Certain kinds of practices which are designed to handle certain kinds of problems produce, over time, a settled domain of ontology as their consequence, and this ontological domain, in turn, constrains our understanding of what is possible.Footnote 1

Masculinity becomes legible as masculinity where and when it leaves the white male-middle class body.Footnote 2

Introduction

If diplomacy is the practice through which estrangement is mediated, then drag can be regarded as a practice through which diplomatic practices are estranged. Drag performance works as a social, cultural, and political commentary that sheds light on the implications of hegemonic disciplining around gender, class, and race. This article presents drag performance as an aesthetic and queer method that defamiliarises dominant practices in international politics and as a performative method that disrupts normal practices of knowledge production in the field of International Relations (IR). This article reflects on the author’s production of the performance piece, ‘Politics in Drag: Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’, a 45-minute solo performance that restages the EU’s response to Hamas’s success in the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections through the tactics laden in drag. This article reflects on how rituals around diplomatic dress, voice, and location shape the kind of politics that can be uttered. It turns to performance art to destabilise these rituals, in order to create space for a different kind of political conversation around Palestinian politics. This article reflects on how the form of research presentation and dissemination shapes the kind of knowledge produced. It maps out the significant methodological contributions of drag and contributes to feminist, queer, and postcolonial moves to decentre knowledge production.

Whereas Beyoncé commands us to get in formation, Janelle Monáe pushes us to think about the multiple types of formations we might discover in the groove, in the sheets, and on the streets while also blurring the line between these contexts.Footnote 3 Queer methods in IR explore how political issues are made sense of through a reproduction of the categories of normal or perverse and the policing of what these categories entails.Footnote 4 Ritualised diplomatic practices and discourses stabilise over time, creating an idea of the normal, which then limits the possibility for creativity and change in the responses to political events. In Faking It: U.S. Hegemony in a ‘Post-Phallic’ Era, Cynthia Weber describes how masculine hysteria is enacted upon resulting in aggressive foreign policy practices, such as the US military invasion of Panama.Footnote 5 I suggest that drag performance is a way of attending to some of this hysteria. It shows that what is regarded as normal, such as strategic thinking or even realpolitik are performative practices, spawned out of anxious attachments that are taken as normal and natural.

Drag rearticulates popular cultural codes around the feminine and the masculine and their intersections with race and class, in order to expose the anxieties that shape ‘normality’. Drag emphasises the stresses behind passing, the demands of conformity, and the pressures of having to perform the ‘normal diplomatic man’. This understanding of drag starts with Judith Butler’s position that

in imitating gender, drag implicitly reveals the imitative structure of gender itself –as well as its contingency [and the perpetual displacement of the original] constitutes fluidity of identities that suggests an openness to resignification and recontextualization.Footnote 6

Butler’s work reminds us that what is exteriorised can only be understood through what is barred and foreclosed. Interrupting diplomatic practices, which may be an expression of hegemonic forms of rational, serious, and strategic thinking, with tenderness, humour, and pain may provide an alternative departure point from which to configure political possibilities.

This work emerges from the author’s research into the EU’s response to Hamas’s success in the Palestinian legislative elections in 2006, and the common expression of dissatisfaction surrounding the EU’s position. Diplomats within the EU and within the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPTs) explained their disappointment with the EU’s response of diplomatically, financially and physically sanctioning the newly elected Hamas government in 2006. The EU had supported the elections financially and politically, and democratic reform was part of EU state building initiatives.Footnote 7 However, their response of a ‘no contact policy’, the refusal to host any Hamas diplomats within Europe and the redirection of all aid and funds away from the Hamas government and towards the Fatah-dominated Palestinian Authority (PA) worked against the EU’s stated objectives for supporting the elections.Footnote 8 EU leaders, both at the time and years later recognised that this was a failed diplomatic response.Footnote 9 While the EU placed three conditions on Hamas, which the movement had to abide by in order to be treated as a ‘normal’ diplomatic actor, the EU’s no contact policy removed any possibility of observing changes within the movement. The response did not ‘make sense’ according to the EU’s own logic. A senior EU diplomat argued that there were no benchmarks in place to ensure that the conditions operationable.Footnote 10

The EU’s response to Hamas’s success can be framed as a missed opportunity, or a failed response.Footnote 11 Queer epistemologies, however, encourage us to query what counts as failing within certain regimes of success and failure.Footnote 12 As such, perhaps the EU’s response can be regarded as successfully performing certain ‘normal’ practices within diplomatic and international relations.Footnote 13 This project uses performance art to rearticulate the possibilities and practices that were removed from the table or foreclosed from the public iteration of politics, because of an attachment to institutional rituals and ‘common sense’ politics. In the performance produced by the author, interviews with EU and Hamas diplomats and other fieldwork artefacts are rearticulated in a melancholic, hyperbolic, and parodic fashion in order to provide an alternative critical position on the EU’s engagement with Palestinian politics. This article accompanies a filmed version of the performance piece, and acts as a commentary on the contribution of the work to queer methodologies in IR and to the aesthetic turn, speaking specifically to the transdiscplinary work between performance and politics.

Aesthetic methodologies can challenge taken-for-granted and common sense approaches to politics, and create knowledge and thinking at different registers.Footnote 14 The critique generated through the performativity of aesthetic practice attempts to create phenomenological bonds with its audience and inspire a different kind of thinking and feeling towards Palestinian politics. The performance art presented here is one that challenges heteronormative and masculine boundaries around knowledge production in the academy. By performatively enacting a different response to that of sanction and condemnation, I suggest that we might engender new epistemological considerations for the possibilities of diplomacy. Drag is presented as a queer and aesthetic mode of critique that has the potential to open a series of crucial methodological questions, such as: what counts as proper political research? What counts as proper/acceptable iterations of politics? How do dominant presentations or expressions of politics or political research reflect certain gendered, racial, or class norms? How does the form of expression in turn shape what can be said?

