1. Introduction

Digital games and the networks of social activity related to them continue to draw the attention of educational scholars and practitioners. Game-enhanced approaches to foreign- and second-language (L2) teaching explore ways to leverage commercial, entertainment-purposed games for formal instruction (Sykes & Reinhardt, Reference Sykes and Reinhardt2013). Instructional activities using games offer possibilities for language study and practice. However, gaming spaces are also social ecologies, with groups of users creating and reifying particular goals and ways to pursue them, giving rise to localized cultures-of-use (Thorne, Reference Thorne2016). Although gaming spaces offer unique ways to engage in, and be socialized into, social and linguistic practices and identities that may extend beyond those in the classroom (Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2019), students may not always have access to them (Pasfield-Neofitou, Reference Pasfield-Neofitou2011; Rama, Black, van Es & Warschauer, Reference Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012).

Recent studies have presented results from pedagogical designs aimed at helping students explore social aspects of social media by focusing learner attention on situated uses of language in the performance of gaming and social-networking practices (Blattner & Fiori, Reference Blattner and Fiori2011; Reinhardt & Ryu, Reference Reinhardt and Ryu2013; Reinhardt, Warner & Lange Reference Reinhardt, Warner, Lange, Guikema and Williams2014; Reinhardt & Zander, Reference Reinhardt and Zander2011). This research, however, is still in its infancy and limited in a number of ways. In addition to being few in number, there have been mixed findings from studies focused specifically on L2 teaching with digital games. Using gaming spaces in instruction and creating tasks to analyze gaming discourses has the potential to support language awareness – an understanding of how language works as a social medium (Thorne & Reinhardt, Reference Thorne and Reinhardt2008). However, some students have resisted pedagogies employing guided analysis of game-related discourses. Better understanding of how instruction designed around gameplay supports language awareness is important as L2 educators continue to conceptualize and teach language related to literacy practices (Street & Leung, Reference Street, Leung, Hornberger and McKay2010). Another main limitation is the lack of information regarding student participation in the social media spaces they explore for instruction. Using language within gaming spaces in appropriate ways to coordinate activity and to create and maintain relationships is critical not only for the development of communicative linguistic resources but also for socialization, affiliation, and L2 identity formation (Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019). Yet it is largely unknown whether or not students participate in the social media spaces they analyze as part of instruction, why they do or do not, and what happens when they choose to participate.

The current study attempted to address these gaps in the literature. Pedagogical activities were created around digital gameplay to enhance awareness of the relationships between language use and social contexts and to present possibilities for L2 socialization. The aim of the study was to contribute new insights into the instructional uses of digital games in L2 education by illuminating some of the strengths and weaknesses of a model of game-enhanced instruction and to identify issues related to student participation in gaming spaces.

2. Theoretical background and literature review

2.1 Digital gaming as a social practice

A number of recent views on technology and language conceptualize them as tools inseparable from their social and cultural purposes. Technologies and language are coordinated to actualize human activities, serving as instruments to carry out social meanings, routines, and associated identities (Gee, Reference Gee2008). As culturally imbued tools, technologies carry “interactional and relational associations, preferred uses (and correspondingly dispreferred uses), and expectations of genre- and register-specific communicative activity” (Thorne, Reference Thorne2016: 185). In this view, digital games, and the linguistic activity tied to them, are far from value-free tools but are bound instead to cultures-of-use (Thorne, Reference Thorne2016). Failing to perform in ways that resemble the established norms, values, and communicative activities within online spaces can lead to unwelcoming encounters (Hanna & de Nooy, Reference Hanna and de Nooy2003). Therefore, for teachers seeking to tap the social possibilities digital gaming presents, gaming spaces need to be conceptualized as places to not only practice a language but also to participate in language (and other) practices.

Coming to know cultural patterns of activity is a matter of access to and extended participation in them (Lave & Wenger, Reference Lave and Wenger1991). Language socialization describes the process of newcomers to a group or community becoming legitimate participants in socially relevant communicative activities (Duff & Talmy, Reference Duff, Talmy and Atkinson2011). Joint collaborations between newcomers and more knowledgeable others within the group are therefore vital sources for learning, with learning being understood as changes in participation and identity.

2.2 Participating in gaming ecologies and socialization potential

Digital gaming ecologies encompass different mechanisms for learning cultural practices. Steinkuehler (Reference Steinkuehler, Kafai, Sandoval, Enyedy, Nixon and Herrera2004) presented an example of a more skillful player socializing a newcomer into a social practice within a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORG). The experienced player modeled competent performance, pointed out relevant aspects critical for success, offered feedback, and handed over increasing levels of control to the newcomer. While Steinkuehler uncovered socialization processes at work during gameplay itself, Ryu’s (Reference Ryu2013) study shows that game-related websites can also afford socialization opportunities. Examining data from non-native English speaking players, Ryu found that shared gaming interests and multiple roles on a gaming website, among other factors, helped create opportunities for these gamers to collaborate and interact with other users. The L2 gamers received help from more experienced players, exchanged information and strategies, and imitated language and cultural practices. These studies suggest that attempting to participate in discourse practices within gaming ecologies offers socialization possibilities.

Other studies, however, show that members of gaming communities may not always be willing to engage in joint collaboration to socialize newcomers. For instance, Steinkuehler (Reference Steinkuehler2006) explained how she was viewed and labeled as a “newbie” in a gaming community for not displaying community norms and values. Additionally, Pasfield-Neofitou (Reference Pasfield-Neofitou2011) found that members on a game-related website did not always welcome outsiders who were not able to perform specific (Japanese) identities and failed to synchronize their language practices with those of the community. Moreover, Rama et al. (Reference Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012) described how the socialization affordances within an online multiplayer game differed for two learners at different L2 proficiency and gaming levels. Considered together, this research suggests that socialization opportunities differ in regard to the localized forms of knowledge one displays.

