Introduction

Appetite and energy intake (EI) are influenced by complex, multifactorial pathways including physiological, psychological, environmental, social and cultural factors involving a wide array of mechanisms. These regulatory processes are increasingly challenged with ageing and contribute to an age-related decline in appetite, known as the anorexia of ageing(Reference Malafarina, Uriz-Otano and Gil-Guerrero1). Older adults display earlier meal termination, reduced meal intake and greater postprandial fullness(Reference Giezenaar, Chapman and Luscombe-Marsh2). This may be due to differences in mechanistic processes including slower gastric motility and emptying(Reference Rémond, Shahar and Gille3) and increased concentrations of anorectic hormones, which have been reported in studies comparing younger and older adults(Reference Johnson, Shannon and Matu4). Additional mechanisms including changes to neuro-endocrine signalling in appetite regulation, gut function alterations and sensory perception changes including taste and smell(Reference Cox, Morrison and Ibrahim5,Reference Landi, Picca and Calvani6) may also be experienced by older adults. Wider environmental and social changes common in later life (e.g. moving into care, bereavement, poverty, access to care)(Reference Cox, Morrison and Ibrahim5) alongside increased cognitive and health impairments(Reference Fostinelli, De Amicis and Leone7,Reference Pourhassan, Cederholm and Donini8) , medications and polypharmacy(Reference Zanetti, Veronese and Riso9) also play an influential role in contributing to a reduced drive to eat and EI in older populations(Reference Giezenaar, Chapman and Luscombe-Marsh2,Reference Cruz-Jentoft and Volkert10) .

Ageing is also accompanied by progressive changes in body composition, characterised by an accumulation of fat mass (FM), particularly abdominal and visceral fat, and a concurrent loss of fat-free mass (FFM). Skeletal muscle mass (SMM) declines with age and is a contributing factor to sarcopenia(Reference Wilkinson, Piasecki and Atherton11). Sarcopenia is a concern for older populations, with a 2020 meta-analysis reporting that prevalence was 9–11% in community-dwelling older adults, 23–24% in hospitalised individuals and 31–51% in nursing-home residents(Reference Papadopoulou, Tsintavis and Potsaki12). These age-related changes in body composition can be attributed to multiple factors including decreases in physical activity levels, sex hormones, growth hormone secretion and resting metabolic rate (RMR)(Reference Volpi, Nazemi and Fujita13,Reference St-Onge and Gallagher14) . In addition, an age-related redistribution of FM occurs, with older adults having a greater proportion of intra-abdominal and intra-hepatic fat compared to younger individuals, which has been linked with increased risk of multiple disease states(Reference Thompson, Ryu and Craven15–Reference Cefalu, Wang and Werbel18). Increases in adiposity, however, can occur independent of changes in total body weight, as losses of FFM can mask fat accumulation when body weight is assessed in isolation(Reference Gallagher, Ruts and Visser19). These changes may have important implications for older adults regarding appetite and EI, as it has been proposed that the metabolic activity of FFM plays a vital role in modulating appetite and EI(Reference Blundell, Gibbons and Beaulieu20–Reference Johnson, Holliday and Mistry22). However, research investigating these relationships in older adults is currently limited.

The aim of this review is to provide an overview of research investigating the association of body composition (specifically FM and FFM) with appetite and EI and to identify potential mechanisms underlying these relationships, with a focus on ageing.