First, this article places drag performance in conversation with both queer methods in IR and the aesthetic turn in IR, emphasising the links between politics and performance. The article then discusses the author’s performance piece ‘Politics in Drag: Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’. This section discusses how the performance critiques normalised rituals around dress, voice, and location in diplomacy. Other ‘drag moments’ reflect on the politics and restrictions of passing, such as anxieties around Jeremy Corbyn’s outfits, Barack Obama’s use of an anger translator, and Joan Jett Blakk’s mayoral race. In the third section the article reflects on the wider methodological contributions of political drag performance. Reviewing performances, principally from minoritarian artists, such as Vaginal Davis, Janelle Monáe, and Tania El Khoury, the article discuses three methodological provocations of drag. First, drag presents an alternative departure point from which to critique politics, from the place of the ‘what if’. Second, queer and drag practices enact a politics of refusal, which turns away from dominating orders of suitability and acceptance. Last, drag is a tool of defamiliarisation and the Brechtian technique of estrangement, which provokes audiences to challenge their own place in social hierarchies, and moreover how this might relate to their own biases around what counts as knowledge.

Performing methodologies

Queer methodological practices are orientated towards demystifying and debunking ideas of normalcy, and the ‘normalizing mechanisms of state power’.Footnote 15 Weber’s writings on queer methods in IR draws attention to how the demand to know something or someone as perverse or normal. This ordering shapes how issues in global politics, such as the ‘unwanted im/migrant’ or the ‘al-Qaeda terrorist’ are constructed and responded to.Footnote 16 In a forum on queer methods V. Spike Peterson writes,

A key insight of queer analytics is that codes and practices of ‘normalcy’ simultaneously constitute ‘deviancy’, exclusions, and ‘otherings’ as sites of social violence. To reveal how power operates in normative codes and normalizing practices, queer theory aims to ‘make strange’ – disrupt, destabilize, deconstruct, effectively to queer – what is considered normal, commonplace, taken-for-granted, or the ‘natural order of things’.Footnote 17

Through its critique of normalcy, queer methods expose the violence of belonging and not belonging. ‘If queer is understood as a critique of the normative, then queer is also a mark of unbelonging.’Footnote 18 Queer interventions can identify the regimes of intelligibility that define who is deserving of protection and who is not;Footnote 19 what constitutes a family or not;Footnote 20 what counts as success or failure.Footnote 21 Moreover, the configuration of the ‘perverse or normal’ structures what appears as possible in international relations; it marks the limits of what we are able to imagine. Drawing on Butler’s work, Closs Stephens writes that the ‘problem lies not so much in the identification of the terms of “good” and “bad”, “civilised” and “uncivilised” but in that we might disagree with this framework of options as one we must accept for making sense of politics’.Footnote 22 Butler’s point, says Stephens, ‘is that we need to refuse the teleology that marks both the origins and limits of what we are able to imagine’.Footnote 23

Queer methodological practices can highlight the tensions and anxieties that circulate around expectations to fulfil social and cultural roles. Butler’s work highlights how gender is not expressive of an internal, stable, inherent identity, but how gender is shaped by social and cultural rituals and historicities. Butler explains there are punitive dimensions to expressing gender configuration that challenges dominant regimes of intelligibility.Footnote 24 My intervention stresses the anxieties, challenges, and demands associated with passing as a ‘normal’ diplomatic actor, or ‘strategic’ policymaker, and the knowledge practices attached to these public roles. This research lays analytical focus on what it takes to belong in diplomatic circles and the implications of successfully belonging or passing. It emphasises the kind of language, tone, or sentiment that are foreclosed from international diplomacy because of several logics of attachment, such as an attachment to aggressive or tough masculinity, or an attachment to a ritualised construct of strategic thinking. Tone and language in turn limit what can be articulated; drag as a method opens up these tensions and limitations.

Performances of masculinity are undone through the hyperbolic and melancholic strategies of drag. When the tropes of masculinity are performed by gendered female bodies, the expressions of masculinity become malleable, laughable, or outrageous. Judith Halberstam notes that while black masculinities or queer masculinities have already been rendered visible and theatrical,Footnote 25 ‘for the white drag king performing conventional heterosexual maleness, masculinity has first to be visible and theatrical before it can be performed’.Footnote 26

The drag king performance, indeed, exposes the structure of dominant masculinity by making it theatrical and by rehearsing the repertoire of roles and types on which such masculinity depends.Footnote 27

Drag, therefore is a crucial tool in denaturalising dominant masculinities, and can be used in the field of IR to dislodge dominant iterations of politics. Laura Sjoberg argues that queer theorising does not have to reject conversation with mainstream IR, but rather, queer critique can be fruitfully applied in conversation with ‘mainstream’ IR.Footnote 28 Sjoberg discusses the use of drag to as a practice of rearticulation of ‘the border’, and argues for a move away from a desire or fetishisation of the stable border, as if it will bring peace and stability. Drag is used in this project here to denaturalise and rearticulate dominant practices in diplomacy, and more specifically, to performatively present an alternative articulation of the EU’s engagement with Hamas.

The 2006 elections, and the external response to Hamas acted as a turning point in Palestinian politics, marking a distinct shift in the levels and forms of violence waged against the Palestinians by the Israeli occupying forces, supported by European and American policies and practices. Both European and Palestinian observers argued that Hamas should have at least been given an opportunity to govern under as normal conditions as possible, and be voted out under democratic process should it fail.Footnote 29 The demand to know Hamas as already a terrorist and the ritualisation of EU institutional and discursive practices closed down such an opportunity.Footnote 30 I suggest that performance art presents an opportunity to revisit this turning point. In the theatre space or the imaginative space new political initiatives can be experimented with, and new political subjectivities can be performed.

Jef Huysmans and Claudia Aradau argue that rather than regarding method simply as a tool that links our empirical research to our theory of choice (ontological scope to epistemology), methods can be regarded as devices that are active in reproducing the social and political world. ‘Understood as acts, methods can become disruptive of social and political worlds.’Footnote 31 Drawing in Isin’s work, Huysmans has reflected on the possibility that certain methodological choices can rupture knowledge production irrespective of their acceptance or institutionalisation.Footnote 32 Much of the investment in the aesthetic turn in IR has been concerned with this question of disruption: that interdisciplinarity can provide new ways of approaching issues in global politics. In presenting a way for transdisciplinary methods, Michael J. Shapiro expresses that

Aesthetic experience has a political effect to the extent that … it disturbs the way in which bodies fit their functions and destinations … It has a multiplication of connections and disconnection that reframe the relation between bodies, the world they live and the way in which they are ‘equipped’ for fitting it.Footnote 33

Within IR, many have called upon Jacques Rancière’s writings to explain this intention to disrupt through the provocation of the aesthetic. Rancière argues that moving between and in-between politics and aesthetics allows for a stretching of the boundaries of plausibility.Footnote 34 Through Aristotle, Rancière moves to undo the dividing line between history and story, between what happened and what could happen. The poetic arrangement inspires ideas of what could be possible.Footnote 35