2.3 Literacies instruction: Developing language awareness to support access to practices

Formal instruction can also serve as access to social practices. Literacies instruction focuses on access by linking social uses of language in specific contexts with predictable patterns of expression (Street & Leung, Reference Street, Leung, Hornberger and McKay2010). A literacies perspective conceptualizes language not as an abstract system of rules, but rather a social medium that considers “language and cultural awareness to be indistinguishable” (Bolitho, Carter, Hughes, Ivanič, Masuhara & Tomlinson, Reference Bolitho, Carter, Hughes, Ivanič, Masuhara and Tomlinson2003: 253). Thus instructional approaches from a literacies perspective pay particular attention to language and other semiotic resources in the performance of recognizable activities and identities.

Educators have used different instructional approaches to develop literacies. One approach includes engaging students in observational and analytical activities that focus on language use in social-networking sites. For instance, Blattner and Fiori (Reference Blattner and Fiori2011) asked students to observe various Facebook groups and contrast the language use they observed with the rules and examples from their textbooks. The researchers reported that students responded positively to the activities and developed dimensions of language awareness. Another instructional approach has aimed at simulating specific literacy practices. Mills (Reference Mills2011), for example, used a social-networking site with the students in her French language course and asked them to take on fictional but culturally grounded identities. Throughout the course, the students interacted together on the site using the identities they created. Mills found that the students created their own community of practice by pursuing common interests, exploring these interests together, and sharing resources. In a study on gaming, Steinkuehler and King (Reference Steinkuehler and King2009) created a private online community for an after-school program serving at-risk adolescent males interested in gaming. The community was designed to act as an “incubator” for the literacy activities that are critical for advanced gameplay. In the program, students and teaching volunteers gamed together online, discussed information on a secured forum, and completed structured activities such as working on a group website and writing fan fiction. Steinkuehler and King found that the program has the potential to afford access to the dispositions, skills, and knowledge that the students will need to gain membership in gaming communities that exist outside the private community they created. Although these studies highlight the power of instruction in becoming more aware of context-specific practices, they do not examine how instruction supports student participation in the online spaces they explore. Also, Steinkuehler and King (Reference Steinkuehler and King2009), similar to Zheng, Newgarden and Young’s (Reference Zheng, Newgarden and Young2012) study on teachers leading L2 students through gaming worlds, do not offer details about the pedagogical activities that may have been utilized to direct student attention to the ways language is used to perform gaming practices.

Observation, linguistic analysis, and participation in discourse practices are core components of Thorne and Reinhardt’s (Reference Thorne and Reinhardt2008) bridging activities (BA) framework. In BAs, students participate in, reflect upon, and create situated meanings across contexts with the help of the teacher. In doing so, the framework aims to develop students’ language awareness. Language awareness is conceptualized in two ways. First, it is seen as a disposition that includes understanding and articulating patterns of language in use, and second, as a pedagogical approach that emphasizes the awareness of “the relationships between features of the texts, the social contexts in which they function (genre), and the social realities specific language choices will tend to instantiate” (Thorne & Reinhardt, Reference Thorne and Reinhardt2008: 563).

The BA framework has been used in multiple studies to guide the creation of instructional activities using social media (e.g. Chen, Reference Chen2019; Sauro & Sundmark, Reference Sauro and Sundmark2019). For instance, Reinhardt and Ryu (Reference Reinhardt and Ryu2013) employed the BA framework to help American university students understand how Korean speakers linguistically negotiate their audience and relationships on Facebook. Classroom activities included analyses of teacher-selected Facebook postings and simulated Facebook interactions. Reinhardt and Ryu found that the activities supported language awareness and were well received by the students.

The BA framework has also been used to structure game-enhanced instruction. Reinhardt and Zander (Reference Reinhardt and Zander2011) introduced digital gaming as a tool to foster language awareness and L2 socialization and investigated how different discourses interacted with the designed pedagogy. Students completed social media activities over a two-week period, including some that focused specifically on digital gaming. In groups, they played online games during two lab sessions and a weekend. Afterwards, students presented evaluations of the games. Reinhardt and Zander found that students reported learning domain-specific vocabulary and that the gaming sessions provided opportunities for relationship building among classmates. They also found that some students resisted the game-enhanced pedagogy because they valued teacher-centered pedagogies and felt that the vernacular forms used in gaming spaces did not prepare them for the high-stakes tests they needed to take. This study shows that students may not always see games as educational resources. Additionally, the gaming sessions in the study were short in duration, presenting limited opportunities for socialization.

Reinhardt et al. (Reference Reinhardt, Warner, Lange, Guikema and Williams2014) also reported mixed results after implementing a gaming unit in a German L2 university course. The gaming unit was two weeks long. Gameplay consisted of four 20-minute sessions per week and the completion of a reflection. Reinhardt et al. found that about half of the class enjoyed the gaming unit and felt that it was useful for learning German, whereas the other half expressed frustrations with learning how to play the games. There were also problems with viewing games as educational resources, confirming Reinhardt and Zander’s (Reference Reinhardt and Zander2011) earlier finding. Furthermore, the students reported a dislike for the reflection and perceived a gap between the gaming unit and the rest of the course. Similar to Reinhardt and Zander, this study was short in duration, which may explain why some students experienced frustrations in learning how to play the game. Additionally, the study did not investigate the extent to which students directly participated in the practices of actual gaming communities. Thus the socialization affordances of the instruction are not clear.

Cultures-of-use (Thorne, Reference Thorne2016) reminds us that online games are social spaces. However, as the this review of the literature shows, there have been very few reports on pedagogies targeting social practices within social media in general, and even fewer on game-enhanced instruction in particular. To better understand how instructional uses of digital games may or may not support language awareness and possibilities for L2 socialization, the current study aimed to answer the following questions:

1. Do students who engage in the game-enhanced pedagogy exhibit language awareness and participate in gaming discourses?

2. What supportive or impeding language awareness and gaming participation phenomena emerge from the implementation of the game-enhanced pedagogy?

