The WHO(1) estimates that 39 % of adults worldwide are overweight and 13 % obese, leading to a range of health complications with associated health costs that strain the public purse. Without adopting effective measures to stop the escalating trend, estimates suggest that by 2030, obesity will affect more than 1·3 billion people, producing a significantly increased disease burden from CVD, diabetes and cancer. This will lead to a substantial increase in mortality particularly among adults in low- and middle-income countries undergoing rapid urbanisation and nutrition transition(Reference Yusuf, Rangarajan and Teo2–Reference Lopez, Mathers and Ezzati6). South Africa, a middle-income country with serious inequality, faces a severe and growing obesity epidemic. Between 2003 and 2012, the prevalence of obesity among women grew from 27·4 % to 39·2 % and from 7·5 % to 10·6 % among men(Reference Shisana, Labadarios and Rehle7). A national study conducted in 2016 found that two-thirds (68 %) of women and just under one-third of men (31 %) are overweight or obese(8).

The distribution of obesity and its association with socio-economic and behavioural factors has been widely studied in South Africa(Reference Malaza, Mossong and Bärnighausen9–Reference Micklesfield, Lambert and Hume13). Escalating obesity has occurred in conjunction with rapid urbanisation processes, including development of shopping malls and transport networks(Reference Igumbor, Sanders and Puoane14,Reference Battersby15) . Economic transitions have resulted in living environments, often referred to as ‘obesogenic’ environments(Reference Moodley, Christofides and Norris16) characterised by lack of facilities for physical activity, relentless marketing and sales of unhealthy foods and beverages(Reference Tugendhaft and Hofman17,Reference Stacey, van Walbeek and Maboshe18) . Readily available and affordable energy-dense processed foods, including sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), have become common place(Reference Igumbor, Sanders and Puoane14). Evidence shows that there is a link between living in an obesogenic environment and greater weight gain(Reference Mackenbach, Rutter and Compernolle19).

Previous studies also indicate that beyond the obesity-promoting environment, the clustering of socio-cultural factors can hinder individuals’ willingness to lose weight(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro20,Reference Puoane and Matoti-Mvalo21) , thereby increasing desirability to keep larger bodies. For instance, obesity prevalence in African communities is often discussed in relation to culturally embedded values around large body sizes that exemplify strength, beauty, sexual desirability, health, happiness, wealth, success and affluence(Reference Micklesfield, Lambert and Hume13,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke22) . Studies from rural and urban settings on body image and eating attitudes show that such values and desirability of bigger body weights(Reference Micklesfield, Lambert and Hume13,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro20,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke22,Reference Faber and Kruger23) are partly related to the two-decades long, HIV/AIDS epidemic that South Africans often associate with either being thin or losing weight(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro20,Reference Hurley, Coutsoudis and Giddy24) . People living with HIV (PLWHIV) have a desire to gain weight to fight stigma(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro20,Reference Puoane and Matoti-Mvalo21) .

Accurate perception of body weights is considered an important motivation for taking action and engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviours(Reference Baranowski, Cullen and Nicklas25). Yet, differences in perceptions of body size or weight, largely influenced by socio-cultural factors such as collectivist ideologies, norms and gender have the ability to influence weight preference(Reference Haynes, Kersbergen and Sutin26,Reference Baharudin and Omar27) . In South Africa, previous studies by Okop and colleagues(Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole28) showed that adults who were overweight considered themselves less vulnerable to disease (such as heart attack, stroke, diabetes and hypertension) than obese people and were therefore less willing to lose weight. In addition, Mchiza et al. examined the relationship between distorted body image and willingness to lose weight(Reference Mchiza, Parker and Makoae29). Findings revealed that half of the study participants had a largely distorted body image and were highly dissatisfied about their body size. Further, while more than half were overweight or obese, less than a quarter reported having attempted to lose weight.

In South Africa, limited information is available regarding the processes underpinning obesity normalisation. This study contributes to understanding of the socio-cultural norms relating to weight estimation among individuals living in rapidly urbanising setting with growing disposable incomes and increasing availability of inexpensive processed or fast-food.

Methods

Setting, design and participants

An obesogenic environment is defined as ‘the sum of influences that the surroundings, opportunities or conditions of life have on promoting obesity in individuals or populations’(Reference Lake30). We used this definition in selecting Soweto as the study site, which encompasses such a definition.

Soweto (south western townships) is a population dense (4143 people per km2), urban setting in the metro area of Johannesburg; 99 % of households have access to electricity and piped water, children have access to a large network of primary and secondary schools and communities have access to local clinics and the largest tertiary hospital on the African continent. Over the past decade, this area has also been transformed in terms of rising incomes and discretionary spending, intense marketing and advertising and availability of high-energy, processed food and sugary beverages(Reference Moodley, Christofides and Norris16).