Performance art, I suggest, occupies an important place in the stretching of expression and plausibility. Interdisciplinarity between politics and performance is a growing area in the field of IR.Footnote 36 Shirin M. Rai and Janelle Reinelt emphasise the common grammars between the two fields, which are ‘comprised of inter-related discursive and embodied practices’.Footnote 37 Jenny Edkins and Adrian Kear describe the working of ‘performance and politics as “folded” in myriad and complex patterns, interanimating one another as domains of political subjectivation and creative practices undertaken by aesthetic subjects’.Footnote 38 Performance art holds a unique position in its blurring of the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction; between history and story; between what is possible and what could be possible. While performance art is bound by the materiality of embodiment, it seeks to stretch the limits of what is possible, of what can be possible. Performance scholar Peggy Phelan believes ‘Performance art usually occurs in the suspension between the “real” physical matter of the “performing body” and the psychic experience of what it is to be em-bodied.’Footnote 39 Here the writing and producing of a performance piece are themselves methodological practices that performatively disrupt epistemological frameworks in politics.

By using diverse methods to disseminate research, such as narrative, collage, song, and photography, feminist, queer, and postcolonial are engaging in radical practices that can alter how we approach political issues.Footnote 40 Sophie Harman writes of the importance of beyond text methods and particularly the feminist use of visual methods, which challenge elite narratives and hierarchical forms of knowledge production.Footnote 41 Saara Särmä presents collage-as-a-method that resists straightforward interpretation. Särmä’s work around gender parody and the ‘Congrats, You Have An All Male Panel!’ tumblr page uses images of David Hasselhoff to create a new, transnational impetus for change.

The dissemination of my research through drag aligns with the queer methodological practices of disturbing what counts as serious, or rigorous, and how this categorisation polices what counts as research, and as such, knowledge. The presentation of research in this way does not mean that it should be taken any less seriously; rather it interrogates the structure and category of seriousness, asking what does it mean to be serious? Where does serious get us? Where has serious gotten us? Who gets to be serious? And what does one have to say or be in order to be taken seriously? Rahul Rao suggests that Weber’s work on queering IR and particularly the publication of Faking It allowed Rao to narrate International Relations in a mode that was ‘critical, funny, voraciously interdisciplinary [and] that would have been inconceivable, perhaps even impermissible before its publication’.Footnote 42 Weber elaborates on the possibilities of queer method:

The resulting ‘deviant knowledges’ of international relations [queer methodologies] produce can disorient Disciplinary IR knowledges not only about queer subjects (Ahmed 2006) but also about international relations subjects and the discipline of IR as a subject.Footnote 43

Performance art may reveal what is left out of ‘normal’ practices of disseminating political research; it can show the entangled expressivities and tensions of different spaces and political subjectivities.

‘Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’ and other drag moments

In this section I will reflect on the performance piece I produced out of my doctoral research, and I will put this in conversation with other drag moments in global politics. The performance piece, ‘Politics in Drag: Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’ was first staged at the Aberystwyth Arts Centre in May 2014. The performance was open to the town and to the university’s community. The response was exceptional: audience members found the performance moving, tender, informative, and funny. It allowed participants to access academic research in a way that is accessible, phenomenological, entertaining, and educational. The performance piece has since been shown in various academic and theatrical settings, and the piece itself blurs the boundaries between these spaces, creating a hybrid academic/art space. I invite you to watch a video recording of the performance, which was filmed at The Showroom, Chichester, April 2016.Footnote 44 What follows is a critical reflection on some of the strategies and tactics of rearticulating the EU’s response to Hamas’s success through drag.

The performance is comprised of five scenes. The performance contains segments from my interviews, photos taken while conducting my fieldwork, empirical evidence from documents, and artefacts from my visits to Gaza and Brussels. It begins with an introduction that outlines the performative ontology at the centre of the project: that political relationships are constrained by their historicity, but that they are malleable. I state that the performance is a work of fiction based on my years of research, fieldwork, and interviews on the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections. I explain that it is my fiction, and as such an exposition on my own hidden desires and excess wants, of what how I wish politics could be. The first scene entitled, ‘What a Fucking Shame’ offers a brief introduction to the EU’s response to Hamas’s success in the 2006 elections. It outlines the expectations, hopes, and desires that Hamas’s participation in the electoral process might have allowed external actors to shift their engagement with Hamas and with Palestinian politics more generally; but that the EU’s response to Hamas’s success tells a very different story, what a fucking shame.

Costume

In the second scene of the performance I use costume techniques to display how rituals around dress both reveal and conceal (Figure 1). Phelan remarks how performance art plays with regimes of visibility and invisibility; performance can be regarded as a process of revealing while concealing. In this scene, entitled ‘Masked Excess’, I suggest that something remains hidden in ‘doing what we always do’, in performing those rituals around elections and monitoring elections. Rituals around dress allow distinct bodies to belong to a particular space, such as the diplomatic space, or the formal political space. However, rituals are also oppressive in that they demand conformity. I use this opportunity to put on a blue suit to perform the ‘serious man’. There is a disjuncture between my ‘small’ body in ‘their’ large suit. At the same time the suit ‘fits’, by putting on the suit I too can perform the diplomat, the bureaucrat. Both my interviewees in Brussels and Gaza wore suits. Dress has a way of trying to control who can fit and who cannot fit, of who can belong or not. Costume, such as wearing a necktie to perform the businessman provides an opening and opportunity for passing. Within the form of the drag performance, the symbol of the necktie also offers an opportunity for disturbing continuity, as the female performer inhabits and satirically plays with the trope of masculinity.

Figure 1 ‘Politics in Drag: Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’, 23 May 2014. Photographer: Hannah Mann.

