Latinos in the USA have disproportionately high rates of overweight and obesity, both of which are associated with a diet that lacks sufficient whole grains, fruits and vegetables and contains excess quantities of sugary beverages and sweetened baked goods( Reference Carrera, Gao and Tucker 1 ). A poor and unbalanced diet is the underlying cause of diet-related chronic diseases, now a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world( Reference Murray, Atkinson and Bhalla 2 ). Moreover, as US-based Latinos become acculturated, they are more likely to consume fast foods and street foods, which often contain too much energy and lack critical nutrients( Reference Ayala, Baquero and Klinger 3 ). Improving the quality of away-from-home foods, as well as reducing excess energy, will be a critical step towards reducing the high prevalence of chronic diseases.

Mobile food trucks called ‘loncheras’ are common sources of inexpensive away-from-home foods among working-class Latinos and others( Reference Hermosillo 4 , Reference Hernández-López 5 ). Loncheras get their name from the Spanglish lonche, a play on ‘lunch’. The food trucks usually park at a single location every day for up to 10 h while serving ready-to-eat Mexican and/or other types of food( Reference Hermosillo 4 ). In 2013 there were 2580 licensed food trucks in Los Angeles and an estimated 2000 unlicensed ones( Reference Hermosillo 4 ), compared with the 26 000 restaurants in the county( 6 ). The trucks often go to factories, construction sites and other places where traditional restaurants are not available. Typically, loncheras serve popular Latino fast-food items like burritos and tacos, and, like other fast-food outlets, offer insufficient fruit and vegetable options, providing the kinds of foods to which Latinos are accustomed( Reference Carrera, Gao and Tucker 1 ).

In general, food choices are habitual and in fast-food settings may be quick and impulsive( Reference Wood and Rünger 7 ). What is chosen is highly dependent upon what is available. Customers may not be very health-conscious and may make decisions about what to eat based on superficial characteristics like quantity, price, placement of food options on menus and menu boards, or other contextual factors, of which individuals may not be consciously aware( Reference Cohen 8 – Reference Dijksterhuis, Smith and van Baaren 10 ).

One solution that has been proposed to improve the foods consumers choose is to make healthy options more convenient and accessible( Reference Otten, Hekler and Krukowski 11 ). Currently, an estimated 94 % of all meals in the most popular US chain restaurants do not meet the national dietary guidelines( Reference Wu and Sturm 12 ). Exacerbating the problem of poor nutritional content of away-from-home foods is the increase in their portion sizes( Reference Nielsen and Popkin 13 ). A majority of people now eat away from home routinely such that away-from-home foods contribute an average of one-third of daily energy, even though this represents fewer than one-third of all eating occasions( Reference Lin and Frazao 14 ). Experimental studies show that the amount people consume depends on the amount that they are served( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 15 , Reference Diliberti, Bordi and Conklin 16 ). In studies where individuals were routinely provided with excess energy, they did not naturally compensate by eating less at subsequent meals( Reference Diliberti, Bordi and Conklin 16 – Reference Rolls, Roe and Meengs 19 ).

In order to address the problem of poor dietary options compounded by poor consumer decision making, we conducted a pilot study to encourage loncheras to offer more nutritious meals. The primary goals were to assess whether any lonchera owners would be willing to redesign some meals on their menus and whether they would be able to comply with the predefined volume and weight measures for these meals. We also wanted to find out whether predominantly Latino customers would find such standardized meals appealing and whether the meals could potentially be profitable.

Methods

Our study design was primarily observational. Initially, to assess enthusiasm for the project and to identify potential barriers, we interviewed members of a trade association of Latino ‘loncheros’, the owners of the loncheras trucks. We found that while a few owners were interested in trying something new, most were willing to do so only if they perceived their clientele to be interested in healthier options and if they thought that offering them could yield greater profits.

To encourage enrolment we offered participants free consultation with a bilingual dietitian who would help them reformulate existing meals to meet the My Plate guidelines, typically by including more fruits and vegetables and less meat. Once the meals were designed, we offered free photography and the creation of posters to be affixed to the sides of the trucks with pictures of the new meals, $US 2·00 coupons to incentivize purchases of the new meals, free assistance creating Yelp pages to help market the truck and promotion through local media to attract more attention to their businesses. We also offered a $US 250 incentive for participation.

Recruitment

Our goal was to recruit a convenience sample of twenty loncheras. We initially sought participants among members of the Asociación de Loncheros La Familia Unida de California. From Los Angeles County’s list of licensed providers we also mailed invitation letters in English and Spanish to 464 owners with Hispanic surnames. We did not receive any replies and many letters were returned with ‘addressee unknown’. We therefore turned our focus to in-person recruitment and approached and enrolled lonchera owners and staff at six commissaries, where their vehicles were parked. All participants who enrolled signed informed consent, following procedures approved by the RAND institutional review board.

