and general popular music history. Yet for all the attention on its legacy, problems surrounding the Studios’ business operations became public in 2007, following the acquisition of EMI by private equity firm Terra Firma (Leeds Reference Leeds2007). As Andrew Leyshon (Reference Leyshon2014, p. 140) pointed out, the takeover ‘cast doubt on the survival’ of both EMI and, particularly, Abbey Road Studios. A public outcry, involving petitions, media campaigns and intervention by the UK's National Trust, ensued in 2010, when Terra Firma considered selling the recording house (Fenton Reference Fenton2010; Leyshon Reference Leyshon2014). Accounts of Abbey Road's business operations post-2010 raise questions: what exactly is Abbey Road Studios today? How does Abbey Road Studios survive in a declining recording industry climate? This article addresses these issues directly, with special focus on heritage, branding and aura.

This study is particularly relevant in the broader discourse on the decline of the recording studio (Leyshon Reference Leyshon2009; Pras et al. Reference Pras, Guastavino and Lavoie2013; Watson Reference Watson2015). In the last 20 years, the UK – and London in particular – has lost some its most renowned studios, including Sarm, Olympic and Townhouse. In The Software Slump, Leyshon directly correlates the decline of professional British recording studios with the rise of the consumption of digital music. One of the issues with professional recording studios is that they operate in a market characterised by ‘oligopsony; that is, a market characterized by few buyers’ (Leyshon Reference Leyshon2014, p. 13). Leyshon also recognised the operation of recording studios in the post-production market and how this has become a lucrative area of business, work such as synchronisation and mastering that takes place on already-recorded works. Leyshon also noted that, while the recording studio sector was in decline, ‘vanity project’ studios were prevalent – recording houses owned by high-profile musicians, such as British Grove Studios in London (owned by Mark Knopfler of Dire Straits) and Real World Studios in Bath (owned by Peter Gabriel).

Yet despite the decline of the elite recording sector, Abbey Road Studios has survived and this is due to a number of key factors: firstly, the studio ventured into post-production and soundtrack work long before many of its contemporaries, thus maximising its place in both sound recording and post-production markets; secondly, the studio is housed in a Grade II listed building, making any potential buyout and refurbishment problematic; and, thirdly – and perhaps most importantly – the studio's historical significance and unique aura have ensured its sustainability.

Over time, ‘Abbey Road’ has come to mean a number of things; indeed, this blurry conflation of Beatles album, location, recording house and surrounding area reinforces a type of studio ‘mythology’. The Oxford English Dictionary defines mythology as ‘A set of stories or beliefs about a particular person, institution, or situation, especially when exaggerated or fictitious’. The ‘set of stories’ surrounding Abbey Road Studios, when considered in the context of its geographical location and place in popular music historiography, has elevated the recording house to mythological status, an elite, legendary venue, symbolising a ‘golden age’ of British record production.

Abbey Road is first and foremost a location, the B507 road linking St John's Wood and West Hampstead in north London, NW8. At number 3 stands the recording studio, a detached Georgian house, purchased in 1929 by The Gramophone Company. The studio is situated just along from a mini junction, on a left-hand fork from Grove End Road; a zebra crossing just outside and to the right of the studio building links each side of Abbey Road at this busy, forked intersection. The studio is set back from the road, fronted by a brick wall painted white and (on an average day) covered in graffiti. Abbey Road is also the title of the Beatles’ penultimate studio album: the title a homage to the recording studio where the album was made; the artwork an iconic – and oft parodied – photograph of the band striding single file across the nearby zebra crossing. So, ‘Abbey Road’ as a name evokes not just the recording studios but also the immediate north London locality, a well-known band and their most commercially successful recording. These aspects are wholly tangible: a road, a zebra crossing, a brick wall and a sound recording artefact are identifiable, accessible and ‘known’ components in Abbey Road's history. However, Abbey Road Studios, the building itself, is not – and never has been – open to the public. It is not a museum, nor does it host regular public events. Less understood and ‘known’, therefore, are the goings on inside the building: the inner acoustical construction of the studio rooms, the technologies, the recordists and their day-to-day working practices, the business and financial workings of the studio, management operations, the musicians and recording sessions. These ‘intangibles’ have formed a historical sense of magic and mystique surrounding Abbey Road Studios; a ‘Wonka factory’ style mythology has – until very recently – surrounded the inner workings of the recording house. ‘Insider’ views have been pieced together over the years by Abbey Road's recordists and various musicians who recorded there. However, in recent times, steady revelations in the form of increased public events, broadcasts, the aforementioned Beatles books and merchandise have conflated into a wholly viable and marketable Abbey Road brand. By ‘brand’, I mean that Abbey Road has a strong identity, an image crafted over more than 80 years of elite sound recording. The packaging of this identity into a commodity has, in recent times, ensured that the studio is more marketable, accessible and sustainable.

Indeed the marketing of these once-concealed elements has resulted in a demythologisation of Abbey Road Studios, as ‘insider’ revelations slowly reveal the technology, recording processes and experiential accounts once hidden from public view.

This article forms part of a wider study into matters of technological and processual potential upon the sound of popular music recordings. In terms of first-hand experience of the studios, I visited four times between 1998 and 2013; three of those occasions were to attend public events and one was to drop in on a friend's drum recording session. I worked alongside some of Abbey Road's former recordists as part of the JAMES educational working group in the UK. I also draw from my experience between 2003 and 2008, when I would catch the 139 bus from my home in West Hampstead to work in Paddington almost every day. I recall the regular frustrations of 139 travellers, whose journey was often delayed at the zebra crossing outside Abbey Road Studios as they waited for tourists to finish taking their zebra crossing photographs. Having interviewed former recordists of Abbey Road Studios for my forthcoming book (Bennett Reference Bennett2016), I became interested in their oral histories, particularly when considered alongside other, published biographical accounts from Abbey Road studio recordists. After carrying out much analytical work on recording studio discourse, I noticed patterns of mythology in the semantics of journalism and popular cultural commentary. So, a critical ethnographic methodology (Soyini Madison Reference Soyini Madison2012) was employed, drawing upon interview material with Abbey Road recordists and cross-referencing accounts with those from published biographical works, and then situating the findings in a broader contextual framework. Furthermore, iterative analysis of journalism features on Abbey Road Studios was conducted, as well as focus upon wider cultural and ethnographic academic studies.