This qualitative study was conducted in Diepkloof, which is one of the twenty-nine townships within Soweto and covers an area of approximately 9 km2 and houses a population of approximately 95 067 persons(31). Study participants were recruited using a purposive sampling approach from the Bara Taxi Rank in Soweto. We targeted the Taxi Rank as this is the main pickup and drop-off point for most residents of Soweto and facilitates an opportunity to obtain people from Diepkloof. Men and women aged 18 years and above were recruited to participate in the focus groups. Participants were excluded if they did not reside in Soweto, those who were mental or psychologically impaired and those who did not consent to participate in this study. Participants’ weight was not considered or measured during recruitment process. Of the eighty-five people approached, fifty-seven agreed to participate in the study. We conducted six focus group discussions (FGDs) using a semi-structured FGD guide from November to December 2017.

The group discussions that were facilitated by two multilingual research assistants were undertaken at the research centre at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital in Soweto. Two of these FGDs were conducted with middle-aged adult men and women (aged 36–55 years), two with adult men and women (aged 26–35 years) and two with younger adult men and women (aged 18–24 years). Gender and age were particularly important given that perceptions around overweight, obesity or being fat may vary across men and women of different age groups in South Africa(Reference Okop, Mukumbang and Mathole28,Reference Phillips, Comeau and Pisa32) .

Theoretical framework

The study is anchored to the concept of obesity normalisation process, a concept that is underpinned by the theory of ‘visual normalisation’. The former process refers to a shift in people’s perceptions of overweight or obesity from ‘unhealthy weight’ to what is regarded as ‘normal weights’. This may prevent individuals from recognising and attempting to regulate unhealthy adiposity in themselves and thus exacerbating the obesity problem(Reference Duncan, Wolin and Scharoun‐Lee33). Through the application of this theory, the study argues that (i) judgements about weight status are made relative to visual body weight norms and (ii) weight norms are shaped by the size of bodies a person is frequently exposed to in his or her environment(Reference Robinson34). Through recalibrating to the range of body sizes that are perceived as being ‘normal’, the visual threshold for what constitutes ‘overweight’ increases(Reference Robinson34).

Data collection

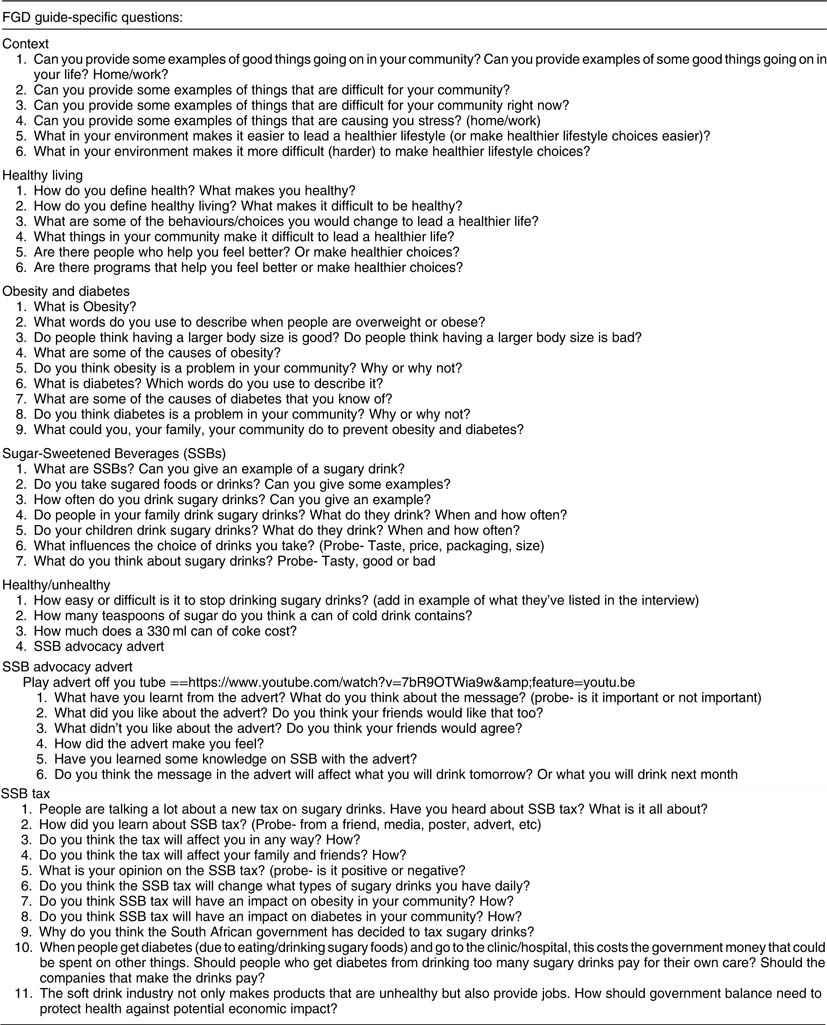

Each FGD was composed of 8–11 participants and were conducted in English and vernacular languages. Two multilingual Research Assistants facilitated the discussions using a semi-structured guide that reflected visual normalisation approach. The focus group discussions took 60–120 min to complete. Some of the questions that guided the discussion (see Appendix 1) were:

