Introduction

How are governing actors in international politics legitimised? From prior research, we know that legitimacy matters for a diverse set of actors ranging from states to international institutions to rebel groups. Legitimacy increases compliance with governance,Footnote 1 fosters an entity’s acceptance and support,Footnote 2 drives institutional changeFootnote 3 and renders governance more stable and efficient.Footnote 4 In the wake of recent contestations challenging the legitimacy of many global governance institutions, International Relations (IR) scholarship has increasingly theorised the processes of (de)legitimation. These scholars have shown that successful legitimation hinges on the utilisation of specific ‘sources of legitimacy’, most importantly specific governance procedures or performance, which ensure legitimate and stable governance if they resonate with a given audience.Footnote 5

However, surveying some examples of recent (de)legitimation processes of governing actors in international politics highlights that the ‘sources of legitimacy’ (SOL) model still misses out on some of the intricacies and contextual underpinnings of (de)legitimation processes within complex governance contexts of international politics. With some notable expectations, the approach builds on pre-specified categories of sources and treats change in actors’ expectations as exogenous to its models. For example, when the Trump administration contested the legitimacy of the World Trade Organization (WTO), they criticised the very idea of multilateral trade rather than the institution’s procedures and performance.Footnote 6 Going back historically, when non-aligned states met in Bandung in 1955, they sought to carve out their own conception of what legitimate international cooperation could look like, markedly different from the pillars and procedures the liberal international order was built on.Footnote 7 When NATO sought to establish legitimate governance in Afghanistan in the 2000s, any procedures and output NATO put forward were mediated by perceptions of foreignness and imperialism as well as the actions taken by the Afghan state and the Taliban insurgency – to detrimental effect.Footnote 8 Thus, when dealing with multiple audiences, someone’s source of legitimacy might be someone else’s source of illegitimacy.Footnote 9 Furthermore, expectations as to what legitimate governance entails might often be at odds with the standard liberal focus on procedures and output.Footnote 10 Finally, these expectations may even change as audiences in international politics are exposed to the legitimation efforts of various actors, compare them against each other, and possibly alter their beliefs.Footnote 11

The limits in existing scholarship to fully spell out the implications of legitimation in complex governance contexts are of concern if we want to understand why governing institutions gain or retain legitimacy over time within international politics. Because a significant amount of established legitimacy theory was originally crafted for use in state-based societies with strong centralised governance structures, there remains a noticeable gap in explaining important puzzles of legitimation research: how can we study legitimation within the diverse contexts that make up international politics without a prior theoretical idea of what potential sources of legitimacy may be? How do processes of legitimation shape actors’ and audiences’ ideas about what constitutes rightful rule? In what ways are these endogenous dynamics of legitimation caught up within the broader network dynamics of international politics? Finding answers to such questions can not only strengthen our empirical grasp on capturing and tracing processes of legitimation over time but also help us identify its effects on institutions, audiences, and the broader organisational environment they are in.

To address this concern, this article engages in a theoretical exercise using insights from relational theoryFootnote 12 to review existing models of legitimation, but more importantly, to offer new ways of conceptualising legitimation which account for the complexities of international politics. While most authors working with SOL models will concur that legitimation is relational,Footnote 13 and recent studies have taken this further to incorporate the relevance of larger social structures,Footnote 14 I argue that they do not take its relationality far enough. Constellations of complex governance make necessary an analytical focus that considers audiences’ expectations as embedded in governance networks and allows for change of such expectations endogenous to legitimation processes.

Thus, I hold that the synthesis of the SOL literature with relational theory allows me to emphasise the endogenous dynamics of processes of legitimation and the causal mechanisms undergirding legitimation: I describe legitimation as a contestation over the normative expectations about governance of a governing actor (the governance provider) and of an audience (the governance taker). I identify four heuristic categories of normative expectations relevant for legitimation, the sum of which I call legitimation patterns: formal and informal rules, sources of authority, common goods, and modes of consent. (De)legitimation, I argue, can be described as a process of congruence-finding, where actors evaluate the discursive and material manifestations of their governance relation to see whether they meet their normative expectations. The degree of congruence between the legitimation patterns of a governance provider and a governance taker will shape governance actions within the relation, with more congruence giving rise to stabler governance practices. Legitimation patterns may change endogenously to legitimation dynamics via cognitive and relational mechanisms that alter a governance relation towards greater or lesser congruence.

The theory advanced here contributes to the study of legitimation within international politics both on a theoretical as well as methodological level. First, it builds on studies seeking to investigate legitimation across the varied contexts of international politics.Footnote 15 Avoiding a normative background theory with a reliance on pre-specified taxonomies of legitimacy sources, the model identifies ways to put actors’ relationally grounded expectations centre stage. This allows us to reconcile the diversity of expectations of rightful governance within international politics with recent advances in the SOL literature. Second, the theory builds on recent studies embedding legitimation in larger social structuresFootnote 16 to provide an improved framework for understanding change in the legitimacy of institutions over time. It does so by taking into consideration the endogenous dynamics of legitimation and conceptualising expectations regarding rightful governance as patterns that spread and change through networks via a range of mechanisms. Third, the theory expands on work emphasising the procedural nature of legitimationFootnote 17 by theorising legitimation as a mechanistic process that both shapes and is shaped by actors engaged in governance relations.

The article develops this relational-procedural theory of legitimation in four steps. First, I take stock of the existing literature on legitimation in international relations and particularly the ‘sources of legitimacy’ approach. Second, I highlight the conceptual weaknesses of this approach in light of insights from relational theory. Third, I synthesise these literatures to provide an alternative model of legitimation as congruence-finding. Finally, the article discusses the theory’s implications and gives concluding remarks.

