It’s going to be a big, fat, beautiful wall!

Donald J. TrumpFootnote 1

A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever they may be, and not building bridges, is not Christian.

Pope FrancisFootnote 2

As Donald J. Trump’s presidential campaign graphically showed, walls are a hot topic: he promised to build a wall along the US-Mexico border – and to make Mexico pay for it. On his visit to Mexico, Pope Francis responded to Trump’s wall call by declaring that building walls is morally repugnant, while building bridges is the ‘Christian’ way.

Like the Pope, many critical intellectuals argue that such walls are not just a political problem, but a moral problem. Wendy Brown’s Walled States, Waning Sovereignty, for example, examines the theoretical politics of wall-building in the US and Israel, and concludes that these walls are both ineffective and immoral: walls don’t really keep foreigners out, and instead produce a xenophobic identity within America and Israel.Footnote 3 With few exceptions,Footnote 4 such criticism reflects the tone for discussions of border walls not just in the academy,Footnote 5 but also among public intellectuals in newspapers, magazines, radio/television, and popular non-fiction.Footnote 6

Indeed, the radical critique of walls as ineffective barriers that exclude vulnerable people on morally repugnant grounds is compelling. But rather than be satisfied with this moral critique, the article seeks to problematise the ‘political piety’ not just of moral judgements of walls as ‘good’, but also to interrogate the political piety of denouncing them as ‘evil’.Footnote 7 As we saw with George W. Bush’s post-September 11 foreign policy narrative, such moralising ‘rhetoric is an “analytical cul-de-sac” that prevents rather than encourages understanding’.Footnote 8 It tends to close down discussion, and thus reproduce the politics of domination.

This article, however, seeks to understand walls in a different register as political artefacts that embody political negotiations. While morality is singular and cannot be negotiated – walls either ‘good’ or ‘evil’ – once we recognise walls as sites of negotiation, then we likewise recognise that they can be renegotiated, which is a productive understanding of politics itself. Indeed, here we switch from partisan campaigning to figure politics in terms of cultivating a ‘critical attitude’ of self-reflection that goes beyond ‘merely serving particular social segments or disempowered groups’. Rather than stake out political positions, the goal here is to ‘displace institutionalized forms of recognition with thinking. To think (rather than to seek to explain) in this sense is to invent and apply conceptual frames and create juxtapositions that disrupt and/or render historically contingent accepted knowledge practices.’ Discussion thus can explore ‘a challenge to identity politics in general, … even those on which some social movements are predicated’.Footnote 9 The aim is to see how the walls are not simply physical barriers that exclude disadvantaged groups, but also to show how they ‘work’ to produce political meaning and political affect – and not necessarily the meanings and feelings that we’ve come to expect.

To do this, the article juxtaposes the American and Israeli walls with the Great Wall of China, the massive physical infrastructure that is celebrated in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as the positive symbol of the Chinese nation.Footnote 10 Mao Zedong told his compatriots: ‘You aren’t really a hero [haoHan] until you’ve climbed the Great Wall.’ China’s national anthem sings: ‘Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves! / With our flesh and blood, let us build our new Great Wall!’, and in 1984, Deng Xiaoping declared ‘Love our China, restore our Great Wall.’Footnote 11 As we will see below, the Great Wall is promoted as a symbol of the PRC’s morally superior ‘defensive’ foreign policy, and as evidence that China has never invaded any other country.Footnote 12 The Great Wall is more than China’s national heritage; it is ‘global cultural heritage’ that exemplifies a morally good foreign policy of peace.Footnote 13

The Great Wall juxtaposition can help us to challenge received wisdom – both conservative and critical – about border walls. Rather than reflections of clear territorial or social boundaries, the walls here are multiple and contingent artefacts that function more as complex sites of flow than as absolute barriers. Kafka’s short story, The Great Wall of China, discusses the Wall’s piecemeal jigsaw-like construction process as a critique of singular coherent narratives: wall-building here creates more gaps than barriers.Footnote 14 The Great Wall of China thus shows how walls can take on meaning through creative destruction: discontinuous construction, destruction, and reconstruction that animates more fluid inside/outside dynamics.Footnote 15

The Great Wall presents an interesting spatial (that is, non-Western) juxtaposition; it also shows how walls vary in meaning temporally: a century ago the Great Wall was understood in China as a monument to the wastefulness of tyrannical emperors, and/or as a useless ruin that didn’t border anything.Footnote 16 Now in the twenty-first century it is taken for granted that the Great Wall is morally good as a symbol of peace that benefits humanity.Footnote 17 This wall’s unstable historical meaning can provoke odd questions: in a hundred years, will Trump’s great wall likewise be celebrated around the world as the symbol of a defensive foreign policy that is morally exemplary? This outrageous idea recalls the shock Foucault experienced when he encountered the strange categories of a Chinese encyclopedia (as imagined by Borges): ‘the stark impossibility of thinking that’.Footnote 18

Certainly, these walls are different: the US-Mexico Barrier marks an actual interstate border, while the Great Wall of China is an archeological ruin and historical curiosity that doesn’t mark sovereign space. Yet when figured as a political artefact,Footnote 19 the Great Wall can tell us much about human relations; it also can tell us about how people relate to the material culture of massive infrastructure projects as visual artefacts that provoke affective responses – even exciting the sublime. Indeed, the Great Wall keeps appearing at China’s borders as a sign of sovereign power (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Immigration counter at Haikou International Airport, China (2016). Source: William A. Callahan.

The first part of the article uses the counter-example of the Great Wall of China to deconstruct the ideology of post-Cold War walls like the US-Mexico Barrier. It probes this juxtaposition to show how: (a) walls actually can be instruments of security policy that is rationally sound; and (b) how wall-building in both China and the US emerges from prior moral judgements that continue to produce the moral problems of exclusion. While critical IR generally understands walls in terms of the tension between absolute barriers at sovereign borders and neoliberalism’s unrestrained flows of goods and capital, this article employs the new conceptual framework of ‘gaps’ to explore how walls work as gateways that are neither completely closed nor completely open.Footnote 20 Critical borders studies scholars have profitably explored how borders are not static, and can take on meaning through movement and flows: borders here are no longer just at the edge of the nation-state, but are complex sites of flows, often throughout society.Footnote 21 Interestingly, though, this research agenda has not been applied to analyse border walls, which characteristically are figured as static barriers that ineffectively impede flows from without, while creating xenophobic homelands within.Footnote 22 In other words, in critical border studies walls generally are presented as a ‘problem’ that needs to be ‘solved’. This article, however, employs the ‘gaps’ concept to explore how walls themselves can be productive sites of movement, flows, and exchange that complicate problem/solution figurations.

While the first section employs the ‘critical juxtaposition’ of the Great Wall of China and the ‘conceptual frame’ of gaps to rethink border politics, the next section explores another conceptual frame to understand walls in a different register: specifically, it switches from a hermeneutic approach to a critical aesthetic strategy that values detailed empirical study and creative visual analysis of political events. The goal is to appreciate the visuality and materiality of walls as non-narrative sites of bodily and emotional provocation, moving from ideology to affect.Footnote 23 Explorations of visuality often shift attention away from the state and official foreign policymaking to see how foreign affairs emerge through local, transnational, and unofficial Self/Other relations: the visual global politics of everyday encounters with walls as barriers and gateways.

