When we uncovered a large gender gap in political ambition among potential candidates in the early 2000s, our research highlighted how far the United States was from gender parity in electoral politics (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004; Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2005). To be sure, scholars and activists had widely decried that as we entered the twenty-first century, no woman had ever seriously contended for the presidency and women occupied only 13% of the seats in Congress.Footnote 1 Change, however, was on the horizon. Most scholarly accounts suggested that the best way to reduce gender disparities in elective office was to increase women’s presence in the professions that tend to precede political careers (Darcy, Welch, and Clark Reference Darcy, Welch and Clark1994). Those increases were well underway, and study after study revealed that when women ran for office, they fared at least as well as men (for a review, see Lawless Reference Lawless2015). As women continued to move toward parity in fields such as business and law, their candidacies would follow.

Findings from our Citizen Political Ambition Study, however, suggested otherwise. Women and men who worked in the pipeline professions most likely to precede a candidacy—law, business, education, and politics—were not equally interested in running for office. Although these potential candidates held the same credentials and operated in similar professional spheres, women were less likely than men to have ever considered running for office. The findings were so stark that numerous scholarly inquiries aimed to assess and contextualize the ambition gap. Some studies focused on gendered traits and behaviors contributing to women’s election aversion (Kanthak and Woon Reference Kanthak and Woon2015). Other research focused on structural and partisan dynamics (Crowder-Meyer and Lauderdale Reference Crowder-Meyer and Lauderdale2014). Still other work experimented with interventions to identify factors that might increase women’s interest in a candidacy (Karpowitz, Monson, and Preece Reference Karpowitz, Monson and Preece2017). Closing the gender gap in political ambition became more than a topic of scholarly intrigue. It also became a rallying cry for organizations seeking to increase women’s numeric representation (Kreitzer and Osborn Reference Kreitzer and Osborn2019).

Although US political institutions remain far from gender balanced—that is, men occupy more than 70% of the seats in Congress and 75% of state governorships—women’s numeric representation has improved markedly in recent decades. Since 2001, women’s presence in state legislatures has increased by almost 50%; in Congress, it has doubled. Several viable female presidential candidates have emerged. Hillary Clinton won the popular vote in 2016. And voters elected a female vice president in 2020.

Many might be tempted to assume, therefore, that the gender gap in political ambition has begun to close. Results from our new study of potential candidates, however, reveal that the gender gap in political ambition was as large in 2021 as it was 20 years earlier. Two primary explanations for the gender gap—differences in self-assessed qualifications to run for office and external support for a candidacy—remain unchanged as well. Advocates for diversifying US political institutions can find solace in recent electoral trends. But given that a central criterion in evaluating the health of democracy is the degree to which citizens believe it is open and accessible to them, the seemingly invincible gender gap in political ambition continues to upend notions of democratic legitimacy.

Results from our new study of potential candidates, however, reveal that the gender gap in political ambition was as large in 2021 as it was 20 years earlier.

ESTABLISHING THE GENDER GAP IN POLITICAL AMBITION

To examine the role of gender in potential candidates’ interest in running for office, we consistently have relied on a candidate-eligibility-pool approach. In 2001 and 2011, we compiled national samples of equally credentialed women and men who worked in the four professions most common among state and federal officeholders.Footnote 2 To gauge political ambition, we asked potential candidates whether they ever considered running for office. This measure of nascent ambition includes those who seriously considered running for office and those who only thought about it from time to time.

Among a national sample of more than 3,500 well-credentialed potential candidates in 2001, a large gender gap in political ambition emerged: 59% of men had considered running for elective office compared to 43% of women (figure 1). Interest varied across federal, state, and local positions, but the gender gap was significant across the board. Ten years later, the results were strikingly similar: the gender gap held steady at 16 percentage points.

Figure 1 The Unchanging Gender Gap in Political Ambition among Potential Candidates

Bars represent the percentages of potential candidates who reported that they ever considered running for office, as well as the gender gap (in percentage points) at each point in time. Panel (A) includes women and men who work in law, business, education, and politics. Panel (B) supplements that sample in 2021 with 2,667 respondents who are college educated and employed full time but do not hold the same positions as those in the Four Professions Sample. The gender gap is significant at p<0.05 in all comparisons. Sources: Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2005, Reference Lawless and Fox2011, and our 2021 YouGov survey of potential candidates.