Legitimacy and legitimation in international relations

Legitimacy has proven a useful concept within IR theory to make sense of dynamics of compliance and support for governing actors within international politics. With Weber’s conceptualisation of legitimate authority as its starting point, scholars have defined legitimacy as the belief among a given group that a rule ‘ought to be obeyed’.Footnote 18 They consider it one possible base for creating order and compliance with political authority next to coercion and material incentivisation.Footnote 19 Thus, IR scholarship has explored questions of legitimacy to explain under what conditions governing actors within international politics such as international institutions maintain support and compliance among both states and broader publics given the backdrop of anarchy and an absence of coercive mechanisms available to many of these actors.Footnote 20

But how do governing actors become legitimate? While some IR scholarship has dealt in normative reasoning to identify standards of legitimate rule,Footnote 21 most have adopted an empirical lens to study legitimation, that is the process of how given audiences come to see certain ruling bodies as appropriate. Originally, scholars analysed legitimation mostly in the context of state governance.Footnote 22 Subsequently, they started to investigate legitimation beyond the state, most importantly in relation to international organisations (IOs),Footnote 23 supranational organisations such as the European Union (EU),Footnote 24 and sub-state actors such as rebel groups.Footnote 25

To model this process of legitimation, a prolific literature has adopted – both explicitly or implicitly – what I will call the ‘sources of legitimacy’ (SOL) model. The model has its foundations in two theoretical assumptions. First, it assumes legitimacy to stem from a congruence between a governing actor’s characteristics and an audience’s social values, their ‘normative benchmarks’.Footnote 26 This is mirrored not least in Suchman’s widely cited definition of legitimacy as a ‘generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions’.Footnote 27 Second, the model follows Scharpf’s dichotomy of input and output (or performance and procedure) legitimacy.Footnote 28 If an institution’s performance and procedures fit the expectations of a given audience, this institution will be seen as legitimate and consequently supported by this audience.Footnote 29 Scholars have debated whether performance or procedures better predict legitimacy beliefs,Footnote 30 but it has become generally accepted that both are highly relevant to explain (il)legitimate governance.Footnote 31

In recent years, scholars have gone beyond this original formulation of the model to increasingly theorise the implications of complex governance for the process of legitimation. Some scholars have analysed how sources of legitimacy are shaped by discursive and behavioural practices of governing actors and how these narratives achieve resonance with a given audience.Footnote 32 Steffek has emphasised the importance of governing actors achieving a discursive consensus about scope, principles, and procedures themselves,Footnote 33 while Tallberg and Zürn have argued that the perception of sources of legitimacy is mediated by a variety of actors framing the IO’s material features positively or negatively.Footnote 34 Similarly, Binder and Heupel survey how states frame the United Nations (UN) Security Council’s procedures and performance to assess its legitimacy.Footnote 35

Other scholars have centred on the relationship between sources of legitimacy and audiences’ perceptions. Taking a closer look at the micro-foundations of people’s perception, Lenz and Viola have noted that audiences perceive sources of legitimacy always through cognitive schemes.Footnote 36 In turn, Scholte has centred on the macro-foundations of the SOL model, rooting sources of legitimacy in larger social structures which are theorised to give meaning to and make thinkable certain sources of legitimacy in the first place.Footnote 37

Again, others have started to tackle the basic assumption within the SOL model of governing actors seeking to strategically achieve a fit between sources of legitimacy and a given audience’s expectations. Bexell et al. have noted that governing bodies in international politics are hardly unitary actors and that different administrative units may target different audiences in their legitimation attempts.Footnote 38 More fundamentally, Lenz and Söderbaum have argued that next to strategic behaviour, legitimation attempts by governing actors might also stem from their own moral convictions or the broader institutional environment which stipulates certain modes of legitimation.Footnote 39

In sum, the SOL model and its various extensions have been able to significantly contribute to our understanding of the legitimation of governing actors in international politics, and the role of discourse, perceptions, and larger social structures therein. They have helped us to better conceptualise global governance, dynamics of support and compliance, and institutional change. Specifically, the SOL model has been effective in comparing on what bases elites or broader publics see a given institution as legitimate.Footnote 40 It has made important headway in our understanding of legitimate rule in international politics by providing a parsimonious cause–effect model of legitimation. However, in the next section, I use insights from relational theory to argue that the literature remains limited in theorising change and variation in the legitimacy of governing actors within international politics over time because it relies on pre-specified sources of legitimacy and treats change in audiences’ expectations as exogenous to its model.

Beyond ‘sources of legitimacy’

Recent explorations of relationalism, which have become increasingly prominent within IR,Footnote 41 have alerted us to the need to consider actors and international politics more broadly as embedded in and shaped by ever-shifting dynamic networks of governance.Footnote 42 Although proponents of this theoretical tradition widely differ in their commitments, they build on three main assumptions which are applicable across meta-theoretical outlooks.Footnote 43 First, relational theory emphasises interrelatedness, arguing that social actors such as states, international organisations, or citizens cannot be considered isolated entities but need to be theorised as inherently interlinked with various other social actors. Meaning and significance thus arise from the relational context in which entities are situated, highlighting the importance of considering the social world along networks of interactions. Second, relational theory foregrounds mutual influence, in that social actors’ characteristics and behaviours are seen as shaped by their interactions within complex webs of relations. Third, relational theory places an emphasis on procedural change. It holds that entities continually change and evolve through their interactions in relation to one another.Footnote 44

We can learn from relational scholarship about the conceptual interventions necessary to analyse legitimation within international politics. Certainly, the SOL model concurs that legitimation is a relational process in the sense that relevant social action – such as the legitimation of an IO – is theorised as taking place among entities: the legitimacy-seeker, employing its sources of legitimacy; and the legitimacy-giver, evaluating them.Footnote 45 Legitimacy, then, is a relational characteristic which cannot describe an actor, but only ever a relation between two actors.Footnote 46 In recent years, some scholars have further conceptualised this relationality of legitimation by theorising how ruler–ruled relations are embedded in wider social structures.Footnote 47 However, as I will argue below, the ‘sources of legitimacy’ approach remains limited in theorising change and variation in the legitimacy of governing actors within international politics due to two analytical shortcomings: a reliance on pre-specified sources of legitimacy and an understanding of change in audiences’ expectations as exogenous to legitimation.

Synthesising the SOL literature with insights from relational theory, I want to highlight not only where these relational assumptions differ from the SOL model, but also why these disparities matter for addressing the underlying puzzle that motivates research of legitimation within international politics. Notably, I do not advocate here for embracing a full relational ontology, which focuses on the co-constitution of actors through relations.Footnote 48 Rather, my point is that we can learn from relational scholarship about the necessity to put actors’ relationally grounded expectations about rightful governance first and acknowledge the potential for endogenous changes of such beliefs as part of the legitimation processes.