To explore this critical aesthetic strategy, the article concludes with a discussion of short films about border walls and gateways, specifically Cynthia Weber’s We Are Not Immigrants films from the US-Mexico border and a Tecate Beer advertisement that aired in September 2016 during the US presidential campaign.Footnote 24 Here walls aren’t necessarily either the problem or the solution; rather, the goal is to encourage a greater appreciation of their political complexity and moral ambiguity as gateways that govern flows of goods, capital, ideas, and people.Footnote 25 By problematising political piety (both conservative and critical), the article hopes to understand walls in a different register as active embodiments of political debate – and of political resistance.

The Great Wall, of course, is not the only example that one could use to interrogate current criticism of post-Cold War walls.Footnote 26 This article examines Chinese examples because that is the author’s particular area of expertise. But as the article’s comparative analysis of walls will show, this research deploys unexpected juxtapositions and new conceptual frames to call into question any Orientalist regionalisation of international studies. Indeed, the hope is that this research will generate further studies of the global politics of walls that explore examples from other times and places.

Deconstructing the wall

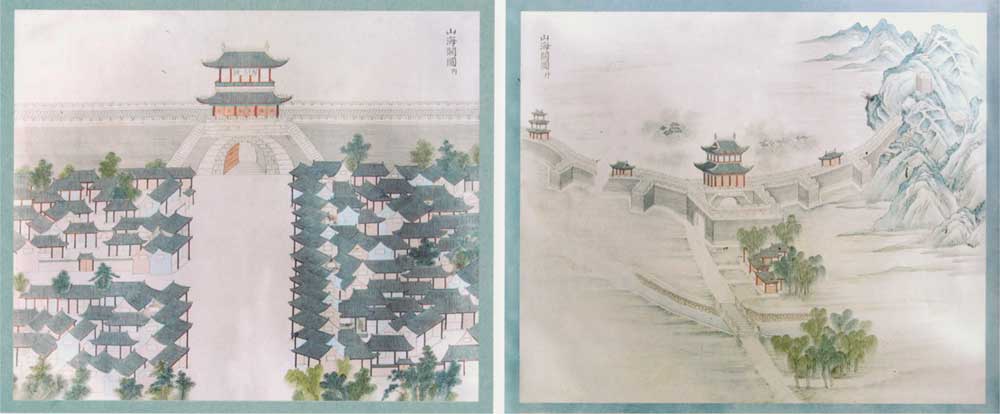

Walls are interesting because they are physical and symbolic sites of inclusion and exclusion that mark the inside from the outside. As R. B. J. Walker argues, inside/outside is the guiding distinction for international relations: it marks the distinction between domestic politics and international politics that is not only territorial, but also social: ‘inside’ denotes safety, law, and sovereignty, while ‘outside’ marks danger, violence, and anarchy.Footnote 27 This order-inside/wilderness-outside view of social life can be seen in an eighteenth-century silk painting of the Great Wall (Figure 2).Footnote 28

Figure 2 ‘Inside and Outside the Gate of Mountains and Seas’ (1760). Source: Collection of National Palace Museum.

The inside/outside distinction also emerged in 1961 when East Germany constructed the Berlin Wall to distinguish what it saw as its morally superior socialist ‘experiment’ from West Berlin’s morally corrupt capitalist ‘tumor’.Footnote 29 This territorial division soon came to symbolise the global Cold War ideological division between the communist East and the democratic West. Likewise, when the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, it was seen as a sign that the Cold War was over. This led to declarations of the end of history, the end of ideology, and a brave new borderless world. In the neoliberal era of globalisation, nations are not divided by walls, but joined by unrestrained transnational flows of goods and capital.

Why, then, do countries keep building walls? Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, many new walls have been built: not just in the US and Israel, but also both inside the European Union and at its edges, as well as in the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and East Asia. The end of the Cold War did not result in the final victory of neoliberalism and the ‘End of History’: rather, exclusive nationalism erupted first in many post-communist states, and now with the Brexit-Trump era in liberal democratic states as well. Walls therefore work as barriers to separate people, in what some see as a ‘disease’ and others as ‘apartheid’.Footnote 30

As Brown and others argue, these new walls speak to a number of contradictions. First, walls don’t work very well as a security strategy: with the new technologies of artillery and airpower, walls are obsolete as a military strategy. In the Second World War, the Germans just went around the Maginot Line to invade France, and then the Allies breached the Nazi’s Atlantikwall (Atlantic Wall) that was designed to seal off the Continent. The US and Israeli walls do not really ‘work’ either: they are functionally ineffective as barriers, and are very expensive.Footnote 31

Rather than seeing walls as something that states have built since ancient times, Brown argues that new walls in the twenty-first century are a new general phenomenon that lays bare the unique contradictions of our era.Footnote 32 While rationally we should see walls as a waste of time and money, Trump’s populist election campaign showed that they are very popular with the general public. For Brown, walls exemplify a crisis of sovereignty peculiar to the neoliberal era, where sovereignty has become unhinged from the state, and now has been relocated to transnational capital and transnational religious activity.Footnote 33

Many would counter that the new walls exemplify the global politics of the post-9/11 era: a resecuritisation of the state, and a rapid expansion of sovereign state power, not just in the US, but globally.Footnote 34 While the West is addressing the problems of neoliberalism, China, for example, is pursuing a combination of two illiberal ideologies – socialism and Confucianism – in what some call the neo-socialist ideology that cultivates expanded state power both at home and abroad.Footnote 35 This post-Cold War expansion of sovereign state power includes building the ‘Great Firewall of China’ to control cyberspace, as well as a new wall along the PRC’s external border with North Korea.Footnote 36

However, Brown is not persuaded by this argument: we are in what she calls the ‘post-Westphalian’ era where transnational capitalism uses the state to generate profits, while transnational religious groups are the main threat to state security. New walls exemplify the post-Westphalian shift in international relations from state-to-state conflict to transnational flows of goods, capital, ideas, and people. People here are not acting as agents of the nation-state, but as individuals and groups who cross borders as migrants, refugees, and terrorists: Mexican border-crossers are not pursuing Mexican state policy, and BP (formerly British Petroleum) doesn’t act in the interests of Great Britain when it spills/drills for oil in the Gulf of Mexico.

