1. Introduction

This article analyzes prestopped nasals in Umbuygamu (also known as Morrobolam),Footnote 1 a Lamalamic (< Paman < Pama-Nyungan) language of Cape York Peninsula, in northeastern Australia. The aim of the article is primarily descriptive, with a focus on features that are typologically unusual, viz. a relatively long and voiceless plosive phase, the existence of preaspirated realizations, and different types of nasal plosion as a pathway for the emergence of preaspiration from prestopping.

Prestopped nasals form a contrastive series in Morrobolam, contrasting with plain nasals. Both originate historically in intervocalic nasals, under different conditions, as illustrated in the examples in (1). Their origins and phonological status as single segments are discussed in more detail in section 2 of this article.

The canonical realization of a prestopped nasal in Morrobolam consists of a voiceless hold phase, followed by a nasally released burst, followed by a nasal phase, as illustrated in Figure 1 above (see section 3 for internal segmentation). Other types of realization include preaspirated and plain nasal ones, as discussed in more detail in section 5 of this article. Note that the relative length of the plosive and nasal phases in the canonical realization suggests that the term prestopped nasal may not be the most appropriate term from a phonetic perspective, but this is the term that has been used in most of the Australianist literature (and beyond), so I will retain it for ease of reference. I will also use a neutral transcription, rather than employing superscript for one or the other phase.

Figure 1. Waveform and spectrogram for itna ‘ear’ (RL); see section 3 for internal segmentation.

There is an articulatory link between plain and prestopped nasals, which has often been described in terms of the relative timing of oral and velic gestures (e.g. Maddieson & Ladefoged Reference Maddieson, Ladefoged, Huffman and Krakow1993; Butcher Reference Butcher, Ohala, Hasegawa, Ohala, Granville and Bailey1999, Reference Butcher, Harrington and Tabain2006; Round Reference Round, Pensalfini, Turpin and Guillemin2014). If velic opening is delayed relative to oral closure, this results in a prestopped nasal rather than a plain nasal. Or, conversely, if velic closure is earlier than oral release, this results in a prenasalized stop.Footnote 3 Even if the relation between plain and prestopped nasals is a natural one in articulatory terms, contrastive prestopped nasals are rare typologically. As an indication, the PHOIBLE database of phoneme inventories for 2,186 languages (Moran & McCloy Reference Moran and McCloy2019) has just three languages with contrastive bilabial prestopped nasals, all in Australia (as against over 370 languages with contrastive bilabial prenasalized stops of some kind). For Australian languages, it has been proposed that prestopping of nasals (contrastive or not) may be related to the relatively large number of places of articulation in their typical inventories (e.g. Butcher Reference Butcher, Ohala, Hasegawa, Ohala, Granville and Bailey1999). Specifically, it has been argued that late velic opening may help to preserve place of articulation cues in formant transitions from the preceding vowel, which would otherwise be reduced by anticipatory nasalization in the vowel (Butcher Reference Butcher, Ohala, Hasegawa, Ohala, Granville and Bailey1999, Reference Butcher, Harrington and Tabain2006; Round Reference Round, Pensalfini, Turpin and Guillemin2014; Fletcher & Butcher Reference Fletcher, Butcher, Koch and Nordlinger2014). Similar motivations have also been proposed for other regions (e.g. Wetzels & Nevins Reference Wetzels and Nevins2018 for South America). Such considerations mainly explain the existence of prestopped variants for plain nasals, but they do not necessarily explain why and how they can become contrastive.

Regardless of the motivation, however, it does look like Australia is the main area for contrastive prestopped nasals. Beyond Australia, they have only been reported elsewhere in Oceania, for instance in Yélî Dnye (isolate, Papua New Guinea; Levinson Reference Levinson2022), and in Southeast Asia, for instance in Banyaduq (Austronesian > Land Dayak; Jardine et al. Reference Jardine, Athanasopoulou and Cole2015). Within Australia, contrastive prestopped nasals have been reported for languages in the Arandic, Karnic, Thura-Yura and Paman subgroups of Pama-Nyungan; Round (Reference Round, Pensalfini, Turpin and Guillemin2014) and Harvey (forthcoming) provide surveys of prestopped nasals (contrastive and allophonic) in Australian languages, with relevant references. Detailed phonetic descriptions are available for Kaytetye (Arandic; Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Lin, Turpin, Davies and Demuth2015), which has contrastive prestopped nasals and non-contrastive prestopped laterals, and for Arabana (Karnic; Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, San, Carew, Strangways, Simpson and Stockigt2019), which has contrastive prestopped nasals and laterals. The results show, among other things, that prestopping is significantly longer in contrastive than in non-contrastive prestopped segments in Kaytetye, and that contrastive prestopped nasals are best analyzed as heterosyllabic clusters in Arabana.

The present study is not so much focused on issues like cluster status, but has primarily descriptive aims, with a focus on an acoustic and articulatory analysis of those aspects of prestopped nasals in Morrobolam that are typologically unusual or unexpected. Section 2 provides some background on the language and the phonological status of prestopped nasals. Section 3 discusses the materials used for this study and principles of segmentation. Sections 4–6 constitute the bulk of the analysis. Section 4 investigates the relation between the plosive and nasal phases in prestopped realizations, in terms of duration and voicing. The results show that the plosive phase is significantly longer than the nasal phase and almost consistently voiceless, with a few principled exceptions. This is quite different from what we know about prestopped nasals in the available literature. The most common articulatory account of the origins of prestopping – delayed velic closure to protect place of articulation features – leads one to expect a plosive phase that is secondary to the nasal phase in articulatory terms, i.e. shorter and voiced. And the published accounts of contrastive prestopped nasals also suggest that plosive phases are either shorter or similar to the nasal phases in terms of length. Section 5 investigates two less common realizations of prestopped nasals, viz. preaspirated realizations, found in the speech of two speakers, and plain nasal realizations, found in one specific context for all speakers. Section 6 zooms in on nasal plosion, in the burst phase of prestopped realizations, which has distinct properties in those speakers that also have preaspiration. I argue that these differences may help to explain the emergence of preaspiration from prestopping. I also suggest that their articulatory basis may lie in a distinction in the mechanics of velum lowering, though this remains speculative with only acoustic data to hand. Section 7 rounds off with a discussion of some broader implications, including the origins and development of long voiceless plosive phases for prestopped realizations, and parallels with voiceless nasals for preaspirated realizations.

2. Background

This section provides some background on the Morrobolam language (§ 2.1), and on the phonological status of prestopped nasals, specifically their relation to plain nasals (§ 2.2) and their segmental status (§ 2.3).

2.1 Morrobolam

Morrobolam is a language of the Lamalamic subgroup of Paman languages, themselves a subgroup of the large Pama-Nyungan family. The Lamalamic subgroup consists of three languages, viz. Morrobolam and Mbarrumbathama, which together form the coastal branch, and Rimanggudinhma, which is somewhat more distantly related (see further in Verstraete Reference Verstraete2018a).

Geographically, the larger Paman subgroup comprising Lamalamic more or less coincides with Cape York Peninsula, in Australia’s northeast. Morrobolam belongs to country on the central east coast of the peninsula, in the Princess Charlotte Bay region (see further in Rigsby Reference Rigsby, Dutton, Ross and Tryon1992 and Verstraete Reference Verstraete2025 for more details on location). The language is no longer used in daily life, but it is documented in a large corpus of archival materials, recorded between 1960 and 2024. Verstraete (Reference Verstraete2025: 33–36) provides more details on the available sound recordings; section 3 discusses the materials used in this study. Published material on the language includes two sketch grammars (Ogilvie Reference Ogilvie1994; Sommer Reference Sommer1998), a dictionary (Verstraete Reference Verstraete2025), and a number of studies of specific topics (Laycock Reference Laycock, Harris, Wurm and Laycock1969; Sommer Reference Sommer1976; Rigsby Reference Rigsby, Dutton, Ross and Tryon1992, Reference Rigsby, McConvell and Evans1997; Verstraete Reference Verstraete, Malchukov and Siewierska2011, Reference Verstraete2018a, Reference Verstraete2018b, Reference Verstraete2019, Reference Verstraete and Bowern2023).

2.2 Prestopped and plain nasals

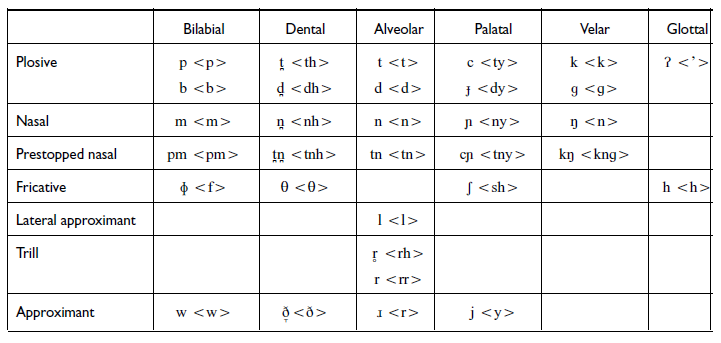

Table 1 below gives an overview of the consonant phoneme inventory in Morrobolam, with the representation in practical orthography between < >, as used in Verstraete (Reference Verstraete2025).