Pre-specified sources

First, the SOL model is marked by a cultural and ideological predisposition or a ‘normative background theory’.Footnote 49 It generally assumes that audiences will look at a governing actor’s procedures and performance to evaluate its legitimacy.Footnote 50 While SOL scholars acknowledge that what specific kind of procedures or performance matters is audience-dependent, recent iterations have still drawn on the dichotomy in their explorations of legitimation.Footnote 51 But even where studies go beyond the dichotomy of procedural and performance-based sources of legitimacy, they remain strongly tied to institutional characteristics rather than what people interpret into them.Footnote 52 To be sure, a broad literature has taken interest in the views of the governed at the international level,Footnote 53 but these insights remain largely separated from those studies investigating legitimation as a process.Footnote 54 In doing so, the literature exhibits an implicit bias in taking certain preferences for granted.Footnote 55

Thus, a conceptual and empirical challenge for the SOL model when studying variation in the legitimacy of governance providers is the diversity of possible audiences across international politics. Indeed, relational theory, specifically its conviction of interrelatedness and procedural change, reminds us that both the material and discursive characteristics of any governing entity (such as legitimacy sources) have little meaning within themselves without scrutinising how these characteristics are situated within the relation, how their meaning is shaped by the social arrangement between governors and governed, and how they are perceived by the audience under study.Footnote 56 Indeed, recent studies have noted that audience expectations are conditioned by social structures such as liberalism or the organisational environment.Footnote 57 Such a view makes clear that we cannot pre-specify what matters for legitimation processes through a dichotomy of ‘sources of legitimacy’. An IO might seek legitimacy from audiences ranging from states to NGOs to civil society, and these actors’ normative benchmarks will invariably differ.Footnote 58 For peacekeeping in particular, scholars have pointed out how the UN seeks legitimacy from local populations, local elites, their own staff, and the international community, all of whom project different expectations onto the institution.Footnote 59

To make matters more complex, audiences may apply different ‘benchmarks’ to different legitimacy referents such as the host state or international institutions.Footnote 60 Given the diverse political perspectives, interests, and socialisation backgrounds possible in international politics, pre-specifying sources fails to appreciate local norms and the audience-dependency of legitimation. Hooghe et al. make this argument for the example of recent contestations of global governance institutions in the Global North. For critics from the left, the assumption that procedures and performance matter might hold: ‘left-wing’ audiences might disagree with the concrete manifestations of international organisations, their procedures, and performance, but not fundamentally with the organisation itself. ‘Right-wing’ audiences, on the other hand, tend to disagree with international organisations regardless of their more specific characteristics.Footnote 61 The latter case, however, cannot be properly depicted by a theoretical reliance on pre-specified sources of performance and procedures.

One example which illustrates the difficulty of anticipating legitimation sources arises when considering that the heuristic category of performance generally theorises material benefits not only as ‘independent ingredients’ of political legitimacyFootnote 62 but also as necessarily giving rise to legitimating beliefs. However, this need not necessarily apply, as Roy argues for the case of Afghanistan: service provision in the country has not necessarily been a primary expectation of the state among rural civilian communities, as, historically, regional and local authorities have guaranteed most service provision.Footnote 63 Or consider the example of democratic procedures, which are frequently seen as elemental for procedural legitimacy. But the meaning of procedural characteristics such as democracy can be heavily localised.Footnote 64 For instance, as Wallis shows for the case of East Timor, the term democracy itself was foreign in the late 1990s, and people’s expectations towards democratic procedures markedly differed from common definitions thereof.Footnote 65 In other words, by focusing on rulers’ sources rather than audiences’ expectations, the SOL literature often ignores what a given source means within a relation and whether normative value is attached to it.Footnote 66

Thus, taking the relationality of legitimation seriously means acknowledging that legitimation is audience-dependent, instead of pre-specifying sources for a governance relation. Certainly, it can be a valid methodological choice to bracket the process of meaning acquisition in some instances and take the relevance of certain sources as a given in a specific context. But if we want to expand our models of legitimation in a way that allows us to explain variation of support and legitimacy within complex governance networks, taking such localised, relationally grounded meaning seriously will be an important starting point. Ultimately, our models of legitimation seek to say something about audiences, but much of the theoretical persuasiveness is hampered by its analytical focus on governing actors and the pre-specification of sources.

Exogenous change of expectations

Second, the SOL model remains limited in that it treats change within actors’ expectations (not their evaluations) as exogenous to its models. With expectations, I mean the ‘normative benchmarks’ of audiences, the social values against which they compare the sources of legitimacy of a governing actor.Footnote 67 At its core, the SOL literature looks at the interaction of the legitimacy sources of a governing actor and its framing, on the one hand, and the audience’s priors on the other, without, however, theorising expectation change through these repeated interactions between actors.Footnote 68

Thinking about change in governing actors’ legitimacy, the SOL model has theorised (de)legitimation by investigating the (perceived) change within the governance actors’ sources of legitimacy.Footnote 69 For example, Tallberg and Zürn have centred on framing as a pathway to influence the perception of an institution’s sources of legitimacy.Footnote 70 Lenz and Viola, who criticise the omission of endogeneity in models of legitimation, have introduced a logic of cognition to theorise change in perceptions of legitimacy sources.Footnote 71 Both Dingwerth et al. and Bexell et al. theorise how larger social structures condition the expectations of audiences.Footnote 72 However, these advances do not explore further paths of how audiences’ expectations may change as a result of legitimation processes.

Thus, a challenge for the SOL model remains explaining how actors become legitimate in the complex governance networks of international politics over time, where various actors use legitimation strategies to sway their audiences. Indeed, relational theory, specifically its core pillar of mutual influence and procedural change, holds that actors’ beliefs and expectations should be seen as premised on interactions with other actors in the broader network. Such a view makes clear that we cannot consider audiences’ expectations as exogenous to legitimation processes. Rather, we have to think of an actor’s expectations (or priors) with regard to legitimate governance as continuously renegotiated through legitimation processes. Here, I diverge from scholarship theorising social structures to condition legitimation, which faces the problem that social structures tend to be stable and thus cannot fully account for change over time.Footnote 73 In other words, while the SOL model allows the observation of the change of legitimacy beliefs (an audience considers a governing actor more legitimate due to its procedures being framed as ‘democratic’), a more fundamental change in expectations (how an audience comes to value democratic over authoritarian norms) is exogenous to its theorising. Thus, audiences are reduced to reactive consumers who either approve or disapprove of the offers on the legitimacy market.Footnote 74 But doing so neglects how governance relations and legitimation processes therein shape the beliefs of actors about what legitimate governance entails.