New results—based on a 2021 survey we fielded through YouGov—reveal that little has changed in 20 years.Footnote 3 The third set of bars in figure 1 indicates that the gender gap in political ambition within the four eligibility-pool professions was virtually the same size as it was both 10 and 20 years earlier. The gap also is the same when we expand our conception of the candidate-eligibility pool. Because there now is more diversity in careers preceding a political candidacy than there was two decades ago, we supplemented the sample with more than 2,600 potential candidates who are college educated and employed full time but do not hold the same positions as those in the Four Professions Sample.Footnote 4 An important advantage of broadening the sample is that it allows for more racial diversity. The broader sample includes almost 20% more people of color than a sample of only lawyers, business leaders, educators, and political activists (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2023).Footnote 5 As we might expect, overall interest in running for office is somewhat lower among the broader sample, but the gender gap in political ambition remains the same size (see figure 1, panel B).

It is important to note that the gap persists across demographic groups and generations. Even among potential candidates younger than 40, men are 18 percentage points more likely than women to have considered a candidacy. The magnitude of the gap does vary within some categories: it is larger for Republicans than Democrats (two thirds of the difference is the result of lower ambition among Democratic men), and white women are more likely than women of color to report interest in running for office. Yet, women and men have not achieved parity in political ambition in any demographic category.Footnote 6

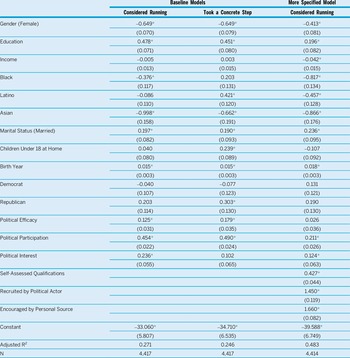

When we move to a multivariate context, the gender gap withstands controls for key political factors, such as political interest and participation, and a host of demographics (table 1, column 1).Footnote 7 Respondents with higher levels of education, as well as those with greater levels of political interest and political activity, are (as we would expect) more likely to consider running for office. Nevertheless, all else equal, white women, Black women, Latinas, and Asian women are 11 to 16 percentage points less likely than their male counterparts to consider running for office (p<0.05).Footnote 8

Table 1 Potential Candidates’ Interest in Running for Office

Notes: Entries represent logistic regression coefficients (and standard errors) predicting whether a respondent ever considered running for office or took a concrete step that often precedes a candidacy.

* p<0.05.

Finally, it is important to note that the gender gap in political ambition is not merely a difference in abstract notions of what women and men believe a candidacy means. The gap is significant when we measure political ambition by examining behavior: whether a potential candidate has taken any concrete steps that typically precede running for office. Whereas 30% of men reported taking at least one step—for example, spoke to party leaders, discussed running with friends or family, discussed financial contributions with potential supporters, investigated how to get on the ballot, spoke to candidates about their experiences, or attended candidate-training sessions—only 18% of female potential candidates did so (p<0.05). These differences remain in a multivariate context (see table 1, column 2). The gap also is significant when we consider whether potential candidates actually ran for office (8% of men compared to 4% of women; p<0.05).

THE ENDURING ROOTS OF THE GENDER GAP IN POLITICAL AMBITION

The gender gap in political ambition has held steady throughout a period of notable change in US politics. During the first two decades of the twenty-first century, the toxicity of the electoral environment skyrocketed; party polarization reached new heights; money pouring into national elections more than quadrupled; and social media facilitated the spread of misinformation, personal attacks, and a loss of privacy for candidates. Yet, overall interest in running for office has been stable—for both men and women—since 2001 (see figure 1, panel A). The gap, therefore, transcends political climate.

The static nature of the gap affirms how deeply embedded it is in US political culture. Indeed, we argued in the first wave of the Citizen Political Ambition Study that the gender gap was the product of historic patterns of “traditional gender socialization.” This term refers to the perpetuation of gender norms that orient people to be more likely—consciously or subconsciously—to view men as political leaders (Costantini Reference Costantini1990; Sapiro Reference Sapiro1982). Two manifestations of traditional socialization—one internal and one external—that explained the gap in 2001 are as prominent two decades later.

