1 Introduction

Arrow’s 1950 impossibility theorem [Reference Arrow3, Reference Arrow4] is a foundational result in social choice theory. If a society contains only finitely many voters, then any aggregation of individual preference orderings (called a social welfare function) respecting Arrow’s conditions of unanimity and independence of irrelevant alternatives is dictated by a single voter. The theorem therefore appears to place substantial limits on the existence of methods for social decision-making that are fair, rational, and uniform. It has a wide range of applicability including the problems of selecting candidates in elections, deciding on public policies, and choosing between rival scientific theories. As such it has exerted a substantial influence on economics [Reference Hammond19, Reference Sen45], political science [Reference Riker41], and philosophy [Reference Hurley25, Reference Okasha37].

Although Arrow’s theorem is essentially a result in finitary combinatorics, later developments in social choice theory in the 1970s brought in more powerful methods such as non-principal ultrafilters, which Fishburn [Reference Fishburn14] used to show that infinite societies have non-dictatorial social welfare functions. This result and others like it have led mathematical economists to grapple with non-constructivity and applications of the axiom of choice [Reference Litak, Palmigiano and Pivato33]. However, for economically and philosophically relevant models such as societies which are countable or continuous, reverse mathematics offers a more appropriate framework for gauging where (and what) non-constructive set existence axioms are actually necessary in social choice theory.

This paper initiates the reverse mathematics of social choice theory, studying Arrow’s impossibility theorem and related results including Fishburn’s possibility theorem within the framework of reverse mathematics. By defining fundamental notions of social choice theory in second-order arithmetic, we show that an influential analysis of social welfare functions in terms of ultrafilters by Kirman and Sondermann [Reference Kirman and Sondermann29] can be carried out in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. This allows us to establish that Arrow’s theorem, when formalised as a statement of first-order arithmetic, is provable in primitive recursive arithmetic. Fishburn’s possibility theorem, on the other hand, uses non-constructive resources in an essential way, and we prove that its restriction to countable societies is equivalent to

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. This allows us to establish that Arrow’s theorem, when formalised as a statement of first-order arithmetic, is provable in primitive recursive arithmetic. Fishburn’s possibility theorem, on the other hand, uses non-constructive resources in an essential way, and we prove that its restriction to countable societies is equivalent to

![]() ${\mathsf {ACA}}_0$

.

${\mathsf {ACA}}_0$

.

In the classical Arrovian framework, a society

![]() $\mathcal {S}$

consists of a set V of voters, a set X of alternatives (or candidates), together with the set W of all weak orders of X (representing the different ways in which the set of alternatives can be rationally ordered), a set

$\mathcal {S}$

consists of a set V of voters, a set X of alternatives (or candidates), together with the set W of all weak orders of X (representing the different ways in which the set of alternatives can be rationally ordered), a set

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

of coalitions of voters, and a set

$\mathcal {A}$

of coalitions of voters, and a set

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

of profiles, i.e., functions

$\mathcal {F}$

of profiles, i.e., functions

![]() ${f : V \to W}$

representing different elections or voting scenarios. In Arrow’s framework,

${f : V \to W}$

representing different elections or voting scenarios. In Arrow’s framework,

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

and

$\mathcal {A}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

satisfy a condition known as unrestricted domain (or universal domain), meaning that

$\mathcal {F}$

satisfy a condition known as unrestricted domain (or universal domain), meaning that

![]() $\mathcal {A} = {\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

and

$\mathcal {A} = {\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {F} = W^V$

, the set of all functions

$\mathcal {F} = W^V$

, the set of all functions

![]() $f : V \to W$

.

$f : V \to W$

.

Given alternatives

![]() $x,y \in X$

, a profile

$x,y \in X$

, a profile

![]() $f : V \to W$

, and a voter

$f : V \to W$

, and a voter

![]() $v \in V$

, we write

$v \in V$

, we write

to mean that voter v ranks x at least as highly y under profile f, and

to mean that voter v strictly prefers x to y under profile f. A social welfare function

![]() $\sigma $

for a society

$\sigma $

for a society

![]() $\mathcal {S}$

maps profiles in

$\mathcal {S}$

maps profiles in

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

to weak orders in W, and represents one way of consistently aggregating individual preference orderings into an overall social preference ordering. We write

$\mathcal {F}$

to weak orders in W, and represents one way of consistently aggregating individual preference orderings into an overall social preference ordering. We write

to mean that the social welfare function

![]() $\sigma $

ranks x at least as highly as y under profile f, and similarly for

$\sigma $

ranks x at least as highly as y under profile f, and similarly for

![]() $x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

. If R is a weak ordering and

$x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

. If R is a weak ordering and

![]() $Y \subseteq X$

, we write

$Y \subseteq X$

, we write

![]() $R\mathpunct {\restriction _{Y}}$

to mean

$R\mathpunct {\restriction _{Y}}$

to mean

![]() $R \cap Y^2$

. This lets us state Arrow’s conditions more precisely.

$R \cap Y^2$

. This lets us state Arrow’s conditions more precisely.

-

(1) Unanimity: If

$x <_{f(v)} y$

for all

$x <_{f(v)} y$

for all

$v \in V$

, then

$v \in V$

, then

$x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

.

$x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

. -

(2) Independence of irrelevant alternatives: If

$f(v)\mathpunct {\restriction _{\{x,y\}}} = g(v)\mathpunct {\restriction _{\{x,y\}}}$

for all

$f(v)\mathpunct {\restriction _{\{x,y\}}} = g(v)\mathpunct {\restriction _{\{x,y\}}}$

for all

$v \in V$

then

$v \in V$

then

$\sigma (f)\mathpunct {\restriction _{\{x,y\}}} = \sigma (g)\mathpunct {\restriction _{\{x,y\}}}$

.

$\sigma (f)\mathpunct {\restriction _{\{x,y\}}} = \sigma (g)\mathpunct {\restriction _{\{x,y\}}}$

. -

(3) Non-dictatoriality: There is no

$d \in V$

such that for all

$d \in V$

such that for all

$f \in \mathcal {F}$

, if

$f \in \mathcal {F}$

, if

$x <_{f(d)} y$

then

$x <_{f(d)} y$

then

$x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

.

$x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

.

Theorem 1.1 (Arrow’s impossibility theorem).

Suppose

![]() $\mathcal {S} = \mathopen {\langle }V,X,\mathcal {A},\mathcal {F}\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a society satisfying unrestricted domain such that V is a nonempty and finite set of voters, and X is a finite set of alternatives with

$\mathcal {S} = \mathopen {\langle }V,X,\mathcal {A},\mathcal {F}\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a society satisfying unrestricted domain such that V is a nonempty and finite set of voters, and X is a finite set of alternatives with

![]() $\left \lvert {X}\right \rvert \geq 3$

. Then there exists no social welfare function

$\left \lvert {X}\right \rvert \geq 3$

. Then there exists no social welfare function

![]() $\sigma : \mathcal {F} \to W$

satisfying unanimity, independence, and non-dictatoriality.

$\sigma : \mathcal {F} \to W$

satisfying unanimity, independence, and non-dictatoriality.

Fishburn [Reference Fishburn14] offered a way out of Arrow’s impossibility result, showing that Arrow’s conditions are consistent if we drop the requirement that V is finite.Footnote 1

Theorem 1.2 (Fishburn’s possibility theorem).

Suppose

![]() $\mathcal {S} = \mathopen {\langle }V,X,\mathcal {A},\mathcal {F}\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a society satisfying unrestricted domain such that V is an infinite set of voters, and X is a finite set of alternatives with

$\mathcal {S} = \mathopen {\langle }V,X,\mathcal {A},\mathcal {F}\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a society satisfying unrestricted domain such that V is an infinite set of voters, and X is a finite set of alternatives with

![]() $\left \lvert {X}\right \rvert \geq 3$

. Then there exists a social welfare function

$\left \lvert {X}\right \rvert \geq 3$

. Then there exists a social welfare function

![]() $\sigma : \mathcal {F} \to W$

satisfying unanimity, independence, and non-dictatoriality.

$\sigma : \mathcal {F} \to W$

satisfying unanimity, independence, and non-dictatoriality.

Infinite societies are widely used in mathematical economics [Reference Aumann5, Reference Hammond20–Reference Hildenbrand22].Footnote 2 Fishburn’s theorem is therefore of antecedent interest in its application domain, despite the prima facie implausibility of infinite ‘societies’.

