Introduction

Why have non-Western powers, such as China, pursued a grand strategy of commercial integration into the liberal system? When rising powers like China, India, and Brazil are considered as a class of states, several important empirical facts jump out. First, these states have not sought to oppose the US or the Western liberal system. The second impressive fact is that all of these states began to pursue policies of commercial integration into the order at roughly the same historical juncture; that is to say, between the late 1970s and early 1990s. Communist China's policy of ‘reform and opening’ began in the late 1970s; in India, though some reform occurred in the mid to late 80s, liberalisation and deregulation began in earnest starting in the early 1990s; in the 1990s Brazil also shifts course, its turn toward ‘modernization and globalization’ was led by a Marxist-sociologist and professor of dependency theory.

But what factors motivated this unexpected shift? Realist theories are not particularly helpful in explaining why states like China oriented themselves toward the West. First, it cannot be seen as an effort to balance, but was China trying to bandwagon? The bandwagon concept is not applicable because alignment did not take place in the military security realm nor was it motivated by an effort to appease an aggressor or make gains from aggression. China's integration has been commercial. Hegemonic stability theory holds greater promise. Ultimately, the theory is not convincing because in the commercial realm the system has been far less hegemonic and more multilateral. In contrast to the Bretton Woods system, ending in the early 1970s, the US no longer sits at the centre of the commercial order but more resembles a giant among lesser equals. Furthermore, commercial integration has been most pronounced at the regional level.

Theories of democratic peace are not helpful in explaining the behaviour of China. The literature predicts increased conflict when democracies perceive rivals as being illiberal. Commercial and institutional theories prove more helpful. For example, commercial liberals argue that China was moved by a basic interest in growing its economy and enhancing national welfare. An interest in modernisation and development is certainly a large part of the explanation. Because of the benefits they provide, functional institutions make integration more attractive and less risky. Commercial and institutional arguments offer plausible accounts of the motives that led rising powers like China to integrate.

While it is true that the institutional order has enabled the integration of rising powers, the argument is incomplete. The standard liberal account of actor motives assumes that states seek to maximise (absolute) gain. This account is incomplete because it ignores competitive pressure operating at the systemic level. Commercial ties among the liberal core – the countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) – have grown to such an extent that powerful network externalities have been triggered. Network externalities are incentives and disincentives created as a by-product of the interaction of multiple actors. Outsiders like China found themselves lagging behind those that successfully integrated into the liberal core. It was not only a desire to improve one's lot, but also a fear of falling behind in the struggle for relative power.

The liberal commercial order provides states with three principal sets of benefits. First, states benefit from increased market access. Many of the emerging economies owe their new found prosperity to export led growth and Western consumers. Second, they benefit from foreign investment and the accompanying transfers of technology and know-how. In search of cheap labour and lax regulation, emerging economies have become prime targets for Western capital. Third, opening up and integration bring competition. This competition has the long term effect of enhancing the overall strength and quality of domestic industries.

The argument unfolds in four stages. First, I will explore the utility of the field's dominant theories in explaining what motivates outside powers to integrate into the liberal system. While realism and constructivism are not particularly helpful, commercial, and institutional liberal theories perform much better. But commercial and institutional theories are incomplete because they ignore the powerful motive of competitive pressure.

Second, I aim to make a contribution to the growing body of literature that seeks to develop a liberal systemic theory of international politics.Footnote 1 I will do so by advancing a novel system-level explanation that gives primacy to the mechanism of competition. Because of network externalities, those on the outside face strong incentives to integrate. States that are integrated into the core face strong incentive to stay in. Those who opt out ultimately fall behind. For the leading powers, economic strength is due in large part to commercial integration. Because power ultimately rests on economic foundations, the leading states are forced to bond so as to be competitive.

Finally, though the intended contribution of this article is theoretical, throughout I will use the case of China to illustrate and support the argument. In a plausibility probe I will explore some of the circumstances surrounding China's decision to join the world, arguing that while competitive pressure was not the only motivating concern, understanding the People's Republic of China (PRC)'s turn westward requires an account of system-level competition.

International Relations theory and the decision to integrate

What are the motives that have led the rising powers, especially illiberal states like China, to integrate into the system's liberal core? Specifically, we are trying to explain the grand strategy of economic integration. Liberal and realist explanations are better at explaining the initial causes of and motives for integration than constructivism. By and large, constructivism builds on liberal and realist explanations about the initial motives that move actors, and focuses on how the process of normative socialisation makes the initial decision stick. They are less concerned with the reasons actors choose a particular road, and more concerned with the way in which the road chosen may fundamentally change the traveller. Realist theories of balancing, bandwagoning, and hegemonic stability hold more promise but fall short. Ultimately, liberal theory most persuasively captures the motives behind integration.

Constructivist theories do not offer much new insight into the reasons that initially motivate states to pursue a strategy of integration. Several examples serve to illustrate the larger pattern. For instance, Adler and Barnett's discussion of the ‘precipitating conditions’ that lead states to orient themselves toward each other include familiar variables like threat, power, and economics.Footnote 2 Alexander Wendt introduces ‘master variables’ that lead to cultural change including interdependence and shared threat.Footnote 3 The constructivist socialisation literature exhibits a common mode of reasoning. In the initial phases of socialisation actors are moved by logics of consequences. They behave according to rational calculations of self-interest. But as norms become internalised and identities change, utility calculation is replaced by logics of appropriateness. At this stage, actors behave according to new understandings of what is ‘right’.Footnote 4 Most constructivist analyses accept strategic and self-interest accounts of motives as developed by liberals and realists; these are said to apply to initial phases of socialisation. The real value added of constructivism is in explaining how identities and interests change through continued interaction.

Constructivism does bring to the fore two important ideas about motives that deserve consideration because they are substantially different from liberal and realist ideas: homogeneity and social identity theory. First, states that share a cultural and normative affinity are said to be more likely to develop a shared identity.Footnote 5 For instance, liberal democratic states may be more inclined to form a security community because they have common characteristics. Interesting as this possibility is, it is not helpful in explaining the behaviour of non-Western, illiberal powers. In the case of China, we are dealing with an entrenched political culture and institutional structure that was in many respects the very antithesis of the one championed by liberal Western powers.