Abbey Road discourse

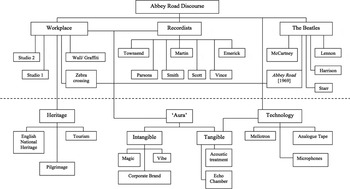

How do existing studies relating to Abbey Road Studios exemplify issues of heritage and aura, if at all? Existing texts on Abbey Road Studios often fall into one or more of three distinct categories: studies on the Beatles as a group, as individuals and as musicians; autobiographical accounts written by Abbey Road recordists; and texts pertaining specifically to Abbey Road as workplace. Figure 1 denotes Abbey Road discourse as it stands. Key works, particularly Southall et al.'s Abbey Road (Reference Southall, Vince and Rouse1982), Lewisohn and McCartney's The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions (Reference Lewisohn and McCartney2012) and aforementioned books by Lawrence (Reference Lawrence2012) and Kehew and Ryan (Reference Kehew and Ryan2006), cover Abbey Road as workplace in varying degrees of detail. These texts offer readers a ‘behind the scenes’ view into the workings of Abbey Road Studios, particularly at the height of the Beatles’ recording sessions. All of these studies are retrospective historical accounts highlighting only the most commercially successful sound recordings to have been captured at Abbey Road. Arguably, the culmination of such minutiae ensures that little, if anything, is left to say on the Beatles’ time recording at Abbey Road. However, the documents are retrospective and are, therefore, inevitably selective. For example, Lawrence's book depicts musicians and recordists at work, happy and content. Any strained, difficult sessions, relationships or technical hitches are excluded. The result, therefore, is a nostalgic, unrealistic portrayal of the so-called ‘best studio in the world’. Biographical accounts written by former Abbey Road recordists include George Martin's All You Need is Ears (Reference Martin and Hornsby1979), Geoff Emerick's Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Beatles (Reference Emerick2007), Norman Smith's John Lennon Called Me Normal (Reference Smith2007) and Ken Scott and B. Owsinski's Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust: Off the Record with the Beatles, Bowie, Elton & So Much More (Reference Scott and Owsinski2012). Herein lies the inextricable nature of Abbey Road Studios as workplace, its recordists and the Beatles: every recordist biography title refers to the Beatles or Abbey Road in some way or another.Footnote 3 The recordists position their life stories in an associative context; their relevance is validated by the famous recording studios and the most significant band to have recorded there. In other words, the recordists do not stand alone; their achievements only become relevant when situated in the larger context of Abbey Road Studios and the Beatles legacy. Even sound recording articles, such as Buskin's ‘Norman Smith: the Beatles’ first engineer’ (Reference Buskin2008), fail to mention the recordist without the association of the Beatles. An exception to this pattern is Alan Parsons and J. Colbeck's Alan Parsons’ Art and Science of Sound Recording (Reference Parsons and Colbeck2014). At 19 years old, Parsons was much younger than many of the Beatles-era Abbey Road recordists when he gained an assistant engineering credit on the Beatles’ Abbey Road. Parsons is also well known for engineering Pink Floyd's 1974 album Dark Side of the Moon and therefore, the Beatles’ legacy does not dominate Parsons’ career in the way it does those of Martin, Scott, Smith and Emerick. Beatles texts, such as those by Everett (Reference Everett1999), Womack (Reference Womack2009) and Gaar (Reference Gaar2013) again note the inextricable nature of the Beatles and Abbey Road Studios. The Abbey Road sound recording process, the ‘zebra crossing’ album photograph and the legacy of the album as a ‘masterpiece’ (DeVille Reference DeVille2013), ‘masterfully coherent’ (Chester Reference Chester2012) and ‘their finest hour’ (Gerard Reference Gerard2014) conflate to reinforce the association.

Figure 1. Existing Abbey Road discourse: recordists, workplace and The Beatles are three key foci. Less focus on heritage, technology and aura.

Scholars such as Zolten (Reference Zolten and Womack2009, p. 56) and Gaar (Reference Gaar2013, p. 18) as well as Inglis (Reference Inglis2001) recognised the mythologisation of the Abbey Road album cover, particularly in the appearance of Paul McCartney, who was rumoured to have died before the album's release. McCartney strides ‘out of step’ to the other Beatles, appears barefoot and holds a cigarette in his right hand; these ‘inconsistencies’ gave conspiracy theorists of the era reason to believe McCartney had died and had been replaced by an imposter. Indeed Abbey Road, to include the recording process, the song structures, lyrics and musicality, the album cover and wider meaning, have engaged scholars, Beatles fans and popular culture commentators for decades. As Figure 1 shows, studies pertaining to Abbey Road sound recording technology, issues of heritage and studio aura are less common, and hence appear under the dashed line.

This article seeks to contribute to this understudied area in the following ways: to consider notions of heritage, pilgrimage and tourism in relation to Abbey Road Studios; to elucidate the aura of Abbey Road Studios; and to demonstrate the studio aura as viable commodity.Footnote 4 The aforementioned biographical, historical and journalistic accounts therefore form the bulk of material, although the studios have recently become a point of focus in academic work. Brabazon (Reference Brabazon2002) and Roberts and Cohen (Reference Roberts and Cohen2013) have acknowledged Abbey Road Studios as a heritage site. Brabazon (Reference Brabazon2002) focussed wholly on the ‘graffiti wall’, analysing the messages left by fans, the wall as ‘canvas’ and implications on cultural memory. The study illuminates Abbey Road as global heritage site, recognising fan inscriptions from Holland to New Zealand. Additionally, Brabazon notes the problematic nature of ‘repainting’ the wall to accommodate the constant stream of visitors and their messages. Fans are only too aware that the wall is regularly whitewashed and some express their frustration on the wall in addition to leaving messages. In a wider study on popular music heritage sites, Roberts and Cohen (Reference Roberts and Cohen2013) cite the Abbey Road zebra crossing as an example of cultural heritage, asserting that the crossing is not in the original location (this will be discussed later on) and, quite rightly, question its Grade II listed status above other popular music-referenced landmarks. Roberts and Cohen also acknowledge the ‘Blue Plaque’ scheme operated by English Heritage to mark sites of important cultural significance. Interestingly, and not acknowledged in their study, the plaque on Abbey Road Studios is a smaller, green ‘Open Plaque’ that recognises Sir Edward Elgar as the first composer to have recorded in the studios. Ironically, the plaque was not awarded by English Heritage and is the only non-Beatles-related aspect of the entire building.

