Introduction

In a briefing to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), UN Secretary-General António Guterres called mediation one of ‘the most important tools to reduce human suffering’.Footnote 1 Mediation is commonly defined as a process ‘where those in conflict seek the assistance of, or accept an offer of help from, an outsider … without resorting to physical force or invoking the authority of law’.Footnote 2 Mediation has become a standard international response to armed conflicts since the end of the Cold War, with the UN playing a leading role in many peace processes.Footnote 3 Yet, recent failures to bring the conflicts in Libya, Syria, and Yemen to a negotiated agreement have led to a questioning of the UN's role to promote a pacific settlement of contemporary armed conflicts.Footnote 4

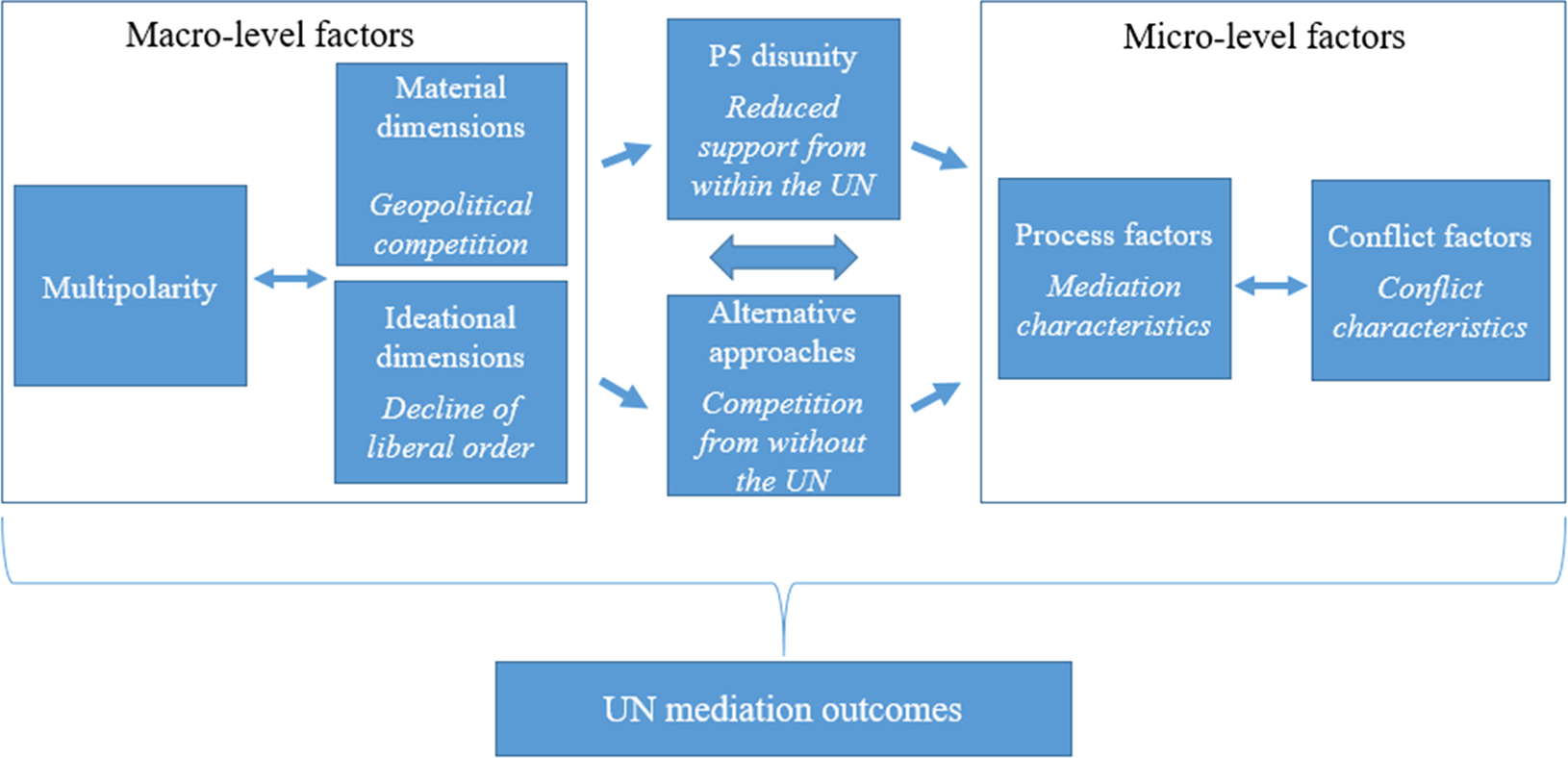

The existing literature predominantly explains such mediation outcomes by focusing on micro-level aspects, examining either process factors Footnote 5 in terms of the characteristics of the mediation or conflict factors Footnote 6 in terms of the characteristics of the conflict context. Both play a crucial role in understanding mediation. However, as I show in this article, these micro-level factors need to be understood in light of macro-level factors related to the world political environment in which mediation processes take place. While it is a truism that world politics affect peacemaking, the exact way in which changing world orders influence mediation outcomes has received relatively little scholarly attention.Footnote 7 Yet, such an analysis is particularly important in light of the current tectonic shifts in the prevailing world order from unipolarity to multipolarity, with the United States (US) no longer being the sole superpower, and other actors, such as China and Russia, playing increasingly important roles in world politics.Footnote 8 It is thus crucial to explore how these macro-level factors influence mediation. Without such an analysis, we risk neglecting the structural environment in which mediation takes place and may therefore have an incomplete view or even misinterpret what determines mediation outcomes.