1. Describe your living environment

2. What do you or your family eat or drink most times of the week? What influences the choice of what you eat?

3. What is your understanding of overweight? Obesity?

4. What causes obesity?

5. What are your perceptions of different body weights?

6. Is obesity a problem in Soweto? If not why?

FGDs were audio recorded and complemented by field notes. Audio files from the discussions were transcribed verbatim with translation as needed. All transcripts were checked against the recordings to verify accuracy and credibility and changes were made where necessary.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were thematically analysed using a constant comparison method, which is an inductive data coding process consisting of categorising, comparing and contrasting data and summarising the content of each category for analysis purposes(Reference Boeije35). Data were categorised and compared across different gender and age groups. Thereafter, the data were analysed according to the six steps (data familiarisation through reading and re-reading transcripts and listening to the audio recordings, initial code generation, searching for themes, reviewing and naming themes, comparing themes across different categories and reporting). Initial code generation was done by two researchers involved in the study who repeatedly read the transcripts and field notes and categorised data into themes. Thereafter, the first three authors individually reviewed the themes and verified that the themes correlated with the data. The verification process was followed by the development of a codebook that was used for coding and analysis. We then used a constant comparison method between different groups to compare similarities and differences in the emerging themes. Intercoder reliability was checked in group meetings where the data were discussed and the themes verified.

Results

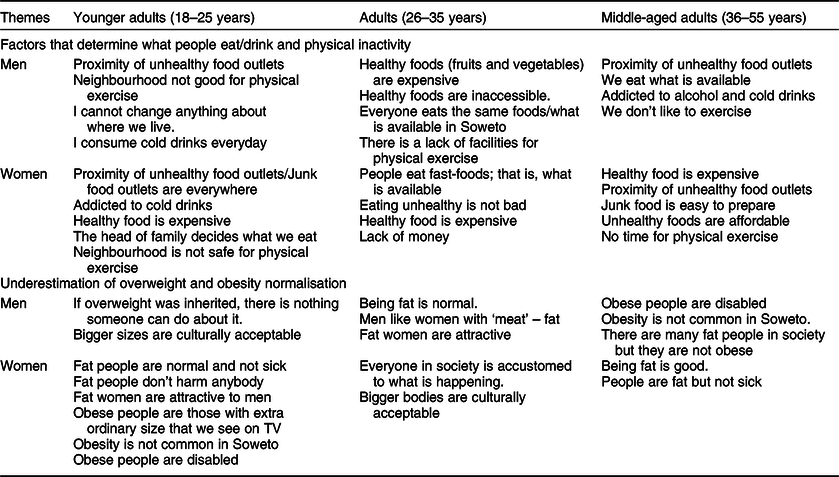

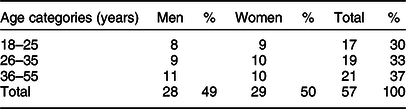

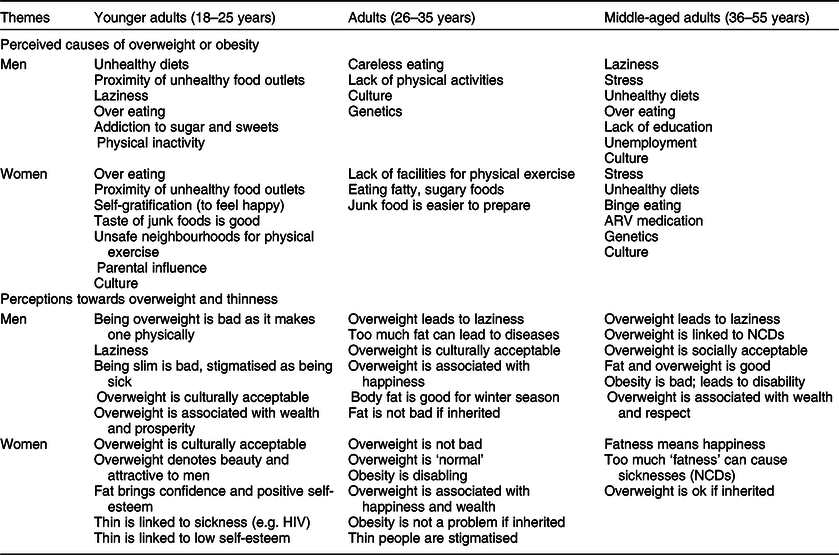

Of the fifty-seven (57) participants, approximately half (twenty-nine) were women. Participants ranged from 18 to 55 years (see Table 1). The five main themes that emerged from the study are (i) perceived causes of obesity; (ii) misperceptions about fat, overweight and obesity; (iii) socio-cultural norms towards overweight/obesity; (iv) obesogenic environment and obesity normalisation and (v) underestimation of weight and obesity normalisation.

Table 1 Participants socio-demographic characteristics

Perceived causes of obesity

Participants understood obesity to be a problem and somehow related to BMI, though they were vague as to the connection. They also felt that being obese meant being grossly overweight:

‘Obesity has something to do with your height and your BMI, but I don’t think its being fat’. (Women 18–25 years)

‘My thinking about obesity is letting yourself eat whatever you want to eat and don’t care how it affects you’. (Men 35–55 years)

Participants’ perceptions of the causes of obesity included factors both within and outside of their control.