3. Methods

3.1 Participants

The participants were 16 undergraduate students enrolled in an introductory educational technology course at a women’s university in Seoul, South Korea. All of the students were Korean females, between the ages of 18 and 23, and had studied English for an average of nine years. They were also applied linguistics majors, most of whom (n = 13) were in their first or second year of study. There were no official measures of English proficiency, but all of the courses within the applied linguistics major are carried out in English, meaning that these students can participate in class discussions and write assignments in English. In regard to online digital gaming experience, 13 of the 16 students reported on a pre-course survey that they were not playing digital games when the course began. Another student stated that she played online games for 1–2 hours per week but did not consider herself a gamer. There were two students who regularly gamed for more than 5 hours on a weekly basis.

The course, multimedia English, is an elective, lower-level course within the applied linguistics major. The course is 15 weeks long, and classes meet twice per week for an hour-and-a-half per meeting. The first half of the semester focuses on multimedia literacy skills – capturing, editing, and producing texts, pictures, and videos – and an introduction to communicative language teaching. The second half introduces lesson planning and language objectives, including specific speech acts, or language functions (e.g. giving instructions), and language skills.

3.2 Pedagogical procedures and materials

Digital gaming was introduced to students as a way to be exposed to and learn new varieties of language, develop technology skills, think about games as potential language learning resources, as well as possibly meet and communicate with others while playing a fun game. While digital gaming was being introduced to the class, references were made to studies that have found that extramural gameplay can facilitate English language learning (e.g. Hannibal Jensen, Reference Hannibal Jensen2019; Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2019). Also, as a homework assignment, students were asked to listen to a podcast (Sykes & Reinhardt, Reference Sykes and Reinhardt2010), identify the reasons why the speakers believe digital gaming supports language learning, and then write a response about whether or not they agree with them. After the introduction, students were first instructed to select an online digital game with an active associated site (e.g. strategy site). Two graduate students who were enrolled in courses on sociolinguistics and digital gaming taught by the researcher volunteered to assist in the implementation of the gaming pedagogy. These two volunteers and the researcher/instructor worked together to create a list of possible online games for the students. The list included games that were free, could be played on mobile devices, and had active associated online spaces. Game-associated sites are not only potential spaces for socialization, but are also important sources to learn about the mechanics of gameplay. The list was posted to a course wiki, and the instructor and teaching volunteers went through the list with the students to present potential games and demonstrated ways for students to find sites associated with digital games. Over the next two weeks, students explored possible games before deciding on one to play. The digital games that were chosen are shown in Table 1. Students were then asked to play the game they chose for at least 45 minutes a week and visit sites associated with it. Post-course data showed that student gameplay sessions were more than one-and-a-half hours per week on average.

Table 1. The digital games selected, number of students who played them, and game genres

A gaming journal (see Appendix A) was then introduced to carry out the game-enhanced activities for 11 weeks. The gaming journal was hosted on the course wiki and individual journals were made for each student. The journal reflected the three-phase BA framework: (1) observing and collecting texts, (2) guided exploration and analysis, and (3) creation and participation.

