INTRODUCTION

There has been much research on how article-less first language (L1) learners of English, such as Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Russian, acquire the English definite article (Ionin, Ko, & Wexler, Reference Ionin, Ko and Wexler2004; Ko, Ionin, & Wexler, Reference Ko, Ionin and Wexler2010; Snape, Reference Snape2008, Reference Snape, Snape, Leung and Sharwood Smith2009; Trenkic, Reference Trenkic2008; Tuniyan & Slabakova, Reference Tuniyan and Slabakova2017). Studies have shown that articles present a tremendous challenge to second language (L2) learners from article-less L1s. Among them, by employing a feature-based approachFootnote 1 (Lardiere, Reference Lardiere2009), Cho (Reference Cho2017) examines L1-Korean L2-English speakers’ acquisition of English definiteness using an acceptability judgment task (AJT). Korean, an article-less language, has a demonstrative ku “that” which is different from the English definite article the in that ku encodes only [+anaphoric] whereas the encodes [+/-anaphoric] (both have the value [+definite]). This feature mismatch between Korean ku and English the is expected to influence Korean learners’ acquisition of the English definite article, leading Korean speakers to be less accurate in interpreting articles in the nonanaphoric condition. This prediction is confirmed by intermediate learners in that they correctly rated felicitous noun phrases (NPs) higher than that of infelicitous NPs only in the anaphoric definite conditions, not in the nonanaphoric definite condition. Advanced learners accepted the use of the in all definite conditions, indicating that unlike intermediate learners, advanced learners understood that the appears in both anaphoric and nonanaphoric conditions, adding the [-anaphoric] feature. However, advanced learners rated unacceptable indefinite NPs as high as that of acceptable definite NPs in the anaphoric bridging and the nonanaphoric conditions, differing from English speakers. Cho argues the source of the discrepancy to be advanced learners’ lack of the ability to presuppose the existence of the mentioned and (especially) the unmentioned information in the discourse triggered by articles (presuppositional inferences). Therefore, Cho proposes one more step beyond feature reassembly—presupposition accommodation.

The present study extends the inquiry of L2 learners’ acquisition of English definiteness to another article-less language, Mandarin Chinese, and more importantly, moves beyond from the feature approach and discusses the acquisition data from an interface perspective. Chinese has a demonstrative determiner sharing the identical feature combination as the and, thus, reassembling features is unnecessary (in contrast to Cho’s study). What is involved in Chinese speakers’ acquisition of English definiteness is the acquisition at the semantics-pragmatics interface, that is, the semantic knowledge of definiteness and uniqueness interacts with pragmatic inferences. It requires learners’ additional pragmatic knowledge and willingness to associate a definite noun phrase with a complicated and arbitrary entity that licenses the presence of the definite noun phrase.

DEFINITE DESCRIPTIONS IN ENGLISH

UNIQUENESS AND FAMILIARITY THEORIES

Essential concepts regarding how definite descriptions account for meaning of utterance have been addressed extensively in the previous literature. For instance, identifiability, uniqueness, familiarity, and anaphoricity (see Lyons Reference Lyons1999 for a detailed discussion on each concept). Among them, there are two main theories, namely uniqueness theory and familiarity theory (Lyons, Reference Lyons1999; Roberts, Reference Roberts2003; Schwarz, Reference Schwarz2013).

The uniqueness theory argues that the definite article implies one unique entity that can satisfy the definite description. Consider (1–3):

(1) Put these clean towels in the bathroom please.

(2) The moon was very bright last night.

(Lyons, Reference Lyons1999, p. 3)

(3) The Queen of England had a bad year in 1993.

(Roberts, Reference Roberts2003, p. 290)

The three examples show situational uniqueness of the. Example (1) the bathroom denotes a physical and tangible place that only has one bathroom. The situations in (2) and (3) are more likely to come from speakers’ general knowledge: Most would agree that there is only one moon associated with the earth and only one queen in England.

According to the second theory, familiarity theory, definite descriptions refer to already shared information about a referent between interlocutors (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins1978; Heim, Reference Heim1982). The common ground of shared information includes (a) linguistic discourse referents that interlocutors are familiar with and (b) presupposed referents of culturally or pragmatically shared experience and knowledge (Heim, Reference Heim1982; Stalnaker, Reference Stalnaker1974).