In this article, I fill this gap by examining the mechanisms through which macro- and micro-level factors interact and how they jointly influence mediation outcomes.Footnote 9 To do so, I focus on UN mediation in internationalised civil wars. I analyse the UN due to its central role in mediation. Its main mandate is the maintenance of peace and security with a priority accorded to the pacific settlement of disputes and it constitutes an arena where major discussions around mediation take place. I specifically look at UN mediation in internationalised civil wars, defined as armed conflicts in which at least one of the parties receives military support or training, weapons, or other logistical and financial backing from other governments.Footnote 10 Internationalised civil wars are not a new phenomenon, as evidenced by the proxy wars during the Cold War. They have, however, seen an unprecedented increase in recent years, skyrocketing from 9 in 2012 to 25Footnote 11 in 2020.Footnote 12 Internationalised armed conflicts, like the ones in the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Libya, Syria, or Yemen, are likely to be more lethal and last longer than other civil wars because external actors provide resources to sustain the fighting and more actors have stakes in their outcomes.Footnote 13 They therefore represent extreme cases for UN mediation considering their limited prospects for success. Yet, it is often in such cases that the UN's legitimacy in peacemaking is evaluated. It is thus of particular relevance to better understand UN efforts to resolve them.

The article takes UN mediation in Syria from 2012 to 2018 as a case study. The war in Syria constitutes a typical case of internationalised civil wars and the challenges of resolving them. In the period under study, the conflict opposed the government and opposition groups,Footnote 14 with the main bone of contention being the fate of President Bashar al-Assad's regime. The Gulf States, Turkey, European states, and the US provided military training and provisions to the opposition while Iran, Hezbollah, and Russia backed the Syrian government with military supplies and support. The assistance that the parties received was not equal, however. Russia was determinant to keep Assad in power and intervened militarily in September 2015.Footnote 15 The US, in turn, made it increasingly clear that it would not get too deeply embroiled in the Syrian conflict, as a military intervention on behalf of the opposition would clash with its strategic and material interests.Footnote 16 The conflict also metastasized into various subconflicts due to a fragmentation of opposition groups and the formation of new armed, and often radical, actors, thereby blurring the distinction between a distinct pro-government and pro-opposition alliance. Most importantly, the rise of the Islamic State (IS) in Syria substantively changed the conflict dynamics and alliances. This complexity made the Syrian conflict particularly challenging to address. Between 2012 and 2018, the UN mandated three Special Envoys to Syria,Footnote 17 indicating the difficulty of peacefully resolving the conflict. This led some authors to refer to the situation in Syria as ‘mission impossible’Footnote 18 or pointing to it as an instance of ‘entrapment’.Footnote 19