Drawing on social identity theory, Yong Deng and others argue that outsiders aim to achieve greater international status and prestige.Footnote 6 Few governments are as status sensitive as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), both to satisfy nationalists and to reestablish China as a strong and significant power, if not the ‘Middle Kingdom’. But the status explanation is not fully convincing. While status is an important goal, if it were the CCP's greatest priority then we would expect the Party to take meaningful steps toward redressing China's number one image problem: its autocratic political system. China's pariah status, particularly in the years following Tiananmen, resulted from its illiberal political system and poor treatment of minorities and political dissidents. Second, China's commercial relations with pariah states in every region – from Venezuela, Zimbabwe, and Iran to Myanmar – suggests that business is a far higher priority than good standing. Third, China's policy toward Taiwan and other territorial claims in the South China Sea suggest that geopolitical and territorial interests trump status concerns. In the case of China at least, maintaining single party rule, growing the economy, and geopolitical interests consistently override international status concerns. Status is significant, to be sure, but mainly as a welcomed by-product of greater economic and military capability.

Realist theories of actor motives are more plausible but ultimately unconvincing. According to balance of power theory, states can be expected to form balancing coalitions in the face of a greater power or threat. The logic of balancing does not capture China's decision to integrate into the liberal core. Neo-realism predicts the opposite: secondary powers should form a balancing coalition against the US.Footnote 7 It is possible however that China's turn westward grew out of the Sino-Soviet split. Perhaps the PRC was balancing against a weaker power but greater threat in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).Footnote 8 The historical record lends this explanation support. In 1968 Sino-Soviet tensions were rising as the Soviet army amassed along the border; in 1969 a number of skirmishes broke out. Rising tensions were followed by diplomatic breakthroughs between the US and China, culminating in the historic Nixon visit in February 1972. Though China did not seek a formal alliance treaty like the ones it entered with the USSR in 1950 or North Korea in 1961, both the US and China were moved closer by a mutual interest in weakening and isolating the USSR.Footnote 9

While the Soviet threat explanation accounts for Sino-US rapprochement in the early 1970s under Mao, it cannot account for Deng's decision to pursue a grand strategy of commercial integration. China's integration, beginning in the late 1970s, has been commercial. While the PRC worked to isolate the menacing ‘bear’, at no point did it join a formal anti-Soviet military alliance. It is unclear how China's commercial integration can be construed as balancing behaviour. Second, by the late 1980s Sino-Soviet relations had improved dramatically. That Gorbachev visited Beijing in May 1989, and shortly thereafter major arms deals were successfully negotiated, suggests that Sino-Soviet tensions had largely been calmed. What is perhaps most perplexing from a balance of threat perspective is that even as the USSR collapsed, China's integration accelerated.

While the balancing logic fails, at first glance the bandwagoning concept seems more promising. Bandwagoning was originally theorised as the opposite of balancing behaviour.Footnote 10 Bandwagoning behaviour is motivated by one of two reasons: a weaker state's desire to avoid the wrath of a stronger state through appeasement, or profit from another's aggression by sharing the spoils.Footnote 11 The concepts were intended to apply in the security-military context. But like the balance of power, bandwagoning too has fallen victim to a deleterious theoretical dilution.Footnote 12 It has come to describe numerous different behaviours, unrelated to a security imperative or military conflict, in which weaker states gravitate toward stronger ones.Footnote 13 If the military-security understanding of bandwagoning is adopted, it is clear that China is not seeking integration into the US-led Western alliance system. China's integration has taken place in the realm of low politics. In the interest of maintaining conceptual clarity and theoretical coherence, the concept of bandwagoning should not be stretched to include commercial and institutional integration involving fundamentally different behaviours and motives.

The realist logic of unipolarity and hegemonic stability hold the most promise. Wohlforth has shown how unipolarity has important stabilising effects in the military security realm.Footnote 14 Unipolarity explains why there is regional stability in East Asia. It also explains why a balancing strategy is futile given the hegemon's overwhelming advantage. But it does not explain why states like China have chosen a strategy of commercial integration. Autarky, isolation, and hiding are perfectly consistent with a non-balancing strategy. If unipolarity discourages balancing it is not clear how it encourages commercial integration. Earlier arguments about hegemonic stability theory speak to this question more directly.

Hegemonic stability theory explains how cooperative, liberal trading orders are created and maintained by a preponderant power – Great Britain in the nineteenth century and the US in the twentieth.Footnote 15 The hegemon does not eliminate the logic of self-preservation but temporarily creates an environment in which its effects are subdued. Secondary powers are drawn to the order because they can make gains under an arrangement managed by a hegemon. Second, the hegemon solves collective action and enforcement problems that plague cooperation under anarchy. Third, because no one is capable of challenging the order, secondary states are inclined to pursue economic cooperation and exploit public goods provided by the hegemon. Finally, hegemony changes the relative gains logic: because the hegemon feels invincible it is less concerned about relative loss; only when second tier powers appear to be overtaking it does it grow nervous. For their part, secondary powers go along because they are gaining at the expense of the hegemon.

Whether system-wide economic cooperation rests on US preeminence raises two important questions for hegemonic theory: First, how much hegemony is required to maintain cooperation? In the 1970s it indeed appeared that the US-led economic order was crumbling – the symbolic event occurred when Nixon dismantled gold convertibility in 1971. The shrinking of the economic gap between the US and its allies was partly a function of post-war recovery; it was also brought on by the asymmetric nature of the Bretton Woods system.Footnote 16 Of course, an energy crisis and a stagnating US economy made matters worse. During the 1970s and early 80s, protectionist pressures were mounting at a time when US hegemonic leadership was not forthcoming. Many observers thought the global commercial order was on the verge of collapse. Since then, while the US has been the leading player, with a gross domestic product (GDP) that dwarfs every competitor within the international economic order, cooperation has been less hegemonic and increasingly multilateral and symmetric. While America's role as system maintainer and underwriter has become less pronounced, cooperation has accelerated, expanded and deepened. Curiously, even as the US's role has changed from system underwriter to participant; even as it became increasingly intolerant of asymmetric trade and free riding, nevertheless, the order persists and expands. These developments seem peculiar when approached from a hegemonic stability perspective.