On a mathematical level, Fishburn’s possibility theorem is best understood in the context of an influential analysis by Kirman and Sondermann [Reference Kirman and Sondermann29] which shows that social welfare functions satisfying unanimity and independence correspond to ultrafilters. Arrow had already introduced the notion of a

![]() $\sigma $

-decisive coalition for a social welfare function

$\sigma $

-decisive coalition for a social welfare function

![]() $\sigma $

: a set

$\sigma $

: a set

![]() $C \subseteq V$

such that if

$C \subseteq V$

such that if

![]() $x <_{f(v)} y$

for every

$x <_{f(v)} y$

for every

![]() $v \in C$

, then

$v \in C$

, then

![]() $x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

. Kirman and Sondermann established that the collection of all

$x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

. Kirman and Sondermann established that the collection of all

![]() $\sigma $

-decisive coalitions forms an ultrafilter which is principal if and only if

$\sigma $

-decisive coalitions forms an ultrafilter which is principal if and only if

![]() $\sigma $

is dictatorial.

$\sigma $

is dictatorial.

Theorem 1.3 (Kirman–Sondermann theorem).

Suppose

![]() $\mathcal {S} = \mathopen {\langle }V,X,\mathcal {A},\mathcal {F}\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a society satisfying unrestricted domain such that V is a nonempty set of voters, and X is a finite set of alternatives with

$\mathcal {S} = \mathopen {\langle }V,X,\mathcal {A},\mathcal {F}\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a society satisfying unrestricted domain such that V is a nonempty set of voters, and X is a finite set of alternatives with

![]() $\left \lvert {X}\right \rvert \geq 3$

. For any social welfare function

$\left \lvert {X}\right \rvert \geq 3$

. For any social welfare function

![]() $\sigma : \mathcal {F} \to W$

satisfying unanimity and independence, the set

$\sigma : \mathcal {F} \to W$

satisfying unanimity and independence, the set

forms an ultrafilter on

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

which is principal if and only if

$\mathcal {A}$

which is principal if and only if

![]() $\sigma $

is dictatorial.

$\sigma $

is dictatorial.

Arrow’s theorem is an immediate consequence of the Kirman–Sondermann theorem: as every ultrafilter on a finite set is principal and hence generated by a singleton

![]() $\{ d \}$

, any social welfare function for a society with a finite set V of voters must be dictatorial. The Kirman–Sondermann theorem also provides us with our first reverse mathematics-style result. Since it is provable in

$\{ d \}$

, any social welfare function for a society with a finite set V of voters must be dictatorial. The Kirman–Sondermann theorem also provides us with our first reverse mathematics-style result. Since it is provable in

![]() $\mathrm {ZF}$

, any non-dictatorial social welfare function

$\mathrm {ZF}$

, any non-dictatorial social welfare function

![]() $\sigma $

for a society with an infinite set V of voters will give rise to a non-principal ultrafilter

$\sigma $

for a society with an infinite set V of voters will give rise to a non-principal ultrafilter

![]() $\mathcal {U}_\sigma $

on

$\mathcal {U}_\sigma $

on

![]() ${\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

.

${\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

.

Theorem 1.4. Fishburn’s possibility theorem is equivalent over

![]() $\mathrm {ZF}$

to the statement that for every infinite set V there exists a non-principal ultrafilter on

$\mathrm {ZF}$

to the statement that for every infinite set V there exists a non-principal ultrafilter on

![]() ${\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

.

${\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

.

The existence of non-principal ultrafilters is unprovable in

![]() $\mathrm {ZF}$

[Reference Blass6], but is (strictly) implied by the axiom of choice [Reference Jech26, Reference Pincus and Solovay40]. Many therefore consider Fishburn’s possibility theorem to be highly non-constructive [Reference Brunner and Reiju Mihara8–Reference Cato10, Reference Mihara36]. At least prima facie, this is a substantial problem for any genuine application of Fishburn’s possibility theorem in social choice theory, a field which is supposed to apply to everyday social decision-making processes such as national elections or votes in a hiring committee.Footnote

3

This kind of concern with applicability lies behind a wide range of studies of Arrow’s theorem using tools from computability theory and computational complexity theory. Amongst the former are the work of Lewis [Reference Lewis32] in the 1980s and Mihara [Reference Mihara35, Reference Mihara36] in the 1990s, while the latter is the preserve of the flourishing field of computational social choice theory [Reference Brandt, Conitzer, Endriss, Lang and Procaccia7, Reference Chevaleyre, Endriss, Lang and Maudet11].

$\mathrm {ZF}$

[Reference Blass6], but is (strictly) implied by the axiom of choice [Reference Jech26, Reference Pincus and Solovay40]. Many therefore consider Fishburn’s possibility theorem to be highly non-constructive [Reference Brunner and Reiju Mihara8–Reference Cato10, Reference Mihara36]. At least prima facie, this is a substantial problem for any genuine application of Fishburn’s possibility theorem in social choice theory, a field which is supposed to apply to everyday social decision-making processes such as national elections or votes in a hiring committee.Footnote

3

This kind of concern with applicability lies behind a wide range of studies of Arrow’s theorem using tools from computability theory and computational complexity theory. Amongst the former are the work of Lewis [Reference Lewis32] in the 1980s and Mihara [Reference Mihara35, Reference Mihara36] in the 1990s, while the latter is the preserve of the flourishing field of computational social choice theory [Reference Brandt, Conitzer, Endriss, Lang and Procaccia7, Reference Chevaleyre, Endriss, Lang and Maudet11].

Lewis [Reference Lewis32] worked principally with a notion of “recursively enumerable society” in which

![]() $V = \omega $

, the algebra of coalitions

$V = \omega $

, the algebra of coalitions

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is restricted to include only computably enumerable sets, and the set

$\mathcal {A}$

is restricted to include only computably enumerable sets, and the set

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

of profiles is restricted to include only computable functions. The set X of alternatives must be have at least three elements, and be at most countably infinite. Lewis proved a weak version of Arrow’s theorem for such societies, showing that if

$\mathcal {F}$

of profiles is restricted to include only computable functions. The set X of alternatives must be have at least three elements, and be at most countably infinite. Lewis proved a weak version of Arrow’s theorem for such societies, showing that if

![]() $\sigma $

is a computable social welfare function for a recursively enumerable society

$\sigma $

is a computable social welfare function for a recursively enumerable society

![]() $\mathcal {S}$

, then for each profile

$\mathcal {S}$

, then for each profile

![]() $f \in \mathcal {F}$

there exists a ‘dictator’ d such that for all

$f \in \mathcal {F}$

there exists a ‘dictator’ d such that for all

![]() $x,y \in X$

, if

$x,y \in X$

, if

![]() $x <_{f(d)} y$

, then

$x <_{f(d)} y$

, then

![]() $x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

. This ‘dictator’ is not necessarily unique across all profiles, and hence not a dictator in Arrow’s original sense.Footnote

4

$x <_{\sigma (f)} y$

. This ‘dictator’ is not necessarily unique across all profiles, and hence not a dictator in Arrow’s original sense.Footnote

4

Mihara’s approach in [Reference Mihara35] is somewhat different, working with a single society

![]() $\mathcal {S}$

in which

$\mathcal {S}$

in which

![]() $V = \omega $

, and the coalition algebra

$V = \omega $

, and the coalition algebra

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is precisely the set

$\mathcal {A}$

is precisely the set

![]() $\mathrm {REC}$

of all computable sets. Mihara allows a broader range of profiles in

$\mathrm {REC}$

of all computable sets. Mihara allows a broader range of profiles in

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

, namely those which are measurable by sets in

$\mathcal {F}$

, namely those which are measurable by sets in

![]() $\mathrm {REC}$

.Footnote

5

The set of alternatives X can be any set with at least three elements, although the computability requirements mean that only countably many alternatives will actually end up being considered by any given social welfare function. Unlike Lewis, Mihara defines a dictator as Arrow does: a single individual whose preferences determine the social ordering across all profiles. Mihara proves that any computable non-dictatorial social welfare function for the society based on the coalition algebra

$\mathrm {REC}$

.Footnote

5

The set of alternatives X can be any set with at least three elements, although the computability requirements mean that only countably many alternatives will actually end up being considered by any given social welfare function. Unlike Lewis, Mihara defines a dictator as Arrow does: a single individual whose preferences determine the social ordering across all profiles. Mihara proves that any computable non-dictatorial social welfare function for the society based on the coalition algebra

![]() $\mathrm {REC}$

must compute

$\mathrm {REC}$

must compute

![]() ${0}'$

. The recursive counterexample which we give to Fishburn’s possibility theorem at the end of Section 5 improves on Mihara’s result by constructing a countable society which does not contain all computable sets as coalitions, and can be coded as a single computable set, but all of whose non-dictatorial social welfare functions compute

${0}'$

. The recursive counterexample which we give to Fishburn’s possibility theorem at the end of Section 5 improves on Mihara’s result by constructing a countable society which does not contain all computable sets as coalitions, and can be coded as a single computable set, but all of whose non-dictatorial social welfare functions compute

![]() ${0}'$

. In [Reference Mihara36], Mihara shows that there exist non-dictatorial social welfare functions for this society which are computable relative to

${0}'$

. In [Reference Mihara36], Mihara shows that there exist non-dictatorial social welfare functions for this society which are computable relative to

![]() ${0}"$

.Footnote

6

${0}"$

.Footnote

6

The aim of this paper is to provide a more nuanced analysis of the situation regarding Arrow’s theorem, Fishburn’s theorem, and their relative (non-)constructivity in terms of the hierarchy of subsystems of second-order arithmetic studied in reverse mathematics. After briefly introducing the relevant background from reverse mathematics and social choice theory in Section 2, we present a canonical sequence of definitions in Section 3 for investigating the proof-theoretic strength of theorems in social choice theory. This investigation begins with Arrow’s impossibility theorem and Fishburn’s possibility theorem, but the framework is sufficiently general and flexible to accommodate future research on other landmark results in social choice theory such as the Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem [Reference Gibbard17, Reference Satterthwaite43].