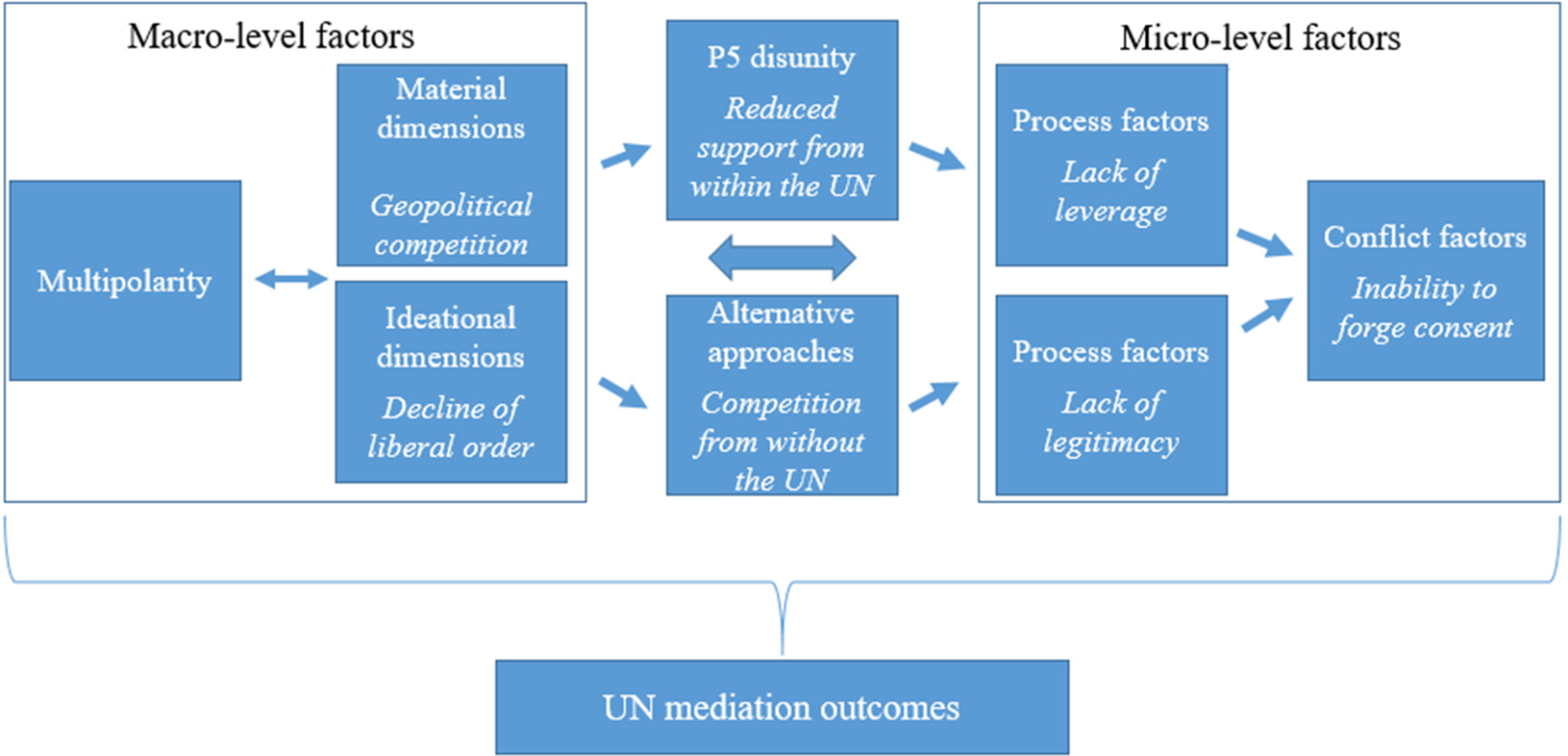

In this article, I analyse how macro-level factors related to world politics interacted with micro-level factors related to the mediation process and conflict context in producing this impossibility of bringing the Syrian armed conflict to a negotiated agreement. I argue that at the macro level, multipolarity has both material and ideational dimensions that manifest themselves in a resurgence of geopolitical competition and a decline of the liberal normative order.Footnote 20 These macro-level factors have affected UN mediation in two main ways. First, they have led to increased disunity among the permanent five members (P5) of the UNSC, resulting in reduced support to mediation from within the UN. Second, alternatives to the liberal peacemaking approachFootnote 21 have emerged, leading to competition to UN mediation from without the UN. In the case of Syria, this lack of internal support paired with outside competition influenced micro-level factors as the UN mediators were unable to garner the necessary leverage and legitimacy to forge the parties’ consent to find a negotiated solution.

The article draws on two main sources of data. First, 41 in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted between June 2018 and July 2020 with the former UN Special Envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura, UN staff and diplomats involved in or close to the mediation process, Syrian civil society and political actors, and experts on Syria, including from both the US and Russia.Footnote 22 Second, I reviewed press statements and UNSC briefings by the three UN Special Envoys appointed as mediators during the period covered.

The article unfolds in two parts. It first provides a conceptual framework to analyse the impact of world politics on UN mediation by examining how macro- and micro-level factors interact. It then analyses UN mediation in Syria. It shows that changing material and ideational factors have led to a weakening of the UN as a peacemaker, rendering its mediators unable to broker a peace agreement. Thereby, the article makes two main contributions. First, it provides a systematic analysis of the link between world politics and UN mediation by complementing micro-level explanations with a macro-level perspective. Second, it enables a better understanding of UN mediation in internationalised civil wars, and particularly in Syria.Footnote 23 Overall, the article contributes to reflections on how the UN can keep its relevance in peacemaking in a changing world order.

Conceptual framework

The micro level: Need for a complement

Existing research on mediation mainly focuses on the micro level, analysing either process or conflict factors.Footnote 24 Scholars interested in process factors study the characteristics of the mediation. A major subject in this regard are mediators’ styles, which are often clustered into different taxonomies that distinguish between more and less intrusive approaches.Footnote 25 The theme of mediators’ traits has also attracted attention, especially with regard to whether mediators are impartial or biased,Footnote 26 and what sort of leverage they have.Footnote 27

A second set of scholarship examines conflict factors studying how the characteristics of a conflict influence the prospects for mediation. Several authors argue that the conflict costs increase the parties’ willingness to engage in mediation.Footnote 28 One of the most well known concepts in this regard is ripeness as developed by I. William Zartman.Footnote 29 He states that in order for a conflict to be ‘ripe’ for mediation, there needs to be a mutually hurting stalemate on the battlefield and parties need to consider mediation as a viable alternative to fighting.Footnote 30 Other scholars have built on Zartman's ripeness theory and added quantitative and qualitative evidence to it.Footnote 31