Body composition terms

The body composition terms used in studies investigating appetite can vary and include lean mass or lean body mass, which is often used synonymously with FFM, lean soft tissue (LST), SMM, FM and adipose tissue(Reference Prado, Gonzalez and Norman23–Reference Heymsfield, Brown and Ramirez25). As the need for standardised terminology has been identified in expert-endorsed recommendations(Reference Prado, Gonzalez and Norman23), the different terms are first important to acknowledge. Although sometimes used interchangeably, FM and adipose tissue are different components, with FM assessed at the molecular level and adipose tissue at the tissue-organ level(Reference Prado, Gonzalez and Norman23). Fat refers to triglycerides that are mainly non-polar lipids of fatty tissues(Reference Prado, Gonzalez and Norman23). FFM (often referred to as lean mass) consists of everything in the body except fat (triglyerides)(Reference Prado, Gonzalez and Norman23) and includes skeletal muscle, bones and organs. Both FM and FFM are often estimated with techniques using the 2-compartment model of body composition, including air displacement plethysmography (ADP), dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). An expert consensus in 1981 established that the terms FFM and lean body mass (LBM) may be used interchangeably; however, in more recent research and communications, the use of the term FFM (or lean mass as a synonym) is preferred due to its more precise definition(Reference Heymsfield, Brown and Ramirez25,Reference Potter and Friedl26) . In addition, the term SMM is often used in relation to FFM; however, these terms are not interchangeable(Reference Bosy-Westphal and Müller24), as FFM includes all non-fat (triglyceride) components of the body, while SMM is composed of fat, water and protein components(Reference Rodriguez, Mota and Palmer27). The widespread use of these overlapping and often poorly defined terms has been discouraged with more accurate and clear definitions favoured in the study of body composition(Reference Heymsfield, Brown and Ramirez25,Reference Potter and Friedl26) . For the purposes of this review, the terms applicable to the method used as described in the most recent consensus recommendations on terminology(Reference Prado, Gonzalez and Norman23) defined above will be used where possible.

The link between body composition, appetite and energy intake

Regarding the role of body composition in appetite control, historically FM was thought to play a key role in energy homeostasis primarily via its influence on appetite control(Reference Graybeal, Willis and Morales-Marroquin28). Specifically, FM was proposed to have an inhibitory effect on EI(Reference MacLean, Blundell and Mennella29) primarily through leptin signalling arising from adipose tissue(Reference Picó, Palou and Pomar30). Insulin, secreted from pancreatic beta cells, shares many properties with leptin, also acting as an adiposity signal impacting energy homeostasis(Reference Badman and Flier31). Both leptin and insulin act in concert, signalling to the brain to stimulate satiety(Reference Badman and Flier31). Multiple recent studies and reviews however provide mixed evidence, mostly suggesting that FM and BMI have no association(Reference Wells, Davies and Hopkins32–Reference Lissner, Habicht and Strupp35) or a weak negative association(Reference Hopkins, Finlayson and Duarte36) with daily EI. This effect appears to differ based on the degree of adiposity, with negative associations between FM and EI evident only in lean individuals(Reference Hopkins, Finlayson and Duarte36), with often no association or a weaker association observed in individuals with overweight and obesity(Reference Blundell, Caudwell and Gibbons33,Reference Lissner, Habicht and Strupp35,Reference Cameron, Sigal and Kenny37) .

Although the focus of body composition research in relation to appetite was previously primarily focused on FM, Blundell et al. drew attention to a key role for FFM in a study published in 2011(Reference Blundell, Caudwell and Gibbons33) and subsequent reviews(Reference Blundell, Caudwell and Gibbons21,Reference Blundell, Finlayson and Gibbons38) . In a cross-sectional analysis of 92 individuals living with overweight and obesity, Blundell et al. demonstrated that FFM (but not FM or BMI) was associated with objectively measured EI(Reference Blundell, Caudwell and Gibbons33). In a subsequent review, he also drew attention to an earlier publication describing similar relationships in women with overweight and obesity, noting that the relationships were effectively ‘hidden’ as the study was investigating a different question(Reference Blundell, Gibbons and Beaulieu20,Reference Blundell, Finlayson and Gibbons38) . Since then, several studies have shown similar positive associations between FFM and EI in various populations, including infants(Reference Wells, Davies and Hopkins32), adolescents(Reference Cameron, Sigal and Kenny37,Reference Vainik, Konstabel and Lätt39,Reference Thivel, Hopkins and Lazzer40) and adults(Reference Blundell, Caudwell and Gibbons33,Reference Weise, Hohenadel and Krakoff41–Reference Casanova, Beaulieu and Oustric45) and using a variety of methods. A summary of studies investigating relationships between body composition, appetite and EI is provided in Table 1.