Second, from the perspective of hegemonic stability theory the functioning of a world market implies that at its centre sits a powerful hegemon.Footnote 17 Today, the US is not the only centre of economic cooperation. Granted, the US is the biggest player, but multilateral cooperation is most pronounced at the regional level. Institutionalisation, integration, and economic cooperation in Europe have steadily expanded. While less institutionalised, economic cooperation in Asia has also accelerated.Footnote 18 At times the US has played a role, at times it has observed from the sideline. Regional hegemony may explain the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). But since the end of the Cold War, the role US hegemony has played in the evolution of regional economic cooperation elsewhere is not exactly clear.Footnote 19 That cooperation has been most pronounced at the regional level challenges the view that US power is the driver of commercial and institutional integration. In economic affairs, the US is not the epicentre of action, but behaves like a giant among lesser equals. It does not outright dominate the economic game. Because hegemony in the realm of political economy has been less pronounced, it is not a convincing explanation for why rising powers like China were moved to join the capitalist club.

Hegemonic stability theory is helpful in explaining how and why the post-World War II liberal order was created; it is less helpful in explaining its subsequent expansion. The question still remains: what has motivated the commercial integration of outsiders? The most obvious answer is profit, which brings us to liberalism. According to commercial and institutional perspectives, outsiders like China are integrating because they stand to make gains. States are inclined to join institutions because these provide them with numerous functional benefits.Footnote 20 In addition, the Western institutional order is wide and deep and because of institutions it is less threatening.Footnote 21 Institutions attract actors because they serve useful functions. But institutional functions tell us little about motives. Institutions are means, not ends. The underlying assumption among liberals is that states are prosperity seekers who are out to improve welfare. Here is where commercial liberals share common ground with neoliberal institutionalists. Commonly, it has been assumed that states value absolute gains.Footnote 22 This prosperity motive seems to offer a compelling reason why China has pursued integration. As Deng Xiaoping exclaimed, ‘to get rich is glorious’. Simply, the PRC is in the business of growing its economy and enhancing national welfare; international institutions make this more attractive and less risky.

In surveying the field's major schools I do not mean to suggest that other possible motives are off the table. These case specific explanations will be taken up later in the article. For now, the goal is to identify motives that may have general applicability. The above review suggests that the combination of liberal commercial and institutional theory provides the most convincing account of motives. But these arguments are incomplete and must be pushed a step further. In addition to the generic prosperity motive, below I will argue that outsiders have been moved by powerful competitive pressures operating at the systemic level. This argument strengthens existing liberal accounts by demonstrating how actors not only seek gains but are also moved by a fear of falling behind in the contest for relative power. A liberal systemic theory of competitive pressure, first, requires that we give an account of the liberal system.

The liberal system

Recently, liberals have begun to conceive of the international system in Kantian terms.Footnote 23 This rethinking of systemic theory implies that the most salient feature of the international system is not the opposing great power poles, and the security competition among them, as theorised by realism; but rather, as Harrison argues, ‘the international system is now overwhelmingly dominated by a stable core of liberal democratic states …’.Footnote 24 Understanding the system in these terms is increasingly common: it has been called a ‘core’ or ‘great power society’;Footnote 25 it has been described as a ‘great power coalition’;Footnote 26 others refer to it as the liberal ‘Western Order’;Footnote 27 while constructivists call it a ‘liberal security community’.Footnote 28 Efforts to rethink Kant and his idea of a pacific confederation have laid the theoretical foundations for a system-level democratic peace research programme.Footnote 29 This research explores how system-level dynamics including socialisation and spill-over may lead to the extension of the democratic zone of peace.

A liberal systemic theory becomes possible if the assumption of anarchy is replaced with an assumption of confederacy. The assumption of confederacy holds that the system is not dominated by a multitude of antagonistic and opposing great power poles, but rather, a cohesive cluster of liberal democratic, capitalist states. According to Waltzian systemic theory, it is the leading power configuration that conditions the behaviour of the great powers. Liberal systemic theory assumes that it is the leading power confederacy, not uni- or multipolarity, which represents the system's dominant configuration.

Thus far, liberal systemic theory has focused on the democratic peace.Footnote 30 Theorising and research has centered on two related questions: (1) do systemic dynamics lead to the spread of democracy? And (2) is a system with a high concentration of democracies more peaceful?

According to liberal systemic theorists, the system has entered a stage in which socialisation has replaced competition as the dominant systemic dynamic, pushing the international system toward an equilibrium state of peace.Footnote 31 The only problem is that while liberal systemic theory has placed much emphasis on liberal constructivist ideas about socialisation, it has ignored competitive economic dynamics. The mechanism of competition has simply dropped out of the picture. Bringing competitive dynamics back in will greatly enhance the appeal and explanatory power of liberal systemic theory. My argument is not that socialisation effects are irrelevant, but merely, that competitive dynamics are very much at play as well.Footnote 32

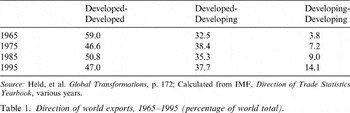

The globalised commercial order develops out of a US-led hegemonic subsystem following World War II. This order grew around a core of leading commercial states (the G-7) and their junior partners (collectively the OECD). Up until very recently, international trade has overwhelmingly revolved around the world's developed economies. In 1970 these states accounted for 75 per cent of world exports; in 1996 70 per cent.Footnote 33Table 1 reveals the stratified nature of world trade:

Table 1. Direction of world exports, 1965–1995 (percentage of world total).

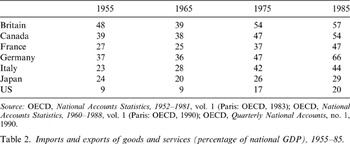

Among the leading commercial states, the volume of imports and exports relative to GDP shows a high and increasing level of interdependence:

Table 2. Imports and exports of goods and services (percentage of national GDP), 1955–85.