These process and conflict factors are usually linked to mediation outcomes in terms of how they influence the prospect for mediation onset, for the signing of a peace agreement, or for the quality and durability of the ensuing peace.Footnote 32 While studying these micro-level factors is important, they are influenced by macro-level dynamics related to world politics. Indeed, some scholars have already considered mediation in the context of shifting global contexts.Footnote 33 Particularly noteworthy is the seminal book series edited by Chester A. Crocker, Fen Osler Hampson, and Pamela Aall, which analyses peacemaking in different periods.Footnote 34 However, while they provide crucial empirical details, the concrete mechanisms through which macro-level factors influence micro-level factors, and how the interplay between them shapes mediation outcomes, warrants deeper exploration. This article provides such an analysis as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework on macro- and micro-level factors influencing UN mediation outcomes.

The macro level: From unipolarity to multipolarity

Macro-level factors are influenced by prevailing world orders, which are commonly distinguished according to their polarity in terms of the distribution of power within the international system, with either unipolarity (one dominant power), bipolarity (two dominant powers), or multipolarity (more than two dominant powers).Footnote 35 The use of the concept of polarity as an indication of the prevailing world order in this article warrants two clarifications. First, while some authors define polarity based on a conceptualisation of power as material capabilities,Footnote 36 I ascribe to a definition that includes ideational aspects related to a state's influence on the ‘content’ of the international system. This refers to a state's capacity to shape the dominant norms and ideas in world politics.Footnote 37 Second, the three variations of polarity are ideal-types and their identification contains subjective elements.Footnote 38 Accordingly, some periods are subject to more contestation regarding the identification of the prevailing world order than others. Most authors agree on a bipolar world order during the Cold WarFootnote 39 and a unipolar order at the end of the Cold War.Footnote 40 Yet, while some authors describe the current world order as having arrived at multipolarity,Footnote 41 others see the shift as still ongoing.Footnote 42

I concur with the view that the world has become multipolar, defining it in line with Cedric de Coning and Mateja Peter as a situation in which each state has access to networks and forms of power sufficient to prevent any of the others from dominating the global order.Footnote 43 While the US remains militarily the strongest state,Footnote 44 other powers challenge both its material and ideational domination in world politics.Footnote 45 China has experienced rapid economic growth and challenges US global leadership through its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, its assertive posture regarding territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and its increased role in multilateral forums, such as those on climate change mitigation.Footnote 46 Moreover, Russia has equally reasserted itself as an influential power, as most recently manifested in its invasion of Ukraine.Footnote 47 Other states, such as Brazil, India, and South Africa, are also asserting a growing influence in international politics.Footnote 48 In this sense, US dominance in world politics is being questioned as other states exert power in the international system and ‘offer new ordering projects’.Footnote 49 As Roland Paris observes, ‘power seems to be diffusing away from the US and the Western “core” of the international system'.Footnote 50

I argue that this shift towards multipolarity has both material and ideational dimensions that manifest themselves in increased geopolitical competition and a declining liberal order. I will now explore these two dimensions in more detail.

Material dimensions of multipolarity: Geopolitical competition

Shifts in polarity have material dimensions. Authors argue that unipolarity creates relatively few incentives for interstate competition since the existence of a superpower leads to an undisputed hierarchy of power.Footnote 51 In turn, a shift towards multipolarity increases geopolitical competition, defined as ‘the contention between great powers and aspiring great powers for control over territory, resources, and important geographical positions’.Footnote 52 Geopolitical competition influences UN mediation insofar as it creates disunity among the P5 of the UNSC with the risk that they block important decisions through the exercise of their veto right. While the UN Secretary-General appoints the Special Envoys who act as mediators, the UNSC can call for such an appointment in the first placeFootnote 53 and is usually responsible for clarifying the mediator's mandate in a resolution. The UNSC can also provide mediators with leverage. Especially in conflicts where the conflict parties do not lend their sustained consent to mediation, the UNSC can create positive incentives or exert pressure by threatening the parties with sanctions, no-fly zones, embargos, or military intervention. This shows that the UNSC's unambiguous backing of mediators with a coherent strategy is vital for effective UN mediation.Footnote 54 In case of P5 disunity, UN mediators can thus be severely limited in their effectiveness.

What does this mean for the current shift from unipolarity to multipolarity? As discussed above, the end of the Cold War heralded a unipolar world order. While geopolitical competition was not fully absent,Footnote 55 it was less pronounced given US domination. This led to an unblocking of the UNSC and widespread support for the UN to offer its conflict resolution services.Footnote 56 The UN's role in peacefully terminating civil wars reached a high point in the early post-Cold War years, as it was involved in more than half of all mediated armed conflicts from 1992 to 2009.Footnote 57 While a number of conflicts remained unresolved, the UN registered some success in mediation in terms of peace agreements being signed under its auspices, including in internationalised civil wars, such as in Angola (1991) or the Democratic Republic of Congo (2002/03).Footnote 58