Cho (Reference Cho2017) summarizes three types of familiarity of the English definite article the as shown in (4–6). In (4), the definiteness of the cat in the second sentence is established through previous mention in the first sentence. Thus, the definite referent the cat is familiar and identifiable to interlocutors. Sentence (4) is also an example of anaphoricity, which is an essential notion of familiarity theory. The anaphor (or anaphoric NP) is the cat and it refers to the antecedent a cat.

(4) I saw a cat. I gave the cat some milk.

(Ionin, Ko, & Wexler, Reference Ionin, Ko and Wexler2004, p. 7)

In addition to previous mention, if the anaphoric NP and the antecedent NP are in close lexical relation, such as with synonyms, hypernyms, and so forth, the hearer is still able to identify the antecedent NP, as shown in (5). Even though a seat and the chair are different, the hearer can understand that the two NPs refer to the same entity based on the close lexical relation they share.

(5) Kerry broke a seat in her dining room. She repaired the chair with some tape.

(Cho, Reference Cho2017, p. 7)

The last type in familiarity theory involves implicit verbal antecedents. The implicit verbal antecedent can license a definite anaphoric NP because the definite NP closely associates with the event. For instance in (6), after reading the first sentence, we do not necessarily assume that the death of John is due to stabbing. However, the definite NP the knife requires us to accommodate the assumption that the knife was the murder weapon.

(6) John was murdered yesterday. The knife lay nearby.

(Roberts, Reference Roberts2003, p. 300)

It should be noted that examples (4–6) are all anaphoric. In short, anaphoricity of definiteness depends on an idea that the individual or entity is familiar or identifiable to the speaker and hearer through previous mention, close lexical relation, and implicit verbal antecedents. The next section discusses another important concept regarding definiteness—bridging.

BRIDGING

Bridging is a special and indirect case of anaphoric use. It means that the antecedent NP is not the referent of the definite NP, but they are in a salient thematic relationship. It also should be noted that the definite bridging entity is new in the discourse. It has never been introduced previously and is not part of other entities already introduced in the utterance (Charolles, Reference Charolles1999). In this article, I will focus on two types of bridging definiteness. The first type is anaphoric bridging, and the bridging definiteness is established through the salient relation between the verbal antecedent and the bridging NP. The second one is nonanaphoric bridging. The situational uniqueness together with world knowledge and pragmatic information can help interlocutors to interpret the definite NP correctly.

Example (6) illustrates the first type—anaphoric bridging. The knife in (6) has not been mentioned in the previous sentence. But the hearer understands that the knife refers back to the weapon that killed John. Cho (Reference Cho2017) states that to figure out this implied anaphoric relationship, it requires both semantic and pragmatic accommodation between the anchor (murder in 6) and the bridging definite NP (the knife in 6). The second type of bridging is nonanaphoric,Footnote 2 meaning the definiteness of the bridging definite NP is situationally unique and established through world knowledge and pragmatic information. For instance, in (7) there is no preceding noun that functions as the antecedent of the bride. However, the bride is still felicitous in that, based on world knowledge, the hearer knows that at a wedding, there should be one and only one bride.

(7) I’ve just been to a wedding. The bride wore blue.

(Lyons, Reference Lyons1999, p. 7)

In summary, this section summarizes four categories of English definite descriptions: Three of them are anaphoric by using (a) the same noun as the antecedent; (b) a different noun but in a close lexical relation, such as synonyms, hypernyms, and so forth; and (c) a noun being the direct object of a verb that is an implied antecedent (this category is also a bridging definiteness and labeled as anaphoric bridging). The last category, nonanaphoric bridging definite description, has no potential antecedent and definiteness is established through interlocutors’ pragmatic and world knowledge.

EXPRESSION OF DEFINITENESS OF THE MANDARIN CHINESE DEMONSTRATIVE DETERMINER NEI

Mandarin Chinese, a language without an article system, employs lexical, morphological, and syntactic methods to indicate definiteness or indefiniteness of noun phrases. Chen (Reference Chen2004) states that Chinese, lacking articles, uses demonstratives, possessives, and universal quantifiers. Only demonstratives, one of the lexical methods, are discussed in this study. Chinese has two demonstrative determiners: zhe “this” denotes proximity whereas nei Footnote 3 “that” denotes distance. The issue of whether it is zhe or nei that functions more like a definite article in Chinese or how far they have gone on the path of grammaticalization is beyond the discussion of this article. However, studies on the Chinese determiner nei demonstrate that nei extends its functionality toward a quasi-equivalent of a definite article, taking some functions or characteristics of the English definite article the (Huang, Reference Huang1999; Li & Thompson, Reference Li and Thompson1981; Lu, Reference Lu1990; Shi, Reference Shi1998).