In his 2012 paper, ‘What studios do’, Eliot Bates conducts significant ethnographic work into the role of the studio. Prior studies by Kealy (Reference Kealy1982), Hennion (Reference Hennion1989) and Théberge (Reference Théberge2004) have described the studios as laboratory-like or ‘assembly line’ in nature, but Bates argues that:

Studios are unique. They have a sound, a vibe and even, in the case of legendary studios such as Abbey Road that become vacation destinations or pilgrimage sites, a transformative effect even on those who never professionally use the studios. (Bates Reference Bates2012)

Bates goes on to examine the architectural and acoustic properties of studios, along with the deliberate audio and visual constraints built within them, in a vital study that makes a particularly informative contribution to the field of recording studio ethnography. Like Brabazon, and Roberts and Cohen, Bates goes on to acknowledge Abbey Road Studios as pilgrimage site. Such studies have considerably expanded the evidence base of historical and biographical accounts, introducing less acknowledged issues of heritage and technology into the discussion. The three aforementioned categorical foci depicted in the top half of Figure 1 form the majority of existing work, but this investigation seeks to reinforce Bates, Roberts and Cohen and Leyshon's work, as well as introduce some thoughts on aura and matters of technological potential, which I will come to in due course.

Cultural heritage

At this point, we know that Abbey Road Studios is positioned firmly in the recording studio canon, its artists and recordists situated prominently in popular music historiography. So in what ways is the studio considered as cultural heritage? The Oxford English Dictionary defines heritage as being ‘Valued objects and qualities such as historic buildings and cultural traditions that have been passed down from previous generations’. This definition splits heritage into two distinct categories: that of objects and buildings and that of cultural tradition. It does, therefore, make sense to consider issues of heritage in the context of the tangible (objects and buildings) and intangible (tradition) and that is precisely what this article intends to elucidate when considering Abbey Road. The position of Abbey Road Studios as cultural heritage was not fully realised until 2010, when EMI announced that it was planning to sell the studios, as Salamander Davoudi recalled:

The extreme national sensitivity around EMI's heritage was highlighted when the FT reported that the company was looking to sell Abbey Road, the recording studios made famous by The Beatles. ‘The world went berserk. From Japan to New Zealand, there was hysteria,’ said one former EMI employee. The National Trust looked into buying it, so did music mogul Andrew Lloyd Webber and the UK government promptly listed the building. (Davoudi Reference Davoudi2011)

Davoudi refers to the outcry surrounding the sale of the building, a tangible aspect of Abbey Road, but is Abbey Road's heritage attributable to the building alone? In 2003, UNESCO published a convention on safeguarding intangible cultural heritage, describing it thus:

The ‘intangible cultural heritage’ means the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. (UNESCO 2003)

The UNESCO convention, while not signed up to by the UK, directly refers to the preservation of cultural spaces and recognition of traditional practices occurring within those spaces. This further assists in considering the tangible and intangible: Abbey Road as a building, the surrounding brick wall and zebra crossing can be considered tangible; the practice of walking across the zebra crossing, the internal ‘atmosphere’ of the studio can be considered intangible.

Indeed the elevation of Abbey Road Studios above its UK – and global – counterparts can be attributed to a single photograph taken in 1969; the Beatles’ Abbey Road album cover, depicting the four Beatles striding across the Grove End Road/Abbey Road zebra crossing, now epitomises Abbey Road mythology. Following the public outcry at the sale of Abbey Road, English Heritage listed the Abbey Road zebra crossing in 2010Footnote 5 (the only road marking in England to have been awarded such status), justifying their decision on Beatles history and a ‘celebration of this important form of road safety crossing, as invented by Lord Hore-Belisha’ (2010). In their 2013 paper, ‘Unauthorising popular music heritage’, Roberts and Cohen discuss the Abbey Road crossing:

Functioning as a form of what Dean MacCannell has termed ‘staged authenticity’ (1976), and as a pilgrimage site (the hallowed ground upon which the Fab Four once trod), its cultural heritage status is, therefore, as much attached to the idea the crossing represents as an intangible cultural icon (an image from an album cover) as it is to an actual ‘authentic’ site, the materiality of which is conserved and protected for posterity. (Roberts and Cohen Reference Roberts and Cohen2013, p. 5)

This suggests that Abbey Road Studios and the adjacent zebra crossing are not, in themselves, sites worth listing at all; they are only of cultural significance owing to the association with a much larger cultural entity. English Heritage's acknowledgement of Lord Hore-Belisha's invention of the zebra crossing is, therefore, an adjunct afterthought to its main justification. Roberts and Cohen quite rightly go on to question the preferential treatment given by English Heritage towards sites associated with the Beatles and not to others, including Waterloo Bridge (inspiration behind The Kinks’ Ray Davies’ ‘Waterloo Sunset’) and Punk venues, such as the 100 Club (venue of early Sex Pistols concerts), but such locations are not the international tourist draw on the scale of Abbey Road Studios. Additionally, I would argue the zebra crossing is an entirely tangible aspect of the studios; the crossing exists and is regularly visited by Beatles fans, as well as being monitored 24 hours a day by a CCTV camera.

One lesser-known issue surrounding the zebra crossing further illuminates the mythologisation of Abbey Road. In an unnamed editorial, a Guardian journalist pointed out that:

John's white suit was said to identify a clergyman, Ringo's sombre wear an undertaker, and George's denim a grave-digger, while a ‘coded’ number plate allegedly indicated that Paul was dead, a seeming truth confirmed by the bare feet with which he stepped onto the crossing. All great fun, and enough to justify the listed status, the posing tourists and 24-hour CCTV that keeps a vigil there, except for one snag: it's not the same crossing at all’. (Anon. 2010)

Matt Cooke of BBC News also reported in 2010 that the crossing had been relocated in the 1970s, causing a flurry of activity on Beatles forums. However, Westminster council later retracted their statement, ‘The detail of exactly when and why the crossing was moved from its original location have been lost in the annals of time’ (Cooke Reference Cooke2010). These ongoing rumours, prompting responses from Westminster council and the BBC, are just that. A comparison of published photographs taken by Linda McCartney at the same time as the Abbey Road photo shootFootnote 6 with the 24-hour CCTV footage shows the zebra crossing to be in the identical location now to that in 1967.