Internal Assessments: Self-Perceived Qualifications to Run for Office

Traditional gender socialization often leads men to conclude that they are well suited for politics and women to believe that they do not possess—or will be penalized for exhibiting—the qualities that the electoral arena demands of candidates (Guillen Reference Guillen2018). When women do participate in an historically masculine environment, they often believe they must be better than men to succeed (Bauer Reference Bauer2020).

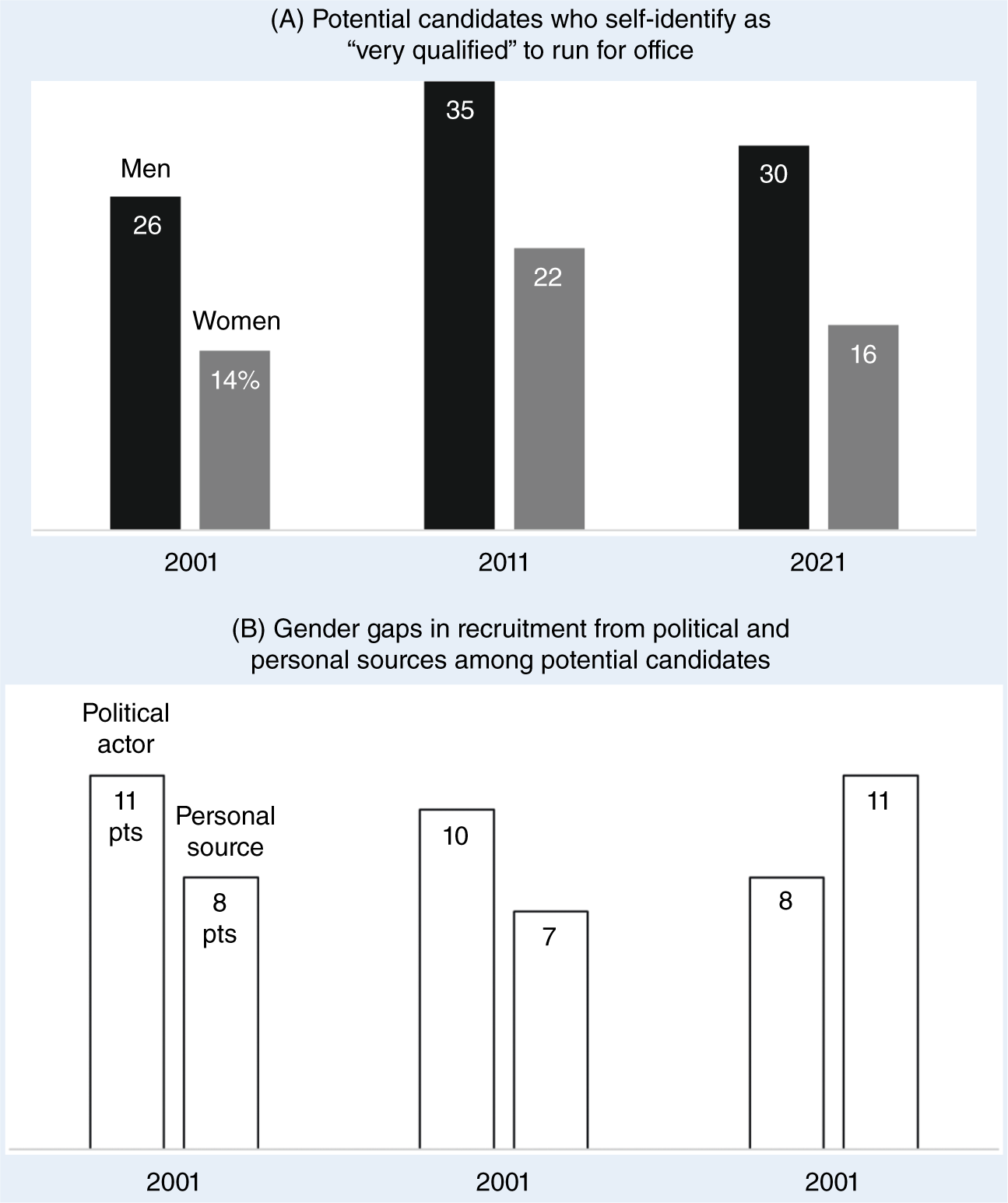

Among potential candidates with almost identical professional profiles, political experiences, and relevant credentials, men in 2021 were almost twice as likely as women to consider themselves “very qualified” to run for office (30% compared to 16%; p<0.05). This gender gap was approximately the same size in both 2001 and 2011 (figure 2, panel A). Women were more than twice as likely as men to self-assess as “not at all qualified” to run for office (30% versus 14%; p<0.05).