First, Chinese nei can appear in situations in which the English definite article is used anaphorically, besides common uses of nei denoting spatial-deictic and contrastive meaning (Shi, Reference Shi1998). As (8) illustrates, nage can be interpreted as nage ge “that song” where ge “song” (the second ge in nage ge) has been left out and it refers to the song the speaker will sing up to the middle. Moreover, (8) is also an example of bridging and it resembles (6) in that both examples have a verbal antecedent (chang “sing” in 8 and murder in 6). The antecedent and the bridging definite NPs are in a salient thematic relation.

(8) B: na suoyi wo chang dao zhongjian … ranhou Liu laoshi zai

and so I sing till middle and Liu teacher again

zai chui koushao, ba nage changwan.

again blow whistle ba that finish singing.

“And so I sing up to the middle…and it is Teacher Liu’s turn to whistle the rest of the song.”

(adapted from Huang, Reference Huang1999, pp. 79–80)

Second, when used as a definite marker, Chinese demonstrative nei has less restriction compared with English demonstratives. That is to say, Chinese demonstratives are found in some situations in which English demonstratives are not allowed but the definite article is. Chen proposes four such situations and only the situation that is related to nei is presented here:

(9) BridgingFootnote 4

Ta mai le yi liang jiu che, na luntai dou mo ping le.

He buy PFV one CL old car that tire even wear flat CRS.Footnote 5

“He bought an old car. All the tires are worn out.”

(Chen, Reference Chen2004, p. 1153)

This example is essentially nonanaphoric because the definite NP tires is not previously mentioned and there is no antecedent to refer to. It is similar to (7) in that, from pragmatic and world knowledge, interlocutors know a car must have tires and na luntai “all the tires” in the second sentence refers to the “car” mentioned in the first sentence. (However, the plurality of the NP all the tires is not a concern in this article.) To illustrate a singular definite NP with nei, example (7) in Chinese is presented here as (10).

(10) Wo qu canjia le yi chang hunli. Nei(ge) xinniangzi chuan le lanse

I went participate PFV one CL wedding. That bride wore PFV blue

de hunsha.

DE wedding dress.

“I’ve just been to a wedding. The bride/*that bride wore blue.”

This example has a singular definite NP the bride in a nonanaphoric situation. It is preferred to use the in English because from our world knowledge we know that there is only one unique bride at a wedding. Contrasted with the bride, the demonstrative NP that bride is not felicitous in that there is no explicit antecedent or a salient referent or speakers’ demonstration. What is interesting here is that, according to my 16 Chinese informants, the appearance of the Chinese demonstrative nei is acceptable, although it may not be obligatory. Note that in Chinese, a bare NP is the default form. Bare NPs can be interpreted as definite or indefinite and, in some contexts, can also denote genericity. This is different from English where a bare countable NP is ungrammatical (e.g., *I ate apple). Therefore, the use of nei with a Chinese NP denoting definiteness is optional and does not affect grammaticality. However, after analyzing a large amount of conversational data, Shi (Reference Shi1998) argues that Chinese people tend to use nei NPs to increase salience whereas bare NPs remain neutral regarding referential salience. Example (10) illustrates that Chinese nei, unlike English that, which cannot appear in nonanaphoric contexts with no explicit antecedents, behaves more like the definite article the.

To sum up, this section’s discussion on the Chinese demonstrative determiner nei indicates that nei can be found in both anaphoric and nonanaphoric contexts. Therefore, Chinese demonstrative determiner nei has exactly the same feature combination as the English the with regard to: [+definite, +/-anaphoric].