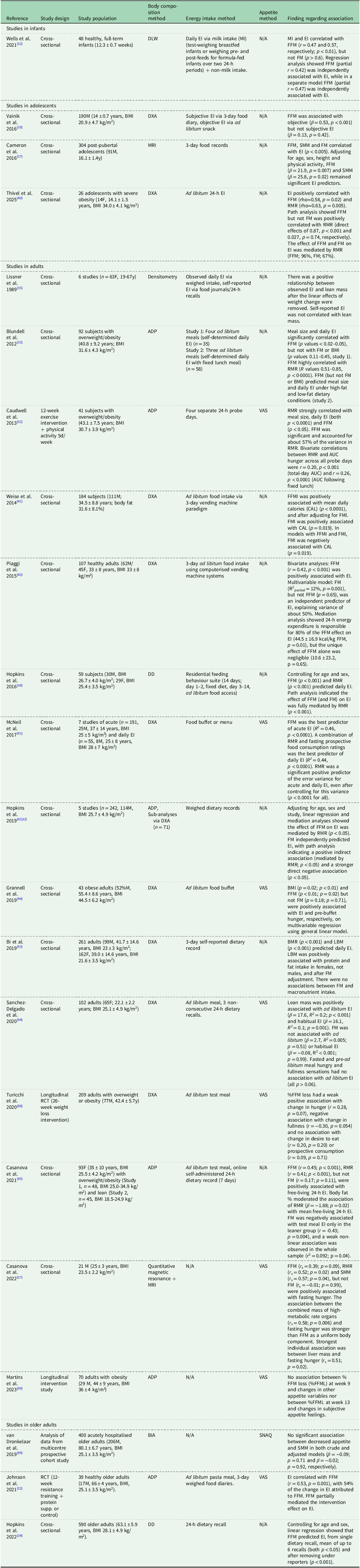

Table 1. Overview of studies investigating associations between body composition, appetite and energy intake

DLW, doubly labelled water; EI, energy intake; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; SMM, skeletal muscle mass; ADP, air displacement plethysmography; VAS, visual analogue scale; FFMI, fat-free mass index; FMI, fat mass index; DD, deuterium dilution; LBM, lean body mass; RCT, randomised control trial; SNAQ, Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire.

Findings in older adults

Studies investigating associations between FFM, appetite and EI in older adults, however, are limited. Although reduced EI is clearly implicated as a factor contributing to a reduction in lean mass and/or sarcopenia(Reference Landi, Camprubi-Robles and Bear46,Reference Landi, Liperoti and Russo47) , few studies have examined direct associations of body composition with appetite and/or EI in older adults. Moreover, similar to previous models of appetite control in the general population(Reference Badman and Flier31), theoretical models of poor appetite in older adults have included FM but not FFM(Reference Malafarina, Uriz-Otano and Gil-Guerrero1,Reference Morley48) as a factor impacting appetite. Although age-related declines in FFM and appetite have generally been investigated in separate studies, some recent evidence demonstrates positive relationships between FFM and EI in older adults. In a cross-sectional analysis, Hopkins et al.(Reference Hopkins, Casanova and Finlayson34) demonstrated that FFM, but not FM, determined by deuterium dilution was positively correlated with daily EI assessed by 24-h dietary recall in 590 older adults (63.1 ± 5.9 years, BMI, 28.1 ± 4.9 kg/m2). Elsewhere, in a longitudinal study, Johnson et al.(Reference Johnson, Holliday and Mistry22) reported increases in FFM, but not FM, assessed by ADP were associated with an increase in appetite and ad libitum test meal EI after a 12-week intervention in 39 healthy older adults (66 ± 4 years, BMI, 25.1 ± 3.5 kg/m2). In contrast, a multicentre prospective cohort study of 400 acutely hospitalised older adults found no significant association between appetite, measured via the Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ), and SMM assessed by BIA, although EI was not assessed in this study(Reference van Dronkelaar, Tieland and Aarden49). It is important to note that self-reported appetite measures such as the SNAQ and objective measures of EI capture distinct aspects of EI regulation, which may partly explain the difference in findings observed in the above studies(Reference Holt, Owen and Till50). Overall, these findings in older adults support evidence from other populations linking lean mass/FFM with the drive to eat (Table 1).