Figure 2 Roots of the Gender Gap in Political Ambition: Internal and External Assessments

Panel (A) represents the gender differences in self-assessed qualifications; Panel (B) represents the gender gap in political recruitment at each point in time. Political actors include elected officials, party leaders, and nonelected activists. Personal sources include spouses and partners, family members, colleagues, and friends. Sources: Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2005, Reference Lawless and Fox2011, and our 2021 YouGov survey of potential candidates.

Similar perceptual differences emerged in response to questions about specific experiences and credentials. Whereas 72% of men in the sample believed they were very knowledgeable about public policy, only 49% of women felt the same way (p<0.05). This is notable because women were 14 percentage points more likely than men to believe that policy expertise is essential in a candidate. Men also were more likely than women to believe that they handle criticism well (60% of men versus 38% of women; p<0.05). Again, this is a potent difference given that 71% of women thought that being able to withstand scrutiny is an important quality in a candidate.

These perceptions likely reflect a combination of women underestimating their qualifications and men inflating theirs. Women’s lower self-assessments, however, are not simply a result of traditional socialization. They also are a warranted response to a political environment that women perceive to be biased again them. In fact, almost nine of 10 women in our sample think of the political arena as one in which women face more scrutiny and challenges than men. Female potential candidates live in a political world that conveys to them that women will be held to a higher standard than men.

The differences are critical because self-assessed qualifications correlate strongly with the gender gap in political ambition (see table 1, column 3). The average white female potential candidate who does not think she is qualified is not likely to consider running for office (the probability is 0.14). All else equal, that probability more than doubles (to 0.36) if she thinks she is “very qualified.” White men also are more likely to express interest in running for office when they think they are very qualified (0.46 probability compared to 0.19), but they are more likely than women to find themselves in that category in the first place. The pattern is the same for Black women, Latinas, and Asian women, all of whom experience a similar predicted tripling of the likelihood of considering a candidacy when they move from “not at all” to “very” qualified to run for office.Footnote 9

External Assessments: Encouragement to Run for Office

Most political institutions are dominated by men and embody an engrained ethos of masculinity. Even if the men who occupy positions in these institutions no longer exhibit overt bias against women, years of traditional conceptions about candidate quality, electability, and background persist (Bjarnegård and Kenny Reference Bjarnegård and Kenny2015). Some political gatekeepers and many citizens continue to think of men, not women, as future political leaders. Among potential candidates in 2001 and 2011, this ethos manifested as a substantial gender gap in encouragement for a candidacy from both political actors and personal sources (see figure 2, panel B).

The 2021 data do not appear much different. Turning first to recruitment from political actors—elected officials, party leaders, and political activists—women remain less likely than men to receive support to run for office. Whereas 11% of men were recruited by an elected official, only 7% of women were (p<0.05). The gap is similar (11% compared to 6%; p<0.05) for party leaders. Overall, in terms of support from at least one political actor, women were 8 percentage points less likely than men to report receiving encouragement. From personal sources—family members, spouses and partners, and colleagues who know them best—the gender gap was even wider.

Potential candidates are far more likely to express interest in running for office when they receive support. All else equal, receiving the suggestion to run for office from a political source dramatically increases a woman’s likelihood of considering a candidacy (e.g., the probability for a white woman increases from 0.23 to 0.56; for a Black woman, from 0.12 to 0.36). Encouragement from a personal source is even more powerful: the probability increases from 0.16 to 0.45 for a Latina and from 0.11 to 0.35 for an Asian woman. When women—of any race—receive encouragement from both political actors and personal sources, they are more likely than not to consider running for office.Footnote 10 The same is true for men, but they are much more likely to receive the support that can bolster notions of a candidacy.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Despite dramatic shifts in the political environment throughout the past two decades, running for office remains a far more remote endeavor for women than for men. Moreover, the roots of the gender gap remain as deeply entrenched as they were two decades ago. How then can we reconcile the intractable nature of the gender gap in political ambition with women’s steadily increasing numeric representation?

Despite dramatic shifts in the political environment throughout the past two decades, running for office remains a far more remote endeavor for women than for men.