Indeed, given that the discursive contestations of power-holders and rulers – their legitimation attempts – are purposed to stir thinking or emotions, such an assumption seems hard to sustain. In that case, we need to be able to account for how these interactions shape audiences’ ideas about rightful rule. For example, if we think about the continuous efforts of the EU to portray itself as a legitimate governance provider over decades, it seems key to be able to depict a change in constituents’ perceptions about moral standards of supranational governance when analysing EU legitimacy.Footnote 75

Moreover, in contexts of complex governance networks such as international politics, audiences might be embedded in various governance relations. For example, within Europe, governance relations might be manifold; a population might act as legitimation audience towards regional authorities, the federal state as well as the European Union. These actors contest for legitimacy, forcing audiences to continually interpret and evaluate framings and justifications and compare them against each other. Scholars have shown that audiences’ evaluations of governance providers are often translated from other governance levels through a kind of analogy.Footnote 76 Taking these network dynamics seriously then means that an analysis of, say, the legitimation of EU governance towards a national population must necessarily also take into account the legitimation of this population’s state. In other words, actors’ expectations and evaluations within governance relations should be seen as shaped not only within but also across governance relations within networks of governance.

Certainly, SOL models generally bracket out such dynamics rather than denying the endogenous change in audiences’ expectations. But the question remains whether we can afford such scope conditions if we want to explain legitimation processes in international politics over time. Instead, we need to scrutinise the mechanisms endogenous to legitimation which shape actors’ expectations about rightful rule – both within and across governance relations. Within a governance relation, Lenz and Söderbaum have recently argued for the importance of acknowledging that governing actors seek to change audiences’ priors about rightful rule but have not yet theorised how such change might come about.Footnote 77 Across governance relations, some existing work, such as Goddard’s work on institutional change, has started to provide first avenues to explaining how networks affect legitimation dynamics.Footnote 78 These studies have set important cornerstones, which this article will build upon to identify mechanisms through which complex governance networks within international politics shape legitimation processes.

A relational theory of legitimation of governance

In this section, I build on existing scholarship to propose a relational theory of legitimation – the process of how legitimacy comes about – that offers theoretical avenues to mitigate the identified challenges in the literature. I put forward a conceptualisation of legitimation that allows us to think about the unique dynamics of the contested, fluid, and poly-centric environment of international politics and the role of audiences therein. In other words, I argue that the SOL model can be fruitfully expanded by building on relational theory in IR.

Such a shift has important analytical payoffs. As the previous section has illustrated, there remains a noticeable gap in adequately theorising the various intricacies and contextual underpinnings of (de)legitimation processes within international politics. Specifically, existing theory remains frequently embedded in pre-specified legitimacy sources and exogenous models of expectation change. Doing so, it fails to address how we can explore legitimation across international politics without a ‘normative background theory’ about potential legitimacy sources and how legitimation processes influence actors’ expectations regarding rightful governance over time. Addressing these questions deepens our understanding of legitimation processes and starts to disentangle the interplay between institutions, audiences, and the broader governance network.

I advance my conceptualisation by building on the aforementioned key relational tenets of interrelatedness, mutual influence and procedural change. As opposed to pre-specifying sources of legitimacy, I focus on audience expectations to anchor the study of legitimation and outline mechanisms of change of expectations as endogenous to legitimation. Doing so, I proceed in four steps. First, I set the theory’s scope and its actors. Second, I introduce the heuristic structure of legitimation patterns to the study of legitimation. Third, I conceptualise the process of legitimation as congruence-finding across governance networks and give an overview of various mechanisms that might impact the (de)legitimation of governance relations. Finally, I discuss the implications of this theory.

The scope of legitimate governance

In international politics, a plethora of governing actors coexist: most importantly states and their governments; populations; international organisations, NGOs, and firms; but also armed actors such as insurgents. All these actors provide governance to audiences – from states to NGOs to citizens – and are in various ways involved in processes of legitimation. In line with extant scholarship, I understand legitimation as a function of a governance relation between rulers and ruled, defined as ‘institutionalized modes of social coordination to produce and implement collectively binding rules or to provide collective goods’.Footnote 79

Within a given relation, it is useful to differentiate between governance providers and governance takers, or rulers and ruled. After all, it is exactly from these different positions within a governance relationship that the need for legitimation arises. But given the diversity of governance relations in international politics, this theory remains agnostic to who is or is not an actor of legitimation a priori. For example, the German state can be considered as a governing legitimation seeker in this relation to its population but acts as a legitimation audience with regards to supranational institutions such as the European Union. The German population can be considered a legitimation audience with respect to its state; towards an intergovernmental institution its state is a member of, such as the WTO, it might not be. Finally, the EU is not only constituted as a governance provider towards both the German state and its population, but also as an audience towards other IOs it is subordinated to, such as the WTO. As such, actors’ roles within legitimation processes can be conceived as fundamentally dependent on their participation and position in social relationships of governance.

Expectations and legitimation patterns

I defined legitimacy as a perception that a given governance relation is rightful. But what gives rise to such perceptions? I suggest putting actors’ normative expectations about governance at the heart of a theory of legitimation. Doing so, I provide an alternative starting point to pre-specifying sources of legitimacy, addressing my first point of critique above.

I start from the premise that all actors in international politics, regardless of whether they are in a position of power or subordination, have certain normative expectations of how they envision rightful governance relations. These expectations form what Gippert calls audiences’ ‘normative benchmarks’, a threshold of what rightful rule entails for a given actor,Footnote 80 and can also be related to what Stappert and Gregoratti call ‘justifications’, the normative underpinnings of legitimation claims.Footnote 81 In that sense, they can be understood to form a kind of ‘background knowledge’ which helps actors to make sense of governance.Footnote 82 Such beliefs stem from historical experience and previous socialisation and, more importantly, are shaped by the broader network of governance relations (both spatial and temporal) and the actors within them. These beliefs might differ according to the kind of governance relation in question, or they might not be fully developed but rely on analogies or heuristic shortcuts,Footnote 83 a point I return to below. I conceptualise these normative expectations of what a legitimate governance relationship should look like as legitimation patterns.Footnote 84

How can we structure the analysis of such legitimation patterns? Rather than relying on the performance–procedure dichotomy for the problems detailed above, I draw on political theorist David Beetham to develop a heuristic to analyse which kinds of norms bear relevance for the legitimation patterns of governance relations in international politics. One of the most influential theorists of legitimation, Beetham has proposed a fourfold model of legitimacy, stemming from the interplay of expectations about legality, sources of authority, the common good, and modes of consent.Footnote 85 First, legality describes the requirement that any power must be acquired and exercised according to pre-existing rules that define and contain the power relation.Footnote 86 Second, sources of authority capture beliefs about the origin of these rules and why they are seen to enjoy qualities justifying subordination to them. Third, common good pertains to beliefs about what the ‘proper ends and standards of government’ are and how they benefit the governance takers.Footnote 87 Fourth, modes of consent describe the need for a ‘demonstrable expression of consent on the part of the subordinate’.Footnote 88 Whenever actors engage in public actions that demonstrate compliance with a power relationship, they legitimise it. Whose and what mode of consent matters within a given context, Beetham adds, is culturally defined.

