Introduction

This article analyses the implementation of a major project for agricultural development, the irrigation of an extensive area by a leading seigneurial house in one of eighteenth-century Spain’s most economically advanced regions. This involved the construction of a substantial irrigation canal by an aristocrat, the ninth Duke of Híjar, who enjoyed strong connections with circles of courtly power of the period.Footnote 1 The scheme set out to increase the irrigated surface area, agricultural production, land values, and the incomes of the Duke and the monarchy itself. The canal was expected to irrigate lands of the Híjar estate but also, and above all, those of other adjacent estates owned by other aristocratic landlords, smaller landowners in surrounding municipalities, and by the Crown. The latter possessed several royal estates in the area that would benefit from the new irrigation system. In particular, the area around the Albufera lagoon was occupied by marshlands that the Crown hoped to drain and transform into irrigated farmland by ceding them to colonos or tenant farmers. This significant socio-economic change would increase the income of the monarch, since the newly cultivated areas would be required to pay regular fees to the Crown estates. In addition, the whole of the irrigation scheme promoted by the Duke would increase payments to the royal exchequer, due to its receiving a portion of the diezmos or ecclesiastical tithes, income from which could be expected to increase as the scheme progressed.

Híjar would supply water to all of them, in exchange for regular fees. The canal planned by the Duke was a prolongation of another that had existed since the Middle Ages, so that both together would form a single larger canal, to be called the ‘Acequia Real del Júcar’ (‘Royal Irrigation Canal of the River Júcar’). The project consequently met with opposition from landowners in the areas that for centuries had already received water from the older canal. To overcome this opposition, the house of Híjar could call on the support of the bureaucratic apparatus of the absolute monarchy. Construction of the canal took a long time. Begun in 1771, it irrigated an extensive area by 1790, but did not become fully operational until 1815.

In the second half of the eighteenth century the idea became increasingly accepted in Spain that the aridity of the country’s climate was one of the principal obstacles to the growth of its agriculture. Enlightenment writers and senior officials of the Crown were in agreement in pointing to irrigation as the solution to these environmental limitations. From then on, and into the next century, the promotion of hydraulic engineering schemes became a goal shared equally by governments of all kinds, namely agronomists and rural economists. The first effort in this direction was made under the absolute monarchy, when a política hidráulica or ‘water policy’ was formulated with the aim of building canals for both navigation and irrigation.Footnote 2 This produced some notable results, such as the Canal of Castile between Palencia and Valladolid, the Canal Imperial in Aragon, and the Acequia Real del Júcar. However, these projects brought only a partial transformation in the country’s agriculture, and were soon interrupted by the political convulsions of the last stages of the absolutist regime.

For Mediterranean agriculture, the extension of irrigation represented a technological change as far-reaching in importance as the transformations of the agricultural revolution were for Atlantic Europe. It was the principal means of achieving increases in productivity. However, expanding irrigation by building a canal was a form of agricultural intensification that required the collaboration of a range of social actors, and the approval or participation of government. A scheme of this kind also demanded substantial capital, and its subsequent management would require clear norms of action and an institutional structure to ensure they were observed. Ultimately, the role taken by the state would be of decisive importance for the stability of these institutions. Hence, changes in the balance of social and political forces in the country as a whole could lead to alterations in the operation of a system of irrigation.

Spain’s liberal revolution, a prolonged process that extended from 1812 to 1837, represented a radical break with the structures that had characterised Spanish society, and with the social foundations of the old monarchy. A profound recasting of social hierarchies took place, with the erosion of the economic and political power of the nobility and the rise of new sectors of wealth rooted in landownership and business. This raises the question of how such a process could affect an agrarian intensification project like the Acequia Real del Júcar, initiated by an aristocrat linked to the Enlightened circles of the old regime, and supported politically by the absolute monarchy. This article will seek to answer this question, particularly in terms of the following specific aspects: whether changes were seen in the management of the canal, whether there were changes in the social status and identity of the beneficiaries of the water, and, ultimately, whether these transformations affected the overall growth in agricultural production based on irrigation. Hence both the institutional framework and the social characteristics of the protagonists in the expansion of irrigation form the object of this study.

At the same time, these questions raise the broader issue of the degree of continuity or radical transformation in agrarian development between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in the transition from the ancien régime to liberal society.Footnote 3 In continental Europe, the socio-economic background to these decades was not defined by economic stagnation, as is often claimed. On the contrary, the agrarian societies of the era generated powerful dynamics in many areas. The rivalries between the major European powers multiplied stimuli for the introduction of important changes, especially from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, initially intended to enable these regimes to maintain or increase their power. These included economic reforms, aimed at broadening the demographic and tax base of the various monarchies. The expansion of irrigation promoted by the Spanish Crown and the specific case we are examining here are prominent examples of this tendency.

Firstly, we examine the scenario within which the Júcar initiative succeeded in getting off the ground. In a later section, we analyse the forces and circumstances that led to changes from the initial terms of the irrigation project. Finally, we examine the consolidation, in the era of the nineteenth-century liberal state, of economic and social consequences that were very different from those initially anticipated for the scheme.

‘Progress’ in the conflicted social space of absolute monarchy: the construction of an irrigation canal

In the Valencian Region a well-established irrigation agriculture already existed, a situation that was significantly different from that of the Spanish interior in the eighteenth century. Market-oriented agricultural production, private landownership detached from communal uses, and land exploitation through lease contracts and wage labour were all already commonplace in a region that was experiencing major economic growth, with approximately fifty inhabitants per square kilometre in around 1800. This growth was also influenced by an urban boom in the city of Valencia, with the population doubling in the period 1716–87, to reach around 100,000 inhabitants in 1800. These trends all stimulated the production, among other crops, of rice, with the aim of answering a worsening broader food shortage. In turn, high agricultural profitability fuelled demand for land among families that had made their money through business in urban areas.Footnote 4 Consequently, the ownership of land spread across a heterogeneous mix of social sectors: aristocrats, smallholder farmers, local lesser landowners, and landowners from the city.