Pilgrimage and religion

A number of matters have now been established: Abbey Road is not revered simply owing to the high-profile nature of its prominent artists and recordists, but also owing to matters of cultural heritage and mythology. There are, however, further parallels to be drawn between visitors to Abbey Road Studios and pilgrimage. Many scholars have identified links between fandom and religion, including MacCannell (Reference MacCannell1976) and Cavicchi (Reference Cavicchi1998). In her 2002 article, Tara Brabazon argued that

Abbey Road, as an album, crosswalk, street sign and studio, is a constituent element in visual memory. The crossing has gained a relevance and importance that extends beyond the rim of a vinyl album. Traces of the Beatles are found on that road. As a Beatle tourist guide explained: ‘In Rome, Catholics first visit the Vatican, and Jews in Jerusalem go to the Wailing Wall and manic depressives in San Francisco head straight for the Golden Gate Bridge. But you, the true Beatlemaniac, must go straight to the Abbey Road crosswalk. Nowhere else is more sacred.’ (Brabazon Reference Brabazon2002, p. 5)

Brabazon acknowledges the conflation of Beatles album, geographical location and studio building into a single ‘Abbey Road’ cultural entity. From the perspective of Beatles fans, this collective ‘visual memory’ manifests in Abbey Road Studios as Beatles pilgrimage site with fans travelling from around the world to adorn the wall with messages and recreate the album cover photograph. Cultural commentators, journalists and scholars have reinforced Abbey Road as pilgrimage site; the use of religious terminology and analogy in Abbey Road discourse is significant. In the previous quotes, Roberts and Cohen describe the zebra crossing as ‘hallowed ground’, our Guardian journalist describes the CCTV camera as ‘keeping a vigil’ and Brabazon's tourist guide source describes the studios as ‘sacred’. Religious analogy is so common that, culturally, Abbey Road has become a shrine. Devin McKinney (Reference McKinney2003) attributes much Abbey Road mythology to Fred LaBour's Reference LaBour1969 Michigan Daily article, ‘McCartney Dead; New Evidence Brought to Light’. LaBour's article deconstructed ‘signs’ present in the Abbey Road album cover and argued that Paul McCartney was, in fact, dead. McKinney suggests:

In LaBour's reading, the just-released Abbey Road is a New Testament proclaiming the new Beatle religion, conceptualized by John [Lennon] and predicated on Paul's dead body and risen spirit. (McKinney Reference McKinney2003, p. 279)

LaBour's reading arguably began, but certainly perpetuated, rumours of McCartney's death, citing the Beatles’ clothing and appearance on the Abbey Road album cover as the main evidence base. Regardless of the conspiratorial basis of the rumours, such mythology has crept into the consciousness of Beatles fans the world over. McCartney, Lennon, Harrison and Starr were born and raised in Liverpool, yet for Beatles fans, Abbey Road is the essential destination.

However, the idea that Abbey Road is the temple to the Beatles’ religion has been questioned. Peter Jan Margry argues:

Although the religious realm in the postmodern ‘Disneyesque’ environment is changing, it is questionable whether visitors to or participants in such diverse destinations and occasions as … the Abbey Road zebra crossing … can really be categorized as pilgrims. (Margry Reference Margry and Margry2008, p. 18)

Margry makes a convincing argument, in that ‘secular pilgrimage’ is a contradiction and difficult to conceptualise as pilgrimage at all. However, the argument for Abbey Road as pilgrimage site is substantiated by the presence of ritual. Beatles fans do not simply visit Abbey Road to take photographs and observe. They partake in two important customs: writing on the Abbey Road studio building wall and walking across the zebra crossing.

McCarron (Reference McCarron1995, Reference McCarron, Womack and Davis2006) differentiates pilgrims from tourists while also acknowledging similarities and conflations between the two. McCarron describes pilgrims as sharing a collective ‘worldview’, using the former home of late Queen singer Freddie Mercury as analogy:

Pilgrims to the wall [enclosing Freddie Mercury's home in South Kensington, London], like those who come to Abbey Road, share a worldview which bonds them together even when there are no other visitors present. (McCarron Reference McCarron, Womack and Davis2006, p. 175)

Indeed, it is this shared worldview, coupled with the ritualisation in the Abbey Road visit, that reinforces Abbey Road as pilgrimage site, as opposed to tourist attraction.

Religious subtext also permeates significant works; Kehew and Ryan's (Reference Kehew and Ryan2006) book, Recording the Beatles and Lawrence's (2012) Abbey Road: The Best Studio in the World are presented, quite literally, as ‘chapter and verse’; both books are dominant in size, depth of research and weight. Kehew and Ryan's book is a meticulous, exhaustive technological study of the Beatles’ sound recordings, detailing individual systems down to the very last ohm, breaking down each recording session to the final tape edit. Lawrence's photographical history focuses on intimate shots of the recordists and musicians working behind the magical mystery door. Such texts are definitive and final in both presentation and content: ‘This is the technology used to create Beatles records!’, ‘This is what was going on “behind the scenes!”’

