Introduction

Covert action is generally understood as state activity to influence conditions abroad where it is intended that the role of the sponsor will neither be apparent nor acknowledged publicly. Footnote 1 From Russian interference in the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections to American support for Syrian rebel groups, covert action has featured prominently in recent international security discourse. As the United States debates the merits of covert action against Iran, and covert competition with China, critics fear that it is back on the agenda.Footnote 2

The impact of covert action, and intelligence more generally, on international relations is under-theorised.Footnote 3 Evaluating the success of covert action, especially intangible influence operations, poses significant challenges – something that even those with full access to classified records agree.Footnote 4 Nonetheless, such challenges, including how to isolate agency and measure effects, do not prevent observers from labelling particular operations as successes or failures.Footnote 5

Under-theorisation poses a significant intellectual and policy problem. Failing to recognise the subjective nature of judgements when evaluating actions can lead to unrealistic expectations about what covert action can – and cannot – achieve as a policy option. Overestimating the ‘hidden hand’ can lead to conspiracism about foreign actors, undermine trust in democratic institutions, and provide a convenient scapegoat for domestic divisions. At the same time, ‘success’ in covert action can today be publicly contested as never before. The advent of new information and communication technologies and consequent proliferation of narratives about foreign policy events allow citizens to scrutinise and debate policy decisions, including covert action past and present, in myriad ways.Footnote 6 As scholars of policy evaluation note, ‘claims of policy success and counterclaims of policy failure have become a key currency of political competition’.Footnote 7 Put simply, it is imperative to interrogate the dynamics of ‘success’ when debating the use of covert action.

Our argument here is as follows. First, under-theorisation creates confusion about what constitutes success. Second, covert action is elusive – and not just because of secrecy. It is difficult to contain conceptually and analytically. As a consequence, perceptions are equally, if not more, important than actual outcomes and impact. Either way, outcomes and impact are constructed and continually debated by researchers, journalists, practitioners, and policymakers. Success is neither binary nor exogenous to covert action. A successful covert action is one that has been labelled a success by salient observers – and that label has stuck. Interestingly, both sponsor and target have incentives to collude in the construction of success.

To advance our argument, this article deconstructs covert action success. It begins by critically reviewing ‘success’ in the existing literature before developing an intersubjective model to demonstrate that success is multidimensional, interpreted, and constructed through discourse. We then offer a definition of success that draws out, and makes coherent, diverse existing assumptions, before applying this to a case study of the CIA's ‘golden age' of covert action.

Covert action ‘success’

The consensual definition of covert action highlights two key criteria. Covert actions are an instrument of foreign policy (they seek to influence events abroad) and the sponsor is unapparent or unacknowledged.Footnote 8 Research on covert action tends to focus on three broad types of activities presented according to their degree of violence: propaganda; political action, such as funneling money to a political party or fomenting riots; and paramilitary action, from training insurgent groups to assassination.

Not all states use covert action, and those that do conceive of this practice in different ways. The US approach highlights ‘plausible deniability’ – a doctrine that allows senior officials neither to confirm nor deny responsibility for covert actions.Footnote 9 Soviet officials used the term ‘active measures’ to cover a broader spectrum of overt and covert activities, and have more readily embraced implausible deniability.Footnote 10 Although far more restrained, the British similarly blur the boundaries between covert action and routine foreign policy as well as between intelligence coverage and so-called ‘effects’.Footnote 11 French practitioners do not use the term covert but talk about action clandestine, and their dedicated unit – Service Action – specialises in paramilitary operations.Footnote 12 These linguistic and organisational variations reveal that government officials conceive of a relatively common set of practices differently.

Like definitions of covert actions, knowledge of the operations themselves is in many ways socially constructed. The US approach has dominated scholarly research and affected common understandings of covert action. This has led to an exaggerated importance of plausible deniability, too stark a divide between overt and covert activity, and, when dipicted through the media, to a simplistic conception of covert actions as discrete operations with clear beginnings and ends. In reality, in countries where US covert actions pursued regime change during the Cold War, internal dissent coexisted with external covert sponsorship making it difficult to isolate the covert action and its impact. Covert action often complements larger overt state action, and it is misleading to narrowly focus on the former in analysis. In fact, a guiding principle of CIA covert action is that, to be effective, it must harness existing conditions in a target and must be accompanied by broader US diplomatic effort. As a result, covert action and its parameters are difficult to contain analytically.Footnote 13 This is problematic because how scholars define covert action and its parameters impacts upon how they evaluate its effects and success.

Armed with more historical evidence than ever before, International Relations scholars are increasingly examining the role of covert action as a form of state intervention. They interrogate, among other matters, the causes and conduct of covert regime change,Footnote 14 the role of secrecy in foreign policy and statecraft,Footnote 15 and the relationship between covert action and democratic norms.Footnote 16 Despite such progress, the literature offers little explicit investigation of a fundamental question: how to define success?