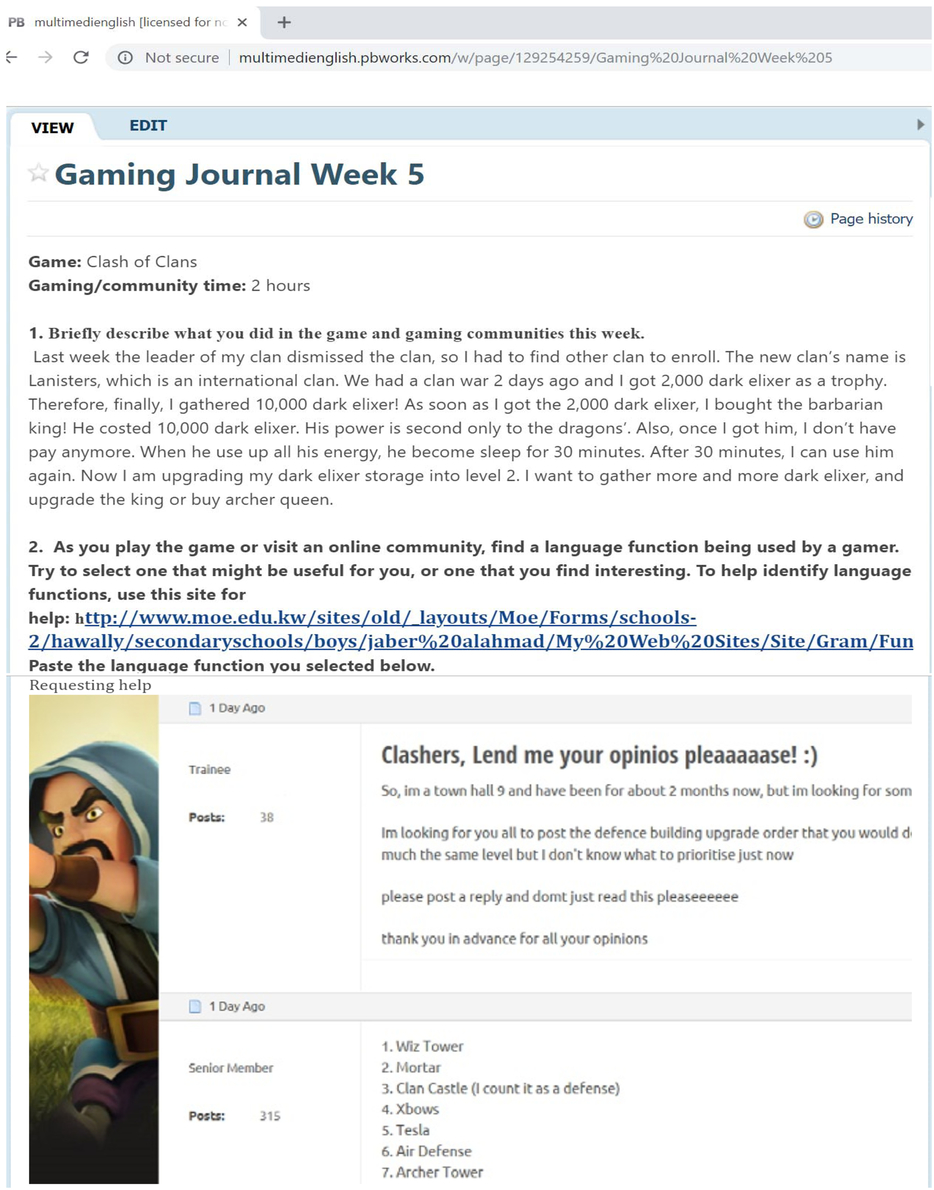

Students observed and collected texts during gameplay or when visiting gaming sites. Students were asked to capture examples of language functions used in interactions between gamers and paste them into their gaming journals so that they could analyze them later. A language function “is understood in terms of the relationship between meaning and linguistic form. … [W]hat people mean to say is realized by the specific linguistic means and features they select to manifest their meanings” (Street & Leung, Reference Street, Leung, Hornberger and McKay2010: 298). In order to assist students in identifying the function in the interactions they had captured, a link to a website was added to the journal. The website illustrated various language functions and informal and formal linguistic forms to perform them.

The aim of the guided exploration and analysis instructional activities was to illuminate relationships of language choice and social context. Beyond providing information, language is used to show affiliation and to create and maintain interpersonal relationships. These aspects were targeted in the pedagogical analysis activity by prompting students to consider, for example, the addressee(s), the speaker, the key, the channel of communication, as well as to explain why the gamer said what she or he said in that way. Focusing on what people commonly mean to say in a particular gaming space, and how, was viewed as a way to provide potential access for student participation in the gaming discourses they explored. Thus observations and instructional analyses offered models of competent (or incompetent) local participation (Gee, Reference Gee2008).

The instructor and teaching volunteers offered guidance in the activities within this BA phase and others. Each week they read gaming journals and provided comments. The comments attempted to prompt students to further consider their observations, point out important aspects of language in use that they did not mention, and to search the gaming space for evidence to support or refute the language hypotheses they made.

For the creation and participation component of the gaming journal, students were offered two options. One option consisted of simulating how they would perform the language function they previously analyzed if they were in the same situation as the speaker. The other option was to paste into their journal their actual performance of functions within gaming spaces. Considering the possible negative experiences associated with performing in locally inappropriate ways (Hanna & de Nooy, Reference Hanna and de Nooy2003), direct participation in gaming discourses was not required. Also, previous studies (e.g. Mills, Reference Mills2011; van Compernolle, Reference van Compernolle2014) have shown that simulated scenarios can prompt student thinking about social context–form relationships. Reflection questions followed, asking students to consider the reasons why they used the forms they did. A final journal prompt asked students how their simulated or actual actions would differ if they were performed in a different setting. The use of comparisons in the journal reflected Gee’s (Reference Gee2008) assertion that in order to develop an awareness of social languages, comparisons between participatory settings are a cognitive necessity.

3.3 Data sources and data analysis

There were two data sources used in the study. The first source of data was the gaming journal. As described earlier, the gaming journal functioned as a pedagogical tool in carrying out the game-enhanced activities. What is more, the gaming journal served as a rich source of observational data because it offered a way to view students’ hypotheses about and reflections upon linguistic practices, as well as their elaborated thoughts about language use in interactions with the instructor and teaching assistants. These data were important in helping to determine whether or not students exhibited language awareness (Research Question 1). Additionally, the gaming journals contained the screenshots students had taken of their performances in gaming spaces, which offered information about whether or not students participated in gaming discourses (Research Question 2).

The second data source was a survey. The purpose of the survey was to understand students’ experiences in the instructional activities and gaming spaces. The survey was filled out at the end of the semester and included open-ended and follow-up questions about the perceived positive and negative aspects of the instruction, common activities and uses of language that occurred in the gaming spaces explored, involvement in the practices observed and with other gamers, uses of students’ own language inside and outside of gaming spaces, views on digital gaming as an educational resource, and suggestions to improve the game-enhanced activities. This self-reported data complemented the observational data from the gaming journal. Thus responses on the survey provided additional information about whether or not students exhibited language awareness and participated in gaming discourses (Research Question 1). The responses also helped identify supportive and impeding language awareness and gaming participation phenomena (Research Question 2). To mitigate potential student concerns regarding their responses and course grades or teacher expectations, responses on the survey were anonymous.