I argue that this fourfold structure serves as a valuable heuristic to analyse actors’ legitimation patterns and their normative expectations of what a legitimate governance relationship should look like, namely as the rules, sources of authority, common goods, and modes of consent that an actor believes to constitute legitimate governance in a given context. Let me be clear in saying that I do not hold that legitimation patterns are necessarily structured that way, but that such a heuristic framework helps us to make sense of the relationally grounded expectations actors hold towards governance.

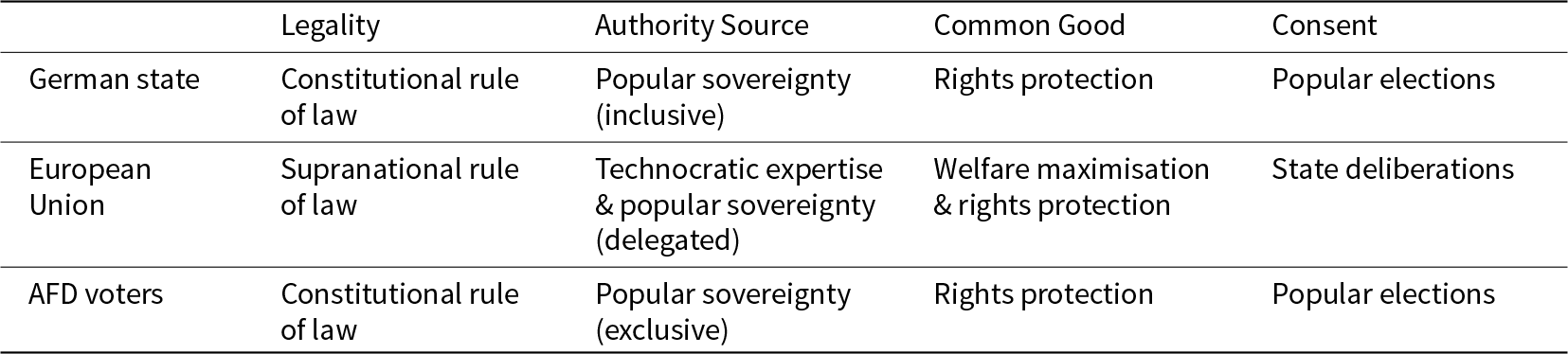

To illustrate the empirical implications of this fourfold heuristic structure to analyse normative expectations about legitimate governance, let us briefly return to the example of Germany and the EU in the most general terms and sketch a snapshot of a governance network between the EU, the German state, and a part of the German population supporting and voting for the right-wing party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). In this network of governance relations, the EU arguably acts as governance provider towards both the German state and the German population. The German state is of course involved in the governance of the EU itself through both its intergovernmental and representative forums. But in terms of its social coordination, most notably EU law, the German state acts as governance taker towards the EU. Furthermore, it acts as governance provider towards its population. Finally, the AfD supporters act as governance takers. To identify actors’ expectations towards governance within this network, we can draw on David Beetham and Christopher Lord’s analysis of the legitimacy of the EU.Footnote 89

The German state, very much embedded in the notion of the liberal state, could – according to the authors – be analysed as such: in terms of rules, Germany pursues a constitutional rule of law; in terms of justifications, Germany grounds its authority in popular sovereignty and the protection of individual rights; in terms of modes of consent, the German state builds on popular elections.Footnote 90 In contrast, while the EU can be said to ground their rules on supranational rule of law, its justifications differ: it builds its authority on technocratic expertise next to popular sovereignty, and the common good of its governance is portrayed to be welfare maximisation as much as rights protection. As a mode of consent, the EU builds chiefly on deliberation among states.Footnote 91 Finally, let us contrast those two governance providers with supporters of the right-wing party AfD. Arguably, this part of the German population holds normative expectations towards governance that more or less mirror those of the institutionalised German state – with one significant difference. The former arguably has a markedly different conception of who ‘the people’ relevant for justification of popular sovereignty and for consent via popular elections are, a more exclusive notion than generally provided by the state.Footnote 92 I illustrate this conceptualisation in Table 1.

Table 1. The heuristic structure of legitimation patterns.a

a Data based on Miguel Ayerbe Linares, ‘The Volk (“people”) and its modes of representation by Alternative für Deutschland-AfD (“Alternative for Germany”)’, in Jan Zienkowski and Ruth Breeze (eds), Imagining the Peoples of Europe: Populist Discourses across the Political Spectrum (Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2019), pp. 285–314, and David Beetham and Christopher Lord, Legitimacy and the EU (London: Longman, 1998).

Notably, this empirical snapshot is meant as a simplified illustration of the heuristic structure of legitimation patterns. Nevertheless, the example shows that adopting this heuristic device to study legitimation has a crucial advantage: While the fourfold structure of legitimation patterns identifies heuristic categories, it focuses on actors’ expectations rather than institutional sources and remains theoretically open to the relationally grounded manifestations of expectations about governance. As Table 1 illustrates, what legitimate governance means for actors embedded in governance relations might differ both structurally (between the EU and Germany) or substantively (between the German state and the AfD movement). This approach allows us to capture the audience dependency of legitimation and the historically and culturally bound expectations of governance takers and governance providers around the globe, instead of reproducing pre-specified taxonomies of legitimacy sources. Moreover, it avoids considering material benefits (or performance) as inherently giving rise to legitimacy by conceptualising both material and symbolic elements of governance in terms of expectations, which helps to resolve the contradiction that is often found in scholarship of ‘performance legitimacy’ or ‘output legitimacy’.Footnote 93

Legitimation as congruence-finding

How do actors’ legitimation patterns interact when rulers and ruled engage in a governance relation? As detailed above, the SOL approach utilises the idea of a ‘fit’ between attributes offered by the legitimised entity and the norms held by its environment.Footnote 94 However, while the conceptualisation of legitimacy as ‘congruence’ tells us about the ‘when’ of legitimacy, it fails to account for the ‘how’.