Tourism

Abbey Road's historically revered artists and recordists, as well as the heritage aspects of the studios gather to form a place of historical significance. However, the studio is not only a pilgrimage site visited by what Brabazon called the ‘true Beatlemaniac’ (Reference Brabazon2002, p. 5). McCarron differentiates between Beatles tourists and Beatles pilgrims. He suggests that tourists tend to partake in organised tours, such as Liverpool's ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ or London's ‘Rock Tour’, as he suggests:

Nothing is either ‘magical’ or ‘mysterious’ about Liverpool's ‘official’ Magical Mystery Tour; in this, in fact, lies much of the experience's charm. (McCarron Reference McCarron, Womack and Davis2006, p. 175)

McCarron identifies that pilgrims plan their trips to Abbey Road in detail; they often travel in groups and to meet with other like-minded individuals and to partake in the graffiti wall and zebra crossing rituals. Yet the mythologisation of Abbey Road Studios is again exemplified in the recent confusion surrounding its location. Owing to continuing cases of mistaken identity at Abbey Road Docklands Light Railway Station in West Ham, a light-hearted notice incorporating many names of Beatles hit records has been displayed since January 2013:

Day tripper looking for the Beatles pedestrian crossing? Unfortunately you are at the wrong Abbey Road. However, we can work it out and help you get back to the correct location. Take the DLR one stop to West Ham and change to a Jubilee line train to St John's Wood station. Passengers need a ticket to ride. The End. (Transport for London 2013)

The sign is significant and necessitated by repeated requests not for Abbey Road Studios per se but for the zebra crossing made famous on the cover of the Beatles’ Abbey Road album. The volume of confused visitors warrants the notice, but it is not aimed at Beatles ‘pilgrims’. As McCarron argues, pilgrims meticulously plan their trips to Abbey Road and often visit in groups. Such is the prominence of Abbey Road Studios in collective popular memory that it has, in recent years, become an ad hoc tourist destination. However, Abbey Road as pilgrimage site and as tourist destination should not be conflated. The destination is the same, but the journey is entirely different. Tourists may visit Abbey Road as part of an organised tour, such as London Beatles Walks with Richard PorterFootnote 7 and the London Rock Music Tour.Footnote 8 In these instances, Abbey Road is not a stand-alone destination, but part of wider rock music history, along with the personal residences of the posthumous rock canon: Jimi Hendrix, Freddie Mercury and, more recently, Amy Winehouse. The presence of the aforementioned sign at Docklands Light Railway station Abbey Road suggests that, in the last few years, tourists have been visiting Abbey Road spontaneously. From the London Underground or railway map, tourists have mistaken Abbey Road station as the site of the zebra crossing and made the trip without researching the precise location. Abbey Road as pilgrimage site appears to have become so prominent that the journey and rituals have spilled over into general London tourism. The lines between pilgrimage and tourism, as McCarron pointed out, are becoming blurred.

Mythology: the tangible and intangible

So far established is the conflation of artists, recordists and heritage/pilgrimage/tourist site into an ‘Abbey Road’ cultural entity. Yet what about the aura within the studio building itself?

Alan Williams (Reference Williams2010) suggested that

The creation of popular music touchstones has historically taken place in settings inaccessible to the general public – commercial recording studios. While the artifacts of these endeavors, the recordings, are an example of mass culture eroding the class distinctions of art prior to the mid-twentieth century, the tools and environments utilized in the creation of these works remained restricted to a well financed few. (Williams Reference Williams2010, p. 166)

This observation is critical in our understanding of how and why Abbey Road became a symbol of iconicity and mythology. Williams is right, in that albums from the rock canon, as portrayed through the Classic Albums series, carry a depth of public interest going far beyond the liner notes. As the music industry moves further away from the so-called ‘golden age’ of pop and rock recording, its associates – the musicians, recordists, television and radio hosts of the era – fade into popular memory, only to be occasionally recalled in historical and/or biographical accounts. As Beatles biographer Hunter Davies said in May 2013, ‘The further away we get from the Beatles, the bigger they get’ (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2013).

As set out in Figure 1, the inextricable nature of Abbey Road recording studios and the work of the Beatles, particularly their 1969 album Abbey Road, is such that any discourse surrounding the recording studio inevitably involves the Beatles and vice versa; therein lies the heritage value. Since the group disbanded in 1970 and Lennon and Harrison are deceased, reception of Beatles music is primarily achieved via their sound recordings. Live performance is only accessible through the single remaining public performer, Paul McCartney. It is no wonder then that the Beatles legacy rests on the shoulders of Abbey Road Studios.

However, this presents a dilemma: on the one hand, the studio is a tourist attraction in itself. Yet neither of the zebra crossing and graffiti wall rituals presents a business opportunity to the studios, unless fans are charged to cross the road. Abbey Road is not open to the public, yet the workplace has managed to create a corporate brand around its mythology, effectively using its past to secure its future. The studios have thus created new revenue streams from branding two key areas: the ‘tangible’ and ‘intangible’. So, on the one hand, the studio has its sound recordings as artefacts, merchandising – available online and at the Abbey Road Cafe at St John's Wood station – the physicality of the studio building itself to include the wall frontage and the zebra crossing. On the other hand, the studio has its aura; the intangible aspects of its history, the ‘magic’, the legacy, the nostalgia, the ‘alchemy’ of its recordists, the technological ‘wizardry’ as depicted through rock historiography, what Eliot Bates called the studio ‘vibe’.

As Alan Williams pointed out, the ‘tools and environments’ that made classic records were ‘restricted’ to an elite few. To those ‘behind the curtain’ as Williams describes, the process of record making involves the organisation of musical work, performance, musicians, recordists, technologies and processual descisions in an appropriate acoustic environment so as to create a representation of a performance and sound recording. Sir George Martin stated that

The choice of recording studio is a matter for the artist and the producer. I naturally prefer to work at AIR studios. Then, I would prefer to use the number 1 studio at Abbey Road, because of its ambience and long reverberation period. (Martin with Hornsby Reference Martin and Hornsby1979: p. 252)

This description of Studio 1 as being preferable owing to the acoustic properties is further reinforced by a former Abbey Road recordist, who stated:

When these first studios were built, Abbey Road was a production tool of the A&R department. It was not set up as a profit centre. It was a manufacturing tool and it was run and controlled by the A&R department, right up until the mid-1970s when it was deemed it had to be a commercial entity in its own right. It had to make money on its own. (Anon. 2009b)

The recordists know and can describe quite accurately the technological and processual elements of recordings made in Studio 2. From the use of Echoplex tape delays and varispeed on ‘Magical Mystery Tour’, to backmasking, four-track overdubbing and the use of the Mellotron in ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, such elements are left only to the imagination of most members of the public and fans.