Jeremy Corbyn has come under attack from the British press for failing to perform the ‘serious’ political man. The attire of female political figures often becomes a location upon which the policing of gender roles plays out. Here, discussions around Corbyn’s dress present an interesting case of the intersection between masculinity and class in the British political establishment and the popular British imagination. Corbyn’s public dress was deemed as not being that of a statesman; his ‘not fitting in’ remarks on tropes of normalcy. While Vogue UK presents Corbyn’s dress as a fashion statement, which has not yet jettisoned its ‘Eighties casual’ habits. These are also just his clothes, which he described in an interview as ‘a jumper knitted by his mum, and possibly one of his trademark £1.50 vests underneath, purchased from B & H Quality Underwear & Socks in Nag’s Head Market, north London’.Footnote 45 Vogue UK compares these to ‘one of the £3,500.00 Richard James suits favoured by David Cameron, or even a similarly priced Gieves & Hawkes suit that Gordon Brown was said to wear’.Footnote 46 The mother figure reappears in Cameron’s attack on Corbyn during Prime Minister’s Questions, when Cameron exclaimed,

Ask my mother? I think I know what my mother would say. I think she’d look across the dispatch box and she’d say: put on a proper suit, do up your tie and sing the national anthem.Footnote 47

Corbyn’s dress becomes a site of discipline, where his attire is performative of not belonging. This reflects on the importance of dress and its links with class in British politics. Corbyn’s clothes only become acceptable in locations such as GQ and Vogue when they are read as being a fashion statement or a style, rather than just a reflection of a man and a politician that does not spend £3,500 on a suit. In a 1984 interview with Newsnight Corbyn remarks, ‘[Politics] is not a fashion parade, it’s not a gentleman’s club, it’s not a banker’s institute, it’s a place where the people are represented.’ Yet it is Corbyn’s outfits, not Cameron’s, that raise alarm.

Corbyn is scripted as not being manly enough, or not being the right kind of man to lead. Annie Teriba’s comments that Corbyn’s anti-imperialist stance can be read as queered understanding of masculinity, whereby his anti-war stance is not only read as feminine passivity, but as irrational. Teriba writes, ‘As for Corbyn, he is the only thing more frightening to liberalism than beheadings – he who will not go to war.’Footnote 48 The disciplining of Corbyn’s drag can therefore be read as a policing of the difference his iterations of gender perform.

Voice

Diplomatic practices are performances that are disciplined by routine, and through repetition, certain language, rhetoric, expressions, or disclosures may be ritualistically excluded. In my performance piece, I embody my interviewees, who were for the most part men. My ‘girl’ voice (which someone described as squeaky) enters the diplomatic space. ‘Their’ script is said in ‘my’ voice, the voice of a young woman. I repeat their words sometimes in a camp voice, or sometimes in a sad, childlike voice. My voice, which is not the usual diplomatic voice, performatively reminds the viewer of what, or who counts as normal in formal diplomatic encounters.

Why does my voice appear so out of place? What does this say about the kinds of voices that normally speak diplomacy? Voices, explains Rai, can mark the appropriateness of political claim-making.Footnote 49 Some voices are well modulated, ‘cultured’, while others are deemed shrill and rough. Voices often undergo training in order to fit. Halberstam explains that a childlike voice is unruly, it is the expression of the self before it has been disciplined by the adult world.Footnote 50 Children have appeared in parodies before in order to mock the adult world. When adult routines are performed by children they appear absurd and ridiculous. I use a soft/childlike voice in the performance to allow for sadness to be expressed. Within the performance the Hamas representative asks the EU representative: ‘Why did you have to be so mean?’

The intervention of tenderness and softness into the diplomatic conversation remarks on what has been barred from normalised performances of diplomacy. Psychoanalytic critiques stress that what is ‘exteriorized or performed can only be understood through reference to what is barred’.Footnote 51 Weber explains that the failure to enact a kinder politics can be seen as an aggressive response to anxieties around gender performance; ‘hysterical excess is displaced from his physical body to his geopolitical body’.Footnote 52 Through drag, my performance enacts a kind of language or tone that is normally barred from public performances of politics, such as the displays of sadness, softness, and remorse. In the performance the EU diplomat hangs his head and mutters an apology. The ‘actors’ (me) interject with excuses and a defence of their actions. However, the fictional rewriting of their response is interrupted with excerpts from the EU’s actual response. ‘The conditions were the only policy on offer. They were a strong anchor that everyone could agree to.’ The performance plays with an oscillation between what happened and what could happen. This melancholia for a politics that was not engendered is supported by my interviews and secondary material, which showed that many EU bureaucrats felt their response to the Palestinian elections was wrong. In this vein, the performance displays the melancholy for the kinds of political relationships and outcomes that were foreclosed from possible action.

Rather, the EU’s decision to support Israel’s and the US’s securitisation of Hamas can be viewed as the continuous reiteration of masculinities that are performative of a paranoid fantasy of the ‘nature of man and politics’. Di Stefano, cited in Carver’s comments on the self-originating and self-driven dynamics of politics imbued in Hobbes’s depiction of life and the need for sovereign control. Hobbes’s writing emerges from a fantasy of masculinity and men, whereby ‘men [are] magically sprung like mushrooms, unmothered and unfathered’.Footnote 53 Hobbes develops his politics through a fantasy of the atomised male, conceived along egoist masculine lines. It is an ego constituted in strict either-or terms, and is socially approachable only on the terms of contracted, nominalist, or combative exchanges.Footnote 54 The authors comment that it is no doubt that politics based on this fantasy of the male ego is presented in combative terms.

What is foreclosed, therefore in the reproduction of ‘manly’ politics? What alternative arrangements are barred from exteriorisation in the models of sovereignty and diplomacy that emerge from ‘self-sprung men’? “Ultimately we confront today the Hobbesian solution to the inevitable civil war of all against all that masculinized egos generate: ‘narrowly calculating leaders’ ruling social and political world.’Footnote 55

Butler suggests that drag can be understood as an acting out of unacknowledged loss, ‘a loss that is refused and incorporated in the performed identification’.Footnote 56 ‘There is an attachment to, and a loss and refusal of the figure of femininity by the man, or the figure of masculinity by the woman.’Footnote 57 The drag performance has the possibility to express that which remains barred, or foreclosed in the realm of normalised political presentations.

Playing with tone and voice opens up the possibility for iterating a different kind of politics. President Obama’s White House Correspondents’ Dinner in 2015 disrupts the coherence and the logics of exclusion that constitute the public presidential office as a space of white language and public disposition. Obama invited the comedian Keegan-Michael Key to act as the president’s ‘anger translator’. Obama uses the comedian’s character from the Key & Peele show during the Correspondents’ Dinner to enact a language and disposition that has been excluded from formal American politics.