RESEARCH AIMS OF THIS STUDY IN THE CONTEXT OF CHO (2017)

Replication studies play a very important role in scientific disciplines to test the robustness and generalizability of research findings (Porte, Reference Porte and Porter2012). Cho’s (2017) study is replicable in that the study is complete, providing a great number of details of the test design. I considered Cho’s study important to be replicated to achieve two research goals for a more precise understanding of article acquisition:

• Cho finds that the feature reassembly model cannot explain why advanced Korean speakers, after reassembling features, did not have nativelike ratings on the AJT and, therefore, proposes the necessity of presupposition accommodation (especially for the nonanaphoric condition). In acquiring the English definite article, although having the target feature set, Chinese speakers still face the same learning task to accommodate presuppositions at the semantics-pragmatics interface. One of the goals of the current study is to investigate if the ability to accommodate presuppositions of definiteness and uniqueness is automatically acquired for Chinese learners, even though feature reassembly is not required.

• By comparing L1-Korean speakers who need to reassemble features with L1-Chinese speakers who do not need to reassemble features, this study aims to explore if there is any difference in acquisition between the two L2 groups at the semantics-pragmatics interface.

As shown in Table 1, differing from Korean speakers in Cho (Reference Cho2017), Chinese speakers do not need to reassemble features. Therefore, Chinese participants, at least advanced speakers, are predicted to have equally accurate interpretations of both anaphoric and nonanaphoric English NPs, as native English speakers do. Intermediate Chinese speakers, given interpretation difficulties of the nonanaphoric condition at the semantics-pragmatics interface, are expected to experience challenges in this condition.

TABLE 1. Feature combinations of English the, Korean ku and Chinese nei

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

The participants in this study were 26 native English speakers and 53 L1-Chinese L2-English learners who were university students in the United States. The native English speakers’ data were from Cho (Reference Cho2017). All participants finished a paper-based AJT (35–45 minutes), a proficiency test (15 minutes), and a background questionnaire during one session. Questions in the background questionnaire collected participants’ information about gender, age, and years of studying English. The proficiency test was based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) containing 40 items with a maximum score of 40. Two levels of proficiency (intermediate and advanced) were determined on the basis of the proficiency scores. Note that the proficiency test and the intermediate/advanced categorizations (i.e., proficiency score range in Table 2) were the same as those used by Cho. The summary of participants’ information is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2. Participants’ background information and proficiency scores

METHODS AND DESIGN

The test design and all test items used in this study were identical with Cho (Reference Cho2017). The AJT contained 170 test items (72 targets, 18 controls, and 80 fillers) to test four conditions of definite NPs in Cho’s categorization, namely direct anaphoric definites (n = 18), taxonomic anaphoric definites (n = 18), anaphoric bridging definites (n = 18), and nonanaphoric bridging definites (n = 18). In each category, half the items were acceptable definite NPs (the + NP) and the other half were unacceptable indefinite NPs (a + NP). The reason why indefinite a + NP was included is because only testing acceptable uses of the cannot inform us whether second language learners distinguish the acceptable and unacceptable uses of the. It is possible that L2 learners have not acquired the understanding of when it is more appropriate to use the and, instead, they simply accept the + NP across the board.

The instructions on the AJT were based on a four-point scale with an option of “I don’t know.” Participants were asked to judge, in a pair of sentences, whether the second sentence was a good or felicitous continuation of the first sentence. An evaluation of 4 on the acceptability scale means that the second sentence is totally acceptable whereas an evaluation of 1 means totally unacceptable (3 = somewhat acceptable and 2 = somewhat unacceptable). When circling 1 or 2 or “I don’t know,” participants were encouraged to identify the source of the problem by either underlining words in the sentence or leaving a short comment.

Sentences (11–14) are four sample test items for each type of the condition. If Chinese participants have successfully acquired anaphoric and nonanaphoric English definite NPs, all (a) instances (acceptable use of the) were expected to receive higher evaluations than (b) instances (unacceptable use of a) in (11–14). For instance, in (11) a play appears in the first sentence and therefore, it licenses the use of the definite article the in the second sentence. Consequently, (11a) should be rated higher than (11b). In the taxonomic anaphoric definite context, the microwave refers to the antecedent an appliance in the first sentence and thus, (12a) is more acceptable than (12b). Similarly in (13), (13a) is more felicitous than (13b) in that being the direct object of the verb read in the first sentence, the novel in the second sentence refers back to the implied antecedent. Lastly in (14), the general knowledge that there is usually only one microwave in one’s kitchen licenses the appearance of the definite NP the microwave in (14a) and, thus, it should receive higher ratings than (14b).