Table 1. Morrobolam consonant inventory

Within this inventory, prestopped nasals form a contrastive series, contrasting with plain nasals and two sets of plosives (voiceless and voiced). Note that this corrects Verstraete (Reference Verstraete2019), where prestopped nasals were analyzed as allophones of plain nasals, reflecting work with a younger generation of speakers who have largely collapsed the distinction into a single series of plain nasals. A full analysis of archival materials (Verstraete Reference Verstraete2025) has now corrected this.

The examples in (2)–(6) below illustrate the contrasts with (near-)minimal pairs for the five relevant places of articulation.

Historically, prestopped nasals originate in plain nasals in intervocalic position, as shown in (7).

This is part of a suite of developments whereby root-initial consonants were weakened and lost, stress shifted to the second syllable, and consonants in the onset of that syllable diversified into a number of new contrasts, including not just prestopped nasals, but also fricatives and voicing contrasts for plosives and trills (see Hale Reference Hale1964, Reference Hale and Sutton1976a, Reference Hale and Sutton1976b, for the basic model as applied to Northern and Middle Paman languages and Verstraete Reference Verstraete2018a, Reference Verstraete and Bowern2023 for an analysis of developments in Lamalamic). The development of prestopped nasals is conditioned by the nature of the original initial consonant, with initial nasals blocking prestopped nasals, as shown in (8).

This is comparable to the diachronic pathways proposed for prestopped nasals elsewhere in Australia (e.g. other Paman languages [Black Reference Black, Bowern and Koch2004], Arandic [Koch Reference Koch, Tryon and Walsh1997] and Karnic [Hercus Reference Hercus1994]).

2.3 Segmental status

Prestopped nasals originate in plain nasals, and are largely collapsed with plain nasals in the last generation of speakers. A historical link with plain nasals is not in itself sufficient as an argument for single segment status, but there are phonological reasons to analyze prestopped nasals as single segments rather than as homorganic plosive-nasal clusters.

One argument relates to the nature of consonant clusters in Morrobolam: there are relatively few of them, and they are phonotactically irregular (see Verstraete Reference Verstraete2018b for a detailed analysis of clusters). In Pama-Nyungan languages, intervocalic clusters tend to be very regular in phonotactic terms: in intervocalic position, the most common cluster types are homorganic nasal-plosive clusters and heterorganic liquid-plosive clusters (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1996; see also Baker Reference Baker, Koch and Nordlinger2014; Round Reference Round and Bowern2023a). In Morrobolam, by contrast, intervocalic clusters have been largely eliminated diachronically, with homorganic nasal-plosive clusters reflected as single voiced plosives, and liquid-plosive clusters mainly reflected as single voiceless plosives (see Verstraete Reference Verstraete2018a). Synchronically, this results in a language with fewer clusters than the average Pama-Nyungan language, and what clusters there are, are extremely diverse phonotactically (see Verstraete Reference Verstraete2018b: 385–388 for an overview, and an argument that cluster diversity is most likely attributable to accidental historical factors like old morpheme boundaries). In this context, analyzing prestopped nasals as homorganic plosive-nasal clusters would make them not just the only systematic homorganic cluster type in the language, but almost the only phonotactically regular cluster type in the language. From this perspective, a single-segment analysis makes more sense phonotactically.

A second argument relates to use of prestopped nasals in word onset position. Like most Pama-Nyungan languages, Morrobolam restricts word onsets to single consonants (e.g. Baker Reference Baker, Koch and Nordlinger2014). Prestopped nasals can occasionally occur in word onset position, as shown in (9).Footnote 4 If they were analyzed as clusters, they would be the only cluster type to occur in this position, which again argues in favor of analyzing them as a single segment rather than a cluster.

To summarize, the overall phonotactic structure of the language suggests that prestopped nasals should be analyzed as single segments rather than homorganic clusters, at least phonologically. More general discussion of phonological argumentation relating to single-segment versus cluster status can be found in Ladefoged and Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 118–131) and Riehl (Reference Riehl2008), as well as Harvey et al. (Reference Harvey, San, Carew, Strangways, Simpson and Stockigt2019), Round (Reference Round and Bowern2023a, Reference Round2023b) and Harvey (forthcoming) for a number of Australian languages.

3. Materials and segmentation

This section discusses the materials used for this study (§ 3.1), and the principles used for segmenting tokens of the different realizations of prestopped nasals (§ 3.2).

3.1 Materials

The materials we have for Morrobolam are essentially a closed corpus for prestopped nasals: as already mentioned, the youngest generation of speakers have largely lost prestopping, and mainly use a single series of plain nasals. Of the 14 documented speakers of Morrobolam, nine have prestopped nasals in their inventories, and of these nine, we have sound recordings for seven (see Verstraete Reference Verstraete2025: 33–36 for an overview of the corpus). For a phonetic study of prestopping, we need recordings of good sound quality, that are more or less comparable in terms of recording situation. The best candidates for this are lexical elicitation sessions. Within the relevant part of the corpus, we have lexical elicitation of good sound quality for three speakers: Bob Bassani (BB), recorded in 1972 by Bruce Sommer, Nellie Salt (NS), recorded in 1972 by Bruce Sommer, and Rosie Liddy (RL), recorded in 1972 by Bruce Rigsby. These recordings form the basis of this study. All are available at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, and the Fryer Library of the University of Queensland.

Elicitation in the three sessions covered both lexicon and some grammar; for our purposes, only lexical elicitation was considered, mostly resulting in single items or, in a few instances, with a minimal grammatical frame provided by the speaker. For each session, all tokens of lexical items containing (phonologically) prestopped nasals were extracted, including instances where these were realized as plain nasals. This resulted in a corpus of 210 word tokens: 44 for BB, 101 for RL, and 65 for NS, reflecting the size of the respective corpora. Some word tokens contained more than one prestopped nasal, so the total number of instances of prestopped nasals for this study is 221.

3.2 Segmentation

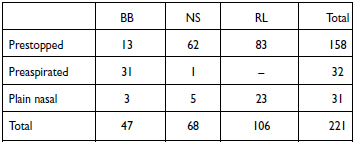

All tokens were transcribed and segmented manually in Praat (Boersman & Weenink 2024), using the broad transcription presented in Verstraete (Reference Verstraete2025). Prestopped nasals were further subdivided into hold, burst and nasal phases (for prestopped and plain nasal realizations) and hold, burst, aspiration and nasal phases (for preaspirated realizations); holds and bursts are optional in the latter case, as discussed in more detail below. Table 2 below summarizes the numbers for the three basic variants in the data set.

Table 2. Major variants in the data set

Figure 2. Waveform and spectrogram for itna ‘ear’ (RL), with internal segmentation of the prestopped nasal (H = hold, B = burst, N = nasal).

For standard prestopped realizations, i.e. [vowel – hold – (burst) – nasal – vowel], segmentation principles were as follows – illustrated in Figure 2 above. The end of the vowel was taken as the end of a clearly articulated formant structure, usually two to three periods before the end of voicing if the following hold was voiceless (as is usually the case for prestopped nasals in Morrobolam). The hold phase of the prestopped nasal was taken as the end of the vowel as just defined, until the first impulse of the burst. The burst phase – if discernible – was taken as the first impulse until the start of a clearly articulated formant structure for the nasal, usually including two to three periods of voicing before the start of nasal formants. The nasal phase was taken as the start of nasal formant structure until the start of the formant structure of the following vowel. This could usually be distinguished from nasals in terms of a more complex formant structure and a difference in intensity. The periods of voicing at the start and the end of the plosive phase were included in the hold and the burst as just discussed, but they were also segmented separately in a narrower segmentation, in parallel with segmentation of preaspirated realizations discussed below. This allowed for a more precise measure of the internal structure of bursts, for use in section 6.1 below.

Preaspirated realizations are distinguished by a period of relatively steady turbulence taking up most of the non-nasal part of the segment, instead of a hold-burst structure as in regular prestopped realizations. In some tokens the non-nasal part of the segment has no plosive-like characteristics at all, as illustrated in Figure 3 above. In other tokens the period of turbulence can start with a burst, i.e. an impulse with an associated peak in intensity, which often contrasts with the lower and more steady intensity of the rest of the aspirated phase, as in Figure 4 below, though it is difficult to segment the two in a principled way. Such bursts can be preceded by an extremely short hold, defined here as limited to the few periods of voicing associated with the end of the preceding vowel, to keep these instances parallel with preaspiration that has no burst. Note that this last feature is also what distinguishes preaspirated nasals with burst-and-aspiration from standard prestopped nasals with long or noisy bursts: standard prestopped realizations always have a regular hold phase.Footnote 5 This is, of course, a sliding scale, but as just mentioned we use the most restrictive definition of holds and bursts preceding preaspiration, to keep these parallel with preaspiration without bursts. And as will be argued in section 6, the scalar nature of hold length offers an interesting pathway for the emergence of preaspiration.

