In her seminal essay, “The Particular and the General in Lyric Poetry,” published in 1981, Lidiia Ginzburg proposes two main thrusts of poetic movement: what she terms “deductive” and “inductive.” Ginzburg writes:

The lyrical deduction and induction correspond to two great aesthetic forces—that of symbolic generalizing and that of detailing, which only the artistic perception of the world is capable of producing . . . Induction is a corollary to the concrete, opposed in art to the generally ideal—a picture of the ideal world depicted in the language of pre-established values and meanings . . . The lyrical induction demands concreteness and individuation . . .”Footnote 1

Within this framework, deductive lines up with the general, collective, and the abstract, whereas inductive stands for the individual, the concrete, and the experiential. The most original and lasting of Russian poetry that responded to and commented on World War II already during the event and in its aftermath, shuttles between the deductive and inductive poles. Its shift of focus from the collective and impersonal to the factual and individual resists Stalinist aesthetics, a perverse outgrowth of the deductive classics and epos with their “symbolic generalizing” and “pre-established values.” Located in the underground and official Soviet spheres, this poetry provides parallels for today when the question of whether and how literature and poetry, in particular, can bear witness and respond to the ongoing atrocities and destruction has again become number one on the moral and intellectual agenda for many. This short essay is an attempt to reintroduce and reread this terse verse with these parallels in mind, focusing on two of its premier poets—Boris Slutskii (1919–1986) and Ian Satunovskii (1913–1982). Both cross the taboo of the war—individualize the enemy—in remarkably similar and dissimilar ways that account for their different life choices and yet intensely close personal and aesthetic kinship.

Boris Slutskii is a crucial component of the deductive/inductive nexus and perhaps its most curious and still misunderstood practitioner precisely because of his positioning at the intersection of published (and hence by definition censored and self-censored) and unpublished realms that—as students of Soviet culture begin to increasingly understand—fed off each other and could not be easily disentangled. Slutskii is also vital not only because of his dwelling on the war as its participant, witness, and commentator, but because he was a poet-thinker intent on using his verse to formulate a philosophy of history, both immediate and far removed. He is, as I described it at length elsewhere earlier, a hermeneutic poet who treats his era as a biblical cluster.Footnote 2 In other words, Slutskii both uses the Hebrew Bible to comprehend contemporaneity and offers his own lyrical corpus as a scripture, an addendum to and a competitor with the original holy writ. This pervasive and complex engagement with sacred textual traditions and upholding the collective canon conflicts and co-exists with Slutskii's insistence on the concrete and the particular, leading to a paradox at the heart of his poetics. The tension between the collective and the experiential/particular or phenomenological—or even their overcoming—is at the core of his oeuvre, resulting in the daring confluence of deductive and inductive thinking.

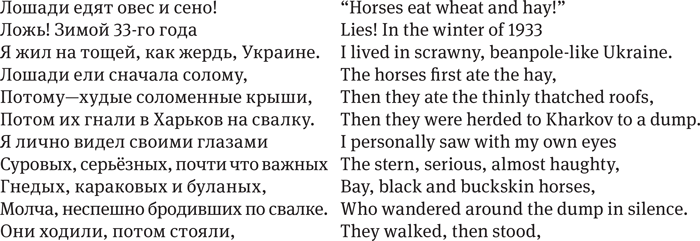

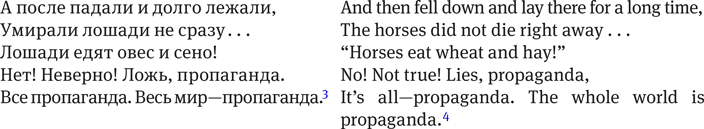

A case in point is the poem “Govorit Foma” (Thomas Speaks), written most likely in the early- or mid-1950s (and hence possibly predating Stalin's death), and published for the first time in 1989. Taking on the persona of the doubting Thomas from the Gospel of John, who refused to believe that the resurrected Christ had appeared to the apostles until he could see and feel Jesus's wounds, Slutskii offers a phenomenological manifesto of supreme individualism that defies not merely any ideology and its propaganda machinery, but the world as such. The poem reads:

The poem's terrain is one of “multidirectional memory” in its fusion of memories of the war and Holodomor in Ukraine.Footnote 5 Its sense of time is deceiving. On the one hand, it is momentary and immediate and thus, fleeting—“Today I believe nothing”—but, on the other, it extends to the speaker's worldview in its entirety—“It's all propaganda. The whole world is propaganda.” The poem is emblematic of Slutskii's poetics in its conversational mode—the reader here is an interlocutor who is being told a story. It is also an “anecdote in the vein of Herodotus, without lies, but artistically framed,” to borrow Slutskii's characterization of his own Notes about the War, his only extended prose text.Footnote 6 In an essay, “After the War,” them, he described his memoiristic method as objectivist, writing, “A memoirist must be passionate and unjust—in order not to tumble down into objectivism. I am, by nature, not too passionate and relatively just. I roll toward objectivism with pleasure.”Footnote 7 This deliberate objectivism or truthfulness is manifest in the poem as well, meaning that the event being described or recalled is presented from the other's angle, indeed not unlike in Herodotus's Histories. The personal is undercut by providing the enemy's voice, which causes the transformation of the personal. The poem becomes an elegiac wish for the childhood that never was, necessary for the remaking or rather unmaking of the self in its interaction with the ostensibly objective world (Volga) that can come into being only through the poet's stubborn touch.

Equally emblematic is Slutskii's employment of his favorite imagery of horses, which blends the animalistic with the human.Footnote 8 The sober and seemingly detached depiction of the horses is both parabolic and deeply detailed. The poet draws a lesson from their horror and yet refuses to turn them into icons. The statements, “Horses eat wheat and hay” and “the Volga flows into the Caspian sea,” allude to Anton Chekhov's short story, Uchitel΄ slovesnosti (The Teacher of Literature), where Ippolit Ippolitych, a teacher of history and geography, mutters in his near-death delirium, “the Volga flows into the Caspian sea . . . Horses eat wheat and hay.”Footnote 9 These truisms lose all their basic and factual validity in the face of the catastrophic reality of the Holodomor, experienced and witnessed by the speaker. Slutskii turns the general and the platitudinous into a picture that is devastatingly concrete and at the same time predicated on a new universal rule of radical and absolute doubt which, however, is still painfully personal and denies the possibility of abstraction. His thinking ultimately transcends the particular/universal dichotomy.

The portrayal of Germans is characteristic of Slutskii's method of questioning the inductive and the deductive as well. On the one hand, they are presented as individuals, deserving of dignity, which recalls his poem, “Nemetskie poteri” (German Losses), in whose last lines he states: “What do I care?/ Did I christen the Germans’ children? / Their losses do not affect me in a bit!/ / All of them I do not pity! / I pity only one: / that one / who played a waltz/ on his harmonica.”Footnote 10 On the other hand, Slutskii goes an astounding step further: he makes the Germans’ pronouncement—“It's all propaganda. The whole world is propaganda”—his own, the poem's coda and the cornerstone of his vision. In response to them he puts an equal sign between the Nazi and Soviet systems of belief and makes it by the end his all-encompassing principle of negation.

Part of this negation is the dread at judging the other, even when that other is the existential enemy. In a poem, written around the same time as “Thomas Speaks,” the speaker confesses, “I sat in judgment over people and know for sure / that it is not at all difficult to judge anyone, / only later you might feel sick to your stomach, / if you'll carelessly remember certain details.”Footnote 11 The poet wants to retreat from history and become a mere “school teacher” or a “bookseller” to avoid this messiness.Footnote 12 Ian Satunovskii, an attentive reader and admirer of Slutskii and a fellow veteran, fulfilled this wish by, first, avoiding almost always participating in the official literary process and, second, creating a persona of obyvatel΄ (common man) who comments, as if in passing, on the daily routine, including the bloody routine of the war.Footnote 13

Like Slutskii, Satunovskii too centers on the individual, including at times the enemy. The effect on the reader of his poems’ calm, matter of fact tone is one of dismay or even emptiness, making the hermeneutic task of decoding their meaning almost futile. Satunovskii's language can be viewed as survival speech, but it is a survival that, despite the subject's deep unvoiced pain, nearly relativizes the horror and its aftermath and thus complicates the notion of remembrance. While Slutskii aims for completeness even at the moment of resolute personal denial, Satunovskii opts for the fragmentary and the non-generalizing, resisting any total interpretation of the event or attributing to the individual any special value. As proposed by Ilya Kukulin, Satunovskii posits his “daily personal reflection as a micro-historic event.”Footnote 14 Indeed, he operates with facts—an objective reality—but constructs no macrosystem on their basis. He is committed to the inductive at its most fundamental.