(11) Direct anaphoric definite condition:

a. Timothy and Franny went to see a play last night. They discussed the play for an hour afterward.

b. Todd’s high school is showing a play this weekend. # Todd and his parents are going to see a play.

(12) Taxonomic anaphoric definite condition:

a. Nancy bought an appliance online. The post office delivered the microwave to her home.

b. Jerry has an appliance in his dorm room. # His roommate uses a microwave more than he does.

(13) Anaphoric bridging definite condition:

a. Hillary’s brother was reading in the bus this morning. He accidentally left the novel when he got off.

b. Jonathan read for three hours last night. # He found a novel very interesting.

(14) Nonanaphoric bridging definite condition:

a. Sandra is working in her kitchen. She cleaned the microwave first.

b. Andrea just walked into her kitchen. # She opened a microwave and put her dinner inside.

In target items, the use of the is predicted to be rated as felicitous and the use of a is infelicitous. The relationship between the/a and felicitous/infelicitous contexts was counterbalanced in the control items, that is, the use of a is acceptable whereas the use of the is unacceptable, as shown in example (15). Fillers serve as distractors. The acceptability of fillers is dependent on the semantic meaning of the two sentences, not related to the use of articles.

(15) Control:

a. Ted is moving to Chicago. He is going to look at an apartment tomorrow.

b. The Smith family just moved into their new home. # They decided to get the pool.

ANALYSIS

The AJT ratings were converted into z-scoresFootnote 6 and were analyzed using linear mixed-effects regression (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015). The model had AJT ratings as the dependent variable. Condition (4 levels: direct anaphoric, taxonomic anaphoric, anaphoric bridging, and nonanaphoric bridging) and acceptability (2 levels: acceptable and unacceptable) were the independent variables and fixed effects in the model with a random intercept for participants and items.

The felicitous definite test items, as (a) in (11–14) were coded as acceptable and (b) in (11–14) with indefinite articles as unacceptable. Results from a linear mixed-effect model with an interaction between conditions and acceptability suggested that the interaction was significant due to the fact that the high ratings of acceptable NPs in the direct anaphoric condition interacted with the other three conditions. Because what the project aimed to investigate was the rating contrast between acceptable definite NPs and unacceptable indefinite NPs within each condition, not between conditions, a model without an interaction was refitted for each language and proficiency group (advanced Chinese participants, intermediate Chinese participants, and English native speakers). The language and proficiency group were analyzed separately in that it is not informative to make comparisons among them. The purpose of the study was not to compare the degree of acceptance or rejection of native English speakers to that of L2 learners. That means whether L2 learners and native speakers rate the same acceptable sentences 3 or 4 is not a question of interest. Rather, the aim of the analysis was to discover which condition of English definiteness the participants of each group have acquired and that is indicated by the fact that definite acceptable NPs should be rated higher than indefinite unacceptable NPs.

RESULTS

In this study, I set out to investigate the acquisition of the English definite article the in four definite conditions by learners with an article-less language as their L1. The mean AJT ratings and its standard deviation (in parentheses) were calculated and are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3. Mean AJT ratings in four definite contexts (ratings: min = 1, max = 4)

Note: In each condition, mean ratings in the first column are for acceptable definite NPs (abbreviated as “Acc”) and the second column represents mean ratings for unacceptable indefinite NPs (abbreviated as “Unacc”).