Luther, the president’s anger translator exclaimed, ‘I have a birth certificate. I have a birth certificate. I have a hot diggity, daggity, mamase mamasa mamakusa birth certificate, you dumb-ass crackers!’Footnote 58 In an interview, Key describes the ‘cracker line’ as a sort of orgasmic moment for black people.Footnote 59 The use of drag here, as rearticulating the codes of the American presidency, or ‘code-switching’ allows for new things to be said. ‘It felt like there were a bunch of things that were not being said that should have been said.’Footnote 60

In the Correspondents’ Dinner Speech, which is a site already cordoned off from ‘normal’ political rituals, Obama is able to play a little.

The change in tone, permitted through the intervention of the Key’s satire, allows Obama to express internal frustrations on the lack of action on climate change in a performative and challenging way.

LUTHER: You got mosquitoes, sweaty people on the trains stinking it up. It’s just nasty!

OBAMA: I mean, look at what’s happening right now. Every serious scientist says we need to act. The Pentagon says it’s a national security risk. Miami floods on a sunny day and instead of doing anything about it, we’ve got elected officials throwing snowballs in the Senate.

LUTHER: Okay, I think they got it, bro.Footnote 61

This example encourages us to query how modalities of voice and tone, which are also shaped by class, gender, and race may limit what can be said and expressed in formal political engagements.

Space

‘Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’ also comments on the question of space, and appropriate locations for diplomatic conversations. It invites critical thinking on where diplomatic conversations usually take place, and how questions of location might control what can be said. In one of the scenes the EU diplomat is invited to sit outside a Gazan bakery, on the curb side. A queue grows behind them after the assassination of Ahmed al-Jabari by an Israeli drone attack on 14 November 2012 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Slide from ‘Politics in Drag: Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’. Photograph: Author, Gaza, 22 November 2012.

The citing of this actual event comments on the difference in experience between the Palestinian diplomat and the European diplomat. They are not comparable. This point must be emphasised. If diplomatic practices are intended to mediate estrangement, to turn different experiences into a common language or common practice, the performative act of the drag performance reminds us of the difficulty or impossibility of this mediation. The EU diplomat does not face war, the fear of assassination, or physical or diplomatic sanction. The performance reminds us of this divergence. The positioning of the diplomatic conversation within Gaza, during an Israeli air raid and on a curb outside a Gazan bakery shifts the site for a normal diplomatic conversation.

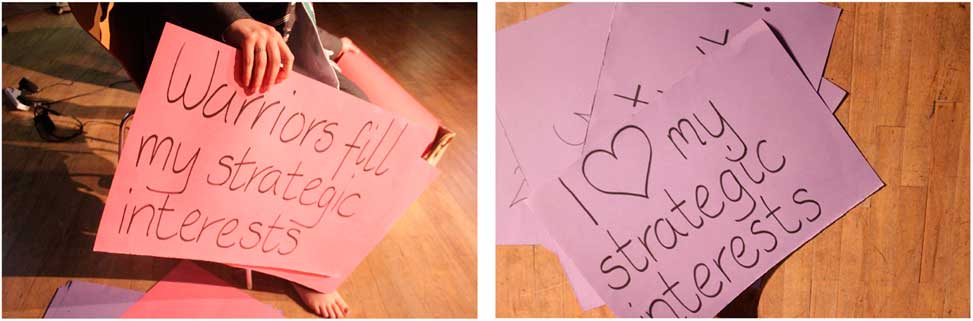

Scene Four returns to a more ‘normal’ ‘diplomatic’ location – the European Parliament. It goes to the real location of the: ‘Tractor Café’, where the seats are made of recycled metal; that’s nice, isn’t it. I comment that Hamas leaders had attempted to travel to Brussels to meet with European leaders in the past but that they had been barred entry. But this time (in the fictional space of the performance) Hamas leaders have been invited to sit down with EU representatives to discuss the outcome of the elections; what a good idea. In this scene, I interweave recordings of several interviews with hyperbolic words printed on colourful cards and gestures to interrupt the exchange (Figure 3). The interruption of the work of drag draws our attention to the political possibilities that were barred from the realm of possible action because of an anxious attachment to a ritualised idea of strategic action.

Figure 3 ‘Politics in Drag: Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’, 23 May 2014. Photographer: Hannah Mann.

Many senior EU leaders confessed dismay with the policies of their governments, or the EU’s no-contact policy with Hamas. They argued that discouraging diplomatic engagement meant there was no way to judge whether Hamas had abided by the conditions or not. The EU’s no contact policy risked further marginalising Hamas, rather than responding constructively to its decision to participate in the electoral process. The hyperbolic gestures of the performance query what is lost in the anxious attachment to a narrative of strategic thinking, that I argue limited the possibility of creativity or risk taking in politics. Again it points to what is lost or barred from the realm of possible action in this desire to perform ‘strategically’.

Drag as a method of critique

Drag performance has a history of being subversive, not only in its relationship to gender, but also its relationship to other identities, such as race and class, and other political proclivities.Footnote 62 Drag performance has been used by minoritarian subjects as a tool of disidentification, explains José Esteban Muñoz. ‘Disidentification resists the interpellating call of ideology that fixes a subject within the state power apparatus.’Footnote 63 Queer performance and drag tactics can allow us rethink questions of time, progress, and community. Normative cultural and social boundaries that have been taken as fixed become malleable.Footnote 64 The objective of the drag artist is not to pass as the opposite gender, but rather to disturb the taxonomies, categories, and binaries that discipline and frustrate the proliferation of different gender expressions. Muñoz cites Felix Guttari’s discussion on the ‘potential political power of drag’ in the militant theatre production, Mirabelles.

They resort to drag, song, mime, dance, etc., not as different ways of illustrating a theme, to ‘change the ideas’ of the spectators, but in order to trouble them, to stir up uncertain desire-zones that they always more or less refuse to explore. The question is no longer whether one will play feminine against masculine or the reverse, but to make bodies, as they break away from representations and restraints on the ‘social body’.Footnote 65

In drag performances that are more overt with their politics, ‘not passing’ is often used as clever strategy of resistance; they disturb the coherency, homogeneity, conformity, and uniformity. Weber writes on the performance of Conchita Wurst in the 2014 Eurovision Song Contest, whose various iterations of non-passing disturb the boundaries of legitimacy and acceptability in international politics. The bearded lady defies expectations – to defy openly and resolutely the borders and boundaries between sex, gender, and sexualised authority. Rather than trying to pass, as (hyper)female, (hyper)feminine, (hyper)heterosexual, Conchita Wurst is s/he who cannot and will not pass as either male or female, masculine or feminine.Footnote 66 Drag artists and drag artists of colour have participated in political campaigns and electoral races to disrupt the orders of normativity that circulate around formal politics and that have attempted to exclude them.