Once enrolled, we obtained information about the lonchera owners’ educational attainment and also the type of location in which they did business. The classification of neighbourhood was based on the land use (industrial, commercial or residential) on the street where the lonchera was parked.

In order to develop healthier meals, the bilingual dietitian scheduled at least four visits with the owners and cooks to create new meals. Each visit lasted 30 min to 1 h and included: (i) education on general nutrition principles of My Plate and the impact food has on the body; (ii) assessment of existing menu items and discussing the possibility of offering at least one meal that follows My Plate guidelines; (iii) introduction of kitchen optimization and recipe standardization to control energy content of meals offered; and (iv) observation of owner and staff creating a meal that follows My Plate principles to check that appropriate ingredients and portion sizes were used.

Meal development

The project applied the concept of My Plate, the US Department of Agriculture recommendation for a balanced meal, to a Latino context and studied its feasibility and acceptability among consumers. Based upon the average daily requirement of 2000 kcal (8368 kJ), we used the following as the meal standard: at least 1 cup of vegetables, ½ cup of fruit, 1–3 oz of whole grains, ≤3 oz of meat or meat equivalent, 1 cup-equivalent of milk (or 1·5 oz of cheese) and ≤700 kcal (≤2929 kJ).

We chose volume and weight measures recommended by the Child and Adult Care Food Program as the primary determinant of the meal standards because of concerns about the capacity of food providers to assess energy( 20 ). These are potentially superior to menu labelling in that they define default portion sizes, which reduces the risk of people being served too much( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 15 ).

The dietitian first looked at existing meals on the menu, examined the recipes and measured the quantity of foods usually served. In general, loncheras served 6 oz or more of meat or seafood, refined-grain products like white rice (usually more than 8 oz) or white flour tortillas, and insufficient fruit and vegetables. Some meals included cheese, but others, especially meals with seafood products, lacked any dairy. Based on these findings, suggestions were made to alter the quantities of foods served to meet the My Plate standards and to add a fruit, vegetable and dairy item, where lacking. For seafood meals where adding cheese was not an acceptable option, the owners agreed to try to offer a side of yoghurt with fruit. We substituted refined-grain products with whole-grain products, where possible.

Once meals were redesigned we scheduled a ‘taste test’ to check that recipes were both compliant and appealing. The meals were professionally photographed and displayed on the side of the truck, with the logo ‘La Comida Perfecta’ (‘the perfect meal’) to help people recognize the meal.

Measures

Customer preferences

We conducted two types of surveys to understand customer preferences and reactions: one self-administered via a coupon, the other through an intercept survey. We printed $US 2·00 coupons for loncheras staff to offer to the first 100 customers who purchased a La Comida Perfecta meal. Questions were printed on the back of the coupon and customers could receive the $US 2·00 discount when they completed the survey. Intercept surveys were conducted by project field staff during busy times. Field staff approached customers, offering the $US 2·00 coupon for completing a survey about their food choices.

Sales

Initially we asked the lonchera owners to keep track of their sales, but this proved too challenging with the small number of staff and the pressure of orders during busy times. Instead, field staff visited the loncheras twice per month for 6 months after the new meals were offered during peak times. For about an hour, staff recorded all the orders of foods and beverages by standing next to the order window.

Adherence

In order to assess whether the loncheras continued to adhere to the recipes we anonymously purchased the project’s meals through ‘secret shoppers’, as well as asking the dietitian to obtain a sample of the meals from the trucks approximately 3 months after the meals were available.

Analysis

In order to verify energy content, nutritional analysis of the meals was conducted using ESHA software( 21 ). We used descriptive statistics to analyse the data collected.

Results

We recruited twenty-two owners of twenty-three food trucks. Over the course of the project eleven owners either dropped out or had to be excluded. We excluded four because they failed to renew their business licenses with the county health department. Three dropped out because they considered the programme too much of a burden. We lost contact with two, who may have left the country. One sold his business and one truck had mechanical problems and could not continue. The characteristics of the loncheras completing the project are provided in Table 1. Nearly 75 % of owners were male and came from either Mexico or El Salvador. Of the eight for which we had information on educational attainment, four did not go beyond elementary school. Only one was a college graduate. On average they had been in business for about 15 years.