Figure 3. Waveform and spectrogram for epmen ‘grandchild type’ (BB), with internal segmentation of the prestopped nasal (A = aspiration, N = nasal).

Figure 4. Waveform and spectrogram for utnarka ‘frill-neck lizard’ (BB), with internal segmentation of the prestopped nasal (H = hold, A = aspiration (burst-initiated), N = nasal).

Given these observations, segmentation of preaspirated realizations was based on a sequence [vowel – (hold) – (burst &) aspiration – nasal]. The boundaries of vowels, holds and nasals were defined as above. For aspiration, two types of segmentation were used. A broad type used supraglottal, formant-based criteria as above, i.e. from the end of the vowel (or hold if there is one) until the start of the nasal. However, since aspiration involves turbulence, a secondary, narrower, type of segmentation was made to delineate the turbulent phase (following Hejná’s (Reference Hejná2016) definition). This took aspiration to start at the onset of turbulence (or an impulse if it starts with a burst) and end at the offset of turbulence; in most instances, turbulence is preceded by a few periods of voicing beyond the breakdown of formant structure for the preceding vowel, and followed by a few periods of voicing before the start of nasal formants, as shown in Figure 4 above. Note that the presence of a burst at the start of aspiration, as in Figure 4, is easy to recognize, but not easy to segment from the following aspiration in any principled way, so the presence of a burst is noted in labeling, but it is not segmented separately.

The analysis in sections 4 and 5 partly relies on duration values for the different phases of prestopped and preaspirated realizations, as defined in this section. Duration values were extracted automatically for each part of the prestopped nasal using a Praat script (Crosswhite & Antoniou n.d., adjusted for multiple-tier annotations). The raw duration measurements for all phases of each token in the data set are available as supplementary materials, in addition to a number of derived values used in the analysis. The materials have subsections for preaspirated and prestopped/plain nasal realizations, each with their own preface summarizing principles of segmentation, basic duration measurements and derived values. The analysis in section 6 also relies on intensity measurements for the burst phase of prestopped realizations. Section 6.1 describes in more detail how these were extracted; the raw values are again available in the materials, together with derived values as used in the analysis.

4. Prestopped realizations: Plosive and nasal phases

This section discusses the relation between plosive and nasal phases for standard prestopped realizations, in terms of duration (§ 4.1) and voicing (§ 4.2).

4.1 Relative duration

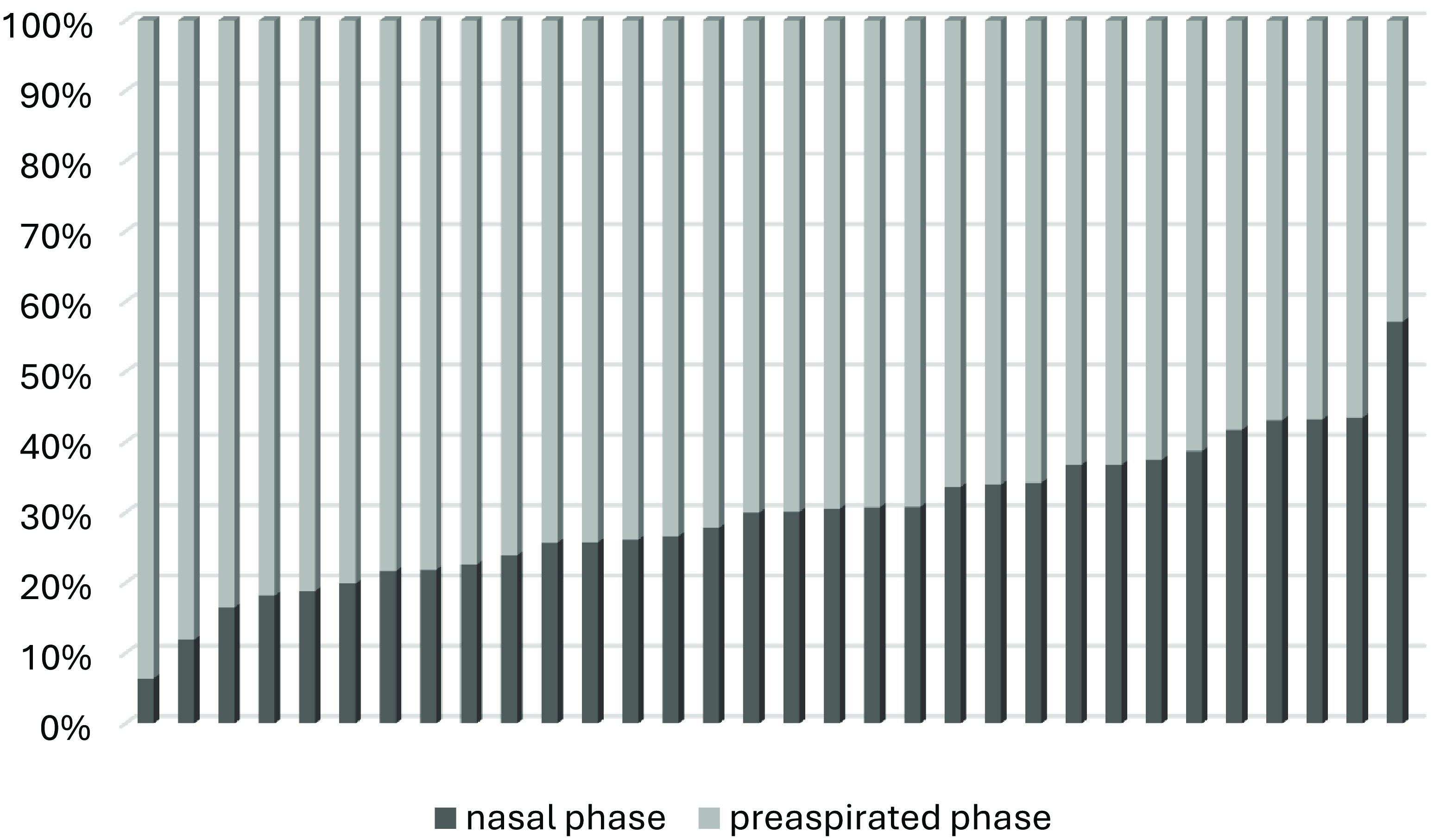

One aspect of the internal structure of prestopped nasals concerns the relative duration of plosive and nasal phases. As a first approximation, we can use a fairly simple measure of relative duration, viz. the percentage of the full segment taken up by the nasal phase. This is represented in Figure 5 above, for all prestopped tokens for which we can measure a full plosive phase (N = 150).Footnote 6 If we take 50% as an initial baseline, the overall results show a very clear trend: 139 tokens have a nasal phase that takes up less than half of the segment’s duration, and only 11 have a nasal phase that takes up half or more of its duration.

Figure 5. Relative duration of nasal and plosive phases (%), for all prestopped tokens for which a full plosive phase can be measured (N = 150); one bar represents one token.

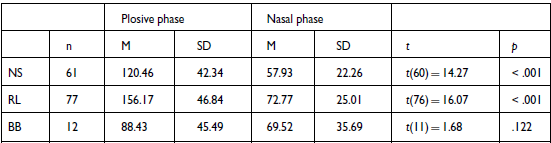

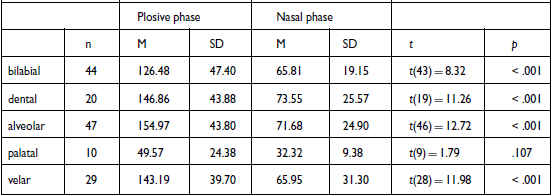

The trend is confirmed by a paired t-test, which shows that in the full set of tokens (N = 150; all prestopped tokens for which a full plosive phase can be measured), the mean duration of plosive phases (M = 136.23, SD = 49.86) is longer than the mean duration of nasal phases (M = 66.49, SD = 25.75), which is significant (t(149) = 19.26, p < .001). To obtain a more fine-grained view of the data, I also provide an assessment by speaker (BB, NS, RL) and by place of articulation (bilabial, dental, alveolar, palatal, velar), in Tables 3 and 4 below. These confirm that plosive phases are significantly longer than nasal ones for most speakers and places of articulation, except for speaker BB and the palatal place of articulation.Footnote 7 The subsets for BB and palatals have very low numbers, however, and do not show normal distribution. Consequently, I also performed a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for these subsets, which has fewer assumptions about the nature of the data. The results are the same: there is no significant difference between plosive and nasal phases for speaker BB (W = 18, p = 0.11), and for the palatal place of articulation (W = 12, p = 0.13).