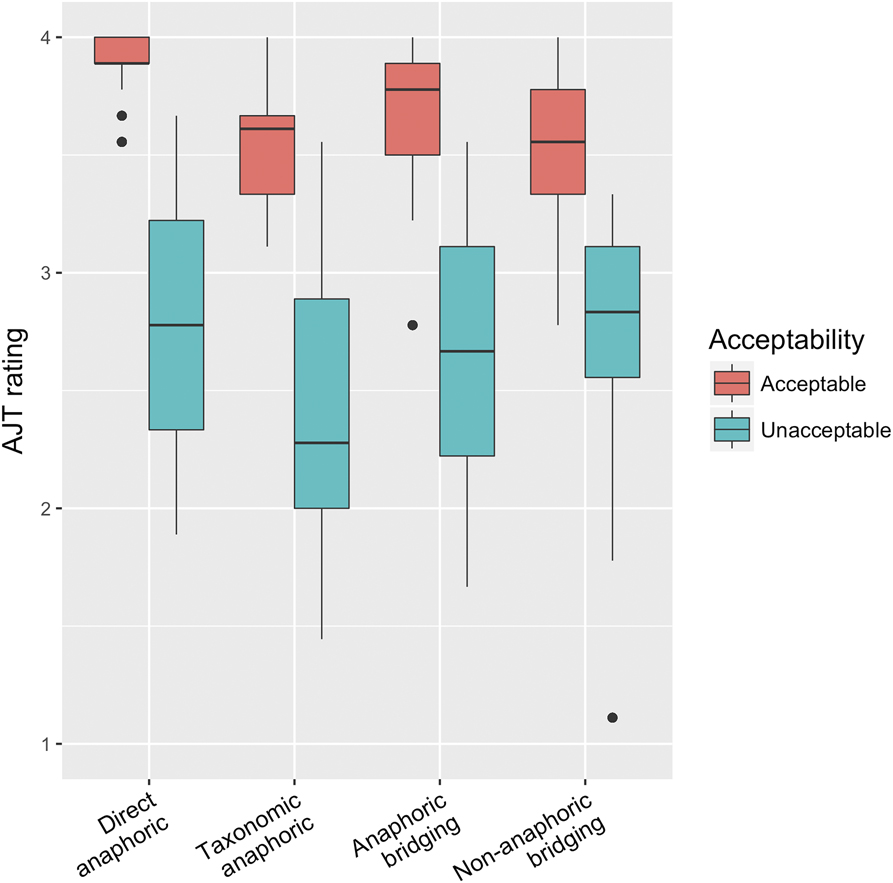

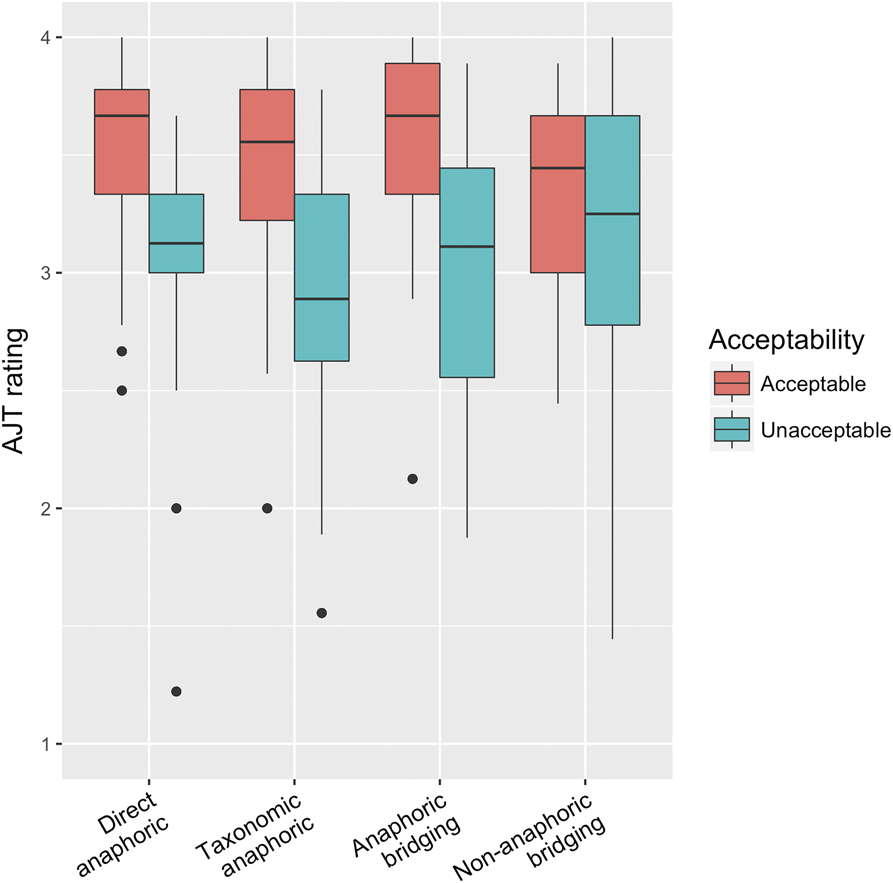

The data in Table 3 are visualized in Figures 1 through 3 for the three participant groups. The native English speakers showed clear rating contrast between acceptable (definite) NPs and unacceptable (indefinite) NPs. Similar contrast is observed among advanced Chinese speakers (although the contrast in nonanaphoric bridging is smaller than the first three conditions). Intermediate Chinese speakers’ response differences between acceptable and unacceptable NPs are not as distinct as in the other two groups.