Factors that could be controlled

Participants across all age groups linked obesity to eating unhealthy foods, their lifestyle and physical inactivity and all factors that were perceived to be controllable. However, eating unhealthy foods was seen to be a habit and addictive, difficult to change as it had become a routine in people’s lives:

‘I’ve got a daughter she is very fat, she doesn’t drink tea in the morning she drinks cold drinks it’s a must, when she eats, after eating it’s a cold drink. So, I think it’s one of the things and junk food she likes Kotas1’. (Women 26–35 years)

‘I also believe it is being addicted to sugar […] I bought like a 2 litre of Sprite not too long ago, what I noticed is, when I drink it, I crave for it more’. (Men 18–25 years)

Despite being aware of the dangers of unhealthy foods, both men and women participants across all age groups described consuming unhealthy foods as it made them happy or helped them feel relaxed. The consumption of unhealthy food was a common coping strategy, especially among women to living a stressful life or having a psychological disturbance:

‘I do what makes me happy, whether it’s eating junk food, […]. I go outside, I buy myself a KotaFootnote 1, cool drinks, packet of chips, I come into my room, eat, take a bath and sleep’. (Women 27–35 years)

‘I love my cold drink especially when I am stressed. It makes me feel better’. (Women 18–25 years)

Factors that could not be controlled

Participants also attributed obesity to natural factors such as hereditary or those born with genes for overweight and reported that they have little or no control over this:

‘I think it’s genetic, you inherit it from your grandmother, the fat and weight. The bones and everything, there is nothing you can do about it’. (Women 18–26 years)

‘Some of them [overweight people] are born with a big body and this is not their fault’. (Men 26–35 years)

Others associated obesity and overweight with other health conditions and treatment side effects such as taking anti-retroviral treatment (ART) for HIV/AIDS. Again, obesity or overweight was not seen as something that an individual has control over:

‘As I said earlier there are people I know, they are using their ARVs and their bodies are blowing up and getting fat. Sometimes they have this side effect of medication and cannot be blamed for being obese’. (Women 35–55 years)

Misperceptions about fat, overweight and obesity

Participants across all groups had a general misperception about who is fat, overweight or obese (see Table 2). Participants acknowledged that obesity was a condition or illness but being fat or overweight was perceived to be a normal state:

‘I think with obesity you are not able to come out from a mall without someone helping you, carry you, like at the age of 40, and you get heart disease […] It’s easy for you to get disease and you are always laying around [incapacitated]. I don’t see all this in Soweto’. (Women 18–25 years)

Table 2 Obesity causes and perceptions towards overweight and thinness

The perception of an obese person as a disabled person was commonly mentioned amongst middle-aged adult FGD participants. One discussant tried to differentiate between being fat, overweight or obese when he said:

‘There is a fat person, then there is someone who is overweight, he is not obese he is just overweight […] obese is someone who can’t walk properly, might need crutches or a system to walk or something. Then there is a fat person they can walk and all that stuff, but their body is not up to scratch. Then we have someone who is overweight, he might be like me, and has a stomach. You can say you are overweight, you are fat, but not obese’. (Men 36–55 years)

Defining obesity as a medical condition, as opposed to being fat or overweight that was perceived to be normal, was also reported in another FGD. A young male participant (18–25 years) believed that being fat or overweight was better than being obese:

‘I think obesity is kind of a chemical imbalance in your body that makes you fat more than other people, I’d say I’m fat, I’m not obese’.

Another participant in the same FGD seemed to have similar perceptions:

‘I agree with him, like fat and obese are two different things, basically obesity is fat on steroids, but fat is normal’.

Obesity was perceived as a disabling or a medical condition that participants have only seen on TV and other media channels. Participants viewed almost everyone as having a ‘normal weight’, and obesity was not seen as a problem in their communities:

‘Obesity is someone having a size 40 thigh, plus a size 40 thigh which makes it a size 80. And the people that we see on TV on the shows’. (Women 18–25 years)

‘I personally think it [obesity] is not a problem in Soweto, most people are just fat’. (Women 18–25 years)

Sociocultural norms associated with overweight

The current study revealed several socio-cultural norms that influenced individual’s desirability of bigger bodies. Both adult and young adult men and women reported that men valued women with bigger shape and size compared with the slim women:

‘Men like bigger women, I think it’s in all generations, but I could say what is happening with our generation specifically now, is the fact that they actually like big women’. (Women 18–26 years)

‘Basically, I’m sure we all know this, as black people, or rather, as black men, you know we like women with a bit of meat [fat]…’. (Men 26–35 years)

Fatness was perceived to be a symbol of beauty, confidence and happiness, especially among women of all age groups (see Table 2)

‘Men want women who are fat because they look beautiful and attractive’. (Women 27–35 years)

Bigger body size was also a symbol of vitality and good health and was perceived to be favourable or advantageous during winter:

‘It also depends on the time of year, we know that fat people have no problem with winter you know, they can go outside and not shiver or whatever, and they don’t get sick’. (Men 26–35 years)

Moreover, men and women positively attributed being overweight to wealth and affluence:

‘When you are fat, you are living well, you actually have money and you don’t have problems in your life’. (Men 18–25 years)

‘Overweight is associated with wealth. People will respect you because you are fat’. (Men 36–55 years)

‘Yes, around the community, […] like everything is going right in your life, once you buy a new car you are gaining weight, people would say ‘she’s going to be gaining weight’ because you have a new car’. (Women 26–35 years)

On the contrary, both men and women participants associated thinness with illness, especially with HIV/AIDS. Thus, to avoid stigmatisation, participants preferred to gain weight to be perceived healthy:

‘I grew up being thick [fat] like this, next week if I come back looking like her [pointing to a thinner member in the FGD], it’s like I’m sick or something. People are actually scared of like losing weight because they will say that they are sick, people will say you have HIV’. (Women 18–25 years)

‘I think another thing that makes people not want to lose weight is the thing of saying people are sick, people just generally think that you are sick because you have lost weight’. (Men 36–55 years)

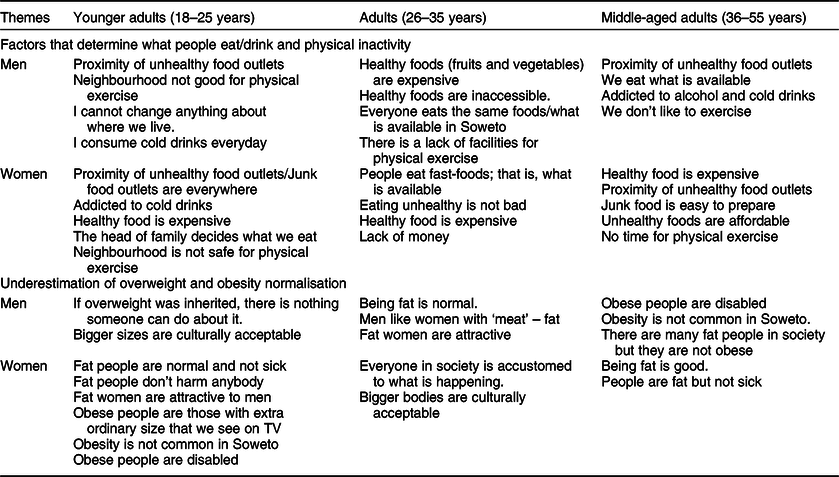

Obesogenic environments and obesity normalisation

Participants described a number of factors in their environment that they felt contributed to their unhealthy diet including the availability of cheap highly processed foods and cold drinks and the lack of affordable healthy option (see Table 3):

‘We are always surrounded by fast food shops. You know we do not have any other shops around us, you cannot find a fruit salad anywhere near us, you cannot find anything besides something that’s greasy and with fat […] That’s why we cannot live a healthy life’. (Men 26–35 years)

Table 3 Obesogenic environments and obesity normalisation

While some expressed willingness to change what they eat, others were fatalistic and believed that nothing could change the situation:

‘I believe it’s almost everyone because if you think about it, our age group in most cases we don’t work, we don’t have anything to do, we don’t go to gym, we consume a lot of alcohol, and then you get like the older generation, they, in most cases they have like a regime, where they basically drink every day, or they drink to sleep, basically it is what it is […] That’s our life’. (Women 26–35 years)

Although most participants reported that they were surrounded by unhealthy foods, few mentioned different stores or malls where healthy foods were sold. However, the high cost of healthy foods influenced them to eating unhealthy diets:

‘I still think we have places that sell healthy foods in Soweto […] the veggies and carrots but access to healthy foods is very much expensive, it’s unaffordable’. (Women 26–35 years)

‘They sell the healthy foods in the malls but basically the fried food that we eat, the Kotas and whatever, those are affordable than healthy foods’. (Women 18–25 years)

‘Not working is stressful, because I don’t want to be where I’m at in life. I get sick because of what I eat, its unhealthy food. But what can I do? I would like to eat healthy foods, but I can’t afford it’. (Men 26–35 years)

Participants cited challenges related to engaging in physical exercise in Soweto such as lack of facilities to exercise and insecurity that barred people from jogging within the neighbourhood:

‘We don’t have facilities for physical exercise. In Soweto there are some parks but people will vandalise and take anything installed there’. (Men 26–35 years)

‘In Soweto when you wake up in the morning going for a jog some guy is going to come snatch your phone or you’re going to get people who will take you away to go and rape you in the bushes. Unsafe environments are a challenge for us to exercise’. (Women 18–25 years)

Underestimation of weight and obesity normalisation

Participants, especially middle-aged adults, perceived their weights to be normal, despite understanding they were fat or overweight. This perception was also reflected towards their friends or family members:

‘My daughter drinks two cans of cold drinks in a day. She is fat but not obese, she does not have obesity […] I know that because she is not sick’. (Women 36–55 years)

‘I have always been like this [fat] since I was a child. My body has never been thin, I was born fat and I am ok. You will see most people being fat but they are not sick. They don’t have obesity’. (Men 36–55 years)