One means used to assess – or more often demonstrate – success is through counting outputs. For propaganda operations, this includes the number of articles surreptitiously placed in foreign newspapers; for political action, the amount of bribery undertaken; and for paramilitary action, the number of terrorists killed by drone strikes. Practitioners, often trying to quantify success in order to attract more funding, tend to use this approach. For example, the Reagan White House evaluated covert action against the Soviets primarily by monitoring distribution of propaganda material.Footnote 17 These outputs offer a limited understanding of success; they struggle to account for the impact achieved. Relying on them achieves little beyond allowing those conducting the covert action to claim success.

Intelligence scholars working on covert action think carefully about how to ensure success. The literature offers important insights into factors that improve chances of success,Footnote 18 whether covert action can be just,Footnote 19 and how to ensure effective oversight of covert actions.Footnote 20 Much of this discussion involves checklists to ensure success rather than breaking down what constitutes success in the first place. Instead, success is implicit in an amorphous range of indicators. These include legality, alignment with national security interests and foreign policy objectives and values, whether covert action is appropriately funded, reasonable probability of success, whether methods are commensurate with objectives, whether local actors have input on outcomes, and whether intelligence officials have properly assessed the risks involved.Footnote 21

These checklists are important – especially at the operational level – and speak to various dimensions of success and their political ramifications. However, they are under-theorised: resting on implicit assumptions of success and struggling to reveal or explain how it is constructed. The relationship between some indicators (such as legality and vague notions of ‘values’) and success is not explicit, while other indicators (such as the probability of success or consequences of failure) rest on assumptions of success and failure that are not explicitly defined leaving a circular argument. Perhaps most importantly, these checklists lie in tension with the more explicit, rationalist, and narrow understanding of success that most scholars eventually fall back on: whether, as the CIA's chief historian, David Robarge, put it, covert action accomplished the policy objectives it was intended to help implement.Footnote 22 However, this is itself problematic in so far as it captures only a slice of the many other aspects linked to success, such as legality and values, implicitly underpinning the covert action checklists. It further assumes a rational state that defines clear and measurable policy objectives and links them to covert actions before conducting them.

A recent quantitative turn advances the rationalist approach to measuring outcomes against objectives further.Footnote 23 These studies offer useful findings that can then inform judgements of success. They ask important questions about the longer-term consequences of covert action, even if those consequences are empirically narrow (such as impact on levels of democracy or occurrence of militarised conflict).Footnote 24 However, they too suffer limitations not least in treating the initial success or failure of each covert action in a binary manner from which longer-term effects are then derived, and in making assumptions about objectives, temporal parameters, and agency of each covert action.Footnote 25 This can undermine claims about effects, potentially leading to a false sense of certainty.

Overall, covert action literature is under-theorised and struggles to articulate success in an explicit and coherent manner. Some works recognise amorphous normative factors, but most fall back on rationalist attempts to measure outcomes against objectives. Almost all take a positivist approach, seeing success and failure as independent from authors’ and key stakeholders’ knowledge of a covert action, and hence objectively measurable. Analysis often takes ‘success’ as self-evident, focusing instead on causes or consequences, and lessons to be learnt. There is little attempt to question ontological and epistemological assumptions, or to recognise the importance of competing perceptions and power relations.

The conventional approach underplays the subjective nature of success as a judgement or label rather than an inherent attribute. Judging success by measuring outcomes against objectives is analytically problematic, not least because policy goals can be ambiguous and shift over time. This is especially the case in the realm of covert action because of the ambiguities in planning created by the need for secrecy.Footnote 26 Even the existence of presidential findings – a form of directive used since 1974 to justify US covert actions to Congress – did little to provide clear and measurable goals against which to judge success. For example, a declassified 1980 finding authorised covert action ‘for the purpose of resisting Cuban supported … subversive and terrorist activities in Honduras’.Footnote 27 How much resisting constitutes success?

Other declassified documents relating to this operation discuss intercepting the flow of arms through Honduras and preventing the establishment of guerrilla infrastructure.Footnote 28 Although this gives sense of ‘how’ the objective is to be achieved, the prioritisation of tasks and possible measures of success are not specified. How much interception of arms and prevention of infrastructure constitutes success? In such cases, practitioners and scholars are left unable to judge what exactly should be achieved and tempted to impose their values ‘to make it possible to compare performance with aspiration’.Footnote 29 To further complicate matters, according to a former senior CIA counter-terrorism officer, measuring success of a covert action frequently becomes an emotive issue for those in Congress responsible for its oversight. They ‘want’ to see an action they have supported succeed – using whatever favourable metrics are available.Footnote 30

Foreign policy scholarship usefully emphasises the objective and subjective nature of success. Dominic Johnson and Dominic Tierney use the term ‘score-keeping’ to describe assessments that focus on material gains and losses, and the achievement of material aims. Any examination needs to take into account the respective importance and difficulty assigned to gains and aims – which adds subjectivity. Observers interpret the importance and difficulty of aims and gains, but ‘cannot say for sure that one material gain is more important than another’.Footnote 31 Having employed a benchmark for success – usually a perception of the objectives and what success would look like against them – policy evaluators then assess incoming information to determine whether this has been achieved. Both of these perceptions suffer cultural, political, and psychological biases that scholarly analysis should seek to identify.Footnote 32