Table 2 shows that, for the leading commercial states during the Cold War era, trade has accounted for an increasing percentage of national GDP. When this cluster is examined as a whole, it becomes apparent that it is big with quite striking levels of interdependence. In the post-Cold War era the trend has continued. Between 1991 and 2004, trade-to-GDP ratios for the OECD increased by 11 per cent.Footnote 34

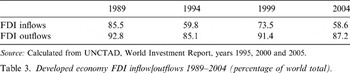

Data on foreign direct investment (FDI) flows reveals a similar pattern. For example, between the years of 1983 and 1988 average annual FDI outflows among the developed countries was over $88.2 billion whereas the average annual outflow among developing countries was about $5.4 billion.Footnote 35

As table 3 shows, a vast majority of the world's FDI outflows come from developed countries and most foreign investment flows from developed countries into other developed countries.Footnote 36

Table 3. Developed economy FDI inflow/outflows 1989–2004 (percentage of world total).

The post-World War II commercial order was created and dominated by the world's leading democratic, capitalist states. This is the liberal system. The liberal commercial system represents a massive gravitational sphere. This totality is big – according to the World Bank, in 2007 the countries of the OECD accounted for 71 per cent of the world's GDP.Footnote 37 Liberals who are inclined to think in systemic terms have largely focused on the question of stability and peace within the liberal order itself with explanations including democracy, international institutions, identity, and economic interdependence.Footnote 38 My contribution is less concerned with the dynamics within the liberal order itself and more with the implications that it has for those on the outside.

A general theory of competitive pressure

Liberal theory tells us that the state's objectives are ‘to improve welfare and the allocation of resources through internal development and trade’.Footnote 39 Realism teaches us that states value relative power capability.Footnote 40 Realism focuses our attention on relative gains and competition while liberalism on absolute gains and cooperation.Footnote 41 While often viewed as contradictory, these assumptions are compatible in at least one important respect: realists and liberals agree that both national welfare and power capability crucially hinge on economic strength.

‘Wealth is power and power is wealth’ is a phrase that rings as true today as it did when Hobbes is said to have first uttered it. Mearsheimer agrees: ‘Great powers also aim to be wealthy – in fact, much wealthier than their rivals, because military power has an economic foundation.’Footnote 42 Though economic strength is by no means the only measure of power, GDP features prominently in most analyses of power.Footnote 43 Regardless of whether one adopts a liberal assumption regarding welfare maximisation or a realist assumption of relative power maximisation the implications for each are the same: states will work to maximise their economic strength. The difference between the two is that for realists the primary motive is security and the game is understood in competitive, even zero-sum terms; whereas liberals emphasise prosperity motives and mutual gains.

Most of the time, but especially during times of peace, it is difficult to gain leverage over the divergent claims realists and liberals make regarding actor motives. This is because most governments must enhance national welfare even as they work to achieve national security objectives. The emphasis on national welfare and security goals is nicely captured by Deng Xiaoping's ‘Four Modernizations’ slogan: agriculture, industry, science and technology, and defense.Footnote 44 For most governments, these goals are interrelated. During some historical periods they were accomplished by purely internal means. In other periods prosperity and power were achieved through imperial thrusts and colonisation. Today, aspiring Great Powers have sought wealth and strength by trying to integrate into the liberal core. Why?

As commercial ties among the OECD countries expanded, this brought into being a massive gravitational sphere. This order became more fully consolidated in the decades following World War II. This consolidation was manifest in three ways: the increase in trade, as well as investment, and the overall economic success of the Western bloc. During the Bretton Woods years, the West experienced extremely rapid growth. In 1948, Western Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan produced a combined $3.7 trillion. The combined output of these countries grew to $12.1 trillion by 1973.Footnote 45 By the 1970s the economic dynamism and dominance of the liberal system was beyond doubt. By roughly the same time, socialism and import substitution industrialisation had largely run their course.Footnote 46 The system became clearly defined by the simultaneous economic success of the West and the failures of the rest.

States are moved by the benefits of inclusion and the costs of being excluded. This has created a curious situation: even those states that have justifiable reason to fear one another – as the US is wary of China's rise – none can actually afford to act on these fears in the ways neo-realism expects. Among states that would otherwise be natural rivals, the logic of self-preservation is subdued because there is a new overriding structural imperative: to be competitive, states must prioritise prosperity over security competition. States on the outside feel the heat: they must find ways to integrate themselves into the dominant liberal economic order, or fall behind. Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore's first prime minister, said it well: ‘Countries that make themselves relevant [to the world] become better off, those who opt out, they suffer.’Footnote 47 This is why outsiders – states like China that continue to be extremely jealous of their sovereignty and harbour suspicions of the outside world – have been willing to make major sacrifices in state autonomy in order to get in.

The reason why a systemic perspective, as opposed to a dyadic logic, is necessary is that systems of multiple actors create ‘network externalities’. Network externalities are incentives and disincentives produced, at times unintentionally, as a by-product of the interactions of multiple actors. Consider for instance how a multitude of PC users creates a network community that disadvantages the lone MAC user, assuming relative incompatibility of the two operating systems. Or, consider how the utility of purchasing a telephone is conditioned by the number of other people who also purchase and use a telephone.Footnote 48 Multiple actors create a reality that cannot be reduced to any single actor or dyad. It is the totality that conditions the behaviour of the part; understanding this requires a systemic perspective.

In international politics, because strategies are conditioned by social environments, what the majority of major powers do collectively often disciplines the competitive strategies each can entertain individually. Once a critical mass or even a few large players adopt a certain course, network externalities may be triggered. These network effects may take a negative or positive form. The greater the number of players joining the network, the greater the benefits derived – the more individuals that use a telephone, the greater the potential utility I derive from owning one. As an outsider, the network's appeal rises in proportion to the benefits of inclusion. The flip side of the coin is that as the utility of inclusion rises, so does the cost of remaining excluded. In a world where relative competitiveness matters, the pressure on excluded outsiders is likely to be acute.