Table 3. Paired t-tests by speaker (M = mean in ms, SD = standard deviation)

Table 4. Paired t-tests by place of articulation (M = mean in ms, SD = standard deviation)

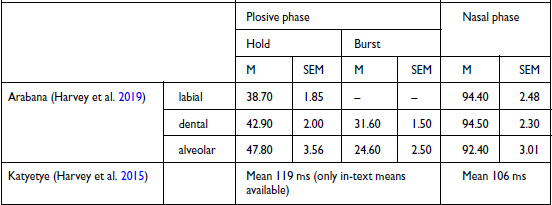

In sum, the analysis shows that for prestopped nasals in Morrobolam, the plosive phase is significantly longer than the nasal phase, except for the subset of speaker BB and for palatals, for which there is no significant difference between the two phases. This is quite different from what is known from the published literature about prestopped nasals. On the one hand, the common articulatory account of the origins of prestopping – delayed velic closure to protect place of articulation cues – leads to an expectation that the plosive phase of a prestopped nasal is secondary to the nasal in articulatory terms, i.e. shorter than the nasal. On the other hand, the measurements that can be found in the two published accounts of contrastive prestopped nasals also suggest that plosive phases are either shorter than or similar to nasal phases, but not longer, or at least not as obviously as in Morrobolam. The raw numbers are not available, but the published means for plosive and nasal phases in Arabana (Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, San, Carew, Strangways, Simpson and Stockigt2019) and Kaytetye (Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Lin, Turpin, Davies and Demuth2015), listed in Table 5 above, are clear enough.

Table 5. Published means for plosive and nasal phases in contrastive prestopped nasals in Arabana and Kaytetye (M = mean, SEM = standard error of the mean)

Given these differences in relative duration, one might argue that for Morrobolam, these segments are more appropriately described as postnasalized stops rather than as prestopped nasals, the traditional term used in the Australianist literature. However, relative duration is only one parameter: the parameter of voicing, discussed in the next section, tells a slightly different story, which distinguishes these segments from plain plosives in the same language.

4.2 Voicing

The default setting for the plosive phase of prestopped nasals in Morrobolam is voiceless. The basic measure for this is the absence of voicing in both the hold and the burst phase of the prestopped nasal (except for the end of voicing associated with the previous vowel and the start of voicing for the nasal phase; see section 3.2 above). In the 150 tokens examined in the previous section, the plosive phase is voiceless in 132 tokens, and voiced in only 18.

From this perspective, the plosive phase of a prestopped nasal is quite different from plain plosives in Morrobolam, which have a phonemic voicing contrast. In fact, voicing for plosive phases is similar to that of the other class of obstruents in Morrobolam, viz. fricatives. Fricatives are voiceless by default, but they can be voiced in post-tonic contexts, as illustrated in (10) (see further in Verstraete Reference Verstraete2019).

Figure 6. Spectrogram and waveform for agulpmal ‘freshwater crocodile’ (RL), with a voiced plosive phase (H = hold, N = nasal).

All of the tokens of voiced plosive phases in the prestopped nasals in our data set are post-tonic. Figure 6 below illustrates a token with the prestopped nasal in the onset of syllable 3, i.e. beyond the stressed syllable 2.

If we compare this with the existing literature on prestopped nasals, this is again somewhat different from expectations. The articulatory account of the origins of prestopping suggests that the plosive phase is a secondary extension of the nasal, not just in terms of length but also in terms of voicing, anticipating laryngeal settings from the (voiced) nasal phase. Among the two published accounts of contrastive prestopping, only Kaytetye is like Morrobolam in terms of voicing. Prestopped nasals in Arabana are described as ‘normally’ voiced (Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, San, Carew, Strangways, Simpson and Stockigt2019: 452), while transcriptions and available spectrograms in Harvey et al. (Reference Harvey, Lin, Turpin, Davies and Demuth2015) suggest that the plosive phase of prestopped nasals in Kaytetye is voiceless. This is actually confirmed by Maddieson & Ladefoged’s report of contrastive prestopped nasals in another Arandic language, Eastern Arrernte (Maddieson & Ladefoged Reference Maddieson, Ladefoged, Huffman and Krakow1993: 292, also cited in Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Lin, Turpin, Davies and Demuth2015), where the plosive phase (as well as part of the nasal) is described as ‘almost always’ voiceless.Footnote 8

To conclude, then, our analysis has shown that prestopped realizations in Morrobolam are characterized by a relatively long and voiceless plosive phase, in most cases significantly longer than the nasal phase, and never significantly shorter. Some phonological implications of these findings are discussed in section 7 below.

5. Preaspirated and plain nasal realizations

This section analyzes preaspirated (§ 5.1) and plain nasal realizations (§ 5.2), which are less common in our data set than the prestopped realizations discussed in the previous section

5.1 Preaspirated realizations

Preaspiration is a typologically surprising feature, which to my knowledge has not been reported in the realization of prestopped nasals in the literature. It is found in 32 tokens (or just under 15% of the data set), as the dominant realization for one speaker, and a marginal one for another (see further in Table 2 above). In this section, I discuss the nature of preaspiration in more detail, followed by distribution in the data, and an analysis of length and voicing of preaspiration relative to the nasal phase, in parallel with the analysis in section 4 above. Section 6 below discusses a potential pathway for the emergence of preaspiration from nasal prestopping.

In preaspirated realizations, a period of relatively steady turbulence takes up most of the non-nasal part of the segment, instead of the hold-burst structure that defines the non-nasal part in the prestopped realizations discussed in section 4. As already mentioned in section 3, some tokens have no plosive characteristics at all, while for others the period of turbulence starts with a burst and can be preceded by a very short hold (not exceeding the voiced ‘tail’ of the preceding vowel – see section 3.2 for the motivation behind this restriction). This definition is largely in accordance with Hejná’s (Reference Hejná2016) definition of preaspiration, though with an important difference: in the segments we are studying here, the period of turbulence probably also involves nasal airflow.Footnote 9 With only acoustic data available, this cannot really be demonstrated,Footnote 10 but there are some indications in the analysis in sections 6 and 7 below. To summarize very briefly, if it is the case that burst-initiated preaspiration forms a continuum with prestopped realizations with long and noisy bursts, as argued in section 6, then it would not be unlikely for the burst initiating preaspiration to involve nasal release, just like with standard prestopped realizations. And if preaspirated realizations without bursts are typologically similar to Burmese-style voiceless nasals, as argued in section 7, then it would not be unlikely for preaspiration to involve nasal airflow, given the presence of nasal airflow in the aspirated portion of voiceless nasals (Chirkova, Basset & Amelot Reference Chirkova, Basset and Amelot2019). This still leaves us with the question of where exactly turbulence is generated, i.e. at the glottis, the velopharyngeal port, or both. This question is near impossible to answer with the data at hand, but in sections 6 and 7 I suggest that the velopharyngeal port can be a location for turbulence in nasal airflow.

In the data set, preaspirated realizations are found in the speech of two speakers: they are the dominant realization in the speech of BB (31 out of 47 tokens), and a marginal realization in the speech of NS (just one token, though as will be argued in section 6, this speaker has a number of tokens with short holds and long bursts, approaching but not quite reaching the threshold for burst-initiated preaspiration defined in section 3.2 above). In the case of BB, preaspiration is found for all five places of articulation and in all word positions. There seems to be a predominance of bilabial (n = 13) and alveolar tokens (n = 9), which is impressionistically higher than for prestopped realizations, though with such low numbers it is hard to say if this has any significance. Preaspiration shows no plosive characteristics in 19 tokens, and starts with a burst in 13 tokens.

In terms of relative duration, the relation between preaspirated and nasal phases is impressionistically quite similar to the relation between plosive and nasal phases in prestopped realizations, as shown in Figure 7 below. Note that, to maintain a parallel with duration measurements for prestopped realizations, we use the primary segmentation based on supraglottal criteria (see section 3.2 above), which implies measuring the whole non-nasal part of the spectrum, i.e. including not just the aspiration phase in the narrow sense, but also the few periods of voicing following the end of the preceding vowel (interpreted as a short hold if aspiration is burst-initiated) and preceding the start of the nasal.

Figure 7. Relative duration of nasal and preaspirated phases (%) (N = 32); one bar represents one token.

A paired t-test again confirms the impressionistic trend in Figure 7. The mean duration of preaspirated phases (M = 98.42, SD = 30.19) is longer than the mean duration of nasal phases (M = 41.75, SD = 19.96), which is significant (t(31) = 8.58, p < .001). Given that almost all tokens are from BB’s speech, this also implies that the results are slightly different than for BB’s prestopped tokens, which showed no significant difference in duration between nasal and non-nasal phases. The data set is too small for any meaningful analysis by place of articulation, but the raw numbers are available in the supplementary materials.