FIGURE 1. Native English speakers’ AJT ratings for definite (acceptable) and indefinite (unacceptable) NPs in four definite contexts.

FIGURE 2. Advanced Chinese speakers’ AJT ratings for definite (acceptable) and indefinite (unacceptable) NPs in four definite contexts.

FIGURE 3. Intermediate Chinese speakers’ AJT ratings for definite (acceptable) and indefinite (unacceptable) NPs in four definite contexts.

Type III tests of fixed effects reported significant condition effects for English speakers and advanced Chinese speakers (English: F(3, 67.01) = 3.825, p < .05, advanced Chinese: F(3, 66.05) = 5.12, p < .001), acceptability effects for all three groups (English: F(1, 67.01) = 169.35, p < .0001, advanced Chinese: F(1, 66.05) = 101.82, p < .0001, intermediate Chinese: F(1, 67.12) = 34.99, p < .0001). It reflects that unacceptable indefinite NPs were rated significantly lower than acceptable NPs, confirming my prediction, yet different response patterns occurred among groups. To show the response contrast between acceptable definite NPs and unacceptable indefinite NPs for each condition statistically, I conducted multiple pairwise comparisons with Tukey’s adjustment, as summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Acceptability contrast in four definite conditions

*** p < .0001; ** p < .001; * p < .05.

As expected, native English speakers rated acceptable definite NPs higher than unacceptable indefinite NPs in all four conditions. Advanced Chinese participants confirmed my prediction that Chinese speakers can perform as well as native English speakers do. However, intermediate Chinese participants were not sensitive to the acceptable use of the and unacceptable use of a in the nonanaphoric bridging condition as evidenced by the indistinguishable ratings between acceptable and unacceptable sentences in this condition (p = .99, d = .09).

Regarding the control test items (acceptable indefinite NPs and unacceptable definite NPs), results showed that both intermediate and advanced Chinese speakers rated indefinite NPs significantly higher than definite NPs (p < .0001) in the indefinite condition.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The main goal of the present study and Cho (Reference Cho2017) was to explore the interpretation of definite NPs in L2-English by learners with article-less L1s. Chinese, as an article-less language, has a demonstrative determiner nei, which shares the identical feature combination as English the, [+definite, +/-anaphoric]. This study’s results suggested that unlike advanced Korean learners in Cho (Reference Cho2017), advanced Chinese participants showed a contrast between acceptable definite NPs versus unacceptable indefinite NPs in all four definite conditions regardless of anaphoricity. In other words, advanced Chinese participants have achieved nativelike judgment on the. Intermediate Chinese participants only showed a contrast between acceptable and unacceptable sentences in the three anaphoric conditions but not in the nonanaphoric bridging condition (p = .99). Let us revisit a test sentence of the nonanaphoric bridging definite condition:

(16) Andrea just walked into her kitchen. She opened #a microwave and put her dinner inside.

In (16), there is no explicit antecedent of microwave in the first sentence. Interpreting the definiteness of microwave requires additional world knowledge and pragmatic accommodation. It means that learners need to establish the link between the first sentence and microwave and that can be accomplished by accepting the fact that usually there is only one microwave in one’s kitchen. Thus, this test item is expected to receive lower ratings than its acceptable definite counterpart (17).

(17) Sandra is working in her kitchen. She cleaned the microwave first.