One explanation might be what we call a representation paradox. Many scholars assumed that as women’s candidacies for high-level office became routine, more women—especially younger women—would see the political system as open to them (Ladam, Harden, and Windett Reference Ladam, Harden and Windett2018; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007). Representation in US political institutions, in other words, would trickle down to the candidate-eligibility pool. Female potential candidates would come to embrace the possibility of a candidacy as they observed increasingly more women in positions of political power.

What scholars did not necessarily account for was the way potential candidates’ perceptions of how female candidates are treated might offset any positive effects. There is no evidence at the aggregate level of systematic bias against female candidates—women running for Congress, for example, win just as often, raise just as much money, and receive comparable news coverage as men (Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2016). But instances of sexism and discrimination against women in politics persist. Indeed, on both sides of the political aisle, high-profile women running for office encounter sexist attacks, typically from an opponent or a political pundit. These instances need not be frequent or ubiquitous. Rather, because sexism on the campaign trail is covered extensively, many potential candidates may extrapolate from these highly publicized episodes and infer that gender bias is pervasive across all elections, for all offices, and can determine outcomes (Haraldsson and Wängnerud Reference Haraldsson and Wängnerud2019; Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2016). The proliferation of high-profile female candidates results in more opportunities to witness these examples.

Potential candidates’ perceptions of politics support this speculation. In 2016, for example, Hillary Clinton raised more money than Donald Trump and won the popular vote. Yet, on the heels of that election, a large majority of female potential candidates believed that women have a more difficult time than men raising money and that voters are biased against women who run for office (Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2017). Among female potential candidates in 2021—only one year after Kamala Harris was elected vice president—approximately 66% of Republican women and 96% of Democratic women contended that women face more challenges than men when they run for office. Women also were 12 percentage points more likely than men to agree with the statement: “Someone like me would have a hard time running for office.” The emergence of high-profile, heavily scrutinized female candidates may reinforce the perception that women venturing into the electoral arena will face an inhospitable environment. Their relatively lower level of interest in running for office likely is linked to their perception of an unfair system. Accordingly, even as women’s numeric representation increases, the “trickle-down effects” may be mitigated by their heightened sense that they would have to be twice as good to get half as far as their male competitors.

A second way to reconcile the static gender gap in political ambition with women’s increasing numeric representation is the simple math required for gender parity in electoral outcomes. It is possible to increase women’s numeric representation by targeting a relatively small number of women to run for specific offices, despite unequal numbers of politically ambitious women and men. Political gatekeepers would need to recruit and elect only a couple hundred women to achieve gender parity in Congress or a few thousand women to achieve parity in state legislatures. Increasing women’s numeric representation and closing the gender gap in political ambition do not have to go hand in hand.

Although we can attempt to reconcile a static gender gap in political ambition with women’s growing presence in US political institutions, it is important to not lose sight of their continued underrepresentation and how the ambition gap contributes to it. The United States ranks 71st globally in the percentage of women serving in the national legislature (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2023). At the current rate of progress, women will not hold half of the seats in Congress until 2108 (Institute for Women’s Policy Research 2020). If the notion of entering the electoral arena never occurs to someone, then he or she will never take the leap. As long as the gender gap in political ambition persists, it will be more challenging to find women to fill at least half of the more than 500,000 elected positions in the United States.

The gender gap in political ambition also is a critically important barometer for gauging gender equity in US politics. Full political inclusion in a democracy demands that women are not systematically less likely than men to envision themselves as elected leaders. Despite their entrance and ascension into formerly male fields such as law, science, and business, women in the candidate-eligibility pool continue to exist in a society that leads them to undervalue their credentials and qualifications, receive less encouragement to run for office, and have trouble perceiving themselves as political candidates. The move toward gender parity in elective office that scholars in the 1980s and 1990s hoped for is (slowly) underway, but much work remains if the goal is a society in which women do not have to be concerned about being taken seriously as candidates and are as comfortable and interested as men in seeking the reins of political power.

The move toward gender parity in elective office that scholars in the 1980s and 1990s hoped for is (slowly) underway, but much work remains if the goal is a society in which women do not have to be concerned about being taken seriously as candidates and are as comfortable and interested as men in seeking the reins of political power.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kathy Dolan, Danny Hayes, John Ferejohn, Adam Thal, and participants at the New York University Law School’s Colloquium on Law, Economics, and Politics for comments on drafts of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KO3FID.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096523000926.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.