Brown argues that the new walls are not really meant to be material barriers, but are symbolic performances designed to deal with popular anxieties about the loss of sovereign power.Footnote 37 It’s a complicated argument, but in general, Brown sees walls as sites of ‘pure interdiction’ that contradict liberalism’s commitment to openness.Footnote 38 They are a site of ‘hypocrisy’ where liberal states break the law to enforce the law: to stop illegal immigrants, states build walls that actually require them to break other laws.Footnote 39 Hence walls exemplify the crisis of the liberal values of ‘universal inclusion, equality, liberty, and the rule of law’.Footnote 40

It is a technical, economic and political issue, but for Brown and many others wall-building ultimately is a moral issue: the wall is a blank screen upon which people project their anxieties over the erosion of state sovereignty.Footnote 41 Walls therefore aren’t a material expression of sovereign power, but rather a sign of the loss of power, and a loss of sovereignty. Instead of asserting strength, walls are a symptom of vulnerability and anxiety. They don’t really keep foreigners out, and instead produce a racist and xenophobic homeland within. Recall how Trump declared the necessity of walls when he announced his presidential candidacy: ‘When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with them. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.’Footnote 42

Walls are less physical constructions than they are symbolic social borders that need to be deconstructed for the proper understanding of their hidden ideology. Brown employs a robust example of hermeneutic analysis to reframe walls from concrete material infrastructure to be symbolic sites of the ‘bordering process’.Footnote 43 The goal for hermeneutics is to trace patterns of signification, and thus show ‘how the text can be understood in terms of the hidden content it discloses’.Footnote 44 For visual politics, hermeneutics is useful for revealing who is left out of political debates: who is visible inside the frame, and who is invisible outside, who is included inside the wall, and who is excluded outside the wall. Walls here are like visual artefacts more generally, which take on meaning through ‘social construction’.Footnote 45 Indeed, one of hermeneutic analysis’s key contributions is highlighting – often visually – the plight of vulnerable people on the Other side of the wall. Like in much of critical IR, the target of criticism is the sovereign state, and walls are prime examples of its exclusionary security practices. The political subject is not the citizen but the migrant, and walls are illusions that hide dominant ideology.Footnote 46

The goal here is emancipation: to demolish the ideological, social, and physical walls that separate humans from each other. Indeed, one of the strategies for resisting the US-Mexico Barrier is to artistically tear down the wall: for example, Mexican-American artist Ana Teresa Fernandez ‘erases the border’ by painting the wall with the landscape that it blocks (Figure 3).Footnote 47 Walls, as an overwhelmingly visual policing of social distinctions, both exemplify social exclusion, and distract us from the truth of power as domination.

Figure 3 Ana Teresa Fernandez, ‘Erasing the Border, Performance at Tijuana/San Diego Border’ (2010). Source: Gallery Wendi Norris.

To draw such conclusions, Brown looks to a few Western examples to make a general argument about sovereignty, and its demise.Footnote 48 She is clear about not being concerned with the specifics of particular walls – indeed, her passing reference to the Great Wall of China locates it in the wrong region: South Asia rather than East Asia.Footnote 49 While Brown doesn’t see the need to look beyond her Western liberal democratic examples, she suggests that ‘someone should’.Footnote 50

Accepting Brown’s invitation, the article looks to Chinese experiences as examples of a different relation to walls as markers of community and security. While walls are an insult to liberal society, they are very popular in China:

‘Wall’ is what makes China, wall makes the city of Beijing, the Imperial City, the Forbidden City, and all subsidiary units down to country town, village, and private home. Give any Chinese some loose bricks and he will build a wall, a gate, and hire a gatekeeper to prevent an outsider from entering. … The Great Wall is the symbol of China par excellence.Footnote 51

Indeed, as the classical Chinese philosopher Xunzi explains: ‘Wherein lies that which makes humanity human? I say it lies in humanity’s possession of boundaries.’Footnote 52

The Great Wall is not simply a site of military architecture; it is a site of identity politics that informs the definition of Chinese foreign policy as ‘defensive’.Footnote 53 The main security problem for premodern China was from the Central Eurasian steppe, and guarding the border along the Great Wall was a common solution. China’s military intellectuals argue that ‘without the Great Wall, China could never have survived as a unified state (Rome, it was pointed out, perished at the hands of barbarians)’.Footnote 54 The Great Wall, in this popular narrative, is exemplary because it shows how China did not expand, but merely sought to defend itself from foreign armies that attacked from the North. Responding in 2016 to the US Defense Secretary’s description of Beijing’s actions in South China Sea as ‘building a Great Wall of self-isolation’, the spokesman for China’s Ministry of National Defense explained, ‘as those who study Chinese history know, the Great Wall itself is a defensive strategy. It was built to keep out the cruel oppression of invaders, not friendly envoys or free trade.’Footnote 55 The Great Wall thus is taken as concrete evidence that China has never invaded any other country – and never will.Footnote 56

As well as a sign of defence, the Great Wall is also a symbol of diplomacy. In 1974, the PRC gave the United Nations a massive 36×16 ft silk tapestry of the Great Wall, which now hangs in the UN headquarters in New York. Great Wall tapestries also hang in the reception rooms of China’s embassies abroad, as well as in the entrance hall of the foreign ministry of one of Beijing’s key allies, Pakistan (Figure 4).Footnote 57 Visiting world leaders regularly make a pilgrimage to the wall: in 1972 Nixon declared ‘This is a great wall and it had to be built by a great people’, while in 2009 Obama mused that it is ‘magical’.Footnote 58 The Great Wall is ‘not just China’s national treasure, but shared or global cultural heritage’.Footnote 59 Rather than be a moral problem, the Great Wall is offered as a moral solution, again and again, not just for China, but also for the world.

Figure 4 Chinese ambassador gives Great Wall tapestry to Foreign Ministry of Pakistan (2014). Source: {http://pk.chineseembassy.org/chn/zbgx/t1126157.htm}.

China here is neither exotic nor unique. The Great Wall actualises the standard textbook concept of sovereignty, where one of the sovereign state’s necessary tasks is to guard its territorial borders – otherwise it is not sovereign.Footnote 60 Indeed, Mexico’s economy minister recently stated that ‘[t]he US is a sovereign nation and if the US decides to build a wall on the southern border, it’s their sovereign decision. We may like it or not … [but] we have to respect the sovereign act of a nation.’Footnote 61

The judgement of inefficiency – for example, that people can always climb over or tunnel under walls – also misinterprets the logic of walls as a security strategy: they are not meant to provide a hermetic seal, but to be part of a multidimensional strategy that includes patrols, drones, remote sensors, and other forms of surveillance.Footnote 62 The goal is not complete security, but ‘good enough’ security.Footnote 63 As the architect of the US wall built after 2006, Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, explains, ‘a fence is part of a whole strategy. A fence by itself is not going to work, but in conjunction with other tools, it can help.’Footnote 64 While it is common to deconstruct the ‘rationality’ of Realist foreign policy claims, this suggests that it is also necessary to deconstruct critics’ claims of the Wall’s ‘irrationality’. In other words, if it is broadly rational to safeguard one’s national borders, why is the US-Mexico Barrier so controversial?