The central definition is that of a countable society: a structure

![]() $\mathcal {S} = \mathopen {\langle }V,X,\mathcal {A},\mathcal {F}\mathclose {\rangle }$

in which

$\mathcal {S} = \mathopen {\langle }V,X,\mathcal {A},\mathcal {F}\mathclose {\rangle }$

in which

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

, and the algebra of coalitions

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

, and the algebra of coalitions

![]() $\mathcal {A} \subseteq {\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

and the set of profiles

$\mathcal {A} \subseteq {\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

and the set of profiles

![]() $\mathcal {F} \subseteq W^V$

are both countable. Key to this definition and to the results in the paper are conditions on

$\mathcal {F} \subseteq W^V$

are both countable. Key to this definition and to the results in the paper are conditions on

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

and

$\mathcal {A}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

called uniform measurability and quasi-partition embedding that ensure their richness and relative compatibility, and which are substantially weaker than previously proposed alternatives to Arrow’s unrestricted domain condition. Using this framework we prove the following results.

$\mathcal {F}$

called uniform measurability and quasi-partition embedding that ensure their richness and relative compatibility, and which are substantially weaker than previously proposed alternatives to Arrow’s unrestricted domain condition. Using this framework we prove the following results.

Theorem 1.5. Arrow’s impossibility theorem is provable in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

.

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

.

In Section 4 we establish that the Kirman–Sondermann analysis of social welfare functions for countable (and hence finite) societies in terms of ultrafilters of decisive coalitions can be formalised in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. It follows that Arrow’s impossibility theorem is also provable in

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. It follows that Arrow’s impossibility theorem is also provable in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. Moreover, by replacing finite sets with their codes, Arrow’s theorem can be formalised as a

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. Moreover, by replacing finite sets with their codes, Arrow’s theorem can be formalised as a

![]() $\Pi ^0_1$

sentence which is provable in

$\Pi ^0_1$

sentence which is provable in

![]() $\mathrm {PRA}$

.

$\mathrm {PRA}$

.

Theorem 1.6. Fishburn’s possibility theorem for countable societies is equivalent over

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

to the axiom scheme of arithmetical comprehension.

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

to the axiom scheme of arithmetical comprehension.

This shows that Fishburn’s possibility theorem requires the same set existence principles for its proof as theorems of classical analysis like the Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem, and combinatorial principles like König’s infinity lemma or Ramsey’s theorem

![]() $\mathrm {RT}^n_k$

for

$\mathrm {RT}^n_k$

for

![]() $n \geq 2$

and

$n \geq 2$

and

![]() $k \geq 3$

. Section 5 is devoted to proving this equivalence, which can be seen as an analogue in second-order arithmetic of theorem 1.4 above. This result can also be understood as generalising the results of Lewis and Mihara discussed above to the broader class of countable societies introduced in Section 3.

$k \geq 3$

. Section 5 is devoted to proving this equivalence, which can be seen as an analogue in second-order arithmetic of theorem 1.4 above. This result can also be understood as generalising the results of Lewis and Mihara discussed above to the broader class of countable societies introduced in Section 3.

2 Preliminaries

This section provides a brief overview of subsystems of second-order arithmetic (Section 2.1), ultrafilters on countable algebras of sets (Section 2.2), and weak orders in social choice theory (Section 2.3).

2.1 Subsystems of second-order arithmetic

Reverse mathematics is a subfield of mathematical logic devoted to determining the set existence principles necessary to prove theorems of ordinary mathematics, including real and complex analysis, countable algebra, and countable infinitary combinatorics. This is done by formalising the theorems concerned in the language of second-order arithmetic, and proving equivalences between those formalisations and systems located in a well-understood hierarchy of set existence principles. The equivalence proofs are carried out in a weak base theory known as

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

, which roughly corresponds to computable mathematics and is briefly described below. For details of the material in this subsection, we refer readers to Simpson’s reference work Subsystems of Second Order Arithmetic [Reference Simpson48], Dzhafarov and Mummert’s textbook Reverse Mathematics [Reference Dzhafarov and Mummert12], and Hirschfeldt’s monograph Slicing the Truth [Reference Hirschfeldt23].

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

, which roughly corresponds to computable mathematics and is briefly described below. For details of the material in this subsection, we refer readers to Simpson’s reference work Subsystems of Second Order Arithmetic [Reference Simpson48], Dzhafarov and Mummert’s textbook Reverse Mathematics [Reference Dzhafarov and Mummert12], and Hirschfeldt’s monograph Slicing the Truth [Reference Hirschfeldt23].

Second-order arithmetic

![]() $\mathcal {L}_2$

is a two-sorted formal language, with number variables

$\mathcal {L}_2$

is a two-sorted formal language, with number variables

![]() $x_1,x_2,\dotsc $

whose intended range is the natural numbers

$x_1,x_2,\dotsc $

whose intended range is the natural numbers

![]() $\mathbb {N}$

, and set variables

$\mathbb {N}$

, and set variables

![]() $X_1,X_2,\dotsc $

whose intended range is the powerset of the natural numbers

$X_1,X_2,\dotsc $

whose intended range is the powerset of the natural numbers

![]() ${\mathcal {P}{{(\mathbb {N})}}}$

. The non-logical symbols are those of Peano arithmetic (

${\mathcal {P}{{(\mathbb {N})}}}$

. The non-logical symbols are those of Peano arithmetic (

![]() $0,1,+,\times ,<$

) plus the

$0,1,+,\times ,<$

) plus the

![]() $\in $

symbol for set membership. The atomic formulas of

$\in $

symbol for set membership. The atomic formulas of

![]() $\mathcal {L}_2$

are those of the form

$\mathcal {L}_2$

are those of the form

![]() $t_1 = t_2$

,

$t_1 = t_2$

,

![]() $t_1 < t_2$

, and

$t_1 < t_2$

, and

![]() $t_1 \in X_1$

, where

$t_1 \in X_1$

, where

![]() $t_1,t_2$

are number terms and

$t_1,t_2$

are number terms and

![]() $X_1$

is a set variable. As well as the usual logical connectives, it contains both number quantifiers (sometimes called first-order quantifiers)

$X_1$

is a set variable. As well as the usual logical connectives, it contains both number quantifiers (sometimes called first-order quantifiers)

![]() $\forall {x}$

and

$\forall {x}$

and

![]() $\exists {x}$

, and set quantifiers (sometimes called second-order quantifiers)

$\exists {x}$

, and set quantifiers (sometimes called second-order quantifiers)

![]() $\forall {X}$

and

$\forall {X}$

and

![]() $\exists {X}$

. Formulas of

$\exists {X}$

. Formulas of

![]() $\mathcal {L}_2$

are built up from atomic formulas using logical connectives and set and number quantifiers.

$\mathcal {L}_2$

are built up from atomic formulas using logical connectives and set and number quantifiers.