Discussion

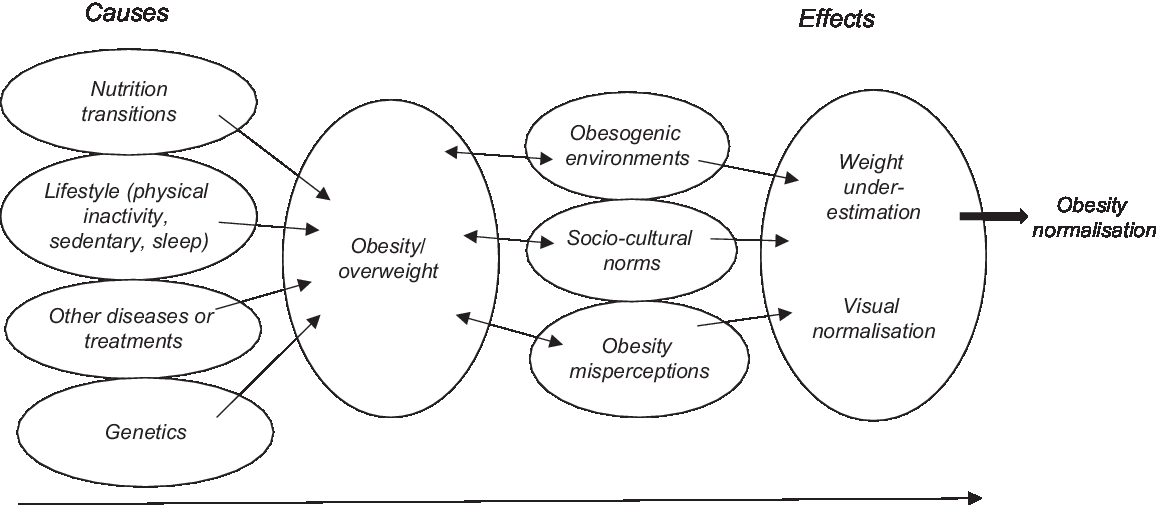

Several studies in South Africa have elucidated factors associated with obesity(Reference Shisana, Labadarios and Rehle7,Reference Malaza, Mossong and Bärnighausen9,Reference Igumbor, Sanders and Puoane14,Reference Prioreschi, Wrottesley and Cohen36,Reference Steyn and Mchiza37) , including a systematic review that provided evidence on how obesogenic environments influence weight gain(Reference Mackenbach, Rutter and Compernolle19). The current study extends our understanding on how unchanging socio-cultural factors that reinforce the acceptability of bigger bodies interact with living in obesogenic environment, where people have no choice but to eat unhealthy foods that are easily available, accessible and affordable. As a result, people get overexposed to bigger bodies in their daily lives and this creates a distorted perceptions of normal body weight, leading to obesity normalisation.

In line with other analyses that have established a traditional desirability of bigger body weights in South Africa(Reference Micklesfield, Lambert and Hume13,Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro20,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke22,Reference Faber and Kruger23) , the current study confirms unchanging socio-cultural norms in relation to bigger body weights, reflecting how such norms continue to influence desirability and normalisation of bigger bodies. For example, both men and women reported that they preferred bigger bodies: males linked bigger bodies to wealth and affluence while females associated bigger bodies to beauty, happiness and confidence. Most females strove towards gaining more weight to achieve a desirable shape or ‘ideal body’ (and were reluctant to lose weight). This finding parallels what has been reported previously in both rural and urban communities of South Africa(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro20,Reference Faber and Kruger23) and in Nigeria(Reference Akarolo-Anthony, Willett and Spiegelman38). This could partly explain and support other findings on why more women than men are overweight or obese in South Africa(Reference Case and Menendez39). In addition, the stigma attached to thinness, linking it to diseases such as HIV/AIDS, poses negative influences on risk perceptions of being fat or overweight(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro20,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke22,Reference Faber and Kruger23) and a desire to gain weight to avoid such stigma(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro20,Reference Puoane and Matoti-Mvalo21) .

Furthermore, the immediate food environment was reported to be determinant of participants’ unhealthy eating habits, a finding that is consistent with previous evidence regarding the influence of poor urban obesogenic environment(Reference Hall, Richter and Mokomane40) on individuals’ food choices and physical activities(Reference Michimi and Wimberly41). Study participants reported a high density of fast-food outlets in their surroundings, selling affordable but poor quality food. Affordability and convenience are especially significant factors in dietary choices, thus some participants mentioned eating unhealthy foods because that is what they could afford. This is critical given that poverty is on the rise in South Africa(42), and national unemployment in 2017 was 27·7 %.(43) In addition, lack of facilities for physical activities together with crime and insecurity in Soweto is a barrier to engaging in physical exercise(42). This finding reflects the rapid urbanisation processes in Soweto, including the construction of shopping malls, improved transport systems yet persistently high inequality(Reference Mayosi, Flischer and Lalloo44). Fast-food outlets, small shops and restaurants play an important role in day-to-day provisioning among the urban poor in Johannesburg(Reference Rudolph, Kroll and Ruysenaar45), with 55 % of households sourcing food from these outlets at least once a week or more often, especially in the inner city. Interestingly, in lower- to middle-income and predominantly black communities (a hold over since 1994 of spatial apartheid), fast-food outlets are typically more available than they are in high-income and white communities in urban areas(Reference Michimi and Wimberly41); a pattern that has been observed in the UK, where fast-food outlets cluster in areas of deprivation(Reference Townshend and Lake46).