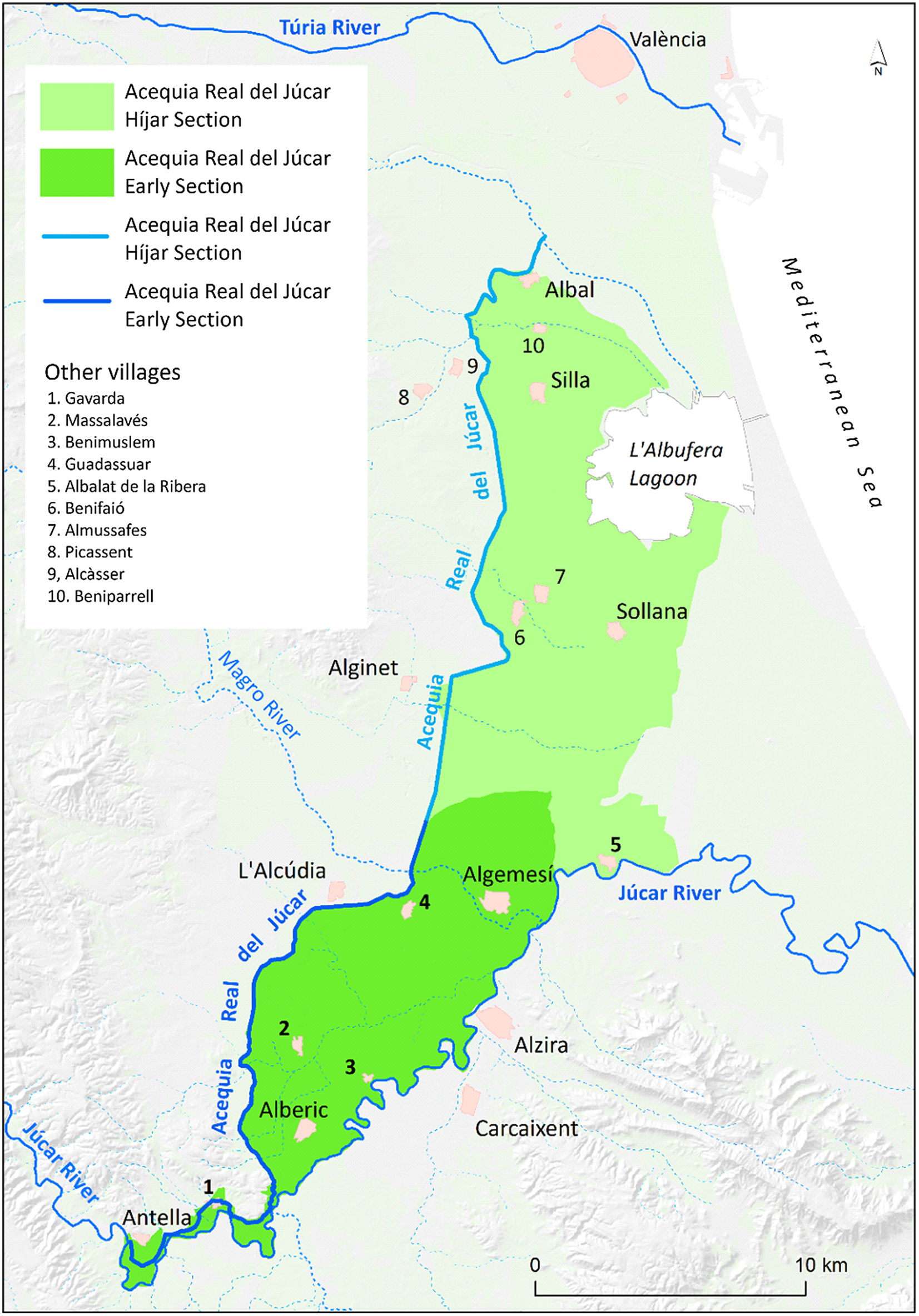

This was the context in which the proposal was made in the 1760s for a new, large-scale irrigation project, which would complete what was already an extensive surface area under irrigation in the region (see Figure 1).Footnote 5 The new scheme was to be constructed by an aristocrat, the Duke of Híjar, who would invest his own resources and credit. In return, its promoter hoped to obtain a new source of income.

Figure 1. Irrigated area by the Acequia Real del Júcar, mid-nineteenth century.

Pedro de Alcántara y Abarca de Bolea, who had been ninth Duke of Híjar since 1758, was the head of one of the foremost noble houses of Spain, with particularly large estates in Aragon, where he was the principal landowner.Footnote 6 In Valencia, however, the foundations of his fortune were more fragile. His estates had eight thousand vassals, placing him in a discreet fourteenth position among the lords of the region. One of his Valencian estates, the small lordship of Sollana, was located in the area that would benefit from the new canal, and this was why he took the initiative in proposing its construction.Footnote 7 His involvement heralded a major transformation of this modest property, with a rise in economic prominence and a new role as a link between local society and central authority. In assuming responsibility for a project that also interested the Crown, the Duke’s initiative could signify the ascent of an old seigneurial house, which would thus gain the undisputed status as one of the region’s magnates, protected by central power. This would greatly increase his influence. The Duke would be able to assign or refuse irrigation in a very extensive and much-coveted area, far beyond his own seigneurial dominions in Sollana.Footnote 8