So, the discourse surrounding the inner-workings of the studio is two-fold. On the one hand are first-hand accounts of a minority workforce describing the workplace as one cog in the wheel of the larger EMI mechanism, making explicit reference to tangible acoustical, technological and processual attributes. Abbey Road has never been open to the public, aside from a few events. To non-studio workers then, the very process of record making is something resembling alchemy, an intangible, unimaginable sequence of events involving ‘magic’ and ‘wizardry’. Such semantics occur time and time again in popular cultural commentary, reinforcing a perception of recordists as wizards, recording studios as magic houses. Gibson attributes such semantics to musicians also, ‘Musicians have repeatedly argued that there is an inexplicable “magic” in certain recording rooms’ (Gibson Reference Gibson2005, p. 58).

In February 2013, a 50th anniversary re-recording of ‘Please Please Me’ took place at Abbey Road Studios. Ed Potton reported on the event for The Times:

Outside yesterday snow fell on the famous zebra crossing. Inside, much in the hallowed Studio 2 was as it was when the Fab Four recorded there: parquet flooring, white painted walls, the battered upright piano that featured on Lady Madonna and another that was used for A Day in the Life. Stairs led to the control room where George Martin, the band's producer, once presided. Phil Critchlow, executive producer of the project, said: ‘The room's the same, the microphones are largely the same. As people walk through the door you can see it in their eyes: it's what these walls have heard. They produced this incredible body of work and it was all in that room.’ (Potton Reference Potton2013)

Critchlow beautifully conceptualises public reaction to the inside of Studio 2 – wide-eyed and enchanted by the studio aura. In a 2013 interview with the author, a former Abbey Road recordist corroborated this reaction, ‘Sometimes I take guests in there and they're open-mouthed at it in wonder’ (Anon. 2013). This suggests a marked difference in how the studios are viewed by the minority workforce, as an operating recording facility and the general public, as a captivating place of musical and historical significance. That is not to suggest that all members of the public perceive Abbey Road as ‘magical’, but references to such ‘other worldly’ attributes occur with enough frequency in cultural commentary to suggest that such views are common. Abbey Road Studios recognises this and, in recent years, has capitalised on public fascination with the intangible studio aura.

Aura – ‘80 years of Abbey Road’

The authenticity of a thing is the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced. (Walter Benjamin Reference Benjamin2008 (1936))

I use the term ‘aura’ as Walter Benjamin described, to express the ‘intangible’ atmosphere surrounding, generated and evoked by Abbey Road Studios. In his key 1936 essay, Benjamin argued that the aura of original artworks is lost in the process of mass reproduction. Benjamin did not specifically refer to sound recordings, however the central themes of original art and authenticity are especially relevant to phonomusicology, as Hamilton (Reference Hamilton2003), Struthers (Reference Struthers1986) and Gunkel (Reference Gunkel2008) have recognised in their own works. Benjamin's aura concept is obviously relevant to this study; Abbey Road Studios is not a ‘work of art’ in itself, but it is the original manufacturing location of multiple culturally revered musical works. Indeed the intangible aura of Abbey Road's recording studios is something that has morphed from the ‘alchemy’, ‘magic’ and ‘wizardry’ descriptors in rock discourse into a wholly viable and lucrative commodity today. The aura of the studio is transmitted in multiple ways: through the sound recordings made there; through artists and recordists who worked there; via its surrounding location; through studio merchandise; through the technologies that were used in the studio; and, through photographic and written works pertaining to the studios. One overlooked aspect of Abbey Road Studios is its focus on mastering – the final stage in a music production process. Mastering is a highly specialist, technical process involving subtle, yet important alterations to ‘final master’ recordings frequency balance, dynamic range and overall sonic quality. Mastering has been an important area of Abbey Road's business since the 1980s, with many artists recording and mixing elsewhere, then choosing to master at Abbey Road. This is an effective way of imbuing a recording with the aura of Abbey Road, as it is a more expedient process than recording and mixing and, therefore, much cheaper. One Abbey Road recordist described the boom in digital remastering – the process of taking recordings on older formats, such as cassettes and vinyl and preparing them for CD or other digital carriers – during the 1980s:

We basically had to manage the process between recording studios and manufacturing. So we had all this product coming out of studios. It was glamorous to record anywhere and everywhere at this point. So tapes were coming in from all sorts of sources – some of them better than others – and they would end up in the mastering room. (Anon. 2009a)

This is corroborated by another former Abbey Road recordist, who suggested that mastering – as part of the post-production process – was a key facet of the studios business:

Post production was always a very important part of Abbey Road. Editing, the mastering department, checking white labels, test pressings and all that. Duplication of tapes; a huge amount of cassette duplication. (Anon. 2013)

These mastering and remastering processes imbue recordings with the aura of the studio, in many cases without the artist or recordist ever having set foot in the studio. This is a good – and perhaps the earliest – example of the commodification of studio aura. However, for some, the twenty-first-century commodification of the Abbey Road aura is not a particularly welcome aspect of its evolution:

It's very business, modern branding approach to a beautiful institution and it cheapens it. There's a cheaper attitude. When I was there, the guy running it was Ken Townsend. He preserved Abbey Road as something really wonderful and unique. He cared about the studios, the people who worked there. I don't think that is the case now. And I know whatever targets are achieved one year, staff are exhorted to achieve greater the next year. I think there's incredible pressure and it's based on nothing. (Anon. 2013)

Whilst this Abbey Road recordist expresses nostalgia for a past period in Abbey Road's history, the ‘targets’ and ‘pressure’ referred to cannot be based on ‘nothing’. Moreover, this is indicative of an economic-driven business model where not only sustainability but also profitability is at the forefront of the studio's operations. Unlike many of its contemporaries, Abbey Road Studios was owned and operated by a record company – EMI – until private equity firm Terra Firma took over in 2007. Whilst the above quote highlights the stark contrast in operational focus before and after this takeover, this is not the first time the studio had to cope with operational change:

A big change [to Abbey Road Studios] came in the early 1980s when EMI was taken over by Thorne. For the first time ever, Abbey Road had to become a profit centre. It had to make money. Before that, it was really just a facility for a record company. But there had to be a change in the way the place was run and accountability to its owners. (Anon. 2013)

As featured in Digital Audio Workstation ‘plugins’, television and radio broadcasts, live album recordings, corporate deals, photography and merchandise – even an Abbey Road board game (Gumble Reference Gumble2011) released in conjunction with UK supermarket chain Tesco – the reproduction of Abbey Road's aura sells, and it sells particularly well to Beatles fans. One notable broadcast was Channel 4's 2012–2013 television series, Abbey Road Studios: In Session with Volkswagen Beetle. An eight-episode series broadcasting performances by rock artists Paul Weller, The Maccabees and Jake Bugg among others, the show took an intimate format, placing contemporary artists in a location of deep cultural heritage and meaning. Of course, there is a key link between the studios and the sponsor too, for one of the mythological details of the Beatles’ Abbey Road album sleeve was a parked, white Volkswagen Beetle to the rear left of the cover behind George Harrison. The original white Volkswagen now resides in the ZeitHaus, part of the Volkswagen Autostadt in Wolfsberg, Germany, but it seems even the reissue Beetle evokes some authentic Abbey Road aura.