The multipolar world order, in turn, is characterised by ‘the “rebirth” or “return” of geopolitics’.Footnote 59 One major factor for this trend has been the rise of China and Russia and their competition with the US. While China has portrayed itself as ‘champion of liberal globalization’, it has engaged with the US in a trade war and in fierce competition over technological leadership.Footnote 60 Russia has also competed directly with the US since the mid-2010s, illustrated by its role in the Syrian conflict, its annexation of Crimea in 2014, and its invasion of the entire Ukraine in 2022.Footnote 61 This increased geopolitical competition has engendered disunity among the UNSC P5 and blocked it on key decisions. The number of UNSC resolutions vetoed has steadily increased since the 1990s: from 7 between 1991 and 2000, to 14 between 2001 and 2010, to 26 from 2011 to 2020, which constitutes a rise by a factor higher than 1.8.Footnote 62 P5 disunity in recent years is far from being absolute, as illustrated for instance by the UNSC's ability to deploy a peacekeeping force with a robust mandate to Mali in 2013.Footnote 63 However, in other internationalised conflicts, such as in Syria, Libya, or Yemen, its paralysis has been reminiscent of Cold War times.Footnote 64 UN mediators have consequently often lacked the necessary support for their peacemaking attempts from within the UN.Footnote 65

Ideational dimensions of multipolarity: Decline of liberal order

Shifts in polarity also have ideational dimensions. In a unipolar world order, the ideology of the main power dominates. Indeed, in the unipolar post-Cold War period, the US upheld a liberal order characterised by economic openness, security cooperation, and democratic solidarity.Footnote 66 As UN mediation enacts the prevalent norms in world politics,Footnote 67 it too became dominated by a liberal approach. Such a liberal approach to mediation is based on the belief that democracy is indispensable for sustainable peace and manifests itself in the attempt to broker a peace agreement that foresees a democratic transition.Footnote 68 Peace agreements signed under UN auspices in Angola (1991), Cambodia (1991), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (2002/03), for instance, foresaw elections and a democratic transition aiming at changing states and societies according to liberal values.Footnote 69

Yet, liberalism can only survive as a global ideational system if there is a liberal superpower upholding it by bearing the costs for public goods, enforcing its rules, and combating competing ideologies in other countries.Footnote 70 The willingness of the US to uphold the liberal order has been waning.Footnote 71 This is exemplified for instance by the former US President Trump's credo to ‘put America first’,Footnote 72 withdrawing from multilateral agreements, such as the Paris Agreement or Open Skies Treaty, and cutting funds to several UN agencies.Footnote 73 While the administration under Joe Biden has verbally recommitted the US to multilateralism, its retreat from Afghanistan and the clear rejection to intervene against Russia in Ukraine indicate an end to its willingness to uphold the liberal order through military engagements in foreign territories. In the meantime, the actors who fill the normative vacuum left by the US promote alternatives to the liberal order.Footnote 74 China, for example, limits liberalism to principles of economic openness and fundamentally questions the political system of liberal democracy. Internationally, its scepticism towards norms, such as the responsibility to protect or human security, puts key tenets of the liberal order into question.Footnote 75 Its rise is therefore likely ‘to dilute the liberal color of internationalism’.Footnote 76 Other rising powers have also expressed discontent with the norms of the liberal governance system.Footnote 77 Thus, a higher degree of normative pluralism characterises the multipolar world order.Footnote 78

This influences UN mediation because it produces alternatives to the liberal approach to mediation, emanating predominantly from states. In recent years, Turkey, Iran, and Russia brokered ceasefires in Syria, while Turkey and Russia proposed their mediation in the Libyan conflict,Footnote 79 and Russia offered to mediate in the Yemen conflict.Footnote 80 Competition to UN mediators has been present since the end of the Cold War,Footnote 81 with a growing number of actors offering mediation, such as states,Footnote 82 individuals,Footnote 83 non-governmental organisations,Footnote 84 and regional organisations.Footnote 85 However, in a unipolar world order, it came mostly from like-minded actors who subscribed to the notion that a democratic transition is indispensable for sustainable peace. In a multipolar world order characterised by normative pluralism, however, competition increasingly comes from actors proposing a different approach to mediation.Footnote 86 Indeed, in contrast to the types of peace agreements mediated by the UN, actors such as Russia, Iran, and Turkey, do not necessarily pursue the liberal goal of enabling a democratic transition in their peacemaking efforts. UN mediators are thus confronted with alternative approaches and face competition from without the UN.

The above shows that in terms of macro-level factors, the shift towards multipolarity has two dimensions (see Figure 2): First, material dimensions in the form of increased geopolitical competition that leads to disunity among the UNSC P5 and thus to reduced support for UN mediators from within the UN. Second, ideational dimensions in the form of a declining liberal order that enables alternative approaches to mediation and thus increased competition to UN mediators from without the UN. In the following, I will explore how these dynamics influenced the micro-level factors in Syria and therefore mediation outcomes.

Figure 2. Detailed conceptual framework on macro- and micro-level factors influencing UN mediation outcomes.