Voicing, finally, is similar as with prestopped realizations, in that the default setting for preaspiration is voiceless. The basic measure for this is the absence of voicing in the preaspirated phase in narrow segmentation (which delineates turbulence from residual periods of voicing associated with a flanking vowel and nasal, see section 3.2 above). Among the 32 tokens of preaspiration, only three show partial voicing, as measured by automatic pulse detection in Praat.

The analysis in this section is limited to a basic description of preaspirated realizations, but its typologically unusual link with prestopping is discussed in more detail in section 6, which provides a pathway for the emergence of preaspiration from prestopping. The discussion in section 7 also discusses typological parallels with different types of voiceless nasals.

5.2 Plain nasal realizations

Plain nasal realizations (N = 31) are mainly found in two contexts: in word onset (after a pause) in compound forms (n = 24), and in a small set of roots with two prestopped nasals (n = 3). The second context is rare in the lexicon, and the current data set only has one example (with three tokens), in each case with the first instance realized as a plain nasal, as shown in (11).

The other context concerns compound forms, which consist of two roots that are subject to three phonological rules, two obligatory ones and one typical one, illustrated in (12) below. The obligatory rules are a shift of stress to what would be the location of stress in the second root, and a rule of final vowel deletion for the first root in contexts of vowel hiatus, as shown in (12a). The typical but structurally optional rule is loss of the initial vowel in the first root, which puts the underlying medial consonant in onset position, as shown in (12b).

When the second root has a prestopped nasal in medial position, as in (13), the third rule is what lands the prestopped nasal in word onset, as shown in (13b).

It is this context that is typically associated with plain nasal realizations. An example can be found in Figure 8 above.

Figure 8. Spectrogram and waveform for apmal-erhanh ‘toenail’ (literally ‘toe-shell’) (RL), with a plain nasal realization (N = nasal).

At first sight, word onset after a pause would appear to be a natural context for plain nasal realizations. In the absence of a discernible hold, bursts are the only markers of the plosive phase in this context, which makes this phase much less prominent relative to the nasal phase, and therefore potentially subject to loss. However, compound status turns out to be just as crucial, because prestopped nasals behave differently in word onset of non-compounds in the data set (n = 7). In non-compounds, there is only one plain nasal realization (in a form that historically derives from a compound and is still partly transparent), and all other token have a recognizable burst before the nasal phase. For compounds, plain nasal realizations are found in 24 out of 30 relevant tokens. Given this difference, one may speculate that the internal complexity of compounds leads to greater lexical distinctiveness as opposed to non-compounds, and therefore more leeway in omitting bursts as the sole remaining marker of what is essentially a contrastive phonological feature. In non-compounds (i.e. roots), historical processes like the loss of initial consonants and medial clusters, and the levelling of the second syllable towards low vowels (see sections 2.2 and 2.3, and Verstraete Reference Verstraete2018a for more details) have resulted in a reduction of lexical distinctiveness and a high functional load for consonantal contrasts, which may be what blocks the loss of bursts, even in word onset after a pause.

6. Nasal plosion and preaspiration

To round off the analysis, this section zooms in on the burst phase of prestopped realizations, which shows interesting variation that may provide a clue to the emergence of preaspirated realizations. As already mentioned, bursts are nasally released in prestopped realizations, but nasal plosion is far from uniform across the data. At one end of the spectrum, we have instances that mainly consist of an impulse and are relatively quiet beyond this, as illustrated in Figure 9, while at the other end, we have instances that are much longer than just an impulse, and relatively loud and noisy throughout, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 9. Spectrogram and waveform for okngal ‘mosquito’ (RL), with internal segmentation for the prestopped nasal (H = hold, B = burst, N = nasal).

Figure 10. Spectrogram and waveform for apma ‘person’ (BB), with internal segmentation for the prestopped nasal (H = hold, B = burst, N = nasal).

In this section, I argue that the long, loud and noisy bursts can help to understand how preaspirated realizations may have emerged from prestopped ones. The argument proceeds in two steps. In section 6.1, I explore the distribution of burst types in the data. I show that long, loud and noisy bursts are primarily found with speakers who also have preaspirated realizations, and I argue that they may form a pathway for the emergence of preaspiration from prestopping, with turbulence taking over from hold-burst structure as the primary cue for the non-nasal part of the segment. In section 6.2, I zoom in on the likely articulatory basis of long, loud and noisy bursts. Specifically, I surmise that they can be attributed to a basic difference in the mechanics of velum lowering, which is usually described in terms of various types of muscle-controlled mechanisms (see Gick, Wilson & Derrick Reference Gick, Wilson and Derrick2013: 130–136 for an overview). I suggest that velum lowering can also be reinforced aerodynamically, with an initial muscle-controlled lowering gesture giving way to an aerodynamic process, specifically a rise in intro-oral pressure due to a closed and raised glottis ‘blowing open’ the velum (with a glottalic airstream mechanism that is comparable to the mechanics of ejectives). With only acoustic data at hand, this necessarily remains speculative, but it does conform to auditory impressions and attempts at replication, and there are a few typological parallels in the literature.

6.1 Distribution and pathway to preaspiration

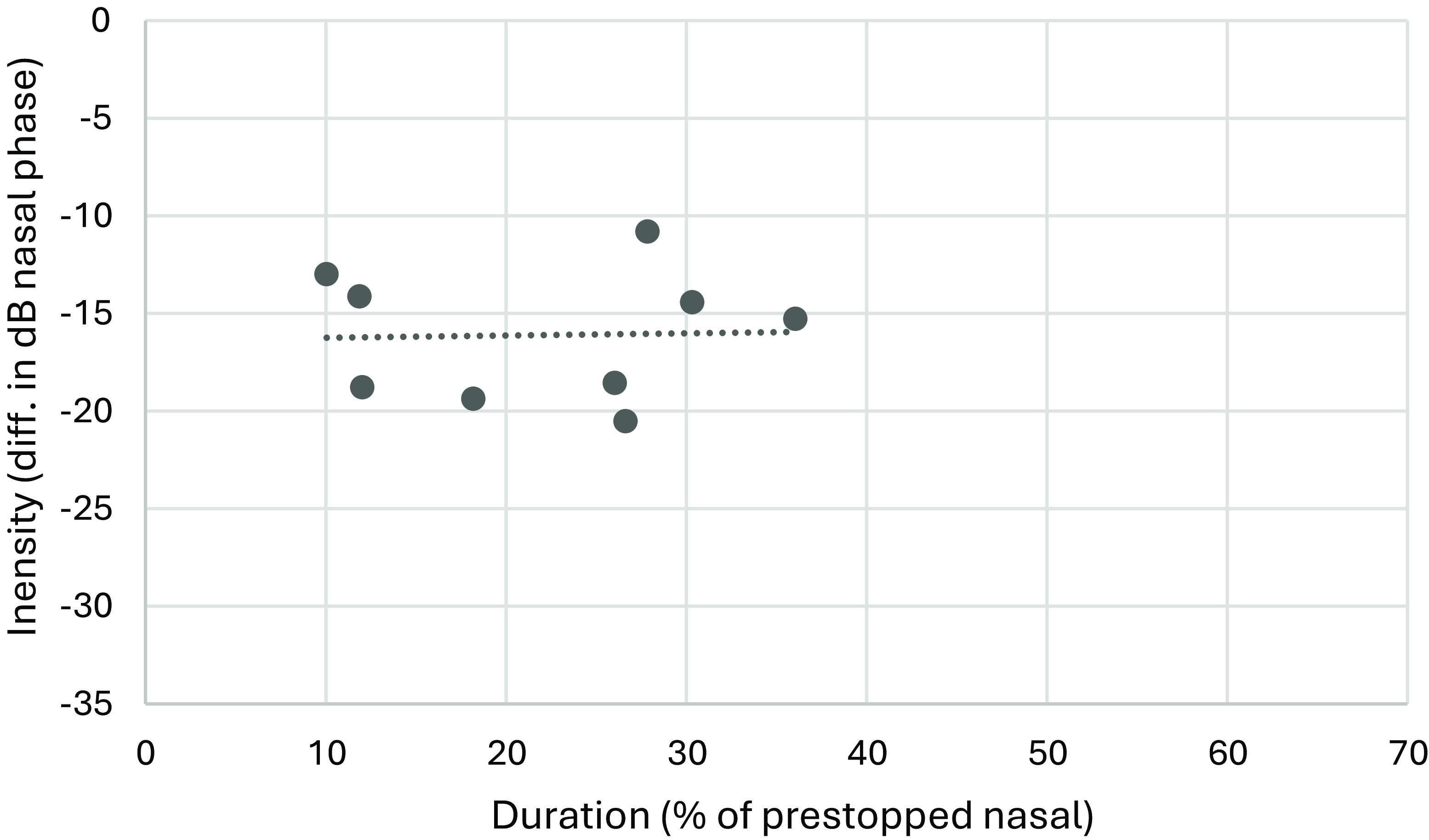

The distribution of burst types in prestopped realizations is examined with two parameters, viz. duration and intensity. A combination of these shows that long, loud and noisy bursts like those in Figure 10 are primarily found in the speech of BB and NS. These are also the speakers with preaspirated realizations, which I will argue is most likely not a coincidence: long, loud and noisy bursts can be interpreted as forming a pathway for the emergence of preaspiration from prestopping.