Pedro de Alcántara did not leave any writings that stand out among the publications of the Spanish Enlightenment. However, in some brief texts his son, the future tenth Duke, did express his idea of the role that should be played by an aristocrat in the society of the old regime. In this Duke’s view, his activities were not to be seen as simple instruments of the progress promoted by the Crown.Footnote 9 He presented himself instead as an eminent figure in his own right, in a society respectful of internal hierarchy, as a patriotic spokesperson and benefactor who enjoyed the support of the Crown, in recognition of his enterprise.Footnote 10

The ninth Duke had embarked upon his new irrigation project in accordance with similar ideas on progress and the role of the aristocracy. It involved channelling water to an extensive area that had remained outside the lands served by the original Júcar canal.Footnote 11 Both the monarchy, with its own extensive estates, and the House of Híjar, with the lordship of Sollana, had particular interest in the project. In addition, other municipalities nearby (Silla, Benifaió, Almussafes and Picassent) also sought to gain access to irrigation water, through their own nobles, groups of landowners, or municipal authorities. However, a previous attempt to extend the old canal in 1768 had failed due to a violent protest by the irrigators with water rights from the historic canal.Footnote 12 In response, King Charles III appointed a judge to supervise the work and overcome, with coercion if necessary, the resistance of those opposed to the project. This new authority would remain at the head of the canal for six decades.

In 1771 the Royal Council established the general terms for the canal project: a judge appointed by the King would supervise the new scheme, and administer the funds supplied by Híjar. In return, the Duke would receive one twentieth of the harvests from the newly irrigated lands (the veintena).Footnote 13 It would thus be Híjar who would finance the construction work, which would nevertheless be overseen jointly by himself and by an authority appointed by the Crown.

Work began in the same year of 1771, but the extension of the irrigation canal very soon took on a growing complexity. The plan required coordinated action by the Duke, who had received the concession from the Crown, and assumed the financial costs; thousands of potential irrigators from diverse social backgrounds; the municipalities, bastions of local oligarchies but, at the same time, active agents that expressed collective interests; and finally, a considerable number of beneficiaries of the old canal that had existed since medieval times, who were opposed to the extension of irrigation. The appointed judge, as royal commissioner, needed to guarantee success. To this end, he extended the radius of his authority, marginalising the interventions of a variety of actors with strong roots in the area. The royal judge stripped the traditional authorities of the old canal of their decision-making powers, in such fields as the distribution of water among irrigators, the maintenance of irrigation infrastructure, the collection of fees, the determination of the order in which water was distributed, and the imposition of fines for contraventions of the rules. A new authority replaced the figures formerly responsible for canal management.Footnote 14 This new concentration of power was not generally accepted among the traditional irrigators, who repeatedly protested to the Royal Council, but to no avail.

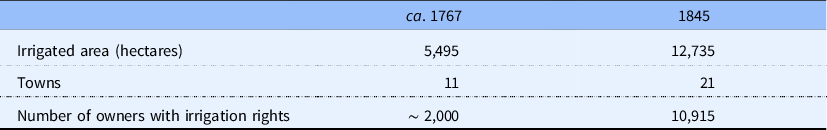

As the construction work progressed, irrigation water was supplied to the properties that requested it, subject to the prior approval of the Duke of Híjar and the judge. Between them they decided who would receive water and who would not.Footnote 15 The first water reached some villages in the 1790s, but it was not until after 1815 that it would reach all the potential area. The new water course revolutionised agriculture in the area. Table 1 shows the increase in scale of irrigation from the canal. In an era of major political difficulties, and in the context of pre-industrial techniques, water radically transformed the conditions of production in an extensive area of rice cultivation.

Table 1. Growth of irrigated area by the Acequia Real del Júcar

Source: S. Calatayud and S. Garrido, ‘Negociación de normas e intervención estatal en la gestión del regadío: la Acequia Real del Júcar a mediados del siglo XIX’, Hispania, LXXII:240 (2012), 101.

The concessions granted for irrigation sought to maximise land productivity and, therefore, the part of each harvest that would correspond to the Duke through the veintena. The procedure for gaining access to irrigation waters conferred upon the Duke and the royal authority associated with him an ability to act selectively. Officially the criteria to be employed were technical, and involved the selection of applicants and the classification of their landholdings according to their suitability for irrigation. Experts, sent by the judge, were to inspect properties and issue a report.Footnote 16 Crucial aspects were the characteristics of the soil and its prior preparation for irrigation. Excessive soil salinity augured poor harvests and, consequently, lower income per veintena.Footnote 17 Concessions were thus based on criteria of profitability and the economic use of water. All these procedures were intended to facilitate the growing of rice in the best possible conditions.

The extension of the Acequia del Júcar is interesting on two levels, as a means of stimulating agricultural progress and, at the same time, as a reformulation of the articulation of the local powers of the monarchy. Just as in Mediterranean France in the same period, the extension of irrigation represented a very attractive use for noble fortunes. An undertaking of this kind brought both public recognition and increased revenues. However, the implementation of such projects clashed with powerful obstacles within the political order of the old regime. When a canal ran across extensive areas, it inevitably crossed diverse jurisdictional boundaries. It therefore affected different community and aristocratic authorities, which, as autonomous power bases under the monarchy, could not easily be forced to cooperate. This non-cooperative behaviour was lethal. In France in the second half of the eighteenth century – under a monarchy that in principle was more absolute and more centralised than in Spain – obstructions of this kind delayed or ruined various projects. Only the reconfiguration of political power after 1789 made possible the imposition of the sovereignty of the state, overriding the many corporate and local rights.Footnote 18

As to the pattern seen under the Spanish monarchy, the Bourbon dynasty, since it arrived on the throne in 1700, had been able to implement some projects for agricultural progress based on irrigation schemes, in some regions.Footnote 19 What is particularly interesting about the Híjar project, however, is the ease with which the monarchy’s support removed these obstacles, which seemed inherent to the social order of absolutism.