To see how the whole conditions the part, consider two ideal-type worlds, one that is closed and another open. In a system where all pursue autarky and mercantalism, a strategy of liberalisation is dangerous. By lowering tariffs and eliminating barriers to trade, while at the same time tolerating the discriminatory practices of others, a state is likely to experience dramatic losses in relative gains.

No pure cases of such behaviour can really be found, although Great Britain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries pursued a policy of freer trade while tolerating rivals' discriminatory barriers. Similarly, during post-World War II reconstruction the US permitted trade on an asymmetrical basis. Both were hegemonic states. Both paid a price as trading partners were rapidly gaining ground in terms of relative power. Under these conditions, losses in relative gains and competitiveness are unsustainable in the long run even if the state is reaping benefits in absolute terms. In the twenty year period leading up to World War I, Germany's economy grew by 90 per cent, whereas Britain's grew by 56 per cent.Footnote 49 Even though Cobdenite free traders held power in Britain, it was unclear how long it could go on in the face of growing protectionist opposition at home.Footnote 50 Similarly, the US was growing increasingly frustrated with the asymmetrical trading order as its commercial rivals were quickly catching up during the Bretton Woods years.Footnote 51

Conversely, in a system where most pursue liberalisation and open trade, a strategy of isolation and autonomy is likely to be self-defeating as well. The absolute gains from open multilateral cooperation are likely to exceed whatever economic progress a state is able to achieve in isolation. In a multilateral world, the best strategy for a relative gains seeker is to cooperate.Footnote 52 To avoid North Korea's predicament you must pursue strategies adopted by South Korea. Or put differently, a closed state in an open world will experience losses in both absolute and relative gains. In short, the opportunity costs of opting out, whether measured in absolute or relative gains, are substantial in most cases, decisively high in others.

The crucial point here is that these network pressures arise out of the interactions of a multiplicity of commercial powers. A dyadic approach is insufficient because the competitive pressure on outsiders increases in proportion to the number of actors participating and the extent of the commercial interaction among them. To capture these dynamics, a top-down model is necessary.

According to Waltz, states will work to increase their autonomy through autarkic policies designed to enhance self-sufficiency, and by extension security.Footnote 53 The logic works so long as most other states strive for autarky as well. As soon as a critical mass of states develops a cooperative network, outsiders may find themselves at a great disadvantage. The simple reason why unlikely non-Western, illiberal, states have integrated into the liberal core is that they value economic strength and power more than they value their autonomy, and more than they fear the West (or the US). They are responding to the prevailing strategic environment. To opt out of the global commercial order is to forgo three principal benefits: investment, market access, and competition.

If capital movement is highly restricted, as was the case in the 1950s and 1960s, the costs of restricting capital inflows are likely to be less consequential. But if capital is highly mobile, as it has been since the 1970s, closed states forgo the potential benefits of foreign direct investment and the accompanying transfers in technology and know-how. The more states that liberalise capital flows, the more capital there is to go around. These benefits have not only led to liberalisation but have also caused states to compete to attract foreign capital. The OECD countries were the first to liberalise, the rest of the world followed suit as the benefits of attracting the core's capital became increasingly evident. Emerging markets, like China, have become huge targets for investment.

In China, one of the first things Deng did was to create Special Economic Zones in order to attract investment. Internally, states undertake policies to make themselves more attractive to foreign investment and capital – usually by creating an amiable regulatory environment, building infrastructure, and offering protections and incentives to foreign companies. Drawing lessons from China's successful neighbours, Deng clearly understood the value of attracting foreign economic forces:

A special economic zone is a medium for introducing technology, management and knowledge … Through special economic zones we can import foreign technology, obtain knowledge, and learn management, which is also a kind of knowledge. As the base for our open policy, these zones will not only benefit our economy and train people but enhance our nation's influence in the world.Footnote 54

For China this strategy has paid off. Prior to the implementation of reform and opening, capital inflows were nonexistent. FDI inflows surged from about $35 billion in 1995 to $147 billion in 2008.Footnote 55 Roughly 80 per cent of the world's top 500 companies had invested in China by 2004.Footnote 56 Foreign-owned firms accounted for 58 per cent of China's exports in 2005.Footnote 57

Second, an interest in expanding market access has led states to join important multilateral institutions, most prominently the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO itself has expanded because it has successfully expanded market access for member states. The WTO expands trade.Footnote 58 Institutions also increase the flow of foreign direct investment.Footnote 59 The WTO's most-favoured-nation principle illustrates the way in which network effects operate: if a benefit is offered to one member country, it must be given to all. The more members, the more potential benefits each member has access to. Membership in the network is more valuable to the extent that the WTO encourages multilateral and non-discriminatory liberalisation of trade.

Lloyd Gruber has argued persuasively that when institutions are created, strong actors may possess the power to go ahead in creating the institution alone. Once powerful actors make their move, this changes the reality for third parties who may have preferred the preinstitutional status quo.Footnote 60 Gruber's argument is useful in highlighting the ways in which states can be disadvantaged by being excluded from institutions like the WTO. But, because China was a latecomer to the capitalist club, China's reorientation is not an instance of ‘go-it-alone power’. Second, competitive pressure is broader and more diffuse. States are moved by a general fear of falling behind in the Great Power struggle for relative power. Third, the object of explanation here is China's choice of a grand strategy of openness and economic reform. Competitive pressure pushes and pulls actors to adopt particular grand strategies that involve but go beyond membership in specific institutions.

In recent times, most of the so-called emerging economies owe a debt of gratitude to first world consumers, especially Americans. Nowhere has this been truer than in East Asia where development and modernisation have been driven by export led growth. An interest in expanding market access has led China to become an important stakeholder in many commercial institutions. China's involvement in multilateral institutions is well documented.Footnote 61 Recently, China has assumed an active role in the ongoing G20 process, increased institutional cooperation with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), and entered into ‘enhanced engagement’ with the OECD, all of which suggests that China is continuing its policy of institutional cooperation. The single most important milestone in China's economic integration was its 2001 accession into the WTO. China's accession followed fifteen years of protracted negotiations in which the PRC made broad range of difficult and unpopular concessions.Footnote 62 This strategy has paid off: China's exports have expanded dramatically, in large part reflecting increased market access.