Advanced Chinese participants were found to be able to rate (16) significantly lower than (17). There were comments from advanced Chinese participants stating, “How many microwaves does she have?” This shows us clear evidence that some advanced Chinese participants explicitly spotted the presupposition of the number of microwaves in one’s kitchen, therefore, they were able to make the pragmatic accommodation. Another comment that is worth discussing here: “Only if she has more than one microwave” with a rating 4 on (16). This answer demonstrated that advanced participants were not only clear about the presupposition of definite microwave but also confident enough to make up a situation to turn the unacceptable indefinite sentence (16) into a felicitous one. However, intermediate Chinese participants did not distinguish between acceptable (as (17)) and unacceptable (as (16)) sentences in this condition and they rated both high (mean ratings: acceptable 3.31 vs. unacceptable 3.18). This finding has two implications: First, intermediate learners’ high acceptance on acceptable definite sentences suggested that they allowed the to appear in the nonanaphoric condition; second, the high ratings on unacceptable indefinite sentences (acceptance of a) indicated that they failed to realize that the is obligatory in this context. Although Chinese nei and English the share the same formal feature combination, nei is optional in Chinese whereas the is mandatory in English in definite NPs. The distributional factor is not explicitly spelled out in the feature combination, but L2 learners have to acquire it for a full understanding of English articles. As Hwang and Lardiere (Reference Hwang and Lardiere2013) state, in the reassembly process, learners have to acquire not only formal linguistic features but also distributional factors, “including conditions under which such forms are obligatory, optional or prohibited” (p. 58).

Similar interpretation difficulty of the nonanaphoric bridging condition by Chinese speakers has been reported in Xu, Shi, and Snape (Reference Xu, Shi and Snape2016). They discovered that when the was used anaphorically, Chinese participants achieved a nativelike interpretation. However, what appeared to be the most difficult to acquire for intermediate Chinese participants in Xu et al. and in this study was the nonanaphoric condition (the large situation context in Xu et al., Reference Xu, Shi and Snape2016) where pragmatics is relevant. When pragmatics is involved, these findings, along with those in Cho’s study, suggest that in the process of article acquisition, there should be one more step—presupposition accommodation.

The English definite article the presupposes different types of information, for example, presupposition of familiarity and presupposition of uniqueness, as discussed in “Definite Descriptions in English.” When the antecedent of a definite NP is implicit in a discourse, presupposition accommodation is required (Roberts, Reference Roberts2003). For instance, to satisfy the presupposition of uniqueness of the bride in (7), hearers have to assume that, from their general pragmatic knowledge, there is one and only one bride at a wedding. This kind of accommodation in (7), as well as the kitchen and microwave case in (17), requires pragmatically based inferences. Therefore, the acquisition of nonanaphoric definiteness is essentially at the semantics-pragmatics interface, that is, the semantic knowledge of definiteness and uniqueness interacts with pragmatic inferences. At this interface, where the grammar interacts with the extralinguistic system, that is, pragmatics, L2 speakers experience considerable difficulties (Sorace, Reference Sorace2011). That is because the acquisition of interfaces such as the semantics-pragmatics interface involves not only the appropriate semantic and pragmatic knowledge but also L2 learners’ ability to integrate the two types of knowledge, which may be beyond L2 learners’ abilities. In the case of English article acquisition, what appeared to be the problem for intermediate Chinese participants was their inability to integrate semantic knowledge and pragmatic inferences at the interface level. Thus, intermediate learners failed to accommodate the presupposition of uniqueness in the nonanaphoric condition. Furthermore, intermediate Chinese participants’ failure and advanced participants’ success in having rating contrasts in the nonanaphoric condition indicated that the ability to accommodate presuppositions was not automatically acquired even when feature reassembly was unnecessary for both groups.

Comparing L1-Korean learners in Cho (Reference Cho2017) with Chinese participants in the current study, differences in acquisition at the semantics-pragmatics interface occurred. Advanced Chinese participants showed nativelike ratings in all definite conditions whereas advanced Korean participants still had difficulties in accommodating presuppositions for bridging definite NPs. In other words, not having to reassemble features, advanced Chinese speakers were able to accommodate the presupposition of uniqueness earlier than advanced Korean speakers who still needed to reassemble features besides presupposition accommodation. However, the acquisition pattern in both studies displays an incremental tendency in that, overall, advanced learners performed better than intermediate learners. For a full understanding of English definiteness, especially the nonanaphoric type, further exposure and input to the target language is necessary for L2 speakers to become more sensitive to the pragmatic cues in the discourse.

In conclusion, the current study examines the interpretation of English definite NPs by L1-Chinese L2-English speakers. Results from an AJT by intermediate and advanced Chinese speakers suggest that the ability of making presupposition accommodation at the semantics-pragmatics interface is not automatically acquired, even when feature reassembly is not necessary. Furthermore, the findings of this study, taken together with Cho’s (2017), are argued to show that presupposition accommodation can be acquired earlier when feature reassembly is not required than in the case where feature assembly is required.