A number of Satunovskii's poems, or rather fragments, from 1944 and 45 when he was in occupied Germany, describe coming in contact with Germans. In fragment # “33,” he writes,

Evoking the call to hate the Nazis, made by Ilya Ehrenburg and others at the beginning of the war, Satunovskii draws a distinction between collective sloganeering, however justified and noble it may be in this case, and the power of personal encounter, embodied in the word play of same root verbs “nenavidel/uvidel”—“hated/saw.” By repeating “not,” as if stuttering, “I did not not hate them,” Satunovskii confuses the reader and relays his own indecisiveness. He did hate them, but not really. By describing and remembering the mocking of German POWs by the Red Army, Satunovskii humanizes them and makes worthy of if not compassion, then at least pity, but stops short of anything like Slutskii's discovery of the axiom of universal propaganda.Footnote 16

In fragment # “45,” there is an encounter with the individual German:

Here there's a potential of a dialogue in the Buberian or Levinasian sense: in seeing and recognizing the other, a German POW, an ironic stand-in for the presumed greatness of German culture, which becomes completely thwarted.Footnote 18 The moment of blindness transforms into one of sight and mutual contemplation to abruptly result in nothingness. The line “the moment stops” seems to allude to Goethe's Faust, but it carries no hermeneutic weight. Again the similarities and contrasts with Slutskii are unmistakable. Both employ the same language, redolent of the war realities, but if Slutskii's interrogation turns into an exchange of insight, Satunovskii refuses to impregnate the silence with meaning.

The enemy factor is, however, key here. It is paradoxically the former military prosecutor and ideological officer Slutskii who makes the foe a like-minded partner. A hardly ever ideological Satunovskii cannot bring himself to do that, which speaks to the emotional force of his seemingly indifferent verse. His lyrical voice shifts into a much more curative tenor when he remembers the individuals like himself—Soviet Jews of his generation—those who survived and those who did not either at the front or in the massacre ravines. Their still fragmentary yet deeply detailed portraits rescue them from oblivion. Consider fragment “634,” composed in 1969:

Like in “Thomas Speaks,” the memorial terrain here is also multidirectional, bringing together the war, Holocaust, and Gulag strands. While Ziozka (Satunovskii's usage of nicknames invokes a special Soviet Jewish atmosphere) manages to survive the Nazi hell, he cannot avoid being sent to a Soviet camp in Siberia, where he stays after being released. He settles in Norilsk “forever” and thus, at least in the realm of poetic language, lives forever.

One of the most poignant of such elegiac fragments is # “55,” which again imbues a recollection with an acutely haunting and humanizing sentiment, bringing together the fate of a Russian and a Jew in the moment of destruction:

Сашка Попов, перед самой войной окончивший

Госуниверситет, и как раз 22-го июня

зарегистрировавшийся с Люсей Лапидус—о ком же ещё

мне вспоминать, как не о тебе? Стою ли

я—возле нашего общежития—

представляю то, прежнее, время.

В парк захожу—сколько раз мы бывали с тобой на Днепре!

Еду на Чéчелевку, и вижу—

в толпе обречённых евреев

об руку с Люськой

ты, русский!—

идёшь на расстрел,

Сашка Попов . . . Footnote 20

Sashka Popov, who graduated right on the eve of the war

from a state university, and married Liusia Lapidus

right on June 22nd—who else

can I remember, if not you? Whenever I

stand near our dorm

I remember that past.

Whenever I come to the park—how many times we came here to see the Dnepr!

Whenever I drive to Checheliovka, I see

you in the crowd of condemned Jews,

holding Liusia's arm,

you, a Russian!–

are marched to be shot,

Sashka Popov . . .

For Satunovskii, the ground carries the omnipresence of the war and the Holocaust. Checheliovka is one of central historic neighborhoods of Dnipro (the formerly called Dnepropetrovsk), which had a significant Jewish presence. In October 1941, the Jews of the city were rounded up and marched through the center of the city to be massacred in a nearby ravine. Significantly, the poem is written in 1946 in Dnepropetrovsk. Like in Claude Lanzmann's Shoah (1985), a return to the place of origin brings the buried memories alive and turns the recent past into the never-ending present. The ellipsis at the end simultaneously perpetuates this work of memory and renders it unbearably painful and indeterminate.

The place, often it is his native Kharkiv, is of paramount importance for Slutskii as well, both as a memory trigger and as a bearer of meaning, as we saw in the recollection of Holodomor in “Thomas Speaks.” It is fitting to conclude this essay with his poem, likely written in the immediate aftermath of the war and published once in 1966, that personifies Ukraine and locates in it the source of blessing:

Ultimately, what links Slutskii and Satunovskii together is their profound non-dogmatism, embodied in the seemingly opposed gestures of Satunovskii's lowering of poetry to aphoristic fragments, which resists imposing meaning on the event, and Slutskii's thirst for completeness, which attempts to understand the historical horror and arrive at some all-encompassing principle. Both shun the collective in favor of the particular and cling to concrete memories and the sites that contain them. It is in this non-dogmatism that their main value lies for the reader in this moment of devastating crisis for Russian literature and culture, the moment when Ukraine again “is deciding much.”