With apparent ease, the royal authorities took some steps forward that often proved to be the undoing of similar projects in Provence. The men responsible for overcoming these obstacles in Valencia were judges trained in public law, and men known in Enlightened circles of the time. Juan Casamayor, Lorenzo Bachiller and José A. Fernández Blanco, successive occupants of the post overseeing the Acequia Real del Júcar, were civil servants with experience in the legal aspects of irrigation and in the Crown’s relationships with local powers.Footnote 20 It was precisely the novel figure of these judges that was intended to transcend this conflictive tangle of interests and replace it with a clear route towards progress, with an authority established as an undisputed proponent of the common good. Appointed by those in power at court, technically qualified and acclaimed in lofty circles, aloof, like foreigners, from local networks of favours and rivalries, they could present themselves as impartial upholders of the general interest. For their sponsors – in accordance with the typical trust of the Age of Enlightenment in the capacity of ‘reason’ to win support per se – all these new officials would eliminate obstacles and ensure collaboration with a project that would bring progress, under the auspices of the supreme authority in the kingdom.

However, after initial successes the construction of the canal would encounter problems of two kinds. One was related to the management of the new irrigation system by the Duke. The other derived from the declining legitimacy of the absolute monarch. Both became intertwined, and put an end to the expectations the Duke had created.

The canal’s construction forced the House of Híjar to go heavily into debt. The Júcar canal project made it necessary for the ninth Duke to borrow over five million reales between 1770 and 1790.Footnote 21 Receipt of the veintena should have served to finance these loans. In practice, however, the difficulties he met in collecting these payments made it impossible to meet his commitments for decades.Footnote 22 The first half of the nineteenth century would see a raft of foreclosures and sales of assets, as the debt contributed to the Híjars’ ruin, as will be explored.

This raises the question of why income from irrigation fees was so much less than expected. The construction of the canal was not based on any consensus, but became a focus of conflict. The vision of progress shared by Híjar and the Crown-appointed judges ignored the complex patchwork of bottom-up relationships and conflicts generated by irrigation at a local level, and the multiple informal mechanisms that minimised conflict in irrigation systems.Footnote 23 In the irrigation systems of Mediterranean Spain, water management had traditionally been carried out with the active participation of the users of water, or at least of those with the greatest areas of irrigated land. Moreover, the canals, channels and infrastructure of the system were regarded, as a whole, as collective property. In these circumstances, the multitude of minor conflicts that arose around the daily use of water – which were very common, since these were areas characterised by water scarcity – were nearly always resolved through negotiation and a search for consensus among water users. These consensus agreements also included the small-scale water users, who did not habitually participate in decision-making, but had to be guaranteed their rights to access water. This was necessary to prevent any discontent developing into individual or collective responses that might lead them to seize water illicitly or cause damage to fragile and vulnerable ditches and canals. Similarly, a lack of general cooperation, such as for example by failing to pay irrigation fees, might also affect the maintenance of infrastructure and the viability of the system. The poorest sectors of local society thus had some ability to act in ways that could cause significant damage to the irrigation system as a whole. Such irrigation systems were therefore based on maintaining some form of balance between users of different social status, as well as on a shared knowledge of the land and the everyday demands of cultivation. In contrast, the management system introduced by the Duke of Híjar for the canal of which he was sole owner was based on a hierarchy of employees controlled from above, and without any participation in decision-making for the users. Consequently, disagreements between the water users and the agents charged with management of the canal had to be approached without the legitimacy given by the traditional mechanisms of cooperation.

Along the Acequia Real del Júcar, resistance to payment emerged from the beginning, and continued into the following decades. The problem was not, however, one of simple hardship. Of decisive influence were the controversial criteria employed to legitimise authorities and hierarchies, in a context in which the inherited political system and social order of the old regime were coming into question. The crisis of the system prevented the canal from being seen as the fruit of a commendable investment, which would justifiably confer rights over its beneficiaries upon its promoters.

In the crisis of the absolute monarchy, this resistance to paying irrigation fees was part of a wider questioning of what were considered ‘feudal’ rights. The extension of irrigation had encouraged the rise of a certain elite group of landowners in Sollana and nearby towns, who were opposed to the traditional system of seigneurial rights, and extended this opposition to payment of the veintena, despite the fact that this charge derived from the Duke’s private ownership of a large section of the canal.Footnote 24

This delegitimisation of his ownership of the canal did not arise in response to any failings in the execution of the project. As has been noted, the canal would have a major impact upon agriculture in the region, allowing the expansion of rice growing into a larger area. However, the irrigation system, though an indisputable example of progress, became caught up in the bitter process of the generalised questioning of absolute monarchy.

The new social foundations of agricultural progress and the liberal state: the changes in the management of the canal

The collapse of the traditional monarchy in the wake of the French invasion and the 1812 Constitution, the launching pad for a new liberal state, radically disrupted the earlier process of canal management. The initial successes of the Crown’s officials in technical aspects, which had made it possible to build the canal and increase agricultural production, did not prevent questioning of the manner in which the irrigation system was managed. The figures responsible for this management – the House of Híjar and the royal judges – had adopted a persuasive language of common interests, as well as falling back on technical criteria regarding the use of water and agricultural land. However, the problems of the canal were no longer framed purely in economic or technical terms, but were addressed on two different levels: on one hand, in the light of the effects of political change, and on the other, in view of internal transformations in the operation of the irrigation system.