The following sections close in on three methodological provocations of drag performance. These provocations highlight the theoretical and performative grounding of the performance piece, ‘Politics in Drag: Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’. Moreover, these methodological provocations highlight how drag and queer performance can be used as thinking and teaching strategies. Drag can be used as a tool to open up epistemological considerations when approaching political issues. The first methodological provocation is the question of the what if, as an alternative departure point from which to imagine politics. Second, I reflect on the queer politics of refusal performed through drag. Third, I will discuss defamiliarisation, as a theatrical and drag technique of critique.

What if

The production of performance art allowed me to create a fictional space, a space of the ‘what if’ to stage an alternative coming together of the diplomatic figures, Hamas, and the EU. Feminist writing relies on the scripting of alternative futures or of imaginary spaces to re-envision political possibilities in the present. Neta Crawford writes on feminist science fiction, which takes

the givens of our social world(s) and use them as mirror, foil and canvas. Through the imagining of possible world, we may come to understand our own world better, to recognise its historical construction, and to imagine new configurations, possibilities that are not constrained by pre-existing ideas and precedent logics. …Footnote 67

Anna M. Agathangelou and L. H. M. Ling speak of creativity and poisies as a way to imagine an alternative construct of politics beyond the colonial capitalist-patriarchy.Footnote 68 Elina Penttinen writes of shifting away from an ontology of suffering and towards a politics of possibility, by focusing on instances and experiences of success, relief, and positive change in international politics.Footnote 69 Penttinen’s writing on the ability of female peacekeepers to approach their work with professionalism, ethics, mindfulness, and respectful relationships provides a map for learning and growth. These feminist interventions emphasise the need for alternative departure points, such as creativity, imagination, fiction, or mindfulness from which to reinvigorate political critique and the building of community.

Butler discusses the importance of the alternative imaginary space in Hannah Arendt’s piece, Eichmann in Jerusalem, in which Arendt invokes an ‘ideal judge’ to fashion ‘possibilities of political belonging that do not rely on established forms of individualism’.Footnote 70 The question of the ‘what if’ provides an alternative departure point from which to think about politics: what if politics looked like this instead? Rather, than beginning from a place of subjugation, oppression, and marginalisation the alternative ontological arrangement begins from a place of hope, community, and justice. In Butler’s reading of Mahmoud Darwish’s poems, the questions of the ‘not yet’ or the ‘what if’ are very present. ‘[These] questions seek to open up a future under the conditions in which the future has been foreclosed or in which the future can only be thought as repeated subjugation.’Footnote 71 The objective is to think of a political future that does not repeat a discourse of colonial subjugation, or a future that is not already closed down by an existing discourse of threat. In an endeavour to rethink co-existence between Israelis and Palestinians from the departure point of the shared experience of the refugee, Butler writes: ‘Exile is the name of separation, but alliance is found precisely there, not yet in a place, in a place that was and is and in the impossible place of the not yet happening now.’Footnote 72

Queer artistic practices reconfigure ideas around community, love, and belonging. The contemporary music of Janelle Monáe is drag, androgynous, and queer, and may be described in the genre of Afrofuturism.Footnote 73 Monáe’s album Dirty Computer articulates important tropes of black resistance and liberation, but also emphasises that these movements were not inclusive of alternative iterations of gender and sexuality. Adrienne Brown writes that Monáe’s work celebrates diverse sexual experience and love. It foregrounds intimacy between black women, and offers a reading of pussy-power that is tender, intimate, and playful.

Huey Newton’s trademark wicker chair is transposed into a white floral throne, while Monáe wears tailored suits that evoke the Nation of Islam, now paired with white leather stiletto boots. The video essentially fuses the Nation of Islam with Rhythm Nation, as Monáe both attends to and exceeds the contours of the masculinist fantasia that is commonly taken as the black revolutionary imagination in popular culture.Footnote 74

Monáe’s work may ultimately give voice to a broader vision of justice or equality than articulated by predecessors in the civil rights movements, argues Brown. It sends as a message of black feminist collectivity in order to decentralise conventions of love, family, and respectability.Footnote 75

In the space of the ‘what if’, imaginations are allowed to reconstitute forms of community and belonging. My performance piece presents an alternative coming together between Hamas and the EU. Performance art challenges the teleological boundaries of what might be possible in politics. In this way, the performance space acts as an experimental, provocative, and performative space that presents political conversations, which did not occur but which could occur.

This fiction will be that which exceeds the established framework for understanding reality; it will exceed established modes of rule and precedent, social facts, and challenge the limits of established ontology.Footnote 76

In presenting an alternative ontological arrangement through live art, drag performance as a method of critique contributes to conversations on alternative departure points. What if Hamas and the EU had met following the elections, what might they have said? This question, I argue invites a creativity in our response, as academics and political thinkers to a pervious political ‘impasse’. It permits considering an alternative political arrangement; one that does not begin from the place of an anxious attachment to a form of strategic thinking under which the possibility of such a conversation had been excluded.

Near to the end of some of my interviews in Gaza I would ask the fictional or hypothetical questions, ‘What if you were invited to Brussels to meet with an EU representative, what would you say?’ or ‘What if the EU had decided to respect the election result, what would life be like?’ These were always bizarre and happy questions and responses. A smile or smirk appeared. There is a sense of hope or creativity that is performatively uttered through the imaginative questions. The responses were always filled with a desire for positive change, as well as a certain amount of sadness for what did not occur.

Jamil al-Khalidi, head of the Central Elections Commission for Gaza responded,

I believe if the Europeans particularly dealt with Hamas as a winner in the elections, or if they accepted the coalition government that included ministers from Hamas and Fatah, I think this was a precious opportunity that the EU had foregone. And if this had happened, it would have been possible to reach common grounds between the Europeans and the coalition government that included Hamas. This would have saved the region lots of troubles and it could have been possible to reach at least an interim solution that can be the beginning to a comprehensive solution.Footnote 77

Huda Naim, Head of Women’s issues, Hamas leader responded,

A nice picture. The people would not be suffering as much as they are suffering now. The people would also believe that the Europeans really believe in democracy. We are not saying that the EU are one whole, there are different positions. But in this position to turn their back on us and on democracy they were one whole.Footnote 78

The fictional question pushes the conversation into an alternative reality, one that is perhaps less conditioned by the hegemonic practices that had structured the diplomatic exchange previously. The performance space, or the space of the fiction allows for such creativity.