Bursts were examined for all prestopped realizations in the onset of stressed syllables (N = 123), to control for any word-internal differences in intensity that may be due to stress-related effects. Moreover, bursts were taken as defined by narrow segmentation: from the first impulse until the start of voicing, i.e. not including the few periods of voicing associated with the following nasal (see further in section 3.2 above). Measurement of burst duration is based on the general duration measurements described in section 3.2 above. Specifically, in order to compare burst duration across tokens, I calculated burst length as a percentage of the total duration of the prestopped nasal. Burst intensity is based on a separate measurement of the average intensity of the burst phase of prestopped realizations, automatically extracted using a Praat script (Kawahara Reference Kawahara2010, with an adjusted pitch floor). Intensity is less straightforward to measure than duration, but we can get an approximation of intensity differences among bursts if we take into account two points. One concerns the precision of intensity measurements: for a noisy signal like a burst, a very short analysis window is required for accurate measurement of intensity, which means setting a high pitch floor (at 500 Hz, as done for fricatives, e.g. Elvira-García Reference Elvira-García2019). The other point is that the data for this study are field recordings, i.e. without any standardization of intensity. In order to deal with this, I also extracted a measurement of the average intensity of the nasal phase of the same prestopped realization, to be used as a reference point to compare the intensity of bursts. While absolute values of intensity of both phases may differ, we can assume that intensity of the nasal phase varies with overall intensity levels of a recording, and thus provides a good reference point to compare differences in intensity in the burst phase. Given the nature of the scale, a simple measure of difference in dB relative to the corresponding nasal phase gives an indication of intensity differences for bursts (e.g. a burst with a value of -10dB relative to its corresponding nasal phase is louder than a burst with a value of -20dB).

Figure 11. Scatterplot of burst types for RL (n = 73): burst duration (as a percentage of overall segment duration) and burst intensity (as a difference in dB with the intensity of the associated nasal phase).

Figure 12. Scatterplot of burst types for NS (n = 41): burst duration (as a percentage of overall segment duration) and burst intensity (as a difference in dB with the intensity of the associated nasal phase).

Figure 13. Scatterplot of burst types for BB (n = 9): burst duration (as a percentage of overall segment duration) and burst intensity (as a difference in dB with the intensity of the associated nasal phase).

Figures 11–13 provide a visual representation of the distribution of burst types for the three speakers, using the two parameters. As already mentioned, this represents the bursts of all prestopped realizations in the onset of stressed syllables (N = 123); numbers are very low for BB, who has predominantly preaspirated realizations, but the general trend is quite clear.

An impressionistic comparison suggests that NS’s and BB’s bursts are quite similar to each other, and different from RL’s bursts. Specifically, RL’s bursts have lower average intensity the longer they get: the two values are moderately negatively correlated (r(71) = –.55, p < .001). This can be interpreted as bursts that are mostly dominated by a single impulse, which leads to higher average intensity across the burst if this mainly consists of the impulse (i.e. a short burst), and lower average intensity across the burst if the impulse is the only loud element in the burst, and the rest is silence or low-intensity turbulence (i.e. longer bursts). NS’s and BB’s bursts, by contrast, are significantly louder than RL’s. This is confirmed by an ANOVA of intensity by speaker (F(2, 120) = 9.22, p < .001), with post hoc comparison with Bonferroni correction indicating that burst intensity for RL is lower than for BB (p = 0.047) and NS (p < .001). Moreover, they are quite loud overall regardless of length: they mostly cluster in a band between about half and a quarter of the loudness of their associated nasal phase, which is quite loud given that we are dealing with average intensity across a voiceless obstruent phase, and not just peak intensity associated with a single impulse. In other words, the longer bursts in NS and BB’s speech are of the long, loud and noisy type, as in Figure 10, while the longer bursts in RL’s speech are of the type dominated by a single impulse, as in Figure 9. If we interpret this in terms of the two classic definitions of aspiration (VOT versus turbulence, e.g. Ladefoged & Maddieson Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 66–70), NS and BB’s longer bursts are aspirated in terms of the presence of turbulence, while RL’s longer bursts are aspirated in terms of the delay between the impulse and the onset of voicing, but not necessarily with turbulence in between.

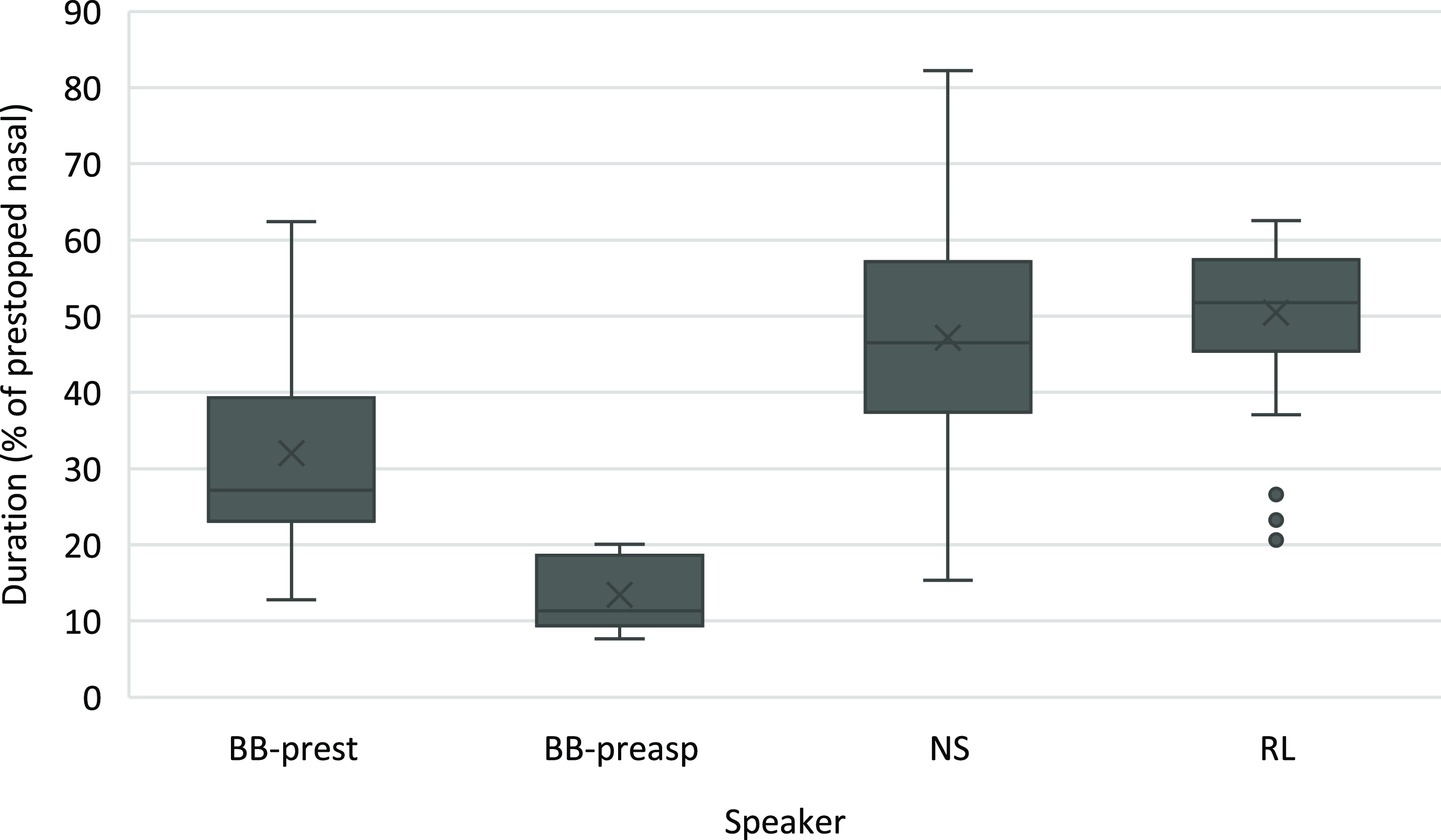

This difference is relevant from the perspective of preaspiration, which as discussed in section 5.2 above is characterized by a relatively long period of turbulence before the nasal phase. The analysis in this section shows that the signature characteristic of preaspirated realizations is also present in a subset of prestopped realizations, viz. the long, loud and noisy bursts in the speech of NS and BB, the two speakers who also have preaspirated realizations. This is suggestive of a pathway for the emergence of preaspiration from prestopping, which is otherwise quite puzzling typologically. The main difference between the long, loud and noisy bursts discussed here and preaspiration, is that prestopped realizations with long and noisy bursts still have a regular hold phase preceding the burst, whereas preaspirated realizations either have no hold at all, or at best a very short one, defined in section 3.2 above as not exceeding the voiced tail of the preceding vowel (to maintain a parallel with preaspiration that is not initiated by a burst). As already mentioned, however, relative duration of the hold is a sliding scale towards short holds, again in particular in the speech of NS and BB. This is shown in the box plots in Figure 14, which represent hold length as a percentage of overall duration of the prestopped nasal realization by speaker (for all prestopped realizations with a hold), and adds hold length for burst-initiated preaspiration in BB’s data.