Table 1 Characteristics of loncheras completing the study, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013–2014

Customer response

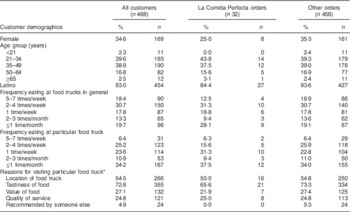

We fielded 488 customer surveys (average of forty-one per truck). The average customer age was 38 years, 65 % were male and 93 % identified as Latino (Table 2). The majority of customers (66 %) surveyed ate at food trucks at least once weekly, with 49 % eating there twice weekly or more. Most selected the specific lonchera for the taste of the food and the location of the truck. Although healthy options were available, nearly 60 % of customers ordered their ‘usual’ or came to the lonchera with a specific purchase already in mind. Over 95 % of the customers surveyed thought the My Plate meals ‘look tasty’. Customers redeemed 337 coupons. Those who purchased La Comida Perfecta meals gave them high ratings; 97 % said they would recommend them to others and 97 % said they would buy them again.

Table 2 Customer demographics by type of order at studied loncheras in Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013–2014

* Customers could list multiple reasons for visiting the particular food truck.

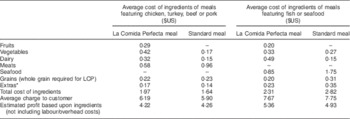

Meals and potential profitability

Altogether, fifty different La Comida Perfecta meals were created by participants. Table 3 shows the average cost of ingredients and the average amount charged for the meals in comparison to meals that were previously served.

Table 3 Cost of meals and ingredients at studied loncheras in Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013–2014

LCP, La Comida Perfecta meals.

* Salsa, butter, sour cream, avocado, beans, tortilla chips, mayo, olive oil, salsa verde, salsa roja, spices, butter, walnuts, dried cranberries, lime juice, mayo, egg.

The original meals typically contained no fruits, fewer vegetables, and about twice the amount of meat/seafood as the La Comida Perfecta meals. The cost of ingredients for La Comida Perfecta meals with meat was slightly higher than for the standard meals with meat. However, the La Comida Perfecta meals with fish or seafood cost slightly less to prepare than the comparable standard meals. Considering only the cost of ingredients, the margin of profit for La Comida Perfecta meals was about the same as for standard meals, but higher than standard seafood meals. However, there are likely additional labour costs for which these calculations do not account, due to having to source and prepare fruits and vegetables, previously not offered. Unfortunately, none of the loncheras had any electronic point of sale system that would enable them to pinpoint the items from which they earned their greatest profits.

Sales of La Comida Perfecta meals

Overall, La Comida Perfecta meals represented 2 % of all orders made during our sales audits. If beverages, desserts and other items not bundled with a meal were excluded, they would represent nearly 4 % of all sales, which was similar to the rate of purchase of many individual categories among the many dozens of items available. However, the distribution of sales varied considerably by the truck and the typical customer base for each truck. It was more difficult to promote the La Comida Perfecta meals at food trucks where seafood was the main menu item or for trucks specializing in tacos. Customers often came just for snacks of tacos or seafood cocktails and were less interested in purchasing a full meal. Rather than offering too little food, the most common concern was that the La Comida Perfecta meal had too much food. The greatest successes were among trucks that already specialized in serving meals for a lunch or dinner crowd in white collar or residential areas. It is worth noting that, among beverage orders, the vast majority of customers ordered drinks with high sugar content, with 58 % being sodas, sports drinks or sweetened teas (see Table 4).

Table 4 Typical sales from studied loncheras in Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013–2014 (188·5 h of observation; 8091 total orders)

Adherence and sustainability

Table 5 shows how well the trucks complied with the original recipes. Because of changes in hours of services and/or route changes, we were able to follow-up ten trucks and the dietitian was able to assess seven of the twelve loncheras. Only one truck monitored by the dietitian was able to successfully adhere to the original recipe. The most common mistakes were to offer insufficient dairy or fruit and to disregard the whole grain requirement. Loncheras had difficulty sourcing whole-grain products to use in their meals, especially for whole-wheat burrito-size tortillas. Although some initially said they would offer brown rice, it was difficult to prepare and customers often asked to substitute white rice, so they ended up throwing away most of the brown rice at the end of the day. Most of the meals had the appropriate amount of meat and vegetables. Most substituted an ingredient that was not on the original recipe, but did so appropriately, so that the meal still largely met the standards. We discovered that the frequent turnover of staff contributed to the drift away from standards, since some new cooks were not aware of the La Comida Perfecta recipe standards.

Table 5 Results of fidelity checks of studied loncheras in Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013–2014

w/o, without; n/a, not applicable.

* Eleven fidelity checks performed (ten trucks).

† Seven fidelity checks.