As we have seen, the initial implementation of the canal scheme under the absolute monarchy had been based upon two essentially political features that proved to be highly controversial. One was the Duke’s project in itself, in which he risked his investment in exchange for the Crown’s support, and thus supposedly ensured himself a high volume of revenue for the future. The second, surrounding element was the hierarchical conception of the public sphere, which enabled the Duke to present himself as a patriotic spokesperson for the common good of all, relegating other social sectors in the region (such as the more modest irrigators of the old part of the canal) to minor roles.

However, when the process of liberal revolution gained momentum, after 1808, the fundamental principle became that of ‘national sovereignty’. This made debates on the common good of the homeland, and in such a significant field as the expansion of agriculture, accessible to much broader sectors of citizens, who, moreover, no longer felt automatically subordinate to aristocratic hierarchies. The national political community thus acquired the capacity to reconsider what had previously been presented as indisputably beneficial. Hence, in the new liberal society, the Duke of Híjar lost the earlier underpinning he had derived from aristocratic hierarchy and the absolutist monarchy. Moreover, although the liberal order prioritised private ownership among its principles, and did in fact recognise the Duke’s ownership of the canal, he was unable to prevent questioning, at a local level, of his exercise of his rights of ownership. At the grassroots level of local society, local liberals and the form of liberalism they adopted gained the ability to define, with a fair degree of autonomy, the rights they regarded as legitimate. This would be deadly for the figure of a great magnate, and his efforts to act as the guardian of regional society and its primary mediator with central authority. In his place the new national state found its own bases of support in local society, reshaped by the effects of liberal policy; in this case, the state found its social support in the world of new property owners and landholders who had benefited most recently from the expansion of irrigation.

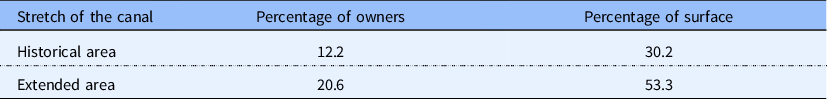

Table 2 shows us that, in the area that benefited from the Duke’s initiative, there was a preponderance of urban-based landowners from nearby towns. By involving them in the scheme he had ensured he had influential allies in the battle to exploit the waters of the River Júcar, against the opposition of the older users of the canal. However, once the supply was guaranteed, the House of Híjar found itself faced with powerful opponents when it came to negotiating the conditions and reciprocal compensations for the service.

Table 2. Urban landowners in the Acequia Real del Júcar (1853)

Note: The figures are weighted averages from three towns in each section (Alberic, Alzira and Algemesí for the historic stretch; Sollana, Silla and Albal-Beniparrell for the extended stretch).

Source: Archives of Acequia Real del Júcar, village records for irrigation payment.

The Duke’s problems began when anti-seigneurial resistance erupted in spectacular fashion with the disturbances of 1801 in the part of the Valencian region that included the Híjar estates.Footnote 25 Non-payment of irrigation fees became customary, as they were equated with the odious seigneurial stipends, rejection of which had become generalised throughout the region. In this situation, the House of Híjar had to appeal to the courts to oblige the new liberal town councils to force irrigators to pay their fees. The investment that had been expected to increase the Duchy’s revenues consequently became a threat to the future of the Ducal House. Moreover, the debt taken on by the Híjars since the construction of the canal became increasingly costly in itself: the forms of credit that had predominated under the old regime, such as redeemable perpetual loans, which had been used by the House of Híjar, were replaced by a new credit market with far more demanding conditions.Footnote 26

From 1811 onwards, following the disappearance of seigneurial jurisdictions, the Duchy was involved in lengthy litigation in many of its possessions in Spain – around 150 cases – resulting from different local authorities’ varying interpretations of the decrees for their abolition.Footnote 27 Within a few decades, the project for the modernisation and further ascent of the House of Híjar had been abandoned, and this collapse dragged the title’s status down with it.

In addition to these problems resulting from political change, serious tensions were also generated by the internal organisation of the irrigation system. It should be remembered that the new canal built by the ninth Duke was the continuation of another that had existed since the thirteenth century (see Figure 1). Consequently both formed a single irrigation system. Since the new construction began, this irrigation system had been administered in an authoritarian manner, without respect for the traditional autonomy of the previous users, by judges appointed by the Crown. Hence, in the new context of the liberal state, when these judges disappeared, it was necessary to redefine the manner in which the canal as a whole was to be managed. The Duchy of Híjar continued to be the owner of the second section of the canal, with the (theoretical) right to charge a veintena for the water supplied. However, the water users who depended on this supply set out to organise themselves independently of the canal owner. These irrigators had increased their production capacity, at a time when the reduction in ducal authority enabled them to extend the irrigated area beyond anyone’s control. For their part, the users of the old section were now attempting to recover, through the liberal institutions, the water management powers that had been nullified by the absolute monarchy. These conflicting and opposing positions could not ensure a unified management of the canal as a whole, one that would be capable of minimising conflicts and permit efficient use of the water. New conflicts then arose, while the liberal state set out to define its own new policy on water.

The abolition of seigneurial rights in 1811 included those affecting water management. Subsequently, the actions of the liberal state regarding irrigation were based on criteria that were defined in an improvised manner, until they were officially codified in the Ley de Aguas (‘Water Law’) of 1866.Footnote 28 These criteria were essentially the autonomy of irrigators to manage water, the priority of older over more recent irrigation, and the need for occasional intervention by the authorities to mediate in conflicts and facilitate agreements. These criteria, applied by the state, conditioned the struggle between the diverse sectors in dispute over the Acequia Real del Júcar.