Abbey Road Studios also markets its aura via a particularly twenty-first-century, entirely digital means. In 2010, Abbey Road released a series of plug-ins; small pieces of audio software designed for integration with digital audio workstations. The first set featured the RS124 compressor – a skeuomorphic representation of the original hardware version, built by EMI engineers for exclusive use in Abbey Road Studios from around 1960 onwards. The RS124 – like many EMI-made systems – were never commercially available, yet their use was widespread across most of the bands and artists recording at the studios. The plug-in, therefore, allows a new generation of music technology consumers an opportunity to purchase not only a previously unobtainable system, but also access to Abbey Road's aura. In 1986, Simon Frith recognised new music technologies as making possible ‘cultural democracy’ (Frith Reference Frith1986, p. 278). More specifically, Alan Durant (Reference Durant and Hayward1990, p. 193) recognised MIDI technology as bringing about ‘a major democratization of music’ and Paul Théberge (Reference Théberge1997, p. 152) identified links between music technology, consumption and ‘idealistic, democratic and utopian rhetorics that are often mobilized in support of such activities’. There is no doubt that, since the advent of digital music technologies in the early 1980s, sound recording and processing devices are now accessible to a greater range of individuals than ever before. Building on Théberge and Durant's findings, Bennett (Reference Bennett and Kärjä2012b) elucidated the role of the music technology press in the past – and ongoing – ‘creation’ of consumers for new music technologies. Of particular note was the depiction in music technology magazines of Abbey Road Studios as both an aspirational goal for amateur recordists and as sonic ‘benchmark’: the very highest standard of sound recording and production attainable. As Bennett suggested:

Fostex's advertisement for their four-track tape recorder as a ‘Fast track to Abbey Road’, implied career progress to a top music industry career. More recently, Future Music ran a front-page headline and main article ‘Master like Abbey Road’. The premise of the article being: Abbey Road mastering vs. a project studio master vs. a home studio master. (Bennett Reference Bennett and Kärjä2012b, p. 140)

In the latter example, the magazine posted their results online without providing their readership with a tangible result. The technological and processual comparison between an elite recording studio, semi-professional and amateur setup masks an ulterior motive. At the heart of the music technology press agenda lies a message that the ‘gap’ between amateur and professional is small and that professional tech-processual standards are attainable with budget equipment and ‘how to’ magazine articles. This, of course, is simply not the case. Yet Abbey Road realises that within the amateur world of what futurologist Toffler called ‘prosumers’ (Toffler Reference Toffler1980) and Axel Bruns called ‘produsers’ (Bruns Reference Bruns2008), a viable market exists. And who better to market Abbey Road's aura to than those who can only dream about working there, attaining the sound recording standards of its recordists and producing the multi-platinum selling records of its artists? Such marketing is epitomised in another of Abbey Road's plug-in releases; REDD – an Abbey Road/Waves collaboration on a plug-in replication of the REDD Mixing Console:

The Beatles, The Hollies, Pink Floyd and countless other luminaries made musical history at Abbey Road Studios, trailblazing a revolution that resonates to this day. And at the heart of it all: The REDD consoles, custom-designed, built by and named for Abbey Road Studios’ in-house Record Engineering Development Department. Renowned for their silky smooth EQ curves, extraordinary warmth and lush stereo imagery, there's something magical about the REDDs that sound like no other consoles. (Waves Audio Ltd 2013)

The REDD plug-in description epitomises the marketing of ‘abstract/intangibles’ as illustrated in Table 1. We have reference to the Beatles, the ‘wonka factory’ style Recording Engineering Development Department at EMI and use of the term ‘magical’ to describe the REDD's sonic character. The REDD console, of course, was just one piece of a typical 1960s, Abbey Road recording signal chain. In reality, a user is recording neither the Beatles, the Hollies nor Pink Floyd. Nor are they operating in Abbey Road's acoustically treated rooms or using the original hardware in conjunction with other processors. It is also highly unlikely that a user will have Alan Parsons or George Martin presiding over their session. The REDD console formed one part of a lengthy and complicated signal chain; separating this out from its much wider technological, historical, personnel and musical context is, therefore, highly problematic. The RS124 and REDD plug-ins are just two examples of a whole range, from EMI's J37 tape recorder to the ‘Brilliance pack’: an Abbey Road/Softube collaboration featuring models of EMI's RS127 and RS135 EQ units.

Table 1. Separating heritage from aura: physical/tangible and abstract/intangible aspects of Abbey Road mythology

In 2012 Abbey Road Studios entered into a business partnership with the Fairmont Group of hotels, allowing guests from 60 of its elite hotels – including London's Savoy – access to the studios, a ‘behind the scenes’ tour and the opportunity to record a song. Brett Schaenfield described the corporate Abbey Road experience thus:

any self-respecting pop culture obsessive would see the opportunity to visit Abbey Road Studios as less a visit than a pilgrimage. English rocker Chris Rea summed it up best in the 1997 documentary The Abbey Road Story: ‘The honesty of it is, it's a bit like St. Peter's in Rome is to a Catholic.’ The biggest difference between the Basilica and Abbey Road? Not just anyone can get in to the studios. Considering the fact that a simple tour is normally elusive to the average (and fervent) fan, Abbey Road Studios’ partnership with The Savoy … becomes even more remarkable. Through the Abbey Road Studios package, visitors get a backstage pass and the chance to stay and play like a pop star. I'm ushered inside the hallowed space of Studio Two, the main recording studio used by The Beatles. I'm here to watch a group of corporate clients record their own ensemble version of ‘Help!’ After nibbling on canapés and sipping nerve-settling prosecco, we are directed to our respective chairs and headphones. (Schaenfield Reference Schaenfield2014)