Figure 14. Hold length as a percentage of prestopped nasal duration (all prestopped realizations with a hold, for BB [n = 12], NS [n = 61] and RL [n = 77], plus burst-initiated preaspiration for BB [n = 5]).

What this suggests is that the speech of NS and BB has a subset of prestopped realizations with long, loud and noisy bursts, which show a continuum from relatively long holds over shorter ones, to very short ones limited to the voiced tail of the preceding vowel in BB’s data, which we have analysed as burst-initiated preaspiration. From that point, the step to ‘pure’ preaspiration simply involves speeding up velic opening until it coincides with oral closure, and bursts are absent from the turbulence defining the non-nasal phase. Figure 15 below presents a gestural representation of this pathway, from prestopped realizations with standard bursts, over prestopped realizations with long, loud and noisy bursts, to preaspirated realizations.

Figure 15. Gestural representation of the proposed pathway from standard bursts to preaspiration, with turbulence marked by shading (based on Blankenship et al. Reference Blankenship, Ladefoged, Bhaskararao and Nichumeno1992; the representation of preaspirated realizations assumes nasal airflow for preaspiration – see further in section 5.1 and fn 10 on this problem).

While this account necessarily remains speculative, it does offer a plausible articulatory pathway from prestopping to preaspiration that appears to be instantiated in the tokens for those speakers that have preaspiration, and originates in the turbulence defining long, loud and noisy bursts.

6.2 Articulatory interpretation

To round off this section, I also offer an articulatory interpretation of the existence of long, loud and noisy bursts. Specifically, I surmise that these bursts may be due to a difference in the mechanics of velum opening, with a glottalic airstream reinforcing muscle-controlled opening of the velum. This is mainly based on auditory impressions and attempts to replicate production. With only acoustic data at hand, it is impossible to provide any hard evidence, but there are some relevant indications. On the one hand, glottalic reinforcement is a straightforward and easily produced mechanism to reinforce velum opening, which can account for increased turbulence in nasal airflow, though it is surprisingly absent from the general literature. And on the other hand, there are at least two potential typological parallels which hint at a similar mechanism, even though neither offers airstream data in support.

There is a rich general literature on velum opening, but most of it deals with issues like timing relative to other articulatory gestures (as discussed in section 1), degrees of opening (e.g. Oh, Byrd & Narayanan Reference Oh, Byrd and Narayanan2021) or speed and general dynamics in continuous speech (e.g. de Boer et al. Reference Boer, Gillian, Purnomo, Wu and Gick2023). The mechanics of velum opening is generally described in terms of different types of muscle-controlled mechanisms (see the overview in Gick et al. Reference Gick, Wilson and Derrick2013: 130–136), but a survey of the general literature did not yield any reference to glottalic reinforcement as a principle in the mechanics of velum opening. Even so, it is an easily produced mechanism to reinforce nasal plosion: if the glottis is closed and raised (as in ejective production), the extra pressure can cause aerodynamics to take over from an initial gesture of muscle-controlled velum lowering, effectively ‘blowing open’ the velum following this initial gesture. From the perspective of Morrobolam data, this could also provide an articulatory basis for the turbulence characterizing long, loud and noisy bursts. If the velum is lowered and then ‘blown open’ by targeted pressure due to closing and raising of the glottis, this will cause a greater rush of air through the nose, causing louder and longer turbulence, at the velopharyngeal port and within the nose. Moreover, if velum opening is aerodynamically reinforced, one would also expect occasional misfires like second closures, as is typical for aerodynamic processes. There are a few examples of this in the data, as illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 16. Waveform and spectrogram for utna ‘shit’ (BB), with internal segmentation of the prestopped nasal. (H = hold, B = burst, N = nasal).

A second argument in support of this articulatory interpretation is the existence of potential typological parallels. As already mentioned, this mechanism of velum opening is not listed in any of the general literature, but a survey of nasal release in specific languages did yield two typological parallels. The clearest one can be found in Levinson’s (Reference Levinson2022) analysis of Yélî Dnye (isolate, Papua New Guinea), which has a (partial) series of what is described as nasally released plosives (equivalent to our prestopped nasals), contrasting with full series of prenasalized plosives, plain plosives and plain nasals. The nasally released plosives are described as involving ‘a sharp voiceless release through the nose’ and producing ‘a nasal plosion (as Henderson Reference Henderson1995: 7 puts it), which in citation forms at least may perhaps be produced initially by a non-pulmonic (glottalic) air-stream mechanism’ (Levinson Reference Levinson2022: 53). While the formulation is tentative, this is the clearest reference I have been able to find to glottalic reinforcement in velum opening. Another, less direct, indication can be found in Schuh’s (Reference Schuh2008) work on Karekare (Chadic < Afro-Asiatic), where plosives can have nasally released allophones in specific conditions. The mechanics of velum lowering is not discussed explicitly, but one of Schuh’s Karekare consultants describes the sounds as ‘shooting through the nose’ (Schuh Reference Schuh2008: 57, translating Malam Kariya Gambo’s description in Hausa). This is suggestive of a native speaker intuition about an articulatory process that is not just muscle-controlled but also has an aerodynamic component, with the use of ‘shooting’ suggesting that it involves more than just the standard pulmonic pressure build-up of the plosive phase. So at least from the perspective of these descriptions, there are some indications that glottalic reinforcement producing a specific type of nasal plosion is not implausible. It should be fairly straightforward to test this with airstream measurements – including questions like the precise relation between muscle-controlled and aerodynamically controlled phases – though this study is not the context in which to do this.

7. Discussion and conclusion

To round off this study, I summarize the most important findings, and I try to put them in a broader diachronic and typological context. What stands out most about prestopped nasals in Morrobolam are (i) the long and voiceless plosive phases in prestopped realizations, significantly longer than nasal phases for most speakers and most places of articulation, (ii) the existence of preaspirated realizations for some speakers, and (iii) the existence of long and noisy bursts in prestopped realizations for the same speakers, which may form a pathway for the emergence of preaspiration from prestopping. Given that non-nasal phases are consistently longer, and show most of the phonetic ‘action’, a term like ‘postnasalized plosive’ or even ‘postnasalized obstruent’ might be more appropriate phonetically. However, phonologically the segments do not pattern with plosives, and there are significant links with nasals, including the existence of plain nasal realizations, and a (near-)collapse with the plain nasal series in the youngest generation of speakers. In what follows, I put the findings about plosive and preaspirated phases in a broader context. Specifically, I discuss the likely origin and development of long and voiceless plosive phases, and I compare preaspiration with a number of typological parallels, in particular voiceless nasals as found in some Tibeto-Burman languages.

7.1 Plosive phases

As already mentioned, long and voiceless plosive phases are quite different from what the classic analysis of the origins of prestopping might lead us to expect. If prestopping is a matter of late velic opening, helping to preserve place of articulation cues in formant transitions from the preceding vowel, one would expect a plosive phase that is relatively short, with the same laryngeal settings as the nasal phase. So, the classic analysis at best offers a scenario about the origins of prestopping in Morrobolam, but not what it looks like synchronically.

There is, in fact, some evidence for the plausibility of this origin scenario for Morrobolam, if we also take into account its sister language Mbarrumbathama. Roots with prestopped nasals in Morrobolam systematically have cognates with prenasalized stops in Mbarrumbathama: both derive from plain intervocalic nasals, in roots where the reconstructed initial is not itself nasal, as illustrated in (14) (see further in Verstraete Reference Verstraete and Bowern2023). In other words, the plosive phase, with its potential protective effect, is at different sides of the nasal in the two sister languages.