The base theory

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

has three sets of axioms: the basic arithmetical axioms, the

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

has three sets of axioms: the basic arithmetical axioms, the

![]() $\Sigma ^0_1$

induction scheme, and the recursive comprehension axiom scheme. The basic arithmetical axioms are those of Peano arithmetic, minus the induction scheme: in other words, the axioms of a commutative discrete ordered semiring. The

$\Sigma ^0_1$

induction scheme, and the recursive comprehension axiom scheme. The basic arithmetical axioms are those of Peano arithmetic, minus the induction scheme: in other words, the axioms of a commutative discrete ordered semiring. The

![]() $\Sigma ^0_1$

induction axiom scheme consists of the universal closures of all formulas of the form

$\Sigma ^0_1$

induction axiom scheme consists of the universal closures of all formulas of the form

where

![]() $\varphi $

is a

$\varphi $

is a

![]() $\Sigma ^0_1$

formula, i.e., one of the form

$\Sigma ^0_1$

formula, i.e., one of the form

![]() $\exists {k}\theta (n,k)$

where

$\exists {k}\theta (n,k)$

where

![]() $\theta $

contains only bounded quantifiers. Finally, the recursive or

$\theta $

contains only bounded quantifiers. Finally, the recursive or

![]() $\Delta ^0_1$

comprehension axiom scheme consists of the universal closures of all formulas of the form

$\Delta ^0_1$

comprehension axiom scheme consists of the universal closures of all formulas of the form

where

![]() $\varphi $

is a

$\varphi $

is a

![]() $\Sigma ^0_1$

formula and

$\Sigma ^0_1$

formula and

![]() $\psi $

is a

$\psi $

is a

![]() $\Pi ^0_1$

formula, i.e., one of the form

$\Pi ^0_1$

formula, i.e., one of the form

![]() $\forall {k}\theta (n,k)$

where

$\forall {k}\theta (n,k)$

where

![]() $\theta $

contains only bounded quantifiers.

$\theta $

contains only bounded quantifiers.

Other subsystems of second-order arithmetic are obtained by extending

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

with additional axioms. The present paper is concerned only with one of these systems,

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

with additional axioms. The present paper is concerned only with one of these systems,

![]() ${\mathsf {ACA}}_0$

, which is obtained by augmenting the axioms of

${\mathsf {ACA}}_0$

, which is obtained by augmenting the axioms of

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

with the arithmetical comprehension scheme, which consists of the universal closures of all formulas of the form

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

with the arithmetical comprehension scheme, which consists of the universal closures of all formulas of the form

where

![]() $\varphi $

is an arithmetical formula, i.e., which may contain number quantifiers but no set quantifiers, although it may contain free set variables.

$\varphi $

is an arithmetical formula, i.e., which may contain number quantifiers but no set quantifiers, although it may contain free set variables.

2.2 Countable algebras and ultrafilters

Our approach to ultrafilters on countable algebras of sets is based on that of Hirst [Reference Hirst24]. We use the standard coding of a sequence of sets by a single sets using the primitive recursive pairing map

![]() $(m,n) = (m + n)^2 + m$

.

$(m,n) = (m + n)^2 + m$

.

![]() $Y \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is a sequence of sets,

$Y \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is a sequence of sets,

![]() $Y = \mathopen {\langle }Y_i : i \in \mathbb {N}\mathclose {\rangle }$

, if

$Y = \mathopen {\langle }Y_i : i \in \mathbb {N}\mathclose {\rangle }$

, if

for all

![]() $i,v \in \mathbb {N}$

.

$i,v \in \mathbb {N}$

.

Definition 2.1 (Countable algebras of sets).

Let

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and let

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and let

![]() $\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle }A_n : n \in \mathbb {N}\mathclose {\rangle }$

be a countable sequence of sets such that for every

$\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle }A_n : n \in \mathbb {N}\mathclose {\rangle }$

be a countable sequence of sets such that for every

![]() $i \in \mathbb {N}$

,

$i \in \mathbb {N}$

,

![]() $A_i \subseteq V$

.

$A_i \subseteq V$

.

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is a countable algebra over V if it contains V and it is closed under unions, intersections, and complements relative to V. A countable algebra

$\mathcal {A}$

is a countable algebra over V if it contains V and it is closed under unions, intersections, and complements relative to V. A countable algebra

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

over V is atomic if for all

$\mathcal {A}$

over V is atomic if for all

![]() $v \in V$

, there exists

$v \in V$

, there exists

![]() $k \in \mathbb {N}$

such that

$k \in \mathbb {N}$

such that

![]() $A_k = \{ v \}$

.

$A_k = \{ v \}$

.

If

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is a countable algebra over a set V, we write

$\mathcal {A}$

is a countable algebra over a set V, we write

![]() $A_i^c$

to denote its relative complement

$A_i^c$

to denote its relative complement

![]() $V \setminus A_i$

. Repetitions are allowed, so given a countable algebra

$V \setminus A_i$

. Repetitions are allowed, so given a countable algebra

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

we can computably construct an algebra

$\mathcal {A}$

we can computably construct an algebra

![]() $\mathcal {A}'$

which contains the same sets (typically in a different order) in which we can uniformly compute the operations of complementation, union, and intersection. We make this precise through the following definition.

$\mathcal {A}'$

which contains the same sets (typically in a different order) in which we can uniformly compute the operations of complementation, union, and intersection. We make this precise through the following definition.

Definition 2.2 (Boolean embeddings).

A boolean formation sequence is a finite sequence

![]() $s \in \mathrm {Seq}$

with

$s \in \mathrm {Seq}$

with

![]() $\left \lvert {s}\right \rvert \geq 1$

such that for all

$\left \lvert {s}\right \rvert \geq 1$

such that for all

![]() $j < \left \lvert {s}\right \rvert $

, one of the following obtains for some

$j < \left \lvert {s}\right \rvert $

, one of the following obtains for some

![]() $n,m < j$

:

$n,m < j$

:

-

(1)

$s(j) = (0,n,n)$

,

$s(j) = (0,n,n)$

, -

(2)

$s(j) = (1,n,n)$

and

$s(j) = (1,n,n)$

and

$n < j$

,

$n < j$

, -

(3)

$s(j) = (2,n,m)$

and

$s(j) = (2,n,m)$

and

$n,m < j$

.

$n,m < j$

.

If s is a boolean formation sequence, then we write

![]() $s \in \mathrm {BFS}$

.

$s \in \mathrm {BFS}$

.

Fix a set

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and suppose that

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and suppose that

![]() $S = \mathopen {\langle } S_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is a countable sequence of subsets of V and that

$S = \mathopen {\langle } S_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is a countable sequence of subsets of V and that

![]() $\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle } A_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is an algebra of sets over V. A function

$\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle } A_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is an algebra of sets over V. A function

![]() $e : \mathrm {BFS} \to \mathbb {N}$

is a boolean embedding of S into

$e : \mathrm {BFS} \to \mathbb {N}$

is a boolean embedding of S into

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

if for all boolean formation sequences s with

$\mathcal {A}$

if for all boolean formation sequences s with

![]() $k = \left \lvert {s}\right \rvert - 1$

, there exist

$k = \left \lvert {s}\right \rvert - 1$

, there exist

![]() $n,m < s$

such that:

$n,m < s$

such that:

-

(1) If

$s(k) = (0,n,n),$

then

$s(k) = (0,n,n),$

then

$A_{e(s)} = S_n$

.

$A_{e(s)} = S_n$

. -

(2) If

$s(k) = (1,n,n)$

and

$s(k) = (1,n,n)$

and

$n < k$

, then

$n < k$

, then

$A_{e(s)} = A_{e(s\mathpunct {\restriction _{n+1}})}^c$

.

$A_{e(s)} = A_{e(s\mathpunct {\restriction _{n+1}})}^c$

. -

(3) If

$s(k) = (2,n,m)$

and

$s(k) = (2,n,m)$

and

$n,m < k$

, then

$n,m < k$

, then

$A_{e(s)} = A_{e(s\mathpunct {\restriction _{n+1}})} \cap A_{e(s\mathpunct {\restriction _{m+1}})}$

.

$A_{e(s)} = A_{e(s\mathpunct {\restriction _{n+1}})} \cap A_{e(s\mathpunct {\restriction _{m+1}})}$

.

The following lemma is a straightforward exercise in primitive recursion.

Lemma 2.3. The following is provable in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. Suppose

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. Suppose

![]() $S = \mathopen {\langle } S_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is a sequence of subsets of

$S = \mathopen {\langle } S_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is a sequence of subsets of

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

. Then there exists an algebra

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

. Then there exists an algebra

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

over V, a boolean embedding e of S into

$\mathcal {A}$

over V, a boolean embedding e of S into

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

, and a boolean embedding

$\mathcal {A}$

, and a boolean embedding

![]() $e^*$

from

$e^*$

from

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

into

$\mathcal {A}$

into

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

.

$\mathcal {A}$

.

Moreover, if S is already a countable algebra over V, then:

-

(1) For all

$m \in \mathbb {N}$

,

$m \in \mathbb {N}$

,

$S_m = A_{e(\mathopen {\langle }(0,m,m)\mathclose {\rangle })}$

.

$S_m = A_{e(\mathopen {\langle }(0,m,m)\mathclose {\rangle })}$

. -

(2) For all

$n \in \mathbb {N}$

, there exists

$n \in \mathbb {N}$

, there exists

$k \in \mathbb {N}$

such that

$k \in \mathbb {N}$

such that

$A_n = S_k$

.

$A_n = S_k$

.