Table 4. China's total exports of goods for the years 1984, 2001, 2008 (billions of dollars).

Third, it is strange to think that states would consciously wish to expose their own industries to outside competition. But in an effort to achieve self-sufficiency and home-grown development by shielding domestic industries from potentially harmful outside competition, states stultify long-term innovation, sacrifice economic efficiency, and settle for inferior goods at higher prices. Many states have learned this difficult lesson after sampling the rotten fruit yielded by an overprotected and overregulated economy. China is no exception. Deng Xiaoping was aware of the importance of competition when he opined that ‘Without the market economy, there will be no competition, no comparison, even no science and technology … the quality of our products will always be inferior.’Footnote 63 With a massive, and massively inefficient, state-owned sector – at the height of the command economy China had nearly 400,000 SOEs – China's leaders were acutely aware of the problem. Jiang Zemin called the telecommunications market ‘stiff and ossified’, commenting that ‘it has a bureaucratic style, it goes for industry monopolization, it makes enormous profits but has no concept of providing services. Foreign capital must be brought in.’Footnote 64 When exposed to competition, domestic companies either improve or are eliminated.

States are pulled by the benefits of inclusion; they are also pushed by a fear of falling behind. The liberal theory of competitive pressure is synthetic in this important respect: it combines realist insights about the competitive struggle for relative power with liberal insights about prosperity motives. Whether a state is predominately concerned with gaining relative strength or enhancing national welfare does not matter. In the prevailing strategic environment, there is only one dominant strategy: integrate!

We are accustomed to thinking of competition as a powerful impediment to cooperation. According to neoliberals, cooperation and complex interdependence can succeed in overcoming the harmful competitive tendencies inherent in anarchy. It is counterintuitive to think that instead of pushing them apart, competition in fact pulls states together. Waltz famously explained how ‘States do not willingly place themselves in situations of increased dependence.’Footnote 65 In general he is correct. But in an open system the state is stuck between a rock and a hard place: grudgingly bond and be competitive or cling to your autonomy and ‘fall by the wayside’. The struggle makes for strange bedfellows like the US and China, two states that are rivals in the military-security realm and locked into a commercial relationship that can only be described as mutually assured destitution. It is indeed curious that China's closest trading partners – US, Japan, and Taiwan – are those with whom the PRC has had the most troubled political relations. Though not leading to harmony, the competitive commercial imperative seems to have overridden regional rivalry, historical enmity, and territorial conflict.

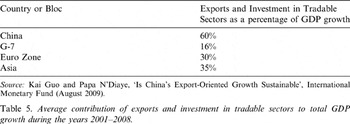

If economic cooperation accounts for a relatively small percentage of a state's economic growth, realists are more justified in ignoring it. This becomes increasingly implausible to the extent that trade and investment are responsible for an increasing percentage of growth. Consider these striking facts: Between the years 1990–2000 the average contribution of exports and investment in tradable sectors accounted for 40 per cent of China's GDP growth. As table 5 shows, during the years 2001–2008 this figure had risen to a dramatic 60 per cent of GDP growth:

Table 5. Average contribution of exports and investment in tradable sectors to total GDP growth during the years 2001–2008.

These figures highlight the impressive extent to which China has been willing to tie itself to the global market – striking for a country whose combined imports and exports were less than $15 billion in 1975. Realists focus on GDP as a measure of power but spend less time investigating how it is that particular Great Powers succeeded in growing their economies in the first place. If Great Powers must secure the foundations of their wealth, is it conceivable that China's interest in a stable and open global economy is not a high priority?

At first glance, my theory seems to parallel familiar liberal arguments that governments have chosen to become more like trading states because they wish to make greater absolute gains. According to Rosecrance, individual states join the trading world in order to enhance national welfare through more efficient allocation of resources and trade.Footnote 66 By the end of the century, Rosecrance was arguing that the post-war trading states – states such as Japan and Germany – were evolving into a new form of ‘virtual state’, epitomised by the likes of Hong Kong.Footnote 67 The rise of the virtual state has ushered in a new era of peaceful forms of international politics. These new forms of political intercourse, Rosecrance theorises, are related to a single causal mechanism: the reduced importance of land and territorial resources as determinants of state power. In short, ‘Mastery of flows is more important than possession of large fixed territorial stocks of resources.’Footnote 68

In The Rise of the Trading State, a state's political orientation – conceptualised in terms of the military and territorial pole on the one hand and the trading pole on the other – largely depends upon the individual state's choice to privilege prosperity over power.Footnote 69 What is missing from Rosecrance's account is precisely that which is provided by a systemic perspective. It is not simply the case that states value prosperity and the absolute gains that can be achieved through institutionalised cooperation; most importantly, states are moved by competitive pressure. The value added of a liberal systemic theory is in explaining how the liberal system has created powerful systemic incentives, network externalities that condition the strategic behaviour of states.

My argument can readily be distinguished from other important works in the globalisation literature. Many have argued that capital mobility is a significant constraining force on state policy.Footnote 70 Others have argued that, at the regional level, states compete in order to attract foreign investment.Footnote 71 Still others have argued that globalisation has created incentives that have caused domestic actors to pressure their governments to liberalise.Footnote 72 The above argument differs from and contributes to this literature in the following three ways: none of this literature puts forth a state-centric Waltzian systemic theory, emphasises the system-level competitive struggle for relative power, nor seeks to explain the decision by rising powers to pursue a grand strategy of commercial integration.