RMR as a mediator

Based on findings demonstrating a positive association between FFM and EI in younger populations, it was proposed that the metabolic activity of FFM plays a vital role in modulating appetite and EI as FFM creates a tonic drive to eat, ensuring the energetic requirements of crucial tissue-organs and metabolic processes are reached(Reference Blundell, Gibbons and Beaulieu20,Reference Blundell, Caudwell and Gibbons21,Reference Hopkins and Blundell51) . A potential pathway through which FFM may influence appetite and EI is via the role of RMR. Evidence from younger populations suggests that the relationship between FFM and EI is statistically mediated by both RMR(Reference Hopkins, Finlayson and Duarte36,Reference Hopkins, Finlayson and Duarte43) and total daily energy expenditure (TDEE)(Reference Piaggi, Thearle and Krakoff42). For example, research in 41 middle-aged individuals with overweight and obesity showed that those with a higher RMR had increased levels of hunger and greater food intake compared to those with lower RMR(Reference Caudwell, Finlayson and Gibbons52). A more recent 2025 study involving twenty-six adolescents with severe obesity showed that 24-h ad libitum EI was positively correlated with FFM, 24-h TDEE and RMR. In addition, a path analysis demonstrated that FFM, but not FM, was positively correlated with RMR and that 96% of the association of FFM with EI was mediated by RMR(Reference Thivel, Hopkins and Lazzer40).

The concept that energy expenditure can influence and drive EI is consistent with the well-established theory in which FFM is the strongest determinant of RMR, with RMR in turn being the strongest contributor to TDEE in most individuals(Reference Ravussin, Lillioja and Anderson53). As mentioned previously, FFM is heterogeneous and includes individual tissues and organs with distinct metabolic functions and tissue-specific metabolic rates(Reference Javed, He and Davidson54–Reference Elia56) which in turn impact RMR. Interestingly, Casanova et al. demonstrated in younger adults that fasting hunger was more strongly associated with SMM and the combined mass of high-metabolic rate organs (particularly the liver) than with FFM as a single uniform body component(Reference Casanova, Bosy-Westphal and Beaulieu57).

Recent research has investigated the relationship between body composition, EI and RMR for the first time in older adults, using data collected from 169 community-dwelling older adults (72.2 ± 5.9 years, 115F) across three countries (Ireland, Germany and Italy) participating in the multi-centre APPETITE project(Reference Horner, Mullen and Quinn58). Body composition, including FFM and FM, was assessed by BIA in all three countries, with additional ADP and RMR measurements in the Irish subsample. FFM by BIA was positively associated with both ad libitum test meal (p = 0.01) and daily EI (p < 0.001) and was also positively associated with appetite via the SNAQ (p = 0.001). In contrast, FM was not associated with these variables (p > 0.05 for all). In the Irish subsample, both FFM by ADP and RMR were independently associated with test meal EI (p < 0.05 for both). Therefore, a path analysis was conducted to investigate mediation effects, which demonstrated that the relationship of FFM with test meal EI was partially mediated by RMR (both paths p < 0.05)(Reference Quinn, Corish and Hopkins59). This suggests that in older adults, RMR partially mediates the positive relationship between FFM and EI observed.

Other potential mechanisms contributing to the link between fat-free mass and appetite/energy intake