An evaluation model for covert action

To address these issues, we adopt an intersubjective approach, which explores how particular understandings and interpretations of realities are constructed and legitimated to become a dominant discourse. Intersubjective scholarship recognises that success is constructed as a political act, as a label to be applied rather than objective facts exogenous from the policy events observed.Footnote 33 Success is not an inherent attribute of policy but a judgement about policy that exists through discourse. This judgement is a complex process compounded by ‘wildly different perceptions and post-hoc inquiries often accused of politicization and bias’.Footnote 34 An intersubjective approach therefore studies ‘how something comes to be seen’ as a ‘success’.Footnote 35

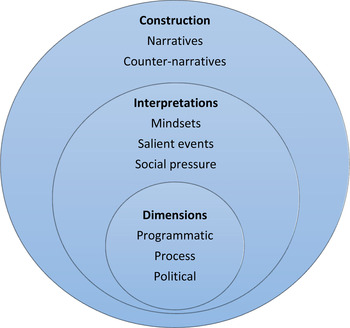

We develop a model to evaluate covert actions by revealing how they came to be seen as successes. Figure 1 represents this model as three concentric circles. The circle at the core distills three dimensions of ‘success’: programmatic, process, and political.Footnote 36 Despite hinting at these different dimensions, most intelligence literature falls back on programmatic evaluation and struggles to reconcile tension between the three. Our framework makes these differences explicit and distills them to increase conceptual clarity and coherence.

Figure 1. The social construction of success.

The programmatic dimension of success covers whether a covert action met its objectives, which can be tactical or strategic, the gains made, and the impact achieved. Used on its own, this approach is problematic because it is difficult to measure objectively and lies in tension with normative and ideational definitions of success.

Process success refers to the manner in which the state went about achieving policy objectives. Process can create or undermine legitimacy and is therefore an important marker of success. It includes whether a covert action was planned inside approved channels; whether it enjoyed a broad coalition of support among those who ‘needed to know’; and whether bureaucratic infighting delayed or altered a covert action.Footnote 37 Beyond planning and authorisation, a process failure might involve the operation going wrong somehow, whether by breach of secrecy, death, arrest of an agent, or an unfavourable impact on cognate activities such as intelligence gathering. This dimension also includes factors such as lesson learning and innovation,Footnote 38 both of which are significant for covert actions that rely, to an extent, on experimentation, creativity, and trial and error. Many of these are implicitly recognised in the checklists prevalent in the existing literature. For example, scholars such as Loch K. Johnson and James Barry,Footnote 39 as well as practitioners such as William Webster,Footnote 40 emphasise the importance of authorisation, oversight, and legal review in liberal democracies.

Political outcomes for both the sponsoring state and target populations offer a third dimension of covert action evaluation. Success affects the electoral prospects or reputation of a sponsoring party and is indicated by ‘political upheaval (press coverage, parliamentary investigations, political fatalities, litigation) or lack of it, and changes in generic patterns of political legitimacy (public satisfaction with policy or confidence in authorities and public institutions)’.Footnote 41 This is implicit in the above-mentioned checklists too, for example in alignment with ‘values’ and whether the covert action is acceptable to the broader public if exposed. Political evaluation is particularly important regarding covert action given the controversial nature of the subject. Covert action can be perceived as a political success if it enhanced – or at least did not damage – the reputation of the sponsoring government at home and abroad and/or it did not generate so much domestic criticism that it damaged its ability to govern.Footnote 42

The second circle of our framework shows how observers interpret these three core dimensions. Here the model draws on Johnson and Tierney to emphasise how observers’ mindsets, salient events, and social pressures shape their evaluation. Mindsets are the product of constraints on information processing, emotional states, past experiences, and cultural tradition. Salient events, such as the elimination of a leader and the overthrow of a regime, can have disproportionate effects on perceptions of victory or success. Social pressure, in the form of elite, media, and in our case intelligence agencies’ manipulations, influences perceptions of success and the relative value observers ascribe to various dimensions.Footnote 43

Perceptions of success and failure are not just shaped by material realities, but also by ideational factors. Ideational factors form the building blocks of competing interpretations of covert actions, which are observable through narratives and counter-narratives. The third and broadest circle in Figure 1 is where multiple interpretations are actuated and become visible through narratives of ‘success’ and counter-narratives of qualified success or failure. This level uses scholarship on narrative analysis to offer insight into how a covert action came to be seen as successful – and by whom. It focuses on how evaluation is enacted by analysing the constitutive parts of a compelling story: its setting, characters, and plot.Footnote 44 Each part − shaped by mindsets, salient events and social pressures − influences perceptions of programmatic, process, and political outcomes. Audiences have traditionally understood covert action as stories, but scholarship on covert action has shied away from examining who tells these stories, and how elites frame their settings, characters such as allies and enemies, and plots or crises.Footnote 45