The systemic theory of competitive pressure gains support if it can be shown that unlikely outsiders have pursued a strategy of integration because of a fear of falling behind. Of the system's rising powers, China is the most hotly debated and consequential. In a plausibility probe I will endeavour to show that China's decision to join the world was in great measure (though not exclusively) motivated by competitive pressure. It is important to note, however, that the article claims generalisability that goes beyond China.Footnote 73 The goal of the case is to illustrate the above theoretical argument and lend the theory some empirical plausibility in one large case.Footnote 74

China's decision to join the world

China was a highly unlikely candidate for integration for three principal reasons. First, China has a long tradition of Realpolitik strategic culture.Footnote 75 Thomas Christensen refers to China as the ‘high church’ of Realpolitik thinking.Footnote 76 China's entrenched Maoist heritage certainly predisposed the PRC against any wholesale embrace of commercial liberalism. Second, since the founding of the People's Republic in 1949, China was largely isolated from the world community. Suffering repeated instances of national humiliation at the hands of imperial powers, China has understandably viewed the outside world with great suspicion. Historically, the state has been extremely jealous of and uncompromising in its preservation of national autonomy. Third, since its founding the PRC was a closed, centrally controlled command economy. China's sudden reorientation westward and embrace of commercial liberalism is one of the most peculiar about-faces in world history. In the literature there are a variety of important case specific explanations.

Many scholars find the cause of this reorientation in China's internal politicking.Footnote 77 One explanation is that the reform agenda was a manoeuvre designed to marginalise political enemies, most notably the so called ‘Gang of Four’. A second internal explanation focuses on the national trauma and failed political legacy of Mao Zedong. The disastrous Great Leap and the damaging Cultural Revolution caused disruptions in China's growth and development. These failures, it is believed, help explain the PRC's post-Mao reform track. While these explanations are important, as mono-causal accounts they reveal but a small part of the story.

A post-Mao struggle for power did occur as the ‘Great Helmsman's’ widow, Jiang Qing, allied with other conservatives, attempted to hold on to power by attacking Mao's chosen successor Hua Guofeng. By joining moderate leaders, Hua was able to defeat the Gang of Four. The political infighting explanation is overly simplistic because it does not explain why Deng and his allies were bent on pushing and speeding up reform long after their political enemies had been removed from the picture. China's process of reform and opening has been slow and incremental. The power struggle was short-lived. By 1981 the Gang of Four had been put on trial while Hua had been deposed as Party leader. Deng Xiaoping was in command and reform and opening had barely begun. Clearly, Deng and his allies were motivated by more than just the exigencies of an internal power struggle.

As for the internal crisis explanation, the Great Leap and Cultural Revolution were very serious convulsions. Moderate leaders viewed Mao's great campaigns as failures. During the great cultural purge, Deng himself was deposed and for some time was sent to work on a vegetable farm and a tractor repair plant. These perceived failures may have given momentum to new ideas and contributed to what Legro calls a ‘purpose transition’.Footnote 78 But the internal crisis explanation is not fully convincing because by the late 1970s the economic and political climate had largely stabilised. As Susan Shirk notes, ‘… there was nothing inevitable about Chinese leaders’ move to launch an economic reform drive in late 1978. China was not experiencing an economic crisis, and indeed the economy was operating more efficiently than the Soviet economy.’Footnote 79 While China's command economy was deeply flawed, between 1973 and 1980 China did post a respectable annual average growth rate (per capita) of 3.5 per cent.Footnote 80 If China's statistical bureau is to be believed, in 1977 China's growth rate was 7.8 per cent; increasing to 11.7 per cent in 1978.Footnote 81 While the twin disasters were certainly seared into the memories of individual leaders, if not the collective consciousness of the country, the economic and political situation on the ground was relatively stable. While there were many problems to be sure, reform is puzzling because the leadership faced no ongoing or imminent crises.

China's relative competitiveness was an altogether different story. The competitive pressure explanation is compelling for two principal reasons. First, China's stated goal of modernisation only makes sense in relative terms – what does it mean to be modern? Second, China realised that international competitiveness and long term security demanded that the PRC open its doors and join the world.

The impetus for reform arose from a realisation that the PRC was backward and falling behind. Deng's foreign visits brought China's economic status into keen focus. In 1978 he visited a number of countries including Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and Korea. In January of 1979 he spent a week in the US; later that year he visited Japan. After visiting a Nissan plant in Japan, Deng remarked that ‘today I have learnt what modernization is like’.Footnote 82 Overall, his opinion was solidifying that ‘… China cannot rebuild itself behind closed doors and that it cannot develop in isolation from the rest of the world’.Footnote 83 Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Singapore were all experiencing strong growth in what is now known as the ‘flying geese’ pattern wherein as countries develop and industrialise they move from producing and exporting relatively simple products to more advanced and sophisticated products. Ultimately, the more primitive forms of production move elsewhere in search of cheap labour mainly and spark the process of industrialisation in those new locations. While all of these westward flying geese were looking good, none was more impressive than the leader of the flock: Japan.

Nothing stimulates critical self-reflection like the spectre of a historical enemy who is rising very rapidly. Chinese enmity toward Japan is difficult to exaggerate. While Japan and China fought over Korea in the late-nineteenth century, it is the festering memory of the second Sino-Japanese War that really fuels Chinese nationalism. Japan invaded in 1931 though full-scale carnage did not get underway until 1937 when Japan took Manchuria and moved all the way to Nanking. As the ‘Three Alls’ – burn all, kill all, take all – policy was implemented with ruthless zeal, virtually no one was spared. In Nanking, tens of thousands were slaughtered. But the event is known as the Rape of Nanking because of the tens of thousands of women, of all ages, that were raped. As the cities fell, the horror continued and the number of dead grew. All told, perhaps over two million Chinese were killed. The war capped off a ‘Century of Humiliation’, beginning with the nineteenth century opium wars and ending with the horror of Nanking.

While Hong Kong and Kuomintang led Taiwan's strong growth were an embarrassment to China, Japan's rapid rise was alarming. Indeed, Japan's post-World War II growth was not simply impressive, it was breathtaking. A country that was poorer than Peru in 1950, Japan's economic output grew eightfold in 25 years.Footnote 84

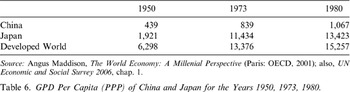

As table 6 illustrates, per capita GDP was rising much more rapidly in Japan than in China. Between 1950 and 1973, Japan's annual growth rate was an impressive 8.1 per cent whereas China was growing at a much slower rate of 2.9 per cent.Footnote 85 The table also shows how by the adopting a strategy of commercial integration, Japan had succeeded in joining the ranks of the world's leading commercial states.