Definition 2.4 (Ultrafilters).

Suppose

![]() $\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle }A_n : n \in N\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a countable algebra over

$\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle }A_n : n \in N\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a countable algebra over

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

.

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

.

![]() $\mathcal {U} \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is an ultrafilter on

$\mathcal {U} \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is an ultrafilter on

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

if it obeys the following conditions for all

$\mathcal {A}$

if it obeys the following conditions for all

![]() $i,j,k \in \mathbb {N}$

.

$i,j,k \in \mathbb {N}$

.

-

(1) (Non-emptiness.) If

$A_i = V$

, then

$A_i = V$

, then

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

.

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

. -

(2) (Properness.) If

$A_i = \emptyset $

, then

$A_i = \emptyset $

, then

$i \not \in \mathcal {U}$

.

$i \not \in \mathcal {U}$

. -

(3) (Upwards closure.) If

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

and

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

and

$A_i \subseteq A_j$

, then

$A_i \subseteq A_j$

, then

$j \in \mathcal {U}$

.

$j \in \mathcal {U}$

. -

(4) (Intersections.) If

$i,j \in \mathcal {U}$

and

$i,j \in \mathcal {U}$

and

$A_k = A_i \cap A_j$

, then

$A_k = A_i \cap A_j$

, then

$k \in \mathcal {U}$

.

$k \in \mathcal {U}$

. -

(5) (Maximality.) If

$A_j = A_i^c$

, then

$A_j = A_i^c$

, then

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

or

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

or

$j \in \mathcal {U}$

.

$j \in \mathcal {U}$

.

An ultrafilter

![]() $\mathcal {U}$

is principal if it obeys the following condition, and non-principal otherwise.

$\mathcal {U}$

is principal if it obeys the following condition, and non-principal otherwise.

-

(6) (Principality.) There exist

$k,d \in \mathbb {N}$

such that

$k,d \in \mathbb {N}$

such that

$k \in \mathcal {U}$

and

$k \in \mathcal {U}$

and

$A_k = \{ d \}$

.

$A_k = \{ d \}$

.

The next lemma is elementary, but worth stating as it is used a number of times.

Lemma 2.5. The following is provable in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. Suppose

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. Suppose

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is a countable atomic algebra over

$\mathcal {A}$

is a countable atomic algebra over

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {U} \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is an ultrafilter on

$\mathcal {U} \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is an ultrafilter on

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

. Then

$\mathcal {A}$

. Then

![]() $\mathcal {U}$

has the following properties for all

$\mathcal {U}$

has the following properties for all

![]() $i,j,k \in \mathbb {N}$

.

$i,j,k \in \mathbb {N}$

.

-

(1) If

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

and

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

and

$A_j = A_i^c$

, then

$A_j = A_i^c$

, then

$j \not \in \mathcal {U}$

.

$j \not \in \mathcal {U}$

. -

(2) If

$A_k = A_i \cup A_j$

and

$A_k = A_i \cup A_j$

and

$k \in \mathcal {U}$

, then either

$k \in \mathcal {U}$

, then either

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

or

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

or

$j \in \mathcal {U}$

.

$j \in \mathcal {U}$

. -

(3) Suppose

$\mathopen {\langle }Y_i : i < k\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a finite sequence of sets and

$\mathopen {\langle }Y_i : i < k\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a finite sequence of sets and

$s \in \mathrm {Seq}$

is such that

$s \in \mathrm {Seq}$

is such that

$\left \lvert {s}\right \rvert = k + 1$

. If

$\left \lvert {s}\right \rvert = k + 1$

. If

$Y_i = A_{s(i)}$

for all

$Y_i = A_{s(i)}$

for all

$i < k$

,

$i < k$

,

$(\bigcup _{i<k} Y_i) = A_{s(k)}$

, and

$(\bigcup _{i<k} Y_i) = A_{s(k)}$

, and

$s(k) \in \mathcal {U}$

, then there exists

$s(k) \in \mathcal {U}$

, then there exists

$j < k$

such that

$j < k$

such that

$s(j) \in \mathcal {U}$

.

$s(j) \in \mathcal {U}$

. -

(4) The following conditions are equivalent:

-

(a)

$\mathcal {U}$

is principal.

$\mathcal {U}$

is principal. -

(b) There exists

$k \in \mathbb {N}$

such that

$k \in \mathbb {N}$

such that

$A_k$

is finite and

$A_k$

is finite and

$k \in \mathcal {U}$

.

$k \in \mathcal {U}$

. -

(c) There exists

$d \in V$

such that for all

$d \in V$

such that for all

$i \in \mathbb {N}$

,

$i \in \mathbb {N}$

,

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

if and only if

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

if and only if

$d \in A_i$

.

$d \in A_i$

.

-

When we come to consider Fishburn’s possibility theorem in Section 5, we will need the following well-known result: the existence of non-principal ultrafilters on countable algebras is equivalent to arithmetical comprehension. This equivalence appears in its present guise as theorem 9 of Kreuzer [Reference Kreuzer31], but it has many antecedents. The proof of the forward direction presented here follows a partition construction from Kreuzer [Reference Kreuzer30], although similar ideas have been used by others, going back to Kirby and Paris [Reference Kirby, Paris, Lachlan, Srebrny and Zarach28] and Solovay [Reference Solovay49]. The reversal uses the fact that non-principal ultrafilters refine the Fréchet filter in order to code the jump, an idea drawn from Kirby [Reference Kirby27, theorem 1.10].

Lemma 2.6. The following are equivalent over

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

.

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

.

-

(1)

${\mathsf {ACA}}_0$

.

${\mathsf {ACA}}_0$

. -

(2) For every infinite set

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and every atomic countable algebra

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and every atomic countable algebra

$\mathcal {A}$

over V, there exists a non-principal ultrafilter

$\mathcal {A}$

over V, there exists a non-principal ultrafilter

$\mathcal {U}$

on

$\mathcal {U}$

on

$\mathcal {A}$

.

$\mathcal {A}$

.

Proof. We first show that 1 implies 2. Working in

![]() ${\mathsf {ACA}}_0$

, let

${\mathsf {ACA}}_0$

, let

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

be infinite and let

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

be infinite and let

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

be a countable algebra over V; we do not need the additional assumption that

$\mathcal {A}$

be a countable algebra over V; we do not need the additional assumption that

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is atomic. Given

$\mathcal {A}$

is atomic. Given

![]() $s \in 2^{<\mathbb {N}}$

, let

$s \in 2^{<\mathbb {N}}$

, let

$$ \begin{align} A^s = \bigcap_{i < \left\lvert{s}\right\rvert} \left\{\begin{array}{ll} A_i & \text{if } s(i) = 0, \\ (A_i)^c & \text{if } s(i) = 1. \end{array} \right. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} A^s = \bigcap_{i < \left\lvert{s}\right\rvert} \left\{\begin{array}{ll} A_i & \text{if } s(i) = 0, \\ (A_i)^c & \text{if } s(i) = 1. \end{array} \right. \end{align} $$

By

![]() $\Sigma ^0_0$

induction we have that for all

$\Sigma ^0_0$

induction we have that for all

![]() $v \in V$

,

$v \in V$

,

![]() $\forall {n}\exists {!s \in 2^n}(v \in A^s)$

. In other words,

$\forall {n}\exists {!s \in 2^n}(v \in A^s)$

. In other words,

![]() $\mathopen {\langle }A^s : s \in 2^n\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a partition of V. To see this, let

$\mathopen {\langle }A^s : s \in 2^n\mathclose {\rangle }$

is a partition of V. To see this, let

![]() $t \in 2^n$

be the unique sequence such that

$t \in 2^n$

be the unique sequence such that

![]() $z \in A^t$

.

$z \in A^t$

.

![]() $v \in A^{t\operatorname {\mathrm {\smallfrown }}\mathopen {\langle }0\mathclose {\rangle }} \leftrightarrow v \in A_{n+1}$

, so if

$v \in A^{t\operatorname {\mathrm {\smallfrown }}\mathopen {\langle }0\mathclose {\rangle }} \leftrightarrow v \in A_{n+1}$

, so if

![]() $v \in A_{n+1}$

we set

$v \in A_{n+1}$

we set

![]() $s = t\operatorname {\mathrm {\smallfrown }}\mathopen {\langle }0\mathclose {\rangle }$

and if

$s = t\operatorname {\mathrm {\smallfrown }}\mathopen {\langle }0\mathclose {\rangle }$

and if

![]() $v \not \in A_{n+1}$

then we set

$v \not \in A_{n+1}$

then we set

![]() $s = t\operatorname {\mathrm {\smallfrown }}\mathopen {\langle }1\mathclose {\rangle }$

. Since these possibilities are exclusive, either way

$s = t\operatorname {\mathrm {\smallfrown }}\mathopen {\langle }1\mathclose {\rangle }$

. Since these possibilities are exclusive, either way

![]() $s \in 2^{n+1}$

is the unique sequence such that

$s \in 2^{n+1}$

is the unique sequence such that

![]() $v \in A^s$

as desired. Now let

$v \in A^s$

as desired. Now let

T exists by arithmetical comprehension. We claim that T is an infinite tree. Suppose not, so there is some n such that for all

![]() $s \in 2^n$

,

$s \in 2^n$

,

![]() $A^s$

is finite. Let

$A^s$

is finite. Let

![]() $A' = \cup _{s \in 2^n} A^s$

.