As a second step of my theory-building, I argue that legitimation should be understood as a process of congruence-finding: as governance providers and governance takers engage in a governance relation, both actors evaluate this relation, more specifically, its discursive and material manifestations, to see whether their normative expectations meet. At the same time, through their interactions, these actors may also change and adapt to each other’s normative expectations. The degree of congruence between the legitimation patterns of a governance provider and a governance taker will shape governance actions within the relation, with more congruence giving rise to more support. The notion of congruence-finding emphasises that ‘legitimacy cannot be a stable condition but is something fluid that must be repeatedly created, recreated, and conquered’.Footnote 95 Doing so, it addresses the second point of critique that the current literature on legitimation treats change in actors’ expectations about rightful rule as exogenous.

Analytically speaking, a legitimation process can thus be conceptualised as a search for congruence between a governance provider and a governance taker – the process of establishing, finding, and negotiating congruence for each of the four elements of legitimation patterns identified above: normative expectations about rules, sources of authority, common goods, and modes of consent that for an actor make up rightful governance. Such processes might occur explicitly (the discursive justification of rule by a ruler, public protest by the ruled) or implicitly (engagement with everyday practices of governance). Notably, empirical legitimation processes do not necessarily play out consensually in a well-intentioned public sphere, and congruence-finding should not be understood as a one-way street towards legitimate governance. Rather, interactions of congruence-finding might end in the shared recognition of actors that legitimation patterns show little overlap, resulting in the delegitimation of a governance relation.

Returning to our example of Germany and the EU presented in Table 1, we see now how AfD voters, the German state, and the EU – through the various material and discursive interactions that make up their governance relations – might compare and contrast each other’s normative expectations. Given that the legitimation patterns of both the German State and AfD voters show overlap in terms of rules, the relation cannot be considered illegitimate – however, it may show a legitimation deficit due to the substantively different conception of ‘the people’. At the same time, the German state might have a greater degree of congruence with AfD voters than the European Union: on its own, a justification of authority through popular sovereignty may show more congruence than when this justification stands next to technocratic expertise. These degrees of congruence will in turn affect levels of support within each of the governance relations.

To draw on an example in a very different context of governance, consider the United States–Taliban conflict in rural Afghanistan: while the United States sought to justify their governance through notions of popular sovereignty, the Taliban emphasised religious obedience to Islam. Arguably, the Taliban’s strict interpretation of Islam was as much an import to rural Afghanistan as was the liberal notion of popular sovereignty.Footnote 96 However, the latter’s success not only stemmed from their attempts early on to respond to local needs, but communities throughout the country were also able to negotiate with the Taliban on various governance policies.Footnote 97 Within the conservative and religious rural population, the United States’ justifications deviated significantly more from local expectations than the Taliban’s (partially) adaptive governance relations, fostering local forms of support.

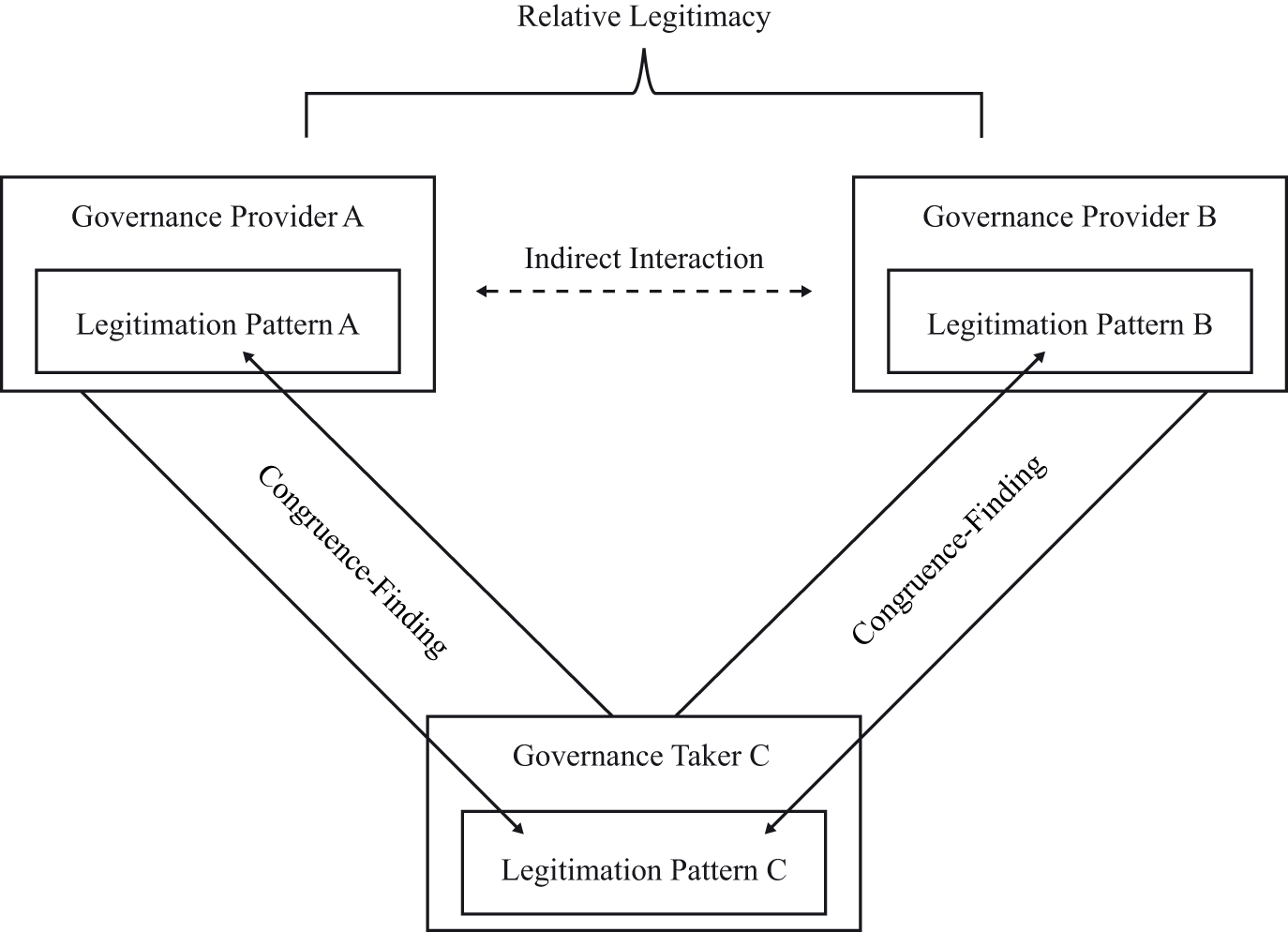

How might actors’ expectations change endogenous to such a process of congruence-finding? I conceptualise various mechanisms influencing a relation’s legitimacy, drawing on McAdam et al.’s differentiation between cognitive and relational mechanisms. They define mechanisms as ‘a delimited class of events that alter relations among specified sets of elements in identical or closely similar ways over a variety of situations.’Footnote 98 While the literature on mechanisms has made notable advances in more recent years,Footnote 99 McAdam et al.’s insights remain useful to my theory of legitimation as they see mechanisms specifically as events set within and changing a social network. After all, the interrelatedness of governance in international politics means that any governance relation will be entangled with other governance relations, and that these in turn shape the relation and the actors within it. These network effects may occur consecutively as one governance provider supersedes another as ruler of a given governance taker. More commonly in contemporary international politics, they occur simultaneously as several governance providers are engaged in partial governance over one governance taker.