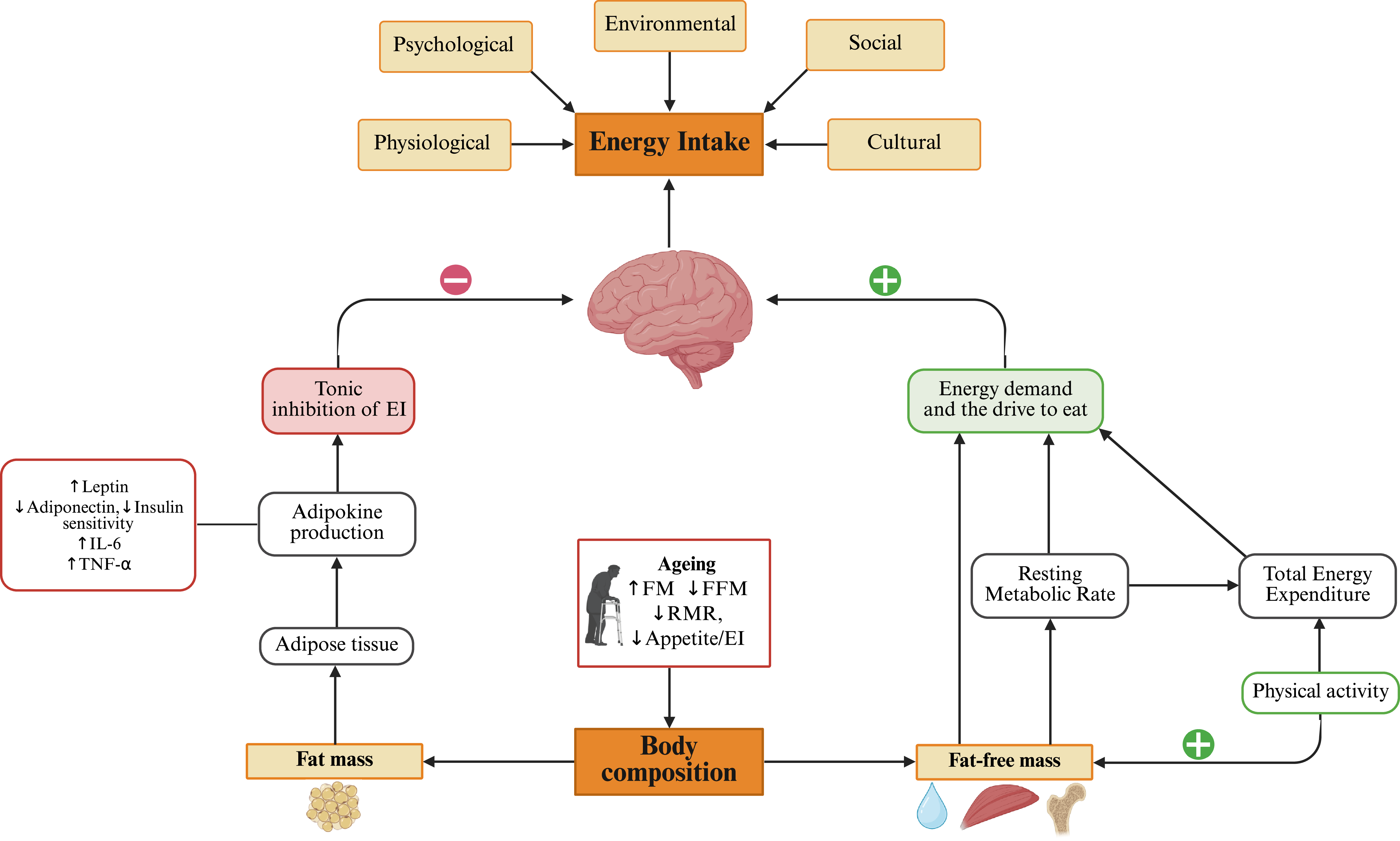

In addition to RMR, other mechanisms may contribute to an association between FFM, appetite and EI in older adults, including physical activity, appetite-related hormones and myokines (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram illustrating the role of body composition in impacting energy intake (EI) with ageing, alongside other physiological, psychological, environmental, social and cultural factors. Fat mass (FM) contributes to adipokine production which exerts a tonic inhibitory effect on EI. In contrast, fat-free mass (FFM) drives energy demand partially via RMR, stimulating the drive to eat. A direct association of FFM with EI is also proposed; however, the mechanisms of this direct path warrant further investigation. Ageing is associated with increased FM, reduced FFM and RMR, and reduced appetite and EI. Created in BioRender. Quinn, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/kbl3ub.

Physical activity

As lower muscle mass is associated with a higher risk of functional decline and reduced physical activity in older adults(Reference Visser, Sääksjärvi and Burchell60), it is possible that relationships between FFM and EI might be driven by underlying differences in physical activity level and a corresponding impact on activity and daily energy expenditure. However, in the cross-sectional study by Hopkins et al. in older adults, although physical activity was associated with EI, it only explained a further 1–4% of the variance in EI when included alongside age, sex, FM and FFM in multiple regression analyses(Reference Hopkins, Casanova and Finlayson34). The findings suggested that physical activity may influence EI, but to a lesser extent than FFM and RMR. Nevertheless, long-term exercise in older adults, particularly involving resistance training, may promote changes in body composition, normally in the form of a reduction in FM accompanied by maintenance or increases in FFM(Reference Drenowatz, Hand and Sagner61,Reference Stiegler and Cunliffe62) . These favourable body composition changes may impact RMR(Reference Gilliat-Wimberly, Manore and Woolf63), alongside potentially enhancing insulin and leptin sensitivity due to decreases in adipose tissue which may help in modulating the tonic control of appetite(Reference Gibbons and Blundell64) in older populations. Therefore, physical activity may be an important strategy for maintaining appetite and EI in older adults.