$A' = \cup _{s \in 2^n} A^s$

.

![]() $A'$

is finite since every

$A'$

is finite since every

![]() $A^s$

is, so let m bound the elements of

$A^s$

is, so let m bound the elements of

![]() $A'$

. By assumption V is infinite, so there exists

$A'$

. By assumption V is infinite, so there exists

![]() $v \in V$

such that

$v \in V$

such that

![]() $v> m$

.

$v> m$

.

![]() $v \not \in A'$

so

$v \not \in A'$

so

![]() $v \not \in A^s$

for all

$v \not \in A^s$

for all

![]() $s \in 2^n$

, contradicting the fact that

$s \in 2^n$

, contradicting the fact that

![]() $\mathopen {\langle }A^s : s \in 2^n\mathclose {\rangle }$

partitions V. By weak König’s lemma that there exists an infinite path P in T, so let

$\mathopen {\langle }A^s : s \in 2^n\mathclose {\rangle }$

partitions V. By weak König’s lemma that there exists an infinite path P in T, so let

![]() $\mathcal {U} = \{ k : P(k) = 0 \}$

, which exists by recursive comprehension in the parameter P. To complete the proof we show that

$\mathcal {U} = \{ k : P(k) = 0 \}$

, which exists by recursive comprehension in the parameter P. To complete the proof we show that

![]() $\mathcal {U}$

is a non-principal ultrafilter on

$\mathcal {U}$

is a non-principal ultrafilter on

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

.

$\mathcal {A}$

.

To establish non-principality, it suffices to note that every

![]() $A_i$

such that

$A_i$

such that

![]() $i \in \mathcal {U}$

is infinite because

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

is infinite because

![]() $A^{P \mathpunct {\restriction _{i + 1}}}$

is an infinite subset of

$A^{P \mathpunct {\restriction _{i + 1}}}$

is an infinite subset of

![]() $A_i$

. To show maximality, let

$A_i$

. To show maximality, let

![]() $i \in \mathcal {U}$

be arbitrary with

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

be arbitrary with

![]() $(A_i)^c = A_j$

, and suppose

$(A_i)^c = A_j$

, and suppose

![]() $j \in \mathcal {U}$

. Let

$j \in \mathcal {U}$

. Let

![]() $k = \max \{ i,j \} + 1$

. Since, by our assumption,

$k = \max \{ i,j \} + 1$

. Since, by our assumption,

![]() $P(i) = P(j) = 0$

, we have that

$P(i) = P(j) = 0$

, we have that

![]() $A^{P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}}} = \emptyset $

, contradicting the fact that

$A^{P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}}} = \emptyset $

, contradicting the fact that

![]() ${P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}} \in T}$

and so

${P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}} \in T}$

and so

![]() $A^{P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}}}$

is infinite. To show that

$A^{P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}}}$

is infinite. To show that

![]() $\mathcal {U}$

is closed under intersections, let

$\mathcal {U}$

is closed under intersections, let

![]() $i,j \in \mathcal {U}$

, let

$i,j \in \mathcal {U}$

, let

![]() ${A_m = A_i \cap A_j}$

, and let

${A_m = A_i \cap A_j}$

, and let

![]() $A_n = (A_m)^c$

. Suppose for a contradiction that

$A_n = (A_m)^c$

. Suppose for a contradiction that

![]() $m \not \in \mathcal {U}$

, so by maximality

$m \not \in \mathcal {U}$

, so by maximality

![]() $A_n \in \mathcal {U}$

. Let

$A_n \in \mathcal {U}$

. Let

![]() $k = \max \{ i,j,m,n \} + 1$

. Then

$k = \max \{ i,j,m,n \} + 1$

. Then

![]() $A^{P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}}} = \emptyset $

, contradicting the fact that

$A^{P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}}} = \emptyset $

, contradicting the fact that

![]() $P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}} \in T$

. A similar argument establishes upwards closure. Take

$P \mathpunct {\restriction _{k}} \in T$

. A similar argument establishes upwards closure. Take

![]() $i \in \mathcal {U}$

and suppose

$i \in \mathcal {U}$

and suppose

![]() $A_i \subseteq A_j$

. Towards a contradiction assume that

$A_i \subseteq A_j$

. Towards a contradiction assume that

![]() $j \in \mathcal {U}$

, so by maximality and intersections if

$j \in \mathcal {U}$

, so by maximality and intersections if

![]() $A_k = A_i \cap (A_j)^c = \emptyset $

then

$A_k = A_i \cap (A_j)^c = \emptyset $

then

![]() $k \in \mathcal {U}$

, contradicting non-principality.

$k \in \mathcal {U}$

, contradicting non-principality.

Working now in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

, we show that 2 implies 1. To prove arithmetical comprehension it suffices to prove that the range of any one-to-one function

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

, we show that 2 implies 1. To prove arithmetical comprehension it suffices to prove that the range of any one-to-one function

![]() $h : \mathbb {N} \to \mathbb {N}$

exists [Reference Simpson48, lemma III.1.3, pp. 105–106]. The sequence

$h : \mathbb {N} \to \mathbb {N}$

exists [Reference Simpson48, lemma III.1.3, pp. 105–106]. The sequence

exists by recursive comprehension since all quantifiers in its definition are bounded, and by Lemma 2.3 there exists a countable algebra

![]() $\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle }A_i : i \in \mathbb {N}\mathclose {\rangle }$

over

$\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle }A_i : i \in \mathbb {N}\mathclose {\rangle }$

over

![]() $\mathbb {N}$

and a boolean embedding

$\mathbb {N}$

and a boolean embedding

![]() $e : \mathrm {BFS} \to \mathbb {N}$

of B into

$e : \mathrm {BFS} \to \mathbb {N}$

of B into

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

. The right-hand side of the union defining B ensures that

$\mathcal {A}$

. The right-hand side of the union defining B ensures that

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is atomic, i.e., it contains all singletons

$\mathcal {A}$

is atomic, i.e., it contains all singletons

![]() $\{v\}$

for

$\{v\}$

for

![]() $v \in V$

.

$v \in V$

.

For convenience we write

![]() $n'$

to mean

$n'$

to mean

![]() $e(\mathopen {\langle }(0,2n,2n)\mathclose {\rangle })$

, i.e., the index in

$e(\mathopen {\langle }(0,2n,2n)\mathclose {\rangle })$

, i.e., the index in

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

such that

$\mathcal {A}$

such that

![]() $A_{n'} = B_n$

.

$A_{n'} = B_n$

.

By 2 there exists

![]() $\mathcal {U} \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

such that

$\mathcal {U} \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

such that

![]() $\mathcal {U}$

is a non-principal ultrafilter on

$\mathcal {U}$

is a non-principal ultrafilter on

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

, and by recursive comprehension, the set

$\mathcal {A}$

, and by recursive comprehension, the set

![]() $Y = \{ n : n' \in \mathcal {U} \}$

exists. We show that

$Y = \{ n : n' \in \mathcal {U} \}$

exists. We show that

![]() $Y = \operatorname {\mathrm {ran}}(h) = \{ n : \exists {k}(h(k) = n) \}$

.

$Y = \operatorname {\mathrm {ran}}(h) = \{ n : \exists {k}(h(k) = n) \}$

.

Suppose

![]() $n \in Y$

, so

$n \in Y$

, so

![]() $n' \in \mathcal {U}$

and thus by non-principality

$n' \in \mathcal {U}$

and thus by non-principality

![]() $A_{n'}$

is non-empty, meaning there is some v such that

$A_{n'}$

is non-empty, meaning there is some v such that

![]() $(\exists {k<v})(h(k) = n)$

. It follows that

$(\exists {k<v})(h(k) = n)$

. It follows that

![]() $\exists {k}(h(k) = n)$

, i.e.,

$\exists {k}(h(k) = n)$

, i.e.,

![]() $n \in \operatorname {\mathrm {ran}}(h)$

. For the converse note that if

$n \in \operatorname {\mathrm {ran}}(h)$

. For the converse note that if

![]() $\exists {k}(h(k) = n)$

then

$\exists {k}(h(k) = n)$

then

![]() $A_{n'}$

is cofinite. To see this, fix any

$A_{n'}$

is cofinite. To see this, fix any

![]() $m \in A_{n'}$

and any

$m \in A_{n'}$

and any

![]() $j \in \mathbb {N}$

. Assume

$j \in \mathbb {N}$

. Assume

![]() $v + j \in A_{n'}$

, so there exists some

$v + j \in A_{n'}$

, so there exists some

![]() $k < v + j$

such that

$k < v + j$

such that

![]() $h(k) = n$

.