UN mediation in Syria

Micro-level explanation

The UN Secretary-General mandated three Special Envoys to mediate in Syria between 2012 and 2018: Kofi Annan, Lakhdar Brahimi, and Staffan de Mistura. However, none of them managed to broker a peace agreement. Scholars have suggested micro-level factors to explain this outcome. In terms of process factors, they analyse particular mediators’ styles or traits, such as the mediator's leverage or impartiality,Footnote 87 and regarding conflict factors, they point to the lack of ripeness of the Syrian conflict.Footnote 88 In particular, the absence of the parties’ sustained consent to the mediation process is often mentioned as a main cause for the ineffective mediation outcome.Footnote 89 The Syrian opposition initially refused to agree to a mediation process with Assad, but nuanced this precondition as it became clear that his departure was not guaranteed. The Assad government, in turn, lost interest in genuinely participating in mediation after receiving decisive military support from Russia in September 2015, which paved the way for its military victory.

These micro-level factors are of central importance in explaining the lack of mediation success in Syria. However, they are influenced by structural dynamics of world politics and therefore need to be complemented by an understanding of macro-level factors. In other words, the unsuccessful outcome of the UN mediation in Syria was not only due to micro-level factors, such as the disputants’ lack of willingness to engage, but also due to structural factors that impeded the UN from relevantly influencing these aspects. In the following, I analyse these dynamics in-depth by showing how geopolitical competition and the declining liberal order led to reduced support to UN mediators from within the UN and increasing competition from without the UN, and how this impacted mediation outcomes in Syria. Figure 3 presents the conceptual framework applied to the case of Syria.

Figure 3. Conceptual framework applied to case of UN mediation in Syria.

Macro-level complement

UNSC P5 disunity: Reduced support from within

UN mediation in Syria reflected geopolitical competition and the ensuing UNSC P5 disunity. At the onset of the Syrian armed conflict, the P5 were divided based on whether they favoured regime stability or change. Russia and China argued for respect of national sovereignty and opposed any form of external intervention.Footnote 90 The military intervention in Libya consolidated this position as Russia and China felt that Western states had used a Chapter VII resolution invoking the protection of civiliansFootnote 91 for regime change purposes.Footnote 92 Especially for Russia, the Syrian conflict was a forum to reassert its great power status in competition with the US. Indeed, its military intervention rendered it highly prominent as it gained decisive influence over the Syrian government, positioning itself as an actor ‘without whom the Syrian question cannot be resolve’.Footnote 93 The US, the United Kingdom, and France (P3), in turn, supported the opposition's regime change agenda. US President Barack Obama, for instance, called on Assad ‘to get out of the way’ in 2011.Footnote 94 This division among the P5 remained throughout the conflict, even if the forcefulness with which Western states demanded regime change declined in the face of the government's increasing likelihood to win the war militarily.Footnote 95 While there were moments of convergence between the US and Russia, discord dominated, illustrated by the fact that 12 out of the 19 resolutions vetoed between 2011 and 2018 were on Syria and all involved a negative vote by Russia.Footnote 96 Given the lack of conflict parties’ sustained consent to the talks, the UN mediators’ only leverage would have come from the UNSC in terms of united support or even a decision on coercive means, such as sanctions, a no-fly zone, or a weapons embargo. Yet, this was not forthcoming and left the UN mediators powerless in the face of a stalling political process. An overview of the three mediators’ efforts to make peace in Syria illustrates this.

Kofi Annan was Special Envoy for Syria from March to August 2012, with a joint mandate from both the UN and the League of Arab States (LAS).Footnote 97 Trying to forge consensus among the divided P5, Annan hosted the Geneva I conference bringing together key regional and international actors to discuss the Syrian conflict. The attendees adopted the Geneva Communiqué on 30 June 2012, which foresaw a political transition with a Transitional Governing Body to be formed in Syria. As this had wide-reaching implications including a transferral of power, the Syrian government's acceptance of the Communiqué was indispensable. Thus, a UNSC resolution endorsing the Geneva Communiqué was important to confer onto Annan the necessary leverage to foster the parties’ consent to it. Yet, the P3 wanted to add teeth to the document and insisted on integrating it into a Chapter VII resolution, authorising non-military sanctions under Article 41 of the UN Charter in case the parties did not respect it.Footnote 98 Russia and China vetoed the resolution fearing that it could become a slippery slope for military intervention, as in Libya, and hence play into the Western regime change agenda. Recognising the lack of P5 support, Annan withdrew from his role as UN-LAS Joint Special Envoy for Syria over the resolution's rejection. In his resignation speech, he said that ‘when the Syrian people desperately need action, there continues to be finger pointing and name-calling in the Security Council'.Footnote 99