Schaenfeld's article once again uses religious analogy to describe the studios. Due acknowledgement is given to the fact that such a visit is inaccessible to the average or ‘fervent’ fan. Abbey Road is, however, a commercial business and one means of generating income is by offering such corporate experiences; prices for a private Abbey Road experience begin at £740 per person.Footnote 9 The ‘experience’ of enjoying canapés and prosecco while recording a version of ‘Help’ is, however, as entirely contrived and unrealistic as the expectation of achieving professional recording results with a REDD plug in. This reductive reproduction of the Abbey Road aura is unsurprisingly a contentious issue for its staff. A former Abbey Road recordist described such events:

I think they're cheapening it [Abbey Road's legacy]. I suppose I'm conservative, not politically, but I don't think it needs to be cheapened with stupid bloody plugins. Keep it special and unique. But you can take a load of bankers in there now for a piss-up. It's not as special. However successful this brand is, it's completely unnecessary. They've got a nonsense radio station there now. What bollocks that is! (Anon. 2013)

Referred to here is another interesting example of ‘brand Abbey Road’. During 2013, the studio had its own radio station and broadcast playlists and performances nationally. Once again, this elucidates the transmission of the studio aura, this time via radio.

Public lectures are another way in which Abbey Road Studios capitalises on its aura. In February 2012, I attended a rare public opening to see Brian Kehew and Kevin Ryan's ‘80 Years of Abbey Road’ lecture in Studio 2, along with a museum-like display of past recording technologies. I expected to hear historical details pertaining to the studio systems from the 1930s onwards, related to the technologies on display. Instead, the talk was almost exclusively about the Beatles. Kehew and Ryan made reference to the ‘red chairs’ in Studio 2, delighting in informing a packed audience that, just maybe, one of the chairs they were sat on could have been the one that John, Paul, George or Ringo perched on when recording. Ryan opened the talk by suggesting the audience were sat ‘in a mini museum’; many 1960s recording technologies were on display. I am not suggesting their lecture was uninformative, but it bore no relation to the exhaustive, meticulous detail in their book, that focused upon the technical specifications of Abbey Road's recording technology. In contrast to their book, Kehew and Ryan's lecture played on the ‘intangible’ mythology of the studios that was, in this exclusive setting, now entirely tangible: the red chairs that the Beatles may have sat on, the Studer J-37 tape recorder used to record the Beatles Sgt. Pepper album and the iconic layout of Studio 2, with the staircase leading up to the control room. Kehew and Ryan's quite superficial talk was a stark contrast to their comprehensive book. Public events, however, are not something necessarily embraced by Abbey Road's workforce, as one recordist pointed out:

I think it's a lot of nonsense [public events at Abbey Road]. It's popular with the public because it's a place of fascination. Whether or not they should be allowed in is debatable. I think it destroys something valuable. When I first saw a picture of a recording studio when I was 17 or 18, I thought, ‘that looks like the most wonderful, magical place and nobody knows about it’. And because I've got a great face for radio, I thought, ‘that's where I want to be! I want to be behind the scenes. I don't want people to know about me’. How wonderfully magical. (Anon. 2013)

Here, the Abbey Road recordist directly refers to the studio as a ‘magical’ place threatened by public exposure. As the inner workings of the studio have been slowly revealed, this is perceived as the destruction of ‘something valuable’, revealing something that should remain hidden.

Additionally, further evidence of the marketing of aura could be found in the merchandise for sale at the public lecture and now, through the Abbey Road online store. Abbey Road's logo – a hybrid of the zebra crossing and mixing console metering – adorns the usual t-shirts, mugs and stationary. More significant, is the set of art prints for sale at over £200 each. These limited edition prints feature close-up photographs of the EMI TG12345 console, produced and signed by Director of Engineering Peter Cobbin. The artworks are particularly intimate, black and white photographs of the faders and equalisation dials on the TG12345, which places the controls at ‘touching distance’ from the viewer. Walter Benjamin's noted essay recognised this reproduction in the context of pictures and recordings thus: ‘technical reproduction can put the copy of the original into situations, which would be out of reach for the original itself. Above all, it enables the original to meet the beholder halfway, be it in the form of a photograph or a phonograph record’ (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2008 (1936), p. 3).

Table 1 separates out the physical/tangible (heritage) and abstract/intangible (aura) aspects of Abbey Road mythology. The aforementioned examples of corporate ‘experiences’ and public lectures exemplify the marketing of studio ‘vibe’ and ‘atmosphere’. The plugin skeuomorphs of Abbey Road technologies elucidate the marketing of key, otherwise inaccessible, recording systems to fans and music technology hobbyists. Notions of ‘magic’ and sonic ‘alchemy’, as well as ongoing religious analogy, pepper the marketing discourse. The intangible Abbey Road aura has become a lucrative commodity in its own right.

Summary

Alongside the so-called ‘democratisation of music technology’, we have witnessed a demythologisation of the record studio, as the works of Leyshon (Reference Leyshon2009), Bates (Reference Bates2012) and Théberge (Reference Théberge2004) illustrate. Abbey Road's historical status as the world's ‘best’ or ‘greatest’ studio is not exempt from this; via cultural commentary and increasingly detailed works by Southall et al. (Reference Southall, Vince and Rouse1982), Kehew and Ryan (Reference Kehew and Ryan2006) and Lawrence (Reference Lawrence2012), the intricacies of Abbey Road recording and production processes have been slowly demystified. Such texts act as rational explanations behind the studio ‘magic’. Abbey Road continues to operate as a commercial recording and post production house. In a declining recording sector market its survival, however, is dependent on a combination of studio bookings and the successful commercialisation of its legacy via broadcasts, corporate sponsorships, digital music technologies and events. The studio does, however, remain largely inaccessible. Public visits are confined to rare lecture events and expensive corporate experiences. Abbey Road uses its past to secure its future: the corporate branding of the Abbey Road aura, in conjunction with its existing zebra crossing, graffiti wall and building heritage, assures the studios’ future.