Cognitive mechanisms describe forces that impact legitimation processes from within a given relation. Both governance providers and governance takers might shape the congruence of a governance relationship through their interactions in ways that concur with their own legitimation patterns. Here, constructivist literature on mechanisms of socialisation is especially insightful, as it has advanced our insights into cognitive mechanisms leading to the acceptance or alteration of social norms by agents.Footnote 100 For example, scholars of socialisation theory have proposed the cognitive mechanism of persuasion. Social interaction is conceptualised as a communicative process of exchanging arguments and information where providers and takers seek to convince each other of their viewpoint while at the same time being open to being persuaded themselves.Footnote 101 As such, governance providers and takers can be both perpetrators and targets of socialisation attempts. An actor may decide that the persuader’s belief bears more merit than its own and consequently alter its beliefs accordingly. Attempts at persuasion can be manifold: thinking back to our example of the EU and Germany, McNamara details how the EU as a governance provider, through employing symbols and practices, seeks to naturalise and legitimise itself, eventually resulting in the persuasion of governance takers, or in her words ‘taking-for-grantedness’, of EU authority.Footnote 102

Through another mechanism of social learning, a governance provider might itself change its legitimation pattern:Footnote 103 consider the United States/NATO campaign in Afghanistan, in which the United States initially based its governance on heavily Western-centric norms, only to gradually learn about local norms and adapt its governance approach to some extent.Footnote 104 Notably, socialisation theory has been criticised for neglecting the socialisee’s agency;Footnote 105 however, more recent studies have conceptualised socialisation as a two-way street.Footnote 106 Hence, this literature provides a fruitful avenue to theorise both governance providers and governance takers as agents within the processes of legitimation.Footnote 107

Relational mechanisms describe forces which impact legitimation processes across governance relations, ‘alter[ing] connections among people, groups, and interpersonal networks’.Footnote 108 These are mechanisms where the relation between one governance provider and taker is changed by altering how these actors are positioned in the network and are embedded in other governance relations.

One possible relational mechanism is actor change. On the level of a state’s population, we might think of migration or displacement, which might lead to changes in an actor’s legitimation pattern through new influences and cultural adaptations.Footnote 109 Equally, governance providers might experience such actor change. Consider the case of the EU, where the institution as a governance provider towards the German population might be significantly changed through the external dynamic of the member states signing a new treaty, such as the strengthening of the European Parliament.

Congruence-finding might also be influenced through the relational mechanism of script diffusion.Footnote 110 New beliefs might very well emerge outside a given governance relation but consequently diffuse across a governance network. Doing so, they might impact actors’ expectations by opening up possibilities of alternative governance structures, thus influencing congruence-finding between providers and takers. Actors become confronted with new governance discourses and practices, impacting their normative expectations towards not only the new but also the existing governance relations. For example, Kurzman argues that in the case of the Iranian revolution, what sparked the Shah’s fall was not so much the regime’s own performance but rather a perception among the population that viable alternatives in the form of Khomeini and his followers existed, which promised a bettering of circumstances.Footnote 111 Or consider the EU’s Eastern enlargement: on the one hand, this expansion increased the space for post-Soviet populations to compare between governance providers and opened up the possibility of viable alternatives. Thus, a population’s engagement in a new governance relation to the EU might significantly alter its relative congruence with its state because alternative ways of congruence become tangible. On the other hand, governance expansion might lead the provider to adapt to new governance relations, altering its engagement or position within already established ones. As Seidelmeier argues, the Eastern enlargement produced a new wave of codifications of liberal values such as democracy and human rights, impacting both established and new members alike.Footnote 112

In sum, these non-exhaustive and potentially coexisting mechanisms can help us to explain how governance relations change towards greater or lesser congruence, and thus become legitimised or delegitimised over time. A graph of the complete theoretical framework is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The process of legitimation.

The implications of congruence-finding

Conceptualising legitimation as a process of congruence-finding shaped by mechanisms embedded in governance networks has three theoretical implications. First, it allows us to take the relationality of legitimation seriously: instead of conceiving legitimacy as belonging to an actor, the approach focuses on legitimation as emerging from a relation between a governance provider and governance taker. Expectations and actors’ legitimation patterns have to be thought of as shaped not only by interactions within a governance relation but also the network more broadly. In the latter case, all providers engaged in a governance relation with a given governance taker will seek to influence the taker’s legitimation pattern. Thus, an indirect interaction effect between the governance providers emerges: as the taker’s legitimation pattern changes towards more congruence with one provider, (in)congruence with other providers might shift as well. Hence, a governing actor cannot be legitimate per se; rather, it is through the interactions in a governance relation that congruence or divergence is found and a relation between a governing actor and an audience becomes seen as legitimate in a given moment in time, which in turn might influence the stability and levels of support of this relation.