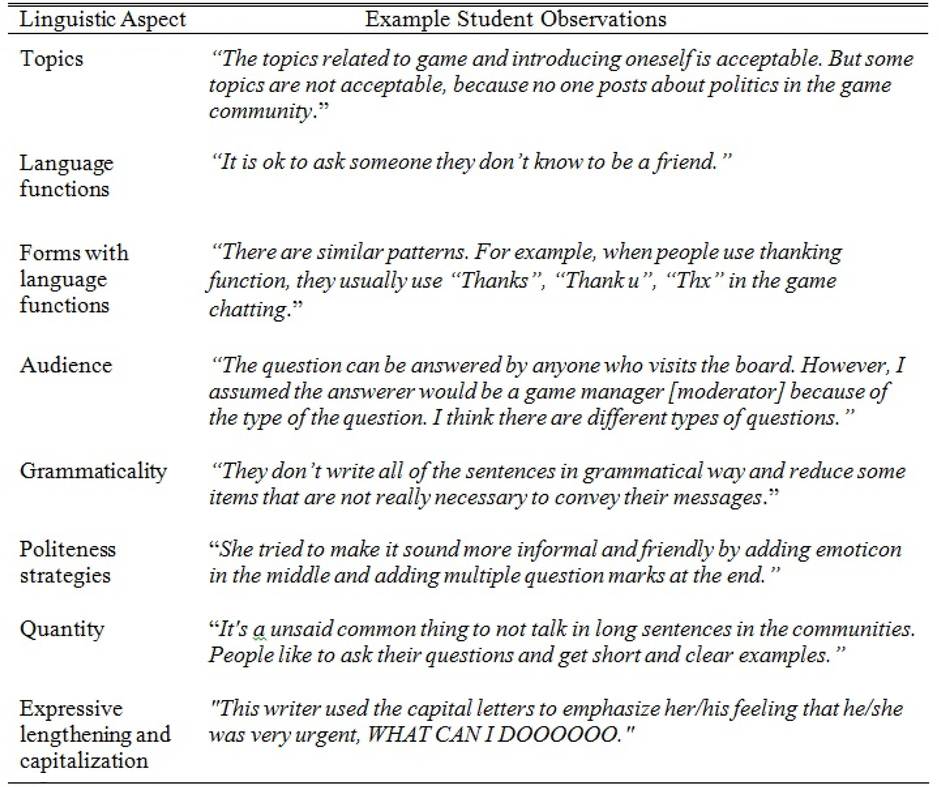

To answer the first part of Research Question 1 (i.e. whether or not students exhibited language awareness), both data sources were examined. Particular attention was paid to student observations, hypotheses, and reflections in the gaming journal, comments on the survey, and interactions with the instructor and teaching volunteers on the wiki. Language awareness entails “noticing and eventually understanding and predicting the variable rules, probabilities, and linguistic choices associated with particular modalities, contexts and communities, and interpersonal relationships” (Thorne & Reinhardt, Reference Thorne and Reinhardt2008: 562–563). The data were inspected for instances of students’ noticing, understanding, or predicting patterns of expression, rules, or linguistic choices related to the gaming and other contexts they examined in the instructional activities. Examples of student comments reflecting language awareness are presented in Appendix B.

The gaming journal and survey were also used to answer the second part of Research Question 1 (i.e. whether or not students participated in gaming discourses). Because the game-enhanced instruction was designed to present opportunities for socialization, participation in the current study included only those student actions that could attract the assistance of others in the gaming spaces they explored. Thus actions such as playing a game alone or reading posts on strategy sites were not coded as instances of participation, whereas interacting with other gamers to complete a quest or posting to forums were. Questions on the survey and sections in the journal that asked students to post their actual in-game and forum performances were consulted to determine how many of the students directly participated in gaming discourses.

To answer Research Question 2 (i.e. what supportive and impeding language awareness and gaming participation phenomena emerged), data from the gaming journal and survey were analyzed following Bogdan and Biklen’s (Reference Bogdan and Biklen2006) coding scheme. First, each data source was read to get a feel for what the data included and then read again to create initial codes for ideas expressed. The data were coded multiple times, each time comparing across data sources and refining the codes to make sure that they did not overlap or that no new codes were needed to account for the data. During this stage, codes such as “resistance to studying gaming discourses” and “difficulties in describing language use” were created and used. After all data were coded, codes were grouped together to form categories. For example, the two codes mentioned previously, along with others, formed a larger categorical unit labelled “negative aspects of instruction.” Categories were then examined for any patterns that explained what supported or impeded the facilitation of language awareness or participation in gaming spaces. Patterns were grouped as themes. For instance, the category “negative aspects of instruction” previously mentioned was combined with other categories to form the theme “impeding language awareness.” The themes, and the most salient examples representing them, are presented and described in the Findings section.

All data analyses were completed collaboratively among the instructor/researcher and the teaching assistants. During the collaborations, there were no attempts to quantify the number of coding agreements or disagreements. However, the reliability and trustworthiness of the analysis was enhanced by including multiple raters, achieving consensus when coding discrepancies arose, and presenting numerous examples of actual data in the report of the study.

3.4 Ethical considerations

There are potential problems and ethical considerations for teachers and researchers who wish to collect and use students’ gaming data. Collecting social media data can put users at risk of harm, particularly when their privacy has been breached and their data have not been properly anonymized (Townsend & Wallace, Reference Townsend and Wallace2016). Additionally, teachers and researchers must realize that attempts to collect social media data may be viewed by students and others as intrusive acts on students’ free time. In order to lessen intrusion and reduce the risk of harm in the current study, students’ online behaviors were not collected or observed directly from gaming sites. Instead, students were given the choice of documenting and sharing screenshots of their online behavior. This allowed them to decide whether or not they wanted to make their online actions viewable to others outside of the gaming spaces in which they participated (e.g. their teacher, researchers), and it also allowed them control over the qualities and quantities of the online actions they shared. Additionally, all user and student data presented in this paper were anonymized. Collecting and presenting gaming data in this way still offered the potential to gain insights into students’ online interactions and language use, but it also added measures to protect students’ privacy and reduce the risk of harm.

4. Findings

4.1 Research Question 1: Do students exhibit language awareness and participate in gaming discourses?

4.1.1 Exhibiting language awareness

Students demonstrated language awareness in multiple ways. One way was to show awareness of the linguistic practices in the particular gaming spaces they explored (see Appendix B for examples of the common practices reported). Students also showed an awareness of the correspondence between the practices they observed and their own simulated or actual gaming performances, as illustrated in the following examples: “My language changed in terms of introducing. Because I’ve saw many people introducing themselves, I just kind of mimic their language use” (S11Footnote 1); “Few people asked questions in polite ways but I was not the case. As I was playing game, I didn’t want to feel formal and stiff by using polite forms to other people” (S7); and “The forms that I found and I might use changed as time passes. I’ve seen many people commenting on the game community using rather casual forms than I used in week 6 journal. That made me to change my comment in more casual and short way” (J13).

Additionally, there was evidence that students were becoming aware of language practices that extended beyond gaming contexts. For example, S8 noted that “My usage of language in my life outside of game changed a little bit because I realized that if I do not know someone well, I used more polite expressions than before.” Other data showed that students reflected upon aspects of national culture. One student, for instance, described that “Koreans tend to be more careful when they are talking in front of a person who is older” (S12). Furthermore, some students noticed the effects of the digital medium on linguistic activity. Reflecting on her own performance, J9 explained that she “used a euphemism. It is on online chatting, people don’t see any additional expression like face expression or gesture.”

Students exhibited language awareness by noticing linguistic practices in gaming spaces, reflecting on their own language use in terms of the practices observed, and displaying a disposition to explore and articulate language in use beyond the gaming contexts they analyzed.