Brown cannot appreciate the rationality of walls because she is employing a singular, absolute, and complete version of sovereignty that is taken from a survey of classical and contemporary political theory.Footnote 65 In International Relations theory, however, there are more nuanced notions of borders and sovereignty. While the argument about the post-Westphalian erosion of sovereignty assumes that sovereignty was ever solid, Walker argues that sovereignty has never been stable, and has always been problematic.Footnote 66 The problems of sovereignty are not simply post-Westphalian, but pre-Westphalian, and Westphalian also. Westaphalian sovereignty is an ideal that is never realised – but this is not necessarily seen as a failure of the system as a whole. Rather than speak of containment and impermeable barriers, it is common for critical IR theorists to recognise sovereignty as partial, overlapping, graduated, and even as an experience of ‘organized hypocrisy’.Footnote 67 Even so, it still is the job of the state to defend its borders – otherwise it is not sovereign. Thus the Great Wall of China can help us to rethink the politics and the morality of the US wall to reframe it as a defensive act.Footnote 68

If we step away from a condemnation of walls as immoral sites of separation, then we can examine not just what they mean, but what they can ‘do’. Rather than simply condemning exclusion, the Chinese practice of walling encourages us to look more closely at how the inside/outside distinction works as a ‘bordering process’:Footnote 69

Traditionally [the Great Wall] marks off the ‘sacred land’ (shenzhou) from the rest of the world. Walls are important to the Chinese because, over and above practical considerations (preventing thievery, resisting attack, and the like), the wall is the line clearly drawn between what is significant and what is insignificant, what is powerful and what is not powerful, who is kin and who is stranger, what is sacred and not sacred.Footnote 70

Understanding inside/outside as a complex and contingent relation is popular in critical IR literature,Footnote 71 and it is even more central to Chinese political discourse as nei/wai.Footnote 72 According to Metzger, conceptual dyads like nei/wai-inside/outside are key to social life in China, organising relations between individuals, families, clans, all the way up to relations between different peoples and different states. Rather than function according to the fixed binary distinctions characteristic of Enlightenment modernity, such dyads are relational, contextual, contingent and fluid, with a productive tension between the ideal and lived experience.Footnote 73 Indeed, while much critical analysis of walls focuses on etymological definitions and canonic texts,Footnote 74 what is most interesting about these Chinese dyads is the general lack of stable canonic definition: there is no orthodoxy, and the dyads’ contingent flexibility demands that we make sense of each dynamic through continual interpretive practice.Footnote 75

Civilisation/barbarism (Hua/yi) and loosening/tightening (fang/shou) are two other conceptual dyads that are key to understanding how walls work. Loosening/tightening is a contemporary Chinese concept used to describe the non-linear and non-progressive exercise of power seen in the PRC.Footnote 76 Although fang/shou generally describes a cycle of loosening and tightening of state control over society, often it was not simply a chronological shift from loose to tight and then back to loose again, so much as doing both simultaneously. As Deng Xiaoping declared, successful governance requires ‘grasping with both hands’ (liangshou zhua), with one hand grasping Beijing’s economic policy of ‘reform and opening’, and the other grasping political stability.Footnote 77

Such dynamic dyads resonate with Foucault’s concept of ‘governmentality’Footnote 78 because they shift us away from a blunt understanding of politics as the juridical power to say ‘no’, and towards a more nuanced sense of power as productively generated by social relationships. The issue is ‘no longer that of fixing and demarcating the territory, but of allowing circulations to take place, of controlling them, sifting the good and the bad, ensuring that things are always in movement’.Footnote 79 Governmentality and loosening/tightening help us to shift from seeing walls as sovereign barriers that separate and exclude the outside from the inside to appreciate how walls also can function as productive sites that regulate flows according to degrees of loosening/tightening. The governmentality of flows, which functions according to a loosening/tightening dynamic, is quite different from neoliberalism’s unrestrained flows of capital and goods.

Following recent developments in comparative political theory, this article resists the geopolitical container-style organisation of knowledge-production where the choice is between the ‘modern West’ and ‘traditional China’.Footnote 80 Rather than replacing ‘Eurocentric’ concepts with ‘Sinocentric’ ones, the article explores the political dynamics of walls through an assemblage of concepts that are Chinese, Western, traditional, and contemporary. The goal here is to use Chinese concepts, examples, and experiences as a critical juxtaposition that problematises the moralised discourse of walls as good or evil, and opens up space for a more nuanced appreciation of what walls can ‘do’. Hence, while the Pope distinguishes between morally good bridges, and morally evil walls, bridges often function like walls as key sites of the governmentality of flows. For example, traffic at the border between Hong Kong and mainland China at the Lo Wu Bridge waxes and wanes according to political season: it was busy in the 1950s, then narrowed to a trickle during the Cultural Revolution (on one day in 1970 only three people crossed this border-bridge, which was the only entry point to the PRC), and now it is the busiest border in the world.Footnote 81 This is a productive example of the shift from the stark binary inside-outside distinction to a more nuanced and contingent governmentality of flows.

The Great Wall of China, therefore, is not simply a defensive act. Like many walls, it was built to mark a moral distinction. It wasn’t built to defend an interstate border; rather, it was employed to operationalise another dynamic dyad, the Civilisation/barbarism distinction (Hua/yi), that governed premodern China’s political, moral, and literary discourse.Footnote 82 Rather than just being exemplary post-Westphalian phenomena, walls here are also pre-Westphalian events. To put it another way, we need to recognise how post-Cold War International Relations theory was not simply dominated by globalists. It also witnessed the backlash of essentialised identity politics, exemplified by Huntington’s ‘clash of civilizations’ thesis. Clash of civilisations is not simply a post-Cold War phenomena: in many ways, it reproduces a premodern notion of international politics that continues to be very popular in China and other non-Western countries.Footnote 83 However, rather than following Huntington to distinguish between different civilisations, Chinese texts characteristically distinguish between civilisation and barbarism. Indeed, the word for civilisation (Hua) is the same as the word for ‘Chinese’. Civilised China only takes shape when it is distinguished from barbarism, with ‘China being internal, large, and high and barbarians being external, small and low.’Footnote 84 This is not simply an ancient understanding: prominent Chinese scholars still argue that border walls, including the Great Wall, are ‘an indicator of settled social development, generally termed “civilization”’.Footnote 85

The Great Wall was an important part of policing this hierarchical and moralised social distinction. It was built to guard China from nomadic pastoralists of the Central Eurasian steppe. Although nomads regularly banded together into large armies, they generally did not present a state-to-state challenge to China, so much as the ecological conflict between settled farmers who formed states and mobile pastoralists who occasionally banded into confederations.Footnote 86 Wall-building then emerged from a Civilisation/barbarism distinction that violently creates, targets, and attacks the nomadic pastoralists as an invading barbaric horde. These political and moral distinctions could be harsh: the orthography of classical Chinese categorises many nomads as ‘animals’ rather than as fellow humans.

China’s hierarchical, exclusive, and morally superior understanding of walls is familiar. The Great Wall of China is a pre-Westphalian example of a strategy designed to address the security challenge of mobile non-state peoples, rather than interstate territorial conflict. Twenty-first-century walls likewise are designed to manage the post-Westphalian transnational challenge of flowing people rather than to mark fixed territory. Like Central Eurasian nomadic pastoralists, people at the US border – migrants, refugees, smugglers, and terrorists – are largely unorganised, and do not act on behalf of a state. Hence the Great Wall’s Civilisation/barbarism distinction resonates with Trump’s racialist description of Mexicans as barbaric criminals rather than as vulnerable migrants: ‘They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.’