Appetite-related hormones

As mentioned previously, appetite regulation is influenced in part by a range of circulating peptides and hormones. These signals can be classified as orexigenic (appetite stimulating), including ghrelin, or anorexigenic (appetite suppressing) including peptide YY (PYY), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), cholecystokinin (CCK), glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), insulin and leptin and can influence eating behaviour and EI(Reference Coll, Farooqi and O’Rahilly65). Body composition is closely linked to these hormonal signals with FM being an endocrine organ involved in adipokine production, thereby providing tonic inhibition of EI(Reference Clemente-Suárez, Redondo-Flórez and Beltrán-Velasco66)(Figure 1). Ageing and changes in body composition can alter the concentrations and actions of some of these hormones and may contribute to alterations in appetite regulation observed in older populations(Reference Johnson, Shannon and Matu4,Reference Bertoli, Magni and Krogh67) .

Myokines and inflammatory markers

Some findings suggest that appetite may also be influenced by molecular signals arising from FFM, particularly skeletal muscle, a concept underlying the aminostatic theory of appetite control(Reference Mellinkoff, Frankland and Boyle68,Reference Bray69) , first proposed by Mellinkoff et al in 1956(Reference Mellinkoff, Frankland and Boyle68). According to this theory, EI changes in response to circulating amino acid concentrations to meet the demands of lean tissue growth and maintenance(Reference Millward70). Later research highlighted that this theory could not fully explain eating behaviour; however, it did suggest that SMM may act as a signalling body and drew increased attention towards myokines as potential mediators involved in appetite regulation(Reference Rai and Demontis71). Although a comprehensive review of potential myokines impacting appetite and EI is beyond the scope of the current review, some examples are discussed below.

Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) is considered a biomarker of cellular stress and has been associated with appetite and weight loss(Reference Johnen, Lin and Kuffner72–Reference Breit, Johnen and Cook74), and with muscle mass and markers of physical function in individuals with COPD(Reference Patel, Lee and Baz75). In addition, GDF15 has been shown to increase during progressive ageing(Reference Eggers, Kempf and Wallentin76,Reference Tanaka, Biancotto and Moaddel77) and to be an independent predictor of declining physical function(Reference Barma, Khan and Price78). A novel molecular mechanism has been demonstrated underlying age-related muscle fibre damage and loss, linking mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) with growth differentiation factors including GDF15, suggesting that mTORC1-GDF is a contributing pathway to a decline in lean mass and the development of sarcopenia (69). Therefore, GDF15 could be a potential factor linking lean mass with appetite and dietary intake in older adults.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is another myokine, which has been implicated in appetite control. BDNF has been shown to exhibit effects on the mesolimbic dopamine system to influence hedonic elements of feeding behaviour in mice(Reference Cordeira, Frank and Sena-Esteves79). In humans, peripheral BDNF concentrations have been shown to decrease with age(Reference Lommatzsch, Zingler and Schuhbaeck80,Reference Ziegenhorn, Schulte-Herbrüggen and Danker-Hopfe81) and to be inversely associated with skeletal muscle index(Reference Pratt, Motanova and Narici82) and reduced appetite (assessed using the Council on Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire) in healthy older adults(Reference Stanek, Gunstad and Leahey83).

Higher levels of inflammatory markers including IL-6, TNF-α and C-reactive protein (CRP) are associated with lower muscle strength and lower SMM/FFM(Reference Visser, Pahor and Taaffe84,Reference Tuttle, Thang and Maier85) in older adults(Reference Visser, Pahor and Taaffe84). Importantly, inflammation also influences appetite and EI, with studies showing that cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α, act on central nervous system pathways involved in appetite regulation, particularly in the hypothalamus, and may suppress appetite(Reference Pourhassan, Cederholm and Donini8,Reference Pourhassan, Babel and Sieske86,Reference Stephen and Jonathan87) .