Amid the upheavals brought by the conflicts of the first four decades of the nineteenth century, with the war against the French from 1808–14 and the civil war against the absolutists in 1833–40, and political instability that extended over an even longer period, the exercise of control over the waters in the canal had deteriorated. Moreover, a lack of knowledge of the situation and of effective allies in situ also hindered control from above.Footnote 29 The complex nature of irrigation in such a large area and the multitude of local circumstances that influenced the distribution of water were beyond the control of royal officials and the Dukes of Híjar, all of whom enjoyed scant legitimacy among many of the water users. On various occasions experts sent by the government determined that there had been excessive extension of irrigation. Everyone in the area was violating the terms of water concessions, and, given the poor state of maintenance of the system, this encouraged competition for water. After it was confirmed that ‘there is no concord’, nor effective regulatory law on the ground, armed officers were regularly sent to the canal to guarantee irrigation.

The first attempt to establish laws for the autonomous management of the Júcar canal, which would replace the old authority of the royal judges, took place in 1822, under the constitutional government of 1820–3. For the next two decades, however, until 1845, this search for new forms of management was conditioned by the political vagaries of the struggle between absolutism and liberalism.

During these years an intense public debate developed regarding the administration of the canal.Footnote 30 Some of those involved argued for a privileged position for the municipal councils (ayuntamientos) as the chief decision-making bodies on issues of irrigation in the area. Others, in contrast, held that the leading role should be taken by major landowners, independently of political institutions such as town councils. For its part, the House of Híjar hoped to retain the greatest influence possible over the management of the canal. In this dispute the liberal state, represented by the Civil Governor of the Province, sought the support of local allies. Such local associates would have a greater ability to obtain consensus through political institutions at community level in their respective areas, while at the same time acting as efficient agents of cooperation in tune with the government. This dispute was reflected in numerous press articles, directed at the general public and not just agricultural landholders.Footnote 31 This was a sign of changed times.

Agreement was impossible, and this paralysed the drafting of the Ordenanzas or ‘Ordinances’ that were to set down the specific norms for the management of irrigation. In the end, a definitive solution would only come under the new ‘Moderate’ (actually very conservative) government established in 1844. The new Gobernador Civil of Valencia, Francisco Carbonell, began negotiations in 1845, at the same time as he also intervened in many other chronic conflicts associated with irrigation in the province.Footnote 32 Carbonell negotiated with representatives of the municipalities involved and of the House of Híjar, and impressed on all of them, as a matter of priority, the need for the whole canal to be treated as a single unit, and for equal rights to be given to all its beneficiaries.

This was reflected in the new Ordinances, which established the definitive organisational structure of the Acequía Real del Júcar for the rest of the nineteenth century and, with few changes, into the twentieth.Footnote 33 It established two different areas of authority. A newly created body, the Junta General or ‘General Assembly’, with equitable representation of all the communities that used water from the canal, would have authority over the main canal, but not the branch canals. It was also charged with coordinating the irrigation system as a whole, appointing employees, and handling all negotiations with government bodies and with other canal systems that drew water from the same River Júcar (and therefore competed for its water). Meanwhile, the distribution of water in the branch canals and between individual irrigators through field channels, and all other aspects of management at a local level, such as maintenance work or the levying of charges, were to be managed through cooperation between the municipal councils and the major landowners.Footnote 34 An unsuccessful request was made that only landowners, and not the ayuntamientos, should be allowed to elect representatives to the Junta General.Footnote 35 However, even under a government that proclaimed its conservative intentions and its links to major propertied interests, the political participation of local residents prevailed over attempts to restrict water management to large landholders. Simultaneously, the authority of the Duke was limited to the fragment of the main canal of which he was the owner, but not its branch canals.Footnote 36 In addition, above the Duke there was now the General Assembly, creating a situation very different from the one envisaged under the absolute monarchy, when the Duke and the royal judges had held exclusive powers over significant decisions.

The formula finally arrived at reveals the social foundations of the new equilibrium achieved under the liberal state. Of the twenty-five representatives in the Junta General, nineteen would be elected by the towns, from an electoral college formed by municipal councillors and an equal number of large landowners. The House of Híjar would appoint four, the Crown one, and the Civil Governor, who could preside over its meetings, another.Footnote 37

As soon as the Ordinances were approved in 1845, the twelfth Duke of Híjar, who held the title from 1818–63, attempted to challenge them, on this occasion with the support of the landowners along his section of the canal. They argued that agriculture had to be regarded as an economic activity, and so a matter that should be considered apart from political interference by civil or community institutions. The water of the canal, they claimed, unsuccessfully

corresponds to the irrigating landowners and to the Right Honourable Duke of Híjar … Any foreign element [that one may attempt] to introduce should be considered inappropriate and detrimental to irrigators. The municipal corporations are not normally formed of the latter, but [instead] there are artisans and teachers of different sciences, and in most towns … they are simply local residents or leaseholders, who have no direct interest in anything related to the canal.Footnote 38

These complaints were not heeded, however, and the new institutional structure would operate from 1845 onwards, though not without conflict or adjustments, as we shall see.