While the Great Wall of China’s defensive foreign policy goal can be rationally exemplary, when probed more deeply its moral problems emerge. The division between civilised people and barbarians often became a racially-exclusive policing of the distinction between Han and non-Han social groups. Indeed, even Mao’s famous quotation about Chinese going to the Great Wall reflects this: haoHan means ‘hero’ and ‘good fellow’, but it also means ‘good Chinese’ – and ‘good Han’. Strangely, the wall that provokes moral outrage in the US and Israel, becomes the key to China’s exceptionalist moral superiority.

Hence this juxtaposition of walls can help us to understand US and Chinese foreign policy in new ways. On the one hand, the Chinese experience allows us to see walls as instruments of a security policy that is rationally sound: it is the sovereign state’s job to guard its borders, otherwise it is not sovereign. But because the Chinese discourse of Civilisation/barbarism is broadly analogous to the racialist distinctions that support the US wall, the Great Wall of China has moral problems as well. It is common to figure non-Western experience as either completely the same or completely different: for example, as derivative sites of ‘modernisation’ or as exotic alternatives. But this analysis shows how the juxtaposition of walls from different times and places can yield fruitful – and unexpected – insights.

From singular barrier to contingent gateways

Critiques of the US-Mexico Barrier and Israel’s West Bank Barrier often rely on a singular notion of walls, in both time and space. Walls have existed since the beginning of time as expressions of Western civilisation and/or Judeo-Christian theology that mark out sacred from secular space.Footnote 87 Here sovereignty is absolute, and borders are unproblematic single line boundaries. The US-Mexico Barrier is figured as a singular, coherent, unitary wall that sits exactly on the border, ranging from the Pacific Ocean in San Diego to the Gulf of Mexico in Texas.

Curiously, this unitary wall-scape is shared by supporters and critics alike. Supporters seek to build such an international hermetic seal; yet because the wall does not measure up to this unitary absolute singularity, critics declare it technically, economically, politically, and morally ‘ineffective’. Thus gaps are a problem for both groups. They need to be sealed for supporters, while for critics they are evidence of the deadly consequences of the wall’s failure: gaps in the wall redirect people from urban crossings towards the high desert plateau, which generates greater costs in terms of higher fees paid to human traffickers, as well as a higher death rate among migrants.Footnote 88 According to this argument, it’s all or nothing: walls are located along 100 per cent of the border, and work 100 per cent of the time – or they are useless.Footnote 89

The Great Wall of China generates similar discussions of unity and multiplicity, continuity and gaps. The textbook description of the Great Wall portrays it as a sign of the nation’s power, unity, and longevity.Footnote 90 The Great Wall was built by China’s first unified dynasty, and the Wall as a whole is presented as unified and continuous in space and time: it is thousands of miles long and thousands of years old, the largest and longest structure built by human beings, and the only manmade structure visible from outer space. As mentioned above, the Great Wall exemplifies the timeless history of a defensive foreign policy: against substantial historical experience to the contrary, we are regularly told that China has never invaded any other country – and never will.

Upon closer examination, it turns out that none of these statements is true. The current wall was built by the Ming dynasty five centuries ago, and was rebuilt by the PRC starting in 1952.Footnote 91 It is neither continuous nor visible from outer space. There are dozens of sections of the wall that do not line up into a single-line barrier (like from San Diego to Brownsville, Texas). Until recently, we didn’t even know the wall’s basic statistics: China’s State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping completed the first archeological survey of the Great Wall in 2012, concluding that it is a massive 21,196.18 km in length.Footnote 92 But this survey raises more questions than answers because measuring the Great Wall is more than an empirical question: it is an epistemological problem in the sense that any definition of the Great Wall is unstable.Footnote 93 There is no single continuous Great Wall; rather there are dozens of discontinuous and overlapping walls, built at different times, by different peoples, for different purposes. Scholars deal with this epistemological instability in various ways: some use different terms to refer to the wall in different eras, while others simply pluralise the term: the Great Walls of China.Footnote 94

Likewise, the Great Wall’s morality is neither singular nor unitary. Until the twentieth century, it was seen in folk culture as an immoral artefact of the brutal tyranny of the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty (221–206 bce). One of China’s most popular folk tales, the story of Lady Meng Jiang, describes the wall as a site of cruelty and suffering because it is built on the bones of conscripted labourers.Footnote 95 The Great Wall here is immoral not because it excludes vulnerable Others,Footnote 96 but because it brutalises Chinese subjects.

Instead of seeking a more precise measurement of the Great Wall, and thus assert its unity and coherence in time and space, Carlos Rojas argues that we should celebrate its gaps, and use them to engage in a critical view of identity, territoriality, and politics.Footnote 97 Historically speaking, walls were not clear markers of Civilisation/barbarism. Han Chinese built walls against each other in the Warring States period (475–221 bce), and non-Han built their own walls to guard against Han in various periods.Footnote 98 Rather than reflections of clear territorial or social boundaries, the walls here are multiple and contingent artefacts. As suggested above, Kafka’s short story ‘The Great Wall of China’ appreciates the creative power of disjuncture by showing how wall-building creates more gaps than barriers. Walls take on meaning through creative destruction: discontinuous construction, destruction, and reconstruction that animates more fluid loosening/tightening, inside/outside and Civilisation/barbarism dynamics. The Great Wall of China thus can be experienced as an indeterminate challenge to the unitary and essentialised master narratives of politics, culture, and territory – and a challenge to abstract binary notions of sovereignty, borders, and walls.

Rather than understand walls as barriers that separate countries, territories, and populations, it is helpful to understand them as gateways that can join them.Footnote 99 Indeed, a popular Chinese idiom for inside or outside the Wall is actually inside or outside the gate or pass: guannei, guanwai. Alongside its work as military architecture, the Great Wall was a site of meeting and exchange. At the wall, China and its Northern neighbours fostered peaceful relations through trade, where nomadic pastoralists exchanged horses for Chinese grain, metalwork, and handicrafts. As a former Chinese foreign minister explains:

the Great Wall of China, while safeguarding the Chinese people, also served as a meeting point for economic and cultural exchange between China and the countries on the other side [that] … increased its friendly relations with other nations.Footnote 100

The silk painting of the Great Wall in Figure 2 helps us to question many of the assumptions that we accept about walls as immoral barriers. It was created by a Korean artist, and presented by the Korean ambassador to the Qing emperor as a tributary gift. This image is painted from two perspectives: inside and outside the gate.Footnote 101 But rather than painting the ‘outside’ of wall in protest – as often happens at the US-Mexico Barrier and Israel’s West Bank BarrierFootnote 102 – this pair of paintings is a vassal state’s celebration of the sovereign power and cultural magnificence of the Chinese emperor as the Son of Heaven. In 2014, Beijing reasserted such wall-themed friendship diplomacy by giving its key ally, Pakistan, a silk painting of the Great Wall that hangs in the foyer of Pakistan’s foreign ministry (see Figure 4).