Morrobolam has systematically lost initial consonants, while Mbarrumbathama has systematically lost the entire first syllable. This goes hand in hand with a distinction in the functional load for vowel contrasts. In Mbarrumbathama, the main functional load is on the vowel position following what was originally the medial consonant (including prenasalized stops), the only one that remains of the original root. In Morrobolam, by contrast, the main functional load is on the vowel position preceding the medial consonant (including prestopped nasals): there is no evidence of reduction in terms of duration or quality (to schwa), and there is no evidence of historical leveling, unlike for the vowel position following the medial consonant (see further in Verstraete Reference Verstraete, Monaghan and Walsh2020). Given this distinction, the plosive phase is actually in the right spot for it to have a protective effect on the vowel position with the largest functional load in the two languages. A plosive phase does not just help to preserve place of articulation cues for the nasal, but by preventing vowel nasalization it also helps to preserve vowel contrasts that would otherwise be affected perceptually by nasalization (e.g. Beddor Reference Beddor, Huffman and Krakow1993). In Morrobolam, this would result in prestopped nasals, protecting the preceding vowel, whereas in Mbarrumbathama it would result in prenasalized stops, protecting the following vowel. This is exactly what we find, and therefore at least compatible with the origin story of both prestopped nasals and prenasalized stops.

Even if the origin story of prestopping looks plausible, it does not explain either duration or voice settings of plosive phases in Morrobolam. But there are indications in the published literature on prestopping elsewhere in Australia, relating to phonologization and boundary marking. Increased relative duration may be due to phonologization. This is suggested by Harvey et al.’s (Reference Harvey, Lin, Turpin, Davies and Demuth2015) study of Kaytetye, which shows that contrastive prestopping has longer plosive phases than non-contrastive prestopping, a development the authors attribute to enhancing the perception of a new production goal (see also Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, San, Carew, Strangways, Simpson and Stockigt2019). Consistent voicelessness is another matter, however, which cannot be attributed to phonologization. As discussed in section 4.2 above, contrastive prestopping in other Pama-Nyungan languages can have either voiced plosive phases (as in Arabana; Karnic < Pama-Nyungan) or voiceless ones (as in Kaytetye and Eastern Arrernte; both Arandic < Pama-Nyungan; see section 4.2 for references). The typological similarity to the Arandic cases is probably not a coincidence, as Lamalamic and Arandic have gone through very similar phonological developments, involving historical loss of initial consonants, stress shift, and strengthening of (historically) medial consonants into new contrasts (including prestopping for nasals, and in the case of Morrobolam also fricatives and voicing contrasts for plosives). The original scenario was developed in Hale (1964, Reference Hale and Sutton1976a, Reference Hale and Sutton1976b) based on the Northern and Middle Paman subgroups of Paman languages, while Koch (Reference Koch, Tryon and Walsh1997) and Verstraete (Reference Verstraete2018a, Reference Verstraete and Bowern2023) provide historical-comparative analyses for Arandic and Lamalamic, respectively. In both cases, prestopped nasals typically land in a position of prominence, as the first consonantal position in the word (due to initial consonant loss), and the onset of the stressed syllable (due to shift of stress). This implies that they coincide with a prosodic boundary, which may explain their default association with voicelessness (see also Harvey [forthcoming] on the role of prosodic boundaries in durational differences in prestopping). Baker (Reference Baker2008), cited in Harvey et al. (Reference Harvey, San, Carew, Strangways, Simpson and Stockigt2019), as well as Kingston (Reference Kingston, Colantoni and Steele2008), argue that voiceless holds constitute an interruption in the signal, which can be regarded as an instance of fortition associated with a boundary position. The plausibility of voicelessness as a boundary signal in Morrobolam is further confirmed by the behavior of prestopped nasals in post-tonic position, i.e. not at a prosodic boundary (where they can land occasionally due to various diachronic processes, see Verstraete Reference Verstraete2018b, Reference Verstraete and Bowern2023): in such positions the plosive phase can and does become voiced, as discussed in section 4.2 above.

7.2 Preaspiration

Preaspiration is a typologically unusual feature in the realization of prestopped nasals, which to my knowledge has not been reported in the literature on prestopping. Even if the link with prestopping is surprising, from a broad typological perspective aspiration is not that unusual in association with nasals. Voiceless nasals, as reported for a number of Tibeto-Burman languages, are characterized by a period of aspiration associated with a short voiced nasal phase: before the nasal phase, as in Burmese and Mizo, or after it, as in Angami, Xumi and Kham Tibetan (see Bhaskararao & Ladefoged Reference Bhaskararao and Ladefoged1991; Blankenship et al. Reference Blankenship, Ladefoged, Bhaskararao and Nichumeno1992; Chirkova et al. Reference Chirkova, Basset and Amelot2019). Phonetically, aspiration in these cases appears to involve both a timing relationship with voicing onset (e.g. Ladefoged & Maddieson Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 66–70), as well as the presence of turbulence (as suggested by the common transcription as [h] or [

![]() $\tilde{\textrm{h}}$

], Chirkova et al. Reference Chirkova, Basset and Amelot2019: 2). In this sense, Burmese-style voiceless nasals, where aspiration precedes the voiced nasal portion, appear to offer an interesting typological parallel with the preaspirated realizations studied here. The literature on voiceless nasals allows us to further contextualize two aspects of preaspirated realizations in Morrobolam, viz. their origins and their articulatory structure, specifically the role of nasal airflow.

$\tilde{\textrm{h}}$

], Chirkova et al. Reference Chirkova, Basset and Amelot2019: 2). In this sense, Burmese-style voiceless nasals, where aspiration precedes the voiced nasal portion, appear to offer an interesting typological parallel with the preaspirated realizations studied here. The literature on voiceless nasals allows us to further contextualize two aspects of preaspirated realizations in Morrobolam, viz. their origins and their articulatory structure, specifically the role of nasal airflow.

The first issue is the origin of aspiration. In Burmese-style voiceless nasals, preaspiration can be traced back diachronically to a sequence of fricative and nasal, weakened into an aspirated phase preceding a voiceless nasal (Ohala & Ohala Reference Ohala, Ohala, Huffman and Krakow1993; Chirkova & Handel Reference Chirkova and Handel2022). For prestopped nasals in Morrobolam, preaspiration is linked to long and noisy bursts in prestopped realizations. As argued in section 6, these may have changed the signature characteristic of the non-nasal phase from a hold-burst structure to turbulence, which through gestural realignment (speeding up of velic opening relative to oral closure) may have formed a pathway from prestopping to preaspiration. Putting these two arguments together actually strengthens both accounts. From the perspective of Morrobolam, the literature on voiceless nasals demonstrates that fricative-like segments (whether genuine fricatives or long bursts) can actually form the diachronic origins of preaspiration. And from the perspective of voiceless nasals, Morrobolam offers an interesting case where the putative diachronic pathway is actually observable in synchronic variation.

The second issue is the articulatory structure of preaspirated realizations in Morrobolam, specifically the relation between oral and nasal airflow. Given the nature of the corpus, we will only ever have acoustic data on Morrobolam, so in the absence of aerodynamic measurements the best we can say is that nasal airflow is likely given the scenario in which preaspiration originates in a specific type of nasally released burst. The literature on voiceless nasals does have aerodynamic measurements, however. Chirkova et al. (Reference Chirkova, Basset and Amelot2019) show how the aspirated phase in Burmese voiceless nasals has both oral and nasal airflow, whereas the voiced nasal phase only has nasal airflow. From the perspective of Morrobolam, this suggests that the arguments about the likely presence of nasal airflow in the preaspirated phase may be valid, but also that some oral airflow should not be excluded. This implies that the gestural realignment scenario proposed in section 6.1 may need some modification in its final phase. From the perspective of voiceless nasals, there is also something to be learned from the Morrobolam data. Ohala & Ohala (Reference Ohala, Ohala, Huffman and Krakow1993) argue that speakers have ‘little control’ over the intensity of the aspirated phase of voiceless nasals, which is generally low because ‘the principal point at which the turbulence is generated […] is the nostrils’ (Reference Ohala, Ohala, Huffman and Krakow1993: 232). While this is correct as regards the nostrils, the pathway for the emergence of preaspiration from prestopping shows that at least the precursors of preaspiration can have a relatively high intensity. And if the suggested articulatory basis of glottalically reinforced nasal plosion is correct, the velopharyngeal port is a significant locus of turbulence in nasal sounds, which does offer an extra measure of control for the intensity of turbulence in nasals.

Acknowledgements

I thank Bobby Stewart, Ella Lawrence and Florrie Bassani for teaching me about Morrobolam, and the younger Lamalama people for continuing support and encouragement. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the twentieth Australian Languages Workshop at Stradbroke Island (2022), and a Departmental Seminar at the University of Aarhus (2023). I am grateful to Brett Baker, Peter Bakker, Hilary Chappell, Ioana Chitoran, Mark Harvey, Harold Koch, Bill McGregor, Erich Round, Jane Simpson and Jakob Steensig for their comments on these and other occasions, as well as the students of my 2023–2024 phonetics class for preparatory transcription work. I also thank two reviewers and the editors of JIPA for very useful comments on an earlier version. Work on this study was supported by grant C14/24/046, granted by the University of Leuven’s research council.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100325100807