Following the narrative turn in foreign policy analysis, our framework places perceptions at the centre of evaluations of success by drawing attention to the way in which salient actors interpret events and how cognitive and cultural aspects frame understanding of outcomes in international politics. Competition between narratives and counter-narratives eventually leads to some form of consensus – a dominant narrative – and one interpretation of events as a success or failure becomes social fact.Footnote 46 A dominant narrative is one that resonates with salient observers in the society of the sponsoring country and in other relevant societies, for example in the target state, but also in allied and adversary countries.Footnote 47 Such observers can be construed as an elite that includes intelligence practitioners and policymakers with access to information who speak from a position of political authority and legitimacy to a large audience; journalists who speak to a similarly large audience; and, to a smaller extent, scholars who influence the intellectual debate. Dominant narratives, more than material realities, determine the extent to which covert actions are constructed as successful for a certain period of time.Footnote 48

A covert action is successful when salient observers judge that an operation met the goals that proponents set out to achieve; when these judgements have stuck; and when there is minimal criticism of the way the state achieved this and of the political consequences. Minimal criticism among relevant domestic and international audiences is a sign of narrative dominance. For example, a minority of observers could consider that an action is more of a failure by giving prominence to the negative effects it had on the politics of the target country as opposed to those of the sponsoring country. However, the limited number and reach of such critiques would not be sufficient to seriously challenge and overturn the dominant narrative of success and the sense of legitimacy this helps state actors to establish.Footnote 49 If criticism becomes more widespread, because of new evidence or sociopolitical trends, it might eventually turn what was perceived as a qualified success into a form of failure.Footnote 50 These discursive dynamics tend to favour binary categorisation. It is easier, more gripping, and impactful to frame a story as a success or a failure from which a moral should be drawn. The case for lessons to be learnt is less likely to convince when the action was neither a success nor a failure. In practice, however, the existence of multiple narratives suggests that most successes and failures are qualified. Having outlined a new framework for evaluating covert action, the article now turns to a single case study to develop it.

The ‘golden age’ of CIA operations

The so-called ‘golden age’ of the CIA, which lasted from its establishment in 1947 to the failed invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961, is useful to demonstrate how a series of covert operations came to be seen as successful. Our case study selection follows a convenience sampling strategy that focuses on a prominent case. CIA covert actions are by far the most well known and publicly discussed. This can be related to the interventionist trend in US foreign policy, but also to the relative transparency of its intelligence community, which facilitates scholarly research, and to the reach of American spy fiction, which draws public attention.Footnote 51 This means that a wealth of material is available to examine discourses on covert action from the perspective of salient observers in government (through archives and public statements), the media (we restrict our analysis to press coverage) and academia. The ‘golden age’ is remembered as a period in which the Agency used a range of covert methods, from propaganda and political influence to paramilitary activity, to support US foreign policy goals. Specifically, we draw on three of the most well-known CIA ‘successes’: attempts to influence the Italian elections in 1948, the Iranian coup of 1953, and the 1954 Guatemala coup.

The conventional narrative of CIA ‘success’ proposes a well-known script. The CIA covertly interfered in the Italian elections to prevent a communist-dominated popular front from defeating the pro-Western government. This included covert propaganda, from coordinated letter-writing campaigns to forged documents, and covert funding of the Christian Democrat Party, alongside extensive overt efforts such as attempts to link future US aid to the defeat of the communists. The Christian Democrats won the election.

In August 1953, the US and UK covertly sponsored the removal the Iranian prime minister, Mohammad Mossadeq. The British had begun to subvert his government back in autumn 1951, after he nationalised Iranian oil, and then joined forces with the Americans in spring 1953. The operation involved bribing army officers, journalists, and politicians; covert propaganda; and assembling thugs to demonstrate against Mossadeq. It initially unravelled, but, after a few days of confusion, Mossadeq was arrested.

The following year, the CIA sponsored a coup replacing the democratically elected Guatemalan leader, Jacobo Árbenz, with a military dictatorship. The CIA funded, armed, and trained a paramilitary force and then used psychological warfare, including a black radio station, to amplify its successes and intimidate the government. Although the paramilitary force achieved little material effect, Árbenz resigned in June 1954.

It is helpful to consider these operations together because their position relative to each other in the chronological narrative of the CIA perpetuates an impression of success. Historians traditionally perceive Italy as a springboard to bigger operations, such as Iran. Guatemala was approved following the Iranian ‘success’ and directly influenced a host of other operations.Footnote 52

The phrase ‘golden age’, denoting success and free rein, appeared in newspaper articles as early as the 1960s,Footnote 53 and then scholarly works from the late 1980s into the 2000s.Footnote 54 CIA veterans have also referred to a ‘golden age’,Footnote 55 while the CIA uses the expression – albeit carefully – to refer to the directorship of Allen Dulles (1953–61): ‘his tenure is often said to be a “golden age” for CIA’.Footnote 56 In 2009, the CIA's chief historian wrote that the ‘the CIA enjoyed what was widely regarded as a “golden age”’ in the 1950s, largely owing to it ‘its perceived operational prowess’.Footnote 57 Overall, as one historian put it, ‘the argument that the 1950s served as a form of ‘golden age’ for the CIA – has come to dominate historical, and indeed cultural, representations of the Agency's role in the early Cold War era.’Footnote 58

The ‘golden age’ has had a long afterlife in the public discourse of US intelligence, continuing to set the CIA as an important and historically powerful actor in international affairs. In short, it became social fact. To unpack this construction our analysis now turns to narratives – and related interpretations – of programmatic, process, and political success. We focus on narratives primarily because they are the most apparent and visible way in which mindsets, salient events, and social pressures come to frame different dimensions of success.