Methodological considerations and future directions

Emerging findings in older adults support evidence from younger populations, suggesting that FFM plays a key role in appetite regulation across the lifespan. However, the literature remains relatively sparse in older adults. Furthermore, it is important to note that not all studies demonstrated significant associations between FFM and appetite/EI. For example, van Dronkelaar et al. found no significant association between changes in appetite assessed by SNAQ and SMM (by BIA) in 400 hospitalised older adults(Reference van Dronkelaar, Tieland and Aarden49). However, this may be due to the sensitivity of the measurement methods used to detect changes. As previously noted by Blundell et al.(Reference Blundell, Caudwell and Gibbons33), relationships between body composition and appetite/EI may only be apparent using objective measures under controlled conditions, and self-reports are not sufficiently accurate. Interestingly, the first study reporting on relationships between body composition and EI reported no association between lean mass and self-reported EI, but a highly significant positive association with objectively measured EI(Reference Lissner, Habicht and Strupp35).

Another aspect to consider is the role of physical activity. As shown in Table 1, some studies have controlled for physical activity or TDEE, however, despite the known influence of physical activity on body composition, metabolic rate and appetite regulation, some studies do not control for this. Similarly, appetite assessments are often absent with few studies incorporating validated appetite measures which limits the ability to link objective EI and subjective appetite ratings.

While associations between FFM, RMR and EI have been observed, the causal pathways and underlying biological mechanisms remain relatively underexplored as few studies employ longitudinal designs. Some studies including younger adults with overweight and obesity(Reference Turicchi, O’Driscoll and Finlayson88,Reference Martins, Nymo and Coutinho89) have investigated the association between loss of FFM and appetite during a weight loss intervention, providing some evidence that greater FFM loss was associated with increased appetite(Reference Turicchi, O’Driscoll and Finlayson88). This contrasts with both the positive relationship between FFM and appetite/EI observed in cross-sectional studies and longitudinal evidence in older adults of a positive association between changes in FFM and EI with resistance training and protein supplementation. This paradox may be due to differences in a ‘passive tonic’ versus ‘active’ role of FFM in driving EI as proposed by Dulloo et al(Reference Dulloo, Jacquet and Miles-Chan90). The passive role may be mediated by the body sensing the higher energy needs of FFM and adjusting EI, whereas the active role is triggered by a loss of FFM (specifically skeletal muscle and organ mass)(Reference Dulloo, Jacquet and Miles-Chan90). Therefore, the influence of body composition on appetite and EI may be impacted by the state of energy balance. Future research is needed in older populations with a focus on longitudinal studies and investigation into the mechanisms underlying these associations.

Conclusions

Appetite control is multifactorial and is influenced by a complex interplay of various determinants and pathways. Within this complexity, body composition has an increasingly recognised role with FFM highlighted as a key driver of EI, and FM appearing to have a smaller role. Recent evidence builds on previous research from younger populations(Reference Blundell, Caudwell and Gibbons33,Reference Hopkins, Finlayson and Duarte36,Reference Weise, Hohenadel and Krakoff41,Reference Grannell, Al-Najim and Mangan44) and demonstrates that the positive relationship between FFM and EI observed in younger adults is also evident in older adults(Reference Johnson, Holliday and Mistry22,Reference Hopkins, Casanova and Finlayson34,Reference van Dronkelaar, Tieland and Aarden49) . Notably, for the first time in older adults, path analysis suggests that RMR, a major determinant of TDEE, partially mediates the influence of FFM on EI(Reference Quinn, Corish and Hopkins59). These findings suggest that reductions in FFM and RMR may provide an important explanation, at least partially, for diminished appetite with ageing, highlighting them as potential targets for intervention. Strategies aimed at preserving or increasing FFM, for example through resistance exercise and/or nutritional support, could play an important role in supporting appetite and maintaining EI in older populations. This warrants further longitudinal investigation.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend appreciations to the Nutrition Society for inviting the present review as part of the postgraduate competition 2025.

Author contributions

Anna M. Quinn wrote the review article. Katy M. Horner advised in relation to the content and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to reviewing and editing and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.