4.1.2 Participating in gaming discourses

Six of the 16 students directly participated in the gaming spaces. These students posted and replied to questions on game forums, helped gamers during gameplay, and coordinated group actions within guilds. Thus, in regard to Research Question 1, the students did exhibit language awareness and six of them (38%) participated in gaming discourses.

4.2 Research Question 2: What supportive or impeding language awareness and gaming participation phenomena emerge?

4.2.1 Impeding language awareness

Three impeding language awareness phenomena emerged. First, there were limitations with some of the gaming sites. These limitations included inactive spaces. Student responses, such as the following by S13, illustrate this point: “Game communities were not that active, even the official community or Facebook.” Another limitation was the narrow range of linguistic functions in some of the gaming spaces that were studied. To this point, a student stated that she “mostly saw the functions of asking for help, giving an instruction, and saying hi to each other, but I could not see other languages except those” (S16).

An additional language awareness hindrance involved explaining how the social context mediated linguistic meaning. The questions posed by the instructor and teaching volunteers played a clear role in directing student attention to aspects of language use. For instance, S4 explained that “when you said compare the form ‘thanking to others’. I realized I use different forms in clan chat and the forum.” However, students struggled to articulate hypotheses about how or why meaning was being actualized. For example, comments such as the following were common among the students: “It was quite hard to answer your comment on my journal. This was because it was difficult for me to explain the reason why” (S15).

These difficulties are further illustrated by a reflection in the gaming journal. In offering an explanation about why different types of forms co-occurred in the space she explored, J2 wrote: “I think the reason why people use different forms is that it just depends on their mind. Some people use informal forms, while others use formal.” Even when students were able to explain contextual influences, such as in the example that follows describing social distance, the students, instructor, and volunteers did not have a shared metalanguage that could be used to examine cases within and across reflections:

I think the relationship between two speakers when they say “please” is they are not so close to each other. I thought like this because I think using “please” means being polite and formal, and people try to be careful, polite and formal to someone they don’t know well. (J5)

Additionally, some students did not feel that exploring social meanings was needed. For instance, S1 explained that

I don’t use the same form or way of speaking when I talk to students or my professors. This is the thing that I already knew. It became kind of a habit to me and made myself to feel unnecessary to think about it deeply.

This orientation was especially prevalent for the students who had reservations about investigating gaming discourses. This language awareness barrier is evident in the following responses, showing that some students did not value non-standardized forms or non-academic domains of English:

While playing the game, I heard and read lots of English such as giving instruction. However, there were not only standard or “normal” language. Rather there were vernacular forms or swear words. (S11)

The words or expressions are all related to the game, not academic subjects. Besides, there are lots of wrong written forms like shortened words, plz (please) and helllpp (help). (S2)

Data show that some students with these types of reservations changed their views over time. For example, S6 stated that “At first I didn’t like to play games, because I thought it was not that helpful for learning language. I thought digital games were only for fun. However now I think digital games have many benefits for learning language.” Additionally, other students were able to challenge some of the stereotypes they held regarding games and gamers: “I realized that there are not many odd people which I thought that were crazy about the game. They did ordinary communication more than I expected” (S15).

Students targeted and reflected upon non-standardized forms, including posts with profanities, but some students remained hesitant about the utility of digital games in language learning and teaching. One student, S3, bluntly stated that experiencing and reflecting upon gaming discourses “was pointless.” Thus language awareness was impeded by limitations within gaming spaces, troubles in explaining how context co-creates meaning, and negative perspectives about the use of gaming discourses in language education.

4.2.2 Supporting gaming participation

Student participation in the gaming spaces was supported in a number of ways. Aspects of the gaming environment played a key role. One important aspect was that students felt that they shared experiences with other gamers. For example, J4 remarked in her journal that “in the community, other players were struggling to achieve the given task just like me.” The gaming environments also provided opportunities to develop friendships, which is illustrated by comments such as, “I developed friendships in my clan. [ID deleted] greeted me when I joined the clan. When I made mistakes she covered for me” (S5). Students also observed models of successful participation from other L2 users, noting, for instance, that “Although her English is poor, the responder understood her enough to be able to give the answer to her question” (J10).

Moreover, students reported that they felt prepared to interact in the discourses in and around games. For instance, one student explained, “I can better perform in game or community discussions than before. This is because I could understand the nature of the community and how people usually have conversations” (S9). Another student stated that, “As I play the game and visit to the game community, I feel more informal than before because I am accustomed to their speaking styles” (J16).

The need to progress in the games they were playing also supported participation. Students participated with other gamers to overcome the challenges games presented. Some participants requested help on game forums, stating, for example, “I’ve been taking advantages of the online communities and getting some answers to other ones that were impossible for me to figure out” (J11). Other students teamed with fellow players to progress in the game. J2 described in her journal that “In order to gain more money and elixir I needed to join clans.”

Additionally, game challenges prompted language analysis. After not passing a task in her game, J7 wrote, “I decided to ask questions to people on the community to ask them about things that I did not know.” For the next two weeks, she observed and analyzed questions on the forum and then posted her first question: “How can you get life points quicker?” In addition to receiving an answer to her post, a point worth making about this question is its similarity with a question that she analyzed in her journal before making her first post: “How to get more LP [life points] in a fastest way?”

There were signs of changes in participation among a few of the students that elected to directly interact with others in the gaming discourses. For example, S10 explained that she started out as a reader on the forum, but later changed: “Around the midterm, I was more of a question-asking participant in the community. However, if I were to participate in the community now, I would be able to answer questions!” Another student’s comments reflect socialization processes that moved her from a novice in the guild she joined to a more central participant:

When I was an unskilled player, I received help and instruction from the member of my guild in order to protect my village from enemies. I learned how to place my resources and deploy troops effectively. Similarly, now I am a skilled player and I can give instructions to the new members who have lower level than me. (S5)

The findings reported here show that gaming participation was supported by multiple affordances within the gaming spaces and the need to progress in the game. They also show that some students changed to more involved forms of participation within gaming spaces as a result of socialization.

4.2.3 Impeding gaming participation

Different phenomena impeded both initial and continued participation in gaming discourses. In regard to initial participation, some students did not attempt to participate in gaming spaces because they held negative views of gaming discourses. This is evident, for instance, in the following quote: “I had difficulty finding an appropriate clan that uses the target language appropriately” (S1).