The impossibility to adapt for the new canal’s first creators: the bankruptcy of the House of Híjar

The creation of new ordinances and administrative organs for the Acequia Real del Júcar coincided with the conclusion of the liberal revolution in Spain, around 1845. The new phase of development of the liberal stateFootnote 39 that began in the middle of the century, combining oligarchic politics and an administration inspired by French centralism, would appear to have favoured the consolidation of the rights of the Duke of Híjar. The elitist criteria that predominated under this conservative liberal monarchy facilitated the Duke’s representations to government. One might have thought that his social capital and resources would then finally obtain for him a position of undisputed influence, and that he would finally be recognised as an advocate of economic progress. However, quite to the contrary, this new phase would see the definitive dismantling of the Híjars’ position in the irrigation system.

The new institutional framework approved in 1845 actually rendered the presence of the House of Híjar in the management of the canal more acceptable to its other users, because it also guaranteed that it would be impossible to reverse the changes that had thwarted his claims. The liberal state, though oligarchic and formally centralist, effectively offered a guarantee that irrigation would be regulated locally, in line with the new criteria previously outlined. The state’s capacity to regulate matters in this fashion was strengthened by the new prominence given to its technical departments. Their role differed from that of the local agents that had been accorded powers under the absolute monarchy, in a vaguely articulated, personalistic manner, as an ‘outsourcing of functions’. The House of Híjar had tried to reassert its role as a privileged interlocutor with the monarchy, through its control over irrigation. In the new situation, however, this control was diluted within new institutions that represented the water users and the municipalities, and were subject to regulation by state officials.

Irrigation was now regarded as a matter of public interest, and central state intervention was based on technical criteria and a recognition of the organisational autonomy of water users, as a principle that needed to be respected. Hence, the re-establishment of the rights claimed by Híjar was not a viable option. There can be no doubt that the political regime established at this time was oligarchic in nature. However, this characteristic was not followed through indiscriminately, with a monolithic logic. In matters such as irrigation in Valencia, one can see evidence of the pluralist foundations of the regime, and the restrictions the liberal system placed upon the use of power.

In the mid-nineteenth century the administration of the canal was also affected by two major constituent features of the state. In first place, the profound transformations brought by liberalism sought to bring about a decisive stimulus to agricultural production, since it was considered necessary to move beyond the obsolete demographic and economic structure of the Spain of the old regime.Footnote 40 In the Valencian countryside, this stimulus was given material expression in the extension of irrigated land, which increased the productive capacity of local agriculture and the possibility of it meeting the needs of both local and more distant markets that would open up in a Europe in the midst of industrialisation.Footnote 41 The region would soon become the main supplier of citrus fruits to Great Britain, and also increased its exports of vegetables and rice. All these crops required irrigation. Here was the motor of economic transformation, but consolidation of this economic progress required the adequate regulation of irrigation systems, such as the Acequia Real del Júcar, to minimise conflict and guarantee water supply.

Secondly, however, the governments of the era could not by themselves guarantee the achievement of these objectives. It was necessary also to call upon the local powers, especially the municipalities, upon which the legal centralism of the state rested. The limited development of public administration and statistical services at this time made it difficult to control the use of water by thousands of irrigators in a very large irrigation system such as the Acequia Real del Júcar. Among other problems, without the cooperation of the local authorities it was very difficult to calculate and determine the surface that was actually irrigated.Footnote 42 The total area of irrigated land had grown considerably during the decades of conflicts and crises of authority that accompanied the several phases of the liberal revolution. Consequently, there was a need to establish and measure this area, and identify the numerous irrigators that been drawing off water without authorisation. The proliferation of illegal irrigators had been a central factor in attaining the new levels of production, but at the same time they threatened the correct functioning of the system. In addition, their growth also damaged the interests of the House of Híjar, which could not collect fees from land that had been irrigated illegally. However, a lack of cooperation from the municipalities prevented the completion of a reliable record of the entire area that had actually been irrigated.Footnote 43

While many irrigators were by this time effectively free from all statistical checks, for his part the twelfth Duke virtually stopped receiving the veintena to which he was entitled as owner of the new section of the canal. In the 1840s non-payment of fees accumulated, reaching extremely high levels. The Duke unsuccessfully submitted his complaints to the Gobernador Civil, who could only remind municipalities of their obligation to collaborate in registering irrigators and the collection of fees. However, the lack of cooperation by municipalities in facilitating the identification of non-payers continued, and only added to the shortfall in the aristocrat’s revenues.Footnote 44

These practices were further encouraged by an unfavourable mood towards the Duke and his House among local public opinion.Footnote 45 In 1844 the prestigious Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País, a private association promoting agricultural development that represented the region’s landed elites, published a translation of a book by the French agronomist François Jaubert de Passa on irrigation in Spain. Combined with his scientific prestige as an impartial student of economics, his defence of the customary rights to irrigation of smaller landowners was widely accepted by local opinion. This was accompanied by an explicit condemnation of the role played by Híjar, whom Jaubert regarded as more of a speculator than a benefactor.Footnote 46

Consequently, the prominent position of the House of Híjar found itself under siege from the new leaders of agricultural development in the region – landholders who had benefited from the socio-economic measures brought by the liberal revolution and the expansion of irrigation. This loss of social support eroded Híjar’s fortune, as also happened with other aristocratic houses in the nineteenth century.Footnote 47 Combined with a major reduction in income and the impossibility of meeting his debts, this led to an irreversible loss of assets, which affected the whole estate of the Ducal House, in and outside Spain. Sales of properties had begun in 1814, and did not cease. The Duke sold off his assets in Sollana, the town where the canal project had begun, all his property and rights in Roussillon in southern France and on the island of Sardinia, a palace in Zaragoza, and buildings and land in Galicia and Andalusia. Among the purchasers were administrators and leaseholders to whom the family was indebted, and who often formed part of the newly flourishing commercial classes.