Findings of the current study also showed general misconceptions of being fat or overweight amongst black Africans in Soweto. These states were perceived to be ‘normal’ when compared with obesity which was seen to be a debilitating or disabling condition. This illustrates that most people were aware of obesity but perceived it more in terms of morbid obesity or extremes of fatness. Prior studies amongst South Africans have linked poor perception of the risk of being obese to insufficient knowledge of obesity(Reference Puoane, Fourie and Shapiro20,Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke22,Reference Faber and Kruger23) , as well as the lack of access to appropriate related health information in relation to obesity(Reference Micklesfield, Lambert and Hume47).

In support of the visual normalisation theory(Reference Robinson34,Reference Oldham and Robinson48) , our findings indicate that regular visual exposure to bigger bodies (partly due to unchanging socio-cultural factors that reinforce the acceptability of bigger bodies, interacting with living in obesogenic environment) plays a role in the poor detection and consequent underestimation of body weight. This could explain why participants perceived being fat to be ‘normal’ without understanding its dangers and that what they perceive to be ‘fat’ might well be obese. Our findings are in line with findings from other studies that explored the impact of living in an obesogenic environment on individuals’ weight perceptions(Reference Robinson34). In his systematic review, Robinson showed that exposure to obesity influenced perceptions of what constitutes a ‘normal’ body weight and resulted in participants being less likely to judge an overweight person as being an unhealthy weight(Reference Robinson, Haynes and Sutin49). Additionally, studies have also shown that being exposed to parents and/or peers of heavier body weight could be associated with a greater likelihood that children or adolescents fail to accurately self-identify as overweight(Reference Maximova, McGrath and Barnett50,Reference Ali, Amialchuk and Renna51) .

Consequently, individuals will not seek a solution (weight control) if they do not recognise that the problem (overweight) exists(Reference Lemon, Rosal and Zapka52–Reference Duncan, Wolin and Scharoun‐Lee54). Thus, participant’s normalising fatness or overweight and their perception of illness or disease confirms how most NCDs such as hypertension are ‘silent disease’ that develop over time, with individuals often being unaware of its presence. This highlights the importance of addressing weight perception as part of any lifestyle or behaviour change intervention that targets a similar population. It also points to using language about being overweight that individuals understand when promoting healthy eating and healthy lifestyles.

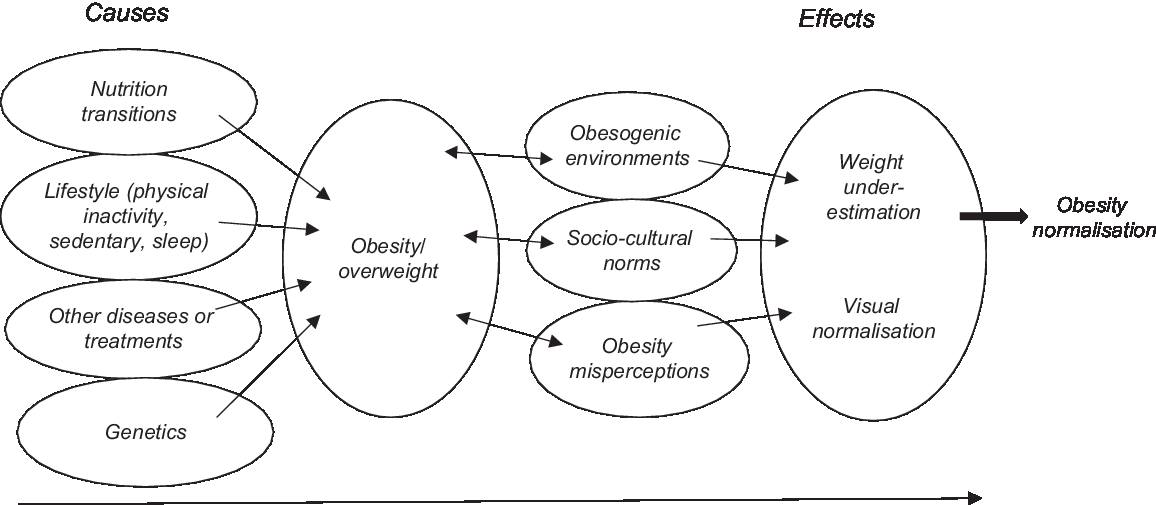

With a significant increase in the obesity epidemic in South Africa between 2003 and 2016 (27·4 %–68 % for women and 7·5 %–31 % among men)(8), it should be noted that visual normalisation of overweight presents a challenge. These results show that both acceptance of fat and bigger bodies as the norm while living in an obesogenic environment, such as Soweto where people have no choice but to eat unhealthy foods that are easily available, accessible and affordable are key factors in obesity normalisation (see Fig. 1). The tendency of individuals who are overexposed to bigger bodies in their daily lives creates distorted perceptions of normal body weight. It appears that as obesity becomes more prevalent, people may continue to underestimate their weight status(Reference Robinson34). The unrealistic perception of being fat or overweight could impact the intention to lose weight or seek healthcare timeously. Because many diseases are ‘silent’ until years later, this is also likely to lead to an increase in the number of persons with undiagnosed obesity-related NCDs, which culminate in disability and premature death.