The dominant narrative of success

The dominant narrative of the ‘golden age’ is set in the context of the so-called Cold War consensus, which pits an aggressive and expansionist communist bloc led by the Soviet Union against the free world led by the United States.Footnote 59 This interpretation marginalises both the view that the United States overstated the Soviet Union's expansionist threat and the impact on domestic populations in target states.

The specific covert actions that contributed to this ‘golden age’ also have their own settings. Geographically, narratives focus on planning in Washington, and on US presence in or around the target country. Temporally, dominant narratives use beginnings and ends – by no means inevitable – which emphasise CIA gains, power, and impact. For example, beginning the Iranian coup with President Eisenhower's green light in spring 1953 rather than UK subversion in autumn 1951 bestows greater ownership of the covert action upon the CIA. Beginning the Guatemala narrative in the early 1950s overlooks a ‘centuries-old cycle of progressive change and conservative reaction’, thereby overplaying the narrative of an unprecedented communist attempt to target a country in the US backyard.Footnote 60 The setting also frames a specific set of policy parameters: the dominant narrative tends to focus on the covert rather than the overt action it complemented. This overplays the impact of covert activity despite the difficulties in knowing whether it was the covert action that provided a margin in, say, Italy rather than the much larger overt programme of US support, not least through the Marshall Plan.

Lead characters in ‘golden age’ covert actions tend to be US policymakers and CIA officers. They are often portrayed – whether critically or supportively – as powerful, enjoying minimal oversight, and getting the job the done. American intelligence officer Kermit Roosevelt, for example, went off script and acted without authorisation as the Iranian coup unravelled but is remembered for improvising a solution. For Gregory Treverton, one of the most influential writers on covert action, ‘Roosevelt turned what might have been a disaster in Iran in 1953 into stunning success.’ This success was partly because, again according to Treverton, the CIA ‘sees itself as being in the business of taking risks’. Footnote 61 The CIA mindset and bureaucratic interests shaped its own narrative of success by emphasising process and programmatic achievements. By contrast, intelligence historians traditionally portray Prime Minister Mossadeq as a pajama-clad effeminate and the shah as an oscillating Hamlet figure.Footnote 62

The setting and characters shape the plot: the CIA successfully interfered in each country. The CIA achieved a set of programmatic successes, demonstrating operational gains, potency, and impact. There is remarkable convergence here even among competing narratives. On Italy for example, journalists and political activists criticise CIA operations; former CIA officers celebrated them; while scholars sought to place them into a chronology of Cold War covert actions as a successful precursor to bigger operations. Crucially, all three groups do not question programmatic success (for better or worse), ignoring the counter-narrative that maybe the covert action was programmatically ineffective.Footnote 63

Assessments of the actual impact of CIA interference on the election are therefore ‘largely irrelevant’. Even as internal CIA historians, with access to all records, still argue about impact, the broader narrative is far more important: ‘In Washington's collective imagination, the CIA had rescued Italy's democracy.’ As the historian David Shimer notes, ‘No proof was needed. America's preferred party had won.’Footnote 64

The same applies to the bolder actions in Iran. The dominant narrative – agreed by diverse audiences in both America and Iran – has long been one of programmatic success: the US successfully removed Mossadeq.Footnote 65 This narrative developed through accounts by highly salient characters including the CIA's chief of the Near East and Africa division, Kermit Roosevelt; the MI6 chief of station in Iran, Montague Woodhouse; and an influential CIA planner, Donald Wilber. Each source is questionable on its own, but together they were able to establish a narrative of programmatic and process success, and it is of little surprise that the power of American agency quickly dominated history. Counter-narratives, that internal forces were equally if not more important than covert action in engineering the coup or that the operation was an initial failure, struggled to gain traction.Footnote 66

In Guatemala, local scholars and journalists subscribed to the dominant narrative of US programmatic success even before details of US involvement came out in the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 67 For Árbenz, mere knowledge of US involvement – however ineffective – was a critical factor persuading him to give in.Footnote 68 Influential literature in the 1980s perpetuated the narrative of CIA power.Footnote 69 Interestingly though, the material achievements were arguably far more limited – the official history admits that the CIA had a poor understanding of internal Guatemalan affairs, especially within the army officer corps. ‘Just as the entire operation seemed beyond saving, the Guatemalan Government suddenly, inexplicably collapsed. The Agency never found out why.’ Crucially, CIA officers obscured such failings and replaced them with the legend that Árbenz ‘lost his nerve’ in the face of the American propaganda.Footnote 70 Officials’ mindsets, reflective of a Cold War setting that framed Árbenz as a communist alongside the desire to champion American prowess, were crucial in shaping the success narrative.