Lakhdar Brahimi was the UN-LAS Joint Special Envoy for Syria from September 2012 to May 2014. The P5 remained divided and both Russia and the US spoke out more fervently in favour of their respective allies. Russia said in December 2012 that there was ‘no possibility’ to persuade Assad to leave Syria.Footnote 100 The US put its full weight behind the opposition by recognising the Syrian National Coalition of Revolutionary and Opposition Forces (SOC) as the legitimate representative of the Syrian people in December 2012.Footnote 101 It also announced that the Syrian government's use of chemical weapons would prompt serious consequences from the US.Footnote 102 When the Syrian government crossed this red line by using sarin gas in the Damascus suburb of Ghouta in August 2013, the US and Russia shared an interest in avoiding US intervention.Footnote 103 This enabled the UNSC to pass resolution 2118 on 27 September 2013, in which it finally endorsed the Geneva Communiqué negotiated under Annan and foresaw political talks.Footnote 104 The so-called Geneva II conference took place in early 2014, but did not produce any results.Footnote 105 When the fleeting US-Russia rapprochement reversed itself over Russia's annexation of Crimea in early 2014, Brahimi resigned. As one interviewee mentioned, ‘Brahimi knew that he was going nowhere after the Ukraine crisis happened because the US and Russia would not talk to each other anymore, even less about Syria'.Footnote 106

Staffan de Mistura was the UN Special Envoy for Syria from September 2014 to December 2018. Divisions among the P5 persisted, but in late 2015, Russian and US interests converged momentarily. Russia's willingness to find an agreement increased as they expected Hillary Clinton to win the upcoming US elections leading to a tougher US stance on Syria. The US was also willing to engage in talks because Assad's immediate departure became less of a priority as the rise of IS had transformed him into the lesser of two evils.Footnote 107 This convergence allowed for the passing of UNSC resolution 2254 on 18 December 2015, which led to the so-called Intra-Syrian Talks that started in January 2016 and consisted of several rounds of proximity talks.Footnote 108 Yet, in September 2016, the US and Russia fell out yet again after the US air force had attacked government positions in Syria, claiming to have been aiming at IS targets. Russian and Syrian government forces subsequently attacked a UN aid convoy.Footnote 109 Russia also intensified its military intervention, supporting the Syrian government in regaining key territories, most importantly Aleppo in December 2016. Moreover, US President Trump ordered the first US military airstrikes on Syrian government targets in April 2017 after a chemical attack in Khan Shaykhun. The P5 were thus fundamentally divided again. Without the support of the UNSC, de Mistura could do little to move the process forward and the talks stalled. Reflecting on the process, he said: ‘when the US and Russia agree and have common interests, then everybody else agrees too because they are powerful enough to prevent spoilers … But they need to agree'.Footnote 110

The consequence of P5 disunity was that none of the three UN mediators had the leverage to engage the conflict parties in meaningful negotiations. The Syrian opposition and the government could stick to their preconditions or stalling tactics with the mediators having no means to convince them otherwise. In other words, the macro-level factor of geopolitical competition influenced micro-level factors because P5 disunity led to reduced support to mediators from within the UN and limited their leverage to forge the parties’ consent to find a peace agreement.

Alternative approaches: Competition from without

The UN mediation in Syria also illustrates the impact of the declining liberal order and ensuing alternative approaches. The UN approach to mediation in Syria was liberal, as it explicitly called for a democratic transition. The Geneva Communiqué negotiated under Annan foresaw a political transition that would lead to democratic elections. Brahimi followed the same path by calling for a democratic transition and UN-supervised elections. Finally, under de Mistura, UNSC resolution 2254 that enabled the Intra-Syrian Talks set a schedule for holding ‘free and fair elections’.Footnote 111 The UN thus focused on a liberal transition, including democratic elections.

Given increasing multipolarity and a declining liberal order, the UN was confronted with alternative approaches to its mediation.Footnote 112 Russia became a key player in that regard, wanting to ‘impose its view on the conflict settlement’.Footnote 113 In December 2016, Russia and Turkey proposed to their Syrian allies, the government and the opposition respectively, to continue negotiations outside the UN framework. In early 2017, Russia, together with Iran and Turkey, sponsored a meeting between the Syrian government and representatives of the armed opposition in Astana (today Nur-Sultan), which started the so-called Astana Talks that subsequently continued over several rounds.Footnote 114 During the fourth round of the Talks in May 2017, the three guarantor states signed a memorandum of understanding to create four ‘de-escalation zones’ in which a ceasefire would be respected.Footnote 115

The approach taken by Russia in Astana stood in contrast to the UN's liberal approach as it did not aim at a democratic transition, but instead at containing violence through de-escalation.Footnote 116 As one interviewee stated, Astana ‘was conceived as primarily a space for military negotiations … and not a space for political negotiations’.Footnote 117 Russia's goal was to end the war by keeping the regime in place.Footnote 118 Indeed, while the de-escalation zones negotiated in the Astana Talks initially led to a reduction of violence and improved humanitarian access,Footnote 119 they favoured the Syrian government's interests as the ceasefires allowed it to regain strategically important territories.Footnote 120 By mid-2019, the government was in control of three of the four de-escalation zones, cementing its military victory and thereby further reducing its willingness to make concessions at the negotiating table.Footnote 121