Fig. 1 Pathways to obesity normalisation

Research and policy implications

There is a need for public health practitioners to improve the public’s understanding of the risk associated with being overweight or fat. Simultaneously, it is imperative to consider the language of communication when talking about overweight or obesity to people, particularly to those who live in obesogenic environments. It could be that people’s understanding of fat or overweight may not necessarily represent the precise clinical terminology used to determine nutritional status. This gap may undermine interventions aimed at decreasing obesity or an individuals’ motivation to reduce weight(Reference Lemon, Rosal and Zapka52). Thus, simple and easy to understand messages dealing with cultural issues and the risk of being overweight should be conveyed using sensitive language.

Given the unchanging social norms and perceptions towards bigger body size and weight in South Africa, appropriate and context-specific strategies to improve awareness of the health risk of bigger body sizes or overweight are critical. Community-based wellness events, health promotion and physical activity programmes should be organised and conducted to motivate community members to maintain healthy body sizes. However, approaches to changing social norms need to be developed thoughtfully to avoid the possibility of stigma or victimisation, and where emotionally vulnerable individuals may respond by developing an eating disorder, such as anorexia.

To avoid blaming the individual, urgent action is critical to mitigate the adverse effects of the rapidly changing food environment in South Africa(Reference Ndlovu, Sartorius and Hofman55). Efforts should be made to better understand the various factors that influence the choices people make in acquiring and consuming food in Soweto (such as affordability and convenience) and to ensure healthy foods are made more affordable, accessible and available to all citizens. In addition, there is need for policy interventions that limit the number of fast-food outlets in communities together with restricted marketing and advertisements of unhealthy foods. Other relevant policies for consideration include mandatory transparent front of pack warning labels, as has been implemented in Chile(Reference Reyes, Garmendia and Olivares56) and subsidising healthy foods. The idea of increasing the cost of unhealthy food in South Africa has already been implemented with Health Promotion Levy (a sugary beverage tax) legislated in 2018(57–Reference Bosire, Stacey and Mukoma59). All these policies can assist in reversing the environmental drivers of obesity in South Africa. However, without formal structures and a broad array of mandatory legislation and regulation similar to those used to quell the tobacco epidemic, the food and beverage industry will continue to shape and manipulate the polices, and the negative trajectory of fast-food expansion will continue to result in collateral health damage(Reference Bosire, Stacey and Mukoma59).

The current study is not without limitations. We interviewed a sample of people from the Taxi Rank in Diepkloof area in Soweto close to the Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic hospital, so these findings may not reflect general perceptions on overweight, obesity and different body images in South Africa. However, it is not the aim for qualitative research to have representative samples or producing generalisable findings. Instead, the intention is to generate an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon and explore ‘transferability’ to other contexts(Reference Gostin60). Further, some participants admitted that they were fat or overweight. However, we did not confirm participants’ weight or calculate their BMI, but relied on participant’s own explanations, perceptions and views on their weight status as well as for others.

Conclusion

South Africa’s obesity problem will unlikely be resolved without urgent multi-sectoral actions that address the current obesogenic food environments. Our research demonstrates the critical need to shift social norms. One way to do so is to focus efforts on modifying weight misperceptions, in particular that being overweight is healthy. The current study shows the need to create appropriate, context-specific messages, for example, that could begin early during the education cycle and is prioritised on an annual basis. A new, more accurate narrative can drive community buy-in and could potentially shift attitudes and opinions. The health promotion levy is one such instrument because individuals begin to question why the price of a sugary beverage is being increased. Other strategies could include regulations to display calories on fast-food menus, explicit and transparent front-of-pack warning labels and promotion of healthy options in fast-food restaurants.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank all of those who participated in the current study; their sincerity in sharing their perceptions towards overweight and obesity and their thoughts about different body weights were fundamental to the success of the current study. The South African DST/NRF Centre of Excellence in Human development at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, supports Emmanuel Cohen and Shane Norris. Financial support: This research was supported by the SA MRC Grant D1305910-03. SA MRC did not have any role in analysis, interpretation, writing of manuscript or decision to publish. E.N.B. is supported by the South African Medical Research Council. Conflicts of interest: The authors declare there is no conflict of interest. Authorship: E.N.B. collected, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript; E.C. collected, analysed data and contributed in manuscript development; A.E. analysed data and contributed in manuscript development, S.J.G. commented on the manuscript, K.J.H. and S.A.N. conceptualised the study and commented on the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Human and Ethics Research Committee (HREC) of University of the Witwatersrand (M170680). Written informed consent was obtained from the study participants after reading out the content of the information sheet and explaining the purpose of the study.

Appendix 1 Interviewing guide