Drawing on a wide range of secondary literature, O'Rourke claims ‘US policymakers were enormously pleased with the intervention, and they revived some of its techniques during subsequent missions in Brazil, Bolivia (twice), British Guiana, Chile, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Panama.’Footnote 71 For many in the US intelligence community, Guatemala ‘nurtured a sense of infallibility’.Footnote 72 The coup therefore became a success not because it liberated Guatemala from a mostly imagined communist threat, but because a critical mass of salient actors subscribed to the CIA narrative.

Mindsets, salient events and social pressures explain why this dominant narrative of programmatic success took hold across different operations and competing groups. Mindsets included US officials’ beliefs about the communist threat, the purpose and prowess of the CIA, and experience in each operation (which then informed the next). Even after the end of the Cold War consensus and ‘golden age’, the narrative of power and success continued – including among those criticising US excess. For example, the Church committee – named after Senator Frank Church (D-ID) who chaired this Senate select committee set up to investigate CIA and other intelligence agencies’ abuses – described Iran and Guatemala as ‘two of the Agency's boldest, most spectacular covert operations’. It highlighted how CIA operations in the 1950s were ‘regarded as an essential contribution to the attainment of United States foreign policy objectives’.Footnote 73 Although tempered and qualified by a new narrative of process excess, the narrative of programmatic success remained dominant. Mindsets among critical audiences in the target countries included the malevolent omnipotence of the US and past experience of US – or other foreign – interference. This too supported perceptions of programmatic success.Footnote 74

The Italian election, the Iranian coup, and the Guatemalan coup all constituted salient events. They shaped observers’ interpretations and narratives of programmatic success. US policymakers and CIA operators wanted these outcomes and they ultimately happened, thus allowing observers to impose cause and effect without questioning whether the outcomes were actually independent from the action. Finally, social pressures included the dominance of elite US sources and accounts, from autobiographical narratives of potency in Iran to the myth of Guatemala. The perspective of practitioners, especially in a literature to which former practitioners – particularly US ones – have contributed more than in other subfields of international relations, is especially influential. Information asymmetry impacted interpretations of programmatic and process success.

In each of these ‘golden age’ cases, multiple audiences – including salient observers in target countries – adhere to the dominant narrative of programmatic success: meeting objectives, making gains, and having political impact. There is surprising convergence between sponsor and various audiences within target states, with both emphasising the effect of foreign interference, and, in that sense, success is a self-fulfilling construction. Both sides collude in narratives of success, often to suit their own purposes. The narrative of programmatic success reassures observers on both sides, thus providing them with a sense of ontological security. From this perspective, past covert action ‘successes’ help to construct mythologies that contribute to national security culture and identity.Footnote 75 Foreign policy actors can then use these ‘success’ stories ‘to develop and communicate strategic narratives about the past … and about their country's identity as an international actor in order to shape their discursive environment and the behaviour of other actors both domestically and internationally’.Footnote 76

For US observers, ‘success’ maintains a narrative of potency and leadership that aligns with the place of their country as a superpower. For the targets, and outside of the US national security setting, the same narrative creates a convenient imperialist scapegoat. It allowed the Italian left to explain successive election defeats and has ‘played a prominent role in left-wing attempts to construct identities of resistance and narratives of national independence’.Footnote 77 Similarly, many Iranians, from Muslim fundamentalists to secular nationalists, agree on the omnipotence of American influence to the exclusion of other narratives.Footnote 78

Narrative competition

Counter narratives challenge the notion of a ‘golden age’ and have largely crystallised away from myopic visions of programmatic ‘success’. Here, three clear points of contestation emerge, each shaped by mindsets, the salient events, and social pressures.

The first is whether longer-term consequences should be part of programmatic evaluation. Former practitioners have again tried to shape the narrative here, with Richard Bissell, for example, claiming that the CIA was not responsible for longer-term impact and that covert action, like military operations, was directed to achieve short-term objectives.Footnote 79 Bissell was promoting his own interests in claiming this, but the narrative struggled to gain much traction within academia with most scholars, benefiting from hindsight, taking longer-term consequences into account.

Such longer-term evaluation remains a matter of subjective judgement though. CIA officers involved in Iran, for example, insist that the stability brought about by the coup at the height of the Cold War was worth whatever longer-term effects might be ascribed to it.Footnote 80 Others are far more critical, arguing, for example, that the intervention sowed the roots of modern day terrorism.Footnote 81 This leads to counter-factual narratives that can never be proven, that is, that the 1979 revolution would not have happened without the earlier covert action, again highlighting the importance of perception.