Certainly, gateways can include harsh checkpoints that actualise (im)moral judgements of Self and Other: Check-Point Charlie, the Palestinian checkpoints, and the US-Mexico border.Footnote 103 However, instead of understanding walls simply as blunt instruments of sovereign juridical power, it is helpful to think of power as productively generated by social relationships. In this way, ‘Israeli checkpoints, or the “Separation Wall” [that is, the West Bank Barrier], are no longer perceived as spaces of division and fragmentation, but can also be recaptured as “bridges” that connect invisible networks, space of livelihood, or collective spaces to dream.’Footnote 104 Hence rather than being seen as examples of barriers to neoliberalism’s unrestrained flows of goods and capital, walls can also provoke the new political dynamic of governmentality, where power is produced through the loosening/tightening of flows of goods, capital, ideas, and people.

Indeed, the first major wall-building project on the US-Mexico border was not called ‘Operation Barrier’, but ‘Operation Gatekeeper’ (1994). Although it is common to declare that the US wall is evidence of a progressive militarisation of the border, Luke argues that when compared with other countries, the US is actually an ‘underwalled state’.Footnote 105 Indeed, the wall itself tightens and loosens according to political season: the wall mandated by the Secure Fence Act (2006) was never completed. The Obama administration suspended construction in 2010 when the project ran out of funds.Footnote 106 Of course, the border is tightening now with Trump’s call to build a big, beautiful wall. But even here the moral arguments falter: when the Trump administration put out a call for bids to ‘design and build several prototype wall structures’, ten per cent of the responding contractors were Hispanic. According to The Guardian, there was some soul-searching, but in the end many Mexican-American contractors put moral issues aside and treated the wall as a business opportunity: ‘My goal is to build a wall so I can make enough money so we can turn this thing around and tear down the wall again.’Footnote 107

Instead of being the site of ‘pure interdiction’, here walls as gateways are contact zones, sites of markets and exchange where entry and exit are managed through the loosening/tightening dynamic. In the Palestinian feature film Omar (2013), for example, Omar’s love life is regulated according to the loosening/tightening dynamic of the West Bank Barrier that he has to climb over to visit his girlfriend.Footnote 108 While Omar certainly engages in armed resistance to Israeli occupation, the Wall here is treated not as an absolute barrier but as one of the many features that he has to creatively negotiate to get from here to there in everyday life. While contemporary critics see walls as a moral problem of clear divisions, where all selves are xenophobic in their division from the Other,Footnote 109 attention to this loosening/tightening dynamic shows how the power, unity, and even morality of the wall is produced at its gaps. Rather than being evidence of ‘hypocrisy’,Footnote 110 the wall’s contradictions are fruitful as ambiguous and multiple experiences of governmentality. The wall is not a simple moral outrage; rather it is a new economic and political opportunity that has been provoked by a recalibrated governmentality of flows.

From textualising the Wall to visualising the Wall

In China, wall-building characteristically arose from a hermeneutic approach to international politics. Premodern China is famous for its meritocratic civil service that valued ethical and literary knowledge more than hereditary lineage, but this otherwise admirable policy also produced particular political problems. Scholar-officials often discussed the Great Wall through texts and images that invoked the moralised Civilisation/barbarism distinction described above. Indeed, the oldest extant map of China, the ‘Map of Civilization and Barbarians’ [Huayi tu] (1136 ce) from the Song dynasty, famously includes the Great Wall as a unitary boundary between civilised China and the barbaric North (Figure 5). The problem with this very detailed map – and with much premodern Great Wall discourse – is that it is based on textual references, rather than on fieldwork-based ethnographic or geographic surveys.Footnote 111 Indeed, empirical research at the Great Wall was impossible at that time because Northern China was governed by the semi-nomadic Jurchen Jin dynasty (1115–1234 ce), which later conquered the Song. The hermeneutic approach that relied on moralised distinctions between civilisation and barbarism tragically narrowed the options for Chinese foreign policy to the containment or the extermination of nomads as ‘barbarians’.Footnote 112 This criticism of Chinese wall-building, however, is different from critiques of modern walls: rather than the issue being the moral problem of excluding vulnerable others in the US and Israel, the problem in China arose from how the practice of moralising the wall according to the Civilisation/barbarism distinction limited foreign policymaking options.

Figure 5 ‘Map of Civilization and Barbarians’ [Huayi tu] (1136 ce). Source: Library of Congress.

The Chinese problem of textualising the wall can help us to understand the weaknesses of current critiques of twenty-first-century walls. Brown’s main argument is not based on experience, interviews, or fieldwork; rather, as a leading political theorist she examines classical and contemporary texts for a conceptual discussion of walls and sovereignty. Yet this detailed theoretical analysis also shows the weakness of abstract discussion: while thick descriptions of specific events show the messiness of walls, hermeneutics reproduces the problems binary oppositions that add up to singular unity: Self/Other, inside/outside, and so on. As mentioned above, Brown posits the US wall as a single continuous structure that goes from beginning to end, and then criticises it for not living up to this ideological standard.Footnote 113

To explain the illusory power of walls, Brown recalls the story of the Wizard of Oz,Footnote 114 who appeared to be an awesome sovereign, until Toto tore away the curtain to reveal an anxious and vulnerable man. This illustrates the workings of hermeneutic interpretation, which aims to trace patterns of signification, and thus reveal hidden ideology. The lesson here is that walls themselves are secondary, ‘a derivative phenomenon’ that is the product of deeply embedded social contradictions.Footnote 115 The focus on reading walls as ‘texts’ reflects critical theory’s suspicion of images and other visual artefacts.Footnote 116 It is the job of critical scholars, according to the hermeneutics strategy, to deconstruct how state and corporate power use images to manipulate the general public.Footnote 117 Brown’s text is exemplary in its negative view of visuality: walls are criticised as ‘stages’, ‘spectacles’, and ‘screens’ that powerful people use to ‘theatricalize and spectacularize’ sovereignty in a ‘ritualistic performance’ that disguises hegemonic power and hides true intentions.Footnote 118 Walls are less physical constructions, than symbolic borders that are socially constructed, and thus need to be deconstructed for proper understanding.

Certainly, we can gain much by treating walls as ‘texts’ to see how they function as narratives of national identity, and resistance to it. But rather than just understand them as representations of narratives of sovereignty, identity, and security, a ‘critical aesthetic’ strategy helps us to see walls as a collection of non-narrative and non-discursive sites constructed to provoke emotions – pride, awe, disgust, outrage, and sadness – that are themselves political performances. Thus, if the article’s first shift of conceptual frame is from figuring walls as absolute barriers to see them as gateways of governmentality, then the second shift is from hermeneutic textual analysis to a critical aesthetic strategy that values detailed empirical study and creative visual analysis of walls as political events.