Refusal

The second methodological provocation of drag is its politics of refusal, which presents a distinct critique of dominant political arrangements. Rather, than placing itself in opposition to dominant discourses, it practices what Halberstam has called a ‘politics of refusal’. In Female Masculinity, Halbserstam tells a story of masculinity by investigating how it is practiced, performed, and how it exits through female masculinity. ‘Such affirmations’, argues Halberstam, ‘begin not by subverting masculine power or taking up a position against masculine power, but by turning a blind eye to conventional masculinities and refusing to engage’.Footnote 79 The provocation is not to ask to be accepted within the normative boundaries of existing gender configurations. Drag performance embodies a queer refusal to be read, explained, or undone according to dominant regimes of intelligibility.

Butler and Athanasiou have called this a reluctance to be invited in by liberal regimes of intelligibility.Footnote 80 They discuss queer resistance against being asked for acceptance by the regimes of intelligibility that had marked alternative forms of being as perverse in the first instance. In this effort Butler and Athanasiou point to an unsettling of the norms that already exist to demarcate the normal; as such the objective is to disturb ‘the normalizing power of both the law and kinship as always already heteronormative’.Footnote 81 Athanasiou proclaims that the task is not to demand ‘that liberalism open up its horizon of encompassment and live up to its promises and ideals, but rather to allow for the possibility of exposing the regulatory forces that cohere and sustain these ideals’.Footnote 82 In working out this problématique and the possibilities within it, the authors explore the space for radical strategies of resignification and subversion.

Gender and performance scholars and artists Moe Meyer and L. M. Bogad both discuss the politics of refusal in the drag artist Joan Jett Blakk’s running in Chicago’s mayoral race. Joan Jett Blakk, a fabulous black drag artist, was the first official Queer Nation candidate. Ms Blakk’s slogan was ‘Putting the Camp into Campaign’. Jett Blakk does not try to conceal her bulge; there is a celebration of difference. ‘I’m not trying to be a girl’, he says, ‘but I do like the in-your-faceness of being a man in a dress, stomping on that line between male and female and erasing it.’Footnote 83 Blakk’s drag performance accentuates who is normally allowed to speak politics, drawing further attention to class and race in the performance. S/he is not trying to inhabit the ‘refined’ politician, but rather use his/her body and signs of class to disrupt the coherence of those who normally belong. Jett Blakk occupies the roles and rituals of the campaign, parodying politicians and political activity. Ignored by the press during the campaign, Blakk would ‘infiltrate’ official events. In one occasion she joins the reception line in a Democratic Party fundraiser dinner, and participates in the hand-shaking ritual procession.Footnote 84

Electoral guerrilla theatre, explains Bogard, aims to subvert the normalised practices of electoral procedures and hierarchies. For the activists and performers who partake in these subversive and activist processes, fully belonging or winning office is rarely the primary goal. Rather, these campaigns aim is to ‘simultaneously corrode and rejuvenate’ elements of civil society. Through such parodic public performance, marginalised, resource-poor groups may incisively desacralise and satirise the electoral ritual: a ritual that they feel effectively and unadmittedly denies them the option of earnest participation.Footnote 85 The aim therefore is not to pass and win, but rather, to act as a critique on what counts as winning. The tactics are playful and creative.

Drag performances are aligned with the genre of political satire, which inhabits cultural and political codes and stereotypes in order to subvert them. In the comedy tour, The Muslims are Coming!, for example, the comics visit various locations in the US and present their routines as a way to inhabit and make fun of the stereotypes that are currently used to decipher and control the Muslim Other. Drag, satire, and the use of humour can invigorate political discussion, but they are not necessarily inclusive, and questions of audience and the scripting of new exclusions should be considered. The Obama impersonation sketches by Key and Peele discussed above may be more inclusive to some marginalised communities. However, Orientalist tropes, such as the sketches’ treatment of Iran, and the heralding of the US as the world’s policeman are maintained. Weber critiqued The Onion’s satirical depiction of a fallen Trump supporter who is ‘saved’ through finding Butler’s Gender Trouble and other queer feminist work. Identities are hardened rather than subverted here. Weber argues that humour is weaponised as a defence mechanism in the arsenal of anti-genderism and right-wing populism.Footnote 86 It maintains an imagined unbridgeable gap between the caricatures of the ‘Real US American’ as a clichéd, middle-aged and working-class white male, and queer feminists as being ivory tower intellectuals, out of touch with reality. Weber stresses that such Othering and reproduction of populist depictions also works to discredit the social critiques presented by queer feminists and queer feminists of colour.Footnote 87

Defamiliarisation

The last methodological provocation of drag is the performative effect of estrangement or defamiliarisation, whereby the performance challenges the audience to question certain social, cultural, and political structures and norms that had been taken for granted, unnoticed, or normalised. Drag as a strategy and/or a performative act works as estrangement, whereby taken for granted regimes are exposed. The author’s drag performance discussed above undercuts the coherence of diplomatic or high-level political performances, and displays their performative underbelly. ‘As a technique of estrangement, drag denounces that which dominant ideology presents as natural, normal, and inescapable, without always offering another truth.’Footnote 88 Various performance theorists discuss the Brechtian theatrical techniques laden within drag, which push the use of estrangement to invite audience members to question their own reproductions of power and class. Audience members can include other IR academics who might be distanced from how they view their own reproduction of knowledge. It can be EU leaders who are estranged from their own diplomatic practices.