Second, existing narratives diverge over process, in terms of legitimacy, and over political dimensions of success. This was particularly the case when the Church Committee and other government inquiries broadened the parameters of the debate in the 1970s. The committee portrayed even covert actions deemed programmatically successful as part of a broader pattern of procedural excess, which violated international norms and undermined the reputation of liberal democracy.Footnote 82 Such judgements, expressed by salient figures including journalists and politicians, became influential in the popular and historical discourse. In particular, Senator Church made the infamous remark that the CIA operated like a ‘rogue elephant on a rampage’.Footnote 83 This myth permeated much negative public understanding of covert action for a long time afterwards.

His remark took hold because Church, a voluble critic of the Agency, made it at a well-attended press conference, at a time when he was running for presidency and wanted to politicise proceedings. Demonstrating the importance of mindsets and experience, audiences were receptive because it represented frustrations of segments of the US population following anti-war protests and multiple scandals involving US intelligence encroachments on civil liberties at home. The Church committee eventually found that the CIA was not out of control, but the rogue elephant metaphor gained traction in the popular imagination and helped construct the image of a potent villain.Footnote 84 As noted above though, this image did not derail the broader programmatic success narrative. A majority of salient observers gave greater weight to programmatic over process and political dimensions of success.

The CIA clearly deemed the wider political narrative important in determining the success of the Guatemalan coup, so much so that it launched another covert action (PBHISTORY) to manipulate perceptions. This constitutes an explicit – if initially hidden – example of a social pressure attempting to manipulate narratives of success. Salient international actors, including the London Times, Le Monde, and the UN Secretary General criticised US involvement, hypocrisy and economic colonialism.Footnote 85 In response, the CIA sought to justify the regime change by disseminating documents supposedly proving that the Soviets controlled Guatemalan communists, thereby countering the Soviet (and non-aligned) narrative that Guatemala had posed little threat to Washington. This CIA effort did not gain much traction in the international discourse, but it demonstrated the role of social pressure and potential for manipulation in the contest for narrative dominance.Footnote 86 Although there is divergence about longer-term consequences, issues of legitimacy and authorisation, and political ramifications, these narratives all take place within the same settings and use the same characters: US national security and CIA potency.

The third contest is ‘success’ for whom. Changing the setting away from US national security and the Cold War allows marginalised counter-narratives to emerge.Footnote 87 It challenges interpretations of the three dimensions of success at the core of our model. Alternative settings of economics, imperialism, development, or human security enable different narratives beyond whether and how the US achieved its goals; so too does a change in the cast of characters towards internal actors. Counter-narratives here offer different perspectives on the Iranian coup. The coup arguably set back the process of oil nationalisation globally for around two decades; destroyed secular opposition; delegitimised the monarchy; and ‘further intensified the already intense paranoid style prevalent throughout Iranian politics’. It left a ‘deep imprint on the country’, including its collective memory, ‘popular culture and what some would call mentality’.Footnote 88 Citizens of all ideologies became more convinced than ever that ‘figures visible on the national stage were mere “marionettes” controlled by “foreign strings”’.Footnote 89 More broadly, others have commented that covert action – and rumors of covert action – have contributed to a ‘paranoid style’ amid the domestic politics of the Middle East, South Asia, and Central America, with damaging consequences for development.Footnote 90

In sum, these ‘golden age’ covert actions are programmatic successes, and partial process successes, because salient actors – both sponsor and targets – subscribe to that narrative. This unearths surprising convergence in recognising the power of the CIA, not because of objective evidence and an ability to isolate impact but because collusion in this narrative benefits both sides. Narratives of CIA success – shaped by mindsets, events, and social pressures – can provide a reassuring sense of continuity to policy elites.Footnote 91 From the sponsor's perspective, using covert action provides reassurance that the United States is a ‘great power’ that is actively shaping the world.Footnote 92 In the target state, a ‘CIA success’ provides a useful scapegoat to justify new – and sometimes extraordinary – policies aimed to restore a sense of physical and ontological security.Footnote 93 Narratives are a form of political resource that assign meanings to events and create perceptions of reality that can mobilise groups and foster solidarity.

These narratives of success only diverge when considering the longer-term, legitimacy, political, or non-US implications. Success for whom? Was it worth it? Despite some divergences the dominant narrative continues to follow a US state perspective and points to short-term success but longer-term failures. However, it is important to recognise variation in interpretations: mindsets, salient events, and social pressures vary from one observer and context to another.

Conclusions and implications

As US competition with China increases, some scholars fear covert action is back on the agenda and are warning policymakers against it.Footnote 94 However, such policy advice rests on shaky epistemological foundations; the often-cited figure that covert regime change only works 39 per cent of the time conveys a misplaced sense of certainty through its apparent precision.Footnote 95 Asking how covert actions came to be seen as a success, failure, or something in between is an equally, if not more, important question than whether covert action works. How we conceptualise or construct success in the first place has real world implications that can lead to the use and misuse of policy instruments, missed opportunities, and counterproductive reactions to adversaries’ operations.

This article has deconstructed covert action success in order to expose and distill competing criteria. It has argued that success is not absolute, but laden with subjective judgements. Measuring the outcomes of covert action against policy goals and asserting success in a completely objective manner is impossible. Instead, success is constructed through discourse and spans contested criteria beyond programmatic outcomes to include how covert action was planned and executed as well as interpretations of the broader political consequences. Understanding success requires analysis of narratives of all three dimensions – and these narratives are shaped by myriad factors.