Game expertise was another factor that influenced students’ decisions to not directly participate within gaming spaces. The students reported that high-level gamers were active on the forums. For example, S4 explained that experienced gamers “know most about the game and they could give the most effective advice.” As most students were new to the games they chose, they were looking up information and questions that had already been asked by other players. Thus, for many of them, this precluded the need to ask questions on forums, which J14’s comment illustrates: “I didn’t have a question yet, I could already find answers.”

Additionally, choosing not to participate on the forums was linked to perceptions about gaming practices. S2 explained, for example, that many players participate by reading and not posting on game-related sites:

There were lots of people who just saw what others said and got information from that community like me. I thought I was not part of the community in a direct way, rather because I got lots of information from it, I thought I could be one of the members in an indirect way.

Posting comments on the forums, therefore, was not an action students felt that they needed to take. This sentiment is expressed by S16, who stated, “I can participate in the game discussions. However, I don’t feel I have to participate in the discussions.”

Other data showed that even when students elected to participate in gaming spaces, they were not always successful in their attempts. Impediments to continued participation in gaming discourses consisted of failed participation bids. One type of failed participation was not securing entrance into certain spaces or groups. For instance, S8 noted that she requested access to a site and was never granted access to it, adding that “if I have a chance, I can definitely participate in the game community and can write questions or comments and discuss them with others easily.” Not receiving replies to online postings was another type of failed participation bid that impeded continued participation. This was experienced by J7, who was mentioned in an earlier example asking her first forum question about life points. Although her first question was answered, her next question was not and she did not attempt to post on the forum again. Her remaining journal reflections included further observations and analyses about the forms and styles others used to ask questions, which she used in simulated scenarios on the journal.

There were two other students who reported that their forum postings were not acknowledged. For S14, not getting a reply resulted in negative feelings and a lack of motivation to participate in the forum she observed:

I never got an approval from one community and another one I never got anyone to respond to it. I think I was frustrated and gave up towards the end. I don’t think I’m part of the community and I felt neglected because no one answered my questions. Not only was I frustrated, but I think I was confused and bitter as to why people weren’t answering my questions when I was genuinely curious.

Thus participation was impeded in many ways. Negative views of gaming discourses, levels of game expertise, and perceptions of gaming practices hindered initial participation, whereas failed participation bids deterred continued participation in gaming discourses.

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Limitations of the study

In addition to the small sample size, a limitation of the study was that the participants were enrolled in an elective course on teaching with technology. These students may have different expectations and dispositions towards technology and its uses in instruction than students in courses that do not have an explicit focus on technology. Additionally, the study did not attempt to explore facilitative or impeding language awareness and participation phenomena in relation to particular player variables or particular games. Different games and gaming genres include different design and gameplay mechanisms (Sykes & Reinhardt, Reference Sykes and Reinhardt2013) and thus, similar to player variables such as playing styles, may create variable affordances for students.

It is also important to acknowledge that the screenshots students took of their own gaming actions offer only a glimpse of what actually occurred during their time in gaming spaces. Additionally, with the researcher serving as the instructor of the course, the information that the participants disclosed was likely influenced by their student identities. For ethical considerations discussed earlier, students were allowed to choose which gaming performances to enter in their gaming journals, and they also chose which gaming experiences to discuss on the survey. Therefore, the researcher serving also in the role of instructor may have, paradoxically, provided possibilities for sustained observation and greater contextual understanding, while also potentially influencing the range of behaviors and phenomena that could be observed and thus understood.

5.2 Interpretations and implications

In regard to the language awareness findings, students were able to notice and reflect upon linguistic practices within the gaming spaces they observed, use these practices to evaluate their own performances, and, to some extent, examine language use outside of gaming contexts. This confirms reports from other studies in the literature showing that building experiential and analytical activities around social media can support student literacies by enhancing awareness of situated language use (Blattner & Fiori, Reference Blattner and Fiori2011; Reinhardt et al., Reference Reinhardt, Warner, Lange, Guikema and Williams2014; Reinhardt & Zander, Reference Reinhardt and Zander2011). However, the impeding language awareness phenomena reported in this study suggest that there were missed opportunities in raising student awareness about the relationships between language use and the context in which it was functioning. Key issues were a lack of conceptual grounding and an absence of a shared metalanguage to explore instances of language use that students posted in their gaming journals. Going back to the pedagogical framework used in this study, these problems relate to the guided exploration and analysis phase of the BA cycle. Although it is important in a language awareness approach that students discover social meanings of language for themselves, analytical activities are designed to support this process. The BA framework advocates comparisons between texts and contexts using comparative questions to help students better understand language choice and social meaning. Without conceptually grounding concepts or a way to talk about them, students in the study were mostly limited to noting (and potentially imitating) the linguistic practices common in the particular gaming spaces they explored, instead of systematically understanding how and why other gamers used language to realize desired meanings. The exploration and analytic component could be strengthened in many ways. For instance, one way would be to use student examples in explicit guided instruction to learn about politeness theory (Brown & Levinson, Reference Brown and Levinson1987). Another possibility would be to incorporate aspects of the concept-based instruction described in van Compernolle (Reference van Compernolle2014). He developed materials to illustrate various pragmatic concepts (e.g. social distance, relative status) that students can use as tools in interpreting language use and planning their own performances. There might also be activities that involve the whole class, with students presenting an instance of a success, issue, or failure, and then discussing and analyzing it together with classmates and the teacher. These ideas could strengthen the guided exploration and analysis activities used in this study.

In line with Reinhardt and Zander (Reference Reinhardt and Zander2011) and Reinhardt et al. (Reference Reinhardt, Warner, Lange, Guikema and Williams2014), this study found that some students held negative views about studying digital gaming discourses. However, it also found that some of these negative views changed over time. Changed views may have been encouraged by opportunities for extended gameplay in order to revise stereotypes of gaming and gamers, activities and references used to introduce and position gaming, and the educational discourses within the course that valorized communicative language teaching. Thus the current study suggests that students may need extended experiences within gaming spaces and exposure to discourses that explain how gaming actions benefit language learning.