$h(k) = n$

.

![]() $k < v + j + 1$

, so by

$k < v + j + 1$

, so by

![]() $\Sigma ^0_0$

induction, for all j,

$\Sigma ^0_0$

induction, for all j,

![]() $v + j \in A_{n'}$

. Consequently

$v + j \in A_{n'}$

. Consequently

![]() $A_{n'}$

is cofinite and so by maximality

$A_{n'}$

is cofinite and so by maximality

![]() $n' \in \mathcal {U}$

, and thus

$n' \in \mathcal {U}$

, and thus

![]() $n \in Y$

.

$n \in Y$

.

2.3 Orderings in social choice theory

The paper aims to be self-contained where notions from social choice theory are concerned, but a good starting point for a deeper study is Taylor’s monograph Social Choice and the Mathematics of Manipulation [Reference Taylor51]. In social choice theory, voters express their preferences as orders on the set of alternatives X (e.g., ranking candidates in an election). These orders are required to be transitive and strongly connected, but ties are permitted to express indifference between alternatives. This notion is standardly called a weak order in the social choice theory literature, and we follow this terminology here, noting that it is synonymous with the notion of a total preorder. In this paper we will be concerned exclusively with finite sets of alternatives X, and hence all our weak orders will be assumed to be coded by natural numbers.

Definition 2.7 (Weak orders).

Suppose

![]() $X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and

$X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and

![]() $R \subseteq X \times X$

. R is strongly connected if

$R \subseteq X \times X$

. R is strongly connected if

![]() $(x,y) \in R$

or

$(x,y) \in R$

or

![]() $(y,x) \in R$

for all

$(y,x) \in R$

for all

![]() $x,y \in X$

.

$x,y \in X$

.

If R is a transitive and strongly connected relation then we call it a weak order and write

![]() $x \lesssim _R y$

to mean

$x \lesssim _R y$

to mean

![]() $(x,y) \in R$

,

$(x,y) \in R$

,

![]() $x <_R y$

to mean

$x <_R y$

to mean

![]() $(x,y) \in R \wedge (y,x) \not \in R$

, and

$(x,y) \in R \wedge (y,x) \not \in R$

, and

![]() $x \sim _R y$

to mean

$x \sim _R y$

to mean

![]() $(x,y) \in R \wedge (y,x) \in R$

.

$(x,y) \in R \wedge (y,x) \in R$

.

Many basic properties of weak orders can be established in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. For example, if R is a weak order then:

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. For example, if R is a weak order then:

-

(1)

$\lesssim _R$

is reflexive.

$\lesssim _R$

is reflexive. -

(2)

$\sim _R$

is an equivalence relation on X.

$\sim _R$

is an equivalence relation on X. -

(3) If

$x <_R z$

then

$x <_R z$

then

$x <_R y$

or

$x <_R y$

or

$y <_R z$

(negative transitivity).

$y <_R z$

(negative transitivity).

Given a set

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

of voters and a finite set

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

of voters and a finite set

![]() $X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

of alternatives, we let W be the set of all (codes for) weak orders on X. A profile is a function

$X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

of alternatives, we let W be the set of all (codes for) weak orders on X. A profile is a function

![]() $f : V \to W$

. In practice we will always be concerned with countable sequences

$f : V \to W$

. In practice we will always be concerned with countable sequences

![]() $\mathcal {F} = \mathopen {\langle } f_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

of profiles. If

$\mathcal {F} = \mathopen {\langle } f_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

of profiles. If

![]() $f_i$

is a profile and

$f_i$

is a profile and

![]() $v \in V$

is a voter then we write

$v \in V$

is a voter then we write

![]() $x \lesssim _{i(v)} y$

to mean that

$x \lesssim _{i(v)} y$

to mean that

![]() $x \lesssim _R y$

where

$x \lesssim _R y$

where

![]() $R = f_i(v)$

, i.e., that alternative x is preferred to y by voter v in the voting scenario represented by the profile

$R = f_i(v)$

, i.e., that alternative x is preferred to y by voter v in the voting scenario represented by the profile

![]() $f_i$

. Similarly we write

$f_i$

. Similarly we write

![]() $x <_{i(v)} y$

to mean

$x <_{i(v)} y$

to mean

![]() $x <_R y$

, and

$x <_R y$

, and

![]() $x \sim _{i(v)} y$

to mean

$x \sim _{i(v)} y$

to mean

![]() $x \sim _R y$

.

$x \sim _R y$

.

A coalition is simply a set

![]() $C \subseteq V$

of voters; by convention, we allow both the empty set and singleton sets containing only one voter to count as coalitions. Given a coalition C, we write

$C \subseteq V$

of voters; by convention, we allow both the empty set and singleton sets containing only one voter to count as coalitions. Given a coalition C, we write

![]() $x \lesssim _{i[C]} y$

to mean that

$x \lesssim _{i[C]} y$

to mean that

![]() $x \lesssim _{i(v)} y$

for all

$x \lesssim _{i(v)} y$

for all

![]() $v \in C$

, and

$v \in C$

, and

![]() $x <_{i[C]} y$

and

$x <_{i[C]} y$

and

![]() $x \sim _{i[C]} y$

have their obvious meanings.

$x \sim _{i[C]} y$

have their obvious meanings.

If

![]() $Y \subseteq X$

, we write

$Y \subseteq X$

, we write

![]() $f_i(v) = f_j(v)$

on Y to mean that

$f_i(v) = f_j(v)$

on Y to mean that

![]() $x \lesssim _{i(v)} y \leftrightarrow x \lesssim _{j(v)} y$

for all

$x \lesssim _{i(v)} y \leftrightarrow x \lesssim _{j(v)} y$

for all

![]() $x,y \in Y$

, i.e., that v’s preferences regarding all x and y in S are the same under both the voting scenarios represented by the profiles

$x,y \in Y$

, i.e., that v’s preferences regarding all x and y in S are the same under both the voting scenarios represented by the profiles

![]() $f_i$

and

$f_i$

and

![]() $f_j$

. We write

$f_j$

. We write

![]() $f_i = f_j$

on Y to mean that

$f_i = f_j$

on Y to mean that

![]() $f_i(v) = f_j(v)$

on Y for all

$f_i(v) = f_j(v)$

on Y for all

![]() $v \in V$

.

$v \in V$

.

3 Countable societies

In the classical social choice literature, the notion of a society has been generalised by Armstrong [Reference Armstrong1] to allow

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

to be any algebra of sets over V, rather than all of

$\mathcal {A}$

to be any algebra of sets over V, rather than all of

![]() ${\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

. In Armstrong’s generalisation

${\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

. In Armstrong’s generalisation

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

is always the set of all

$\mathcal {F}$

is always the set of all

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

-measurable profiles, i.e., those

$\mathcal {A}$

-measurable profiles, i.e., those

![]() $f : V \to W$

such that for all

$f : V \to W$

such that for all

![]() $x,y \in X$

,

$x,y \in X$

,

![]() $\{ v : x \lesssim _{f(v)} y \} \in \mathcal {A}$

. This paper only addresses the countable case, i.e., when not only V but also

$\{ v : x \lesssim _{f(v)} y \} \in \mathcal {A}$

. This paper only addresses the countable case, i.e., when not only V but also

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

and

$\mathcal {A}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

are countable objects that can be coded by sets of natural numbers.Footnote

7

$\mathcal {F}$

are countable objects that can be coded by sets of natural numbers.Footnote

7

A countable society consists of a set of voters

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

, a finite set of alternatives

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

, a finite set of alternatives

![]() $X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and the associated set W of weak orders on X, an atomic countable algebra of coalitions

$X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

and the associated set W of weak orders on X, an atomic countable algebra of coalitions

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

, and a countable sequence of profiles

$\mathcal {A}$

, and a countable sequence of profiles

![]() $\mathcal {F} = \mathopen {\langle } f_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

over

$\mathcal {F} = \mathopen {\langle } f_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

over

![]() $V,X$

(i.e., for all i,

$V,X$

(i.e., for all i,

![]() $f_i$

is a function from V to W). However, in order for theorems about countable societies to continue to make sense in the way they do when

$f_i$

is a function from V to W). However, in order for theorems about countable societies to continue to make sense in the way they do when

![]() $\mathcal {A} = {\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

and

$\mathcal {A} = {\mathcal {P}{(V)}}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {F} = W^V$

, we need to impose certain conditions on

$\mathcal {F} = W^V$

, we need to impose certain conditions on

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

and

$\mathcal {A}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

. The first such condition is that profiles in

$\mathcal {F}$

. The first such condition is that profiles in

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

are measurable by coalitions in

$\mathcal {F}$

are measurable by coalitions in

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

. Measurability must also be uniform, to ensure that proofs using it can be carried out in

$\mathcal {A}$

. Measurability must also be uniform, to ensure that proofs using it can be carried out in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

.