The UN was forced to position itself in relation to this alternative format. It depended on Russia who had become the only player with significant leverage over Assad.Footnote 122 Indeed, there was a clear understanding that without the help of Russia, the Syrian government would not consent to any political process.Footnote 123 In the end, de Mistura attended the Astana Talks, but branded them as complementary to the UN-led process, underlining that Astana would cover the military aspects related to a reduction of violence while the UN would still be in charge of the political process. Trying to keep the legitimacy of the UN-led process, he said that ‘only the UN has the legitimacy and credibility needed for a viable, enduring political solution’.Footnote 124 Yet, in adhering to such a position, he increasingly lost exactly this legitimacy in the eyes of both conflict parties. Regarding the Syrian government, de Mistura's insistence on a democratic transition stood in contrast to the military situation on the ground, which was tilted in favour of the government. This made him prone to accusations of favouring a solution in line with the P3's regime change agenda. For the opposition, de Mistura's acquiescence to the Astana Talks hampered the perception of him as an impartial mediator, especially as it became clear that the de-escalation approach favoured the Syrian government. One interviewee expressed these circumstances in the following words: ‘the Special Envoy … attended the Astana Talks while on the ground, … we are seeing Russians and Iranians and the regime taking more territories’.Footnote 125 This led to a perceived de-legitimisation of the UN as a peacemaker.Footnote 126 Summarising the situation, a respondent remarked that ‘the legitimate process has de-legitimized itself and legitimized other processes that are not legitimate'.Footnote 127

The above shows how the macro-level factor of a declining liberal order influenced micro-level factors because alternative approaches to peacemaking led to competition from without the UN and undermined the UN mediator's legitimacy to forge the parties’ consent to find a peace agreement.

Conclusion

This article analyses the impact of world politics on UN mediation by studying the interaction between macro- and micro-level factors. It argues that multipolarity has both material and ideational dimensions manifested in a resurgence of geopolitical competition and a declining liberal order. This has engendered increased disunity among the UNSC P5 leading to reduced support to mediation from within the UN and has enabled alternatives to the liberal peacemaking approach resulting in competition to UN mediation from without the UN. These processes have led to a weakening of the UN as a global peacemaker, rendering it unable to broker a peace agreement in Syria.

The article contributes to the existing literature in two ways. First, it provides a systematic analysis of the link between world politics and UN mediation by complementing micro-level explanations for UN mediation outcomes with a macro-level perspective. Second, it allows for a better understanding of UN mediation in internationalised civil wars, and particularly in Syria, which has become a test case for UN legitimacy in contemporary peacemaking.

The article focused on the single case study of UN mediation in Syria as an example of internationalised armed conflicts. The empirical depth gained by such an approach comes at the cost of three main limitations, which provide avenues for further research. First, situating the Syrian armed conflict in the larger universe of internationalised civil wars, I argue that an analysis of UN mediation in other such conflicts is likely to yield similar results. Indeed, UN mediators in Libya and Yemen, for instance, also face UNSC P5 disunity and competing peacemaking attempts. Yet, detailed empirical insights on mediation in these contexts would be needed to test the generalisability of the findings in this article. Second, the article's findings do not necessarily apply to other contemporary conflicts where the vital interests of the most powerful states in the international system, particularly the P5, are not as directly affected as in the case of Syria. Extending the analysis to such contexts could provide additional theoretical insights on how the multipolar world order influences (or does not influence) peacemaking across contemporary conflict contexts. Third, the article focuses on mediation by the UN, whose efficiency depends institutionally on the convergence of P5 interests and whose approach reflects the prevailing norms in the international system. Other actors engaging in mediation, such as states, non-governmental organisations, or regional organisations, are less directly affected by P5 disunity and may themselves be drivers of alternative approaches to the liberal one. Examining how current world political changes influence non-UN mediation could yield interesting results and broaden the scope of the argument made in this article.

The article constitutes a first attempt at shedding light on the mechanisms through which macro- and micro-level factors interact in mediation. It will ideally encourage other studies on such factors to provide a complement to the current focus on micro-level aspects in mediation research. This additional layer of analysis is all the more important given its direct relevance to mediation practice. Indeed, a neglect of the structural context in which mediation takes place may result in ineffective or counterproductive policy recommendations. Scholars therefore need to provide sound insights on the implications of changing world politics in order to help the UN maintain its role in peacemaking in a shifting world order.

Acknowledgements

My heartfelt thanks go to the interviewees who provided me with their insights in a highly challenging context. I would also like to thank Ahmed Eleiba for his interpretation of interviews in Arabic and Ignatius Ivlev-Yorke and Arnaud Dürig for their research assistance. Special thanks also to Cedric de Coning, Dana Landau, Marie Lobjoy, Roland Paris, Jamie Pring, Alexandre Raffoul, Valerie Sticher, Xiang-Yun Rosalind Tan, and three anonymous reviewers for tremendously helpful comments on draft versions of this article. Research for this article was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and the project B/ORDERS IN MOTION (Tough Choices Cluster) hosted by the European University Viadrina.