Our attempt to conceptualise the evaluation of covert action success has four significant implications. First, our wider-ranging dialogue between different dimensions and perceptions of success teases out trade-offs. Crucial when debating use of covert action, these include the impact of operations on institutional process and democratic norms, and the impact on broader political reputations. For example, successfully interfering in an election can be outweighed by the cost of a sponsored candidate being tainted as a perceived puppet if exposed. Likewise, programmatic success might be outweighed by broader political and reputational hits, as the CIA worried about in the aftermath of Guatemala. Political-programmatic trade-offs are especially important for covert action. Similarly, conceptual clarity teases out the (often conflated) relationship between outputs and outcomes. For example, literature on Italy often focuses on the number of propaganda outputs rather than the impact they had. Paradoxically, desire for metrics can actually hinder operations by pushing towards easy wins, which agencies can claim as successes, but which come at the cost of longer-term confusion.

Second, tracing how a covert action came to be seen as a success or failure exposes the construction of outcomes through political interactions. It also underlines the importance of perceptions and narratives in international affairs. Covert actions, such as US interference in the 1948 Italian election, are successful if salient audiences perceive them as such. This has implications for how states use and respond to covert actions. Reactions to hostile covert actions, especially when overplaying ‘success’, can generate paranoia, hysteria and conspiracism. Much like in Iran regarding the CIA, so in the United States after 2016 the Russian hand appeared everywhere and parts of the American public lost faith in the state's own liberal democratic institutions and ‘custodians of factual authority’.Footnote 96

Third, tracing how covert actions came to be seen as a success helps to challenge the dominance of the Anglosphere and state-centrism in intelligence studies. Recognising that evaluations are ‘dependent on temporal, spatial, cultural and political factors’Footnote 97 enables a more wide-ranging dialogue, more nuanced evaluations, and a more explicit recognition of power relations and competing perspectives. Success for whom becomes more important. This approach has the potential to decentre the state in analysis of covert actions, opening space to consider the effects on target populations, as well as domestic public opinion. This opens new avenues of research that should, importantly, give a greater voice to scholars and scholarship from and on the Global South.Footnote 98 Likewise, reducing the focus on sponsoring states gives more voice to domestic agency and bottom-up forces or protests. It is important to look beyond hidden hands – Western or otherwise – when explaining unrest and division. Intelligence scholars have focused too much on ‘hidden hands’ and not enough on the ‘hearts and minds’ these hands seek to manipulate.

Akanksha Mehta and Annick T. R. Wibben, for example, suggest exploring personal narratives and acknowledging differences among stories and storytellers to unpack the relationship between security and identity. Such an approach can shed light on the impact of covert action on marginalised voices, such as local populations for whom covert action is not synonymous with foreign policy success but forms of gendered and racialised insecurity.Footnote 99

Fourth, and leading on from this, the subjective nature of covert action successes opens further avenues of research to link the study of covert action to broader debates in International Relations. Our model identifies a path to develop revisionist studies that highlight the socially constructed nature of covert action to question dominant interpretations of the broader set of cases developed by pioneering historians. This approach has much potential to build bridges with International Relations research on identity and narratives, which largely overlooks the role of intelligence agencies in informing foreign policy construction. Dina Rezk, for example, shows how Western intelligence analysis developed biased views of the ‘Arab Other’ during the Cold War.Footnote 100 Priya Chacko recognises constructions of external CIA involvement in her study of Indian foreign policy.Footnote 101 However, much of the existing literature overlooks the role of intelligence agencies in constructing ‘others’.Footnote 102

It also bridges with feminist approaches to security studies. In addition to the work of Mehta and Wibben cited above, Elspeth Van Veeren argues that discourse surrounding the Global War on Terror has reinforced gender, racial, and sexual hierarchies within and beyond special operator communities. This links to broader discussions of how discourse produces and reproduces the self (that is, insiders and ‘good guys') and the foreign other. The secrecy of covert actions can create a framing effect that reinforces structural inequalities; this is something that has been largely overlooked in intelligence studies, but not in the broader study of International Relations.Footnote 103

Our findings may also provide new data and case studies for those examining how states cultivate ontological security. The routinised practice of covert action provides a stable cognitive environment to the state and its elite and helps to guarantee their ontological security.Footnote 104 Covert actions themselves, as well as their outcomes, derive meaning through discourse. Highly mythologised, told through narratives, and shaping national security cultures, they offer fresh insight into how states see and present themselves on the international stage.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article: Oliver Daddow, Jamie Gaskarth, Magda Long, Michael Poznansky, Bettina Renz, Mark Stout and colleagues at Johns Hopkins, and historians at the US Pentagon where Rory Cormac presented a very early version in 2018. Cormac is also grateful to the Leverhulme Trust for funding an international fellowship from which this article emerged. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers and editors for their comments.