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

.

Definition 3.1 (Uniform measurability).

Suppose

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and

![]() $X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is finite, and that

$X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is finite, and that

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is a countable algebra of sets over V and

$\mathcal {A}$

is a countable algebra of sets over V and

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

is a countable sequence of profiles over

$\mathcal {F}$

is a countable sequence of profiles over

![]() $V,X$

. If there exists

$V,X$

. If there exists

![]() $\mu : \mathbb {N} \times X \times X \to \mathbb {N}$

such that for all

$\mu : \mathbb {N} \times X \times X \to \mathbb {N}$

such that for all

![]() $n \in \mathbb {N}$

,

$n \in \mathbb {N}$

,

![]() $x,y \in X$

, and

$x,y \in X$

, and

![]() $v \in V$

,

$v \in V$

,

then we say

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

is uniformly

$\mathcal {F}$

is uniformly

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

-measurable.

$\mathcal {A}$

-measurable.

Lemma 3.2. The following is provable in

![]() ${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. Suppose

${\mathsf {RCA}}_0$

. Suppose

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and

![]() $X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and finite, and that

$X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and finite, and that

![]() $\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle } A_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is a countable algebra of sets over V and

$\mathcal {A} = \mathopen {\langle } A_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is a countable algebra of sets over V and

![]() $\mathcal {F} = \mathopen {\langle } f_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is a countable sequence of profiles over

$\mathcal {F} = \mathopen {\langle } f_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

is a countable sequence of profiles over

![]() $V,X$

. If

$V,X$

. If

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

is uniformly

$\mathcal {F}$

is uniformly

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

-measurable then there exist functions

$\mathcal {A}$

-measurable then there exist functions

![]() $\mu _{<}, \mu _{\sim } : \mathbb {N} \times X \times X \to \mathbb {N}$

such that for all

$\mu _{<}, \mu _{\sim } : \mathbb {N} \times X \times X \to \mathbb {N}$

such that for all

![]() $n \in \mathbb {N}$

,

$n \in \mathbb {N}$

,

![]() $x,y \in X$

, and

$x,y \in X$

, and

![]() $v \in V$

,

$v \in V$

,

and

The second condition, quasi-partition embedding, ensures that finite sequences of coalitions in

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

can be recovered uniformly from profiles in

$\mathcal {A}$

can be recovered uniformly from profiles in

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

. This condition emerges naturally from the proofs of the Kirman–Sondermann theorem and Fishburn’s possibility theorem, although to the best of our knowledge it is isolated here for the first time.Footnote

8

Quasi-partitions of V, in which overlaps are allowed, are preferred to partitions since they are more computationally tractable.Footnote

9

$\mathcal {F}$

. This condition emerges naturally from the proofs of the Kirman–Sondermann theorem and Fishburn’s possibility theorem, although to the best of our knowledge it is isolated here for the first time.Footnote

8

Quasi-partitions of V, in which overlaps are allowed, are preferred to partitions since they are more computationally tractable.Footnote

9

Definition 3.3 (Quasi-partition embedding).

Suppose

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is nonempty and

![]() $X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is finite with

$X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

is finite with

![]() $|X| \geq 3$

, and that

$|X| \geq 3$

, and that

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is a countable algebra of sets over V and

$\mathcal {A}$

is a countable algebra of sets over V and

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

is a countable profile algebra over

$\mathcal {F}$

is a countable profile algebra over

![]() $V,X$

. A permutation of a finite set W is a finite sequence

$V,X$

. A permutation of a finite set W is a finite sequence

![]() $p \in \mathrm {Seq}$

such that for all (codes for) weak orders

$p \in \mathrm {Seq}$

such that for all (codes for) weak orders

![]() $R \in W$

there exists a unique i such that

$R \in W$

there exists a unique i such that

![]() $p(i) = R$

. We write

$p(i) = R$

. We write

![]() $p \in \mathrm {Perm}(W)$

to indicate that p is a permutation of W. A quasi-partition is a finite sequence

$p \in \mathrm {Perm}(W)$

to indicate that p is a permutation of W. A quasi-partition is a finite sequence

![]() $s \in \mathrm {Seq}$

such that

$s \in \mathrm {Seq}$

such that

![]() $1 \leq \left \lvert {s}\right \rvert $

. We write

$1 \leq \left \lvert {s}\right \rvert $

. We write

![]() $s \in \mathrm {QPart}(k)$

to indicate that s is a quasi-partition with

$s \in \mathrm {QPart}(k)$

to indicate that s is a quasi-partition with

![]() $\left \lvert {s}\right \rvert \leq k$

.

$\left \lvert {s}\right \rvert \leq k$

.

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is quasi-partition embedded into

$\mathcal {A}$

is quasi-partition embedded into

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

if there exists a function

$\mathcal {F}$

if there exists a function

![]() $e : \mathrm {Perm}(W) \times \mathrm {QPart}(\left \lvert {W}\right \rvert ) \to \mathbb {N}$

such that for all

$e : \mathrm {Perm}(W) \times \mathrm {QPart}(\left \lvert {W}\right \rvert ) \to \mathbb {N}$

such that for all

![]() $v \in V$

,

$v \in V$

,

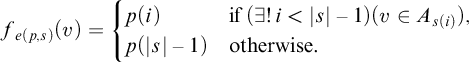

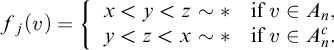

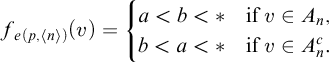

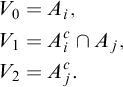

$$ \begin{align*} f_{e(p,s)}(v) = \begin{cases} p(i) & \text{if }(\exists{!i < \left\lvert{s}\right\rvert-1}) (v \in A_{s(i)}), \\ p(\left\lvert{s}\right\rvert - 1) & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f_{e(p,s)}(v) = \begin{cases} p(i) & \text{if }(\exists{!i < \left\lvert{s}\right\rvert-1}) (v \in A_{s(i)}), \\ p(\left\lvert{s}\right\rvert - 1) & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

Definition 3.4 (Countable societies).

A countable society

![]() $\mathcal {S}$

consists of a nonempty set

$\mathcal {S}$

consists of a nonempty set

![]() $V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

of voters, a finite set

$V \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

of voters, a finite set

![]() $X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

of alternatives with

$X \subseteq \mathbb {N}$

of alternatives with

![]() $|X| \geq 3$

, an atomic countable algebra

$|X| \geq 3$

, an atomic countable algebra

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

over V, and a sequence

$\mathcal {A}$

over V, and a sequence

![]() $\mathcal {F} = \mathopen {\langle } f_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

of profiles over

$\mathcal {F} = \mathopen {\langle } f_i : i \in \mathbb {N} \mathclose {\rangle }$

of profiles over

![]() $V,X$

such that

$V,X$

such that

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

is uniformly

$\mathcal {F}$

is uniformly

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

-measurable and

$\mathcal {A}$

-measurable and

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is quasi-partition embedded into

$\mathcal {A}$

is quasi-partition embedded into

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

.

$\mathcal {F}$

.

A countable society

![]() $\mathcal {S}$

is finite if V is finite, and infinite otherwise.

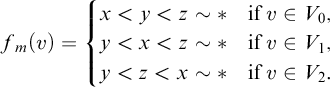

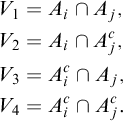

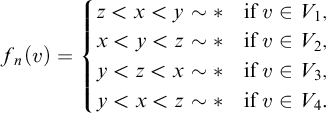

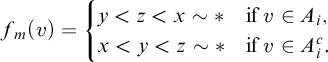

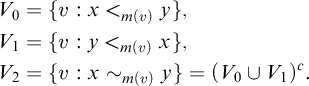

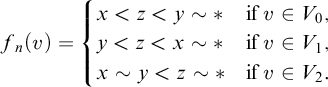

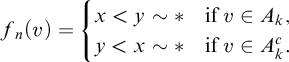

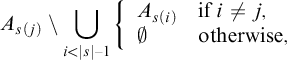

$\mathcal {S}$