Upon the twelfth Duke’s death in 1863 this insolvency reached its nadir with the symbolic act of the sale of his Madrid palace, including an important art collection, all of which became the property of members of the bourgeoisie of the day. Merely symbolic capital was a precarious means of sustaining the status of an aristocratic line that had still been in its pomp just fifty years earlier.

This decline had continued despite attempts at recovery. In 1841 the twelfth Duke had employed Benito del Collado as his accountant-general. He was a trained civil servant, from the new state administration.Footnote 48 This was a common practice, as the aristocracy turned for help to professionals in the service of the state.Footnote 49 Choosing a professional of this kind as one’s administrator appeared to be one way of theoretically ensuring the state’s backing.

Del Collado attributed the decline of the Híjar estates to two factors: political changes, which since 1808 had stripped the noble house of its rights and privileges, and a high level of indebtedness, generated by the construction of the canal.Footnote 50 The administration of the Duke’s possessions, which was in a chaotic state, was then reorganised and rationalised, but the sale of assets remained unavoidable. Legal intervention became inevitable with the liquidation of the Híjar fortune and inheritance in 1863, which confirmed the definitive bankruptcy of the Ducal House.

It proved impossible for the Duchy of Híjar to readapt its inherited status to the forms of activity fostered by bourgeois society, at a point in time that was otherwise favourable to the relaunching of the economy. In the late 1850s, the European economy entered a phase of positive growth that had a noticeable impact upon exports from the irrigated areas of Valencia. However, the administrators employed to reorganise the Duke’s affairs did not propose improvements in the field of production. The lack of experience in a rentier family, and the appointment of administrators who lacked practical knowledge of agriculture must have excluded that possibility. In matters concerning the canal, moreover, there was the added difficulty of establishing alliances on a local scale to counter the decline of Ducal influence in the new institutions created in 1845.

Nor did the highest echelons of the liberal state save the Dukes’ House from collapse. The influence of the Crown extended only into extremely limited circles, and the symbolic capital of the Híjar family was insufficient. In 1865, the new holder of the title, the twelfth Duke’s grandson, the fourteenth Duke, sold his interests in the canal for 2.1 million reales to Jorge Díez Martínez, a Seville lawyer with very good connections with governments of the period. The price he paid was very much lower than the sum that had been invested by the Híjars at the end of the eighteenth century, of around eight million reales.Footnote 51 Nevertheless, the canal continued to be unprofitable for the new buyer and his successors, until in 1916 they sold the rights to the irrigators themselves, the users of the water, who would manage it collectively, as was usual in irrigation in the Mediterranean region.

Conclusions

Spain’s absolute monarchy was effective, in the case studied here, in promoting irrigation in the face of local opposition. However, this ‘effectiveness’ did not equate to the beginnings of a ‘construction of the state’. It involved, first of all, a connection between the central authority of the Crown and a newly active local magnate, with a proposal that also coincided with the interests of the royal treasury; secondly, a notably risky investment by the Duke of Híjar, supported by an innovative interpretation of the idea of ‘government as dispenser of justice’; and, finally, the subordination of local social forces, both middle-income agriculturalists and urban speculators. Paradoxically, however, the size and influence of these social groups would be strengthened as a result of the expansion of irrigation.

The later liberal state did achieve a balance. Its oligarchic character was not a simple continuation of the old regime. The power of this state legitimised a certain level of consensus based on the principal social forces in play, not simply as expressions of economic and agricultural power, but through their positions in local institutions of political power. In all these phenomena, political cultures and public opinion also played a fundamental role. In addition, the consolidation of the new liberal order, by effectively confirming an extension of the area under irrigation much greater than had previously been anticipated, permitted a decisive growth in the growing of rice, which would be of fundamental importance for the Spanish economy in the rest of the nineteenth century.

This new order dismantled the logic upon which the sponsors of the schemes of absolutist reform had relied. In the new liberal order, consolidated in the mid-nineteenth century, a public arena was created that was no longer subordinate to the holders of noble titles as representatives of the common good, and the new power of the sovereign state was not reduced to governing solely by sustaining established rights, as the absolute monarchy had tried to do. The planned area of production by irrigation was far exceeded; the royal court’s support for the Duke was rendered irrelevant by the formation of a nation-state based on local political arenas, and open to influences stemming from social change and liberal politicisation. In a public sphere that was being occupied by the middle classes, the case of the House of Híjar is evidence of how much the aristocracy could be sidelined in the promotion of economic growth, and in terms of public prominence.

Under the liberal state, the reality of the growth in production that had been generated over decades in the area by then under irrigation was acknowledged. The procedures that were introduced to manage this expansion were not based on a vertical imposition by the central state. Civil Governors employed their authority to encourage transactions between those social forces that had consolidated their position, and resolve cases in which agreement could not be reached otherwise. The House of Híjar, owner of part of the canal, now had to negotiate agreements within new institutions over which it had no control. They could even be openly hostile to the Duke, even if they shared the overall conservatism of the government. This led to an asymmetrical regulation of different aspects of the scheme, which attributed important powers to a local institution that was conceived simultaneously as a circle of producer interests and as a collective political representation of individuals of diverse socio-economic status. Thus, in the ‘era of owners’, liberal politics revealed itself to be a dimension in its own right, capable of introducing a range of considerations that extended far more than simply ‘economic’ criteria into the handling of a question as significant for society as irrigation in Mediterranean Spain.Footnote 52 Consequently, the construction of the liberal state did not establish a single, unequivocal means for the transmission of the interests of property.

Acknowledgements

The authors form part of the Research Project PGC2018-100017-B-I00. They wish to thank Pablo Cervera and Samuel Garrido for their comments, Carles Sanchis Ibor for preparing the map, and the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their comments.