Second, congruence-finding highlights that legitimation is relative to other governance relations. On the one hand, we might observe zero-sum games of legitimation between different governance relations, where the more congruence the legitimation patterns of a governance provider and a governance taker show relative to other governance providers, the more legitimate their relation is. The availability of and comparison with alternatives is thus crucial for any assessment of congruence and legitimation.Footnote 113 On the other hand, we might also see positive-sum games of legitimation, as one governance relation shapes an actor in a way where they will see greater congruence with another governance relation as well, for example through what Dellmuth and Tallberg call a domestic analogy.Footnote 114

Third, congruence-finding implies that legitimation is multidimensional and can only ever be assessed in degrees. Most governance relations experience deviations from established rules and there are always those who do not accept a given justification or way of consenting to a governance relation. The heuristic structure of legitimation patterns and the four elements of rules, source of authority, common goods and modes of consent help us to capture these different degrees of legitimation. A given governance relation can show more or less congruence within each of the four elements of the legitimation patterns. For example, one governance relation might show more congruence with regard to its source of authority, while another one involving the same audience might show more congruence with regard to rules. These degrees can be analytically subsumed into a general degree of legitimation, although congruence regarding rules, sources of authority, common goods, and modes of consent will matter here to a descending extent. Rules are the fundamental structure on which any governance relation is built; as such, deviations from beliefs towards rules will have the most considerable bearing on congruence. Justifications about sources of authority or the common good serve to defend these rules, and deviations thereof will lead to a legitimation deficit, undermining congruence to a substantial but lesser degree. Finally, modes of consent delineate ways of confirming the rules and justifications. Deviations regarding modes of consent have the most minor bearing on congruence, as they only describe how to participate in a governance relation and not the substance of the governance itself.

This multidimensionality allows us to compare a governance relation over time or to other governance relations with regard to each dimension of the legitimation patterns and as a whole. Moreover, it provides an avenue to account for the stability of legitimate governance over time. While rules generally tend to be sticky, especially when enshrined in treaties or constitutions, justifications and modes of consent are less so. This, in turn, means that governance might exhibit a legitimacy deficit despite congruence in rules. At the same time, however, the same rules may be justified through new sources of authority or common goods, allowing governance relations to remain stable despite actors’ normative expectations continually changing.Footnote 115

Conclusion

In this article, I have sought to expand on the literature on legitimacy and legitimation in international politics by developing tools to theorise the diversity of expectations, norms, and understandings of rightful governance present within international politics across space and over time. I argued for the need to build on key insights from relational theory by considering actors and international politics more broadly as embedded in dynamic networks of governance. Taking seriously this relationality of legitimation, I noted, allows us to go beyond the blind spots of the existing literature, most importantly a reliance on pre-specified sources of legitimacy and a consideration of change in actors’ expectations as exogenous to legitimation. I have put normative expectations about governance centre stage, theorising legitimation as a process of congruence-finding between the normative expectations, the legitimation patterns, of governance providers and governance takers. As governance in international politics is multilayered, legitimation processes are always dependent on the relation’s positioning within the broader network of governance relations and its actors. Consequently, I argued that congruence-finding may be shaped through a set of cognitive and relational mechanisms. The degree of congruence between the legitimation patterns of a governance provider and a governance taker will shape governance actions within the relation, with more congruence giving rise to stabler governance practices.

What can we see with this theory that we did not see before? In this concluding section, I would like to argue that my model advances the study of legitimation both theoretically as well as methodologically. First, the theory provides a model of legitimation that does not require a normative background theory of certain sources of legitimacy but argues for a contextual focus on actors’ normative expectations. By theorising legitimation as embedded in governance networks, it allows us to appreciate the multiple layers of international politics and the various kinds of actors involved. For example, a state might be both governance taker and governance provider at the same time within different governance relations. In that way, such a model also enables us to reconsider the various ways in which domestic governance might influence international legitimation processes and vice versa.

Second, the model allows us to better account for change in the study of legitimation by considering the endogenous dynamics of legitimation rather than focusing on independent characteristics and their interplay. Conceptualising expectations about legitimate governance as patterns that – via a set of mechanisms – diffuse and shift across networks provides a theoretical hook to investigate why audiences interpret different or new governance relations similarly and how processes of legitimation are caught up in networks of governance. As such, these considerations help us to address what scholars have called a ‘knowledge gap’ of citizens, as their awareness and knowledge about IOs varies along socio-economic status and cosmopolitan identities.Footnote 116 It is thus unrealistic to assume that any given audience has well-developed expectations towards a given governance relation. Rather, an audience’s expectations, its legitimation pattern, are shaped through the various governance relations it is embedded in: with a state, Ios, and regional governments. In that way, legitimation patterns act as ‘scripts that diffuse through networks and otherwise embed in the ongoing transactions that constitute social and political life’.Footnote 117

Third, the theory recasts the question of how governing actors in international politics become legitimised from one asking for sufficient and necessary conditions to one investigating legitimation as an ongoing process that continuously shapes and is shaped by actors engaged in governance relations. I have sought to put forward the building blocks of such an analysis by introducing the notion of congruence-finding to this debate. Methodologically, this means in consequence putting actors’ expectations towards rightful governance centre stage and investigating how these expectations are shaped through governance relations. Such a move necessitates an interplay of methods that are able to map actors’ expectations inductively, such as discourse analysis looking at actors’ statements or open-ended surveys or interviews inquiring into actors’ ideas and beliefs, in conjunction with methods such as social network analysis or process tracing, which allow us to track the mechanisms through which actors’ expectations change through interactions within and across governance relations.

Certainly, this is only an initial attempt at synthesising relational theory with the literature on legitimation in international politics, and there are limitations to the proposed conceptualisation of legitimation. First, the article largely leaves aside the consequences of congruence-finding, which remain to be comprehensively theorised and studied. However, we can now already draw on existing scholarship which highlights compliance, stability, and effectiveness as possible outcomes of the successful legitimation of a governance relation.Footnote 118 Second, the theory has thus far not received thorough empirical testing. While I have given empirical examples from various types of governance relations throughout the text to illustrate its usefulness, further scholarship is needed to substantiate the theory’s empirical applicability. One particularly insightful avenue would be to explore the empirical manifestations of legitimation within various governance settings – from global governance to regional or sub-regional governance relations – and assess its effects on the control, support, and efficiency of said relations. Third, this conceptualisation of legitimation in international politics adds more complexity to an already-complex concept, especially compared to the literature on ‘sources of legitimacy’. But the relational perspective on legitimation gives us a more comprehensive picture of contemporary governance relations within international politics by doing away with a normative background theory and embracing the diversity of expectations and their change over time within networks of governance. As such, the theory advanced here contributes to our understanding of legitimation of governance in international politics by allowing for a richer, more in-depth analysis of its underlying processes.

Video Abstract

To view the online video abstract, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210524000111.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jeffrey Checkel, Stephanie Hofmann, Shubha Kamala Prasad, Benjamin Mueser, Stefano Guzzini, Isabelle Duyvesteyn, the participants of the International Relations Theory Working Group at the European University Institute, and three anonymous reviewers for their invaluable support in advancing this article.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the OeAD and the Austrian Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Research.

Competing interests

The author declares none.