‡ A total of seven items did not follow the original recipe.

At the end of the project, 75 % of the eleven loncheras completing the programme said they would continue offering the new meals. While our audits captured a relatively low percentage of sales of the La Comida Perfecta meals, the owners reported that they were selling greater quantities than we estimated. Many of the participating lonchera owners believed the meals attracted and helped them maintain new customers.

Discussion

Our findings underscore the importance of loncheras to influence the diet of their customers, the majority of whom patronize these businesses on a regular basis. While at follow-up there was some drift away from the standards, our project shows that establishing standards for meals is feasible and loncheras are largely able to implement and meet the standards. Just as health departments routinely monitor food outlets for adherence to hygienic standards, we believe that with continued monitoring and feedback non-adherence could be corrected. Making additional training opportunities available to new food workers may address this too. Although we had trained the staff present when the intervention started, there was no mechanism established to train new staff hired afterwards, which partly explained the adherence drift.

We concluded that our standards had been more rigid than necessary. For example, if we had not had a requirement for dairy, the adherence would have been improved automatically. Other meal guidelines have not included dairy as a necessary component of a healthy meal( Reference Ludwig and Willett 22 ). Although the loncheras preferred to offer fresh fruit as part of the standards, dried fruits or canned or frozen fruits would also have been acceptable, so long as no sugar is added. Problems with sourcing items like whole-grain tortillas would likely decline, if more loncheras adopted these standards.

The biggest challenge we faced was in recruiting lonchera operators to try something new. The demands of running a food truck are intense, leaving little room for innovation. Menus are traditional and most of the lonchera owners we recruited reported they had never introduced a new menu item since they first started their business. Although we offered a substantial incentive for participation, anticipated risks and inertia might have been too great to make this appealing. Another barrier appears to have been immigration status. For example, we do not know whether lonchera owners and their workers were legal immigrants or not, and some may have shied away from participation to avoid any potential legal issues. Several lonchera owners who were interested did not have their trucks properly licensed and were therefore ineligible to participate in the study.

The purchasers of the La Comida Perfecta meals rated them very highly. However, despite favourable reviews, most customer preferences also seem to be largely predetermined and shaped by habit. Influencing or changing these habits will be critical to encouraging healthier choices and improving overall health outcomes, and more intensive marketing would be required.

Looking towards the future, if standards for balanced meals are widely disseminated in all types of outlets, consumers would routinely have access to easily recognizable and salient healthy meal options away from home. A standardized meal could be branded with an easily recognizable symbol that could increase consumers’ confidence that the meal they purchase is indeed a wise choice. This symbol would facilitate recommendations by health-care providers to patients to choose these meals whether or not they have a chronic disease, which in turn would support sustainable change. A companion marketing campaign to promote these balanced meals could enhance dissemination and uptake.

Implications for research and practice

Future research in this area should focus on ways to make healthy foods more appealing and also find a way to make unhealthy items, like sugar-sweetened beverages, less appealing in order to shift consumer preferences. Our pilot study suggests that food trucks mainly rely on the convenience of their location and returning customers, rather than other types of marketing. Although we created Yelp pages for the loncheras, the owners and their clientele were relatively limited in their capacity to use social media and many customers for traditional loncheras may not be reached in that way (v. more upscale food trucks). That trend is likely to change over time.

In practice, it seems that any food outlet should be able to offer at least one choice that complies with the My Plate criteria. Realistically, however, before adopting a new approach, most outlets will need to be convinced that their efforts will not be in vain and that customers will actually order these items. In other words, they need to see a return on any investment they make. Therefore, having materials that have been pre-tested for effectiveness with regard to meal preparation and marketing will be essential.

Considering the low rate of voluntary enrolment and lack of response to the mailing, an alternative is for local jurisdictions to consider adopting a requirement that all food outlets have at least one healthy option available. The burden from this type of requirement is minimal compared with the rigorous sanitary standards to which loncheras and all other licensed food establishments must adhere. In the same way that consumers should not have to worry about getting food-borne diseases when they dine out, they should not have to worry about increasing their risk of chronic diseases. Measuring cups and scales can be readily used even by food providers with a limited education to promote healthier eating habits among consumers.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This project was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; grant number R21HL114112). The NHLBI had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: D.A.C. was the principal investigator and developed the study design, analysed data and took the lead in authorship; B.C. and M.M.-W. developed survey materials and assisted with recruitment and implementation, measurement of adherence, data analysis and manuscript preparation; M.M. trained the lonchera owners and helped redesign meals; B.H. and S.H.B. assisted in questionnaire development, data analysis and manuscript preparation. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from lonchera owners.