When we speak of ‘aesthetics’ in global politics, we are not discussing a theory of beauty, but are more concerned with styles of ordering that raise ethical questions.Footnote 119 The shift from exclusive binary oppositions to relational dyads that we saw above is one example of a critical aesthetic approach to probing the global politics of walls. While critics commonly figure walls as screens that hide true meaning and hegemonic ideology, this critical aesthetic strategy treats visuality as an opportunity, where screens and other visual sites are valued for their potential to excite ‘affective communities’.Footnote 120 Hence, in addition to employing hermeneutics to trace the ‘social construction of the visual’, we also need to appreciate the ‘visual construction of the social’, and especially how the visual can provoke new social relations.Footnote 121 In such a critical aesthetic mode, we move from seeing walls as material and/or symbolic barriers between pre-existing spaces to figure them as partitions not simply of space (for example, territorial borders), but as multisensory experiences of sight, sound, touch, smell that (re)partition the visible, the sayable, and the thinkable.Footnote 122 Resistance is not necessarily found in the emancipation of a wall-free borderless world – for example, the liberal victory of the demolishing the Berlin Wall. Rather resistance works in a different register that emerges through more nuanced repartitions the sensible that create new political dynamics, as well as new political problems. Politics here emerges less in the formal arenas of the struggle for state power, and more in the broader sense of shaping the parameters for what can (and cannot) be seen, thought, and done.Footnote 123

While explorations of ‘visibility’ help us to see how sovereign states socially construct walls to exclude the Other, explorations of ‘visuality’ often shift attention away from the state and official foreign policymaking to see how foreign affairs emerge through local, transnational, and unofficial Self/Other relations: the visual global politics of everyday encounters with walls as barriers and gateways.Footnote 124 Hence when we switch from hermeneutics to critical aesthetics, it is possible to revalue walls as visual performances that are filled with possibilities that are not simply morally evil, but can be morally good – or morally ambiguous. Rather than focus on what walls don’t do – that is, their inefficacy, their immorality – this strategy examines what they can ‘do’ as material infrastructure that moves people emotionally and politically – as well as spatially.

The critical aesthetic strategy is helpful for understanding the Great Wall as a non-narrative and non-discursive artefact and experience. In addition to understanding the Great Wall as a text that we can deconstruct to understand ideology, it is also an affective experience that inspires non-narrative and non-discursive awe. For many it is an ‘[a]we-inspiring fragment of something much larger, more complex and contradictory’: the Great Wall is often described as a magnificent dragon gracefully flowing through the steep hills and deep valleys of Northern China.Footnote 125 According to Brown’s understanding, however, twenty-first-century walls are awesome only in a negative way: the US wall is a ‘behemoth’, while the Israeli wall ‘snakes’ rather than dances through the hills.Footnote 126 These contemporary walls are examples of the hegemonic militarized power of ‘shock and awe’.Footnote 127

The Great Wall, on the other hand, can approximate the sublime. Kant uses a beautiful/sublime distinction to explore judgement, where the beautiful refers to ‘the form of an object, which consists in having boundaries’. The object is beautiful here because it is harmonious, and therefore is pleasurable within accepted measures of judgement. The sublime, however, appeals to the ‘momentary arrest of our interpretive faculties’ that excites a shock that can be both horrible and pleasurable.Footnote 128 While the beautiful inspires ‘restful contemplation’, the sublime excites movement, a vibration ‘quickly alternating attraction towards, and repulsion from, the same Object’.Footnote 129 The sublime can emerge through a relational mode of creative/destruction. A violent thunderstorm is an experience of the mathematical sublime: it is so ‘absolutely large’ that it causes us to turn inward, encouraging critical reflection.Footnote 130 In the dynamic sublime, we ‘recognize the fearfulness of nature without fearing it’, and so elevate our imagination beyond the boundaries of common sense.Footnote 131 The Great Wall does not have the destructive power of a violent storm, but it does work on a massive scale. Even in its fragmented state, the wall’s spatial and temporal expanse cannot be comprehended as an individual experience. As Rojas explains, the ‘great’ in the Great Wall is the sublime: first as the symbol of territorial, ethnic, and historical boundaries, and then as the experience of boundlessness: it is thousands of miles long and thousands of years old.Footnote 132

To understand how walls can be sublime, it is helpful to change our perspective from looking at the wall perpendicularly – that is, the hermeneutic project of giving voice to vulnerable others on the Other side of the wall – to looking along the wall itself.Footnote 133 Here we see not just the clear boundary between civilisation and barbarism, but can also experience the sublime boundlessness of the wall dancing its way through the hills like a mystical dragon. Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s ‘Project to Extend the Great Wall’ (1993, Figure 6) was an explosive public art event that celebrates the mystical nature of the wall.Footnote 134 While Fernandez paints a peaceful landscape on the US-Mexico Barrier to ‘erase the border’ (see Figure 3), Cai’s pyrotechnic art lit up the night sky to violently extend the western terminus of the Great Wall by ten kilometers. Cai’s art thus speaks to the creative/destruction and boundary/boundlessness of the sublime wall.

Figure 6 Cai Guo-Qiang: ‘Project to Extend the Great Wall’ (1993). Source: Cai Guo-Qiang.

While Brown sees massive walls as symbols of the loss of sovereignty, in China the Great Wall was built as a ‘major project-dashi’ to demonstrate the awesome power first of the premodern state, and since 1952, the awesome power of the PRC. Beijing continues this tradition through other twentieth-century-style megaprojects: the Three Gorges Dam, the world’s largest high-speed rail network, manned-space flights, and the new domestically-built aircraft carrier. The wall likewise is ‘comprehensible’ as an ‘accessible fragment of the infinite’.Footnote 135 It is an experience of the sublime because it is disruptive, evoking ‘pain, opposition, constraint, and discord’.Footnote 136 The sublime thus does not provide emancipation from the ‘moral problem’ of walls; rather it allows us to appreciate their affective power as material performances that can excite political resistance in a different register. Much like Kant’s understanding of the sublime as ‘ever being alternatively attracting and repelling’,Footnote 137 China’s most famous modern writer Lu Xun concludes: ‘The Great Wall of China: a wonder and a curse.’Footnote 138

Visibility and visuality at the US-Mexico Barrier

This concluding section will re-vision walls in ways that appreciate the productive tension between hermeneutics and critical aesthetics, narrative and non-narrative, ideology and affect, the quotidian everyday and the boundless sublime, and ultimately between understanding global politics in terms of visibility and visuality. Here we recall the debate about the relation between word and image.Footnote 139 While hermeneutics privileges the verbal, and affect theory the visual, some theorists seek to see visual artefacts in terms of a combination of word and image. For example, through his appreciation of Japanese calligraphic paintings, Roland Barthes proposes a new form of critique where ‘[t]he text does not gloss the images, which do not illustrate the text. For me, each has been no more than the onset of a kind of visual uncertainty …’.Footnote 140 Rancière likewise aims to loosen the hierarchy of word over image by figuring the relation as a contingent dynamic so as to probe ‘the relationship between the visible, the sayable, and the thinkable’.Footnote 141 Mitchell suggests that we think in terms of ‘image-texts’, because ‘all media are mixed media’.Footnote 142 Since words and images are in an ‘infinite relation’ where ‘neither can be reduced to the other’s terms’, Foucault argues that we should treat this ‘incompatibility as starting point, rather than as an obstacle’.Footnote 143