In regard to participation, the current study found that instruction is associated with direct student participation in the gaming spaces they observed and analyzed. In addition to, for instance, posting on forums and helping other players within the game, this study found that some students reported moving from the periphery of certain gaming spaces to more involved forms of participation as a result of socialization. Although additional data are needed to confirm the self-reported data from which this finding comes, direct participation and socialization in the practices of social media spaces has been mostly limited to research on L2 users in the out-of-the-classroom digital wilds (Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019). Research on instructional uses of social media, on the other hand, has primarily focused on student attitudes and dimensions of language awareness (Blattner & Fiori, Reference Blattner and Fiori2011; Reinhardt et al., Reference Reinhardt, Warner, Lange, Guikema and Williams2014; Reinhardt & Zander, Reference Reinhardt and Zander2011) and community development among classmates (Mills, Reference Mills2011). Thus finding instances of direct participation in gaming spaces and changes in it add to this literature. The students felt prepared to engage in the linguistic practices of the gaming spaces but other phenomena also supported participation, such as safe environments and opportunities for collaboration, which have been reported elsewhere (Rama et al., Reference Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012). Similar to Ryu’s (Reference Ryu2013) findings, opportunities for collaboration in this study were linked to overcoming game challenges, which proved to be a significant reason for students to interact with other gamers. This underscores the importance of game engagement and, pedagogically, choosing challenging games to play. In future studies, participation needs to be investigated with a close analysis of the potential in- and out-of-game socialization processes that may help account for it. For instance, Reinhardt and Zander (Reference Reinhardt and Zander2011) reported that experienced gamers accounted for some of the success in a second iteration of game-enhanced activities. Participants who reported participation changes in the current study included a student who gamed regularly and had more than three years of gaming experience and a student who was a gaming novice. An earlier example showed that the novice gaming student received help from other gamers during in-game experiences, but it would be interesting to see, for example, if the experienced gaming student had any bearing on her participation, as they both played the same game. To investigate this, future researchers will need interactional data from student gameplay sessions and classroom collaborations and an analytical focus on documenting changes in the use of semiotic forms to perform specific gaming practices and identities.

The promising participation findings are tempered by the discovery of impeding phenomena. It was found that there were failed participation attempts. Gee (Reference Gee2008) explained that participation failures can prompt one to reflect back on performance and come to learn ways to participate in specific discourses. Failed attempts at participation appeared to have led at least one student back to a focus on her performance and the linguistic practices within the forum she analyzed. However, this student, and the other students who did not get replies to their posts, stopped trying to participate. Failed attempts and halted participation are somewhat reminiscent of Hanna and de Nooy’s (Reference Hanna and de Nooy2003) findings, where some students tried to participate in an online forum and stopped after they were disciplined by forum members for not displaying localized forms of behavior. In the current research, it is not as clear as to why some students did not receive responses to their posts. One explanation is that some of the spaces where students posted were inactive, as indicated in the findings. For pedagogy, this means that students need to be informed of ways to evaluate the activity of social spaces, such as how frequently people post and how long until others reply. Furthermore, instances of participation posted in the gaming journals show that there were times when students used guest accounts to post questions instead of accounts registered to the gaming space. Displaying affiliation to a particular domain is performed through various indices (Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019). Thus another explanation is that using guest accounts and not displaying other forms of affiliation may have indexed some of the students in the current study as outsiders in the spaces they visited. Not knowing why participation failed points to a larger pedagogical issue. Teachers need to recognize the trade-offs in game selection options. In the current study, students had multiple options for the games they played. Choosing one’s game likely has consequences for levels of game engagement and, as stated earlier, possibilities for direct participation in terms of soliciting assistance from other players. However, presenting multiple game options also means that teachers will probably not be aware of the distinct discourse practices within the gaming spaces chosen by students. Another option is to select one game for the entire class, become proficient in it, and lead students through it (e.g. Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Newgarden and Young2012). This option may allow the teacher to better understand failed participation attempts and more precisely direct student attention to particular practices than an approach that includes the option of students selecting their own game and using general prompts in a gaming journal.

There are additional implications if one considers the other impeding phenomena. It was found that some students intended to read but not post to game-related sites, and that it may take time for students to develop high levels of game expertise before directly participating in these spaces. For game-enhanced pedagogy, these findings suggest that direct student participation in gaming discourses, particularly those outside of the game, may not be a reasonable expectation for beginning gamers and should not be an instructional requirement. Another possibility for sheltered participation might be for learners to present about their game to a limited audience (e.g. their classmates) or critique it on blogs or other sharable media. For research, these findings highlight the need to examine the socialization possibilities and qualities between games where collaboration is a common aspect of gameplay itself, such as in multiplayer games, and other games where collaboration is primarily a function of participating on game-associated sites.

6. Conclusion

This study sheds new light on important aspects of game-enhanced approaches to L2 teaching and learning. In addition to confirming language awareness possibilities using experiential and analytical instructional activities, this study identified potential pedagogical design weaknesses and offered suggestions to strengthen them. This study also outlined areas of exploration for future research, such as socialization processes inside and outside of classrooms and within different gaming spaces. Furthermore, the current study suggested that introducing digital games through instruction does not mean that students will directly participate in gaming discourses, and that when they do, some may experience frustrations, whereas others may experience L2 socialization.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Sookmyung Women’s University Research Grant 2019.

Ethical statement

This study was carried out in accordance with Sookmyung Women’s University research policy. Participants were volunteers. There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A An example gaming journal entry

Appendix B Commonly reported linguistic practices

About the author

Levi McNeil (PhD, Washington State University) is a professor in the Graduate School of International Studies and TESOL at Sookmyung Women’s University in Seoul, South Korea. His research interests include CALL teacher education, new media and literacies, and situated learning. Published works on these topics appear in, among others, Language Learning & Technology, Language Awareness, and Language Teaching Research.

Author ORCiD

Levi McNeil, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2381-6064