Table 6. GPD Per Capita (PPP) of China and Japan for the Years 1950, 1973, 1980.

Japan's meteoric rise was a long term security threat. The more immediate security concern was the direct threat posed by the USSR and the indirect threat represented by the expansion of the Soviet sphere in Southeast Asia. Deng's diplomatic overtures to the West were an effort to effectuate opening and reform while also isolating the USSR politically. It is important to keep in mind however that from China's perspective, every major power was a problem. In the decades after World War II, China clashed with the US, India, the USSR, and Vietnam. China's short term security interests required it to play a balancing game at various points. However, the PRC's long-term interests could not be secured through a formal treaty alliance. They could only be secured through hard power resting on modern economic foundations. China's alignment behaviour was driven by the necessities of particular security threats; reform and opening was in great part motivated by China's general suspicion of all external powers.

As Deng saw it, the success of others was in great part due to their ability to benefit from a global economy. China's neighbours were getting rich by attracting foreign investment and encouraging exports. As a result of their openness they were modernising very rapidly. China was lagging because she found herself on the outside: ‘Reviewing our history’, Deng explained, ‘we have concluded that one of the most important reasons for China's long years of stagnation and backwardness was its policy of closing the country to outside contact’.Footnote 86 China was lagging because she was backward; she was backward because she was isolated. Isolation would again lead to vulnerability in the way that the Meiji Restoration shifted the balance in Japan's favour in the nineteenth century. During the Century of Humiliation, China's weakness invited interference by the barbarian powers. To be secure China needed to be strong; to be strong China needed to open up, learn, and adapt.

Finally, the manner in which reform proceeded only makes sense if an external perspective is adopted. Quite simply, China adopted strategies that were pioneered years earlier by China's regional neighbours. Many key reforms including agriculture and the creation of Special Economic Zones closely paralleled ones adopted earlier by Taiwan. As a policy course, ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ came to resemble free market capitalism with Taiwanese, Japanese, and Singaporean characteristics. This is a classic case of Waltzian emulation driven by systemic competitive pressures. As a state falling behind in a competitive system, the first thing you do is try to emulate the strategies pioneered by more successful rivals.

In deciding to pursue a grand strategy of commercial integration states, like China, are making a choice. Systemic pressures push and pull but are not deterministic. In adopting a liberal strategy of integration, outsiders are in effect choosing to abandon a nationalist policy of isolation and autarky.Footnote 87 The system confronts individual states as a set of powerful incentives; states, though, must still choose how they will respond to them. These choices often have a self-reinforcing, reproductive, character. In effect, system-level competitive pressures have pushed outsiders like China to make particular choices that set them down a given path. This path is characterised by powerful feedback that reinforces the initial strategic decision, but perhaps more importantly, may ultimately lead to cultural change and normative socialisation.Footnote 88

Conclusion: rethinking system structure

In neo-realist thinking, the distribution of capability allows us to identify the system's dominant configuration. This is a positional picture. But how is the liberal system to be understood? Is it a separate actor or an entity that exists only by virtue of unconstrained state agency? It is neither. While it is not a political amalgamation in the way a federal union is, neither is it an ephemeral configuration like an alliance. It is not a kind of hierarchy nor is it accurately described as an ungoverned anarchy. To get an accurate distributional picture, the singularity of this cluster must be recognised while still understanding that it is comprised of semi-autonomous agents. But doesn't this move violate a basic principle of structural theory?

Poles are represented by great powers; polarity is determined by counting the number of poles. But counting poles makes sense only if the nature of their interaction is assumed to be one of opposition and conflict. Expanding commercial ties have changed the game. It matters less whether there are one, two, or five trucks on the freeway if they're all moving in the same direction. If each is charting its own course it makes sense to count them separately; if they're all on the same road it makes more sense to focus on the ‘highway’. The aggregate force resides not only in its individual members and their actions, but more significantly, the combination of their interaction.

To say that there is a ‘highway’ or ‘network’ is not to say that the liberal core represents a unitary actor; or an arrangement in which ‘other regarding’ behaviour is the dominant norm. It is not to say that liberal states always see eye to eye, in the same way that a Hobbesian ‘state of war’ does not imply that states are in a continuous state of armed conflict. Nor is it to say that geopolitical and territorial security questions have become irrelevant. It is merely to say that leading power commercial ties have created a new politico-economic reality in which the low politics have become the new high politics – the game now unfolds in the shadow of intense commercial rivalry.

But is this network now the dominant structural feature of the international system? If structure, as cause, is primarily understood in terms of its effects, then the answer is yes. Above, I have endeavoured to show that the logic of security competition has been replaced by a more powerful logic of commercial competition. There is still a struggle for power and status, to be sure, but competition is having the effect of bringing states together, not pushing them apart. The implication is not small: the primary structural effect of anarchy has been reversed.

Presently, we are looking at a system-structure of confederacy, lying somewhere on a continuum between the ordering principles of anarchy and hierarchy. As with Durkheim's ‘organic solidarity’, the structure is primarily defined by mutual dependence and a division of labour, only secondarily by institutional and ideational ties.Footnote 89 In this confederate system, semi-autonomous units are tied together through strong commercial bonds and weak and decentralised functional institutions that facilitate cooperation. Because the state's primary goal is to grow wealth and power, and because commercial integration has proven the most successful means to achieve that end, it is not surprising that non-Western rising powers are integrating as they evolve into trading states.

The system is stable and enduring because the self-interest of the part is tied to the continued viability of the whole. The rising power's incentive to revise, and the declining power's incentive to launch a preventative war are nullified by an overriding structural logic that effectively links the fundamental interest of each to a commercial order that none fully controls. In this way, the leading powers have created an informal social structure that arises out of their interactions and tends toward its own reproduction and expansion.