Weber’s pair of We Are Not Immigrants (2016) films about the US-Mexico border exemplify such productive tensions.Footnote 144 One film is narrative and the other is non-narative. Both films address questions of visibility and visuality: the visibility of who is (not) allowed to cross the border, and the visuality of the anger, frustration, fear (and occasional joy) that the everyday border-crossing experience excites.Footnote 145 In many ways, Weber’s films illustrate critical theorists’ hermeneutic critique: they show the progressive militarisation of the US-Mexico border, and the moral problems this barrier creates for disempowered people who need to cross the wall. It is an ethnographic approach in the traditional sense: the first film explores the experience of people from the Pascua Yaqui Nation, a Native American tribe whose organic community has been divided by the border’s arbitrary barrier. The indigenous community’s leader, José Matus, makes a verbal critique – ‘We are not immigrants!’ – and narrates the injustice produced by the wall that separates him from his cousins on the Other side of the border.Footnote 146

But the film also offers a visual critique: it shows Matus not just at the boundary between the US and Mexico, but at the wall between his sovereign indigenous nation and the sovereign nation-state of the US. Rather than an imposing wall that is an outrage to liberalism, this wall is 2.5 meters high, and has an open and unguarded gate. Matus shows its fluidity by stepping inside and outside the border of his indigenous community, in an expression of his own sovereignty (Figure 7). Here, like with the Great Wall of China, it is the gaps that produce meaning – and a meaning that is not singular but ambiguous. Like with many indigenous groups, here claiming and performing sovereignty is the goal rather than the problem.

Figure 7 Negotiating a border wall. Source: Cynthia Weber, We Are Not Immigrants (film, 2016).

The second film in the We Are Not Immigrants pair is non-narrative and non-linear. It is designed for display in an art gallery, and employs three side-by-side screens that flash in and out: sometimes three images are screened in parallel, but at other times only one or two are shown. It works according to an aesthetic of loosening/tightening: the three 4x3 spaces enact the openness of broad landscape that typifies the high desert, but the flashing black spaces also point to tightening. The film has an affective rhythm, but no linear narrative: there is no beginning or end – it is designed to be screened in a loop. Scenes from the first film of the frightening experience of crossing the border are reproduced here: we see imposing, armed, border patrol officers ‘policing’ the border by demanding documents with a threateningly official politeness, again and again.

But there are new clips as well, which provoke affect in different ways. Indeed, both films highlight how the wall is not the site of ‘pure interdiction’, but a gateway of governed flows that is a site of exchange, play, and enjoyment. One sequence shows a party at the border, complete with a Tecate Beer tent and children playing volleyball over the wall, while a border patrol SUV drives by on the American side.Footnote 147 The experience thus can be sublime: the horrible police state alongside a pleasurable fiesta where the wall is as much a gateway as a barrier. While Brown is very serious about the ideology of the wall, here We Are Not Immigrants allows a more ambiguous and creatively sublime appreciation of what the wall can do. Indeed, it shows how walls not only separate people, but also can bring them together as ‘a catalyst to promote cross-border cooperation’.Footnote 148

With the nastiness of Trump’s wall-policy in mind, this argument is difficult to sustain. Walls are still an expression of post-sovereign and post-Westphalian power that is a moral outrage. Still, Trump’s wall-building campaign has provoked interesting reactions. Alongside Pope Francis’s serious moral chastising of Trump, a Mexican beer commercial offers a creative critique that is both sharp and playful. It starts with the familiar birds-eye view of the US-Mexico barrier as an ominous monument to racist separation: snaking through the extreme frontier of the Tecate desert, it is sublimely terrible.Footnote 149 The narrator declares in an aggressive tone that ‘It’s time for a wall, a tremendous wall, the best wall!’, with the film showing four Mexicans and four Californians confronting each other at the wall. The advertisement then dramatically shifts perspective in terms of both tone and scale. The wall, it turns out, is only two feet high. The narrator declares with glee: ‘The Tecate Beer Wall. A wall that brings us together. This wall might be small, but its going to be YUGE!’ The Mexican and Californian men go from mutual enmity to mutual amity with hugs, handshakes, and fist-bumps. The awesome wall is brought down to earth, and re-visioned on a more human scale, as a long, thin table that facilitates beer drinking. More importantly, the Mexicans share their Tecate Beer, and the Californians jump over the wall in celebration to join the party on the Other side. Like in Weber’s second We Are Not Immigrants film, the party at the border involves drinking Tecate Beer in playful community. As the commercial’s narrator concludes: ‘You’re welcome, America!’

Certainly, we can see this as another example of the post-Westphalian/post-sovereign era: the transnational corporation Heineken, which owns Tecate Beer, employed the global PR firm Saatchi and Saatchi to set the political agenda in terms of buying more beer.Footnote 150 But I think that this playful thirty-second advertisement is fruitfully pregnant with reversals and contradictions. And it is even political in the sense of partisan campaigning: it premiered in September 2016 during the first presidential debate on Fox News, Univision, and Telemundo. More importantly, it shows ‘play’ in the sense of both ludic action and flexible plasticity: the wall brings together as well as separates.Footnote 151 It creatively combines visibility and visuality in a multidimensional sensory experience that needs not only to be unpacked for political meaning, but also appreciated for political affect. Rather than political piety, here we have moral ambiguity at the wall.

While many critical theorists understand twenty-first-century walls in terms of the tension between ‘pure interdiction’ at sovereign borders and neoliberalism’s unrestrained flows of goods and capital, this article uses unlikely juxtapositions (the Great Wall of China) and new conceptual frames (gaps, critical aesthetics) to argue that walls are better understood as gateways that are neither completely closed nor completely open. Walls here function through a loosening/tightening governmentality of flows, where politics emerges in a different register to produce resistance through new political dynamics, which in turn generate new political problematics. By putting moral questions to the side, for a moment, the article aims to understand walls in a different register as active embodiments of political debate – and of political resistance.

Acknowledgements

For their comments and help with this article I thank the editors and reviewers of RIS, Elena Barabantseva, Franck Billé, Roland Bleiker, David Brenner, Kevin Carrico, Carina Chotirawe, Cho Young Chul, Andrew Dellatola, Simon Glezos, Mark Hoffman, James Leibold, Timothy Luke, Aaron McKeil, Guanpei Ming, Naruemon Thabchumpon, Pinitbhand Paribatra, Tansen Sen, Michael J. Shapiro, Kaat Smets, Verita Sriratana, Vira Somboon, Christian Wirth, Jinghan Zeng, and the participants in the Asian Borderlands Research Network conference (2016).