Brechtian techniques of estrangement challenge the perceptions and privileges of those who would mistake appearances for essence. ‘Dedicated to defamiliarising and historicizing social roles assumed to be natural and hence immutable.’Footnote 89 ‘Aesthetic pleasure for Brecht consists in art’s propensity to render ordinary, natural and familiar things strange, unique and extraordinary, so that they may be questioned and changed.’Footnote 90

According to Meyer,

What made [Jett Blakk] actions camp was not that she wore a dress, but that she wore the dress in public. Her drag was not a parody of gender, but a parody of politicians accomplished by using drag as a defamiliarization device. More closely aligned to Brechtian theories of theatre than to gender masquerade, Blakk saw drag as a mode of distanciation with the ability to undermine the reification of social roles, not just social gender roles but those of race, class, and national identity as well.Footnote 91

Drag as a methodological practice critiques normalised politics and their ritualised performances. It has the ability to show diplomatic sites as constructed as masculine, heteronormative and white, but in a way that does not idealise or reify these sites. Vaginal Davis’s work, for example, inhabits racist, misogynist, and homophobic narratives, and through drag she stretches, distorts, and exposes the way dominant discourses attempt to close down possibilities for being and for being recognised otherwise. Muñoz relays seeing Vaginal Davis on stage: the towering black transgender body (man to woman) is dressed in boy drag; is dressed in military fatigues. In this piece Vaginal Davis inhabits the subject place of the white supremacist male. She declares in a high-pitched shriek that she finds white supremacist militiamen to be really hot, so hot that she decided to dress up as one. Davis’s work exposes the extreme subject formation of the white supremacist and distorts it with the presence of her own black, transgender body. She dramatically takes up the anxieties of the white supremacist male who is attached to his own essentialised recognition of himself as a homophobic, racist, and sexist subject. Davis’s drag inhabits these phobic images in order to perform the homophobia of the white supremacist and to disrupt it

The minoritarian speech does not seek permission for their difference, but rather uses their Otherness to decentre the strength and normality of dominant masculine diplomatic practices. In a contemporary performance piece, Tania El Khoury takes the trope of the fingerprint and offers it new context, in order to make space for empathy towards refugees. The work ‘As Far As My Fingertips Take Me’ inhabits and defamiliarises the fingerprint as a modern method of control.Footnote 92 Using sound and touch, El Khoury creates an intimate scene in order to understand the effects of border discrimination. ‘Our fingerprints facilitate touch and sensations, but are also used by authorities to track many of us.’Footnote 93 Defamiliarising common social, cultural, and political codes through performative practices, such as rearticulating dress, voice, and location can open up towards new political formations and the possibility for more care and community in politics.

Conclusion

This article presented drag performance as a queer method of critique in the field of IR, which contributes to a longstanding move in IR to engage with aesthetics, and a more recent move to engage with performance art. The article discussed the author’s making of a performance piece that revisited the EU’s response to Hamas’s success in the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections, through the tactics and strategies laden in the art of drag performance, such as satirical hyperbole and melancholia. Soft, camp, feminine, and childlike voices; a female body in men’s clothing; and the translocation of bodies in spaces are used in the performance piece to disrupt the coherency of normalised diplomacy. The performance acts as a way to challenge the anxious attachment to a ritualised discourse of strategic interests that I argue controlled the EU’s response to the outcome of the 2006 elections. The performance piece displays the disappointment and sadness that circulated around the decision to sanction the newly elected government and to close down an important moment for change in Palestinian politics.

This article opened questions concerning how rituals around dress, voice, tone, and location shape the kind of political propositions can be made. These social expressions or political artefacts are reminders of what ‘normal’ entails. Public critiques of Corbyn’s clothing for not being statesman-like enough speak to the normality of being ‘represented’ by men in £3,500 suits, not sweaters knitted by their mothers. Teriba also spoke of the liberal anxiety around Corbyn’s feminised passivity; the ‘scary’/abnormal statesman who is unwilling to ‘press the right button’. The article discussed how shifts in Obama’s tone, through the satirical comedians Key and Peele allowed him to express true anger. This queries how politics uttered through the language, tone, voice, and expressions of institutions that have a history of racial oppression may limit what kind of political initiatives can be formed. In my own performance piece, ‘Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’, I used dramatic techniques to change the language and location of politics. How do diplomatic initiatives change when its location shifts from the meeting rooms of the European Parliament to the streets of Gaza when under attack? Does the change in location shape the kind of discussions that can be had? This article emerged from the author’s interviews with EU and Hamas representatives who shared a frustration over the EU politics of sanction and boycott.

I argue that drag is a performative mode of social critique that first, sheds light on the anxieties of passing as normal. Following a psychoanalytic critique, drag performs the interior landscape that is punitively controlled from being publicly expressed. I use drag to show the sentiments that are foreclosed through the performance of strategic interests. Second, through parodying gender and its intersection with race and class, drag makes space for alternative imaginings of political community, progress, and change. This article discussed the interventions of Joan Jett Blakk, Vaginal Davis, and more contemporarily, Janelle Monáe and Tania El Khoury, who inhabit exiting cultural codes in order to reveal how they have been used to exclude or oppress. These practices of drag are methods that make space for difference, while refusing the liberal invitation for acceptance.

This article presented drag as a performative methodological practice that offers an alternative departure point from which to imagine political possibilities, contributing to a feminist tradition in this area. It also embodies the queer practice of refusal and the drag technique of defamiliarisation. It contributes to queer methodological practices that seek to rework binary systems that uphold, and permeate through global politics. Drag uses tactics of ‘not-passing’ to dislodge binary systems of intelligibility that continue to control how global political issues are interpreted and made sense of. Weber’s most recent work on queer methods in IR lays emphasis on the plurality of meaning that can circulate around a single object or subject. Queer research critiques the binary logic of either/or, girl/boy and provides the possibility for recognising plurality and complexity.

Instead, understandings can require us to appreciate how a person or a thing is constituted by and simultaneously embodies multiple, seemingly contradictory meanings that may confuse and confound a simple either/or dichotomy.Footnote 94

Weber’s work is crucial in that it creates space for not knowing, not needing to know, and as such, a resistance against domination through knowing. It politically leaves space for complexity, tensions, and confusions. Butler made this proposal central in Undoing Gender, where explorations of intersex lives were imposed upon by legal, scientific, and sovereign knowleges that claimed to know and did violence through knowing.Footnote 95 Is it possible, therefore not to rush to know those subjects or political events that seem to confound and confuse? How can we move not to fill tensions or contradictions with existing regimes of intelligibility?

The knowing of Hamas as terrorists closed down alternative readings and engagements with the movement. The Palestinian democratic decision became the location of European intervention through disjointed temporary mechanisms and the diversion funds. The colonial response took the shape of conditions, adjudications, and orders. The last sentence of the performance piece, ‘Sipping Toffee with Hamas in Brussels’ is ‘I don’t know.’ It retains the queer politics of refusing knowledge of others and making it permissible, in politics not to know. This critiques the position of the masculine knower of others and the white European knower of Others. In this way, the performance insists on an estrangement that does not need to be mediated.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210518000451

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by the interdisciplinary connections between performance and politics at Aberystwyth University, and the direction of Jenny Edkins. Thank you to Elina Penttinen for reviewing a draft of the piece, and thank you to the reviewers for their supportive and interesting feedback.